The Next Decade of Discovery in Solar and Space Physics: Exploring and Safeguarding Humanity's Home in Space (2025)

Chapter: 1 Solar and Space Physics

1

Solar and Space Physics

The Space Age began a little more than 65 years ago and with it came the birth of a new science, space physics. However, the foundations of modern space physics harken back to 19th century studies of the aurora, sunspots on the Sun’s surface and atmosphere, and the discovery of the hot solar corona. Realizing the interconnected nature of these regions, a community began to coalesce and describe themselves as solar and space physicists. With the earliest spacecraft, the upper atmosphere (the ionosphere and thermosphere) was explored and this exploration was extended to what became known as the low Earth orbit environment, and then to Earth’s radiation belts and magnetosphere. This followed investigations from the 19th century applying the ideas of electromagnetism to Earth’s magnetic field, giving rise to the science of geomagnetism and its extensions into the upper atmosphere, and to the aurora, thereby laying the foundations for magnetospheric physics, the study of the solar wind and its interaction with Earth, and the subsequent development of space plasma physics.

The hunger for humanity to explore more challenging regions, farther from and closer to the Sun, introduced a broader description of the science that now embraced the entire heliosphere. Heliophysics comprises the study of physical process from deep in the solar interior, to the corona and solar wind; from the solar wind to its impact and influence on Earth, planetary, and minor bodies; and to its influence on the outmost reaches of the solar system as it collides with the interstellar medium. This encompasses an enormous region extending three times farther than the orbit of Pluto in the “upwind” direction (the direction in which the Sun and solar system moves through the Milky Way), and tens of thousands of times farther than Earth is from the Sun in the opposite direction. In the past decade, the field has expanded even beyond these boundaries. There are now spacecraft exploring and making measurements of fields and particles in interstellar space, the environment between the stars that surrounds the heliosphere, contributing in a novel and unique way to furthering the knowledge of the interstellar medium. The knowledge and expertise of the dynamical interplanetary medium and its impact on and interaction with planets, moons, and other solar system bodies is now being applied to the study of exoplanets. Not only is planetary exploration extending far beyond the solar system, but knowledge about the effects of the “weather” created by the Sun is being utilized to inform the “weather” experienced by exoplanets orbiting distant stars.

Thus, the constantly evolving and expanding science of solar and space physics is no longer bound by the heliosphere. The accomplishments are now fertilizing new fields that are well beyond these boundaries. This extension is driven by the knowledge and expertise in solar and space science.

1.1 SCIENCE HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE PAST DECADE

1.1.1 Introduction

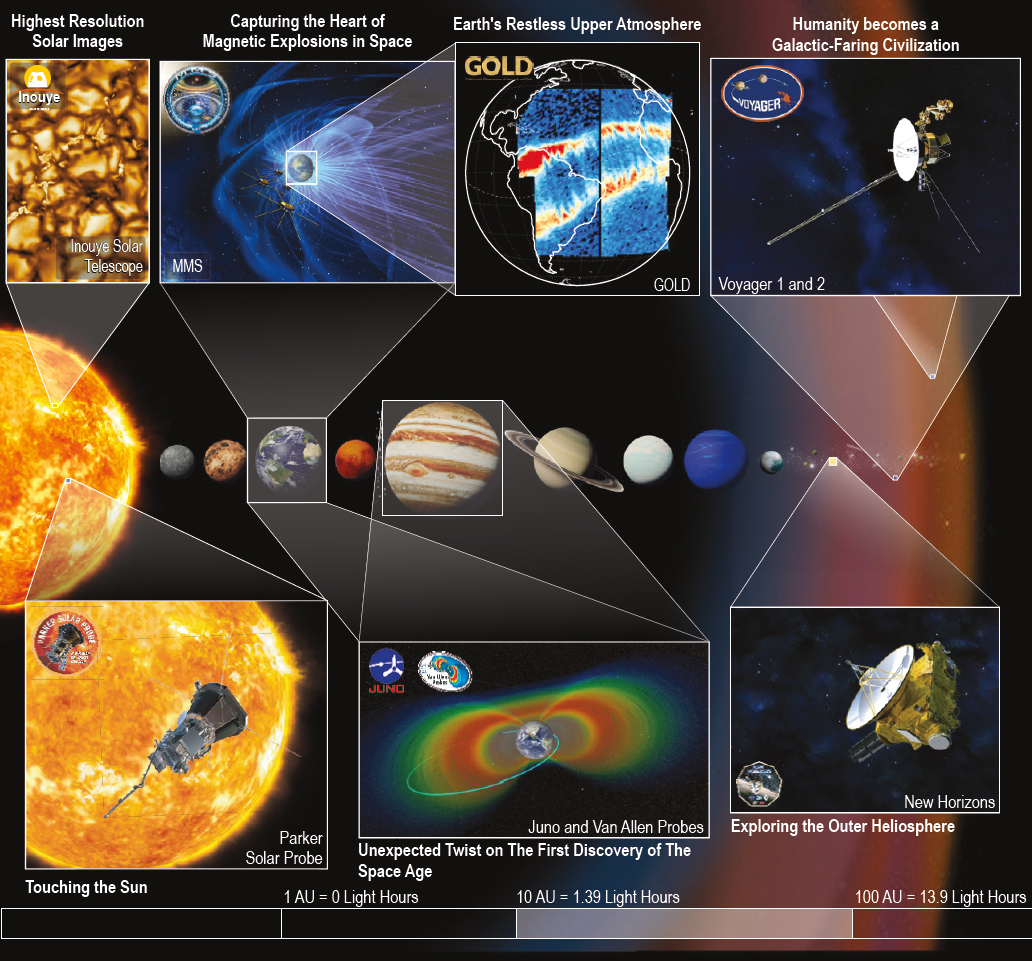

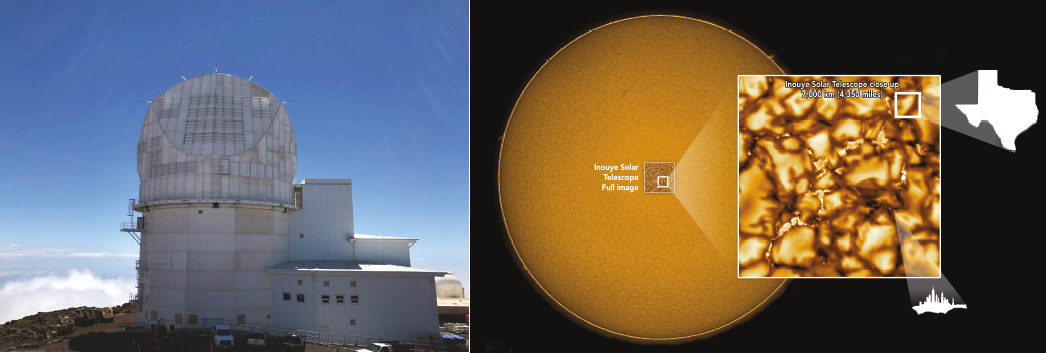

The past decade witnessed history-making explorations of the heliosphere as humanity touched the Sun and explored in situ the interstellar medium surrounding the protective bubble, the heliosphere, encompassing both the closest and farthest excursions from the Sun. Following studies of the Sun since the dawn of humanity with increasingly sophisticated observatories, the most capable and powerful solar observatory, the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope, experienced first light in 2019, promising to revolutionize ground-based solar physics. The epochal discoveries and the opportunities the space- and ground-based missions herald for the forthcoming decade fall under several themes outlined below.

Through exploration of our local cosmos, the discoveries, theories, and models have revealed that dynamical processes driven by the Sun and surrounding interstellar environment shape the habitability of the modern day Earth, its technologies, and peoples. Over the past decade, discoveries and efforts to project future changes in the space environment, now recognized as space weather, have helped safeguard the socioeconomic and security infrastructures. The increasing reliance on technology in the future will bring even greater challenges in safeguarding the habitability of Earth and the integrity of humanity’s technologies and human exploration.

