The Next Decade of Discovery in Solar and Space Physics: Exploring and Safeguarding Humanity's Home in Space (2025)

Chapter: Appendix B: Report of the Panel on the Physics of the Sun and Heliosphere

B

Report of the Panel on the Physics of the Sun and Heliosphere

Solar and heliospheric physics covers a vast domain, extending from the core of the Sun to the boundary between the heliosphere and interstellar space. This field aims to understand how the Sun generates energy, how it powers the solar dynamo that creates and sustains a complex and highly variable magnetic field, and how it forms and upholds the heliosphere, the farthest reaches of the Sun’s atmosphere. It seeks to unravel what drives solar activity, how the solar wind is formed and evolves on its journey from the corona to the heliopause (HP), and how the heliosphere interacts with the interstellar medium.

There are important practical aspects to this field. The heliosphere is humanity’s home in the galaxy, and the dynamic interactions it contains have consequences for a society that is reliant on space-based and ground-based technologies impacted by the sudden and violent energy releases occurring throughout the space environment. Understanding these interactions is essential for protecting life on Earth and for safeguarding humanity as it expands to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

B.1 STATE OF THE FIELD

The previous decade has seen many new discoveries and considerable advances in the basic understanding of solar and heliospheric physics. Tasked with identifying the highest-priority science goals (PSGs) related to the Sun, the heliosphere, the very local interstellar medium, and pertinent emerging interdisciplinary opportunities, the Panel on the Physics of the Sun and Heliosphere (SHP) considered the wealth of significant accomplishments from the past decade to guide the next. Here, the panel lists several of these achievements, organized by the overarching PSGs (not in prioritized order)—that will guide solar and heliospheric science in the coming years. Each section lists several key new discoveries as well as important science questions that have arisen from these and other recent revelations.

B.1.1 How Does the Sun Maintain Its Magnetic Activity Globally from Pole to Pole?

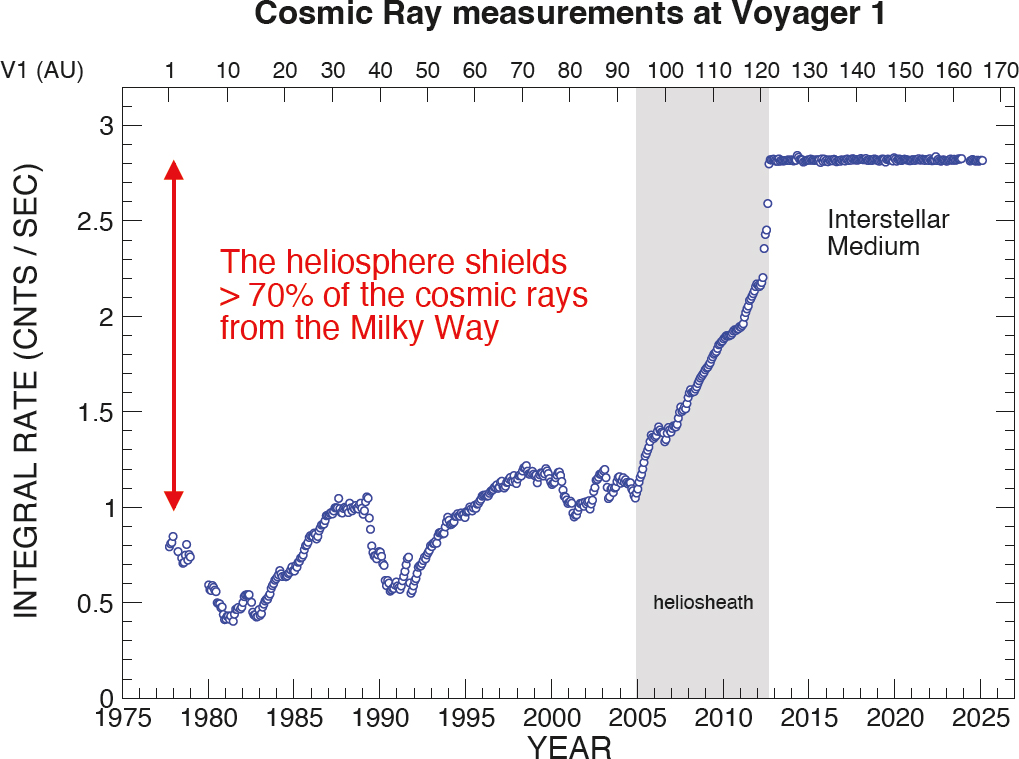

The previous decade included a much weaker sunspot cycle, with a considerably lower mean sunspot number, than the two that preceded it. This followed a period of very weak solar activity and a long, deep sunspot minimum. The solar wind flux and magnetic field were considerably weaker during the previous solar minimum, while the flux of galactic cosmic rays reached the highest on record. New discoveries continue to be made from operational

missions within the Heliophysics Systems Observatory (HSO) and solar ground-based facilities—now including the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope, the most advanced solar telescope in the world. The past decade has also seen great progress in solar dynamo modeling, which has always been a challenging problem because the dynamo is inherently a multi-spatial-scale system. The “mean field model,” capturing physics of small scales via parametrizations, and full three-dimensional (3D) models, targeting explicit dynamics over a wider range of scales, are gradually converging toward a unified understanding of the dynamo that will likely come to fruition in the next decade when the physics of polar regions will be addressed.

Highlights of additional major science advancements from the past decade include the following:

- Numerical modeling of the solar dynamo: 3D global magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) simulations are now producing results that are relevant to the solar case, including the reversal of the solar field polarity (toroidal field reversals) and key aspects of the well-known butterfly diagram. Mean field models now well represent important aspects of the dynamo process such as magnetic buoyancy, nonlinear “quenching” of turbulent diffusion, and kinetic helicity, which result in realistic torsional oscillation patterns seen in helioseismology observations.

- Helioseismic measurements of solar rotation and meridional circulation: A major advancement of helioseismology has been the accurate measurement of solar rotation as a function of both latitude and radius in the convection zone, tachocline, and interior. While helioseismic techniques cannot measure magnetic fields directly, recent observational advances in solar rotation and meridional flow measurements have shown that the fields’ amplitudes and variations are clearly influencing velocity dynamics, allowing us to probe the structure and strength of subsurface solar magnetic fields.

- Discovery of Rossby waves: One of the major, unanticipated discoveries of the past decade is the detection of Rossby waves in the Sun (Figure B-1). These inertial waves, first detected in Earth’s atmosphere, occur in thin spherical shells owing to the latitude variation of the Coriolis forces. Terrestrial Rossby waves interact with the mean zonal flow to produce “jet streams” that steer the daily weather. Analogously, solar Rossby waves can interact with solar differential rotation and toroidal magnetic fields to affect the distribution of active regions and enhance bursts of solar activity.

Some of the key questions remaining in this field include the following: Does the meridional flow go all the way to the pole or do counter-cells occur? At what latitude do the polar fields reverse? What is the nature of polar vortices? What is the temperature difference between the poles and the equator? This topic will be explored further in Section B.2.1.

B.1.2 How Do the Sun’s Magnetic Fields and Radiation Environments Connect Throughout the Heliosphere?

The past decade has seen a significant increase in the understanding of the physics of the solar chromosphere, corona, and solar wind. Parker Solar Probe (PSP) was launched in 2018 and has markedly advanced the understanding of how the solar magnetic field is connected with the inner heliosphere. The seamless coverage of spectral diagnostics from the photosphere into the low corona—by the Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) satellite and a host of complementary, high-resolution, ground- and space-instruments—now allows researchers to precisely investigate the connectivity between solar surface drivers and phenomena observed in the upper atmosphere. This effort is supported by increasingly sophisticated numerical models of the solar atmosphere that now include critical nonequilibrium effects such as time-dependent ionization and ion-neutral interactions, which greatly affect the structure of the chromosphere and transition region (TR). Some of these models are starting to reproduce quintessential chromospheric features such as spicules or fibrils.

Highlights of additional major science advancements from the past decade include the following:

- First advances in understanding the slow solar wind: Periodic density and magnetic structures are commonly observed in the slow solar wind, indicating a source related to intermittent plasma release associated with

SOURCE: Dikpati and McIntosh (2020), https://doi.org/10.1029/2018SW002109. CC BY 4.0.

- interchange reconnection. Pseudostreamers are a prime location for interchange reconnection, with observed structure size scales that are consistent with those found in the periodic structures. Models of the solar coronal magnetic field driven by photospheric flows show ubiquitous interchange reconnection along coronal hole boundaries between open and closed fields, which is likely the dominant process capable of explaining key observations of the slow solar wind, including more variability, and enhanced ionic and elemental composition.

- Proving the existence of nonthermal particles in coronal nano-flares: It has long been thought that quiescent active regions are heated primarily by so-called nanoflares, episodes of small-scale magnetic reconnection leading to nonthermal accelerated particles and impulsive heating of the coronal plasma, but there has been no direct proof. IRIS ultraviolet (UV) spectroscopy of the chromospheric and TR response to small, rapid coronal heating events has revealed that for a large fraction of them the observed velocity pattern can be explained only by a population of coronal nonthermal electrons, dissipating their energy in the lower atmosphere. This pattern has been confirmed by highly sensitive hard X-ray (HXR) observations with the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR) astrophysics satellite, which have unambiguously proven the presence of nonthermal accelerated particles in small-scale events.

