Advancing Health and Resilience in the Gulf of Mexico Region: A Roadmap for Progress (2023)

Chapter: 4 Strengthening the Foundation: Pillars for Progress Toward Health and Community Resilience in the Gulf Region

4

Strengthening the Foundation: Pillars for Progress Toward Health and Community Resilience in the Gulf Region

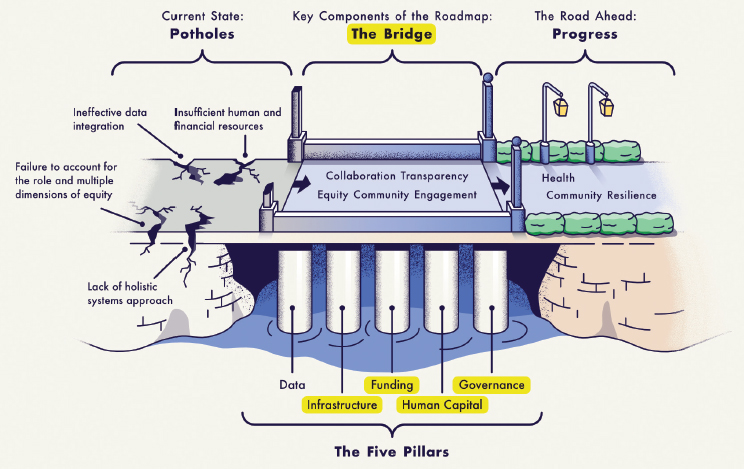

In Chapter 2, the committee identified four interconnected priority gaps that negatively affect health and community resilience in the Gulf region: (1) the appropriate integration of proximal and distal indicators of health; (2) a holistic systems approach; (3) sufficient financial and human resources, effectively charged and coordinated; and (4) failure to take account of the role and multiple dimensions of equity in rendering communities persistently vulnerable. In Chapter 3, the challenges and gaps in health

and community resilience are assessed along three dimensions: data and the lack thereof, the determinants of health and resilience, and contextual causes. In this chapter, the committee uses the structured approach of those earlier chapters as the foundation for discussing how progress can be made toward addressing these gaps and challenges, thereby strengthening health and community resilience in the Gulf region, through the lens of four pillars: infrastructure, including the systems that supports the use and analysis of data; human capital; funding; and governance.

INFRASTRUCTURE

The infrastructure required in a system to support and advance health and community resilience consists of many elements. A starting point is building accessible, equitable, and robust health systems, which encompasses both physical access and hardening of the systems (or infrastructure assets) and the services that flow through them (or infrastructure services). Modernizing public health data to address the gaps noted in Chapter 3 or investing more or different resources into community health and resilience will not be sufficient without continued attention to health systems that can support and act upon those advancements.

For the purposes of this discussion of infrastructure, the improvements required to strengthen health and community resilience must ultimately support a system of health and build resilience into that system over the long term. Stakeholders in the Gulf region underscored to the committee the importance of health system resilience, highlighting persistent issues ranging from basic access to health care and ancillary social services to concerns about the robustness of the physical structures that support health services. Despite greater focus on building “stronger” in the region, inclusive of health care facilities, they expressed concern that those assets remain vulnerable.

A resilient infrastructure is one that is responsive and adaptive and is able to handle a range of shocks and stresses, including the hit of a hurricane or the influx of new community residents because of the changing climate. Will Symons, sustainability director at AECOM, articulated three principles of infrastructure resilience overall: (1) design with resilience in mind; (2) develop risk management that at least considers predictable events such as flooding; and (3) ensure that flexibility and robustness are core design principles, with a focus on building for resilience dividends or cobenefits (meaning realizing multiple benefits of the infrastructure during acute and routine times and/or across sectors or outcomes) (Symons, 2022). This notion of resilience cobenefits has been evolving for some time, particularly in the context of infrastructure resilience. Working for the Rockefeller Foundation, RAND created a Resilience Dividend Valuation Model in 2017 that provided

“a systematic, ‘structural’ framework for assessing resilience interventions that ultimately create benefits and costs within a system, such as a community or city” (Bond et al., 2017).

Despite this recognition of the value of infrastructure resilience, how that approach has been realized in health systems specifically, or a system of health, as cited by McDonald et al. (2020) is relatively new and has not yet reached optimal levels. While community health resilience and health system resilience are two distinct concepts, the resilience of a community relies partially on the resilience of its systems, including its health system. Therefore, efforts to advance health system resilience is a key part of community health resilience.

The World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a review of studies of health system resilience (Fridell et al., 2020) and distilled that body of work into six components of resilience in the health system context:

- leadership and governance,

- information,

- health workforce,

- medical products,

- financing, and

- service delivery.

