Community-Driven Relocation: Recommendations for the U.S. Gulf Coast Region and Beyond (2024)

Chapter: 6 Sustaining Community Well-Being: Physical, Mental, and Social Health

6

Sustaining Community Well-Being: Physical, Mental, and Social Health

This chapter discusses the following:

- Definitions and frameworks for a holistic approach to well-being, including capacities for subjective well-being and capabilities for action

- Pre-existing, continuous, and new impacts to well-being, including mental health impacts, in the context of climate change and displacement

- Enhancement of well-being through task sharing and nurture effects

- Relocation in the context of social capital and place attachment

INTRODUCTION

Previous chapters presented an overview of historical and current injustices (e.g., enslavement, isolation, political disenfranchisement). The summaries of community profiles in Chapter 5 (and the full profiles in Appendix C) demonstrate that these injustices are compounded by a range of vulnerabilities (e.g., social, health, economic), current climate and environmental hazards, and a history of disastrous climate events. The present conditions of these communities collectively contribute to reduced adaptive capacity and resilience in response to climate change, creating a strong need for more support mechanisms to improve and ensure that communities can cope with

and adapt to the additional stresses of the potential need to relocate (as well as other responses). Ultimately, heightened vulnerability compounds risks and compromises community well-being, the focus of this chapter.

Well-being has long been recognized as an essential component of health. The World Health Organization (WHO) made a critical link between well-being and health in its definition of health as “a state of complete physical, social and mental well-being and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity” (WHO, 1946). While well-being is a critical component of health, it is sometimes missing from conversations about health care and public health (cf. Eiroa-Orosa, 2020).

Well-being can be broadly defined as how people feel and how they function physically, socially, and psychologically (Jarden & Roache, 2023). In this report, we define physical well-being as maintaining a healthy lifestyle, access to health care, regular sleep, eating well, adequate housing, exercise, and avoiding exposure to harmful substances (Capio et al., 2014). We define social well-being as social connectedness, “the degree to which individuals or groups of individuals have and perceive a desired number, quality, and diversity of relationships that create a sense of belonging and being cared for, valued, and supported” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2023; Holt-Lunstad, 2022; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021, 2022b). Finally, we define psychological well-being as several aspects of health-related quality of life, thriving, and several psychological dimensions, including “positive emotions and moods (e.g., happiness); the relative absence of negative emotions, moods, and states (e.g., stress, sadness, loneliness); life satisfaction; sense of meaning and purpose; quality of life; and satisfaction with other life domains (e.g., work satisfaction, satisfaction with relationships)” (Feller et al., 2018, p. 137). In this chapter, the committee asserts that centering the physical, social, and psychological well-being of individuals and communities, as well as the relationships inherent in and consequential to both spheres, can foster and enhance the capacities and capabilities of communities, their institutions, and their organizations (e.g., local government, health institutions) in the context of displacement and community-driven relocation.

This chapter begins with a transdisciplinary overview of health and well-being, delineating various conceptual framings of well-being in the context of environmental threats and relocation that construct, represent, and value subjective and objective measures of well-being. Next, we review the evidence-based literature about the application of a well-being lens in the context of the pre-existing, continuous, and new climate change and displacement impacts on communities. Lastly, the chapter presents arguments of how social capital and place attachment, which are strongly linked to well-being, factor into community decision making regarding the process of relocation. Overall, this chapter focuses attention on how centering and

prioritizing well-being helps to understand, navigate, and prioritize mental and psychological health, and to identify tools to enhance resilience, social capital, community cohesion, and collective efficacy. Many of these tools reside within cultural legacies; Indigenous sovereignty; and attachment to, reciprocity with, and relationship to place—all of which exist within the context of increasing climatic extremes, uncertainty, displacement, and relocation processes.

The committee engaged with Indigenous individuals and representatives of Indigenous perspectives, and acknowledges that the well-being frameworks included in this report (e.g., Seven Vital Conditions, Building Resilience Against Climate Effects [BRACE]) do not include all the distinct cultural models and dimensions of health and well-being that exist throughout the world or even in the U.S. Gulf Coast region, including the multitude of models by Indigenous groups. However, we learned that specifically Indigenous concepts and experiences of well-being can exist at the interface of elements such as identity, place, culture, and community, in concert with the surrounding world (e.g., land, water, animals, ancestors, ecosystems, vibrant matter, and cosmologies; King et al., 2009; United Nations, 2023). We hope that this chapter incorporates these elements in ways that acknowledge the interactions we shared and the information we learned from diverse models of well-being and from participants at information-gathering sessions.

A HOLISTIC APPROACH TO WELL-BEING

A holistic approach to well-being discerns linkages between health disparities (e.g., premature death, elevated levels of chronic diseases, poor mental health, inequitable access to health care) and complex socioeconomic disparities (e.g., intergenerational poverty, economic precarity). These linkages are in large part perpetuated through failures, or an inability, to address important elements of community well-being, in particular, social capital, public goods, and emotional health—elements that sustain and mutually reinforce hope and collective efficacy (Graham, 2017, 2023). A holistic well-being approach has been promoted as an important policy focus for governments and an alternative to a dominant focus on the generation of economic growth (e.g., see Dalziel et al., 2018; Sen, 1983, 1999), which may come at the expense of well-being or be undermined by conditions of poor well-being, such as high vulnerability to climate change threats. Prioritizing well-being and its outcomes as the primary aim by which economic choices are judged and by which economic investments are made has proven feasible and scalable (see Brown et al., 2017; Frijters & Krekel, 2021; Hardoon et al., 2020).

Climate change presents a multitude of challenges to the well-being of individuals and communities. A holistic view shows how community well-being and adaptive capacities to respond to climate threats are undermined by pre-existing social and economic health inequities resulting from historical racial and social discrimination and marginalization, as discussed in Chapters 4 and 5. These conditions, in turn, have placed many poor and minoritized coastal communities in harm’s way (i.e., in more flood-prone areas, in housing that is less protective, and in communities where there has been a failure to invest in levees and other community-level protective measures; Morello-Frosch & Obasogie, 2023). Climate vulnerability in communities is a function of “baseline vulnerabilities (health, social/economic, infrastructure, and environment)” in the context of significant “climate change risks (health, social/economic, extreme events)” (Tee Lewis et al., 2023, p. 1); therefore, climate vulnerability is an exacerbation of already-existing challenges to community well-being.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS’s) efforts to recognize the interrelations between climate change, health equity, and environmental justice are visualized below in Figure 6-1, which draws from the U.S. Global Change Research Program’s (USGCRP’s) Fourth National Climate Assessment (Reidmiller et al., 2018) and the Climate and Health Assessment (Crimmins et al., 2016), and particularly recognizes how climate-induced health effects disproportionately affect underresourced communities and how these impacts are compounded by existing environmental and social contexts.1 These interrelations offer a productive entry point to examine ways for the broader community of health service providers, including community health workers, to take a more active role in connecting all aspects of well-being in climate adaptation planning.

A shift to a well-being approach means departing from a pre-disaster planning and post-disaster recovery paradigm to an ongoing project of sustaining community ties, collective efficacy, and participation. These three components nurture and rely on emotional, psychological, and behavioral strengthening. Community health (including well-being) is critical to the sustaining of community agency and to being able to adequately navigate the huge range of decisions, challenges, and transformations that U.S. Gulf Coast communities increasingly face as they cope with environmental change.

