A New Vision for Women's Health Research: Transformative Change at the National Institutes of Health (2025)

Chapter: 3 Review of National Institutes of Health Structure, Policies, and Programs

3

Review of National Institutes of Health Structure, Policies, and Programs

OVERVIEW OF THE NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH’S STRUCTURE

To elucidate improvements that might be made to advance progress on women’s health research (WHR) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), it is critical to understand the policies, programs, and structures that shape how NIH supports this work. With an annual budget of approximately $48 billion, NIH is the largest and most influential and complex biomedical research sponsor in the world (NIH, n.d.-a). This chapter does not provide a comprehensive overview of NIH but rather focuses on major aspects of NIH’s history, policies, programs, and structures relevant to WHR.

NIH Mission and Goals

NIH’s mission is to “seek fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and the application of that knowledge to enhance health, lengthen life, and reduce illness and disability” (NIH, 2017b). NIH’s goals, and therefore the research it conducts and supports, center around fostering scientific discovery and developing innovative research with high scientific integrity to expand medical and related knowledge to support health (see Box 3-1). To achieve this mission, NIH invests the majority of its budget on basic sciences and clinical research, with almost 83 percent awarded for extramural research. Most extramural research is funded through competitive grants to more than 300,000 researchers at more than 2,700 universities, medical schools, and other research institutions in every state.

BOX 3-1

NIH Goals

- To foster fundamental creative discoveries, innovative research strategies, and their applications as a basis for ultimately protecting and improving health;

- To develop, maintain, and renew scientific human and physical resources that will ensure the nation’s capability to prevent disease;

- To expand the knowledge base in medical and associated sciences in order to enhance the nation’s economic well-being and ensure a continued high return on the public investment in research; and

- To exemplify and promote the highest level of scientific integrity, public accountability, and social responsibility in the conduct of science.

In realizing these goals, NIH provides leadership and direction to programs designed to improve the health of the nation by conducting and supporting research in:

- the causes, diagnosis, prevention, and cure of human diseases;

- the processes of human growth and development;

- the biological effects of environmental contaminants;

- the understanding of mental, addictive and physical disorders; and

- directing programs for the collection, dissemination, and exchange of information in medicine and health, including the development and support of medical libraries and the training of medical librarians and other health information specialists.

SOURCE: Excerpt from NIH, 2017b.

Approximately 11 percent of the NIH budget supports projects conducted by the nearly 6,000 scientists in NIH laboratories. The remaining 6 percent covers research support, administrative, and facility construction, maintenance, or operational costs (Lauer, 2024; NIH, n.d.-a). The fiscal year (FY) 2023 program level was $47.683 billion, with an additional $1.5 billion going to the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health. Each year, through its annual appropriations process, Congress approves the funding for all federal agencies, including NIH. Congress does not generally specify funding amounts for individual health conditions at NIH but instead sets an overall amount for each NIH Institute, Center, and Office (ICO). Each ICO determines how to allocate those funds, though some are earmarked by Congress for specific programs within each ICO (CRS, 2024; Rodgers, 2024).

NIH Organization

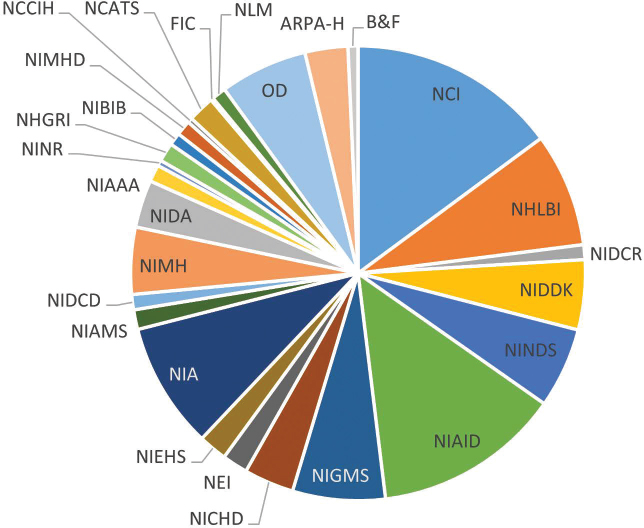

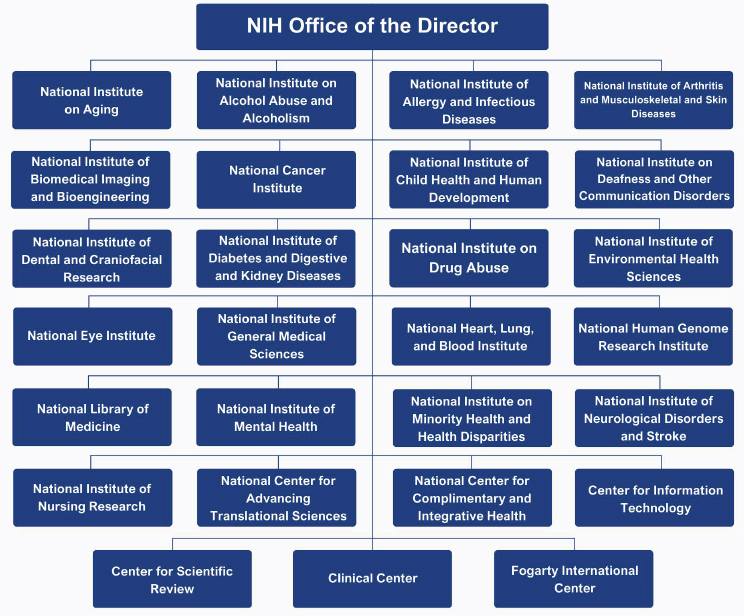

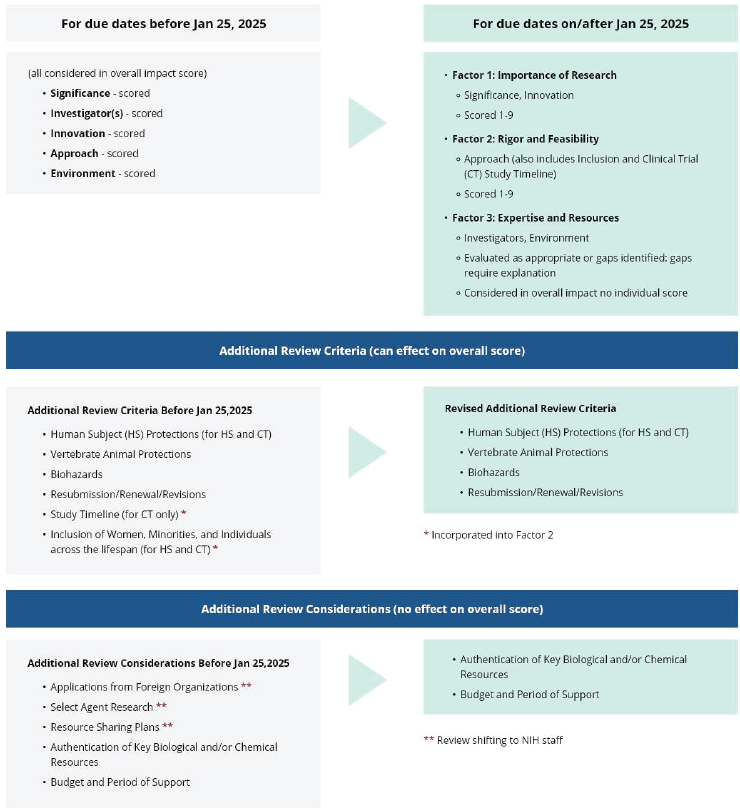

NIH funds research in every U.S. state and a small number of studies in other countries (NIH, 2024d, n.d.-a). Its core revolves around its 21 Institutes and six Centers (ICs) coordinated through its Office of the Director (OD) (NIH, 2023f, 2024g). All the Institutes award and administer grants, while most but not all Centers provide grant funding. For example, the Center for Scientific Review (CSR) coordinates peer review of grant applications but does not provide direct funding to investigators. The Center for Information Technology (CIT) mainly provides computer support services, and the Clinical Center provides clinical services, houses clinical research, and offers training. Other Centers, including the Fogarty International Center (FIC), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), and National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), function like Institutes. Although their budgets are small, these Centers fund research in their areas of interest (NIH, 2023f). The budgets of the ICs vary (see Figure 3-1).

