Launching Lifelong Health by Improving Health Care for Children, Youth, and Families (2024)

Chapter: 1 Child Health and Health Care: Uniqueness, Societal Importance, and Vision for the Future

1

Child Health and Health Care:

Uniqueness, Societal Importance, and Vision for the Future

Invest in children’s health for lifelong, intergenerational, and economic benefits. The evidence is clear: early investments in children’s health, education, and development have benefits that compound throughout the child’s lifetime, for their future children, and society as a whole.

WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission, 20201

The United States is rebounding from the COVID-19 pandemic at a time of tremendous growth in science, medicine, innovation, and technology. Continued progress in these areas will require the efforts of creative and productive young people. Fortunately, the connection between health and wellbeing for children and the nation’s capabilities and capacity has never been clearer. Advances in genomics, new technology, and community-based health promotion offer incredible opportunities to improve child health and prevent adult chronic diseases by intervening early in the life course.

Robust science on the importance of early life experiences, relationship-based care, genetics, and developmental origins of health and disease demonstrates potential for enhancing society through a focus on prevention and health promotion in maternal, preconception, prenatal, child, adolescent, family, and community health and wellbeing. A substantial research base shows that efforts to promote positive childhood experiences in early life can reduce adult physical, mental, social, and relational health problems, again highlighting the need for preventive strategies (Bethell et al., 2019; Bethell,

___________________

1 Clark et al., 2020, p. 605.

Gombojav, & Whitaker, 2019; Braveman & Barclay, 2009; Bruner & Johnson, 2018; Gluckman et al., 2008; Halfon et al., 2018; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies], 2019b). The major causes of adult morbidity and mortality have their roots in childhood (Simmonds et al., 2016). For instance, obesity and diabetes often start in childhood, as do most cases of mental, emotional, behavioral, and substance use disorders (National Academies, 2019b,d). Major diseases of older populations, such as atherosclerosis and Parkinson’s disease, can also trace their roots to childhood. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with adult physical and mental health disorders, as well as lower education and productivity in adulthood (Felitti et al., 1998). Emphasizing early intervention and preventive care, such as health education, vaccinations, and regular screenings, can reduce the long-term need for more intensive services (AbdulRaheem, 2023; Fowler et al., 2020; Schor & Bergman, 2021).

Achievements in pediatric research in the past 40 years have driven solutions that have dramatically reduced childhood morbidity and mortality (Cheng et al., 2016). However, this progress is now under threat as evidenced by rising morbidity and mortality rates (Ely & Driscoll, 2022). Many see persistent inequities in child health, high rates of adverse childhood experiences (Camacho & Clark Henderson, 2022), and rising rates of mental and behavioral health conditions and obesity as contributing to this threat (see Chapters 2, 3, and 4). The pandemic made clear that the United States is at a crisis point regarding poor physical and mental health among the nation’s children and youth (Bauer, Chriqui, et al., 2021; Cheng, Moon, & Artman, 2020; National Academies, 2023b; Parolin & Wimer, 2020). High rates of childhood poverty; racism in health care and outcomes; and growing health problems and mortality among working-age adults have major implications for the nation’s economic productivity and prosperity. Rising rates of mortality and disability among youth and working-age Americans reflect outcomes of not providing the care that children and youth need. The U.S. military has raised concerns about the eligibility of young Americans for military service, with the largest increase in reasons for disqualification for mental health and overweight conditions (Department of Defense [DoD], 2020). The contrast between the opportunities presented by scientific and health knowledge and the clearly worsening health of young Americans shows the urgency of addressing child and adolescent health care transformation now.

Many organizations and partnerships, across both public and private sectors, are experimenting with bold place-based initiatives, new online services, artificial intelligence, and other innovations to help children and families in their communities. Innovative businesses are exploring new ways to care for their employees and families; others are investing in public–private partnerships to improve child and community health (Johns & Rosenthal, 2022). The foundation of many of these efforts is the moral imperative for

addressing child health. Investing in healthy children is the right thing to do because children are the least able to care for themselves and are the most dependent members of society. Yet, as detailed below and understood by some business leaders (Johns & Rosenthal, 2022), this investment also helps parents and their role in the workforce immediately, and the future workforce and healthier communities in the longer term.

Pediatric health care has evolved with many innovations to address salient present-day challenges to child and adolescent health. Pediatric health care has long championed prevention and health promotion from the earliest work of the Children’s Bureau and the development of the medical home in the 1960s. Over the ensuing decades, much progress has occurred, broadening the content of pediatric primary care and including programs that support healthy development (e.g., HealthySteps, Reach Out and Read), integrate mental and behavioral health with primary care, and strengthen coordination and collaboration with community resources (e.g., community health workers, Help Me Grow; see Chapters 3 and 5). Many of these advances have had extensive evaluation and testing, although bringing them to scale and building universal comprehensive advanced primary care have not occurred. Main barriers include lack of financial incentives and support for the complex process of transformation and lack of a trained workforce, especially among community health workers and co-located mental health providers. Successful programs have relied in large part on philanthropy and grants rather than the main financing structure from public and commercial health insurance.

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

With the support of a broad coalition of sponsors (see Box 1-1), the National Academies assembled the Committee on Improving the Health and Wellbeing of Children and Youth through Health Care System Transformation to examine ways to improve policies, practices, and norms, and to enable child and adolescent health care systems to embrace the scientific evidence for health promotion, disease prevention, and early intervention. The committee was also tasked with investigating how financing approaches can be updated to incentivize these changes. Committee members included physicians, nurses, hospital system leaders, Medicaid experts, youth and family advocates, community health center providers, economists and health care financing experts, and experts in mental health and school-based health care. Appendix A presents brief biographies of the committee members, fellow, and staff. The committee was charged with addressing a series of questions that would set forth a vision for a health care system that would improve the health and wellbeing of children, youth, and families (see Box 1-2).

BOX 1-1

Study Sponsors

- Academic Pediatric Association

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- American Academy of Pediatrics

- American Board of Pediatrics

- Children’s Hospital Association

- Health Resources and Services Administration

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

- Silicon Valley Community Foundation/Pediatrics Supporting Parents

- The David & Lucile Packard Foundation

The committee’s work and approach to addressing the questions in its charge focused on mechanisms at the system level, with attention to levers, policies, and engagements that will support necessary changes to establish equitable health care. Chapters 1–5 provide background for the reader to understand the importance of child health for society, recent advances in medicine and health care, the current state of child health and health disparities, and the structure and innovations of the existing health care system. Throughout this material, the committee examines both opportunities and challenges for health care. Chapters 6–9 discuss the key levers identified by the committee for transformation within the child and adolescent health care system: financing through insurance for health care services, public health investment, leveraging school settings, and measuring population health outcomes. Chapter 10 sets out important goals and recommendations for improving the health and wellbeing of children and youth.

The committee’s focus is on the health care sector, defined broadly to include clinical care, public health investments in child and family health, and school efforts in health care. The committee recognized the many other important influences on child and family health, especially poverty and income support, housing, labor markets and employment, community wellbeing, family leave and child care support, juvenile justice reform, and educational reform and financing, but focused its efforts on the health care system. Other recent National Academies consensus studies provide strong evidence of the impact of these nonhealth sector influences on children and families (see Appendix B). This report emphasizes how the health care sector—its structure, components, incentives, governance, and financing—can transform to improve the health and wellbeing of the nation’s children and youth.

Throughout the report, the committee uses the term “child health” broadly to include preconception, maternal, prenatal, child, adolescent, family, and community health and wellbeing. The report takes a multigenerational and

BOX 1-2

Committee’s Charge

The National Academies will appoint an ad hoc panel of experts to examine what innovations can be made to the child and adolescent health care system to improve the health and wellbeing of children, youth, and families. The study will address the following questions:

- What are key levers of change to guide innovation and transformation within the child and adolescent health care system to facilitate health promotion, resiliency, disease prevention, and appropriate treatments and interventions for all children, youth and families?

