The Next Decade of Discovery in Solar and Space Physics: Exploring and Safeguarding Humanity's Home in Space (2025)

Chapter: Appendix D: Report of the Panel on the Physics of Ionospheres, Thermospheres, and Mesospheres

D

Report of the Panel on the Physics of Ionospheres, Thermospheres, and Mesospheres

D.1 INTRODUCTION

The decadal charter for the Panel on the Physics of Ionospheres, Thermospheres, and Mesospheres (ITM panel) is to identify the highest-priority science goals (PSGs) for the coming decade and develop a compelling research strategy to address those goals that incorporates both ground- and space-based investments, model development, interdisciplinary emerging opportunities, and enabling capabilities needed to lay the groundwork for continued advancement in future decades. Per the ITM panel statement of task, this report assumes that the Geospace Dynamics Constellation (GDC) and Dynamical Neutral Atmosphere–Ionosphere Coupling (DYNAMIC) missions will be executed as a prerequisite to the strategic implementations described in this report.

The vision presented in this panel report reflects an overall paradigm shift relative to past reports, which is motivated by a growing recognition that the ionosphere–thermosphere–mesosphere (ITM) is more than just the bridge between the lower atmosphere and magnetosphere. Instead, the ITM represents within geospace the clearest example of physical complexities that require a system science approach to their investigation.

The ITM hosts a myriad of processes encompassing chemical reactions, fluid dynamics, plasma physics, and their coupling, as the atmosphere transitions from a predominantly well-mixed neutral gas to a magnetized plasma. Beginning nearly 100 years ago with the discovery of the Appleton Anomaly and extending to the dramatic ITM response to the 2022 Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha‘apai volcanic eruption, the community has mostly focused on individual phenomena or state parameter observations to elucidate the underlying ITM processes. Furthermore, the limitations in the technological capabilities, budget resources, and interagency coordination of the past 2 decades drove previous decadal surveys to construct phenomenologically focused goals within individual regions. Although this approach served the community well for that time, the next great step for ITM science is to delve into the intricacies of the processes acting on and within the ITM when viewed as a system. This endeavor requires a transformative system science approach that is reflected in the next decade’s science goals and implementation strategies, which are detailed in the sections that follow.

Science theme: Embrace a system perspective as an enabling paradigm for understanding complexity in the ITM and in the geospace system in which the ITM is embedded.

As illustrated in Figure D-1, further advances in ITM science require that the research be conducted within a system science paradigm that emphasizes the complex linkages between different regions, scales, domains, and processes; quantifies the relative significance of competing causal pathways; and establishes the baselines from which emergent behavior can be distinguished.

SOURCE: CEDAR (2011), https://cedarscience.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/CEDAR_Plan_June_2011_online.pdf.

National awareness of the importance of the ITM region to U.S. infrastructure has grown in recent years, as demonstrated by the establishment of the 2019 National Space Weather Strategy and Action Plan (SWSAP) (NSTC 2019) and the 2020 Promoting Research and Observations of Space Weather to Improve the Forecasting of Tomorrow Act (PROSWIFT 2020). The ITM manifests many different space weather phenomena that are known to adversely affect numerous technological systems and applications in the public and governmental sectors. It is imperative that the ITM community make significant progress in the fundamental understanding of the ITM as an interconnected system if we are to meet society’s space weather forecasting needs and fulfill obligations defined by the PROSWIFT Act.

A transformation in the approach to implementation is required to support ITM’s system science focused goals. The traditional paradigm of isolated and often temporary observational platforms and experiments within the discrete ionosphere, thermosphere, and mesosphere regions is no longer adequate. Beginning with the key system science–centric GDC and DYNAMIC missions, the next decade’s implementation strategy emphasizes multipoint, multistate observations and well-coordinated heterogeneous observations that together address the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) priorities and needs.

Overall implementation strategy: Conduct research within a system science paradigm that emphasizes the complex linkages between different regions, scales, domains, and processes of the ITM; quantifies the relative roles of competing causal pathways; and establishes the baselines from which emergent behavior can be distinguished.

The implementation strategy presented in this panel report requires investment in new approaches to conducting ITM research, such as harnessing opportunities to access space, establishing distributed and heterogeneous ground-based instrument networks, and utilizing next-generation data science tools and modeling.

Programmatic implementation strategy: Establish an overarching interagency framework to coordinate the use of diverse assets for ITM research throughout all programmatic levels.

A key part of achieving these system science goals in the next decade can only be realized through the observations provided by the GDC and DYNAMIC missions, flying jointly. By simultaneously observing key ion, neutral, chemical, and electrodynamic parameters in multiple local time and longitude sectors, GDC and DYNAMIC will provide the crucial foundation upon which to grow ITM system science, especially when tightly coordinated with ground-based sensors, which provide key altitude-resolved information within rapid and highly variable ion-neutral interaction pathways, and models, which provide insight into the underlying physical processes that govern the observed responses.

Foundational implementation strategy: Within the next decade, implement the primary GDC and DYNAMIC missions contemporaneously and ensure the availability of strategic ground-based observational assets and modeling.

In summary, the ITM is a unique natural laboratory that is invaluable for advancing interdisciplinary science. The priority science goals and objectives defined in Sections D.3 and D.4, along with the implementation strategies defined in Sections D.5 and D.6, reflect the tremendous benefit of transforming the ITM community’s focus toward system science investigations that advance both fundamental and applied knowledge. The ITM community is well positioned to make incredible scientific progress over the next decade through the implementation of the strategies described in this report. These efforts are well suited to promote engagement and training of the next generation of scientists and engineers, thus ensuring a vibrant future for ITM system science.

D.2 CURRENT STATE OF IONOSPHERE–THERMOSPHERE–MESOSPHERE SCIENCE

Over the past decade, the ITM community made significant advances in the understanding of the ITM system through projects and vigorous programs promoted at the community, national, and international levels. Diverse programs within agencies, as well as initial multiagency efforts, resulted in scientific discoveries of new phenomena and expanded understanding of the interconnection and importance of the underlying physics to the overall geospace system. These important findings have only reinforced the growing need for a holistic, system-focused approach to ITM research that emphasizes understanding the vast transition in governing physics over this altitude range in near-Earth space, which is critical to modern technological society.

A common hallmark of recent discoveries, emphasizing the need for system approaches, is rooted in the community’s growing understanding of the large number of simultaneous pathways and processes spanning the ITM, both within and external to it. Most components of the upper atmosphere interact in two-way feedback loops, including lower atmosphere forcing of the upper atmosphere, dynamic ion-neutral coupling, and variable solar and magnetospheric influences.

Studies of the ITM system forcing during natural events revealed the importance of coupled dynamic processes. The August 2017 total solar eclipse, traveling over the heavily instrumented continental United States, revealed a rich spectrum of propagating ionospheric disturbances during the supersonic eclipse shadow passage.

This unique event drove advances in whole atmosphere modeling capabilities and quantitative understanding of nonuniform solar extreme ultraviolet (EUV) flux influences on ITM ionization. The resulting whole atmosphere model improvements were also part of general Coupling, Energetics, and Dynamics of Atmospheric Regions (CEDAR) community progress in multiscale and data-driven modeling along with data assimilation. Such efforts are broadly important and provide insights into long-standing problems such as a quantitative understanding of sunset and sunrise ionospheric dynamics, ionospheric variability (important for space weather and its operational effects), ion-neutral coupling, and preconditioning influences.

The 2022 Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha‘apai underwater volcanic eruption provided a rare example of extreme natural forcing that spurred community efforts into understanding whole ITM system responses to forcing. The eruption injected huge amounts of water vapor into stratospheric circulation and launched a myriad of atmospheric waves that were unexpectedly observed to propagate around the world several times. The ITM response also included large-scale ionospheric electron density depletions extending well beyond equatorial latitudes. This unprecedented forcing event has accelerated efforts to use the ITM system-wide Tonga response to better understand whole atmosphere coupling through studies that emphasize the importance of gravity wave forcing from the lower atmosphere, filtering effects of wave breaking and regeneration in the mesosphere and lower thermosphere, subsequent driving of pronounced ionospheric features, and the role of background thermospheric winds in mediating transient behavior.

