Community-Driven Relocation: Recommendations for the U.S. Gulf Coast Region and Beyond (2024)

Chapter: Summary

Summary1

Between 1980 and July 2023, 232 one-billion-dollar disasters occurred in the U.S. Gulf Coast Region, with the number of disasters doubling annually since 2018. These included drought, flooding, freezes, severe storms, tropical cyclones, wildfires, and winter storms. Such events amplify displacement risks, whether short-term or permanent, and in some cases challenge the possibility of communities remaining in place as the sea rises and the land subsides across the region. These climate-related disasters also interact with chronic stressors stemming from both historic injustices and ongoing exposures to environmental pollutants from the very industries that employ many Gulf Coast residents. Compounding events, such as a hurricane coupled with a chemical spill, are threat multipliers. Yet year after year, disaster after disaster, housing and infrastructure are rebuilt in these same areas for reasons that range from deep cultural attachments and economic incentives to a lack of relocation options, among others.

As disaster recovery costs escalate, state and local governments cannot keep up, while federal recovery programs fall short of state requests for assistance. As households struggle to recover from one storm before the next one hits, families experience chronic stress with few opportunities for respite. Stress exacerbates other pre-existing health conditions even as exposure to flooding and extreme heat aggravate those same conditions. These circumstances present an untenable long-term cycle of cumulative, compounding, and cascading risks, markedly increasing vulnerability.

___________________

1 This summary does not include references. Citations for the information presented herein are provided in the main text.

Addressing these growing challenges requires new ways of planning in anticipation of disasters and their growing potential for displacement. While disaster displacement is not a new phenomenon, the rapid escalation of climate-related disasters in the Gulf increases the urgency to develop pre-disaster policies to mitigate displacement and decrease suffering. Moreover, climate-related displacement amplifies other types of disparities, including ongoing inequities and the histories of hostile displacements over the settlement of the region. This history coupled with the need to address climate-related disasters and their growing impacts on Gulf communities presents a need to improve relationships among people and institutions through participatory planning processes that emphasize trust building and center community well-being and community priorities.

Neither the region nor the nation has a consistent and inclusionary process to address risks, raise awareness, or explore options for relocating communities away from environmental risks while seeking out and honoring communities’ values and priorities. Even with the recently released National Climate Resilience Framework from the White House in 2023, there is a systemic gap in understanding these issues (e.g., risks, equitable relocation options) as well as lack of procedural justice as the need for relocation options and resources has rapidly outpaced regional and national planning capacities. Herein is the dilemma at the heart of this study: given the need to act quickly and given the history of distrust and inequities in the region, how might we co-create a just process while simultaneously growing trusting and sustaining relationships between the entities and the communities who need to collaborate?

