A New Vision for Women's Health Research: Transformative Change at the National Institutes of Health (2025)

Chapter: 5 The Biological Basis for Women's Health Through the Lens of Chromosomes and Hormones

5

The Biological Basis for Women’s Health Through the Lens of Chromosomes and Hormones

As Chapter 2 outlines, women’s health is uniquely affected by a number of biological and societal factors. This chapter details the need for sex differences research, including supporting examples; how understanding chromosomal and hormonal contributors to female health helps to advance male health; the complexity and current understanding of female hormonal physiology; and the need to advance our knowledge of how the unique female hormonal physiology contributes to mental and physical health. Understanding female physiology is essential to advance our understanding of how to address female-specific conditions and conditions that affect women differently than men.

NEED FOR SEX DIFFERENCES RESEARCH

The first step to improving women’s health in the United States is to understand sex differences in diseases across the life-span and invest in discovery and implementation science that will improve the lifelong health of both women and men (see later in this chapter for a discussion on the effect of hormones and sex chromosomes across the life course). The following provides a brief background on sex chromosomes and examples from both preclinical and clinical studies demonstrating the importance of studying sex and sex chromosomes to understanding pathophysiology, disease progression, and the effects of treatment in both sexes.

The Role of Sex Chromosomes

Although the majority of this chapter focuses on hormonal changes during the female life course and their effects on health and disease, the role of sex chromosomes also warrants consideration. Sex differences begin with the sex chromosomes, most commonly with females having two X chromosomes and males having only one along with a smaller Y chromosome. To prevent a double dose of X gene expression, one of the X chromosomes in every cell of the female body is randomly inactivated by several cellular mechanisms, one of which is mediated by a long piece of functional RNA (Xist) and the more than 80 proteins associated with it—together called the “Xist ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex” (Dou et al., 2024; Lu et al., 2020).

The initial information gained on the contributions of sex chromosomes came primarily from preclinical models. The discovery of Sry, a gene found on the Y chromosome, as the main testis-determining gene in the early 1990s provided the framework to begin thinking about how the presence or absence of the Y chromosome would set in motion the production of sex steroids in males and females (Sinclair et al., 1990). The absence of Sry and the activity of autosomal genes coordinate development of the female reproductive tract and postnatal steroid production (Rey et al., 2020). Decoding the genetic information of sex chromosomes has lagged far behind that of the autosomal chromosomes, with the human X and Y sequenced fully in 2020 (Miga et al., 2020) and 2023 (Rhie et al., 2023), respectively, nearly 20 years after researchers sequenced the first human genome.

Despite the much smaller size of the Y chromosome, genetic and mechanistic high-impact studies have focused almost exclusively on its role and its contribution to male fitness. While the Y chromosome has shrunk during evolution, its genetic information is critical for ensuring proper testis determination and spermatogenesis and also may account for large phenotypic sex differences in health and disease (Bellott et al., 2014). However, studies focused on sex chromosomes, especially those that include the sex chromosomes in genome-wide association studies (GWAS), are underrepresented in the literature.

Only a small fraction of GWAS have captured any data from the X or Y chromosome (Wise et al., 2013). One recent study concluded that the density of detected single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for the X chromosome was sixfold lower than for frequencies reported for autosomal chromosomes (Gorlov and Amos, 2023), arguing that the lack of SNPs is not a result of a methodological bias (e.g., differences in coverage or call rates) but rather has an underlying biological reason (a lower density of functional SNPs on the X-chromosome vs. autosomes). As a consequence, within the published GWAS catalog, only 25 percent provided results for the X chromosome, and this value dropped even lower, to 3 percent, for the Y chromosome (Sun et al., 2023).

To capture the full potential of the human genome and the role of sex chromosomes in predicting health outcomes for both women and men, it will be essential to include sex chromosomes in GWAS for annotating how genetic variations track with disease. The majority of the research implicating sex chromosomes in disease etiology originates from preclinical models in mice, which is why the lack of X and Y inclusion in most GWAS, whether it be technical or other, created a gap in our ability to investigate and translate those findings to human studies. The lack of information suggests that the GWAS catalog is limited, although increased awareness and newer technology should help overcome this knowledge gap even as each sex chromosome comes with its own unique challenges (Sun et al., 2023).

In addition to the limited efforts in human studies linking sex chromosomes with female-specific or -relevant diseases, their role in disease-relevant phenotypic outcomes in preclinical models has largely been addressed by chance observation or systematically assessing the four core genotypes (FCG) mouse models (Arnold and Chen, 2009). These models take advantage of the phenotypic female-to-male transition after stably expressing Sry in XX mice after reproductive maturity. Conversely, a male-to-female transition is observed when Sry is genetically ablated in XY mice. Comparison with control XX or XY mice enables uncoupling the role of sex chromosomes from hormonal output from the ovary or testes (Arnold, 2020a; De Vries et al., 2002). This system may also inform physiological changes that occur in individuals with differences in or disorders of sex development or the interplay of chromosomes and hormonal treatment in the gender-affirming care of trans individuals. One issue with these models is that for investigators funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the financial burden to successfully breed and maintain FCG mouse cohorts and achieve sufficient statistical power is significant, greatly exceeding a simple comparison between males and females. NIH (and Center for Scientific Review panels) need to recognize and address this large financial obstacle to accelerate question-driven, curiosity-based science.

From preclinical models, researchers are learning that the long, non-coding RNA, Xist, a key player in regulating X-inactivation or silencing, interacts with a myriad of other proteins to drive female-specific autoimmunity (Dou et al., 2024) (see the section on autoimmune diseases later in this chapter for more detail). Less well-documented roles for sex chromosomes involve their developmental programming of neurons (Arnold, 2020b).

Female Sex Chromosome Affects Adverse Effects of an FDA-Approved Medication: Cardiometabolic Disease and Statins

Researchers often evaluate the efficacy of medications to treat common diseases, such as hypercholesterolemia, in large clinical trials that enroll both men and women. The trials use a sample size sufficient to

detect a significant difference between those treated with the active medication or the placebo. However, they often do not include enough people to also look for sex differences in the effects (Galea et al., 2020). Medications may behave differently in women and men, resulting in variations in efficacy or the rate and type of adverse effects; analyzing these data together obscures any heterogeneity in response (Soldin and Mattison, 2009; Zucker and Prendergast, 2020). This oversight has implications for clinical practice, given that medications that have been shown to be effective for men and women together may be less so or cause more adverse effects for women.

A clear example is sex differences in cardiometabolic diseases and their treatment. Serum metabolite concentrations in healthy men and women differ significantly (Mittelstrass et al., 2011; Reue, 2024). In addition, the risk of several metabolic parameters and diseases differs in prevalence, including adipose distribution, plasma lipid profiles, insulin resistance, hypertension, fatty liver, myocardial infarct risk, and ischemic stroke risk (Chella Krishnan et al., 2018). These differences most likely result from sex chromosomes active in every cell throughout the lifetime. Sex chromosomes, especially XX, are known to influence several cardiometabolic traits, including body fat, fatty liver, insulin resistance, and atherosclerosis, and X escape genes appear to modulate fat mass and energy expenditure (Link et al., 2013).