A selected set of highlights from the past decade (Figure 1-1) are presented here. These highlights scarcely do justice to the full gamut of the remarkable and exciting discoveries and progress made by solar and space scientists over the past 10 years. However, these highlights were selected to exemplify the nature of the science and the directions the field is anticipated to take in the next decade.

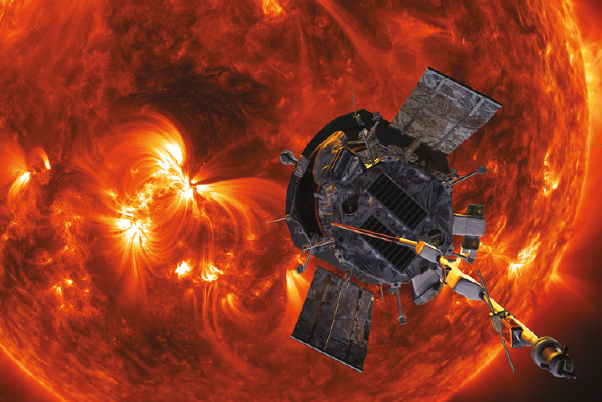

1.1.2 Touching the Sun

At 09:33 UT on April 28, 2021, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Parker Solar Probe (PSP) touched the atmosphere of the Sun, an extraordinarily hostile and entirely new, unexplored region of space (Figure 1-2). The solar atmosphere extending above the surface is bound to the Sun, unlike the supersonic solar wind that has escaped the Sun’s gravitational pull. The boundary of the solar atmosphere delineates the region where plasma signals (“Alfvén waves”) propagate back to the surface from the region outside that is completely detached from its solar origin. In crossing that boundary, PSP has become the first and only human-built spacecraft to touch the Sun. This stunning technological and scientific achievement helps provide the keys to unlocking the secrets of how the solar atmosphere is heated to million-degree temperatures, thousands of times higher than those measured at the surface. Moreover, the in situ measurement of the solar wind slowly separating from the atmosphere is one of the greatest heliospheric achievements ever made. A combination of in situ measurements made by PSP while enduring thousand-degree temperatures so close to the Sun and remote observations by the European Space Agency (ESA) Solar Orbiter mission revealed an extremely turbulent atmosphere, with fluctuations caused by the release of magnetic energy on small scales through a “magnetic reconnection” process. In the next decade, these observations position solar and space physics to answer the 70-year-old questions of how the solar corona is heated and how the solar wind is accelerated, as well as stimulate theoretical explanations and models for the role of turbulence in the heating and acceleration processes.

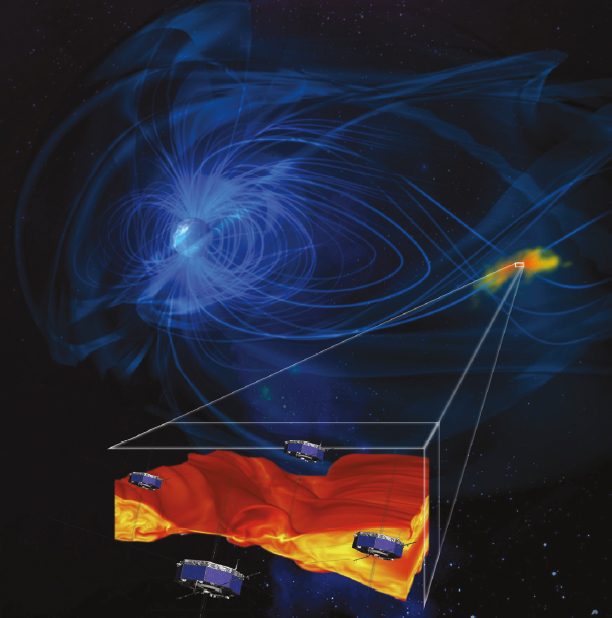

1.1.3 Capturing the Heart of Magnetic Explosions in Space

For less than 100 milliseconds on October 16, 2015, the four NASA Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) spacecraft flew through a magnetic reconnection event at the boundary where the Sun’s magnetic field pushed against Earth’s magnetic field (Figure 1-3). In this short instant of time, instruments on MMS captured, for the first time, the precise process that causes magnetic field lines to snap and reconnect in a new configuration, which results in magnetic explosions that catapult electrons to speeds up to hundreds of thousands of kilometers per second.

SOURCES: Composed by AJ Galaviz III, Southwest Research Institute; (background) Keck Institute for Space Studies/Chuck Carter; (Inouye Solar Telescope) NSO/NSF/AURA, https://nso.edu/telescopes/dkist/first-light-cropped-image. CC BY 4.0; (background simulation with MMS) NASA; (GOLD observations) Eastes et al. (2019), https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL084199. CC BY 4.0; (Juno and Van Allen Probes) NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/3951; (Voyager spacecraft) NASA/JPL; (New Horizons Spacecraft) NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/SwRI/Steve Gribben; (Parker Solar Probe) NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio and Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

SOURCE: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben.

Takeaways: The use of multiple spacecraft and multiple-instrument suites that combine remote and in situ observations holds the key to unlocking the secrets that the Sun and the heliosphere still hold. For example, the Parker Solar Probe mission (1) demonstrated the ability to explore unimaginably challenging environments and (2) enables combined multispacecraft in situ and remote observations (and soon ground-based observations with the Inouye Solar Telescope) to identify the small-scale magnetic-related phenomena that release the energy that may be responsible for heating the corona and driving the solar wind.

Magnetic reconnection is a universal process, driving energetic phenomena in extreme environments such as black holes, neutron stars, and the Sun and other stars. Closer to home, it is reconnection that allows solar wind to breach Earth’s magnetic shield, leading to violent space storms and high levels of energetic particle radiation. The MMS mission was designed to use Earth’s magnetosphere as a natural laboratory to perform definitive experiments on reconnection. The four spacecraft, each carrying 25 instruments capable of making measurements 100 times faster than previously possible, have yielded the first fully three-dimensional (3D) pictures showing how the highly dynamical magnetic fields suddenly break, and how the electrons and ions are accelerated in the process. The precision and speed of the MMS measurements is effectively a “microscope” in space that enables visualization of the highly localized processes. This discovery of the fundamental processes governing reconnection is a giant leap in the understanding of what triggers such magnetic explosions throughout the universe. The use of advanced theory and numerical simulations played a critical role in this discovery by predicting key signatures of the reconnection triggering process. Over the next decade (2024–2033), theory and modeling will continue to be an essential guide to the highly complex and turbulent reconnection environment. MMS observations have spurred major efforts to reconcile theory and observations by incorporating the very detailed physical processes of electrons and ions in large-scale simulations, which will motivate new theories for particle energization and acceleration via reconnection- and turbulence-related mechanisms well into the next decade.

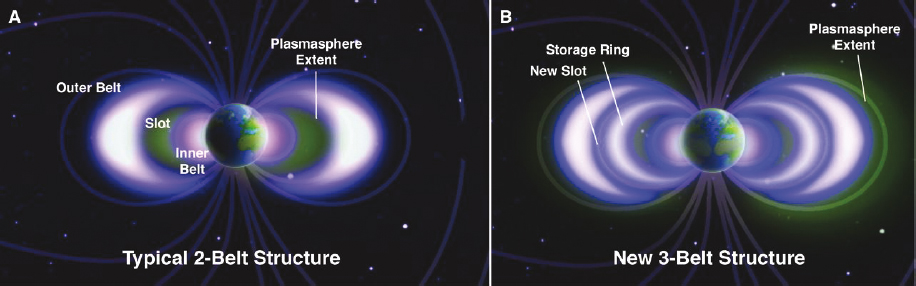

1.1.4 An Unexpected Twist on the First Discovery of the Space Age

With the launch of the NASA Van Allen Probes twin spacecraft mission into the radiation belts in late 2012, the expectation was that the mission would probe the dynamics of the two rings of high-energy particles circling Earth originally discovered by James Van Allen and the first U.S. space mission in 1958. Instead, and most unexpectedly, not two but three distinct rings were observed. This discovery underlines the exploratory nature

SOURCES: (spacecraft) Cudmore (2015); (background image) NASA Goddard’s Conceptual Image Lab.

