Community-Driven Relocation: Recommendations for the U.S. Gulf Coast Region and Beyond (2024)

Chapter: 7 Communication, Participation, and Knowledge

7

Communication, Participation, and Knowledge

This chapter discusses the following:

- The lack of discussion about relocation in the Gulf Coast region of the United States and a distrust of government

- The challenge of communicating the idea of relocation (e.g., terminology, purpose, process, outcomes), including issues of transparency, language, and culture

- Lessons learned from the communication of scientific information around climate change that are relevant to communicating risk in the context of relocation

- Linking of social capital to participation, civic leadership, and power sharing

- Co-production and participatory action research and practice (PARP) as guiding principles for engaging communities about relocation

- Local and Indigenous knowledge in participatory planning, including traditional ecological knowledge (TEK)

INTRODUCTION

Climate adaptation ultimately depends on and profoundly affects people, neighborhoods, and communities, yet they are often left out of processes around problem solving, developing adaptive solutions, and taking collective action (see Box 7-1). There are instrumental methods and tools for organizing and facilitating community-driven relocation processes that can build on existing community capacities and processes of engagement, including the co-production of knowledge and decisions relating to climate action, as well as participatory action approaches to research. Successful climate adaptation necessitates opening new spaces for community engagement in the face of increasing risks from climate change impacts.

Community engagement requires trust building and power sharing through outreach, consultation, involvement, collaboration, and shared leadership in decision making (see Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium; National Institutes of Health, 2011). This chapter discusses some of the key actors and constituencies that need to be engaged and looks in depth at tools of communication, participation, and knowledge-building that support communities’ co-production of their relocation plans, where relocation may be necessary.

BOX 7-1

Community Testimonial: Elder Chief Shirell Parfait-Dardar

“So, when we hear talk of managed retreat, and we’ve seen some of the things that have happened with communities facing resettlement, it’s quite scary because of the examples we have to look at. They do not include the voice of the community. The community is not the one that is guiding these efforts. You don’t see them involved from the start to the completion of the project. And all it does is remind me of how these communities have constantly been forced because someone either thinks that they have a better plan, that they have more knowledge, you know, whatever their agenda is […] The community knows their community, their landscape, and everything, better than any other outsider. So, I think they should be brought to the table to where they could discuss if anything is going to be—any work—done in their community, it should be discussed with the community. So, for anyone that is considering partaking on this managed retreat, managed by whom? If the people that are having to retreat are not the ones guiding, are not the ones determining, if they’re not at the table, then you’re not helping them. You’re simply causing more harm.”

SOURCE: Elder Chief Shirell Parfait-Dardar, Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, and Chair, Louisiana Governor’s Commission on Native Americans. Workshop 3: Community Viability and Environmental Change in Coastal Louisiana, July 2022, Thibodaux, Louisiana.

Chapter Overview and Outline

For effective communication and outreach, the committee heard that messaging has to clearly outline purpose and need for relocation, while providing comprehensive and comprehensible information to potential movers. To alleviate uncertainties, participants noted, it is important to use personalized interactions and provide extensive details about potential receiving communities. Using information that comes from trusted sources and is consistent with other sources makes planning more accessible and understandable to community residents.

There was a general sentiment among workshop participants that government cannot be trusted to support communities—that politicians were not acting on the desires of the communities that they represent because there is a revolving door and discontinuity of government staff at the community interface level—and so the only real leverage is to vote local government out of office. However, many people are unaware of who their local elected officials are, and/or they are politically disengaged (Knight Foundation, 2020; Luchi & Mutter, 2020). When they are recognized, elected officials are often seen as ineffective in helping the communities most in need (Pew Research Center, 2018; Schneider, 2008).

Another theme workshop participants raised that is closely connected to the overarching message of disaffection and distrust toward largely unresponsive governments is the principle that community residents need to lead planning and relocation efforts from the outset, with government “assisting,” not “managing,” relocation. That is, there is the basic need for self-determination. The affected communities need to be involved from the outset in all aspects of planning and the implementation of relocation efforts.

Lastly, workshop participants talked about the lack of resources and the lack of equity in planning and implementing relocation. Residents need adequate and accessible information on future environmental and health risks at both their current locations and at possible future locations, as well as information about the costs of relocation, in order to participate in their own and their community’s futures.

This chapter explores these issues around communication and participation, dividing the work into five sections. The first section considers the relative lack of discussion of relocation in the Gulf region, including the lack of participation by the people most affected and how this can instill a general lack of trust in the government. The second section turns to the broader issue of communication, including risk communication, which is the subject of the chapter’s third section. In the fourth section, we look broadly at participation and knowledge, perhaps the most critical parts of any relocation process. Here, we revisit the idea of social capital canvassed

in Chapter 6 by considering how it is intrinsic to civic leadership, power sharing, and participatory decision making, which are critical elements when planning and implementing community-driven relocation. We then briefly examine the themes of co-production and PARP as guiding principles for engaging communities about relocation, followed by a discussion about the importance of local and Indigenous knowledge in participatory planning.1 The chapter concludes with section five, the committee’s summary and conclusions.

A LACK OF DISCUSSION ABOUT RELOCATION AND A DISTRUST IN GOVERNMENT

Communication is one of several barriers to managed retreat (Bragg et al., 2021; Siders, 2019). There are many ways to confront the situation, and at the core of these are the ways in which people have access to, and can equitably and effectively participate in, relocation and resettlement decisionmaking processes (Climigration Network, 2021). Along the U.S. Gulf Coast, there has been an overall lack of discussion about climate-induced relocation strategies, especially between U.S. Gulf Coast residents who likely will have to relocate and the government entities and nongovernment stakeholders that would need to facilitate relocation, compounded by the fact that existing government frameworks do not include relocation as a viable option. When the topic of relocation (often in the form of buyouts) does arise, there is limited meaningful involvement of U.S. Gulf Coast residents in discussions (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022c). This includes a lack of transparency and communication from the entities managing the buyout programs (National Academies, 2022c).

When efforts are made to engage communities, the mechanisms are not effectively facilitating participation (Gosman & Botchwey, 2013). For example, public meetings are inaccessible for a number of reasons, including being held at inopportune times, not providing child/elder care, and not always using terminology understood by those affected (Bower et al., 2023; Spidalieri & Bennett, 2020d); key documents are often not translated into the primary languages of vulnerable communities (National Academies, 2022c). In addition, community capacity to engage is generally limited (Barra et al., 2020; Hemmerling, Barra et al., 2020) and varies within communities. Moreover, distrust of government can prevent community

___________________

1 As discussed below and defined in the Key Terms (Appendix D), “co-production” in the context of community-driven relocation is the process of developing and implementing knowledge, plans, and strategies through the iterative engagement of at-risk communities, researchers, practitioners, and other groups, whose participation is necessary to the relocation process (see also Armitage et al., 2011; Meadow et al., 2015; Wamsler, 2017).

members from believing the messages they are receiving. As a result of these issues, decisions are made predominantly by people who are not affected by those decisions, and programs are established without understanding or accounting for cultural variability (e.g., large families, community connections, renters; National Academies, 2022c, 2023a).

Consideration of, or planning for, community relocation is not included in required planning exercises for U.S. Gulf Coast communities (i.e., local hazard mitigation plans [HMPs], longer-term comprehensive plans, disaster recovery plans) as there are no federal mandates to do so. The topic is polarizing for any mayor or elected official to take on during a four-year term and is therefore rarely considered as a mitigation solution. In general, if something is not required, then it is often left out of these plans, as local governments have limited time and resources. For example, most local HMPs do not include a commitment to climate adaptation or include mechanisms on how to incorporate new climate data into plan revisions (Stults, 2017). Additionally, HMPs are often developed to meet minimum federal standards rather than serving as a key decision-making tool that includes the identification of specific climate threats and adaptation projects (Berke et al., 2014). Some would also argue that politicians are not talking about relocation due to the economic and political (“blame the messenger”) ramifications of asking people to leave their homes (Teirstein, 2021). In the case of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Superfund program, it has been found that listing of a site on the National Priorities List has resulted in a decline in housing values, which in turn reduces the local tax base, thus fueling opposition to government action (though often values go up again post cleanup; see Chapter 9 for more on EPA Superfund relocations; Kiel & Williams, 2007).