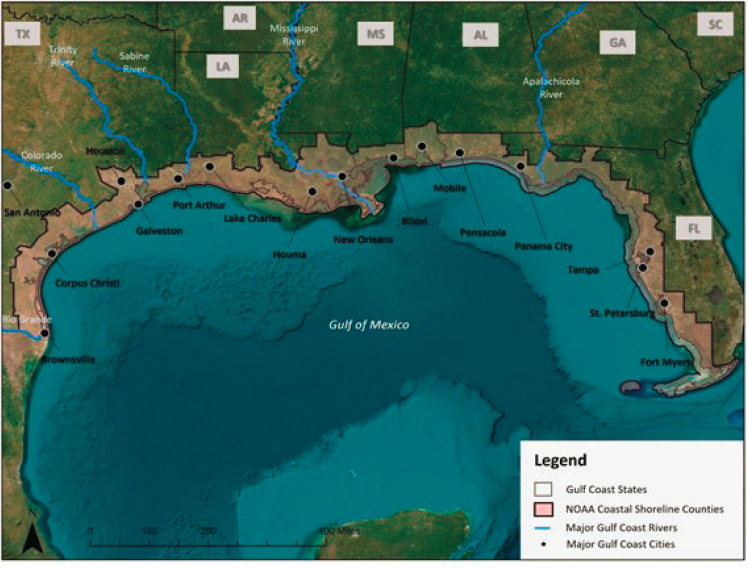

In 2021, the Gulf Research Program of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine initiated a consensus study to examine and analyze the unique challenges, needs, and opportunities associated with managing the relocation of people, infrastructure, and communities away from environmentally high-risk areas. The Board on Environmental Change and Society in the Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education convened a committee of experts to provide in-depth analysis and identify short- and long-term steps necessary for community stakeholders to plan and implement relocation in ways that are equitable, culturally appropriate, adaptive, and resilient to future regional climate conditions (see the full statement of task in Chapter 1, Box 1-1). As part of its charge, the committee held public workshops in the Gulf region that focused on policy and practice considerations, research and data needs, and community engagement strategies. Elevating the voices of individuals and communities on the front lines of climate change was a central focus of these workshops. Testimonials from workshop participants guided the committee’s findings and are interspersed throughout the report. The committee’s work covers the coastal and peri-coastal counties and parishes along the U.S. Gulf Coast,

spanning the states of Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas (see Figure S-1), and draws from case studies and research from other parts of the United States and abroad.

PART 1: INTRODUCING COMMUNITY-DRIVEN RELOCATION

Part 1 delineates the scope of the report and the committee’s interpretation of the study charge (Chapter 1), gives an overview of the complex climate change–related threats to the Gulf region that will continue to compel individuals and communities to relocate for the foreseeable future (Chapter 2), and concludes with national and international case studies of relocation strategies (Chapter 3).

Terminology about relocation is important. Communities have emotional, symbolic, and physical attachments to place. These attachments, therefore, deserve consideration in the use of terminology that describes adaptive solutions, such as relocation. In describing adaptive solutions to reduce displacement, some researchers and policy makers have used the term “managed retreat” for organized efforts to relocate and resettle

SOURCE: Committee generated from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/inport/item/66112

individuals and communities threatened by climate change and to move infrastructure away from hazardous areas (Chapter 1). The committee does not believe this term captures the key element of any adaptive solution, which is the equitable and effective involvement of the affected communities at every stage of the relocation and resettlement process.

The term “managed retreat” may trigger emotion and trauma because it is associated with intergenerational memories of violent relocations like the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Furthermore, some communities interpret “retreating” as a loss of homeland, while others see it as a movement toward safety. Because the term and concept of “managed retreat” have different assumptions for different communities, this report uses “community-driven relocation” to encompass both the abstract concept and key social dimensions that illuminate opportunities and practices that implement relocation in equitable, culturally appropriate, adaptive, and participatory and empowered ways. A community-driven approach contrasts with the largely ad hoc and post-disaster reactionary approach to mitigation and adaptation. Ad hoc approaches impede the fostering of trust and create barriers to genuine collaborative engagement and decision making. Instead, community-driven approaches could address what may be entrenched perceptions of government and institutionalized factors underpinning vulnerability. To denote the communities that people are leaving, this study uses the term “originating community”; to denote communities where people are relocating to, the committee adopted the term “receiving community.” The committee recognizes the importance of shared decision making in any policy-supported and institutionalized process of community-driven relocation, meaning

- the originating community is at the center of decision making about relocation and needs for well-being;

- policy and material supports are provided for optimally enlarging a community’s option for a safe landing in the receiving community or relocation destination; and

- supports are provided for the receiving community, including land-use planning, economic investments, and social resilience.

The U.S. Gulf Coast Region is experiencing increasingly intense tropical cyclones, which bring strong winds, heavy rain, storm surge, and high waves, as the sea level rises with global warming. Chapter 2 begins with an overview of the complex climate change–related threats to the Gulf region that will continue to compel relocation and concludes with displacement projections and the disproportionate impacts on minoritized and at-risk groups.

The report does not focus on climate thresholds or any one hazard but instead examines processes for how, when, why (and why not), and

where people and infrastructure relocate, which could be from a variety of hazards. In other words, the committee chose to acknowledge the drivers of migration and displacement, specifically in the Gulf Region (e.g., coastal hazards), but to focus the study on relocation challenges, opportunities, policies, lessons learned, and processes (e.g., decision making). To this end, Part 1 concludes with a brief history of relocation efforts in the United States from the late 1800s onward and a selection of case studies of recent relocation efforts in the United States and abroad (Chapter 3).