Takeaways: (1) The past decade has demonstrated the importance of multispacecraft, multipoint measurements in identifying fundamental physics of multiscale spatial and temporal processes. (2) MMS provides a compelling rationale for multipoint measurements, effectively creating a laboratory in space, if transformative progress is to be made in understanding the building blocks of a highly coupled complex multiscale heliospheric system.

and state of space science today, with each new mission unraveling previously unknown physical processes and phenomena (Figure 1-4).

The radiation belts are highly dynamic, at times changing in shape and intensity within hours. Earth’s radiation belts typically comprise the inner belt closer to Earth, which is mainly composed of energetic protons, and the outer belt farther from Earth, which is dominated by high-energy “killer” electrons that are especially hazardous for spacecraft and their subsystems. In late 2012, the radiation belts were assaulted by an intense geomagnetic storm that created the third belt between the two preexisting ones. The third belt persisted for 4 weeks before a powerful interplanetary shock wave from the Sun annihilated it, returning the Van Allen belts to their standard two-belt configuration.

Besides profoundly affecting Earth’s radiation belts, space storms can dump large numbers of radiation belt particles into Earth’s upper atmosphere, thereby depleting the belts and destroying atmospheric ozone. Suborbital and CubeSat missions, such as the Colorado Student Space Weather Experiment (CSSWE), Balloon Array for Radiation-belt Relativistic Electron Losses (BARREL), and Focused Investigations of Relativistic Electron Burst

SOURCE: From D.N. Baker, S.G. Kanekal, V.C. Hoxie, et al., 2013, “A Long-Lived Relativistic Electron Storage Ring Embedded in Earth’s Outer Van Allen Belt,” Science 340(6129):186–190, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1233518. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

Takeaways: (1) The Van Allen belts are affected by solar storms and can grow dramatically, thereby disrupting communications and Global Positioning System satellites, as well as posing a danger to humans in space. (2) The 7-year-long Van Allen Probes mission has rewritten the radiation belt science textbooks, the third radiation belt being emblematic of the unexpected new insights returned by the mission into this fascinating region. (3) The Van Allen probes are another example of a laboratory in geospace. (4) International collaborations significantly increase a mission’s capabilities, whether by collaborating on the instrumentation suite (provision of instruments, addition of expertise, etc.) or even creating synergies between independent missions, such as occurred between the Japanese Arase mission (formerly known as Exploration of Energization and Radiation in Geospace) and Van Allen Probes to the considerable enrichment of both.

Intensity, Range, and Dynamics (FIREBIRD), provided complementary measurements of this atmospheric loss during the Van Allen Probes mission, illustrating that smaller missions can effectively and strategically augment major missions.

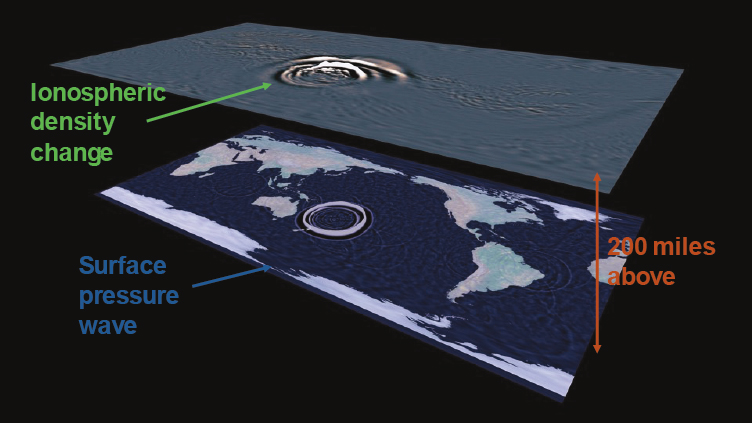

1.1.5 Volcanoes Reaching All the Way to Space

The Hunga-Tonga volcano eruption on January 15, 2022, was a once-in-lifetime event that provided a dramatic example of how the whole Earth, from subsurface to outer space, operates as one coupled system. The vast cloud of water vapor released from the submarine volcano created strong gravity waves in the atmosphere that propagated across the globe and all the way up to the upper atmosphere and its ionized portion, the ionosphere, essentially reaching outer space (Figure 1-5). Such waves create vertical coupling across atmospheric layers in ways that only the next decade with the upcoming Geospace Dynamics Constellation (GDC) mission will be able to resolve.

However, the substantial advances in developing models such as the Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model with thermosphere and ionosphere extension (WACCM-X) allowed, for the first time, a simulation of the entire atmosphere from the surface to low Earth orbit, including the physics of both the neutral atmosphere and the ionosphere. Worldwide observations of the waves provided a key validation of the model during some of the most extreme conditions ever observed. Such coupled simulations not only help reveal the nature of waves generated in the lower atmosphere but also address the longstanding conjecture of understanding the driving mechanisms behind quiet time bubbles/scintillations that pose a significant threat to radiofrequency communication and navigation systems.

SOURCE: ©2024 UCAR.

Takeaway: Advancements in physics-based models have enabled linking different regions of the atmosphere, treating it as one system from the surface of Earth to the edge of space.

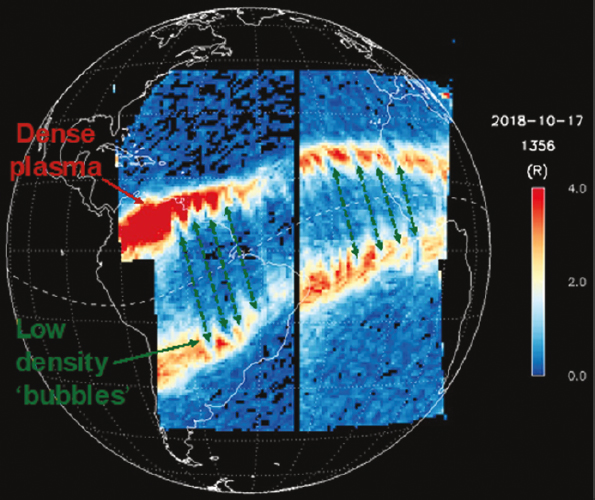

1.1.6 Earth’s Restless Upper Atmosphere

Far from being a stable quiescent region, Earth’s upper atmosphere is filled with plasma bubbles—stark voids in the charged plasma enveloping Earth—that are especially prominent in the evening hours after sunset. These seemingly harmless structures have proven to be space weather phenomena, as they impact Global Positioning System (GPS) signals traversing from spacecraft above, through the ionosphere, to ground receivers below. Utilizing its birds-eye view from geostationary orbit, NASA’s Global-Scale Observations of the Limb and Disk (GOLD) mission has provided a wealth of observations of Earth’s thermosphere and ionosphere (Figure 1-6). GOLD’s fixed position at geostationary orbit has offered a radically different viewpoint from that seen from low Earth orbit. Its continuous view of these bubbles has resolved ambiguities of their formation and motion. GOLD images combined with data from low Earth–orbiting spacecraft such as the Ionospheric Connection Explorer (ICON), Constellation Observing System for Meteorology, Ionosphere and Climate (COSMIC-2), and ESA’s Swarm spacecraft have given a valuable demonstration of the power of coordinated multipoint measurements that greatly exceed the value of any single mission alone.