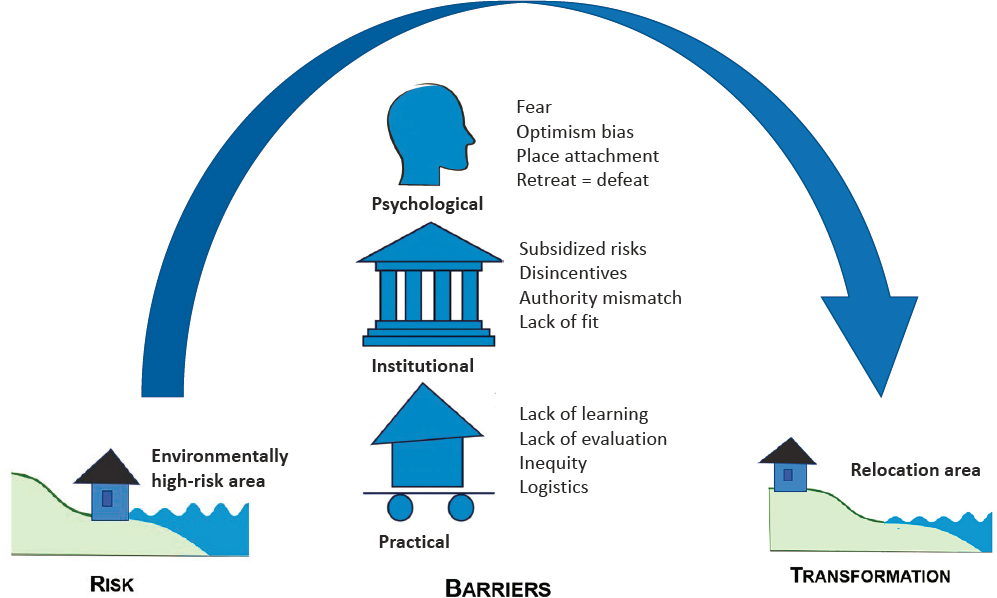

In addition to the committee’s decision to use the term “community-driven relocation,” there have been previous suggestions to rebrand the term “managed retreat” since retreat can be negatively associated with loss of property (Bragg et al., 2021). Notably, effective communication may help to establish relocation as a potentially viable option even if community members have not considered it before. In instances when there may not be direct experience with the forces driving relocation, it may be helpful to provide readily understandable local information about the scale and nature of risks to community members’ livelihoods, well-being, and property (see Figure 7-1). Vandenbeld and MacDonald (2013, p. 166) stress the “importance of ensuring […] emotional support when this information [is] conveyed.”

Distrust of Government

A general distrust of government (Chapters 4 and 5) coupled with a lack of transparency in the process of relocation (including criteria for a buyout) limit residents’ confidence in the need for relocation (see Box 7-2)—residents want to better understand why locations are being singled out for relocation (National Academies, 2022c). Barbara Weckesser, head of Concerned Citizens of Cherokee Subdivision and resident of Pascagoula, Mississippi, spoke of the lack of trust in government officials that can impede relocations: “So we’re trying to pull in and bring in city and county and state [for relocations]. But again, there’s so much mistrust. So how did you build that trust up?”2 The interplay of trust and transparency issues can also result in the residents’ lack of understanding about the government’s specific reason for issuing mandatory relocations. Some groups feel targeted and believe acquired land is not to reduce flood risk but for other vested government interests such as oil extraction or new development for wealthier groups (National Academies, 2022c, 2023a).

During the workshops in Texas (National Academies, 2022c),3 the committee heard from community members that trust issues can be reduced by

- engaging communities through a trusted third party (e.g., community leaders) who has no financial interest in the outcome;

- improving transparency in who is funding the relocation process; and

- communicating to relocating communities on the use of land post-buyout or post-relocation.

Establishing trust between residents and government will enable discussions of relocation in a transparent and two-way context. The next section discusses some of the challenges and opportunities surrounding the broader issue of communication and relocation.

COMMUNICATION

Communicating the idea (e.g., terminology, purpose, process, outcomes) of relocation is a challenge. Residents often have difficulty relating to complex, technical, or larger-scale plans, such as the Louisiana Coastal Master

___________________

2 Comments made to the committee on March 30, 2022, during a virtual public information-gathering session. More information is available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/03-30-2023/virtual-focus-group-mississippi-and-alabama-gulf-coast-community-stakeholder-perspectives-on-managed-retreat

3 Comments made to the committee during the committee-hosted public workshops. More information is available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/managed-retreat-in-the-us-gulf-coast-region#sectionPastEvents

SOURCE: Siders, A. R. (2019). Managed retreat in the United States. One Earth, 1(2), 216–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2019.09.008

BOX 7-2

Community Testimonials: Distrust in Government

Derrick Evans, executive director of Turkey Creek Community Initiatives in Gulfport, Mississippi, and of the coast-wide and grassroots community-focused U.S. Gulf Coast Fund for Community Renewal and Ecological Health (2005–2013), shared his sentiment about lack of trust in government, saying that disaster response has not “been equitable, fair, [or] trustworthy,” and this has to be considered “before you get to relocation.” He later said that “lack of trust in the government is not the problem. Lack of trust is the result of past government behavior.” Casi (KC) Callaway, chief resilience officer, Mobile, Alabama, responded, “Knowing that we’re not trusted is a big challenge. And how do we overcome it? And that’s probably what I want to say [more] than anything else […] we have to be able to provide real and accurate and solid information […] I can’t imagine most of us wanting anything more than that. But if we or the data isn’t not trusted, we gotta fix that.”

SOURCES: Derrick Evans, Executive Director, Turkey Creek Community Initiatives in Gulfport, Mississippi, and Gulf Coast Fund for Community Renewal and Ecological Health (2005–2013) and Casi Callaway, Chief Resilience Officer, Mobile, Alabama. Virtual Focused Discussion: Mississippi and Alabama Gulf Coast Community Stakeholder Perspectives on Managed Retreat, March 2023.

“While there are numerous programs available, the lack of trust, knowledge, and accessibility poses a significant challenge. It has been mentioned before that there are no individuals knocking on our doors, offering support. In reality, even if someone were to approach me, I wouldn’t trust them. So, we need trusted individuals in the community who can introduce the programs to the community. Then, the community can open up and have access. It’s not that we don’t have an overwhelming number of programs, but we need to give them access to our community for better use, and trust plays a huge role in that.”

SOURCE: Eliseo Santana, Resident of St. Petersburg, Florida. Workshop 2: Opportunities & Challenges of Climate Adaptation on Florida’s Gulf Coast, July 2022, St. Petersburg, Florida.

“So, I—as an organizer, I have been completely unsatisfied with the political response to these issues. Like, currently I’m working on an electrical school bus campaign to transition every school bus in the state of Florida to electric. While that’s—you know, that’s important. When it comes to finding funding from municipal and local governments, county governments, to develop charging infrastructure, for example, there’s no political will to do that and there just isn’t a compromise. Nobody is willing to come together to see that done. So, yeah, I believe that it’s going to take more involvement from academia, from frontline communities, people coming together and demanding more of their elected officials […] I’d also like to mention that in 2021, I was doing disaster resilience work in the Town and Country area, and we had collected about 3,000 surveys. And three in 100 people who were surveyed knew who their elected officials were.

So, you have entire communities who don’t know who their city council person is. They don’t know who their state house representative is. They don’t know who their state senator is. So, if our elected officials can’t be trusted to go out into the communities that they represent and inform these people of what’s going on, we have to hold them accountable. We have to expect more from the people that we elect to represent us. That is their duty. That’s the reason we put them into office. If they can’t do something as simple as making sure that the community is safe from climate change, I’m sorry, you shouldn’t be in office.”

