Launching Lifelong Health by Improving Health Care for Children, Youth, and Families (2024)

Chapter: 5 Health Care for Children and Youth

5

Health Care for Children and Youth

Elevate the role of the [health care] system beyond disease prevention and caring for sick children [. . .], design a better system with the patient and their caregiver in mind [. . . and support] the family system as the key pathway to promoting child health.

—Comment to committee from health foundation employee, Houston, Texas

Generally, the U.S. health care system is fragmented and uncoordinated, and it typically responds to diseases and health problems after they arise. Despite shifts to managed care and forms of capitation at the payer level, the fee-for-service payment model still dominates in payments to clinicians and provider organizations, incentivizing inefficient, inequitable, and unnecessarily costly care (see Chapter 6). Overall, the system is optimized to maximize visits, procedures, profits, and treating medical problems after they occur, rather than preventing them from occurring in the first place. This payment model provides little support for health promotion, team care, and coordination (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies], 2023a).

As for adults, health care for children and youth in the United States is delivered in a patchwork of settings with little coordination among multiple insurers and siloed delivery systems. Children, youth, and their families find and receive care from a complex array of providers that differs based on geography, community, clinical and social need, and financing. The child health care system has largely been modeled after the adult system; however, as discussed in Chapter 1, five important factors (the “5 Ds”—developmental

change, disease/differential epidemiology, dependence, demographics, and dollars—indicate unique aspects of care delivery for children that require attention.

Despite the needed improvements, health care for children has seen innovations and improvements in many communities over the past few decades, providing a clear and evidence-based strategy for transformation. Advances have included greater attention to various social, family, and community factors influencing health outcomes; changing the content of pediatric care; building connections with other programs to enhance child and family development; coordinating care broadly; and linking families with other critical community resources. Yet bringing these strategies to scale and implementing them consistently have been hampered by payment and other factors. Even with this progress and well-evidenced strategies for change, the health status of children and young families in America is considerably inferior to that in comparable developed countries (see Chapter 4). Several prior reports have noted progress in implementing a life course approach, integrating mental and behavioral health into pediatric care—both primary and subspecialty—and integrating within community systems, although without broad and adequate uptake (National Academies, 2019d, 2022b, 2023c,f,j, 2024b).

Given this complexity, defining the scope of and discussing all the health care system’s elements and issues are difficult. This chapter focuses on a high-level review of health services for children and families and the clinical settings in which they are provided, with a specific examination of the opportunities and challenges for providing mental and behavioral health care. It spans primary care for preventive, acute, and chronic care services, emergency care, chronic care, subspecialty care, inpatient and intensive care, and rehabilitation. The chapter describes innovative expanded advanced primary care and specialty team care models that integrate physical and mental health care and provide a wider set of services to aid families and strengthen child development and wellbeing.

Most of this chapter focuses on transforming primary care to strengthen health promotion and disease prevention, but it also reviews innovations in inpatient and specialty care for children with acute and complex chronic conditions. The chapter concludes with a review of the pediatric health care workforce. Subsequent chapters discuss financing for health care (Chapter 6), care in conjunction with investments in population health (Chapter 7), care in school-based settings (Chapter 8), and measurement and accountability approaches to support an improved focus on health promotion and prevention and integrated, team-based care (Chapter 9).

The child and adolescent health workforce is diverse, including physicians (those with an MD or DO in pediatrics, family medicine, or general medicine), nurse practitioners and physician assistants, nurses, mental

health care providers, community health workers, and others. General pediatricians provide most primary care visits for U.S. children across all pediatric age groups, including adolescents (76% in 2019, 72% in 2020, and 72% in 2021; Hong, Huo, & Desai, 2023). Almost all U.S. children and youth have identified sources of primary care and insurance coverage, although the nature, quality, and accessibility of the services vary, and low-income children often report the local emergency room as their usual source of care. Residents of rural areas often lack access to many services, especially specialized services for children.

Some primary care providers offer mainly the essentials of traditional practice—immunizations, some screenings, identification and treatment of common acute conditions—and refer patients to other providers for needs beyond these basic efforts. In other cases, following the model of the family-centered medical home, primary care has evolved into a multidisciplinary team-based program, with integrated mental and behavioral health and links to other community programs and supports through extended team members, such as community health workers and social services providers. This shift toward team-based care presents a critical opportunity for medical providers and community partners (e.g., caregivers, schools, dietitians and/or nutritionists, specialists, pharmacies, nursing agencies, vendors of durable medical equipment, other home care agencies and counselors) to respond to the unique and evolving needs of children and youth by drawing on a variety of support systems (Katkin et al., 2017). Given the increasingly fragmented and complex landscape of health care, team-based care can serve as a catalyst for fostering more effective patient care and improving the experience of those in the workforce (Smith et al., 2018). In settings that support integrated care, screening and intervention with families has evolved from traditional screenings, such as for lead and anemia, to greater attention to relationships, child development and behavior, and social determinants of health.1 Increasingly, pediatric primary care providers have worked to identify and provide resources for addressing broader influences on child health, although financing rarely incentivizes such changes (see Chapter 6). Although these developments are not the norm, efforts to shift emphasis from diagnosis and treatment to prevention and health promotion require centering individual needs while simultaneously promoting population and community health (see Chapter 7).

Hospitals that provide care to children and adolescents offer a wide array of often very specialized services, building from extensive research advances and new diagnostic and treatment methods. As noted in Chapter 1, most pediatric subspecialists work in academic medical centers. Such placement

___________________

1 Such screenings are recommended through the national Bright Futures Guidelines (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2017).

has facilitated advances in medical care with astonishing impacts on disease management and children’s survival. The growth of excellent subspecialty care (e.g., for childhood cancers) has also moved a significant amount of specialized care from inpatient to outpatient settings. Today, pediatric inpatient care typically serves children who have relatively rare conditions or marked instability requiring more intensive care (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2021b, 2022b; Weiss, Liang, & Martin, 2022).

Children and families receive mental health screenings and services in several settings, including traditional practice; community-based mental health centers; schools and preschools; and, increasingly, primary care settings that integrate mental and behavioral health professionals and include community health workers as part of the mental health team. Children and youth also receive some mental and behavioral health services in juvenile justice settings and inpatient hospital settings—some of which are part of a children’s or general hospital, while others are focused solely on psychiatric and mental health. Finally, as an intermediate level between hospital and community settings, residential care provides supervised care at lower acuity levels than hospitals. Despite this array of settings, many children and youth do not receive needed mental and behavioral health care, and there is limited coordination among these settings or with the rest of the health care system, including primary care.

HEALTH CARE AND CRITICAL PERIODS OF DEVELOPMENT

Chapter 2 described sensitive and critical developmental periods, including preconception and prenatal periods; infancy, childhood, and adolescence; and the transition into adulthood. Understanding and optimizing these developmental periods—and ensuring that the health care system provides developmentally appropriate care as children and youth transition across these stages—are essential for children to thrive.

Preconception and Prenatal Health

Health during the preconception and prenatal periods is crucial to minimize the risk of adverse birth outcomes, such as preterm or low birth weight, and to optimize the healthy development of children (including organ formation, fetal growth, epigenetic changes, and long-term health outcomes) and their families (Keikha, Jahanfar, & Hemati, 2022; Khekade et al., 2023). These periods are critical because they lay the foundation for the health and development of the child, influencing outcomes from birth through adulthood (see Chapter 2). Preconception care involves health care interventions and services provided to individuals or couples before

pregnancy to optimize their health and promote favorable outcomes for both the pregnant person and the baby (Keikha, Jahanfar, & Hemati, 2022; Khekade et al., 2023). The Centers for Disease Control and Promotion (CDC), American Association of Family Physicians, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists provide guidance on prepregnancy or interconception care and counseling (Jack et al., 2008; Wise, 2008). This care includes health promotion and lifestyle adjustments, risk assessment, and management of preexisting conditions. Key components include health education on maintaining a balanced diet and folate supplementation, exercising, and avoiding harmful substances, as well as regular checkups and screening for health risks, medical conditions, genetic counseling, and ensuring immunizations are up to date (Herval et al., 2019; Peahl & Howell, 2021; Soucy et al., 2023). Health and lifestyle choices made before conception can have a profound impact on the health outcomes of future offspring (Atrash et al., 2006; Khekade et al., 2023). Preconception care helps to mitigate risks and support healthy development from the earliest stages, influencing long-term health outcomes for the child and family.