- What are promising policies and practices that incorporate the lived experiences of underserved children, adolescents, parents, and caregivers, and build the needed trust, partnerships, and long-term relationships to promote family-centered engagement, promote protective factors, and help address systemic inequities and disparities in access to and use of high-quality child and adolescent health care?

- What are the gaps and barriers in current payment models, for both public and commercial insurance, and what are potential solutions to overcome them?

- How can innovation in workforce development within the health care system facilitate team-based care and produce more community-based, culturally and linguistically competent workers? What strategies can stabilize the workforce to enable the formation of long-term relationships within the community?

- What are promising levers available within the health care system to enhance interaction and integration of the child and adolescent health care system with major programs that support education, child and youth development, public health, child welfare, juvenile justice, and other key services that heavily influence the health and wellbeing of children and adolescents?

- What are promising mechanisms and policies to enhance collaboration among and integration of data systems for health care, mental health, public health, welfare, education, and other agencies at the community, state, and federal levels for improved individual and population health?

life course perspective because research has shown that all health and developmental stages build on each other and are inextricably linked. Substantial evidence demonstrates that health early in the life course sets the foundation for health through childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, and tomorrow’s workforce and parents (see Chapter 2).

The committee also recognized deep concerns around systemic inequities and disparities in access to and use of high-quality child and adolescent health care, and it sought solutions to address these concerns. Such inequities are often viewed through the lens of race and ethnicity. However, health disparities exist across a broad range of dimensions, including

socioeconomic status, age, geography, language, gender, disability status, citizenship status, and sexual identity and orientation. Such dimensions are not mutually exclusive and often intersect in important ways (Ndugga & Artiga, 2023). Furthermore, there is much heterogeneity within population groups. In this report, the committee uses the term “historically marginalized” to reference groups and communities that have been and are served poorly by the health care system, have faced and continue to face systemic oppression and denial of access to high-quality care, and experience disproportionate impacts from discrimination (National Academies, 2017a, 2020c). Where possible, the text refers to specific populations (e.g., low-income families; immigrants; Black, Hispanic, Indigenous communities) to be intentional about the particular barriers and lived experiences of these groups.

In undertaking its study, the committee recognized that families and communities have varied goals for healthy living and expectations of the health care system. The committee took steps to ensure that a range of perspectives was considered, including listening to community voices through multiple formats, including invited speakers at committee meetings (see Appendix C), online collection of public comments, and review of community murals and children’s drawings that illustrate concerns and visions for healthy communities (see, e.g., Figure 1-1).

SOURCE: Wang Schuchi, age 7, China; © Peace Child International, used with permission.

STUDY APPROACH

The committee held five two-day hybrid meetings and a set of virtual calls between February 2023 and February 2024 to gather information, deliberate on findings, and develop this report. At its first meeting, representatives from the nine sponsors of the study participated and provided guidance and expectations for the committee’s work. At four of the meetings, outside speakers were invited to public sessions to inform the committee’s deliberations. The speakers provided valuable perspectives on a broad range of topics, including the rise of diversity among U.S. populations of children and youth; ways to engage families and communities in health care; chronic health needs of youth and young adults; current gaps and barriers in payment models; innovative collaborative care models in Alaska, Texas, Ohio, and Michigan; partnerships with the business sector; scientific advancements for health care delivery; the purpose of transformation; and levers of change. Agendas from the committee’s public sessions can be found in Appendix C.

Through the study’s website, the committee solicited input from patients, families, health care providers, researchers, and the general public to raise awareness of broader concerns and ideas. While public comments addressed several topics, mental and behavioral health care was mentioned consistently. Commenters called attention to the need for changes in the health care system and emphasized prevention initiatives, early health promotion, and greater support and inclusion of community and social services to address the social determinants of health. Comments also highlighted multiple insurance barriers and challenges with developing, implementing, and validating performance measures.

The committee also reviewed the existing literature, including peer-reviewed scientific literature and publications by private and public organizations and governmental agencies. Topics relevant to this report are broad: healthy development at all ages and across the generations, health and wellbeing measures, societal and community conditions and social determinants of health, health care system characteristics and innovations, public and private financing mechanisms, federal programs and resources, school-based services, family and community needs, and scientific and technological advances related to the delivery of health care. The committee commissioned two papers to review information and findings on international policies and programs for preventive care and mental health care (Niksch & Papanicolas, 2023; Stabile, 2023). The interdisciplinary nature of the committee’s membership meant that various scientific traditions of understanding, methodology, and ways of knowing were present.

Building on the growing field of community-based participatory research, the committee also carefully considered the important evidence provided by patient, family, and community voices, reflecting its belief that transformation

of health care must be done in partnership. The perspectives of children, youth, and families engaged in the health care system have often been omitted from the process of research question development, study execution, and data analysis and dissemination. Children, youth, and families engaged in the health care system are closest to the issue at hand, and consulting and learning from these communities improves the scientific process and has the potential to create more impactful solutions. Centering research on those with lived experience adds crucial insight into what works and what does not, helps researchers better understand the full context of an issue and the full implications of research findings, creates opportunities for meaningful work for those with direct experience, and may build trust in communities where generations of neglect and harmful actions have built a foundation of earned distrust (Israel et al., 1998; National Academies, 2021c, 2022b, 2023h).

As will be discussed in depth in later chapters, the committee strongly believes that the experiential knowledge and expertise of children, youth, families, and communities engaged in the health care system need to inform the design and implementation of health care system transformation. With this in mind, the committee modeled an “inclusive research frame” in its work and was intentional about involving people who are experts—by way of training, education, and/or lived experience—on the topic under study.

TRANSFORMING CHILD AND ADOLESCENT HEALTH CARE

For decades, numerous calls to improve the child and adolescent health care system have highlighted improving health equity, accountability, cost-effectiveness and quality, and patient and family engagement. The evidence cited by most of these calls supports emphases on preventive care, including community-based prevention and health promotion; direct attention to inequities and population health; new financing and metrics to assess progress; and new models of care.

This report is by no means the first assessment of opportunities for transformative pediatric care; it builds on an ever-expanding body of research targeting children, families, and communities (Perrin, Duncan, et al., 2020). The importance of person-centered, community-oriented care has been recognized for decades, coupled with calls for new conceptualizations and models of care that reform public health approaches and primary care delivery (Bruner & Hayes, 2023; National Academies, 2021b; Perrin, Duncan, et al., 2020; Shortell et al., 2023; Whole Child Health Alliance, 2023), as well as large-scale efforts to transform health care delivery and payment systems. Despite these calls for action, populations face unequal access to care, driven by economic, mental health, and social health disparities, which disproportionately impact historically marginalized communities. The United States has not taken full advantage of substantial evidence supporting pediatric health care reforms, leaving many of the nation’s children, parents,

and communities disadvantaged across the life course. The committee’s work and this report leverage findings and conclusions from a number of prior National Academies reports relevant to this topic (see Appendix B). This body of work represents decades of accumulating knowledge on the importance of health and wellbeing across the life course, beginning with preconception conditions and including supports and positive environments at each stage of life to ensure a healthy and productive society.

In discussing how to guide and implement effective change in the health care system, the committee considered successes and limitations of these prior efforts to innovate health care, as well as key evidence, all of which emphasized the potential and value of earlier identification of disease and prevention, correcting health inequities, and the importance of implementing changes to the child and adolescent health care system in the next 10 years. This review of previous efforts also clarified the need for a sustained focus rather than short-term changes or policies.