Resources for this kind of participatory and holistic approach to community building are readily available to support such work. In the United States, for example, the integration of well-being science and community strengthening has been implemented at scale through the work of the Well

___________________

1 More information about the HHS initiative for climate change, health equity, and environmental justice is available at hhs.gov/climate-change-health-equity-environmental-justice/index.html

SOURCE: Crimmins, A., Balbus, J., Gamble, J. L., Beard, C. B., Bell, J. E., Dodgen, D., Eisen, R. J., Fann, N., Hawkins, M. D., Herring, S. C., Jantarasami, L., Mills, D. M., Saha, S., Sarofim, M. C., Trtanj, J., & L. Ziska (Eds.). (2016). The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://health2016.globalchange.gov/

Being in the Nation (WIN) Network.2 Through an effort of more than 100 organizations and communities, with support from the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS), the work of WIN has yielded comprehensive core measures that are accessible and relevant to communities, government, and other entities.3 These core measures include the well-being of people, the well-being of places, and equity.4 WIN created a template for community coalition-led actions for advancing population well-being through addressing “The Seven Vital Conditions for Well-Being,” a framework that combines major determinants of health with the properties of

___________________

2 More information on WIN is available at https://winnetwork.org/

3 More information about NCVHS is available at https://ncvhs.hhs.gov/about/

4 More information is available at https://www.winmeasures.org/

places and institutions that together advance a collaborative and cross-sector approach to well-being. The seven vital conditions included in the framework are reliable transportation, thriving natural world, basic needs for health and safety, humane housing, meaningful work and wealth, and lifelong learning, with belonging and civic muscle at the center.5

Together, the seven vital conditions and the WIN template for community action were the foundation for a federal comprehensive strategy, the Federal Plan for Equitable Long-Term Recovery and Resilience (Federal Plan for ELTRR), a cross-agency effort to “equitably achieve enhanced resilience.”6 Implicit within this plan is the need for engaging public health, writ large, in all aspects of community-driven relocation planning. Building on the Federal Plan for ELTRR, the first ever White House National Climate Resilience Framework (2023) uses a “people-centered principle” to “[p]osition the well-being of individuals, families, communities, and society at the center of [climate resilience] goals and solutions” (p. 7). The framework’s objectives assert that both the built environment and nature-based solutions are also investments in community well-being, and that investments in a community’s health care system—including outreach networks—will “improve not just the overall health and well-being of community members during normal operations, but also their capacity to mitigate, adapt to, and recover from the compounding impacts of extreme weather events and long-term climate stresses” (p. 26).7

CDC’s framework, BRACE (see Figure 6-2), is another tool that can be used in taking a well-being approach to climate adaptation. This framework outlines a five-step process for health officials to develop strategies and programs to anticipate, prepare for, and respond to a range of climate change impacts on health and well-being (CDC, 2022) more effectively. Alongside epidemiologic analysis, the BRACE process also involves the inclusion of climatological data and projections (e.g., future temperature and precipitation) in public health planning (CDC, 2022). The inclusion of updated climatological science strengthens the process of informed risk

___________________

5 Each of the seven vital conditions for well-being are broad categories. For example, the condition of “civic muscle” includes social support; freedom from stigma, discrimination, and oppression; collective efficacy; and spiritual life, among others. The condition of “reliable transportation” also includes efficient energy use. The condition of “thriving natural world” includes freedom from heat, flooding, wind, radiation, earthquakes, and pathogens as well as access to natural spaces, among others. More information about these conditions is available at https://winnetwork.org/vital-conditions

6 More information about the Federal Plan for ELTRR is available at https://health.gov/our-work/national-health-initiatives/equitable-long-term-recovery-and-resilience

7 More information about the National Climate Resilience Framework is available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/National-Climate-Resilience-FrameworkFINAL.pdf

SOURCE: CDC. (2022). CDC’s Building Resilience Against Climate Effects (BRACE) Framework. https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/BRACE.htm

communication about climate hazards for the health sector, thus enhancing a sustained assessment of current and projected risks for communities in environmentally high-risk areas.

A multitude of community resilience frameworks and models, such as BRACE, can be utilized to assess and enhance well-being. It is beyond the capacity of this report to provide a comprehensive overview of these works, but relevant examples could include a perspective on community resilience as a process that links a network of adaptive capacities (Norris et al., 2008); a place-based model for understanding disaster resilience (Cutter et al., 2008); and a reimagining of community resilience in terms of equity and sustainability (National Academies, 2023b). In the context of climate and displacement, there is also much to learn from recent critiques of the resilience concept by climate justice scholars and practitioners (see Moulton & Machado, 2019; Porter et al., 2020; Ranganathan & Bratman, 2019).

Another resource that provides a community well-being perspective on health and climate change is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Social Vulnerability Report (2021b), which delineates six impacts that adversely affect health either directly or indirectly: (1) air quality, (2) extreme temperatures, (3) negative impacts of extreme temperature on work, (4) coastal flooding impacts on traffic, (5) coastal flooding impacts on property, and (6) inland flooding impacts on property. These impacts undermine the key conditions for well-being and adaptation (as outlined above) by degrading the physical, natural, and social capital that communities possess and rely upon to sustain themselves and effectively respond to stress and change.

Developing a holistic understanding of community well-being and centering it in climate adaptation planning processes allow for more equitable, community-driven responses. Improving well-being is a critical part of this; the next section defines and examines a capabilities and capacities approach to improving well-being and adaptive capacity.

Capabilities for Subjective Well-Being and Capacities for Action

Climate adaptation relies on psychological and behavioral adaptation—that is, changes in mindsets and ways of relating to others and nature, reflecting what has been detailed as competencies and strengths of needed “inner-outer transformation” (Wamsler et al., 2021). These shifts are seen as essential for shifts in how societies work in relation both to how people treat each other and to how they treat the planet. Above, we discuss the benefits of understanding climate adaptation from a holistic well-being perspective; here, we discuss how well-being itself might be conceptualized and pursued using a capabilities and capacities approach. Such an approach to the improvement of well-being means working toward social and political conditions that, as much as possible, center and support the abilities of individuals and communities to achieve well-being. This approach specifically incorporates two interrelated domains—capabilities for subjective well-being and capacities for action—that are particularly relevant to our conclusions and recommendations for communities to manage and navigate the conditions and prospects of relocation.

- Capabilities for Subjective Well-Being, or How People Are Feeling. Taking a capabilities approach to the subjective well-being of individuals involves enriching and enabling opportunities for people to socially and emotionally bond, trust, engage reciprocally, and have satisfaction with their lives and their mental and

- emotional states—essentially, to create conditions that allow for the improvement of how people are feeling. Conditions within this domain have critical health implications, underpinning socioemotional states including despair, optimism, emotional validation and support, distress, and trust (or lack of it). And, the fulfillment (or not) of these capabilities plays a significant role in premature death, violence, intergenerational poverty, reduced educational success, and civic conflict (Fiedler et al., 2021; Graham, 2017, 2023).

