Launching Lifelong Health by Improving Health Care for Children, Youth, and Families (2024)

Chapter: 8 Opportunities for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention in Schools

8

Opportunities for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention in Schools

[There’s] need for a robust school-based health center network to provide basic access to preventive services. Children in inner cities and poor rural areas might not have [. . .] access to a doctor.

—Comment to committee from health care consultant, Queens, New York

Schools are an opportune setting in which to advance child and adolescent health because children spend so much of their time there. They provide a central focus and experience for children and youth—unlike any set of institutions for other age groups. By offering services in schools, the health care system can meet children, youth, and families where they are, reducing burdens many families face when navigating inequities in geographic or financial access to health care providers and care. Some schools provide substantial amounts of preventive health and treatment services for children and youth, including health and socioemotional education programs, school nursing, school-based health centers, and various counseling and mental health prevention and treatment programs. In addition, 94% of public and private schools participate in national school breakfast and lunch programs and provide nutritious meals to nearly 30 million children in the United States (U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2023b). Schools may also assist in outreach and enrollment of eligible children in public health insurance and income support programs.

In some schools, health care has been delivered in a universal manner to all children and in a targeted manner to those who have been identified by teachers, school nurses, and counselors as being at risk. Teachers may deliver

curricular content around socioemotional wellness, physical fitness, nutrition, reproductive health, and substance abuse prevention. School nurses may address acute illnesses and injuries, provide medication management, implement and advance public health campaigns, and coordinate health care with families and health care professionals. And counselors (depending on the type) may deliver individualized mental health counseling, support socioemotional wellbeing through class lessons, and assist in mental health crisis response. School-based health centers may provide preventive, reproductive, and mental health care (Allison et al., 2007; Juszczak, Melinkovich, & Kaplan, 2003; School-Based Health Alliance [SBHA], 2014). The availability of these services varies greatly across schools.

Evidence shows that when schools adopt or offer these opportunities, both health and education outcomes can be improved and disparities narrowed (Community Preventive Services Task Force, 2016a,b; Connor et al., 2024; Koening et al., 2018; Ran, Chattopadhyay, & Hahn, 2016). The committee sees great promise in leveraging schools and other community resources to expand their provision of critical prevention and promotion services for young children; preparation for adolescence and learning healthy living and sexuality; substance abuse prevention; and management of low-severity acute illnesses and comanagement of chronic conditions, such as asthma, diabetes mellitus, anxiety, and depression. Furthermore, teachers and coaches are present in children’s day-to-day lives and, if supported, can provide essential safe, stable relationships for children and youth with adults.

This chapter highlights the important bidirectional connections between education and health and highlights the existing role of schools in children’s health. It concludes with opportunities for augmenting this role to strengthen the provision of services in schools to promote improved health and wellbeing.

CONNECTIONS BETWEEN EDUCATION AND HEALTH

Schools offer more than education. In partnership with health care and other sectors, schools seek to help children prepare to enter adulthood; to create a healthy and productive life; and to optimize their potential to meet their economic and social needs, maintain and improve their own health, and contribute to the workplace and the community. Health outcomes and educational achievement have shown to be correlated in a number of ways in the literature. Healthier students are better, more engaged learners (Basch, 2011). Educational achievement is tied to improved long-term health and economic productivity; the measure of years of completed schooling has a strong causal connection with higher earnings and other important measures of life success and wellbeing, and thus with economic mobility in adulthood (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National

Academies], 2023g). Conversely, low academic achievement is strongly associated with risk-taking behavior, compromised health status, and reduced longevity (Braveman, Ergerter, & Williams, 2011; Lande et al., 2003).1

However, in the United States, research shows that just 42% of children between the ages of 3 and 5 years are considered to be “healthy and ready to learn” across four domains, suggesting that most children are at risk and in need of additional supports (Ghandour et al., 2021). A range of factors impacts school-readiness results, including parent mental health status, adverse childhood experiences, and access to neighborhood amenities such as parks and libraries. Additionally, children exposed to adverse childhood experiences (39% of children ages 0–17 years) are substantially and significantly more likely to fail to be ready for school, miss 2 or more weeks of school in a year, repeat a grade in school, and lack resilience (Jackson, Testa, & Vaughn, 2021; Lipscomb et al., 2021). School absenteeism has worsened markedly since the pandemic, with an increase of chronic absenteeism (defined as missing 10% of the school year), from 15% before the pandemic to an estimated 26% of public students in most recent data (Mervosh & Paris, 2024). In high-poverty districts chronic absenteeism was 19% prepandemic, soaring to 36% more recently (Return2Learn Tracker, 2023).

Illness and chronic physical and mental health conditions are common causes of school absenteeism, influencing academic success (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2021a, 2024e). Children from low-income and racially or ethnically marginalized populations in the United States are more likely to develop chronic health problems than are more affluent and non-Hispanic White children and less likely to have a usual source of medical care (Bloom, Cohen, & Freeman, 2012). Children suffering from chronic conditions may have a harder time attending and completing school, and asthma and other chronic health conditions have been linked to lower academic achievement (Agnafors, Barmark, & Sydsjö, 2021; Basch, 2011; McLeod, Uemura, & Rohrman, 2012). For example, between 2018 and 2020, a median of 37.3% of children missed days of school because of their asthma, ranging from 26.6% in New Hampshire to 53.6% of children in New York (CDC, 2023a, 2024b). One study found that student-reported and school-based health center–recorded asthma explained 14–18% of student absenteeism, even after accounting for other health and social risks (Johnson et al., 2019).

Opportunities for supporting the wellbeing of children and youth in school in collaboration with the health care system and other sectors are missed too often. The American Academy of Pediatrics has suggested opportunities for pediatric professionals to identify children who have been

___________________

1 It is important to note that deleterious health outcomes in schools are correlated with exclusionary disciplinary practices, including expulsion and suspension (Eyllon et al., 2022).

absent and to promote school attendance and address causes of chronic absenteeism (Allison & Attisha, 2019). Interventions that may contribute to school completion, such as services and programs to address mental health, substance use, violence, pregnancy, and school climate, also have evidence for improving health outcomes (Freudenberg & Ruglis, 2007). Moreover, students who drop out of school are not able to benefit from services such as school-based health centers, which have documented benefits including reducing health care costs (Ran, Chattopadhyay, & Hahn, 2016).

Continued and additional partnerships between health and education sectors can help to address these gaps and opportunities for children. Existing recommendations in the field call for implementing evidence-based strategies for promoting family resilience and parent–child connection and for building child and youth resilience, socioemotional capabilities, and children’s capacity to persist in learning and achieving goals.

Moreover, given the relationship between health and education and the promise of schools as contributing to child health and wellbeing, indicators of school readiness can be used to reflect the health of young children (Ghandour et al., 2018) and as a measure of the performance of the children’s health care system in the United States. The National Academy of Medicine’s Perspectives paper Vital Signs for Pediatric Health (Kaminski et al., 2023) calls for using measures such as school readiness, high school graduation rates, and rates of school absenteeism as child health care system performance measures, intended to be achieved jointly in collaboration with families, schools, and the community (see also Johnson et al., 2019).

THE ROLE OF SCHOOLS IN CHILDREN’S HEALTH CARE

Schools play important roles in influencing the health of students and their parents, and sometimes even the surrounding community. They can facilitate public health insurance enrollment, provide nutrition and assist in combatting child hunger, and manage chronic conditions and promote health (CDC, 2021b, 2024e; Fabina, Hernandez, & McElrath, 2023). This section briefly describes each of these roles.2 Delivery of care through school-based health centers and mental health services is discussed in subsequent sections.