Conclusion 2-1: Future Gulf Coast displacements are difficult to project because few models exist to fully characterize the extent of regional risks from climate changes, subsidence, and industrial impacts. Lacking more accurate exposure and risk estimates at the scale of population displacement, the Gulf Coast currently fails to hold a shared understanding of its risks and the enormity of the planning challenges that it faces. Recognizing the scale of threat warrants the equivalent of a regional displacement vulnerability risk assessment and resulting preparations for region-wide population and industry relocations.

PART 2: UNDERSTANDING RELOCATION IN THE U.S. GULF REGION

Part 2 contains Chapters 4 through 8. Chapters 4 and 5 principally focus on the U.S. Gulf Coast Region, including its history (Chapter 4), socioeconomic demographics and recent/projected in-migration patterns, and “community profiles”—compendiums of quantitative data from federal agency datasets (e.g., Federal Emergency Management Agency’s National Risk Index, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s EJScreen) of communities the committee engaged during the study. The datasets are accompanied by first-hand testimonials from coastal residents, which give ground truth to the quantitative datasets and articulate community needs in terms of climate services and other support. The committee’s approach to understanding community experiences and how risks influence relocation decision making underscores the utility of pairing quantitative and qualitative information (Chapter 5). Chapter 6 then broadens out from the Gulf region to discuss the significance of community well-being in the context of relocation and the importance of communication, participation, and engagement in discussing, planning, and implementing community-driven relocation (Chapter 7). While originating and receiving communities are discussed throughout the report, Part 2 concludes with a more detailed focus on their considerations and needs (Chapter 8).

The Critical Importance of History and the Current Realities of Gulf Coast Communities

The U.S. Gulf Coast is a dynamic and evolving socioecological system. Throughout history, human movement and adaptation to this system have been driven by the knowledge and expertise of Indigenous and place-based communities, the ramifications of colonization and enslavement, environmental fluctuations, the politics of development, and the ascendancy of the petrol-chemical industrial sector (Chapter 4). Indigenous people; immigrant groups from Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, Acadia (present-day Canada), and Asia; and other traditional populations have adapted to the environmental conditions of the Gulf and exhibited remarkable community resilience under harsh conditions (Chapter 5).2

Conclusion 4-1: After European conquest and the extermination and enslavement of Africans and Indigenous people in the Gulf region, the Indian Removal Act of 1830 began an institutionalized process of displacement and forced migration of Indigenous people from their homelands. Other groups in the region have histories of forced migrations and displacement (e.g., people from Acadia, Vietnam, Cuba). Descendants of these groups that currently face the prospects of relocation report that historical injustices influence their response to current climatic and environmental changes on the Gulf Coast.

Conclusion 5-2: Despite environmental threats, Gulf Coast populations have increased steadily for 50 years. Movement toward the coast has increased construction and real estate values and thereby enhanced risk, while contributing to gentrification. Traditional placed-based communities with long relationships to coastal lands and waters have expertise, social networks, and skillsets evolved from local knowledge and centuries of resilient behaviors. Place-based communities are often reluctant to relocate because of their unique economic, social, and cultural attachments to place, and they also often lack access to resources if they do want to relocate.

___________________

2 The committee defines “traditional population” as a self-identified group with long-standing residence in a particular place, with livelihoods and other cultural practices that are intertwined with the local environment and resources. It may be Indigenous or have roots in Europe, Africa, Asia, or other parts of the Americas.

Sustaining Community Well-Being: Physical, Mental, and Social Health

The study committee drew from various approaches and methodologies to conceptualize and assess well-being, and identified tools to enhance resilience, social capital, community cohesion, and collective efficacy in the context of climate change and climate-induced displacement and relocation (Chapter 6). A holistic approach illustrates how community well-being and adaptive capacities to respond to climate threats are undermined by preexisting and enduring social and economic health inequities.

Conclusion 6-1: There are discernable linkages between health disparities (e.g., premature death, elevated levels of chronic diseases, poor mental health, inequitable access to health care) and complex socioeconomic disparities (e.g., intergenerational poverty, economic precarity). Equitable and sustained community-driven relocation planning requires agencies (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Department of Housing and Urban Development) to examine these linkages within the context of originating and receiving communities.

