A New Vision for Women's Health Research: Transformative Change at the National Institutes of Health (2025)

Chapter: Appendix A: Committee Analysis of National Institutes of Health Grant Funding for Women's Health Research: Methodology

Appendix A

Committee Analysis of National Institutes of Health Grant Funding for Women’s Health Research: Methodology

Authors: Hamad Al-Ibrahim,1 Susan Cheng,2 Nancy Sun,2 Julianne Kwong,2 and Wasay Warsi2

INTRODUCTION

Congress tasked the Committee on the Assessment of National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research on Women’s Health to conduct an analysis of the proportion of NIH-funded research on women’s health, including conditions that are female specific, are more common in women, or differentially affect women via sex differences. The committee used a multimethod and multistaged approach for a comprehensive analysis of NIH funding on women’s health research (WHR). This analysis focused on the last 11 full fiscal years (FYs) of funding, FY 2013–FY 2023, to discern trends over time, while accounting for expected deviations in funding allocation resulting from known events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The committee obtained the data analyzed for each FY on April 25, 2024, through the publicly available NIH ExPORTER3 online tool, which includes all data in NIH RePORTER (811,599 grants).4 The data available for each grant included the grant title and number, name of the principal investigator(s), dates of funding, amounts of funding (total costs without direct and indirect cost breakdown), abstract text (also known as the “summary”), and public health relevance statement (also known as the “narrative”). These data, compiled across the study period, composed the study dataset. Additional data

___________________

1 Policy Tech Innovation LLC; Social and Economic Survey Research Institute, Qatar University.

2 Department of Cardiology, Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

3 See https://reporter.nih.gov/exporter (accessed April 25, 2024).

4 See https://reporter.nih.gov/ (accessed April 25, 2024).

pertaining to each grant, such as the actual contents of each grant proposal or submitted progress reports, were not available for analysis (see limitations section). The committee’s analysis of results and findings are in Chapter 4.

TRAINING SET

Anticipating the need to develop an algorithm to identify from the dataset the funded grants related to WHR, the committee developed a training set of grants. After cleaning grant abstract text, including removing stop words, removing punctuation, and stemming words, the committee applied unsupervised k-means clustering method to identify up to five clusters of grants per FY. The committee did so using the similarity of words provided in the abstract, such that certain clusters were more likely to be enriched with words including or related to topics that may have had time-specific relevance. For example, COVID-19 was predominant among grants funded in FY 2020, FY 2021, and FY 2022. For each FY, the committee then identified an equal number of grants within each cluster that did or did not contain the key term “women.” The committee randomly sampled a total of 80 grants per FY, including 20 grants (four from each cluster) containing the key term “women” and 60 grants (from each cluster) without it for a total of 800 grants representing the breadth of grants that were funded over a 10-year period.

Two teams of trained researchers separately adjudicated the data in NIH RePORTER for each of these 800 grants, using both a binary and an ordinal scoring system. The binary scoring system consisted of a simple “yes” or “no” for “probably women’s health related.” The five-level ordinal scoring system range included 1 for “not related,” 2 for “minimally related,” 3 for “moderately related,” 4 for “largely related,” and 5 for “definitely or completely related.” After each team separately adjudicated all 800 grants, a third-party reviewer with multidisciplinary expertise on research both related and unrelated to women’s health reviewed the teams’ results, including any details regarding discrepancies, which accounted for approximately 8 percent of the total. All identified discrepancies were then resolved by third-party review with feedback provided to the two primary teams and full consensus reached, resulting in the final adjudicated dataset that comprised the training set for analyses.

EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

The initial stage of analyses involved evaluating an empirical approach to identifying women’s health–related research from the larger grant dataset. The committee generated a list of over 430 key terms representing conditions, diseases, concepts, treatments, and methodologies either specific to or related to women’s health. The committee reviewed each term to include

all possible forms, such as “sex biased” versus “sex-biased,” and assigned a priority score out of 100 to represent its relevance to women’s health. For conditions and diseases, the committee included only those with at least two-thirds prevalence in women documented using the most up-to-date published data, as reported in epidemiology studies available in PubMed, on prevalence rate for women compared to men, and this was used to assign the priority score. For conditions and diseases, an alternate approach could involve weighting relevance based on disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) instead of prevalence, although DALY data are not as readily available for all conditions and diseases included in the analyses.