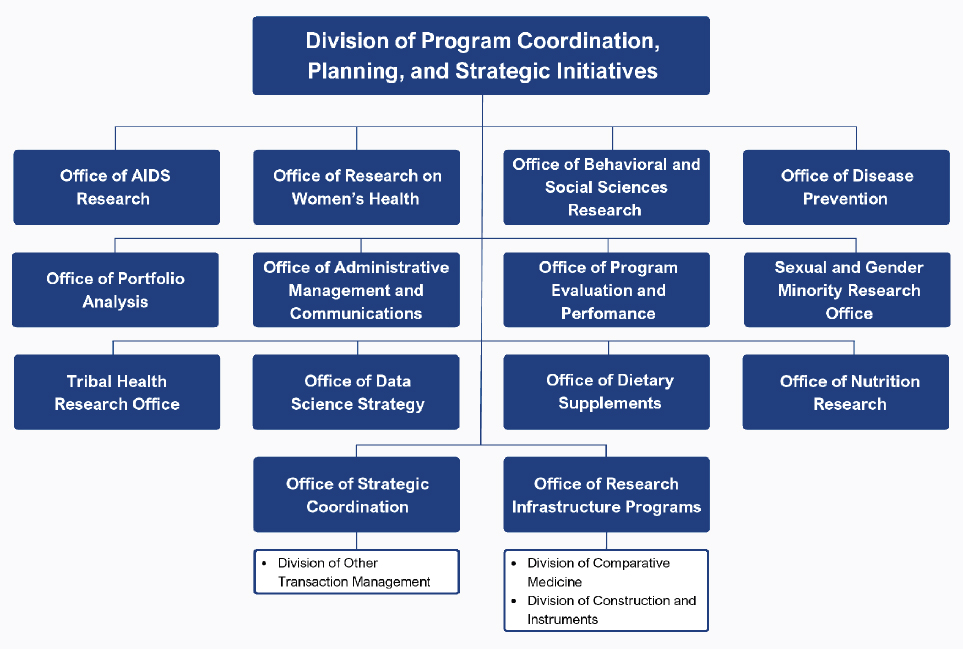

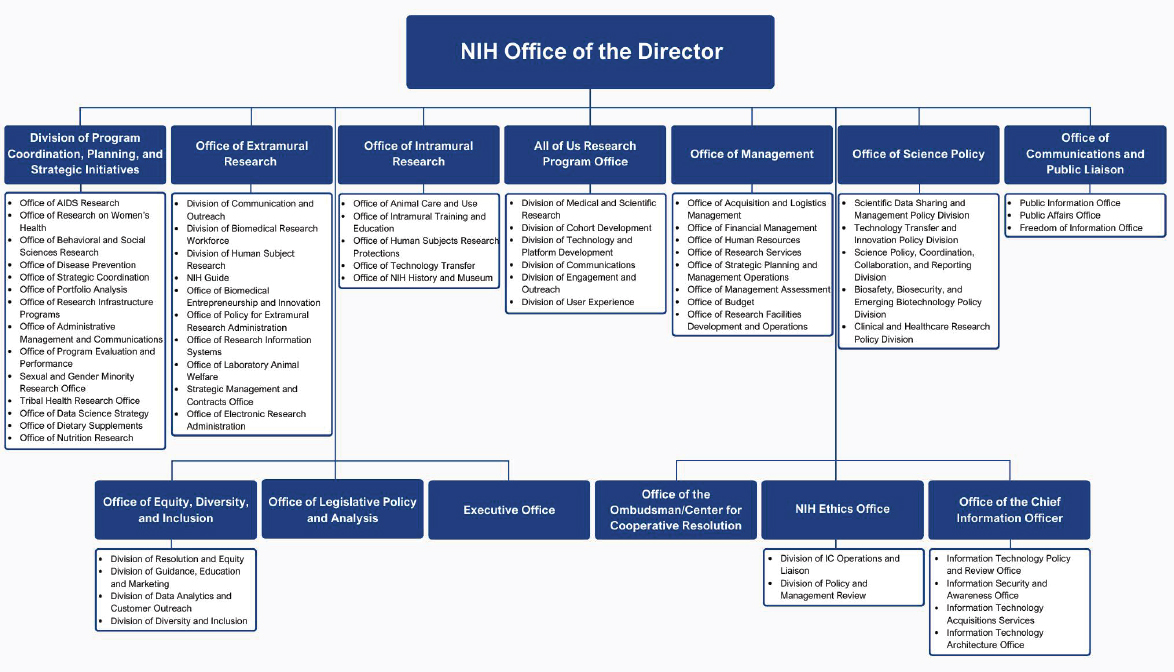

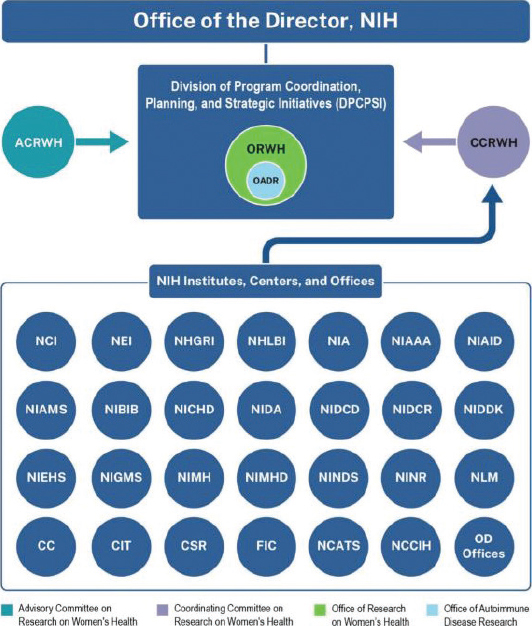

In addition to ICs, the OD oversees about a dozen Offices and the Division of Program Coordination, Planning, and Strategic Initiatives (DPCPSI). Within the OD, DPCPSI oversees several offices, many of which are specifically tasked with broad responsibility for coordinating research across the 27 ICs, for example, the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH), Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR), Office of Disease Prevention (ODP), and Office of AIDS Research (OAR) (NIH, n.d.-c) (see Figure 3-2 for a listing of all offices). These coordinating Offices each have a director and work closely with the directors and staff of the ICs to identify areas of potential collaboration. For example, virtually all ICs fund research relevant to behavioral science, women’s health, and prevention. The coordinating Offices explore the potential for pooling resources, reducing duplication, and stimulating new directions; each director also holds the title of NIH associate director (NIH, 2024f; OAR, n.d.; OBSSR, n.d.; ODP, n.d.-a; ORWH, n.d.-j).

In addition to the coordinating Offices, DPCPSI also oversees several other Offices (see Figure 3-2). A consequence of this structure is that both DPCPSI and the OD (see Figure 3-3) are tasked with the nearly impossible roles of fully supporting the missions of the dozens of Offices they oversee. The complexity of the NIH organization is shown in Figures 3-3 and 3-4.1

Office Budgets

Budgets for select programmatic Offices are shown in Table 3-1. In contrast to ICs, programmatic Offices do not have sufficient funds to support grants independently, nor is that their major role. Office budgets support their mission to initiate the development of collaborative funding that

___________________

1 The section was changed after release of the report to clarify the offices in the NIH OD specifically tasked with research coordination.

NOTE: ARPA-H = Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health; B&F = Buildings and Facilities; FIC = Fogarty International Center; NCATS = National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; NCCIH = National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health; NCI = National Cancer Institute; NEI = National Eye Institute; NHGRI = National Human Genome Research Institute; NHLBI = National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIA = National Institute on Aging; NIAAA = National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; NIAID = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NIAMS = National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; NIBIB = National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; NICHD = Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIDA = National Institute on Drug Abuse; NIDCD = National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; NIDCR = National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; NIDDK = National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NIEHS = National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; NIGMS = National Institute of General Medical Sciences; NIMH = National Institute of Mental Health; NIMHD = National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NINDS = National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; NINR = National Institute of Nursing Research; NLM = National Library of Medicine; OD = Office of the Director.

SOURCE: Data from NIH, 2023a,b.

NOTE: This figure was changed after release of the report to clarify the offices in the NIH OD specifically tasked with research coordination.

SOURCE: Adapted from NIH, n.d.-c.

SOURCE: Adapted from NIH, n.d.-c.

SOURCE: Adapted from OMA, n.d.

TABLE 3-1 Budgets of Select National Institutes of Health Programmatic Offices in Dollars

| Office | Fiscal Year 2023 Budget |

|---|---|

| Office of AIDS Research | $67,587,000 |

| Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research | $40,047,000 |

| Office of Dietary Supplements | $28,500,000 |

| Office of Disease Prevention | $17,873,000 |

| Office of Nutrition Research | $1,313,000 |

| Office of Research Infrastructure Programs | $309,393,000 |

| Office of Research on Women’s Health | $76,648,000 Includes: $10 million for new OADR, $5 million in new funding for BIRCWH, and $2 million for NASEM study. Remainder: $59,648,000 |

NOTE: BIRCWH = Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health; NASEM = National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; OADR = Office of Autoimmune Disease Research.

SOURCE: Data from Clayton, 2023; NIH, n.d.-e.

aligns with the mutual interests and goals of the ICs (NIH, 2024f; OAR, n.d.; OBSSR, n.d.; ODP, n.d.-a; ORWH, n.d.-j).

WHR AT NIH

ORWH

No IC is charged with addressing women’s health, but some women’s health conditions fall within the purview and expertise of the 27 ICs (NIH, 2023f). The task of ORWH is to ensure that the research conducted and supported by the ICs adequately addresses women’s health. As discussed in Chapter 1, NIH created ORWH in 1990 to coordinate and promote research on the health of women, both within and outside the NIH scientific community (ORWH, n.d.-k). Congressional action to address the lack of inclusion of women in NIH-sponsored research, via the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993, was the key impetus for the Office’s creation (ORWH, n.d.-k) (see Box 3-2 for ORWH’s key responsibilities as outlined by Congress). The 21st Century Cures Act,2 signed in 2016, reaffirmed NIH’s commitment to advancing WHR, including by advocating for the importance of considering sex as a biological variable (SABV) in research and ensuring that women, people of all ages, and underrepresented racial and ethnic groups are appropriately represented in clinical research (ORWH, n.d.-k).