Conclusion 6-2: The importance to communities of bolstering mental health and healing emotional distress lies not only in diminished suffering and enhanced coping but also in the social ties and associated social capital that mutually reinforce collective efficacy and social inclusion in processes of adaptation to social and environmental change.

Addressing the traumas, stressors, and dearth of resources as well as enhancing collective and individual psychological resources and strengths are critical prerequisites to providing a foundation for communities to participate in community-driven relocation projects. Therefore, bolstering capacity for well-being in climate-threatened communities is a priority for public health and climate adaptation across the nation (Chapter 6).

Communication, Knowledge, and Engagement

Relocating and resettling is a complex process of change and adaptation that involves more than the physical act of moving. It is a social process that involves the cooperation, coordination, and participation of affected people at the originating and receiving nodes. Yet, processes around relocation often exclude people, neighborhoods, and communities from problem solving and developing adaptive solutions, and often do not support opportunities for collective action. Relocation processes will only be just and

equitable through a community-driven approach, of which participatory planning, access to knowledge, transparency of process and outcome, and shared decision making are core elements (Chapter 7).

Conclusion 7-3: For community-driven relocation, there is a particular need for participatory processes through which community knowledge is sought, brought forth, and used in planning and decision making. Acknowledging the importance of local knowledge and knowledge holders helps build trust and awareness of local perceptions, needs, and capabilities that can facilitate relocation planning, including the reintroduction of local and Indigenous frameworks that may have been eschewed over time.

Conclusion 7-4: Workshop input and findings validate the broad desire for far more substantive, ongoing civic participation/empowerment and leadership capacity that exceeds being “consulted” or “engaged” by considering participants as deciders and co-planners. At the same time, community members and local government leaders are not clear or prepared on how to meaningfully practice participation and incorporate people’s capacity in decision-making processes.

Planning for Receiving and Originating Communities

Community-driven relocation requires significant planning on the part of receiving and originating communities, including how to adaptively manage the resulting open space (e.g., water retention, commemorative sites, wildlife habitat enhancement), the social and financial support needed for relocating communities, and the physical and social infrastructure needed in receiving communities (Chapter 8). In addition to effective communication and engagement of residents in receiving communities, effective preparation entails collaboration between government across jurisdictions (e.g., federal, state, local) and regional planning entities, including data sharing, guiding appropriate adaptation investments in receiving areas (e.g., infrastructure, energy bandwidth, schools), disinvestment in maladaptation in originating areas, and the facilitation of relationships between originating and receiving communities.

Conclusion 8-1: Receiving communities need to have the infrastructure and institutional capacity to provide essential services such as housing, water treatment and water supply, power and fuel distribution, broadband, education, health services, employment, and transportation

for expected population increases. Currently, there is little planning or funding specifically for population relocation.

Conclusion 8-2: Land suitability analysis is a useful tool to help communities identify less hazard-prone areas for potential relocation sites. Although its use in directing relocating communities is so far uncommon, when incorporated into broader city planning efforts it has the potential to help direct people who are relocating to safer nearby areas that are also acceptable to them and that preserve a jurisdiction’s tax base.

Originating communities and/or the land left behind after wholesale community and infrastructure relocation occurs have their own sets of challenges, needs, and opportunities. Setting thresholds is one of the first and most important parts of the relocation process and involves decisions about when to consolidate or reduce municipal services (e.g., waste, postal, fire, police) and decommission infrastructure. Thresholds acknowledge the limits to adaptive capacities—when environmental risks and change become so rapid and transformational that habitation becomes no longer logistically, financially, or safely feasible. Community-driven relocation requires residents to be active participants in discussions about the triggering of thresholds and the pace and timing of disinvestment, decommissioning, and the reduction of services.

Conclusion 8-9: Partnerships between originating and receiving communities can facilitate the collaborative development of policies and plans needed to address the complexities and long timeframes associated with community-driven relocation.

PART 3: FUNDING, POLICY, AND PLANNING

Part 3 of the report continues to broaden out from the Gulf to discuss the current landscape of policy, funding, and planning for relocation (Chapter 9); the associated challenges and opportunities (Chapter 10) of this landscape; and the committee’s recommendations (Chapter 11).