Optimizing preconception health requires broad strategies to reach the population at risk for pregnancy; multiple health care interventions have shown promise (Hemsing, Greaves, & Poole, 2017). Pediatric primary care can support preconception care among parents in their practice who are interconceptional for their next child. A multisite cluster randomized trial of a maternal health screener and brief intervention in primary care was found to be feasible and effective in increasing folate use and decreasing smoking (Chilukuri et al., 2018; Upadhya et al., 2020).

Early Childhood and Family Health

Families have more encounters with pediatric primary care in the first 3 years of life than with the education sector; thus, pediatric primary care represents a critical leverage point in promoting early relational health, in addition to focusing on health creation, prevention, and wellbeing for those with access. Most families bring their children to a health care provider for preventive care, with visits starting just after birth. Preventive care visits can be frequent in the first years of life—12 well child care visits are recommended to be provided to children in their first 3 years of life based on the national Bright Futures Guidelines—offering multiple touchpoints with families; preventive care is nonstigmatizing because it is a universal intervention in the United States (Roby et al., 2021). However, current trends in visits fall short of these national guidelines (see below).

Early intervention services for supporting the health and wellbeing of young children and families have been a focus for improving outcomes.

Home visiting programs starting prenatally or after birth demonstrate improved child, maternal, and family outcomes (see Chapter 7). Integration of home visiting programs with the health care system has been variable, and data sharing and more collaboration are needed (Tschudy, Toomey, & Cheng, 2013). The importance of early childhood preventive care and its impact on long-term health outcomes is well established. Several models have been proposed and studied to transform the delivery of preventive care during this critical period.

The Parent-focused Redesign for Encounters, Newborns to Toddlers (PARENT) model incorporates a culturally responsive parent coach as part of the care team for children aged 0–3 years. PARENT has been shown to improve the receipt of well-child care, enhance parent experiences, and reduce emergency department utilization (Coker et al., 2016; Mimila et al., 2017). The 3-2-1 Integrated Model for Parents and Children Together (IMPACT) program, launched by New York City Health and Hospitals in 2020, provides a comprehensive two-generation program integrating mental health, pediatrics, and women’s health to improve the long-term trajectory for each family unit (NYC Health + Hospitals, 2020). The program offers a personalized approach to care with routine screenings for mothers during pregnancy and postpartum follow-up and pediatrics visits, employing Healthy Steps workers to engage families during visits (HealthySteps, n.d.a,c). Screening identifies when a family has additional medical or nonmedical social needs, such as mental health care or food or income support, with interventions provided in addition to universal parenting supports within health care (Filene et al., 2013; NYC Health + Hospitals, 2020). Preliminary evidence indicates that the 3-2-1 IMPACT model can improve health outcomes among low-income populations (McCord et al., 2024).

School-Age Children

As children start school, health care visits decrease in frequency, occurring annually unless health issues require more frequent follow-up (AAP, 2023; Freedman, 2020; Riley, Morrison, & McEvoy, 2019). During this period, children can learn basic positive health behaviors. It is also a time when several behavioral and mental health disorders can manifest, and screening and early intervention for those conditions is critical for long-term mental and behavioral health (Abramson, 2022). Given the fewer primary care visits during this period (as well as limited access to care for some children), school-based health monitoring, including for mental and behavioral health problems, in collaboration with health care systems provides key preventive services and intervention (see Chapter 8).

Adolescents and Young Adults

Health care services during adolescence and emerging adulthood are critical for ensuring both their present and long-term health and wellbeing. Adolescence is an opportune time to address health-related habits—including diet, exercise, sexual and reproductive health, and substance use—that can impact longer-term health. However, many adolescents, particularly those from historically marginalized groups, face a variety of barriers to accessing health care services, including financial barriers, privacy concerns, lack of culturally responsive care, and timely availability of services. Adolescents also have needs that are distinct from those of children. Health services for adolescents and young adults need to prepare youth and their families for the developmental changes (physical, cognitive, and social) that take place during adolescence and address these changes with culturally informed services that are attentive to the needs of all adolescents (National Academies, 2019c).

Adolescents need access to models of care that consider the entirety of their needs—from medical to social—and other factors in their lives (e.g., social determinants of health, the cultural and social content in which they live; National Academies, 2019d, 2020b). Models of care need to promote communication, collaboration, and coordination among physical health and mental health care providers, youth, and their families.

With increasing independence and autonomy, adolescents need confidential care and preparation for navigating the health care system independently, particularly the transition into adult health care systems, although many do not receive preventive health counseling and key preparatory advice (Akers et al., 2014). Confidentiality concerns remain a critical barrier for adolescents seeking appropriate medical services (Pathak & Chou, 2019). Adolescents who have time alone with clinicians have higher rates of screening and discussion of sensitive topics, more opportunity to navigate the clinic setting and engage with their own health care, and receive confidential care (Al-Shimari et al., 2022; Brown & Wissow, 2009, 2010; Chung et al., 2024; Committee on Adolescent Health Care, 2020; Ford, English, & Sigman, 2004; Klein & Wilson, 2002; McKee, Rubin, & Campos, 2011). Many youth underuse behavioral health services, despite expressed interest and need for such services (Boyd, Butler, & Benton, 2018; MacDonald, McGill, & Murphy, 2018). Like younger children, many adolescents may first seek help for mental health concerns from primary care providers. Others may rely on schools, mental health providers, or crisis centers, or they may seek care at emergency departments or other treatment facilities (National Academies, 2019c).

While adolescent health care addresses health risks such as substance use, risky sex, and poor mental health, care encounters are also opportune for exploring and supporting an adolescent’s goals and strengths (Calabrese

et al., 2022; Lindstrom Johnson, Blum, & Cheng, 2014; Lindstrom Johnson, Jones, & Cheng, 2015). Further, as adolescents and young adults enter childbearing years, sexual and preconception health is of critical importance, as is gender-affirming care.

The transition from pediatric to adult health care is particularly important for adolescents with special health care needs and/or chronic health conditions (Bloom, Cohen, & Freeman, 2012; National Academies, 2018; Stein, Perrin, & Iezzoni, 2010), who, while transitioning within the health care system, also face typical adolescent life transitions and challenges (e.g., postsecondary education or employment, leaving home, parenthood). Factors during the transition into the adult health care system affect not only the uptake of services, but also the adolescents’ ongoing physical and mental health, overall wellbeing, quality of life, and educational and employment outcomes. Many youth and young adults with special health care needs and/or chronic or complex health conditions and their families do not receive the support they need in the transition from pediatric to adult health care (White et al., 2018). Medical care models that are purposeful and planned are critical at this stage in life; such care models prepare the adolescent and their family for the transition from child-centered to adult-oriented health care in a way that considers typical developmental processes as well as access, appropriateness, and continuity of services (Calabrese et al., 2022). Strong evidence supports a continuum approach to health care transitions that incorporates multiple elements of preparation, planning, tracking, and follow-through for all youth and young adults beginning in early adolescence and continuing into young adulthood (Calabrese et al., 2022; Cooley & Sagerman, 2011; Jones, Merrick, & Houry, 2020a; Lemke et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2020; White et al., 2018).