ORWH Organization and Funding

ORWH became part of DPCPSI as a result of the NIH Reform Act of 2006.3 DPCPSI coordinates agency-wide initiatives and works to identify emerging scientific opportunities. Thus, it is well suited to oversee the work of ORWH (ORWH, n.d.-k). See Figure 3-5 for a visual contextualizing ORWH’s organizational position within NIH.

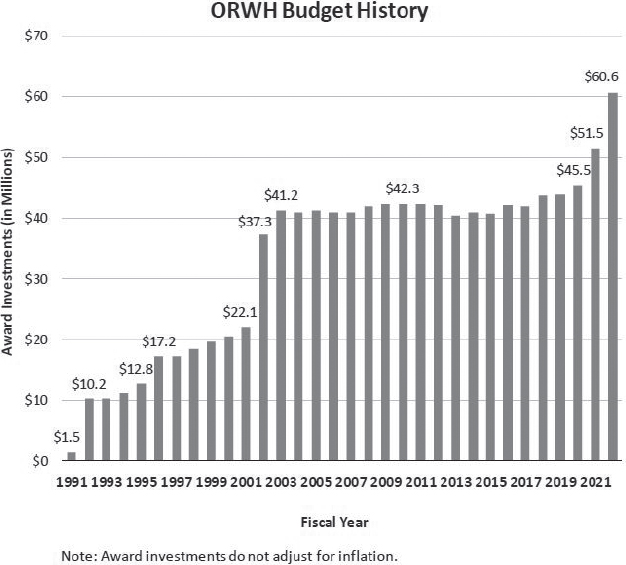

ORWH’s budget increased steadily during its first decade but was stagnant between 2003 and 2020 (see Figure 3-6). The president’s FY 2025 ORWH budget request includes $154 million, an increase of $76 million from FY 2023 and 2024, but as of September 2024, Congress has not yet approved it (OD, n.d.). The additional funds would support research on peri- and postmenopause and diabetes, opioid use disorder in pregnant women, and alcohol use during pregnancy. In addition, NIH plans to create a nationwide network of centers of excellence and innovation in women’s health (OD, n.d.).

___________________

2 Public Law No. 114–255.

3 Public Law No. 109–482.

BOX 3-2

ORWH Mission

Congress assigned a far-reaching leadership role for ORWH by mandating that the ORWH director:

- Advise the NIH director and staff on matters relating to research on women’s health

- Strengthen and enhance research related to diseases, disorders, and conditions that affect women

- Ensure that research conducted and supported by NIH adequately addresses issues regarding women’s health

- Ensure that women are appropriately represented in biomedical and biobehavioral research studies supported by NIH

- Develop opportunities and support for recruitment, retention, reentry, and advancement of women in biomedical careers

- Support and advance rigorous research that is relevant to the health of women

- Ensure NIH-funded research accounts for SABV

ORWH crafts and implements the NIH Strategic Plan for Women’s Health Research in partnership with NIH ICs and co-funds research on the role of sex and gender on health. ORWH also collaborates with NIH ICs, the NIH Office of Extramural Research, and the NIH Office of Intramural Research to monitor adherence to NIH’s inclusion policies, which ensure that women and minorities are represented in NIH-supported clinical research.

ORWH’s interdisciplinary research and career development initiatives stimulate research on sex and gender differences and provide career support to launch promising women’s health researchers. These programs set the stage for improved health for women and their families and career opportunities and advancement for a diverse biomedical workforce.

SOURCE: Excerpt from ORWH, n.d.-j.

ORWH Advisory Groups

ORWH’s work is guided by two advisory groups, both established by Congress as part of the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993: the Advisory Committee on Research on Women’s Health (ACRWH) and the Coordinating Committee on Research on Women’s Health (CCRWH). Both make recommendations on research priorities to ORWH based on their consideration of gaps in knowledge and emerging scientific opportunities (ORWH, n.d.-c,d,i).

NOTE: CC = Clinical Center; CIT = Center for Information Technology; CSR = Center for Scientific Review; FIC = Fogarty International Center; NCATS = National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; NCCIH = National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health; NCI = National Cancer Institute; NEI = National Eye Institute; NHGRI = National Human Genome Research Institute; NHLBI = National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIA = National Institute on Aging; NIAAA = National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; NIAID = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NIAMS = National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; NIBIB = National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; NICHD = Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIDA = National Institute on Drug Abuse; NIDCD = National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; NIDCR = National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; NIDDK = National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NIEHS = National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; NIGMS = National Institute of General Medical Sciences; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NIMH = National Institute of Mental Health; NIMHD = National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NINDS = National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; NINR = National Institute of Nursing Research; NLM = National Library of Medicine; OD = Office of the Director.

SOURCE: ORWH, n.d.-k.

SOURCE: Clayton, 2023.

ACRWH is a Federal Advisory Committee Act committee comprising nonfederal employees and provides advice and recommendations on priority issues affecting women’s health and sex differences research. Its responsibilities include advising the ORWH director on appropriate research activities in women’s health, reviewing the WHR portfolio, assessing scientific career development goals, and evaluating the inclusion of women and minoritized individuals in NIH clinical research. ACRWH meets at least once per fiscal year and produces biennial reports that discuss the NIH-wide programs conducted to fulfill ORWH’s core mission and its accomplishments and highlight research on the health of women and the influence of sex and gender on health and disease (ORWH, n.d.-c,f).

CCRWH comprises IC directors or their designees who serve as liaisons between ORWH and the ICs. It provides guidance, collaboration, and support to ORWH program goals and is a resource for women’s health activities across the agency, including assisting with data collection and the development and expansion of clinical trials to include women (ORWH, n.d.-i).

ORWH Research Areas and Activities

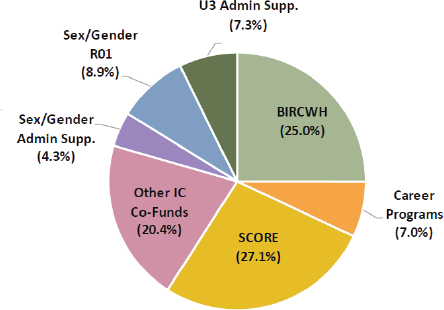

ORWH’s work focuses on several key areas, all aligned with its mission. Only 8.9 percent of the ORWH budget in 2023 was used to support R01 grants in partnership with ICs (Clayton, 2023). Other ORWH investments include (ORWH, n.d.-m) the following:

- The Science of Sex & Gender: ORWH’s activities in this area aim to advance knowledge of how sex and gender influence health and disease.

- Women’s Health Equity and Inclusion: ORWH coordinates, promotes, and supports research to advance women’s health equity and enhance understanding of intersectionality.

- Supporting Women in Biomedical Careers: ORWH funds programs that address the underrepresentation of women in biomedical careers.

Specific ORWH workforce-related programs include (see Chapter 8 for more information on these and other programs) the following:

- The Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health program was established in 2000 to connect scholars who are junior faculty to senior faculty with a shared interest in women’s health and sex differences research (ORWH, n.d.-g).

- The Specialized Centers of Research Excellence on Sex Differences program funds pilot funding, training, and education at NIH-supported centers that serve as research hubs focusing on sex and gender (ORWH, n.d.-r).

Other examples of ORWH activities and initiatives include the following:

- The U3 Administrative Supplement Program provides funding for research focused on intersectionality and health among populations of women that are understudied, underrepresented, and underreported (U3).

- The sex and gender program, started in 2013, offers supplemental funding to NIH grantees to support research on influences of sex and gender (ORWH, n.d.-m). The administrative supplements provide 1-year awards of approximately $100,000, and ORWH has invested $38.87 million since inception, supporting 383 investigators in FY 2013–2021 across ICOs. For FY 2021, ORWH committed $1 million, enough to cover only approximately 10 supplements (Agarwal et al., 2021; ORWH, n.d.-b).

- The Pathways to Prevention program convenes federal agencies, researchers, and community members to identify research gaps in a scientific area of broad public health importance. It also works to develop an action plan to address these gaps (ODP, n.d.-c).

See Figure 3-7 for ORWH’s extramural grant awards by program in 2022.

Office of Autoimmune Disease Research (OADR)

OADR sits within ORWH. Congress created OADR in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 20234 in response to the 2022 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report, Enhancing NIH Research on Autoimmune Disease (NASEM, 2022; ORWH, n.d.-a).5 The Office is charged with evaluating NIH’s autoimmune disease research portfolio and was directed to

- Coordinate development of a multi-IC strategic research plan;

- Identify emerging areas of innovation and research opportunity;

NOTES: ORWH total investments = $43,222,779. Funding portfolio excludes research and development contracts, interagency/intra-agency agreements., and loan repayment awards. BIRCWH = Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health; IC = Institutes and Centers; SCORE = Specialized Centers of Research Excellence on Sex Differences; U3 Admin Supp. = U3 (underrepresented, underserved, and underreported) Administrative Supplement Program.

SOURCE: Clayton, 2023 (based on frozen data from NIH IMPAC II, Fiscal Year 2022).

___________________

4 Public Law 117–328.

5 The report recommended that an office be created in the NIH Office of the Director, not within ORWH.

- Coordinate and foster collaborative research across ICs;

- Annually evaluate the NIH autoimmune disease research (ADR) portfolio;

- Provide resources to support planning, collaboration, and innovation; and

- Develop a publicly accessible central repository for ADR.