Individuals with two X chromosomes experience a nearly 50 percent increased risk of adverse events with statin therapy compared to those with one X chromosome, including myopathy and new-onset Type 2 diabetes (Bytyçi et al., 2022; Goodarzi et al., 2013; Nguyen et al., 2018; Reue, 2024). To determine the source of this increased risk, investigators performed a preclinical study in mice; they added statin to the chow of male and female mice and found that fasting blood glucose increased in the female but not male mice, and female mice developed significant glucose intolerance after 4 weeks of statin treatment (Zhang et al., 2024). The researchers also found a reduction in grip strength and number of mitochondria in muscle only in the female mice treated with statin on the diet, which they could prevent by reducing the dosage of the X chromosome or Kdm5c gene (a sex chromosome gene), which is normally expressed at higher levels in females (Zhang et al., 2024). Given that statins reduced omega-3 free fatty acids in the female mice, the investigators tested fish oil as a therapy to prevent the side effects in female mice and found that glucose intolerance decreased and grip strength increased. The research team conducted a clinical study where they confirmed that statin treatment reduced omega-3 fatty acid levels and mitochondrial respiration more in women than men (Zhang et al., 2024). While this research was primarily in mice, the findings could have

sizable implications for the approximately 92 million U.S. individuals, particularly the women, who are prescribed statins to treat high cholesterol and reduce the risk of primary and secondary cardiac events (Matyori et al., 2023).

Though more than 35 years have elapsed since the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first approved statins, research has not examined the cardiometabolic differences influenced by the XX chromosome dosage and sex differences in fatty acid metabolism that induce more side effects in women than men, leaving gaps in implementing preventive strategies that could have reduced the rate of adverse events and side effects for many women prescribed statins (Endo, 2010). Given the simple solution of adding omega-3 fatty acids to prevent blood sugar and muscle-related adverse effects, this finding should motivate further studies on women and men separately to understand the biology of the disease state and how much the adverse effects of medications are influenced by sex. See Box 5-1 for additional examples of research needs in this area that affect treatment of women.

BOX 5-1

Effect of Sex on Cardiometabolic Health and Disease—Research Needs

- Define values for cardiometabolic parameters in health and disease states in men and women separately.

- Determine changes in cardiometabolic parameters in women throughout the life-span, including effects of puberty, pregnancy, and the menopause transition.

- Assess the effects of the intersection of sex with genetic background, environment (including the mediating and moderating effects of weight bias), and gender on cardiometabolic traits.

- Identify molecular differences between sexes in metabolic tissues at the level of chromatin organization, DNA methylation, and gene expression using state-of-the-art techniques, such as single cellomics, multi-omics, and spatial-omics, in experimental models and human tissues.

- Characterize drug action and adverse effects in both sexes and disaggregate data by sex. Use experimental models to identify mechanisms, particularly for studies of widely used and newer drugs aimed at reducing cardiometabolic disease risk, including statins, Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors.

Female Sex Chromosomes Affect the Pathogenesis of a Common Disease Class: Autoimmune Diseases

Autoimmune diseases, which result from the immune system mistakenly attacking the body’s own healthy cells, affect up to 50 million U.S. individuals, and at least 80 percent of them are female (Angum et al., 2020; Ngo et al., 2014; NIEHS, 2024). Autoimmune diseases include lupus, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and over 70 other disorders (NASEM, 2022, 2024). It is thought that a combination of genetic risk factors and exposures to one or more stressors on the body give rise to the majority of autoimmune diseases (NASEM, 2022, 2024), but researchers have not yet identified differences in genes and hormones that may explain this sex difference in incidence and prevalence (NIH, 2024). In recent years, an exciting breakthrough has occurred in understanding a pathophysiology of autoimmune diseases in women that appears to be mediated by female sex chromosomes (Dou et al., 2024; Jiwrajka and Anguera, 2022; Pyfrom et al., 2021; Syrett et al., 2019, 2020; Wang et al., 2016).

Research examined the relationship between the Xist RNP complex and autoimmunity (Dou et al., 2024). Considering that this complex is only expressed in females, the investigators sought to determine if Xist expression in males alters the immune response and produces features of autoimmune disease typically observed in females. The researchers used two strains of mice—one resistant and the other susceptible to autoimmune challenges—and genetically engineered them to express Xist. Only male mice from the autoimmune-susceptible genetic background with the transplanted Xist gene developed severe autoimmune disease after exposure to a known chemical inducer of lupus. The extent of disease pathology was similar to that observed in female mice from the same background after trigger exposure. However, susceptible male mice that did not make Xist also did not develop features of autoimmunity in response to the trigger. The investigators also observed that autoantibodies—the immune system proteins that attack normal cells in autoimmune diseases—recognized some of the proteins associated with the Xist RNP complex in this mouse model (Dou et al., 2024). Together, these findings suggest that the Xist RNP complex may be a key mediator of mechanisms that predispose females to an increased vulnerability to autoimmune disease.

The researchers next looked at autoantibodies to XIST—the human version of Xist—and related proteins in human blood (Dou et al., 2024). They found autoantibodies to dozens of proteins associated with the XIST RNP complex in people with autoimmune diseases—including many that they found in mice that developed autoimmune disease—but not in those without the conditions. Previous studies had identified some of the

autoantibodies as being associated with autoimmune disease, but others were novel (Arbuckle et al., 2003; Rosen and Casciola-Rosen, 2016). While the XIST RNP complex alone does not cause an autoimmune response, these findings suggest that it may help trigger it in people who are vulnerable. More work is needed to understand exactly which proteins in the complex may be responsible, which could lead to more sensitive tests that could catch autoimmune diseases earlier and lead to the development of new prevention approaches.

Although it was known that every cell in the female body produces XIST, researchers have continued to rely on male animals and cell lines for their studies (Kim et al., 2021), and when they have included both male and female animals and cell lines, they are usually not analyzed separately. Thus, the standard practice in cell physiology research made it highly unlikely these anti-XIST-complex antibodies would ever have been discovered. This recent breakthrough underscores the role of basic science in helping to explain the disproportionately high number of women who suffer from autoimmune disorders, which are only one of many conditions that disproportionally and differentially affect women, so discovering the role of X-linked proteins here may lead to discoveries in other conditions as well.

Importance of Sex-Stratified Analyses in Clinical Research

Exercise physiology offers an example of the utility and benefits of sex-stratified analyses in research. Women have statistically lagged men in engaging in meaningful exercise. In addition, it was assumed that men and women needed the same amount of exercise to derive cardiovascular benefits. However, when a study analyzed National Health Interview Survey data from 412,413 U.S. adults (55 percent female) for gender-specific outcomes related to leisure-time physical activity, researchers found that men achieved maximal survival benefit from moderate to vigorous aerobic activity (e.g., cycling) for about 5 hours per week (Ji et al., 2024). In contrast, women achieved similar benefits from approximately 2.5 hours of exercise per week. In addition, engaging in regular physical activity resulted in 24 percent lower mortality risk in women compared to only 15 percent in men (Ji et al., 2024). Therefore, by studying women and men together but analyzing their data separately, the investigators found that women can get more out of each minute of moderate to vigorous activity than men do. This study, if replicated, could lead to sex-specific exercise recommendations to improve the health of both men and women.

Studying Women Leads to Findings That Improve All People’s Health

Studying women independently can also inform men’s health research. This section highlights examples in two disease areas—bone health and cancer treatment.

Bone Health

As described in Chapter 2, osteoporosis is a disease in which there is a loss of both bone mass and structure such that the bone can fracture with very little force. Both men and women achieve peak bone mass in their early twenties, but women lose bone earlier and more rapidly than men because of hormone changes in the menopause transition (Karlamangla et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2016).

