Advancing Health and Resilience in the Gulf of Mexico Region: A Roadmap for Progress (2023)

Chapter: 3 Addressing Critical Data Gaps in Human Health and Community Resilience in the Gulf Region

3

Addressing Critical Data Gaps in Human Health and Community Resilience in the Gulf Region

Consistent and high-quality data, both specific to and across communities, are critical to assessing and making progress toward improving health and community resilience. In this chapter, the committee attempts to provide perspective on the health of the Gulf region with the available data; historical documentation; and other sources of information, such as the committee’s public hearings and site visits. The objective is to identify and report on gaps

and challenges in these conditions across the Gulf region. Other reports of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine have been helpful for defining indicators of health and resilience (NASEM, 2012, 2015a,b, 2017, 2018, 2019a,b,c, 2020; NRC, 2006, 2011). Similarly, other scholarship suggests a range of variables that contribute to human health and community resilience, particularly in disaster contexts and in places with climate change-related exposures that typify the Gulf states (Chandra et al., 2011; Colten et al., 2012; Goldstein et al., 2011; NCVHS, 2017).

The literature describes a number of variables related to health and resilience, from local social capital among those associated with the community unit of analysis (Acosta and Chandra, 2013; Klinenberg, 2002); to poor or lacking interactions among and information from public health officials (Ferrar et al., 2013); to the overarching quality and resources characterizing health care providers, insurance, and related capacity across primary, mental and behavioral, and environmental health care needs (AHRQ, 2018; Chandra et al., 2011). Indeed, the extant scholarship provides a plethora of relevant variables. However, the committee also sought to categorize and understand the relationships among these variables to better highlight gaps and challenges in the specific context of the Gulf region.

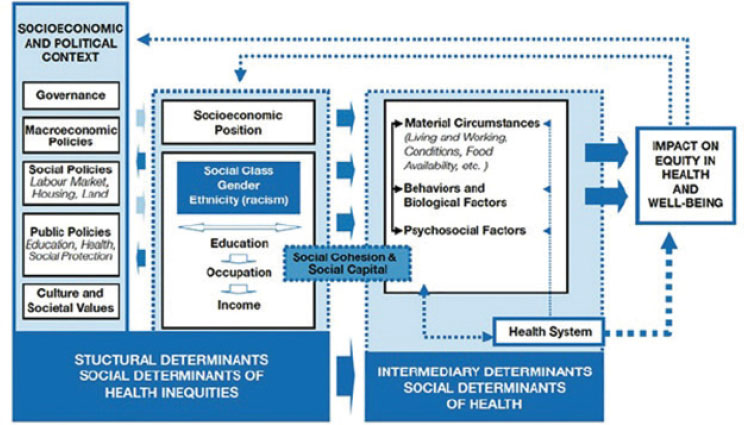

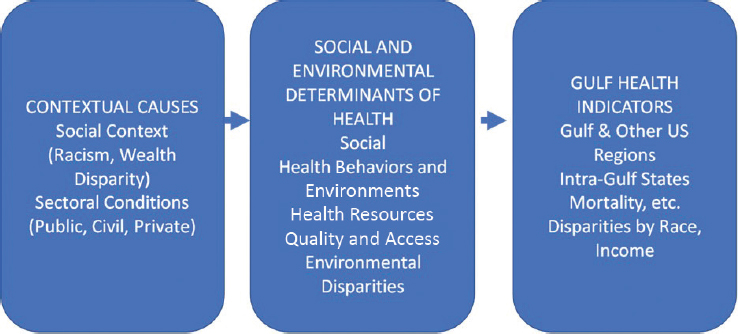

To this end, the committee approached the task of operationalizing the concept of human health and community resilience in three fundamental ways. First, the committee sought explanation. We attempted to trace the relationships among the various factors that define current health and resilience conditions. We relied on scholarship in public health and resilience to trace the likely determinants of gaps and challenges, as well as the underlying social and environmental contextual factors that might explain those determinants more fundamentally. Each of these three general stages—from underlying historical context, to resulting and evolving determinants of health and resilience within that context, to the resulting manifested health and resilience conditions in the Gulf states—helps define a plausible set of relationships among the variables of interest. This chapter addresses these stages in reverse order, starting with current health and resilience conditions, then examining the social and environmental determinants of those conditions, and ending with a description of the fundamental structural context.

The committee makes an important disclaimer regarding this first approach. Our objective with this strategy is not to produce a conclusive and rigorous causal chain or to test the contribution of any one factor or group of factors to health and resilience outcomes. This causal chain provides a useful framework for reviewing the data for the relevant indicators of health resilience only, and the gaps and challenges demonstrated in the framework are further explored in Chapter 4. The committee does not assume that specific social and environmental factors will produce uniform outcomes across Gulf locations. Rather, we categorize the range of variables of interest in accordance with categories established in the current

scholarship on health determinants for purposes of clarity. The purpose of this approach, then, is to present a network of relationships among these variables that can explain, albeit partially, the current health conditions in the Gulf and that may be unique to the Gulf region. We emphasize that the absence of definitive causal relationships across all social and environmental contextual themes, determinants of health, and health indicators is not cause for limiting decision makers or other actors seeking to improve health and resilience in the Gulf.

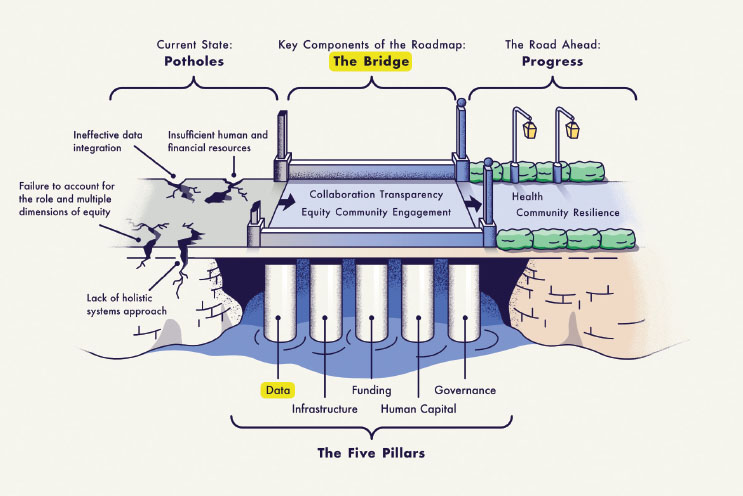

Second, the committee sought measurement. While previous reports of the National Academies have identified key themes and issues related to health and resilience, the committee aimed to identify and quantify these conditions more rigorously and explicitly. The committee used the World Health Organization’s interpretation of the relationship between these themes (Figure 3-1). The goal of this approach was to identify the gaps in health and resilience in the Gulf and calculate the scale of challenges in the region. With normalized data for the entire Gulf region, across the Gulf states, and across subgroups within the states, we believe a review of the current values for the variables of interest will illuminate gaps and challenges more clearly. As part of this effort, the committee commissioned a paper that aggregates consistent and normalized health indicators as they are currently available in the public domain (see Appendix C). The discussion in this chapter refers throughout to the quantitative and qualitative data presented in that multidisciplinary paper.

SOURCE: WHO, 2010.

We assessed the measures for the various health and resilience indicators and contributing factors among the Gulf states, across the Gulf region, and in relation to national averages. We believe such a comparative analysis is critical not only for identifying contemporary disparities between the Gulf region and other parts of the country, but also for identifying which variables along the explanatory chain differ significantly across these geographies. The committee has simplified the relationship schema presented in the World Health Organization (WHO) figure for the purposes of this report and to provide clarity around the uniqueness of the Gulf region (see Figure 3-2). In the case of many of the variables analyzed, the gaps and challenges identified in the Gulf are not unique to that region, and the observations made for areas outside of the Gulf should not be interpreted as optimal conditions or resilience targets. Nonetheless, pinpointing differences in contextual and contributing factors can help in identifying possible structural causes of the health and resilience conditions in the Gulf that we review.

In accordance with the statement of task for this study (see Chapter 1), it is our hope that this articulation of measurable disparities across the gamut of variables contributing to health and resilience will advance the development of specific interventions and recommendations for the region.

THE CURRENT STATE OF HEALTH AND RESILIENCE DATA

Current information regarding health and resilience across the Gulf states is limited by existing data collection and reporting systems both within the states and, for comparative assessments, nationally. The committee reviewed several efforts to measure health and resilience conditions in the United States and to consistently collect data for that purpose. Recent examples, such as the Leading Health Indicators promoted by the

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS’s) Healthy People initiative, have included attempts to normalize health data for areas across the country (NASEM, 2020). Other national sources are available from HHS (including Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] and the National Institutes of Health), the U.S. Census Bureau, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). On the whole, these data sources focus on a single health condition or issue; are infrequently longitudinal; often are not disaggregated by subgroup, such as race/ethnicity, age, or income; may be self-reported; and/or may not be accessible at a level of granularity that allows for geographic analysis (IOM, 2015b).