Significant progress in the past decade has been made on the long-standing topic of the ITM’s complicated response to magnetic storms. The severe effects of the St. Patrick’s Day 2013 and 2015 storms, along with combined coronal mass ejection (CME) and intense X-class solar flare impacts in the strong September 2017 event, have shown that both ionized and neutral ITM components have dynamic responses (e.g., neutral wind surges driven by intense cross-field ion flows) with different relative influences and recovery times. During storms, deep ionospheric electron density depletions, known as “super-bubbles,” have been observed during storms to extend across a wide range of background magnetic field angles, from equatorial latitudes to the plasmasphere boundary layer, challenging traditional regional-based concepts of ITM electrodynamic coupling and demanding a holistic approach to their analysis.

In recent years, researchers analyzing historical data from the Two Wide-angle Imaging Neutral-atom Spectrometers (TWINS) and Thermosphere, Ionosphere, Mesosphere Energetics and Dynamics (TIMED) satellite missions discovered that the neutral exosphere also exhibits large density perturbations in response to geomagnetic storms. Because these disturbances span thousands of kilometers across Earth’s near-space environment and involve thermal and nonthermal coupling of the exosphere with ambient ions and neutrals, a complete understanding of their origin and impact on the geospace system requires a systems science framework. NASA’s Carruthers Geocorona Observatory, a NASA Heliophysics science mission of opportunity scheduled for launch in 2025, will provide the first dedicated observations of global exospheric structure and dynamics needed to assess the role of exospheric charge exchange in mediating both atmospheric escape as well as the geospace response to geomagnetic storms, through the dissipation of magnetospheric ring current energy and the ionospheric replenishment of storm-driven plasmaspheric depletions.

Ion-neutral charge exchange is a fundamental ITM process during quiet geomagnetic conditions as well, particularly between singly ionized oxygen (O+) and neutral atomic oxygen and hydrogen (O and H), the dominant constituents in Earth’s upper atmosphere. Because O-O+ charge exchange transfers momentum and energy between the ionosphere and thermosphere, the cross section governing this interaction strongly influences calculations of plasma drift speeds, diffusion coefficients, frictional heating, and the altitude distribution and density of the ionospheric F-region. Recently, using a decades-long baseline of optical and radar data acquired from the Arecibo Observatory, historical discrepancies among aeronomical estimates of O-O+ charge exchange efficacy were reconciled with modern theoretical calculations, and recent laboratory measurements were found to be consistent with the ionospheric data. Resolution of this long-standing controversy has reduced a major source of physics-based model uncertainty and established O+ momentum and energy balance techniques as a reliable means of ground-based remote sensing of thermospheric O density using altitude-resolved data from IS radar facilities.

Over the past decade, a few space-based missions have also yielded long temporal baselines of ITM parameter measurements through their serendipitous continuation in operation well beyond their planned lifetimes. As the

sixth oldest Heliophysics Division mission in operation, the TIMED satellite has provided nearly continuous, high-cadence observations of the solar EUV flux as well as mesospheric temperature and composition over its more than 20-year operational span. These data have revealed significant mesospheric cooling trends with strong spatial dependencies. Mesospheric cooling was also observed by the Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesosphere (AIM) mission, based on its own 16-year duration of observations of noctilucent cloud formation at polar latitudes. Whole atmosphere modeling studies have long indicated that these observed ITM cooling trends are harbingers of global climate change in response to anthropogenic changes in atmospheric composition at Earth’s surface. Models also predict that the response of the ITM system to Earth’s climate evolution is highly complex, involving not only temperature and density variations but also changes in mesospheric chemistry, gravity wave generation, atmospheric circulation, and more.

Much progress has been made recently in improving the understanding of the ITM as a dynamically coupled system subject to variable external and internal drivers, particularly regarding the coupling between neutral and plasma populations. For example, the Ionospheric Connection Explorer (ICON) mission provided the first wide-scale observational quantification of the significance of atmosphere–ionosphere coupling mechanisms (e.g., dynamo electric fields, ion drag, and composition carried by tides and planetary waves) using coordinated measurements of low-latitude neutral winds, plasma flows, composition, and densities. In particular, ICON revealed the importance of neutral winds at 100–150 km altitudes in driving ionospheric variability. The Global-scale Observations of the Limb and Disk (GOLD) mission, with its unique geostationary fields of view, has enabled observations of the lower thermosphere temperature and composition, as well as the ionosphere, at an unprecedented temporal and spatial resolution. GOLD has used these capabilities for multiple scientific findings, including the unanticipated range of variability and structure of the nighttime ionosphere, especially of the Equatorial Ionization Anomaly. GOLD also revealed complex structures in neutral composition (O/N2 ratio) based on observations of airglow generated by conjugate photoelectrons. Both GOLD and ICON observations have also shown the high sensitivity of the ITM to magnetospheric forcing even for the case of relatively small disturbances occurring during solar minimum.

Meanwhile, other ITM ion-neutral coupling investigations have revealed new and unexpected pathways. One example is the Weddell Sea Anomaly, which is characterized by the midnight summertime electron density in the Southern Pacific Ocean exceeding the midday electron density by a factor of 2. Because of the correlation with magnetic field declination and inclination in this region, the phenomenon was long attributed to the action of neutral winds. However, recent model analyses, constrained by key satellite data, showed that neutral thermospheric composition is a much more important influence on ionospheric density than the winds, with similar results explaining northern summer anomalies west of the Bering Sea. Such studies highlight the acute community need to better understand neutral composition dynamics as a means to understand charged species behavior.

Midlatitude and subauroral regions also exhibit dynamic features that challenge conventional understanding. Storm-time deep electron density depletions, driven by and associated with complex electrodynamic forcing and intense neutral flows, have unexpectedly been found stretching continuously from equatorial regions through midlatitudes into the plasmasphere boundary layer. Optical signatures with unusual spectrographic properties, such as subauroral emissions (Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancements [STEVEs]) containing both broad spectral features and spatially structured emissions, have been discovered well equatorward of the aurora with unexpected connections to long-known stable auroral red (SAR) arc signatures in the ring current footprints. STEVE features are associated with extreme and unusual fine-scale plasma and neutral atmospheric dynamics, including highly supersonic ion flow velocities (~5–10 km/s or more) and extreme electron temperatures (>6,000 K), conditions that lie at the edge of current modeling capabilities. Furthermore, the transformation of the subauroral region into these extreme conditions can occur within minutes. These newly discovered phenomena significantly challenge the understanding of ITM electrodynamics and aeronomy, given the limitations of available instrumentation and the sparsity of observations both spatially and temporally.

The auroral region, in contrast, is relatively well instrumented, and significant progress has accordingly been made over the past decade in understanding ITM coupling to the magnetosphere at high latitudes, particularly regarding the magnetospheric source of pulsating aurora and its associated energy input as well as auroral generation mechanisms related to field-line-resonance arcs. Beyond terrestrial systems, this understanding of Earth’s auroral system has been applied to new observations at Jupiter by the Juno satellite, where many of the same

processes (and a few others) work together in a very different morphology. For instance, on Jupiter, bidirectional broadband auroral particle acceleration dominates, leading to visible features even in downward current regions. This formerly confusing signature is now understandable owing to an improved understanding of similar processes operating at Earth.

The past decade has also seen an increased recognition, through numerous serendipitous observations, of direct magnetosphere–ionosphere coupling effects from high-energy particle precipitation >1 MeV at auroral latitudes that generates odd nitrogen oxide (NOx) deep within the lower atmosphere. Subsequent transport greatly accelerates persistent, catalytic ozone loss in the polar winter. Understanding these important processes, and their feedback connections, is truly a system-scale challenge and awaits a comprehensive coupled whole atmosphere modeling and dedicated observational effort that includes constraints on energetic particle populations in the overlying magnetosphere.

The preceding summary of the current state of knowledge about the ITM is necessarily incomplete, but the examples mentioned in this section illustrate the significant and exciting progress that has been made over the past decade. However, despite this success, much more remains to be learned about the fundamental processes that govern the complex ITM response to its highly variable and evolving system drivers on multiple scales. The next section describes a set of PSGs and focused science objectives, which are designed to motivate the next decade’s development of observational, modeling, and data analysis capabilities needed to advance understanding of the ITM as a dynamic system within the broader geospace system as a whole.