A class of medications that decrease bone resorption, bisphosphonates, were approved more than 2 decades ago as the first nonhormonal treatment for osteoporosis in women (Russell, 2011). Subsequent research found that after the rapid loss of bone during the menopause transition, the slower loss of trabecular bone resulted from reduced activity of osteoblasts, the cells responsible for new bone formation (Ji and Yu, 2015; Thapa et al., 2022). This led to the development and approval of two medications—a truncated form of human parathyroid hormone (hPTH (1–34)) and romosozumab—that stimulate osteoblasts to form new bone (Bandeira and Lewiecki, 2022). In addition, developing medications that could both prevent and treat osteoporosis in women led to creating and adopting guidelines for when to evaluate them. Today, women without significant risk factors are recommended to obtain a bone mineral density scan by age 65 years and be treated with bone-active medications if their bone mass is found to be low, putting them at increased risk of fractures (Kling et al., 2014; McPhee et al., 2022). The knowledge gained about bone loss in women and the medications to prevent and treat osteoporosis have also been applied to men. Based on the observation that men did not have the rapid loss seen in women, the guidelines recommend waiting until age 70 to screen men for osteoporosis, if no risk factors are present (Adler, 2000; Bello et al., 2024). In addition, all the medications approved for treating osteoporosis in women are also effective for maintaining bone mass in men (Tu et al., 2018). Therefore, the extensive knowledge base built on understanding and treating osteoporosis in women led to additional research in men that identified new surveillance and treatment recommendations, with implications for health coverage and costs.

Cancer Treatment and Care

Another example of how studying a condition in women can lead to breakthroughs for men’s health comes from the contributions of breast and ovarian cancer research to prostate cancer treatment, such as

groundbreaking research regarding aromatase inhibitors, which deplete estrogen levels, and poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors. Adverse events related to aromatase inhibitors, used as adjunct therapies for breast cancer in women, informed researchers and laid a pathway to approach androgen depletion in men treated for prostate cancer (Clinical Education at JAX, 2024; Michmerhuizen et al., 2020; Ulm et al., 2019).

Breast cancer treatment in women has evolved such that adjunctive therapies, especially aromatase inhibitors, have become standard of care. However, early in their clinical adoption, it became clear the treatments that reduce serum estrogen levels could cause rapid reduction in bone mass and increase the risk of incident fractures. This led to recommendations for bone mineral density screening of women with breast cancer before initiating these treatments; if the bone mass was low and osteoporosis fracture risk high, nonhormonal treatments to maintain bone density and prevent fractures were instituted with bisphosphonates or denosumab. These recommendations for assessment and preservation of bone mass were drafted and published in 2003 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. This is another example of how studying women’s health and disease advanced men’s health, especially in the use of bone-active agents to prevent bone loss when hormone-depleting agents are instituted to prevent cancer recurrence (Brown et al., 2020; Diana et al., 2021; Johnson et al., 2021; Pineda-Moncusí et al., 2020; Shapiro, 2020; Suarez-Almazor et al., 2022). However, it took another 17 years to translate recommendations regarding screening and treatment to men when androgen-depleting treatments of prostate cancer were adopted (Bruning et al., 1990; Chen et al., 2005; Ramin et al., 2018).

PARP inhibitors, which block DNA repair in tumor cells by inhibiting the PARP enzyme, are FDA-approved treatments for women with breast and ovarian hereditary cancer syndromes with BRCA mutations (Menezes et al., 2022). Cancers characterized by BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutations have deficient DNA-damage repair. The overlying hypothesis that BRCA1/2 mutated cancers and other cancers with defective DNA repair are more sensitive to PARP inhibitors compared to normal cells has been demonstrated in preclinical models and clinical trials. In 2014, FDA approved olaparib, the first PARP inhibitor, for patients with advanced ovarian cancers harboring BRCA mutations (Drugs.com, 2023; FDA, 2017). A randomized double-blind Phase III study of maintenance olaparib compared to placebo in patients with a BRCA mutation found a 70 percent reduction in risk of disease progression or death and higher progressive-free survival in those receiving olaparib compared to placebo (Moore et al., 2018). All subsequent studies of other PARP inhibitors demonstrated significant improvements in progression-free survival

compared to placebo, leading to additional FDA approvals for olaparib in 2018, niraparib in 2020, and olaparib in combination with bevacizumab, which blocks tumor-triggered blood vessel formation, in select patients in 2020 (FDA, 2018, 2020a, 2020b). This exemplifies the need for sex-difference and sex-specific research to apply findings accurately to the care of women.

Two PARP inhibitors are also approved to treat breast cancer with BRCA mutations. These discoveries have also benefited men with BRCA-mutated prostate cancer. FDA then approved PARP inhibitors, either alone or in combination with other agents, for specific indications, such as prostate cancers that are castration resistant or have BRCA mutations. Overall, the successful evaluation of PARP inhibitors for metastatic cancer is the culmination of over 60 years of work since the first PARP enzyme was identified (Drew, 2015). The research and clinical opportunities, which were first recognized in women with breast and ovarian hereditary cancer syndromes, ultimately led to clinical trials in men with BRCA-mutated prostate cancer, improving cancer outcomes for both men and women (Drew, 2015).

Summary of the Need for Sex Differences Research

This section provided examples highlighting the importance of studying sex and sex chromosomes at the levels of cells and organisms in preclinical, observational, and clinical trials research. Sex chromosomes influence the cardiometabolic traits that underly some of the most chronic, burdensome, and costly health conditions, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), Type 2 diabetes, and osteoporosis. Moreover, sex and sex chromosomes influence the effects of interventions—medication and behavioral—on health outcomes. Research on the effects of sex chromosomes on health and disease, however, is only in its infancy. The dominance of male cell lines and male animals in basic physiologic research persists, and therefore, many gaps persist in knowledge related to conditions that differentially affect women (Kim et al., 2021).

Because this research is relatively new, researchers are not yet able to accurately identify all the research gaps or quantify their effect on the health of women and men. Sex and sex chromosomes have been viewed as playing a role only in fetal development. However, evidence is growing of the sizable impact that sex chromosomes have on health throughout the lifespan, dictating the development of the fetus, child, adolescent, and adult, and interacting both independently of and synergistically with sex steroids, which vary over the life course. This research urgently warrants attention to improve health outcomes for all people. The next section describes sex

steroid variation over the life course in women, provides examples of how such changes affect women’s health, and identifies gaps in knowledge on sex steroids and health.

THE FEMALE HORMONAL LIFE COURSE—IMPLICATIONS FOR UNDERSTANDING MENTAL AND PHYSICAL HEALTH MANIFESTATIONS

Understanding female physiology is necessary to accelerate progress and fully elucidate underlying mechanisms of conditions that affect women’s health. Female physiology is more dynamic because of hormonal fluctuations throughout the life cycle. Understanding this complexity of normal physiology in females can help inform how natural changes and fluctuations in hormone signaling contribute to physical and mental health in women. It is important to summarize the current understanding of normal female hormonal physiology. In this section, the committee provides a comprehensive overview of basic knowledge of female hormonal physiology and, where applicable, questions that have yet to be answered or investigated. See Box 5-2 for key findings from this section.

BOX 5-2

Key Findings

- Much of women’s health research has focused primarily on the associations of estrogens and progestins with various female disease states; however, other known, less-well-characterized hormones are sure to play a role in basic female physiology and health over the life-span. Without well-funded, sustained efforts that focus on women and female model systems, the hormonal and chromosomal contributions to disease pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets in improving human health represent a missed opportunity.

- While much is known about female hormonal physiology with respect to the reproductive cycle, researchers still do not understand why hormonal fluctuations across the female life course are tightly coupled to diseases of the brain and peripheral tissues.

- Data on sex hormones, including sex hormone–binding globulin, a sex steroid transporter, androgens, and follicle-stimulating hormone, and cardiometabolic disease suggest important associations with cardiometabolic disease, but more data and analysis are needed to understand the underlying mechanisms and potential therapeutic implications.

CURRENT UNDERSTANDING OF FEMALE HORMONAL PHYSIOLOGY

Puberty

Two discrete physiological processes—the growth and maturation of the gonads, or gonadarche, and increased production of adrenal hormones, or adrenarche (Bangalore Krishna and Witchel, 2024)—characterize puberty. The pubertal transition and gonadarche begins with activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and pulsatile secretion of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, which stimulates the pituitary to release follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) (Wolf and Long, 2016). In girls, FSH promotes growth of ovarian follicles, skeletal maturation, and growth plate fusion, leading to cessation of growth (Wolf and Long, 2016). FSH and LH together stimulate the ovarian follicles to synthesize estradiol, which promotes cornification of the vaginal mucosa and uterine growth, in addition to breast development. This process culminates in ovulation and menses (Bangalore Krishna and Witchel, 2024) (see next section).