SOURCE: Getulio Gonzalez-Mulattieri, Resident of St. Petersburg, Florida. Workshop 2: Opportunities & Challenges of Climate Adaptation on Florida’s Gulf Coast, July 2022, St. Petersburg, Florida.

“So, one thing we saw negatively when the government interacted with communities when it came to the land was their claims of eminent domain to claim a lot of the lands in the coastal region. And another thing they did, they did not gather our people altogether as a group. They went homestead to homestead, you know, and they had intimidating tactics where they had the local official, the sheriff’s department with them, men from the government, and they had people sign papers. Well, the concept of landownership and paper did not translate, you know, with the people. They didn’t really grasp that concept of when they were signing these documents that they were losing their land, giving their land away, because they were told that, you know, the government was going to use it, that they had more beneficial use of the land than the people but that they wouldn’t—their actions would not interfere with the people’s lifeway.”

SOURCE: Elder Rosina Philippe, Atakapa-Ishak/Chawasha Tribe and President of the First Peoples’ Conservation Council. Workshop 3: Community Viability and Environmental Change in Coastal Louisiana, July 2022, Thibodaux, Louisiana.

“Being a practicing journalist, I understand the importance of getting the right information from the right sources, and I think maybe I could best answer by saying that I don’t want to get the information from the city government or the state government because of their attempts—I don’t think they have our best interests at heart. We need to get direct information from the organizations or the agencies so that we know that the information is authentic and accurate.”

SOURCE: Gordon Jackson, Board President, Steps Coalition. Virtual Focused Discussion: Mississippi and Alabama Gulf Coast Community Stakeholder Perspectives on Managed Retreat, March 2023.

Plan (National Academies, 2023b).4 Messages need to clearly indicate need and purpose with adequate information that is clear and comprehensible at the community and household scale (Harrington-Abrams, 2022; Spidalieri & Bennett, 2020d). One-on-one interaction can reduce uncertainties and foster trust. People need more information about their potential destination (i.e., receiving place) to eliminate uncertainties (Hino et al., 2017).

It may be useful to foster partnerships and knowledge exchanges between originating and receiving communities (or the community that holds customary title to the receiving area). More discussion of partnerships between originating and receiving communities can be found in Chapter 8. Ministries, academics, and nonprofit groups with expertise in social services, cultural preservation, and local languages may be helpful in fostering communication and bridging knowledge (Connell & Coelho, 2018, p. 48), and ultimately in “linking” social capital across hierarchies. External facilitators should spend time in dialogue with originating and receiving communities and their trusted leaders to facilitate building trust (Dumaru et al., 2020). Additionally, longer planning timeframes can help build relationships among the various actors, allowing for more meaningful community participation (see Box 7-3; Boege & Shibata, 2020; Campbell, 2022; National Academies, 2023a).

Communicating Relocation as an Option

Community-driven relocation means that the decision to relocate is community-led, a process that rests on effective communication. Early and consistent communication is essential to facilitating awareness and understanding that relocation is even an option (see Box 7-4). Communication and engagement strategies may need to be tailored to a given community; working with community members through co-production (see below) and scenario methods may be helpful for understanding the culture and identity of a community (Bragg et al., 2021; Lemos & Morehouse, 2005; Wollenberg et al., 2000).

When co-producing such strategies, it is important to keep in mind that community members may utilize a variety of perspectives and values to assess a relocation strategy. Alexander et al. (2012) found that few community members make decisions related to relocation using a political perspective, most respondents appeared to draw on more than one worldview, and there were a variety of viewpoints about the risks of sea level rise. Because of the difficulty of reaching consensus amidst this diversity of perspectives, the authors “propose that the goal of community engagement processes should

___________________

4 More information about Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan is available at https://coastal.la.gov/our-plan

BOX 7-3

Community Testimonials: Community-Led Decision Making and Engagement

“I’d also like to say also that’s—that about relocation. Sometimes we’re—you know, given our history in the south, given our history of how we do things and how long it takes to do things, relocation is pretty much not a option, because what we’re thinking is, because we don’t have the influence in our communities and then people, the powers that be, that has the decision-making power, we want to be able to be inclusive in that so that I’m not moving because you’re not doing nothing. You know, we want to make sure that everybody has a—that we have a fair option, that we’re putting resources in the community, so you don’t have to relocate.”

SOURCE: Trevor Tatum, Resident of St. Petersburg, Florida. Workshop 2: Opportunities & Challenges of Climate Adaptation on Florida’s Gulf Coast, July 2022, St. Petersburg, Florida.

“Earlier I said ‘assisted retreat,’ when people choose. In other words, the community takes the lead by saying, ‘We want to do this’ or ‘I as an individual want to do this.’ The government responds to the initiation of the individual or the community. So, no one’s managing. Someone’s assisting in doing something that both groups agree is the direction to go […] and do it with the idea that it is assisting people to do the will that they hope to do.”

SOURCE: Windell Curole, General Manager, South Lafourche Levee District. Workshop 3: Community Viability and Environmental Change in Coastal Louisiana, July 2022, Thibodaux, Louisiana.

“More or less people coming in with ideas, and their studies, or whatever, tend to view what the local population had to contribute as being anecdotal or just nonscientific, you know, something that was not of value to the whole. We have made some strides and made some changes. But I think sometimes we still run into these concepts. And that’s the perspective that we have to change. Come in, sit at the table, invite, you know, people to have those conversations and let it be a true collaborative effort, you know, where I’m learning from you, you learning from me, because our objectives should be the same, the best for the region that we’re hoping to work in and to live in. And I think the more that we foster those kinds of concepts and ideas, we all would come out for it in the better. But, you know, that’s a long road to go […] So, you know, we just need to have those conversations. Those conversations need to begin with the at-risk communities. You know, not coming in as an afterthought or, you know, or even inviting—sometimes we’re invited to the table just to get your opinion. But at the end of the day, we see that whatever you share doesn’t make it to the end product.”

SOURCE: Elder Rosina Philippe, Atakapa-Ishak/Chawasha Tribe and President of the First Peoples’ Conservation Council. Workshop 3: Community Viability and Environmental Change in Coastal Louisiana, July 2022, Thibodaux, Louisiana.

be to encourage the underlying messages of competing interest groups to be understood by all stakeholders [… A]lthough efforts should continue to communicate with science and economics, a broader dialogue is required to address community concerns about the complex topic of managed retreat” (Alexander et al., 2012, p. 429). In other words, it is important that various groups are transparently engaged and respected, even if consensus cannot be achieved. Bragg et al. (2021) encourage the use of “surveys or workshops to understand the predominant worldviews, priorities, and values” of involved communities.

Effective communication may require building trust among community members and leaders. Key to this process is understanding how relationships form in a given community, including knowing “the ways people connect culturally and create spaces for conversation,” which can then be incorporated into meetings with community members (Climigration Network, 2021, p. 26). Ryan et al. (2022) also emphasize the importance of allowing space for residents to tell stories, voice concerns, and provide local knowledge. When engaging in communication, the messenger is also a relevant consideration; “when residents learn about plans from a trusted local source who supports the changes, they are more likely to be accepting” (Bragg et al., 2021). Outside messengers should reflect on their positionality and acknowledge that some community members may not be willing to share information with outside individuals (Climigration Network, 2021). This may be particularly true when community members have had negative experiences when sharing their stories previously, making “trauma-informed” work essential when interacting with impacted communities (Climigration Network, 2021).5

Transparency

A key communication issue for residents facing relocation is transparency (Shadroui, 2022; Siders, 2018; Tucker, 2018). Throughout the Gulf region, there has been a lack of transparency about what is planned or contemplated with regard to relocation. For example, there is variance in the scope and administration of buyouts across communities wherein buyouts are mandated in some locations and not others. The reasons for this variation often are not transparent and may seem arbitrary or even discriminatory in communities where there is limited understanding of the

___________________

5 The Climigration Network (2021, p. 30) defines “trauma-informed” work as “realizing the widespread impact of trauma, recognizing its signs and symptoms, and integrating knowledge about it into policies, procedures and practices.”