Prevention and Health Promotion

While prevention and health promotion have long been a cornerstone of child and adolescent health care, the current national situation, given the evidence of poor health outcomes downstream, calls for even greater investment in these efforts. Prevention can save money as well as lives and health. For example, vaccines save both costs in medicine and millions of lives (National Academies, 2024c). Routine immunization of children born from 1994 to 2023 has been projected to prevent nearly 1.6 million early deaths, 508 million illnesses, and 32 million hospitalizations, and to save nearly $2.9 trillion in total societal costs—more than $5,000 for each American (Andre et al., 2008; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2024j,p; Stack et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2014). For example, the incremental lifetime medical cost of an obese 10-year-old child relative to a child who maintains a healthy weight through adulthood is $19,000. Multiplying this by the number of obese 10-year-olds yields a total direct medical cost of obesity of $14 billion for this age alone (Finkelstein, Graham, & Malhotra, 2014). Oral health care for children is another crucial component of preventive care. Regular preventive dental visits improve oral health and reduce later costs, particularly for children at high risk of dental disease (Downing et al., 2022; National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development, 2021; Rowan-Legg, 2013). Fluoride treatments, increasingly given in primary care, significantly decrease dental caries in children (Downing et al., 2022; National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development, 2021; Rowan-Legg, 2013). Economic studies show that adverse childhood experiences are associated with trillions of dollars of costs from adult physical, mental, and behavioral health problems and loss in quality of life. Preventing and mitigating the impact of adverse childhood experiences can likely decrease these long-term costs

(CDC, 2019b,d; Peterson et al., 2023). Regarding mental health, universal and targeted school-based cognitive behavioral therapy programs reduce depression and anxiety symptoms in children (Werner-Seidler et al., 2021). Exciting scientific advancements in developmental origins of health and disease, genomics, and predictive artificial intelligence all emphasize the potential of early intervention, prevention, and health promotion.

Addressing Inequities

However, many children lack access to adequate preventive care. Disparities in access to and quality of care for the nation’s poorest children continue in the current system. The United States is one of a few countries in the world that does not entitle all young children and pregnant persons to health care and has some of the lowest rates of access to preventive care and routine services among resource-rich countries. Notably, many U.S. cities and states report high rates of inequities in infant mortality, preventable disease outbreaks, and higher costs of care for many specialty conditions. As the following paragraphs show, the main health financing systems cover racial and ethnic groups differentially, with historically marginalized populations having higher public insurance coverage and lower commercial coverage.

Financing

Current mechanisms of financing health care are struggling to keep up with changing demographics; environmental influences on health; new clinical strategies; and technological advances, such as increased use of telehealth. Models of health care payment—usually relying on traditional fee-for-service structures or value-based arrangements focused on lowering costs for high-cost adult patients—do not provide child health clinicians the flexibility or incentives to work with families and partner with communities to address their health and developmental needs (Counts, Mistry, & Wong, 2021; Counts, Roiland, &Halfon, 2021). Instead, current models incentivize billable encounters and procedures or lowering costs, rather than measures to address the health of communities. Payment models limit the ability of clinicians to work across sectors to address the social and family challenges that underlie many child health concerns (Johnson, Willis, & Doyle, 2020).

The main public insurance programs for children and youth (Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program [CHIP]) cover almost half of all U.S. children and youth and have benefited young populations by assuring eligibility with little or no cost-sharing and a broad set of benefits, including the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment statute that requires an exceptionally strong service base for the health care needs of children. A large majority of covered children would have had no insurance

without Medicaid and CHIP. Furthermore, the high rate of managed care for children in these programs (~85%) offers real opportunities to test new payment models and incentives. Nonetheless, Medicaid and CHIP also reinforce structural racism in health care, in part because they disproportionately insure children of color and have low payment rates (Perrin, Kenney, & Rosenbaum, 2020).

Despite many well-documented advances in pediatric care, including primary and specialty care, payment for care has kept much care delivery based in a model of acute pediatric visits, originally focused on short-term illness care by office-based clinicians with less attention to chronic conditions (which were less common 50 years ago). Pediatric care has expanded its commitment to well-child care, incorporating immunizations and screening for various health conditions and providing guidance to families about upcoming growth and development milestones. However, child health settings often experience challenges in providing coordinated, longitudinal care for chronic illnesses and comprehensive care that addresses social determinants of health and relational health, in part because of limited financial incentives. Children, families, and communities often report that the child health care system does not meet their needs (see Chapter 3).

Innovations in Health Care

Many innovations have effectively improved preventive care, health promotion, long-term care coordination, specialty care, and health equity. Federal agencies and states are investing in efforts to integrate early child health care systems to drive comprehensive, high-quality well care (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2021). Schools and community settings in some locales offer prevention services in partnership with large health care systems (Boudreaux, Chu, & Lipton, 2023). And some health care systems serving children and youth have begun to use innovative financing models. For example, through accountable care organizations, participating systems receive global payments for a population (Center for Evidence-Based Policy, 2022), although few focus on younger populations (Perrin et al., 2017). Several state Medicaid programs now support team-based care models, integrating mental and behavioral health and including community health workers as part of the care team (Haldar & Hinton, 2023). Some communities have integrated health care practices with a variety of community resources, including health and social services, home visiting and family supports, educational resources, and housing programs (Garner & Yogman, 2021a; National Academies, 2019d). Additionally, health care organizations are implementing new models of community investment, which can have upstream impacts on child health and cascading benefits for both the investor and the community (Hacke & Deane, 2017).

These many innovations have documented improvements in health status, equity, care coordination, and child behavior and development. Promising payment reforms have lessened the incentives to produce visits and procedures, and have increased support for long-term outcomes and population health. The task now is to transform the larger health care system in ways that decrease chronic conditions, decrease disparities, shift payment and spending, and enhance wellbeing.

UNIQUENESS OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES FOR CHILDREN: THE 5 Ds

The health care system for children is often modeled after the adult health care system, yet several fundamental characteristics of children and youth differ from those of adults. The committee presents here current and enduring differences between pediatric and adult care (the 5 Ds) and the need for attention to these differences in all policies and programs with special approaches to child health. Consideration of and investment that recognizes these unique developmental needs result in population health over the life course. The 5 Ds are developmental change, disease/differential epidemiology, dependence, demographics, and dollars (Cheng & Mistry, 2019, 2023; Forrest, Simpson, & Clancy, 1997; Stille et al., 2010).

Developmental Change

While health care for adults focuses on health maintenance, remediation, and rehabilitation, children’s health care attends to unique developmental needs and stages of children as they develop competencies and basic skills for their own self-care. Child and adolescent development is characterized by continuous new skills, growth, and transition, setting a trajectory for health across the life course (Halfon & Hochstein, 2002; see Chapter 2). Health care must focus on prevention, health promotion, and enhancing developmental progress to ensure that children are healthy and learning. Over the life course, a child meets experiences that can support or hinder growth and development, and the effects of these experiences accumulate through their lifetime. Health conditions manifest differently at different stages of life, respond differently to prevention and treatment, and lead to different consequences as a result of development (Halfon & Hochstein, 2002). Health and illness for an 18-month-old are very different from that of an 18-year-old. Useful health metrics address these differences across an individual’s entire life course, including the preconception and prenatal health of mothers and their children, and consider a broader range of indicators over time, such as wellbeing, life chances, opportunity, risk and resilience, health potential,

educational outcomes, and quality of life, in addition to the traditional focus on disease status and health care provision (Horn et al., 2009; National Research Council [NRC] & Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2004).

Disease/Differential Epidemiology

Child health conditions have differential epidemiology compared with adults and require different solutions. A growing proportion of children have complex physical, mental, and social conditions, although this proportion is still far lower than that of older populations. Some of the growth in chronic conditions among children and youth reflects advances in medical and surgical care, although a greater proportion of the growth is associated with adversity and environmental risks in early childhood, especially asthma, obesity, developmental problems, oral health problems, and mental and behavioral conditions (CDC, 2021e,f, 2024b,f,g). The number of children with mental and behavioral health conditions is epidemic, and this growth in large part reflects earlier life experiences and community and environmental exposures. Many other childhood conditions (e.g., cancers, heart disease, spina bifida, arthritis, cystic fibrosis), occur in relatively small to very small numbers (Bai et al., 2017; Perrin, Bloom, & Gortmaker, 2007).

