Launching Lifelong Health by Improving Health Care for Children, Youth, and Families (2024)

Chapter: 6 Insurance and Other Financing for Clinical Services

6

Insurance and Other Financing for Clinical Services

Long-term fiscal effects of Medicaid spending on children could offset half or more of the program’s initial outlays.

—Congressional Budget Office1

As discussed in prior chapters, children’s health care includes proactive care designed to prevent disease and promote health, as well as medical care designed to screen, diagnose, and treat health conditions. The former is often referred to as “primary prevention” and the latter as “secondary prevention” (identifying conditions as soon as possible); “tertiary prevention” is managing and minimizing consequences of worsening conditions. The nation’s investment in children’s health care, from primary to tertiary prevention, is financed through multiple and interweaving funding streams; a central example is commercial and public health insurance. Another stream occurs outside of the insurance mechanism through the federal grant-in-aid system for community and state initiatives related to child health.2 See Table 6-1 for an overview of federal investment in children’s health through insurance, health clinics, population health initiatives, and school-based services.

Federal funding for all health care programs in the United States leans heavily on insurance mechanisms. Funding for Medicare, Medicaid, and other health insurance assistance was $1.7 trillion in 2022, whereas other health-related expenditures totaled $242 billion, excluding U.S. Department

___________________

2 The grant-in-aid system of federal support to states and communities includes several types of mechanisms, such as categorical grants, block grants, and general revenue sharing (Congressional Research Service, 2019).

TABLE 6-1 Major Federal Investments Addressing Children and Youth Health and Wellbeing

| Program | Federal Agency | Appropriation, in billions | Fiscal Year | % to Children and Mothers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance Mechanisms and Clinical Care Services (discussed in this chapter) | ||||

| Medicaid | CMS/HHS | $699 | 2021 | 15.2% |

| Children’s Health Insurance Program | CMS/HHS | $15.8 | 2021 | 100% |

| Tax subsidies for employer-sponsored health insurance | ~$299 | 2022 | ||

| Community health centers (federally qualified health center/rural health clinic/look-alike) | HRSA/HHS | $5.6 | 2022 | 12% |

| Certified community behavioral health clinics | SAMHSA/HHS | $0.3 | 2022 | 27% (upper limit) |

| School-based health centers | HRSA/HHS | $0.03 | 2023 | 100% |

| CMS/HHS | $0.05 | 2024 | ||

| Indian Health Service | IHS/HHS | $6.96 | 2023 | NA |

| Public Health Initiatives (Child Care, Maternal and Early Child Health Care, Vaccines, Nutrition, Mental Health (treatment for stress, trauma, substance use disorder) (discussed in Chapter 7) | ||||

| Child care and development block grant | ACF/HHS | $5.9 | 2022 | 100% |

| Head Start (HS), Early HS, American Indian/Alaska Native HS, Migrant Worker HS | ACF/HHS | $11 | 2022 | 100% |

| Vaccines for children | CDC/HHS | $5.5 | 2022 | 100% |

| National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities | CDC/HHS | $0.2 | 2022 | 100% |

| Preventive Health and Health Services Block Grant | CDC/HHS | $0.1 | 2020 | ~29% |

| Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health | CDC/HHS | $0.04 | 2022 | NA |

| Good Health and Wellness in Indian Country | CDC/HHS | $0.04 | 2022 | NA |

| Maternal and Child Health Block Grant (Title V) | HRSA/HHS | $0.7 | 2022 | NA |

| Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting | HRSA/HHS | $0.2 | 2022 | NA |

| National Child Traumatic Stress Initiative | SAMHSA/HHS | $0.08 | 2022 | 100% |

| Program | Federal Agency | Appropriation, in billions | Fiscal Year | % to Children and Mothers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residential Treatment for Pregnant and Postpartum Women | SAMHSA/HHS | $0.03 | 2022 | 100% |

| Project LAUNCH (Linking Actions for Unmet Needs in Children’s Health) | SAMHSA/HHS | $0.02 | 2022 | 100% |

| Tribal Behavioral Health Grants | SAMHSA/HHS | $0.02 | 2022 | NA |

| Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Grants | SAMHSA/HHS | $0.01 | 2022 | 100% |

| Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program | FNS/USDA | $120 | 2022 | 44% |

| Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children | FNS/USDA | $6.9 | 2022 | 100% |

| School-Based Services (health promotion, nutrition, management of chronic conditions) (discussed in Chapter 8) | ||||

| Healthy Schools Initiative | CDC/HHS | $0.02 | 2022 | 100% |

| National School Lunch & Breakfast programs | FNS/USDA | $26.9 | 2022 | 100% |

| Child and Adult Care Food Program | FNS/USDA | $3.9 | 2022 | High |

NOTES: This table lists major federal investments; many other, smaller programs also invest in child and youth health and wellbeing. ACF = Administration for Children and Families; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; FNS = Food and Nutrition Service; HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; IHS = Indian Health Service; NA = not available or not applicable; SAMHSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture.

SOURCE: Generated by the committee.

NOTES: This table lists major federal investments; many other, smaller programs also invest in child and youth health and wellbeing. ACF = Administration for Children and Families; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; FNS = Food and Nutrition Service; HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; IHS = Indian Health Service; NA = not available or not applicable; SAMHSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture.

SOURCE: Generated by the committee.

of Defense (DoD) and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Care.3 Another $287 billion in federal support goes to employer-sponsored health insurance through tax subsidies (Congressional Budget Office [CBO], 2019). This heavy reliance on insurance as a funding stream impacts how care is organized by valuing disease-focused medical services (delivered one-to-one) over universal or wellness-focused prevention services (delivered

___________________

3 Per the Office of Management and Budget (n.d.), Table 15.1, “Outlays for Health Programs: 1962–2028 (in billions)”: Medicare ($905.6), Medicaid ($591.9), Federal Employees Health Benefits Program ($61.0), health insurance assistance ($79.5), other health ($24.02); excludes DoD ($55.4) and VA ($110.7).

one-to-many), which traditionally do not fit well into insurance models. Over the past four decades, the United States significantly expanded its investments in child health care through the health insurance financing mechanism to provide insurance coverage to all children. By 2015, health insurance coverage for children had stabilized at 95% in 2021 (Keisler-Starkey & Bunch, 2022; Census Bureau, 2021), although the pandemic increased coverage slightly, followed by the recent “unwinding” of Medicaid eligibility with the end of the pandemic public health emergency that reduced rates of children’s coverage.4 This coverage is a major policy success for children, yet the overall picture in the nation masks areas and populations with larger uninsured rates, such as children in the South (6.8%) and in states that have not expanded Medicaid (8.1%), as well as Hispanic children (9.5%) and children who are foreign born (22.6%) (see Figure 4 in Census Bureau, 2023b).

Changes to insurance coverage and financing are more likely to impact disease-focused than wellness-focused services. The share of spending through insurance as opposed to other funding streams varies depending on the type of care—primary, secondary, or tertiary prevention. The majority of secondary and tertiary prevention is delivered through the health care system and financed through insurance. By contrast, primary preventive health care can be delivered through the health care system and financed through insurance, but it is also delivered outside of the health care system and paid for with federal grants-in-aid.

The terms “clinical primary prevention” and “community-” or “population-based primary prevention” highlight the distinction in the delivery and financing of primary preventive care (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2010). Clinical primary prevention usually involves services that are delivered one-to-one in a medical office setting by health care professionals and are covered by insurance and/or out-of-pocket payments by those receiving the services. Community-based primary preventive health care services can be provided one-to-one or one-to-many—such as a teacher providing socioemotional learning to a class of students, a community health worker providing multigenerational care to a family unit, or a community program or intervention sponsored by a local health department—and often involve health care delivered by nonmedical professionals, such as community health workers, peers, teachers, and other community members (Cuellar & Calonge, 2022). As discussed in Chapter 7, financial support for community-level services comes from federal grants, in addition to local and state

___________________

4 Insurance coverage for children was 0.6% higher in 2021 than in 2020 because of congressional efforts to retain access to insurance during the COVID-19 pandemic (Mykyta, Keisler-Starkey, & Bunch, 2022). With the unwinding, coverage has returned to prepandemic levels.

funding mechanisms. These definitional boundaries are soft, the actors can overlap, and the multiplicity of actors and types of activities speaks to the importance of coordination and communication across clinical and community services.

The long horizon of some investments in children’s health has implications for framing strategies for federal budgeting and fund allocation across competing priorities. In scoring the fiscal impact of federal legislation, CBO has generally considered savings within only a 10-year projection period based on its statutory requirements. This long-standing approach leads to undervaluing longer-term investments and disproportionately impacts fiscal calculations around prevention in general and child health investments in particular (Ash et al., 2023; CBO, 2020). CBO can score legislation across multiple budgets, not limited to health care, and doing so could improve results for Medicaid and other investments. Lack of CBO outlays by age group also hampers assessment of investments and returns for children.