BOX 7-4

Community Testimonials: Challenges for Effective Communication and Outreach

“The Hispanic community in Pinellas County presents a unique situation. Unlike other neighborhoods, we are integrated across different socioeconomic levels, from the poorest to the richest. We lack concentrated pockets within specific neighborhoods. Therefore, we require a central location, like a magnet, where community members can come together for cultural celebrations and receive assistance. This location would serve as a hub to connect individuals with the resources provided by local government, organizations, and institutions, and that requires a sense of community. Once we’re connected as a community, we can amplify our voice in the political realm and advocate for increased resource allocation from our politicians.”

SOURCE: Eliseo Santana, Resident of St. Petersburg, Florida. Workshop 2: Opportunities & Challenges of Climate Adaptation on Florida’s Gulf Coast, July 2022, St. Petersburg, Florida.

“So, what I’m saying is, is there an initiative that we got going on that we haven’t disseminated all the information in the communities, so that we can make good decisions, you know, about these things. And I think that, not only that, but there’s also a lot of things—the information problem is really there. And I don’t know who’s giving up the information, but I think that that’s one of the things that we should address. Is the information getting to everybody, so that everybody has an equal opportunity to deal with whatever they have to deal with?”

SOURCE: Trevor Tatum, Resident of St. Petersburg, Florida. Workshop 2: Opportunities & Challenges of Climate Adaptation on Florida’s Gulf Coast, July 2022, St. Petersburg, Florida.

“So, when you talk about the—if I didn’t go to Leadership Terrebonne last year, which is the—a group of leaders that they do every year, I would have never known about the Coastal Master Plan […] I’m not going to lie, the language was a lot for the average person to understand. I do believe that if you want people to truly understand what you’re talking about, what it entails, that has to be broken down for the average person to understand […] We have to realize that in Terrebonne Parish we are actually working to build up our educational level. Most people have a high school diploma and that’s just about it. We are 22 percent, 22 percent of a higher, post higher education here in this community. So, we have to make it more so people can understand what that entails and what it means, break that down to the ordinary person, so somebody can understand what that plan entails, what does it look like. And save the scientific terms, no offense to you and your studies and your research. But for the average person, they should know—break it down to them.”

SOURCE: Sherry Wilmore, Resident of Houma, Louisiana. Workshop 3: Assisted Resettlement and Receiving Communities in Louisiana, July 2022, Houma, Louisiana.

“[I]n the coastal communities, too, there’s a bit of distrust just because of past experience. You’ll have forecasters that say, ‘This is going to be a terrible, terrible, terrible storm,’ and it comes, and nothing materializes. And so, the next one, they’re not as worried about it. And then you have something like a couple of years ago when we had Tropical Storm Eta. It hardly made the news. There wasn’t an emergency declared, and Madeira Beach got walloped. I mean, we got flooded. We had 75 water rescues in the middle of the night, no power, streets flooded up to chest level. The next day, it looked like the world’s worst yard sale out there, just people hauling carpets and furniture from their homes, cars getting towed out. We had no warning. By the time we were offered sandbags, the roads were flooded and impassible. So, there’s a real disconnect sometimes with what is being said with what is happening.”

SOURCE: Chelsea Nelson, Resident of Madeira Beach, Florida. Workshop 2: Opportunities & Challenges of Climate Adaptation on Florida’s Gulf Coast, July 2022, St. Petersburg, Florida.

different criteria for buyouts and how they will be implemented for local households.6

However, transparency issues with the buyout process are not limited to the Gulf region. For example, at the committee’s information-gathering session on property acquisitions, Courtney Wald-Wittkop, program manager of New Jersey’s Blue Acres buyout program, described a lesson learned:7

I think one of the other things is transparency. We realized that in the past we were treating buyouts like simply a real estate transaction. We were really focused on making sure that the homeowners had all the information, and we had case managers whose job it was to walk the homeowners through the process, one-on-one. But really there wasn’t as much concern about making sure that the communities where these buyouts were happening were as engaged or informed. Elected officials change and buyout programs span a couple of years, [so we] have to keep building the vocabulary of local government officials so they understand what is going

___________________

6 Comments made to the committee on June 8, 2022, during a public information-gathering session in Texas. More information is available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/06-08-2022/managed-retreat-in-the-us-gulf-coast-region-workshop-1

7 Comments made to the committee on December 13, 2022, during a public virtual information-gathering session. More information is available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/12-13-2022/managed-retreat-in-the-us-gulf-coast-region-perspectives-and-approaches-to-property-acquisitions-challenges-and-lessons-learned

on, what the end goal is, and what the driving philosophy was from the buyout planning process through the implementation and into the post-buyout restoration phase.

Issue framing affects communication between government and residents, and highlights differing perspectives and priorities. For example, climate change issues may be received differently when framed as a health problem compared to another type of problem (e.g., economic or environmental; Badullovich et al., 2020; Dasandi et al., 2021). Transparency around the framing of issues around relocation can affect outcomes. This could also apply to transparency around eligibility to participate in the process, including issues such as the geographical boundaries of buyout zones (Binder & Greer, 2016; Martin et al., 2019). For example, migrants and minoritized groups have been disproportionately affected by a lack of communication about relocation (Shi et al., 2022). Strategic communication can contribute to improved transparency, especially in underserved communities, in several ways:

- allowing for meaningful input from residents about alternative approaches;

- enabling potential relationships between the community leaders involved in disaster recovery and relocation professionals (e.g., planners, local government) that advise on the process and logic of the relocation process;

- providing time for people to become prepared psychologically and to prepare their families for possible relocation; and

- allowing for people to make their own decisions about where they wish to go.

Participation and transparency mean full community engagement in all discussions.

Language, Literacy, and Cultural Considerations

Workshop participants in Houston explained that letters sent through the U.S. Postal Service are the main way that they have received information regarding buyouts (National Academies, 2022c), but that this critical information was not available in other languages (e.g., Spanish, Vietnamese), engendering a sense within those communities of being excluded from the process. Language coupled with limited connections to elected officials, staff turnover, and the lengthy process result in many people being left out (National Academies, 2022c). The impact of turnover can be prevented by local community leaders, through employment or other means, with

knowledge and access about the relocation processes to facilitate communication and, in turn, deliver residents’ concerns back to the government—a process that could foster a more participatory and culturally relevant approach (see Box 7-5). Underresourced groups can be included by working with trusted leaders in vulnerable towns and cities to act as communicators about buyout options and to help design and promote locally meaningful and community-led models of relocations that have been shaped by residents. Those involved with relocation efforts need to understand not just the physical topography but also the social and ethnic topography of communities to assure meaningful engagement and action (e.g., language, and sociocultural values that underlie choices about where to live; National Academies, 2022c, p. 38, 2023a; Spidalieri & Bennett, 2020a).

Systemic inequalities also create practical barriers to participation in relocation. The COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated both the promise of connection through technology and the large and enduring gaps in who has

BOX 7-5

Community Testimonials: Lack of Resources and Equity

“So, the feeling of feeling stuck I believe comes from people who don’t have resources. So, they don’t know which way to go, what to do, or how to solve the problem. And if there is not a resource that is available or one that they can qualify for, collect the data, present it to the city and let them know what the needs are.”

SOURCE: Antwaun Wells, Resident of St. Petersburg, Florida. Workshop 2: Opportunities & Challenges of Climate Adaptation on Florida’s Gulf Coast, July 2022, St. Petersburg, Florida.