The preconception and prenatal health of parents influences child health. Chronic child health problems such as obesity, cognitive disability, and neurodevelopmental disorders are often related to preventable maternal conditions (Capra et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2023). Maternal and child exposures to psychosocial (e.g., maternal stress, adverse childhood experiences) and environmental threats (e.g., toxins) may manifest differently and accumulate over time in utero and during childhood. (See further discussion of the influences on child health and trajectory into adulthood in Chapter 2.)

Dependence

The wellbeing and support of caretakers and families help determine the health of children. Family capacities include physical and mental health and wellbeing, financial resources, time, and human capital (education and employment opportunities; Mistry et al., 2012; National Academies, 2019d). Families in turn depend on resources in their neighborhoods and communities (Minh et al., 2017). Optimal functioning of the family unit requires assessment and investment in family health, income supports and services, and community collaboration (National Academies, 2019d). Children rely directly on adults in child care, schools, and social services, in ways that differ markedly from family relationships among adults. This dependence

requires that health care systems support healthy families and communities and partner across sectors of health, schools, child care, social services, juvenile justice, and child welfare.

Demographics

American children are more likely to live in poverty than are adults and older individuals. The highest rate of poverty of any age group is children under age 5 (Children’s Defense Fund, 2023). In 2024, households with incomes below the federal poverty level (FPL) have annual incomes under $30,000 for a family of four, for example, or $14,580 for an individual. About 15% of Americans reside in households with incomes at or below 125% of the FPL, encompassing approximately 50 million low-income individuals, including around 15.2 million children under age 18 (Creamer et al., 2022). As of 2022, nearly two out of every five children lived in low-income families, defined as being at or below 200% of the FPL (Kids Count Data Center, 2023a). Children of color experience disproportionately high poverty rates—27.1% of Black children and 29.1% of American Indian/Alaska Native children lived in poverty in 2021, compared with just 8.8% of White children (Children’s Defense Fund, 2023). Additionally, young children under age 5 face the highest poverty rates, at 16.3%. With the pandemic child tax credit, child poverty dropped to 5.2% in 2021, but since the ending of pandemic emergency supports in 2022, poverty rates and associated racial/ethnic disparities have increased to over 12% (Shrider & Creamer, 2023). Historically, economic downturns have affected children the most, with longer-lasting consequences in adulthood than those who were already adults during the downturn (Golberstein, Gonzales, & Meara, 2019; Kalil, 2013).

The number of children experiencing social adversities—including poverty, death, and incarceration or illness of a parent—is unacceptably high. Exposures to poverty, hunger, homelessness, and environmental threats (e.g., toxins) for children are higher than among adults, and require different and intentional primary and secondary prevention strategies. Epidemiologic research has demonstrated a strong dose–response relationship between adverse childhood experiences and child health, adult physical and mental health, and workforce outcomes (Ely & Driscoll, 2022; Felitti et al., 1998).

Children and youth are more diverse than the rest of the U.S. population (see illustration in Figure 1-2). In 2020, fewer than half of children were non-Hispanic White, and births of non-White babies have surpassed births of White babies since 2011 (Census Bureau, 2023a). This diversity is associated with disparities in child health and education by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.

SOURCE: Anonymous child artist; © Peace Child International, used with permission.

Dollars

For their health care, children depend on (1) family income, wealth, and supports; (2) educational attainment; (3) public health and education spending; and (4) commercial insurance, Medicaid, and CHIP. Half of all American children ages 0–18 are insured by public sources (e.g., Medicaid, CHIP, other), and 5% are uninsured (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service [CMS], 2023f,g). Black, Latino, and American Indian/Alaska Native children are disproportionately uninsured (Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2023a) or from low-income households (Keisler-Starkey & Bunch, 2022). A quarter of women who delivered a child were uninsured in the month prior to pregnancy, over half of whom had less than 12 years of education (Wherry, 2018). No other age group—other than older populations with Medicare—depend so much on public investment for their health care. However, Medicaid low payment rates (about two-thirds of rates paid by Medicare for the same services) threaten families’ access to primary and subspecialty care, providing insufficient margins for many clinicians to participate in Medicaid (Galbraith et al., 2023; Perrin et al., 2020).

In 2020, children ages 0–18 accounted for about 10% of total health spending but represented 23% of the population (CMS, 2023f). Directing the majority of health care dollars to expensive hospital-based adult care

fails to consider the short- and long-term value of child health. Return on investment (ROI) in child health occurs not only in the health care sector, but also in education, social services, and juvenile justice (Flanagan, Tigue, & Perrin, 2020). However, most ROI for child health programs accrues over a longer period of time as children develop. The long-term trajectory for ROI calls for different incentives for payers, hospitals, and legislators than short-term cost savings.

SOCIETAL GAINS FROM INVESTING IN CHILD HEALTH

The U.S. health care system today consumes about 20% of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP)—far more than any other country; yet the nation sustains generally poor health status and outcomes, including for children and youth (Keehan et al., 2023; National Academies, 2021b). Growing costs have engendered many calls for change and financing reforms to contain costs (Perrin, Cheng et al., 2023; Perrin, Flanagan et al., 2023), although the low expenditures for populations under age 21 offer few opportunities for savings in the short run. Adult health expenditures represent an enormous share of health care costs, yet poor health outcomes remain (McGough et al., 2024).

Invest in Child Health for Savings and Benefits to the Nation

Importantly, growing evidence spotlights opportunities to address the early conditions that cause individuals to become high-cost and high-need patients in the first place (IOM, 2010; McGough et al., 2024; National Academies, 2019d). The path to becoming a high-risk, high-need, high-cost adult patient starts as early as before conception, in utero, and infancy; conditions and experiences during childhood greatly affect individual health trajectories across the entire life course (Halfon & Hotchstein, 2002; Perrin, Cheng, et al., 2023; Perrin, Flanagan et al., 2023). These opportunities can have a major impact on bending the cost curve and improving health outcomes, but doing so demands that health care efforts focus on upstream factors and prevention, payment reform, and eliminating racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities. Demographic shifts in the U.S. population have led to a growing population of individuals over age 65, along with a declining birth rate and relative scarcity of working-age adults able to support and take care of older populations (see details below). Ensuring the best growth and development of each child has become vitally important for the future.

There are numerous urgent reasons to invest in children and families. Strong evidence suggests that Medicaid for children, investments to reduce child poverty, and investments in healthy development have significant

financial payoffs (Ash et al., 2023; Hendren & Sprung-Keyser, 2020; Lou et al., 2023; Maag et al., 2023). Nobel laureate James Heckman has demonstrated that early investment in the wellbeing and skill formation of disadvantaged children pays off economically and is just and equitable (Heckman & Masterov, 2007). His research and economic modeling show that parental influences are primary in developing children’s cognitive, social, emotional, and learning skills, and that quality of early childhood development heavily influences health, economic, and social outcomes for individuals and society at large. Heckman and Masterov (2007) concluded that there are great economic gains to be had by investing in families and early childhood development. Other studies show that eliminating racial/ethnic disparities dramatically reduces medical care costs and indirect costs of excess morbidity and mortality (LaVeist, Gaskin, & Richard, 2011; Thornton et al., 2016). Investments in child health also have positive effects on parental health and parental productivity, as well as the child’s future health as they become an adult, with societal return on investment bridging multiple sectors (e.g., health, education, social services; Cheng & Solomon, 2014). Hendren and Sprung-Keyser (2020) reviewed 133 social policies to determine which improved social wellbeing the most and yielded the largest marginal value of public funds. They found that direct investments in the health and education of low-income children offered the highest returns.

