Launching Lifelong Health by Improving Health Care for Children, Youth, and Families (2024)

Chapter: 9 Measurement and Accountability

9

Measurement and Accountability

Implement performance measures that reflect “upstream” access as well as outcomes that meaningfully assess how populations experience health care delivery. Work to harmonize, or at least assure meaningful alignment, in outcome measures that are promoted by [federal programs].

—Comment to the committee by physician and medical director of integrated care, Boston, MA

To advance the vision for child health and wellbeing set forth in this report, enhanced accountability for child health and wellbeing at federal, state, and local levels is needed. Such accountability will require better and more effective measures, combined with more powerful incentives for the players involved. The United States already employs an extensive array of measurement and accountability approaches, each of which involves specifying performance goals, targets, and measures to confer rewards or withhold benefits for those being held accountable. While these efforts have resulted in some changes, taken together, existing approaches have not resulted in sufficient improvements in health care access, quality, equity, and outcomes for children and youth (Bethell, Blackwell et al., 2022; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2024b; Lebrun-Harris et al., 2022; Schiff, Filice, & Chen, 2024).

This chapter reviews progress, gaps, and the impact of existing measurement and accountability strategies related to the child health care system, and outlines opportunities for improvement. The review considers broad characteristics of accountability measurement systems that would be needed to improve child health and wellbeing outcomes, drawing on the

guiding principles detailed in Chapter 1 (see Table 9-1). In response to this review, the committee identified priority areas and opportunities for implementing an accountability measurement strategy that would support health care system transformation. These priority areas are discussed in depth after a brief summary of current strategies.

CURRENT MEASUREMENT AND ACCOUNTABILITY STRATEGIES

Health care is among the most regulated and measured of all sectors in society. In its research, the committee found that existing health care measurement and accountability strategies range from payers using quality and performance metrics to hold health care plans and providers accountable (Gardner & Kelleher, 2017; National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2023) to using metrics in licensing (Welch et al., 2017); certification (American Board of Pediatrics, n.d.; Miles, 2009); credentialing of health care professionals (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies], 2017b); professional education program accreditation (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 2023a); and accreditation of health plans, hospitals, and other health care facilities (Hussein et al., 2021; Joint Commission Resources, 2023; National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2023). Related to these strategies are efforts to report quality and performance measurement results to payers, patients, and consumers to engage market forces and drive performance improvements (Commonwealth Fund, 2022). In addition, the federal Government Performance and Results Act (1993) administered by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) requires all federal departments and agencies to set and track performance indicators related to the achievement of strategic goals, many of which relate to child health and wellbeing (Government Accountability Office [GAO], 2023b,c; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2023). Federal agencies also use performance measures to monitor many child health–related state and community programs that employ federal dollars (Bethell, Wells et al., 2023; Noorihekmat et al., 2020; Soto, Sicotte, & Motulsky, 2019)—these include Medicaid (Federal Register, 2023); Title V Block Grants (Kogan et al., 2015); community health centers (Cole et al., 2023); and home visiting (Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA], n.d.c), early intervention (Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center, n.d.), child welfare (Administration for Children and Families [ACF], n.d.), nutrition, and early childhood education programs (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2018, 2019, 2022). Other federal laws require nonprofit hospitals to assess and report on their efforts to provide charity care and partner with the local community to improve the health of the populations they serve, in order to maintain their tax-exempt status. Finally, numerous national, state, and local datasets and surveys of families

TABLE 9-1 Guiding Principles and the Characteristics of Accountability Measurement Systems

| Guiding Principles* | Principles Applied to Measurement Strategies |

|---|---|

| Employ a Life Course Approach A life course approach requires a system-wide focus on prevention and promotion from preconception to adulthood, emphasizing upstream prevention of many health problems and promotion of healthy experiences. |

Measuring the outcomes of all children and youth in a community and focusing on promoting functioning and wellbeing, rather than solely care processes or disease states, are the next steps to improve effectiveness of the health care system. Large health care systems with poor health outcomes for children in their communities cannot be said to be high-performing organizations. Population health measures would focus on promoting accountability for whole person and population wellbeing and allow for the assessment of health equity across various subgroups. |

| Partner with Families and Communities Family and community-centered care recognizes the importance of collaboration with families and communities, who are central to child health and wellbeing, in all stages of decision making. |

Use of measures salient and important to the community is essential to ensuring that child health care systems are accountable to their communities and that communities engage fully in the coproduction of health care measures and improvements. Families and local organizations are essential partners in identifying ways to address social and relational health risks in their community (Bethell, Wells et al., 2023; Halfon, DuPlessis, & Inkelas, 2007; Palmer & Bailey, 2022; Petiwala et al., 2021). Further, measures of health care experiences and outcomes benefit from person-reported information (Arsiwala et al., 2021; Bethell, Blackwell et al., 2022; Bethell, Oppenheim et al., 2023; Co et al., 2011; Ghandour et al., 2018; Halfon, DuPlessis, & Inkelas, 2007; Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, 2023). |

| Prioritize and Drive Equitable Outcomes Moving toward health equity requires an intentional redistribution of focus, including resources and accountability, to families and communities that have long endured underinvestment and structural disadvantage. |

Accountability for health equity needs to be featured either through parallel measures or through equity-weighted outcomes to ensure that all children are thriving (Agniel et al., 2023). Assessing disparities, discrimination, and experiences of structural racism typically requires person-reported information (Agniel et al., 2023; Calvert et al., 2022; Petkovic et al., 2017; Sisodia, Rodriguez, & Sequist, 2021). Seamless methods for collecting and integrating information and publicly sharing aggregated results will need to be created (Brands et al., 2022; Jenssen et al., 2023). Measures that address health equity issues of importance to community members could reflect, for example, rates of infant mortality and low birth weight, school readiness and engagement, positive mental health, and/or high school graduation. |

| Guiding Principles* | Principles Applied to Measurement Strategies |

|---|---|

| Make It Sustainable over Time Successful transformation depends on incentives and tracking performance on shared goals, ensuring transparency and open exploration of performance in partnership among health care systems, other child-serving sectors, and the families and communities they serve. |

Improving population health and wellbeing outcomes for all children requires coordination within the child health care system and commitment and initiative between the health care, public health, and social services sectors. Common goals and shared accountability measures will be critical. |

*See Chapter 1 of this report for a discussion of the committee’s guiding principles in conducting research for the study report.

NOTES: The committee uses the term “population health” to refer to the health of a group of people, defined broadly. “Population” and “community” are used similarly to refer to a group of people with a shared characteristic, such as their geographic location, demographic status, health care system or provider, or even health diagnosis. The committee considers “health equity” to be the state in which everyone has the opportunity to attain their full health potential and no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or any other socially defined circumstance (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017a, 2021b). Multiple dimensions of outcomes could be considered in measuring progress toward health equity. Selection of appropriate measures will be tied to the population and improvements being considered.

SOURCE: Generated by the committee.

and youth are collected routinely and used to formally track and publicly report on child health care quality, outcomes, needs, risks, disparities, and overall system performance (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics [FCFS], 2022a; Jablonski & Guagliardo, 2005; Kogan et al., 2015).