The committee developed an algorithm to calculate a relevance score based on a search script to identify terms listed within three locations for any given grant: the abstract (summary), public health relevance statement (narrative), and grant title. The score was calculated as:

Relevance score =

1 * ([frequency factor * priority score] for any term(s) appearing in the summary)

+ 5 * ([frequency factor * priority score] for any term(s) appearing in the narrative)

+ 10 * ([frequency factor * priority score] for any term(s) appearing in the title)

Frequency factor = (the number of times a term appeared in a section of text) / (the total number of words in that text).

The committee applied this algorithm to a pilot test of 40 grants, and performance was suboptimal: a sizable proportion of WHR research grants were misclassified or miscategorized when results were compared to the adjudicated women’s health relevance score. Fine-tuning the weightings used in the relevance score calculation did not substantially change these findings. For this reason, the committee developed a natural language processing–based algorithm instead.

Natural Language Processing–Based Analysis

The committee used large language models (LLMs) for the analysis given their ability, as large, deep learning models, to process human language text, such as in a grant title, abstract, or narrative, and derive predictions on vast amounts of similar data based on pretraining. In effect, a successful LLM algorithm can accurately identify and categorize a grant as related to women’s health based on all available relevant information, just as a human should be able to confidently perform the same task after learning from experience and training what kind of title, abstract, or narrative is characteristic of a grant focused on research relevant to women’s health.

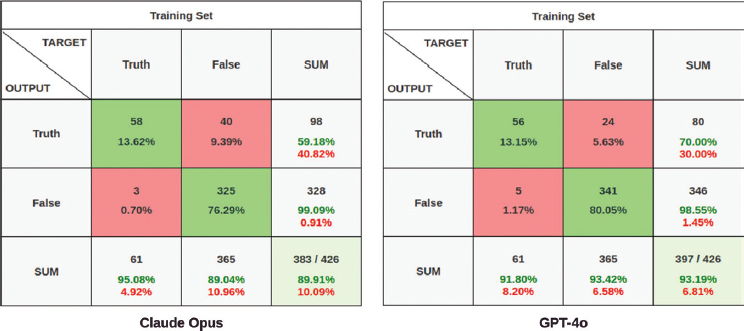

First, the committee conducted a comparative analysis of various available LLMs, recognizing the breadth and complexity of the task; women’s health spans multiple conditions, diseases, and domains of biomedical science. These LLMs included GPT-3.5 Turbo, GPT-4o, Claude Sonnet, and Claude Opus, with the committee selecting the flagship model from each provider—GPT-4o and Opus—and comparing each on a random set of 100 samples against a source of truth (the human-adjudicated dataset). GPT-4o outperformed Claude Opus with an overall accuracy of 93.19 percent but lagged in true negatives (see Figure A-1). Additional LLMs may be tested in the future, including Llama3, Google Gemini, Anthropic Claude, and Falcon. Future analyses may also consider applying multiple algorithms in parallel as part of efforts to further enhance the quality and consistency of results.

After selecting GPT-4o, the committee repeated a manual review of the training set of WHR-related grants to ensure that sample grants with high relevance scores were truly highly relevant and those with low relevance scores were less or not relevant. A sample set of 426 grants was finalized for an initial algorithm run, which produced some discrepancies; some grants manually assigned low relevance scores were found on re-review to be relevant, and some grants manually assigned high relevance scores were found on re-review to be less or not relevant. A careful examination of each sample grant that produced conflicting results revealed that ambiguity tended to arise for grants related to maternal-child health, where women are involved in the research but at least some or more focus is on child or fetal health outcomes, such as research on risks of pregnant women acquiring Zika virus. Following detailed rereview of grants that tended to result in ambiguous classification, the committee decided to remove grants that

exclusively focused on child or infant health outcomes and retain grants that described plans to assess outcomes in both mothers and children or infants.