Even before the physical signs of puberty are visible, pulsatile secretion of GnRH and resultant pulsatile release of FSH and LH occurs, primarily at night initially. As puberty progresses, this pattern transitions to the adult pulsatile pattern throughout the day (Wolf and Long, 2016). It is unclear what prompts initiation of pulsatile GnRH release and what factors keep the “pulse generator” quiescent throughout childhood (Wolf and Long, 2016). Proposed signals stimulating GnRH neurons include kisspeptins, neurokinin B, leptin, and gonadal steroids, but additional research is needed in this area (Bangalore Krishna and Witchel, 2024; Wolf and Long, 2016).

Adrenarche is defined by increased release of adrenal hormones: dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) sulfate, androstenedione, testosterone, and 11-oxyandrogens. These hormones lead to development of pubic and axillary hair, increased apocrine body odor, and acne (changes known as “pubarche”) (Bangalore Krishna and Witchel, 2024). While knowledge about adrenal physiology continues to grow, the trigger for adrenarche remains unknown (Bangalore Krishna and Witchel, 2024).

For girls, in general, breast development occurs before pubic hair development, although both processes become more synchronized as puberty proceeds (Bangalore Krishna and Witchel, 2024). The growth spurt occurs simultaneously with breast budding, peaking in mid-puberty. Menarche generally occurs 2–3 years following onset of breast development with only a small amount of linear growth thereafter (Bangalore Krishna and Witchel, 2024). Longitudinal studies suggest that puberty is starting at younger ages, which may be the result of rising rates of obesity, environmental factors, stress and perinatal growth, and epigenetic factors (Bangalore Krishna and

Witchel, 2024). This warrants ongoing research to understand the implications of these exposures on not only puberty but also health in adulthood.

Menstruation

The unique reproductive demands placed on females result in dynamic hormonal fluctuations marked by significant and cyclical changes in multiple hormonal systems. The HPG axis largely regulates these hormonal fluctuations in female physiology. It is these three tissues that primarily coordinate hormonal changes during the female reproductive life course, which is marked by the onset of puberty and menarche (the first menstrual period). Throughout the reproductive years, this female-specific physiology is initiated in the brain, mainly through the hypothalamic release of GnRH. Within the pituitary, FSH and LH act on ovaries to elicit monthly cyclical secretions of the sex steroids estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4) from the ovaries. Hormonal secretions controlled by the HPG axis coordinate ovulation and prepare the uterine lining for implantation and support of a fertilized ovum (Bulun, 2016).

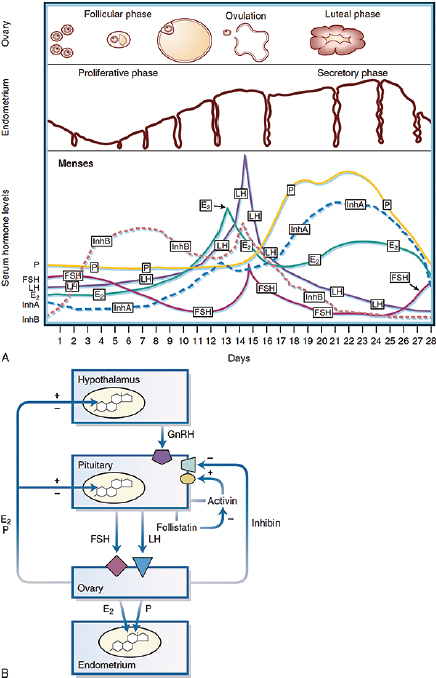

Other endocrine systems, including the adrenal and thyroid axes, also participate in ovulation. Aside from their role in the central control of GnRH pulsatility, neurotransmitters and neuropeptides, including dopamine, nor-epinephrine, serotonin, and opioids have profound effects on the HPG axis (Bulun, 2016). Similarly, ovarian sex steroids and polypeptide hormones, inhibin, activin, and follistatin (Bulun, 2016), influence gonadotropin production (see Figure 5-1). For reproductive success, a preovulatory surge of LH is required during the mid-cycle to trigger ovulation; the empty shell transforms into the corpus luteum, which secretes steroids for sustaining an implanted fertilized gamete. Specifically, E2 stimulates the proliferation of the endometrium, whereas P4 promotes endometrial differentiation (Bulun, 2016). Without fertilization, the corpus luteum involutes, E2 and P4 subside, and uterus sheds its lining, resulting in a monthly menstrual cycle (Bulun, 2016).

Pregnancy

Pregnancy results when an ovum is fertilized and implants successfully into the uterine lining. Throughout gestation, multiple hormones ensure the uterine environment will support fetal growth and development and prepare the pregnant person for delivery and nursing. An important aspect of pregnancy in humans is the luteal-placental shift that involves reliance on placental human chorionic gonadotropin instead of the corpus luteum. However, because trophoblasts—the cells that provide nutrients to the embryo and develop into a large part of the placenta—lack the enzymes necessary to convert progesterone to estrogen (17α-hydroxylase

NOTES: A, Changes in the ovarian follicle, endometrial thickness, and serum hormone levels during a 28-day menstrual cycle. Menses occur during the first few days of the cycle. B, Endocrine interactions in the female reproductive axis, including some of the well-characterized endocrine interactions among the hypothalamus, pituitary, ovary, and endometrium for regulation of the menstrual cycle. E2 = estradiol; FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRH = gonadotropin-releasing hormone; InhA = Inhibin A; InhB = Inhibin B; LH = luteinizing hormone.

SOURCE: Bulun, 2016; Used with permission of Elsevier, permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

and 17,20-lyase), estrogens are synthesized through a combination of fetal adrenal and liver precursors that are metabolized in placental trophoblasts to generate estriol (E3), the major estrogen in the maternal circulation (Tal and Taylor, 2021). Other estrogens synthesized by the maternal-fetal-placental unit include E2, estrone (E1), and estetrol (E4). During pregnancy, estrogens have multiple roles, including enhancing receptor-mediated uptake of low-density lipoprotein-bound cholesterol for steroid production, increasing uteroplacental blood flow, increasing endometrial prostaglandin

synthesis, and preparing the breasts for lactation (Tal and Taylor, 2021). Before birth, estrogens help to stimulate pituitary prolactin synthesis and secretion in anticipation of future lactation or breastfeeding (Al-Chalabi et al., 2023). Aside from these hormonal changes, pregnancy induces a suite of physiological responses involving metabolic responses with respect to how fuel is absorbed, stored, or allocated. Other major changes include the increased demands on the cardiovascular system and hemodynamic properties, which are discussed later in this chapter.

Perimenopause and Menopause

Menopause marks the end of cyclical menstrual periods resulting from the loss of ovarian function and the end of the reproductive phase of the female life course; the final menstrual period can only be determined retrospectively after 1 year without menses (El Khoudary et al., 2019; Harlow et al., 2012). The menopause transition may occur naturally, as ovaries stop producing eggs and ovarian synthesis and secretion of E2 gradually declines and then stabilizes postmenopause (El Khoudary et al., 2019; Harlow et al., 2012). Early menopause can occur by surgical removal of the ovaries, resulting in an abrupt decline in E2, or by anti-hormone therapies commonly used in breast cancer survivors that eliminate E2 biosynthesis (Bulun, 2016; Okeke et al., 2013; Rosenberg and Partridge, 2013). Perimenopause occurs in the years preceding menopause, characterized by anovulatory cycles and irregular menses, through one year after the final menstrual period (Bulun, 2016; Santoro, 2016).1 Hormonal changes in perimenopause include elevation of FSH, decreased inhibin levels, normal LH, and slightly elevated and variable estradiol (Bulun, 2016; El Khoudary et al., 2019; Harlow et al., 2012). As the ovary ages and follicular reserves begin to decline after age 30, inhibin and anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels begin to drop; these drop even further after age 40, allowing FSH to rise (Bulun, 2016; de Kat et al., 2016). One of the best biomarkers for the ovarian reserve is AMH, which has become a useful tool in assisted reproductive technology for humans (Bedenk et al., 2020).