PEDIATRIC PRIMARY CARE

Primary care forms the base for every health care system. A report by the National Academies titled Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care defines “high-quality primary care” as “the provision of whole-person, integrated, accessible, and equitable health care by multidisciplinary teams who are accountable for addressing the majority of an individual’s health and wellness needs across settings and through sustained relationships with patients, families, and communities” (National Academies, 2021b, p. 4). The report notes that its definition does not describe what most people in the United States experience today, an observation supported by data from the National Survey of Children’s Health on indicators of quality of care (see Table 5-1). Table 5-2 summarizes data compiled by the committee on children’s health care utilization.

TABLE 5-1 Quality-of-Care Indicators for Children’s Health Care in the United States

| Performance Indicator | National Prevalence, % (Across State Prevalence Range) | U.S. Children with Any Public Health Insurance,a % | U.S. Children with Private Health Insurance,b % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of children ages 0–17 years who have adequate and continuous health insurance | 68.0 (59.2–81.0) |

84.5 | 66.3 |

| Percent of children ages 0–17 years who received care in a setting that met core criteria for being a medical homec | 46.1 (33.8–57.1) |

36.3 | 55.6 |

| Percent of young children ages 9–35 months who received screening for their development | 33.7 (24.5–49.1) |

28.7 | 39.0 |

| Percent of children ages 3–17 years with a mental health condition who received treatment or counseling | 52.8 (31.9–67.6) |

52.0 | 54.9 |

| Percent of children ages 0–17 years whose health insurance and health care met criteria for being a well-functioning system of cared | 17.3 (11.6–23.8) |

14.8 | 21.2 |

| Percent of children enrolled in Medicaid/CHIP who had at least 6 of 9 recommended well-child care visits before age 15 months | Not available (N/A) |

55.7 (30.1–77.4) |

N/A |

| Percent of children enrolled in Medicaid/CHIP who had at least 2 of 4 recommended well-child care visits between ages 15 and 30 months | N/A | 64.9 (36.5–82.3) |

N/A |

a Public insurance is defined as Medicaid, Medical Assistance, or any kind of government assistance plan for those with low incomes or a disability.

b Private insurance is defined as insurance through a current or former employer or union, insurance purchased directly from an insurance company, TRICARE or other military health care, or coverage through the Affordable Care Act or other private insurance.

c The presence of a medical home was measured based on five components: personal doctor or nurse, usual source for sick care, family-centered care, problems getting needed referrals, and effective care coordination when needed.

d A well-functioning system of care was assessed based on children’s experience across several measures: (1) the family feels like a partner in their child’s care, (2) the child has a medical home, (3) the child receives medical and dental preventive care, (4) the child has adequate insurance, and (5) the child has no unmet need. A sixth measure is included for adolescents (ages 12–17 years): preparation for transition to adult health care.

SOURCE: 2021 and 2022 National Survey of Children’s Health (CAHMI, 2024); 2022 Child Core Set Report (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, n.d.a).

TABLE 5-2 Children’s Health Care Utilization

| Health Care Effectiveness Data and Information Set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utilization Measurea | Year | Commercial HMO, % | Commercial PPO, % | Medicaid HMO, % |

| At least 6 well-child visits in first 15 months | 2022 | 81 | 80.8 | 56.8 |

| At least 2 well-child visits between 15 and 30 months | 2022 | 87.3 | 88.2 | 66.7 |

| At least 1 well-child visit in past year (ages 3–6 years) | 2019 | 79.1 | 77.7 | 74.1 |

| At least 1 well-care visit in past year (children and adolescents) | 2022 | 57.6 | 56.2 | 48.6 |

| National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey | ||||

| Utilization Measure | Age Group | Year | Characteristic | Value |

| Visits to physician offices and hospital emergency departmentsb | Under age 18 years | 2018 | Number of visits (thousands) | 128,781 |

| People with hospital stays in the past yearc | 1–17 years | 2019 | % with 1 or more hospital stay | 2.6 |

| 1–5 years | 2019 | % with 1 or more hospital stay | 3.2 | |

| 6–17 years | 2019 | % with 1 or more hospital stay | 2.4 | |

| Emergency department visits in the past 12 months among children under age 18 yearsd | All childrene | 2018 | % with 1 or more emergency department visit | 17.6 |

a The percentages indicate the proportion of eligible children who met the criteria for each measure and are based on national averages.

b Data are based on reporting by a sample of office-based physicians and hospital emergency departments

c Data are based on household interviews of a sample of the civilian noninstitutionalized population.

d Data are based on household interviews of a sample of the civilian noninstitutionalized population.

e Includes all other races not shown separately and those with unknown health insurance status.

NOTE: HMO = health maintenance organization; PPO = preferred provider organization.

SOURCE: Generated by the committee, based on data from National Committee for Quality Assurance, n.d., and National Center for Health Statistics (n.d.) CDC Data Finder.

Pediatric primary care includes a broad range of services (National Academies, 2019d), with a priority on provision of comprehensive age-specific physical and mental health promotion and preventive services, particularly as outlined in Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents (AAP, 2017).2 The guidelines cover monitoring physical, cognitive, and socioemotional growth and development. They include screening for metabolic and genetic conditions in the newborn period; developmental screenings at specific ages; screenings for health conditions, such as autism, anemia, and vision or hearing impairment, and exposures, such as lead; screening for socioemotional issues and maternal and adolescent depression; and screening for social and/or other nonmedical drivers of health. There are also resources for age-specific guidelines to educate and counsel parents/caregivers on promoting the healthy development of their children. Pediatric primary care supports health promotion and disease prevention by providing immunization, dental fluoride varnish, and anticipatory guidance on topics related to physical and mental health, as well as physical and emotional development. In addition, a growing number of practices screen for social determinants of health and provide referrals and links to community services to address family needs.

Primary care also includes diagnosing and treating acute health conditions, such as infectious illnesses and injuries, as well as identifying and caring for children with special health care needs and chronic illnesses, such as asthma and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Depending on the level of complexity of a child’s illness, the primary care clinician may diagnose and treat such conditions or may refer to and coordinate care with pediatric medical and surgical subspecialists. Primary care practices also help coordinate care with households in managing insurance coverage and access to prescriptions; diagnostic testing; subspecialty care; physical, occupational, and speech therapies; and other services. Primary care clinicians often link families to services in other sectors that are important for the overall health and wellbeing of children, such as nutrition programs (e.g., Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) and early education programs (e.g., Head Start, school-based preschool programs).

Children and youth obtain primary care in multiple settings: independent pediatric and family medicine practices, larger private group practices (single and multispecialty), health centers (federally qualified health centers [FQHCs] and similar community health centers, Indian Health Service [IHS] facilities, and school-based health centers [SBHCs]), hospital or health care system–based practices, and military treatment facilities (clinics located on

___________________

2 The Bright Futures Program is funded through a cooperative agreement from the Health Resources and Services Administration with the American Academy of Pediatrics to create and share clinical national guidelines for pediatric well-child visits from birth to age 21.

military installations). Nonemergency acute care is also provided through urgent care facilities and retail-based clinics. Although in the previous century, U.S. primary care tended to occur in smaller, independent practices, over time delivery has shifted toward community clinics, hospital outpatient clinics, and health care system practices (Simon et al., 2015).

Primary care office visits are declining both across adult populations (Ganguli, Lee, & Mehrotra, 2019) and among commercially insured children and adolescents, where visits fell approximately 13% between 2008 and 2016 (Ray et al., 2020). Problem-based visits dropped 24%, while preventive care visits increased by 10%, visits to nonprimary care settings increased, and out-of-pocket costs for problem-based visits increased (Ray et al., 2020). This is consistent with findings that the number of FQHCs and the number of patients they serve have increased since 2001 (National Association of Community Health Centers [NACHC], 2014).

The next section reviews some specific settings for primary care for children and youth, including community health centers, settings for specific populations, and SBHCs, and concludes with a discussion of the growing area of telehealth.