At the national level, spending on primary prevention is aimed at protecting against poor future health states among the nation’s population and their attendant costs. While not all health conditions are preventable, many have modifiable risk factors. Health care costs associated with such conditions are substantial. For example, a recent Lancet analysis estimated that in 2016, U.S. health care spending attributable to modifiable risk factors—including high body mass index, high blood pressure, high glucose, dietary risks, and tobacco use—was $730.4 billion, or 27% of total health care spending. Some of these costs are paid publicly through programs such as Medicare and Medicaid (Bolnick et al., 2020). Another example is mental health disorders, which are among the costliest of health conditions in terms of health care spending (Roehrig, 2016). Moreover, poor mental health in childhood has a range of lasting impacts on later-life outcomes, ranging from educational completion to employment and early death (Currie & Stabile, 2006; Fletcher & Wolfe, 2008, 2009; Goodman, Joyce, & Smith, 2011; Salm & Schunk, 2012; Wang, Frank, & Glied, 2023). Thus, federal spending on primary prevention can be seen as insurance against future costs for both health and nonhealth care (e.g., productivity) that can be attributed to preventable conditions.

This chapter’s discussion of spending on children’s health care focuses on clinical care funded mainly by insurance. Chapter 7 examines the role of investment in child health through population- and community-level primary prevention.5

___________________

5 As a practical matter, drawing a line between what spending falls into public health (related to social determinants of children’s health) and what spending can be construed more narrowly as health care spending can be fraught.

HEALTH INSURANCE FOR CHILDREN

Health and medical care provided to children on an individual basis is paid for primarily through health insurance. Today, although some communities continue to have low rates of coverage, in many communities, nearly all children have health insurance coverage, the result of a series of child-related health policies spanning six decades (Cohen, Martinez, & Zammitti, 2015). This policy achievement has removed a major barrier to health care for most children and has positive short- and long-term health and education impacts. Remaining issues with primary insurance for children pertain to those who lack coverage, including undocumented children; intermittent loss of coverage; coverage for parents; access to providers willing to accept insurance, especially for children with Medicaid and for behavioral health and dental care; underinsurance, especially for middle-income children; and limitations of certain provider payment mechanisms.

Importance of Health Insurance for Children

Research has examined whether health insurance coverage improves short- and long-term child outcomes, largely based on expansions in Medicaid (Brown, Kowalski, & Lurie, 2015; Currie & Chorniy, 2021; Hakim, Boben, & Bonney, 2000; IOM, 1998; KFF, 2023b; Meyer & Wherry, 2012; Wherry et al., 2015). For example, a 1998 IOM report, America’s Children: Health Insurance and Access to Care, provided substantial evidence of the value of health insurance for children’s health. Buchmueller, Levy, and Valletta (2019) summarized the literature related to Medicaid expansions for children, concluding that the Medicaid expansions for children increased coverage, net of any reductions in commercial insurance due to crowd-out, and also increased access and utilization of care for children. Other studies found improvements in school achievement (Wehby, 2022). Early studies on Medicaid coverage expansions for pregnant women in the 1980s concluded that the expansions increased enrollment and modestly improved birth outcomes, but showed mixed evidence on prenatal outcomes (Howell, 2001). Improvements were greatest for families with very low incomes (Bellerose, Collin, & Daw, 2022; Currie & Gruber, 1996; Howell, 2001).

More recent studies have assessed the long-term impacts of the Medicaid expansions on children, suggesting that Medicaid plays an important role not only in increasing utilization of health care at young ages, but in improving health outcomes over the long term (Currie, Decker, & Lin, 2008; Miller & Wherry, 2019; Thompson, 2017). Studies have also found that Medicaid eligibility in childhood improves labor market and educational outcomes, including high school and college completion (Brown et al., 2020; Cohodes et al., 2016; Currie & Chorniy, 2021; Groves, 2020; Miller & Wherry, 2019; Wherry et al., 2015). The mechanism by which Medicaid eligibility at young ages drives these

long-term effects is not entirely clear, but candidate explanations include direct impacts of health insurance on health care and improved maternal physical and mental health (Guldi & Hamersma, 2023) and birth outcomes. Indirect explanations could include increased access to treatment for substance use disorder and decreased crime (Wen, Hockenberry, & Cummings, 2017); lower financial strain and stress on mothers or families, including reductions in mother’s employment changes during early childhood; increased connection to other social supports; and decreased rates of poverty (Aizer, Stroud, & Buka, 2016; Currie & Duque, 2019; Currie & Rossin-Slater, 2015; Sommers & Oellerich, 2013; Wherry, Kenney, & Sommers, 2016). As noted above, many of these longer-term impacts are not captured within the time frame in which legislation is proposed and scored in Congress. A recent CBO report modeled how a different approach could take these economic and budgetary gains into account explicitly and thus enable more comprehensive fiscal assessment of proposals to change health insurance for children (Ash et al., 2023).

Overview of Children’s Health Insurance

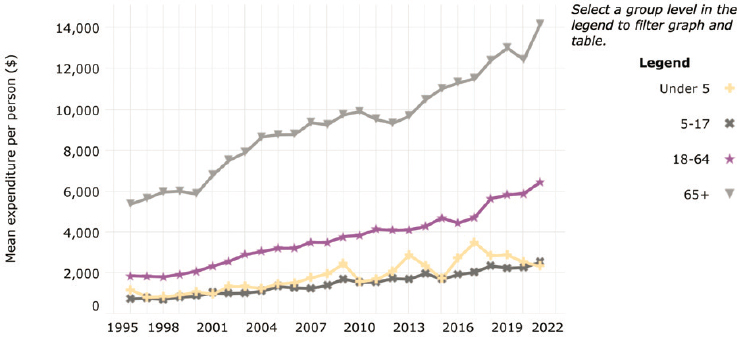

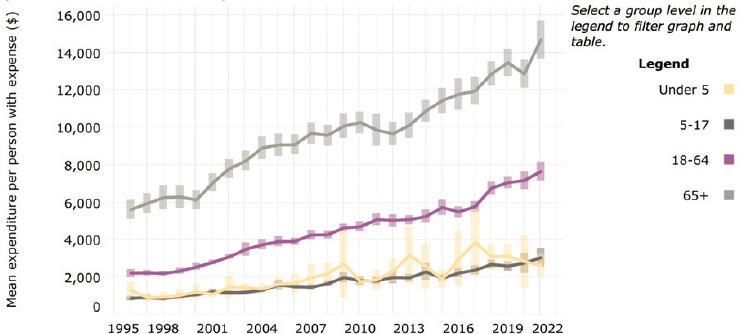

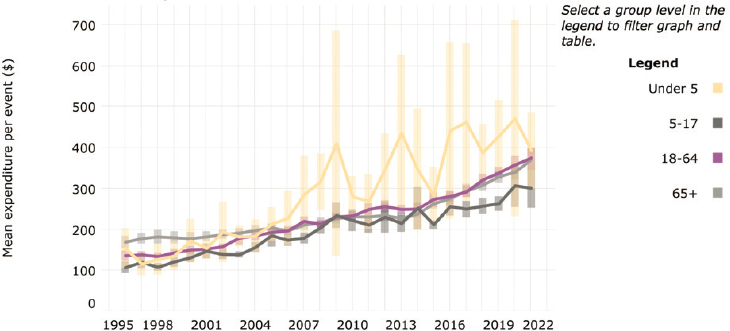

To clarify the role of health insurance for children, it is important to understand that children’s medical expenditures are, on average, very low (Figure 6-1), even among those with any expense (Figure 6-2), and much lower than for adults. Children under age 5 years who have a medical expense have higher spending than children ages 5–17, in part because of the high cost of some births. At the same time, as Figure 6-3 shows, conditional on having a medical event, the mean cost of a medical event can be very high, even for children.

NOTE: Confidence interval is 95%.

SOURCE: AHRQ Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (https://datatools.ahrq.gov/meps-hc).

NOTE: Confidence interval is 95%.

SOURCE: AHRQ Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (https://datatools.ahrq.gov/meps-hc).