D.3 PRIORITY SCIENCE GOALS FOR IONOSPHERE–THERMOSPHERE–MESOSPHERE PHYSICS

The discoveries described in Section D.1 point to a compelling need for system science approaches to ITM research. This need arises from the scientific requirement to comprehensively understand the vast number of processes acting simultaneously within this region. Developing this understanding requires approaches that accommodate the observational, modeling, and theoretical challenges posed by the wide variety of interactions between neutral and ionized species over the altitude ranges spanned, along with the collective effects of processes that range over many decades in both spatial and temporal scales.

Accordingly, the ITM panel has codified the needed system science framework into four PSGs for the 2024–2033 decade. These goals are enumerated and expanded on throughout the remainder of this section. Addressing these goals in a system science framework provides an exciting and transformational pathway toward an ultimate and vital understanding of the atmospheric regions closest to Earth and its inhabitants, along with the dynamic effects of variations in those regions on society and technology.

D.3.1 Priority Science Goal 1: How Are Mass, Momentum, and Energy Exchanged and Transformed at Boundaries Across and Within the ITM System?

The ITM is never an isolated system because it is strongly influenced by neutral particle composition, flows, and temperature variations originating from the stratosphere below and from the magnetosphere and plasmasphere above. The forcing that emerges from the stratosphere includes momentum and energy transfer from gravity waves and sudden stratospheric warmings. The coupling to higher altitudes includes absorption of solar radiation, plasma transport between the ionosphere and plasmasphere, and gravitational escape of light neutrals. In addition to these external boundaries, internal transitions in governing physics constitute another important type of boundary in the ITM system. The transformation of mass, momentum, and energy across these internal transition regions has a profound influence on both the equilibrium behavior and dynamics of the ITM state. Feedback across both external and internal boundaries is almost always bidirectional and can be highly sensitive to initial conditions (preconditioning).

In the 2013 solar and space physics decadal survey (NRC 2013; hereafter the “2013 decadal survey”), multiple science goals of the Panel on Atmosphere–Ionosphere–Magnetosphere Interactions (AIMI) focused on interactions across external ITM boundaries. AIMI Science Goal 1 (“How does the IT system respond to, and regulate,

magnetospheric forcing over global, regional, and local scales?”), AIMI Science Goal 2 (“How does lower atmosphere variability affect geospace?”), and AIMI Science Goal 3 (“How do high-latitude electromagnetic energy and particle flows impact the geospace system?”) all recognize the importance of inputs to the ITM system in driving the steady state and dynamical behavior of the system. The panel finds that these science goals of the previous decade are valuable and can be built upon to inspire innovative research in the next decade.

However, although great progress was made with the 2013 AIMI science goals that focused on isolated regions and physical processes, this narrow focus is not sufficient for future ITM progress, which demands a strong systems science approach. In particular, the previous decade’s strategy treated input drivers separately without fully allowing for the very important complex, nonlinear interaction of drivers that can occur at the same time. Furthermore, the previous strategy did not sufficiently focus on interactions across important internal boundaries of the ITM system. For these reasons, ITM science needs to directly address these gaps by explicitly incorporating both external and internal exchanges and transformations at boundaries.

The following sections describe specific scientific objectives identified by the panel within PSG 1 for which significant progress can be achieved in the next decade.

Priority Science Goal 1, Objective 1.1: Determine the Mechanisms of Energy and Momentum Transformation and Exchange During and After Extreme Impulsive Events

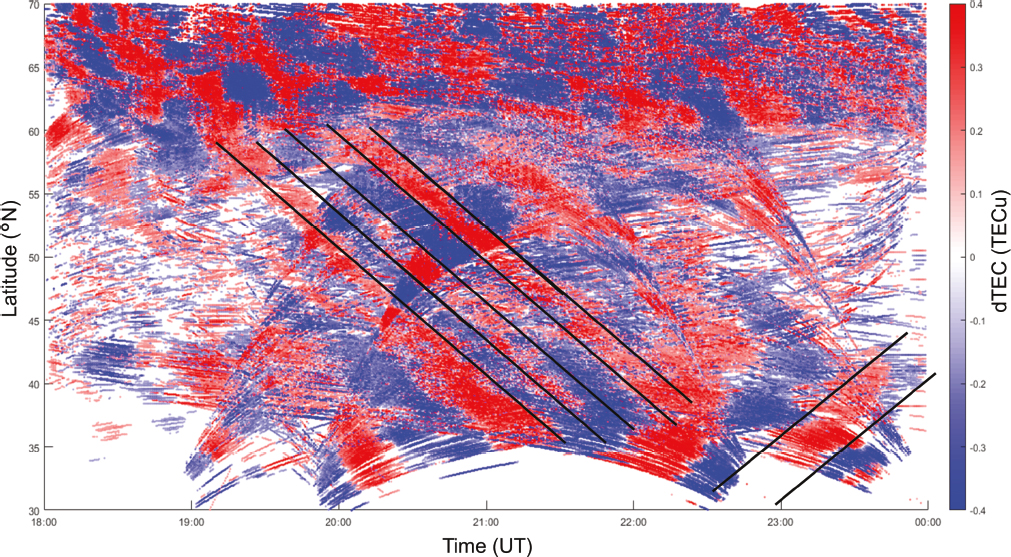

For decades, study of variability in the ITM system has involved elucidating the response to geomagnetic storm forcing, which manifests as sharp impulsive inputs through such events as interplanetary magnetic field reconfigurations associated with coronal mass ejections. (See Appendix B for more details.) Through multiple mechanisms including electrodynamic, composition, and kinetic pathways, geomagnetic storms trigger large and complex perturbations in all ITM state variables on multiple temporal and spatial scales. Understanding this storm-time forcing and its impacts on system response is by no means a closed topic and remains a vital part of community research. Alongside these efforts, the past 2 decades have seen a great deal of additional attention paid toward another vital element in the ITM dynamic picture, through observing and modeling the importance and impacts of transient event influences from the lower atmosphere. These events force significant ITM dynamic wave responses in the form of phenomena such as traveling ionospheric disturbances (TIDs) and traveling atmospheric disturbances (TADs). For example, the massive submarine volcanic eruption of Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha‘apai drastically increased stratospheric atmospheric water vapor concentrations and generated a large ITM system response, which manifested in part as globally propagating waves (Figure D-2). Additional examples of extreme, impulsive external forcing on the ITM include tsunamis, tornadoes, human events (explosions), coronal mass ejections, and solar flares.

For the study of these extreme events, the current research strategy integrates space-based missions, ground-based instrumentation, theory, and modeling, which are essential to properly elucidate mass, momentum, and energy exchange for these events. For example, NSF CEDAR and NASA’s upcoming DYNAMIC mission study how wave action drives ITM energetics and dynamics, and therefore will capture and measure the impacts on the ITM from extreme and transient events.

Priority Science Goal 1, Objective 1.2: Determine the Time-Varying, Two-Way Electrodynamic Linkages and Mass Flow/Transport Processes Between the Ionosphere, Plasmasphere, and Magnetosphere

Magnetospheric and ionospheric processes (and associated ITM dynamics) are tightly coupled on multiple spatial and temporal scales through a variety of mechanisms. For example, the Birkeland Region 1 upward field-aligned currents (downward electron precipitation) within auroral regions cause conductivity variations that feed back on electron acceleration. Field-aligned heat conduction at subauroral latitudes in the Region 2 field-aligned current (ring current) footprints during storm periods leads to significant ionospheric and thermospheric temperature increases associated with SAR arcs. Electrodynamic feedback mechanisms in the subauroral regions lead to multiple responses. For example, broad (degrees wide) ionospheric flow channels known as subauroral polarization streams (SAPS) carry significant heavy ion mass to cusp outflow regions with subsequent travel out to the

SOURCE: Verhulst et al. (2022), https://www.swsc-journal.org/articles/swsc/full_html/2022/01/swsc220017/swsc220017.html. CC BY 4.0.

inner magnetosphere. Electric fields and currents lead to narrow, highly supersonic ionospheric flows known as subauroral ion drifts (SAIDs) and fine-scale neutral atmospheric responses known as STEVEs.