- Capacities for Action. At a community level, well-being is dependent on the capacity for group action and problem-solving strengths (e.g., social capital and cohesion, collective efficacy, shared sense of place; HHS, n.d.). The importance of these capacities and actions in maintaining community well-being for equitable and effective climate adaptation highlights the need to broaden understanding of how communities can prepare for potential displacement or relocation in a socially interconnected and community-centered way. Alongside capabilities for subjective well-being, this domain rests on questions of whether individuals live in conditions that allow them to act on and realize the lives they desire: the actions that enable participation, inclusion, and individual and collective agency, and how these actions are promoted and enacted.

Understanding well-being along these two domains (how people are feeling and their capacity for action) and addressing the challenges that often comprise them is key to understanding and addressing what individuals and communities can withstand, including what actions can be harnessed when relocation is imminent. Importantly, however, strengthening well-being is not an episodic strategy only relevant when the specter of relocation looms. Rather, centering well-being can be a “new normal” for community-driven climate adaptation. In the current context of decision making about relocation, the implementation of well-being frameworks can consist of adapting policies that incorporate and strengthen a community’s existing social capabilities (e.g., socioemotional bonding, trust, reciprocal engagement) and capacities for actions (e.g., social capital and cohesion, collective efficacy, shared sense of place). As Hardoon et al. (2020) have articulated, “Using a well-being ‘lens’ highlights complex problems that require cooperation and joint strategies to tackle. Improvements to our lives can also be bolstered when we design interventions to maximize the impact on all aspects of our well-being, rather than a narrow focus on a specific target” (p. 7).

Thus far, this chapter has defined “well-being” and described its various conceptual framings in the context of environmental threats and relocation,

emphasizing the importance of a community’s existing social capabilities (e.g., socioemotional bonding, trust, reciprocal engagement) and capacities for actions (e.g., social capital and cohesion, collective efficacy, shared sense of place). In the following sections, we describe pre-existing, continuous, and new impacts to well-being from climate change and climate-induced relocation, and examine practices that can promote individual and community well-being in this context.

PRE-EXISITING, CONTINUOUS, AND NEW IMPACTS ON WELL-BEING

The challenges facing communities contemplating relocation are the result of current processes of displacement and migration, including the culmination of human and ecological precedent and serial events that can exacerbate mental, emotional, and physical distress and, in this, undermine community well-being. In the realm of mental health, for example, this can be seen in the growing body of research on mental health and displacement, which suggests that the effects of climate change interact with and affect the preconditions and current conditions that determine imminent consequences of displacement, as well as impending decisions to relocate (Adams et al., 2009; Lamond et al., 2015; Lawrance et al., 2021; Shultz et al., 2019). These lived experiences underscore how climate and environmental changes profoundly impact individuals and communities in their decision making for migration and relocation. First-hand testimonials from workshop participants (see Box 6-1) attest to the intersection of climate change impacts, displacement, and well-being.

Collectively, these stressors, which operate at individual and community levels, are known as “social determinants of health”8 and are often compounding and build on existing traumas (including historical traumas detailed in Chapter 4), vulnerabilities, and a lack of capacity to cope, such as the following:

- Pre-existing and Long-Term Environmental Issues. Toxins from petrochemical facilities; exposure to airborne toxins from marine, human, and construction “waste” incinerators in or near communities; contaminated food resource pools (gardening, fishing, hunting); chemical exposure to up-stream fertilizers and pesticide deposits in excavated and dredged materials; exposure to

___________________

8 More information about the social determinants of heath is available at https://nam.edu/programs/culture-of-health/young-leaders-visualize-health-equity/what-are-the-social-determinants-of-health/

BOX 6-1

Workshop Testimonials: Mental Health

“And then you have the mental health issue. Post-traumatic stress syndrome, anxiety, and depression are very rampant in people that have to relocate from one area to another because of extreme weather events. Suicide is on the increase in people that have moved from or have been exposed to a severe weather event. Substance abuse is significantly up in people that are suffering from these events. And interpersonal violence, such as violence against women and violence against children, also increases in severe weather events.”

SOURCE: Kenneth Bryant, Founder and Chief Executive Officer of Minority Health Coalition of Pinellas, Inc. Workshop 2: Opportunities and Challenges of Climate Adaptation on Florida’s Gulf Coast, July 2022, St. Petersburg, Florida.

“And so, just as a community, our mental health is really suffering right now. And […] you know, people are coping in whatever ways they’re able to cope. We do need some serious programs across the board. Because I know for even me […] because we were out there every day driving down the roads [after Hurricane Ida]. And we would say we’re really going to need some counseling after this. Because we were fine, but when you talk to those people and you pull that energy in, you have no choice. I mean, it was horrifying and sad. I know I still didn’t get mental help. But I probably need it because it was tough. It was tough. And you just move on. You know, you just move on, for us, helping people. We just forged on. But there were so many people that we had to refer. And we were lucky enough to have some counselors that were willing to do it for free.”

SOURCE: Bonnie Theriot, Resident of Houma, Louisiana. Workshop 3: Assisted Resettlement and Receiving Communities in Louisiana, July 2022, Houma, Louisiana.

“I would like to weigh [in] on this issue [of mental health] by lifting up the name of Sharon Hanshaw of East Biloxi because she was an African-American hairdresser who found herself on a rooftop during Hurricane Katrina. The next day she became one of the most significant advocates for climate resilience and justice across the Gulf. The advocacy and community work she took up became very difficult to sustain and ultimately, I believe, it was that work that caused Sharon at a very young age to have a stroke, and then another stroke, and then to pass away. She is one example of many of people whose physical and mental health as community caretakers in an inhospitable context of not just natural disasters but manmade disastrous non-recoveries, living in toxic contamination adjacent to their communities, etc., bear the additional physical and mental assault that this advocacy work entails. So, volunteer caretakers, or otherwise, that are themselves not getting taken care of as they care for others is a worse danger than even sea level rise.”

SOURCE: Derrick Evans, Executive Director, Turkey Creek Community Initiatives in Gulfport, Mississippi, and Gulf Coast Fund for Community Renewal and Ecological Health (2005–2013). Virtual Focused Discussion: Mississippi and Alabama Gulf Coast Community Stakeholder Perspectives on Managed Retreat, March 2023.

- formaldehyde from the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA’s) Hurricane Katrina trailers; etc.

- Individual and Community Trauma. Experiences of weather-related disasters that have resulted in economic damages, higher rates of physiologic (allostatic) stress, chronic diseases, and excess morbidity and mortality in communities.

- Mental Health Impacts from Climate Change and Climate-induced Relocation. Repeated exposure to climate harms that are simultaneously episodic, chronic, and anticipated, causing stress mediated by both allostatic load and post-traumatic stress.

Pre-Existing and Long-Term Environmental Health Issues for U.S. Gulf Coast Communities

As described in Chapters 4 and 5, and above, U.S. Gulf Coast communities have been exposed to decades of environmental injustices. Such long-term hazardous and life-threatening conditions include (but are not limited to) chemical, paper, and petroleum refineries; gas and electric production facilities (Bullard, 1983, 2000); airborne toxins from marine, human, and construction “waste” incinerators in or near communities impacted by the BP Oil Spill (Burke & Dearen, 2010); ground contamination from Superfund sites and contaminated food resource pools (e.g., gardening, fishing, hunting) resulting from Hurricane Harvey (Biesecker & Bajak, 2017; Carter, 2017; Page, 2017; Potenza, 2017); chemical exposure to up-stream fertilizers and pesticide deposits in excavated and dredged materials (e.g., from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Mississippi River and Mobile Bay dredging/mitigation projects; Carse & Lewis, 2020); and exposure to formaldehyde from FEMA’s Hurricane Katrina trailers (Murphy et al., 2013; Smith, 2015).