There are some international resiliency scales as well, such as the National Resilience Scale (NR-13) and the Children’s Revised Impact of Events Scale (CRIES), which surveys youth to determine the effects of events such as war (Kimhi and Eshel, 2019; Perrin et al., 2005), but these scales, too, are subject to the aforementioned limitations. These limitations constrain the assessment of current health and resilience everywhere, but particularly in the Gulf. The paucity of measures for national disaster resilience in databases focused on children and adolescents is especially problematic since it is during late childhood and adolescence when resiliency becomes a critical component of development.

Availability, Accuracy, and Accessibility of State Health Data

An alternative to nationally comparable data is the data generated by the states themselves that could be normalized in some fashion. Unfortunately, the quality of granular health data within states, and especially the five Gulf states, is generally poor. Some common sources of statewide data are the respective state departments of public health, often through a center for health statistics; Medicaid agencies; hospital data; state departments of education; cancer registries; and law enforcement agencies. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), established by CDC in 1984, is the world’s largest ongoing telephone health survey system, tracking health conditions and risk behaviors in the United States annually. It is a state-based system of health surveys that collects information on health risk behaviors, preventive health practices, and health care access related primarily to chronic disease and injury.

For Alabama, the BRFSS is the only available source of timely, accurate data on health-related behaviors. Used by the Alabama Department of Public Health, the BRFSS provides state-specific information about such issues as diabetes, health care access, alcohol use, hypertension, obesity, cancer screening, nutrition and physical activity, tobacco use, and more. Researchers and federal, state, and local health officials use this information to track health risks, identify emerging problems, prevent disease, and

improve treatment. Other states may have different measured public health concerns. Unfortunately, state data are often plagued by some of the same methodological constraints and limitations as those seen in national data, including nonstandard measurement across surveys, different measured objectives per agency, differing definitions, limited access to and engagement of diverse populations, lack of comprehensive measurements of the social determinants of health, inattention to a life-course model and equity, and the inability to perform subgroup analyses. Methodological problems and challenges persist with health data reporting, aggregation, normalizing, and presentation at the federal, state, and local levels (Commonwealth Fund Commission, 2022).

Finding: Major data gaps exist within and across Gulf states for variables related to health and health-related community resilience. These gaps limit the ability to monitor health and resilience conditions comprehensively and to identify gaps and challenges in Gulf health both quantitatively and rigorously.

Resilience Measures

Resilience refers to the process of overcoming the negative effects of risk exposure, coping successfully with traumatic experiences, and avoiding the negative trajectories associated with risks (Garmezy et al., 1984; Luthar et al., 2000; Masten and Powell, 2003; Rutter, 1985; Werner, 1992). Key to the concept of resilience is the presence of both risks and promotive factors that either help bring about a positive outcome or reduce or help prevent a negative outcome. Health vulnerabilities are a key factor in the resilience literature, and certain demographic characteristics (including age, particularly youth and the elderly) are of key focus. Resilience theory focuses on risk exposure among adolescents and on understanding healthy development in spite of risk exposure and emphasizes strengths rather than deficits.

The promotive factors that can help youth avoid the negative effects of risks, such as disasters, may be either assets or resources (Beauvais and Oetting, 1999): assets are factors internal to the individual, such as competence, coping skills, and self-efficacy, while resources are external to the individual, such as parental support, adult mentoring, and community organizations that promote positive youth development. The concept of resources emphasizes the social environmental influences on adolescent health and development; helps place resilience theory in an ecological context; and moves away from conceptualizations of resilience as a static, individual trait (Sandler et al., 2003). It also emphasizes that external resources can be a focus of change to help adolescents face risks and prevent negative outcomes.

Adolescents growing up in poverty, for example, are at risk of a number of negative outcomes, including poor academic achievement (Arnold and Doctoroff, 2003; Shumow et al., 1999) and violent behavior (Dornbusch et al., 2001; Edari and McManus, 1998). One approach to understanding why poverty results in negative outcomes is to focus on other deficits to which poverty may be related, such as limited community resources or a lack of parental monitoring. Researchers and practitioners working within a resilience framework recognize that, despite these risks, many adolescents growing up in poverty exhibit positive outcomes. These adolescents may possess any number of promotive factors, such as high levels of self-esteem (Buckner et al., 2003) or the presence of an adult mentor (Zimmerman et al., 2002), which help them avoid the negative outcomes associated with poverty. Using assets or resources to overcome risks demonstrates resilience as a process. Researchers also describe resilience as an outcome when they identify as resilient an adolescent who has successfully overcome exposure to a risk. Some researchers suggest that resilience—avoiding the problems associated with being vulnerable—and vulnerability—increased likelihood of a negative outcome, typically as a result of exposure to risk—are opposite poles on the same continuum (Fergusson et al., 2003). However, this may not always be the case.

A factor can be considered either a risk exposure or an asset or resource depending on its nature and the level of exposure to it. For some constructs, one extreme may be a risk factor, whereas the other extreme may be promotive. Having low self-esteem, for example, may place an adolescent at risk for a number of undesirable outcomes; having high self-esteem, in contrast, may be an asset that can protect youth from negative outcomes associated with risk exposure. For other constructs, opposite poles may simply mean more or less of the construct. For example, the opposite of positive friend influence is not necessarily bad friend influence; rather it may be limited positive influence. Similarly, involvement in extracurricular or community activities may be related to positive outcomes among adolescents, but this does not necessarily mean that failing to participate in such activities should necessarily be considered a risk (O’Flaherty et al., 2022).

Additional issues in measuring resiliency include multiple types and levels of resiliency, such as individual (psychological/stress), family, community, disaster, and health, that are rarely measured simultaneously. Other issues include differences in context, untested suitability of measures across different ethnic or linguistic groups, and minimal incorporation of community engagement and equity in measurement development. Regardless of how it is measured, resiliency is enhanced when the baseline levels of stress, discrimination, and suboptimal social determinants of health are minimized, and access to positive resources is equitable.

Improving Data Collection and Assessment in the Gulf States

Another underlying issue with current processes for collecting health and resilience data in the Gulf has to do with the lack of meaningful and valuable inclusion of the communities in research, data collection, and review. Public participation is

the process by which an organization consults with interested or affected individuals, organizations, and government entities before making a decision. Public participation is a two-way communication and collaborative problem-solving process with the goal of achieving better and more acceptable decisions (Ahmed and Palermo, 2010, p. 1383).

Community engagement, in contrast, is

a process of inclusive participation that supports mutual respect of values, strategies, and actions for authentic partnership of people affiliated with or self-identified by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of the community of focus (Ahmed and Palermo, 2010, p. 1383).

While both approaches can be useful at different junctures, to help ensure that communities derive the most benefit, organizations funding the collection of data on health and community resilience in the Gulf region need to prioritize community engagement over simpler forms of public participation in the research endeavor, helping to ensure that the data collected are fully contextualized—understood and interpreted consistent with the needs and resources of the community. When the development of sustainable partnerships with communities does not occur, not only are communities less willing to engage in future assessment and research efforts, but also researchers lose out on the critical perspectives and insights provided by community members.1

Community-engaged research allows for understanding and contextualizing quantitative data and the associated conditions more explicitly. As a result of previous research and its members’ own information-gathering efforts, the committee concludes that data related to health and resilience can be understood most fully and translated most effectively in the context of the circumstances, social determinants, and life experiences of those individuals and communities being assessed (Cashman et al., 2008).

Community engagement requires identifying or developing partnerships, collaboratives, and coalitions and, importantly, sustaining those arrangements through ongoing support. The entities involved need to be compensated for their participation in research design, data collection, and interpretation of results. Also, it is vital to develop strategies and

___________________

1 A handful of examples in the Gulf have surfaced, for example Communivax (https://www.communivax.org/local-teams).

mechanisms for the translation, distribution, and implementation of the findings of health and resilience research. Plans for the distribution of results need to include directly linking community members, researchers, and relevant policy makers and practitioners to close the loop between the data collection and the policy implications.

To improve and expand the evidence base for health and resilience practices and translate this evidence for practitioners and policy makers, a research agenda specific to disasters and public health emergencies is required in the Gulf. Similar work in other areas include the NASEM Collaborative on Disaster and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Disaster Research Response Program (DR2) Community of Practice.2,3 Community-engaged partnerships can be used to develop research agendas in advance of a disaster that are relevant to—and prioritized by—community members and local practitioners and emergency public health stakeholders. Identifying urgent, new, and targeted research questions in advance of predictably recurrent events, such as tropical storms, allows communities and researchers to work with funders to develop funding opportunity announcements ahead of such events and expedite research after they occur.