The current ITM science program implementation strategies reflect the importance of these physical processes. The NSF CEDAR and GEM programs work to understand how Earth’s atmosphere is coupled to its magnetosphere through observations, theory, and increasingly realistic models, and the current NASA Heliophysics strategy focuses on the interaction of the extended solar atmosphere with Earth. NASA’s GDC and DYNAMIC’s multiplane, multi-altitude constellation will observe critically needed information on electromagnetic ITM system inputs and responses at mid- and high latitudes. Mid- and high-latitude incoherent scatter (IS) radars (Millstone Hill, Poker Flat IS Radar [PFISR]/Resolute Bay IS Radar [RISR]) provide local and regional fine-scale altitude-resolved measurements of key ionospheric state variables (electron and ion density, plasma temperature, and plasma drifts) at both subauroral/midlatitudes and high latitudes. Ground-based all-sky imagers and Fabry-Pérot interferometers have long used airglow to study the occurrence and causes of auroral arcs and have recently also studied neutral response to extreme subauroral phenomena such as STEVE.

PSG 1 embraces these space- and ground-based sensing tools and motivates their continued use by affirming and emphasizing the ongoing need to understand the two-way coupling between the ITM, plasmasphere, and magnetosphere. More accurate representation and understanding of this coupling will advance knowledge of the transfer and transformation of mass, momentum, and energy, which pervades the ITM system response to these inputs.

Priority Science Goal 1, Objective 1.3: Determine How the ITM Responds to Lower Atmosphere Forcing on Local and Global Scales

The ITM system has been shown to be extremely sensitive to lower atmosphere forcing, especially during periods of minimal solar activity. The 2013 decadal survey recognized the importance of lower atmosphere forcing on the ITM. However, there remain multiple critical and unresolved issues relating to the impact of

the lower atmosphere on the ITM and how the ITM responds on local and global scales. For example, the state of the stratospheric vortex has been recently shown to significantly alter the composition of the lower thermosphere. Figure D-3 shows the NASA GOLD mission’s observations of O/N2 composition during a sudden stratospheric warming (SSW) event, where O/N2 is depleted during this event. Open questions remain about how the circulation is altered owing to the state of the vortex and how the composition is altered in both latitude and longitude.

A heterogeneous approach to observation and analysis is required to further elucidate the forcing of the lower atmosphere on the ITM system. The current NSF CEDAR strategy, “CEDAR: The New Dimension” (CEDAR 2011), reflects this approach by employing theory, modeling, and observations from both ground-based and space-based platforms to study changes in the whole atmosphere with a strong emphasis on system science. The TIMED mission is an example of a current extended mission that provides a more than 20-year observational baseline for studying the energy transfer into and out of the mesosphere and lower thermosphere. In the next decade, it will be important to make continuity of measurements a priority for the successful closure of this science objective. The upcoming DYNAMIC mission will provide critical information about the forcing from below that comes from waves and tides and, depending on mission configuration, can also separate in situ forcing from upward-propagating tides. Furthermore, the simultaneous availability of DYNAMIC and GDC observations is an essential need for this area through characterizing tides in the 110–250 km “thermospheric gap” (DYNAMIC) at the same time as understanding day-to-day tidal variability and mean state variability with good spatial and temporal coverage (GDC).

SOURCE: Oberheide et al. (2020).

Priority Science Goal 1, Objective 1.4: Elucidate the Mechanisms That Govern the Transition in Chemical, Dynamical, and Thermal Drivers Across the ITM from ~100–200 Kilometers

Within the lower thermosphere and ionosphere, many state parameters within the region between 100–200 km exhibit complex transitions as a function of altitude. For example, one set of tides and waves dominates at the lower end of this altitude range, but a pronounced transition to a different set of tides and waves occurs at higher altitudes, as shown in Figure D-4. The altitude, location, and timing of this transition is still unknown, as well as the processes that govern it. It also remains unclear what the variation in behavior is for this important transition on hourly, daily, and seasonal timescales. Closing these knowledge gaps is critical to forward progress.

Efforts to date have focused on addressing these knowledge gaps in several areas. ITM PSG 1 encompasses NASA’s Heliophysics Division strategy through the science of examining drivers and inputs into the ITM system.

![Height versus latitude distributions of amplitude of zonal wind for Hough Mode Extensions (model) of different tides (DE3 mode [Top], DE2 mode [Middle], and DE1 mode [Bottom]) corresponding to F10.7 = 125 s.f.u. These calculations indicate that different tides should dominate at different altitudes. However, very few relevant observations are currently available.](https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/27938/assets/images/img-406.jpg)

SOURCE: Forbes and Zhang (2022).

NASA’s planned DYNAMIC mission will focus on how wave action alters this transition region through remote sensing techniques. These mission goals directly address PSG 1.4 by affirming the need to understand the chemical, dynamical, and thermal drivers of the 100–200 km transition region. This transition region is also of special interest to the current NSF CEDAR program that employs theory, modeling, and observations from ground-based and space-based platforms to study changes in the ITM. Within the observational portfolio, light detection and ranging (LiDAR) instruments enable investigations of vertical life cycles of small-scale waves as they propagate into, and break within, the mesosphere and thermosphere. PSG 1.4 encourages the further extension of LiDAR technologies to higher altitudes. This capability increases understanding of these small-scale waves and how they transfer energy and momentum throughout the system. To match current and future expanded capability, cutting-edge modeling has focused on how this transition region is modified by and controlled by waves.

Synopsis of Priority Science Goal 1

Advancing ITM system science in the next decade requires a thorough understanding of those influencing factors that flow across both external and internal boundaries. To optimally study ITM system behavior in the areas of transformations and exchanges across these important delineating regions, the panel’s identified science objectives are summarized here:

- Determine the mechanisms of energy and momentum transformation/exchange during and after extreme events (e.g., volcanic eruptions, geomagnetic storms).

- Determine the time-varying, two-way electrodynamic linkages and mass flow/transport processes between the ionosphere, plasmasphere, and magnetosphere.

- Determine how the ITM responds to lower atmospheric forcing on local and global scales.

- Elucidate the mechanisms that govern the transition in chemical, dynamical, and thermal drivers across the ITM from ~100–200 km.

D.3.2 Priority Science Goal 2: How Do Internal ITM Processes Transform Energy and Momentum Across a Continuum of Spatial and Temporal Scales?

The key state parameters of the ITM system exhibit structure over spatial and temporal scales spanning several orders of magnitude (see Table D-1). The largest scales cover a significant fraction of Earth’s circumference. Planetary waves and the diffuse aurora are examples of large-scale phenomena. The smallest scales, exemplified by phenomena such as acoustic waves and plasma turbulence, are cases for which kinetic theory is needed. Between these scales lie mesoscale phenomena such as gravity waves and discrete auroral arcs.

Certain spatial and temporal scales are more efficient pathways for energy and momentum transfer than others. For example, planetary waves generated in the lower atmosphere often dissipate before reaching ionospheric

TABLE D-1 Definitions of Scale Sizes in the Ionosphere–Thermosphere–Mesosphere System with Example Phenomena and Approaches

| Scale Sizes | Small Scale | Mesoscale | Large Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal | <1 minute | minutes–hours | >hours |

| Spatial | <1 km | 1–100s km | 1,000s km |

| Example phenomena and approaches |

|

|

|

altitudes. However, nonlinear interactions can imprint planetary-wave signatures upon tides, which propagate to the ionosphere and modulate it with planetary-wave periodicities. Another example is eddy diffusion, which is effective at driving large-scale transport of heat and constituents such as O and NO from the lower and middle thermosphere to the mesopause region. Recombination of O is a major energy source for the mesosphere. Such pathways directly impact the global mean temperature profile and in turn atmospheric stability and the upward propagation of waves. For these reasons, understanding vertical atmospheric coupling is not possible without understanding how wave energy and momentum are transformed across scales. These are just two of many examples, discussed below, that support the notion that bidirectional feedback across scales—a process known as “cross-scale coupling”—is a critical element of ITM system science.

For many important processes, cross-scale coupling is mediated by mesoscale processes. For example, gravity wave propagation is regulated by large-scale background flows associated with tides and planetary waves, while gravity wave dissipation drives global circulation and seasonal temperature changes in the mesosphere and lower thermosphere (MLT). Another example is the coupling of the magnetosphere and ionosphere: small-scale precipitation structures generate ionization, which is advected by high-latitude convection, yielding meso-scale conductivity enhancements that feed back to modulate global distributions of electric potential, field-aligned current, and precipitation. The role of mesoscale processes in transforming energy and momentum in the ITM is a significant knowledge gap to be addressed in the next decade.