Finding: Infrastructure improvements are foundational to the development of a health system capable of supporting improved health and building community resilience.

Other sections of this chapter focus on the first three of the above components; this section summarizes findings on the other three. The medical products component generally refers to reducing financial and other impediments to delivery of those products, such as vaccines. In terms of financing, resilient health systems can effectively allocate resources during shocks and stresses, using diverse funding sources to address the ebb and flow of those resources. Further, resilient health systems can address issues of accessibility and equity by maintaining affordable health care services for all, including clinical services as well as social and human services.

With respect to service delivery, resilient health systems can consistently deliver preventive health services before disasters and can ramp up additional services when an acute shock happens while at the same time not reducing routine care (RESYST, 2017). Further, these systems can embrace equity-centered thinking by addressing intersectional issues (e.g., geography and race/ethnicity) for populations being served throughout the life cycle of a disaster.

A recent review on health system resilience during COVID-19 is instructive regarding what improvements are needed to create the right infrastructure to support health and community resilience (Haldane et al., 2021). Using an

adaptation of the WHO framework on health system resilience, the authors examine key infrastructure elements, including health service delivery, community engagement, and public health functions, that matter most for better response. With respect to health service delivery, the authors identify three approaches to building up the infrastructure for delivering services: building new treatment facilities, converting public venues, and reconfiguring existing medical facilities to provide care—in short, maximizing the use of health organizations and using spaces and places to augment health supports. With respect to community engagement, the authors emphasize that meaningful and consistent engagement is essential to improve health service delivery, decision making, and governance for the community, from pre-crisis through recovery.

Finally, the authors note that public health functions are more effective when there is limited to no siloing of public health and health care, particularly in the context of the continuum from contact tracing, to testing, to isolation and/or treatment. Therefore, creating infrastructure that does not create unnecessary barriers and is supportive of the flow of information and resources is critical for health and community resilience.

In an analysis of the European health system response to COVID, Sagan and colleagues (2022) used a four-stage shock model (preparedness, shock onset and alert, shock impact and management, and recovery and learning) to summarize innovations emerging from the pandemic experience that are directly strengthening health systems going forward. These innovations include strategies to effectively coordinate services horizontally and vertically across government, ensuring financial stability in service delivery, embedding mechanisms to rapidly scale the health workforce, and transforming patient care pathways to better integrate health care and social services. While this strategy analysis emerged from the European experience, these provide a road map for U.S. application.

The Malaysia Resilient Health Infrastructure (RHI) program also offers some useful direction for building the infrastructure needed to support health and community resilience that is relevant to the U.S. context. The RHI focuses specifically on strengthening:

- robust building codes and structure, planning and zoning;

- redundancy through planning and operations; and

- rapidity through communication, movement, and risk assessment (Samah, 2018).

Each of these features is identified as critical for hardening the infrastructure to support uninterrupted health service delivery and advance ongoing health and resilience before, during, and after a disaster.

Finally, the U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit (2021) provides useful insights on preparing the physical structures of health care assets. Working with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS),

the initiative developed the Sustainable and Climate Resilient Health Care Facilities Toolkit, which provides information on threats to health care facilities and promising ways to approach those threats. The toolkit identifies five essential elements of health system infrastructure resilience:

- climate risk and vulnerability assessment;

- land use, building design, and regulatory context;

- infrastructure protection and resilience planning;

- essential clinical care services; and

- environmental protection and ecosystem adaptations.

HUMAN CAPITAL

Infrastructure, as described above, is the foundation for successful progress toward human health and community resilience. Building on that foundation, the fuel for progress includes the work of individuals and organizations making a difference in their communities. This section explores the role of human capital—people as individuals and working together through community organizations—in advancing progress on health and community resilience throughout the Gulf region. The discussion here looks at human capital through the following lenses: the critical role of local voices in supporting and sustaining progress, the foundational role and influences of local leadership, and the essential interconnection between the health care workforce and the communities it serves. Explained as well are crosscutting opportunities in human capital. Throughout the discussion, attention is given to the value to be gained by expanding the base of contributors to the work of human health and community resilience in terms of both creating opportunities for connection, collaboration, and investment and ensuring that efforts are responsive to the needs of communities and respectful of their perspectives, experiences, and values.

Local Actors and Voices

There’s no one to help us but us.

—Gary Wiltz, M.D.,

CEO Teche Action Clinics, Franklin, Louisiana

Former Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) administrator James Lee Witt is often credited as the source of the truism “All disasters are local” (Sylves, 2008). Consistent with that statement is the premise that local community voices play a preeminent role in the creation of an equitable systems approach to health. Those community voices gain strength when a broad and diverse range of perspectives is heard and considered.