Following menopause, a host of disorders and diseases increase, including vasomotor instability, urogenital atrophy, adiposity and Type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, musculoskeletal symptoms, and CVD (Bulun, 2016; Jiang et al., 2019; OASH, 2023; Opoku et al., 2023). Post-menopause, androgens increase from both the ovaries and the adrenal glands, which produce a suite of androgens, including DHEA and DHEA-S. The lower amounts of postmenopausal estrogen are derived from the conversion of androstenedione to estrone in adrenal glands and further modification of estrone to estradiol via aromatase in adipose tissue. These hormonal changes cause

___________________

1 This sentence was changed after release of the report to clarify the definition of perimenopause.

a precipitous drop in estradiol that effectively increases the androgen-to-estrogen ratio in postmenopausal women, potentially contributing to the many changes reported in the postmenopausal state (Bulun, 2016).

Menopause hormone therapy, or hormone replacement therapy, is used to ease symptoms of the menopause transition and can improve quality of life (Santoro, 2016). In 2002, the Women’s Health Initiative, evaluating the effect of hormone replacement therapy on CVD among other trial aims and outcomes, found increased risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and breast cancer among participants taking estrogen plus progestin (though estrogen-only therapy reduced the risk of those same outcomes) and recommended that postmenopausal women not be treated with hormone replacement therapy to prevent CVD or other chronic conditions (Chlebowski et al., 2015; Madsen et al., 2023; Manson et al., 2013, 2024; Manson and Kaunitz, 2016; Rossouw et al., 2002). Use of hormone therapy among peri- and postmenopausal women decreased precipitously after publication of the initial findings (Crawford et al., 2018; Madsen et al., 2023; Manson et al., 2024; Sprague et al., 2012). Since that time, however, additional analyses of Women’s Health Initiative data and other studies have led women’s health experts to further elucidate the role of hormone replacement therapy for peri- and postmenopausal women. Specifically, subgroup data from the Women’s Health Initiative, along with data from other trials and cohorts, support the use of short-term hormone therapy for vasomotor symptoms in subgroups of women for whom benefits outweigh the risks (i.e., women younger than 60 and in early perimenopause without other significant comorbidities) (Madsen et al., 2023; Manson et al., 2024; Manson and Kaunitz, 2016).

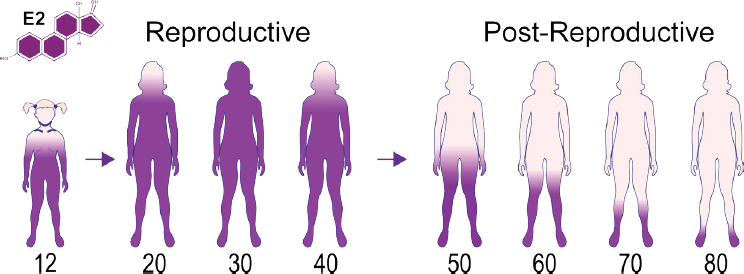

Understanding the effect of female hormone physiology on physical and mental health across the life course is important in providing insight into how fluctuations in the normal hormonal profile, particularly the changes in estrogen noted in Figure 5-2, may increase the risk for mental and physical health disorders throughout life.

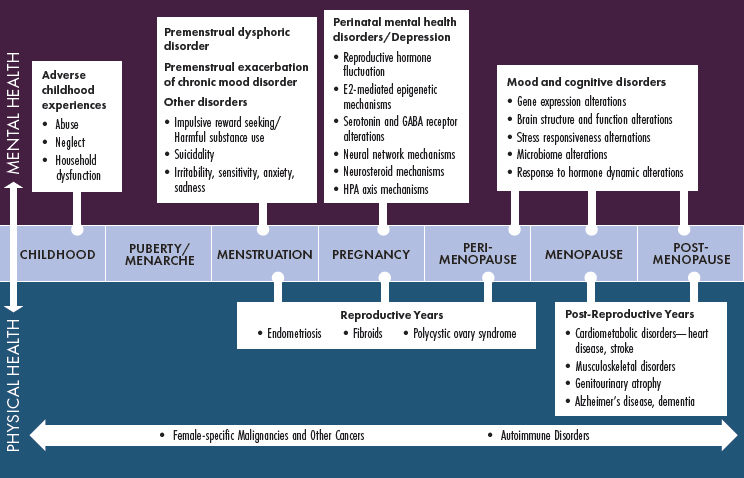

The next sections summarize the current understanding of the association of changes and perturbations in female hormonal physiology with mental and physical health conditions across the life-span and gaps in current knowledge (see Figure 5-3).

HORMONAL ASSOCIATIONS WITH MENTAL HEALTH DISORDERS ACROSS THE LIFE COURSE

Given the chemical nature of estrogen as a lipophilic steroid, its uptake and subsequent regulation of genetic pathways can occur in any cell within central and peripheral tissues that also express one of the three cognate receptors (Chen et al., 2022). Thus, in addition to reproductive organs, estrogen signaling can occur in nearly all organs, including the brain

SOURCE: Adapted from ID 142070810, Estrogen Testosterone ©Designua, Dreamstime.com.

(Chen et al., 2022). However, a molecular understanding of the key cellular E2 targets in tissues other than the breast or uterus has been understudied over the past 2 decades and remains elusive. This is especially true of the brain, where both neuronal and nonneuronal cell types, such as microglia, astrocytes, and ependymal cells, are replete with the nuclear estrogen receptor-alpha (Elzer et al., 2010; Osterlund et al., 2000). Although it has been well documented in rodent models that ovarian steroids modulate

NOTE: E2 = estradiol; GABA = gamma-aminobutyric acid; HPA = hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

brain activity and behaviors that maximize reproductive success in females, including feeding, mating, defensive, and maternal behaviors, researchers still do not understand why female-related affective disorders are linked to hormonal fluctuations across the life course (Etgen et al., 1999; McCarthy and Pfaus, 1996).

Despite the centrality of ovarian steroids, research also suggests that normative changes in sex steroids during sensitive windows, including puberty, the menstrual cycle, pregnancy and postpartum, and the menopause transition, trigger psychiatric symptoms in some women (Kundakovic and Rocks, 2022; Schweizer-Schubert et al., 2020). Decades of research focused on understanding the role of ovarian steroids in mood disorders in women have led to limited breakthroughs in the past decade. The bench-to-bedside application of extant knowledge of sex steroids and preclinical models of perinatal depression (PND) has helped researchers to identify novel treatments and resulted in two new FDA-approved medications for postpartum depression in the past 5 years (FDA, 2019, 2023). Sleep also plays an important role in mental health, with sex differences in sleep patterns and sleep disorders (e.g., women are more likely than men to report insomnia, and a bidirectional relationship exists between sleep disturbance and mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety) (Perger et al., 2024; Rumble et al., 2023). Changing hormone levels throughout female life stages may affect sleep, and sleep is an important factor in the conditions described in the following section. For example, premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is associated with poor-quality sleep, insomnia, and fatigue in the premenstrual phase, affecting mood and emotional processing (Lin et al., 2021; Meers and Nowakowski, 2020). Poor-quality sleep during pregnancy is also associated with PND, and increased maternal and gestational ages worsen sleep quality (Fu et al., 2023; Poeira and Zangão, 2022). Finally, sleep disturbances are common during perimenopause, and vasomotor symptoms coupled with chronic sleep disturbance increase the risk of depression during the menopause transition (Brown et al., 2024; Joffe et al., 2010).