Previous studies have urged the development of a coordinated disaster research agenda nationally (NASEM, 2012), and this is equally an imperative regionally in the Gulf. Other stakeholders include CDC; relevant funding agencies; state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) public health agencies; academic researchers; and professional associations. Their involvement is essential to ensure resourcing, coordination, monitoring, and execution of public- and private-sector disaster resilience research.

In addition to the benefits of stronger, more sustainable relationships and collaborations with impacted communities, assessments of health and community resilience in the Gulf region would be improved through increased primary data collection for that specific purpose. Information used for the assessment of health and community resilience often relies on data developed for other purposes. This use of secondary data can limit both the application and translation of research to the specific circumstances or contexts of affected communities. An increased focus on primary data collection specifically for use in assessing health and community resilience in the Gulf region would be one way to help develop a more complete picture for funders, policy makers, and communities. These data would be most useful if granular enough to support geographic analysis across multiple sectors, including environmental, health, education, justice, economic, and political, mapped to the forms of capital—natural, built, social, financial, human, and political—that enhance resilience.

___________________

2 https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/the-action-collaborative-on-disaster-research#sectionPastEvents.

3 https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/programs/disaster/community/index.cfm.

Also essential to develop a complete picture is a combination of individual- and community-level data; neither is sufficient alone to develop a complete picture of a community’s progress toward improved health and resilience. The specific measures to be collected may vary by objective, by community, or by other factors.

The lens through which the concepts of health and resilience are considered also need to be broadened to accord with the definitions presented in Chapter 1. As previously discussed, the committee adopted a health in all domains approach in addressing the development of healthy communities following disasters. Better than measuring employment alone as a determinant of health, for example, is measuring employment with employer-provided benefits. As another example, risks from wildfire smoke and more frequent, extended, and severe extreme heat events can be expected to be felt disproportionately in the Gulf, with significant adverse health consequences. In the face of global climate change and associated risks, resilience metrics addressing the quality of housing specific to these risks, such as home cooling devices that allow for closing windows during smoke events and cooling during extreme heat events, are important, especially in low-income communities that tend to have less access to home air conditioning and indoor air filtration technologies.

Assessment efforts would also benefit from the use of a consistent set of research instruments. The period since Hurricane Katrina has seen the development of a variety of research instruments, community networks, data-sharing infrastructure, and other capacities that support research on the health and resilience of communities in the Gulf region. Communities and researchers have noted, however, that many of these instruments are redundant or do not build effectively on existing tools, which increases the costs and decreases the efficiency of research efforts. Previous research has captured the extent to which “survey fatigue” and similar factors create obstacles to the community engagement and effective partnerships that are so important in assessing the health and resilience of impacted communities.

While the committee does not recommend the adoption of a particular set of instruments for measuring progress toward health and community resilience in the Gulf region, efforts by researchers and research funders to develop a common set of instruments, indicators, tools, and methodologies could contribute to the long-term sustainability of the research enterprise by reducing the resource requirements for research projects and, to some extent, the impacts on communities participating in the research. Efforts in other regions beyond the Gulf as well as preliminary ones at the national level could serve as useful guides (County Health Ranking, 2023; Stoto, 2014; United Health Foundation, 2022).

A challenge is balancing the value of community-engaged, bottom-up assessments that may provide more contextual detail or specificity with the need for consistency. Bottom-up assessments allow communities to derive

localized, specific information with which to improve their health and resilience. However, such assessments are unique to each community, and do not allow for a comparative understanding of gaps, challenges, and successes across states and the Gulf region. While there may certainly be places and circumstances in which the development of new instruments or tools is warranted, the overall research enterprise benefits if the instruments used to gather data advance a broader understanding. To that end, the greatest benefit can be derived if funders of research on health and community resilience in the Gulf region encourage grantees to make use of a common set of measures, and support investment in new measures only when the gap being filled and the value added by a new measure are clearly identified. Consequently, the committee’s data review is limited to data consistently reported across both the Gulf region and the nation.

INDICATORS OF HEALTH IN THE GULF

Data on the indicators of health in the Gulf and their limitations are summarized in the paper commissioned by the committee (see Appendix C). These data focus primarily on adults, as is the case for much of the data collected during disasters. When one looks at health indicators for specific social and demographic groups, disparities in the Gulf states become apparent that are not demonstrated by the aggregate values. The data indicate that African American and Native populations face worse health conditions in the Gulf than outside of the region, as do low-income households. This section highlights health indicators in the Gulf among adolescents, whose resilience is critical to building and maintaining sustainable, resilient communities. Unfortunately, as with adults in the Gulf, significant health differences are seen among adolescents in the Gulf region compared with the nation (Anderson et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2020).

Today’s adolescents struggle with a wide range of health care needs related to a variety of social, economic, and environmental factors. Adolescents in the southern United States generally have worse health status relative to their counterparts in other regions of the country (Anderson et al., 2022). Additionally, youth from poor, marginalized, rural, and educationally and economically disadvantaged backgrounds experience health inequities that yield poorer overall health compared with youth from better-resourced and more advantaged circumstances (Castro-Ramirez et al., 2021; Heard-Garris et al., 2018, 2021; Liu et al., 2019). The South remains the poorest region of the United States, with Louisiana and Mississippi having the highest poverty rates in the nation (Shrider et al., 2021; USDA, 2022), and teens in the Gulf states have higher rates of such health conditions as obesity, adverse reproductive health outcomes, and unmet mental health care needs (Feiss and Pangelinan, 2021; Thompson et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020).

Adolescents and young adults (aged 10–24) made up approximately 19.2 percent of the U.S. population in 2020 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). Behaviors adopted during this developmental period impact not only individuals’ current health status but also their future health outcomes as adults (Sawyer et al., 2012). Annual adolescent well visits foster the adoption or maintenance of healthy habits and behaviors that allow adolescents to better manage chronic conditions and prevent disease. Thus, receipt of an annual preventive well visit is a national performance measure for Title V block grant programs. According to the 2019–2020 National Survey of Children’s Health, approximately 76 percent of U.S. adolescents aged 12–17 had received a preventive medical care visit in the preceding 12 months. Alabama and other states in the South had lower rates—with only 70 percent of adolescents in Alabama and Texas and 65 percent in Mississippi (CAHMI, 2022). Furthermore, some have noted that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in even fewer youth receiving preventive care (Diaz Kane, 2021), including screening and counseling that would allow them to better manage chronic conditions or prevent disease.

Compared with the overall U.S. prevalence of overweight or obesity of 32.1 percent among adolescents (aged 10–17), the prevalence in the Southeast is higher: 36.9 percent in Alabama, 38.4 percent in Mississippi, 37.3 percent in Louisiana, and 32.8 percent in Florida.4 It has been well established that antecedents of adult disease occur in children and adolescents with obesity (Dietz, 1998). Although mortality from COVID-19 has been significantly higher in older adults and adults with chronic underlying conditions, youth with obesity who have contracted the virus have had a higher mortality rate compared with their counterparts with a normal body mass index (Zhang et al., 2020).

The South has consistently ranked among the highest in the nation in adverse sexual and reproductive health outcomes. The southern states continue to experience an HIV/AIDS epidemic of moderate magnitude that contrasts with the experience of other areas of the country (Sullivan et al., 2021). In 2018, 63 percent of new infections occurred among Black individuals living in the South, and between 2010 and 2018, five Gulf state cities in Florida (Orlando and Miami), Louisiana (Baton Rouge and New Orleans), and Mississippi (Jackson) were identified as hotspots with the highest annual diagnosis rates in the country (Sullivan et al., 2021). Southern states consistently rank among the top states with cases of gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis: in 2019, Alabama ranked third for gonorrhea, eighth for chlamydia, and fifteenth for primary and secondary syphilis, with youth aged 15–24 having the highest age-specific rates of gonorrhea and chlamydia

___________________

4 Data from the 2019–2020 National Survey of Children’s Health interactive data query: Child and Family Health Measures; nationwide and each state for comparison; physical, oral health and functional status; overweight or obese. https://www.childhealthdata.org (accessed December 1, 2022).

(CDC, 2021). While the nation has experienced a decline in teen pregnancies and births, Southern states in the Gulf still have among the highest rates of these outcomes nationwide (HHS, 2022). According to the National Center for Health Statistics, Alabama had the fifth-highest teen birth rate in the country, with Louisiana and Mississippi having the highest (NCHS, 2020).