These pre-existing and long-term social, economic, and environmental traumas and stressors have negatively impacted well-being, thus depleting individual and collective capacities to cope with or respond effectively to the adverse conditions that underlie climate-induced relocation considerations. Historical traumas and stressors may compound and amplify chronic conditions and jeopardize community-driven relocation planning. During a virtual discussion with residents and stakeholders from Alabama and Mississippi Gulf Coast communities,9 testimony from Barbara

___________________

9 Comments made to the committee on March 30, 2023, during the information-gathering session; see https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/03-30-2023/virtual-focus-group-mississippi-and-alabama-gulf-coast-community-stakeholder-perspectives-on-managed-retreat

Weckesser of Pascagoula, Mississippi, demonstrated how the proximity to facilities with toxic emissions diminishes community well-being: “[W]e’re a fenceline community and we’re working to accomplish a buyout; we have flooding and industry pollution. Many residents are taking chemo and there are major health and flood issues while the industry continues to pollute. We just want to be able to survive and live.”

Neighborhoods now located immediately adjacent to refineries (i.e., “fenceline communities”) existed long before the industries whose toxic emissions poisoned air, water, and land (e.g., the community of Port Arthur, Texas; see White, 2018). Yet, political economies consider such neighborhoods as “sacrifice zones,” or zones that, within the benefit-cost framework, present no value to corporate stockholders (Bullard, 2000; Bullard & Wright, 2012). Moreover, environmental hazard events (e.g., leaks, explosions, air pollution) often result from the impacts of natural hazards, like hurricanes, and cause multiple displacements, which, in turn, intensify mental and physical health problems, including anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and suicide (Reuben et al., 2022). For example, in 2020, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Lake Charles, Louisiana, was impacted by two major hurricanes within six weeks. Hurricane Laura came ashore in Louisiana with 150 mph winds on August 27, followed by Hurricane Delta on October 9 with 100 mph winds, only 12 miles east from where Hurricane Laura made landfall. The storms destroyed homes, businesses, schools, and hospitals. Additionally, oil tanks located at multiple refineries lifted from their mooring and leaked into the river (Dermansky, 2020). Even now, Lake Charles residents still feel let down and forgotten by their government and disaster agencies. Lake Charles Mayor Nic Hunter called it “a humanitarian crisis right here on American soil” (Smith, M., 2022).

As Eliseo Santana, a resident of St. Petersburg, Florida, stated, “[Y]ou have to be aware that these individuals [residents of marginalized communities] have been traumatized and have not had a chance, [sighing] and it just keeps building up. So, just be aware of that [when we talk about managed retreat].”10 Hence, communities already dealing with pre-existing and long-term environmental conditions need more robust support mechanisms to cope with and adapt to climate stresses, including potential displacement or relocation.

___________________

10 Comments made to the committee on July 12, 2022, during the committee-hosted public workshop. More information is available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/07-12-2022/managed-retreat-in-the-us-gulf-coast-region-workshop-2

Forms of Mental Health Impacts from Climate Change and Climate-Induced Relocation

Episodic and Chronic Climate Harms

Although well-being is not yet centered in pre-disaster planning and post-disaster recovery, episodic and chronic climate-related harms are well understood (Clayton et al., 2021; Crimmins et al., 2016; Reidmiller et al., 2018). Disruption caused by episodic adverse weather events (e.g., individual storms, heat waves, and flood events) can cause acute impacts (e.g., anxiety, depression, stress; Cruz et al., 2020) and multiply levels of depression, anxiety, trauma, suicide, and substance use in the affected communities (see Box 6-2). There are similar marked escalations in mental health burdens from continued climate disruptions (e.g., drought, ongoing elevated heat and flooding, and displacement and migration), especially as they compound already-existing economic and agricultural precarity and property loss or damage (Clayton et al., 2021).

Anticipated Climate Harms: Eco-anxiety and Solastalgia

Mental health effects also result from the anticipation of future events. These may be less obvious than the ones listed above but still profoundly impact communities. For example, while nostalgia stems from a separation

BOX 6-2

Community Testimonial: Displacement and Mental Health Concerns

“I think even before the storm that […] a lot of folks in our bayou areas were already going through mental health issues because of land loss issues. And I find in our community, and, losing our land and our homes and places where we grew up is like losing a family member. We’re suffering with grief, and we don’t actually understand, you know, what it is. But that’s kind of—we’re losing a part of ourselves, you know, as we’re losing our home and our communities. And it takes a toll on us […] So, when these events happen, you know, and Mother Nature, you know, she just has a way of kicking us when we’re down sometimes. You know, it takes a toll, and then it’s one thing on top of the other. And then the depression, and then being out of work, and then, you know. You find other ways to, you know, to fill those voids and all that. The mental health issue is very strong, very under-treated in Houma, in Louisiana as a whole.”

SOURCE: Bette Billiot, the United Houma Nation. Workshop 3: Assisted Resettlement and Receiving Communities in Louisiana, July 2022, Houma, Louisiana.

from and longing for home, solastalgia arises while people are still physically at home, but environmental change causes distress due to an inability to draw “solace,” or comfort, from one’s home environment or landscape (Albrecht et al., 2007). Solastalgia starts with the recognition of environmental deconstruction or risk, which can bring a sense of impending change or displacement (Simms et al., 2021). It is accompanied by the erosion of a sense of place, a loss community resources, and feelings of powerlessness (Albrecht et al., 2007).

Eco-anxiety is common and psychometrically consequential in terms of interfering with daily function; it may in some ways be distinct from the experience of other common anxiety or depressive disorders (Hogg et al., 2021). Similarly, ecological grief, or various forms of experienced loss or threatened/anticipated loss of place, have been described (Cunsolo et al., 2020). Youth are especially vulnerable to direct traumatic effects of climate-related events. In terms of distress from anticipated consequences, survey data suggest that such distress is markedly common and impairing among youth globally and reflects an erosion of social trust and experienced intergenerational betrayal (Hickman et al., 2021).

Climate and Stress

Allostasis is the body’s response to internal and external conditions or stressors to maintain physiological equilibrium (McEwen, 1998). In public health, allostatic load describes the cumulative physiological consequences of chronic exposure to fluctuating or heightened neural or neuroendocrine response, which results from repeated or prolonged chronic stress over the life course. Chronic allostatic load is an important variable in individual mental and physical health and well-being (Sandifer et al., 2017). People in communities that repeatedly receive displaced newcomers may experience an increase in allostatic load, for example, when community assets, such as housing, jobs, and schools, are already scarce or underfunded. Individuals who live in economically and socially marginalized conditions typically face greater exposure to social and economic stressors (e.g., discrimination; low wages; lack of access to affordable food, housing, child care, and health care; Henderson, 2022; Hernández & Swope, 2019; Taylor & Turner, 2002), and experience higher levels of allostatic load and deteriorated physical health (Geronimus et al., 2006; Thomas Tobin et al., 2019; Thomas Tobin & Hargrove, 2022). Chronic stress associated with past, present, and anticipated adverse climate events is a causal factor in several diseases via the disruption of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis relationships and other mechanisms that in turn can lead to premature mortality over many years (e.g., via increasing hypertension [cardiovascular disease and chronic renal disease]; Cohen et al., 2007; Ghosh et al., 2022).