Each of these measurement and accountability strategies plays an important role, with various strengths and infrastructure. Yet misalignment; limited numbers of population health and wellbeing outcomes; lack of adequate financial incentives; inefficiencies in data collection; limited data sharing; and failure to include patients, families, and communities adequately have prevented these numerous resources from being effective in achieving substantial improvements in child and youth health and wellbeing for many communities. Table 9-2 summarizes the various accountability strategies and opportunities for improvement.

Inadequacies of Current Measurement and Accountability Systems

Despite the enormous effort and resources employed to implement measurement and accountability strategies, their collective impact in improving children’s quality of care and health outcomes has been slow and limited. Health care providers and systems typically report that current quality, safety, and accountability metrics are burdensome, often duplicative, and

| Existing Strategy Area | Key Opportunities for Improvement |

|---|---|

| Ensuring the quality of the workforce and health care organizations (e.g., professional licensing and certification, education, hospital and health plan accreditation, hospital community benefits standards) | Map standards used with objective performance and competence areas. Develop measures of diversity in workforce and community access. |

| Incentivizing high-quality care and positive outcomes (e.g., health plan and provider contracts using alternative payment models linked to measures of performance; federally required performance measures for Medicaid, community health centers, Title V, and other health-related state programs, such as home visiting and early intervention) | Focus and align performance measures across essential system collaborators, and link measures to drive shared goals for child and youth and wellbeing population outcomes. |

| Tracking and driving system-wide and federal agency performance (e.g., national datasets and surveys; Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics; National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports (NHQDRs); tracking of federal agency strategies and performance indicators based on the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA, 1993) | Coordinate and better disseminate annual federal State of America’s Children Report and NHQDRs with a focus on aligned measures and child wellbeing outcomes. Coordinate across federal agency strategies and performance indicators tracked through GPRA to drive cross-agency efforts to improve child and youth wellbeing. |

| Engaging, activating, and partnering with consumers and patients (e.g., family engagement in systems and quality-of-care performance monitoring and improvement; public and consumer reporting of quality and performance with mechanisms for driving choice and action) | Advance family- and community-engaged governance structures; routinely collect and integrate family and community data into health care data systems; formalize use of lived experience stories; optimize use of digital health and interoperable data sharing within and among health care, public health, and community systems; and center family and youth reports of wellbeing, priorities, and quality of care. |

SOURCE: Generated by the committee.

lacking incentive to focus the health care system on improving health outcomes (CMS, 2023b,f; Jacobs et al., 2023). Many prior recommendations point to feasible approaches for improvement that have yet to be widely embraced (Bass et al., 2022; Bethell, Oppenheim et al., 2023; Coker & Perrin, 2022; Garg et al., 2023; Landers et al., 2020; Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2012b; National Academies, 2019d, 2021b; Wiley & Matthews, 2017). These and other sources suggest that current approaches are inadequate for a transformed health care system in four ways.

First, the system centers largely on provider performance as a primary outcome, especially measures of care processes. Performance measures are

employed mainly for compliance, accreditation, and training purposes at individual clinician, health care site, hospital, or health plan levels. The extensive focus on clinician and provider site behavior—without consideration of numerous other factors that affect child population health and without strong incentives and supports to improve on measures—limits their usefulness in improving outcomes for children and youth.

Second, quality assurance and accreditation accountability approaches engage health care systems directly in health care accountability initiatives but rarely include families or communities. Collection of data, planning efforts, data processing, and reporting efforts are centered in health care settings with little input from community members nor any consistent history of community participation or coproduction of quality planning or assessment. Reporting to patients, families, and communities on performance or child health is infrequently considered. In addition, few efforts have centered digital literacy and numeracy education for patients, families, and communities to improve their engagement. While most health care systems and accountability measurement strategies do not emphasize or effectively use person, family, and community measures of experience or outcomes (Austin et al., 2020; Bethell, Wells et al., 2023; National Health Law Program, 2021; Omoloja & Vundavalli, 2021), support for doing so is growing (CMS, 2023a,b; Schiff, Filice, & Chen, 2024).

Third, the actual measures employed in health care accountability are largely professional and site centered, as opposed to person, family, and community centered. A compliance and assurance mindset produces a clinician or health care organization orientation largely to the exclusion of community, patient, and family outcomes. In fact, such professionally oriented measures usually mean that performance is only judged among children and families that access services, while those without access are not included or reflected in denominators. Because of this, accountability results may misrepresent a best possible lens on health care performance without considering barriers to access and disparities. As an example, public and commercial payers often measure well-child visit rates and quality.1 Yet wide gaps in both utilization and quality of well-child services persist (Bethell et al., 2004; Hirai et al., 2018; Schor & Bergman, 2021). Survey results estimate that fewer than half of children enrolled in Medicaid receive important well-child services recommended to occur in the critical first 15 months of a child’s life and that performance has not improved in the past 10 years (CMS, 2022b). Similarly, only about one-third of young

___________________

1 Measures include the proportion of all children who receive well-child services, based on the periodicity defined in the national Bright Futures Guidelines (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2017), which are the standard of care that health plans are required to provide through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010), as specified in Section 2713 of the Public Health Service Act (Coverage of Preventive Health Services, 2023; HHS, 2023).

children receive screening for their development, and most families report not being asked about their concerns on their child’s development (Hirai et al., 2018). Despite the existence of performance measures used to track well-visit rates, and rates of developmental screening, little progress has been made in states or local areas toward optimizing well-child services.

Fourth, measures and accountabilities among levels of the health care system and among sectors serving children are not aligned. Traditional health care accountability metrics offer little attention to coordination across sites, providers, or sectors. Even when similar performance topics are shared across programs (e.g., developmental screening, well-child visit rates), specific measures often are not aligned nor is the scoring, reporting, and dissemination of data resulting from the wide array of measures employed (Bethell, Wells et al., 2023; Boudreau et al., 2022; IOM, 2012b; National Academies, 2021b). For example, the federal government alone has numerous, often competing programs that aim to measure performance and outcomes for many, often overlapping, aspects of child health care or health, including (1) state Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) measures; (2) CMS-endorsed National Committee for Quality Assurance Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set measures; (3) HRSA Community Health Centers measures; (4) Title V Block Grant National Performance and Outcomes measures; (5) ACF child welfare program measures; (6) HRSA/ACF Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting measures; and (7) U.S. Department of Education Individuals with Disabilities Education Act Early Intervention program measures. A review of these programs, conducted through the Child Health and Development Project in its design of the Engagement in Action Framework (EnAct!; Bethell, Buttross et al., 2023), found that across the aforementioned programs, 309 specific performance measures were used, covering 71 unique topics; only 13 of these topics overlapped across three of more of these seven programs. Box 9-1 identifies the 13 performance measure topics that are used by three or more programs in four categories: insurance, access, and utilization; screening-related processes of care; treatment and counseling-related processes of care; and intermediate and health-related outcomes. See Appendix D for a full list of the performance measurement topics.