Community Health Centers

Community health centers provide primary care and other services for 30 million people, including 12% of all U.S. children (NACHC, 2022). Health centers often serve communities with otherwise limited access to health care and high social need. Most community health centers are FQHCs. Through the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA, 2022b), the federal government supports about 1,400 health centers and similar organizations with more than 14,000 service delivery sites across the United States. FQHCs have governance boards with more than 50% patients served by the health center and are designed to meet the specific needs of the communities they serve. Many community health centers offer integrated behavioral health services, dental care, pharmacy, cancer screening, vision and eye care, pharmacy, and diagnostic and laboratory services. They also offer case management and referral to specialty care and social services, if necessary. While community health centers are not all the same, many provide more comprehensive, whole health services that focus on prevention, social needs, and upstream factors than are available in other settings (National Academies, 2023a). FQHCs provide services to about 14% of those in marginalized racial/ethnic groups in the United States, as well as 20% of the country’s individuals who are uninsured, 33% of those living in poverty, and 20% of those in rural areas. Almost 80% of FQHC patients have either public insurance or lack insurance; approximately 90% of patients had income less than 200% of the federal poverty level (NACHC, 2023a,b).

Special Population Health Care Providers

Families and children may access primary care in other settings, including IHS clinics and on-base military treatment facilities. These facilities offer comprehensive and culturally competent care tailored to the specific needs of these populations, address health disparities, and ensure access to essential health services. IHS clinics offer comprehensive services akin to community health centers and are important access points to care for American Indian/Alaska Native tribal nations (see further discussion of the IHS in Chapter 6, see also IHS, n.d.a).

Pediatric clinics located within military treatment facilities are accessible to active-duty and retiree families who are TRICARE beneficiaries (Hero et al., 2021). TRICARE is the Department of Defense insurance program for eligible service members, retirees, and their dependents. On-base pediatric clinics follow a patient-centered medical home model of care (Defense Health Agency, 2019). TRICARE beneficiaries can also access care through the broader TRICARE network of civilian providers.

School-Based Health Centers

SBHCs, located on or near primary and secondary school campuses, may provide primary and preventive medical care, behavioral health services, diagnostic care such as routine screenings, and/or preventive dental care (Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, 2018b). SBHCs vary in services provided, accessibility, degree of integration with the school, and quality of care. Although most SBHCs are operated by an FQHC, others receive support from school districts or a combination of local health care systems, public health departments, and community-based organizations. A 2016–2017 census indicated that the number of SBHCs doubled in the previous 20 years, with more than 2,500 SBHCs operating in the United States in 2016, serving 10,629 schools and more than 6.3 million children (Love et al., 2019). As of 2019, 40% of SBHCs served elementary school–age children, 30% middle or high school–age youth, and 30% children in all other grade combinations (Love at al., 2019). While this number represents only about 13% of schools nationwide and services vary widely, these facilities are typically located in areas of higher need, where communities face greater barriers to health care access (Love et al., 2019; Soleimanpour, 2020). SBHCs are more common in schools with larger proportions of socially and economically disadvantaged youth (Love et al., 2019) who may also experience disproportionate academic challenges (Chetty et al., 2019) because of structural inequalities that extend far beyond what SBHC services can influence directly (Soleimanpour, 2020). This complexity adds to the challenge of demonstrating impacts on not only health outcomes but also educational success.

SBHCs are associated with positive short- and long-term outcomes, including increased access to health services for children, families, and communities; improved health including increased use of cost-effective preventive care, such as immunizations, family planning, well-child visits, and behavioral health care; improved clinical quality scores in areas such as well-child visits, immunizations, chlamydia screening, depression screening and follow-up, and asthma control; increased health equity through access to culturally competent, high-quality, first-contact primary care; and increased number of regular patient groups and community engagement for FQHCs, school districts, and other health care providers (Arenson et al., 2019; California School-Based Health Alliance, 2022; Key, Washington, & Hulsey, 2002; Knopf et al., 2016). SBHCs have been shown to manage and treat chronic health conditions effectively, improve prenatal care and pregnancy outcomes for pregnant teens, and decrease teen pregnancy rates (Arenson et al., 2019).

Nearly 70% of SBHCs offer mental health services. Despite limitations, SBHCs can be an important access point for screening and treatment of mental health conditions, especially for children with no insurance or public insurance, who are more likely to seek mental health services at SBHCs than those with commercial insurance (Arenson et al., 2019; Keeton, Soleimanpour, & Brindis, 2012; Knopf et al., 2016). Mental health services in schools improve mental health access and outcomes (see further discussion in Chapter 8).

Overall, for children with access to them, SBHCs are an important source of primary care, chronic condition management, and mental health services. Expansion of SBHCs, particularly in resource-limited settings, is an important strategy for improving equitable access to high-quality care for children and is an approach recommended by CDC’s Community Guide and the Community Preventive Services Task Force (2021) as a means of advancing health equity.

Telehealth

Telehealth is the provision of health services remotely via video, phone, or mobile device. Telehealth can increase patient access; improve care coordination; strengthen the role of the primary care clinician; and allow subspecialists the time to provide inpatient and outpatient care in a manner that is feasible, fulfilling, and financially sustainable and best for children (Curfman, Hackell et al., 2021; Curfman, McSwain et al., 2021a,b; National Academies, 2023c,g,i). The COVID-19 pandemic led to rapid and widespread expansion of telehealth in pediatric primary care, where its use had not been common previously (Curfman, Hackell et al., 2021; Curfman,

McSwain et al., 2021a,b). With the public health emergency, policy changes allowed children with acute and chronic illnesses to connect via telehealth services to their usual source of care for management of their conditions. Many states allowed preventive care using a hybrid model that combined virtual and in-person visits (Hsu et al., 2023). During the pandemic, telehealth improved access to care for many children and youth, although disparities in access to technology and digital infrastructure related to poverty, systemic racism, and other inequities were also highlighted (Zhang et al., 2023). A review of prepandemic studies of the use of telehealth in pediatric care in specific contexts—including asthma, obesity, ADHD, and skin care—found low- to moderate-quality studies with outcomes for telemedicine interventions that were comparable to or sometimes modestly better than routine care, with positive results for parent satisfaction (Shah & Badawy, 2021).

Many mental health care systems have used telehealth to provide virtual consultations with child and adolescent psychiatrists, psychologists, and therapists (University of Texas Rio Grande Valley School of Medicine, n.d.). For example, the Texas Child Health Access Through Telemedicine program links school staff evaluating students to appropriate telehealth services (University of Texas Rio Grande Valley School of Medicine, n.d.) Telehealth allows mental health providers to collaborate with primary care physicians for early detection and treatment of conditions such as anxiety and depression. Virtual visits also make it easier for busy families to access care, reducing transportation barriers and the time between symptom onset and treatment (CDC, n.d.e). Telehealth is proving to be an effective and scalable solution to the pediatric mental health workforce shortage and improving outcomes for children and adolescents (Archer et al., 2021; deMayo et al., 2022; Gajarawala & Pelkowski, 2021; Guthrie & Snyder, 2023; Thomas et al., 2023; Totten, McDonagh, & Wagner, 2020).

Telehealth virtual visits with patients or teleconsultation across specialties are likely to continue to grow as will remote patient monitoring. New technology and the use of artificial intelligence have the potential to increase the efficiency of practice by decreasing documentation time, managing patient communications, synthesizing data, or prereading images. Virtual visits and remote patient monitoring (e.g., for failure to thrive, diabetes management, asthma, hospital follow-up) will keep more patients at home. New models of care building from telehealth are exploring “hospital at home” and “going to where the kids are” with expanded connectivity and services in schools, child care, and in the home (including home visiting). Ethical and equity considerations for patients and the workforce must be central as these innovations evolve. With children being “digital natives,”

and given the developmental origins of health and disease early in the life course, inclusion of pediatrics in these innovations is essential.