The iterative review to identify potential sources of ambiguity and discrepancy in categorization significantly enhanced the model’s accuracy. To address these discrepancies, the committee identified samples where the model’s predictions conflicted with the true positive and true negative classifications. The committee carefully examined each conflicted sample and manually corrected the labels in the new dataset. This meticulous process enabled efficient refinement of the data and improvement of its overall quality. After running the model again and manually analyzing these classifications, the overall accuracy of the model improved to approximately 97 percent. The accuracy of detecting true positives increased from 76 to 86 percent without changing any item in the prompts. There was a slight tradeoff in detecting true negatives, which did not affect the overall trend, as the negatives were filtered with a high accuracy of 98.5 percent in the first step.5 To further assure the quality of the final generated dataset, additional versions of the prompts were tested to clarify identified areas of ambiguity (e.g., classification of a grant related to maternal-child health but focused primarily on child versus maternal health outcomes or a grant related to a disease affecting two sexes and including or not a focus on sex differences or sex-specific outcomes). This additional testing revealed less than 1 percent variation in results generated by different versions of the prompts used. Although several iterations of prompts were used for the analysis, Box A-1 shows a representative version of the main prompt.

Data Extraction

After evaluating and optimizing accuracy of the model and the prompt, the committee extracted data for the analysis. A summary of each major step of the extraction process is listed. Between each one, the committee performed a random sampling of its output before passing it on to the next step. If the accuracy was low during a stage of manual checking, the prior step(s) was repeated with modifications in the prompt to achieve and maintain high accuracy.

First Step: Binary Classification Whether the grant was related to women’s health was identified. These statements defined women’s health studies:

- The study topic directly affects women’s health;

- The subject of the study is another preclinical model species, such as mice, but has potential translation to human women’s health;

___________________

5 Data and additional data tables from this analysis are available in the project’s public access file; materials can be requested from PARO@nas.edu.

BOX A-1

Representative Version of Main Prompt Used for Committee Analysis

## Task: Determine Relevance to Women’s Health

## Instructions: You are an expert in women’s health. Your task is to analyze a given text and determine if it is strictly related to women’s health.

## Step 1: Carefully read the provided summary text.

Criteria for Categorization as relevant to women’s health:

- The study is on a female-specific condition or disease.

- The study is directly related to women’s health.

- The study involves a non-human species, but the results are especially pertinent to or affect the health of women.

- The study is about or includes both women and men, but is focused on a condition or disease that predominantly affects women.

- The study is about sex differences or sex-specific outcomes for a condition or disease that affects both women and men, with a focus on health outcomes in women.

- The study is about or includes pregnant women and is focused on the health outcomes of women, not only on outcomes of the fetus, infant, or child.

## Step 2: Output Your Decision

- If the text is relevant to women’s health, output “YES”.

- If the text is irrelevant to women’s health, output “NO”.

## Response Format:

- YES/NO

## Example Responses:

- YES”

- NO”

- The study is about both men and women, but it predominantly affects women’s health; or,

- The study is about maternal health and has a greater effect on women’s health than child health.

Second Step: Categorization The grants were further categorized as either related or not to maternal health, wherein maternal health was defined as related to studies affecting pregnant and postpartum women and their

health, including prenatal care, pregnancy complications, and conditions related to pregnancy.

Third Step: Identification of Diseases and Conditions The disease or condition in the grant was identified next. Grants could be focused on a specific disease or condition, such as endometriosis or chronic pain; a group of diseases, such as off-target effects of immunotherapy treatment of cancers in women, or conditions, such as interventions to improve sleep disorders in women; or a life stage, such as menopause or advanced aging.

Fourth Step: Disease Classification Given that some grants focused on general disease categories, such as cancer, whereas others focused on very specific subtypes of diseases, such as triple-negative breast cancer, two levels of disease classification were created:

- Level 1: A broad classification based on a broadly used name of the disease.

- Level 2: A specific classification based on a specific disease name extracted from the grant abstract.

Fifth Step: Classification of Specific Diseases of Interest In Step 4, granular-level results were produced with the categories generated by the model. The committee also wanted to be able to report on a somewhat broader level of conditions with all related disorders/diseases included, such as on the broader category of eating disorders versus grants on bulimia, anorexia, and other related conditions individually. Instead of using a model-generated list of diseases and conditions drawn from the database of all grants, in Step 5, a list of prespecified diseases and conditions was given to the model. Terms for this analysis were drawn from the list of women’s health-related terms the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health analyzed in its biennial report (ORWH, 2023) (see Chapter 4), the committee DALY analysis (see Chapter 7), and committee expertise, with a total of 67 diseases, conditions, and terms (see Appendix Table A-3).