Other Efforts to Take Stock of Measurement Assets and Gaps

The 2004 report Children’s Health, the Nation’s Wealth was one of the first efforts to comprehensively take stock of child health measurement and data assets and gaps (National Research Council [NRC] & IOM, 2004). The report concluded that the nation is fortunate to have a wide array of data sources addressing the health of children and adolescents and health care quality for them, each providing a partial set of observations and benchmarks with which to answer questions of concern. However, it also

BOX 9-1

Key Performance Measurement Topics Used by Federal Child Health Programs

Insurance, access, and utilization

- Adolescent well visits

- Prenatal and postpartum care

- Well-child visits

- Receipt of dental care services

- Well-woman visits

Screenings, referrals, and follow-ups

- Early childhood developmental screening

- Completed depression referrals

- Tobacco, alcohol, or other drug cessation referrals/treatments for adults and/or caregivers

- Depression screening

Care process, education, and counseling

- Weight assessment, counseling for nutrition, physical activity

Health-related and intermediate outcomes

- Low birth weight

- Child and adolescent immunization status

- Emergency department visits and injury hospitalizations

SOURCE: Generated by committee.

noted the incomplete patchwork of clinical information systems, periodic sample surveys, registries, and vital and health statistics reported by state and federal agencies and concluded that this patchwork does not facilitate the wholistic determination of either health status or health care quality for the nation’s children and youth. The report’s survey of existing datasets and methods reveals the need to create a national core set of salient measures; its authors suggested collecting data using these measures in every jurisdiction; using a standard approach for analysis; and making the data and analysis available in a form that will enable policy makers, health care administrators, health care systems, and the general public to evaluate progress on child health (NRC & IOM, 2004).

Box 9-2 provides an updated summary of the key national data sources important to understanding and driving improvements in child and youth wellbeing since the release of the NRC and IOM (2004) report.

BOX 9-2

Key National Sources of Data on Children’s Health by Sponsor

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- National Vital Statistics System (NVSS)

- Mortality (NVSS-M)

- Natality (NVSS-N)

- Fetal Death (NVSS-FD)

- National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)

- National Survey of Family Growth

- National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

- Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System

- School Health Policies and Practices Study

- Numerous online data query surveillance systems, for example:

- WISQARS (injuries; https://wisqars.cdc.gov)

- WONDER (mortality; https://wonder.cdc.gov)

- NHIS Interactive Data System

- National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and Tuberculosis Prevention

- National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases

- National Immunization Surveys

Health Resources and Services Administration

- Maternal and Child Health Bureau

- National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH)

- NSCH Online Interactive Data Query System (www.childhealthdata.org)

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- Medical Expenditures Panel Survey and online data tools to access findings

- Kids Inpatient Database (KIDs) and online data query for hospital data

- National Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Benchmarking Database

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health

National Institutes of Health

- Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

U.S. Department of Commerce

U.S. Census Bureau

- Current Population Survey and online data platform (Census Bureau, n.d.b)

- American Community Survey and online data platform (Census Bureau, n.d.a)

SOURCE: Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2023; analysis to update the data sources summary in Children’s Health, the Nation’s Wealth (NRC & IOM, 2004).

In addition, a growing number of online data query and dataset resources are now available to support analyses of national, state, and local measures that can inform and track the impact of health care system transformation efforts. This includes the numerous online dataset access and results query tools sponsored by the federal government (e.g., www.childhealthdata.org)2 and an array of private-sector efforts (Brandeis University Heller School of Social Policy and Management, n.d.; KFF, n.d.; Kids Count Data Center, 2020; University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, 2024).

The committee found evidence of progress since Children’s Health, the Nation’s Wealth (NRC & IOM, 2004) in the availability of important child health data, including the National Survey of Children’s Health (Ghandour et al., 2018), data from the National Center for Education Statistics (McCoy, Cuartas, & Seiden, 2024), and new performance measurement systems (CMS, 2023a, 2024a; Kogan et al., 2015). Despite this progress, more recent efforts to evaluate the availability and effective use of measures, specifically maternal and child health measures, have arrived at similar conclusions as those in the 2004 report—population health outcomes, health equity, and community-level data and involvement, as well as alignment across child-serving systems, had all received inadequate attention in the development of measures. For example, the national, multisector, HRSA-funded Maternal and Child Health Measurement Research Network (MCH MRN), which operated between 2013 and 2021, took stock of maternal and child health measures and their use, identified gaps and strategic priorities, and took steps to create new measures and measurement resources (e.g., online searchable MCH Measurement Compendium; Child and Adolescent Health Measurement

___________________

2 Online dataset access and results query systems that are led or sponsored by the federal government include (1) U.S. General Services Administration’s Technology Transformation Services (federal independent agency)—performance.gov and data.gov; (2) CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control—Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (https://wisqars.cdc.gov); (3) HRSA Maternal and Child Health Bureau’s National Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health—Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (https://childhealthdata.org); (4) CDC—Underlying Causes of Death Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (https://wonder.cdc.gov); (5) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)—Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/dataquerytools.jsp); (6) AHRQ—Online Data Tools for the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/data_tools.jsp); (7) CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics—National Health Interview Survey Interactive Data System (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/shs.htm); (8) CMS—Medicaid Child Core Performance Measures Data and Reporting Resources (https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/performance-measurement/adult-and-child-health-care-quality-measures/childrens-health-carequality-measures/index.html); (9) HRSA—Title V Information System (https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov); (10) CDC—Healthy People 2030 Data (https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectivesand-data/leading-health-indicators); (11) OMB’s FCFS (2023a)—America’s Children report and data (https://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren).

Initiative [CAHMI], n.d.c).3 These comments on overall measurement of child health do not take into account the complexity of assigning accountability to specific health care systems for children.

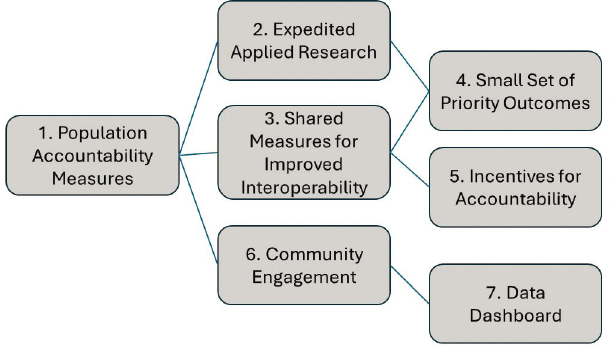

MEASUREMENT AND ACCOUNTABILITY STRATEGY FOR CHILD HEALTH CARE SYSTEM TRANSFORMATION

The success of any plan for a transformed health care system for children will rely on the effectiveness of the measurement and accountability methods employed. Such methods likely will need to build upon existing measurement and accountability system assets but add consideration of child population health, health equity, community engagement, and alignment with other child-serving sectors. Building on the findings outlined in the previous chapters on the science of child and youth development; the role of families, children, youth, and communities in the health care system; the strengths and challenges of the design of the current system; and the financing mechanism for the health care and public health systems, this section identifies seven priority areas for implementing an accountability measurement strategy that supports transformations in the child health care systems to improve outcomes for children and youth (see Figure 9-1):

- Commit to population accountability measures, including health equity, for child health care systems.

- Expedite applied research on best practices for including new measures of child and youth wellbeing in real-world settings.

- Accelerate accountability through shared measures and improved digital health integration and data interoperability across systems and sectors.

- Reduce accountability measurement demands to a small set of priority outcomes.

- Provide sufficient leverage to incentivize accountability for child and youth wellbeing for health care systems and health plans.

- Ensure engagement, transparency, and equity with patients, families, and communities.

- Employ a data dashboard for tracking child health care system transformation goals.