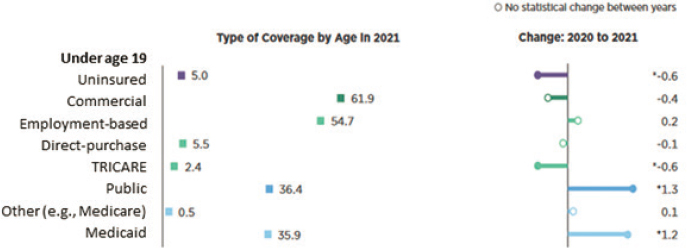

More than half of children (54.7%) have commercial health insurance through a parent’s employer-sponsored plan. In some cases, employees pay the full premium costs and in other cases employees share the premium costs with their employers; however, employer premium contributions can also be viewed as being paid for by the employee in the form of reduced wages. In general, employers subsidize employee coverage at a higher rate than they subsidize dependent coverage. Employer-provided health insurance is also

NOTE: Confidence interval is 95%.

SOURCE: AHRQ Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (https://datatools.ahrq.gov/meps-hc).

SOURCE: Based on data from the Current Population Survey; Keisler-Starkey & Bunch, 2022.

publicly subsidized through foregone tax revenue because these benefits are not considered taxable income. CBO (2019) and the Joint Committee on Taxation estimate that federal subsidies via tax benefits for employer-covered insurance for all ages totaled $287 billion in 2019, almost as high as the $314 billion in federal subsidies for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).6 Another 5.5% of children are covered through direct-purchase commercial insurance (Keisler-Starkey & Bunch, 2022; see Figure 6-4). Since implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010), children are eligible for health insurance coverage as a dependent on a family’s plan that is purchased directly from the insurer or through a federal or state health insurance marketplace (e.g., healthcare.gov). Premiums for these plans can be paid for privately by a family or may be subsidized publicly, depending on the family’s income level, and thus combine private and public funding. Since 2019, the share of children with employer-sponsored or direct-purchased coverage has been stable, while Medicaid coverage increased especially during the pandemic (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2023a).

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, just over one-third of U.S. children (36.9%) had health insurance coverage through one of two publicly funded health insurance programs: Medicaid, which is targeted to low-income and/or disabled children, and CHIP, created in 1997, which is targeted to children in families with somewhat higher income levels (CMS, n.d.b, 2024f). With the COVID-19 public health emergency and changed Medicaid rules, that percentage rose to over 50% (35.1 million on Medicaid; 4.3 million on CHIP). With the end of the public health emergency and the related “unwinding” of Medicaid coverage, that number decreased by about 3.8 million as of February 2024.7

___________________

6 These estimates include children and adults under age 65.

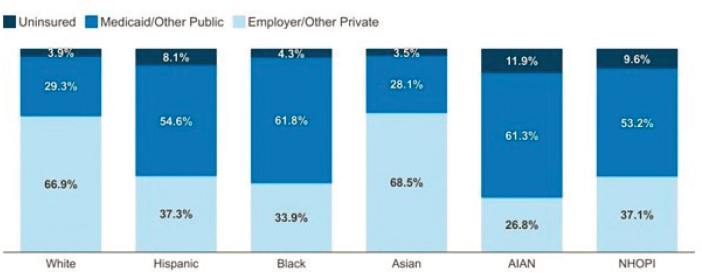

The mix of public and commercial insurance for children is anything but uniform. In 2021, 58.7% of non-Hispanic Black or American Indian/Alaska Native children had public coverage, as did 38.1% of non-Hispanic multiracial children, 53.7% of Hispanic, 28.0% of non-Hispanic Asian children, and 28.1% of non-Hispanic White children (Branch & Conway, 2022). The differences in public and commercial coverage across race and ethnicity likely arise from a combination of factors associated with systemic disadvantage, including income; type of parental employment; immigration policy; and geographic factors, such as living in the South, where few states have expanded Medicaid, or living in states where the marketplace exchange is enrolling potential beneficiaries less actively than other states (Snowden & Graaf, 2023).

Regardless of the funding of an insurance plan (commercial, public, or a combination), the costs of health care services provided are typically shared between the insurance plan and the enrollee through outlays for copayments, deductibles, and noncovered services. However, unlike other insurance products, Medicaid allows almost no copays or deductibles for covered services.

PUBLIC HEALTH INSURANCE FOR CHILDREN

Publicly funded insurance coverage for children has expanded in three major waves, based on families’ income levels and children’s ages. Initially, in 1965, Medicaid coverage was limited to children enrolled in welfare, as well as children who were blind or disabled. The link to public welfare meant that income eligibility was very low—well below the federal poverty level (FPL). From 1980 to 1990, Medicaid expanded incrementally to cover all children under the FPL (National Research Council & IOM, 1998). Under the Balanced Budget Act (1997), the newly established CHIP allowed states to cover children up to age 19 whose parents were working and had incomes above the state Medicaid levels; it also permitted states to collect premiums and copays from enrolled families for coverage. In 2014, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) created health insurance exchanges through which all individuals under age 65 with family incomes between 100% and 400% FPL became eligible for premium subsidies, and those with incomes below 250% FPL became eligible for reduced cost-sharing. Even though few children have direct-purchased commercial insurance through marketplaces, the broad-based enrollment activities supported by the ACA help both families and their children, with many families learning of their children’s eligibility for Medicaid through the ACA enrollment process. Furthermore, the ACA established a mandatory minimum Medicaid eligibility threshold for children at 133% FPL, regardless of the child’s age group. This shifted older children in some states from CHIP to Medicaid.8

___________________

8 Prior to the ACA, the mandatory eligibility levels for children in Medicaid differed by age: States were required to cover children ages 0–5 years in Medicaid with family incomes up to 133% FPL and children ages 6–18 years with family incomes up to 100% FPL (MACPAC, n.d.).

Arguably, the COVID-19 public health emergency created a fourth wave of children’s health insurance coverage by expanding premium subsidies for families with incomes up to 600% FPL and incentivizing state’s continuous coverage for Medicaid and some CHIP programs. The extended Medicaid/CHIP coverage—under which enrolled persons stayed covered unless they voluntarily disenrolled, moved, or died—persisted for 3 years until passage of the Consolidated Appropriations Act (2022). Continuous coverage ended with states resuming eligibility assessments and coverage terminations as early as April 2023 (Wikle & Wagner, 2023). Under the law, states had up to 12 months to return to preemergency eligibility and enrollment operations, resulting in significant administrative chaos and lost coverage for eligible children (Bohra, 2023; Heberlein, 2023). The Consolidated Appropriations Act also requires Medicaid and CHIP to cover children up to age 19 who are enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP for 12 months continuously beginning January 2024 (Daugherty et al., 2024).

Medicaid and CHIP represent federal–state partnerships with joint funding but have different financing formulas. In both cases, the federal government, through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), provides the majority share of funds, a share that varies based mainly on the level of poverty in the state; this is called the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), which ranges from 50% to 83% (Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission [MACPAC], 2023a).9 States pay the remainder and, within federal parameters, they can manage their spending through decisions on eligibility, benefit scope, optional coverage, quality standards, and provider payment. In contrast, state CHIP programs are funded through a capped federal block grant to states, with an FMAP that is always higher than that of Medicaid. The corresponding fiscal commitment by states is also fixed.

Medicaid is an entitlement (i.e., states are required to enroll any eligible applicant). With the CHIP block grant, however, states can refuse enrollment once they reach the end of their grant funding. In contrast to CHIP, Medicaid is countercyclical, requiring more spending during recessions, but also offering greater protection when more individuals lose their jobs and poverty rates are higher. States are required to have balanced budgets, and the countercyclical nature of Medicaid is challenging for state governments, with increased demand and lower revenues in recessions. In the 2001 recession, the Great Recession, and the recent COVID-19 pandemic, Congress appropriated additional federal fiscal relief to state Medicaid programs to ameliorate the budgetary impact of these major economic disruptions (see, respectively, Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act, 2003; American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, 2009; Families First Coronavirus Response Act, 2020).

___________________

9 The FMAP was increased by 6.5 percentage points for 4 years from 2020 through 2023 as part of the federal COVID-19 pandemic response (Families First Coronavirus Response Act, 2020).

Medicaid

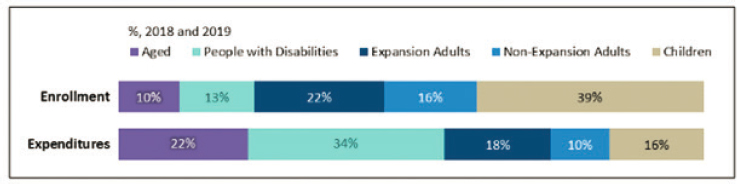

From the lens of Medicaid policy making, children are the largest group of Medicaid enrollees (39%), but they account for a smaller proportion of total spending than other groups (16%; Figure 6-5). All states currently offer Medicaid to low-income children. Child coverage is offered in 2 states for family incomes of 138–200% of FPL; in 30 states for 200–300% of FPL; and in 18 states and the District of Columbia for 300–405% of FPL. Some states offer coverage under federal options and others use “waiver authority” to expand coverage or add benefits to selected groups. For example, Michigan covers pregnant women and children up to 400% of FPL under waiver authority; five states have used the federal option to cover children with disabilities up to 300% of FPL (KFF, 2016; Musumeci et al., 2022).