Landscape of Policy, Funding, and Planning

The committee identified a complex web of federal programs, laws, and plans that communities must navigate when pursuing community-driven relocation and considered how to make these more inclusive of and responsive to the needs of originating and receiving communities. A major obstacle is that relocation is currently managed using a “disaster-recovery model,”

meaning that most funding and technical assistance comes episodically as a reaction to a specific disaster or in the form of annual nationally competitive programs rather than being available year-round and allocated based on risk and need to include addressing the root causes of vulnerability. The compressed timeframe in which people are required to act often hampers effective community engagement, collective decision making, and collaborative planning processes needed to address the myriad of complexities tied to community-driven relocation.

Conclusion 9-1: While federal agencies have many of the tools (e.g., funding, capacity) needed to help communities resettle under existing laws, and there are existing programs (e.g., the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities and the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Community Development Block Grant Program) that have facilitated individual households and neighborhoods to relocate, there is currently no interagency coordination to enable community-driven relocation planning at the scale required to address the level of risks in the U.S. Gulf Coast Region. As a result, the existing programs are difficult for households and communities to navigate.

Conclusion 9-7: Moving from a disaster-recovery model to an overall community relocation regime could entail evaluating the potential requirements to transition from a primarily competitive grant-making process to a process that places an increased emphasis on providing year-round funding and ongoing assistance to underresourced and at-risk communities to develop and implement risk reduction strategies, including long-term relocation planning.

Adopting a comprehensive and coordinated adaptive governance approach would plan for uncertainty at the local, regional, and national levels through (a) local planning to ensure that infrastructure and other community needs are met in the originating and receiving communities; (b) regional entities to coordinate relocation that occurs across different jurisdictions; and (c) funding and guidance from higher-level governments to meet local and regional needs.

Overcoming Challenges and Identifying Opportunities

The committee provided an overview of the numerous challenges that households, local and state governments, and other community stakeholders might face when navigating the relocation process (Chapter 10), including shared responsibilities between governments and households; the role

of insurance and its benefits and drawbacks under the current system (e.g., parametric insurance, the National Flood Insurance Program); individual and household eligibility determinations and prioritization in current relocation assistance programs (e.g., per-disaster rulemaking, heirs’ property rights, renter support); and challenges related to the complex and time-consuming process of obtaining funding for a buyout.

Conclusion 10-4: Obtaining funding for a buyout is a complex, time-consuming process that often exceeds the capacity of communities, especially underresourced ones, to act. It requires communities to write an approved hazard mitigation plan, which also takes time and a certain level of capacity and funding, especially if this task is undertaken by a contractor, which is often the case. The complexity of the buyout process also greatly exceeds the adequacy of federal and state resources available to help households and communities navigate the process. Although some assistance programs exist (e.g., the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Advanced Assistance program), they tend to be underutilized.

Conclusion 10-6: Multiple sources of funding may be needed for relocation. It is challenging to combine different funding streams because different agencies and programs (e.g., the Federal Emergency Management Agency Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Community Development Block Grant Program) have different rules and timeframes, and federal funds from one entity may or may not serve as the required match for another entity. Nonfederal match requirements prevent some poorer communities from being able to participate in buyout grants.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR COMMUNITY-DRIVEN RELOCATION EFFORTS IN THE GULF REGION AND BEYOND

The committee arrived at 13 recommendations for community-driven relocation and grouped them into three domains, supported by multiple conclusions: (1) Centering Well-Being, (2) Developing and Sustaining Local Collaborations, and (3) Strengthening Preparations for Community-Driven Relocation. Chapter 11 also contains these recommendations but cross-references the relevant conclusions and chapters, and includes additional supportive text, such as examples of implementation and process.

These recommendations were identified by the committee through information-gathering sessions with Gulf Coast communities and by assessing the landscape of policy and funding. In parallel, agency-led efforts identified similar needs, lending credence to this kind of systemic change,

specifically through the White House’s National Climate Resilience Framework (“Framework”). The Framework identifies opportunities for action for funding, supporting, expediting, and evaluating community-driven relocation and centering well-being in climate resilience and adaptation.3

Centering Well-being

RECOMMENDATION 1: The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Climate Change and Health Equity (OCCHE) and Office of the Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use should support and coordinate efforts across HHS and other agencies with the following objectives:

- Accelerate adoption of task-shared approaches to community mental health care, especially in high climate-impacted areas (e.g., through establishment of payment mechanisms, such as assistance from the Health Resources and Services Administration and scope expansion of Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics). Such approaches should use evidence-supported mental health care, prevention, and promotion methods that community members and community-based organizations can adopt and directly provide.

