Summary1

In 1993, Congress passed the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Revitalization Act, a landmark law codifying the importance of including women in research and formally establishing NIH’s Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH). Thirty years later, many questions about women’s health remain unaddressed, women’s health research (WHR) remains underfunded, and breakthroughs to improve health and well-being for half the population in the United States—women and girls—have lagged. This gap is partly attributable to a lack of baseline understanding of basic sex-based differences in physiology and gender-based discriminatory practices that have resulted in a failure to prioritize and fund research into conditions and factors specific to, more common among, or that affect women and girls differently. Girls, women, families, society, and the economy all pay a price for this gap.

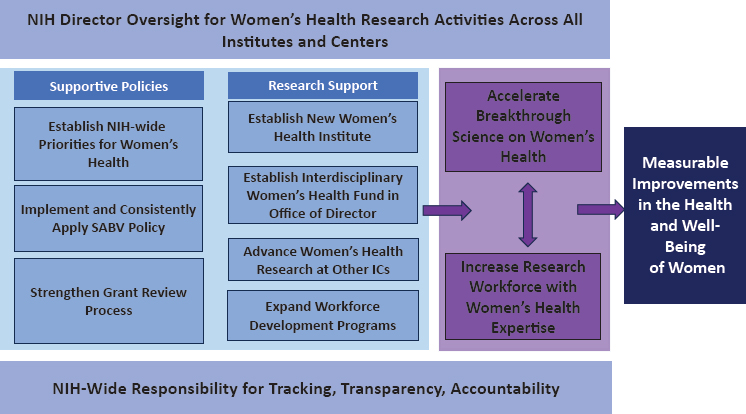

The committee concluded that the nation needs a comprehensive approach to develop a robust WHR agenda and establish a supportive NIH infrastructure. Augmented funding for WHR, while crucial, needs to go hand-in-hand with greater accountability, rigorous oversight, agency-wide prioritization, and seamless integration of WHR across NIH Institutes, Centers, and Offices (ICOs). This multifaceted approach is essential to fully capitalize on both existing and future funding and resources.

___________________

1 This summary does not include references. Citations for the information presented herein are provided in the main text.

WHY STUDY WOMEN’S HEALTH?

There are multiple reasons for the vast gaps in knowledge regarding women’s health prevention, diagnosis, and treatment and the need to prioritize WHR now, including the past exclusion of women in clinical trials arising from concerns about potential risks to fertility and pregnancy; a lack of prioritization of research on women’s physiology, given that the focus of human health research has been adult male anatomy and physiology; and lack of support for and development of the WHR workforce. Although women are now enrolled in clinical trials at the same rate as men overall, underrepresentation of women as research subjects still persists among certain subgroups, and most studies enrolling men and women do not study or analyze sex or gender differences, representing missed opportunities to advance health. Intentionally studying underlying sex and gender differences would lead to stronger science and a better understanding of sex- and gender-specific health issues and interventions that will benefit the health of the whole population.

Despite having a longer life expectancy than men, women spend more years living with a disability and in poor health. On average, a woman will spend 9 years in poor health, 25 percent more time than men, affecting quality of life and productivity. Conditions affecting both women and men have disparities in outcomes and treatment success. For example, although women have a lower prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than men, they have worse prognoses after experiencing an acute cardiovascular event, and research on the underlying pathophysiology of why this occurs is limited. Further, data show a gender disparity in the allocation of NIH research funding across different diseases, with those disproportionately affecting women being underfunded relative to their burden compared to diseases that disproportionately affect men.

Starting in adolescence, there are conditions specific to the experiences of women and girls, and the knowledge gap regarding them fails both women and their health care providers. For example, gynecologic conditions, such as endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and premature ovarian insufficiency, generally require a chronic management approach, yet physicians lack clear guidance and innovative tools to address these costly and debilitating conditions. Significant knowledge gaps exist regarding the health effects of the menopause transition and complications during pregnancy associated with increased risk of developing chronic conditions later in life.