As the major insurers of U.S. children and youth, Medicaid and CHIP provide a broad base of health insurance coverage for large numbers of children who would otherwise lack any health insurance. Children and youth of color are overrepresented among those with Medicaid coverage; thus, problems and progress in Medicaid and CHIP can either exacerbate or address major inequities in care and access (Michener, 2021). Medicaid improves equity by ensuring a strong health insurance base for large numbers of low-income children of color. As noted above, Medicaid coverage has been associated with a wide variety of short- and long-term improved

NOTES: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) calculated these figures for calendar years 2018 and 2019 using Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System data to determine the percentage of total Medicaid expenditures accounted for by each beneficiary category; it then applied that percentage to the net total Medicaid expenditures (federal and state) states reported to the Medicaid Budget and Expenditure System using form CMS-64. These national estimates include state-reported data from the 50 states; Washington, DC; Puerto Rico; and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Total net expenditures exclude spending for administrative expenses and Medicaid disproportionate share hospital payments. May not sum to totals due to rounding.

SOURCE: CMS, 2022b; Congressional Research Service, 2023b.

health outcomes, as well as lower health care costs and needs in later life—in these ways, it has improved equity. But Medicaid and CHIP have limitations that make access and care more difficult for many children; thus, they may exacerbate inequities too.

States have several choices or options in designing and implementing their programs. Although they must meet base CMS standards for income eligibility, provider payment, quality measures, and enrollment procedures, they have flexibility beyond these basic standards. State choices lead to major variations in all these items across state lines. Children’s access to services therefore depends on where they live and not so much on what they need. A child in Kansas City, Kansas, may need specialized services for a relatively rare chronic condition available in Kansas City, Missouri—but the Kansas Medicaid program network may not include the Missouri provider in its network, may not include the service among its benefits, and may restrict that child’s access to appropriate services. State variations, coupled with the geographic concentration of certain racialized communities, Black and Hispanic in particular, have led to significant racial inequities in both health insurance coverage and the services received by a Medicaid- or CHIP-enrolled child. States also have different standards of quality measurement, although, as of fall 2024, CMS (2024a) began requiring a minimum common set of child health measures for the states.

About 85% of children covered by Medicaid receive their basic coverage through a comprehensive managed care organization (MCO), rather than the traditional fee-for-service system (MACPAC, 2023a). Through these MCOs, states contract out many Medicaid functions, including elements of enrollment; provider credentialing, networks, reimbursement, and rate setting; quality reporting and monitoring; service authorization and grievance processes; and utilization review, among others. For comparison, 52% of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in managed care plans (MedPAC, 2023a,b,c). Unlike most children with Medicaid coverage, all Medicare beneficiaries can choose to stay in the traditional fee-for-service system or enroll in an MCO, where they can select among an average of 41 plan choices (MedPAC, 2023c). Medicaid beneficiaries are less likely to have a choice of plans. In both Medicare and Medicaid, MCOs are paid a fixed monthly amount per enrolled person, although the payment details differ. Medicaid MCOs must provide services in the same “amount, duration and scope” as would be available under Medicaid fee-for-service (Coverage and Authorization of Service, 2024) and may not deny care because of a patient’s diagnosis, type of illness, or condition. Whereas Medicare plans operate largely under uniform national rules set and overseen by CMS, Medicaid rules at the federal level are broader, giving states the flexibility to make key design decisions.

In choosing to privatize major program functions through MCOs, governments must balance giving MCOs the flexibility to innovate and at the

same time ensure efficiency, quality, and access. In the Medicaid managed care program, states fall along a continuum of specificity and flexibility. By law, however, a state’s managed care program must follow federal Medicaid rules and carry out all elements of the state’s approved Medicaid plan.

In some states, the MCO contract becomes a significant vehicle that details expectations and performance provisions and promotes accountability (Rosenbaum & Johnson, 2023). Once a contract is awarded, MCOs have substantial leeway in their interpretation of the federal and state rules. States vary substantially in public inclusion and transparency in developing and reviewing contracts, as well as their strategies and mechanisms for ensuring that MCOs meet their contractual obligations (MACPAC, 2022). Federal regulations require that states have a managed care monitoring system (42 CFR § 438.66), which addresses 14 areas ranging from enrollment to encounter data, provider networks and grievances, among others (State Monitoring Requirements, 2024). Several oversight entities have proposed greater uniformity and transparency in states reporting on key managed care provisions, such as payments and grievances (MACPAC, 2015a, 2022). In general, states and MCOs have provided little evidence regarding how MCOs have met their obligations, and few data exist to determine how well MCOs meet their requirements regarding benefits and coverage for children and youth. New and proposed CMS rules seek to address some of these issues (CMS, 2023d, 2024a; Lopez et al., 2020).

Medicaid Physician Payment Levels and Structures

By law, Medicaid programs should pay providers (physicians, hospitals, and others) sufficiently to produce participation—and ensure that access to care is comparable to that of the general population.10 Other than state affirmation, however, CMS has little documentation of how well states meet this requirement.

Medicaid fee-for-service rates tend to be lower than Medicare rates for similar procedures (Zuckerman, Skopec, & Aarons, 2021; Zuckerman, Williams, & Stockley, 2009). In part, these lower fees have a long history in Medicaid policy (Fein, 2015; Ford & Michener, 2022). In 2019, Medicaid physician fees for 27 common procedures were estimated to be 72% of Medicare physician fees, with the Medicaid-to-Medicare fee index lower for primary care (0.67) than for obstetric care (0.80; Zuckerman, Skopec, & Aarons, 2021). These comparisons have been published sporadically in the research literature (Rosenbaum,

___________________

10 See Social Security Act, State Plans for Medical Assistance (2024, § 1396a[a][30][A]): “payments are consistent with efficiency, economy, and quality of care and are sufficient to enlist enough providers so that care and services are available under the plan at least to the extent that such care and services are available to the general population in the geographic area.”

2014; Zuckerman, Skopec, & Aarons, 2021; Zuckerman, Williams, & Stockley, 2009), but the data are not routinely collected and made public by states or CMS. Recent Medicaid access rules require states to compare their Medicaid and Medicare payment rates for specific services, including primary care, obstetrical and gynecological services, and outpatient behavioral health (42 CFR Parts 430, 438, and 457). Notably, however, children’s specialty services are not covered under the proposed rule, nor is there a requirement that the rule be adjusted for volume of care, which would provide a more comprehensive picture of differences in payment rates and service mix, as well as the relative attractiveness of different payers to providers.

Several proposals have been made in the past to benchmark Medicaid-to-Medicare rates (Allen, Golberstein, & Bailey, 2022), in part because of the administrative simplicity of such a proposal. Given that half of children are covered by commercial insurers, a comparison between Medicaid and commercial rates for child-relevant services, such as primary care, obstetric, and specialty care services, would be more relevant to children. Gaps in payment rates for Medicaid versus commercial insurance particularly affect children from racially marginalized and rural communities, as both have high rates of Medicaid insurance coverage. Existing studies have not explored differences between Medicaid fee-for-service and commercial clinician rates, a notable gap in the literature on the child health care system.

A recent review found commercial rates for physician services 118–179% higher than Medicare rates (Lopez et al., 2020; MACPAC, 2015a). The range of estimates likely reflects the differences in the services examined (e.g., procedures vs. evaluation and management), the market power of the insurance plan, the market power of the physician group, the timing of the data (2010–2017 across the studies reviewed), and other geographic differences. Few studies examined rural areas. In a related study pediatric subspecialists seeing many patients with Medicaid insurance reported highly discounted fees (Forrest et al., 2024). These studies, combined with the Medicaid-to-Medicare studies, imply strongly that Medicaid fee-for-service rates for children’s services are also lower than commercial rates.

