Launching Lifelong Health by Improving Health Care for Children, Youth, and Families (2024)

Chapter: 2 Science and Frameworks to Guide Health Care Transformation

2

Science and Frameworks to Guide Health Care Transformation

The first mandate [...] is to ensure that our decision-making is guided by consideration of the welfare and well being of the seventh generation to come.

—Bemidji Statement on Seventh Generation Guardianship

Development of children and youth is characterized by continuous skills attainment, growth, and transition, thereby setting a trajectory upon which adult health builds. Such health, wellbeing, and developmental trajectories are shaped by consequential influences across social, environmental, and relational contexts. This chapter discusses the science of healthy child and youth development as the base for a life course perspective on improving child and family health and clarifying the importance of relational health throughout the life course. To describe the dynamic nature of child health and development, the chapter provides an overview of critical stages in development. It describes the scientific bases and important advances in science and technology that guide efforts to improve child health and wellbeing, and it outlines social and environmental factors—at individual and community levels, as well as at the broader population level—that influence the life course. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the implications of these scientific streams—the science of child and youth development, key scientific and technological advances, and the social determinants of health—to guide health care transformation.

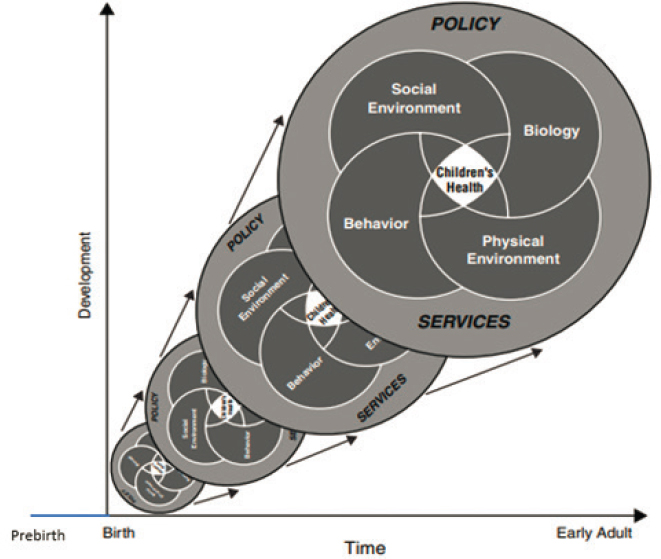

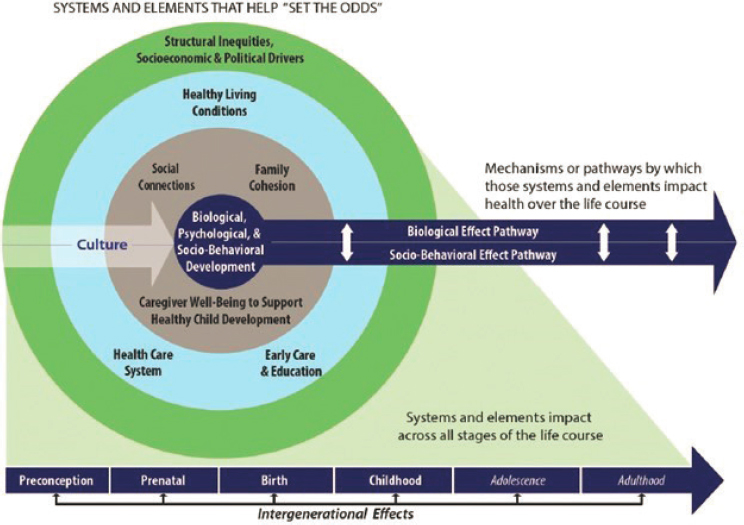

LIFE COURSE AND MULTIGENERATIONAL PERSPECTIVE

Childhood is a time of wonder, with developmental stages progressing from conception and infancy to childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Growing research demonstrates many early antecedents to adult health and disease and aging (Braveman & Barclay, 2009; Horvath & Raj, 2018; Joseph & Kramer, 1996; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies], 2019b,c,d; Raffington, 2024; Wehrle et al., 2020). Multiple factors affect life course developmental stages, including structural inequities and racism; social determinants of health; environmental exposures; and individual behavioral, social, and biological mechanisms. A previous report by the National Academies, Children’s Health, The Nation’s Wealth, provides a model of children’s health and its influences across life stages (see Figure 2-1; National Research Council [NRC] & Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2004). The model illustrates multiple influences—including biology, behavior, and physical and social environments—that interact over time to create children’s health. Programs, services, and policies affect how these influences operate in a child’s life. The relative weight of these

SOURCE: Adapted from NRC and IOM, 2004, Figure ES-1.

influences and interactions varies in different developmental stages; previous stages influence later development. Changes in a child’s health resemble a kaleidoscope of glass pieces representing various influences that create different patterns of health over time from birth to adulthood.

An addition to this model was the extension of the x-axis to include prebirth. Research demonstrates the importance of fetal health and parents’ preconception health on a child’s health (National Academies, 2019d; Schrott, Song, & Ladd-Acosta, 2022). Ensuring child wellbeing requires considering conditions prior to birth, as well as the health of the family unit across the life course. Understanding how to support healthy developmental trajectories will be important for transformation at the practice, policy, and systems levels to ensure that all children and families have the opportunity to realize positive trajectories.

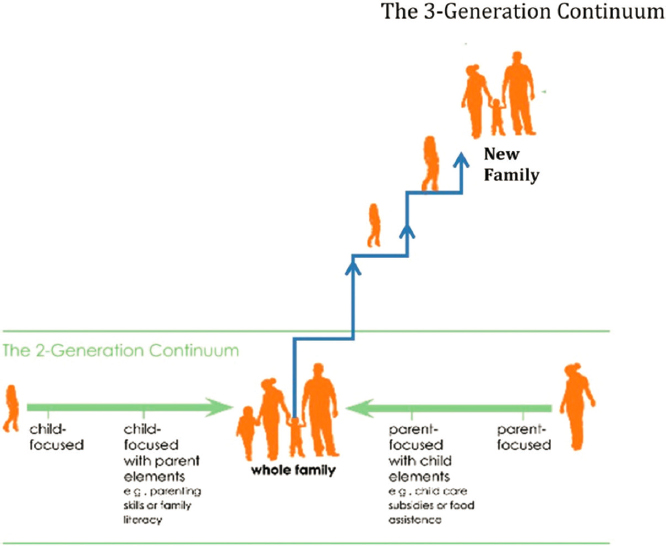

Pediatric practice has long adopted a two-generation approach to care, with focus on both children and parents. With recognition of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors affecting health risks for the next generation, a longer view is needed (Cheng, Johnson, & Goodman, 2016; Hanson & Gluckman, 2014). A growing body of literature documents the intergenerational transmission of health and disease and transgenerational effects of social and environmental exposures and epigenetics on health (Benincasa, Napoli, & DeMeo, 2024; Breton et al., 2021; Kioumourtzoglou et al., 2018; Scorza et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2024). In addition, beyond the importance of their health today, as future adults, children and youth are also the child bearers for the next generation. A three-generation approach considers the health of children, the adults they will become, and the new families they will create (see Figures 2-2 and 2-3). This proactive prevention approach for the next generation emphasizes child and family health, child educational success, family planning, and parenting education starting before childbearing (Cheng, Johnson, & Goodman, 2016).

Modern understanding of the origins of health confirms long-understood traditional and Indigenous knowledge. Many Indigenous communities have followed the principle of Seven Generations, which understands that present actions will affect the next seven generations (Loew, 2014). Based on ancient Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) philosophy, this principle emphasizes present decision making that considers potential effects on descendants seven generations in the future (Haley, 2021). These Indigenous principles do not focus solely on the intergenerational impact of trauma; instead, they center a strengths-based approach that understands, among many things, the value of relational health, intergenerational healing, and collective wisdom in realizing communal health and wellness (Fish et al., 2023; O’Keefe, Fish et al., 2022; O’Keefe, Maudrie et al., 2023). This report is guided by a life course and multigenerational framework for health care transformation.