Cumulative Climate Harms

The implications of cumulative psychological morbidity for public health are substantial in terms of premature mortality, suffering, and impairment (Case & Deaton, 2021; Compton & Shim, 2015; United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2021). But they are also substantial in terms of social costs—damage to a myriad of social outcomes—in the areas of sustained employment, education success, family and parenting stresses, as well as the social cohesion and collective efficacy that enable shared action and problem solving. These social costs are beginning to receive more attention, such as in the latest UNDP human development report, which found that “mental well-being is under assault” globally and connected this to the impairment of a wide range of psychological and emotional capabilities that collectively from humanity’s ability to meet the demands of “shaping our future” in a world that climate change is transforming (UNDP, 2022, p. 13). The UNDP report traces in detail connections between individual, communal, and societal well-being. This acknowledgment of psychological resilience as a resource is echoed in a body of research relating mental health and emotional well-being with social capital (Almedom, 2005; De Silva et al., 2005), and being recognized as a needed component of global efforts in scaling climate adaptation.11

Policy Implications

The broader policy implications of climate-induced impacts are important to a region like the Gulf, where health and well-being are severely stressed by inequitable exposures to climate-related risks and public health and health care investment is relatively low (see Box 6-3).

ENHANCING RESILIENCE AND WELL-BEING THROUGH TASK SHARING AND NURTURE EFFECTS

This section examines practices that can promote individual and community well-being in a changing climate and during climate-induced relocation decision making. Psychological resources and emotional well-being are social determinants of public and individual health that need specific attention. In addition to arguments for increasing access to care to address symptomatic distress or illness, there exists a growing body of knowledge around practices of “task sharing” and “nurture effects.” These practices

___________________

11 The COP27 Sharm-El-Sheikh Adaptation Agenda is one example of recent global efforts. More information is available at https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/SeS-Adaptation-Agenda_Complete-Report_COP27-.pdf. More information about COP27 is available at https://unfccc.int/cop27

BOX 6-3

Implications of Health Service Availability for Relocation and Displacement

- Nationally, only 10 states have not expanded Medicaid to cover all uninsured adults, and four of these states are in the Gulf region (Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Texas; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2023). People in the resultant “coverage gap” are non-elderly adults who are mostly working parents with Black or Hispanic race or ethnicity (Rudowitz et al., 2023).

- As has been presented in Chapter 2, several negative social and environmental determinants of health are concentrated in this region, including poverty, racial and other forms of historical discrimination, and certain sources of environmental and industrial pollution. These historical conditions continue to impact both physical and mental health in the region today.

- As of fiscal year 2019, per capita spending for public health services in Gulf states ranges from a low of $21/year/person in Florida and $22/year/person in Texas to a high of $30/year/person in Louisiana (Trust for America’s Health, 2021). Historical conditions have played a role in shaping decisions about health care and public health access and resources.

- Black, Latinx/Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native people in the United States face economic barriers to health access, with each U.S. Gulf Coast state in the bottom quartile for overall state health system performance for at least one non-White racial/ethnic group (Radley et al., 2021). Minority groups also face social and cultural barriers caused by the lack of a diverse and culturally competent workforce (Gomez & Bernet, 2019).

- Heath and public health systems are themselves vulnerable to climate-related emergencies. Moreover, the workforce has been repeatedly depleted by the cumulative impacts of multiple disasters as well as COVID-19 (e.g., fatigue and burnout; National Academies, 2019b).

- Relocation of communities, large numbers of uninsured individuals, and modest government budgets for public health care together have serious implications for health care provisioning and access in sending and receiving communities alike.

- Health inequity and environmental justice issues are inevitable consequences of the racial disparities in the context of severe shortages of care (Ndugga & Artiga, 2023).

can be deployed to promote mental health, build socioemotional strengths, and forge prosocial attachments that can help anchor mutually oriented and collectively effective groups and communities. The following sections describe these two practices and the ways in which they are essential to community-driven relocation efforts.

Task Sharing

Task sharing is “an arrangement in which generalists—nonspecialist health professionals, lay workers, affected individuals, or informal caregivers—receive training and appropriate supervision by mental health specialists and screen for or diagnose mental disorders and treat or monitor people affected by them” (Fulton et al., 2011; Kemp et al., 2019, p. 150). Task sharing is a growing set of innovative tools and methods that can improve a community’s capacity to improve individual and community well-being, including through community skill-sharing (Hoeft et al., 2018; Patel, 2012; Stevens et al., 2020). Bolstering mental health building blocks can also be advanced through macro-social policies that promote nurture effects, such as economic stability, education and health access, and early childhood opportunities. Those effects are also achievable through “ground game” methods for spreading hands-on skills that can be adopted by a range of community members; this also has the benefit of markedly expanding sheer capacity for care and treatment (McClure et al., 2022, pp. 22–23).

Task sharing mental health skills—which can carry a whole spectrum of purposes—is an innovation largely developed in the past 15 years in the Global South. This paradigm rests on current evidence that a wide range of skills—from direct acute care to prevention and mental health and resilience promotion—can be adopted by lay people, therefore allowing much wider, credible, and scaled access and scope that at the same time build upon and reinforce other common local and social practices that provide empathy and care (Atif et al., 2022; Chibanda et al., 2016; Kohrt et al., 2020; Patel et al., 2017; Shidhaye et al., 2017; Singla et al., 2017). It is a model that was adopted at substantial scale in New York City in the initiative Thrive NYC (Belkin & McCray, 2019; Stevens et al., 2020), and it was put to randomized study through a large effort of coalition building in Los Angeles, Community Partners in Care, where almost 100 community organizations began to offer depression counseling and screening skills as a way of closing care gaps in South Central Los Angeles and North Hollywood (Wells et al., 2013a,b).