Most relevant to children’s coverage are rates paid to clinicians by MCOs. Medicaid MCOs, some nonprofit and many for-profit,11 are contracted to state Medicaid agencies to receive capitated payments. They have considerable autonomy in setting provider rates, although many continue enhanced fee-for-service payments for providers, sometimes with end-of-year adjustments for certain performance indicators. Little work documents the adequacy of MCO payments. While states use population-level capitation payments for MCOs, the many providers receiving fee-for-service

___________________

11 Five for-profit entities (Centene, Elevance, CVS, United, Molina) control 50% of the MCO Medicaid market, and their profits are quite sizable.

payments from MCOs have limited incentives to improve care or appropriateness. States can impose provider payment schemes on MCOs (Hinton & Raphael, 2023; MACPAC, 2019, 2021a,c) and have demonstrated increasing interest in payment schemes that offer alternatives to fee-for-service payments to address misaligned incentives. Unfortunately, no data explore whether the alternative payment arrangements that MCOs have tested have increased Medicaid payments beyond average fee-for-service levels or improved quality.

The recent CMS access rules require states to submit an annual payment analysis that compares MCO payment rates for routine primary care, obstetrical and gynecological care, and outpatient mental health and substance use disorder services as a proportion of Medicare payment rates. While not required, similar analysis of Medicaid and commercial rates could also be performed. In 2021, Congress passed the Health Care PRICE Transparency Act (2021), making enormous amounts of hospital and insurer price data available to the public. The sheer quantity of data has been part of the challenge, since it is difficult to summarize and process, and, unfortunately, Medicaid MCOs are not included under the transparency mandate, limiting the value of this act for children’s care. The rule offers an alternative for obtaining MCO rates, assuming state reporting is reasonably complete and consistent.

Further complicating payment-rate comparisons is the fact that more than half of states make add-on Medicaid payments to providers outside of the regular payment formula (MACPAC, 2022). These “supplemental” and “directed” payments (discussed below) are captured as lump sums in public reporting and cannot be tied back to individual services in ways that facilitate a rate comparison with another payer (MACPAC, 2022). These additional payments are significant, with supplemental add-on payments accounting for $4 billion (or 33% of total fee-for-service payments to physicians) in fiscal year (FY) 2022 (MACPAC, 2023b), although the state variation here is wide, with Texas providing over half of the national total and California and Florida providing other large amounts. Most states provide relatively little physician and other provider supplemental funding. The total size of supplemental payments, relative to physician payments made by MCOs, is not reported. Also not available is the share of directed payments (totaling $38.5 billion) that are paid by MCOs and go to physicians (Government Accountability Office [GAO], 2023d).

Physician Participation

The central reason for policy concern around provider payment is to ensure that Medicaid programs can enlist enough providers such that their enrollees have access to covered services. By law, beneficiaries’ access should

be the same as for the general population in the same geographic area (Congressional Research Service, 2023a,b), regardless of whether coverage is by fee-for-service, through MCO fee-for-service to clinicians, or through an MCO alternative payment model. However, lower provider participation in Medicaid arises in large part from lower provider payment rates (Hing, Decker, & Jamoom, 2015; Zuckerman, Skopec, & Aarons, 2021), on top of disproportionate administrative burdens imposed by Medicaid programs.

Evidence that Medicaid rates are too low relative to commercial rates is bolstered by findings that providers are less willing to participate in Medicaid or accept new patients than in Medicare or commercial plans (Holgash & Heberlein, 2019; Tang et al., 2018). Clinicians may even misstate their willingness to see Medicaid patients in surveys because they may feel scrutinized (Rankin et al., 2022). “Secret shopper” studies, wherein researchers contact providers posing as patients, corroborate prevalent access problems for Medicaid patients. Across several children’s specialty services, Medicaid patients were less likely to receive appointments than patients with other forms of insurance; furthermore, even when the provider accepted Medicaid patients, their appointment delays were longer (Bisgaier & Rhodes, 2011; Chaudhry et al., 2013; Galbraith et al., 2005). Low payment leads to low revenue which also impacts providers’ ability to sustain innovation in pediatric health care delivery, particularly models focused on health equity. Challenges with MCO provider networks, and how they are monitored to ensure robust provider participation, are discussed at greater length below.

MCOs must meet federal and state provider networks’ adequacy provisions, but these networks also have potentially important gaps. A recent four-state study of Medicaid MCOs found skewed patient loads, with 50% of participating pediatric primary care providers seeing 150 or more Medicaid-enrolled clients per year (Ludomirsky et al., 2022). At the same time, 29% of listed pediatric Medicaid MCO providers saw just 10 or fewer clients, and roughly half of these saw zero clients. Listed providers who see zero patients are sometimes called Medicaid “ghost” providers, and while they are problematic in pediatric primary care, they are also common in adult primary care (15%), particularly in psychiatric care (35%). Low actual participation of providers in an MCO network may indicate that a network meets a state’s requirements on paper but does not provide adequate access in practice.

Low payment rates and low provider participation have generally led to recommendations to increase rates. Payment rate increases could enhance access in several ways: more providers could participate, providers could serve more Medicaid enrollees, or providers could extend visit length. However, the evidence is somewhat mixed on whether historical payment rate increases have been successful. A recent systematic review identifies seven studies of Medicaid fee changes and likelihood of provider participation

(Saulsberry, Seo, & Fung, 2019). Of these seven, five were conducted before 2001 and two examined the effects of the ACA fee increase for primary care physicians, which was relatively modest and temporary. One study found positive effects of fee increases on the probability of participation; one found a slightly negative effect; and three studies found no significant association, including two studies that examined the ACA fee bump. Among the seven studies, six examined Medicaid fee changes and the impact on patients seen per physician. Two studies found positive associations between fees and volumes, including one study of obstetrical care and one of physicians seeing children, and four studies found no significant effects. Unfortunately, the older studies predate large expansions in insurance coverage, and major increases in the consolidation and integration of physicians with hospitals, meaning the results may not apply today. Moreover, these studies examined Medicaid fee increases but did not account for payment increases of the magnitude associated with recent state supplemental payments, which could affect provider participation differently (as was the goal). Few studies address payment rate changes for subspecialty care (see National Academies, 2023e), although several hospital-based subspecialties, especially those with high hospital usage, receive supplemental payments, as discussed below.

Access to Clinicians

Another indicator that provider rates may be too low is consumer-reported access to care. A recent study by Haley and colleagues (2023) used 2016–2019 data from the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) and the 2016–2018 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) to examine access barriers for children enrolled in Medicaid/CHIP (before the COVID-19 pandemic). These researchers reported that 4.0% of Medicaid/CHIP-enrolled children ages 17 and under had at least one unmet need for medical, dental, vision, hearing, mental health, and/or other services (with dental care the highest at 2.0%); in the NHIS, 8.2% of Medicaid/CHIP-enrolled children ages 2–17 had some sort of need for care being unmet because of cost (most commonly dental care). In the NSCH the most common reasons for not receiving needed care were problems getting appointments (2.0%) and cost (1.9%), comparable to similar barriers reported in the NHIS. In the NHIS 6.6% of parents with children covered by Medicaid/CHIP reported delays in care from appointment waits, compared with 3.6% for commercially insured and 4.4% for uninsured children (Haley et al., 2023, Table 2), with 8.2% of Medicaid-covered children reported to have an unmet need due to cost, compared with 4.8% and 26.6% for commercially insured and uninsured children, respectively.

Haley and colleagues (2023) found that 23% of parents with children covered by Medicaid/CHIP experienced at least some frustration when

trying to get care for the children in the past 12 months, compared with 13% for commercially insured children, and 28% for uninsured children. At the same time, 22% of all children were reported to have no preventive medical visit in the previous 12 months (Haley et al., 2023), with stark variations by race and ethnicity (38.2% for American Indian/Alaska Native children; 32.0% for non-Hispanic Asian children; 21.9% for non-Hispanic Black children, 25.4% for Hispanic children, and 18.4% for non-Hispanic White children). These rates fall well below the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)/Bright Futures goal of all children receiving an annual preventive visit and the CMS goal of at least 80% of children receiving such visits (AAP, 2017). Arranging appointments can be frustrating and add to parental stress, and the presence of frustrations and stress may indicate that they lack alternatives. Haley and colleagues (2023) also found that children insured by Medicaid/CHIP had higher rates of access to preventive care than uninsured children but lower rates than commercially insured children.

Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Medicaid pioneered coverage of preventive services, particularly for comprehensive prenatal care and early and periodic screening, diagnosis, and treatment (Wiley, 2016).12 The statute titled Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT, 1968) provides a consistent, national standard for covered benefits, and states are required to use it as the base for children’s benefits. EPSDT’s statutory language refers to coverage of services necessary to “correct or ameliorate” physical or mental health conditions (42 USC § 1396d, 2024)—that is, if screening and diagnosis identify a problem needing services not included in the state’s benefit package, the state must still provide that service for children and youth up to age 21 years (42 USC § 1396d, 2024). Nonetheless, CMS and the states have administered and enforced the EPSDT benefit inconsistently and inequitably. Concerns about the regulatory base of EPSDT and its implementation in the states led to language in the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (2022) to require CMS to review state implementation of EPSDT. That review is under way, along with calls to modernize EPSDT regulations (Rosenbaum & Johnson, 2023).