A challenge for understanding cross-scale coupling is that no single investigative technique is suitable for all scales. For example, incisive vertically resolved observations, which are required to understand energy and momentum transfer, are often available only from isolated ground-based facilities or single-spacecraft missions and cannot observe the global drivers or responses. The modeling challenge is that it has been numerically impractical to capture realistic small-scale gravity wave effects or plasma irregularities in global first-principles models. Also, these models are inherently limited by the availability of high-resolution data for assimilation and validation. Overall, progress on cross-scale coupling has been hampered by siloed investigations and insufficient coordination of expertise.

The importance of cross-scale coupling for ITM science has been recognized for many years. The 2013 decadal survey AIMI report recognized that “cross-scale coupling processes are intrinsic to atmosphere-ionosphere-magnetosphere behavior.” AIMI Science Goal 4 (“How do neutrals and plasmas interact to produce multiscale structures in the AIM system?”) addresses one of many fundamental processes, ion-neutral coupling, which plays a significant role in ITM structure and evolution on local, regional, and global scales. However, the AIMI strategy did not explicitly promote investigations into coupling across spatial scales, nor did it recognize the importance of temporal cross-scale coupling. Cross-scale coupling is an explicit element of the systems science perspective expressed in “CEDAR: The New Dimension.” Grassroots, community-led efforts have been dedicated to cross-scale coupling via multiyear conference sessions, including an NSF CEDAR Grand Challenge. Part of the motivation for the NSF Distributed Array of Scientific Instruments (DASI) program is the need to observe multiple scales simultaneously. The Diversify, Realize, Integrate, Venture, Educate (DRIVE) Science Centers are beginning to enable the larger team structures needed to analyze and model cross-scale coupling problems in the ITM.

The following sections describe specific scientific objectives identified by the panel within PSG 2 for which significant progress can be achieved in the next decade.

Priority Science Goal 2, Objective 2.1: Determine How the Gravity Wave Spectrum Cascades Throughout the Thermosphere and Impacts the ITM System

Gravity waves from the lower atmosphere significantly modulate the mean state and variability of the ITM. The classic example is the apparent paradox of the summer mesopause being the coldest place in the Earth system. Although solar radiative heating is stronger in the summer, the summer hemisphere is adiabatically cooled owing to the strong summer-to-winter circulation driven by gravity wave dissipation, serving as an example of meso-tolarge-scale energy transfer. Gravity wave energy can also cascade to smaller scales, driving turbulence. Turbulent mixing in the lower thermosphere controls the vertical profiles of chemical constituents like atomic oxygen and determines the thermal structure of the ITM. Gravity waves that reach the ionosphere can generate TIDs and potentially seed plasma instabilities such as equatorial spread F.

SOURCE: Becker et al. (2022).

Gravity wave amplitudes grow with height, a consequence of the conservation of momentum as the neutral density decreases. They can become unstable and break via gravity wave, mean-flow, and nonlinear interactions. This wave breaking is thought to lead to the secondary generation of waves that propagate to higher altitudes. In the thermosphere, this process might repeat in a process known as “multistep vertical coupling.” Figure D-5 shows predictions from a mechanistic model of secondary and higher-order gravity waves permeating the winter thermosphere. The relative importance of primary and higher-order gravity waves is still not well understood, and observations of these processes at work remain exceedingly sparse. Whole atmosphere numerical models of these processes are also not yet comprehensive, as they currently either do not include gravity waves or include only a crude parameterization of their effects because there are not enough observations. For instance, some large models are beginning to explicitly simulate gravity waves, but to date only at large scales (≳200 km).

Observational challenges also remain in this area, depending on the technique used. Gravity wave observations have been mostly limited to nighttime and to the lowest altitudes in the ITM (~85–100 km), via ground-based airglow imagery. These observations can target specific airglow emission lines that originate from different altitudes to provide maps of gravity wave propagation. However, the current observation network provides sparse global coverage and is subject to ambiguities associated with their line-of-sight integrated nature. There are promising avenues emerging to address the situation, in the form of networked multistatic meteor radar sites, which are beginning to yield gravity wave characterizations in a limited altitude range (80–100 km). Gravity waves and wave–wind interactions have been observed by LiDARs, albeit with a limited vertical range and at single-point ground facilities. Gravity wave effects on plasma dynamics (e.g., TIDs) are relatively well observed by radars, ionosondes, and networked global navigation satellite system (GNSS) measurements of total electron content (TEC). These instruments observe the dynamic effects of waves modulating the plasma. Nevertheless, the network sensor distribution remains insufficient to comprehensively understand the full range of longitudinal and local time dependence. Observations in the critical 100–200 km region remain extremely rare.

Modeling gravity wave generation and impacts also remains an active and ongoing challenge, because there is not yet a universally understood and elucidated set of mechanisms for wave vertical propagation and their manifestation. For example, the vertical propagation of the spectrum of waves generated by the recent Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha‘apai volcanic eruption in January 2022 is currently serving as a test case for understanding vertical wave coupling. While observed perturbations in the lower atmosphere have been understood as manifestations of the Lamb wave mode, debate is ongoing over the pathways that caused disturbances observed in the ionosphere.

SOURCE: Vadas et al. (2023).

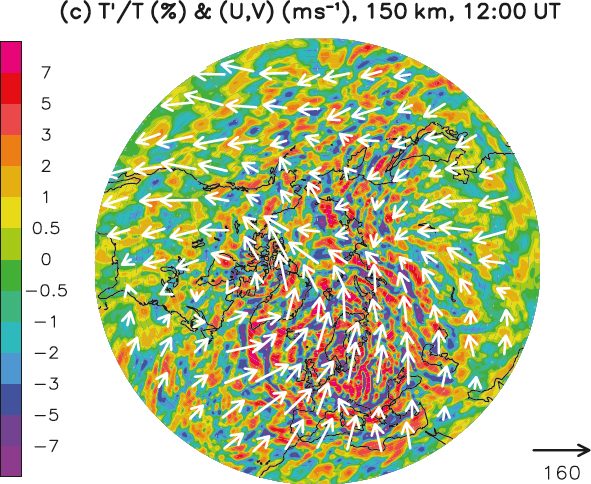

Vadas et al. (2023) have argued that the large thermospheric waves are secondary gravity waves generated by the dissipation of the primary waves from the eruption (Figure D-6). Alternatively, Liu et al. (2023) suggest that the L1’ Lamb pseudomode may be important for understanding the thermospheric signature (Figure D-7). Resolving the relative importance of these mechanisms will rely in the future on more comprehensive observational databases at altitudes between the mesopause and the ionosphere.

No previous NASA missions have directly targeted gravity wave science. Serendipitous observations of thermospheric gravity waves in the daytime were made by ICON Michelson Interferometer for Global High-resolution Thermospheric Imaging (MIGHTI), but only for long wavelengths (≳1,000 km). GOLD conducts rare special campaign modes to observe gravity waves in the disk ultraviolet radiance. Recently launched mission Atmospheric Waves Experiment (AWE) and upcoming GDC will address gravity waves and their effects, but only

SOURCE: Liu et al. (2023), https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL103682. CC BY.

with snapshots at the upper and lower boundaries. The AWE mission will investigate how gravity wave breaking is influenced by background fields and how momentum deposition then influences the wave field. However, AWE will observe 30–300 km scales only at a single altitude (the OH emission altitude ~87 km) and thus will not address cross-scale coupling or global ITM impacts. GDC will make observations of TIDs and TADs in situ (~400 km) but will not address cross-scale coupling. For these reasons, the panel finds that the vertical life cycle of gravity wave momentum and energy is a key knowledge gap to be addressed in the next decade.