To treat depression in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina, a task-sharing effort called REACH NOLA trained residents to help their neighbors by teaching them skills of psychological counseling and ongoing monitoring (per the widely used Collaborative Care Model)‚ which

are usually performed by clinical social workers or nurses (Bentham et al., 2011; Springgate et al., 2011).12 This effort started as a collaboration between “local health and social service agencies” and academic partners at Tulane University, RAND Corporation, and the University of California, Los Angeles (REACH NOLA, n.d.). The effort mobilized lay community members to help with neighborhood recovery efforts and serve as the front line for a mental health system that was literally implemented in neighborhoods and homes of community members and tackled climate impacts and compounding adversities. The larger health system served as a supportive ally and backup. REACH NOLA subsequently evolved as a foundation of community member health roles throughout Louisiana and a community-partnered Louisiana State University research center on community resilience, Community Resilience Learning Collaborative and Research Network (C-LEARN).13

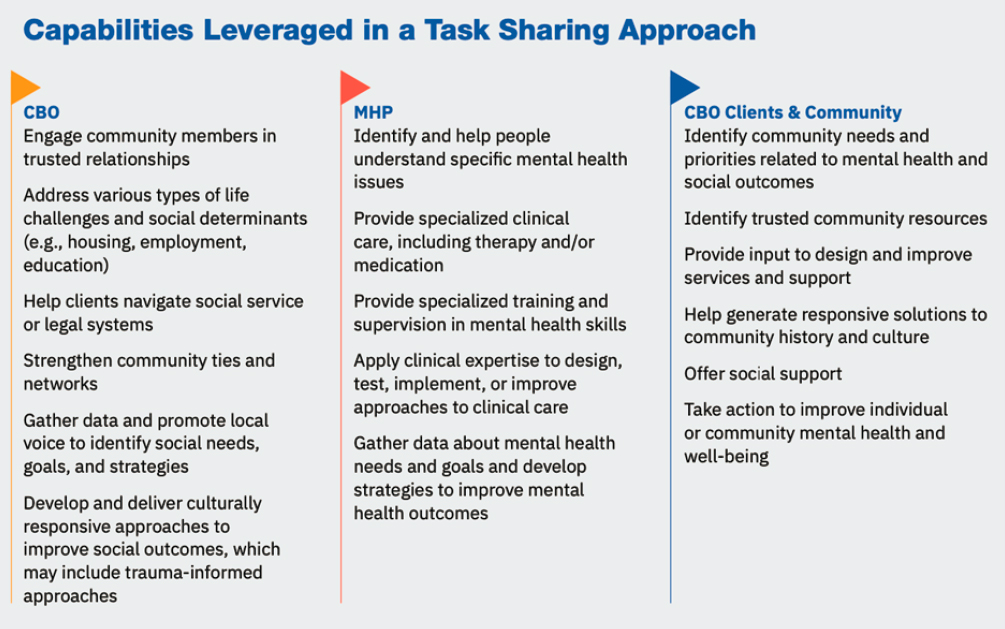

Ultimately, task sharing is about drawing on the current capabilities of different groups, such as community-based organizations (CBOs), mental health practitioners (MHPs), and lay community leaders and CBO clients, but also committing to building new capacities through collaborations and the co-implementation of well-being services (Farr et al., 2020; Stevens et al., 2020). Figure 6-3 shows the capabilities that CBOs, MHPs, and CBO clients and community members can leverage in mental health task sharing.

Adding to this approach is recent proliferation of lay support groups generated through climate activism networks. These groups often draw upon a range of psychological and eco-psychological practices, as well as Indigenous cultural and knowledge, and relevant local knowledges and practices. These groups are lay-led, and they craft responses to the psychological and social challenges of facing environmental loss and the need to generate growth, hope, and motivation in the face of daunting climate realities. Examples of many such efforts of self-formed support groups spread globally include the Good Grief Network in the United States, the Resilience Project in the United Kingdom, and SustyVibes in Nigeria.14

Nurture Effects

The concept of “nurture effects” also captures a wide array of well-evidenced psychological capabilities, such as mutuality, pro-sociality, psychological flexibility, empathy, affective security, and caring dispositions

___________________

12 More information about the Collaborative Care Model is available at https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care

13 More information about C-LEARN is available at https://www.c-learn.org/

14 More information about the Resilience Project is available at goodgriefnetwork.org/theresilienceproject.org.uk/sustyvibes.org. More information about SustyVibes is available at https://sustyvibes.org/

SOURCE: Stevens, C., Tosatti, E., Ayer, L., Barnes-Proby, D., Belkin, G., Lieff, S., & Martineau, M. (2020). Helpers in plain sight: A guide to implementing mental health task sharing in community-based organizations. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TL317.html

and attachments (Mayseless, 2020). These capabilities are cornerstones for emotional well-being, mental illness prevention, and mental health promotion at scale (Biglan et al., 2020). They also serve as social connective tissue for what psychotherapist Sally Weintrobe described as stacking the deck in favor of dispositions across institutions and modes of daily life toward care rather than uncare (Weintrobe, 2021). In this view, foregrounding nurture strategies in community strengthening policies mutually reinforces motivation around climate adaptation and eco-sustainable action. In the context of climate change and at the front end of adaptation to it, the continuity and strength of communities in the work of adaptation markedly widens what mental health-oriented policy can include.

Thus far, this chapter has discussed well-being frameworks in the context of climate change and climate-induced displacement and relocation, the well-being impacts of such changes, and practices that promote and enhance well-being in this challenging context. A principal objective of enhancing well-being for communities faced with displacement is to bolster their capacity to effectively and equitably participate in a community-driven relocation process. Critical to a community-driven approach is the recognition of the value of social capital, community cohesion, and collective efficacy, the subject of the next section.

SOCIAL CAPITAL, COMMUNITY COHESION, AND COLLECTIVE EFFICACY

“Social capital” refers to “features of social organization, such as networks, norms, and trust, that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit” (Putnam, 1993b, p. 2). These features of social life can have benefits for a community and its residents (Coleman, 1998). At the community level, social capital can be represented by social connections formed between and among a community’s members (Putnam, 1993a, 1995). These social connections and resultant networks are the foundation upon which trusting relationships and solidarity among community members, or social cohesion, are nurtured. As the social cohesion of a community is strengthened, the likelihood that community members willingly intervene or act on behalf of each other, or informal social control, becomes more favorable (Cagney et al., 2016). Strong social cohesion and favorable informal social control work together to cultivate the community’s perception of its capacity to achieve common goals that will improve the lives of its members, thus shaping a community’s collective efficacy (Cagney et al., 2016). Mutual trust and expectations around action in service of collective goals are central elements to achieving collective efficacy (Browning & Cagney, 2002; Cagney et al., 2016). By extension, scholars suggest that these same elements are central to community resilience (Sherrieb et al., 2010).

All Resources Matter

A focus on social resources (e.g., social capital, social cohesion) does not suggest ignoring the significant influence of economic, structural, medical, housing, transportation, employment, and other material resources in shaping the health and well-being of communities and residents. Furthermore, emphasis on community cohesion is not a promotion of residential segregation or other projects generating or maintaining racialized socioeconomic homogeneity (Kalra & Kapoor, 2009). Scholars caution that an emphasis on social capital and community cohesion can distract attention away from the forces that generate material inequities by uncritically promoting assimilation (Lin, 2000). For instance, if we assume social capital requires homogeneity to create community cohesion, we implicitly assert that ethnoracial diversity threatens or otherwise undermines the formation of social cohesion and, ultimately, community well-being. This framing centers ethnoracial diversity (or homogeneity) as the force deterring (or promoting) well-being. Scholars have aptly characterized this approach as a diversion from addressing material deprivation and social marginalization (e.g., Kundnani, 2007; Letki, 2008). This approach enables “policy-makers seeking less costly, non-economic solutions to social problems” to place the burden on disadvantaged groups and communities to form social relations as pathways to better social and economic outcomes (Portes, 1998, p. 3, as cited in Kalra & Kapoor, 2009).