Public Health Investment Benefits Child Health

Short-term, public spending benefits children and families directly. These benefits include access to health care and education; reduced poverty and food insecurity (especially for infants and toddlers who have particularly high poverty rates; Lou et al., 2023); better nutrition; lower family stress; healthier relationships; and conditions that allow children to be healthy, ready to learn, and on an optimal trajectory to adulthood. Long term, the benefits accrue to children and families and to society broadly. These payoffs include greater adult productivity resulting from having a more educated, healthier, and more skilled labor force—and the associated tax revenues (Ash et al., 2023; Maag et al., 2023; McLaughlin & Rank, 2018). Public investments in children also save societal and governmental expenditures on criminal justice, health care for chronic diseases (both public and private spending, including Medicare), and social services and public programs for adults (Maag et al., 2023).

Societal return on any single government investment is difficult to measure because children are affected by a constellation of programs and influences; however, research suggests that some programs have returns reaching $10 or more per dollar invested (Garfinkel et al., 2022; Hendren & Sprung-Keyser, 2020). Payoffs are particularly high from investments in

Medicaid; a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) study found that “long term fiscal effects of Medicaid spending on children could offset half or more of the program’s initial outlays” (Ash et al., 2023, para. 1). Such investments reduce child poverty (McLaughlin & Rank, 2018) and promote healthy development and skills (Heckman & Masterov, 2007).

Investment in Child Health Benefits Children Now

The cost of not investing in child wellbeing must also be considered. Economists estimate that child poverty costs the United States between $800 billion and $1.1 trillion annually, 4.0–5.4% of the GDP, with the largest cost from reduced productivity later in life (Maag et al., 2023; National Academies, 2019a). Children growing up in poverty are more likely to have poorer health, earn less, pay less in taxes, and require more public supports in adulthood.

Historically, investment in child health has occurred during times of technologic change and health crisis. With emergence of new technology, rising child morbidity and mortality, and declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health, the time is ripe for change (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2021a). In U.S. history, categorical arguments to elevate health equity for vulnerable groups have included moral, performance or outcomes, economic or workforce, and national security arguments (Dawes, 2020, p. 72).

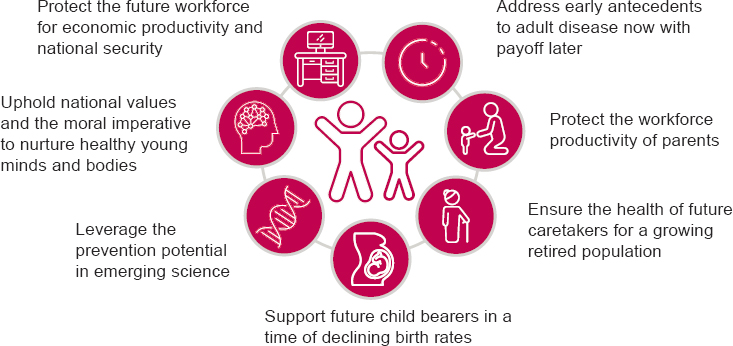

Realizing opportunities for improved population health and lower societal costs over time requires a sustained investment and a long-term commitment. This report addresses ways to achieve better health outcomes and health equity for children and provides a roadmap for doing so. The benefits of improving child health are both immediate and lasting. American identity and national values lie in providing opportunity for all and nurturing the young. The societal gains that result from investing in the health and wellbeing of children and youth are summarized below and in Figure 1-3 and Table 1-1. These echo the influential National Academies report From Neurons to Neighborhoods, which called for “a new national dialogue focused on rethinking the meaning of both shared responsibility for children and strategic investment in their future. The time has come to stop blaming parents, communities, business, and government, and to shape a shared agenda to ensure both a rewarding childhood and a promising future for all children” (NRC & IOM, 2000, p. 414). Health in childhood is insurance for healthier adulthood and is essential for a productive and healthy society.

Ensuring that every child is healthy, ready to learn, and on their optimal trajectory to productive adulthood is imperative for the nation.

SOURCE: Generated by the committee.

This imperative arises from the inherent value of child health, their future health as adults, parent and societal health, and intergenerational health. It also comes from understanding the multigenerational antecedents of child growth and development, as well as the impact of child health and wellbeing on other generations. The committee notes below how these ideas affect Generation 0 (grandparents), Generation 1 (parents), Generation 2 (children), and Generation 3 (children’s future children). Research underscores these value propositions described below and summarized in Table 1-1.

Societal Gain 1: It is a national value and moral imperative to give all children a healthy start in life. The future depends on nurturing young minds and bodies (Gen 2).

Research demonstrates that investment in children and families improves health and education outcomes and health equity, and reduces short- and long-term costs in the childhood years and adulthood (Ash et al., 2023; Chorniy, Currie, & Sonchak, 2018; Heckman, 2006; Hendren & Sprung-Keyser, 2020; Miller & Wherry, 2019). Health in childhood benefits children directly by improving daily lives and progress through childhood tasks. High childhood poverty rates and racial inequities lead to inequities in children’s opportunity to thrive. Community, family, and individual quality of life are enhanced when children are healthy and active. Children have inherent worth beyond economic calculations, and ensuring that all children can thrive affirms values as a society.

TABLE 1-1 Societal Gains from Investing in Child Health

| Societal Gains | Selected Supporting Research | |

1.  |

It is a national value and moral imperative to give all children a healthy start in life. The future depends on nurturing young minds and bodies (Gen 2). |

|

2.  |

Child health and wellbeing support the nation’s tax base, workforce, economic prosperity, and sustain a high standard of living (UNICEF, 2005). The current young adult workforce does not meet national economic and security needs (Gen 2). |

|

| Societal Gains | Selected Supporting Research | |

3.  |

Children who are sick prevent parents from working, playing, resting, and being their full selves. Parent health, happiness, and productivity depend on child health and wellbeing. |

|

4.  |

Child health and wellbeing are essential because children are future caretakers of a growing older population (Gen 0, 1). Maximizing the capabilities of a shrinking population of children is a societal need. |

|

5.  |

Child health is the foundation for adult health. Most adult health problems, including heart disease, diabetes, and mental health, have origins in childhood, and the most effective prevention starts early in life (Gen 2). |

|

| Societal Gains | Selected Supporting Research | |

6.  |

Child health and wellbeing are essential, as children are the next generation of child bearers at a time of declining fertility rates and rising maternal mortality (Gen 3). Healthy reproduction and parenting are essential for the next generation. |

|

7.  |

Scientific and technologic advancement point to the promise of earlier identification and prevention of disease to improve societal health (e.g., genomics, artificial intelligence prediction) (Gen 2). Identification, prevention, and health promotion in the preconception, prenatal, childhood, and adolescent stages pay off. |

|

NOTE: Generation indicators refer to the following: Gen 0 = grandparents; Gen 1 = parents; Gen 2 = children; Gen 3 = children’s future children.

SOURCE: Generated by the committee.

Societal Gain 2: Child health and wellbeing support the nation’s tax base, workforce, economic prosperity, and sustain a high standard of living (UNICEF, 2005). The current young adult workforce does not meet national economic and security needs (Gen 2).

At a time of U.S. labor shortages, a healthy and prepared workforce is essential. However, the rising youth and young adult mortality rates and the

child mental and behavioral health crisis threaten this workforce. In early 2023, the U.S. military reported that 77% of American youth ages 17–24 would not qualify for military services, an increase from 71% in 2017, because of health issues including obesity and behavioral health conditions and because of lack of necessary academic requirements. For the first time, the U.S. Army fell 15,000 recruits short of its annual goal (Council for a Strong America, 2022, 2023a,b). The Navy and Air Force also fell short of their goals.

The United States is also experiencing a historic decline in fertility, with all states but one reporting lower 2020 birth rates compared with averages over the decade ending in 2010 (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2022). While lower birth rates may save education and health costs, they portend resource challenges related to a smaller pool of workers, which will likely suppress income, sales, and other tax revenues. Several factors influence the declining birth rate in the United States, including high child care costs, economic instability, and changing societal norms regarding family planning and women’s roles in the workforce (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2023a; CDC, 2024o). However, healthy and thriving children are necessary to grow the nation’s economy, improve public safety, and strengthen national security. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health disorders impact lifelong health and opportunity, as well as productivity in adulthood (CDC, 2019b; Felitti et al., 1998; Jones, Merrick, & Houry, 2020a).