Based on the committee members’ experience and discussions with community members through information-gathering sessions held for this study (Box 4-1), three approaches appear to characterize successful collaborations between practitioners, government, and academicians and their communities. The first approach is to reach out across the spectrum of citizens, looking past implicit biases about who may be most articulate or

informed about a topic. Citizens may not be policy experts, but they are the most knowledgeable about their concerns and desires. It is also important for public health and emergency management practitioners, as well as public officials, to bear in mind that public meetings are only one place to listen and learn (Ramsbottom et al., 2018); often, reaching out to residents where they are on an everyday basis is most productive.

The second approach is to enlist partners that already have relationships of trust with community members, such as churches, tribal organizations, senior centers, and nonprofit organizations. All of these groups are aware of community culture and history and can serve as effective conduits for community voices. The third approach is to structure and use interactions that provide opportunities for bidirectional learning. Presentations and perspectives of government entities and outside institutions can be informed and enriched by the views and information obtained from citizens. Initiatives built from the ground up with the complete knowledge thus gained will stand the best chance of gaining community buy-in for implementation. The importance of reciprocity in partnerships is recognized and articulated in the academic literature (Bromley et al., 2017) and substantiated by practical experience as a key facet of building participatory public health and resilience approaches that are more sustainable than unidirectional engagements.

Local Leadership

The community has to be in charge of its own recovery because the government always goes home.

—Jane Cage, Chair,

Citizens Advisory Recovery Team (CART), Joplin, Missouri

Local leadership can be an important tool in identifying and mobilizing the resources of a community that can be used in preparing for and responding to disasters (Piltch-Loeb et al., 2022). Local leaders also tend to have relationships of trust with community members that may be lacking with other, more distant, organizations, such as the state or federal government. In addition, leadership of faith-based and community organizations can have the moral authority to help facilitate “cooperative behavior and teamwork, which government lacks” (Patterson et al., 2010). Accordingly, strengthening, supporting, and empowering local leaders can be one way of enhancing community resilience.

In identifying local leaders, the committee encourages a broad-based approach that encompasses local boards and commissions, local chambers of commerce, specialized groups such as workforce commissions, and the leadership of faith-based and community organizations. Local leaders also include the community’s elected and appointed leadership in government, who play a role complementary to that of community leaders outside of government.

The role played by local community leaders, in particular a faith leader, in binding communities together following a disaster is exemplified by Father The Vien Nguyen in the recovery of the community of Vietnamese

Americans in New Orleans East following Hurricane Katrina. Building on the Vietnamese community’s strong social networks forged in part by close religious ties and the shared experiences of being uprooted from their homes during the war in Southeast Asia, members of the community first evacuated and later returned together and had a more successful effort at both rebuilding and engaging with local civic leaders, compared with neighboring Latino and African American communities.

Finding: Local leaders outside of government play a different role from that of a community’s elected and appointed officials, but one that is complementary in efforts to mobilize the community.

In considering who would be included in a “whole of community” response to disasters, Kapucu (2015) offers 26 categories of groups or individuals. In some respects, however, it is important for leaders building coalitions in support of health and community resilience initiatives to bear in mind the concept that to define is to limit. Some ad hoc groups—such as Occupy Sandy, which grew out of the Occupy Wall Street movement, and the Cajun Navy, a group of responders to Hurricane Harvey (Douglas et al., 2018)—can be more effective than more traditional groups in responding to needs on the ground, avoiding the bureaucratic delays and siloed responses commonly cited in reports of disaster response.

Regardless of who specifically are identified as the leaders in a community in building system capacity to support health and community resilience, the injection of resources not only enables service delivery, but also can be dedicated to building and maintaining effective and diverse leadership and can enable the retention of that leadership in communities. As discussed in the section on funding later in this chapter, this includes the importance of ensuring that the space and resources needed for underrepresented community members and insiders to lead are made available. As with the basic functions of the disaster cycle, resilience is the end product of complex interactions and relationships for which the inputs can be neither controlled nor anticipated (Waugh and Streib, 2006). As a result, the most inclusive approach may be the most effective in meeting the needs of communities.

Health Care–Community Connection

In the context of capacity to support human health, the development, resourcing, and maintenance of the health care and public health workforce are especially critical. Just as community organizations and local leaders can best engage community members, the participation of a well-trained, culturally competent, and diverse health care and public health workforce is essential for progress toward better health and resilience in communities.

A number of studies and programs, including several promoted by the federal government, are geared toward increasing the diversity of health care providers as a way of increasing engagement with health care services and reducing health disparities (Jackson and Gracia, 2014). As research cited in Chapter 3 makes clear, however, barriers to engagement and health disparities remain significant throughout the Gulf region.