Facilitating Public Insurance Enrollment

As discussed in Chapter 6, improving access to insurance and reducing churn in enrollment is an effective way to promote child health. Children with insurance not only have better access to care but also have better

___________________

2 The sections that follow largely refer to public schools in the United States. Approximately 80% of U.S. children attended public elementary or secondary schools in 2021 (Fabina, Hernandez, & McElrath, 2023).

health outcomes, as discussed in Chapter 4. Enrolling eligible students in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) not only improves their health, enabling them to do better in school, but can have positive budgetary implications for schools.

State health officials can coordinate with school administrators and nurses to enroll eligible children in these programs. Connecticut’s health insurance exchange, for example, partners with the state’s departments of Social Services and Education to identify uninsured students in the public school system and conduct targeted outreach to their families. Florida’s KidCare builds and maintains partnerships with school nurses and administrators to disseminate information about CHIP to the parents of potentially eligible children. North Carolina, Virginia, Arkansas, Massachusetts, and Missouri have similar programs, partnering directly with school nurses, and Wyoming engages school counselors and psychologists to assist in monitoring insurance status and conducting CHIP outreach (National Academy for State Health Policy, 2019). The federal government can match state and local expenditures for administrative activities, including outreach and enrollment (Tsai, 2022).

Recent federal efforts aim to reduce churn in Medicaid and CHIP programs. Effective January 1, 2024, Congress enacted a federal requirement for 12-month continuous enrollment for all children enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP (previously had only been a state option). Several states have also sought Section 1115 waiver authority to provide additional continuous enrollment protections for Medicaid and CHIP enrollees, particularly for children (Mann & Daugherty, 2023).

Improving Access to Nutrition and Combatting Child Hunger

Given the prevalence of food insecurity in households across the country, especially in those with children, school meals can be an important setting for positive interventions to address child hunger (National Academies, 2023g).3 Food insecurity during childhood is associated with worse physical health (Gundersen & Kreider, 2009; Thomas, Miller, & Morrissey, 2019) and mental health (McIntyre et al., 2013), lower academic achievement in childhood (Jyoti, Frongillo, & Jones, 2005), and worse psychological distress and physical health during adulthood (Fertig, 2019). School meals (including breakfast, lunch, and snacks) help combat child hunger and can encourage healthy eating (CDC, 2024c; Ralston et al., 2008).

___________________

3 “Food insecurity” is defined as “a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food” and is monitored with regular household surveys (USDA, 2022). Although household food insecurity has fallen for all groups over time, children in poverty are still twice as likely (28% vs. 14%) to live in a household that has experienced food insecurity. As compared with White children, Black children are 3.5 times more likely and Latino children almost 3 times more likely to live in a household that has experienced food insecurity (National Academies, 2023g).

USDA administers the National School Lunch Program (NSLP), the School Breakfast Program (SBP), and the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) through state agencies that operate with agreements with school authorities.4

National School Lunch Program

The NSLP is a federally assisted meal program operating in public and nonprofit private schools and residential child care institutions; it provides nutritionally balanced, low-cost or free lunches to children each school day.5 The NLSP offers free lunch for children in families living below 130% of the federal poverty level (FPL) and reduced-cost lunch to children whose families live between 130% and 185% of the FPL. In fiscal year (FY) 2022, the program provided 4.95 billion free or reduced-priced lunches to school children, serving roughly 30.1 million students; 94% of schools, both public and private, chose to participate in the program (NSLP, 2024). Children may be eligible for NSLP if their families also participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or based on their status as a homeless, migrant, runaway, or foster child (Food Research & Action Center, n.d.a,b). They can also qualify on the basis of household income, Medicaid eligibility, and family size (Food Research & Action Center, n.d.b; Office of the State Superintendent of Education, n.d.). Students from ethnically marginalized groups participate in NSLP at slightly higher levels than White students, and students from low-income households participate at higher rates than those from higher-income households (Ralston et al., 2008).

Children receiving free or reduced-price NSLP lunches consume fewer “empty calories” and more fiber, milk, fruit, and vegetables compared with income-eligible nonparticipants. They also are more likely to have adequate average intakes of calcium, vitamin A, and zinc. In addition, the NSLP is associated with lower rates of food insecurity among households with children (Ralston & Coleman-Jensen, 2017).

___________________

4 The Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) also provides free meals to children, typically in congregate settings, when school is not in session (e.g., the summer months or unanticipated school closures during the school year) in areas where at least 50% of children qualify for free or reduced-price school meals. According to Toossi and Jones (2024): the number of meals served through SFSP, total spending on the program, and program participation were lower in FY 2023 compared with FY 2022. Participation in SFSP was 2.2 million in July 2023 (the month when participation in the program typically peaks), 20.3 percent less than in July 2022, when SFSP sites were able to be located in all areas and to serve meals for consumption in non-congregate settings. Participation was also 19.1 percent less than in July 2019, before the pandemic. Throughout FY 2023, the program served 136.1 million meals at a cost of $546.6 million. These figures were 9.8 percent and 8.9 percent lower, respectively, than the previous year. (p. 15)

School Breakfast Program

The SBP provides reimbursement to states to operate nonprofit breakfast programs in schools and residential child care institutions.6 The Food and Nutrition Service administers the SBP at the federal level. State education agencies administer the SBP, and local school food authorities operate the program in schools (USDA, 2023b). Utilization of the SBP is notably lower than that of the NSLP. In 2019–2020, only 58% of students who used the NSLP also received school breakfast. This has been attributed to barriers such as stigma and a lack of clarity on eligibility among parents or outreach to eligible students and caregivers (Hecht et al., 2023).

Universal Free Meals Policies

Increasingly, states are passing laws providing universal free lunches in school to all students regardless of income level or eligibility. As of 2023, eight states7 have passed Healthy School Meals for All policies (Bylander, 2023). Other states have temporary policies in place or have introduced similar bills. One of the biggest benefits of these universal programs are that more students participate in school lunch, which decreases stigma and ensures all students are satiated and ready to learn (Bylander, 2023).

Moreover, the Community Eligibility Provision of the NSLP allows schools that are serving more than 25% (40% prior to October 26, 2023) of students to be directly certified to receive free school meals through their participation in select other means-tested programs; these schools may also provide free meals to all students (Toossi & Jones, 2024).8 In a systematic review, universal free school meals (breakfast and lunch) were shown to improve diet and academic performance and decrease food insecurity, and showed no negative impacts on body mass index. These outcomes were found in students from both low- and high-income households (Cohen et al., 2021).

Child and Adult Care Food Program

CACFP, also operated through USDA, offers meals and snacks to eligible children and adults who are enrolled for care at participating child care centers, day care homes, and adult day care centers. CACFP also provides reimbursements for meals served to children and youth participating in afterschool care programs, children residing in emergency shelters, and adults over age 60 or living with a disability and enrolled in day care facilities.9

___________________

6 See https://www.fns.usda.gov/sbp/school-breakfast-program

7 California, Maine, Colorado, Minnesota, New Mexico, Vermont, Michigan, and Massachusetts.

In FY 2019 (before the COVID-19 pandemic), approximately 4.7 million children and about 137,000 adults received CACFP meals and snacks on an average day. In that year, the program served a total of about 2.1 billion meals at a cost of $3.7 billion. In FY 2020, these figures dropped to approximately 4.3 million child and adult participants daily, and nearly 1.6 billion total meals served, with total program expenditures amounting to $2.8 billion. However, in 2021 and 2022, program participation, total meals served, and expenditures rebounded to prepandemic levels, with daily participation among children and adults reaching more than 4.6 million, 1.9 billion meals served, and costs hovering around $3.8 billion annually. In FY 2023, CACFP served 1.7 billion meals, 8.9% less than in FY 2022, although spending on the program was $3.9 billion, about the same as in FY 2022. Although fewer meals were served through this program in FY 2023 compared with FY 2022, the federal reimbursement rate for each meal served was higher in FY 2023 than in FY 2022 (Economic Research Service [ERS], 2023a; Toossi & Jones, 2024).