Priority Science Goal 2, Objective 2.2: Determine How Small-Scale Structuring in High-Latitude ITM State Parameters Leads to Mesoscale Conductivity Enhancements That Have Aggregate Global Significance

Small-scale filamentary current structures at high latitudes produce significant local heating and ionization. These structures are embedded within regional-scale and global-scale flow fields that convect the newly ionized or heated gas into undisturbed regions. In turn, these sources modify the global ionospheric conductivity at mesoscales. These modifications of ionospheric conductivity can have global effects, and Figure D-8 depicts how

SOURCE: Reprinted from C. Gabrielse, S.R. Kaeppler, G. Lu, C.-P. Wang, and Y. Yu, 2021, “Energetic Particle Dynamics, Precipitation, and Conductivity,” pp. 217–300 in Cross-Scale Coupling and Energy Transfer in the Magnetosphere-Ionosphere-Thermosphere System, Y. Nishimura, O. Verkhoglyadova, Y. Deng, and S.-R. Zhang, eds., Copyright (2021), with permission from Elsevier.

modeled potential and field-aligned current patterns can vary dramatically depending on the nature of the input conductance patterns.

The data-driven result in Figure D-9 relied on Polar UVI’s full-oval imaging, a capability that has not been available since 2005. Partially filling this measurement gap are ground-based all-sky camera arrays (e.g., Themis ground-based observatory [GBO]), which are suited for investigating arc-scale to regional-scale relationships, but observations are available only at night and only when conditions permit (e.g., during clear skies, new moon phase, and low aerosol levels). Past CEDAR efforts, as well as the European LOcal Mapping of Polar ionospheric Electrodynamics (LOMPE), have combined imagery with magnetometer chains and Super Dual Auroral Radar Network (SuperDARN)/IS radar data to investigate high-latitude cross-scale coupling. However, these successes were not part of a current U.S. research strategy, but instead via international, ad hoc, and often unfunded grassroots efforts.

Electronically scannable IS radars (Advanced Modular IS Radar [AMISR], European IS Scientific Association [EISCAT] 3D) provide vital common-volume measurements across multiple spatial scales nearly simultaneously. Other radar techniques (ionosonde, SuperDARN/high-frequency [HF] radar) also provide compelling measurements with different individual strengths, but they require joint rather than individual analysis to address cross-scale coupling. Meanwhile, whole geospace models (e.g., the Multiscale Atmosphere–Geospace Environment [MAGE] model developed as part of a NASA DRIVE center) have the potential for transformative insights into high-latitude, cross-scale coupling. Such models can self-consistently account for cross-scale, magnetosphere–ionosphere–thermosphere coupling processes.

GDC will provide critical surveys of the spatial scales and persistence times of various phenomena associated with the ITM’s response to solar and magnetospheric energy inputs. The phased deployment of the constellation will allow a valuable investigation of individual scales sequentially. However, beyond GDC, coincident observations at various scales remain necessary to assess cross-scale coupling. The upcoming “small mission” Electrojet Zeeman Imaging Explorer (EZIE) (Class D) will investigate current closure at small scales, instantaneously.

NOTE: UFKW, ultra-fast Kelvin wave.

SOURCE: Nystrom et al. (2018).

However, EZIE will address cross-scale coupling phenomena only on a restricted regional scale, not globally. In summary, the panel finds that high-latitude, cross-scale coupling mediated by mesoscale conductivity variability is a key knowledge gap for the coming decade.

Priority Science Goal 2, Objective 2.3: Determine How Nonlinear Coupling Between Mean Neutral Atmosphere Circulation, Tides, and Planetary Waves Drives ITM Variability

A significant amount of observational and theoretical work over the past decade has improved the understanding of how global-scale waves (i.e., tides, planetary waves, and tropical waves) from the lower atmosphere force the ionosphere–thermosphere system. There is direct forcing by penetration into the thermosphere that modifies the chemistry and field-aligned drag, and indirect forcing by altering the neutral wind dynamo. The amplitude of these waves is often nonnegligible relative to the background, in which case second-order terms are important and propagation is nonlinear. This allows for the transfer of wave momentum and energy between different spatial and temporal scales, which can drive a rich spectrum of ITM variability.

The modeling results in Figure D-9 suggest that child waves from nonlinear interactions between primary waves may produce half of the variability of the primary waves at 120 km. Observational evidence for these waves is extremely scarce, often consisting of observations below 100 km, or observations of the plasma response at ~300–400 km, but with little information on the pathways by which these signatures reach the ionosphere. A major observational challenge is that child waves can alias with primary waves in single-spacecraft observations from low Earth orbit (e.g., ICON and TIMED). Full-disk observations from high altitudes (e.g., GOLD) ameliorate aliasing issues, but such remote sensing observations are inherently integrated along the viewing line of sight and are not directly altitude-resolved.

While GDC and DYNAMIC will be foundational for moving this science forward, the missions may still be limited in their ability to completely address nonlinear wave–wave coupling. The DYNAMIC mission is likely to address some aspects of vertically resolved cross-scale coupling within the mesosphere/lower thermosphere, depending on the selected configuration. If DYNAMIC is operated simultaneously with GDC, it will be possible to trace the effects of some wave–wave coupling processes on the middle/upper thermosphere/ionosphere. These contributions will be valuable but inherently limited—for example, if the DYNAMIC budget limits the implementation to two flight elements, it will be difficult to resolve semidiurnal or higher-order tides on subseasonal timescales. Ground-based meteor radar systems distributed around the globe have the potential to provide critical observations of the global neutral wind distribution, but only from ~80 to 100 km.

In aggregate, global-scale wave–wave/mean-flow coupling is a key knowledge gap for understanding ITM variability in the next decade. PSG 2.3 is not necessarily independent of PSG 2.1, because wave–wave coupling processes can include gravity waves. Indeed, the steep wind shears that can cause sporadic E layers are thought to arise from gravity wave/tide interactions. Another example is stratospheric sudden warmings, in which large-scale variations in the polar vortex interact with tides and gravity waves to produce global-scale ionospheric disturbances.

Priority Science Goal 2, Objective 2.4: Determine How Plasma Irregularities Are Driven by and Regulate Large-Scale ITM Phenomena

Plasma turbulence is a frontier of theoretical physics but also has numerous direct applications to heliophysics. Small-scale Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities are generated by, and subsequently regulate, large-scale and mesoscale flow shears that likely control system-level and emergent behavior of fine-scale flow channels such as SAIDs, and their visible signatures known as STEVEs. The auroral convection pattern has mesoscale variability cascading into small-scale instabilities embedded within its synoptic pattern. Farley-Buneman (cross-streaming) instabilities interact with and limit large-scale flow differences between species. Interchange instabilities (e.g., Rayleigh-Taylor) are associated with large-scale equatorial plasma bubbles, an important space weather phenomenon. The potential seeding of bubbles by gravity waves is still being debated. Plasma instabilities causing 150 km echoes are a nearly 30-year mystery recently hypothesized to be driven by coupling between the upper hybrid instability and background photoelectrons, possibly modulated by gravity waves (Figure D-10).

SOURCE: Lehmacher et al. (2019).

With some exceptions, irregularity science has focused mostly on processes occurring at the equator (e.g., using the Jicamarca Radio Observatory IS radar) and in auroral/polar regions (e.g., polar cap patches), but large-scale features that can drive instabilities through cross-scale coupling occur across all latitudes. Electronically scannable IS radars have contributed (AMISR) or will contribute (EISCAT 3D) critical observations of multiple scales simultaneously in regional fields of view. Other radar techniques (ionosonde, SuperDARN/HF radar) also provide compelling measurements with different individual strengths. But to comprehensively address cross-scale coupling between irregularities and large-scale ITM phenomena, measurements and expertise at different scales need to be brought together.

In addition to theoretical treatments and bespoke numerical models, general-purpose high-resolution regional modeling of plasma irregularities and plasma-neutral interactions have captured some cross-scale coupling phenomena. Advances in techniques such as adaptive mesh refinement could enable further progress. The panel finds that understanding of the generation of plasma irregularities and their interaction with larger-scale ITM phenomena is a key knowledge gap for the coming decade.

Synopsis of Priority Science Goal 2

In concert with transport across physical boundaries and transition regions (see PSG 1), the internal exchange of energy and momentum across all spatial and temporal scales, including the vitally important mesoscale range, is a fundamental process whose understanding is essential for ITM system science in the next decade. Accordingly, optimal study of ITM system behavior in energy and momentum dynamics requires effort on the panel’s identified science objectives, summarized here:

- Determine how the gravity wave spectrum cascades throughout the thermosphere and impacts the ITM system.