“I wanted to say also that there has been a trend that’s been going on in our five bayous for a long time. And we noticed, you know, as the people are moving, as the resources are leaving, you know, it’s the small businesses, it’s the mom and pops. And then they come for the schools and then the schools are closing. You know, they’re taking away or we’re losing, you know, all these things that brought people together, you know, all these things where people gathered at, like the fairs that happen on all the bayous through the churches, slowly all of these things are being taken away from each of these areas. You know, and then to where’s just, you know, there’s just the people and then the people are not coming out and communicating as heavily as they were back in our days, you know. It’s just been a trend that has been growing over, you know, the last several years and it’s just, it’s growing strong and that is also a huge contribution to the disconnect that is taking place, you know.”

SOURCE: Bette Billiot, the United Houma Nation. Workshop 3: Assisted Resettlement and Receiving Communities in Louisiana, July 2022, Houma, Louisiana.

access to that promise (Parker, Menasce, & Minkin, 2020; Vogels, 2021a,b; Vogels et al., 2020). It is well known that traditional news media—newspapers, radio, and television—are no longer consumed universally and that local print news sources in many communities have dried up (Pew Research Center, 2019). The Internet itself is not a reliable way of reaching people in communities universally. Moreover, even in the presence of strong online networks, broadband is often not an option in rural areas (Vogels, 2021b) and on tribal lands (Howard & Morris, 2019). Access to broadband also affects the ability of people in many communities to participate via the ability to attend online community meetings, conduct online research, and fill out online applications. Participating is difficult when lower-income households have difficulty affording child care (National Academies, 2022c; see also Bhattarai & Fowers, 2022). These factors have significant implications for who can participate in community meetings and other activities concerning less immediate needs, such as future options for relocating their community. Outsiders coming into the community to build capacity or otherwise engage community members might not be sensitive to these barriers, or cognizant of their effects on community involvement or decision making (see Box 7-6).

Communicating relocation as an option for those who wish to move entails communicating why the option is even on the table. In other words,

BOX 7-6

Community Testimonial: Lack of Communication

Workshop participants did not feel they had been communicated appropriately with about the mandatory buyouts affecting their homes.

“I am one of the people who has tried to stay very active in the communication with them, trying to have contact with the directors or superiors because it is not easy. Also, because the information at times does not reach people, and they are not doing everything possible to ensure that it reaches people who have not even been visited by one of them. There have been various communication problems and a lack of preparation in the program. It became apparent that the staff were not prepared for this type of program because many people had come and gone in the program area. We had very little access to communication with them; they did not answer calls and we had to fight to get emails answered, since there are also many elderly people who speak mostly Spanish. They were not prepared at all for this type of situation.”

SOURCE: Perla Garcia, Coalition for Environment, Equity, and Resilience. Workshop 1: Buyouts and Other Forms of Strategic Relocation in Greater Houston, June 2022, Houston, Texas.

communicating risk in locally understandable terms and learning from residents about their perceptions and their local knowledge are critical to a community-driven relocation process. The next section discusses the importance of local risk perception, as well as models and strategies for risk communication and messaging.

RISK COMMUNICATION

Lessons learned from the communication of scientific information on climate change are relevant to communicating risk in the context of relocation efforts. A recent National Academies report (National Academies, 2022b, Box 2, p. 1) suggests 10 practical strategies for communicating about climate risks to vulnerable communities:

- Use simple, clear messages by paring down technical information.

- Understand how messages are interpreted by different communities.

- Repeat messages often.

- Enlist caring messengers trusted by both decision makers and local communities.

- Articulate clear objectives for climate- and disaster-related actions.

- Move beyond the abstract and describe risks in terms that are psychologically near in space and time.

- Trigger affect-driven responses but use emotional appeals judiciously.

- Emphasize emerging social norms around adaptation and resilience.

- Frame climate change–related hazards and risks strategically.

- Convey the available risk management options and their effectiveness.

Among these generalized strategies, strategy two makes clear that effective risk communication also necessitates an understanding of risk perceptions in the specific communities one is engaging. Recognizing how people perceive risk can thus help improve the two-way communication needed for major adaptations like relocation to be discussed, planned, and implemented effectively and equitably.

Risk perception “generally refers to how individuals cognitively and emotionally evaluate risks and their vulnerability” (Lim, 2022, p. 3; see also Grothmann & Reusswig, 2006; Lindell & Perry, 2012; van Valkengoed & Steg, 2019) and is influenced by local values and mental models (see below) of what is important to community residents (Bostrom, 2017; Kempton et al., 1995; Leiserowitz, 2006). Both past experiences and personal values determine a person’s acceptable level of risk (Siegrist & Árvai, 2020; Zammitti et al., 2021). In addition, it is important to recognize that humans have a finite number of things they can emotionally process before they become

overwhelmed. Therefore, people prioritize issues and actions that seem most urgent, which can affect risk perception.

Understanding this threshold can help communicators comprehend an individual’s perception of and response to that risk. Friends, family members, and other actors within an individual’s social network play a strong role in cues about risks and values, and also influence an individual’s social learning (Haer et al., 2016). To improve risk communication of potential relocation, all of these factors must be taken into consideration. Once an appropriate message has been co-developed with community partners, it is important to offer realistic solutions, use trusted messengers to deliver the message, and respect different viewpoints while also acknowledging the emotions the message may trigger (Bard Center for Environmental Policy, 2012; Hayes et al., 2018; United Nations, n.d.).

Effective messaging about relocation does not mean presenting the same facts over and over again. It means that leaders or outside authorities develop a dynamic, strategic, and intentional way of meaningfully conveying risks based on an understanding of how individuals and the community perceive risk in general. This sort of communication must happen while working alongside community members, to alter the message as needed to support better risk perception and address concerns expressed by those affected.

For a relocation effort to become community-driven, effective communication strategies, especially in places where place attachment runs deep, are critical (Hanna et al., 2020). Risk communication in general is challenging, especially when it involves an often-uninformed or under-informed public. For example, in climate change–related risk communication, communication and engagement between stakeholders and residents can be hampered by common cognitive barriers, such as the relevance of climate change impacts to one’s life; a disagreement with the vision, plan, or solution (e.g., relocation); or the framing of the issue and the language around it (Moser, 2007; Moser & Dilling, 2007). The uncertainty resulting from risk mitigation is also very much at the heart of the relocation dilemma (Hanna et al., 2020), making risk and potential mitigation measures difficult to communicate to locals who are often the ones impacted by this gap.

An expected outcome of effective risk communication to the community is an increased knowledge of the risk and the associated mitigation measures. For climate-related policies to succeed and gain support, this sort of knowledge and awareness is critical (Khatibi et al., 2021; Madumere, 2017). In a synthesis of articles on participatory environmental monitoring, participant outcomes included knowledge gain, increased community awareness, attitude and behavior change, and support toward natural resource management policies (Stepenuck & Green, 2015). Whether the knowledge acquired by an individual is local knowledge in an informal

setting (Semali & Kincheloe, 1999) or traditional/Indigenous knowledge with a code of ethics guiding environmental use (Craig & Davis, 2005; Mazzocchi, 2006), the context of the knowledge-gathering process is critical as to whether it is used effectively. In communicating the nature and risks of climate change to the public, it has been suggested that a coordinated process of using both local knowledge and scientific information can increase people’s understanding of critical issues (Bulkeley, 2000). Such a coordinated approach can also improve the trust between and among community members (Khatibi et al., 2021).

For information to be perceived as credible and usable to influence policy outcomes, a more active, iterative communication approach is critical (Cash et al., 2003). A well-crafted public engagement process where stakeholders and community residents participate in the (co)production of plans and strategies is an essential step to ensuring that knowledge created can be useful and beneficial to community members (Lemos & Morehouse, 2005). Such an approach of active public engagement has been seen to be a critical component of successful managed retreat exercises, and it provides a valuable lesson about the intersection of risk communication and community knowledge creation (Spidalieri & Bennett, 2020d). The next section discusses mental models, which is another tool that can be utilized to access cultural understandings of risk and climate in the context of relocation.