ERS (2023a) found evidence that participation in CACFP by child care providers improves food security for households with children enrolled in the centers; it also found that participation improves consumption of milk and vegetables (State of Childhood Obesity, n.d.).

Health Promotion and Screening

Schools have direct contact with more than 94% of school-aged children, making schools a crucial setting for assessment of health needs through screening and health promotion programs.10 For example, CDC’s Healthy Schools initiative provides funding for programs that improve nutrition, enhance physical activity and physical education, and help students manage chronic conditions. These programs are implemented through partnership with nongovernmental organizations, state education agencies, school administrators and staff, and parents (CDC, 2024e). In addition to delivering preventive services, this funding has been used to support data collection and health surveillance through the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System and School Health Profiles.11 (Box 8-1 provides more detailed information about the CDC Healthy Schools initiative.) This section describes some common school-based screening and health promotion programs. Mental health promotion and school climate interventions are addressed later in the chapter.

___________________

10 The National Home Education Research Institute estimates that approximately 6% of U.S. children were homeschooled in school year 2021–2022 (Ray, 2024).

BOX 8-1

CDC Healthy Schools Initiative

CDC’s Healthy Schools initiative works with states, school systems, communities, and nonprofit organizations to prevent chronic disease and promote the health and wellbeing of children and adolescents in schools. The initiative is built on the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) framework. The WSCC is student centered and emphasizes the role of the community in supporting the school and the importance of evidence-based policies and practices. CDC Healthy Schools aims to promote healthier nutrition options and education, comprehensive physical activity programs and physical education, improved processes and better training to help students manage chronic conditions, health education that instills lifelong healthy habits and health literacy, and practices that improve school health services and links to clinical and community resources.

According to CDC Healthy Schools (n.d.d):

Healthy Schools supports 20 cooperative agreement recipients in the implementation and evaluation of evidenced-based efforts to promote the health and well-being of school-age children and adolescents in underserved and disproportionately affected communities. Cooperative agreement recipients include state education and health agencies, universities, and a tribal nation. CDC provides them with technical assistance and develops specialized tools, recommendations, and resources to help in the work they do for school health. (para. 1)

SOURCE: CDC Healthy Schools, n.d.d. See: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/about.htm

Health Screening Programs

Many states mandate school health screenings by law; these most commonly include hearing and vision, but may also include screening of dentition, blood pressure, scoliosis, height and weight, and mental health. Screening identifies potential issues in need of follow-up, requiring coordination with health organizations. These screenings are often conducted by school personnel, including school nurses, or in partnership with health organizations. For example, the Vision to Learn program partners with school districts through memoranda of understanding, seeking to identify students with vision problems and connect them with the glasses they need to participate in school effectively. In FY 2022–2023, Vision to Learn provided approximately 2.6 million children with vision screenings, 491,000 children with eye exams, and 400,000 children with glasses. The program operates in 288 school districts in 15 states and Washington, DC (Vision to Learn, 2023).

Uncorrected vision issues can lead to poor focus and other issues, such as headaches and eye pain. But accessing vision services can be challenging for many families, so providing the resource children need in school settings

not only removes the burden from the family but also reduces stigma and results in students doing better in school. Research has demonstrated that students who receive eyeglasses through school-based vision program have improved academic outcomes (Neitzel et al., 2021). While Vision to Learn receives most of its funding from private sources, it is working with Medicaid and CHIP to ensure that all children who need glasses can get them, regardless of income (Vision to Learn, 2022).

Physical Activity and Nutrition Education

Research shows that physical activity has a host of positive physical and mental health benefits for youth, such as reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety and improving mood (National Research Council [NRC] & Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2013); it also indicates a positive association between physical activity and academic achievement for adolescents (Esteban-Cornejo et al., 2015; Kristjánsson, Sigfúsdóttir, & Allegrante, 2010; NRC & IOM, 2013; Rasberry et al., 2011). Physical activity in youth has also been associated with positive psychosocial traits, including self-efficacy, self-concept and self-worth, social behaviors, and goal orientation (NRC & IOM, 2013).

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends 60 minutes or more of physical activity per day every day of the week. However, less than one-quarter (24%) of children aged 6–17 years participate in 60 minutes of physical activity every day. In a study conducted in 2017, only 26.1% of high school students participated in at least 60 minutes per day of physical activity on all 7 days of the previous week, only 51.7% of high school students attended physical education classes in an average week, and only 29.9% of high school students attending physical education classes daily (Carlson et al., 2013; CDC, 2011; Subcommittee of the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports, and Nutrition, 2012).

The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans Midcourse Report Subcommittee of the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports, and Nutrition (2012) found evidence that multicomponent physical activity interventions in schools can increase physical activity during school hours. These interventions typically combine enhanced physical education with other strategies such as health education, classroom physical activity, social marketing initiatives, active transportation to school, and physical environment improvements, among others. When combined with community- and family-based interventions, they also show strong evidence of increasing physical activity for adolescents outside of school (Subcommittee of the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports, and Nutrition, 2012).

Interventions for increasing active travel to school, especially the Safe Routes to School program, increase the proportion of students who walk or bicycle to school and decrease traffic-related injuries around school

neighborhoods (Community Preventive Services Task Force, 2021). While there is not a comprehensive inventory of Safe Routes to School programs in the United States, the 2019 National Assessment Program Report identified over 400 programs in 44 states and Washington, DC (Zimmerman & Lieberman, 2020).

Healthy nutrition is also essential. Some schools have addressed healthy weight through educational curricula and cooking classes for students and families, healthy school meals, and screening programs for identifying students at risk.

Managing Asthma and Other Chronic Conditions

Certain conditions, including asthma, obesity, food allergies, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), may require primary care practices to coordinate care with schools and will require ongoing monitoring of students during the school day. Students need to be healthy and safe to be ready to learn.

There are missed opportunities to improve asthma care within the context of the child’s community settings, including schools (Yee, Fagnano, & Halterman, 2013). Multifaceted interventions in community settings—including provider and caregiver prompts (Goldstein et al., 2018; Halterman et al., 2018), use of school nurses or community health workers to provide education and care coordination (Jonas, Leu, & Reznik, 2020; Taras et al., 2004), and mitigation of environmental triggers and other social determinants—have been effective in improving asthma preventive care and outcomes (Federico et al., 2020; Matsui, Abramson, & Sandel, 2016). School-based asthma self-management interventions for children and adolescents reduce asthma-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations and increase self-reported asthma-related quality of life (Community Preventive Services Task Force, 2019a; Hollenbach, Simoneau, & Halterman, 2022). For example, a school-based asthma management program calls for facilitating communication among the child, family, clinicians, and school nurses; creating an asthma management plan for the school setting; and assessing the school environment and remediating school-based asthma triggers (Lemanske et al., 2016). Other programs that ensure children have their asthma medications and administer controller medications at schools have been effective in reducing asthma exacerbations and increasing school attendance (Hollenbach, Simoneau, & Halterman, 2022).