- Discovery of a highly structured solar wind magnetic field near the Sun and magnetic “switchbacks”: PSP observed complex magnetic structure in the solar wind, including the existence of “magnetic switchbacks” (Figure B-2). Beyond a few solar radii, the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) was expected to be nearly radial; however, PSP found it to contain numerous structures in which the field reverses direction. Researchers have connected the timing of the occurrence of switchbacks to variations in the solar wind velocity and have identified their solar source, providing strong evidence that interchange reconnection is the likely origin of the fast solar wind.

- Measuring the magnetic wave origin of First Ionization Potential (FIP) bias in active regions: Exciting results, obtained by combining coronal spectroscopy and first observations of chromospheric magnetic field temporal variations, have recently demonstrated a likely origin of the “FIP bias” (the overabundance of elements with low FIP as measured in coronal plasma). Its spatial distribution observationally links to sites of strong Alfvénic perturbations in the chromosphere, providing strong evidence that the fractionation process producing the FIP bias is powered by the conversion of magnetic waves in the chromosphere.

Some of the key questions remaining in this field include the following: How does the lack of far-side and polar observations of the Sun impact the ability to accurately describe global solar wind, coronal mass ejection (CME), and energetic particle propagation? What role do interchange reconnection and waves and turbulence play in generating the solar wind, and how do they imprint on the fast and slow solar wind? What is the role of

SOURCE: S. Bale, S. Badman, J. Bonnell, et al., 2019, “Highly Structured Slow Solar Wind Emerging from an Equatorial Coronal Hole,” Nature 576:237–242, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1818-7, reproduced with permission from SNCSC.

the chromospheric magnetic field in shaping the corona and solar wind? This topic will be explored further in Section B.2.2.

B.1.3 How Do Solar Explosions Unleash Their Energy Throughout the Heliosphere?

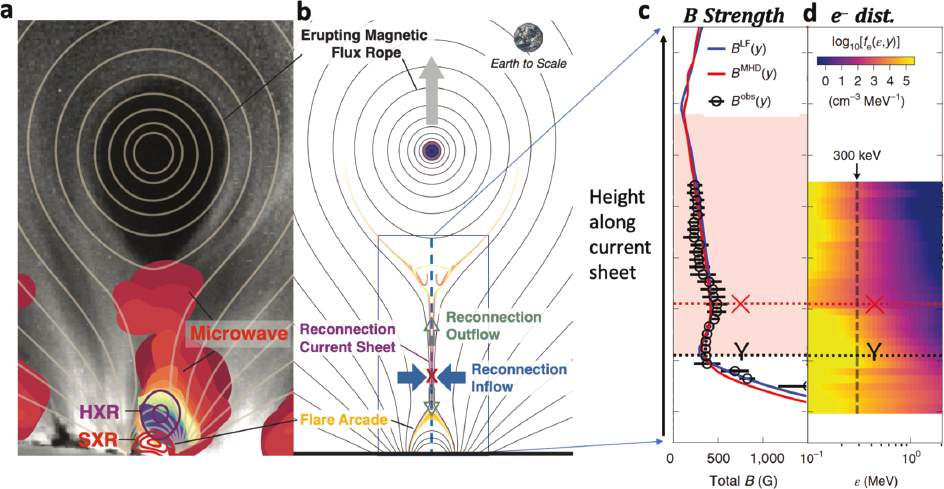

The past decade saw a key breakthrough in solar-flare science: the direct mapping of magnetic fields, which power these explosive phenomena, near the acceleration region through the use of the radio astronomical telescope EOVSA (Expanded Owens Valley Solar Array) with microwave imaging spectroscopy (Figure B-3). Prior to this breakthrough, this magnetic energy release could only be inferred indirectly, by comparing the pre- and post-flare photospheric magnetic fields or tracking the motion/evolution of plasma-confining extreme ultraviolet (EUV)/X-ray loops or flare footpoints/ribbons. Multispacecraft observations have also made pivotal advances. The twin Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) spacecraft combined with the Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE), for example, revealed that solar energetic particles (SEPs) are dispersed in longitude far more than was expected. CMEs are a key driver of space weather, and understanding how they are released and propagate in the heliosphere endures as a major research thrust. Tests of the traditional CME structure paradigm have become considerably more stringent in the past decade, as analyses increasingly utilize data from multiple spacecraft to study structure and kinematics, from PSP showing particles accelerating toward the Sun from the inner heliosphere to Voyager measuring the passage of CMEs in the outer heliosphere.

SOURCES: (Left and right) Adapted from B. Chen, C. Shen, D.E. Gary, et al., 2020, “Measurement of Magnetic Field and Relativistic Electrons Along a Solar Flare Current Sheet,” Nature Astronomy 4:1140–1147, reproduced with permission from SNCSC; (Middle) Committee created.

Highlights of additional major science advancements from the past decade include the following:

- First observations of SEPs backstreaming from distant co-rotating interaction regions: PSP has provided the first measurements of energetic particles from global solar wind stream interaction regions, and the particles are seen to be moving toward the Sun. The acceleration site is far from the spacecraft, suggesting very efficient transport in the interplanetary magnetic field with a long mean-free path.

- New multispacecraft observations of CME structure: In 2014, a CME was observed by no fewer than 10 National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and European Space Agency (ESA) spacecraft, from the Sun all the way out to Voyager 2 in the outer heliosphere. PSP has provided the first close-up images of transients while they are still near the Sun. These observations are opening new questions about CME structure and evolution.

- Discovery of large numbers of coronal and precipitating electrons in solar flares: Researchers discovered that coronal sources in certain solar flares had extremely high nonthermal density. The inferred energy flux of electrons precipitating into the solar atmosphere during the impulsive phase of certain solar flares is also far greater than previously expected, as extreme as ~1013 erg s−1 cm−2. This value is far outside the realm of the basic assumptions in HXR modeling that has been ubiquitously used for the past 50 years.

- Discovery of SEPs dispersed widely in helio-longitude: SEPs from a compact source on the Sun were seen by multiple separate spacecraft near 1 AU and were quite widely separated in longitude. This separation was unexpected because it was thought that SEPs were mostly guided by the Parker spiral magnetic field, but these results indicate that SEPs undergo considerable cross-field transport. It remains unclear how and where this efficient transport occurs. In addition, for energetic electron events associated with HXR flares, it has been found that less than 1 percent of the total energetic electron population managed to escape to interplanetary space, which further underpins the importance of understanding the transport processes from near the Sun and into interplanetary space.

Some of the key questions remaining in this field include the following: What is responsible for the extremely efficient particle acceleration within solar flares? How are SEPs transported into the heliosphere in both longitude and latitude? What causes the wide range of variability in the composition of SEPs? How do CMEs evolve from the Sun to 1 AU? This topic will be explored further in Section B.2.3.

B.1.4 How Is Our Home in the Galaxy Sustained by the Sun and Its Interaction with the Local Interstellar Medium?

The past decade has been a period of tremendous progress in the science of the outer heliosphere. The Voyagers, now making the first in situ measurements of the local interstellar medium (LISM), continue their epic journeys. Each has now crossed the HP, the heliospheric boundary separating plasma of solar origin from that of the LISM. They discovered unusual variations in galactic cosmic rays (GCRs)—particulate radiation mostly produced in supernovae remnants—that permeate the galaxy and enter the solar system where they are modulated by the heliosphere. The Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) continues to probe the global heliosphere, including an enigmatic enhancement of energetic neutral atoms (ENAs) coming from the outer heliosphere (the “IBEX Ribbon”). New Horizons contributes through the first outer heliosphere measurements of pickup ions (PUIs), produced when an interstellar atom is ionized and representing a nonthermal population in the solar wind, as well as low-energy ions.

Highlights of additional major science advancements from the past decade include the following:

- Voyagers crossing of the HP: The Voyager 1 HP crossing in 2012, at a heliocentric distance of 121 AU, was identified by the detection of plasma waves. The local plasma density was determined to be 0.08 cm−3, close to the predicted value. Voyager 2 crossed the HP in 2018 at a distance of 119 AU from the Sun. Voyager 1 does not have a functioning plasma instrument; and while Voyager 2 does, it has not directly measured the LISM plasma. The HP crossing was also identified by the complete disappearance of anomalous cosmic rays (ACRs), a type of cosmic ray produced in the heliosphere and most likely accelerated at the solar

- wind termination shock (TS). The Voyagers are now measuring the GCR spectrum in interstellar space, unmodulated by the heliosphere.