1.1.7 Humanity Becomes a Galactic-Faring Civilization

This past decade witnessed humanity become a galactic-faring civilization. At a distance 120 times greater than that from the Sun to Earth and after 40 year’s journey, Voyager 1 and 2 exited the bubble created by the Sun—the heliosphere—to enter interstellar space and give humanity the first glimpse of interstellar plasma, magnetic fields, and unmodulated (i.e., unaffected by the heliosphere) low-energy galactic cosmic rays. This extraordinary event, a mere 65 years after humanity first ventured into interplanetary space, is a triumph of technology and scientific persistence. Virtually every measurement made by the aging instrumentation on board the 1970s vintage Voyager spacecraft represents a profound, and possibly one-of-a-kind, discovery that is unlikely to be replicated for several generations.

At the turn of the past decade, the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) probe remote sensing measurements discovered an unexpected “ribbon” of energetic neutral atoms (ENA) originating from the interstellar medium. Analysis of the ribbon and related ENA measurements allowed scientists to derive the strength and direction of the

SOURCE: Eastes et al. (2019), https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL084199. CC BY 4.0.

Takeaways: (1) Earth’s ionosphere–thermosphere–mesosphere system is a highly coupled mixture of neutral gas and charged plasma that surrounds Earth. This region responds strongly to external forces, both from drivers in the lower atmosphere and from the Sun and magnetosphere above. (2) Key scientific advances in the past decade have come from a combination of new observations that exploit new vantage points (such as GOLD) or combine data from multiple observatories.

very local interstellar magnetic field (Figure 1-7) and map the large-scale structure of the heliosphere. The analysis was made possible based on theory and modeling predictions made 25 years ago. The discoveries made by the Voyagers and IBEX spark questions about the fundamental structure of the large-scale heliosphere—its effect on and response to the very local interstellar medium. Ultimately, these measurements provide the key for how these processes contribute to creating a habitable environment for Earth. Combining these observations with theories and models provides knowledge about the interaction of distant stars with their interstellar environments and expands the understanding of habitability throughout the galaxy.

The understanding of very distant regions of the heliosphere and the interface to interstellar space is made possible by the ability to simultaneously use and coordinate remote and in situ measurements. This coordination has accelerated the understanding of the complexity of the coupled heliospheric–interstellar medium system, its underlying dominant physical processes, such as charge exchange, and the complex coupling of heliosphere to the local interstellar medium and vice versa in a way that could not have been anticipated a decade ago.

1.1.8 Heritage from the Dawn of Humanity: First Light from the Inouye Solar Telescope

Solar observatories date to the dawn of agriculture when humanity’s earliest farmers began charting the seasons. One of the earliest in the Americas, constructed between 250 and 200 BCE, is the 2,300-year-old archaeological site Chankillo in Peru. Other notable stone circle solar observatories include the 5,000-year-old Stonehenge in England, the 7,000-year-old Goseck Ring in Goseck, Germany, and the world’s oldest from more than 7,000 years ago in the Nabta Playa in Egypt.

SOURCE: Composed by AJ Galaviz III, Southwest Research Institute.

Takeaways: (1) The Voyager 1 and 2 interstellar mission epitomizes discovery science, exploring what was once regarded as an unreachable environment. Humankind is unlikely to replicate the Voyager discoveries for several generations without an agency/directorate-wide effort. (2) The simultaneous use and coordination of in situ and remote measurements of these most remote regions by Voyager 1 and 2, New Horizons, and IBEX (and soon IMAP) significantly advanced the field.

In 2019, the National Science Foundation (NSF) commissioned the most advanced solar observatory ever constructed, Inouye. This U.S.-led, NSF-funded, and National Solar Observatory (NSO)-operated telescope promises to revolutionize ground-based solar physics. Its five instruments, four of which are polarimeters, operate over a broad wavelength covering the visible, near-infrared, and mid-infrared spectrum. Thanks to its exceptional site on Haleakala, Hawai’i, a large 4 m aperture primary mirror (Figure 1-8), advanced adaptive optics integrated into the telescope, and numerous design innovations, Inouye can observe features as small as 20 km on the surface of the Sun—an unprecedented level of detail. This unprecedented high-resolution capability enabled the first direct images of locally excited acoustic waves in the solar chromosphere (Bahauddin et al. 2024). Moreover, the state-of-the-art magnetic field measurements of the Sun’s chromosphere and corona provided by Inouye will revolutionize our understanding of small-scale magnetic activity, plasma jets at the solar surface, the triggering of solar flares and eruptions, and long-term solar cycle variations of these small-scale structures.

In the next decade, Inouye will not only play a world-leading scientific role as one of the great observatories but will also be a critical element of space- and ground-based multiobservatory, multinational studies of the Sun.

SOURCES: (Left) NSO/NSF/AURA, https://nso.edu/telescopes/dkist/fact-sheets/dkist-overview. CC BY 4.0. (Right) NSO/NSF/AURA, https://nso.edu/telescopes/dkist/first-light-context-full-sun. CC BY 4.0.

Takeaways: (1) Ground-based observations are a vital cornerstone of solar physics, with capabilities unavailable to space-based observations. (2) Inouye was enabled by a broad partnership that included international partners. (3) Inouye will play a central role in multiobservatory studies of solar phenomena and is already making joint observations with the Parker Solar Probe.

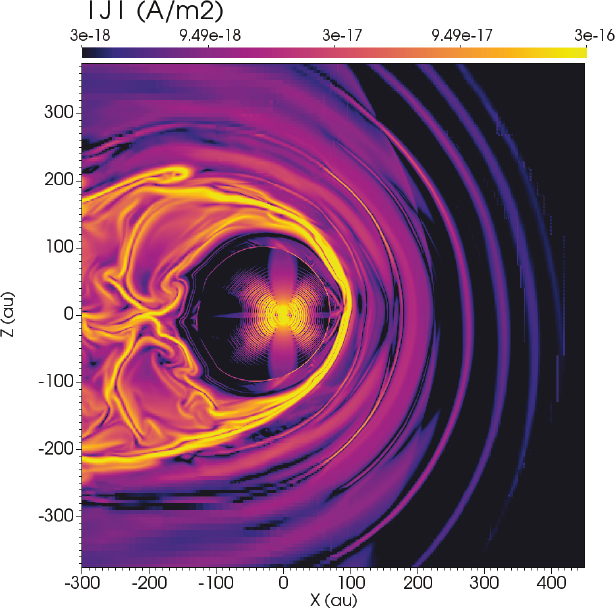

1.1.9 Making Sense of the Unimaginably Vast and Complex

How does one make sense of a region so vast that begins at the surface of the Sun and extends nearly 25 billion kilometers into the void of space? It takes some 22 hours and 35 minutes for radio waves sent from Earth, traveling at the speed of light, to reach Voyager 1. And yet shock waves driven from the Sun’s active surface are observed by Voyager 1 years later. Over such unimaginably vast distances, the complex physics that connects these disparate regions is only captured by the most advanced computer models using the largest supercomputers. As illustrated in Figure 1-9, models and theory capture the physics and the extraordinary complexity of the temporal 3D bubble, the heliosphere, in which humanity resides. Spacecraft provide snapshots of a miniscule region of space at different times and yet these sparse observations provide important input for model boundary conditions and model validation.