___________________

3 In 2018, the MCH MRN released a national strategic measurement agenda, created in partnership with families, providers, program leaders, policy makers, and experts (CAHMI, 2018). The work engaged network partners to advance the availability of measures on positive and relational health, such as child flourishing, family resilience, and connection; positive childhood experiences (Bethell, Gombojav, & Whittaker, 2019; Bethell, Jones et al., 2019); school readiness (Ghandour et al., 2018); and whole child and family measures of social determinants of health (Bruner et al., 2018). Network partners also sought to advance methods for using available data for local area estimation and to better track disparities; promote equity; and drive integrated, whole child health care systems (e.g., Integrated Child Risk Index; Bethell, Blackwell et al., 2022).

SOURCE: Generated by the committee.

Priority Area 1: Population Accountability Measures

Accountability for health care systems has been limited mainly to persons cared for within a given system, without consideration of access barriers to health care or broader community health. In response, recommendations for including community or population measures for adults have been advanced in reports by expert panels (National Academy of Medicine [NAM], 2023; National Academies, 2023a). These reports emphasized the need for measures of whole person and whole population health to include community indicators for improving health equity and the health of the nation. “Whole health” approaches call for measures that reflect community health and functioning outside of the health care settings, especially for individuals from historically marginalized communities. Examples of whole person and whole population health measures that community stakeholders could adopt include monitoring rates of maternal or infant mortality, suicide, and educational attainment, as well as self-reported health status or patient-reported outcomes. The key to such measures is that they reflect health goals as defined by the community and that health care system metrics are reoriented to monitor community needs adequately (NAM, 2023).

Efforts to Advance Population Health Measures

The growing momentum around accountability for population health is present in the general health care system, with various plans and institutions adopting some form of population health management, either for

place-based initiatives or for covered lives in insured plans. For example, Adventist Health Systems’ Blue Zones initiative seeks to create healthy communities through investment in general wellbeing initiatives that have to do with built spaces, walkability, and nature (Blue Zones, 2019). In one case study, the Fort Worth, Texas, Blue Zone tracked overall community health indicators and moved from one of the least healthy to most healthy cities in a 10-year period (Blue Zones, 2019). A more modest approach focused on place-based improvement is the Community Assisted Public Goods Investment, which tracks broad community indicators of wellbeing that vary based on the goals of specific communities in their five-city effort (Nichols & Taylor, 2018). Several of the cities demonstrated improvements over the first 4 years of their investments in a focused community good.

Relatedly, non-place-based innovations have been employed by health plans across large insured populations. The advent of large-scale Medicare Advantage plans, accountable care organizations, and large Medicaid managed care contracts has sparked greater interest in population-level measures for “captured” or insured populations across different communities (Slabaugh et al., 2017). Among proposed new summary measures are total “healthy days” and more detailed measures that assess (in aggregate) disability days, self-reported quality of life, and others (Kottke et al., 2016). Unfortunately, these measures have been employed only for insured persons, not entire communities, and emphasize adult health, health behaviors, and perceptions of wellness. Similar measures to drive child health care systems to improve child and youth wellbeing are needed.

Multisector regional improvement collaboratives have also led to the inclusion of population health measures in accountability systems, and as a result, these have seen improvements in some population health indicators, such as infant mortality rate and middle school absenteeism in specific communities (Balfanz & Byrnes, 2018; Bundshuh, Ohlson, & Swanson, 2021; Cotton et al., 2019; Hirai et al., 2018; Young, Connolly Sollose, & Carey, 2020). In many of these collaboratives, health care systems provide facilitation, funding, and intervention roles in partnership with multiple non–health care sectors to identify and support shared child health goals (NAM, 2023).

As discussed in Chapter 7, collaboration between primary care and public health has particular importance for improving child health and wellbeing (Valaitis et al., 2020). Several examples of local collaborations have achieved improvements in care in both the United States and Canada (Martin-Misener et al., 2012; McVicar et al., 2019). Nevertheless, considerable barriers limit relationships between the two sectors; chief among them is the lack of shared goals or measures (Pratt et al., 2018). Successful partnerships stem from shared measures at the community level and leadership in achieving trust and commitment among partners.

Overall, a few communities, health plans, and health care systems have included community health indicators and health equity measures, but these are exceptions and not the norm. Several barriers limit incorporating community health indicators, including equity measures, into health care system accountability. First, fee-for-service payments at the clinician level remain the dominant form of payment, providing little incentive to change practice or take on new accountability (Gratale, Viveiros, & Boyer, 2022). Second, adding more accountability measures to the lengthy list of existing measures required by various payers and accreditation organizations will be met with marked resistance, along with increasing demand to simplify the number of measures (see the discussion of Priority Area 4). Third, health care systems often report being ill equipped to address community health indicators that will require them to interface with other human-service sectors to solve complex problems (Gratale et al., 2020).

Health Equity Measures

Despite the barriers, some measures will have to focus on health equity and disparities in community health if there is to be any hope of true progress in societal health for the United States (World Health Organization, 2019). The National Quality Forum (2017) notes the lack of progress in the implementation of equity measures in the United States, even though these measures will be essential to reducing inequities. This reflects in part many technical problems and a lack of consensus on methods for health care system accountability metrics for child health equity and disparities.4 While national, state, and some local data sources are publicly available and produce data on child health equity, equity measures at the level of the health care system are also essential for improving population health indicators because of the stark differences in care provision and outcomes known to exist across systems within the same geographic area, as well as across the same systems operating across different geographies.

Efforts are under way to optimize the use of existing data and measures to provide local areas with child health equity information and to address the challenges involved in specifying separate equity measures that go beyond stratifying results of existing measures for different subgroups based on culture, race, or ethnic group. Some authors have proposed alternatives

___________________

4 Concerns include cost of and methods for collecting data that identify specific cultural, racial, or ethnic groups; choice of specific groupings for historically marginalized populations for equity measurement; decisions about trend over time or absolute values for equity measures; and calculations about magnitude of improvement goals for equity measures that may require culturally specific interventions.

to specific equity measures, including calculating specific attributable risk scores for some neighborhoods or communities with concentrations of historically marginalized persons, in order to focus resources on areas most impacted by inequities (Dover & Belon, 2019; Martino et al., 2023). Until federal leadership emerges to shape and advance data on impactful equity measures, separate measures of child health equity are not likely to be featured in global health care system accountability, and individual health care systems will be left to create their own measures of equity for care within their walls (Hester, Nickel, & Griffin, 2020).

The new CMS Accelerating All-Payer Health Equity and Development (AHEAD) model, a 2024–2034 initiative, is an advanced set of incentives for states to engage all insurers and plans in improving measured outcomes in a coordinated fashion (CMS, 2023d). AHEAD will require new population-based performance measures that go beyond those included in traditional payer–required performance measurement sets. AHEAD and other related CMS-proposed measures move toward this whole system and whole society approach but do not appear to address child population health. Equally robust efforts to optimize child and youth health and wellbeing are needed with an enhanced focus on children’s health promotion and disease prevention. The recently announced CMS-led Transforming Maternal Health model holds promise and will support states in improving care for pregnant women and their infants throughout the perinatal period, including performance measurement innovations with the full engagement of patients and communities (CMS, 2024j). More efforts like the pregnancy-focused Transforming Maternal Health model are called for to catalyze state efforts to transform the child health care system.