Researchers have begun mapping the effects of ovarian steroids on the brain during puberty, the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and the menopause transition. This work, however, has taken substantial time—80 years from identifying allopregnanolone to the FDA approval of brexanolone as an efficacious treatment for postpartum depression—and the majority of studies of hormone effects on the brain have been underpowered (Pinna, 2020; Reddy et al., 2023). The lack of statistical significance, rather than being interpreted as needing larger, adequately powered studies, has sometimes led researchers to assume an absence of an effect of hormones on the brain (Bachmann et al., 2024; Leeners et al., 2017; Petersen et al., 2021; Smart et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2019).

Although depression affects 57 percent of adolescent girls and 24 percent of women each year, human imaging studies examining sex differences, women’s health, or female endocrinology remain relatively scant (CDC, 2023; Lee et al., 2023; Taylor et al., 2021). A recent analysis showed that only 2 percent of human brain imaging studies published in the top five neuroscience journals mentioned women’s health, and of those, 83 percent included the women’s health variable to justify excluding women, characterize the sample without further analysis, such as reporting the number taking oral contraceptives, or control for sex steroids in statistical models (Taylor et al., 2021). While private philanthropy has begun to support such research (Jacobs, 2023; Stevens, 2019), publicly funded efforts at a national level have yet to be prioritized or implemented.

Other than laying out the basic framework of hormonal changes during puberty, the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and the menopause transition, there is relatively little understanding of how the female endocrine system affects nonreproductive target organs in nondisease and disease states, such as the heart. This is particularly apparent in mental health, where preclinical studies have identified the neuromodulatory effects of ovarian steroids, but the precise neuronal circuits affected or molecular targets in the brain have yet to be elucidated. Other major initiatives on the brain, such as Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies, do not adequately address this lack of information because they have not prioritized research on the female brain or sex differences (NIH, n.d.; BRAIN Initiative Alliance, n.d.). For the human brain, the effects of ovarian steroids are only beginning to receive attention, as evidenced by smaller university- or foundation-led research initiatives that specifically prioritize women’s brain health (BWH, n.d.; Weill Cornell Medicine Neurology, n.d.). In the following sections, the committee describes the clinical state of knowledge on how hormonal fluctuations during the female life course correlate with and might contribute to mental health disorders and the remaining gaps in knowledge.

Pubertal Depression

The increased risk of depression in women, compared with men, begins at mid-puberty and persists through the female reproductive lifespan. Before puberty, depression rates are similar in boys and girls. After menarche, girls are twice as likely to experience depression and suicidal thoughts and behaviors, leading some to hypothesize a role for ovarian steroids in triggering depression in girls. The first year following menarche is characterized by irregular and anovulatory menstrual cycles, which increase ovarian steroid instability and may, in turn, trigger depression. Recent research suggests the confluence of increased ovarian steroid fluctuations and interpersonal stress

during puberty triggers depression in girls. One recent study demonstrated that 57 percent of girls reported depressed mood during periods of ovarian steroid change (Andersen et al., 2022). A subsequent study showed that recent stressful life events interacted with estrogen to predict depressed mood in pubertal girls (Andersen et al., 2024).

Despite these advances, research has been correlational, and few preclinical models identifying neuroendocrine mechanisms of pubertal depression exist. The neurobiological mechanisms that explain how stress and ovarian steroid fluctuation interact to trigger depression remain unknown, and research has only just begun to focus on how the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, HPG axis, and central nervous system interact to determine affective states in humans (Ludwig et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2021). Research in this area, particularly in puberty, is sorely needed given the alarming increases in child and adolescent stress during the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of self-reported loneliness and suicidality, and prevalence of depression in girls (Chavira et al., 2022; Madigan et al., 2023).

PMDD and Other Menstrual-Related Mood Disorders

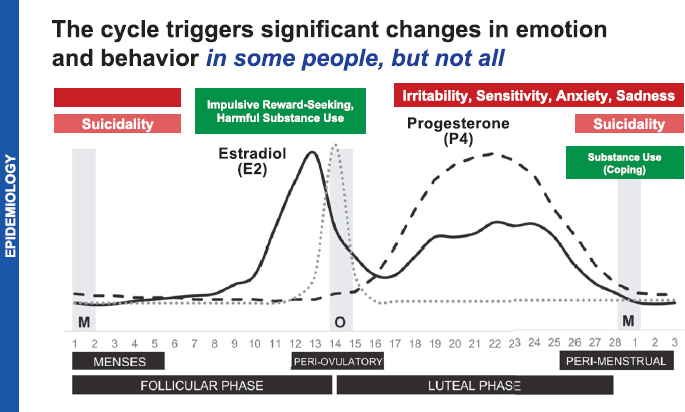

Hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle trigger emotional and behavioral changes in some people (see Figure 5-4). Symptoms include impulsive reward seeking and harmful substance use during the follicular phase of the cycle and irritability, sensitivity, anxiety, and sadness during the luteal phase. The latter set of symptoms generally remit after the onset of

SOURCE: Eisenlohr-Moul, 2024.

menses. Suicidality and substance use as a coping mechanism occurs in some during the perimenstrual and menstrual phase (Eisenlohr-Moul, 2024).

PMDD is the sole diagnostic entity for mood symptoms that occur in predictable patterns during the menstrual cycle. It describes a pattern of at least five symptoms, at least one emotional, in the week before menses that resolve in the week after. Emotional symptoms include affective lability, irritability, anger, interpersonal conflicts, depressed mood, and anxiety. Individuals with PMDD may also experience an inability to experience joy or pleasure, poor concentration, lethargy, change in appetite, hypersomnia or insomnia, feeling overwhelmed or out of control, or physical symptoms, such as bloating and pain (Eisenlohr-Moul, 2024).

Prospective daily ratings are required during two or more menstrual cycles to make a diagnosis of PMDD, given the essential peak before menses and remission of symptoms postmenses. In those with prospectively confirmed PMDD, research has demonstrated that ovarian steroid stabilization with the GnRH agonist leuprolide acetate diminishes PMDD symptoms, and the administration of E2 and P4 provokes PMDD symptoms (Schmidt et al., 1998), suggesting that E2 and P4 play a central role in triggering symptoms in susceptible individuals. Although the source of this susceptibility has not been fully identified, research has shown that women with PMDD are sensitive to changing hormones at the cellular level. Cells from women with PMDD exposed to E2 and P4 experienced changes in gene expression in a gene complex known to regulate epigenetic responses to sex steroids and the environment (Dubey et al., 2017; Marrocco et al., 2020). In those with PMDD, changes in gene expression were associated with changes in regional cerebral blood flow during P4 administration (Wei et al., 2021). Exposure to sex steroids alters gene transcription in those with PMDD and changes patterns of blood flow to the brain, which helps explain the emergence of symptoms during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. The reason some women experience epigenetic changes in response to E2 and P4, however, remains unclear.

Despite these scientific advances, significant difficulty remains in diagnosis and clinical management of PMDD. Prospective daily ratings are only used by 12 percent of clinicians who routinely diagnose PMDD, and research shows that diagnosing based on retrospective symptom recall results in a 60 percent false positive rate (Eisenlohr-Moul, 2024). Aside from the difficulty in diagnosis, many women with symptoms tied to their menstrual cycle are missed by the diagnostic system. Significant heterogeneity between individuals exists in the timing of symptom onset relative to ovulation and menses and the specific symptoms that occur (Eisenlohr-Moul, 2024). For example, PMDD excludes those with premenstrual exacerbation of chronic depressive disorder, even if the degree of symptom change is the same as in those with PMDD (Epperson et al., 2012).