- Facilitate collaborations among federal agencies, programs, and policies that promote well-being and build community capacity to support mental health, effective empowerment, trust, inclusion, equity, and collective efficacy for adapting to environmental challenges.

- Facilitate regional coordination of the array of public health, health care, and social and mental health services that are required to support the well-being of originating and receiving communities.

- Establish metrics, indicators, and baselines to assess the longitudinal and cross-sectional well-being outcomes of individuals in the context of relocation. These data should be collated with existing data collected by federal agencies (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) and evaluated regularly to improve adaptation governance.

___________________

3 The majority of these alignments appear in Framework in the section Opportunities for Action, under Objective #6, on pages 28–29. More information is available at https://www.white-house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/National-Climate-Resilience-Framework-FINAL.pdf

Developing and Sustaining Local Collaborations

RECOMMENDATION 2: Planning for community-driven relocation should incorporate local perspectives about the histories, impacts, and perceptions of displacements and forced relocations, as well as generational traditions.

- Federal and state agencies (e.g., Federal Emergency Management Agency, Department of Housing and Urban Development, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, state historic preservation and cultural resource agencies) should institute systematic, Gulf-wide community-informed local investigations on how past and current patterns of resilience and adaptation and relevant policies influence attitudes and behaviors toward relocation and resettlement.

- Emergency management and disaster recovery agencies (e.g., Federal Emergency Management Agency and regional and state counterparts), local public works agencies (e.g., water, power, drainage, flood protection), mental and behavioral health care institutes, and transportation planning entities (e.g., local and regional) should reevaluate their plans, expenditures, and strategies to account for discriminatory policies and practices that have exacerbated vulnerabilities, and should institute plans (e.g., the Justice40 Initiative) to redress inequities that have undermined the resilience of communities most likely to face relocation.

RECOMMENDATION 3: Agencies that assist communities with relocation (e.g., Department of Housing and Urban Development, Federal Emergency Management Agency, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and state resilience and community development offices) should foster meaningful partnerships to develop and execute relocation plans in collaboration with communities, including decisions about timing and pace of the relocation process. These agencies should

- develop a consistent co-creation process and work with each community to establish specific communication requirements that include face-to-face interactions; and

- work with locally trusted community-based organizations to build understanding, trust, and enduring relationships with communities to carry out adaptation.

RECOMMENDATION 4: Regional planning entities alongside local public works, planning, and housing authorities, and departments involved in relocation, resilience, and climate adaption efforts should

- account for community-driven relocation (originating and receiving communities) in their planning efforts (e.g., land-use plans, hazard mitigation plans, and economic plans);

- revise and assess relocation strategies based on current and projected climate data and traditional ecological knowledge; and

- conduct land suitability analysis to identify suitable receiving areas, and in doing so, to work with communities to raise their own capacities to understand land suitability.

RECOMMENDATION 5: Federal agencies should engage with local governments and regional planning entities to support community-driven relocation planning across originating and receiving communities. Federal and local government collaborations with regional planning entities should

- work with originating communities to establish threshold agreements for consolidation and regionalization of local governments and tax bases as residents relocate;

- share data about priority receiving communities and assess the impacts of regional population shifts to aid in planning;

- modify federal grant programs (e.g., Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, Flood Mitigation Assistance grant program, Hazard Mitigation grant program) to include making the programming of open space an eligible Federal Emergency Management Agency-funded activity; and

- modify federal and other relocation funding guidelines to include a requirement that households relocate outside Special Flood Hazard Areas and, in turn, work with communities to broaden understanding of what Special Flood Hazard Areas mean to household-level risks.

RECOMMENDATION 6: State agencies, regional planning entities, professional associations, and academic-community partnerships (e.g., land and sea grant universities, minority serving institutions) should provide targeted capacity building and training initiatives to assist state and local governments in planning for community-driven relocation.