Women who are racially and ethnically minoritized, are economically disadvantaged, live in rural areas, or identify as belonging to sexual and gender minority groups experience a disproportionate burden

of disease and adverse outcomes, including violence, autoimmune diseases, mental illness, maternal morbidity and mortality, and cancer. These inequities are in large part a result of structural factors and lack of access to positive social determinants of health that remain largely understudied and underreported in biomedical research, which is discussed in the report.

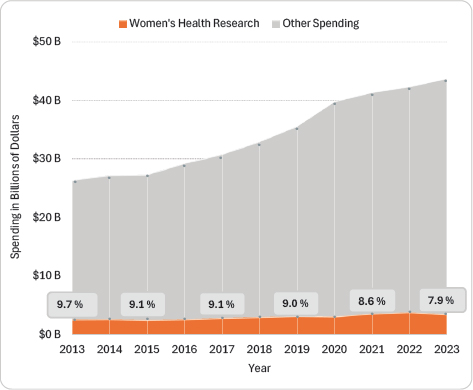

The committee found in its analysis that on average just 8.8 percent of NIH spending from fiscal year (FY) 2013 to FY 2023 across all ICOs focused on WHR, and funding has decreased as a share of overall NIH funding during this period despite steady increases in the NIH budget and total projects (see Figure S-1).

COMMITTEE STATEMENT OF TASK

As part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, Congress requested the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine assemble an ad hoc committee to assess the state of WHR at NIH. ORWH sponsored the study. The committee was asked to assess NIH research on women’s health, including knowledge gaps and the proportion of NIH-funded research on women’s health conditions, including those that are female specific, are more common among women, or affect women differently.

The committee was tasked with providing recommendations regarding the following:

- Research priorities for NIH-supported research on women’s health.

- NIH training and education efforts to build, support, and maintain a robust women’s health research workforce.

- NIH structure (extra- and intramural), systems, and review processes to optimize women’s health research.

- NIH-wide workforce to effectively solicit, review, and support women’s health research.

- Allocation of funding such that NIH women’s health funding reflects the burdens of disease among women.

Women’s Health at NIH

NIH is the largest U.S. government research body, with a budget of $47.1 billion in FY 2024. NIH comprises 21 Institutes and six Centers (ICs), each with its own focus and role to advance biomedical research and public health, and most provide grants to extramural researchers. The purview of most ICs includes aspects of women’s health. For example, most female-specific cancers primarily fall within the scope of the National Cancer Institute. However, many female-specific conditions, such as fibroids, endometriosis, and PCOS, are not prioritized by any specific IC.2

NIH also has offices that support and coordinate various functions across the agency. NIH established ORWH to strengthen research on women’s health conditions, improve representation of women in clinical trials, and increase the number of women in biomedical careers. ORWH is the hub for women’s health at NIH, developing and leading programs and initiatives and directing the development of the NIH-Wide Strategic Plan for Research on the Health of Women. ORWH’s role, however, is largely coordination, and it only has a small budget to co-fund research with ICs.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee identified five steps Congress and NIH should take to advance WHR:

- Create pathways to facilitate and support innovative and transformative research for women’s health;

- Strengthen oversight, prioritization, and coordination for WHR across NIH;

- Expand, train, support, and retain the WHR workforce;

___________________

2 This sentence was changed after release of the report to clarify the scope of NIH ICs.

- Optimize NIH programs and policies to support WHR; and

- Increase NIH investment in WHR.

NOTE: ICs = Institutes and Centers; SABV = sex as a biological variable.

Figure S-2 provides a high-level overview of the committee’s recommendations.

CREATE PATHWAYS TO FACILITATE AND SUPPORT INNOVATIVE AND TRANSFORMATIVE RESEARCH FOR WOMEN’S HEALTH

NIH is underspending on research to support women’s health, leading to significant scientific and clinical gaps on conditions that do not fall within the primary expertise of existing ICs. Furthermore, funding levels for WHR have stagnated and decreased as a share of the NIH budget over the past decade.