CRITICAL PERIODS IN DEVELOPMENT: OPPORTUNITIES FOR HEALTH CARE TRANSFORMATION

Life course theory highlights critical and sensitive periods in development. These concepts have been part of developmental science recognizing periods when certain experiences, exposures, or conditions exert disproportionate influence or malleability over long-term outcomes (Colombo, Gustafson, & Carlson, 2019). “Sensitive periods” are limited developmental time windows during which experiences have great effect; “critical periods” are subsets of sensitive periods in which normal development is impaired without appropriate nurturing and stimulation (Knudsen, 2004; Voss, 2013).

For example, the National Academies report Addressing the Long-Term Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Families noted that the pandemic was an adverse childhood experience for many and that the effects on child development and outcomes differ depending on child age and developmental stage (National Academies, 2023b). Further examples include pregnancy and childbirth, which usher in excitement for opportunities from the start and hope for the future. Infancy, childhood, and adolescence celebrate the wonders of child growth and development in the domains of social, emotional, physical, cognitive, and language development. Late adolescence and young adulthood mark the transition to adulthood—becoming independent; developing one’s identity; handling more complex relationships; and taking on new roles and responsibilities in education, employment, and family formation.

Understanding and optimizing these developmental periods and ensuring that the health care system provides developmentally appropriate care across these life stages are necessary for children to thrive. The following sections summarize these developmental periods and give examples of health care opportunities to strengthen these stages and transitions.

Preconception and Prenatal Women’s Health

Considerable evidence demonstrates the impact of baseline maternal health (e.g., diabetes, obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, depression) and behaviors (e.g., smoking, drug use, physical activity, nutrition) on offspring outcomes in childhood and adulthood (Castro & Avina, 2002; Kleinman et al., 1988; Orr & Miller, 1997; Ryder, 2018; Walford et al., 2011; Xiong et al., 2006; Zuckerman et al., 1989). These associations indicate the need for early prevention in mothers before or during pregnancy (Ryder, 2018). The story of folic acid supplementation is a powerful example of how a preconception intervention influences child health. The educational campaign and fortification of grains led to a 26% drop

in the rate of neural tube defects (De-Regil et al., 2010; Howse, 2008). Recent evidence suggests that women should start taking folic acid supplements at least 3 months before conception for optimal effectiveness, as neural tube defects occur during the first 28 days of pregnancy (Kim et al., 2017; Viswanathan et al., 2023). In a multisite cluster-randomized trial, a maternal health screener and brief interconception intervention in pediatric primary care were found to be feasible and effective in increasing daily folic acid use and decreasing smoking (Upadhya et al., 2020). With growing scientific recognition that early antecedents of child and adult health start prenatally and even preconceptionally, women’s health is key (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2019).

Family health affects child health. Thus, family health care access and intended family size may have large influence on a child’s health. Pediatric health care providers have the opportunity to address the health of children, their mothers and fathers, adolescents and young adults who will be future child bearers. Preconception and interconception health affect future generations; improving population health must embrace the entire life course and the origins of disease.

Early Childhood and Family Health

The National Academies report From Neurons to Neighborhoods emphasized the rapid brain development that occurs from birth to age 5 years, with children rapidly developing foundational capabilities on which subsequent development builds (NRC & IOM, 2000). Early experiences influence brain development, and the prenatal and early childhood years are particularly sensitive periods in development. Additionally, parental wellbeing is an important determinant of children’s health and developmental outcomes: what happens to parents before, during, and after pregnancy has major implications for their children (Center on the Developing Child, 2009; Goodman & Garber, 2017; National Academies, 2019b,c).

Promoting health and resilience requires—beyond reducing exposure to adversity—increasing relational health and forming and maintaining safe, stable, and nurturing relationships (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2020). Strong relationships not only help downregulate the stress response in a child but also help build skills, such as self-regulation and executive function, that assist children in managing future adversity (National Academies, 2019b,c; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2020).

There is evidence that not only are the brains of infants primed to interact socially and emotionally with adult caregivers but that the brains of parents of a newborn infant also enter a critical period such that they are primed to interact with their child (Garner & Yogman, 2021a,b). Responsive interactions between children and engaged adults appear to be

of fundamental importance to establishing healthy brain architecture and the health-promoting body system responses that go along with it (Garner & Yogman, 2021a,b). Healthy caregiver–child relationships develop a dyadic synchrony that can include synchronized autonomic function, hormone release, and brain-to-brain synchrony with coordinated oscillation in brain wave types between caregiver and child (Garner & Yogman, 2021a,b).

School-Age Children

The years children are in school (“school age” generally refers to ages 5–12 years) is a period of rapid acquisition of physical, cognitive, language, and socioemotional skills. Children move from playing alone to having multiple friendships and social groups. They develop independence and take on more responsibility for their activities, schoolwork, health, and safety. School occupies much of their time. The Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF), an independent, nonfederal panel that provides evidence-based recommendations to improve population health, recommends the implementation and maintenance of school-based health centers (SBHCs) in low-income communities to improve educational and health outcomes. Research demonstrates that SBHCs improve educational outcomes—including school performance, grade promotion, and high school completion—and health outcomes—including the delivery of vaccinations and other recommended preventive services, as well as decreases in asthma morbidity and emergency department and hospital admission rates (CPSTF, 2015). Schools also offer an effective and opportune place for addressing health and chronic disease management, and potentially preventing, identifying, and managing mental health conditions among school-age children and adolescents (Office of the Surgeon General [OSG], 2021; see also Chapter 8 in this report).

Adolescents and Young Adults

Adolescence (ages 13–25) is another time of significant social, emotional, physical, and cognitive development (National Academies, 2019c). Puberty triggers not only visible growth and changes in physical characteristics, including primary and secondary sex characteristics, but also neurobiological and cognitive changes. These changes enable youth to engage in more complex thinking and heighten sensitivity to rewards; willingness to take risks (sensation seeking); identity development; reorientation of attention and motivation (toward peers, social evaluation, status and prestige, and sexual and romantic interests); and changes in social contexts, roles, and responsibilities. In emerging adulthood (approximately age 19 through the mid- to late twenties), young people become even more independent and begin exploring various life possibilities. The process of identity formation (in the realms of relationships, education,

and work) that began during adolescence continues to materialize during these emerging adult years.

Parents and other adult caregivers are no less important for adolescents than they are for young children: both young children and adolescents need secure attachment with parents or other important adults as a foundation for healthy development and strong relationships (National Academies, 2019c). There is evidence that strong parent or other adult relationships, involvement, and connectedness are associated with better adolescent health and reduced problem behavior (National Academies, 2020d). In a study that looked at flourishing for children ages 6–17 years, a measure of family resilience and connection was strongly associated with a greater percentage of children flourishing, regardless of the number of adverse childhood experiences reported for the children (Bethell, Gombojav, & Whitaker, 2019).

Health-related behaviors during adolescence and emerging adulthood are strongly associated with health status in adulthood (National Academies, 2020b). Engaging in unhealthy (unhealthy diet, lack of exercise) and/or risky behaviors (alcohol and other substance use, tobacco use and vaping, sexual behavior, violence, dangerous driving) can have a long-term impact on both physical and mental health in adulthood (National Academies, 2020b). A growing body of research examines associations between social media use and mental and behavioral outcomes, of key concern for adolescents and youth who increasingly spend time on such platforms. A recent National Academies report, Social Media and Adolescent Health, did not support the conclusion that social media causes changes in adolescent health at the population level but pointed out potential harms and benefits and needed actions to protect young people (National Academies, 2023g).