To start, the Office is collaborating with leading experts to review NIH-funded research from the past 5 years to create an initial overview of the research portfolio (ORWH, n.d.-a). OADR-ORWH has begun supporting research, such as two multi-year awards for the collaborative Accelerating Medicines Partnership® Autoimmune and Immune-Mediated Diseases (AMP® AIM) program in FY23 and FY24.6 Launched in 2021, the program is managed by the Foundation for the NIH and supported by several ICOs, private partners, and not-for-profit organizations. Its goal is to advance the fields understanding of the cellular and molecular interactions that drive inflammation and autoimmune diseases.7,8

ORWH Policy Oversight

SABV

The SABV Policy, implemented in 2016, requires that “sex as a biological variable will be factored into research designs, analyses, and reporting in vertebrate animals and human studies” and “strong justification from the scientific literature, preliminary data, or other relevant considerations [if] proposing to study only one sex” (NOT-OD-15-103).9 ORWH leads the Trans-NIH SABV Working Group in its efforts to inform policy development and implementation (ORWH, 2021). Greater detail on the policy is provided later in this chapter.

Clinical trial inclusion policies

In the 1993 NIH Revitalization Act, Congress turned an existing NIH inclusion policy into federal law and directed the NIH to establish guidelines for broader inclusion of women and minoritized individuals in clinical research, with requirements including:

- “NIH [should ensure] that women and minorities are included in all human subject research.

___________________

6 For more information, see https://orwh.od.nih.gov/OADR-ORWH/Funding-Information#card-1797 (accessed January 25, 2025).

7 For more information, see https://www.niams.nih.gov/grants-funding/niams-supported-research-programs/accelerating-medicines-partnership-amp (accessed January 25, 2025).

8 This paragraph was updated after release of the report to add the AMP® AIM program as an example.

9 See https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-15-103.html (accessed September 9, 2024).

- Phase III clinical trials [should] include women and minorities in numbers adequate to allow for valid analyses of differences in intervention effects.

- Cost is not allowed as an acceptable reason for excluding these groups.

- NIH [should initiate] programs and support for outreach efforts to recruit and retain women and minorities and their subpopulations as volunteers in clinical studies” (ORWH, n.d.-h).

A 2017 amendment to the NIH inclusion policy adds a “requirement that recipients conducting applicable NIH-defined Phase III clinical trials ensure results of valid analyses by sex/gender, race, and/or ethnicity are submitted to Clinicaltrials.gov” (NIH, 2017a). ORWH supports the NIH inclusion policy by collecting and analyzing data on clinical trial diversity (ORWH, n.d.-h).

NIH-Wide Strategic Plan for Research on the Health of Women

In May 2024, NIH released its NIH-Wide Strategic Plan for Research on the Health of Women 2024–2028, which ORWH led in collaboration with ACRWH, ICO representatives, and federal partners (ORWH, 2024, n.d.-k). The plan includes agency-wide strategic goals and objectives in the areas of “biological, behavioral, social, structural, and environmental factors; data science and data management practices; scientific workforce training and education; biology underlying sex influences; and community-engaged science across the research and practice continuum” (ORWH, n.d.-k, p. 4).

The NIH strategic plan places importance on both sex and gender in research. Guiding principles for the plan include “consider[ing] the complex intersection among multiple factors that affect the health of women, includ[ing] diverse populations of women in clinical research, and integrat[ing] perspectives from a diverse workforce of scientists with differing skills, knowledge and experience” (ORWH, n.d.-k, p. 9). Strategic goals outlined in the plan include the following:

- “Research: Advance research that examines the multiple biological, behavioral, social, structural, and environmental factors that influence the health of women, as well as the intersections of these factors” (ORWH, n.d.-k, p. 13).

- “Data science and management: Improve data science and data management practices with innovative research methods, measurements, and cutting-edge technologies to prevent and treat conditions affecting women” (ORWH, n.d.-k, p. 14).

- “Training and education: Foster women scientists’ career development and promote scientific workforce training and education that advances the health of women and the science of sex and gender influences” (ORWH, n.d.-k, p. 15).

- “Basic and translational science: Support the basic and translational study of the biology underlying sex influences and its intersection with disease and health preservation in women across the life course” (ORWH, n.d.-k, p. 16).

- “Community engagement: Advance community-engaged science across the research and practice continuum and enhance the dissemination and implementation of evidence-based solutions to improve the health of women” (ORWH, n.d.-k, p. 17).

Role of ICOs in WHR

Most ICOs have an important role in advancing WHR. For example, reproductive health and pregnancy fall under the purview of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), while issues affecting lesbian and bisexual women, nonbinary and transgender individuals assigned female at birth, or transgender women are under the Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office (SGMRO) (NICHD, 2021; SGMRO, 2024). Issues specific to American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) women fall under the purview of the NIH Tribal Health Research Office (THRO), which serves as the hub for coordination of tribal health–related activities across NIH (THRO, 2023). Specific conditions, such as breast, uterine, endometrial and cervical cancers, are under the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the menopause transition is under the National Institute on Aging (NIA) (NCI, n.d.-a; NIA, 2022). However, many women’s health conditions, such as endometriosis, fibroids, pelvic floor disorders, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and vulvodynia, are not prioritized by ICs based on a review of IC strategic plans as well as low levels of funding for these conditions from 2013–2023 (see Chapter 4).10 Collaboration across NIH ICOs is therefore critical to ensure that WHR is being addressed fully and comprehensively. While ORWH is tasked with coordinating women’s health across NIH Institutes, coordinating across ICOs presents a significant strategic challenge (ORWH, n.d.-k). This section highlights the role of SGMRO, THRO, and two ICs—National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) and NICHD—given their unique roles for advancing various aspects of women’s health, followed by an overview of IC strategic planning for women’s health and sex differences research.

SGMRO

Similarly to ORWH, SGMRO coordinates research across NIH related to sexual and gender minorities (SGM), including individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, transgender, Two-Spirit, queer, or intersex

___________________

10 This sentence was changed after release of the report to clarify the scope of NIH ICs.

(SGMRO, 2024). Therefore, issues specific to SGM women fall under its umbrella. While speaking at one of the committee’s information-gathering meetings, its director highlighted the following as challenges for it and women’s health: scant research focusing on SGM women; inadequate and inaccurate data collection on sexual orientation, gender identity, and sex characteristics; the SABV policy’s treatment of sex as binary; the NIH inclusion policy’s treatment of gender as binary; and the marginalization of SGM women in STEM fields and the health science workforce (NASEM, 2024b; Parker, 2024b).

NIMHD

NIMHD has been a leader in increasing the scientific community’s focus on nonbiological factors, such as socioeconomics, politics, discrimination, culture, and environment, in relation to health disparities. NIMHD has added several populations to its purview since its creation, including those defined by disability, rurality, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, and gender identity with a focus on gender minorities (NIH, 2023g; NIMHD, 2024a; Pérez-Stable, 2024). In addition to research on women and girls within racially and ethnically minoritized, disability, and lower socioeconomic status groups, the addition of SGM, in particular, demonstrate a focus on subpopulations included within WHR frameworks through research on cisgender lesbian and bisexual women, nonbinary and transgender people assigned female at birth, and transgender women. Though women and girls are not a minority group in the United States, they experience well-documented discrimination, bias, and subjugation that are root causes of health disparities and reduced health care access (see Chapter 6). Women’s health concerns are minoritized in terms of treatment in society and corresponding allocation of research funds to understand and improve their health. Based on the committee’s funding analysis, NIMHD spent 13 percent of its grant funding on WHR 2013–2023 (see Chapter 4).

NIMHD is the most likely IC to fund research on minoritized women and research centering these groups, but based on input from researchers who spoke at the committee’s information-gathering meetings and submitted input in writing and the experience of committee members, grants examining women or pregnant women submitted to NIMHD will often be transferred to NICHD for peer review in study section. While it is unclear how often this is the case, based on the committee’s funding analysis, NICHD funds the majority of maternal-child health grants. Studying women, pregnancy, and minoritized populations each pose different methodological challenges and considerations; increased capacity at both NIMHD and NICHD would improve the evaluation of studies at the intersection of these topics. Where reviewers with expertise in both areas cannot be recruited, recruiting more than one, each with the respective expertise, is critical.

NICHD

NICHD’s mission is to lead research and training to “understand human development, improve reproductive health, enhance the lives of children and adolescents, and optimize abilities for all” (NICHD, 2019). Its priorities are reproduction, pregnancy, child health, and pregnant and lactating women, children, and people with disabilities (NICHD, 2021). The health of women before or after pregnancy and sex differences do not easily fall within the purview of these stated objectives. In 1993, the NIH Revitalization Act (Public Law 103–43) mandated the establishment of an intramural laboratory and clinical research program on obstetrics and gynecology at NICHD and, in 2000, gynecologic health was added to its description of purpose (Public Law 106–554). In 2012, NICHD added its Gynecologic Health and Disease Branch (GHDB), to support “basic, translational, and clinical research programs related to gynecologic health throughout the reproductive lifespan,” including conditions such as menstrual disorders, uterine fibroids, endometriosis, adenomyosis, ovarian cysts, PCOS, and pelvic floor disorders, as well as gynecologic pain syndromes such as chronic pelvic pain, vulvodynia, and dysmenorrhea (NICHD, 2018). GHDB supports this work through its research programs on Menstruation and Menstrual Disorders, Uterine Fibroids, Endometriosis and Adenomyosis, Pelvic Floor Disorders, and Gynecological Pain Syndromes, and through additional programs such as the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, established in 2001 to spur collaborative research and improve patient care (NICHD, 2023a, 2024c). Endometriosis research is stated as an NICHD “aspirational goal,” though this is a multisystem disease that requires additional funding and scientific inquiry (NICHD, n.d.). One mechanism through which NICHD has made progress on this goal is Centers to Advance Research in Endometriosis, which support synergistic research programs on endometriosis that span basic, translational, and human subjects research (RFA-HD-21-002).