Mental Models for Risk Communication

Morgan et al. (2002) explain the need for a systemic approach to communicating risk. In many cases, rather than conducting an assessment of what the audience believes and what information they need to make the decisions they face, communicators will often turn to technical experts to ask what people should be told. When confronted with a wealth of information that is not tailored to specific needs or understandings, the target audience can become confused, miss the point, or become disinterested. To overcome this dilemma, a five-step method, known as the mental models approach, was developed for creating and testing risk messages: (1) create an expert model, (2) conduct mental models interviews, (3) conduct structured initial interviews, (4) draft risk communication, and (5) evaluate communication (Morgan et al., 2002).

Photo sorting, open-ended interviews, and confirmatory questionnaires are a few methods by which data can be collected to better understand shared mental or cultural models (cf. Kempton et al., 1995). Comparing expert mental models with those of the target audience can reveal different ways of understanding the same issue, gaps in knowledge and confusing terminology for both sides, as well as linkages to misconceptions for both sides. This information can then be used to co-produce both more accurate

and more culturally relevant messages about risk. This process can be time-consuming but is necessary to properly understand and communicate risk.

PARTICIPATION AND KNOWLEDGE

Relocating and resettling is a complex process of change and adaptation that involves more than the physical act of moving. It is a social process that involves the cooperation, coordination, and participation of affected people at the originating and receiving nodes, as well as various stakeholders that could cross sectors and jurisdictions, as evident in case studies in Chapter 3. Critical to the engagement process is the inclusion of local knowledge, such as place-based knowledge systems or TEK, as described below.

A public lack of trust in entities managing relocation (e.g., government) and a lack of communication and transparency in information about relocation (e.g., buyout criteria; post-buyout land use), compounded by a lack of access to decision-making spaces, also limit the fostering of social capital. The next section takes a closer look at how particular types of social capital might alleviate issues of access, transparency, and participation in the context of relocation.

Linking Social Capital to Participation and Civic Leadership

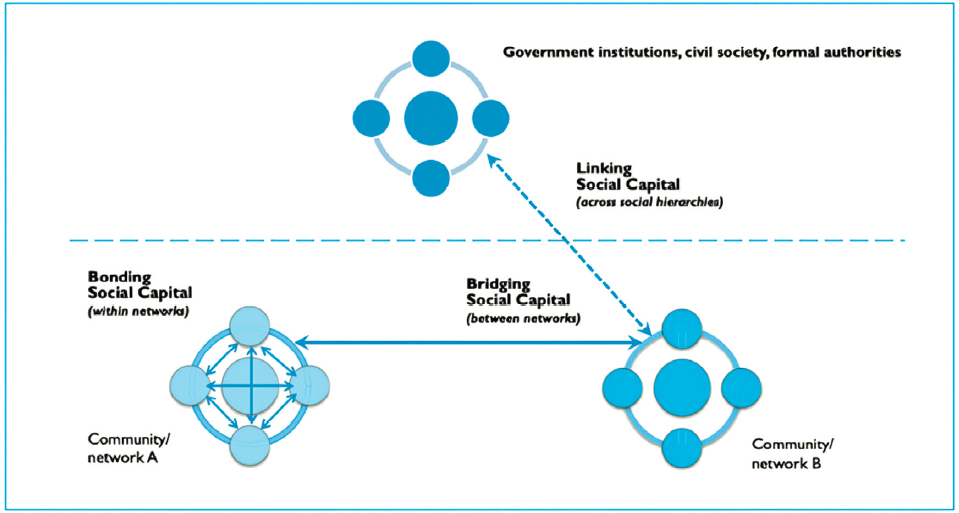

The well-being of a community is both a contributor to and an outcome of building social capital. In this section, we continue the discussion of social capital and community well-being in Chapter 6 by considering how social capital is critical to enabling effective civic leadership, which is, in turn, a contributor to and outcome of community well-being. To do this, we look at three different types of social capital, as identified by researchers: bonding (within networks), bridging (between networks), and linking (across hierarchical networks of power; Adger, 2003; Aldrich, 2012; Frankenberger et al., 2013; Kawachi et al., 2004; Putnam, 1993a, 1995). Each type of social capital “identifies variation in strength of relationships and composition of networks and thus different outcomes for individuals and communities” (Aldrich & Meyer, 2015, p. 258). These categories are particularly useful in considering the role of social capital in participation and civic leadership, as described below.

Bonding refers to emotionally connected members of the same network, such as friends or family (Adler & Kwon, 2002). Bonding is essential for fostering trust, solidarity, and reciprocity, and can be especially useful in disaster contexts and during other times of dire need (Hurlbert et al., 2000). Bridging refers to connections between more demographically diverse networks, such as between groups that are united through institutions (e.g.,

sports, religion, civic or political unions, parent-teacher associations; Aldrich & Meyer, 2015). Bridging between these different groups is essential for the exchange of novel information and pooling of resources. Linking social capital refers to connections that cross sociopolitical hierarchies and link communities to institutions and political structures, connecting “regular citizens to power” (Aldrich & Meyer, 2015, p. 259). Linking is essential for political representation, the mobilization of resources, and the enhancement of civic leadership.

Focusing on social capital in conceptualizing resilience reveals the importance of social relations in a community’s capacity to respond to challenges (Eder et al., 2012; Marré & Weber, 2010; Osborne et al., 2007; Riabova & Skaptadóttir, 2003). Research examining disaster response asserts that relevant social relations include those among local governments, aid organizations, and affected populations or community members (Barrios, 2014), including religious and co-ethnic social capital and networks spanning geographic scale (Airriess et al., 2008). Linking social capital, which connects hierarchies, can create feedback loops between otherwise independently operating entities (e.g., community members, grassroots organizations, scientists, government planners) working on thematically or geographically overlapping projects (Frankenberger et al., 2013; see also Aldrich, 2012; Woodson et al., 2016; see Figure 7-2). Feedback is important for entities that are potentially in conflict with one another, depending on material (e.g., subsistence) and symbolic (e.g., identity, sense of security) attachments to place (Dandy et al., 2019; Masterson, 2016; Masterson et al., 2017).

A key takeaway from our committee’s workshops was that people do not feel involved in the discussion and decision-making processes about relocation or relocation options or do not know about these processes and, therefore, feel they have little to no influence on them (see Box 7-1, above). If social capital connects “regular citizens to power” (Aldrich & Meyer, 2015, p. 259) and engenders political representation, focusing on bridging social capital among communities and then linking that social capital across sociopolitical hierarchies can provide access to decision-making spaces and promote participatory decision-making processes that can, in turn, draw on local knowledge and enhance community resilience and well-being (Aldrich, 2012; Woodson et al., 2016).

Examples of linking social capital include collaborative governance strategies that integrate citizen science (McCormick, 2009, 2012), community science (Charles et al., 2020), participatory action research (PAR; Baum et al., 2006), Indigenous and local knowledges (Renn, 2020), and strategies that engage a collective response to such change (Boonstra, 2016). These strategies draw on emotional and behavioral strengths that can be positively nurtured by mental health systems and other core social anchoring

SOURCE: Aldrich, D. P. (2012). Building resilience: Social capital in post-disaster recovery. University of Chicago Press.

institutions, as discussed in Chapter 6 (Belkin, 2020; Wamsler & Bristow, 2022; Wamsler et al., 2021). Importantly, a focus on social capital and civic leadership does not diminish the importance of material resources in shaping community well-being while managing adaptation (see “All Resources Matter” in Chapter 6).

Other approaches that show the range of thinking about linking social capital to civic leadership and policy participation include empirical work about voluntary collaboration and cooperation in managing shared environmental resources and harms, such as Ostrom’s key design principles for managing commons resources (Dietz et al., 2003; Ostrom, 1990; see also applications of Multilevel Evolutionary Framework; Waring et al., 2015). Such approaches pull on certain emotional and behavioral strengths and attributes identified as foundations of emotional resilience, and can be positively nurtured and learned by mental health systems as well as other core social anchor institutions, as described in Chapter 6 (Belkin, 2020; Wamsler & Bristow, 2022; Wamsler et al., 2021). These combined elements of participation, social cohesion, and emotional well-being are interconnected and essential for realizing transformational adaptation (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC], 2014b; Shi & Moser, 2021).