Children with Disabilities

As noted in Chapter 4, an estimated 13.9 million children under age 18 years (19%) in the United States have a special health care need (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2023c). These children are more

likely to live in low-income neighborhoods and rely more on public health insurance; over half also have a co-occurring behavioral or mental health diagnosis, such as ADHD or anxiety (Kids Count Data Center, 2023a). Within this population, about 85% of children are not receiving the health care needed, mainly because of cost (despite having public health insurance, which is often inadequate) and access (e.g., lack of available appointments to address their disability; Kids Count Data Center, 2023a).

Schools provide educational programs and services for children with disabilities, guided by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004), Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (1973), and Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990). The IDEA mandates that children with disabilities, regardless of income or disability severity, receive access to special education and related disability services, such as adaptive equipment; assistive technology; one-on-one aides; accommodations; counseling; psychological services; physical, occupational, and speech therapy; and adapted materials. Each child with a disability receives an individualized education program based on their needs, which includes a statement of the special education and related services provided to the child (Center for Parent Information and Resources, 2022; National Academies, 2018). More than 7.3 million U.S. children (ages 3–21) currently receive special education related to their disability under IDEA (Office of Special Education Programs, 2022).

Built Environment

The built environment and facility conditions of schools can also impact student health, especially students with chronic health conditions (Eitland et al., 2020). This relationship became even more salient in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The average U.S. school is 42 years old, and many have heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems that are outdated (Environmental Protection Agency, 2022). The Government Accountability Office (2020) estimated that over half of all public school districts needed to update or replace multiple building systems or features in their schools. However, capital funding for such improvements may be limited as funding for school facilities primarily comes from local property taxes. Low-income communities with limited local tax bases depend on state support for these types of repairs and updates, but not all states provide capital funding for schools (Government Accountability Office, 2020).

DELIVERING CARE: SCHOOL-BASED HEALTH CENTERS

In addition to the functions described above, schools can also be the site of health care delivery. Some children can obtain some level of health care services while at school, often through school-based health centers

(SBHCs), which can provide students with preventive, reproductive, and mental health care (Allison et al., 2007; Juszczak, Melinkovich, & Kaplan, 2003; SBHA, 2014). School-based services—including, for example, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech pathology or therapy services, psychological counseling, and nursing services—may be provided by personnel employed by a school or local education agency, and Medicaid-covered health services may also be delivered to students by contracted community providers or SBHCs (Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission [MACPAC], 2024b). This section discusses the delivery of care through SBHCs; the financing of other school-based services is discussed in the sections below.

Some SBHCs provide primary care services, including well-child care and health maintenance; others provide psychosocial services, hearing and vision screening, reproductive health services, mental health services (e.g., screening and counseling), and/or oral health services. Evidence shows that, compared with access to traditional outpatient clinics, access to SBHCs increases the use of primary care; reduces the use of emergency rooms; reduces hospitalizations; and expands access to and quality of care for underserved adolescents, even those without insurance (Soleimanpour et al., 2010). SBHCs are also popular among adolescents, who report feeling more comfortable using them than using primary care settings (Mason-Jones et al., 2012). The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP; 2021b) recognizes the critical role of SBHCs in many communities, emphasizing their importance in providing accessible health care to children and adolescents, especially in underserved areas. SBHCs are integral in filling gaps in health care for many of the nation’s children, focusing on health services provision and the promotion of health through population-based education programs (AAP, 2021b).

As of 2021, there were 2,584 SBHCs serving students and communities in 48 states, and in Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico. In 2022, this number increased to 3,900 (SBHA, 2023a). Of this number, nearly half served elementary schools, with 18% serving high schools, 14% serving middle schools, and 21% representing other mixed school models. Most provide in-person services, but the percentage of SBHCs that provide some telehealth services has grown (SBHA, 2023a). While there has been growth in the number of SBHCs over the past 20 years, only about 13% of U.S. students in public schools have access to one (Love et al., 2019). Among existing SBHCs, there is variability in the comprehensiveness of services, student body enrollment rates, and parental trust (Nahum et al., 2022).

SBHCs play an important role for underserved adolescents and can greatly increase access for underinsured and uninsured children and youth and others who find care hard to access, including those living in rural areas (Mason-Jones et al., 2012). SBHCs increase access to care by removing

geographic or transportation barriers, addressing financial barriers for uninsured or underinsured students, and in some rural areas connecting students to providers in areas with otherwise limited or no access to medical providers (Kjolhede et al., 2021). According to the National School-Based Health Care Census (Love et al., 2019):

On average, compared to schools without access to SBHCs, those with access had higher percentages of Black (24 percent versus 14 percent) and Hispanic (38 percent versus 22 percent) students enrolled. They also had a higher percentage of students who received free or reduced-price lunch (70 percent versus 53 percent). Furthermore, 77 percent of schools with access to SBHCs were eligible for Title I funding, compared to 67 percent of schools without access (data not shown). The Title I program provides financial assistance to schools with high percentages of children from low-income families. (p. 759)

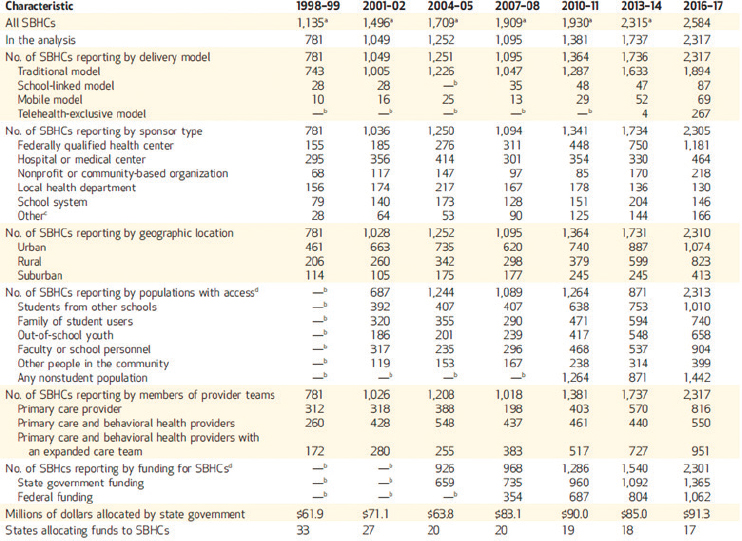

SBHCs vary across the country in several ways. According to the SBHA (2023b), survey responses in 2023 across 33 states demonstrated differences in how SBHCs are supported, such as how they are defined, how funding is allocated, and alignment with national performance measures. In 2016–2017, 82% of the centers were traditional, 4% were school linked, 3% were mobile, and 12% were telehealth exclusive. The number of centers reporting any use of telehealth technology, regardless of delivery model, grew from 66 in 2007–2008 to 467 in 2016–2017 (Love et al., 2019). In 2016–2017, 85% employed nurse practitioners and 40% of centers employed physicians. In 2016–2017, 65% of centers had behavioral health providers as members of the provider team—a smaller percentage than in 2007–2008, when the share peaked at 81%. Forty-one percent (41%) of SBHCs had expanded care teams, defined as having primary care and behavioral health care staff, along with one or more of the following: oral health providers (dentists, dental assistants, or dental hygienists), vision specialists, nutritionists or registered dietitians, and other coordinators. The proportion of centers that employed oral health providers increased from 9% in 2001–2002 to 28% in 2016–2017 (Love et al., 2019). Figure 8-1 summarizes the characteristics of SBHCs.