Based on its review, the committee found that NICHD focuses primarily on women’s health as a mechanism to produce healthy offspring. However, not all women experience pregnancy, and even for those who do, it is a relatively brief phase in the context of an average woman’s life-span. Many health conditions experienced during pregnancy have implications for health later in life (see Chapters 5 and 7). Based on the committee’s funding analysis (see Chapter 4), NICHD allocated 37 percent of its grant funding on WHR at NIH from FY 2013 to 2023, with nearly 69 percent of that funding going to maternal-child health studies, where women were involved in the studies, but the study design tended to include at least some or more focus on fetal, infant, or child health outcomes.

Another mechanism through which NICHD supports women’s health is the Implementing a Maternal Health and Pregnancy Outcomes Vision for Everyone (IMPROVE) initiative, which aims to address key causes of

maternal morbidity and mortality, including cardiovascular disease, hypertension, hemorrhage, mental health disorders, substance use, and infectious disease. In FY23, IMPROVE awarded $43.4 million in funding, including $30 million in support from NICHD plus $13.4 million from other Institutes and Centers (NICHD, 2023b).11

Tribal Health Research Office (THRO)

NIH established THRO in 2015 to “ensure meaningful input from and collaboration with Tribal Nations on NIH policies, programs, and priorities.” THRO serves as the hub for coordination of tribal health–related activities across NIH and as the main point of contact at NIH for federally recognized AIAN tribes (THRO, 2023). It provides a unique opportunity to meaningfully collaborate with and receive input from Tribal Nations on WHR, enabling tribal consultation, incorporation of Indigenous SDOH (see Chapter 6), and ethical conduct of research with Tribal Nations. One specific example of needed coordination is to address barriers to inclusion in grants and workforce development. Due to the rurality of many Tribal Nations, their public health workforce includes community health workers, doulas, early childhood home visitors, and other paraprofessionals. To effectively build the WHR workforce, it is essential to involve these experts in NIH-funded initiatives. In addition, tribal colleges and universities are an important career pathway for many (especially rural) AIAN youth in the trajectory to becoming a health researcher, and ICs could work with THRO to ensure outreach and inclusion.

Women’s Health in IC Strategic Plans

Most ICs develop strategic plans that outline their goals and priorities. For the most part, these plans lack a strong emphasis on women’s health. A possible reason is that individual ICs, which are mainly organized by body systems and diseases or conditions, tend to focus on their specific areas of research and may fail to integrate women’s health as a crosscutting theme (NIH, 2023f). While ORWH collaborates with ICs to coordinate WHR across the organization, the committee’s review of the integration of and attention to WHR into the strategic plans of these Institutes found it to be inconsistent and sparse, failing to comprehensively address the gaps in WHR (ORWH, n.d.-j).

___________________

11 This section was changed after release of the report to make corrections and clarifications on the scope of NICHD’s stated objectives, clarify information on statutes affecting NICHD research activities and changes in NICHD organizational structure, and update/add descriptions of example programs.

Positive Examples

Overall, the IC strategic plans do not demonstrate prioritization of women’s health. However, some Institutes have set significant goals regarding women’s health and sex differences research; this section highlights a few.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) 2022–2026 strategic plan notes that women become addicted to substances more quickly than men, have comorbid mental illness more often, and respond differently to treatments (NIDA, 2022). As one of its crosscutting priorities, it emphasizes the need to understand sex differences in addiction and translate these findings into treatments tailored to women and also consider the unique experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals who are marginalized because of their gender identity or sexual orientation and at greater risk of substance use because of discrimination and other stressors (NIDA, 2022).

One of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) 2024–2028 strategic goals is to advance research related to women’s health. Its strategic plan highlights the importance of understanding the effects of sex on the development of alcohol use disorder and co-occurring mental health conditions, including the mechanisms of these effects and the relationship between alcohol misuse and common comorbidities. The plan acknowledges that women face higher risk of developing certain alcohol-related diseases, such as alcohol-associated liver disease and alcohol-related heart disease and sets goals to evaluate and adapt screening and support services to understudied populations, including women. The plan specifies collaboration with ORWH and other partners across NIH to advance integrated WHR (NIAAA, n.d.-b).12

In its 2020–2025 strategic plan, NIA specifically aims to support research on women’s health, including sex and gender differences in health and disease overall, cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, and topics unique to women. The plan notes the Institute’s support of a diverse portfolio of research on aging women, including studying sex differences in the basic biology of aging and hormonal influences on cognitive health and age-related diseases more common in women, such as osteoporosis, breast and ovarian cancer, and urinary tract dysfunction. The plan includes specific initiatives and goals focused on women’s health, including a commitment to ensure women are fully represented in research and track, monitor, and report on adherence to the SABV policy. Surprisingly, however, the plan mentions menopause only three times, despite this being a significant aging-related concern for half the U.S. population (NIA, 2024).

___________________

12 This paragraph was changed after release of the report to clarify the scope of the NIAAA strategic goals.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) strategic plan includes a number of strategic goals related to women’s health and sex and gender in research (the plan does not cover a specified period). These include improving the representation of women in clinical research, ensuring the applicability of findings to them, and elucidating and further investigating the various factors and environmental, genetic, epigenetic, molecular, cellular, and systemic mechanisms responsible for sex differences in heart, lung, blood, and sleep health and disease (NHLBI, n.d.-a,b).

NICHD is among those ICs that do emphasize women’s health, though primarily reproductive health. Its 2020 strategic plan spells out the goal of advancing the understanding and treatment of health conditions and aspects of reproduction unique to women, such as pregnancy and menstruation. NICHD’s approach includes supporting research on the health of women and girls, focusing on infertility for both men and women, pregnancy, childbirth, lactation, and the postpartum period (NICHD, n.d.).

Overall Lack of Prioritization of Women’s Health

Surprisingly, of the 24 IC strategic plans (CIT does not have a published strategic plan, NCI has strategic priorities, and NIAID has strategic plans for 7 specific diseases/vaccines but not NIAID overall), only NIMH, National Eye Institute (NEI), National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), NIMHD, and NIAAA explicitly mention collaboration with ORWH (NEI, n.d.; NIAAA, n.d.-b; NIAMS, n.d.; NIMH, 2024; NIMHD, 2024b). ORWH itself has an NIH-Wide Strategic Plan for Research on the Health of Women 2024–2028. This plan aims to, among other goals, integrate women’s health across the biomedical research enterprise and develop a workforce that advances research on women’s health and the science of sex and gender (ORWH, n.d.-k).

The SABV policy, which is meant to be applied to human and animal studies across NIH, is specifically mentioned by name in only 5 of the 24 strategic plans (NIA, NIMH, NEI, NIAMS, and NCCIH) (NCCIH, 2021; NEI, n.d.; NIA, 2024; NIAMS, n.d.; NIMH, 2024). The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences’ draft strategic plan for FY 2025–2029 also emphasizes the importance of research that benefits the health of all people across the life-span, including through consideration of SABV and collaboration with ORWH, though its previous 2018-2023 strategic plan did not (NIEHS, n.d.-a,b).

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) strategic plan acknowledges the importance of health equity for all groups, including all sexes and genders, but women specifically are mentioned only once, in relation to migraines (NINDS, n.d.). Similarly, the National Library

of Medicine emphasizes the significance of addressing health disparities, including those based on sex and gender, but otherwise makes no mention of women (NLM, n.d.). NCATS makes no mention of women, sex, or gender, except in relation to workforce in its 2016 strategic plan; its May 2024 plan generally mentions women, however women and sex differences are not specifically mentioned in its strategic objectives (NCATS, 2016, 2024a).13

Overall, the picture is inconsistent, with some ICs giving greater importance to the subject than others. Although many ICs support research aimed at understanding sex differences in the development and progression of various diseases, not all of them have strategic priorities related to women’s health. As a result, integrating it into the broader NIH strategic plans remains limited. This can be attributed to a variety of factors, including historical research biases, funding priorities, and the specific missions of the different NIH ICs, which may not always align with the goals of ORWH. The committee’s review of these strategic plans suggests the need for more comprehensive and coordinated efforts across NIH to address these issues uniformly.

NIH-Wide Strategic Plan

Per the 21st Century Cures Act, NIH updates its strategic plan every 5 years. The most recent iteration is for FY 2021–2025. “The Strategic Plan outlines NIH’s vision for biomedical research direction, capacity, and stewardship, by articulating the highest priorities of NIH over the next 5 years” and is designed to complement and harmonize the IC strategic plans (NIH, 2021a). Although enhancing women’s health is one of the five crosscutting themes in the framework of the plan, it does not offer much in terms of strategic priorities to address gaps in WHR. It discusses efforts around addressing institutional and environmental barriers that restrict women’s potential to advance their careers, some specific ongoing programs and initiatives related to maternal health, including women in clinical trials, and mentions the SABV policy. It has four “bold predictions” or ambitious goals for its 5-year period related to women’s health specifically:

- Research on new approaches to cervical cancer screening will lead to developing self-sampling,14 with the potential to substantially reduce disease incidence and mortality.