Research examining environmentally induced relocation emphasizes the varied significance of material resources for the well-being of people post-move (de Sherbinin et al., 2022). For example, residents of flood-prone communities in Iquitos, Peru, who relocated to environmentally safer areas ultimately moved back to their original community because of a lack of economic opportunities at the relocation site, despite the risk of another flood. At the same time, some parents who relocated to environmentally safer communities willingly accepted less favorable economic opportunities in their relocation site in order to provide a cleaner and safer place for their children (Wirz et al., 2022).

Research has also emphasized how the uneven distribution of material resources shapes options for relocation (whether collectively or individually pursued) with significant implications for future material well-being (de Sherbinin et al., 2022). Analyses of home buyouts in Harris County, Texas, revealed that the most probable pathway for homeowners in less economically advantaged neighborhoods was individual household relocation (Elliott et al., 2021). Significantly, individual household relocation is the most potentially disruptive pathway because it separates community members from one another and uproots individuals from their home community. As elaborated and emphasized throughout this chapter, these social

and spatial fissures have significant impacts on individual health and overall community well-being.

PLACE ATTACHMENT, RELOCATION, AND WELL-BEING

The concept of place attachment, along with the broader notion of sense of place, was introduced in Chapter 5 and is elaborated here in the specific context of relocation, health, and well-being. The loss of place attachment is one of the most impactful contributors to poor mental health for the displaced (Adger et al., 2018; Burley et al., 2007; Vos et al., 2021). Place attachment informs the process of environment-related migration by constraining people’s decisions to leave; prompting decisions to leave when loss becomes intolerable; informing destination choice; and shaping the post-migration experience, including loss, grief, and the (in)ability to form new place attachments (Dandy et al., 2019). In this committee’s workshops, participants expressed strong attachments to place and the interrelationship between place and individual identities, as described by a workshop participant in Box 6-4.

Participants in this committee’s workshops expressed the interrelationship between place, livelihoods, and individual identities. People make a life through the material and social resources provided by livelihoods (Allison & Ellis, 2001; de Haan & Zoomers, 2005; Rakodi & Lloyd-Jones, 2002). Natural resource-based livelihoods generate place attachments informed through direct social-environmental interactions. Within the U.S. Gulf Coast, for example, fishing and oil industries have shaped Cajun ethnic identity (Henry & Bankston, 2002). In the case of fishing, emplaced

BOX 6-4

Community Testimonial: Bette Billiot, the United Houma Nation

“We know what the 1830s did to our people, the Houma. Communities and places change through time. Community will continue to thrive when culture is passed down but there have been and still are structural barriers. Our fishermen cannot pass this down to the next generation. We are embedded in the land and the water, family, culture, language, customs, and rituals. Our elders want to stay in place—but what is lost if this happens? We are this place. Living here means knowing how to live. If you want to live here, you have to know how to tarp your roof [after wind damage].”

SOURCE: Bette Billiot, the United Houma Nation. Workshop 3: Assisted Resettlement and Receiving Communities in Louisiana, July 2022, Houma, Louisiana.

economic ties to natural resources link to cultural ways of life, including the significance of local food (e.g., see Box 6-4; Lambert et al., 2021; see also Nelson et al., 2020).

Environmental change alters the social elements of place, which can include material and symbolic elements of place (Stedman & Ingalls, 2014). For example, among Vietnamese American residents in the New Orleans East community, place was understood to be a “homeland” holding significant cultural resources that in the absence of material resources often took on even greater importance for individuals making decisions about managed retreat (Chamlee-Wright & Storr, 2009). Research engaging Indigenous concepts of “country” approach connections to place in terms of a living system to which people belong and are related, and not in terms of resources provided to people by the environment (Dandy et al., 2019). Within this conceptualization, features of place and entities are family, and “country” is “love of place” (Wooltorton et al., 2017, p. 58; see also Cunsolo et al., 2012).

The implications of place attachment for relocation are multiple. As a place begins to change, residents might feel stronger place attachments (Burley et al., 2007; LeMenager, 2014; Low & Altman, 1992). Intensified place attachment can generate stronger commitments to staying in place and greater resistance to migrating (Barcus & Brunn, 2010). In fact, some conceptualize place attachment as a desire to stay in place (e.g., Hay, 1998). In the U.S. Gulf Coast, a region with a long history of hurricane exposure and responses to hurricane damage, some people become increasingly tied to place over time as rebuilding efforts recommit people to place (see Simms, 2017). Research on Louisiana coastal communities found residents’ resistance to relocating largely related to strong place attachments (Simms, 2017; see also Burley et al., 2007; Manning-Broome et al., 2015).

Place Attachment, Relocation, and Social Capital

While not all forms of social capital are spatially bounded (Barrios, 2014), place is one domain that fosters social relationships, social networks, and, ultimately, social capital. Places give rise to individual identities (Massey, 1994) and support site-specific beliefs, emotions, stories, and experiences (Lambert et al., 2021); for example, Convery et al. (2014) described the place of schools and their role in communities during disaster recovery, acting as structures where human experiences and the material world intersect and interact with one another (Casey, 1997). Place shapes people’s lived experiences, including their “environmental conceptualizations, rootedness to place,” and sense of belonging (Seamon, 2015; Simms et al., 2021, p. 317). Consequently, people changing places through, for

example, an environmentally motivated migration are uprooted from these critical aspects of their lives (Askland & Bunn, 2018; Jenkins, 2016; Oliver-Smith, 2009).

Place attachment closely relates to social capital (Stedman, 2003) and contributes to community resilience (Berkes & Ross, 2013). Research demonstrates that place attachment and social capital can increase capacity to adapt to environmental change and create barriers to change, including resistance to migration (Marshall et al., 2012), by promoting a reluctance to leave family, familiar surroundings, and ways of life (Fresque-Baxter & Armitage, 2012)—especially among people who have lived in a particular place for a long time (Anton & Lawrence, 2014).

Moving to a new community inherently disrupts place-based social capital, which can directly undermine an individual’s well-being as well as the origin community’s well-being (McMichael et al., 2010). Whether households move as a group to a single new location or move independently to multiple new locations, the move itself affects the integrity of social capital and, consequently, sense of belonging (Albert et al., 2018). Moreover, the site-specific meaning and value of social and social-material relationships people develop in their origin community are inadequately captured or replicated in resettlement (Morrissey & Oliver-Smith, 2013; Wrathall, 2015). Maintaining ties to property in origin communities, including ancestral lands, through continued access and ownership affects the likelihood of relocating and reestablishing social capital in new places, and thus enhances the social and mental well-being of people resettling to new communities (Simms et al., 2021). This sentiment was exemplified by workshop participants who explained that “progressives” leave Houma and move to Smith Ridge but have started to restore relationships and culture through large community “reunions that re-connect people to place and to each other” (see Box 6-5).

Place Attachment and Destination

Among those who migrate, place attachment informs the choice of destination and shapes the post-migration experience (Dandy et al., 2019). In terms of destination choice, people with strong place attachments might seek places with similar and, thus, recognizable biophysical, social, and cultural characteristics. This might implicate short-distance moves within the region or even more long-distance moves to places that approximate the characteristics of the origin community. Preference for receiving communities similar to home, however, can lead people to relocate to similarly if not more environmentally vulnerable areas (Glorioso & Moss, 2007), thus unintentionally increasing people’s vulnerability to environmental hazards (Anton & Lawrence, 2014; Moskwa et al., 2018; Niven & Bardsley, 2013).