Research has found that community health workers rate diversity and inclusion as one of their most important competencies in delivering effective patient care, and that greater cultural competency contributes to effective patient engagement and the ability to tailor approaches to patient needs (Covert et al., 2019; Harrison et al., 2019). Along with cultural competency is the need to develop and retain a diverse workforce that is reflective of the community being served. Unfortunately, the diversity of the health care workforce is not growing at the rate it should, or in some cases not growing at all. Research indicates that there were fewer Black medical students in the past decade than in the 1970s, and that the overall growth in the percentage of Black physicians in the workforce over the past 50 years lags far behind what would be expected from population trends (Williams and Cooper, 2019).

Community and technical colleges, along with economic development organizations, may serve as resources to help alter these trends, particularly in the case of community health workers and some allied health professionals. However, more resources still need to be focused on ensuring that a diverse pool of individuals interested in health care and public health careers can pursue those careers and remain in their home communities, should they wish to do so. As the authors of a recent article on reducing racial inequities in health so poignantly state, “It is not enough to just to open the doors of opportunity. Everyone, irrespective of social group or background must have the ability to walk through those doors” (Williams and Cooper, 2019).

Crosscutting Opportunities in Human Capital

Beyond the clear benefits of the approaches focused specifically on local communities, local leadership, and the health care workforce discussed above are a number of crosscutting opportunities. Madrigano and colleagues (2017) offer recommendations for the development of a resilience-oriented workforce for the future, two of which are particularly relevant to the development of human capital for health and community resilience: “create career advancement opportunities that recognize interdisciplinary and intersectoral experience,” and “Establish mechanisms of collaboration across sectors and disciplines.” Recognition of interdisciplinary and intersectoral experience in the workforce acknowledges that career trajectories,

even in structured training environments such as that for health care, can be nonlinear, and that individuals with a variety of experiences may best be able to relate to and connect with a larger cross-section of their communities. In addition, an increased focus on collaboration across sectors and disciplines broadens the base from which both leadership and community participation can be drawn.

Finding: The development of a workforce that can meet future needs in health and community resilience will benefit from building on the broadest possible foundation and creating opportunities to develop and share trust, knowledge, and respect throughout communities and between communities and service providers.

FUNDING

We’ve unfortunately developed a disaster culture, so when disasters hit there’s a money flow, opportunities for inroads to programs to help us try out solutions, but the issue is sustaining those opportunities.

—Lanor Curole, Director,

Vocational Rehabilitation, United Houma Nation, Houma, Louisiana

The pillars of infrastructure, human capital, and governance on which an improved vision for resilience will depend rest on a fourth pillar—the funding needed to support and sustain them. Understanding the flow of funding to support resilience efforts is therefore essential (Mackenbach, 2014). Essential to understanding and rethinking funding mechanisms are awareness of who the funders are and to what and whom those entities direct their financial resources, and recognition of opportunities for improvement or restructuring to better meet the needs (including health needs) of communities working to build effective, proactive, and accountable resilience solutions.

In many ways, a basic question for resilience funders at all levels is why maintain the status quo? Are the current methods, requirements, and restrictions around designated resilience funding working? Has measurable progress been made with a yield of positive outcomes? Are these processes grounded in comprehension and application of the distributive, procedural, and contextual dimensions of equity? Given the gaps and challenges identified in Chapter 3, it appears there are not yet affirmative answers to these questions. The committee proposes that resilience funders consider how communities can use their funding streams to move toward a proactive, transformative stance, instead of simply focusing on restoring what has

been lost. This proposition is supported by previous work reimagining what resilience and the power dynamics surrounding it could be (Cretney and Bond, 2014; DeVerteuil, 2015).

Multiple funders and funding streams currently exist, from the federal to the local level. The breadth and depth of funders and stakeholders has been addressed previously by the National Academies (NASEM, 2019a). The list of funders includes a broad spectrum of philanthropic entities as well, fueled in part by the COVID-19 pandemic. HHS (and its component entities, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], the National Institutes of Health, the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity, and more), are the primary federal funders focused on health. While FEMA is also often recognized, other federal funders include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Energy (DOE), the Department of the Interior, the Economic Development Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Department of Agriculture, and the Federal Transit Administration.

The funding initiatives of these federal entities include grants, cooperative agreements, loans, and technical assistance. For instance, FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities grant program aims to “incentivize natural hazard risk-reduction activities that mitigate risk to public infrastructure and disadvantaged communities” (FEMA, 2022). Other examples include the Economic Development Administration’s Investment for Public Works and Economic Facilities grant program, the Department of Energy’s Weatherization Assistance grant and technical assistance program for low-income households, and the Department of the Interior’s Tribal Resilience grant and technical assistance program.