Effects of SBHCs on Health Outcomes

According to Knopf and colleagues (2016),

substantial educational benefits associated with SBHCs included reductions in rates of school suspension or high school non-completion and increases in grade point averages and grade promotion (Barnet, Duggan, & Devoe, 2003; Edwards, Steinman, & Hakanson, 1977; Foy & Hahn, 2009; Kerns

SOURCE: Love et al., 2019, p. 760.

et al., 2011; McCord et al., 1993; Strolin-Goltzman et al., 2014; Walker et al., 2010). Health care utilization also improved, including substantial increases in recommended immunizations and other preventive services, and a small increase in the proportion of students who reported a regular source of health care (Allison et al., 2007; Federico et al., 2010; Gibson et al., 2013). There were benefits to students with asthma, including reductions in symptoms and incidents (Guo et al., 2005; Lurie, Bauer, & Brady, 2001; Webber et al., 2003). Effects on self-reported health and mental health status were small; however, the presence of SBHCs was associated with substantial reductions in ED [emergency department] visits and hospital utilization for all conditions. Associations between SBHC exposure and risk behaviors were mixed, with apparent increases in cigarette smoking but reductions in consumption of alcohol and other substances. Regarding sexual and reproductive behaviors associated with SBHCs, contraceptive use among females increased, childbirth decreased, and prenatal care improved. (p. 8)

SBHCs also have the potential to reduce health disparities by providing services to students from diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds,

particularly underinsured or uninsured students. For example, according to Kjolhede and colleagues (2021),

School-based mental health interventions, including the area of substance use services, offer an opportunity to reach the greatest number of affected youth who otherwise may not receive behavioral health care. A study in California comparing the mental health risk profile and health use of SBHC users and nonusers demonstrated that SBHCs play a role in identifying and addressing mental health concerns that might otherwise go unmet, especially among adolescents with public or no insurance. (p. 4)

In an economic evaluation conducted by the Community Preventive Services Task Force, the economic benefit of SBHCs exceeded the intervention operating cost. For example, use of SBHCs resulted in a net savings to Medicaid because of a reduction in emergency department use for services provided to youth with asthma (Kjolhede et al., 2021; Ran, Chattopadhyay, & Hahn, 2016). SBHCs may also reduce parental productivity losses.

Future Needs for SBHCs

Integrating with Other Health Care Providers

Communication and data sharing with health care systems and federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) is needed to provide comprehensive and coordinated care. For example, the number of SBHCs using electronic health records (EHRs) has increased; EHRs can potentially improve accessibility and coordination of medical records outside of SBHC hours of operation. EHRs have the potential for linking SBHCs and students to community pediatricians, other health care systems, health information exchanges, and other primary care providers (Kjolhede et al., 2021). Confidentiality for adolescents and health information access and transfer are additional challenges for SBHCs. The SBHA and American School Health Association have developed guidelines and recommendations related to confidentiality and HIPAA and FERPA privacy laws.12

To further integrate SBHCs into health care systems, the AAP makes the following recommendations (Kjolhede et al., 2021):

- Pediatricians involved with the development and management of SBHCs should recommend care coordination practices that promote patient access to a medical home, with attention to communication

___________________

12 HIPAA stands for the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, Pub. L. No. 104-191, 110 Stat. 1936, which protects the privacy and security of health information. FERPA stands for the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, Pub. L. No. 93-380, § 513, 88 Stat. 574, which safeguards the privacy of student education records.

- between health care providers across settings. Pediatricians should share their expertise to assist not already PCMH [patient-centered medical home] accredited SBHCs to adopt practice changes in support of the medical home model.

- SBHCs and community primary care providers should be in communication to facilitate coordination of care and to avoid duplication and fragmentation of care. Use of an EHR-compatible form or a paper form, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics emergency information form for children with special health care needs, should be used, with the goal of strengthening communication (p. 7).

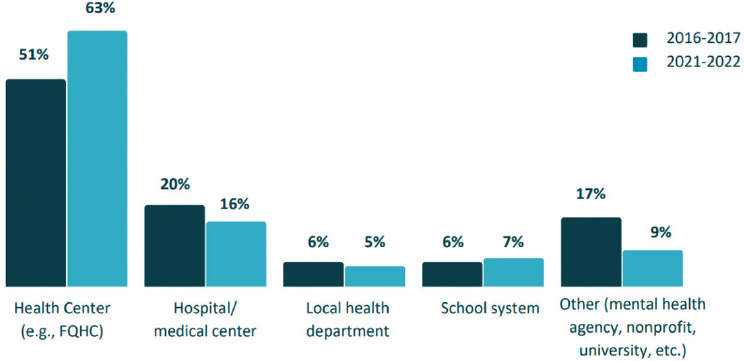

Financing SBHCs

An additional challenge for SBHCs is the development of a financially sustainable business model, as SBHCs generally require multiple funding sources to remain operational. Most SBHCs are funded by a range of public and private sources, from local and state funding to federal block grants (e.g., Maternal and Child Health Block Grants) and project grants, FQHCs, and school districts billing the federal Medicaid program (SBHA, 2022, n.d.; see Figure 8-2). The percentage of centers that bill Medicaid has increased, from 68% in 2001–2002 to 89% in 2013–2014. Similarly, billing of public and commercial insurers increased steadily in the same period, from 43% to 71% for CHIP, and from 45% to 69% for commercial payers. State grants support 76% of centers, followed by federal grants (53%) and local government grants (42%) in 2013–2014 (Love et al., 2019).

NOTE: FQHC = federally qualified health center.

SOURCE: Soleimanpour et al., 2023.

While there is variation across states and SBHCs, a 2017 survey of Medicaid offices across 18 states that provide dedicated funding for SBHCs identified three key policies that support their operation and success and grow SBHCs across the country (SBHA, n.d.).

First, seven states define SBHCs as a specific provider type, allowing differentiation of services provided at the SBHC from those of its sponsoring agency. This is helpful for directly attributing quality measures and improved health care outcomes.

Second, eight states waive prior authorization requirements for SBHCs, removing the burden of seeking permission from students’ primary care providers to be reimbursed by Medicaid. Requiring prior authorization delays and limits care and affects the financial viability of SBHCs.

Third, state policies in Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, and New Mexico require Medicaid managed care organizations to pay for self-referred visits by enrollees to the SBHC, even when out of network. This ensures payment to the SBHC even if it has no contract with the managed care organization.

DELIVERING CARE: MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

School settings and resources can also be leveraged to address mental and behavioral health, as schools provide timely access to mental health screening and services in a convenient location (Hoover & Bostic, 2021; Kern et al., 2017). As discussed in Chapter 4, mental health concerns affect children and youth in every community across the country, with a notable uptick in deleterious mental health effects since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (National Academies, 2022b, 2023c). Schools are increasingly recognized as an optimal setting for early intervention and prevention of child mental health problems, as they avoid many of the barriers to accessing mental health services in the community—providing a universal access point with the ability to reach more children who may not otherwise receive mental health support (Hayes et al., 2019; Hoover & Bostic, 2021; Neil & Christensen, 2009). School-based mental health programs can be universal (e.g., screening all students for mental health problems, programs that aim to build resiliency or mental health competence) or targeted (i.e., programs for children who are at risk of or are exhibiting symptoms of a mental health problem). There is great potential and evidence-based support for student educational curricula on subjects including suicide prevention (e.g., Sources of Strength), bullying prevention (e.g., STAC13), stress reduction and coping strategies (e.g., American Indian Life Skills), trauma, social media, conflict

___________________

13 STAC is a bullying prevention program; the acronym stands for bystander strategies: Stealing the show, Turning it over, Accompanying others, Coaching compassion.

management, wellness, and mindfulness; some states now mandate education and screening programs (Holen et al., 2013; King, Strunk, & Sorter, 2011; Krantz et al., 2023; Midgett et al., 2020; Valido et al., 2023; Wyman et al., 2010, 2023). Peer interventions to address mental health have also shown potential for confirming the importance of youth voice and effectiveness in health promotion (e.g., Sources of Strength, Adapt for Life; Wyman et al., 2010). Teacher, school professional, and parent education in these topic areas have also proven successful in increasing support for students (e.g., Question, Persuade, Refer training, QPR Institute, n.d.). Finally, school climate and behavioral management programs (e.g., Good Behavior Game, Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports) have demonstrated effectiveness in improving social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes and reducing exclusionary discipline and suicidal ideation (Kellam et al., 2011; Wilcox et al., 2008).