Forty-six percent of Americans will meet the criteria for a diagnosable mental health condition at some time in their life, and the onset of half of all lifetime cases occurs by age 14 (Kessler et al., 2005). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health challenges were the leading cause of disability and poor life outcomes in young people, with one-fifth of adolescents having a diagnosable mental health disorder (Ghandour et al., 2019; Perou et al., 2013). Increases in rates of behavioral problems, anxiety, depression, and suicide were a major concern for adolescents and young adults. In 2019, suicide became the second-leading cause of death for adolescents aged 15–19 (Statista, 2022). According to the 2019 Children’s of Alabama Community Health Needs Assessment and 2020–2022 Implementation Plan, mental health was one of the health issues for adolescents most frequently identified by health care professionals and educators across the state of Alabama (Children’s of Alabama, 2019). In the United States, injuries and deaths caused by firearms among adolescents and young adults surpassed those caused by motor vehicle crashes in 2020 for the first time in history (Goldstick et al., 2022).

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of mental health disorders in the United States increased; symptoms of depression and anxiety doubled for adolescents and young adults during the pandemic (Racine et al., 2021). Emergency room visits for suspected suicide were 50 percent higher for adolescent girls compared with the same period in early 2019 (Yard et al., 2021). The mental health conditions among young people were likely exacerbated by increased stressors and traumatic experiences related to the pandemic, including reduced connections and in-person interactions with friends, social supports, school supports, and community supports, as well as experiences with death and loss, increased race-related violence, political polarization, and gun violence (HHS, 2021). Adolescents most vulnerable to mental health challenges include those living in economically disadvantaged and immigrant households, those experiencing homelessness, those involved in child welfare or juvenile justice systems, those with disabilities, those from racially and ethnically minoritized groups, those identifying as LGBTQ+, and those in rural areas. A study by Reiss (2013) found that, compared with peers of higher socioeconomic status, children and adolescents from socioeconomically disadvantaged areas were two to three times more likely to develop mental health problems.

Relative to their peers, youth who identify as LGBTQ+ are four times more likely to consider suicide, plan for suicide, or attempt suicide. Those who identify as transgender and racially diverse are at even greater risk for mental health concerns, suicide, and high-risk behaviors (e.g., substance

use, self-harm, and sexual risk taking) (Clay, 2018; Reisner et al., 2016; Thoma et al., 2019). The effect of the pandemic on youth likely varies among individuals, but underserved adolescents and young adults, especially those from Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) and LGBTQ+ communities, are disproportionately at risk of experiencing increased social isolation, stress, and trauma related to preexisting social determinants of health exacerbated by the pandemic (Salerno et al., 2020). The pandemic’s exacerbation of mental health conditions for adolescents, and for the entire population, makes resiliency in the face of disaster even more challenging.

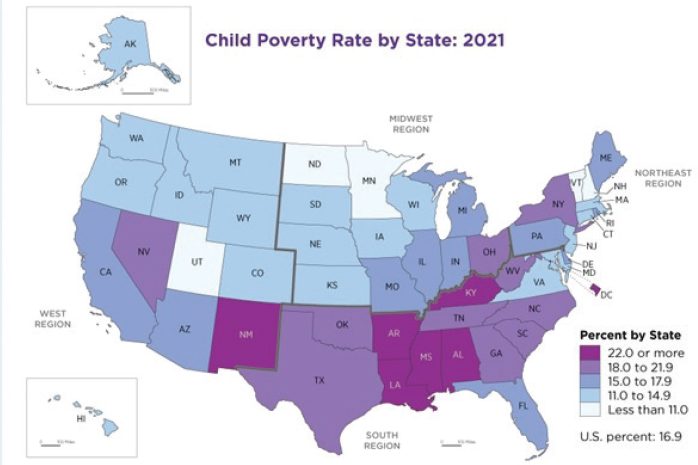

Adolescents in the Gulf region encounter many geographic and socioeconomic obstacles to receiving medical and mental health care. The Southern region remains the poorest region in the nation. According to the 2021 U.S. census, 15.3 percent of U.S. youth lived in poverty; however, 82.4 percent of all U.S. counties with child poverty rates of 40 percent or more were in the South (Creamer et al., 2022; U.S. Census, 2022a). Adolescents in the South often live in rural and resource-poor areas. In Alabama, for example, 55 of the state’s 67 counties are rural. Individuals living in rural areas typically have limited access to primary care physicians and shorter life expectancies (Alabama Public Health, 2007).

The vast majority of Alabama counties are also medically underserved areas with a significant lack of medical and mental health professionals.5 Children in these areas must travel farther for preventive and health services and have fewer options for health care coverage and insurance relative to their counterparts living in other areas. As noted in the commissioned paper, infant and child mortality are also critical factors showing disparities between Gulf states and other regions in the United States. Further, Gulf states that did not expand Medicaid include Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, and Texas; the only Gulf state that did implement Medicaid expansion was Louisiana.

Finding: Where collected data are available, they reveal significant differences in general health status among populations in the Gulf states compared with those in the rest of the nation. Gulf state populations generally have shorter life expectancies and higher rates of infant and maternal mortality, as well as various chronic conditions, compared with those in other parts of the United States.

HEALTH DISPARITIES

Although granular data for the Gulf states are not always available, aggregate data for a few groups across the states do exist, and those data point to stark differences between the health characteristics of specific groups and

___________________

5 Determined using the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Health Professional Shortage Area tool (searching for dental and mental care in all counties in Alabama). https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/shortage-area/hpsa-find (accessed November 16, 2022).

those of their counterparts outside of the Gulf. Disparities and inequities by race, income, geography (e.g., rurality, coastal, other environmental hazard), and other demographic characteristics may be found, but there are also challenges with data on health disparities and tracking by race/ethnicity, income, and other class or social and demographic groupings. These challenges are particularly problematic with respect to the measurement of race.

Finding: When one focuses on health indicators for specific social and demographic groups, disparities in the Gulf states are even more stark than what the aggregate values suggest. African American and Native populations face worse health conditions in the Gulf compared with their counterparts outside of the region, as do low-income households and youth.

DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH AND RESILIENCE IN THE GULF

The current state of individual, household, and community health across the Gulf not only is a challenge to regional resilience but also is symptomatic of gaps in other conditions, systems, and structures. In fact, a preponderance of scholarship over the past half-century has conclusively demonstrated that a range of social and environmental factors can shape health conditions and outcomes as much as if not more than personal or familial epigenetic composition (NASEM, 2016; NRC, 2001; Wilkinson and Marmot, 2003). Once loosely referred to as the social determinants of physical and mental health, the focus of this body of work has been on demonstrating how social structures (such as racism, sexism, and other group-based discrimination) and economic disparities (as reflected in educational attainment, income, and wealth) have shaped a range of biological, behavioral, psychological, and social precursors to disease and poor health (NIMHD, 2017).

In light of this body of work, the committee made a concerted effort to understand the current state of health and resilience in the Gulf through the lens of these social and environmental determinants. The past 2 decades have seen an explosion of frameworks and models for understanding health outcomes through that lens, impelled by the same impetus that motivated the work of this committee: to understand the drivers of health and the disparities therein and to inform guidance for addressing them. A brief review of the evolution of this work is particularly instructive for the committee’s work on the Gulf.

Broad improvements in life expectancies observed with urban planning that enhanced access to clean water, sanitation, and better living conditions have been far more commonly attributed to these environmental factors than to advances in medical care or access during the same period (Grundy, 2005). This perspective does not discount the role of direct medical care and personal epigenetics in health outcomes; rather, a social and environmental determinants approach is inclusive of these more immediate

determinants and allows for a broader view of the factors and pathways that shape health and resilience in the Gulf, as elsewhere.

Research on childhood lead exposure serves as an example of the deepening understanding of the powerful effect of social and environmental determinants on health. Initial work focused on simple associations between disadvantaged neighborhoods with greater lead exposure and anemia (Malik et al., 2022). Later, scholars explored the difference between short causal chains, such as that between lead exposure and anemia, and longer causal chains, such as that between childhood lead exposure and cognitive stunting, educational performance, graduation rates, and thus income (Searle et al., 2014). This work then evolved into studies of latent or later-term consequences, such as the effect of childhood lead exposure on adult health behaviors and mental health (Albores-Garcia et al., 2021). Recent research has even shown that childhood lead exposure may alter the personal epigenetics of the brain, leading to heightened risk for Alzheimer’s dementia (Eid and Zawia, 2016). This progression in scholarship is repeated across an array of social and environmental determinants of health, revealing their powerful influence.