- At least one novel, nonhormonal pharmacologic treatment for endometriosis will be identified and moved to clinical trials.

- U.S. maternal deaths per year will be significantly decreased,

___________________

13 This sentence was changed after release of the report to include information from the NCATS strategic plan released in May 2024.

14 Progress has been made on this—in May 2024, the Food and Drug Administration approved a primary human papillomavirus self-collection for cervical cancer screening in a health care setting (American Cancer Society, 2024).

- particularly among Black and AIAN women, by implementing results of research studies focusing on links between social determinants and biological risk factors.

- Following findings of the Task Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women showing that almost no data exist on medications in these women, label changes will be facilitated by results of clinical trials for at least three therapeutics specific to pregnant and lactating women and children (NIH, 2021b).

While these predictions are important aspirations for women’s health, no accompanying steps lay out how these goals will be accomplished.

Does the Current Structure of NIH Serve the Needs for WHR?

The committee considered whether the current organizational structure is adequate to address the pressing need for high-quality WHR. Today, no IC focuses exclusively on WHR. However, it is part of the portfolio of many different ICs. As noted, coordination of research across the 27 ICs is the responsibility of ORWH. As part of its charge, the committee needed to determine whether ORWH has the budget, staffing, and political clout to assure that NIH demonstrates global leadership in WHR.

The committee heard from a wide range of experts from the WHR community during its information-gathering meetings. It also heard testimony from a range of scientific, clinical, and community leaders. One particularly important session featured several NIH grantees.15 One is studying scientific and clinical challenges associated with uterine fibroids. A second works on endometriosis, and a third focuses on pelvic floor disorders (NASEM, 2024c). Although each of these three problem areas is a central area of investigation in WHR, the grant applications are likely to be evaluated in different study sections in peer review, and the grants may be administered by different ICs. While studies on endometriosis and fibroids are likely to be funded by NICHD, studies on pelvic floor disorders are more likely to be funded through the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (NICHD, 2021; NIDDK, 2024b). In addition, these conditions all received low levels of grant funding from 2013–2023 (see Chapter 4) and have significant research gaps (see Chapter 7).16

Therefore, one concern is that these ICs, although committed to high-quality research involving women, do not necessarily have women’s health as a core component of their strategic plans. The studies on pelvic floor disorders, for example, go to an Institute that manages priorities in not only kidney and urological diseases, but also endocrinology, metabolism, and

___________________

15 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/41979_03-2024_assessment-of-nih-research-on-womens-health-meeting-3 for more information (accessed June 15, 2024).

16 This sentence was changed after release of the report to clarify the scope of NIH ICs.

digestive diseases. Furthermore, urology is largely separate from urogynecology; while there are some overlapping conditions involving incontinence and other urinary symptoms, urology does not cover all urogynecological conditions (Rajan et al., 2007). Additionally, review of NIDDK’s National Advisory Council revealed that none of its 12 health and science experts appears to focus on WHR (NIDDK, 2024a). Studies on pelvic floor disorders are not likely to be prioritized or reviewed adequately under a strategic plan with no specific mention of urogynecology and by an advisory council with no related expertise (NIDDK, 2021).

NICHD has the greatest proportion of funding for WHR among the NIH ICs (see Chapter 4). However, its emphasis does not include the entire range of issues in women’s health. The NICHD Strategic Plan emphasizes “healthy pregnancies, healthy children, healthy and optimal lives” (NICHD, n.d.). The 18-person National Advisory Child Health and Human Development Council includes six members who appear to specialize in WHR, with a heavy focus on pregnancy (NICHD, 2024a).

Problems with NIH Programmatic Offices

DPCPSI houses 14 Offices, four of which have responsibility for coordinating programs across ICs; OBSSR, ODP, OAR, and ORWH coordinate and support research in behavioral and social sciences, prevention research, HIV/AIDS research, and women’s health (DPCPSI, n.d.). Theoretically, the coordinating Offices can help avoid duplication, stimulate synergy, and encourage innovation. In practice, that potential may not have been realized. Through presentations from NIH and other experts at the committee’s information-gathering meetings, several explanations for these shortcomings surfaced, including their low budgets, limited authority, and reporting structure.

Low budgets and limited authority

Table 3-1 shows the budgets for select programmatic Offices. Although these budgets have grown in recent years, they are insufficient for funding research relevant to their missions (NIH, n.d.-d,e). Rather, their role is more to coordinate and support research and policies in their given area across NIH. For example, although ORWH has the largest budget among the coordinating Offices, it still functions primarily to coordinate WHR across ICs, facilitate implementation of the SABV policy, and engage in other supportive work (see earlier in this chapter for more information). ORWH and OAR have external advisory councils, but OBSSR and ODP do not (OAR, 2024; ORWH, n.d.-d). Although ORWH cofunds women’s health–related applications and research projects with ICs, its budget and infrastructure are insufficient to administer grants independently without an IC partner (Clayton, 2023). Actual funding of research on women’s health

therefore depends primarily on ICs with a range of other priorities, which may explain why only 8.8 percent (based on the committee’s analysis, see Chapter 4) of NIH research expenditure is spent on WHR.

The committee considered these factors when assessing what is needed to confront the challenges of WHR under the NIH structure. ORWH’s limited resources and inability to fund research independent of existing ICs or administer a women’s health study section pose a barrier to addressing these challenges. The ORWH strategic plan, although laudable, has not been executed by NIH across its many ICs in a way that successfully addresses the pressing demand for more and better-coordinated research relevant to women and girls within its current structure.

Since the 2006 NIH reauthorization, the NIH structure has been relatively unchanged, in part because the number of ICs is fixed in statute.17 This is in contrast to an organizational structure that had flexibly responded to new challenges for over a century. The following section briefly addresses the history of NIH as it is relevant to the committee’s recommendations.

The Evolution of NIH

The roots of NIH date back to 1887, when a one-room laboratory was established as part of the Marine Hospital Service providing medical care to merchant seamen. Congress asked it to take responsibility for examining itinerant sailors who might be vectors for infectious diseases, such as cholera and yellow fever. By 1912, it became part of the Public Health Service. It had a relatively limited mission until the middle of the 20th century, when it evolved into NIH. In 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated a building in Bethesda, Maryland, to house it (Kaplan et al., 2017).

In the years leading up to World War II, an influential academic engineer, Vannaver Bush, made an impassioned plea for the United States to make major investments in original research. Following the war, Bush published a report entitled Science: The Endless Frontier. It argued that massive investments in basic and applied research were needed to establish the United States as the world leader in science and technology (Bush, 1945). The vision included transforming leading universities into research-intensive institutions that would reward faculty research productivity. To make this transformation attractive, universities would receive substantial overhead payments that they could use to build laboratories and support infrastructure services, including university libraries (Kaplan et al., 2017). This approach continues at NIH today (UMR, 2024).

NIH has evolved, regularly modifying its organizational structure to reflect changes in science and clinical practice. In 1948, it created Institutes for heart disease, dentistry, and microbiology. NIMH was founded in 1949,

___________________

17 Public Law 109–482.

and new Institutes on diabetes and stroke were established in 1950 (Kaplan et al., 2017).

Between 1950 and about 2005, NIH was continually reorganizing in response to evolving scientific directions and societal demands. For example, in 1971, President Richard Nixon declared a war on cancer. The resulting National Cancer Act allowed a redistribution of NIH funds that shifted some resources away from other areas of investigation. To this day, NCI has greater power and resources in relation to the other Institutes (Kaplan et al., 2017).

The HIV epidemic led to considerable public pressure for an expansion of NIH funding. Influential groups of citizens and scientists persuaded Congress that greater NIH research was essential (IOM, 1991; Padamsee, 2018). Without this research, the United States would be at a strategic disadvantage in relation to rival nations. Between 1999 and 2002, the NIH budget nearly doubled (Kaplan et al., 2017). Overall, it has increased fourfold over the past 30 years (CRS, 2024).

NIMH has been in and out of NIH over the past 80 years. It separated from NIH in 1967 and became a component of the Health Services and Mental Health Administration. By the 1970s, a serious concern about an epidemic of recreational drug use caused Congress to authorize NIDA within NIMH. A year later, NIMH briefly rejoined NIH but exited again to become part of the new Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration (Kaplan et al., 2017). The Hughes Act of 1970 paved the way for NIAAA to be a component of NIMH (NIAAA, n.d.-a). In 1992, NIMH moved back to NIH, and NIDA and NIAAA were spun off as separate Institutes (Kaplan et al., 2017).

NIMHD evolved as well—it did not start as an Institute. In 1990, the Office of Minority Programs was established in the NIH OD, and in 1993, the Health Revitalization Act established the Office of Research on Minority Health.18 In 2000, the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities was established; it was redesignated as an Institute in 2010, as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,19 due to decades of work to bring attention to the unequal burden of illness and death experienced by certain U.S. populations (NIH, 2010; NIMHD, 2024a).