NIH Organizational Structure

The organizational structure of NIH limits its ability to effectively address gaps in WHR. ORWH is a small, inadequately funded office without the authority to require ICs to conduct WHR or oversee compliance with the NIH policy on sex differences research. This has left a considerable gap in the coverage of and investment in WHR across the agency. NIH has not provided the level of oversight at the director and IC level to ensure

women’s health is studied comprehensively. Furthermore, many women’s health conditions and women-specific life stages are not prioritized by of any of the 27 existing ICs and remain understudied despite millions of women experiencing the burdens of these conditions.3

Recommendation 1: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should form a new Institute to address the gaps in women’s health research (WHR) and create a new interdisciplinary research fund. Furthermore, NIH leadership should expand its oversight and support for WHR across the Institutes and Center (IC)s. Congress should appropriate additional funding to adequately support these new efforts. Specifically,

1a. Congress should elevate the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) to an Institute with primary responsibility to lead, conduct, and support research on female physiology and chromosomal differences, reproductive milestones across the life course, and female-specific conditions that do not fall under the purview of other ICs.

- Certain programs currently housed in ORWH, such as women’s health workforce development programs, and their corresponding budget will be part of the new WHR Institute.

- The new WHR Institute should have a dedicated independent budget comparable to that of other NIH Institutes with similar scope, amounting to at least $4 billion over the first 5 years.

1b. Congress should establish a new fund for WHR in the Office of the Director to support interdisciplinary women’s health and sex differences research with a focus on innovation and accelerating biomedical discoveries. The fund should have a dedicated independent budget comparable to that of other major NIH initiatives, such as the Common Fund, Cancer Moonshot, and BRAIN Initiative. The fund will ramp up over the first 2 years, achieving full funding of $3 billion in Year 3, with a total investment of $11.4 billion over the initial 5 years.

1c. The NIH director and IC directors should prioritize WHR. The NIH director should assume oversight and responsibility for the WHR portfolio across NIH with respect to funding allocations and implementation of priorities, such as sex as a biological variable, and policies relevant to women’s health. IC directors should increase support for WHR that falls under their purview.

- The NIH director, in collaboration with IC directors, should set annual benchmarks in the year-to-year proportion of extramural and intramural funding to be granted for WHR, following a comprehensive analysis of research needs (see Recommendation 3).

___________________

3 This sentence was updated after release of the report to clarify the scope of NIH ICs.

- The NIH director should evaluate progress on addressing WHR gaps and associated funding levels across NIH and should submit an annual report to Congress and to the public on the year-to-year trends by IC. The Office of the Director should receive additional funds to support NIH-wide programmatic evaluation and increased administrative responsibilities.

- The Director of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) should expand the Institute’s role to include women, girls, and females among the populations that experience disparities. Congress should increase NIMHD’s budget to adequately support including women’s health disparities research into its portfolio and coordinate this research with other ICs.

Implementing Recommendation 1a would require a statutory change by Congress or a reorganization of ICs, since the NIH Reform Act limits the number of NIH ICs to 27. See Chapter 9 (and Table 9-1) on the roles and responsibility of the new WHR Institute.

STRENGTHEN OVERSIGHT, PRIORITIZATION, AND COORDINATION FOR WHR ACROSS NIH

Tracking NIH Investments in WHR

The Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization system—designed to track NIH-funded projects for reporting to the public—is inadequately designed to guide budget allocations and inform Congress and the public on how much is spent in distinct research areas.

Recommendation 2: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should reform its process for tracking and analyzing its investments in research funding to improve accuracy for reporting to Congress and the public on expenditures on women’s health research (WHR).

2a. The new process should improve accuracy of grants coded as Women’s Health and eliminate duplicate or multiplicative counting of grants across Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization (RCDC) categories. This may be achieved by applying proportionate accounting of grants to generate more accurate estimates for categories related to WHR.

2b. NIH should update its process for reviewing, revising, and adding new RCDC categories that pertain to WHR.

2c. NIH should make transparent and accessible the process and data used for portfolio analysis so researchers, analysts, and the public can examine and replicate NIH investments into research for women’s health.

Recommendation 2, and retrospective funding analyses, should be facilitated by expanding the use of modern data analysis methods, such as large language models, that can efficiently identify and categorize grant content.