In addition, PMDD does not capture the periovulatory changes in impulsive reward seeking or substance use seen in many individuals (Eisenlohr-Moul, 2024; Epperson et al., 2012). As a result, the classification system misses the majority of individuals with mood symptoms provoked or exacerbated by the menstrual cycle, leading to an underrepresentation of women with such mood changes in psychiatric research and an underestimation of the associated prevalence and costs. Basic, epidemiologic, and clinical research is therefore needed to advance the understanding of how much ovarian hormones modulate mood in women across the population, not just those who are identified as having PMDD. It is critical to expand the research base to more specifically determine the source of differential sensitivity to hormonal changes, identify more efficient and user-friendly methods of clinical assessment and diagnosis, identify treatments for not only PMDD but also the premenstrual exacerbation of other psychiatric illness, and, critically, develop and make evidence-based treatments accessible to the potentially millions of women affected.

PND

The causes of PND, a major depressive disorder that occurs during pregnancy or the 3 months following childbirth, have been difficult to disentangle because it is determined by multiple etiologic pathways (see Chapter 7 for information on its high burden). Both neuroendocrine and psychosocial factors contribute to the expression of illness, which implicate the complex interplay between HPG and HPA axes. Changes in the levels of E2 and P4 during pregnancy and postpartum trigger affective dysregulation in those susceptible to PND (Bloch et al., 2000) and regulate key nodes of a brain network responsible for motivation and reward responsiveness (Schiller et al., 2022).

The rapid antidepressant effects of allopregnanolone, a progesterone metabolite that modulates that gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, suggests dysfunctional GABA signaling in PND. Multiple trauma exposure, common to 65 percent of those with PND according to one study (Guintivano et al., 2018), and psychosocial stress, a known trigger of PND, alter GABA signaling (Meltzer-Brody and Kanes, 2020; Schalla and Stengel, 2024). Preclinical models have identified precise mechanisms by which changes in perinatal allopregnanolone levels trigger dysregulation of GABA signaling and provoke depression-like behavior in mice. Mice that lack the GABA-A receptor delta subunit are phenotypically indistinguishable from wild-type mice until the postpartum period, when they show deficits in maternal care that depend on corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) neurons and specifically the ability to suppress stress-induced activation of the HPA axis during the peripartum period, which is mediated by CRH neuron

activity (Maguire and Mody, 2008; Melón et al., 2018). Treatment with allopregnanolone modulates neural oscillations in the basolateral amygdala and motivated behavior, which are mediated by GABA-A receptor delta subunit (Antonoudiou et al., 2022).

Recent scientific advances in the neuroendocrine mechanisms of PND and its treatment may be seen as a success of NIH investment, but the path from basic discovery to clinical intervention has been slow (Patterson et al., 2024; Payne and Maguire, 2019). Two new pharmacologic agents—both GABA-A receptor modulators—have been FDA approved in the past 7 years, allowing for more rapid, targeted treatment of PND than ever before (FDA, 2019, 2023; Patterson et al., 2024). These advances also come with important caveats. Allopregnanolone has been a focus of scientific inquiry since the 1940s. Its calming effects and the mediating role of GABA receptors were discovered in the 1980s (Majewska et al., 1986). By the 1990s, researchers had identified its role in modulating stress and effect on HPA axis function in pregnancy (Morrow et al., 1995), yet despite these critical advances and interest from talented scientists around the world, discovery might have proceeded more quickly if funding research on the neuroendocrinology of PND had been a priority (Paul et al., 2020).

The Menopause Transition and the Brain

Mood Disorders

Research has demonstrated the role of ovarian steroids in perimenopausal depression. Depression onset occurs during the reproductive stage when E2 levels decline, and some studies suggest that rapid fluctuations in ovarian steroids trigger depression in susceptible women (Schweizer-Schubert et al., 2020). E2 administration—either by stabilizing sex steroid levels or by increasing levels—rapidly reduces perimenopausal depression symptoms (Schmidt et al., 2000), whereas blinded E2 withdrawal provokes depression symptoms in women who had experienced perimenopausal depression (Schmidt et al., 2015).

Work using induced pluripotent stem cells developed from women with perimenopausal depression show dysregulated gene networks, including those responsible for inflammatory response and estradiol response, and these differences in cellular gene expression may account for individual differences in mood response to depression in the context of perimenopausal hormone withdrawal and treatment (Rudzinskas et al., 2021). As with mood symptoms experienced during the other reproductive windows, recent scientific advances in the understanding of how hormones may regulate mood during perimenopause have not yet translated into novel treatments or improved access to clinical care. In addition, few preclinical models of

perimenopausal depression and anxiety exist, which has hampered the understanding of the triggering, neural pathways, and drug discovery. The standard of care relies on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, medications effective in fewer than 50 percent of women that were introduced to the market nearly 40 years ago (Hillhouse and Porter, 2015; Maki et al., 2019; Stute et al., 2020). Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) is also a standard recommendation for those with comorbid hot flashes (Maki et al., 2019). The most common form of MHT, conjugated equine estrogen (CEE), was approved by FDA in 1942 (Stefanick, 2005). Identification of neural targets for new, targeted pharmacologic agents is urgently needed, as are more information and educational resources for physicians and women about mental well-being during this important life transition.

Cognition and Dementia

Early menopause, either spontaneous or resulting from bilateral removal of the ovaries, especially before the age of 40–45, is associated with an increased risk of mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and dementia, and medial temporal lobe neurodegeneration (Bove et al., 2014; Gervais et al., 2020; Rocca et al., 2007, 2021; Zeydan et al., 2019). This risk is most pronounced among women who do not use MHT up until the age of 50. In addition, longitudinal declines in cerebral metabolism and hippocampal atrophy and increased brain amyloid-beta deposition are greater over the menopause transition compared with men of the same age, independent of the apolipoprotein E gene and cardiovascular risk factors (Mosconi et al., 2018). The underlying biological mechanisms that may explain these findings suggest that hormonal fluctuations and levels are critical to the development of this clinical syndrome and corresponding brain pathology. For example, compared with age-matched controls, reduced levels of 17-Beta-estradiol and testosterone are observed in female and male patients with AD (Barron and Pike, 2012)

There are three physiological estrogens in females, E1, E2, and E3, with E2 being the major product in the premenopausal period (Spencer et al., 2008). In addition to promoting dendritic growth, estrogen also has a protective effect on the brain through brain metabolism. Shifts in estrogens during the menopause transition could lead to the deficits seen in brain metabolism in AD, such as mitochondrial impairment, or disruption of neurogenesis and hippocampal atrophy in women with mild cognitive impairment (Fleisher et al., 2005; Long et al., 2012; Turek and Gąsior, 2023).

The protective effects of estrogen against amyloid-beta accumulation—the pathological hallmark of AD—are attributed to its influence on amyloid precursor processing, on clearance of amyloid-beta, and on the degradation

of amyloid-beta, in addition to reducing levels of hyperphosphorylated tau, a component of the neurofilament tangles seen in AD (Gandy and Petanceska, 2000; Li et al., 2000; Muñoz-Mayorga et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2011).

Despite these observations, data from clinical trials and translation approaches have been mixed. The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study remains the only randomized, placebo-controlled trial on MHT for primary prevention of dementia. It enrolled postmenopausal females with a uterus over 65 and randomized them to receive oral CEE plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) or a placebo; and females without a uterus received oral CEE or a placebo. The primary outcome was incident dementia and mild cognitive impairment. The results suggested that the risk of all-cause dementia was twice as high in the CEE/MPA group, translating to an additional 23 cases of dementia per 10,000 women per year. The group without a uterus did not reveal a significant effect on incidence of dementia or mild cognitive impairment. When data were pooled together from both arms, there was an increased risk of dementia for the active drug compared to placebo groups in late life (Shumaker et al., 2003, 2004).