Adolescents are also more sensitive than children or adults to the presence of peers (Casey et al., 2010). By middle to late adolescence, youth report relying more on either best friends or romantic partners than on parents for emotional support (Farley & Kim-Spoon, 2014). Although these interpersonal relationships can increase stressors and negative emotions, they can also, when of high quality, protect against the negative effects of stressful experiences (Farley & Kim-Spoon, 2014; Yeung, Thompson, & Leadbeater, 2013). Social isolation, peer rejection, and bullying are associated with numerous unhealthy risk behaviors and adverse health outcomes, such as increased delinquency, depression, numbers of suicide attempts, and low self-esteem (Smokowski & Evans, 2019). Notably, evidence consistently shows a reduction in risky sexual behaviors and substance abuse among U.S. adolescents over the past 20–25 years; however, experiences of violence are increasing in some cases and poor mental and suicidal thoughts and behaviors are increasing for nearly all groups of youth (Borodovsky et al., 2020; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2023i; National Academies, 2020d). Positive peer modeling and awareness of peer norms have been found to be protective against violence, substance

misuse, and unhealthy sexual risk (Viner et al., 2012). A network of supportive relationships with parents, peers, and other caring adults can set the foundation for lifelong health and development.

SCIENTIFIC BASES FOR HEALTH CARE TRANSFORMATION: DEVELOPMENTAL ORIGINS OF HEALTH AND DISEASE

The interplay among life experiences, genes, age, and the environments in which children live lays the foundation for early childhood development and health later in life (National Academies, 2019c,d; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2020). Animal studies and epidemiological observations have demonstrated that environmental influences early in development affect the risk of later pathophysiological processes associated with chronic disease. These interconnected factors are known as the developmental origins of health and disease (Hanson & Gluckman, 2014).

Large bodies of evidence make clear how health and development reflect the interplay among genes and the environment, with major effects of the environment especially early in life. As summarized in a recent National Academies report, Vibrant and Healthy Kids, “New research has clarified that altered nutrition, exposure to environmental chemicals, and chronic stress during specific times of development can lead to functional biological changes that predispose individuals to manifest diseases and experience altered physical, socio-emotional, and cognitive functions later in life” (National Academies, 2019d, p. 6). Vibrant and Healthy Kids provides evidence about the importance of intervening early, especially in light of U.S. problems with infant mortality, low birth weight, childhood chronic disease and mental and behavioral conditions, early life adversity, poverty, lapses in health insurance, and inequities in care. While the environment influences individuals throughout life, early months and years carry the most import for changes in many human systems, from brain development to immune function to endocrine responses to physical development. Early life experiences, both positive and negative, tremendously influence how a child grows, thrives, interacts, learns.

The body’s “fight or flight” stress response system, and inflammation related to activation of that system, plays a central role in mediating these effects. When a stressor occurs, the body’s autonomic nervous system, immune system, metabolic systems, and neuroendocrine system all interact with the brain and each other to respond (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2020). If the stress response is short lived because of either the nature of the stressor or the mitigating effect of supportive relationships (e.g., a child’s first day at school), the body systems return to a baseline state and the experience can promote development for the child. If the stress response activation is prolonged, severe, or frequent—for example in the context of ongoing physical abuse, exposure to community violence,

or discrimination—in the absence of supportive relationships, the body systems responses that are adaptive and helpful in dealing with the stressor can lead to allostatic overload or wear and tear on the brain and body, resulting in negative long-term health outcomes. Chronic inflammation—associated with unmitigated chronic stress activation—is associated with increased risk for a number of chronic conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, depression, arthritis, gastrointestinal disorders, autoimmune disorders, multiple types of cancer, dementia, and asthma (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2020).

“Genes,” heritable units of genetic material composed of DNA, provide the molecular instructions that determine specific traits (National Human Genome Research Institute [NHGRI], 2024b). “Epigenetics” refers to chemical modifications in DNA that alter the degree to which genes are turned on or off without modifying the underlying genetic code itself (NHGRI, 2024a). The interaction of experiences and genes in the context of relationships affects brain architecture and the regulation of the autonomic nervous system, the immune system, metabolic systems, and the neuroendocrine system (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2020). In addition to known genetic predispositions to specific chronic diseases, variations in genes and gene expression are associated with a person’s physiologic response to stressors, which can result in an increase or a decrease in the negative consequences of exposure to adversity (Boyce et al., 2021; National Academies, 2019b). There is evidence that some children are more sensitive to their social environment than others, such that more sensitive children have more positive outcomes in supportive environments and more negative outcomes in unsupportive environments, with genes and gene expression underlying the differences in sensitivity (Boyce, 2016; Boyce et al., 2021). There are many examples of links between health risks and outcomes and specific genes or specific epigenetic modifications in gene regulation (Boyce et al., 2021).

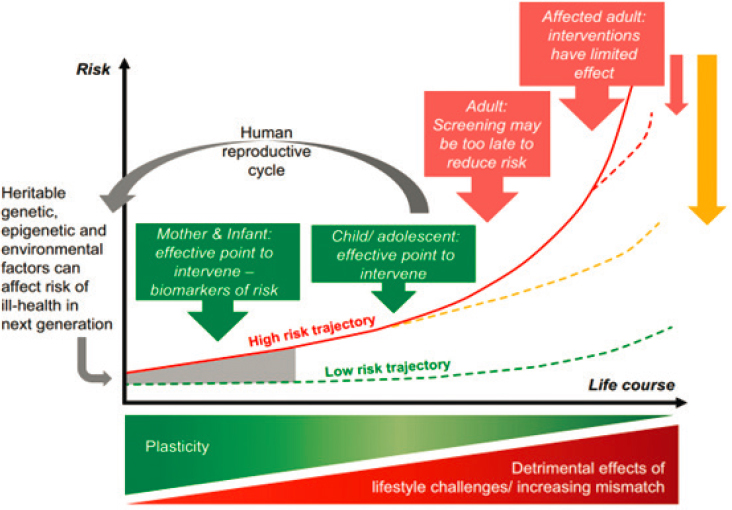

A life course view of health risk (Figure 2-4) outlines the opportunity for early intervention. During windows of plasticity, brain architecture is most sensitive to the effects of experience (Boyce et al., 2021). Sensitive and critical periods are specific windows during development when the brain is particularly receptive to certain environmental stimuli, which significantly shape neural circuits and subsequent behavior.1 These periods are crucial for the development of various functions, including sensory processing,

___________________

1 Different neural circuits have distinct sensitive and critical periods for different functions. For example, during sensory development, the visual and auditory systems have critical periods early in life when exposure to visual and auditory stimuli is essential for normal development (Zeanah & Fox, 2019). Sensitive periods for emotional regulation and cognitive functions extend beyond early childhood into adolescence. During these periods, experiences such as caregiving quality and educational opportunities significantly shape the brain’s emotional and cognitive circuits (Cisneros-Franco et al., 2020; Zeanah & Fox, 2019).

SOURCE: Hanson & Gluckman, 2014.

emotional regulation, and cognition (Boyce et al., 2021; Heun-Johnson & Levitt, 2018; Morishita et al., 2015; Nelson, Lau, & Jarcho, 2014). Because of rapid development during the prenatal period and early childhood (from birth through age 8 years), brain architecture is notably responsive to both positive and adverse experiences, making them particularly important periods for the promotion of health and wellbeing (NRC & IOM, 2015). There is also evidence for adolescence being another critical period, specifically for the development of neural circuits in the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for functions, such as executive function (Larsen & Luna, 2018).

The goal is to diminish the risks to health on this trajectory. Opportunities to do so decrease with age as neuroplasticity declines. Life challenges in earlier stages may lead to cumulative damage in later ones. For adults, who are already on the steeper part of the risk trajectory, screening may be too late to reduce substantial risk.2 Conversely, interventions in childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood offer major opportunities to effectively

___________________

2 It is important to note that research has shown that experiences outside of critical periods can still change outcomes, although more intensity of effort is required. Interventions to promote healthy development of the brain and other body systems can be achieved at all ages (NRC & IOM, 2015).

and cost-effectively influence health later in the life course and in the next generation.