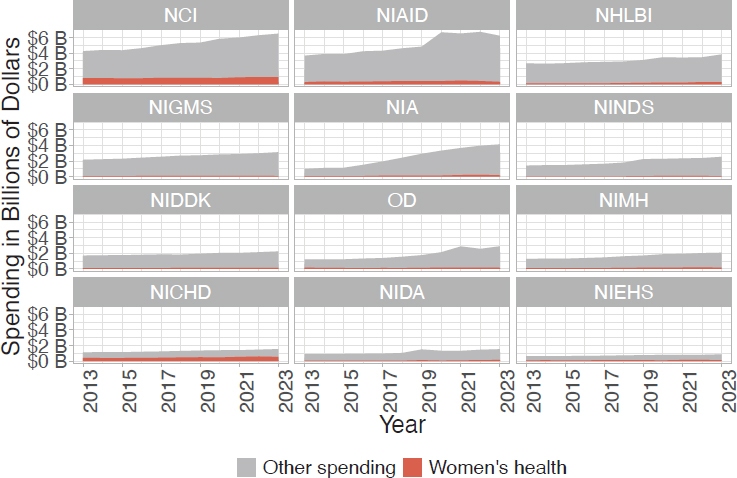

The final data with all generated categorizations were then compiled and underwent several stages of validation by multiple investigators and research staff, iteratively using the NIH RePORTER tool to carefully review all available grant data and verify number, types, and categorizations of grants as identified by the algorithm. These data were used for analyses, including graphical visualizations of funding trends.

The committee used funding Institute or Center (IC), rather than administrative IC, data in this analysis and combined data for ICs that were redesignated within the analysis period (i.e., the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities was redesignated to the National Institute on

Minority Health and Health Disparities in 2010 and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine was redesignated as the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health in 2014) (NIH, 2023a,b).

Limitations

Several limitations merit consideration. The final algorithm applied to identify grants related to women’s health is not expected to have achieved perfect accuracy for many reasons, including lack of access to the contents of the full grant and, in turn, limited ability to discern if the information in the abstract contained terms or concepts pertaining to women’s health in or out of proportion to the proposed work detailed in the specific aims or research strategy. Additionally, regarding the clustering method applied to produce the analyses’ training set, a larger number of clusters could have yielded variation in the types of grants selected as part of the sampling strategy. This number was limited to five to accommodate year-to-year shifts in the types of grants being funded (e.g., before compared to during and then after the COVID-19 pandemic). The sampling size was limited to 800 grants, given the time and resources available for analyses; a larger sampling size could have generated greater variation in the types of grants analyzed. The adjudication process was limited to review of data available on NIH RePORTER, including the grant title, summary, and public health relevance statement, given lack of access to the full contents of the grants themselves.

Many grants were not specific to women’s health but included a focus that was at least partially relevant to women’s health, and so these grants were counted in their entirety as opposed to having their funding allocation divided. For example, a cancer center grant that received funding to study mechanisms underlying multiple cancers, including breast and prostate cancer, was identified as relevant to women’s health without any attempt to divide the allocated funding, given insufficient information available to determine the most appropriate proportions. This issue also applied to grants to study diseases or conditions that affect both women and men and those related to maternal-child health funded to study the health outcomes of both mothers and infants or children. Thus, the overall funding allocated to WHR is likely overestimated by some amount.

In addition, analyses of funding allocated for certain individual diseases and conditions were also limited by the available text content of each grant abstract and, thus, are not considered perfectly accurate. Additionally, in a comprehensive analysis of WHR funding allocation, it would be ideal to understand the geographic and regional distribution (e.g., across states or between rural versus urban communities). This type of analysis was

not possible given the lack of access to the full contents of each funded grant. Many NIH-funded grants awarded to a single primary institution will have portions of the total funding reallocated through subcontracts to other institutions that may be located elsewhere within or even outside of the country. Furthermore, funds allocated to any given institution may be spent to operationalize research in a region or locale that is different from where the institution is located. Thus, future investigations, ideally involving access to additional grant details, are needed to understand geographic and regional distributions of WHR funding allocations. Moreover, because of the absence of an established benchmark for comparison during the validation phase and the limitations of the Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization system and RePORTER search functionality (see Chapter 4), data may not serve as a dependable reference for comparing results and are additional challenges.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

See Chapter 4 for more information on the committee’s results from the funding analysis; supplemental data to the committee’s findings are presented here.