Recently, many state Medicaid programs have introduced new telehealth policies and payment opportunities, telehealth portals, telepsychiatry consultations, and collaborative care as solutions to help overcome challenges of geographical access, with a notable increase in the implementation of such models during the COVID-19 pandemic (Federation of State Medical Boards, 2023; Kwong, 2024). Prior to the pandemic, the use of telehealth in Medicaid was becoming more common; in particular, most states offered some coverage of behavioral health services delivered via telehealth, and the majority of telehealth utilization was for behavioral health services and prescriptions. However, Medicaid policies regarding allowable services, providers, and originating sites vary widely across states, with often unclear payment policies. To increase health care access and limit risk of viral exposure during the pandemic, all 50 states and the District of Columbia expanded coverage and/or access to telehealth services in Medicaid (Federation of State Medical Boards, 2023; Kwong, 2024). Many have permanently adopted telehealth policy expansions, although some states have limited coverage of audio-only telehealth. Regionalization of pediatric specialists makes coverage of telemedicine services across state lines of particular importance.

At the federal level, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (2022) directed the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to issue guidance to states on expanding access to telehealth in Medicaid. In 2023, CMS (2023j) published Telehealth for Providers: What You Need to Know, which outlines various provisions and flexibilities that CMS has issued, including those impacting Medicaid services delivered via telehealth. It provides detailed information on state policies, Medicaid coverage, and best practices for telehealth services, which align with the directive from the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (CMS, 2023j).

Retail Clinics

Retail clinics, which have spread in many regions, provide easy access for minor illnesses and often advertise convenience and lower costs in providing such services as immunizations or sports physicals (Garbutt et al., 2013; Wong et al., 2017). Among the fastest-growing components of ambulatory care for children and adults, up to 90% of retail clinic pediatric visits focused on ten common conditions, including immunizations (Mehrotra et al., 2008). While increasing access to care, they are ill equipped to provide continuity of care and comprehensive services such as those mandated under Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment services (see discussion in Chapter 6).

INNOVATION AND CHANGE IN PEDIATRIC PRIMARY CARE

Primary care in pediatrics has evolved substantially over the past several decades, from early work by the U.S. Children’s Bureau to the development and growth of the medical home model (National Academies, 2019d), aiming to transform pediatric primary care from individual-centered, treatment-focused care to whole child, family, and community health care as reviewed in Chapter 1. Active implementation of the medical home model began in 1967, with greater recognition of the importance of early life and child and community factors in the development and wellbeing of children (Sia et al., 2004). The medical home transformation called for pediatricians and pediatric clinicians to provide guidance to young families, coordinate their care and access to needed additional services, and serve as a main point of care that families can easily access for help with the broad range of services that they and their children need. The medical home model calls for comprehensive, high-quality primary care for children and youth, emphasizing characteristics of accessibility, family-centeredness, continuity, coordination, compassion, and cultural proficiency (AAP, 2022; Boudreau et al., 2022). The federal Maternal and Child Health Bureau has long championed the medical home concept, collaborating actively with the AAP in its support and development. And the medical home concept underlays key aspects of primary care reform in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010).

Medical home models differ in their focus and content for different age groups, but they generally follow a broad set of definitions and standards recognized by several professional organizations such as the AAP and the National Committee for Quality Assurance (Domino, 2021). The AAP, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians, and American Osteopathic Association have jointly outlined seven core principles of a patient-centered medical home3 (American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, & American College

___________________

3 The AAP earlier outlined four principles for pediatric medical homes, described as “a family-centered partnership within a community-based system that provides uninterrupted care with appropriate payment to support and sustain optimal health outcomes” (Ad Hoc Task Force on Definition of the Medical Home, 1992, p. 774; see also AAP, 2007; Buka et al., 2022). These principles include: (1) Family-centered partnership: Providing family-centered care through a trusting, collaborative partnership with families, respecting diversity and recognizing families as constant in a child’s life. (2) Community-based system: The medical home is part of a coordinated network of community services designed to promote healthy child development and family wellbeing. (3) Transitions: Facilitating smooth transitions along the continuum of care as the child moves through different systems and into adulthood. (4) Value: Appropriate financing to support and sustain medical homes that promote quality care, optimal health outcomes, family satisfaction, and cost efficiency (AAP, 2007, p. 1).

of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, 2002; see also AAP, 2007; Kellerman & Kirk, 2007):

- Personal physician: Each patient has an ongoing relationship with a personal physician trained to provide first contact, continuous, and comprehensive care.

- Physician-directed medical practice: The personal physician leads a team of individuals that collectively takes responsibility for the ongoing care of patients.

- Whole person orientation: The personal physician is responsible for providing all the patient’s health care needs or taking responsibility for appropriately arranging care with other qualified professionals.

- Coordinated and integrated care: Care is coordinated and integrated across all elements of the complex health care system.

- Quality and safety: Quality and safety are hallmarks of the medical home, with a focus on evidence-based medicine and clinical decision-support tools.

- Enhanced access: Enhanced access to care is available through systems such as open scheduling, expanded hours, and new options for communication.

- Appropriate payment: The payment structure appropriately recognizes the added value provided to patients who have a patient-centered medical home.

These principles developed nearly 20 years ago by physician organizations center the role of physicians. More recently, as discussed in this chapter, a wider range of clinicians provide primary care; however, the principles of a medical home still emphasize continuity of care, in alignment with the concept of whole person health (National Academies, 2023a; see also Chapter 2). Although the medical home model has helped improve care generally, its impact on families living in poverty has been limited because they often do not receive care that aligns with the principles of the medical home (Liljenquist & Coker, 2021; MacArthur & Blewett, 2023).

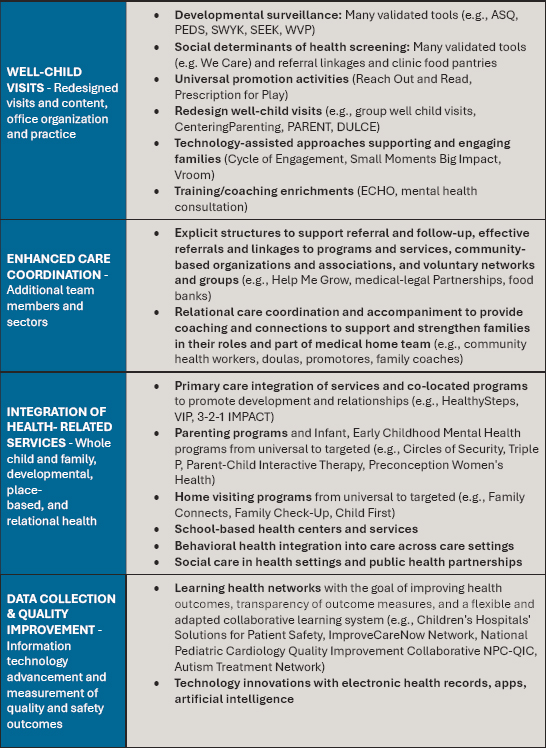

Nonetheless, development of the medical home concept over the years has led to innovation and testing of new and expanded models of high-performing pediatric primary care. These changes reflect a growing understanding of important characteristics and content of pediatric primary care (see Figure 5-1). Main advances have taken place in the content of primary care, improved coordination of care, and providing access to other services that support whole child and relational health (CMS, n.d.e; InCK Marks, 2020). Advances in the content of care have included increasingly sophisticated screening for social determinants of health and broader assessment of behavior and development. Addition of programs such as Reach Out and Read (Jimenez et al., 2023) and

NOTES: This figure is not exhaustive of all evidence-based innovations in child health care transformation but reviews some areas of innovation to the traditional health care model, including redesigned well-child care, integration of systems and added services, personnel, and technology. The maturity of these innovations is variable, with some in their infancy and others progressing rapidly. ASQ = Ages & Stages Questionnaire; DULCE = Developmental Understanding and Legal Collaboration for Everyone; ECHO = Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes; NPC-QIC = National Pediatric Cardiology Quality Improvement Collaborative; PARENT = Parent-focused Redesign for Encounters, Newborns to Toddlers; PEDS = Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status; SEEK = Safe Environment for Every Kid; SWYK = Survey of Well-being of Young Children; VIP = Video Interaction Project; WVP = Well-Visit Planner.