The lack of a national definition for “medical necessity” allows states and MCOs flexibility, which has led to many denials of services, especially for children and youth with long-term health care needs and autism spectrum disorder (Baseman & Zettle, 2024; Grimm, 2023). EPSDT provides an important base for the services that children and youth need and has helped

___________________

12 For additional information, see https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/early-and-periodic-screening-diagnostic-and-treatment/index.html

many receive services; nonetheless, issues in its implementation have limited access for many. A recent GAO report reviewed MCO prior authorization decisions restricting care and called for additional systematic oversight from the states. Specifically, the GAO asked CMS to provide guidance for whether MCOs can set their own EPSDT medical necessity standards when the state lacks an EPSDT standard (GAO, 2024).

Children and Youth with Chronic Conditions and Special Health Care Needs

Medicaid plays an important role for children with disabilities and special health needs in several respects (Berry et al., 2021). It is the sole form of health insurance for approximately 36% of the total 13.9 million children estimated to have special health care needs, according to 2019 NSCH data (Williams & Musumeci, 2021). Low-income households have disproportionately higher rates of children with special health care needs, in part because parents are less likely to work or more likely to work less, in order to meet their child’s care needs, but also because of the long-term effects of poverty on health and birth weight leading to higher rates of chronic conditions and disability among low-income populations (Kuhlthau & Perrin, 2001; Thyen, Kuhlthau, & Perrin, 1999). Furthermore, the EPSDT benefit requires states to support a broad array of services that commercial insurance often does not cover, especially long-term care services, including institutional and noninstitutional services provided in the home or community, such as attendant care, assistive technology, and case management services (National Academies, 2018), encouraging some families to seek Medicaid coverage for their child with chronic conditions. Thus, while EPSDT applies to all children in Medicaid, it can be particularly important for children with special needs and children in foster care, many of whom also have special health care needs.

While the core Medicaid program supports some long-term services, others are covered through waivers available to states,13 again leading to wide variation among states (Manatt & Phillips, 2022; Williams & Musumeci, 2021). Main waivers that apply to home and community services include 1915c waivers and a specific “Katie Beckett” waiver that is meant to reduce hospitalizations for people under age 19 with disabilities.

Medicaid also supports populations of young children with disabilities through a wraparound program, in which children with commercial

___________________

13 An important waiver supports states’ coverage of noninstitutional services for children with disabilities who are under age 19 who without these services would be placed in an institution. This so-called “Katie Beckett” option (Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act waiver) is available in 49 states and Washington, DC. States can also apply for 1915c waivers, which support home- and community-based services for people with disabilities (not limited to younger populations), and some states include children and youth in their waiver population.

insurance that does not pay for home- and community-based services may receive Medicaid support for those services. As a result, 8% of children with special health care needs nationally have both commercial and wraparound Medicaid coverage, with Medicaid covering long-term services and supports. This proportion varies by state depending on state coverage rules, and children typically must meet a fairly high level of severity to receive such support (Alker et al., 2015; Gusmano & Thompson, 2018; MACPAC, 2018a). Because coverage of long-term services and supports for children is more extensive under Medicaid than with commercial insurance, families with children and youth with special health care needs are more likely to report reasonable out-of-pocket costs, greater benefit adequacy, and greater provider access if they have supplemental Medicaid coverage than if they have commercial coverage only. Nevertheless, families of children with special health care needs with Medicaid coverage more commonly report trouble covering basic needs, including not being able to afford enough to eat, compared with those who have commercial coverage (Williams & Musumeci, 2021).

Children’s Health Insurance Program

As noted earlier, CHIP was created in 1997 to expand coverage of children in low-income families by including eligibility to those below 200% of FPL but above the state Medicaid coverage level. This program permits states to collect premiums and copays from enrolled families for coverage. While Medicaid is an entitlement program with specified income eligibility and spending that reflects changes in enrollment, payment rates, and benefits, CHIP is not. CHIP funding is distributed as block grants to states, each receiving a fixed funding allotment that must be matched with state funds (Schneider, Klukoff, & Lehan, 2023). The matching requirement is lower than that for Medicaid (MACPAC, 2023a,b).14

CHIP is a significantly smaller program than Medicaid. In FY2020, children enrolled in CHIP totaled 9 million, while 35.2 million were enrolled in Medicaid (CMS, n.d.g). Nationally, 89% of CHIP-enrolled children are in families with incomes under 250% of the FPL (MACPAC, n.d.). Because CHIP programs do not have a federally imposed mandatory minimum or maximum income eligibility (other than the state’s Medicaid income base), states vary widely in their CHIP eligibility rules, ranging from 170% FPL in North Dakota to 400% FPL in New York. Under CHIP, states also have the option to cover pregnant women and unborn children (CMS, n.d.a; Social Security Administration [SSA], n.d.).

States choose how to implement CHIP funding. Some states use CHIP to expand Medicaid eligibility levels, while others cover children through

___________________

a separate state CHIP program; still others use a combination of the two approaches. Forty percent (40%) of CHIP-enrolled children are in a state program that is separate from Medicaid (MACPAC, 2020).

When CHIP is structured as a separate program, it can differ greatly from Medicaid, in that (1) states can require copays, (2) EPSDT is not mandated, and (3) states need not enroll eligible applicants if they have already used up the current year funding allotment. Stand-alone CHIP programs must offer “benchmark coverage” that is substantially equal, in actuarial terms, to the health benefits coverage in selected federal or state plans, and they must offer well-child care, dental coverage, behavioral health care, and vaccines (CMS, n.d.h). Many states use Bright Futures recommendations, developed jointly by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and AAP (AAP, 2017), as their guide to well-child coverage.

Of the 34 states that operate stand-alone CHIP programs, 27 also contract with MCOs (Schneider, Klukoff, & Lehan, 2023). CHIP MCO contracts are not subject to the Medicaid protections, such as minimum loss ratios, provider network adequacy provisions, transparency requirements, or quality monitoring, unless managed care plans enroll both CHIP and Medicaid enrollees under the same contract (Schneider, Klukoff, & Lehan, 2023).

Commercial Insurance

Most commercial insurance for children is employer based and is funded by premium contributions from employers and individuals. When firms offer health insurance coverage, 77% of workers accept that coverage (KFF, 2021; note that because these data are based on surveys of large and small employers, covered children cannot be examined separately from adults). The employee take-up rates vary by firm size and by workers’ income and age. Most employers (75%) who offer coverage offer just one plan choice. Twenty six percent (26%) of workers were in firms where the single plan was a high-deductible health plan. Larger firms are more likely than small firms to offer two or more health plan options. Overall, 46% of covered workers were enrolled in preferred provider organizations; followed by 28% in high-deductible health plans, which have lower premiums but higher cost-sharing than other plans; and 25% in health maintenance organizations or point-of-service plans, which limit provider choice through narrow provider networks. For young families with limited incomes, high-deductible health plans are attractive—premium costs are low and, in general, preventive services are excluded from cost determinations. Children with chronic conditions, however, are subject to higher out-of-pocket costs in a high-deductible health plan for the same set of services, and families may forgo needed treatment because of costs. For these families, high-deductible health plans may not be a good financial choice (Galbraith et al.,

2009, 2010, 2011; Kullgren et al., 2010; Kusma & Davis, 2021; Larson et al., 2021).

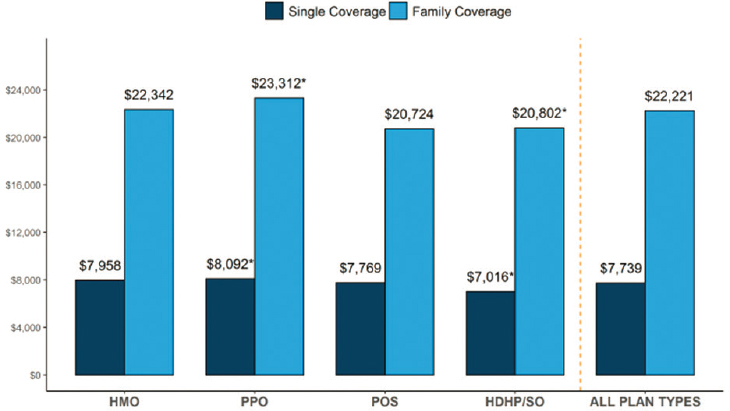

Based on employer surveys, the average annual premium in 2022 was $22,221 for family coverage, compared with $7,739 for single coverage (KFF, 2021). Employees contributed on average 28% of the premium for family coverage and 17% of the premium for single coverage. The premium amount depends on the type of coverage and is lower for plans with tighter provider networks, such as health maintenance organizations, and for plans with high deductibles (Figure 6-6). Premiums are also lower for private than for public firms, firms with more low-wage workers, and firms with many young workers. On average, differences in family premiums across firm size, worker age, low and high incomes, and firm ownership are under 15% (KFF, 2021a). However, the full range of family premiums is wide, with 15% of employers offering family coverage at $16,500 per year and 10% of employers offering family coverage at premiums of $29,000 per year or more (KFF, 2021).