Priority Setting for WHR

Most NIH ICs have a strategic plan to inform its research priorities—women’s health is rarely mentioned in these plans, and they often do not reflect elements of the NIH-Wide Strategic Plan for Research on the Health of Women. In addition, the time frames for the IC plans vary significantly and do not align with the timeline of the agency-wide plan, limiting NIH’s ability to set, implement, and oversee cohesive and cross-agency priorities for WHR. To address these issues, a comprehensive NIH-wide prioritization process is needed.

Recommendation 3: The Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) should develop and implement a transparent, biennial process to set priorities for women’s health research (WHR). The process should be data driven and include input from the scientific and practitioner communities and the public. Priorities of the director and the Institutes and Centers (ICs) should respond to the gaps in the evidence base and evolving women’s health needs. To inform research priorities for women’s health, NIH should

3a. Employ data-driven methods, such as epidemiologic studies and disability or quality-adjusted life years, to assess the public health effect of conditions that are female specific, disproportionately affect women, or affect women differently. NIH should report this assessment publicly and use it, in combination with other analyses as needed (e.g., of expected return on investment), to identify research priorities and direct funding for WHR.

3b. To ensure priorities for WHR are implemented, ICs should issue Requests for Applications, Notices of Special Interest, Program Announcements, and similar mechanisms, in addition to current funding activities.

EXPAND, TRAIN, SUPPORT, AND RETAIN THE WHR WORKFORCE

To address WHR, a robust and productive NIH intramural and extramural research workforce with broad expertise in biomedical research, clinical trials, and implementation science is essential. NIH support of the WHR workforce falls short of what is needed to address the unmet

needs of women’s health. Investment is needed to develop a cadre of the next generation of women’s health researchers. In addition to intramural and extramural researchers, IC program staff need expertise in women’s health for effective prioritization and coordination. Inadequate funding of WHR has led to an insufficient number of WHR investigators and even fewer with interest and expertise in studying women’s health at the intersection of other important social identities, including race, ethnicity, and disability.

WHR Career Pathways

A coordinated approach is needed to attract and support researchers (those who study WHR, not only researchers who are women) across their careers to make meaningful discoveries in women’s health. Existing grant mechanisms are insufficiently funded and structured to support career trajectories in WHR. Increased funding and expanded numbers of career support grants for WHR investigators are needed, coupled with support for sponsorship, mentorship, and protected research time, such as through training grants. Mentorship and career development are vital to developing a WHR workforce, but NIH grants do not generally fund mentor time. In addition, many institutions do not have the funding to support early-career clinician-scientists, particularly in surgical subspecialties, including obstetrics and gynecology.

Gender-based bias and sexism persist in the United States, including in its health and research systems. For NIH, these biases affect the grant-review and award processes. Bias related to race and ethnicity are independent and intersectional contributors to gaps in health research generally and WHR specifically. NIH has acknowledged these issues and implemented initiatives to address them. However, research suggests that significant disparities remain, and further structural changes are necessary to achieve equity in the grant-making process.

Recommendation 4: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should augment existing and develop new programs to attract researchers and support career pathways for scientists through all stages of the careers of women’s health researchers.

4a. NIH should create a new subcategory within the Loan Repayment Program (LRP) for investigators conducting research in women’s health or sex differences. K awardees who study women’s health or sex differences should be automatically considered for an LRP grant. For every year in the program, awardees should receive loan repayment assistance up to $50,000 for up to 5 years, allowing up to $250,000 in loan repayments.

4b. NIH should create new and expand existing early-career grant mechanisms (K, T, and F grants) that specifically support growing and developing the women’s health research workforce. Appropriate models for new mechanisms are the Stephen I. Katz and Grants for Early Medical/Surgical Specialists’ Transition to Aging Research awards. These grants should prioritize early-career investigators with innovative approaches focused on women’s health.

4c. NIH should create new and expand existing mid-career investigator awards to support and promote the mid-career women’s health research workforce (e.g., K24, R35, U, P, and administrative supplement grants).

4d. NIH should allow financial support of up to 10 percent, as a line-item component, for mentors (primary or designee mentor) on all mentored grants, such as F31, K01, K99, and T32 grants, that support careers of early and midcareer investigators in women’s health and sex differences research.