BOX 6-5

Cherry Wilmore, and Sherry Wilmore, Residents of Houma, Louisiana

Cherry and Sherry Wilmore are twin sisters and residents of Houma.

“We’re migrants. We migrated here as foster children.” Houma was a foster care placement.

In 1991, when the twins were six years old, they entered foster care for the first time. They were placed in a group home for a few days before moving to their first foster home, located on a farm. It was there that they developed their love of knowledge, which they attribute to days spent watching Jeopardy with their neighbor. In addition, their foster mother taught them how to read using canned goods in the cabinet. Around age 10, Cherry and Sherry left that home and returned to their former group home for a month. Afterward, they were transferred to the MacDonell Children’s Home in Houma.

For the first time in their lives, the twins would find themselves separated from one another. “We have been together since conception.” The children were separated to make them more “adoptable.” Cherry was sent to a foster home, leaving Sherry behind at the group home. Cherry was determined to be reunited with her sister and resisted the system of child protection services.

She fought and “acted up” in the new place, she says, “so they would send me back with my sister [...] and we were united on our 11th birthday.”

Since European contact, the community has always been multi-ethnic, with people claiming Spanish, French, African, Cajun (Arcadian), Isleño, Filipino, and Asian roots. “Progressives” leave Houma and move to Smith Ridge but have started to restore relationships and culture through large community “reunions that reconnect people to place and to each other.”

Sherry explained that the vernacular of place names and referring to bayou directions (i.e., up or down the bayou) is not how Black people refer to places. “We have to understand that when you talk about this area as being particularly Terrebonne or Lafourche, and you refer to [a] place like Chauvin, Black people are going to refer to Smith Ridge […] When you speak about Houma, you may speak about ‘up the bayous’ [… but] African Americans are going to ask you, ‘Are you from the Mechanicville area, are you from the Alley, are you from Deweyville, are you from Gibson?’ because that is how they represent themselves” (National Academies, 2023a, p. 35).

Structural obstacles to community restoration and wellness are institutionalized (property taxes and insurance) and procedural (state and federal disaster responses). Slow recovery destroys communities. After Hurricane Ida, communities

had no water, fuel, power, food, communication, schools, sanitation, or jobs for 60 days. “We are used to water. This was wind. Ida was in August, extremely hot. A year later, people are still living in those conditions. How can you take care of old people, sick people? How do you take care of children?”

SOURCES: Cherry Wilmore, and Sherry Wilmore, Residents of Houma, Louisiana. Workshop 3: Assisted Resettlement and Receiving Communities in Louisiana, July 2022, Houma, Louisiana.

Connections with place inform an individual’s identity, feelings of self-efficacy, and attitudes about the future (Adams, 2016). Disruptions to this social-environmental relationship can have negative health consequences (Brown & Perkins, 1992), including those associated with loss and grief (Cunsolo & Ellis, 2018). Similar disruptions to health equilibriums are experienced by people who remain in close and intimate living and working “cultural relationships with the natural environment,” especially in rural areas; this includes Indigenous peoples, farmers, oystermen, shrimpers, and fishermen (Cunsolo & Ellis, 2018, p. 275; see also Bukvic et al., 2022). The material and social character of place is changed not only by climate but also by the economic, commercial, and political deconstruction of lands, culture, and home; this can ultimately lead to psychological and emotional distress (Albrecht et al., 2007; Jacquet & Stedman, 2014; Sorice et al., 2023).

Place attachment, therefore, provides a foundation from which to consider the various cognitive-emotional factors influencing how people and communities engage in change processes, including relocation (Adger et al., 2009, 2013; Clayton et al., 2015). Differences in place attachment underlie disagreements among residents and nonresidents regarding measures aimed at altering, preserving, or restoring a particular built environment (Kianicka et al., 2006). Willingness to relocate can be slowed by a strong sense of place attachment as well as a lack of community consensus on whether and where to move, lack of job opportunities, and distrust of government (Dannenberg et al., 2019; Davenport & Robertson, 2016). As a result, failure to understand differences in meanings assigned to place by people, state actors, and nongovernmental organizations can create barriers in communication and generate conflict between parties (Masterson, 2016; Sorice et al., 2023). In contrast, processes that allow and engage multiple, diverse place meanings may generate more resilience and greater health (Adger et al., 2013; Stedman, 1999).

SUMMARY

In the Gulf region, individuals and communities faced with pressures to relocate have already experienced a range of traumas and stressors from other environmental “events” that impact well-being and deplete social capital. Concurrently, individuals and communities may lack the necessary support mechanisms to ensure well-being, a crucial prerequisite to access to and participation in the decision-making processes that lead to mitigation and adaptation. Acknowledging, addressing, and acting on individual and communal trauma are the first steps toward increasing well-being, social capital, community cohesion, and collective efficacy; re-establishing trust between all stakeholders; and guaranteeing opportunities and resources for community agency at levels of decision making and policy in both short- and long-term goals.

CONCLUSIONS

Conclusion 6-1: There are discernable linkages between health disparities (e.g., premature death, elevated levels of chronic diseases, poor mental health, inequitable access to health care) and complex socioeconomic disparities (e.g., intergenerational poverty, economic precarity). Equitable and sustained community-driven relocation planning requires agencies (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Department of Housing and Urban Development) to examine these linkages within the context of originating and receiving communities.

Conclusion 6-2: The importance to communities of bolstering mental health and healing emotional distress lies not only in diminished suffering and enhanced coping but also in the social ties and associated social capital that mutually reinforce collective efficacy and social inclusion in processes of adaptation to social and environmental change.

Conclusion 6-3: Mental health is a critical aspect of community-driven relocation planning and demands greater breadth in scope and capacity, levels of support, resources, long-term commitment, and capabilities. Yet, mental health supports are inequitably distributed, further hindering historically marginalized communities from optimally coping, acting, and being empowered to make community-driven decisions. One way to address this situation is through the task-sharing paradigm, which intentionally leverages social capital and mutually reinforces community collective efficacy, shared action, and empowerment.

Conclusion 6-4: In the current context of decision making about relocation, the implementation of well-being frameworks can consist of adapting policies that incorporate and strengthen a community’s existing social capabilities (e.g., socioemotional bonding, trust, reciprocal engagement) and capacities for actions (e.g., social capital and cohesion, collective efficacy, shared sense of place).

Conclusion 6-5: One’s identity, well-being, and lifeways are tied to one’s sense of place. Place attachment critically informs decisions to relocate and can constrain decisions to leave; prompt decisions to leave when impending loss becomes intolerable; inform destination choices; and shape the post-migration experience, which includes loss, grief, and the long-term process of forming new place attachments. Place attachment is also related to social connections and social capital because shared place attachment facilitates collective identities, especially in contexts where subsistence and commercial-based activities are practiced in groups. A lack of understanding and valuation of place attachment can create tensions between residents, state actors, and economic and nongovernmental entities and organizations involved in relocation planning and implementation. A failure to recognize the importance of place attachment can undermine communities’ trust in relocation.

This page intentionally left blank.