Research also shows that child mental health (including both mental health competence and difficulties) plays a critical role in shaping early learning experiences and outcomes; thus, interventions for promoting mental health among young children in educational settings can have benefits not only for their overall health and wellbeing, but also for their future academic success (O’Connor et al., 2018). In summary, evidence from systematic reviews on the impact and cost-effectiveness of school-based mental health interventions for children and youth is mixed; however, findings from countries including England and Australia suggest that a combination of universal and targeted prevention and early intervention approaches could have a significant impact if delivered in all schools (Stabile, 2023).

Guiding principles for an equitable whole child approach specify that transformative settings provide support in a tiered manner (Darling-Hammond & Cook-Harvey, 2018). The National Center for School Mental Health (2020) aims to improve the mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents in school settings; it recommends a tiered approach to helping school districts implement mental health interventions: (1) mental health promotion services and supports; (2) early intervention; and (3) mental health treatment. In short, support needs to be provided on a timely basis for students identified with greater needs, including special education services, health and mental health services, and family supports. Box 8-2 describes a potential model for integrating mental health into school settings.

Universal Mental Health Programs and Policies

Screening

Screening for behavioral health concerns in schools is increasingly recognized as a vital component of early intervention and support for students’

BOX 8-2

Transforming Research into Action to Improve the Lives of Students (TRAILS)

The TRAILS program is built on the foundational belief that the education sector is an essential mechanism for overcoming barriers to mental health services for children and youth. Founded at the Michigan State University School of Medicine in 2013, the TRAILS nonprofit program was created to transform the landscape of youth mental health care delivery by providing school staff with the tools necessary to provide evidence-based and culturally responsible solutions to their students. The TRAILS team works in tandem with education partners to enhance mental health services available at schools by providing tailored school training, resources, assistance with implementation, and research-based preventive and mental health programs for children. This includes equipping educators, counselors, students, and communities with evidence-based mental health care approaches, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness.

TRAILS is designed to provide partner schools with effective programming across three tiers of service: (1) social and emotional learning; (2) CBT and mindfulness; and (3) suicide prevention and risk management. The three-tiered TRAILS model aligns with the multitiered system of supports framework and the Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports approach, which are evidence-based practices for providing students with academic and behavioral supports (TRAILS to Wellness, n.d.). Tier 1, social and emotional learning, trains teachers and student support staff using a five-unit curriculum focused on self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision making. Tier 2, CBT and mindfulness, trains school mental health professionals

wellbeing (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). Using validated screening tools in education settings allows for the identification of mental health concerns at an early stage, enabling timely interventions and access to appropriate resources. It can also lead to improved academic outcomes and reduced behavioral problems. By integrating mental health screening into routine school health assessments, educators and health care professionals can help create a supportive environment that promotes the holistic wellbeing of students. While universal screening for academic concerns is typical, most school districts are not employing the same methods for behavioral health concerns (Wood & McDaniel, 2020).

One study of high school students in Pennsylvania found that youth in the universal screening group had nearly six times higher odds of being identified with depression symptoms and more than twice the odds of starting depression treatment compared with those in the targeted screening group (Guo & Jhe, 2021). Another study found that training school nurses

(e.g., counselors, social workers) with seven- or ten-session manuals designed to help students cope with symptoms of depression and/or anxiety, using coping mechanisms such as mindfulness, relaxation, cognitive coping, behavioral activation, and exposure. Tier 3, suicide prevention and risk management, trains partners on the implementation of the TRAILS Student Suicide Risk Management Protocol, a clear set of steps for responding to and coordinating care for suicidality in students. This tier offers audience-specific training options for all school staff, families, and community members.

A growing body of evidence supports adoption of the TRAILS program. The seminal TRAILS study by Rodriguez-Quintana, Walker, and Lewis (2021) focused on the impact of the TRAILS Coping with COVID-19 manual, which was grounded in CBT and mindfulness. This manual offered strategies for helping students cope with pandemic-related uncertainty using a three-step model: (1) identify which portions of the situation are within one’s control, (2) acknowledge and accept feelings about things beyond one’s control, and (3) identify strategies to plan for or proactively address any portions of the situation that are within one’s control. This resulted in increased use of CBT among school mental health professionals and significant decreases in student depression and anxiety (Rodriguez-Quintana, Walker, & Lewis, 2021). A secondary, 3-year study of 968 high school students by Smith, Almirall, and colleagues (2022) found that one-quarter of students showed a significant reduction in symptoms of depression and anxiety. TRAILS is an example of effective, school-based mental health services that can be accessed and tailored to schools across the nation. With wider adoption, this program could provide transformative care through evidence-based, sustained mental health support for students.

SOURCE: Elizabeth Koschmann, presentation to committee, June 2023.

to recognize depression allowed prompt referral of students for treatment (Law, McClanahan, & Weismuller, 2017).

Additionally, screening for eating disorders in adolescents is an important consideration because of the alarming prevalence and severe consequences associated with these conditions. Adolescence is a critical period for the development of eating disorders, with many cases emerging during this time. Early detection is critical, as eating disorders—such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder—can lead to numerous physical and psychological complications. Disordered eating is common, with more than one in five children and adolescents showing symptoms of disordered eating. Furthermore, eating disorders can have devastating long-term consequences, affecting not only physical health but also psychological wellbeing. Adolescents with untreated eating disorders are at heightened risk of developing comorbid mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders.

Socioemotional Learning

Consensus is growing among researchers who study child development, education, and health that socioemotional skills are essential to learning and life outcomes (National Academies, 2023c). Broadly speaking, “socioemotional learning” refers to the process through which individuals learn and apply a set of social, emotional, and related skills, attitudes, behaviors, and values that help direct their thoughts, feelings, and actions in ways that enable them to succeed in the settings where they learn and grow (e.g., Jones et al., 2017). Furthermore, research indicates that high-quality, evidence-based programs and policies that promote these skills among children can produce positive outcomes, including improved behavior, attitudes, physical and mental wellbeing, academic achievement, and college and career readiness and success (Bierman et al., 2010; Diamond & Lee, 2011; Durlak et al., 2011; Hurd & Deutsche, 2017; Jones et al., 2017; McClelland et al., 2017).

A great number of socioemotional programs are available for schools and early childhood education providers; these programs vary widely in emphasis, teaching strategies, implementation supports, and general approach. For example, some programs target emotion regulation and pro-social behavior, while others focus on executive function, growth mindsets, character traits, or other similar constructs. Some programs rely primarily on teacher modeling and whole-class discussions, while others incorporate such methods as read-alouds, games, role-playing, and music. Programs also vary substantially in their emphasis and material support for adult skill-building, school culture and climate, family and community engagement, and other components beyond direct child-focused activities or lessons.

There have been a small number of large multiprogram studies and trials of specific interventions in preschool, school, and afterschool contexts. Results from these studies are mixed. For example, large-scale, multisite, national studies show small or null effects (e.g., Social and Character Development Research Consortium, 2010), but many smaller, single-site studies report important and meaningful effects (e.g., Jones, Brown, & Lawrence Aber, 2011). Specific socioemotional learning interventions have been the subject of randomized trials; for example, a randomized trial of the RULER14 program (see, e.g., Rivers et al., 2013) demonstrated changes in children’s emotional competencies (Hagelskamp et al., 2013). The MindUp program emphasizes self- and physiological regulation and has showed positive results in children’s cognitive and emotional regulatory skills (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015).