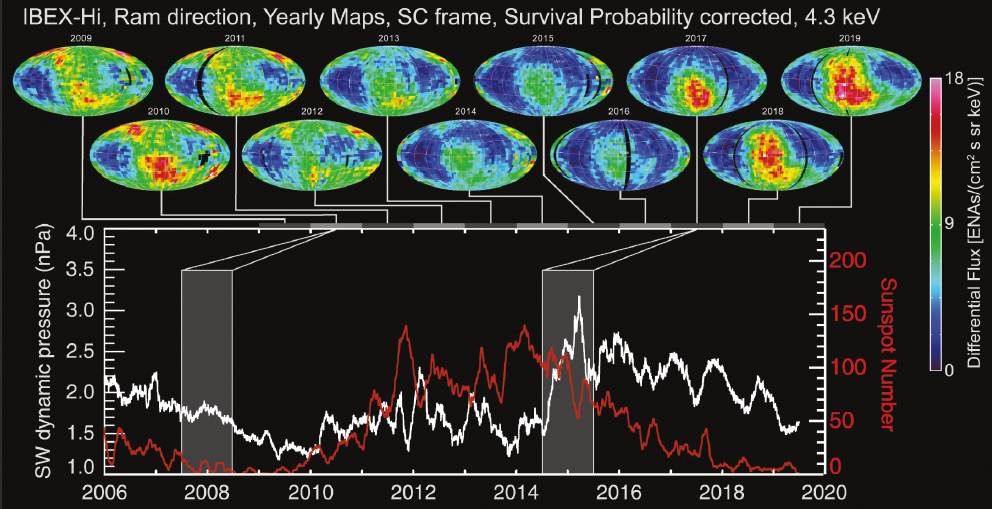

- Proof that the heliosphere responds to solar-cycle variations: IBEX ENA maps collected over the past decade have revealed a sudden and intense heating of the heliosheath resulting from a large increase in dynamic pressure of the solar wind after a long period of weak solar activity, convincingly demonstrating the heliospheric response to changes in solar activity (Figure B-4). The IBEX Ribbon as well has changed with time on the scale of years, reflecting changes from the solar cycle.

- The IBEX Ribbon originates in a region of trapped solar wind beyond the heliopause: The IBEX Ribbon is a feature that appears in ENA maps of the sky that is oriented along the locus of points where outward lines-of-sight from the Sun are perpendicular to the interstellar magnetic field (ISMF) draped around the heliosphere. Numerous theories have been proposed in the past decade to explain the origin of the Ribbon. A preponderance of evidence now suggests the Ribbon results from a multistep “secondary ENA” process whereby outgoing neutralized solar wind travels unimpeded beyond the heliopause is then reionized and captured by the draped ISMF, and then reneutralized several years later, producing a population of secondary ENAs, some of which return to the inner heliosphere and observed as the Ribbon. Research is ongoing to explain the details of exactly how the ion population is captured and retained.

- First measurements of the magnetic field in the LISM: The magnetic field increased at the HP crossing, but, surprisingly, its direction only changed slightly, counter to predictions. The field strength in the LISM measured by Voyager 1 was ~4.6 μG and was later observed to be somewhat higher by Voyager 2, at ~5.8 μG. This implies that the magnetic pressure is some 40 percent different at the two separate

SOURCE: D.J. McComas, M. Bzowski, M.A. Dayeh, et al., 2020, “Solar Cycle of Imaging the Global Heliosphere: Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) Observations from 2009–2019,” Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 248(2):26, https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4365/ab8dc2. © AAS. Reproduced with permission.

- crossing points, suggesting an asymmetry in the way in which the LISM magnetic field drapes around the heliosphere. The field strength of ~4.6–5.8 μG is larger than predictions, but within the range of expected variations owing to LISM turbulence.

- Discovery of shock-like plasma disturbances in the LISM: The plasma waves that led to the discovery that Voyager 1 had crossed the HP have been observed at other times as well, deeper into the LISM. These waves resemble shock-like structures and are certainly large-scale global disturbances passing the spacecraft, much thicker than shocks observed inside the heliosphere for many years.

Some of the key questions remaining in this field include the following: What is the geometric shape of the heliosphere? How are GCRs modulated across the HP and within the heliosheath? What is the PUI distribution across the termination shock and within the heliosheath? This topic will be explored further in Section B.2.4.

The panel considered the prodigious achievements of the Sun and heliosphere community, the valuable inputs provided through 187 contributed community input papers, and the space- and ground-based capabilities available now and in the near future, to assess the current state of the field. This assessment was used to identify the science goals moving forward for the community, including near-term PSGs, a longer-range goal (LRG), and emerging opportunities (EOs). The panel identified four PSGs, each described in Section B.2. The LRG is detailed in Section B.3. Two EOs are introduced in Section B.4. The current and envisioned guiding research activities, including enabling space-based mission concepts and ground-based facilities for the next decade, are described at length in Section B.5. Included in this last section are considerations addressing broader community needs and enabling opportunities.

B.2 PRIORITY SCIENCE GOALS

The four Sun and heliosphere PSGs are described in this section along with a description of the research and analysis development programs supporting these activities. For each goal, the panel lays the groundwork for the relevance and importance of the science and describes the current research activities for each objective. The panel identifies prevalent current and planned observational resources that are available, both space- and ground-based, and outlines the state of theory, modeling, and simulations relevant to addressing these goals. Last, the panel discusses how these goals are motivated by the current state of the field and describes their contribution to system-level science.

B.2.1 Priority Science Goal 1

Since the discovery that the solar photosphere is covered by magnetic fields in 1908, scientists have come to realize that the overwhelming majority of solar variability is driven by magnetism. This variability happens over decadal timescales in the form of the solar magnetic cycle, quasi-annual/quasi-biennial timescales of solar activity in the form of solar “seasons,” weeks-to-months timescales in the form of active regions emergence and decay, and minutes-to-hours timescales in the form of flares and CMEs. The question of how the Sun maintains its magnetic activity globally has pervaded all previous decadal surveys in different guises, and there has been substantial progress in the ability to observe and simulate all of these different timescales. However, owing to lack of knowledge of flows and fields in the polar regions and greater depths (Figure B-5), the understanding of the solar dynamo and activity cycle and their connections to the evolution of the 3D corona remain crucially incomplete.

While global measures of meridional circulation as a function of latitude and depth have continued in the past decade, focus has also extended on determining the role of local active regions’ flows in modulating the global meridional circulation as a function of latitude and time. Long-term data collection efforts have helped in deriving the variation in differential rotation and variation in the tachocline properties as a function of the solar cycle. Progress has been made in inferring the emergence and existence of active regions on the far-side of the Sun. One of the newest discoveries of helioseismology over the past decade has been detecting Rossby waves and other inertial waves in low latitudes. How the flows and waves behave at the polar latitudes and globally around the whole Sun and whether longitude dependence exists in the meridional circulation are not known yet.

SOURCE: Nandy et al. (2023), https://doi.org/10.3847/25c2cfeb.1160b0ef. CC BY 4.0.

PSG 1 (Table B-1) captures the community’s need to push forward the understanding of what makes the Sun a star, with an emphasis on polar measurements. The objectives highlight the critical role that solar plasma flows and magnetic fields play in driving all observed solar phenomena from the photosphere to the edge of the heliosphere and stress that the solar poles remain outside of observational capabilities, thus representing one of the final observational frontiers in solar physics.

Current Research Activity

Priority Science Goal 1, Objective 1.a

The solar poles seed the magnetic fields that generate and shape future solar cycles. However, there is limited understanding on where and how the polar fields connect to dynamo generation across the whole convection zone. Achieving this objective requires direct observations of the polar fields, including information about the subduction mechanisms that connect polar fields and toroidal belts (such as meridional circulation). It also requires a better understanding of the polar differential rotation, including the possible existence of a polar vortex and the thickness of the tachocline at the poles (Figure B-6).

TABLE B-1 Sun and Heliosphere Priority Science Goal (PSG) 1 and Objectives

| PSG 1 (of 4) | Objectives |

|---|---|

| How does the Sun maintain its magnetic activity globally from pole to pole? |

|

SOURCE: Featherstone et al. (2023), https://doi.org/10.3847/25c2cfeb.240cbaca. CC BY 4.0.

Priority Science Goal, Objective 1.b

Magnetic fields, generated by the solar dynamo, manifest at the surface in the form of active regions. Extensive efforts have been made to model the movement of magnetic flux from the dynamo layers to the surface by convective instability and magnetic buoyancy effects. Their emergence and evolution drive the evolution of coronal structure and energetics. To accomplish this objective, it is necessary first to understand what processes govern magnetic flux emergence through the surface and their specific latitude–longitude distribution, and then to integrate modeling efforts combining flux emergence from dynamo layers to the surface with the evolution of the global corona. This work needs to be combined with a sustained effort to measure magnetic fields directly in the chromosphere and corona, as well as to expand observational capabilities to observe the full solar surface, with multiviewpoint observations to jointly build a comprehensive picture of the entire process.