Experiences over the life course have lasting effects. Positive childhood experiences, including the presence of safe, stable, and nurturing relationships, are associated with positive outcomes later in life (Bethell, Gombojav, & Whitaker, 2019; Bethell, Jones et al., 2019; Garner & Yogman, 2021a,b; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2020). Negative experiences, on the other hand, increase the likelihood of poor health in childhood, lower educational achievement, adolescent mental health conditions, adverse risk taking and substance use, incarceration (NRC & IOM, 2015). What is more, negative experiences over the life course lead to higher rates of several chronic health conditions in adulthood, including diabetes, substance use, obesity, mental health conditions, and early death (NRC & IOM, 2015). Adversities in childhood at the population level link to negative health outcomes in adulthood with the risk of negative health outcomes increasing as the number of adversities increases (Felitti et al., 1998). A significant portion of cases of conditions such as depression, asthma, kidney disease, coronary heart disease, and diabetes in the United States have been associated with adverse childhood experiences (Merrick et al., 2019).

As childhood adversity activates chronic stress and the associated, intertwined cascade of brain and body system responses, it also increases the risk of negative health outcomes in childhood and adulthood and helps explain the development of important chronic health conditions.

SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCES

The science of maternal child health and development, coupled with scientific advances in medicine, charts a path forward to applying the tools of precision medicine and precision population health to health promotion, starting early in the life course. Precision medicine seeks to use patient-level phenotypic and genotypic data to tailor care recommendations to improve individual health outcomes (Costain, Cohn, & Malkin, 2020), while precision population and public health addresses social, behavioral, and environmental influences (Bayer & Galea, 2015; Lyles et al., 2018). Both precision medicine and precision public health, combined with technological advances, allow earlier identification of and intervention on health problems at the individual or population level to ensure optimal conditions for health and wellbeing from the start. Including children in these advances is essential for them to realize their potential. Lyles and colleagues (2018) give the All of Us Program—an effort by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to develop a database of 1 million Americans—as an example of precision public health; however, recruitment of children to All of Us just

started after more than 6 years of recruiting nearly 800,000 adults (All of Us Research Program Investigators, 2019), with continued funding to recruit children uncertain. This section discusses examples of exciting new science and technology that has and will continue to transform health care and health, with particular promise early in the life course.

Genetics, Epigenetics, and Gene Therapy

The sequencing of the human genome was completed in 2003, and technological advances have led to an explosion of discoveries in matching genotypes to phenotypes (Hamosh et al., 2021). However, no single genome can fully represent the diversity of the human species; recently, a first draft of a human “pangenome” reference was published that includes both sets of chromosomes from 47 individuals with diverse ancestral backgrounds (Liao et al., 2021). This pangenome will contribute to further equitable and fundamental insights (Frazer & Schork, 2023).

With the genetics revolution, former NIH director Elias Zerhouni (2006) suggested a paradigm shift for medicine, characterized by four “Ps”: predictive, preemptive, participatory, and personalized care. It has been suggested that the fifth and sixth Ps should be pediatrics and prenatal, as it is early in the life course when molecular evidence is knowable and when opportunity for intervention will be possible and potentially more effective (Cheng, Cohn, & Dover, 2008). Future health care will likely center around these six Ps, seizing the opportunity to predict the emergence of future health conditions and prevent, preempt, and buffer the anticipated health trajectory. Prenatal care and pediatrics are at the leading edge.

Genome sequencing has become a standard of care for a growing number of medical conditions and has high diagnostic yield in many conditions, including pediatric rare diseases (Wright et al., 2023). For instance, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis on exome sequencing in cerebral palsy supported the recommendation of exome sequencing in the diagnostic evaluation of individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders (Gonzalez-Mantilla et al., 2023). A recent issue of the Journal of Pediatrics included three articles reporting high yields of genetic testing in children with congenital heart disease, liver dysfunction, and neonatal encephalopathy (Durbin et al., 2023; Lenahan et al., 2023; Stewart et al., 2023). Postmortem study of infant deaths found undiagnosed genetic diseases that would have reclassified infant mortality data (Owen et al., 2023). Polygenic prediction of weight and obesity trajectories across the life course has also been described, with new opportunities for mechanistic assessment and clinical prediction (Khera et al., 2019). The interaction of experiences and genes in the context of relationships brings in epigenetic changes that affect brain architecture and the regulation of the autonomic

nervous system, the immune system, metabolic systems, and the neuroendocrine system (National Academies, 2019d; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2020). Epigenetic mechanisms are responsible for the incredible developmental plasticity in childhood and are exciting areas of research.

Diagnostic yield for genomic sequencing is higher than targeted neonatal gene sequencing, although time to return of results was slower (Maron et al., 2023). As technology for sequencing has become more accurate and rapid, many neonatal intensive care units are expanding use of whole genome and exome sequencing in sick neonates, with studies demonstrating high diagnostic yield (Kingsmore & Cole, 2022). Studies in children’s hospitals have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes and cost savings (Dimmock et al., 2021). In addition, wider use of genome sequencing in utero and as part of newborn screening are imminent. Fetal genome sequencing could become as routine as the fetal ultrasound.

Finally, pharmacogenomics to personalize therapeutics, as well as gene therapy and gene editing to treat, prevent, or cure a disease or medical disorder, are making rapid progress. Gene therapy may involve replacing a disease-causing gene with a healthy copy of the gene, inactivating a disease-causing gene that is not functioning properly, or introducing a new or modified gene into the body to help treat a disease. The promise of gene editing approaches, including CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing—discovered in 2020 by Nobel prize winners Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna—opened the possibility of cure for many genetic disorders (Park & Bao, 2021). Gene therapy is being used in a growing number of inherited genetic conditions (e.g., hemophilia, thalassemia, sickle cell disease) and acquired diseases (e.g., leukemia). It has also opened a myriad of access, implementation, and ethical questions to be addressed.

NHGRI has outlined a strategic vision for improving human health, with bold predictions that by 2030, generating and analyzing a complete human genome sequence will be routine for any research laboratory; the biological function of every human gene will be known; features of the epigenetic landscape and transcriptional output will be routinely incorporated into predictive models; genome testing will be routine, with an individual’s complete genome sequence accessible on their smartphone; and curative gene therapies will be available to all for dozens of genetic diseases (Green et al., 2020).

The six Ps paradigm shift is occurring now, with opportunities for predictive, preemptive, and preventive care greatest early in the life course; this requires engagement and inclusion of obstetrics and pediatrics. Understanding adolescent, family, and community perspectives on how genetic data should be used (Cakici et al., 2020) and coproducing strategies will be essential for addressing acceptance and ethical and equity issues.

Cancer Identification and Treatment

Cancer treatment has also been a success story in pediatrics. Forty years ago, acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a child was a death sentence for most. Today, over 90% are cured. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy have been the mainstays of treatment (Rathore & Kadin, 2010). Immunotherapy, which uses the cells of the immune system to eliminate cancer, has revolutionized treatment of many pediatric and adult cancers. These therapies include tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy, engineered T cell receptor therapy, chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy, and natural killer cell therapy (Cancer Research Institute, n.d.). Finally, many gene therapies for cancer are on the horizon (Arjmand et al., 2020; Mulcrone, Herzog, & Xiao, 2022).

Cancer treatment is moving to a precision model of care, where treatment decisions are optimized to a patient’s tumor molecular profile (Tsimberidou et al., 2020). As the next generation of pediatric precision trials is ushered in, needs include attention to the unique factors influencing pediatric drug development and precision oncology trials for pediatric cancers (DuBois et al., 2019).

Radiation therapy has also advanced with proton beam therapy. Compared with traditional radiation therapy, proton beam therapy more precisely delivers a beam of protons to disrupt and destroy tumor cells, sparing damage to surrounding tissue, which is especially important for children. Proton therapy has been found to have fewer side effects than traditional radiation therapy (Baumann et al., 2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis found that neurocognitive outcomes were improved in pediatric brain tumor patients after treatment with proton versus photon radiation (Lassaletta et al., 2023). Ultra-high-dose millisecond FLASH proton therapy and combining proton therapy with immunotherapy are areas of active research (Mascia et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2021).

While advancements in therapy have been tremendous, advancements in diagnosis have also been exciting. Genetic technology has allowed earlier identification of risk and diagnosis of cancer cells in the bloodstream before clinical symptoms (Armakolas, Kotsari, & Koskinas, 2023). Liquid biopsies are already being used routinely to monitor cancer recurrence. As the field advances, recurrence, secondary cancers, and survivorship are growing areas of focus for pediatric and adult oncology.