SOURCE: Generated by the committee based on InCK Marks, 2024.

Prescription for Play have enhanced support for parents (Weitzman Institute, 2023). Coordination of care efforts include strategies to help households link to community resources and support, through programs such as medical–legal partnerships or StreetCred (both providing legal counseling and help with accessing various benefit programs in primary care settings), and Help Me Grow, which helps link families with a broad array of community resources (American Hospital Association [AHA], 2020; Boston Medical Center, 2023). Programs such as Healthy Steps (2024) enhance pediatric care by connecting early childhood workers with young families. Others have developed parent behavior training programs through pediatric practices. Box 5-1 describes the initiative Pediatrics Supporting Parents, aimed at using early well-child visits as an opportunity to support relational health. Box 5-2 describes several promising programs with innovative approaches to pediatric team care.

Healthy Steps is among the better-studied programs, with good evidence that the program improves up-to-date well-child visits and immunizations and more family-centered care. Parents also report improved strategies for

BOX 5-1

Opportunities for Centering Relational Health in Pediatric Care

Recognizing the great importance of early childhood and wellbeing—and the importance of supporting relationships within young families—several programs have developed to strengthen and support efforts in pediatric primary care. Well-child visits (usually there are 12 between birth and age 3 years) present a unique context for interacting with and supporting families to promote relational health. In 2017, the Silicon Valley Community Foundation launched Pediatrics Supporting Parents (PSP), with support from five early childhood funders (Cohen Ross et al., 2019; Cornell, 2019). Given the importance and critical nature of early childhood experiences, PSP emphasizes enhancing pediatric care in the early years to help improve socioemotional development through support of the primary caregiver–child relationship (Cohen Ross et al., 2019; Cornell, 2019; Cornell, Therriault, & Dworkin, 2021; PSP, n.d).

The PSP initiative centers on collaboration among health care professionals, educators, and community organizations (Cohen Ross et al., 2019; Cornell, 2019). Pediatricians, child psychologists, and experienced parenting coaches work in tandem to provide evidence-based strategies and practical advice on various aspects of child-rearing. From addressing common concerns such as sleep routines, discipline techniques, and developmental milestones, to tackling more complex issues such as behavioral challenges and special needs, the program offers a comprehensive suite of services tailored to each family’s unique circumstances.

Early work focused on implementing an integrated platform, incorporating tools such as the Survey of Well-Being of Young Children, Well-Visit Planner, Promoting Healthy Development Survey, Welch Emotional Connection Screen, and FINDconnect (Cornell, 2019), and identifying 14 common practices for promoting

managing their young children’s behaviors (HealthySteps, 2024; Minkovitz et al., 2007; Piotrowski, Talavera, & Mayer, 2009). The Video Interaction Project, begun at New York University, uses video tapes of parent–child interactions also to help parents learn strategies to address their children’s behaviors and learn how to support the child’s development (Canfield et al., 2015; Mendelsohn et al., 2005, 2011; Video Interaction Project, n.d.). Reach Out and Read has a substantial evidence base, showing significant improvement in children’s literacy (High et al., 2000; Sinclair et al., 2019). More recent work has documented improvements in parenting stress and parent–child relational interactions (Canfield et al., 2020). All of these (and several other) innovations have developed good evidence for their effects on care and outcomes, and many have seen substantial growth in their uptake in pediatric primary care over the past decades. Nonetheless, as indicated in Chapter 6, financing has not transformed to support these key advances and bring them to scale.

socioemotional development (Center for the Study of Social Policy & Pediatrics Supporting Parents, 2018; Cornell, 2019). Later work has aided practices with strategies for implementing and financing these changes (CSSP, 2018).

Two California programs exemplify the lessons from the earlier PSP work. Built in part on specific California benefits that support whole family health and dyadic care for young families, these two programs have enhanced connections of primary care with other early childhood activities. The LIFT/ACEs LA Medical-Financial Partnership (MFP) and Network of Care addresses the complex social and financial situations of low-income and working-class families by providing clinic-based financial coaching (Bell et al., 2020; Holguin et al., 2023). Existing studies, while limited, have shown that MFPs improve both health outcomes and family finances (Bell et al., 2020; Holguin et al., 2023). The MFP approach provides structured financial counseling and helps families identify their strengths, priorities, goals, and actionable steps aimed at improving economic stability. The University of California, Los Angeles’s MFP assists with connecting families to resources that can assist them in navigating social systems and structures that can otherwise prove prohibitively difficult to engage with. The MFP helps affiliated clinics develop and maintain networks of financial and social resources, which are available to all families served at the clinics (Holguin et al., 2023; Spiker, 2023).

The University of California, San Francisco Center for Child and Community Health and the Ready! Resilient! Rising! (R3) Network serve to transform early childhood health care for low-income children. R3 includes educators, health plans, health providers, and social service agencies collaborating to improve whole child health through trauma-informed screening for basic needs and expanded behavioral health care in pediatric primary care. These trauma-informed programs create pathways for families to combat and overcome toxic stress in early childhood.

Increasingly, the medical home model has moved to team-based care, supporting the changing and expanding content of pediatric primary care

BOX 5-2

Models Supporting Early Child Wellbeing in Pediatric Primary Care

Several programs have innovated models for strengthening pediatric teams and staffing in early childhood care. Each helps pediatric primary care transform to team-based care.

DULCE

Developmental Understanding and Legal Collaboration for Everyone (DULCE) is a team-based approach to pediatric care that transforms how families experience health care (Center for the Study of Social Policy [CSSP], n.d.). Based in the pediatric care setting, it proactively addresses social determinants of health, promotes the healthy development of infants, and provides support to their parents during the critical first 6 months of their child’s life (Center for the Advancement of Youth [CAY], n.d.). DULCE introduces into the care team a family specialist trained in child development, relational practice, and problem solving. Family specialists attend well-child visits with families and providers, get to know the families, provide peer support, and collaborate with the team to connect families with resources and support. The DULCE program includes family specialists, medical providers, legal partners, early childhood systems representatives, and mental health representatives, along with a project lead and a clinic administrator. By addressing the accumulated burden of social and economic hardship, the DULCE team reduces family stress, giving families more time and energy to bond with and care for their new child (Monahan, McCrae, & Arbour, 2024). The DULCE approach to social determinants of health recognizes the inequities in the distribution of power and resources, rooted in a history of racism (McCrae et al., 2021), and uses community health models to create a more equitable distribution of power and resources (CAY, n.d.; CSSP, n.d.a,b).

HealthySteps

HealthySteps is a three-tiered model that integrates developmental and behavioral services into pediatric primary care for children from birth to age 3 years (HealthySteps, n.d.b, 2022; Piotrowski, Talavera, & Mayer, 2009; Valado et al., 2019). It employs HealthySteps specialists, who are experts in child development and behavioral health, to work alongside pediatric providers. These specialists offer services such as developmental screening, positive parenting guidance, care coordination, and referrals to community resources. Evaluations have provided evidence for the model’s effectiveness in promoting healthy child development and family wellbeing (HealthySteps, 2022; Piotrowski, Talavera, & Mayer, 2009; Valado et al., 2019). HealthySteps improves the quality of care and the capacity of pediatric practices to operate as institutional resources within their communities (Barth, 2010; Valado et al., 2019). The model also improves child health outcomes, including breastfeeding rates, age-appropriate nutrition, timely developmental screening and intervention, and socioemotional development (HealthySteps, 2022; Piotrowski, Talavera, & Mayer, 2009; Valado et al., 2019). Other findings include enhanced parenting practices and maternal mental health (Forum on Promoting Children’s Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Health, 2014; Minkovitz et al., 2003, 2007; Valado et al., 2019).