Yet even the relatively straightforward causal pathways between the material environment and health outcomes outlined above have given way to more nuanced and complex understandings of the dynamics that drive differences in health outcomes. These differences are neither simple (more money can purchase better environs and medical care) nor dichotomous (poverty leads to bad health, and lack of poverty allows good health). This scholarship has revealed that a wider array of social factors, such as education, racial marginalization, and lack of social support, equate to the death rate from leading pathophysiological causes of disease, such as heart attack, stroke, and lung cancer (Galea et al., 2011). It has also revealed influences from the home environment, community, and society on various health behaviors, from smoking and alcohol to violence and trauma (Bingenheimer et al., 2005; Pollack et al., 2005).

Exploring these linkages reveals the effect of these social determinants on stress and the resulting allostatic load, leading to adverse health outcomes (McEwen, 2022). Emerging research has pushed the envelope and brought full circle the understanding of the role of social determinants (class, status, social hierarchy, stress) in health, from regulation of stress hormones that affect inflammation and learning; to epigenetics that regulate which genes are expressed or not, influencing immune response; to the telomeres on the ends of chromosomes that protect against damage and are related to life expectancy (Evans et al., 2021; Price et al., 2013).

Finally, the effects of these determinants on health outcomes exist along a gradient, with individuals having greater wealth, education, and/or social status enjoying better health than those in the next group in the economic or social hierarchy and so on, rather than constituting a simple threshold preventing good health (Braveman and Gottlieb, 2014). This observation

suggests a graded relationship whereby differences along these determinants influence health outcomes throughout society and present opportunities to affect health outcomes for all, not just one group, a perspective that accords well with the committee’s mandate.

It is not lost on the committee that these differences in health outcomes are consequences along multifactorial and interacting pathways that are complex and not easily interrogated. Current scholarship has evolved along with these investigations into disparities, probing these causal pathways to reveal the larger conditions, structures, and systems that influence health. These explorations have led to the current frameworks cited above, and grounding this report, that explain social and environmental determinants of health. They encompass the identified structural influences highlighting a socioeconomic and political context that includes governance, macroeconomic, social, and public policies along with cultural and social values that can influence education, employment opportunities, and income and define social position and status, which in turn determine an individual’s material living environment and psychosocial stress, as well as health care quality and access (NASEM, 2016; WHO, 2010).

At the same time, these frameworks necessitate a look at the processes that shape the way public policies and practices are fashioned to create health disparities, which WHO states is a function of the distribution of money, power, and resources (WHO, 2008). Research on health equity has highlighted the historical and current structural roots of these health disparities along causal pathways and the institutional racism that has been codified into various public policies or operationalized in the private sector, from housing discrimination to investments in education (Braveman et al., 2022; Williams and Mohammad, 2009). These dynamics are very much relevant to the Gulf region, as they are to any other region of the United States, and can serve as a valuable way to understand health and resilience among and between populations within the Gulf and in comparison with the broader U.S. population. Given this strong evidence base for understanding the current state of health and resilience in the Gulf through the lens of these social and environmental determinants, the committee sought to review the currently available indicators for these factors.

INDICATORS OF HEALTH DETERMINANTS

It is important to consider several factors when using indicators of social and environmental determinants to make assessments, perform comparative analysis, and track progress. First, the various determinants discussed above often lie outside the typical health and health-related data collected within health systems. Several broad surveys of health data have attempted to include indicators for the social determinants of health as well

(e.g., Dover and Belon, 2019; RAND, 2018; WHO, 2008). Even Healthy People has included a set of determinant variables within the categories of economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context (although these are all measured at the national, aggregate level) (NASEM, 2019c; WHO, 2010). Yet in general, the determinants included in these summaries tend to focus on specific household or group characteristics, which leads to the holders of those characteristics being treated in a potentially negative or positive way that, in turn, leads to their disparate health outcomes. This observation accords with an approach to remedying health disparities that focuses on specifically marginalized or disadvantaged groups, as it considers social position (Penman-Aguilar et al., 2016).

More operationally accurate ways to construct an indicator for a health determinant, however, would be measurement of the context, not the characteristic. For example, measures of equitable employment opportunities, biases in the distribution of health care providers, and the quality and affordability of nutritious food would be more appropriate indicators of causal determinants than would group characteristics that fail to represent these contextual factors. As described above, understanding the structural determinants of health is critical as well, including biases in public policies, institutional racism, and quality of governance.

Piecemeal advances have been made in collecting these indicators, such as indices representing housing discrimination at the community level and a multifactorial index representing relative socioeconomic disadvantage (Fede et al., 2011; Mendez et al., 2011). Unfortunately, many of these indicators are not collected routinely or systematically; in other cases, the only metrics available for measuring them may be poor proxies. Even Healthy People uses voter participation to represent civic engagement; yet, it describes a wide variety of forms of civic engagement that are not well measured (NASEM, 2019c). Moreover, voter turnout would be an inappropriate indicator for the important contextual determinant of inclusive or representative governance.

Additionally, as with the case of Healthy People, individual indicators are often measured at the national, aggregate level. Even when available at the subnational level, the measurements often fall along census tracts or by district or municipal boundaries. These various levels of analysis can be appropriate and useful, given that health determinants operate at multiple levels, an important consideration for analysis (Penman-Aguilar et al., 2016). Yet these nongranular metrics can fail to take account of the dynamics operating at the neighborhood level, impeding decision making. Until measures of contextual and structural determinants are available at multiple actionable levels, assessment and tracking of health and resilience in the Gulf will remain a challenging endeavor necessitating reliance on demographic and aggregate proxy metrics. Demographic disparities reflect

the gaps in—and challenges to—health and resilience that the committee sought to identify for the Gulf region.

Finding: Several national datasets, such as the U.S. census’s American Community Survey and American Housing Survey, help fill gaps in available health-related data for the Gulf region. However, these datasets are constructed around demographic variables (such as race and ethnicity, educational attainment, and income and poverty) rather than factors influencing the effect of those conditions on overall health (respective to the examples, racism, inability to navigate health information and resources, or unaffordability of health services). This construction limits the usefulness of these datasets in measuring progress.

Social Determinants

A review of the general demographic composition of the Gulf states from the most recent U.S. census reveals variables that may explain some of the observed health outcomes in the region. In age distribution, the averages among the Gulf states closely mirror the averages of the United Sates in general. These proportions hold true for individual states as well, with the exception of Florida and Texas. Florida has a greater proportion of people over 65, at 20.5 percent, compared with the U.S. average of 16 percent, along with a smaller percentage of youth under 18 (19.9 percent vs. the U.S. average of 22.4 percent). Conversely, Texas has a smaller proportion of people over 65, at 12.5 percent, and a larger percentage of youth, at 34.8 percent. These differences may drive interstate disparities in absolute mortality rates and vulnerability to health hazards, and reflect different family and household compositions.

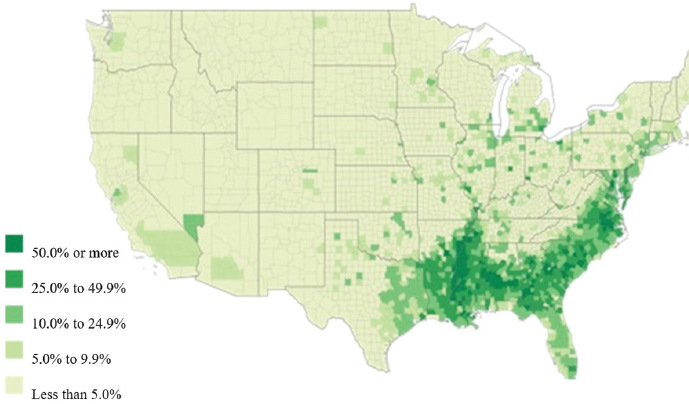

The average racial and ethnic profile of the Gulf states shows a substantial difference from the U.S. average; wide variations are observed as well among the Gulf states themselves (see Appendix C). Most prominently, the Gulf states, representing the South, have double the proportion of individuals identifying as Black or African American, at 24.4 percent, compared with the U.S. average of 14.3 percent (see Figure 3-3). Mississippi and Louisiana have the greatest proportions of this population—36.6 percent and 31.4 percent, respectively—followed by Alabama, at 26.6 percent. While Florida and Texas hew closer to the U.S. average for this population, they have a far greater proportion of Hispanic- or Latino-identifying individuals—at 26.5 and 39.3 percent, respectively—compared with the U.S. average of 18.2 percent.

Income and wealth, important drivers of health, show significant differences within the Gulf states (Figure 3-4; see Appendix C). Apart from Texas, median household income is nearly 18 percent lower among the Gulf states, at $54,175, compared with the U.S. average of $64,994, with Alabama

NOTE: U.S. percent = 14.2.

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau, 2022b.