Block grants are an example of how top-down decisions lead to difficulties at the community level. Block grants are essentially fixed amounts of funding provided by the federal government to enable states to provide benefits or services. The fixed nature of the funding results in an inability to respond to increased need, particularly for under-resourced and economically vulnerable communities. In addition, the inability of the block grant to meet the community’s need often leads to cuts in benefits, increased eligibility restrictions, or the establishment of waiting lists for service. Thus the lack of flexibility in block grant funding presents an ongoing challenge.

One of the most significant issues for federal grant funding is ensuring that the funding reaches community-based organizations that can use it. How are funders ensuring that the relevant organizations, businesses, and institutions are aware of the opportunities being offered? Even if community-based organizations are aware of a funding opportunity, do they possess the capacity within their organization to respond to, receive, and administer the funding? Is the request for proposals (RFP) cumbersome and complicated? Many community-based organizations lack the capacity to identify, apply for, and administer large federal funding packages.

When organizations lack this capacity, the field is significantly narrowed and slanted toward those organizations and institutions that are larger, well resourced, and more experienced. In recognition of the vital role of community-based organizations in the Gulf region and in keeping with previous research calling for a redefinition of granting processes for resilience funding (Acosta et al., 2021), the committee supports the creation of capacity-building assistance units within or external to the funders. These units would provide technical assistance and real-time training and support to grassroots organizations, nonprofits, small resource-challenged institutions, and others. The Century Foundation, for example, is currently using this approach in its Black Maternal Health unit. However, many chief business officers (CBOs) do not have the capacity to identify, apply for, nor administer large federal grant funding packages.

Finding: Teams supported by funding organizations and charged with assisting CBOs in building their capacity to obtain and manage grant funding represent a viable pathway for increased CBO participation in development and delivery of programs to help meet community specific needs.

Philanthropy is another vital source of funding, but if resilience and adaptive programming is to be sustained, these funding streams will have to be approached and constructed in a different manner that makes them agile and responsive to the needs of CBOs before, during, and after a crisis. To this end, five elements of resilient philanthropic strategy have been identified (Lynn et al., 2021). In accordance with this view, funders can find greater success in their funding strategies when they do the following:

- Release control over pathways and outcomes.

- Support networks rather than solutions.

- Address systems and not just symptoms.

- Focus on transformative instead of transactional capacity.

- Align their power to supplement, not supplant.

These elements create space for innovation, systems change, and sustenance and give power and capacity to community partners. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has applied a few of these strategic principles to its grantmaking, with some success.

Previous research has found that funders would benefit from funding the adaptation or creation of systems that can anticipate current and future resilience needs and are nimble enough to reduce the negative effects of a disaster on communities, including those throughout the Gulf region (Chandra, 2021). An example would be placing resilience officers in a position funded

jointly by the local government and public health departments, establishing a long-term position that could guide and evaluate local resilience efforts instead of simply using grant or special initiative funding. In addition, the health assessment process mandated by the Affordable Care Act could be expanded to become a community health improvement process that would track resilience as part of health metrics. Such an effort would entail inviting to the table entities not currently or consistently involved in the process, such as community planners/redevelopment specialists, environmental and water officials, energy and broadband representatives, and others.

Another source of funding for many social service projects that has emerged in the past 20 years is the social impact bond. Through this mechanism, a donor makes an up-front payment to a service organization and signs a contract to be repaid, with interest, on some scale related to the outcomes in which the funded activity results. Usually the bond is repaid by the local government, as, for example, in the recent social impact bonds sold by New York City for the development of affordable housing (Bloomberg, 2022). The use of social impact bonds started in the UK in 2010 and has now spread to 34 different countries, with more than $241 million in projects having been funded (Brookings Institution, 2020). The unique aspect of social impact bonds is that the amount repaid depends on measurable and quantitative indicators of project success. This aspect of the bonds contrasts with many grants, which are based only on the merits of a proposed activity and not on the project outcomes, and this built-in incentivizing monetary feature can be attractive to donors interested in supporting local social service organizations. Projects supported by social impact bonds need to be collaborative between the donor and the recipient organization.

While social impact bonds have desirable features, they do entail several conditions that must be met. The most important is that the organization receiving the funds must be able to collect the data needed to measure the outcomes specified in the contract, which requires both resources and skill in data collection. While many larger organizations have this capacity, many smaller ones do not and would need assistance, as noted in the previous discussion of data in this report. In addition, the writing of contracts and the necessary negotiations require time and effort on the part of leaders of service organizations, another potential challenge. Thus, small organizations are likely to need capacity-building assistance to take advantage of the social impact bond mechanism. In sum, social impact bonds have been used in many countries to support local organizations in carrying out important social service projects and have a number of attractive features to donors, while also posing challenges to recipient organizations.

Finding: Social impact bonds merit more study and exploration in the resilience domain, and local organizations that want to use this funding mechanism need support to do so.