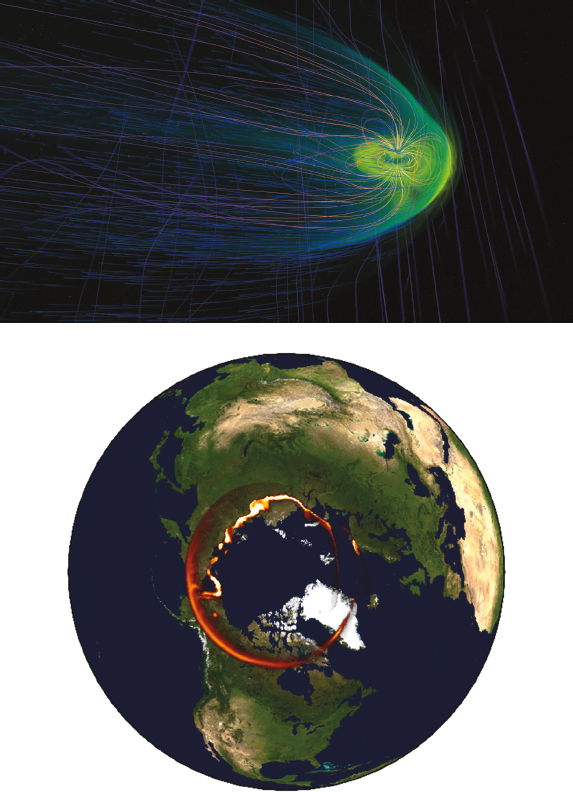

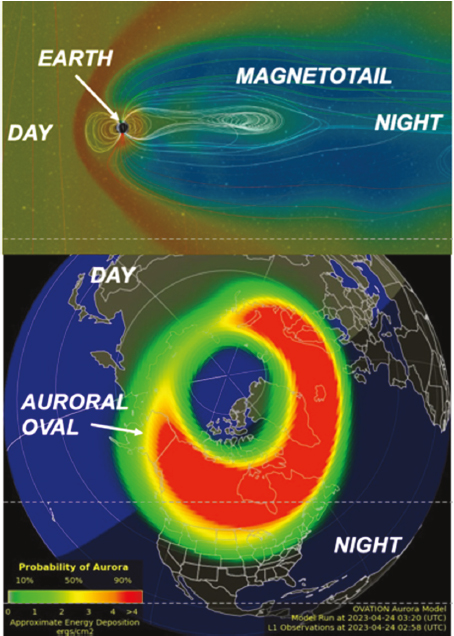

These models and theory also connect and couple the very large to the very small, as in Figure 1-10. The struggle to understand the global scale with highly localized spacecraft observations is also a struggle to connect large-scale phenomena, such as a magnificent auroral display, to the solar drivers and the microscopic kinetic processes responsible for creating the other-worldly shifting radiance of the northern lights. However, with tremendous progress in the past decade, theory and modeling—as illustrated in Figure 1-10—now couples shock waves and plasma eruptions at the Sun to a highly disturbed magnetosphere about Earth and the subsequent magnificence of a highly structured auroral display that encompasses the northern (and southern) latitudes.

This progress notwithstanding, theory and modeling promise so much more in the coming decade, moving toward the level of completeness and self-consistency in the models that will extract the full feedback and response to the inclusion of the full range of spatial, temporal, continuum, and kinetic scales. Modeling will provide both perception and understanding of the local cosmos, from which will emerge the capability of predictive operational models capable of serving the growing needs of humanity’s technological society.

SOURCE: F. Fraternale and N.V. Pogorelov, ISSI Team 23-574, “Shocks, Waves, Turbulence, and Suprathermal Electrons in the Very Local Interstellar Medium,” Presented at the AGU Fall Meeting 2023 (Poster SH51D-2652).

Global models of the large-scale heliosphere (Figure 1-9) and the geospace system (Figure 1-10) have seen tremendous growth in the past decade. These advances motivate new missions that would test model predictions via multipoint in situ measurements and remote sensing. Simultaneously, further progress requires taking models to a new level to harness both the ever-increasing physical complexity and the rapidly changing supercomputing landscape, while adhering to the standards of open science. This conclusion applies to physics-based models across the entire field of solar and space physics.

1.2 SPACE WEATHER IN THE SERVICE OF HUMANITY

1.2.1 Space Weather Impacts Us All

The past decade marks a period when developed societies became truly space faring, as humanity depends increasingly on space-based communication, positioning, and navigation assets and applications, and as astronauts and commercial space travelers venture deeper into space. In addition, ground-based infrastructure has become more complex, relying on sensitive electronic components susceptible to electromagnetic disturbances driven by space plasmas and fields. As utilization of space continues to increase, the need to protect against the hazards of the space environment through advances in scientific knowledge will continue to grow.

SOURCES: (Top) NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio; (Bottom) NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio; Blue Marble Next Generation data is courtesy of Reto Stockli (NASA/GSFC) and NASA’s Earth Observatory. The MAGE simulation aurora image by V.G. Merkin and K.A. Sorathia.

Takeaways for Figures 1-9 and 1-10: (1) Physics-based models have progressed enormously in the past decade. (2) Models now make predictions that defy the ability to test them with existing data. (3) Model development has become as complex as space missions or ground-based facilities. (4) A new level of investment is necessary to exploit the opportunities to make further leaps forward in physics-based modeling across solar and space physics.

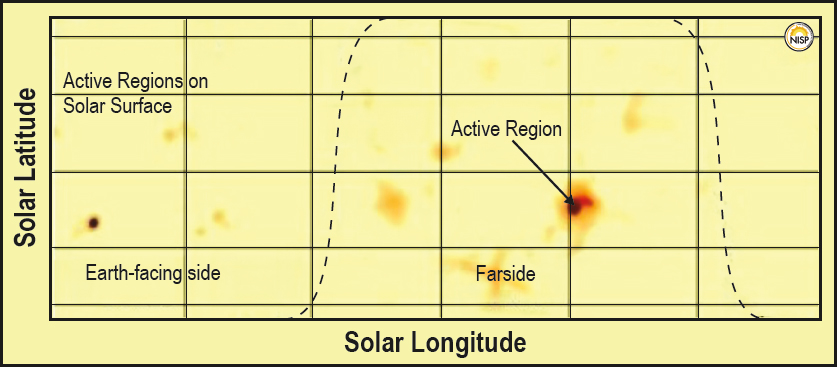

Space weather has become the applied branch of solar and space physics that addresses the adverse impacts of the Sun, its expanding atmosphere, and magnetic field on life and technologies at Earth, its atmosphere, space environment, and more generally everywhere in the solar system. Because the Sun is the primary origin of space weather, it behooves humanity to understand this star as it increasingly affects every aspect of technological society and lives. Figure 1-11 shows detection of active regions on the farside of the Sun using helioseismology. When combined with machine learning to predict the onset of flares from these active

SOURCES: Martinez-Pillet et al. (2020), https://baas.aas.org/pub/2020n3i110. CC BY 4.0.

Takeaways: (1) The Sun is the source of inclement space weather at Earth through a complex series of physical events and processes. (2) Inclement space weather is having an increasingly deleterious major financial and technological impact on space-based and ground-located assets, companies, industries, defense, and national interests. (3) Like Earth’s weather, forecasting and nowcasting is critical to managing responses to space weather.

regions, these predictive capabilities, when fully developed, will provide predictions ranging from hours to days in advance, helping to protect humans, technologies, and infrastructure in space (satellites and high-altitude aircraft) and on the ground.