While prevention is a key focus in pediatrics, preventing childhood cancer presents unique challenges. Unlike many adult cancers, most childhood cancers are not strongly linked to modifiable lifestyle or environmental factors (World Health Organization, 2021). The vast majority of childhood cancers do not have a known cause, making prevention strategies difficult to implement. However, some preventive measures can be taken, such as vaccinations against certain infections and avoiding exposure to known

carcinogens like ionizing radiation (American Cancer Society, 2024). For children with genetic predispositions, which account for approximately 10% of cases, early screening may be beneficial (American Cancer Society, 2024). Currently, the most effective approach to reducing the burden of childhood cancer focuses on early diagnosis and prompt treatment, as these factors significantly improve outcomes and survival rates (Pan American Health Organization, n.d.).

Stem Cells, Organoids, and Regenerative Medicine

Regenerative medicine engineers biologically functional tissues or organs for therapeutic testing or tissue replacement (Elisseeff, Badylak, & Boeke, 2021; Shi et al., 2017; Trounson, Boyd, & Boyd, 2019). It is now possible to take one’s blood, isolate pluripotent stem cells, and grow these cells in a petri dish into complex organoid tissue of stomach, intestine, retina, or neural tissue. This is another area of precision medicine featuring personalized cell therapy and the creation of essential platforms for targeted drug development. Enabled by Nobel prize scientist Shinya Yamanaka, a small number of genes within the genome of mice were identified that allowed a mature or specialized cell to return to an immature state, which, in turn, could grow into different types of cells within the body. This discovery of a renewable cell source of adult and induced pluripotent stem cells, which could potentially avoid immunologic rejection, has accelerated research on the creation of new organoids, microtissues, and body-on-a-chip systems in the context of immunoengineering and regenerative immunology, for basic biology discovery and clinical application. The possibility of using pluripotent stem cells to correct conditions identified in the fetus is another area of active research (Bergh, Buskmiller, & Johnson, 2021).

Advances in Vaccines and Monoclonal Antibody Development

Routine childhood immunization has been a success story in averting death and disability from disease. A recent study found that routine immunizations have led to reductions in incidence of all vaccine-targeted diseases, ranging from 17% for influenza to nearly 100% for diphtheria, Haemophilus influenzae type B, measles, mumps, polio, and rubella—equating to more than 24 million cases averted in the United States in 2019 (Talbird et al., 2022).

The continued development of vaccines will influence health care needs in the future as well. The rapid development of an effective COVID-19 vaccine was a public health success story. Many more vaccines are on the horizon that will have far-reaching impact on health and health care. RSV infection is the leading cause of pneumonia and bronchiolitis in young

children globally and is the most common cause of hospitalization among American infants (CDC, 2024i; Karron, 2023). Approved in 1998, palivizumab (Synagis), a monoclonal antibody product has protected high-risk young children from severe RSV infection. A second monoclonal antibody, nirsevimab (Beyfortus), has been recently approved for infants and offers easier administration (Hammitt et al., 2022). A new bivalent RSV vaccine has shown great promise in older adults and in infants born to women who received the vaccine (Kampmann et al., 2023; Walsh et al., 2023).

Recovering from pandemic-related childhood vaccine disruptions and addressing vaccine hesitancy will need to be priorities to maintain and further progress. For example, low vaccination rates and vaccine hesitancy have led to polio outbreaks in the past 2 years, with cases of paralysis from polio in the United States and London (Census Bureau, 2024), and measles outbreaks are becoming more common. Improving science communication is an important topic in need of further research (National Academies, 2017c). CDC estimates that vaccination of children in the United States born between 1994 and 2021 will prevent 472 million illnesses (29.8 million hospitalizations), help avoid 1,052,000 deaths, and save nearly $2.2 trillion in total societal costs (Whitney et al., 2014). Vaccines save lives and are cost-effective (see an illustration of such protection in Figure 2-5). New vaccines and monoclonal antibodies addressing current and emerging diseases will continue to transform child, youth, and societal health and health care into the future.

SOURCE: Ekaterina Kotova, age 15, Russia; © Peace Child International, used with permission.

Maternal–Fetal Health

Women’s health in preconception and prenatal health are major determinants of child health. The specialty of maternal–fetal medicine has seen profound and rapid growth and progress since its emergence in the 1960s. This field, which covers the science of the effects of women’s health on fetal health and diagnosis and treatment of maternal and fetal complications, progressed from fetal movement and heart rate monitoring to amniocentesis to ultrasound to the complex fetal medical and surgical interventions of today.

Medical or surgical fetal intervention has become standard of care for certain conditions, including the administration of maternal glucocorticoids to speed lung maturation in premature fetuses at risk for respiratory distress syndrome and in utero surgery for certain neural tube defects (ACOG, 2013; Bergh, Buskmiller, & Johnson, 2021; Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2017). Mostly under research protocols, additional interventions are being offered for fetal diseases, including structural abnormalities (e.g., myelomeningocele, renal or urologic abnormalities, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome), cardiac arrhythmias, fetal metabolic diseases, and abnormalities of the placental vessels or membranes. While many of these diseases would be lethal without treatment, some receive in utero treatment to improve child outcomes. While a beneficence-based motivation (i.e., to improve fetal and neonatal outcomes, do good, and to ameliorate suffering) guides this treatment, it raises many ethical issues surrounding maternal autonomy and decision making, child outcomes, resource utilization, and innovation versus research (ACOG, 2011).

Many areas of research discovery enhance knowledge about maternal–fetal health and disease, with the goal of optimizing pregnancy and perinatal outcomes extending to improved child and adult health outcomes (CDC, 2024l). Some of these areas are maternal–fetal immunology and the recent approval of an RSV vaccine for use in pregnant women to protect their infants, additional genetic screening and intervention, new fetal surgery targets, and the possibility of using pluripotent stem cells to correct conditions identified in the fetus (Bergh, Buskmiller, & Johnson, 2021).

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Digital Health

As in many sectors, the convergence of a number of rapidly developing technologies—such as apps, robotics, virtual reality, AI, 3D printing, and networks, among others—has the potential to revolutionize health and medicine for children and youth. Such technologies could transform the health care system from one that is predominantly a “sick care” system based on episodic, in-person, one-size-fits-all care that relies on human cognition

to a system based on continuous, virtual, personalized, and AI-enhanced care (Kraft, 2023). These technologies can enhance diagnostic accuracy, improve training and skill acquisition, support mental health, and provide continuous health monitoring (Hasan et al., 2023; Laspro et al., 2023; Pinto-Coelho, 2023; Sousa, Ferrinho, & Travassos, 2023). For example, AI-based technology systems have been used in analyzing medical images, detecting drug interactions, identifying high-risk patients, and coding medical notes (Lee, Bubeck, & Petro, 2023; Pinto-Coelho, 2023; Whitehead et al., 2024). In these examples, digital health tools and systems remove some of the “friction” in health care delivery, making certain processes more efficient and potentially freeing up providers’ time for other tasks. Augmented, extended, and virtual reality technologies are also being used for surgical navigation systems through small, wearable displays such as headsets or glasses and for engaging children to reduce anxiety and pain during medical procedures and recovery (Antonovics, Boitsios, & Saliba, 2024; Food and Drug Administration, 2023).

Wearables for patients have shifted the health landscape; individuals can not only track their blood pressure and perform urinalysis at home, but detect genetic abnormalities, and use smart pacifiers to monitor infants’ electrolyte levels in real time (Gurovich et al., 2019; Kraft, 2023). In addition, some technologies may allow for prescribing through an app health intervention instead of a traditional pharmaceutical intervention (Children’s Bureau, n.d.). For instance, apps are now available for youth mental health interventions and prescription video games can treat young people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Children’s Bureau, n.d.). While evidence supports the effectiveness of these technologies, continued research and development are necessary to fully realize their potential and address challenges such as user engagement and device reliability.