Priority Science Goal, Objective 1.c

While global flows, like differential rotation and meridional circulation (two major ingredients of solar dynamo models), have been measured successfully at the surface up to a latitude of about 60 degrees through helioseismic techniques, knowledge about their profiles in latitude, longitude, and depth is still lacking. Solar Rossby waves and inertial oscillations were detected within the past decade and have been shown to nonlinearly interact with mean (longitude-averaged) flows and magnetic fields in a complex fashion, which may explain the observed nonaxisymmetric (longitude-dependent) distribution of surface active regions. This nonlinearity is just one example of the key questions raised concerning the interaction between these waves and oscillations that need to be explored in the next decade.

A topmost priority in the next decade is to refine helioseismic techniques to enable new important measurements. These techniques include the ability to measure the thickness of the tachocline as a function of latitude, to determine whether global flows have longitudinal structures and to distinguish between inertial oscillations and large-scale convective motions as a function of convection zone depth. This capability will allow us to finally resolve the long-standing inconsistencies between helioseismic observations of convective velocities and global convective model-outputs.

Priority Science Goal, Objective 1.d

Every aspect of the way the Sun drives variability in the solar system is connected to the solar cycle via active region emergence and decay. Achieving this objective thus requires the coordination between surface and helioseismic measurements to infer changes in the subsurface toroidal field. Also needed is an understanding of how changes in large-scale solar flows determine subsequent changes at the surface and in the atmosphere. It is imperative to modernize historical data such that they can be combined with current data to produce a long-term

SOURCE: A. Muñoz-Jaramillo and J.M. Vaquero, 2019, “Visualization of the Challenges and Limitations of the Long-Term Sunspot Number Record,” Nature Astronomy 3:205–211, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-018-0638-2, Springer Nature.

homogeneous observational baseline (Figure B-7), including as many sunspot cycles’ worth of observations of magnetic fields, plage, coronal bright points, and coronal structures as possible.

Observational Resources

To study the Sun’s internal structure, SDO’s Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI) and the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory’s (SOHO’s) Michelson Doppler Imager (MDI) (MDI until 2011) make full-disk measurements from which differential rotation, meridional circulation, and Rossby waves are inferred from frequency shifts in acoustic modes of the Sun. These measurements are also used to study domains from the Sun’s outer atmosphere to the solar wind, spanning the spatial progression from small-scale local dynamics to global dynamics in the form of synoptic maps. Although SDO/HMI observations of the evolution of flows and magnetic fields inform all four objectives, their range is limited to latitude below 60 degrees and to the visible disk of the Sun.

The ground-based instruments of the Global Oscillation Network Group (GONG), a network of six identical observatories distributed all over the globe, guarantee a continuous coverage of the Sun, providing measurements similar to SDO/HMI (although at a lower spatial resolution). The Sun’s internal oscillations, caused by sound waves that travel through its interior, are studied to learn about the physical properties of the Sun’s interior, such as its temperature, pressure, composition, rotation, meridional circulation, and inertial waves. The GONG high-resolution spectrographs provide full-disk, high-cadence Doppler shift maps caused by these oscillations for helioseismology studies. GONG measurements of the line-of-sight photospheric magnetic field over the full disk, at a ~10 min cadence, are used to produce extrapolated models of the 3D coronal and heliospheric magnetic field.

Like all full-disk instruments observing from the ecliptic, GONG has latitudinal coverage for flows and fields up to roughly 60 degrees north and south. Hence, GONG can also contribute to achieve all four objectives. Great benefit has been achieved by having HMI and GONG operating simultaneously using different instrumental techniques allowing mutual validation of helioseismic results. While the use of helioseismic holography techniques has made far-side imaging possible from these instruments’ data, in order to make further progress in the next decade, observations from 65 degrees latitude up to the poles as well as simultaneous views of 360 degrees longitude are necessary.

The Solar Orbiter (SO) mission includes a magnetograph (Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager [PHI]) that can measure complex near-surface flows, meridional flows, and differential rotation at the surface, up to 65 degrees latitude and an EUV imager (EUI) that will measure and characterize plasma flows that transport magnetic fields. The out-of-the-ecliptic phase of SO, beginning in 2027, would provide some information about polar regions and hence new constraints for solar dynamo models, but the observations will only cover a few weeks per year. In 2030, SO is set to reach an orbital inclination of 34 degrees, which will give a better view of the poles but yet will not allow for the multimonth monitoring of the polar flows needed to be detected by helioseismology, and hence comprehensive understanding of dynamo and polar field evolution will remain incomplete.

The Hinode mission’s Solar Optical Telescope (SOT) infers the Sun’s magnetic fields up to 70 degrees latitude to study what drives solar eruptions and powers the solar atmosphere. SOT measures Zeeman/Stokes parameters to obtain both strength and direction of the magnetic fields associated with the eruptions. This instrument has been successfully resolving polar fields for more than a solar cycle up to about 70 degrees (beyond which the spatial resolution decreases owing to foreshortening) and will remain the best source of polar field measurements until a truly polar mission is implemented. Complementary Hinode instruments produce X-ray images and EUV spectroscopy to diagnose temperature and pressure in the corona above the photospheric fields.

The Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere (PUNCH) is an upcoming (~2025) Small Explorer (SMEX) mission developed to understand how the mass and energy in the Sun’s corona form the solar wind and globally evolve. PUNCH consists of four synchronized Earth-orbiting satellites, each containing four instruments, with the goal of producing a continuous picture of the whole inner heliosphere.

The Upgraded Coronal Multi-channel Polarimeter (UCoMP) is a ground-based 20 cm aperture Lyot coronagraph with a Stokes polarimeter. It can image the intensity, linear Stokes polarization, Doppler shift, and line width across coronal emission lines in the visible and near-infrared (IR), up to 2 R⊙ (1.56 R⊙ in the polar direction). Joint analysis of different emission lines provides information about global coronal variations of density and temperature as well as dynamics and magnetic field direction in the plane of the sky. Recent studies on the propagation of waves in the low corona have provided estimates of the magnetic field strength in defined regions.

The Kodaikanal Solar Observatory (KoSO) has one of the world’s longest-term digitized full-disk solar data archives in white light (1904–2017), Ca II K (1904–2007), and H-α (1912–2007) enabling analysis of solar flows, meridional circulation, and differential rotation as well as the evolutionary patterns of polar faculae and active regions. The images have been recorded with optical telescopes, including a 15-cm-aperture photoheliograph and twin 6-cm-diameter spectroheliographs, which provide the full-disk photographs of the Sun in K-α and H-α. Mount Wilson Observatory has similar records.

Theory, Modeling, and Simulations

Significant theoretical effort to understand how the Sun maintains its magnetic activity globally has enabled us make substantial progress during the past decade—thanks to significant improvement to models of the solar magnetic field through several NASA programs: HSR (Heliophysics Supporting Research), HTMS (Heliophysics Theory, Modeling, and Simulations), LWS-FST (Living With a Star Focus Science Topic), LWS Strategic Capability, and NASA Diversify, Realize, Integrate, Venture, Educate (DRIVE) Science Centers, as well as National Science Foundation (NSF) programs (e.g., Next-Generation Software for Data-driven Models of Space Weather with Quantified Uncertainties [SWQU], Advancing National Space Weather Expertise and Research toward Societal Resilience [ANSWERS], and Science and Technology Centers [STC]), and an increased level of computational power.

While scientists are still not close to a global turbulent MHD simulation of the solar interior, surface, and atmosphere that can simulate decades of evolution, all the different models used to understand solar magnetism have clearly begun to overlap in the relevant spatial and temporal scales they simulate, as well as reproducing solar-like behavior with a fidelity that was not possible 10 years ago.

Surface flux transport simulations (simulations of the surface radial magnetic field, driven by prescribed flux emergence and flows) have transitioned from modeling turbulent convection as a diffusive process to the inclusion of realistic convective turbulent flows. This advancement in modeling techniques, coupled with better means

for assimilating solar magnetograms (and far-side EUV images), has resulted in simulations that bear an uncanny resemblance to real observations and are used to fill observational gaps on the solar far-side.

High-resolution turbulent convective simulations (full 3D MHD simulations of wedges of the solar convection zone encompassing the near surface layers and photosphere) now involve significantly larger wedges and higher resolution and coupling of subsurface convection with simulations of the lower corona. This improvement has enabled the simulation of a wide range of solar magnetic phenomena (e.g., quiet Sun, sunspots, and flux emergence) as well as that of surface solar observables that are almost impossible to distinguish from real observations.

Global anelastic simulations (3D MHD simulations of the part of the global convection zone in which the global dynamo operates) have attained solar-like oscillatory behavior and routinely produce solar-like cycles. This realistic reproduction has enabled the systematic exploration of simulated stars with solar-like cyclic behavior, which in turn has sharpened the focus on the importance of rotation and convection in the establishment of solar global flows like differential rotation (including or not a tachocline), meridional circulation, and the roles they play in the global dynamo.

Kinematic mean-field dynamo models (simulations of the mean solar magnetic field that abstract the turbulence velocity field through an electromotive force and turbulent diffusion) have been generalized from two-dimensional (2D) to 3D models. This advance has led to synergies between mean-field models that can separate small-scale turbulence and large-scale dynamics along with full 3D MHD simulations. Such a step forward has enabled breakthroughs by simulating buoyancy instability-driven emergences of bipolar magnetic regions, torsional oscillation patterns, and extended solar cycle. What is still lacking is input of physical processes happening in the polar regions as well as comparisons between model-outputs and observations there.