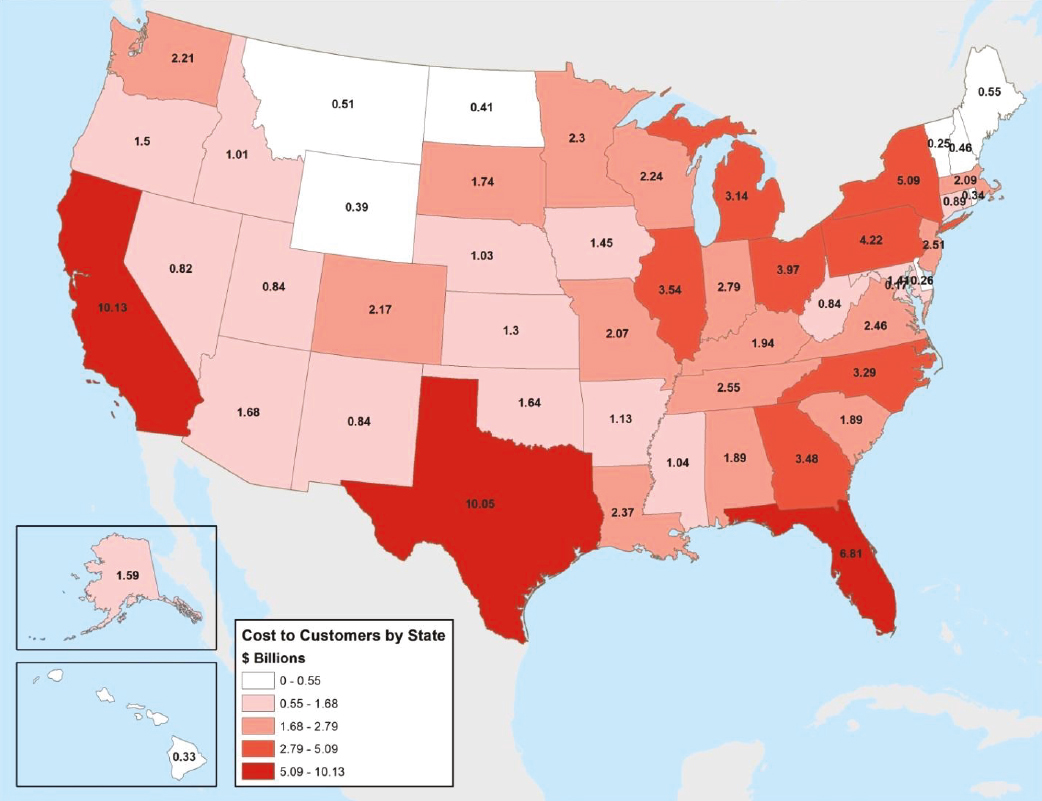

Space weather continually degrades space systems and causes errors in navigation, positioning, and communication systems. Severe space storms can debilitate entire power grids, generate hazardous radiation that harms aircraft and space-based crew, increase the risk of collision by nudging spacecraft and scrambling space debris orbits, and cause satellite subsystems to malfunction. The valuation of space weather risks is in excess of multiple billions of dollars (Figure 1-12) and has caught the attention of industrial, financial, defense, and commercial sectors and national and international legislative bodies.

While space weather observational needs are in part fulfilled by observations gathered from scientific missions, operational data are of great interest to the scientific community. Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES) data have been used by the scientific community for 50 years. The next decade will take this duality to new levels. Space research increasingly needs multiplatform measurements to resolve space processes at all relevant temporal and spatial scales. The densely populated low Earth orbit offers especially excellent opportunities for both space weather research and service development through the deployment of simple instruments onboard commercial spacecraft. The impending solar maximum, predicted to be much more active than the previous one—with its increased space traffic management challenges, radiation damage, and communication malfunction potential—demands timely attention.

1.2.2 Space Weather Comes of Age

A little more than a decade ago, space weather was the orphaned child of space science, likely to be important in the future but unsure of where its home lay. Today, the specific congressional mandate and the Promoting Research and Observations of Space Weather to Improve the Forecasting of Tomorrow Act (PROSWIFT 2020) codified the importance of space weather and assigned space weather roles to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

SOURCE: NOAA National Weather Service (2017).

Administration (NOAA), NASA, NSF, and other agencies. Initially space weather was the purview primarily of NOAA, augmenting its terrestrial weather capabilities and expertise, with NASA engagement beyond scientific research occurring on an ad hoc basis driven mainly by recommendations in the 2013 decadal survey, Solar and Space Physics: A Science for a Technological Society (NRC 2013; hereafter the “2013 decadal survey”). The 2013 decadal survey followed its statement of task, which focused on NASA and left a gray area between NASA and NOAA science and operations.

Space weather is a field that requires a solid scientific foundation, a national-level observing system, and a thorough understanding of the engineering solutions of the systems to be protected. To meet these demands, space weather solutions call for multidisciplinary, systems-level approaches. The National Space Weather Strategy and Action Plan (2019), the PROSWIFT Act, and the Space Weather Research-to-Operations and Operations-to-Research Framework (NSTC 2022) provide the requisite linking of science, national policy, and responsible parties. The legislation defined the respective roles and responsibilities of multiple agencies. For the first time, a framework for the modern era now exists for coordination of all sectors, from space weather researchers to forecasting operators and user groups, to address the protection of the nation’s most precious assets.

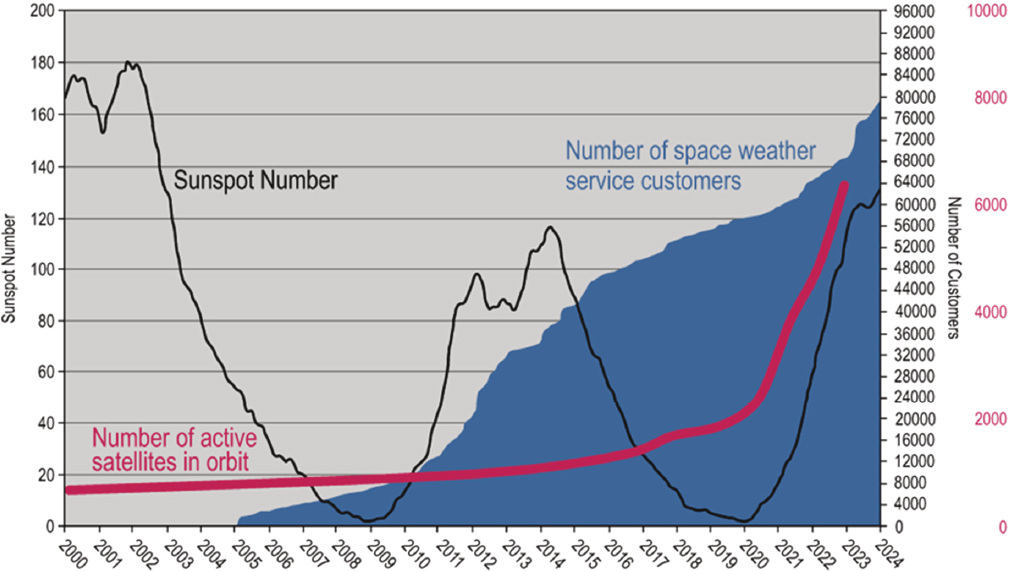

1.2.3 The Growing Customer Base

At a September 2019 roundtable discussion hosted by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the SmallSat Alliance, Ajit Pai, former Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, highlighted the importance of the space sector by stating, “Whether they know it or not, all companies will be space companies” (National Space Society 2019). Ajit Pai’s prediction will almost certainly be true by the end of the coming decade. Figure 1-13 shows that the customer subscriber base to the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) has grown exponentially since 2005 and today is approaching 80,000. Such a growth rate, if continued, predicts more than a million subscriptions by the end of the coming decade, making almost all companies “space companies.” The enormous growth of satellites in low Earth orbit (pink line in Figure 1-13) is another strong indication of the ever-increasing demands on space weather resources.

1.2.4 Modeling the Space Weather System

Space weather prediction has taken giant leaps forward in the past decade. The upcoming decade promises extraordinary progress as the scientific and operational observation network grows and the numerical simulation, data assimilation and data science techniques, artificial intelligence methods, and the computational capacity continue to increase. The recently established NASA “proving ground” and NOAA “testbed” efforts support testing,

SOURCES: Adapted from NWS/NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center (n.d.); Satellite data from J. McDowell (2024), https://planet4589.org. CC BY 4.0.

Takeaways: (1) There is a growing realization that space weather will impact all commercial sectors besides the obviously space-based technological, electrical grid, and spaceflight invested parties. (2) This is borne out by the exponentially growing number of subscribers to the NOAA SWPC subscription service. (3) A growing and broadening category of space weather services will be needed to meet the diverse needs of the commercial, industrial, federal, defense, research, and financial sectors.