Technologies also have the potential to enhance patient and provider partnerships, especially for chronic conditions. In a study of an electronic health record–linked mHealth platform that supports patient and clinician collaboration through real-time, bidirectional data sharing, Opipari-Arrigan and colleagues (2020) found that participants using the platform reported improvement in self-efficacy and positive impacts on care, including improved visit quality, collaboration, and preparation. The authors concluded that “use of an mHealth tool to support closed feedback loops through real-time data sharing and patient-clinician collaboration is feasible and shows indications of acceptability and promise as a strategy for improving pediatric chronic illness management” (Opipari-Arrigan et al., 2020, p. 1).

The health care system could enhance care delivery for children and families by leveraging advances in AI and other digital tools, such as AI-driven applications to screen for rare genetic conditions and personalize treatment plans, thereby improving diagnostic accuracy and access

to specialized care (Children’s National Hospital, 2023a). However, it is crucial to develop and implement these technologies with a focus on equity and inclusivity, ensuring that AI algorithms and digital health solutions are designed to serve diverse populations effectively (Kan Yeung et al., 2023; Mennella et al., 2024; see also Chapter 3).

The use of telehealth has also expanded significantly in recent years, particularly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Virtual technologies—such as remote patient monitoring, telehealth for high-risk or technology-dependent patients, preprocedural evaluation, and postprocedural follow-up care—can increase practices’ quality, efficiency, and capacity (Ashwood et al., 2017; CDC, n.d.e; Ong et al., 2016). Providing asynchronous care by telehealth can improve the pediatric clinician’s time management and efficiency, reduce the need for ancillary office staff to handle real-time interaction, improve documentation of encounters, improve compensation for remote services, and meet the needs of families who are increasingly demanding care on nontraditional schedules (Curfman et al., 2022).

Telehealth may offer opportunities to transform adolescent health care specifically, as young people are spending increasing amounts of time on digital platforms. Telehealth enables adolescent care to be offered through secure chats, asynchronous visits, video visits with peripherals, and digital therapeutics, and to increase adolescents’ engagement in their health care. North (2023) posited:

Telehealth may allow an ongoing, adaptive conversation focused on adolescent wellness. For example, periodic risk behavior and mental health screening could be conducted with short, chat-based questions delivered at regular intervals. The provision of care in this manner would allow access to a private space and increase confidentiality. Responses would trigger timely, developmentally appropriate, and culturally sensitive anticipatory guidance through a secure app or an immediate video visit with a medical team member for an acute crisis. Additionally, when appropriate, parent-focused health information could be delivered immediately. (p. 3)

Research on telehealth has found positive outcomes regarding patient, parent, and provider satisfaction; feasibility; and equivalence of telehealth encounters to in-person encounters (see, e.g., Curfman, Hackell et al., 2021; Curfman, McSwain et al., 2021a; Curfman, McSwain et al., 2021b; Fleischman et al., 2016; Milne Wenderlich & Herendeen, 2021; Myers et al., 2015; Shah & Badawy, 2021). School-based telehealth programs have been shown to increase opportunities for both acute and chronic care for children and adolescents (Bian et al., 2019; Holland et al., 2021; Knopf, 2013; McConnochie et al., 2015; Reynolds & Maughan, 2015; Ronis et al., 2017), and to provide an early means of evaluation and intervention for

acutely ill patients, as well as address developmental, behavioral, and educational issues (Curfman et al., 2022; Halterman et al., 2018).

Integrating digital health tools such as telehealth platforms and mobile health apps can facilitate continuous and person-centered care, ensuring timely interventions and better health outcomes for pediatric patients (Granström et al., 2020; Oh, 2023). However, adoption and implementation of these technologies raise questions of equity, bias, and quality. Algorithmic bias is a significant concern, as combining data from adults and children can lead to age-related biases, compromising the generalizability and effectiveness of AI and machine learning models for pediatric populations (Muralidharan et al., 2023). Additionally, racial and socioeconomic disparities can be perpetuated if the data used to train these algorithms reflect historical inequities, leading to differential treatment and outcomes for minority children (Nong, 2023). The lack of digital health literacy and access among underserved populations further exacerbates these inequities, as seen in regions with high poverty and low educational attainment, where families struggle to utilize digital health tools effectively (Shimamoto, 2023). Equitable implementation of telehealth services will require inclusion of children and specific attention to under-resourced populations, appropriate training for providers and health care professionals, support for the expansion of broadband infrastructure, attention to digital literacy, and financial support to ensure all patients have equitable access to care (Curfman et al., 2022).

Precision Population and Public Health

Beyond individual precision medicine “omics” (e.g., genomics, proteomics, metabolomics), precision population and public health have advanced in identifying and addressing particular social, structural, behavioral, and environmental factors influencing health and ensuring that all benefit (Lyles et al., 2018). This includes precisely identifying specific communities and populations for focus and specific social or structural determinants to address, and using population approaches to improve health and wellbeing. Precision approaches to population health build on the science and public health interventions over the last century, which have led to an increase of 20 years in the American life expectancy at birth.

An example of a visible and successful population approach includes universal newborn metabolic screening to identify serious and treatable inherited conditions (Green et al., 2020; National Academies, 2023j). Incorporating more genetic tests and conditions into this screening will further precision population health, as will AI and big data algorithms predicting risk and response. Adolescent, family, and community engagement will address health needs and health equity more precisely. Utilizing quality

improvement methods to standardize processes; implementing structures to reduce system variation; and establishing collaborative-learning health networks to enable patients, families, clinicians, researchers, and communities to improve together offer the opportunity to achieve population outcomes at scale. This requires a shift from treating individuals with acute and chronic illnesses to also focusing on detailed and focused population management of disease and primary and secondary prevention. The potential impact of both individual precision medicine science and precision population health starting early in the life course is powerful.

The following sections further describe the science on the social, structural, and environmental influences on health; the importance of including patients, families, and communities in co-creation and co-design of solutions; and the importance of implementation and dissemination research to ensure excellent and equitable benefit (National Academies, 2023e,g,i).

Implications of Scientific and Technological Advancement for Transformation

The scientific advances outlined in this chapter reflect major successes in understanding the causes of health and wellbeing and the role of major medical advances on the prevention, elimination, and treatment of diseases. The pace of discovery is rapid as research is being translated to clinical care and public health. These discoveries have many implications for health care and health care transformation.

As change occurs, it is vital to consider proactively how to fairly distribute the benefits and risks associated with these advancements and to ensure equity and community co-design and co-creation. The evidence regarding persistent racism and inequities in child and adolescent health care call for vigilance and repair in association with the applications of the innovations noted above into practice and daily life. For example, while the possible uses of AI offer hope of efficiency and improvement, potential unintended consequences need focused attention. AI models using existing data can perpetuate inherent biases. Studies have found that AI chatbots’ responses to clinical vignettes differed based on a patient’s gender, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (Kim et al., 2023).

Adolescent, family, and community perspectives must be at the center of change with partnership in translation of science to practice. This is especially important in a time of rampant health misinformation, vaccine hesitancy, and questioning of science. Co-production and careful messaging are imperative. For example, many parent-led disease-based organizations have been influential advocates in scientific advancements and are essential partners.

In addition to equity and access issues, ethical issues abound, especially as children are a vulnerable population and controversy remains on when

life begins. For children, ethical considerations are complex, as they often lack the capacity to provide informed consent for medical procedures or research participation (Banerjee, 2020). Additional safeguards are required when conducting research with children, including assessing risks carefully and obtaining permission from parents or guardians (Canadian Pediatric Society, 2008). Furthermore, debates around the beginning of life have significant implications for issues affecting children, such as access to reproductive health services for minors and protections for pregnant adolescents (Ziegler, as cited in Simmons-Duffin, 2022) and in the conduct of maternal–fetal medicine interventions. Also, the cost of new therapies is significant, raising societal concerns on who might benefit and how to pay. The National Academies report Toward Equitable Innovation in Health and Medicine provides guidance on managing the risks, benefits, and ethical and societal implications of new technologies in health and medicine (National Academies, 2023j). Attention to the coordinated, cross-sector governance framework and recommendations in the report is vital for an innovation system that is more equitable, community engaged, and responsive to inequities as they arise, and mindful of the myriad ethical issues.