This detour into history reveals that NIH has a long tradition of reorganizing in response to scientific and societal needs. However, the NIH Reform Act of 200620 set 27 as NIH’s maximum number of national ICs; the Secretary of HHS has the authority to add or remove an IC as long as they stay within the limit. It was not clear to the committee that a fixed

___________________

18 Public Law 103–143.

19 Public Law 111–148.

20 Public Law 109–482.

organizational structure is in the best interest of science and society. With this in mind, the committee reviewed NIH programs, structures, and funding to determine how to best to support WHR at NIH (see Chapter 9 for the committee’s recommendations).

Summary of WHR at NIH

No clear comprehensive approach to strategic planning or evaluating progress in WHR exists across NIH and between individual ICs. Each IC has its own individual and unique approach to women’s health and focus on specific disease processes relevant to that content area. Moreover, the IC strategic plans cover different time frames that often do not align with the NIH-Wide Strategic Plan for Research on the Health of Women. This decentralized approach poses a significant barrier to generating research that will improve the health of women throughout the life-span and tracking progress in any given scientific field of women’s health. Furthermore, this structure decentralizes and effectively prevents central accountability from managing failures or progress in the field. Consistent with the findings in Enhancing NIH Research on Autoimmune Diseases, this committee finds that without a clear strategic plan for NIH as a whole, it is difficult to track progress or achievement of important milestones (NASEM, 2022).

ORWH has a large and important charge. It oversees essential programs and policies to support the advancement of WHR. It is also responsible for coordination of WHR across NIH—research that spans countless conditions and diseases and is relevant to almost every IC (ORWH, n.d.-j). However, its budget and level of authority are not commensurate with its mission or charge.

NIH SABV POLICY

History of the SABV Policy and Related Requirements

NIH implemented the SABV policy in 2016 to recognize the importance of sex in research and address the persistent exclusion or underrepresentation of females in preclinical and clinical research (Miller et al., 2017; ORWH, 2023). The policy expects that “sex as a biological variable will be factored into research designs, analyses, and reporting in vertebrate animals and human studies” and “strong justification from the scientific literature, preliminary data, or other relevant considerations [if] proposing to study only one sex” (NOT-OD-15–103) (NIH, 2015a).

The SABV policy requires researchers to consider biological sex in their research and describe in their proposals how they will consider it with respect to factors such as study design; the population of interest and study

sample, such as sampling or recruitment procedures and power analyses; and statistical analysis plans. The policy language is broad and allows latitude to incorporate SABV in ways specific to the research questions (Miller and Reckelhoff, 2016; ORWH, n.d.-l). Despite some misconceptions of the policy early on, it does not require researchers to study mechanisms or contributors to sex differences (Clayton, 2018; Dalla et al., 2024; NIH, 2015a; White et al., 2021). What it does require is that investigators provide a justification for not factoring sex into the design (ORWH, n.d.-l). Considerable challenges and limitations remain in implementation of the SABV policy, described next.

Examples of SABV-Related Analyses and Resources for Applicants

Concrete examples of how investigators may incorporate biological sex into their analyses include reporting primary outcomes by sex, including sex as a covariate in models, and reporting sex-disaggregated data in

BOX 3-3

NIH Resources and Training Materials on Sex as a Biological Variable and Sex and Gender Research

SABV Primer:

Developed by ORWH and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and available free to the public, the primer includes four modules that provide an overview of the importance of the SABV policy for scientific rigor, transparency, and discovery across the spectrum of biomedical sciences and how to incorporate SABV in experimental design, analyses, and reporting: SABV and the Health of Women and Men, SABV and Experimental Design, SABV and Analyses, and SABV and Research Reporting (ORWH, n.d.-n,q). In FY 2022, 733 people accessed the primer training, and about three-quarters completed it (ORWH, 2023). There is opportunity to expand this primer by including more contemporary examples of appropriate and inappropriate applications of SABV (e.g., missed opportunities) in practice and in the context of currently used research methods across different fields.

SABV Primer: Train the Trainer:

A six-module course developed by ORWH that guides training of the SABV policy in in-person, virtual, and one-on-one and group training environments and includes SABV best practices (ORWH, n.d.-o). This primer can be expanded to include more specific training modules for researchers who practice in certain fields, such as fundamental biology, population genetics, and interventional studies.

analytic models. The relative appropriateness and potential scientific yield of an approach will vary depending on the research question and context. ORWH has developed resources and training materials on the SABV policy and sex and gender research for the research community, including a Bench-to-Bedside series and core concepts training materials (NIH, n.d.-b; ORWH, n.d.-e). Still, room remains for additional improvement regarding training—particularly tailoring education for scientists who are conducting research in certain fields and using certain methodologies for which SABV considerations may not be intuitive (see Box 3-3).

Effect of SABV

The potential effect of SABV is broad. If it is implemented completely and successfully, effective ongoing training in it would lead to improved and optimal scientific methods and, in turn, scientific discoveries generating new knowledge that could benefit the health of all. Thus, policies such

Sex and Gender Research Modules:

The Bench-to-Bedside: Integrating Sex and Gender to Improve Human Health course includes six modules on sex and gender differences in disease areas, including immunology, cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, neurology, endocrinology, and mental health (ORWH, n.d.-e). Introduction to Sex and Gender: Core Concepts for Health-Related Research includes a video and slide set on sex, gender, and intersectionality as health-related variables (NIH, n.d.-b). The modules could be expanded to tailor them toward researchers practicing in certain fields whose conventional forms of training do not typically include a primary consideration of SABV, such as experimental studies, population genetics, and artificial intelligence (Cirillo et al., 2020; Naqvi et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022).

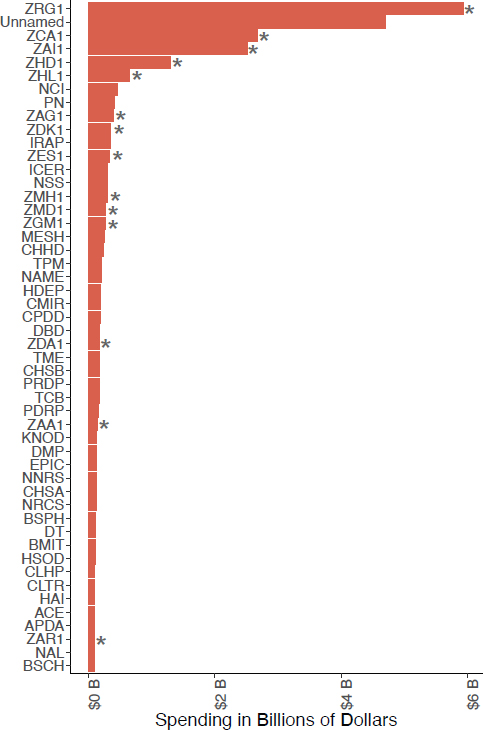

In addition to augmenting education and training resources, an opportunity exists to make evaluating SABV in the peer-review process clearer so that reviewers are able to facilitate more consistent implementation (Arnegard et al., 2020; Woitowich and Woodruff, 2019). The review training slides from the CSR briefly mention SABV in the criterion scores (NIH, 2024h) and the NIH Reviewer Orientation guide does not include information about SABV beyond linking to the decision tree that guides reviewers through steps to evaluate applications for it (NIH, 2018); outcomes include acknowledging the lack of a strong justification for a single-sex study “as a weakness in the critique and discussion and score accordingly” (NIH, n.d.-f). The scoring systems and procedure guidance do not mention SABV (NIH, 2015b). When NIH solicited feedback on the peer-review process, it was unclear to respondents how SABV would be incorporated in the rubric (NIH, 2023h).

as SABV are needed not only to raise awareness of and help fill knowledge gaps in women’s health but also for achieving precision medicine and equity in health care more broadly. Pertaining to health equity, establishing policies requiring investigators to conduct research in a way that produces knowledge that can be applied to both female and male patients is a needed step to ensure that patients are receiving evidenced-base care rather than care that has been investigated adequately only in narrow demographics. Furthermore, methods such as sex disaggregation that fall under the umbrella of SABV can lead to discoveries of sex-specific effects or associations and translate to precision medicine interventions that will ultimately improve outcomes for the entire population (Ji et al., 2020, 2021; Shapiro et al., 2021).

Understanding the successes, limitations, and barriers to implementing the SABV policy requires accepting that SABV and sex differences research are not equivalent. SABV requires all investigators submitting proposals to NIH to include females and males in their study samples unless they have a strong justification otherwise and consider how to best incorporate biological sex into study design and analysis strategies based on the specific research question (Miller and Reckelhoff, 2016; NIH, 2015a). In contrast, sex differences research describes projects in which identifying sex differences in a particular condition or intervention is a primary or at least a secondary objective (Miller and Reckelhoff, 2016). It may require increases in sample sizes and funding based on power analyses designed to detect such differences. Furthermore, though SABV is required for all NIH grant submissions, and incorporating biological sex into study design as more than a control variable can increase the frequency of generating research findings that can benefit the sexes in different ways, it does not mitigate the need for true sex differences research, which fully assesses whether findings apply to the sexes, whether differences exist, and the mechanisms underlying and driving such differences (Galea et al., 2020; Peters and Woodward, 2023). Such research can further advance knowledge of how to care for women as well as men and ultimately lead to better health for all (Galea et al., 2020; Peters and Woodward, 2023).