Another source of funding is banks that support local social service organizations with grants for worthy projects. While such grants are sometimes made by local banks, large banks, such as Bank of America and U.S. Bank, have units specifically designed for local CBOs that need funding for a specific activity. As with philanthropic funding, obtaining support from the banking sector is a competitive process, and typically only the largest CBOs with well-trained staff are capable of obtaining this support. To do so, an organization must be able to negotiate grants with individuals at financial institutions whose interests, like those of donors of social impact bonds, are in the specific and measurable outcomes of project and grant funding. Again, small CBOs are likely to need assistance in forming the types of relationships with banks that are needed to make this a fruitful source of funding for them.

Many of the current funding models have attempted to incorporate language and intention around equity and inclusion by requiring grant funding proposals to demonstrate engagement or collaboration with minority serving institutions (MSIs). In the Gulf region, there has been a particular emphasis on “partnership” with historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). Multiple issues have been raised and questions posed about this approach. Is there joint oversight of grant aims and budget allocation? Are the MSI partners in principal or coprincipal investigator roles? What are the staffing and budget support levels for engagement of the designated MSI communities?

MSIs, such as HBCUs, tribal colleges and universities, and Hispanic-serving institutions, are already deeply engaged in community resilience and health equity efforts (Box 4-2). They often have strong, meaningful, and historical ties to their communities and a demonstrated commitment to the amelioration of poor health outcomes through acknowledgment of and direct action on the various determinants of health and resilience as outlined in the previous chapter, even in times of decreased external funding. MSIs bring to these efforts a level of expertise and understanding as well as community connections and support because what they do is not only their “work,” but also their lived experience. MSIs are currently an underused resource as the primary partner for receipt of funding. Changing the status quo to better use this resource would entail directing funding opportunities to MSIs as the primary grant-receiving institution, with the ability to partner with CBOs as well as other academic institutions and partners within their community.

The National Academies’ Gulf Research Program (GRP) serves as an example of directed funding with an intentional focus on MSIs across the Gulf region. The GRP is developing a grant program with funds received from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation that focuses on transforming public health data systems. At this point, HBCUs are the lead institutions targeted through this funding because the funding model specifies that they are the only primary institutions eligible to apply for this funding.

In addition, the GRP Gulf Scholars Program is a 5-year, $12.7 million pilot program designed to prepare undergraduate students to address the most pressing environmental, health, energy, and infrastructure challenges in the Gulf region. The inaugural cohort included students at Florida A&M University, Florida State University, Jackson State University, Rice University, Tulane University, the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Xavier University of Louisiana; up to seven additional colleges/universities will be selected each year through 2025. The GRP aims to have more than 25 public and private universities involved in the Gulf Scholars Program by the time the pilot phase of the program concludes in 2025. The Health and Resilience unit at the GRP targets most of its grant funding toward nonprofit and community-based organizations in the Gulf region while also considering how it can design grants in a manner that will enhance community engagement and build the capacity of community organizations to identify, respond to, and administer GRP funding.

GOVERNANCE

As described in Chapter 2, while the governance of public health systems in the United States can be divided into four broad groupings, the dynamics of the relationships among federal, state, and local authorities are as diverse as the states themselves, according with the nature of federalism in the United States. The promulgation of health regulations and activities

aimed at protecting and promoting public health, and to a large extent supporting community resilience, have traditionally been expressed as a function of the government’s police powers. In the post-9/11 and thereafter the post-Katrina and post-other disaster evaluations, some aspects of the traditional state-centric (as opposed to nation-centric) foundations have been challenged, largely on the basis of interpretations of the federal government’s authority to regulate interstate commerce and provide for national defense, broadly envisioned. However, the courts and Congress have continued to emphasize the role of the states as a central, if not the central, actor in the public health domain. Public health and community resilience policy remains concentrated largely in state capitals and city halls across the United States. Consistent with that, it is important to note that the variations of local autonomy provided by state constitutions or statutes to substate entities (e.g., cities, counties, parishes) can also play a role in assessing where the balance of power lies in a particular state, and whether the state government or local governments individually and collectively are the most substantial actor.

Recent research published in State and Local Government Review suggests that in response to the COVID-19 pandemic state and local government actions, in particular the level of independent action by localities or preemption by the states, were not consistent with previous understandings based on extent of home rule. Additional exploration of this particular area could be helpful in understanding where the primary government actors for health and community resilience activities reside and how best to develop additional community and government engagement.

In addition to viewing governance as the model or structure of government as applied in a particular area, it is helpful to consider governance as the articulation of a shared strategic vision for a particular program. In the context of health and community resilience in the Gulf region, government is often a leading actor because of its role in the funding of programs and the creation of the legal and policy frameworks within which those programs operate. As a result, it is perhaps appropriate that state governments play a leading role in the engagement that develops and articulates that shared vision.