SOURCES: (Top) NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio, the Space Weather Research Center (SWRC), the Community-Coordinated Modeling Center (CCMC) and the Space Weather Modeling Framework (SWMF). (Bottom) NOAA/SWPC.

Models predict the impact: Solar eruptions expel large plasma clouds, coronal mass ejections, into interplanetary space. These clouds engulf Earth’s space environment from about 15 hours to 2 days later, creating large geospace storms hazardous to both space- and ground-based systems and assets.

Takeaways: (1) The Sun has a major impact on the near space environment through the production of a dangerous damaging radiation environment. Coronal mass ejections can severely impact Earth’s protective magnetic shield, the magnetosphere, and ionosphere. A variable solar wind and solar magnetic field similarly affects the magnetosphere. (2) Significant advances in numerical methods and computational power now allow, for the first time, scientists to model the space environment. NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center runs such models to predict geomagnetic activity in space, in the upper atmosphere, and on the ground. (3) The Space Weather Modeling Framework Geospace model describing the entire near-Earth space system down to 100 km altitude was transitioned from research to operational use in 2016. The WAM-IPE model describing both the neutral and ionized upper atmosphere up to about 600 km in altitude was transitioned to operations in 2021. Both are major steps forward for space weather research to operations capabilities.

1.3 MISSION AND VISION: TRANSITIONING TO THE NEXT DECADE

What lessons have been learned from the past decade and do they illuminate the path into the next decade? From the highlights above, several key general lessons are extracted.

- Scientific breakthroughs often result from developing novel theories and models, instrumentation, and missions utilizing either or both in situ and/or remote imaging observations to explore new environments.

- Transformative discoveries can come from exploring apparently familiar regions using multiple homogeneously or heterogeneously distributed spacecraft or vantage points to make coordinated multispatial, multitemporal, multiscale measurements. Improved instrumentation on these distributed spacecraft resolves relevant spatial and temporal scales, thus effectively using the “elements” to discover a “systems” perspective.

- Theory, models, and observations that resolve the smallest (i.e., microscopes) or largest (i.e., telescopes) spatial and temporal scales answer long-standing fundamental questions, stimulate new theory and sophisticated simulations, emphasize that cross-scale coupling from micro- to meso- to macro-scales is critical to many unanswered problems, and elaborate the need for a systems-level understanding.

- Space weather has come of age, and solar and space physicists are learning that the entire Earth, from subsurface to outer space, operates as a single highly complex and integrated coupled system. This system offers both protection and hazards to humanity’s technological society.

These lessons, along with considerable community input, form the basis of the priority science in this report from the Committee for a Decadal Survey for Solar and Space Physics (Heliophysics) 2024–2033. The statement of task (see Appendix A) for this survey is broader than those of the previous two decadal surveys in solar and space physics. Notably, in addition to identifying priority science, the task included the following: assessing the space weather pipeline, from basic research to applications to operations, and identifying new and emerging frontiers where solar and space physics expertise enables significant advances. Guided by this statement of task and additional counsel contained in the study approach, recommendations made to the study sponsors—the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR), NASA, NOAA, and NSF—constitute an ambitious but realistic approach for realizing identified scientific and space weather advances.

The four lessons above that form the cornerstone of the priority science portend the rich vein of discoveries for the next decade, not just in the heliosphere but in our very local region of the universe—what space physicists call “our local cosmos.” A particularly promising research direction is the comparison of the Sun–Earth–heliosphere to other stellar systems. As humanity looks beyond the heliospheric boundaries to planets and astrospheres around distant stars, the ultimate question is whether life flourishes in these systems. Studying and understanding the only known habitable system in the universe, solar and space scientists are uniquely positioned to develop the theories and models that describe the stellar systems in the local cosmos, thereby defining the physical conditions that may enable life elsewhere in the galaxy. Contemporaneously, such knowledge is the cornerstone for protecting and safeguarding humanity and its technological society against the vicissitudes and dangers posed by inclement “space weather.”

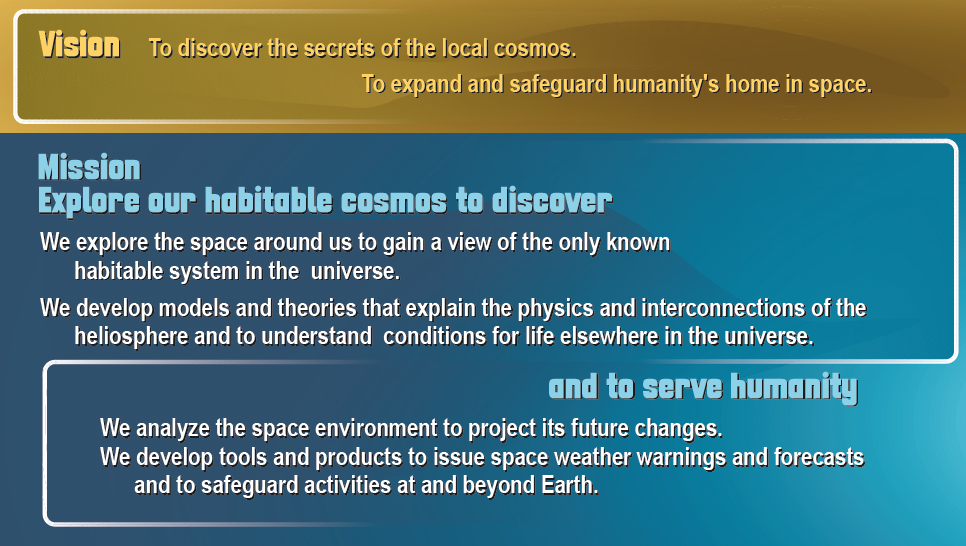

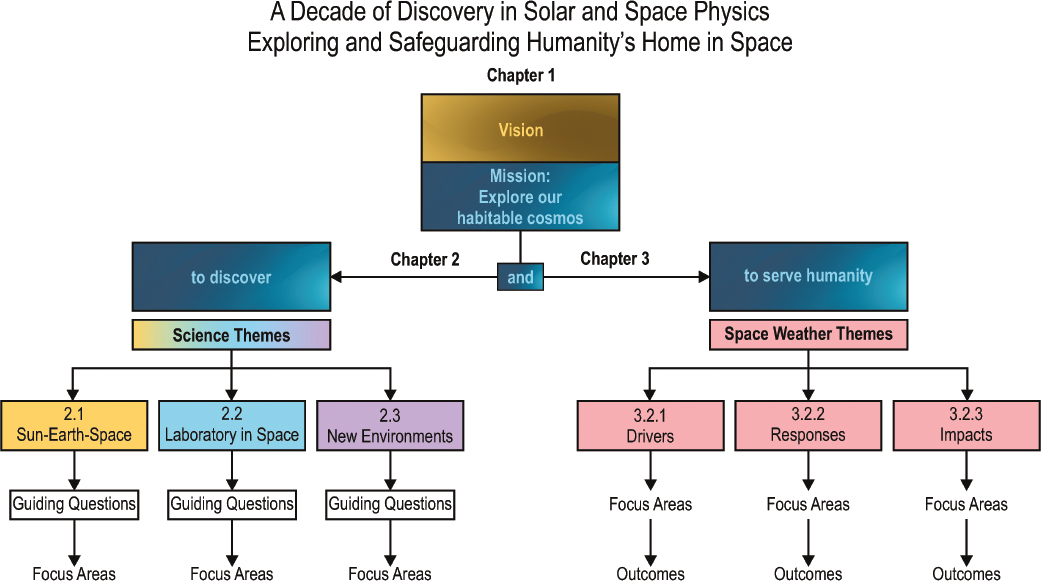

The aspirational vision for this decadal survey (Figure 1-15) focuses on discovering the mysteries of our local cosmos while also applying the knowledge gained to serve and safeguard humanity’s home is space.