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau, 2022c.

at a regional low of only $46,511 (almost 30 percent lower than the U.S. average) (see Appendix C). These differences are seen across gender, even in Texas, where both male and female full-time year-round workers earn about 20 percent less than the U.S. average for their counterparts.

This disparity in income between the Gulf states and the U.S. average is mirrored in the rates of poverty across age groups. Among those under age 18, poverty in the Gulf states averages 23.0 percent, compared with the U.S. average of 17.5 percent. As with Black or African American populations, Mississippi and Louisiana again have the highest proportions of youth poverty, at 27.6 and 26.3 percent, respectively (see Appendix C). On this indicator, Florida and Texas are closer to but still higher than the U.S. average, at 17.5 percent. In the common working age group 18–64, poverty rates follow a similar pattern: 15.1 percent across the Gulf states, and 18.2 percent and 17.4 percent, respectively, in Mississippi and Louisiana, compared with the U.S. average of 12.1 percent. And while poverty rates often flatten out among the elderly, this disparity in poverty is sustained even for those over age 65, for whom the average poverty rate is 11.2 percent, compared with the U.S. average of 9.3 percent. These stark, widely distributed, and sustained disparities affect health outcomes and resilience in the Gulf region.

While differences in employment rates are not as great, they show a similar disparity, with all Gulf states except Texas having a lower rate of employment compared with the U.S. average of 59.6 percent. The rate in Mississippi is lowest, at 52.7 percent, followed closely by Alabama, Louisiana, and Florida at 54, 54.9, and 55 percent, respectively (see Appendix C). These smaller differences can be deceptive, however, as they provide no indication of the quality, security, employer-provided benefits, and earnings of that employment, which are better determinants of health.

Educational attainment remains a poor proxy for educational opportunity and affordability. Still, the extant data on this indicator also reveals disparities between the Gulf states and the U.S. average: the percentage of the population in the Gulf states earning a college degree averages 35.6 percent, compared with the U.S. average of 41.5 percent (see Appendix C). Once again, as with racial makeup and income and earnings, Mississippi and Louisiana have the lowest averages on this indicator, at 32.9 and 31.3 percent, respectively. These disparities are even more pronounced at the bachelor’s and graduate or professional degrees.

As with many indicators, representative metrics on the quality of housing, a hallmark health determinant, are lacking. Nonetheless, median gross monthly rents as a representation of local purchasing power and such market factors as desirability are lower across the Gulf states, except Texas and Florida, at a median of $955, compared with the U.S. median of $1,096, dropping to $789 in Mississippi, $811 in Alabama, and $876 in Louisiana (see Appendix C). The percentage of households without internet shows a similar disparity: 14.6 percent for the United States overall, compared with 18.7 percent across the Gulf states and a high of 23.9 percent in Mississippi.

The patterns and disparities in basic demographic, income, and housing variables accord with extensive research showing their correlations with poor health outcomes, helping to explain the current state of health and resilience in the Gulf region. Demographic research has shown that elderly and Black residents of the Gulf Coast are less resilient to hurricanes, with fewer capacities and avenues for migrating away from vulnerable areas (Logan et al., 2016). Many studies of disasters in the Gulf substantiate the role of race and residential segregation in the observed disparities in health and resilience immediately following and long after a disaster (Adeola and Picou, 2012; Toldson et al., 2011; Weden et al., 2021).

In Texas, an analysis of social, economic, and geographic vulnerability found that low-income elderly people and people of color were the most vulnerable population groups before and after Hurricane Harvey (Bodenreider et al., 2019). In Louisiana, structural racism and social environmental risks have been linked to health outcomes as disparate as adverse pregnancy outcomes and COVID-19 mortality, demonstrating the breadth of the effect of race on key health metrics in the Gulf region (Hu et al., 2022; Lopez-Littleton and Sampson, 2020). Like race and residential segregation, education and income have long been correlated with health disparities in the Gulf states, including in the committee’s data review. The correlation between poverty and food insecurity and its spatial distribution have been well documented in rural Mississippi and the Mississippi Delta (Hossfeld et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2021).

Finally, while there is a paucity of regionally specific rigorous research on housing as a determinant of health within the Gulf region, the evidence on this relationship is definitive, making housing a key consideration for population health (WHO, 2018). The health risks from poor housing are not strictly environmental with respect to such hazards as lead and mold exposure, poor ventilation and indoor pollutants, and high indoor heat or cold exposure. They also encompass the physical, social, and economic environment of the neighborhood, from rates of crime and violence to the adequacy of green spaces, quality of food vendors, accessibility of public transportation, recreation resources, and even school quality (Diez Roux, 2001; Egerter et al., 2011; Galea et al., 2020; Kelleher et al., 2018; Kirkpatrick Johnson et al., 2016). Affordable housing itself represents a determinant of health, with substandard housing and overcrowded residences being correlated with higher cost burdens for heating, cooling, and medical care (Diez Roux, 2001; Galea et al., 2020; Kirkpatrick Johnson et al., 2016). In the Gulf region, all these effects of poor housing on health could be better understood through dedicated research.

Finding: Substantial disparities exist in the current status of the social determinants of health between the Gulf states and other regions of the country. While these disparities do not necessarily predict differences in health outcomes, their persistent magnitude

suggests a likely relationship between these variables and the presence and severity of adverse health conditions. Higher-fidelity and consistent data collection within the Gulf region, especially in the interdisaster period, could help in better understanding the role and significance of these relationships.

Health Behaviors and Choice Environments

As noted earlier, while health behaviors have a more immediate cause- and-effect relationship with health outcomes and resilience relative to the social determinants discussed above, they are clearly shaped by environmental factors. The substantial body of literature cited above shows how social and environment determinants can shape choice environments and health behaviors. As with social determinants, data on health behaviors in the Gulf are lacking in quality and completeness of indicators, but some notable insights still emerge from comparing the U.S. averages for several health behavior metrics with the averages across the Gulf region as well as within individual states. A significantly greater proportion of adults report poor health status in the Gulf states, at 21.1 percent, compared with the proportion among the general U.S. population, at 14.7 percent (see Appendix C). A breakdown by race reveals a more nuanced picture but one that still generally parallels the demographic indicators of social determinants discussed in the previous section.

Black and Hispanic Americans generally report poor health at a rate 40 percent higher than that for White Americans: 19.1 percent and 20 percent, respectively, versus 13.4 percent. The rates are once again highest in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, where reported poor health among White individuals ranges from 16.5 to 18.9 percent, while that among Black individuals is greater than 27 percent. In Florida and Texas, Black individuals report poor health at a rate lower than the U.S. average for Black populations, but their rates are still higher than those of their White counterparts in those two states. Evidence, including BRFSS data, shows that residents of the Gulf Coast have lower self-rated mental and physical health and a greater number of unhealthy days relative to the overall U.S. population (Karaye et al., 2020; Sandifer et al., 2021).

Looking at indicators that may reflect health behaviors, deaths from heart disease among both White and Black individuals within the Gulf states, except for Florida, are higher than the U.S. averages of 170.1 deaths and 228.6 deaths per 100,000 persons, respectively (see Appendix C). Texas hews closest to the U.S. averages but still slightly surpasses them. In all the Gulf states, however, the disparity between Black and White populations persists. This pattern is largely repeated in the rates of antecedent cardiovascular disease among White and Black individuals in the Gulf as compared with their counterparts in the U.S. population, with the exception of Texas and Black individuals in Florida.

Interestingly, the pattern of disparity in cardiovascular disease between White and Black populations is reversed in both the U.S. average and across the Gulf states, with Black individuals recording lower rates of disease. This finding may highlight yet another limitation of the available data in that they do not represent true rates but access to care and diagnosis, whereas the death rates from heart disease tell a truer tale. While deaths from heart disease and cardiovascular disease do not in themselves constitute indicators of health behavior, they are well understood to be partial markers for various harmful health behaviors that lead to cardiovascular-related death, including smoking, poor diet and exercise, alcohol use, and poor care of other related chronic diseases.

Obesity shows a similar profile of health behavior representing poor diet and exercise, but also social and economic determinants, including such variables as access to green spaces, time for recreation, and access to nutritious and affordable food. Rates of obesity mirror the patterns for deaths from heart disease, with Florida falling below U.S. averages among White, Latino, and Black populations and Texas running close to the U.S. averages. The exceptions are Latinos in Texas, whose rate of obesity is higher than that of the U.S. population, and Latinos in Louisiana, who fall just under the rate of obesity for their counterparts in the U.S. average (see Appendix C). Once again, however, the rates of obesity among Latinos and Black individuals in all the Gulf states range higher than those of their White counterparts.