There is also strong evidence that investing in the health of children can improve workforce outcomes. A recent CBO working paper found that Medicaid enrollment during childhood has been shown to increase earnings in adulthood, supporting earlier research on the benefits of Medicaid (Currie & Chorniy, 2021; Hakim, Boben, & Bonney, 2000). The report went on to find that long-term fiscal effects of Medicaid spending on children could offset half or more of the program’s initial outlays (Ash et al., 2023).

Societal Gain 3: Children who are sick prevent parents from working, playing, resting, and being their full selves. Parent health, happiness, and productivity depend on child health and wellbeing.

The COVID-19 pandemic starkly demonstrated that parents cannot work and experience heightened levels of stress if children are not healthy or not in school (Alonzo, Popescu, & Zubaroglu Ioannides, 2022). In addition, because children can be vectors of illness to caretakers, child health interventions can protect the health of adults. For instance, pertussis vaccination of children protects adults from illness (Choi et al., 2022). Child and family health are intertwined: child health affects family health and family health affects child health.

Societal Gain 4: Child health and wellbeing are essential because children are future caretakers of a growing older population (Gen 0, 1). Maximizing the capabilities of a shrinking population of children is a societal need.

At a time of low birth rates, an increasing proportion of the U.S. population is over age 60, which will leave a large retired population relying on an undersized group of working-age people. Demographers have suggested that this shortage of children will significantly impact a critical balance of workers and taxpayers with nonworkers (Myers, 2017). The best hope is to invest in and maximize capabilities of all children, thus strengthening the workforce supporting and caring for older people. It is the right thing to do for children, and it benefits older populations as well (Myers, 2017).

Societal Gain 5: Child health is the foundation for adult health. Most adult health problems, including heart disease, diabetes, and mental health, have origins in childhood, and the most effective prevention starts early in life (Gen 2).

The greatest threats to the health of Americans today—such as heart disease, diabetes, and mental health—have their origins in childhood, as do key morbidities of aging populations (e.g., atherosclerosis, metabolic conditions, cancer, neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer and Parkinson’s disease; Chung, Krenek, & Magge, 2023; Koskinen et al., 2023; Reuben, 2018; Wehrle et al., 2020). Life course research has demonstrated early antecedents to adult disease and developmental origins of health and disease (Carmeli et al., 2020; Hajat, Nurius, & Song, 2020; Lynch & Smith, 2005). Longitudinal studies have identified childhood antecedents to the pace of aging (Belsky et al., 2017; Colich et al., 2020; Wehrle et al., 2020). Inequities affect health early and may accumulate across the life course. Therefore, prevention and health promotion early in the life course offer opportunity to improve the nation’s long-term health and longevity. Interventions in childhood have both health and economic payoffs in adulthood (Ash et al., 2023; Olds et al., 1986). Health and educational interventions have the highest return on investment when they are focused early in the life course (Heckman, 2006).

Societal Gain 6: Child health and wellbeing are essential, as children are the next generation of child bearers at a time of declining fertility rates and rising maternal mortality (Gen 3). Healthy reproduction and parenting are essential for the next generation.

Today’s children are the child bearers of the next generation, and their health and wellbeing are essential for healthy reproduction, optimal parenting, and healthy offspring. Currently, the United States faces a declining

fertility rate and increasing maternal mortality with wide racial disparity. CDC reports that four in five pregnancy-related deaths in the United States are preventable with adequate patient-centered care (Trost et al., 2022). Research demonstrates the importance of preconception and prenatal health and culturally competent care in birth outcomes (National Academies, 2019d).

Societal Gain 7: Scientific and technologic advancement point to the promise of earlier identification and prevention of disease to improve societal health (e.g., genomics, artificial intelligence prediction; Gen 2). Identification, prevention, and health promotion in the preconception, prenatal, childhood, and adolescent stages pay off.

Advancing science in genetics, prediction by artificial intelligence, understanding of social determinants of health, health services research, population health research and interventions, and health care financing innovations all emphasize the potential of earlier identification of health conditions, prevention, and health promotion (see Chapters 3, 4, and 5). The capability to ascertain the whole genome sequence of a fetus in utero is available. Health care providers will increasingly predict and preempt diseases that may manifest later in life. With these advances and appropriate ethical and legal safeguards, health care can shift to treating diseases earlier in the life course and minimizing or eliminating health consequences for individuals and society. This shift both improves quality of life and reduces the financial burden on health care systems, particularly in the senior years, when the costs of adult entitlements are most significant (Musich et al., 2016; Seow et al., 2022).

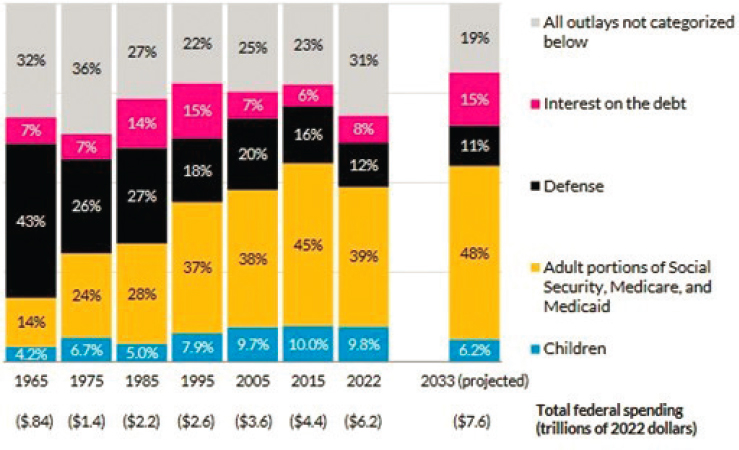

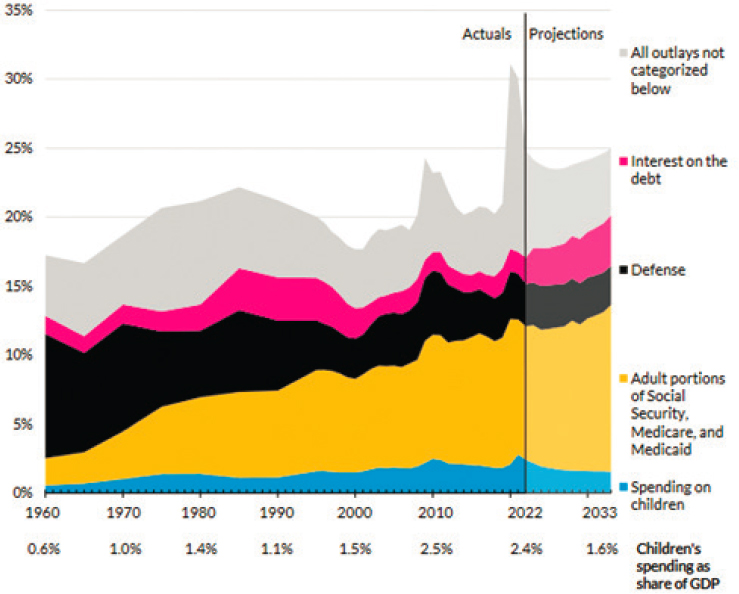

DECLINING INVESTMENT IN CHILD WELLBEING DESPITE DEMONSTRATED BENEFIT

The previous section lays out the importance and value of investing in children for the nation’s future. U.S. public spending on children and families as a percentage of GDP is lower than in other industrialized countries, and such spending is correlated with child health outcomes (National Academies, 2019a). The Urban Institute’s 2022 Kids Share report shows that outlays for children under age 18 were the focus of only 9.8% of the federal budget (Lou et al., 2023). Figure 1-4 depicts how this share is projected to decline to 6.2% over the next decade (a 37% decline), based on laws in place as of March 30, 2023. It is estimated that in 2023, the federal government spent more on interest payments on debt than it spent on children. And by 2033, the federal government is projected to spend far more on adult entitlement programs than on children, as depicted in Figure 1-5 (Lou et al., 2023). These expenditures include adult Social Security,

NOTE: Numbers may not sum to totals because of rounding.