New science and technology are bound to change health care delivery in process, structure, and outcomes. A shift to more outpatient care, virtual care, and home care is likely. Children hospitalized today have greater acuity, severity, and complexity of illness compared with previous decades. Cancer therapy, which used to involve long inpatient stays, now has shifted to more outpatient care. New discoveries may facilitate additional shifts to outpatient care (e.g., FLASH proton therapy eliminating multiple radiation therapy visits, liquid biopsy enabling earlier identification of cancer), virtual care (e.g., counseling on genetic risks, mental health), and home care. This shift will likely be accompanied by a shift to multidisciplinary teams to address and preempt health risks. With great focus on health risks and attention to social determinants of health, interventions will require the assistance of social workers, genetic counselors, developmentalists, nutritionists, mental and behavioral health counselors, and community services.

It is likely that there will also be a shift to more predictive and personalized care. With earlier identification of health risks, counseling and early intervention will be important health care services. Primary and specialty care will increasingly incorporate more screening and AI-based digital prediction tools. Genomic and digital prediction tools will facilitate more personalized care, including pharmacogenomic tailoring of therapeutics and risk assessment based on multisource data specific to an individual child or family.

Maternal–child health is at the forefront of many exciting advances. Subsequent chapters discuss considerations of these areas of progress on health transformation.

The transformed child health care system will need to address several key ethical and equity issues arising from scientific advances, to avoid perpetuating or exacerbating existing disparities. These include algorithmic bias in AI and machine learning systems, differential access to expensive new therapies, privacy concerns with increased data collection, and potential misuse of genetic technologies, among others (Abràmoff et al., 2024; Jeyaraman et al., 2023; Ndugga, Pillai, & Artiga, 2024). To mitigate these risks, safeguards—such as rigorous testing of algorithms for bias, innovative financing models to improve access to high-cost treatments, and robust data privacy protections—are needed, as are ethical frameworks to guide the responsible development and use of new technologies (Chin et al., 2023; Tilala et al., 2024; Turner Lee, Resnick, & Barton, 2019). Additionally, the system needs to actively work to ensure that scientific advances benefit all children equitably by engaging diverse stakeholders, addressing social determinants of health, and improving diversity in the health care workforce (National Academies, 2023e). Ongoing collaboration between health care providers, researchers, policy makers, ethicists, and communities will be crucial to navigate the complex ethical terrain as technologies continue to evolve.

SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCES ON CHILD HEALTH AT COMMUNITY AND INDIVIDUAL LEVELS

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’s Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP, n.d.a) defines the “social determinants of health” as “the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks” (para. 1). These are grouped into five domains: economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context (ODPHP, n.d.b). The importance of these domains for child health is well established. For instance, poor living conditions and housing instability affect children’s health detrimentally and increase mortality, even after controlling for socioeconomic status (Anderst et al., 2022).

Experiences across environmental contexts play a significant role in child and youth development. Vibrant and Healthy Kids provides a conceptual model and environmental context for understanding development across life stages (see Figure 2-6; National Academies, 2019d). The diagram’s nested circles illustrate the complex sociocultural environment that shapes development at the individual level. Individual social and biological mechanisms and culture operate and interact within and across the three levels.

Structural inequities operate at the outermost level of socioeconomic and political drivers. As summarized in Vibrant and Healthy Kids, “Structural

SOURCE: National Academies, 2019d.

inequities are deeply embedded in policies, laws, governance, and culture; they result in the differential distribution of power and resources across individual and group characteristics (including race, ethnicity, sex, gender identity, class, sexual orientation, and gender expression)” (National Academies, 2019d, p. 57). The next level, second from the outermost circle, represents social, economic, cultural, and environmental states (i.e., the social determinants of health). The third level represents the factors that most directly and proximally shape children’s daily experiences, routine patterns, and access to resources: family cohesion, social connections, and caregiver wellbeing. Both developmental risk and protective factors can be transferred intergenerationally. In sum, long-term psychological, behavioral, and physical health is shaped by biological and environmental factors and social context, and their interactions, before conception and throughout the life course.

Structural Inequities and Racism

The various forms of racism so prevalent in the United States have profound effects on child and adolescent health care outcomes. Racism is a system of exclusion and oppression based largely on physical appearances.

Jones (2000) described it as the application of power against a group for the advantage of the oppressor group (see also Jones et al., 2009). Elsewhere, it has been equated with an American caste system, whether manifested as slavery, Jim Crow laws, or mass incarceration. “Race,” the underpinning for racism, is not a biological construct but a social one, and its implementation varies widely within and across countries (Wilkerson, 2020). Race was not derived from genetics or biology but for social and political reasons, and racism has led to significant inequities (National Academies, 2023d). Racism was foundational to the formation of the U.S. economy and contributed to American economic growth and expansion over the centuries through the exploitation of inexpensive labor. It continues to have a pervasive hold over many U.S. communities with large numbers of children, adolescents, and adults experiencing racism daily.

The several types of racism include (but are not limited to) systemic or structural racism, interpersonal racism, cultural racism, and internalized racism (National Academies, 2023d). “Systemic” or “structural racism” is oppression embedded in regulation, law, institutions, and even communities over time that limit opportunities or punish certain marginalized persons disproportionately. “Institutional racism,” a concept within systemic racism, arises when the system provides inconsistent access to opportunities and services, based on race and where groups differ in their power and influence, via policies that have been normalized and legalized (Jones, 2000), marginalizing groups and providing different access to housing, education, employment, and health care. “Interpersonal racism” includes direct forms of aggression or oppression between individuals. Sometimes referred to as personally mediated racisms, interpersonal racism is discrimination and prejudice, or what most people consider when the term “racism” is mentioned (Jones, 2000). Concepts within interpersonal racism include micro-aggressions and cyber-racism. “Cultural racism” is the broad acceptance of cultural attributes as more attractive or desirous in media, communications, and public spaces (Cogburn, 2019). “Internalized racism” refers to when individuals from historically marginalized groups accept the negative message that they are inferior, substandard, or lack potential, or otherwise underestimate their worth and value (Jones, 2000).

Racism appears to act as a chronic stressor that increases allostatic load at key developmental stages, including prior to and during the prenatal periods, such that effects are seen as early as birth and worsen over time. Allostatic load maintains a high state of stress and hypervigilance in the body and mind. Although it is adaptive in some environments, when confronted with frequent challenges, stress system activation becomes chronic, resulting in ongoing inflammation, increased chronic illnesses, and premature mortality. Because of its chronic nature, racism can have a “weathering effect” (Forde et al., 2019; Geronimus, 1996), increasing biological age faster than

chronological age as measured by telomere shortening, methylation, and related assays, and likely increasing susceptibility to chronic diseases such as cancer and heart disease.

More than two decades ago, the landmark IOM (2003b) report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care raised awareness of and reviewed the literature on the health effects of racism. Of the 103 studies reviewed in Unequal Treatment, only five focused on disparities for children, even though it is known that that disparities early in life can have lifelong impact (Cheng & Jenkins, 2009).

More than 20 years after Unequal Treatment was published, disparities remain persistent and pervasive, as seen recently during the COVID-19 pandemic, when some racial groups experienced higher rates of infection, hospitalization, and death than others. Today there is much literature on maternal, child, and adolescent health inequities, including a sentinel review by the American Academy of Pediatrics, The Impact of Racism on Child and Adolescent Health (Trent, Dooley, & Dougé, 2019). Racism continues to have devastating effects on child and adolescent health, especially for conditions that have substantial associations with social and economic influences, such as prematurity, emotional and behavioral disorders, asthma, and obesity (Trent, Dooley, & Dougé, 2019). These conditions all show marked gradients in outcomes among diverse groups of children, with consistently poorer outcomes for historically marginalized youth. For example, institutional racism is associated with infant morbidity and mortality, as well as asthma mortality, specifically in the Black population (Fanta, Ladzekpo, & Unaka, 2021).