RECOMMENDATION 7: Federal government agencies, Gulf Coast state governments, and regional planning entities should increase investments in preparing receiving communities for new residents (e.g.,

infrastructure, energy system capacity, broadband, schools, water supply).

Strengthening Preparations for Community-Driven Relocation

RECOMMENDATION 8: The Federal Emergency Management Agency should, outside of a disaster timeframe, pre-approve properties for acquisition (conduct a single National Environmental Policy Act/National Historic Preservation Act clearance on all such contiguous properties in a flood-prone area) and deem relocation as “cost-effective” in pre-identified communities.

RECOMMENDATION 9: In the short term, federal agencies (e.g., Federal Emergency Management Agency, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Department of Housing and Urban Development) should fund application and implementation assistance through the establishment of hazard mitigation “navigators.” The funding and implementation of navigators should be a part of long-term recovery plans and hazard mitigation plans. These navigators would

- provide the technical assistance needed to help communities apply for and implement a relocation strategy (e.g., through collective buyout programs); and

- provide household- and neighborhood-level planning assistance throughout the relocation process.

RECOMMENDATION 10: Federal agencies that provide relocation funding (e.g., Federal Emergency Management Agency, Department of Housing and Urban Development) should assess the benefits of annual funding to pre-disaster mitigation programs. Actions to improve adaptive capacity should include

- analyzing regulatory and programmatic barriers for converting pre-disaster mitigation programs to include annualized funding for developing adaptive capacities, including relocation; and

- evaluating potential requirements to transition from a primarily competitive grant-making process to a process that provides ongoing assistance to underresourced communities to develop and implement risk reduction strategies using a distribution formula that prioritizes the highest climate risk areas.

RECOMMENDATION 11: Agencies that offer funding for relocation planning, including infrastructure needs (such as Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], U.S. Army Corps of Engineers,

Department of Housing and Urban Development), should streamline the process of obtaining relocation funding, including reimbursements, through the following actions.

In the short term:

- Agencies should coordinate eligibility criteria and timing of requests for proposals.

- Agencies should align the timing of grant delivery and the duration of grants across federal agencies so that applicants have the maximum amount of time to fulfill the grant requirements.

- FEMA should allow people with National Flood Insurance Program coverage, whose homes have received a certain level of damage, to apply directly for a buyout rather than going through the state and then FEMA’s hazard mitigation program.

- Agencies should allow funds from partnering agencies to be used as matching funds to the main federal source (i.e., the disbursing agency). States should also provide funding matches to communities for grants that require a nonfederal partner.

- The Council on Environmental Quality should convene agencies to develop a memorandum of understanding to coordinate construction, utility provision, and the environmental review process under the National Environmental Protection Act for relocations at the scale of a neighborhood or larger.

- Agencies should create an interagency mechanism, such as a single relocation grant application platform (e.g., the Universal Application for Disaster Survivors), that is accessible by states, tribes, municipalities, and households, and establishes a process to triage the applications and direct them to the most appropriate agency. The process should include step-by-step communication with the applicant for transparency and tracking.

In the longer term:

- Agencies should develop and maintain, across jurisdictions, an information clearinghouse connecting users to existing and new resources necessary to conduct a relocation program. This repository should be controlled by an operations center that includes the services of skilled consultants, planners, mediators, and stakeholders who have experience dealing with diverse interests and navigating issues that arise during cross-stakeholder discussions about relocation.

RECOMMENDATION 12: The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), through the leadership and engagement of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs of the Office of Management

and Budget, should revise its benefit-cost analysis process. This should include

- developing a rubric that accounts for a community’s qualitative values, characteristics, and root causes of vulnerability, such as social cohesion, social capital, political disenfranchisement, linguistic isolation, and collective efficacy, among others; and

- extending FEMA’s recent temporary revisions to the benefit-cost analysis for the fiscal 2022 application cycle of Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities and the Flood Mitigation Assistance grant program.

RECOMMENDATION 13: Federal programs involved with community-driven relocation (e.g., Federal Emergency Management Agency, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Department of Housing and Urban Development) should

- increase acquisition payments to property owners so they can afford a comparable home in a safe location;

- provide relocation assistance to renters, and mobile or manufactured homes; and

- use management costs to support buyout grant offers to property owners above typical pre-disaster fair market values.

This page intentionally left blank.