- Determine how small-scale structuring in high-latitude ITM state parameters leads to mesoscale conductivity enhancements, which have aggregate global significance.

- Determine how nonlinear coupling between mean neutral atmosphere circulation, tides, and planetary waves drives ITM variability.

- Determine how plasma irregularities are driven by and regulate large-scale ITM phenomena.

D.3.3 Priority Science Goal 3: Quantitatively, What Is the Relative Significance of Competing Physical Processes That Govern the ITM State and Its Variability?

The ITM is an interconnected system whose response to its multiple drivers can be characterized by nonlinearity and instability, feedback, preconditioning, and emergent behavior. The evolution of the dynamic ITM state (plasma and neutral density, composition, temperature, and velocity) is governed by the continuity, momentum, and energy equations and their derivative terms, which are nonlinear and can be coupled across multiple scales. While the theory that supports data analysis and numerical modeling is well established, quantitative knowledge regarding the numerous driver/response relationships and their relative significance under different conditions (spatial, climatological, temporal) is underconstrained.

The complexity and interconnectivity of the ITM system can lead to interpretations that rely on observed correlations rather than on underlying physical causal links. One such example is the early interpretation of the cause of the Weddell Sea Anomaly, in which the midnight electron density can exceed the midday electron density by a factor of 2 in the Southern Pacific Ocean in the summer. Because of the correlation with the particular magnetic field declination and inclination in this region, the phenomenon was long attributed to the action of neutral winds. Recent analyses with a model that was constrained by key satellite data showed that the neutral composition is a much more important driver of anomalous electron density than wind effects. This example demonstrates the importance of having sufficient data to constrain important model parameters to determine which ones are most effective. Quantifying the relative significance of competing physical processes, as in this example, is a critical step in system science development, leading to full physical understanding as well as predictive capabilities.

A system-level understanding of the ITM requires moving from correlation-based conclusions to the identification of fundamental causative mechanisms. Such a definitive determination is predicated on accurate and precise quantification of the relative significance of competing physical processes. A system-level understanding of the ITM also must establish baseline behavior to enable both the recognition of emergent behavior as well as the assessment of the sensitivity of a response to the specific nature of background conditions.

Both the 2013 decadal survey and the 2011 NSF CEDAR Strategic Plan (CEDAR 2011) introduced system science, particularly system identification, as a valuable framework for ITM science. The 2013 decadal survey recognized the strong role that modeling and theoretical analysis play in advancing a system science approach, specifically noting that comprehensive models of the AIM system would benefit from “developing assimilative capabilities” and “the development of embedded grid and/or nested model capabilities, which could be used to understand the interactions between local- and regional-scale phenomena within the context of global AIM system evolution.” It also noted that “Complementary theoretical work would enhance understanding of the physics of various-scale structures and the self-consistent interactions between them.” The 2013 decadal survey recommended the implementation of a multiagency initiative, DRIVE, to more fully develop and effectively employ the many experimental and theoretical assets at NASA, NSF, and other agencies to address the need for multidisciplinary data and model integrated investigations of fundamental physical processes.

The proposed PSG 3 supporting strategies in this new decadal survey build on these initiatives and focus future scientific efforts on establishing quantitative, causal links between ITM processes, rather than correlative relationships of unknown significance. The following sections describe specific scientific objectives identified by the panel within PSG 3 for which significant progress can be achieved in the next decade.

Priority Science Goal 3, Objective 3.1: Quantify the Relative Roles of Preconditioning and Seeding Mechanisms in Controlling the Emergence and Evolution of Ionospheric Irregularities

Ionospheric density irregularities are the major source of naturally occurring disruptions of radio frequency transmissions. They span several orders of magnitude in spatial scales (centimeters to hundreds of km) and exhibit

strong day-to-day, seasonal, and longitudinal dependencies. While most common at low latitudes and high latitudes, recent research has shown that there are midlatitude fluctuations measurable through rate-of-TEC variations. At high latitudes, convection and auroral precipitation are associated with scintillations. A number of different plasma instability mechanisms—gradient drift, Kelvin-Helmholtz, temperature gradient instability—are thought to contribute but perhaps to differing degrees in different circumstances.

At low latitudes, the orientation of the magnetic field lines and the interaction of plasma with neutrals may play a significant role in seeding irregularities, although many open questions remain regarding cause and effect. The competing physical mechanisms that govern the initiation, growth, and suppression of equatorial plasma bubbles (EPBs) are not well understood. At low latitudes, potential seeding mechanisms (such as gravity waves), tropospheric events (such as lightning flashes), traveling ionospheric disturbances, prompt penetration electric fields, and the disturbance dynamo have been proposed. There are climatological controlling factors, such as orientation of the terminator with respect to magnetic meridian, and variable factors, such as neutral winds and global electric fields.

On many nights, low-density plasma bubbles emerge from the lower F-region ionosphere and rise quickly to altitudes of 1,000 km, often becoming very turbulent and leading to dramatic height versus time intensity variations. Satellite-based communication and navigation may be disrupted, such that predicting these conditions is an important goal of space weather research.

Past missions that have been used to observe the ITM state during scintillation occurrence include Communications/Navigation Outage Forecasting System (C/NOFS), Constellation Observing System for Meteorology Ionosphere and Climate (COSMIC), COSMIC-2, Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP), GOLD, ICON, Scintillation Observations and Response of the Ionosphere to Electrodynamics (SORTIE), and Swarm. Satellite-based measurements of in situ conditions and associated GNSS loss of lock have played a role in underscoring the space weather import of this question. As an example, Figure D-11 maps the global occurrence of GPS loss of lock for the Swarm A LEO satellite. Combining the satellite observations with ground-based observations has enabled consideration of both the plasma and neutral states during instances of EPBs. Large ground-based facilities, such as Arecibo and Jicamarca, and networks of distributed ionospheric sensors, such as Low-Latitude Ionospheric Sensor Network (LISN), have been key to obtaining these observations.

The relative abundance of scintillation data with even one scintillation receiver, or derivable from a distributed network, has been an impetus for recent initiatives in leveraging data science methods, including artificial intelligence and machine learning. At least one NASA Living With a Star (LWS) Focused Science Team has addressed scintillation-related topics.

One of the challenges with modeling EPBs is the multiple scales and multiple possible phenomena to investigate. There are multiple models that address different possible seeding mechanisms, some that are well equipped to handle global tides and waves, others that model ionospheric plasma, and still others that work at the instability mechanism scales themselves, either modeling the linearized growth rates or directly simulating irregularity development from first principles. Progress has been made in vertically coupling lower atmosphere models to propagate midlatitude convective weather systems up to the thermosphere. These have qualitative similarities to simultaneous traveling ionospheric disturbances (TID) observations, but more cross-model coupling including for different scale sizes is needed to begin to address the seeding mechanism question quantitatively. A developing capability in modeling is emerging bringing multiple models together to cross the scale sizes and boundaries (PSGs 1 and 2). Figure D-12 is an example that points the way: high-resolution models that are one-way coupled (left and middle) bear a striking resemblance to GOLD observations (right).

However, these models are coupled from WACCM-X to SAMI3 (one-way) at present. After adding vertical and multiscale coupling in models, these model outputs then must be further coupled to electromagnetic propagation to show the beginning-to-end connection to scintillation observations. Geospace Environment Model of Ion-Neutral Interactions (GEMINI)+ Satellite-beacon Ionospheric-scintillation Global Model of the upper Atmosphere (SIGMA) modeling is one such example. Further progress is needed in coupling the models, and the question then arises as to whether they will be able to produce enough fidelity to reproduce observations and allow quantitative single comparisons to be made. Because turbulence has elements of a random phenomenon, quantitative measures of significance will need to be developed statistically, which requires many more model outputs than are currently produced, at levels far beyond case studies.

SOURCE: Xiong et al. (2016).

SOURCES: (Left and Middle Panels) Huba and Liu (2020); (Right Panel) Eastes et al. (2019), https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL084199. CC BY.