Atmospheric Rossby waves (the large meandering patterns occurring in the atmospheres of rotating celestial bodies owing to variation of the Coriolis force with latitude and/or differential heating from the Sun) have been used for terrestrial weather prediction for several decades. By contrast, solar Rossby waves were an unanticipated observational discovery made only in the middle of the past decade. Since then, the development of solar Rossby waves theory and modeling as well as further observational evidence grew quickly, and their nonlinear dynamics have given hints on the roles Rossby waves play in determining the spatio-temporal distribution of active regions. Nevertheless, it is not known for sure yet where they are generated and exactly how they manifest at the surface and solar atmosphere, and so it is necessary to further develop modeling capability. What roles do Rossby waves and other inertial waves play in short-term, decadal, and long-term solar variability, and thus in space weather and climate? To how high a latitude do Rossby waves reach, and what are their longitude patterns around the whole Sun?

The NASA DRIVE Science Center “COFFIES,” led by Stanford University, is producing cutting-edge global models for studying the “Consequences Of Fields and Flows in the Interior and Exterior of the Sun,” with an internationally collaborative team of 85 researchers to expand the understanding of the Sun to simulate where and when active regions emerge and to develop the capability to forecast activity cycles and solar magnetic variability. In parallel, a non-U.S. “Whole Sun Project,” funded by the European Research Council, is a collaborative effort among European universities and institutes to develop a complete Sun model to determine over the next 6 years how the interior magnetic field is generated and how it creates sunspots on its surface and eruptions in its highly stratified atmosphere.

Motivation for the Goal

At the beginning of the past decade, the researchers in this field still had an incomplete understanding the processes that determine the global distribution of magnetic fields, their cyclic evolution, and the spatio-temporal patterns of polar fields, all of which are necessary to understand and predict the next solar activity cycle. Synoptic maps derived from through observation from ground-based and space-borne magnetograms, such as GONG, SDO/HMI, successfully provided observations of photospheric magnetism and global flows (differential rotation and meridional circulation) up to about 60 degrees, on both front and back sides, as well as how active region inflow cells modulate to create time-variation in meridional flow. Differential rotation is also accurately determined up to 60 degrees, as well as the global coronal structure, but it is not known yet whether (1) the polar regions spin up or spin down, with associated vortices like Jupiter, or (2) a reverse-flow exists beyond 60 degrees, and/or there

is a longitude dependence in this flow. Hinode/SOT showed that the pole is not filled with a diffuse field, but it contains highly concentrated unipolar patches. STEREO A and B provided invaluable synchronous observations, which led to discovery of inertial waves. (Unfortunately, such observations were extremely limited owing to the loss of STEREO B.) Currently, the integrated polar flux is the best predictor of the subsequent solar cycle strength, which is highly dependent on global flows, but there is no clear evidence as to whether this relationship is causal or correlational.

PSG 1 emphasizes the need to carry out studies of the Sun that have long-term global coverage. There are currently two major gaps in observations: (1) measurements are largely limited to the Sun–Earth line; that is, synchronous observations of near and far-side are severely limited; and (2) with ground-based and space-borne instruments only in the ecliptic plane, observations of polar regions are severely limited. Expanding observational coverage to the poles and the far-side of the Sun is necessary to probe deeper into the interior of the Sun, to measure the full open magnetic flux in the heliosphere, and to determine how active regions’ magnetic fields are distributed around the Sun and drift toward the poles to cause polar fields. Pole-to-pole observations at all solar longitudes along with simulations will be essential in the next decade toward developing a complete understanding of the dynamo generation of magnetic fields and their emergence at the photosphere (including their spatio-temporal distribution), and how they shape the global corona and heliosphere.

System-Level Science Contributions

PSG 1 is intimately connected with all the SHP science goals, including the SHP LRG and EOs. There are three main points of synergy: variability, energetics, and context.

First, variability in the decadal, quasiannual, and weeks/months timescales provides the backdrop against which both magnetic and radiative environments in the corona and heliosphere are established (PSG 2); it determines the frequency of explosive events and the heliospheric structure in which they dissipate in the solar system (PSG 3); and it determines the environment in which cosmic rays are propagated from outside the heliosphere (PSG 4).

Second, energetics driven by the spatio-temporal evolution of global magnetic fields provide the energy and structure that determines the origin and properties of the solar wind (PSG 2) and determines the relative intensity of explosive events (PSG 3).

Third, the observation of global magnetism and the way it structures heliospheric plasma is necessary to provide context to direct measurements of coronal and heliospheric magnetic fields (LRG) and well-measured global plasma flows and magnetism (from pole to pole) will play a critical role in constraining the dynamic regime that contextualizes what kind of star the Sun is (EO 1).

B.2.2 Priority Science Goal 2

The generation of the solar atmosphere and its expansion into the extended heliosphere depend on a complex interplay of multiple elements even in periods of low solar activity, including subsurface and convective flows, magnetic, sound and plasma waves, and, most importantly, the ever-changing magnetic field that permeates it. In order to understand such a complex and interconnected system, researchers need to jointly address fundamental phenomena, such as the transport and dissipation of nonthermal energy from the photospheric reservoir to produce and energize the dynamical and spatially structured chromosphere and corona; the creation of the solar wind and its spatio-temporal structuring at different scales; and the structure and evolution of the magnetic field in the outer atmosphere and heliosphere.

Recent developments in the capability to infer the chromospheric and coronal magnetic field strength and topology, as well as novel observations from multiple vantage points within the ecliptic, are paving the way to a “system science” approach. Together with a number of complementary facilities and missions scheduled to commence or ramp up operation in the next few years, this capability will allow researchers to causally connect the fundamental phenomena creating the solar atmosphere as a whole—from the solar surface to the heliosphere.

PSG 2 (Table B-2) captures the community’s need to more comprehensively understand the physical interconnections linking the Sun through the heliosphere. This goal also has obvious ties to the broad astrophysical questions

TABLE B-2 Sun and Heliosphere Priority Science Goal (PSG) 2 and Objectives

| PSG 2 (of 4) | Objectives |

|---|---|

| How do the Sun’s magnetic fields and radiation environments connect throughout the heliosphere? |

|

of how stars create their atmosphere and influence their environment and how this determines the habitability of stellar systems besides our own.

Current Research Activity

Priority Science Goal 2, Objective 2.a

The constant interaction between photospheric flows and surface magnetic fields is ultimately responsible for structuring the solar corona both in quiet and active regions. Yet researchers are just starting to uncover the detailed operation of many different processes, including how the dynamics of small-scale magnetic elements (at granular sizes and below) influence the response of the upper atmosphere, and how the highly variable chromospheric magnetic topology and plasma density mediate the transfer of mass and energy to the corona and beyond. Substantial progress on this topic will require a multipronged approach, including high-resolution, high-cadence measurements of both the photospheric and chromospheric vector magnetic field; multiwavelength diagnostics of the coronal emission; reliable inversion techniques to obtain the thermodynamic plasma parameters and their evolution; as well as realistic numerical simulations of the highly coupled solar atmosphere.

Priority Science Goal, Objective 2.b

Outside of transient, explosive events like flares, the Sun maintains a multi-million-degree corona in both quiet and active regions that are characterized by closed magnetic configurations. Within coronal holes, dominated by open fields, temperatures around 1 MK are sustained. The exact mechanisms that heat the corona and accelerate the solar wind continue to be debated, but there is a growing body of evidence that they operate on small spatial and temporal scales, mediated by the overall coronal magnetic structure. Furthermore, many of the physical transitions and processes that govern the acceleration of coronal outflow are thought to occur in the middle corona (1.5–6.0 R⊙; see Figure B-8), a region currently lacking significant observational coverage. High-cadence diagnostics of the plasma (temperature, density, composition) and particle (distribution, localization) throughout the corona, including the middle corona, will need to be applied in concert with high-resolution data from the lower atmosphere, as well as with in situ measurements of fields and plasma properties. Polar observations, both in situ and remote sensing, will be extremely valuable as they provide a direct view of the processes leading to the acceleration of the fast solar wind.

Priority Science Goal, Objective 2.c

The coronal and heliospheric magnetic field provide a pathway for energetic particles accelerated near the Sun to expand out into the heliosphere, at times over wide latitudinal and longitudinal ranges, indicating complex magnetic connections in the inner heliosphere. Both the structure of the coronal field and its temporal evolution as well as the nature of the extension of the coronal field into the heliosphere via the interplanetary magnetic field are currently poorly understood, and studies rely mostly on extrapolations from surface magnetic fields and global models. This suffers from a number of limitations, including the fact that the usual assumption of force-free

NOTE: CME, coronal mass ejection; EUV, extreme ultraviolet.