TABLE A-1 National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant Funding and Number of Research Grants Overall and for Women’s Health Research (WHR) by Fiscal Year

| Fiscal Year | WHR Spending (Dollars) |

WHR as Percentage of Total Spending | Total Spending (Dollars) |

Number of WHR Grants | WHR as Percentage of Total Grants | Total Grants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2,551,041,179 | 9.69 | 26,322,140,168 | 6,319 | 9.33 | 67,693 |

| 2014 | 2,606,329,910 | 9.59 | 27,179,627,138 | 6,330 | 9.48 | 66,795 |

| 2015 | 2,477,623,280 | 9.09 | 27,270,999,613 | 6,135 | 9.15 | 67,059 |

| 2016 | 2,590,605,120 | 8.87 | 29,215,998,129 | 6,221 | 9.11 | 68,304 |

| 2017 | 2,804,458,353 | 9.12 | 30,750,611,354 | 6,370 | 9.09 | 70,092 |

| 2018 | 2,962,977,736 | 9.00 | 32,913,199,571 | 6,876 | 8.88 | 77,438 |

| 2019 | 3,180,563,172 | 8.96 | 35,515,754,029 | 7,068 | 9.31 | 75,895 |

| 2020 | 3,087,492,113 | 7.77 | 39,748,192,231 | 6,966 | 8.90 | 78,265 |

| 2021 | 3,548,306,504 | 8.59 | 41,306,576,608 | 7,484 | 9.47 | 79,070 |

| 2022 | 3,779,350,407 | 8.94 | 42,292,623,824 | 7,730 | 9.65 | 80,112 |

| 2023 | 3,430,004,435 | 7.85 | 43,674,286,203 | 7,043 | 8.71 | 80,876 |

TABLE A-2 National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant Spending for Women’s Health Research (WHR) and Other Fiscal Year 2013–2023

| Institute, Center, or Office | WHR Spending (Dollars) | Other Spending (Dollars) | Total Spending (Dollars) | Percentage of Total Spending for WHR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCI | 9,182,200,162 | 48,709,667,749 | 57,891,867,911 | 15.86 |