While progress has been made in data assimilation at global scales in the past decade, including the quantification of uncertainties, none of these assimilative methods operate at scintillation scales. There are no first-principles instability models that can assimilate scintillation measurements. For existing data assimilation techniques, incorporating new measurements from the GDC, DYNAMIC, and AWE missions will help connect the coupling mechanisms. The ENLoTIS (European Space Agency [ESA]/NASA Lower Thermosphere–Ionosphere Science) mission concept could provide comprehensive EPB dynamic features along with their driver measurements, combined with data from small satellite platforms. In particular, continued observation of EPBs, their possible triggering parameters, and the resultant scintillations must be made in order to feed quantitative assimilation solutions for a case-by-case mapping that will unlock progress in cause and effect understanding.

Priority Science Goal 3, Objective 3.2: Quantify the Relative Significance of Competing Drivers of Day-to-Day Variability in the ITM System

Day-to-day variability in the ITM system can arise from changes in several factors. Many competing drivers of the observed variability in the neutral wind field in particular have been identified, including auroral energy deposition, electric fields, gravity wave breaking, nonlinear interactions among various wave types, and ion-neutral coupling. Currently, the predictability of the seasonal, diurnal, and solar cycle variability of neutral winds is poorly characterized because the data sets are too sparse, and the model drivers are not adequately characterized. In addition, the effect of preconditioning on these drivers and the observed mesoscale variability is not well understood.

An ultimate aim is to develop physics-based and assimilative models to accurately predict ITM day-to-day variability (weather) far in advance, similar to tropospheric forecast models. The neutral wind field in the mesosphere and thermosphere exhibits significant temporal variability on timescales of hours to days, even in the quietest geomagnetic conditions. Figure D-13 depicts output from a high-resolution global model simulation that illustrates the type of variability in vertical winds that is caused by orography and tropical cyclones. This variability results in day-to-day modification of the ionosphere electron density. In contrast to tropospheric weather forecasting capability, current physics-based and assimilative models are unable to accurately predict ITM weather conditions.

Recent ITM missions were successful in exploring specific processes. ICON investigated various drivers (composition, neutral winds, dynamo electric fields) and their relative importance to ionospheric variability, but only on large spatial (global) and temporal (seasonal) scales. TIMED characterized the MLT energy budget and quantified contributions to thermospheric cooling.

SOURCE: Liu et al. (2014).

GDC and DYNAMIC are well suited to address important PSG 3 problems through their planned strategic coordination. Through simultaneous operation, they will explore elements of system-level quantification, including the origins and impacts of day-to-day variability. Ground-based observations from IS radars, ionosondes, SuperDARN HF convection radars, neutral airglow Fabry-Pérot instruments, all-sky imagers, and related network efforts also will continue to provide important local and regional/continental scale measurements of ITM variability in a fixed local time sensor view, especially when coordinated with the complementary picture determined from in situ satellite platforms.

Most past and current modeling efforts have insufficiently addressed model output uncertainties and their sensitivity to external (e.g., solar EUV, auroral precipitation) and internal parameters (e.g., reaction rates, cross sections). The recent NSF Space Weather Quantification of Uncertainties program is aimed at creating space weather models with quantifiable predictive capabilities through advancing modeling approaches and the proper treatment of observational inputs.

Some instruments provide inherent quantification of uncertainty on the retrieved state parameters, but often the error analysis is ad hoc. Results are often reported without appropriate treatment of either measurement/retrieval uncertainty or systematic bias associated with physical assumptions of the retrieval approach. The need for robust uncertainty quantification (UQ) has been established in the applications community (e.g., space weather forecasting), but UQ is just as important for scientific understanding of ITM system variability.

Priority Science Goal 3, Objective 3.3: Quantify the Most Salient Factors Governing the Global ITM Response During and Following Geomagnetic Activity

The ITM response to geomagnetic storms has been a topic of study for several decades, and substantial recent progress in understanding individual mechanisms has been made by missions such as TIMED, GOLD, and ICON,

as well as by ground-based assets such as IS radars, LiDARs, and optical observations. Many competing drivers contribute to the ITM response to magnetic storms, including neutral winds, electric fields, energetic particle precipitation, neutral temperature, and composition (O, N2, and NO) changes. However, the relative importance of various controlling mechanisms of the system behavior is not well established. Quantifying the relative importance of these factors is crucial to understanding the storm-induced changes in the ITM system.

For example, both ICON and GOLD satellite observations have revealed large effects in multiple ionospheric and thermospheric parameters, which exhibit significant spatial structure even at midlatitudes, following even very weak storms (see Figure D-14). The patchy nature of the midlatitude thermosphere composition response to a storm illustrates why predicting magnetic storm effects is difficult and why global-scale sensing is so important. Progress has been hampered by insufficient temporal and spatial resolution of the observations. Numerical advances such as whole geospace and assimilative models are developing quickly and will be excellent tools for further progress when combined with appropriate data sources.

A major impediment to a better understanding of ITM behavior during and after a storm event is that they rarely have similar characteristics. The lack of good storm indices and the necessary averaging of the thermosphere response data help explain why the Naval Research Laboratory Mass Spectrometer and IS Radar Exosphere (NRLMSISE-00) empirical model is much less reliable during disturbed times than during quiet times. Likewise, quantifying the auroral energy input with its high temporal and spatial variability is a key problem for physics-based models. Another uncertainty is the vibrational distribution of N2, which has a major effect on the ionosphere density by increasing the O+ loss rate during elevated levels of magnetic and solar activity. Although the vibrational state of N2 can be well modeled, its calculation is very computer intensive and has not yet been included in global models. This can lead to overestimation of the F-region electron density by a factor of 2. Resolving these difficulties to further advance modeling capability needs to incorporate simultaneous images of both north and south auroral regions, coupled with in situ measurements and comprehensive ground-based measurements in both hemispheres. Such multielement analysis approaches have proved quite productive in the recent past for similar challenges; for example, a major improvement in storm modeling was achieved by including conductance patterns derived from the Polar UVI auroral images together with ground magnetic perturbations that include mesoscale structure.

SOURCE: Cai et al. (2020).

Priority Science Goal 3, Objective 3.4: Quantify the Origin of Interhemispheric Asymmetries in Geospace and Their Effects on the ITM System

Interhemispheric asymmetry in current circuits, particle precipitation, and electron density is now understood to be a common feature of global and mesoscale ITM structure and variability, and Figure D-15 illustrates an example of this phenomenon. Conjugate asymmetries are believed to arise from both intrinsic ITM factors (e.g., the geomagnetic field, ionospheric conductivity, atmospheric waves) and external factors (e.g., the solar wind and magnetospheric forcing). Investigating the nature and origin of interhemispheric asymmetries in global and mesoscale structures offers critical tests of our understanding of the ITM system response to competing drivers.

The magnetosphere–ionosphere–thermosphere–mesosphere system regulates Earth’s global current circuit, highlighting the critical importance of ionospheric conductivity. A number of ITM processes that govern structure in conductivity (Joule heating, transport, precipitation, composition) compete to regulate, for instance, the substorm cycle for different situations. How the global current circuit influences ITM system behavior, and how the ITM system regulates the global current circuit, are the net results of the balance of a number of competing processes. A complete understanding of this ITM system regulation will be valuable through its ability to explain and predict the effects of interhemispheric asymmetries (and symmetries/magnetic conjugacy) in energetic particle precipitation, currents, and flows.

Many existing resources have contributed to the understanding of these questions so far. Ad hoc conjunctions of ground-based auroral imagery arrays (THEMIS-GBO) with satellite data (ESA-Swarm, DMSP) and radar data (PFISR, RISR, EISCAT) have supported investigations of storm-time ITM system dynamics in high-latitude regions, although primarily confined to the northern hemisphere. Meanwhile, magnetometer chains across Canada, Alaska, and Scandinavia provide models with continuous and distributed data constraints needed for a variety of studies.

Directed research programs have also focused on some of these questions. For example, NSF CEDAR Grand Challenge studies have included “Interhemispheric Asymmetries (IHA) and Impact on the Global I-T System” (2023), “Multi-Scale I-T System Dynamics” (2021), and “The High Latitude Geospace System” (2016). Recently, assimilative tools such as LOMPE allow the aggregation of heterogeneous data sets into maps of information that can be used to drive models. Larger-scale similar tools such as Assimilative Mapping of Ionosphere Electrodynamics (AMIE) have significantly contributed to these studies.