Help Me Grow

Help Me Grow (HMG) leverages and expands upon existing resources to create a comprehensive approach to early childhood system-building within any community (HMG National Center, n.d.). The model provides a centralized access point to enhance utilization of existing community resources rather than creating new programs. Research shows HMG positively impacts child and parent factors by improving understanding of child development and increasing access to supportive services (Bogin, 2006; Dworkin & Kelly, 2022; Hill & Hill, 2018; HMG National Center, 2023; Hughes et al., 2016; Therriault et al., 2021). The model integrates with broader child and family-serving systems, addressing complex social needs that impact development. HMG employs targeted universalism to ensure equitable access to quality services. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention endorsed HMG as a strategy for achieving equity, which bolsters the model’s foundation in targeted universalism and supports its validity and importance (Robinson et al., 2017).

Reach Out and Read

The Reach Out and Read program is a nationally recognized early literacy intervention implemented in pediatric primary care settings across the United States (Garbe et al., 2023; Klass, Dreyer, & Mendelsohn, 2009). Founded on the principle that promoting early literacy is essential for children’s cognitive and socioemotional development, the program integrates literacy promotion into routine pediatric visits by providing developmentally appropriate books to children during well-child checkups and offering guidance to parents on the importance of reading aloud (Garbe et al., 2023; Miller et al., 2023). Participation in Reach Out and Read is associated with numerous positive health outcomes, including improved language and literacy skills, enhanced parent–child bonding, increased school readiness, and reduced developmental disparities among children from low-income families (Garbe et al., 2023; Jimenez et al., 2023; Klass, Dreyer, & Mendelsohn, 2009; Needlman et al., 1991).

PlayReadVIP

PlayReadVIP, originally known as the Video Interaction Project, is an evidence-based parenting program developed by a team at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine (NYU Langone Health, n.d.; PlayReadVIP, 2024). The program aims to enhance early child development and literacy by utilizing videotaping and developmentally appropriate toys, books, and resources to help parents engage in pretend play, shared reading, and daily routines with their children (Center for Parents & Children, n.d.; Institute of Human Development and Social Change, n.d.). PlayReadVIP sessions involve one-on-one coaching during routine well-child visits where parents receive feedback on their interactions with their children. Participation in PlayReadVIP improves children’s socioemotional, cognitive, and language development (Cates et al., 2018; Mendelsohn et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2023; Piccolo et al., 2023; Roby et al., 2021), increases parental engagement, and reduces parenting stress and depression (Berkule et al., 2014; Canfield et al., 2023; Cates et al., 2016; Miller, 2023). The program’s integration into pediatric primary care provides a strategic platform for reaching high-risk families and promoting school readiness skills among low-income children.

by basing care in a multidisciplinary team. Teams support more care for behavioral and developmental needs, coordination of care with greater numbers of children and youth with chronic health conditions, and connection to community resources for nonmedical drivers of health. Well-designed team-based models optimize existing resources and personnel to deliver care and leverage the expertise of all team members; address the total whole person needs of the community; and focus on the upstream drivers of health, disease prevention, and health promotion (National Academies, 2023a). Team-based health care has been linked to improved health care quality, patient outcomes, and cost savings, with increasing evidence that it also improves clinician wellbeing (Jacob et al., 2015; Pape et al., 2011; Roberts et al., 2001; Tiel Groenestege-Kreb, van Maarseveen, & Leenen, 2014).

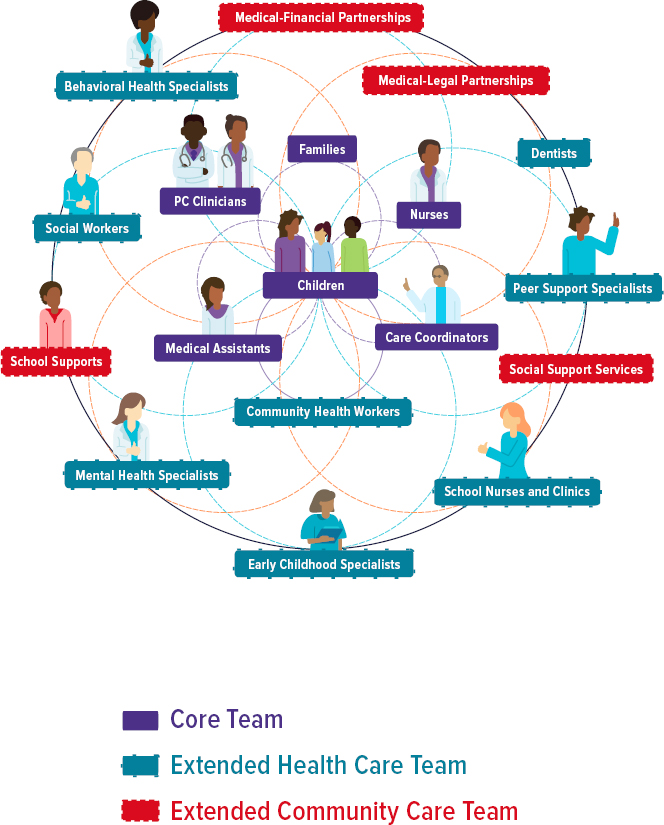

Traditional pediatric office practices typically include one or more clinicians, with support from nurses or medical assistants, and office staff. Extended teams include a variety of additional staff (often depending on community needs) that may include advanced practice nurses (to help coordinate chronic care), mental and behavioral health professionals, and community health workers, as well as care managers, interpreters, nutritionists, lactation specialists, school liaison staff, health educators, health coaches, and attorneys and other medical–legal partnership staff. Figure 5-2 provides examples of an extended health care team and extended community care team, with the patient and the family at the center of the core team.

Team approaches to care, when adequately staffed and resourced, have many benefits in clinical settings. For example, team-based care is associated with reduced workload, increased efficiency, improved quality, improved patient outcomes, reduced fragmentation, and decreased clinician burnout and turnover (National Academies, 2019e, 2021b). Expanding teams addresses some of the major time constraints faced by usual physician-run primary care—where time available to address social, community, and developmental issues can limit services. Well-designed teams can also support nurturing, longitudinal, person-centered care (Mitchell et al., 2012; Sullivan & Ellner, 2015), a key feature of high-quality primary care (National Academies, 2021b). Effective teams are designed to meet the specific needs of the communities they serve. Ideally, teams reflect the diversity of the communities they serve (Katkin et al., 2017) and evolve with the changing needs of the community over time (National Academies, 2021b, p. 182; see also Bodenheimer, 2019; Bodenheimer & Smith, 2013; Brownstein et al., 2011; Coker, Thomas, & Chung, 2013; Coker et al., 2009, 2014; Fierman et al., 2016; Grumbach, Bainbridge, & Bodenheimer, 2012; Katkin et al., 2017; Margolius et al., 2012).

Recent studies have shown the particular value of community health workers (and related workers such as peer counselors and family coaches) in improving health and outcomes (Bruner & Kotelchuck, 2023). Reviews of studies (though mainly among adult populations) found improved treatment adherence and decreased hospitalization and more attention to social

NOTE: PC = primary care.

SOURCE: Adapted from National Academies, 2021b.

determinants of health (Kangovi et al., 2020; National Academies, 2021b; Vasan et al., 2020). The PARENT intervention has documented how family coaches reduced emergency department use and increased preventive care services (Coker et al., 2016; Mimila et al., 2017).