Unifying Population Health Measures

In response to the need for a succinct set of measures that could be employed for assessing whole system accountability in a transformed health care system, an IOM (2015) report, Vital Signs: Core Metrics for Health and Health Care Progress, recommended greatly simplifying the health care quality and accountability measurement landscape to focus on a few domains, with 15 total core measures to be shared by all payers, geographies, and health care systems, including four prominent measures of community health (Blumenthal & McGinnis, 2015). This report emphasized the role such “unifying” measures would play in a layered accountability system with federal and state agencies, private payers, and large systems uniting around the common core measures, including a few focused on health equity and overall population health, while other accountability measurement would continue in a streamlined

fashion to focus on condition-, sector-, or patient-specific measurement (IOM, 2015). Tennessee became the first state in the country to roll out 12 core measures derived largely from the Vital Signs report, with modifications after public engagement during 2015 and 2016 (Tennessee Department of Health, 2015). The state now coordinates its annual State Health Report with these measures, provides communities recommended interventions for each of the indicators, and maintains a public record of the Vital Signs performance in the state (Tennessee Department of Health, 2023). California endorsed a similar project at the county level, allowing various communities latitude in modifying metrics (National Academies, 2017a).

The Vital Signs report acknowledged its emphasis on adult health care systems and that child health care systems would likely require a parallel set of accountability measures with a focus on indicators of community and population health for local and regional health care systems. Its authors recommended adding specific indicators of population health for child health care system accountability that could eventually include infant mortality, school readiness, middle school absenteeism, and high school graduation rates. Ohio is now engaged in incorporating at least two of these (infant mortality prevention and school absenteeism) into quality improvement work with Medicaid managed care plans across the state (see Box 9-3). Oregon has employed school readiness in a regional improvement effort with its coordinated care organizations for Medicaid for 3 years (Oregon Health Authority, n.d.).

National outcome measures used for the Title V Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant Program, led by HRSA, also feature candidate population child health accountability measures similar to those set forth through the Vital Signs effort—including measures of school readiness, child flourishing, family resilience, and adverse childhood experiences—which are currently available across numerous child subgroups and states using the National Survey of Children’s Health. Use of these Title V measures has been recommended in the EnAct! framework for statewide integrated early childhood health care systems, which was recently set forth as a national model for states (Bethell, Butross et al., 2023; Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, n.d.d; see Box 9-3).

While further demonstrations are needed, there is growing agreement about the value and potential impact of population-based outcomes measures. For example, several measures such as those noted above have been adopted as child population health measures by a large metropolitan county with a partner pediatric health care system for transparent board reporting and attached to executive compensation (Kemper et al., 2020; Phillips, 2020). These measures do not replace all other accountability metrics required by payers, regulators, and others, but community health indicators provide a unifying component to accountability

BOX 9-3

Focusing Measures and Ensuring Health Care System Engagement: The Ohio Department of Medicaid (ODM)

The ODM developed the Outcomes Acceleration for Kids learning network to align parties, reduce measurement burden, increase focus, and intensify incentives to markedly improve outcomes and health equity for children in Ohio. Traditionally, child health care improvement efforts were fielded separately by ODM, Ohio’s children’s hospitals, or pediatric accountable care organizations. In addition, these entities and the contracted Medicaid managed care plans (in which 98.3% of children receiving Medicaid benefits are enrolled) faced more than 40 pediatric quality measures for reporting and improvement for Medicaid. Because these efforts did not achieve the improvements sought, ODM proposed what it believes to be the first learning network composed of a Medicaid agency, managed care plans, children’s hospitals, and accountable care organizations. The learning network, started in late 2022, includes several proposed innovations:

Increased focus with reduced measurement burden. All parties have agreed to a smaller set of measures for improvement efforts, reducing the number from more than 40 to only 6 measures. Participants agreed that such a focus would enable meaningful efforts on each measure.

Alignment of participants and incentives. Previously, ODM contracted with the managed care plans, and each plan contracted individually with each accountable care organization and hospital. Participants felt there was little alignment in penalties and incentives for quality indicators. Through its provider agreement with the Medicaid managed care plans, ODM hopes to support alignment of all incentives and penalties (without specifying amounts or specific partners) toward the specific six measures currently in use. In addition, ODM is endorsing a statewide improvement goal so that all receive their incentives, or none do.

Ensure engagement with sufficient risk. Employing the Quality Withhold component of its provider agreement with the Medicaid managed care plans, ODM will withhold 3% of all capitation payments for achievement of the child outcome goals on the six measures identified by the end of 3 years and partial achievement during the intervening years. Where the plans have contracts with pediatric accountable care organizations, these incentives will be shared for achieving improvements (or failing to do so).

Incorporate measures of community health in addition to quality of personal health care. Two measures from the National Academy of Medicine report Child Vital Signs—infant mortality rate and school absenteeism—are slated for inclusion in the coming years as long-term metrics for the learning network (IOM, 2015).

and could replace numerous process-oriented metrics going forward. As discussed above, at least two states (Ohio and Oregon) have launched pilot programs providing significant withholdings and incentives for Medicaid managed care plans serving children to achieve specific measures in school readiness or school absenteeism as appropriate goals for accountability and improvement efforts. Further, a majority of state

Medicaid medical directors responding to surveys or focus groups said they were committed to moving toward population health goals in their plans (Chisolm et al., 2019).

Priority Area 2: Expedited Applied Research

In addition to the population health and health equity measures, wellbeing measures have not been adequately captured in proposed accountability systems. Whole child measures that integrate information about a child’s physical, mental, and functional health and their social and relational health, as well as family-centered measures, are available (Bethell, Blackwell et al., 2022; Bethell, Garner et al., 2022) and draw on already available national and state data. For example, the Title V Block Grant National Outcomes measures include positive health and functioning measures, such as school readiness, child flourishing, school engagement, and family resilience (Bethell, Gombojav, & Whitaker, 2019). The Title V Block Grant National Outcomes measures endorsed these concepts in efforts to include positive health and functioning measures, such as school readiness, child flourishing, school engagement, and family resilience (Bethell, Gombojav, & Whitaker, 2019). Whether these measures can be used for accountability of individual health care systems or networks will depend on the feasibility of scalable and reliable data collection and better evidence on how health care strategies influence these outcomes, including partnerships with public health, social services, and community-based resources.

Ongoing research is under way in the field to evolve new measures that may expand the options for health care accountability focused on child and youth wellbeing. For example, the Global Developmental Potential (GDP2) measurement concept suggests a wellbeing index that includes measures related to living a healthy life, having basic human needs met, being able to express and understand thoughts and feelings, engaging in lifelong learning, being able to adapt to change in a positive way, and experiencing positive relationships with and connecting with others (Halfon et al., 2022). While conceptually promising, GDP2 has not been specified clearly or normed for children and youth, nor has it been tested in sufficiently sized populations or compared with other indicators—thus its use cannot be recommended at this time.

Different from the GDP2 approach, some researchers and health care system leaders have suggested a measure of child thriving that includes a more proximal set of process and outcome measures designed to drive health care improvement over several years. This proposal features a composite measure of “thriving” at age 66 months using data easily accessible in current electronic health records (EHRs; Brown et al., 2020). This includes whether a child has up-to-date immunizations and a healthy body mass index; is free of dental pain; has normal or corrected vision and

normal or corrected hearing; and is on track for communication, literacy, and socioemotional milestones. Baseline rates of thriving in one study employing this indicator were 13%, but data were missing for 50% of children, pointing to the seriousness of gaps in data from EHRs. Unless or until access, comprehensiveness, and data transparency problems for EHRs are resolved, measures that depend on health care system records alone will be missing large amounts of data (Brown et al., 2020). Approaches to integrate patient- and family-reported data into EHRs using family-engaged approaches have been tested for impact and feasibility, but they rely on digital health technologies that are in limited use in pediatric health care and generally not prioritized in the broader health care system (Brykman & Joseph, 2024; Coker et al., 2016; Jenssen et al., 2022; Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology [ONC], 2023; Weinberg et al., 2021).