Similarly, studies of participatory decision making draw attention to innovation in how knowledge relevant to these decisions is packaged in a way that is coherent to residents and other stakeholders. To achieve this coherence, there is a need for novel transdisciplinary and locally generated approaches, such as citizen science and tacit, cultural, and Indigenous and local knowledge (Renn, 2020).

Power Sharing and Participatory Decision Making: Who Decides?

The multiple dimensions of power that affect levels of community engagement in decision making for social change have been analyzed by Gaventa (2006). There are several examples and methods of empowerment and participation that can enhance and rely on social capital and collective governance. In the Gulf region, the Louisiana’s Strategic Adaptations for Future Environments (LA SAFE) initiative provides one such example.8 LA SAFE took a holistic and regional (i.e., cross-sector, multi-jurisdictional) approach to addressing climate-induced risks and enhancing resilience by enlisting the support of, and training, trusted community leaders to help lead the engagement process. Key lessons from LA SAFE include the importance of the program in acknowledging the inherent limitations of its data and “communicating the need and opportunity to augment preacquired

___________________

8 More information about LA SAFE is available at https://lasafe.la.gov/

data and science with locally sourced experiential knowledge” (National Academies, 2023b, p. 38).9

There is also increasing adoption of activities, both nationally and internationally, for more community-involved decision making on matters of policy through relationship-building and active collaborations between community members (e.g., residents) and other community stakeholders (e.g., local government, community-based organizations; Boothroyd et al., 2017). These collaborations have taken a range of formats, often described as “deliberative” or “participatory democracy” (Curato et al., 2017; Gilman, 2019). They can also take many forms and exist at multiple scales, including citizen assemblies, citizen juries, public utility ownership, and participatory budgeting. Collaborations have the capacity to cover a diversity of geographies and a range of scopes and mandates, and involve communities of differing populations. For example, citizen panels or juries might focus on a more bounded question of policy and/or place for action (e.g., Citizens Initiative Review Commission).10 These are examples of more systematic ways of positioning more collective and participatory deliberation and decision making in discussions about relocation.

The basic logic underpinning these approaches to collaboration is that a random but representative set of community members can make good decisions that might be credible to the larger community if some key parameters are in place. Those parameters tend to include a sequencing of steps along the lines of deliberation: facilitated group learning, group propositions, and coming to consensus. Ideally, throughout each step of the process, a set of subject matter experts prepares trusted, objective background information and responses to member questions (Curato et al., 2017; Dryzek et al., 2019; Gilman, 2019; Le Strat & Menser, 2022).11 In many ways, these practices capture some of the ground rules of collaborative governance of commons resources described by Elinor Ostrom (1990) in her Nobel prizewinning work and, relatedly, in principles of prosociality, which mutually reinforce social cohesion, ties, and well-being (Atkins et al., 2019).

Longer planning timeframes can help build relationships and trust among the various actors, allowing for more meaningful community participation. For example, in the Carteret community relocation in Papua New Guinea, the community-based nonprofit organization Tulele Peisa reached

___________________

9 More lessons learned from LA SAFE and other community-centered Gulf region and national resilience-building efforts from a National Academies study are available at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/26880/chapter/5#37

10 More information on the Citizens Initiative Review Commission is available at https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2019R1/Downloads/CommitteeMeetingDocument/173979

11 More information about examples of approaches in the United States for other health and public health uses are available at https://healthydemocracy.org/what-we-do/local-government-work/oregon-assembly-on-covid-recovery/

out to families facing relocation several years before starting relocation, and likewise invested much time in outreach to the receiving communities and relationship-building between hosts and settlers (Ristroph, 2023; United Nations Development Programme, 2016).

Co-Production of Community-Driven Relocation

There is a growing recognition of the importance of involving multiple stakeholders, including community residents, in the co-production of climate adaptation strategies (Conde & Lonsdale, 2005). In the context of this report, co-production is the process of developing knowledge, plans, and strategies through the iterative engagement of at-risk communities, researchers, practitioners, and other groups, whose participation is necessary to the relocation process (see Armitage et al., 2011; Meadow et al., 2015; Wamsler, 2017). The literature on co-production has been growing since the 1970s and has been applied across fields and contexts (Norström et al., 2020). It is beyond the capacity of this report to specify which disciplinary form or interpretation of co-production is ideal for relocation planning and implementation. However, the climate adaptation strategy of community-driven relocation, as recommended by this committee, shares co-production’s guiding principle of equity in participation and knowledge (Yua et al., 2022)—which may involve broadening engagement with Indigenous knowledge systems (Carlo, 2020) and the “prioritization of Indigenous voices, experiences, knowledge, reflections, and analyses” (Zanotti et al., 2020; see also White House, 2022, p. 12).

PAR and Practice

PAR differs from conventional research in that it focuses on how to enable action, it pays considerable attention to power relationships, and it blurs the line between researcher and those being researched (Baum et al., 2006) in the (co)production of actionable knowledge. Self-reflection is a key component of this research process. Similar to co-production, PAR is an iterative approach that cycles between research, action, and reflection. It uses both qualitative and quantitative data collection to better understand a problematic situation while bringing to light the views of local people, their reality, their challenges, and their ideas for solutions.

Schneider (2012) outlines the key goals of PAR: (a) to produce practical knowledge, (b) to take action and make the knowledge actionable, and (c) to be transformative both socially and for the individual(s) who take part in it. This requires a commitment to the co-production of knowledge by researchers and ordinary people (White, 2022). It also implies a mutual learning among participants and respect for the different types of knowledge shared by participants. PAR typically pays attention to the needs of

marginalized groups or people and promotes social justice for these groups (Cornish et al., 2023).

A recent consensus report by the National Academies (2023b) about strengthening equitable community resilience in U.S. Gulf Coast and Alaskan communities utilized the PAR framework. However, the study committee decided to add the word “practice” to the term and thus coined PARP. As the study committee noted, “[T]he inclusion of the term practice underscores the practical applications of PAR and how the PAR approach can be applied beyond pure research projects to include capacity-building projects that may or may not include a research component” (National Academies, 2023b, p. 3).

Local and Indigenous Knowledge in Participatory Planning

Communities want to determine their own climate change adaptation strategies, and scientists and decision makers should listen to them—both the equity and efficacy of climate change adaptation depend on it. (Pisor et al., 2022, p. 213; see also Forsyth, 2013)

Increasingly, local and Indigenous knowledge12 is being sought out in scientific studies, land-use decision making, and planning to gain a more detailed understanding of how climate and other environmental and sociocultural changes are interacting and affecting communities on the ground. These place-based knowledge systems are diverse, distinct, and highly attuned to local conditions. They also may reveal how residents have in the past responded to similar environmental change or events, as well as how they are responding now or may respond in the future. Thus, the engagement of local and Indigenous knowledge along with scientific knowledge is increasingly being promoted and accepted as best practice in addressing diverse and intersecting climate challenges, especially when communities need to adapt or otherwise respond urgently to environmental changes (see Boxes 7-8 and 7-9; Lazrus et al., 2022; Thornton & Bhagwat, 2021; Wildcat, 2013).