The extended community care team in Figure 5-2 involves clinical–community partnerships and cross-sector, multidisciplinary programs such as medical–legal and medical–financial partnerships, clinic-based food pantries, and embedded and school behavioral health services. Screening for child and family needs and social determinants of health have accompanied

BOX 5-3

Medical–Legal Partnerships (MLPs)

MLPs integrate legal advocates into health care settings to address health-related social needs of the child and family. There are more than 400 MLPs across the United States where legal advocates work with clinicians to co-design social risk screening, educate health care professionals about legal remedies, and intervene to address health-harming legal issues (e.g., housing, public benefits, utilities, educational needs; Beck et al., 2021). Legal advocates are powerful allies in driving upstream changes to promote health, and MLPs enable broader, system-level pattern recognition and advocacy in pursuit of health equity and justice. A retrospective cohort study examining the effect of referral to an MLP on hospitalization rates among urban, low-income children in Greater Cincinnati, Ohio, found that the median predicted hospitalization rate for children in the year after referral was almost 40% lower if children received the legal intervention than if they did not (Beck et al., 2022). Clinicians report that MLPs also increase their self-efficacy for addressing child and family needs by improving their awareness of the social determinants of health and health-harming legal issues, empowering them to engage in systemic advocacy and improving their relationships with patients’ families (Murillo et al., 2022).

team-based care. However, the effect of such screening is often limited without further assistance with referrals, navigation supports for families, and monitoring of follow-up. When linked to facilitated referrals, a comprehensive program can help families increase access to community services. Systematic screening and closed-loop referrals for social determinants during well-child care lead to larger initial enrollment in community resources for families (Garg et al., 2015). Box 5-3 describes the growth of medical–legal partnerships to support pediatric transformation addressing social determinants of health.

While there is compelling evidence that team-based approaches to primary care can foster high-quality, efficient, continuous, and relationship-based care (National Academies, 2021b), making the transition to a team-based approach to care delivery often requires additional support. Many practices—especially independent small to medium-sized practices and those located in resource-limited communities—find the transition challenging, both logistically and financially. Dominant fee-for-service payment offers few incentives for this transformation, not only in terms of paying for additional multidisciplinary team members, but also in terms of financing the development of the clinic-level infrastructure needed to make the shift to team-based delivery. Most team-based care expansions have come from a combination of some billed services (especially for mental and behavioral treatments), grants, and philanthropy (Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2023a). A few state Medicaid programs have allowed billing for various nonphysician personnel or have restructured payment with

incentives to develop team-based care (MassHealth, 2022). Additionally, in 2023, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (2023c) implemented rule changes designed to improve equity, including a change that makes it easier to cover community health workers on care delivery teams. Most, but not all, states currently allow Medicaid payment for community health workers (see Box 5-4; Haldar & Hinton, 2023).

BOX 5-4

Community Health Workers (CHWs)

CHWs have critical roles in improving access to health care and addressing social determinants of health for children and families, particularly in underserved communities. CHWs serve as trusted liaisons between health care systems and the communities they serve, bridging cultural and linguistic gaps, and providing culturally appropriate support and education (Coker et al., 2016; Rogers et al., 2023). In pediatric care settings, CHWs support caregivers of children with special health care needs, helping them understand and manage their child’s condition, navigate the health care system, and address clinical and social needs (Moheize et al., 2024). CHWs and family coaches have helped reduce hospitalizations and emergency department visits for children with asthma, promoting medication adherence, and empowering families to better manage chronic conditions (Costich et al., 2019). By connecting families with community-based organizations and resources, CHWs address social determinants of health, including transportation, food insecurity, housing instability, and financial strain (Costich et al., 2019; Moheize et al., 2024; Rogers et al., 2023).

Peer- and family-support specialists are nontraditional workforce additions who can also help teams provide comprehensive support and improve health outcomes (Hayhoe et al., 2018; Malcarney et al., 2017; Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2007). Peer-support specialists are individuals with lived experience of mental health conditions or substance use disorders who use their personal recovery stories to inspire hope, provide emotional support, and assist others in navigating the recovery process. They facilitate support groups and skill-building activities, and advocate for individuals’ needs and rights, promoting self-determination and empowerment. Research has shown that peer-support services can improve engagement in treatment, reduce hospitalizations, and enhance overall recovery outcomes (Hayhoe et al., 2018; HHS, 2007; Malcarney et al., 2017).

Family-support specialists, also known as family peer advocates or family partners, are caregivers or family members of individuals with disabilities, mental health conditions, or other special health care needs (National Indian Child Welfare Association [NICWA], 2014; Robertson et al., 2023; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2017). They leverage their personal experiences to support other families by providing emotional understanding, helping them navigate complex service systems, advocating for family-centered care and rights, facilitating peer-support groups and skill-building workshops, and promoting family empowerment and self-advocacy. The involvement of family-support specialists has been associated with improved family functioning, increased access to services, and better outcomes for children with special health care needs (NICWA, 2014; Robertson et al., 2023; SAMHSA, 2017).

Still, many practices, particularly small and medium-sized independent practices, face both space limitations and difficulty finding needed multidisciplinary personnel, especially in rural areas. Workforce demands and burnout have especially affected the supply of mental and behavioral health personnel. One tactic that small and medium-sized practices can take is banding together to pool resources and sharing certain personnel or community resources (e.g., social services) across multiple practices (Mostashari, 2016).

MENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS AND SETTINGS

The mental health care system is also diverse, including multiple settings, with limited coordination among the several sectors involved. Behavioral health services are provided across six general sectors: behavioral health care systems, schools, child welfare, substance abuse services, medical and primary care clinics, and juvenile justice. Services focus on treatment rather than prevention and often do not meet the basic population-level behavioral health needs of children and youth in the communities they serve (American Psychological Association Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice for Children and Adolescents, 2008).

Traditional models of outpatient mental health services may focus primarily on mental health diagnosis and its intra- and interpersonal complications rather than on the interaction of a diagnosis with physical health and health-maintenance behaviors. Services may take place in the offices of a physician, psychologist, social worker, or mental health counselor and increasingly virtually. Often, such mental health services are out of network or paid for out of pocket, as finding in-network behavioral specialists, particularly psychiatrists, can be more difficult than finding other types of specialists (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2016, 2017; Overhage et al., 2024).

Other settings may involve a multidisciplinary team of professionals—including psychologists, psychiatrists, developmental and behavioral pediatricians, social workers, and therapists—who collaborate to provide assessment, diagnosis, and treatment (Haines et al., 2018). Clinics may be publicly funded as community mental health centers or may take only commercial insurance (or private pay). Clinics often tailor therapeutic interventions to each child’s specific concerns, utilizing evidence-based approaches such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and play therapy (Bhide & Chakraborty, 2020; Hoagwood et al., 2001; Kaminski & Claussen, 2017). Additionally, these settings may offer medication management as needed. With an emphasis on creating a supportive and nurturing environment, clinicians strive to empower children to explore their emotions, develop coping skills, and foster resilience (Masten & Barnes, 2018; Ronen, 2021). Family involvement is often encouraged to promote holistic healing and facilitate long-term stability and wellbeing for the child (Berger

& Font, 2015; Hogue et al., 2021). Regular monitoring and follow-up ensure that interventions remain effective and adaptable to the child’s evolving needs (Almirall & Chronis-Tuscano, 2016; Colizzi, Lasalvia, & Ruggeri, 2020). Disparities in access for children seeking mental, emotional, and behavioral health care in the United States stem from differences in insurance coverage, geographic availability of services, cultural barriers, and stigma, leading to unequal access to care based on financial resources, location, ethnicity, and perceptions of mental illness (Hoffmann et al., 2022; Mongelli, Georgakopoulos, & Pato, Toure et al., 2022).

School-based mental health programs have emerged as integral components of the children’s mental health care system, providing on-site counseling services, behavioral interventions, and crisis support to students within the familiar environment of their educational settings (see Chapter 8). These programs facilitate early identification and intervention for mental health issues and promote collaboration among educators, mental health professionals, and families to create supportive learning environments conducive to emotional wellbeing.

Inpatient psychiatric treatment provides acute care for those experiencing serious mental health and/or behavioral concerns that require a higher level of care for safety, treatment management, and supervision. Inpatient care provides intensive treatment services ranging from milieu therapy to medication management and a high level of supervision in a restricted, controlled environment. Children and youth may be hospitalized at the recommendation of a physician, mental health provider, or family following assessment. Follow-up outpatient therapy and services are essential for continued stabilization and alleviation of symptoms following inpatient psychiatric treatment, including residential treatment and other options.