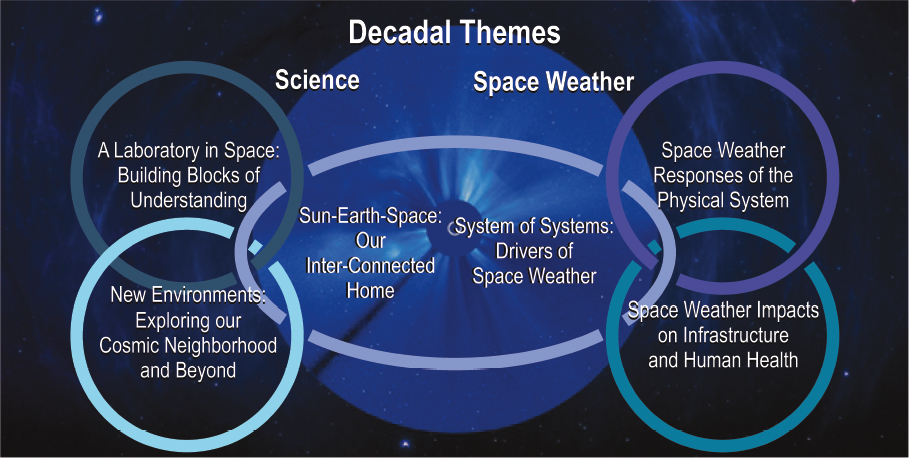

The solar and space physics vision and mission for the next decade and beyond translates into a broad set of themes that encompass the scientific and space weather goals for the next decade. The paramount strategy targets discoveries arising from new environments in novel ways, embracing the expansion of the field to cover the local cosmos and beyond. An overarching element underpinning these discoveries is understanding the processes from which this dynamic system is constructed. Under the umbrella of “Exploring Our Local Cosmos,” the basic science themes for the next decade are as follows (see Figure 1-16):

- Sun–Earth–Space: Our Interconnected Home

- A Laboratory in Space: Building Blocks of Understanding

- New Environments: Exploring Our Cosmic Neighborhood and Beyond

SOURCE: Composed by AJ Galaviz III, Southwest Research Institute.

SOURCES: Composed by AJ Galaviz III, Southwest Research Institute; Center image from NASA, U.S. Naval Research Laboratory.

These science themes are integrally linked to a set of themes that shape space weather research for the next decade. For space weather, it is important to address individual impacts on particular physical systems as well as on technological systems and humans in space, in the air, and on the ground. Under the umbrella of service to humanity, the three space weather themes for the next decade are as follows (see Figure 1-16):

- System-of-Systems Drivers of Space Weather

- Space Weather Responses of the Physical System

- Space Weather Impacts on the Infrastructure and Human Health

These six themes provide a thematic roadmap for the science and space weather goals of the next decade and beyond and are discussed in detail in Chapters 2 and 3. The flow-down from the science and space weather themes is shown in Figure 1-17. Because science and space weather goals are not accomplished without a vibrant and engaged solar and space physics community, this evolving workforce and the challenges for the next decade are discussed in Chapter 4. In Chapter 5, the science, space weather, and state of the profession come together in a comprehensive, balanced, and integrated research strategy. In Chapter 6, the integrated research strategy is summarized and the budget implications for this strategy are considered.

SOURCE: Composed by AJ Galaviz III, Southwest Research Institute.

REFERENCES

Bahauddin, S.M., C.E. Fischer, M.P. Rast, I. Milic, F. Woeger, M. Rempel, P.H. Keys, et al. 2024. “Observations of Locally Excited Waves in the Low Solar Atmosphere Using the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope.” The Astrophysical Journal Letters 971(1). https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/ad62f8.

Baker, D.N., S.G. Kanekal, V.C. Hoxie, M.G. Henderson, X. Li, H.E. Spence, and S.G. Claudepierre. 2013. “A Long-Lived Relativistic Electron Storage Ring Embedded in Earth’s Outer Van Allen Belt.” Science 340(6129):186–190. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1233518.

Christensen, A.J., and S. Merkin. 2023. “Geomagnetic Storm Causes Satellite Loss.” NASA Scientific Visualization Studio. https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/5193.

Eastes, R.W., S.C. Solomon, R.E. Daniell, D.N. Anderson, A.G. Burns, S.L. England, et al. 2019. “Global-scale Observations of the Equatorial Ionization Anomaly.” Geophysical Research Letters 46. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL084199.

Martinez-Pillet, V., F. Hill, H.B. Hammel, A.G. de Wijn, S. Gosain, J. Burkepile, C. Henney, et al. 2020. “Synoptic Studies of the Sun as a Key to Understanding Stellar Astropheres.” White paper submitted to the Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics. https://baas.aas.org/pub/2020n3i110.

McDowell, J. 2024. “Satellite Statistics: Satellite and Debris Population: Active Sats vs Time.” https://planet4589.org/space/stats/active.html.

NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). n.d. “Eyes on the Solar System.” Parker Solar Probe. Last modified November 9, 2023. https://science.nasa.gov/mission/parker-solar-probe.

NASA. 2004. “Blue Marble—A Seamless Image Mosaic of the Earth (WMS).” Goddard Space Flight Center, Scientific Visualization Studio. https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/2915.

NASA. 2012. “The Van Allen Probes (formerly Radiation Belt Storm Probes-RBSP) Explore the Earth’s Radiation Belts.” Goddard Space Flight Center, Scientific Visualization Studio. Released May 8. https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/3951.

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). n.d.a. “Aurora Forecast.” Space Weather Prediction Center. https://www.swpc.noaa.gov. Accessed April 24, 2023.

NOAA. n.d.b. “Customer Growth SWPC Production Subscription Service.” Space Weather Prediction Center. https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/content/subscription-services. Accessed May 21, 2024.

NOAA. 2017. Social and Economic Impacts of Space Weather in the United States. National Weather Service. Abt Associates. https://www.weather.gov/media/news/SpaceWeatherEconomicImpactsReportOct-2017.pdf.

NRC (National Research Council). 2013. Solar and Space Physics: A Science for a Technological Society. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13060.

NSF (National Science Foundation). 2023. “WACCM-X Simulation of Tonga Eruption Impact on the Lower and Upper Atmosphere.” NCAR VisLab, CISL Visualization Gallery. https://visgallery.ucar.edu/tonga-eruption.

NSO (National Solar Observatory). n.d. “The DKIST Telescope Enclosure and Support and Operations Building at the Site.” National Science Foundation. https://nso.edu/telescopes/dkist/fact-sheets/dkist-overview. Accessed January 2024.

NSO. 2024. “Images from the Inouye Solar Telescope.” https://nso.edu/gallery/gallery-images-from-the-inouye.

NSTC (National Science and Technology Council). 2019. National Space Weather Strategy and Action Plan. Space Weather Operations, Research, and Mitigation Working Group; Space Weather, Security, and Hazards Subcommittee; Committee on Homeland and National Security. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/National-Space-Weather-Strategy-and-Action-Plan-2019.pdf.

NSTC. 2022. Space Weather Research-to-Operations and Operations-to-Research Framework. Space Weather Operations, Research, and Mitigation Working Group; Committee on Homeland and National Security. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/03-2022-Space-Weather-R2O2R-Framework.pdf.

Olson, M. 2019. “NASA Eyes GPS at the Moon for Artemis Missions.” NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/image-article/mms-space-concept.

Pulkkinen, T., T.I. Gombosi, A.J. Ridley, G. Toth, and S. Zou. 2021. “The Space Weather Modeling Framework Goes Open Access.” Eos. https://eos.org/science-updates/the-space-weather-modeling-framework-goes-open-access.

Sorathia, K.A., A.Y. Ukhorskiy, V.G. Merkin, J.F. Fennell, and S.G. Claudepierre. 2018. “Modeling the Depletion and Recovery of the Outer Radiation Belt During a Geomagnetic Storm: Combined MHD and Test Particle Simulations.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 123:5590–5609. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA025506.