4e. All early-career mentored institutional K-awards should be supported up to 5 years to increase the likelihood of retaining a workforce to study women’s health.

Expand WHR Workforce Development Programs

Several WHR workforce development programs have been effective at launching and supporting researchers’ careers. However, NIH needs to expand these programs to accelerate growth of the workforce.

Recommendation 5: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should augment existing and develop new grant programs specifically designed to promote interdisciplinary science and career development in areas related to women’s health. NIH should prioritize and promote participation of women and investigators from underrepresented communities.

5a. NIH should double the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) program to achieve a total of 40 centers, with 6 new centers awarded in the next fiscal year and 5 centers each of the following 3 fiscal years. NIH should augment funding for each center to $1.5 million annually, amounting to a total of $60 million per year for the enhanced BIRCWH program.

5b. NIH should expand the Specialized Centers of Research Excellence (SCORE) on Sex Differences program by engaging Institutes and Centers (ICs) to add 5 additional centers to achieve a total of 17 centers over the next 3 to 5 fiscal years. At least three of these centers should reside in the new Women’s Health Research

Institute (see Recommendation 1). The NIH director should provide incentives for other ICs to participate in this program, which could include the provision of matching funds from the Office of the Director. NIH should augment funding for each SCORE to $2.5 million annually, amounting to a total of $42.5 million annually for the enhanced SCORE program, with long-term commitment of funds to renew SCORE programs that meet their goals.

5c. NIH should fund additional multi-project program grants, with or without built-in training components, that focus on women’s health research (e.g., P and U grants) to both expand research on these topics and to support researchers studying women’s health across the career spectrum.

5d. NIH should expand the Women’s Reproductive Health Research (WRHR) program to include 5 additional centers to achieve a total of 20 centers over the next 2 fiscal years. Existing centers that have demonstrated successful metrics should receive funding to host additional scholars. The funding for each center should be augmented to $500,000 annually, amounting to a total of $10 million annually for the enhanced WRHR program.

5e. NIH should expand the Research Scientist Development Program (RSDP) to support 10 scholars with full support, including salary, supplies, and travel, for a total of 5 years amounting to $1.25 million annually for the enhanced RSDP program.

However, any expansion should include new funding to ensure that existing research budgets are not reduced. These programs should be distributed across the country, and grantee institutions should collaborate with other disciplines within their organization to offer mentees a comprehensive and multidisciplinary research experience.

OPTIMIZE NIH PROGRAMS AND POLICIES TO SUPPORT WHR

Peer Review

Representation of women’s health expertise—including of staff in the Center for Scientific Review, IC program officers and council members, and peer reviewers—is essential during the NIH peer review process. Despite progress in this area, special emphasis panels, not standing study sections, evaluate a large proportion of WHR-related grants, indicating that standing study sections lack the required expertise to review such grants. While NIH has been working to improve representation of expertise throughout the grant peer review process, NIH needs to expand these important efforts to accelerate progress.

Recommendation 6: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should continue and strengthen its efforts to ensure balanced representation and appropriate expertise when evaluating grant proposals pertaining to women’s health and sex differences research in the peer review process.

6a. NIH should sustain and broaden its efforts to systematically employ data science methods to identify experts, use professional networks, and recruit recently funded investigators.

6b. The NIH Center for Scientific Review (CSR) should expand the Early-Career Reviewer program to enroll qualified individuals from underrepresented areas of expertise in women’s health and include women’s health, sex differences, and sex as a biological variable training for participants.

6c. CSR should work with NIH-funded institutions to identify qualified individuals with expertise in women’s health. Institutions would provide rosters of trained reviewers to CSR to enrich the pool of reviewers.

6d. In the immediate term, special emphasis panels should be used more often to ensure that applications for women’s health and sex differences research receive expert and appropriate reviews.