SOURCES: West et al. (2022b), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11207-023-02170-1. CC BY 4.0; Sun image from West et al. (2022a), https://doi.org/10.1007/S11207-022-02063-9. CC BY 4.0.

field is not satisfied in the photosphere. A concerted effort at improving extrapolations by using multiheight field measurements, as well as reliably estimating the coronal field and its evolution using a variety of diagnostics, together with measurements of in situ fields and plasma properties in different points of the inner heliosphere, are necessary to make substantial progress.

Priority Science Goal, Objective 2.d

The solar wind is observed to vary over a range of spatial and temporal scales, with processes interacting across these scales. Most measurements of solar wind variability have been conducted with single spacecraft observations, making it difficult to disentangle spatial and temporal variations. Additionally, determining the source of the variability is a challenge as both heliospheric processes and processes in the solar corona can imprint their changing plasma characteristics on the wind. Faster solar wind from coronal holes is observed to be less variable in many ways than slower solar wind from outside of coronal holes and from equatorial regions. Determining the origin of this variability, whether it is owing to local kinetic processes or underlying global solar activity, is critical

to understand the connection between the solar atmosphere and the solar wind, as well as the influence/interaction of the solar wind on/with the space environments of solar system objects throughout the heliosphere.

Observational Resources

Many of the existing and near-future solar missions and ground-based facilities are relevant to PSG 2. Notably, during the past decade there has been an increased focus on the complementarity of these multiwavelength, multidiagnostics facilities that attempt to relate phenomena observed in the upper atmosphere and solar wind to their source regions at the solar surface.

Large-aperture ground-based telescopes equipped with Adaptive Optics systems, such as the Dunn Solar Telescope (DST), the Swedish Solar Tower (SST), the 1.6 m Big Bear Solar Observatory Goode Solar Telescope (BBSO/GST), or the recently commissioned 4 m Inouye Solar Telescope can observe the solar surface at very high spatial resolution. This resolution is necessary to clarify how small-scale phenomena of magneto-convective origin might structure the upper solar atmosphere, both in quiet and active regions. As a relevant example, recent remarkable GST observations of the photospheric magnetic field at scales of less than 200 km on the Sun highlighted how dynamic minority-polarity intrusions in the magnetic network actively cancel with the dominant polarity field, driving an upper atmospheric response in the form of intermittent chromospheric spicules and coronal jetlets, which are likely an important source of energy injection into the corona. Spicules have indeed been observed with IRIS and SDO to be heated to transition region and even coronal temperatures, while jetlets have been observed by SDO’s Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) as intermittent hot-plasma outflows, possibly related to the nascent solar wind. A similar picture, detailing how quiet-Sun coronal loops connect and respond to surface regions harboring weak and rapidly evolving (<5 minutes) magnetic elements, has been inferred by using SO/PHI and EUI. The 4 m optical/IR Inouye, recommended in previous decadal surveys and currently in the operational commissioning phase, is now truly pushing this frontier by showing that the relevant spatial scales might be even smaller. Figure B-9 shows how the footpoints of magnetic flux tubes, identified by intergranular bright points, are actually only 30–50 km wide at the solar surface.

Measurements of flux tube dynamics (including transverse and rotational motions) and of their photospheric field strength and topology will be necessary to assess the energy available in these magneto-convective phenomena. Stereoscopic observations of these photospheric magnetic fields with PHI, together with instruments along the Sun-Earth line, will allow for regular removal of the 180 degrees ambiguity in the orientation of the transverse component even for small scale features, greatly aiding in the derivation of the chromospheric fields’ topology. The coronal response might be estimated using coronal imagers such as SDO/AIA (assuming they will continue operating) but to make sustained progress, a spatial resolution of order 20–300 km (depending on the wavelength and height), as demonstrated by the High-resolution Coronal imager (Hi-C) in previous rocket flights, and as now provided by SO/EUI, will be necessary. Thus, coordinated campaigns will be a critical tool to ensure that common targets are observed by multiple facilities during the relatively short remote sensing windows planned for SO (three 10-day periods per orbit). In the near future, the high-cadence EUV context-imager of the Multi-slit Solar Explorer (MUSE) and the EUV High-throughput Spectroscopic Telescope (EUVST) missions (launch currently set for 2027 and 2028, respectively) will be momentous for this PSG, both providing complementary EUV spectroscopy with high spatial (down to ~200 km) and temporal (few seconds) resolution.

Ultimately, however, reliable assessments of the energetics of events in the upper solar atmosphere require information on density, temperature, and velocity—that is, spectroscopical capabilities. Chromospheric and transition region spectra acquired with the IRIS UV imaging-spectrograph, in operation since 2013, have contributed multiple critical insights—for example, highlighting the role of reconnection as a result of flux emergence in heating the low solar atmosphere; confirming the presence of nonthermal particles in coronal nanoflares; identifying resonant absorption and dissipation of Alfvénic waves; and elucidating the mechanisms of thermal nonequilibrium and thermal instability in the corona. Coronal spectroscopy has been performed by the EUV Imaging Spectrometer (EIS) on board Hinode since 2006, providing notable results such as coronal plasma composition and its spatial variation, or the presence of high-velocity coronal upflows and heating in the periphery of (quiescent) active regions, which have been associated with chromospheric spicules and the origin of the slow solar wind. Still, its relatively

SOURCE: NSO/NSF/AURA, https://nso.edu/telescopes/dkist/first-light-cropped-image. CC BY 4.0.

low cadence (tens of minutes) and coarse spatial resolution (~2,000 km) are now hindering further progress. With their enhanced performances, the EUV coronal spectrograph SPICE on SO, as well as the upcoming MUSE and EUVST missions, will make headway toward resolving the sources of energy flow into the corona.

An even larger step toward resolution would include the combination of soft X-ray (SXR) and hard X-ray (HXR) imaging and spectroscopy, because these regimes contain key diagnostic wavelengths for disambiguating between coronal heating mechanisms—namely, wave versus impulsive (e.g., nanoflare) heating. Heretofore, the technologies needed to make such measurements have been out of reach owing to sensitive fabrication tolerances and lack of analysis techniques; however, pioneering instruments and analysis tools have finally become available, thanks to the NASA sounding rocket and CubeSat programs, which can spectrally probe active region loop heating. Owing to the complexity and breadth of coronal temperature distributions (many orders of magnitude in brightness across more than an order of magnitude in temperature), the greatest advances in understanding the impulsivity of coronal heating will come from combining EUV with both SXR and HXR measurements in an optimized, consistent, and systematic way. In addition to these thermal diagnostics, nonthermal particles produced by extremely small reconnection events (i.e., nanoflares) have been regarded as one outstanding driver for coronal heating. Although their presence has been suggested by HXR observations of their more energetic counterparts by the NuSTAR and the Reuven Ramaty High Energy Solar Spectroscopic Imager (RHESSI), ubiquitous UV transient brightenings observed by IRIS, and, more recently, in situ measurements made by PSP, direct observations of the nonthermal signatures have been elusive. Measurements of nonthermal electrons, as diagnosed via sensitive HXR and radio imaging spectroscopy observations, would strongly constrain the energy input and impulsivity of coronal heating.

The continuous coverage of SDO instruments has been a vital asset for most solar, heliospheric, and space weather studies in the past decade; notably, maps of photospheric and chromospheric intensities from HMI and

AIA are necessary to accurately identify the position and context of high-resolution, small, fields-of-view observations (such as those provided by IRIS, Hinode, and Inouye) on the solar disk. The full-disk maps of photospheric magnetic field from SDO/HMI, as well as from NSF’s GONG or Synoptic Optical Long-term Investigations of the Sun (SOLIS) facilities, are routinely used to estimate the magnetic field strength and topology in the corona and the heliosphere. These are necessary to understand the flow of mass and energy that heat and energize the corona, solar wind, and energetic particles.