| NIAID | 4,135,534,926 | 51,386,145,635 | 55,521,680,561 | 7.45 |

| NHLBI | 1,952,137,016 | 32,011,069,773 | 33,963,206,789 | 5.75 |

| NIGMS | 873,642,214 | 28,027,917,693 | 28,901,559,907 | 3.02 |

| NIA | 1,367,788,117 | 25,728,310,478 | 27,096,098,595 | 5.05 |

| NINDS | 600,814,709 | 20,534,221,838 | 21,135,036,547 | 2.84 |

| NIDDK | 1,288,024,755 | 19,833,559,093 | 21,121,583,848 | 6.10 |

| OD | 1,491,406,854 | 18,684,719,009 | 20,176,125,863 | 7.39 |

| NIMH | 1,475,560,092 | 16,515,804,872 | 17,991,364,964 | 8.20 |

| NICHD | 5,270,342,607 | 9,124,361,815 | 14,394,704,422 | 36.61 |

| NIDA | 1,018,554,209 | 11,844,527,785 | 12,863,081,994 | 7.92 |

| NIEHS | 1,409,201,246 | 6,739,308,773 | 8,148,510,019 | 17.29 |

| NCATS | 83,769,184 | 7,779,706,623 | 7,863,475,807 | 1.07 |

| NEI | 80,562,927 | 7,698,808,092 | 7,779,371,019 | 1.04 |

| NIAMS | 588,356,192 | 5,285,813,177 | 5,874,169,369 | 10.02 |

| NHGRI | 173,384,662 | 5,465,946,660 | 5,639,331,322 | 3.07 |

| NIAAA | 486,382,453 | 4,519,041,970 | 5,005,424,423 | 9.72 |

| NIDCD | 62,698,746 | 4,527,141,338 | 4,589,840,084 | 1.37 |

| NLM | 34,088,293 | 4,422,001,832 | 4,456,090,125 | 0.76 |

| NIDCR | 242,622,513 | 4,190,339,076 | 4,432,961,589 | 5.47 |

| NIBIB | 263,202,816 | 4,045,480,301 | 4,308,683,117 | 6.11 |

| NIMHD | 518,831,659 | 3,425,201,726 | 3,944,033,385 | 13.15 |

| NINR | 223,758,399 | 1,285,125,793 | 1,508,884,192 | 14.83 |

| NCCIH | 91,687,619 | 1,186,497,279 | 1,278,184,898 | 7.17 |

| FIC | 98,959,585 | 579,474,031 | 678,433,616 | 14.59 |

| RMOD | 81,465 | 148,006,143 | 148,087,608 | 0.06 |

| CIT | 5,951,248 | 109,201,405 | 115,152,653 | 5.17 |

NOTE: CIT = Center for Information Technology; FIC = Fogarty International Center; NCATS = National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; NCCIH = National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health; NCI = National Cancer Institute; NEI = National Eye Institute; NHGRI = National Human Genome Research Institute; NHLBI = National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIAAA = National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; NIA = National Institute on Aging; NIAID = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NIAMS = National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; NIBIB = National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; NICHD = Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIDA = National Institute on Drug Abuse; NIDCD = National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; NIDCR = National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; NIDDK = National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NIEHS = National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; NIGMS = National Institute of General Medical Sciences; NIMH = National Institute of Mental Health; NIMHD = National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NINDS = National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; NINR = National Institute of Nursing Research; NLM = National Library of Medicine; OD = Office of the Director; RMOD = Road Map/Common Fund.

NOTE: NCI = National Cancer Institute; NHLBI = National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIA = National Institute on Aging; NIAID = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NICHD = Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIDA = National Institute on Drug Abuse; NIDDK = National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NIEHS = National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; NIGMS = National Institute of General Medical Sciences; NIMH = National Institute of Mental Health; NINDS = National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; OD = Office of the Director.

TABLE A-3 Conditions, Diseases, and Terms Used in Step 5 of the Committee’s Funding Analysis to Classify Specific Conditions and Diseases of Interest

| Abortion | Depressive disorders | Lupus | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias | Diabetes | Menopause and perimenopause | Scleroderma |

| Amenorrhea | Dysmenorrhea | Migraines | Sexually transmitted infections |

| Anemia | Dyspareunia | Multiple sclerosis | Sjogren’s syndrome |

| Anxiety disorder | Eating disorders | Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome | Substance misuse disorders |

| Asthma | Endometrial cancer | Osteoarthritis | Temporomandibular joint disorder |

| Autism spectrum disorder | Endometriosis | Osteoporosis | Thyroid cancer |

| Bacterial vaginosis | Female sexual dysfunction | Ovarian cancer | Turner syndrome |

| Breast cancer | Fibroids | Parathyroid cancer | Uterine cancer |

| Breastfeeding and lactation | Fibromyalgia | Pelvic floor disorders | Vaginal cancer |

| Candidiasis | Heart failure | Pelvic inflammatory disease | Violence against women |

| Caregiving research | HIV/AIDS | Polycystic ovary syndrome | Vulvar cancer |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | Hyperthyroid disorders | Postpartum depression | Vulvodynia |

| Cerebrovascular disease | Hypothyroid disorders | Pregnancy | |

| Cervical cancer | Infertility | Premature ovarian failure | |

| Contraception | Interstitial cystitis | Premenstrual syndrome | |

| Coronary heart disease | Irritable bowel syndrome | Pulmonary hypertension | |

| Cystocele | Lung cancer | Rett syndrome |

REFERENCES

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2023a. NIH Almanac: National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/what-we-do/nih-almanac/national-center-complementary-integrative-health-nccih#events (accessed October 17, 2024).

NIH. 2023b. NIH Almanac: National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/what-we-do/nih-almanac/national-institute-minority-health-health-disparities-nimhd (accessed October 17, 2024).

ORWH (Office of Research on Women’s Health). 2023. Report of the Advisory Committee on Research on Women’s Health, fiscal years 2021–2022: Office of Research on Women’s Health and NIH support for research on women’s health. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health.