Sex as a Biological Variable (SABV) Policy

Addressing the persistent and extensive gaps in knowledge about how conditions disproportionately affect, present in, and progress differently in women requires that SABV be meaningfully factored into research designs, analyses, and reporting in vertebrate animal and human studies. NIH’s SABV policy represents an important advancement, and the number of grants addressing SABV has increased since NIH instituted it. However, overall uptake and application of SABV in practice has not been optimal. This is in part due to a lack of practical, field-specific SABV knowledge and experience among investigators and limited NIH oversight and assurance of implementation. Although guidance and trainings on the SABV policy outline distinctions between sex and gender and indicate in some ways that studies of gender satisfy adherence to the policy, the policy’s language and implementation is not clearly geared toward studies of gender, gender identity, and intersex status. In addition, although SABV is a scorable review criterion in the peer review process, NIH has no cross-agency mechanism for assessing how SABV in grants is evaluated or tracking appropriateness and completeness of SABV implementation.4 Furthermore, grantees face no

___________________

4 This sentence was updated after release of the report to clarify that SABV is a scorable review criterion.

consequences if they do not implement their plans for SABV and are not incentivized to do so.

Recommendation 7: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should revise how it supports and implements its sex as a biological variable (SABV) policy to ensure it fulfills the intended goals. For its intramural and extramural review processes, where applicable:

7a. NIH should expand education and training resources for investigators on how to implement SABV, with separate programs that are more effectively tailored for scientists in distinct fields (e.g., basic, preclinical, clinical, translational, and population research).

7b. NIH should ensure that SABV is consistently and systematically reviewed. Reviewers should be required to undergo training to enable them to assess SABV in proposals and grant applications.

7c. The NIH Center for Scientific Review should, as part of the competitive renewal applications process, include an evaluation of grantee efforts and publications relating to previously proposed studies of SABV as it applies to the project funded in the last cycle, as well as that proposed in the current renewal application.

7d. To strengthen and foster research designed to rigorously examine sex, gender, or gender identity differences aimed at providing new insights into women’s health, that research should:

- Be protected from across-the-board budget cuts to protect the sample sizes and analyses needed to study sex differences.

- Have access to administrative supplements to ensure sex, gender, and gender identity differences can be studied rigorously and with adequate sample size.

- Have priority for funding when such projects fall in the discretionary range of the payline.

- Undergo a streamlined process for requesting higher budgets than those allowed by the program announcement or request for proposal.

7e. NIH should expand the SABV policy in human studies to explicitly factor the effect of biological sex, gender, and gender identity in research designs, analyses, and reporting to promote research on sex and gender diversity, including intersex status, gender expression, and nonbinary-identified populations. This expansion may involve adapting the policy language.5

Although Recommendation 7d would afford a unique status to grants that focus on SABV, the committee believes these actions are needed to incentivize and support investigators to address SABV in a meaningful way.

___________________

5 Recommendation 7 was changed after release of the report to clarify that it applies to both extramural and intramural research.

When sex is completely accounted for in study designs and analyses, the resulting discoveries benefit the entire population. After the study of sex differences becomes more consistently incorporated into NIH-funded research, these protections can be revisited.

PRIORITY RESEARCH AREAS

Given the breadth of conditions that are female specific, are more common in women, or affect women differently, and the need to support innovation for new lines of inquiry over time, the committee does not provide specific priority women’s health conditions to study. Instead, it has identified types of research needed along the research continuum (see Recommendation 8 in Chapter 9). Progress in these domains will advance the field’s understanding of the etiology of multiple conditions. For example:

- Basic research that rigorously assesses hormonal profiles and basic female physiology to understand the mechanisms of biological sex differences in risk factors, disease prevalence, pathology, and progression;

- Preclinical research to understand basic etiology of female-specific and gynecologic chronic conditions;

- Clinical research that collects and analyzes data separately for women and men to identify sex and gender differences in treatment efficacy, side effects, and overall effects, with attention to hormonal, genetic, epigenetic, and metabolic factors that might influence pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and efficacy of drugs and biologic therapies;

- Population-level research that studies how policies at the system, payor, local, state, and national levels affect women’s health and whether these have a disparate effect on women at greater risk for marginalization and poorer health outcomes, including racially and ethnically minoritized women, women with disabilities, sexual and gender minority populations, and those who are low income;

- Implementation science research that develops and tests strategies for implementing innovative health care services delivery approaches, focusing particularly on communities experiencing health disparities; and

- Considerations across the research continuum, such as prioritizing conditions that affect a woman’s quality of life (e.g., depressive disorder, endometriosis, fibroids, irritable bowel syndrome, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, and PCOS), to reduce the amount of time women live with painful or debilitating conditions, as well as conditions that cause early mortality, such as CVD and female-specific cancers.