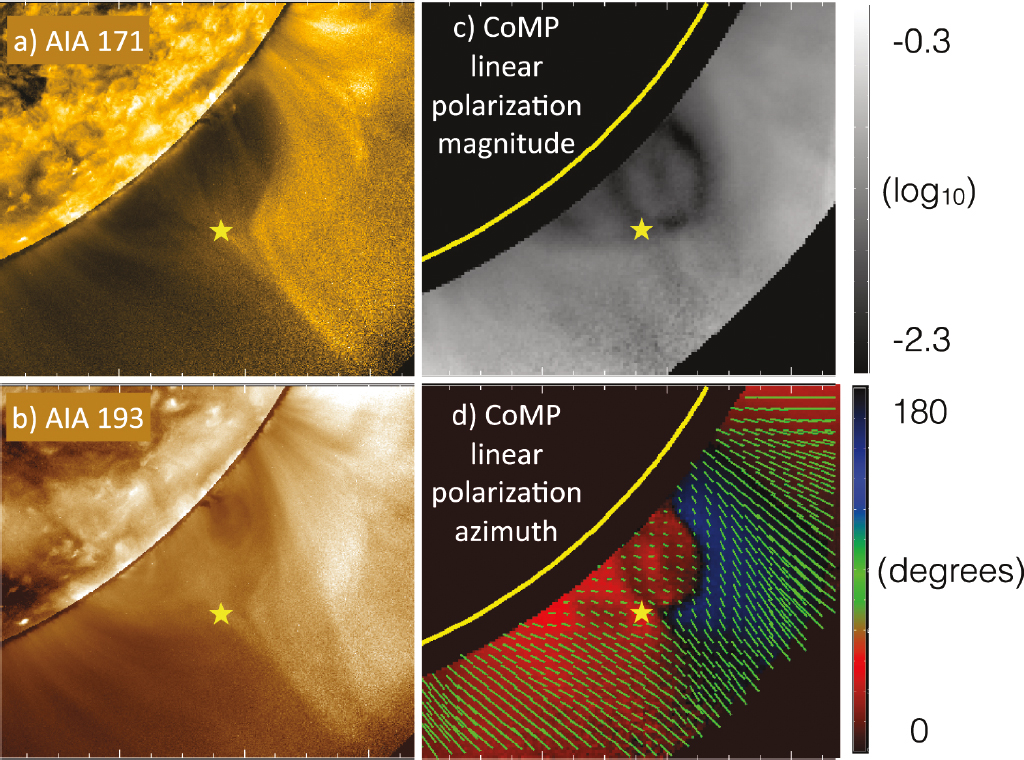

Despite increasingly realistic assumptions about the forced and nonpotential nature of the photospheric field and other constraints, it has been challenging to critically test the accuracy of these extrapolations. Direct field measurements in the upper solar atmosphere, as well as their use to improve extrapolations, remain a long-term goal for the solar community. Steps in this direction are now being taken, such as high-sensitivity polarimetric measurements in the chromosphere (using Fabry-Perot systems like DST/Interferometric Bidimensional Spectropolarimeter [IBIS] and SST/CRisp Imaging SpectroPolarimeter [CRISP]; IR spectrographs such as Inouye/Visible Spectro-Polarimeter [ViSP] and GREGOR/GREGOR Infrared Spectrograph [GRIS]; or UV spectrographs like the Chromospheric Layer Spectropolarimeter [CLASP] sounding rocket) that are providing initial results on the full vector chromospheric fields in plage regions. If selected past Phase A, the Chromospheric Magnetism Explorer (CMEx) SMEX mission will be a dedicated facility to diagnose magnetism from the solar photosphere to the transition region. Linear polarization of visible and near-IR coronal lines in off-limb structures has long been utilized by the Coronal Multi-channel Polarimeter (CoMP) coronagraph and its successor UCoMP to infer the direction of the coronal magnetic field for structures as extended as 2 R⊙.

Acquiring the coronal field strength, however, requires precise measurements of the Zeeman circular polarization signal, orders of magnitude weaker than the linear one. Currently only Inouye, with its large collecting area, offers the possibility to derive such a quantity at high resolution over active-region-size fields of view, with initial results only now being realized. Other, complementary techniques are also being tested at this moment, including time-distance coronal seismology; magnetically induced transition of EUV lines (magnetic-field-induced transition [MIT], a new diagnostic technique that leverages a peculiar atomic physic configuration of Fe X, giving rise to an additional transition of the 257.26 Å EUV line in the presence of a magnetic field); and microwave observations of gyroresonance and gyro-synchrotron emission from thermal and nonthermal electrons in active regions. A robust effort will be required in the next decade to obtain reliable and consistent estimates of the vector field in the corona using this variety of methods (see also the LRG in Section B.3).

The heliospheric component of the HSO fleet has grown remarkably in the past decade. Recent missions such as PSP and SO enable heliospheric observations in the poorly sampled inner heliosphere, improving the ability to make connections between the coronal and the interplanetary medium, including the solar wind. These missions, along with L1/1 AU missions like the Atmospheric Composition Explorer (ACE), Wind, Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR), STEREO, Ulysses which explored out to 5.4 AU, New Horizons, and the Voyager spacecraft have given us critical insight into the global structure of the heliosphere and in situ processes that affect particles and magnetic fields in the heliosphere. These heliospheric measurements also provide insight into the influence of the dynamic solar atmosphere on its extension out into the solar system. In particular, the combination of in situ measurements of plasma, waves, energetic particles, and magnetic fields provide information on the state and evolution of the solar wind and inform its connection back to the Sun.

These measurements have mostly been made at a distance of 1 AU, with some planetary missions providing data from other vantage points. Ulysses ended in 2009, ending access to the out-of-ecliptic view of the solar wind, in particular access to the polar regions above the Sun. As discussed in the Section B.2.2 discussion of PSG 2.a, SO will give us a new chance to sample the heliosphere out of the ecliptic (in the later years of the mission, up to 35 degrees) and give us a new vantage point in the inner heliosphere, with complementary instrumentation to PSP. SO provides both remote sensing and in situ observations of solar wind plasma, energetic particles, and processes in the inner heliosphere for the first time from the same platform. PSP provides measurements of the plasma, magnetic field, and energetic particles in the inner heliosphere and into the corona as close as ~9 R⊙, but with limited remote sensing instrumentation.

To bridge the gap between in situ and remote sensing measurements of the Sun, instruments like the Wide-Field Imager for Parker Solar Probe (WISPR) and the Heliospheric Imager on SO (SoloHI) provide views of the

earliest stages of the solar wind, as plasma erupts and flows out of the corona and merges into the interplanetary medium. These instruments reveal the structure, density, and velocity profiles of flows inside 1 AU. The future PUNCH mission will similarly image the inner heliosphere, along with a complementary coronagraph and student-provided X-ray spectrometer.

The HelioSwarm mission, with a planned launch in 2028, will consist of a constellation of nine spacecraft in a polyhedral configuration, with separations ranging from MHD (3,000 km) to sub-ion (50 km) scales. The goal of this mission is to examine the 3D nature of turbulence in the heliosphere and how it drives the transport of mass, momentum, and energy in the heliosphere and beyond. HelioSwarm’s orbit will take it into the solar wind, magnetosphere, and magnetosheath.

Theory, Modeling, and Simulations

Theory and modeling efforts are a vital component of the system-science approach that characterizes PSG 2. First and foremost, models can “fill the gap” of the currently sparse observations of crucial parameters like the coronal magnetic field, which is the building block of all magnetic connectivity studies. Furthermore, they represent a necessary tool to properly interpret spectral signatures formed by a host of physical processes such as magnetic reconnection, waves, and shock dissipation, and so on that contribute to the creation of the highly dynamic outer solar atmosphere.

State-of-the-art, time-dependent, 3D MHD simulations of the solar atmosphere (e.g., Bifrost, Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research/University of Chicago Radiative MHD [MURaM], Radiative MHD Extensive Numerical Solver [RAMENS], Alfven Wave Solar Model [AWSoM], Athena++, and Adaptively Refined MHD Solver [ARMS]) achieve a high degree of realism and are starting to emulate many observed phenomena, including surface magneto-convection, chromospheric fine structure, and even the emergence process of flare-productive active regions leading to coronal flaring signatures and CMEs. Thanks to the increasing level of computational power, simulations are now starting to explore the effects of important nonidealized processes such as radiative scattering or nonequilibrium hydrogen and helium ionization (Figure B-10). Future developments will also need to move beyond the single-fluid approximation of MHD and consider the effects of multifluid approximation interactions to properly understand the partially ionized chromosphere, a crucial interface region responsible for many coronal properties, such as the observed abundance variations between open and closed field structures. A goal within the next decade is that of physically coupling such models of the solar atmosphere to those of the solar interior (see Section B.2.1), to reproduce the whole process of magnetic field generation, transport and emergence at the surface, and the consequent shaping of the solar atmosphere.

Together with these ab initio models, an important line of research now involves data-driven models of the solar coronal magnetic field and its evolution, such as the Coronal Global Evolutionary Model (CGEM). These models incorporate observed, time-dependent boundary conditions (e.g., the vector magnetic field maps from SDO/HMI) and use various techniques to derive electric fields or plasma velocities necessary to infer the field at different heights. Of particular note is the recent use of neural-network techniques to estimate the all-important surface transverse flows, particularly difficult to measure via direct observations. How to properly incorporate the increasing number of multiheight observations (all obtained at different cadences and resolution) in the models remains an active subject of research.

A proper comparison of the models with the real physical conditions in the solar atmosphere requires reliable and accurate inversions of observed spectro-polarimetric diagnostics. Most of the current techniques use relatively coarse assumptions, including one-dimensional (1D), spatially independent atmospheres, hydrostatic equilibrium, without any reference to nonequilibrium, self-consistent physical processes. A concerted effort is now required to improve these techniques, including a better theoretical understanding of 3D radiative transfer deviations from high-energy, time dependent, nonlocal thermodynamic equilibrium hydrogen ionization. Given the enormous volume of data provided by current telescopes, as well as the high computational costs of spectral inversions, efficient exploitation of computing resources is necessary, and efforts are under way to understand how machine learning approaches can accelerate the process. The complementary approach of forward-modeling the spectral observables in the realistic model atmospheres is also of large value, because it facilitates determining

SOURCE: J. Martinez-Sykora, J. Leenaarts, B. De Pontieu, D. Nóbrega-Siverio, V.H. Hansteen, M. Carlsson, and M. Szydlarski, 2020, “Ion–Neutral Interactions and Nonequilibrium Ionization in the Solar Chromosphere,” Astrophysical Journal 889(2):95, https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ab643f. © AAS. Reproduced with permission.

the sensitivity of different observables to specific physical conditions in the source atmosphere and, in turn, the identification of missing physics in the models.