Irrespective of how the governance and oversight structure is assembled in a particular state or locality, there are best practices to be considered in the approach to governance itself. A 2003 Institute of Government white paper attempted to define the role of governance by observing that it exists any time a group of people come together to accomplish an end. It encompasses

the interaction among structures, processes, and traditions that determine how power and responsibilities are exercised, how decisions are taken, and how citizens or other stakeholders have their say. . . . Fundamentally, it is about power, relationships and accountability: who has influence, who decides, and how decision makers are held accountable (Graham et al., 2003).

The white paper highlighted four principles of good governance that are applicable in the present context: a shared vision (as previously discussed), participation, transparency, and accountability. In considering these principles through the lenses of infrastructure, funding, and human capital as discussed earlier in this chapter, it is possible to envision a set of governance principles on which progress toward human health and community resilience in the Gulf region could be built.

The onus for ensuring that the infrastructure needed to support the delivery of health and community resilience services is on state leadership, as either the source or at least the nexus of decision making for the resources available for health and community resilience within a state. With the exception of Texas, which has a largely decentralized model for public health, the Gulf states rely on governance models that range from shared in Georgia and Florida, to centralized in Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana—approaches for which state leadership is key to both the development and communication of shared visions and the articulation of responsive policies.

In looking at the 100 Resilient Cities Initiative, a report on the growing role of chief resilience officers highlighted a need for political commitment across administrations and an ability to coordinate across government departments as critical to the success of a chief resilience officer. Whether identified explicitly as a “chief resilience officer” or not, having an identified senior leader who is able to work in such a crosscutting way can strengthen the accountability of local, and state, governments for resilience efforts.

Several aspects of the forgoing discussion of the role of human capital are critical to understanding the role of effective governance in shaping progress, and the Institute of Government’s framework principles of participation, transparency, and accountability are all linked to the effective inclusion of local voices and actors in efforts to achieve progress toward human health and community resilience. Previous sections of this chapter have emphasized the need for increased participation at the ground level so that engagement with communities around health and resilience can be undertaken in ways and in places that meet the needs and availability of the community. Emphasized as well has been the importance of broad outreach and engagement in identifying community leaders. These same precepts extend as well to the arena of governance and strategic leadership. Data maintained by the National Conference of State Legislatures show that by and large, state legislators are not a significantly diverse group and tend to be older than the communities they represent.

Finding: Success in implementing meaningful health and community resilience programs will depend on the engagement of state legislators and leaders in executive agencies within the Gulf region with a diverse and representative community in developing, shaping, and evaluating health and community resilience programs in their states.

Considerations that may be valuable for purposes of future planning and participation include

- inclusion of people most affected, community leaders, the business community, and the media;

- government’s responsibility for building an interface among government, business, and civil societies at both the state and local levels;

- expansion of who sits at the table to include representatives of community health resources (not just large hospitals), other health care providers, housing, food, education, people most affected at the local level, business, and civil society leaders; and

- wider inclusion and coordination at the top, with a focus on ensuring unity of effort across federal agencies for the benefit of those receiving services.

Bidirectional and broad-based engagement also could contribute to the final key principle of good governance—accountability. Principles articulated in the previous section on funding—expanding the roles of CBOs and philanthropic organizations, breaking down silos around funding for health and community resilience, and increasing the focus on proactive approaches to funding—all contribute to accountability. They do so by increasing the circle of participants; supporting greater involvement of communities and community organizations; and directing resources toward risk assessment, goal setting, and preplanning. All of these measures create opportunities to establish and assess concrete metrics around health and resilience issues, with a particular focus on prevention, that lend themselves to greater accountability for the governance of resilience efforts.

Finding: Programs that contribute to the health and resilience of communities benefit from data-driven, community-engaged approaches, capable of being evaluated, throughout all phases of the disaster cycle.

KEY CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Conclusions

Conclusion 4-1: Government leadership has not consistently ensured that infrastructure supporting community health and resilience is capable of withstanding a range of disaster impacts. Efforts to ensure health infrastructure is capable will likely necessitate collaboration and robust partnership with private-sector organizations, many of which own and operate much of U.S. health care delivery.

Conclusion 4-2: State-level and local-level bottlenecks have consistently limited the flow of resources to communities.

Conclusion 4-3: Building sustainable resilience funding and adaptive programming will be reliant on innovative funding approaches and strategies that supplement vital existing philanthropic resources.

Conclusion 4-4: Federal funders exercise limited oversight to ensure that funding reaches the organizations who most need it in ways they can best use it.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 4-1: Public health and community resilience initiatives should facilitate public participation that is designed around specific community needs and priorities, supports bidirectional learning and engagement, and is, where possible, integrated with existing community resilience activities (e.g., infrastructure resilience plans, community emergency response and recovery plans) consistent with a health in all domains approach.