Residential racial segregation is a fundamental cause of racial and ethnic health disparities (Williams & Collins, 2001). Babies born to mothers who lived in very segregated areas are shown to have higher rates of intraventricular hemorrhage (Murosko, Passerella, & Lorch, 2020). Pabayo and colleagues (2019) measured proportions of Black versus White individuals in each state around employment, criminal justice, and voting and legislative representation as indicators of racism. These disparities were associated with infant mortality—Black infants had increased odds of mortality compared with White infants in states with increased levels of racism (Pabayo et al., 2019). A review of California Census tract data showed that children with asthma living in communities severely affected by historical redlining were predominantly non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic, living in poverty, and living in neighborhoods with higher diesel exhaust particle emissions (Nardone et al., 2020). These children also had higher rates of emergency department visits due to asthma exacerbations (Nardone et al., 2020).

Racism affects pediatric health care institutions, often exacerbating child and adolescent experiences of racism in other contexts. Health care institutions expose patients and families to interpersonal and structural

racism throughout the care process, resulting in more expensive care and poorer patient outcomes. Racism affects which patients are accepted for appointments (as shown in secret shopper studies) or how long it takes to get appointments, the location of specialty resources in pediatrics, the types of diagnoses that are offered, and the types of treatments provided (National Academies, 2023d; Rankin et al., 2022). For example, in behavioral health, specialists are less likely to accept racially or ethnically marginalized children and adolescents as patients; racially or ethnically marginalized children wait longer to get appointments, have different rates of diagnoses such as externalizing disorders, and are more likely than their White peers to be prescribed antipsychotics rather than antidepressants (Hoffmann et al., 2022; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015). Similarly, Black children with appendicitis presenting to the emergency department with moderate pain were less likely than White children to receive pain medication. With severe pain, Black children were less likely than White children to receive opioid medication (Goyal et al., 2015). In a study by Wakefield and colleagues (2018), all Black youth with sickle cell disease reported experiencing bias in a community setting, and some also in a medical or health setting. A study of fifth-grade children documented an association between discrimination and developing symptoms of depression, ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder (Coker et al., 2009). In short, the process of receiving health care can worsen existing racial disparities for children and adolescents.

Internalized racism may also impact child and family health. Children as young as age 3 years can recognize racial differences and begin categorizing people by race (Hilario et al., 2023). For example, in a study, Black and White children as young as age 3 years assigned different characteristics to a White doll and a Black doll, preferring to play with the White doll, while assigning negative characteristics to the Black doll and preferring not to play with it. Black children became “emotionally upset at having to identify with the doll that they had rejected” (Jordan & Hernandez-Reif, 2009, video interview, timestamp 5:55; see also Clark & Clark, 1939). Subsequent research explains that children’s racial awareness emerges early in their lifetimes. By ages 4–5, many children have already developed racial biases and stereotypes influenced by their environment and experiences (Hilario et al., 2023). This early racial awareness means children of color may internalize negative stereotypes and racism from a young age, impacting their self-esteem and mental health (Byrd et al., 2017; Hilario et al., 2023; Pachter & García Coll, 2009; Sullivan, Wilton, & Apfelbaum, 2020).

The inequities around identifying and managing autism in Black children provide one example of racism in pediatric health. Black children have an average age of autism diagnosis of 64.9 months, more than 3 years on average after parents stated their initial concerns (Constantino et al., 2020).

This study called for increasing participation of non-White children in research, especially in efforts to address the adverse impact of racism in autism care—namely, policies that adversely affect access to evaluations and interventions, including suboptimal payment and the lack of a diverse and culturally humble workforce conducting the evaluations, potentially exacerbating the bias clinicians have and discrimination families experience (Broder-Fingert, Mateo, & Zuckerman, 2020):

Finally, any study of racial inequity warrants discussion of racism and racial injustice in the United States, including the long-standing, complex system of oppression and exclusion that allocates and concentrates unfair advantage to white communities and disadvantages to multiracial communities (para. 6).

Hispanic children face significant health care disparities compared with their White, non-Hispanic counterparts in various aspects of medical care. Hispanic children are less likely to have health insurance coverage and a usual source of care, which can lead to reduced access to preventive services and regular checkups (Escarce & Kapur, 2006; Funk & Lopez, 2022). They also experience longer wait times in emergency rooms and are less likely to receive adequate pain management for conditions such as broken bones, appendicitis, and migraines (Samuelson, 2024). Hispanic children with special health care needs receive fewer specialist services than their White peers, and they are less likely to be diagnosed with developmental disabilities before preschool or kindergarten (Samuelson, 2024). In end-of-life care, Hispanic children are more likely to die in the hospital and receive medically intense care during their final days compared with White children (Samuelson, 2024).

Changes to well-child visits present a unique opportunity to better address racism, poverty, and nutritional and environmental influences on child health. Examples include the implementation of an antiracist framework with comprehensive screening for social determinants of health and implicit bias training for health care providers (Pachter & García Coll, 2009; Pyone et al., 2021). Systematic screening for financial strain, food insecurity, and housing instability could be incorporated, along with referrals to community resources and social services (Garg et al., 2023). Additionally, detailed assessments of nutritional status and environmental exposures could be conducted, with pediatric clinicians advocating for policies to improve neighborhood conditions and collaborating with local organizations to provide families with resources. These changes have the potential to foster trust, mitigate health care disparities, alleviate poverty-related stressors, and ensure children grow up in environments conducive to their overall health and wellbeing (Pachter & García Coll, 2009; Pyone et al., 2021).

Childhood Poverty

Childhood poverty remains the strongest predictor of child health, wellbeing, and poor health outcomes (Council on Community Pediatrics et al., 2016). Children whose families live in poverty experience worse health early in life than children growing up in higher-income families, and this disparity worsens as they age (National Academies, 2023c,g). Childhood poverty significantly impacts life course health and wellbeing by increasing the risk of chronic health conditions, such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases, which can persist into adulthood (National Academies, 2019a). The stress and deprivation experienced in an impoverished childhood can lead to long-term psychological and emotional challenges, influencing mental health outcomes throughout life. Additionally, limited access to quality health care, nutritious food, and educational opportunities further exacerbates the cycle of poverty and its detrimental effects on overall wellbeing across the lifespan.

The intersectionality of poverty and racism creates compounded challenges for minoritized children in accessing and receiving quality health care. Research shows that children from racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely to live in poverty, and this combination of factors leads to worse health outcomes and disparities in care (National Academies, 2019a, 2023g). Poverty limits access to resources, nutritious food, safe housing, and quality education—all social determinants that impact health (National Academies, 2019a, 2023g). At the same time, systemic racism in health care and other institutions creates additional barriers through discrimination, implicit bias, and unequal treatment (Beech et al., 2021; Castro-Ramirez et al., 2021; Cheng, Goodman, & Committee on Pediatric Research, 2015). For minoritized children, this intersection means they are more likely to lack health insurance, receive lower-quality care when they do access services, and experience the cumulative health effects of chronic stress from both poverty and racism (National Academies, 2017a; Slopen et al., 2024). The cognitive burden of dealing with resource scarcity and racial discrimination also takes a toll, leaving families with less bandwidth to navigate complex health care systems (National Academies, 2017a; Paradies et al., 2015; Slopen et al., 2024). Ultimately, this intersectionality perpetuates a cycle where poverty and racism reinforce each other, leading to persistent health disparities for minoritized children that can have lifelong impacts (Beech et al., 2021; Castro-Ramirez et al., 2021).

Two recent National Academies reports (2019a, 2023g) identified ways to reduce childhood poverty in the United States and to decrease intergenerational poverty among U.S. households. The latter report, Reducing Intergenerational Poverty (National Academies, 2023g), specified the value of health insurance coverage—through Medicaid—as one factor that can

diminish poverty. The committee recognizes the fundamental importance of addressing childhood poverty to improve the health and wellbeing of U.S. children and youth, and supports the recommendations of those two key reports.

Healthy Living Conditions