Another proposed community measure is the Child and Adolescent Thriving Index, an aggregate of several community child health and functioning indicators (Anderson, Hemez, & Kreider, 2022). This index includes 11 components: non–low birth weight in neonates, preschool attendance in children ages 3–4 years, reading proficiency in fourth-grade students, math proficiency in eighth-grade students, food security in children younger than age 18 years, general health status, nonobesity in high school students, nonsmoking and non–marijuana use in adolescents ages 12–17 years, high school graduation in young adults ages 18–21 years, and nonarrest in children ages 10–17 years. This is the broadest of the reviewed community indicators and may be farthest from measured influence of health care systems. In addition, it includes some functional measures, such as educational attendance and performance, but does not include positive health and wellbeing.

Priority Area 3: Shared Measures for Improved Interoperability

Many of the children with the greatest health risks and morbidity burdens in the health care system are challenged in dealing with multiple health care providers in diverse settings and are often also served by home visiting, early intervention, child welfare, juvenile justice, schools, special education, and other community-based organizations. Achieving the best results will require coordinated efforts both within the health care system and across various sectors to improve outcomes.

Improving Data Interoperability

Among health care settings, some progress has occurred in improving collaboration between different providers through data sharing and

interoperability to improve health care processes.5 Several new digital health technology innovations and data interoperability platforms and tools are emerging, although few have advanced beyond research and demonstration, and most focus on adult health care and interfacility data interoperability, rather than children or on sharing data across health care, school, public health, and social services settings (Canfell et al., 2022; ONC, 2020; Weinberg et al., 2021; Willis et al., 2022). Especially relevant to child wellbeing, current data interoperability efforts pay less attention to the integration of patient- and family-generated data (Anoshiravani et al., 2011; Bode et al., 2023; Ranade-Kharkar et al., 2018; Sinha et al., 2023). Nearly all hospitals and many physicians’ offices use EHRs (National Academies, 2018). However, because of lack of data interoperability across EHRs and poor capacity to integrate information across multiple sources, devices, and organizations, EHRs are still largely unable to support the flow of essential data at the right time, to the right party, and for the right patient, even within the health care system alone. This is especially the case in child health care.

Although ONC notes the importance of pediatric health care applications, the field is characterized by slow progress and insufficient prioritization of pediatrics or child health data integration on the part of existing health care systems (Anoshiravani et al., 2011; ONC, 2020; Sinha et al., 2023). Child health data work has trailed work for adult health data for several reasons. Governance of child health data remains fraught, with child and parental rights sometimes in conflict, both because of sensitive areas of care for adolescents and because of the potential for child custody issues with child protective services and juvenile justice information sharing. The market for software development is smaller for pediatric software than for corresponding work among adults.

Work on child health data interoperability has also lagged without federal champions. For older people, Medicare has served such a role. Medicare has documented positive outcomes for the older population with long-standing programs, such as the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly, which provides comprehensive health care and social services in community and home settings and relies on effective data interoperability capacities (Arku et al., 2022). Others experiment with new technologies to serve the massive Medicare and Medicare Advantage markets. Child health care, however, relies heavily on Medicaid, with varying state rules and regulations and a more decentralized market. Although CMS (2020)

___________________

5 A 2018 National Academies report defines “data interoperability” as the ability to deliver data seamlessly and automatically across time and space from and to multiple devices and organizations (National Academies, 2018; Pronovost et al., 2018).

continues to issue rules and supports to help state Medicaid programs implement effective data sharing and interoperability strategies and ONC (2020) similarly works to improve the collection, use, and sharing of data important for promoting health and delivering high-quality care, numerous gaps remain in uptake, leadership, and resources for children.

Health Information Exchanges and Exchange Portal

Health information exchanges in numerous regions of the country link diverse health care providers into a shared electronic record summary system for managing patients, even though none of these was designed with children in mind. They are often divided into three types: directed, query-based, and consumer-mediated exchanges (ONC, n.d.; Williams et al., 2012). Directed exchanges develop digital care coordination plans and integrated patient and provider reminders for managing health conditions. Query-based exchanges allow providers to investigate patient data for unplanned health care decision making. Consumer-mediated exchanges provide patient access directly to their own data. While individual EHR platforms almost always offer patient portals, these are not often user friendly and rarely allow an integrated view of all the community providers a patient or family might use. Nor do they usually offer two-way permission by families and patients for data sharing among various providers. Nonetheless, exchanges have reduced emergency room visits, improved medication reconciliation, and reduced diagnostic testing duplication for adults (GAO, 2023a). Health information exchanges have less impact for small and rural providers (Bloomrosen & Berner, 2023) and have not been shown to affect care for children. Exchange portals can capture a broader set of records for diverse participating providers who do not share a common EHR when most health care organizations in a region participate, and these networks could be expanded to include child health services provided in clinical, home, and community settings. For example, rural behavioral health home providers in Appalachia use a health information exchange to coordinate rapid responses to pediatric emergency room visits for children with psychiatric problems, to communicate with primary care clinicians around medications with parental permission, and to evaluate the effectiveness of their services (Zupkovich, 2022). This is especially important for children and adolescents with special needs who seek care at large pediatric health care systems, but also typically require an array of other home-, community-, and school-based services and support. Coordinating the launch of health information exchange with social risk screening and tracking of community services is also likely to lead to marked improvements in the effectiveness of social risk screening (Zupkovich, 2022).

Research Collaboratives

Additional examples for exchanging important health-related information in secure and meaningful ways are emerging from large research collaboratives such as PEDSnet (n.d.), an integrated network of large children’s hospitals sharing EHRs for care improvement for 10 million children, representing approximately 10% of all U.S. children. PEDSnet has already provided highly precise estimates to improve Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) growth curves for children and enhanced estimates of care for numerous conditions. More importantly, they represent a larger portion of children with special pediatric conditions. For example, they may be providing data on most gene therapy received by children and adolescents in the United States and more than 80% of all specialty orthopedic hardware for some craniofacial conditions (PEDSnet, n.d.). Recognizing the potential to transform health care, the new strategic plan for PEDSnet calls for the development of a collaborative improvement network structure for enhancing outcomes for children with rare conditions. The coordinated governance, shared human-subjects protection, standard data protocols, and ability to conduct privacy-protected linkages with external datasets (such as child welfare or education) exemplify some of the first tools that will allow long-term health improvements in a coordinated fashion across multiple large child health care systems. Others emphasize the importance of integrating other digital health technology with EHRs, noting that

A new, more effective EHR will transition away from simply supporting clinical transactions and documenting patient’s medical record to an EHR that delivers key information to clinical and patient and other groups within or outside the health care system with a focus on improved child health. (p. 2) [. . .] EHRs as electronic hubs could act as office extenders, facilitating integration across health care settings, linking patients with community partners, and supporting direct patient engagement [. . .] (p. 5) (Jenssen et al., 2022)

Other recent reports emphasize the need for further expansion to address social factors in EHRs, especially for those children covered by Medicaid. Examples from data sharing for older people across diverse health and social service sectors already exist (Association for Community Affiliated Plans, 2020), but these required significant resources from Medicare Advantage plans for startup.