The ACA eliminated out-of-pocket costs for selected preventive clinical services for employer- and exchange-based commercial insurance (Seiler et al., 2014). The specific services identified in the ACA must be offered without any form of cost-sharing (e.g., deductibles, coinsurance,

NOTES: *Estimate is statistically different from “all plan types” (p < .05); HDHP/SO = high-deductible health plan/savings option; HMO = health maintenance organization; POS = point of service; PPO = preferred provider organization.

SOURCE: Employer Health Benefits Survey (KFF, 2021).

copayments) and are sometimes referred to as “Section 2713 services” after the relevant paragraph in the Public Health Service Act (Coverage of Preventive Health Services, 2023). They include services with a grade of A or B from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; immunizations recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; services recommended for infants, children, and adolescents by Bright Futures; and services for women recommended in the Women’s Preventive Services Guidelines (CMS, 2024a; HRSA, 2024b).

Insurance Coverage for Parents

Adults caring for young children play a critical role in ensuring their children’s access to clinical care. They are responsible, for example, for ensuring their children have health insurance, identifying providers, navigating the health care system, making appointments, transporting children to care, paying for care, and obtaining needed prescription drugs or otherwise following up on a treatment plan. Whether a parent has health insurance is a key factor in children’s access to health care—including whether or not the child is insured (Hamersma, Kim, & Timpe, 2019; Hudson & Moriya, 2017), receives recommended preventive care (Venkataramani, Pollack, & Roberts, 2017), or goes without needed health care (DeVoe, Tillotson, & Wallace, 2009). Furthermore, the health and wellbeing of parents are key elements of support needed by children (see National Academies, 2019e, and earlier chapters in this report). Children raised by healthy parents have better health and outcomes.

Despite the importance of parental insurance coverage for children, an estimated 27.5 million individuals were uninsured in 2021, including 12.2% of adults under age 65 (Tolbert, Drake, & Damico, 2023). For low-income families who live in non-Medicaid expansion states, the median income for Medicaid eligibility is lower than the FPL (Tolbert, Drake, & Damico, 2023). And parents with incomes above the Medicaid eligibility threshold may lack access to premium tax credits for coverage through the Health Insurance Marketplace, which are designed to make that insurance more affordable (Drake et al., 2024). Ensuring access to affordable—and continuous—health insurance coverage for parents is a critical component of transforming the health care system for children. Increased health care coverage of adults increases health care coverage of children.

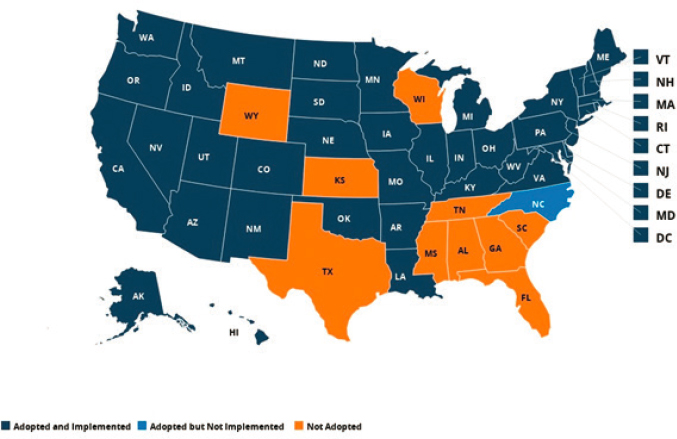

The 10 states that have yet to adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion (KFF, 2024) as of the writing of this report are predominately in the Southeast region of the country (see Figure 6-7). And in 2021, 44% of low-income Black adults and 37% of low-income Hispanic adults lived in the 12 states that had yet to expand Medicaid at that time (Baumgartner, Collins, & Radley, 2023). These inconsistent Medicaid policies for adults prior to, during, and after pregnancy impact children and child health even before conception and well after delivery.

SOURCE: KFF, 2024.

Direct Clinical Services Support

Community Health Centers

First launched in 1965 as “neighborhood health centers,” the goal of community health centers is to improve the health and lives of Americans regardless of their ability to pay for medical services. Funding for these centers is determined annually by Congress and is discretionary. Community health centers receive funding through insurance-enhanced payment and funds administered through HRSA to provide additional resources for capital expenditures, training, and other support. In addition, they receive funding from Title X for family planning services and revenue from public and commercial payers, as well as through a sliding scale for out-of-pocket payments established by a board of directors (National Academies, 2021b). Community health centers (which include federally qualified health centers [FQHCs], rural health clinics, school-based health clinics, migrant health centers, health centers for residents of public housing, and look-alikes15) have consistently received bipartisan support and expanded significantly since 2010, more than doubling their number of locations and removing

___________________

15 “Look-alikes” is a term used by HRSA. Health center program look-alikes are HRSA-designated health centers that provide comprehensive, culturally competent, high-quality primary health care services while meeting all health center program requirements, but they do not receive federal award funding (HRSA, 2023e).

barriers to care in many communities (Behr et al., 2022; HRSA, 2023e). However, not all communities have experienced increased access to community health centers equally; studies show that recent expansions were less likely to occur in rural areas or areas of high poverty (Chang, Bynum, & Lurie, 2019; Varshney, 2022).

As noted in Chapter 5, community health centers provide a comprehensive array of services to predominantly low-income populations who are uninsured or have Medicaid insurance. In 2021, community health centers served about 33% of individuals living in poverty and 20% of individuals living in rural areas (National Association of Community Health Centers [NACHC], 2022); FQHCs served more than 30 million patients, including about 12% of all children in the United States (NACHC, 2022).

Medicaid uses a prospective payment system for FQHCs rather than a fixed per-visit rate, as is common in fee-for-service systems. Rates are based on various indicators of center costs and prevailing health center rates in the area. Centers can achieve higher payment rates when they increase staff—for example, adding mental and behavioral health practitioners. The additional costs are then included in the negotiated rates for the prospective payment. States may use alternative payment models other than the prospective payment system for their contracts with FQHCs, but only if the resulting payment will be at least as high as it would be in the prospective payment system. Although usually not labeled as an alternative payment model, the prospective payment system has the advantage of supporting practice transformation with movement to teams for clinical care. The growth of managed care has also affected the payment arrangements for FQHCs, with many MCOs not following the prospective payment system rules of Medicaid.

Notably, FQHC governing boards are required to be composed of at least 51% of people who live in the communities served by the center and reflect the demographic characteristics of its population, making them uniquely community oriented. Community health centers must also complete a community needs assessment every 3 years, make and maintain relationships with other clinicians in their catchment to help coordinate care outside their center, and annually assess the geographic boundaries of their patient population. These centers must provide service to everyone regardless of their ability to pay.

Community health centers offer several important advantages and improved outcomes over traditional delivery systems for some populations with previously limited access (Heisler, 2017; Rieselbach et al., 2019). FQHCs offer transportation, translation, and case management services in addition to on-site care and referral to specialty care. These services help decrease disparities in access and outcome by race and ethnicity, and income and insurance status (Topmiller et al., 2023). HRSA-funded health

center members who utilize enabling services such as transportation or translation are more likely to get routine checkups, receive primary care, and report higher patient satisfaction than those who do not utilize such services. Overall, FQHC members have fewer hospitalizations than comparable populations, and FQHCs spend less on inpatient and specialty care while outperforming other delivery systems across measures of quality and outcomes, cost-effectiveness, and patient satisfaction (National Academies, 2021b). In caring for children, community health centers save 35% in emergency services, prescription drugs, and ambulatory care, compared with other types of providers (Bruen & Ku, 2017). Mothers receiving care at FQHCs, despite tending to be more at-risk individuals, are less likely to have an infant with a low birth weight compared with national averages across racial/ethnic groups (NACHC, 2020). For children, integrated behavioral and primary care at FQHCs improves detection and treatment of behavioral health conditions, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Sheldrick et al., 2022). Communities with a new FQHC have had an associated 5% drop in teen birth rates, with declines largest among Black teens and in counties with more than one FQHC (Farid, 2020).