Models of the solar corona, when paired with heliospheric models, can provide the best opportunities to map heliospheric plasma and structures back to the Sun; however, even these suffer significant ambiguity into how the magnetic field above the Alfvén surface (the region beyond which most disturbances in the solar wind are unable to propagate back to the photosphere) connects down into specific magnetic structures on the surface. Models like the S-Web, Wang-Sheeley-Arge (WSA), and Space Weather Modeling Framework/AWSOM have made significant advances in more accurately describing the connections between the Sun and the solar wind and heliosphere, but still suffer from incomplete treatment and understanding of physical processes in the corona and heliosphere. For example, the lack of observations of the polar coronal fields significantly impact the ability of these models to correctly specify polar fields and thus realistically model the connections at high latitude. Work is ongoing to connect remote observations of the Sun with heliospheric observations, with models that extend from the solar corona out into the heliosphere, providing a framework for connecting these two regions. Where available, observations can be leveraged to constrain these models both at the Sun and also in the heliosphere. The models inform the understanding of the physics and connections, but ambiguity and difficulty still persist in truly making direct connections between the models and data.

In addition to MHD models describing the interplay between the magnetic field and plasma, kinetic models and models of particle acceleration and transport are key to understanding solar and heliospheric processes and their interconnection. In particular, processes like magnetic reconnection, turbulence, and wave-particle interactions must be treated with kinetic simulations. Models of particle acceleration and turbulent reconnection include

Particle in Cell (PIC) simulations and Vlasov simulations, which can be computationally expensive and do not make predictions on temporal and spatial scales that are observable with remote sensing techniques. Some of these simulation techniques may benefit from advanced algorithms, including machine learning and advanced graphics processing unit–accelerated codes. Further integrating kinetic simulations with MHD models into hybrid models will be key to improving descriptions of the heliosphere.

Solar and heliospheric models have also been extended to other star/planetary systems. As more and more exoplanets are identified around host stars, the question of the influence of their local space environment on their habitability needs to be addressed (see Section B.4.1). Initial work with MHD models has been extended to other astrospheres. This work continues and can be augmented with increased complexity into the next decade. There is a clear need for interdisciplinary work between the astrophysics community and the solar and heliophysics community in terms of collaborative model development and implementation.

Motivation for the Goal

The past decade has witnessed impressive advances in observational and modeling capabilities of the quiescent solar atmosphere and wind. Many of the novel results have further cemented the concept that small-scale phenomena play a fundamental role in creating and structuring the outer atmosphere. Modern facilities like the GST, Inouye, or SO are now available to study in great detail the photospheric flows and magnetic fields that are the ultimate source of the energy necessary for the existence of a corona and wind. However, substantial progress will require a consistent, system-wide approach where these “photospheric inputs” can be causally connected with the properties of the outer atmosphere.

PSG 2 details multiple areas where new development is needed to further advance knowledge of this highly interconnected system. These include high-resolution coronal imaging and spectroscopy to uncover the fundamental characteristics of heating processes; next-generation, highly sensitive radio and HXR instruments to provide unambiguous diagnostics of nonthermal particles in the corona; and remote sensing and in situ observations of solar wind plasma, energetic particles, and processes in the inner heliosphere from multiple vantages around the Sun. Direct observations of the polar magnetic fields and wind properties ultimately will be needed to properly model the magnetic connectivity at high heliospheric latitudes. Most importantly, major efforts will need to be devoted to obtaining reliable, direct measurements of the strength and topology of the magnetic field in the chromosphere and corona, which critically modulates the flow of energy and mass in the whole atmosphere and heliosphere.

System-Level Science Contributions

Making connections between the phenomena observed in the heliosphere and their solar sources is challenging as the plasma originates in the corona where dynamic processes drive the evolution and connections of the coronal magnetic field on timescales of minutes to hours. After radially expanding, the rotation of the Sun creates a magnetic field that can be approximated by the Parker spiral, but evidence from SEP acceleration and transport in the heliosphere across wide longitudinal ranges indicates that the connections back to the Sun do not always follow a simple Parker spiral. These deviations observed in the propagation of SEPs may depend on the background solar wind structure and cross-field diffusion of particles.

Observations of SEPs reveal important insights into physical processes occurring both at their source as well as those influencing their propagation to where they are observed. In the heliosphere, local processes such as acceleration at shocks, plasma compressions, and magnetic reconnection modify the energy of particles, while propagation within plasma turbulence leads to particle scattering and diffusion, and within large-scale structures and current sheets, there are also drift motions. Understanding these processes reveals the nature of the heliospheric magnetic field. The existence of quiet-time high-energy tails on solar wind velocity distributions suggests a persistent stochastic acceleration process occurring in the solar wind in the heliosphere, likely related to turbulence, and which may become more important in the outer heliosphere. Relating SEP characteristics to their solar sources is an area of active research, but this is largely unexplored in the polar regions of the heliosphere. In the energy

range between high-energy SEPs and low-energy thermal particles are suprathermal particles whose physics is presumably affected by small-scale kinetic processes. Missions that study local kinetic processes are necessary to improve the understanding of particle acceleration and transport at shocks and in quiet solar wind. The upcoming HelioSwarm and Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) missions are expected to provide significant new observations, complementing those of PSP and SO.

Solar wind heavy ion and elemental composition measures are vital tools for tracing heliospheric plasma back to coronal and chromospheric sources at the Sun. These observational tools are critical to understanding the heating, energization, density structures, dynamic processes, and elemental fractionation in the solar atmosphere. Heavy ion composition also serves as an invaluable tool to identify and classify different sources of plasma (e.g., the interstellar medium, comets, planetary atmospheres) throughout the heliosphere. Inclusion of heavy ion composition measurements on future missions will be critical in supporting connectivity science.

Reconnection is a fundamental process throughout the heliosphere, from the Sun to the outer reaches. Close to the Sun, in addition to driving larger explosive events, reconnection may serve to heat the corona and transport open magnetic flux via interchange reconnection between open fields and closed magnetic fields in large coronal loops. Evidence for the presence of ubiquitous small-scale magnetic reconnection events is thought to exist in the prevalence of switchbacks in the interplanetary magnetic field and energetic particles observed by PSP. Reconnection in the heliosphere can modify the topology of the global heliospheric magnetic field, eroding the magnetic flux added from CMEs. Reconnection exhausts observed in the heliosphere have been shown to be statistically associated with MHD turbulence–driven magnetic field fluctuations. Remote sensing observations of small-scale reconnection events provide crucial input on the energy balance and transport of the solar corona and heliosphere. Meanwhile, a detailed understanding of physical processes from macroscopic to kinetic scales (i.e., down to size scales smaller than the ion gyroradius) through in situ observations and modeling is necessary to further advance studies of phenomena such as magnetic reconnection, turbulence, and collisionless shocks.

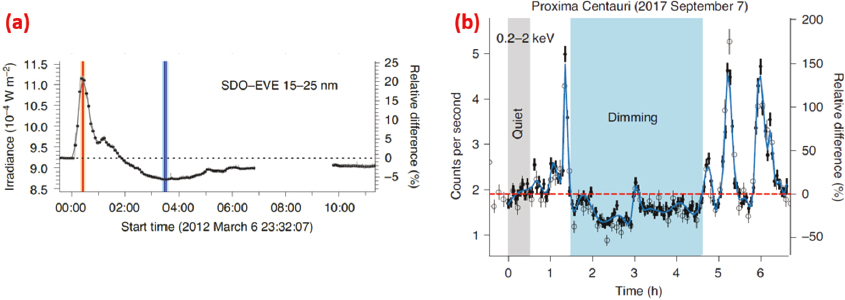

B.2.3 Priority Science Goal 3

Solar explosions are the most energetic phenomena in the solar system. Thanks to their proximity, they serve as an excellent laboratory to study fundamental physical processes, including magnetic reconnection, particle acceleration, plasma heating, and shock waves. Meanwhile, large solar eruptive events are the most important drivers for space weather. They affect the entire heliosphere, including, most critically, the near-Earth and deep space environment where humans live and work or where they may someday hope to travel. This science goal also has extensive ties to astrophysical contexts outside the solar system, as questions of how particles are accelerated and how plasma is energized and ejected are ubiquitous across diverse astrophysical phenomena. Furthermore, the explosive release of energy is fundamental to understanding the habitability of stellar systems besides our own and provides signatures that can be studied in other systems.

PSG 3 (Table B-3) captures the community need to understand the origin of solar explosions and how they unleash their energy throughout the heliosphere. This goal is an outstanding, and pressing, motivation of the next decade.