In general, socioemotional learning programs tend to have the largest effects among students with the greatest number of risks or needs, including

___________________

14 RULER stands for Recognizing, Understanding, Labeling, Expressing, and Regulating emotions.

those of lower socioeconomic status and those who enter school behind their peers either academically or behaviorally (e.g., Jones, Brown, & Lawrence Aber, 2011).

Schools, early childhood education settings, and out-of-school-time programs provide a unique opportunity to build students’ socioemotional skills; address trauma, including that specific to pandemic experiences; and move toward educational equity. Currently, there are few evidence-based programs or interventions that successfully integrate these three areas, which can lead to unintended consequences, including focusing on student deficits rather than leveraging student assets and building on the rich experiences, knowledge, skills, and curiosity that students bring into the classroom (Ginwright, 2018; Zacarian, Alvarez-Ortiz, & Haynes, 2017).

Promoting Positive School Climate and Educator Wellbeing

Research has documented that a lack of mental health and wellbeing (e.g., depression, stress) of teachers affects their perceptions of children (Gilliam, 2005; Perry et al., 2008, 2010). Many studies on classroom climate have reported that the absence of responsive, supportive interactions with adult caregivers strongly affects young children’s socioemotional functioning (Gilliam et al., 2016; Jones Harden & Slopen, 2022; Pianta & Hamre, 2009).

Mental health consultation is an approach for early childhood that focuses on adults working in classrooms with young children (Cohen & Kaufmann, 2000; Donohue, Falk, & Provet, 2000). Many of these programs are supported by school psychologists and other mental health personnel, who help teachers develop the capacity to provide socioemotional support in the classroom and address the individual mental health needs of vulnerable children (Splett et al., 2013). For example, the Center of Excellence for Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation (IECMHC) provides consultation to Head Start programs, classroom staff, and families (Ash, Mackrain, & Johnston, 2013; Brinamen, Taranta, & Johnston, 2012; Duran et al., 2009). At the program level, IECMHC consultants collaborate with administrators to develop policies and procedures (e.g., disciplinary policies, communication strategies, professional development opportunities) that promote children’s socioemotional competence and a positive climate. IECMHC consultants support teachers in classrooms in the use of positive behavior supports and strategies for managing their classrooms and addressing the needs of specific children. IECMHC consultants may also collaborate with teachers and parents to create supports for children already showing challenging behavior, which may result in fewer child suspensions and expulsions.

Studies have shown that IECMHCs lead to improved socioemotional competence and reduced behavior problems among participant children (National Academies, 2023c). IECMHC is also associated with improved

teacher–child relationships and classroom climate. Participating teachers have less stress and better skills in teaching socioemotional lessons. One study found that participation in an IECMHC program attenuated the association between teacher depression and child expulsion (Silver & Zinsser, 2020). At the school level, IECMHC has led to lower suspension and expulsion rates, less teacher turnover, and better staff interactions. And parents participating in IECMHC displayed better relationships with their children and missed fewer work days (Brennan et al., 2008; Center of Excellence for IECMHC, 2021; Hepburn et al., 2013; Perry et al., 2010; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Overall, these findings suggest that IECMHC programs can reduce disparities in mental health outcomes and the sequelae of these outcomes (e.g., suspension, expulsion; Center of Excellence for IECMHC, 2021; Shivers, Faragó, & Gal-Szabo, 2022).

Universal Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

The Community Preventive Services Task Force recommends both universal and targeted school-based CBT programs for reducing depression and anxiety symptoms among children at risk. Universal CBT programs are delivered to all students in a school setting, regardless of their mental health status. They are geared toward helping students regulate their emotions and establish helpful coping strategies (The Community Guide, 2019a,b). Targeted interventions are provided to children who have been identified as at risk, not children who have already been given a clinical diagnosis. For the targeted programs, 29 studies show evidence that small decreases were reported for symptoms of depression and anxiety; the effect was larger when the intervention was delivered by external mental health professionals rather than trained school staff (The Community Guide, 2019b). Most important, incorporating mental health programming within school settings has been associated with improved academic outcomes, including grades, attendance, and test scores (Kase et al., 2017).

Federal Support for School-Based Mental Health Services

Federal funding for public schools to support direct mental health and socioemotional services has expanded over time. For example, in February 2023, the U.S. Department of Education (ED) announced expanded funding, through the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (BSCA, 2022), for the School-Based Mental Health Services Grant Program, which provides funding to increase the number of school psychologists, counselors, and other mental health professionals serving students through “recruitment and retention efforts, the promotion of re-specialization and professional retraining of

existing mental health providers, and through efforts to increase the diversity and cultural and linguistic competency of school-based mental health services providers” (ED, 2023, para. 9). In addition, the American Rescue Plan Act’s Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (2021) “provides more than $122 billion to help pre-K through grade 12 students recover from lost time in schools by supporting their mental health, as well as their social, emotional, and academic needs” (§ 2001). Allowable uses for this funding include “providing mental health services and supports, including through the implementation of evidence-based full-service community schools” (American Rescue Plan Act, 2021, § 2001).

SCHOOL-BASED HEALTH CARE WORKFORCE

School-based health providers play a role in supporting the health and wellbeing of children, youth, and families. Other providers offer different forms of health care in K–12 schools, including school psychologists, social workers, and counselors. These can play a critical role, supporting student development and success across socioemotional and academic domains. Not all schools have access to these providers. This section also briefly discusses the role of school nurses, who provide clinical services to children in schools.

It is also important to note that innovative programs at the state level have been implemented to train and credential students to work directly with their peers in school—for instance, in programs that provide suicide awareness training or knowing when to talk with a trusted adult (see, e.g., Muehlenkamp & Quinn-Lee, 2023). Two recent global systematic reviews of school-based peer-led interventions found that these interventions appear to demonstrate evidence for effectiveness, suggesting peer-led interventions may be a promising strategy for health improvement in schools, particularly for improving health-related knowledge (Dodd et al., 2022; King & Fazel, 2021). As more states and schools implement such programming, robust evaluation to understand key implementation considerations is needed.

An estimated 132,300 school nurses care for children in U.S. schools (Willgerodt, Brock, & Maughan, 2018). School nurses are frontline health care providers, serving as a bridge between the health care and education systems. They engage school communities, parents, and health care providers to promote wellness and improve health outcomes for children. School nurses can provide for the health and safety needs of students and staff or act as care coordinators for the increasing number of children with complex medical needs attending public schools. They can also provide more universal health-promoting activities, such as screenings and immunization, or organize wellness programming for students and staff. School nurses also assist students and parents with health insurance enrollment and obtaining access to health care providers (Gustafson, 2005). The National

Association of School Nurses (NASN) and the AAP recommend that school districts provide a full-time school nurse in every school building (Council on School Health et al., 2016). Box 8-3 describes the core elements of the school nursing practice framework as articulated by the NASN.

School nurses are essential for expanding access to high-quality health care for students, especially in light of the increasing number of students with complex health and social needs. Access to school nurses helps increase health care equity for students. “For many children living in or near poverty, the school nurse may be the only health care professional they regularly access” (National Academies, 2021e, p. 108).

However, only 65.7% of public schools in the United States have access to a full-time school nurse, a number that varies based on location (Willgerodt, Brock, & Tanner, 2023). Many school nurses rotate among

BOX 8-3

School Nursing Practice Framework

According to NASN (2024), four interlocking elements are present in the school nursing practice framework.