SOURCES: Lou et al., 2023. Authors’ estimates based primarily on Congressional Budget Office, 2023a, Office of Management and Budget, 2023, and past years’ release of these reports.

Medicare, and Medicaid spending, which in recent years has reached approximately 40% of total federal outlays. Even after including state and local spending that covers high child educational costs, total public spending benefiting seniors is still about twice the amount spent on children each year (Lou et al., 2023). While children under age 18 made up 40% of Medicaid enrollees in 2019, they consumed only 17% of total Medicaid spending (KFF, 2019). With adults imposing the largest costs in the health care system, many population health efforts have focused on adults with high health care costs and the Medicare population, with less attention to prevention and child health.

COVID-19 relief bills benefited children and families, but other budget priorities grew even more. During the pandemic, it is estimated that total federal outlays grew from 20% of the GDP to a post–World War II high of more than 30%, then fell to 25% of the GDP in 2022. In contrast, spending on children grew from around 2% of the GDP prepandemic to 2.8% in 2021, and declined to 2.4% in 2022 (Lou et al., 2023).

Many pandemic benefits for children and families were short lived, despite evidence of the deleterious long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on child socioemotional, educational, and mental and physical

NOTE: Totals shown along the horizontal axis are the share of GDP spent on children in the corresponding year.

SOURCE: Lou et al., 2023. Authors’ estimates based primarily on Congressional Budget Office, 2023a, Office of Management and Budget, 2023, and past years’ release of these reports.

health outcomes, especially among those from low-income and historically marginalized communities (National Academies, 2023c). Three rounds of economic impact payments were made; the child tax credit, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and federal Medicaid funding were all increased; and the Education Stabilization Fund expanded child care funding. The pandemic child tax credit reduced poverty in 2021 (Burns & Fox, 2022; as had been demonstrated historically; National Academies, 2019a), decreased child abuse and neglect reports (Bullinger & Boy, 2023), and alleviated food insecurity (Bovell-Ammon et al., 2022; Shafer et al., 2022). As COVID-19 emergency funds were spent down and the pandemic child tax credit expired, child poverty more than doubled in 2022—from 5.2% in 2021 to 12.4% according to the supplemental poverty measure (Shrider

& Creamer, 2023)—and child abuse and neglect reports have again risen (Department of Health and Human Services, 2024). The pandemic highlighted racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic inequity; structural racism; slow response; and long-lasting negative impact on children, pregnant women, and families (National Academies, 2023c). Nonetheless, it is projected that by 2033 all categories of expenditures on children as a share of GDP will decline below current levels and most will decline below prepandemic levels (Lou et al., 2023).

LACK OF ATTENTION TO THE UNIQUE NEEDS OF CHILDREN

The differences between pediatric and adult care noted above (the 5 Ds) lead to differences in health care delivery and research needs. Most of health care innovation occurs in adult delivery systems, given the higher expenses for older groups. This approach often leaves out the needs of children, especially those with rare conditions, and innovations in adult health care may have unintended negative consequences for children. A few examples are discussed below.

Pediatric Health Care and Pediatric Clinicians

Pediatric health care and maternity care require specialized medications, diagnostics, therapeutics, equipment, and staff. Pediatric health care relies on Medicaid/CHIP, covering almost half of U.S. children, yet lower payment makes access to primary care and subspecialty care difficult for many children with public insurance. Pediatric inpatient beds are less profitable than adult beds, contributing to the closure of pediatric units and maternity wards, which has resulted in further access challenges (Cushing et al., 2021; Shachar, Gruppuso, & Adashi, 2023). More than half of U.S. rural hospitals no longer offer birthing services (Anderer, 2024; Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, n.d.). A retrospective study of 4,720 U.S. hospitals using the 2008–2018 American Hospital Association survey found that pediatric inpatient units decreased by 19.1% and pediatric inpatient unit beds decreased by 11.8%, with rural areas seeing the largest decreases (Cushing et al., 2021). It was estimated that one-quarter of U.S. children experienced an increase in distance to their nearest pediatric inpatient unit. While some evidence has found increased care quality associated with regionalization of medical services, there is also evidence of poor outcomes related to distance and transportation barriers.

Additionally, pediatricians remain the lowest-paid specialty in medicine (Ickes, 2023; USAFacts, 2023); other child-focused professionals, including nurses, mental health providers, teachers, and child care workers, also have low salaries. The lifetime earning potential for adult physicians averaged 25% more ($1.2 million higher) than for pediatric physicians

across all comparable areas of both general and subspecialty academic practice (Catenaccio, Rochlin, & Simon, 2021). With many medical students graduating with high debt, the percentage of U.S. medical school graduates entering pediatrics has been in decline, with earning potential cited as a factor (Azok et al., 2024; Vinci, 2021). The National Academies (2023e) report The Future Pediatric Subspecialty Physician Workforce also detailed the growing shortages of many pediatric subspecialists. The lowest-paid specialties have the greatest shortages in fellowship program fill rates (e.g., pediatric nephrology, child abuse pediatrics, pediatric infectious disease, pediatric rheumatology, developmental-behavioral pediatrics, pediatric endocrinology).

Pediatric Drug Development and Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic tools, devices, and treatments developed for adults do not immediately or easily translate to pediatrics, and some disorders present only in childhood. The economic environment for drug discovery and development strongly favors a focus on therapeutics for common adult conditions over conditions affecting children or rare diseases. As a result, off-label drug use and drug shortages are more frequent and even commonplace in pediatric care, despite some evidence that off-label use is associated with higher rates of adverse effects in children (Turner et al., 1999). High rates of off-label prescribing outside of an approved age, indication, weight, dose, formulation, or route of administration occurs in inpatient settings (36–92%) and especially neonatal and pediatric intensive care units (80–97%; Cuzzolin, Atzei, & Fanos, 2006; Pandolfini & Bonati, 2005; Turner et al., 1999). In the ambulatory setting, nearly 1 in 5 pediatric visits resulted in the ordering of one or more off-label drugs; 45–60% of pediatric visits when drugs were prescribed included off-label orders (Bazzano et al., 2009; Hoon et al., 2019). Off-label use has risen in recent years, most notably for antihistamines and psychotropic drugs, including antidepressants (Hoon et al., 2019). Testing of pharmaceuticals is especially limited in pediatric oncology—at the time of first approval of adult oncology drugs, only 5.1% have pediatric labeling information (Bicer et al., 2023; Hwang et al., 2020). In a study using a ClinicalTrials.gov review of pediatric-relevant cancer drugs that were starting efficacy testing in adults, only 34% of the 185 drugs were evaluated in minors (Bicer et al., 2023).

Laws and policies have attempted to incentivize or mandate pediatric clinical trials to reduce off-label use. The Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA, 2002), Pediatric Research Equity Act (2003), and European Pediatric Regulation (2007) have helped increase pediatric studies, and BPCA provides a voluntary incentive. However, drug companies still often fail to include children, with off-label pediatric drug use increasing.

Finally, shortages of essential drugs, including chemotherapy drugs, have been increasing in the United States and Europe (Huss et al., 2023), disproportionately and negatively impacting care of pediatric patients (Butterfield, Cash, & Pham, 2015). Pediatric patients may be at particular risk of harm because of a comparative increase in the use of impacted medications (e.g., parenteral nutrition) and the relative lack of quality pediatric data (or Food and Drug Administration–approved indications for pediatric use) to guide the selection of alternative medications (Butterfield, Cash, & Pham, 2015). Children are a vulnerable group with very limited pharmaceutical treatment options. Strengthened protections are needed.