Research on the role of sex, gender, gender identity, and sex beyond the binary within each type of research will improve health of the whole population by improving understanding of the mechanisms through which these factors play a role in disease prevention, development of health conditions, and treatment outcomes. Within these areas, funding should be allocated by a process like that described in Recommendation 3.

INCREASE NIH INVESTMENT IN WHR

The committee was asked to “determine the appropriate level of funding that is needed to address gaps in women’s health research at NIH” and recommend “the allocation of funding needed to address gaps in women’s health research at NIH.” The committee interpreted this as a request to identify the level of funding necessary to catapult new efforts and bolster existing investments in NIH-supported WHR over the next 5 years and into the future.

Since researchers have barely begun to understand the complexities of sex differences in health and neglected research on many female-specific conditions, including the effect of gender and society on women’s health, the funding needed to bring the WHR knowledge base up to par with that of conditions for which science has contributed to a deep understanding of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment is significant, and the effort will take decades even with appropriate funding.

The committee recommends that Congress appropriate $15.71 billion in new funding over the next 5 years to invest in women’s health and sex differences research and workforce development (see Table S-1). This would approximately double the average NIH annual investment in women’s health ($3.41 billion on average over the past 5 years based on the committee funding analysis), with additional funds needed to cover operational costs, increased oversight by the NIH director, and increased funding for the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

These investments are only a first step. Putting the United States on a path to improve women’s quality of life and decrease morbidity and mortality resulting from conditions that are female specific, are more common in women, or affect women differently requires sustained commitment to WHR, accountability, and integrating and coordinating WHR across all NIH structures and processes. In an ideal world, the nation would invest far more than this amount in the short term, as the need is urgent and the weight of neglecting WHR falls on not only half of the population but society as a whole.

TABLE S-1 New Funding Needed to Accelerate Progress to Fill the Women’s Health Research (WHR) Knowledge Gap

| New Funding (in Millions of Dollars) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Action | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | Total 5-Year Funding (New) | Total 5-Year Funding (New and Existing) |

| New Institute | $800.000 | $800.000 | $800.000 | $800.000 | $800.000 | $4,000.000 | $4,000.000 |

| New Fund | $900.000 | $1,500.000 | $3,000.000 | $3,000.000 | $3,000.000 | $11,400.000 | $11,400.000 |

| Expanded Workforce Programs* | $42.770 | $56.795 | $66.795 | $74.295 | $74.295 | $314.950 | $314.950 |

| Total New Funding | $1,742.770 | $2,356.795 | $3,866.795 | $3,874.295 | $3,874.295 | – | $15,714.950 |

| Existing Research Funding for WHR^ | $3,405.000 | $3,405.000 | $3,405.000 | $3,405.000 | $3,405.000 | – | $17,025.000 |

| Total Funding | $5,147.770 | $5,761.795 | $7,271.795 | $7,279.295 | $7,279.295 | $15,714.950 | $32,739.950 |

NOTES: * Expanded workforce programs are: BIRCWH (Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health), RSDP (Reproductive Scientist Development Program), SCORE (Specialized Centers of Research Excellence on Sex Differences), WRHR (Women’s Reproductive Health Research Career Development Program). ^Existing research funding is the estimated average spending on WHR 2019–2023 based on the committee’s funding analysis and includes the historical workforce investments; assumes no change in years 1 to 5, although this number should increase each year as NIH Institutes and Centers prioritize WHR. New funding calculations are based on Recommendation 5 in this report, with initial ramp up of BIRCWH in years 1 through 4, SCORE in years 1 through 3, and WRHR in years 1 and 2. Current funding for workforce programs was subtracted from the total recommended amount in years 1–5 to calculate expanded workforce program funding.