Finally, gun deaths represent both adverse health-related behaviors and the socioeconomic and environmental factors that lead to those behaviors. Rates of mortality attributable to guns are higher in all the Gulf states than the U.S. average with the exception of Florida and for Black individuals in Texas as compared with their counterparts in those states (see Appendix C). Once again, however, Black individuals consistently bear a greater burden of these deaths compared with their White counterparts across the United States and within each Gulf state.

Just as the physical environment of housing can directly affect health outcomes, health behaviors are influenced by society and choice environments. The neighborhood effect noted above can influence food consumption choices, reflecting the preponderance of fast-food, liquor, and convenience stores versus venues offering affordable nutritious options. The options available for public space and recreation likewise can influence exercise and activity behaviors. The prevalence of crime and violence can influence mobility and personal beliefs about violence and experiences of trauma in childhood. It is well recognized that the effect of these societal and environmental influences is mediated by their effect through health behaviors that have direct effects on personal biology and health outcomes (IOM, 2001).

Finding: Health behaviors vary between the Gulf states and the national averages. Health behaviors and beliefs, such as diet and food sources, are understood to inform individual, household, and community health conditions.

Quality of and Access to Health Resources

The most immediate determinant of health—access to quality and affordable health care—shows a similar pattern of disparity between the U.S. average and the Gulf states, the exception being Louisiana, which more closely follows U.S. averages (see Appendix C). A similar racial disparity, however, is seen throughout. While determining the quality of health care indicators is fraught with controversy as well as measurement and reporting challenges, the committee reviewed available indicators of access. Insurance coverage for most people across age groups is lower within the Gulf states after childhood relative to the U.S. average. This change after the age of 18 likely results from two factors: (1) a more robust effort to cover children through state variations on the federal Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) that preserves their coverage in the Gulf states, and (2) the employer-based health insurance system for adults in the United States that results in lower coverage in the Gulf states, for which the data previously reviewed suggest lower rates of secure employment with benefits.

This disparity in coverage is understandably more pronounced among lower-income earners and those with lower levels of education, and it diminishes through higher-income categories and higher levels of education except, unusually, in Florida and Texas, where even higher-income earners—those earning above $75,000 per year—show a disparity in health insurance coverage (see Appendix C). Notably, Louisiana appears to be an outlier, as the only state among the Gulf States to have expanded Medicaid, besting the U.S. averages among those with lower levels of education and lower incomes. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Texas’s rates for the uninsured are near to or often double the average for the United States and its Gulf state counterparts among those with lower levels of education and lower incomes, with a high of 37.9 percent of those without a high school degree and more than half of those earning under $50,000 per year lacking insurance coverage.

Another indicator of health care access that was available to the committee was the proportion of adults reporting not having seen a physician in the past year because of cost. The inclusion of cost as the limiting factor in this metric allows the representation of multiple potential factors influencing the ability to have an annual doctor’s appointment, including income and poverty, cost for travel and provider proximity, ability to miss workdays, and social networks, as well as the quality of health care coverage. The data reviewed reveal that aside from Louisiana, which closely follows U.S. averages for insurance coverage, the Gulf states share a disparity in having seen a health care provider in the past year because of cost burden (see Appendix C). A racial disparity remains consistent throughout this metric as well, with Black individuals showing about a 50 percent greater rate of missing a doctor’s visit relative to their White counterparts.

Latinos fluctuate across the Gulf states on this metric, yet always share a disparity with their White counterparts.

While these metrics are limited, the literature provides evidence showing how health care coverage, access, and quality are compromised in the Gulf states, including the disparities seen within the states. Three of the five states considered in this report (Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas) rank among the bottom ten states for physician density (active physicians per 100,000 population) and in all cases, they are concentrated predominantly in or around urban areas, compounding the deficit of physician coverage for rural and disadvantaged populations (American Association of Medical Colleges, 2021; Machado et al., 2021).

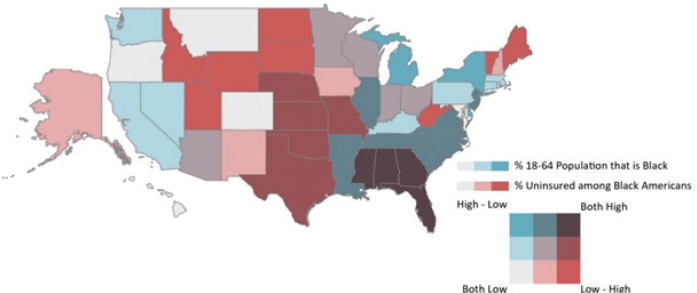

The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) reports that four of the five states considered in this report (Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, and Texas) are among the 12 states that have not expanded Medicaid coverage, with high rates of uninsured who would be newly eligible for coverage; Mississippi and Alabama lead this group with 54.2 and 48.2 percent of uninsured, respectively, being potentially eligible for coverage (Rudich et al., 2022). ASPE goes on to report in a brief that three of the five Gulf states considered in this report (Alabama, Florida, and Mississippi) have the highest combination of a high proportion of both Black individuals in the population and uninsured Black individuals, with the other two states (Louisiana and Texas) close behind (see Figure 3-5) (ASPE, 2022). The limited uniform state-specific study of these coverage and quality metrics prevents deeper analysis.

NOTE: This map uses quantile breaks to distribute data equally across intervals. Breaks are as follows: % of 18–64 adults: Low (0–4 percent), Medium (4–13 percent) High (13–41 percent). % of uninsured who are Black: Low (0–13 percent), Medium (13–18 percent), High (18–33 percent).

SOURCE: ASPE, 2022.

Health care expenditures, although an imperfect proxy, provide another view of health care as a representation of dollars spent. Analysis of data from Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys reinforces the data on racial and ethnic disparities as expenditure disparities between Black and White as well as Latino and White populations. While diminishing at the upper quintiles of income, these disparities still persist, becoming greater as one moves down the economic ladder, and remaining among most education categories as well (Cook and Manning, 2009). More concerning for the U.S. Gulf Coast, medical expenditure following natural disasters in the Gulf depresses health care expenditure for years across the five states considered here, revealing the compromised health and resilience in the region (Horney et al., 2019).

Finding: Access to affordable, quality health care, as mediated through health insurance, the range of health care (including mental health) providers, and other dimensions of the health system, is limited in the Gulf region compared with the rest of the country.

Environmental Determinants

Environmental factors beyond the immediate control of most Gulf residents and distinct from other factors related to social and economic determinants, health behaviors, and health care access help shape the region’s current health conditions and resulting gaps. Many environmental factors, such as exposures to the effects of climate change, directly affect the challenges associated with disaster and climate-related resilience, although it should be noted that many of these health outcomes are indirectly tied to social and economic conditions (such as use of fossil fuels) as well. Environmental conditions are known contributors to individual and community health (Gee and Payne-Sturges, 2004; Jian et al., 2017a).

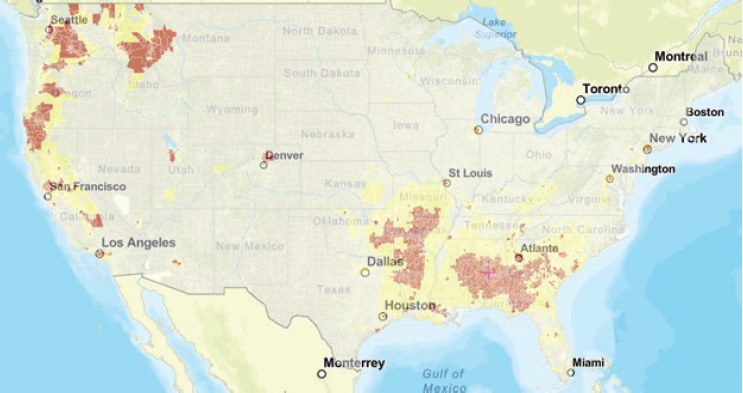

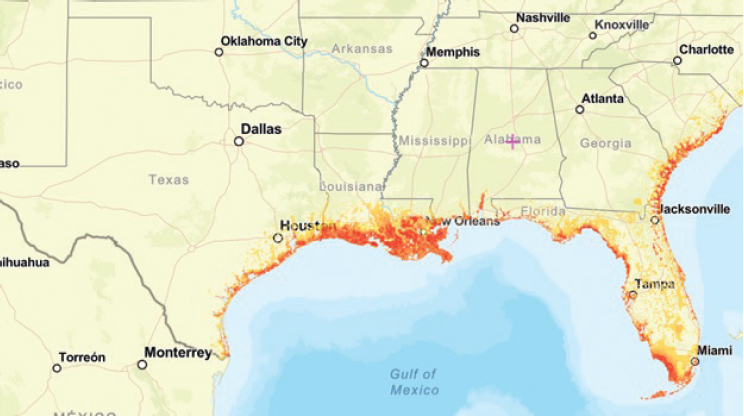

As with many of the other determinants of health, however, consistent and rigorously collected data on environmental factors that affect health are the exception rather than the rule (Lobdell et al., 2014). This gap holds particularly true in the Gulf states, where less stringent environmental rules and less enforcement of the rules that do exist, including those related to local zoning and permitting, subject already vulnerable populations to harmful health effects from environmental hazards. As discussed in the paper commissioned for this study (Appendix C), indicators of environmental hazards and associated conditions, including proximity to point-pollutant sources and air quality indicators, are similar, on average, for the Gulf states and the nation overall. However, the Gulf states do appear to rank higher than other states for certain environmental hazards to health, such as air toxins posing cancer risk and respiratory hazards based on the Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Justice Screening Tool (see Figures 3-6 and 3-7).