The community health center model has been successful in meeting primary preventive care needs, but its growth (serving 24% more individuals from 2015 to 2021) has not kept pace with community needs (the number of individuals without a usual source of primary care has doubled since 2014; NACHC, 2023b). Some challenges in expanding the model relate to workforce shortages and financing. Although community health centers provide services nationally for roughly 16% of Medicaid recipients, they receive less than 2% of Medicaid payments (National Academies, 2021b). Moreover, their funding has not kept pace with medical care inflation (Brill, 2023).

Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics

The Community Mental Health Act (1963) established community mental health centers across the United States. However, initial efforts resulted in a fragmented system that did not meet community needs (National Academies, 2024a). The certified community behavioral health clinic (CCBHC) model—administered by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) in partnership with the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) and CMS—has evolved to provide coordinated, comprehensive behavioral health care based on community needs assessments. CCBHCs have been designed for mental health and substance use disorders to reach individuals across the lifespan with developmentally appropriate care. They are required to serve anyone who requests care, regardless of their ability to pay, place of

residence, or age. CCBHCs must meet standards for the range of services they provide, including those for screening, family-centered treatment, and peer- and family-support services, and they are required to get people into care quickly. Such features include 24/7 access to crisis services, mobile crisis response within 3 hours, urgent noncrisis need seen within a day, and routine care within 10 days (National Academies, 2024a). CCBHCs must provide clinicians with training on cultural competency; person-centered, family-centered, and recovery-oriented services; and trauma-informed care. Trainings must also be aligned with the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.). Furthermore, governing boards of CCHBCs are to have members representing individuals and families with lived experiences of mental health conditions and/or substance use disorders. A 2020 report to Congress noted that CCHBCs in participating states outperformed state Medicaid benchmarks in quality metrics for children and adolescents receiving an initial evaluation within 10 days, and for follow-up care after mental health hospitalization and after ADHD medication initiation and continuation (ASPE, 2020a).

An evaluation of the initial 2 years of the CCBHC demonstration found that, depending on the state, 8–27% of CCBHC clients were children or adolescents, 3–22% were African American, <1–8% were American Indian and Alaska Native, and 5–41% were Hispanic. Services provided to children and families were reported to include community wraparound services; dialectical behavioral therapy; peer support for families; and supported employment, housing, and education. Subgroup findings in this evaluation did not suggest that the CCBHC model systematically impacted service use differently for children and adolescents across the participating states (Brown et al., 2022).

CCBHCs can be supported through the Section 223 CCBHC Medicaid Demonstration of the Protecting Access to Medicare Act through SAMHSA-administered CCBHC expansion grants, or through independent state programs separate from the Section 223 CCBHC Medicaid Demonstration. In FY 2022, CCHBCs were appropriated $315 million through SAMHSA (2022c).

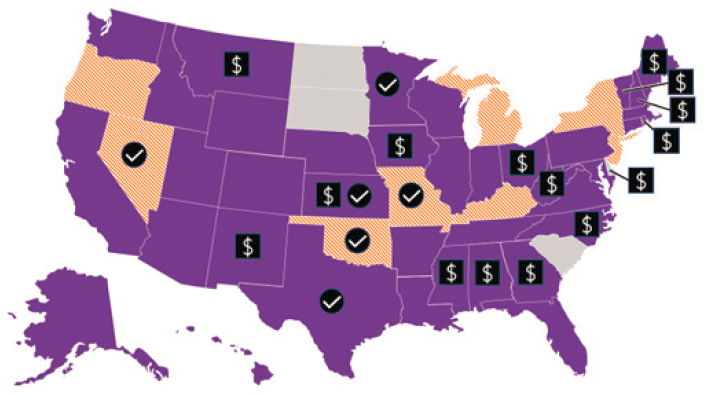

Currently, more than 500 CCBHCs are operating across the country, as either CCBHC expansion grantees, as clinics participating in their states’ Medicaid demonstration, or as a part of independent state CCBHC programs (see Figure 6-8). The CCBHC model has been designed to integrate a number of promising approaches discussed in this report. The effects of the model and expansion on child and family mental health have yet to be determined. Appropriate oversight will be necessary to ensure these centers make progress toward health equity and mental health goals and reach communities most in need.

NOTES:

Federal CCBHC Medicaid Demonstration (and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] Expansion grants)

Federal CCBHC Medicaid Demonstration (and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] Expansion grants) State contains at least one local SAMHSA expansion grantee in the state

State contains at least one local SAMHSA expansion grantee in the state Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services–approved payment method for CCBHCs via state plan amendment or 1115 waiver separate from Demonstration

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services–approved payment method for CCBHCs via state plan amendment or 1115 waiver separate from Demonstration Chosen to receive 1-year planning grant needed to join Medicaid Demonstration starting in March 2023

Chosen to receive 1-year planning grant needed to join Medicaid Demonstration starting in March 2023SOURCE: SAMHSA, 2023a.

School-Based Health Centers

School-based health centers are important settings where children can receive clinical care; moreover, centers located in low-income areas improve children’s health and education outcomes (Community Preventive Services Task Force [CPSTF], 2016a). For schools specifically, Medicaid allows simplified processes for calculating payment rates, for documenting services delivered, for determining Medicaid coverage (using estimated ratios of eligible children applied to services delivered, rather than person-specific eligibility determination), and for qualifying participating providers. In addition, through administrative matching funds, schools can support Medicaid outreach, enrollment, and care coordination (CMS, 2023c). In 2023, CMS released guidance on how Medicaid can fund services in schools (e.g., preventive, behavioral health, physical therapy). While Medicaid and commercial insurance can be billed, barriers exist including lack of effective billing infrastructure and at times primary care approval or preauthorization for certain school-based services.

Despite this flexibility, the fundamental structure of Medicaid as an insurance program does not support other effective school-based interventions, aside from school-based clinical services (Moore et al., 2024), such as schoolwide positive behavior supports, universal school-based programs to reduce violence or increase mental health (CPSTF, 2019b), enhanced school-based physical activity, school-based nutritional interventions, or multitiered services (Moore et al., 2024), or approaches that support school staff and teachers. See Chapter 8 for further discussion of school-based care services.

Indian Health Service

The Indian Health Service (IHS) provides direct health care services to eligible Native American individuals and Alaska Natives. About half of Native American individuals are eligible for this program, and in 2020, the IHS served 64% of the eligible population (National Academies, 2023d). IHS clinics include federal, tribal, and urban Indian health organizations that provide comprehensive care across the lifespan in rural areas; on reservations; and, increasingly, in urban population centers (IHS, 2020a). Some have been designated as FQHCs (IHS, 2005, 2020b).

IHS receives funding through congressional appropriations (mainly discretionary), which are supplemented by a small share of reimbursement collections from Medicaid, CHIP, and commercial insurance. Financing of IHS through annual discretionary allocation with specific spending limits is very different from Medicaid as an entitlement program with no annual spending caps. This impacts not only the year-to-year delivery of health care services but its long-term sustainability and the ability to update infrastructure and respond to public health crises (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic) or other unexpected events. IHS’s global budget structure also means that as the number of community members served increases, the per capita spending declines. It is also notable that Medicaid, with its relatively low reimbursement rates, comprised nearly 70% of third-party collections at IHS facilities during the federal FY2019 (MACPAC, 2021b). This creates a compounded and insidious inequity in how health care services for Native Americans are financed.

Currently, funding for IHS has been estimated to address only 48.6% of the health care needs of Native Americans (ASPE, 2022b). IHS funding for urban health has been only around 1% of the current allocation, even though 70% of Native Americans live in urban areas (ASPE, 2022a; National Council of Urban Indian Health [NCUIH], 2023). In 2018, the funding gap for direct care services for children and mothers eligible for IHS was estimated to be $7.8 billion (National Academies, 2023f). See the recent report by the National Academies titled Federal Policy to Advance

Racial, Ethnic, and Tribal Health Equity for a broader discussion of IHS structure and inadequate funding levels, its history and federal responsibility, and policy solutions for addressing health inequities for all ages of American Indian and Alaska Native people (National Academies, 2023e).

More than 60% of IHS appropriations are administered by tribes through self-determination contracts (25 USC § 5301; IHS, 2020b). The self-determination option allows tribes to leverage tribal leaders’ knowledge to assess needs and tailor services to their communities. The self-determination approach could be useful for providing child, family, and community-oriented care; however, as discussed above, the IHS to date is chronically underfunded (GAO, 2018; Heisler & McClanahan, 2020; Lofthouse, 2022; _National Academies, 2021e; Tribal Budget Formulation Workgroup, 2022; United States Congress, 2024).16

Hospital Supplemental Payments