Recent National Climate Assessments have emphasized the importance of engaging with Indigenous peoples. As summarized in the Fourth U.S. National Climate Assessment (Ch. 15),

___________________

12 According to the IPCC (2019), “Indigenous knowledge (IK) refers to the understandings, skills and philosophies developed by societies with long histories of interaction with their natural surroundings. Local knowledge (LK) refers to the understandings and skills developed by individuals and populations, specific to the place where they live.” More information is available at https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/faqs/faqs-chapter-7/

Indigenous peoples in the United States are diverse and distinct political and cultural groups and populations. Though they may be affected by climate change in ways that are similar to others in the United States, Indigenous peoples can also be affected uniquely and disproportionately. Many Indigenous peoples have lived in particular areas for hundreds if not thousands of years. Indigenous peoples’ histories and shared experience engender distinct knowledge about climate change impacts and strategies for adaptation. Indigenous peoples’ traditional knowledge systems can play a role in advancing understanding of climate change and in developing more comprehensive climate adaptation strategies. (Reidmiller et al., 2018, p. 105)

In November 2021, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) and the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) issued a memorandum on Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge (ITEK) and federal decision making, identifying the relevance and importance of the former in environmental decision making and committing to elevate its role in federal scientific and policy processes (OSTP, 2021). In this context, this report uses the term, ITEK (Lander & Mallory, 2021), as defined in the Key Terms (Appendix D).

A year later, on November 30, 2022, OSTP and CEQ together issued Guidance for Federal Departments and Agencies on Indigenous Knowledge (OSTP, 2022). The seventh principle is to “[p]ursue co-production of knowledge,” defined as “a research framework based on equity and the inclusion of multiple knowledge systems,” including those of the 574 tribes recognized by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs13 (Prabhakar & Mallory, 2022, p. 12). The new guidance aims to “promote and enable a Government-wide effort to improve the recognition and inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge,” and offers guidance for collaborating with tribal nations and Indigenous peoples (Prabhakar & Mallory, 2022, p. 3). This position is consistent with that of U.S. tribes for whom Indigenous knowledge recognition in co-production has become a key pathway for affirming Indigenous worldviews, rights, and responsibilities, including among tribes who may not have federal recognition but may be state-recognized or seeking federal recognition (Latulippe & Klenk, 2020; Zurba et al., 2022).

Earlier chapters have shown that local and Indigenous knowledge has been an important component of understanding and adapting to coastal conditions on the U.S. Gulf Coast, including extreme events such as

___________________

13 More information about the list of all tribal entities that are recognized by the federal government, as of January 2021, is available at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/01/29/2021-01606/indian-entities-recognized-by-and-eligible-to-receive-services-from-the-united-states-bureau-of

hurricanes and storm surges. Indigenous adaptations included earthworks to complement natural levees and seasonal, or in some cases permanent, relocations to avoid life-threatening conditions. Yet, many communities in threatened coastal areas today, such as the U.S. Gulf Coast, are not able to maintain local knowledge to previous degrees, nor to share it effectively with other governments. Furthermore, these Indigenous communities are marginalized and underserved and often have been made more vulnerable by loss of lands, mobility, and resources, and to industrial development and pollution, and other environmental stressors, thus undermining their capacity to cope or adapt (Cottier et al., 2022). All of these hazards threaten the existence of community and individual knowledge and practices. This has been pointed out in community meetings by local Indigenous groups, both as a part of this study and in previous studies going back at least a decade (Felipe Pérez & Tomaselli, 2021; Siders & Ajibade, 2021). For example, a member of the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw made the following statement in 2012:

We are historically fishermen and trappers. We have maintained this life well for hundreds of years, probably longer. Now our waters are contaminated by the industries that increase global warming and the layer of pollution in the atmosphere, which brings with it an increase in storms that has led to salt water intrusion of our lands. This is also destroying the vegetation that has been plentiful and abundant for generations, destroying the opportunity for us to be a self-supporting people and to share our bounty with the rest of the planet. (Maldonado et al., 2014, p. 602)

Local and Indigenous knowledge and adaptive capacity, then, must be considered against the backdrop of historical circumstances, including marginalization and inequality, which may have affected crucial relationships to local lands, waters, and other critical resources, as well as the rights of recognized tribes to exist and determine their own futures as sovereign entities (see Box 7-7). Two subsequent boxes highlight two other aspects of Indigenous knowledge within the realm of climate adaptation. Box 7-8 discusses the concept of TEK14 while Box 7-9 details a self-assessment tool for communities, the Coastal Resilience Index (CRI).

___________________

14 As defined in the Key Terms (Appendix D), TEK is “a cumulative body of knowledge, practice, and belief that evolves by adaptive processes, is handed down through generations by cultural transmission, and centers on the relationships of humans with one another and with their environment” (Berkes et al., 2000).

BOX 7-7

Community Testimonials: Self-Determination and Tribal Sovereignty

Community-led planning and relocation is vital, promoting an “assisted” approach rather than a top-down managed retreat. This highlights the need for self-determination and active involvement of impacted communities in every stage of the process—from planning to implementation and conclusion.

“If resettling communities is not done with a sense of responsibility and accountability to the people that are having to experience it, then we have lost much more than just our land. And part of the reason why we participate in these talks and discussions is because we know what our future holds if nothing is done. If we are not fully included, if our voices are not valued, we will cease to exist. And that process has been in the making for many generations. So at least we have something that we can leave behind. So that, if we no longer exist, we can be remembered.”

SOURCE: Elder Chief Shirell Parfait-Dardar, Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, and Chair, Louisiana Governor’s Commission on Native Americans. Workshop 3: Community Viability and Environmental Change in Coastal Louisiana, July 2022, Thibodaux, Louisiana.

“It seems—one of the issues that tribes deal with in this country is the issue of recognition. We’ve subdivided recognition into state recognition and federal recognition, and each stage of recognition offers a certain level of funding and support. In Louisiana, we don’t see any funding or support for state-recognized tribes. And often when we try to work with state governments or state agencies, there are conversations that are had and people [state officials] say, ‘Well, you need to be federal. We can’t really do that because you need to be federal, even if it’s a state-level issue.’ So, even though it’s not a specific project, on a broader, more systemic level, when tribes try to engage with state agencies or engage with the state overall, the problem is that people aren’t exactly recognizing tribal people as sovereign people or people in general.”

SOURCE: Chief Devon Parfait, Grand Caillou Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw. Workshop 3: Community Viability and Environmental Change in Coastal Louisiana, July 2022, Thibodaux, Louisiana.

“And I’m here to say that there is no such thing as management of that process unless the people who have come to the determination that they need to relocate to another area are in charge of that process. If anyone, at the end of the day or the beginning of the day, thinks that, you know, they know better how to and where to relocate people, and I think that’s a flaw. That’s a flaw in the whole plan. So, it’s the people that have come to that determination, they need to be the ones in charge of the entire process. Because you are not just moving from one location to the other, you have to have considerations for how that move will translate into the future.”

SOURCE: Elder Rosina Philippe, Atakapa-Ishak/Chawasha Tribe and President of the First Peoples’ Conservation Council. Workshop 3: Community Viability and Environmental Change in Coastal Louisiana, July 2022, Thibodaux, Louisiana.

BOX 7-8

Case: TEK Used to Aid Restoration Decisions

TEK—that is, local knowledge of an area gathered and held by Indigenous residents—has been successfully incorporated into decision making for coastal restoration in some instances (Bethel et al., 2014). Matthew Bethel and his team blended geospatial technology with the social sciences to assist the Atakapa-Ishak Tribe of southeast Louisiana in Grand Bayou. The locals involved in the project took Bethel’s team out on boats and showed them places where they had seen the largest changes in the marshland that impacted their ability to provide for their families. In turn, Bethel introduced them to other scientists working in the field in a systematic engagement process, so that residents could ask questions and offer input about ongoing projects. Bethel’s efforts, in addition to being scientifically valuable, created a feeling of mutual respect between those living in Grand Bayou and others also working to save it. His team integrated the knowledge in a format that state coastal restoration planners could understand and use. For example, they created mapping products that combined scientific and TEK-based datasets to identify specific geographic locations and features in need of focused restoration by government agencies. The Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority of Louisiana saw the value in this project for decision support and secured funding to broaden the scope of the study, both geographically, to include the entire Barataria Basin, and in types of data collected. Having TEK in a format that the state could use as an overlay onto existing restoration layers allowed it to easily be used in the decision-making process (see also Hemmerling, Barra et al., 2020; Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium, 2021).

Community Knowledge and Protocols