NOTES: Red = 95–100 percentile; orange = 90–95 percentile; yellow = 80–90 percentile; gray = 50–80 percentile.

SOURCE: Derived using EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening Tool (Version 2.1). https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/ (accessed November 1, 2022).

NOTES: Red = 95–100 percentile; orange = 90–95 percentile; yellow = 80–90 percentile; gray = 50–80 percentile.

SOURCE: Derived using EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening Tool (Version 2.1). https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/ (accessed November 1, 2022).

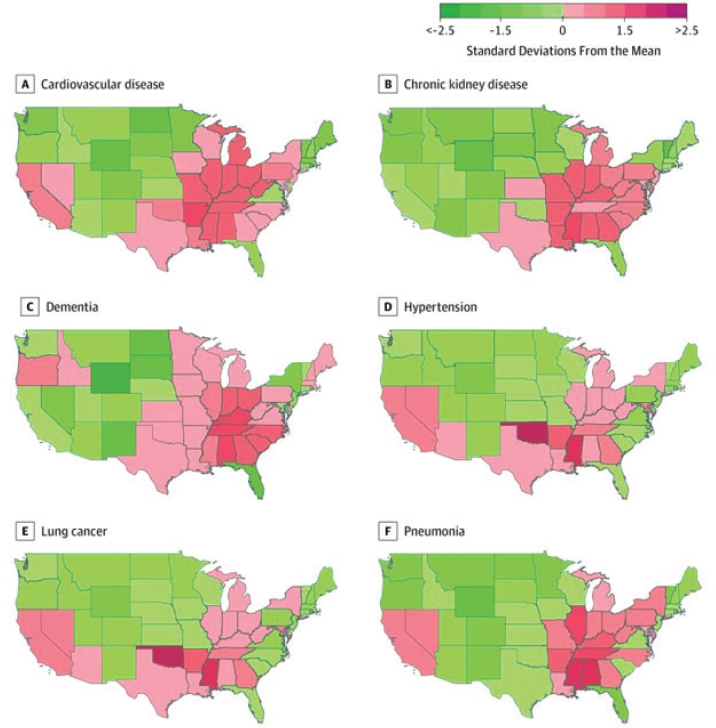

Taking a more granular view, however, the locations of potential environmental hazards tend to be concentrated in specific areas (Ermus, 2018; Meirs and Howarth, 2018; Terrel and St. Julien, 2022; Van Noy, 2021). The Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010, for example, ranks as one of the most acute cases of these concentrated environmental hazards (Kwok et al., 2017). Likewise, Cancer Alley, the infamous corridor of major polluting facilities, lies squarely in the Gulf region (Terrel and St. Julien, 2022) and overlaps with regions across the Gulf states referred to as the Black Belt because of their racial profiles (see Figure 3-3 presented earlier) (Bullard, 2018; Winkler and Flowers, 2017). Indeed, the effects of pollution sources on human health mirror spatially the presence of non-White populations even more so than other household characteristics, such as income. This observation is important. Bowe and colleagues (2019), for example, found that exposure to particulate matter (PM2.5) was associated with mortality from cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, dementia, hypertension, lung cancer, and pneumonia. Deaths occurred disproportionately among Black individuals and those living in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, with Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi being among the most affected states in the nation (see Figure 3-8).

Finding: Several factors paint a precarious environmental health picture for the Gulf states, including the presence of poorly maintained infrastructure, as represented by the ongoing water management crisis in Jackson, Mississippi; poor-quality housing; and the absence or inaccessibility of positive environmental amenities, such as walkable neighborhoods, and comprehensive environmental health protection programs.

Finally, the above industrial and physically direct causes of environmental health hazards are not the sole contributors to the Gulf states’ environmental determinants of health or the disparities seen across racial and income groups. As a warm and coastal region, the Gulf states are environmentally unique in the United States. They are also exposed to unique environmental challenges, especially current and future exposures caused by the effects of climate change. Both chronic and acute hazardous events, including hurricanes, tornadoes, riverine and coastal floods, and heatwaves, are significant shocks to the environments of the Gulf that manifest in similar effects on the health of both humans and ecosystems. Hurricane Katrina, though but one of several such events in recent memory, has become the face of contemporary disparities in the effects of climate-related hazards (Bullard and Wright, 2009). In short, the effects of climate change are felt disproportionately in the Gulf, manifesting in negative health outcomes that include both chronic and acute conditions (Ebi et al., 2018; Harlan and Ruddell, 2011; Watts et al., 2019).

NOTE: Colors indicate a state’s number of standard deviations from the mean for each cause of death.

SOURCE: Bowe et al., 2019.

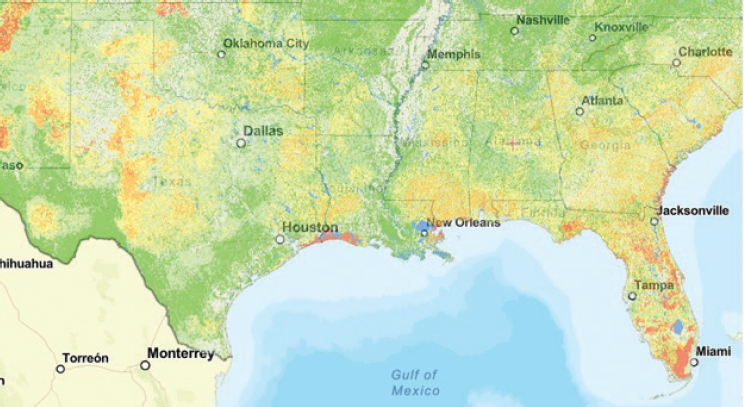

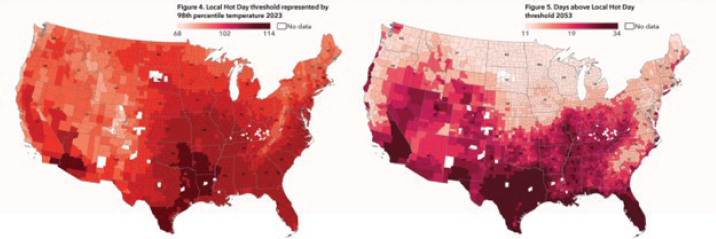

The most commonly reported effect of climate change with severe health consequences for Gulf communities is coastal flooding (see Figure 3-9). However, wildfire risks and heat are also felt disproportionately in the Gulf, with similarly significant health consequences (see Figure 3-10) (Hsiang et al., 2017; USGCRP, 2018).

Heat from rising average temperatures as well as acute heatwaves is the most common outcome of global climate change, and one with particular effects on Gulf communities; the Gulf is among the U.S. regions to be first and hardest hit by this change (Hsiang et al., 2017; Jian et al., 2017b). These environmental conditions result in both direct deaths and other heat-related health

SOURCE: Derived using EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening Tool (Version 2.1). https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/ (accessed November 1, 2022).

SOURCE: Derived using EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening Tool (Version 2.1). https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/ (accessed November 1, 2022).

SOURCE: First Street Foundation, 2022.

effects (EPA, 2017). For example, the rate of hospitalizations from heat stress has been found to be higher in the Gulf states compared with the United States overall (see Appendix C), and projected temperature increases will presumably exacerbate this health hazard (see Figure 3-11) (First Street Foundation, 2022).

In summary, Gulf communities have experienced environmental health hazards over the past century due to industrial pollution. However, these same areas are likely to experience further environmental hazards from the effects of climate change.

Finding: Gulf communities are exposed to more “legacy” environmental hazards and industrial pollutants, often concentrated in places where the hazards are cumulatively greater per capita. Compared with other parts of the nation, the Gulf also faces more shocks, both acute (such as hurricanes and extreme heat events) and chronic (effects of sea-level rise on nonstorm flooding) that endanger human health and community resilience. This pattern holds true for current hazards as well as projected future exposures.