- State and local leaders should develop public health and community resilience initiatives that facilitate public participation and are designed around specific community needs. Engagement initiatives should support bidirectional learning and engagement.

- Funders should intentionally broaden their outreach to local leaders and facilitate opportunities to engage with nontraditional and non-hierarchical service delivery organizations to identify opportunities for community collaboration and participation in projects.

Recommendation 4-2: Under the leadership of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Federal Emergency Management Agency,1 the federal government should convene key governmental and philanthropic funders of health and community resilience programs to collaboratively develop an interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral strategy to support sustainable funding efforts in the Gulf of Mexico region. The successful development and implementation of this strategy is dependent on both organizational and operational elements.

___________________

1 The committee believes CDC and FEMA are the most appropriate entities to lead on this effort given their leadership of the Public Health Emergency Preparedness and other community health grant programs, and Homeland Security Grant Program grants respectively. However, the intent broadly is that the Department of Homeland Security and HHS collaborate on this effort given the intersection of public health and preparedness grants to state, local, tribal and territorial governments from those departments.

Organizational elements of this strategy include the following:

- Health in all domains: A commitment to a health in all domains approach to funding that aligns with existing activities where possible, and encompasses diverse groups that can contribute to the health and resilience of a community, including health care and mental health care, education, housing, and social infrastructure.

- Transdisciplinary and cross-sectoral efforts: A commitment to supporting transdisciplinary efforts to break down silos and develop a more comprehensive understanding of the successes and needs in health and community resilience in communities. All funders should articulate meaningful requirements for transdisciplinary and cross-sector collaboration in their requests for proposals and should give preference to applicants who can demonstrate specific and meaningful collaboration for their projects.

- Building community capacity: Plans, financed largely by state and local funders of health and community resilience programs, to develop and operationalize foundational capacity among community-based organizations to receive and manage funding from federal and state sources.

- Practical applications: The development of funder portfolios that include research and programmatic efforts focused on practical applications and on impacts of value as identified by the local communities collaborating in the work.

Operational components of this strategy include the development of plans, resources, and measurable milestones focused on the following objectives:

- Shift funding models to facilitate the engagement of and partnership with historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and minority serving institutions (MSIs) so that they are the primary recipients of increased quantities of funding targeted to minority populations with the capabilities to partner with other institutions and organizations, instead of funds being disbursed to groups and institutions with requirements to partner with HBCUs and MSIs.

- Facilitate the creation of funding models and mechanisms that can meet community needs in a more responsive and adaptive manner.

- Facilitate an increased focus on community engagement. The strategy should help funders identify proactive steps for ensuring that transdisciplinary approaches emphasize representation and self-determination by communities.

- Guide the promotion and support of work that identifies future gaps or risks before or in the early stages of disaster impact to communities. Ongoing and future funding opportunities should be developed based on the reevaluation of risks and gaps and the assessment of the incremental and appropriate progress of prior funded efforts.

Recommendation 4-3: State legislators and leaders within executive agencies in state government should prioritize the inclusion of data in policy making and ensure that they are using specific and consistent data to inform decision making around health and community resilience programs. State leadership should also take steps to ensure that the development, operation, and evaluation of such programs include meaningful engagement with community members and leaders, providing opportunities for participation in both state capitals and local communities.

Recommendation 4-4: To best align priorities and resources and derive benefits from a learning system,2 state and local governments should explicitly designate a senior official responsible for health and community resilience efforts, even in cases in which responsibility for those efforts spans multiple offices or agencies.

Given the diversity of government and governance structures present in the Gulf region, as well as the variable needs and capacities of individual communities, the committee has endeavored to keep its conclusions and recommendations sufficiently specific to provide guideposts on a path forward but flexible enough to be tailored to the needs and circumstances of states, localities, and communities.

Some examples of the infrastructure challenges at the heart of Conclusion 4-1, the bottlenecks in Conclusion 4-2, and examples of the community engagement and opportunities for bidirectional learning aspired to in Recommendation 4-1, can be found in Box 4-1.

Similarly, examples of using and strengthening the capacity of CBOs and shifting funding models, as aspired to in Recommendation 4-2, can be found in Box 4-2.

Recommendation 4-3 builds on Recommendation 3-2, and examples of effective data use can be found in the section titled “Improving Data Collection and Assessment in the Gulf States” beginning on page 44.

___________________

2 A learning system in this context is an organization that follows a process of regular, deliberate evaluation and incorporates the findings of those evaluations into policies and programs to guide the next evolution, in this case the response to the next disaster.