Cross-Sector Coordination

These previous examples describe mainly integration of data within various levels of the health care system, with little cross-sector work, which

is a more complex effort that requires data interoperability between health care and, for example, schools, juvenile justice facilities, and foster care. Efforts such as the federal Collective Impact Project led by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation delineate the needs, opportunities, and strategies essential to coordinate efforts for promoting the healthy development and wellbeing of children (ASPE, n.d.). Nonetheless, while many child health care and other health-related systems already share important performance measurement topics, in most cases the specifications for these measures are not the same, and shared measures related to the health of the whole child or community are missing. Use of common data platforms across diverse health care systems and child-serving agencies, with which information about children and youth can be standardized and shared, would support better measurement for accountability and help advance the integrated, team-based care needed to promote whole child wellbeing. An example of a tool that supports these goals in the area of early childhood preventive services is the Well Visit Planner, designed to enable an integrated early childhood health care system in the EnAct! framework (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, n.d.b, n.d.d; Center for Healthcare Strategies [CHCS], 2022; Coker et al., 2016).

Several institutions have made significant inroads in collaborating with multisector data. The Ohio departments of Medicaid and of Health have developed data dashboards and virtual networks to engage clinicians and communities in efforts previously around improving child antipsychotic drug prescriptions and are developing new dashboards around infant mortality, maternal mortality, and sickle cell care (Ohio Department of Health, 2020). Some justice facilities have enabled access to hardwired, integrated EHRs for youth detained in regional facilities (Aalsma et al., 2019). Similarly, mandated foster care assessments can now be incorporated into the EHR for some patients in a large metropolitan county. Data interoperability was noted as a key success factor in cross-sector work between primary care and public health in prior initiatives, even though few of them have supported or focused on children outside of immunization efforts (McVicar et al., 2019).

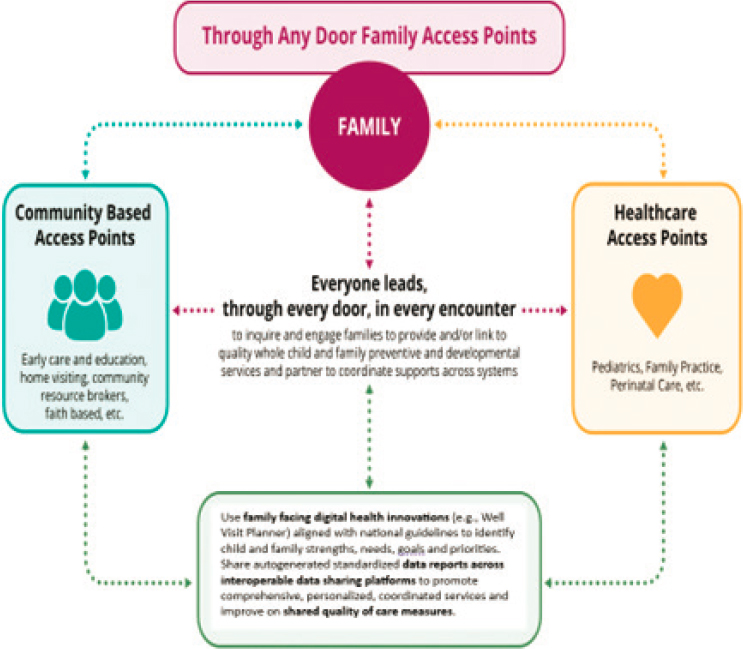

While these examples are important, a broader approach is needed. The national EnAct! framework provides an option for statewide integrated early childhood health care systems with a focus on shared accountability and interoperable, family-engaged data sharing among health care, social services, education, public health programs, and family- and community-based services (see Figure 9-2 and Box 9-4 for a summary of the EnAct! framework’s shared accountability approach). Drawing from similar frameworks focused on adults, such as the Framework for Aligning Sectors, led by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (n.d.), the EnAct! framework is specified for the unique goals, needs, measures, programs, policies, and

SOURCE: CAHMI, 2023.

players essential for transforming the child health care system (Bethell, Butross et al., 2023; Bethell, Oppenheim et al., 2023). Other frameworks, including the Payment for Progress model, led by the Children’s Hospital Association and AcademyHealth, advance engagement across sectors with shared measurement and data interoperability to improve child and family health and wellbeing (Bethell et al., 2018).

Interoperable data sharing is widely recognized as an essential capacity in health care (CMS, 2024c; Szarfman et al., 2022), and platforms need to extend to collaborate among health care, public health, social services, and community support so as to ensure the real-time sharing of family-, child-, and youth-reported information across multiple health care providers and systems, in order to improve child health outcomes.

BOX 9-4

The Engagement in Action Framework

The 5-year Mississippi Thrive! Child Health and Development Project was charged to “yield a model for other States to utilize in improving child health and development outcomes among diverse populations” by aligning efforts between health care and other early childhood systems, including early intervention; home visiting; community-based resources and supports; child welfare; early care and education; Head Start; and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. The model EnAct! is built on decades of work and progress in the field and is novel in its emphasis on the critical role of the child health care system in promoting the healthy development and school readiness of young children, as well as in its integration and specificity of policies, approaches to team-based care, and strategies for aligning outcome and performance measures and accountability mechanisms across system partners that focus on positive health outcomes and equity; what is more, the framework includes an implementation roadmap.

EnAct! emphasizes engagement of families “through any door” and delineates pathways for each early childhood system partner to improve on performance and accountability measures for which they are already held accountable by federal and state agencies, such as well-child visit rates, developmental and caregiver depression screening, and reductions in emergency department use and injury-related hospitalizations. The design of EnAct! was informed by data made available by the Health Resources and Services Administration to all states; these data cover school readiness; child flourishing; family resilience; children’s physical, mental, developmental, social, and relational health; and systems performance and quality of care.

Anchored in principles of family engagement, EnAct! details high-leverage opportunities and specific measurement, collaboration, care design, and policy strategies that enable system partners to integrate services and ensure that all young children receive recommended well-child care services aligned with national Bright Futures guidelines. Using the Cycle of Engagement theory of change, early childhood system partners engaged in the design of EnAct! identified and set forth strategies for meeting four criteria for effective collaboration related to measurement and accountability:

Criterion 1: Use of family-engaged, integrated, and personalized whole child and family standardized assessments that can be implemented “through any door” across an array of care team members and community partners (e.g., clinicians, family support, home visiting, community health, social work professionals).

Criterion 2: Interoperable and automated scoring and reporting of whole child and family assessments, with live links to resources to support partnering with families and coordinating with community and system partners.

Criterion 3: A data sharing platform for ensuring real-time coordination of care and minimizing duplication of assessment with capacity for integration into existing electronic data platforms.

Criterion 4: Real-time capacity to assess, track, and improve quality of services using shared and valid family-centered measures aligned with national guidelines, EnAct! positive health outcomes measures (e.g., school readiness,

child flourishing, family resilience, equity), and shared performance measures (e.g., well-child visit and developmental screening rates).