Care Coordination

- Provide direct care for emergent, episodic, and chronic mental and physical health needs.

- Connect student and family to available resources.

- Collaborate with families, school community, mental health team (including school counselors, social workers, and psychologists), and medical home.

- Develop and implement plans of care.

- Foster developmentally appropriate independence and self-advocacy.

- Provide evidence-based health counseling.

- Facilitate continuity of care with family during transitions.

Leadership

- Direct health services in school, district, or state.

- Interpret school health information and educate students, families, school staff, and policy makers.

- Advocate for district or state policies, procedures, programs, and services that promote health, reduce risk, improve equitable access, and support culturally appropriate care.

- Engage in and influence decision making within education and health systems.

- Participate in development and coordinate implementation of school emergency or disaster plans.

- Champion health and academic equity.

buildings and may have to cover two to three schools in a day or week. For example, 70% of urban schools employ a full-time nurse, whereas only 56% of rural schools employ a full-time school nurse. There are also regional differences, with the Northeast and South having the highest rate of full-time school nurses. Conversely, the West has the lowest rate at 33%, and approximately half of these work only part time (Willgerodt, Brock, & Tanner, 2023). There are also small variations in the distribution of school nurses by level of school, with high schools having slightly less coverage by either full- or part-time school nurses when compared with primary and middle schools (75% vs. 86% and 87%, respectively; Spiegelman, 2020). The current distribution of school nurses points to an equity gap across socioeconomic and geographic areas (Gratz et al., 2023). Until the workforce and funding streams support the goal of having a nurse in

- Share expertise through mentorship/preceptorship.

- Practice and model self-care.

Quality Improvement

- Participate in data collection for local, state, and national standardized data sets and initiatives.

- Transform practice and make decisions using data, technology, and standardized documentation.

- Use data to identify individual and population-level student needs, monitor student health and academic outcomes, and communicate outcomes.

- Engage in ongoing evaluation, performance appraisal, goal setting, and learning to professionalize practice.

- Identify questions in practice that may be resolved through research and evidence-based practice processes.

Community/Public Health

- Provide culturally sensitive, inclusive, holistic care.

- Conduct health screenings, surveillance, outreach, and immunization compliance activities.

- Collaborate with community partners to develop and implement plans that address the needs of school communities and diverse student populations.

- Teach health promotion, health literacy, and disease prevention.

- Provide health expertise in key roles in school, work, and community committees/councils/coalitions.

- Assess school and community for social and environmental determinants of health.

SOURCE: NASN, 2024.

every school, the current school nursing workforce needs to be allocated to target specific groups of children that concurrently lack access to pediatric primary care services. According to an NASN survey, school nurse respondents (registered nurses) stated that almost half of their time was spent on care coordination (e.g., acute and chronic condition management) and only about one-quarter of their time was spent on community and public health activities (screening, vaccination, health promotion and prevention, addressing social determinants of health; NASN, 2022). This demonstrates an opportunity to improve the ability of school nurses to support both care coordination and public health activities.

School nursing services have been shown to be a cost-beneficial investment of public money (Wang et al., 2014), warranting careful consideration by policy and decision makers when resource allocation decisions are made about school nursing positions. In a study of 78 school districts, Wang and colleagues (2014) found that

during the 2009-2010 school year, at a cost of $79.0 million, the ESHS program prevented an estimated $20.0 million in medical care costs, $28.1 million in parents’ productivity loss, and $129.1 million in teachers’ productivity loss. As a result, the program generated a net benefit of $98.2 million to society. For every dollar invested in the program, society would gain $2.20. Eighty-nine percent (89%) of simulation trials resulted in a net benefit. (p. 642)

School nursing services provided in this study had a higher balance of acute and chronic care than wellness efforts, which resulted in students remaining in school rather than having to be out of school to receive treatment from a health care provider.

In the United States, funding for school nurses largely comes from ED (Wang et al., 2014; Willgerodt et al., 2024). Other funders include Medicaid, health departments, special education funds, and grants. Medicaid offers a potential sustainable revenue stream to pay for school nurses, as schools may bill for certain services performed by school nurses for Medicaid-eligible students (requirements and reimbursable services vary by state). Currently, approximately 40% of school nurses/schools bill Medicaid (Willgerodt et al., 2024).

FACILITATING AND FINANCING SCHOOL-BASED HEALTH SERVICES

While increasing school-based services is likely to have positive effects on health and education, balancing time and focus for both academic activities and health and wellness activities can be challenging. With great

attention to academic outcomes, school leaders and teachers may be reticent to use valuable classroom time for activities that do not directly improve academic achievement. Improved management of physical and mental health conditions, however, may reduce absenteeism and facilitate academic achievement.

Parents and guardians of school-aged children need to understand the current and potential benefits of integrating health and education. Although they may distrust schools and health care delivery systems and have concerns about data sharing, engaging parents and communities by demonstrating the conveniences and positives of such integration will be necessary to best serve children and youth.

Regulations related to data sharing can be a barrier to integrating health care and education. FERPA (1974) protects the privacy of student education records, and HIPAA (1996) protects sensitive patient health information from being disclosed without the patient’s consent or knowledge. While education and health care share the goal of improving children’s health and education, different interpretations of these regulations and lack of easy data sharing can make partnership challenging. Clarifying the mechanisms and memoranda of understanding related to data sharing would further the potential of integration.

As described above, schools vary widely in services offered and the degree to which their practices are evidence based. They also differ in funding sources. Some support comes directly from Medicaid but much of the funding also stems from state and local school funds and various federal sources; each funding stream is described in turn below. These sources lead to variations that can exacerbate racial and other health disparities because of the impact of structural racism on neighborhoods and communities and on the financing of schools. In a 2022 study, only 12% of public schools reported that they could successfully deliver mental health services to all student in need (Marceno et al., 2023).

State and Local Education Funds

The structure of general funding for public education affects allocations for school-based health services. Public schools are funded by a combination of state and local education dollars, with some support from federal funding. Federal aid on average represents less than 10% of public education dollars (Gordon & Reber, 2021). By contrast, 46% of school districts’ revenue emanates locally, and 47% derives from state governments—with local property taxes and state sales and income taxes as primary sources—creating wide differences across districts in resource availability. Because the education system relies so heavily on community wealth, differences in resources reflect both the prosperity and racial divide in the country.

High-poverty, majority White school districts receive about $150 less per student than the national average; however, they receive nearly $1,500 more than high-poverty, majority non-White school districts (EdBuild, 2019).

Combined, federal, state, and local government resources support the salaries of public school–employed nurses, counselors, and other staff who provide health care with some or all of their time. Schools bill Medicaid for some health care services for Medicaid-eligible students; however, the extent and scope of Medicaid billing varies widely across schools, especially across urban and rural schools, school levels, and regions of the country (Willgerodt, Brock, & Maughan, 2018).

Financing School-Based Health Services through Medicaid and CHIP

In 2014, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began allowing schools to use Medicaid for free school-based health care services. However, uptake of this policy has been slow (CMS, 2014; Healthy Students, Promising Futures, n.d.; Wilkinson et al., 2020). As of October 2023, 25 states amended their state plans or otherwise expanded coverage to include school-based services that are not part of an individualized education program or individualized family service plan (IEP/IFSP).15 Of those, 18 states expanded coverage for all services identified as medically necessary, while the remaining states cover a more limited set of services, often including behavioral health care. In many cases, the primary motivation for these expansions was to improve access to services, particularly behavioral health care, and to obtain Medicaid payment for services that were already being provided to students enrolled in Medicaid without an IEP/IFSP (MACPAC, 2024b; Wilkinson et al., 2020).