Limited Appreciation and Uptake of SABV

Several years have passed since NIH enacted the SABV policy (Arnegard et al., 2020; Clayton, 2018). Despite efforts by NIH and other sponsors to implement it across investigator-initiated scientific projects, along with efforts by journals to implement sex and gender in research guidelines in research reporting, uptake and application in practice have been suboptimal (Arnegard et al., 2020; Carmody et al., 2022; Waltz et al., 2021a,b; White et al., 2021). Limited incorporation persists in researchers using preclinical

models (Waltz et al., 2021a,b), and similar issues abound among clinical and population scientists (Willingham, 2022). As a result, the potential generation of new knowledge that could help to address sex disparities and improve women’s health has been stymied.

The problem of limited uptake and application stems from multiple sources, including limited appreciation for the potential scientific yield of applying SABV in research and limited understanding of how to apply it in practice to gain maximal new knowledge. The former has led to many investigators citing a perceived low estimated value-to-cost ratio when considering the resources needed to include animals of both sexes in an experiment or enroll enough women and men to ensure adequate statistical power for sex differences analyses in a clinical study (Waltz et al., 2021a,b) and also perpetuated the perception that SABV should be at most a secondary consideration in research and, in turn, is dispensable if resources are limited. It is coupled to limited understanding of the scientific yield that can arise from when SABV is treated as primary consideration. The scientific knowledge to be gained from treating SABV as a primary versus secondary consideration can be illustrated using examples with a review of relevant fundamental statistical concepts (see Box 3-4).

There are additional considerations regarding SABV as it could be applied in current and future research practice, including the conventional binary definitions of sex and gender (Clayton, 2018; ORWH, n.d.-p; Parker, 2024a). A binary conceptualization of sex excludes other categories, such as intersex, and technically misrepresents how sex frequently manifests as a bimodal distribution of continuous measures with respect to anatomy, physiology, biochemical, and even hormonal measures (Peters and Woodward, 2023; Yang and Rubin, 2024). A wealth of data is now available to clarify how genetic, transcriptomic, and phenotypic traits consistently demonstrate broadly overlapping diversity spanning the sexes. This consistent phenomenon of nature, which manifests, for example, as broad and overlapping bell-shaped curves representing the distributions of height measured across a population of female and male adults, is also seen across many other biological measures, including gene expression (Ahmed et al., 2023; Yang and Rubin, 2024).

Similarly, the SABV policy does not mention gender-related constructs, such as gender identity and gender roles. Advancing progress in women’s health will require that gender be incorporated more systematically into research. This is unlikely without developing and implementing policies requiring researchers to, at a minimum, report the gender identity of their human participants. Accordingly, future SABV training and policy implementation may be developed to include the concepts of sex diversity rather than sex difference, in addition to gender diversity rather than gender difference, as considerations for research on a given topic and in a given context.

BOX 3-4

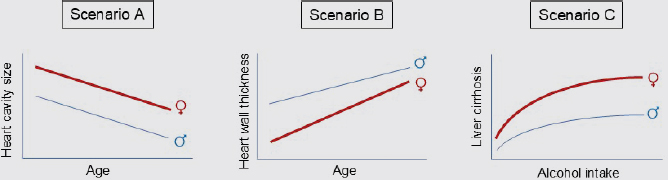

Examples of Primary versus Secondary Consideration of Sex as a Biological Variable in Research

The examples in Figure 3-8 are extrapolated from real data collected and reported in published studies (Cheng et al., 2010; Llamosas-Falcón et al., 2022). Scenario A finds that sex is a confounder when examining the association between age and heart cavity size. The rate of reduction in heart cavity size with advancing age is similar by sex, indicating no significant sex interaction (i.e., similar slopes) (Cheng et al., 2010). In Scenario B, sex has a significant interaction, revealed by different slopes, on the association of age and heart wall thickness, also known as “left ventricular hypertrophy,” an established significant risk factor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (Cheng et al., 2010; Levy, 1988, 1990). Similarly, in Scenario C, sex also has a significant interaction on the association of alcohol intake and liver cirrhosis, a well-known finding that has led to sex-specific recommendations for alcohol intake, yet understanding remains limited of underlying mechanisms (Llamosas-Falcón et al., 2022; USDA, 2020).

In statistical terms, sex is an effect modifier and not just a confounder in Scenarios B and C. When sex is only a confounder, as in Scenario A, a potential treatment implication may be as simple as a dose adjustment. When it is an effect modifier, as in Scenarios B and C, the potential treatment implication may be more complex and even require an alternate therapy altogether (Diao et al., 2024; Kavousi, 2016). In many biomedical research settings, researchers attempting to address SABV often consider Scenario A and stop there, with relatively few considering Scenarios B or C and following up with the requisite sex-stratified analyses needed to understand further implications of the observed sex difference. These examples illustrate why and how the need for comprehensive training and tailored and pragmatic education in how to apply SABV in research persists and how a small amount of additional analytical effort can lead to a large amount of potential scientific gain.

Limited Oversight of SABV Policy

Another major impediment to successful implementation of the SABV policy relates to oversight. There is a lack of systems or procedures to ensure that investigators follow through with their stated plans to incorporate and account for biologic sex into their projects. Grant reviewers are required to consider SABV as a criterion that can affect the overall grant score (NIH, n.d.-f). Unfortunately, it is not clear if attention to SABV during the NIH grant review process is consistent across reviewers and study sections. Based on committee expertise and input from NIH researchers at its public meetings, the merits of investigators’ justifications for not factoring sex into study design are not routinely evaluated. Rewards or penalties in scoring based on implementing SABV in study design are not applied consistently despite NIH guidance to reviewers (NIH, n.d.-f), even where it would contribute to addressing significant knowledge gaps in the evidence base on women’s health and health care.

Several factors may limit adherence to the SABV policy, including the level of reviewer expertise, experience of the NIH program official overseeing the grant, and content area. The lack of a mechanism to ensure that researchers complete and report planned analyses by sex also limits the policy’s effectiveness. This lack of accountability substantially lessens the knowledge that federally funded proposals could generate. Furthermore, there are lessons to learn from policies of other research organizations that not only require grantees to describe sex- and gender-based analyses in their proposals but also hold applicants and reviewers accountable for them (CIHR, 2018; Haverfield and Tannenbaum, 2021; Johnson et al., 2009).

Technical Considerations for Implementing SABV

Certain technical issues merit discussion, given that they represent perceived barriers to incorporating SABV into research studies. For example, investigators have often incorrectly cited marked hormonal variability as a legitimate reason to exclude females from certain studies. It exists in both females and males according to certain time scales and at certain life stages,21 and this variability is important to include and account for across all study types to enhance the potential gain in new knowledge that may be translated to benefit the health of women as well as men (Beery and Zucker, 2011; Bell, 2018; Dalla et al., 2024; Lew et al., 2022). For example, whereas female rats tend to exhibit rhythms occurring over the course of days in physiological trait variations associated with the estrous cycle, this is less robust in mice (Kopp et al., 2006). Accordingly, the aggregate evidence to date from basic models, such as mouse models, has mirrored evidence from human biology studies

___________________

21 Hormonal variation in males occurs in the postnatal period and then at puberty. After that point, testosterone levels in males decline and level off (Bell, 2018).

in demonstrating both sex-specific and sex-similar variations in hormonal, neurohormonal, and other biochemical measures. Such accumulating data have led to a growing awareness and understanding that studying both sexes in a given experiment will increase its translational impact and help avoid inappropriate generalization of findings from males to females or vice versa.

There remains a commonly held perception that adhering to SABV in a proposal will incur greater costs because it would require researchers to increase the sample size of the proposed studies so that they are adequately powered to detect sex differences (Waltz et al., 2021a). However, incorporating SABV into a given study design does not require this in every experimental situation (see Costs and Implementation of SABV in Basic Science section). Applying SABV in many or most scenarios will maximize the opportunity to gain more information on sex-specific or sex-differential findings up front, potentially precluding the need for follow-up studies to investigate sex-divergent effects. For instance, in several examples, lack of prespecified study of sex-specific effects in a trial has required post-hoc, de novo studies of the same intervention (Sohani et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2024). Thus, given the potential for incorporating SABV in studies to maximize their scientific yield and generalizability, doing so is likely to be more rather than less cost efficient over the long term.

Nonetheless, the SABV policy remains a complex issue, given the situations where it may be scientifically justifiable not to incorporate SABV. For example, in certain basic science models, background sex-based genetic differences and hormonal variation have not been shown to affect endpoints of interest. Assessing how to apply SABV in these situations is based on published studies demonstrating that variation in females in a given context is negligible. The SABV policy allows for and encourages describing all scientific justifications for any proposed study designs.

Costs and Implementation of SABV in Basic Science

Sometimes, addressing SABV adds no increased cost. In many cases, sample size does not have to change or requires a small increase to meet the SABV criteria (Dalla et al., 2024). For basic science, implementing SABV would include using females with intact ovaries, ovariectomized females with and without estrogen treatment, and aged females, depending on the study question (Allegra et al., 2023; Dalla et al., 2024; Miller et al., 2011). This does not address changes in postcoital, pregnant, or lactating and weaning animals. Depending upon the parameters being measured, the sample sizes for each cohort can vary from as low as 7 for physiological parameters to at least 10 for standard behavioral assays (Corrigan et al., 2020; Crawley, 1999). With at least six stages in the female life cycle, incorporating SABV can become expensive in these cases.

There is an opportunity to provide additional funding for basic science studies to include sex diversity in model organisms. This may be