Four implementation actions and 12 associated outcomes comprise the EnAct! framework implementation roadmap. These actions address requirements for state and system leadership and infrastructure for supporting a strong coalition to drive system change, a culture that values family engagement and child wellbeing, practice-based implementation learning and technical assistance resources, and policy change. This implementation roadmap is meant as a guide; specific steps must be generated by partners and aligned to the commitment, capacity, and resources available to ensure action and progress.

SOURCE: Bethell, Butross et al., 2023.

Priority Area 4: Small Set of Priority Outcomes

Focusing on a small set of high-priority measures that align closely with the achievement of population health outcomes related to child and youth wellbeing may be more effective and efficient than a large array of measures serving different purposes. Measure reduction can allow greater attention to remaining metrics that are prioritized and reduce administrative and clinical burden. However, when local measure reduction efforts are undertaken to provide greater community input and efficiency, variation across states and communities increases and prevents accountability comparisons. Federal reduction efforts overcome this variation increase by reducing the list of prioritized measures to consider and still maintaining consistency of some metrics. National organizations such as NAM, HRSA, and CMS have a leadership role to play in reducing redundancy and measure creep.

CMS (2023d) is currently working to consolidate and standardize accountability measures to improve performance on a small set of measures for both Medicare and Medicaid. According to CMS (Jacobs et al., 2023):

We—the leaders of many CMS centers—aim to promote high quality, safe, and equitable care. We believe aligning measures to focus provider attention and drive quality improvement and care transformation will catalyze efforts in this area. Since there is tension between measuring all important aspects of quality and reducing measure proliferation, we are proposing a move toward a building-block approach: a ‘universal foundation’ of quality measures that will apply to as many CMS quality-rating and value-based care programs as possible, with additional measures added on, depending on the population or setting. (p. 1)

This effort by CMS is part of a broader national quality strategy that emphasizes prevention, integrated care, and many elements of the vision set forth in this report (see Figure 9-3; CMS, 2023a, 2024b). While current measures of priority outcomes for Medicaid are not yet in place, CMS identified priority areas in which such measures are needed and detailed the types of measures envisioned for each area: (1) person-centered care; (2) equity; (3) safety; (4) affordability and efficiency; (5) chronic conditions; (6) wellness and prevention; (7) seamless care coordination; and (8) behavioral health. Person-reported data and patient and family voices are recognized as critical to these outcomes (CMS, 2023b). Ultimately, it will be critical for Medicaid to incentivize and require reporting of the Meaningful Measures initiative in contracts with the managed care organizations that provide services to over 85% of children enrolled in Medicaid in the United States.

To date, CMS reports that the launch of the Meaningful Measures initiative has reduced the number of Medicare quality measures by 18%, saving more than 3 million hours of time and a projected $128 million. It is unclear how the CMS Meaningful Measures activities will or will not translate from Medicare to Medicaid, the largest insurer of children. Preliminary priority measures (the “universal foundation”) being considered by CMS for children in Medicaid include a subset of those already used in the Medicaid core set of measures that states are required to report on (Jacobs et al., 2023): (1) well-child visits (well-child visits in the first 30 months of life; child and adolescent well-care visits); (2) immunization (childhood immunization status; immunizations for adolescents); (3) weight assessment and

SOURCE: CMS, 2023a.

counseling for nutrition and physical activity for children and adolescents; (4) oral evaluation, dental services; (5) asthma medication ratio (reflects appropriate medication management of asthma); (6) screening for depression and follow-up plan; (7) follow-up after hospitalization for mental illness; (8) follow-up after emergency department visit for substance use; (9) use of first-line psychosocial care for children and adolescents on antipsychotics; (10) follow-up care for children who have been prescribed medication for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; and (11) person-centered care.

Priority Area 5: Incentives for Accountability

Accountability systems are only successful insofar as the measures capture outcomes of importance and sufficient incentives are in place for those with agency to improve those outcomes. Health care financing strategies that link performance on priority performance measures to payment incentives are fundamentally important to drive accountability in the child health care system. Other opportunities to advance accountability include supporting managed care organization and other contracted health care organizations in implementing innovative care delivery and payment strategies with the clinicians and health professionals they employ.

State Medicaid agencies are required to develop and implement a quality strategy for contracted managed care programs to use to advance performance on quality measures and outcomes. State Medicaid agencies are held accountable for these measures and outcomes by CMS (CMS, 2024b). Such strategies are required to be developed in collaboration with stakeholders, including families. Many state Medicaid quality strategies reflect a commitment to prioritize child health through improved health promotion, prevention, and coordinated care strategies, and many emphasize engaging families as partners in care. Further, states are required to report their progress on certain child health care quality metrics each year, and for the past decade or more, state Medicaid programs have lacked improvement on most of these metrics. This calls for new approaches to achieving quality goals (CMS, 2024a; Schiff, Filice, & Chen, 2024) and suggests that incentives for managed care organizations, other health care organizations, and clinicians have been insufficient to catalyze improvement.

Current performance measurement benchmarks, incentives, and reporting strategies have not yet compelled the actions needed to establish high performance on existing child health measures or to advance the essential cross-system partnerships required to engage families and address children’s physical, mental, social, and relational health needs. Numerous reports detail specific strategies Medicaid and other state child health programs can use to leverage managed care organization contracts to improve access and quality of health care services for children and

youth (CMS, 2023b), and to advance integration of services between health care, community services (e.g., home visiting), social services (e.g., child welfare), and other sectors (e.g., housing, education, public safety; Bethell, Oppenheim et al., 2023; Center for Health Care Strategies, 2019b; Johnson & Bruner, 2024).

Another lever for advancing accountability for improving health care system performance for child wellbeing is Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Community Benefit Standards (Lopez, Dhodapkar, & Gross, 2021; Rozier, 2020; Soto, Sicotte, & Motulsky, 2019; see Chapter 7). Since 1954, mandatory Community Benefit Standards reporting has ostensibly held nonprofit hospitals accountable for promoting the health and wellbeing of the community. Specifically, IRS regulations include a requirement to conduct a community health needs assessment at least every 3 years and implement a strategy for meeting the community health needs identified. Numerous resources are available to support the needs assessment process, and the assessments and implementation plan are to be made widely available to the public. A recent study, however, found that only 60% of hospitals made the results of their community health needs assessment and implementation plan publicly available (Lopez, Dhodapkar, & Gross, 2021). An average score of 3.2 out of 5 on quality of these plans was assigned to those that were possible to evaluate. The authors suggested many changes to improve hospital accountability and transparency. Even among hospitals that did make their results available, many did not address specific community-identified needs, and because outcomes reporting is not required there were no assessments of interventions’ effect on communities (CHCS, 2019b).

While Community Benefit Standards have not been yet documented as an effective tool for improving population health, their regulations may be an important lever for supporting the promotion of child and youth wellbeing if sufficient incentives, auditing, and performance measurement were implemented. At the same time, Community Benefit Standards only address nonprofit health care systems, and the growing number of for-profit systems do not have a similar oversight mechanism (see Chapter 7).

Priority Area 6: Community Engagement

In the mid-1990s, a large consortium of health care consumer and family organizations, representing about 88 million Americans, advanced a consumer-centered quality measurement and reporting framework and developed measures. Led by the Foundation for Accountability, this effort included collaboration with CMS, the Federal Employees Health Benefits program, numerous Fortune 500 companies and business groups on health, and community groups such as AARP and Family Voices (Skolnick, 1997). As part of this effort and sparked by expectations for the passage of