The development, safety, and effectiveness of laboratory tests is another area requiring unique consideration for children. Diagnostic tools developed for adult populations may not translate to pediatrics and require validation study. Again, the economics of developing diagnostic tests for a relatively small population are a challenge. Reference ranges for children may vary significantly by age, gender, and other factors, requiring additional effort. Laboratory-developed tests by children’s hospitals and pediatric academic medical centers fill a critical gap in developing and validating diagnostic tests.

Health Care Innovations and Pediatrics

With continual innovation in health care, addressing the unique needs of children and impacts on children and low-income and minoritized communities must be considered and addressed early. Three examples of health care innovations are discussed: one results in delays in realizing the benefits of technology for children; another results in children suffering unintended consequences of innovation focused on adults; in the third, children have not been included.

While electronic health records (EHRs) and related innovations now function in almost all pediatric health care settings, initial design was for adult care, and use of pediatric customization and functionality continue to lag. While EHR adoption has increased significantly in pediatric practices since 2005, when only 21.3% of pediatric primary care practices had EHRs (Kemper, Uren, & Clark, 2006), challenges persist in implementing pediatric-specific functionalities. The Children’s Electronic Health Record Format, developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and CMS, outlines critical functionalities and data elements specific to pediatric EHRs, highlighting the need for specialized features (Dufendach et al., 2015). Yet, over 80% of pediatric clinicians use EHRs lacking optimal functionality for pediatric care, leading to potential errors in clinical decisions, misdiagnosis, and medication dosage miscalculations (Temple et al., 2019), and many EHR systems lack essential pediatric features such as specialized growth charts, vaccine management tools, and age-appropriate

developmental screening templates (AHRQ, 2014; Dufendach et al., 2015; Lehmann et al., 2014). These ongoing challenges suggest that while progress has been made, EHRs and related innovations continue to fall short in fully addressing the unique needs of pediatric care, and progress has still fallen behind progress for older populations (Nakamura et al., 2013; Weinberg et al., 2021).

Another example of health care innovation that left out or had unintended negative consequences for children has involved the move to alternative payment models and value-based care. The majority of these experiments have occurred with adults and Medicare recipients. In fact, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation was directed to address the likelihood of cost savings within an unspecified period of time, typically defined as 18–36 months (Badger, 2022; CBO, 2023a). This short time frame for return on investment is particularly difficult to demonstrate for innovations for children, and the cost-saving directive has stymied effort in payment reform to support prevention and health promotion early in the life course.

Experiments with alternative payment models can deprioritize focus on children and primary prevention. One example is in the state of Maryland, which has a unique all-payer rate-setting system for hospital services (Cheng, 2023). The model approved in January 2014 was developed by the state and CMS to shift from volume-based reimbursement to a global budget revenue system in an effort to align hospital incentives with community and primary care efforts and to decrease health care costs. Since children contribute only a small portion of the total cost in the health care system, this population health effort focused on Medicare patients and other adults.

Initial areas of priority in Maryland’s initiative were diabetes, opioid use, and establishment of the Maryland Primary Care Program. Despite clear roots of many health conditions in childhood, primary prevention efforts in childhood would not show needed short-term cost savings, resulting in exclusion of children in these initiatives with a focus on secondary and tertiary prevention with adults. The Maryland Primary Care Program offered prospective payments for advanced primary care, but eligibility was based on a minimum number of Medicare beneficiaries. Very few in the maternal and child health population are insured by Medicare, and thus maternal and child health practices were not included. Health care delivery systems followed the state’s lead in their investments. Because pediatrics and obstetrics fall under global budgets for large health care delivery systems, the focus was on the majority adult population and Medicare metrics. As CMS expands new voluntary, state total-cost-of-care models, attention to prevention and inclusion of children are needed.

Finally, the current National Institutes of Health initiative to develop a database of 1 million Americans, an example of precision public health,

has been an exciting opportunity for understanding developmental origins of health and disease starting early in the life course. However, after over 6 years of recruiting nearly 800,000 adults and publication of the monograph Opportunities Enabled Through the Enrollment of Children in the All of Us Research Program in 2018, child enrollment has just begun (All of Us Research Program Investigators, 2019; Kaiser, 2024).

Inclusion of children, consideration of their unique needs, and addressing health equity are prerequisites for policy initiatives, legislation, and innovation.

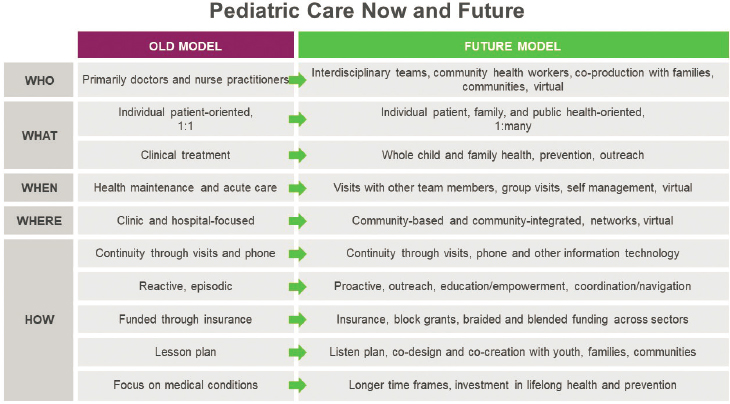

VISION FOR IMPROVING THE HEALTH AND WELLBEING OF CHILDREN AND YOUTH

Early in its deliberations, drawing on the expansive literature discussed above and the growing consensus within the health care field on principles and attributes of health care, the committee crafted a vision for improving the health and wellbeing of children and youth. We envision a child and adolescent health care system a decade from now built on traditional knowledge and the evidence regarding early life experiences, human development, and disease prevention (see Chapter 2) to provide comprehensive, family-engaged, community-integrated, and equitable care focused on optimizing the healthy development and lifelong wellbeing of all children, youth, and their families. This health care system will exist in a broader, cross-sector system, especially including the work of schools, which equitably promotes flourishing, builds on community strengths, and addresses family and community needs to create the safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and environments that all children need to thrive. The major causes of child and adolescent morbidity and mortality and the lived knowledge and expressed needs of children, youth, and families will guide the priorities for how the health care system allocates its resources to achieve this vision (see Chapter 3). Figure 1-6 illustrates how the characteristics of care would change.

Ensuring that the lived knowledge and expressed needs of children, youth, and families set the priorities for the health care system is a critical component of a future transformed system. Existing endeavors to advance health care transformation often fail to include people with lived experience in their development and evaluation. Many local health care systems have sought ways to incorporate such experiences into the design and improvements of policies and services.

Several key advances in health and health care already support change and progress expected in the next 10 years, including better and earlier diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions, innovations in team-based care, integrated mental and behavioral health, inclusion of the family and child

SOURCE: Generated by the committee, adapted from Cheng, 2004.

voice, and improved coordination of care with community services that address social determinants of health. The growth of artificial intelligence and genomics will support and expand these advances. The major mental health crisis—combined with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on schooling with clear inequities between different population groups among America’s children and youth—has highlighted needs and led to efforts to expand mental and behavioral health services, especially in primary care and schools but indeed across the spectrum of child and adolescent health services (National Academies, 2023b). Going forward, mental and behavioral health will have a prominent place in health care, which will necessitate expanding prevention and early identification of conditions affecting mental and behavioral health and integrating treatment (see Chapter 5).

Recognizing that the major causes of child and adolescent morbidity and mortality involve injury, violence, and social determinants of health, primary care involvement in addressing family and community challenges and needs will be important for improving child health. Furthermore, as medicine has advanced and more children survive previously fatal conditions, the larger proportion of children with chronic and complex conditions will challenge the health care system to design new models of care, including remote patient monitoring and intensive home care.

What will the child health care system of the future look like? Healthy children entering adulthood will have histories without major family or community adversity and will have healthy behaviors and mental and behavioral wellness, along with educational skills and resilience. Any chronic condition