Further analyses noted that cardiovascular risk factors did not modify the effects of hormone therapy on cognitive function, and brain magnetic resonance imaging studies found that ischemic brain volume did not differ between the hormone therapy and placebo groups. However, the rates of accumulation of white matter lesions and total brain lesion volumes were higher among females with a history of CVD treated with hormone therapy versus placebo (Coker et al., 2014; Volgman et al., 2019).

Results from more recently conducted randomized clinical trials suggest that the timing and type of MHT are important for cognitive decline—with data suggesting that initiating MHT shortly after the final menstrual period does not have either long-term detrimental effects on cognition or beneficial cognitive effects (Espeland et al., 2013; Gleason et al., 2015; Henderson et al., 2016; Jett et al., 2022). The use of MHT remains controversial, with difficulty interpreting the data from studies due to differences in the timing of hormone therapy initiation in relation to menopause, the type of hormone treatment, characterization of comorbidities, such as CVD and AD risk of the participants, study design (clinical trial vs. observational study), outcome metrics (measure of cognition or neuroimaging modality), and sample size.

These findings collectively highlight the need to conduct further randomized clinical trials and studies that examine the effect of perimenopause or early postmenopause hormone replacement therapy administration on cognitive function, neuroimaging markers, and APOE4 carrier status to examine potential differences in the mechanistic basis of cognitive function and decline in women.

Summary of Hormonal Associations with Mental Health Disorders

Half the U.S. population will experience menopause should they live long enough, and the majority of women will have clinically significant symptoms (Peacock et al., 2023). Given the large number of affected people who will require clinical intervention, research is needed to guide the understanding of the pathophysiology such that illness expression can be prevented or treated effectively. Simultaneously, research focused on the clinical management of symptoms with existing treatments is sorely needed. Although risk of depression is elevated during and after the menopause transition, no randomized controlled trials have ever examined the comparative effectiveness of existing treatments for perimenopause-onset depression (Badawy et al., 2024; Bromberger et al., 2011). Moreover, since women comprise the majority of both the workforce and unpaid caregiving roles in the United States, preserving cognition and preventing dementia as they age is of high importance (Stall et al., 2023). The largest and most comprehensive large-scale, randomized, placebo-controlled trial for primary prevention, however, was completed over 20 years ago and conducted only in postmenopausal women, once illness progression may have already started (BLS, 2023; Hays et al., 2003).

The lack of well-powered clinical trials has left a large gap in knowledge essential for guiding the clinical care of midlife women in the menopause transition. Given that more recent research has demonstrated that hormone therapy may be safe when initiated earlier, with certain hormone formulations, and in subgroups of women with differential risk factors—accounting for those with AD risk and CVD, for example—additional large-scale, randomized, controlled trials are needed to disentangle the effects of hormonal treatments on cognition from the effects of aging and other risk factors and examine their synergistic effects on both risk and resilience (Cho et al., 2023; Faubion et al., 2022).

HORMONAL ASSOCIATIONS WITH PHYSICAL HEALTH DISORDERS ACROSS THE LIFE COURSE

Cancers Across the Life Course

Hormone-dependent cancers include breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers (Hoadley et al., 2018). Risk factors for estrogen-dependent cancers include high natural endogenous levels, hormone replacement therapy, obesity, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) appear to reduce the risk of epithelial ovarian and endometrial cancer (American Cancer Society, 2024). OCP use is also associated with a decreased risk of colorectal cancer (Murphy et al., 2017). In contrast, oral

contraception appears to increase the risk of breast cancer, and long-term use is associated with increased cervical cancer risk (American Cancer Society, 2024; Asthana et al., 2020; Barańska et al., 2021; NCI, 2018). Prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol, an artificial estrogen no longer in use, is a risk factor for clear cell cervical and vaginal cancers in females exposed in utero (White et al., 2022). Tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator commonly used to treat breast cancer, is associated with a higher risk of uterine malignancies, including endometrial cancers and uterine sarcomas (American Cancer Society, 2024).

Excess body weight or gaining weight during adulthood and physical inactivity are associated with numerous cancers, including female-specific cancers (American Cancer Society, 2024). The link between obesity and hormone-dependent cancers may be related to hormonal synthesis in adipose tissue, leading to heightened circulating estrogen levels. Hormonal signaling pathways have been implicated in modulating cell growth, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis (Ranhotra, 2022). Thanks to a large and sustained investment in breast cancer research, the relationship between estrogen and breast and endometrial cancers is much better understood compared to cancers such as ovarian and cervical, indicating an important knowledge gap.

Breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers are more prevalent after menopause (Barry et al., 2014). The role of exogenous hormones and female-specific cancers is variable. For instance, high levels of estrogen, testosterone, and P4 increase breast cancer risk. In contrast, high levels of estrogen increase endometrial cancer risk, while progestins are protective. As described, after the initial Women’s Health Initiative study, the use of combination estrogen and progesterone declined significantly, and some authors have speculated that the increasing incidence in endometrial cancer may be the result of decreased use of combination hormone replacement therapy, prolonged use of vaginal estrogens, or use of compounded bioidentical hormone therapy (Constantine et al., 2019).

Hormonal therapy is used to treat select patients with breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancer. For breast cancer, endocrine therapy with or without ovarian suppression/ablation is considered for patients with hormone receptor–positive cancers and based on risk of recurrence (Burstein et al., 2016). Endometrial cancers can be treated with several hormonal strategies, including megestrol acetate, medroxyprogesterone acetate, alternating tamoxifen with megestrol acetate, and an aromatase inhibitor (NCCN, 2023). Levonorgestrel intrauterine devices and oral progestins are used to treat patients with endometrial cancer who desire fertility or are not surgical candidates (NCCN, 2023). Hormonal therapy is used to treat patients with low-grade serous ovarian cancers and sex-cord stromal tumors (NCCN, 2024).

Breast and hormone-dependent gynecologic cancers share many similarities. Their development is in part driven by hormonal factors, and treatment options include hormonal therapies, aromatase inhibitors, and ovarian suppression/ablation. A better understanding of steroid sex hormone pathophysiology, role of signaling pathways, and mechanisms of carcinogenesis is needed to identify additional preventive and treatment strategies.

Reproductive and Postreproductive Years

Endometriosis is the presence of endometrium-like tissue outside of the uterine cavity—most often in the pelvic peritoneum and ovaries—leading to inflammation and scarring. Endometriosis and intrauterine endometrial tissue both respond to estrogen and P4 similarly, resulting in endometriosis proliferation and inhibition of endometrial growth, respectively. Ectopic endometrial tissue, however, does not respond as predictably to progestin and native progesterone, as it has a different secretory pattern of cytokines and prostaglandins, steroid biosynthesis and metabolism, and steroid receptor content (Bulun, 2016). This may explain why hormonal treatments are not effective in curing the disease and recurrence is common. Further research on its pathogenesis is needed in human and nonhuman primate models to identify nonsurgical diagnostic and treatment approaches that would significantly improve health and quality of life for millions of women. Similarly, additional research is needed to understand the role of estrogen, P4, and other hormones in the development of uterine fibroids and pelvic floor disorders, conditions that significantly affect quality of life for women during their reproductive and nonreproductive years (see Chapter 7).

Menopause, Hormones, and Cardiometabolic Disorders

Menopause as a Critical Transition for Cardiometabolic Health

During and after the menopausal transition, key changes in cardiometabolic health occur, notably the accumulation of risk factors resulting from changing hormonal profiles. These changes, including alterations in blood pressure trajectory and lipid profiles and increased visceral adiposity, contribute to increased risk of postmenopausal heart disease and stroke (Madsen et al., 2023; Samargandy et al., 2022). For example, in a longitudinal analyses of participants from the Women’s Health Initiative, increases in FSH over a 5-year period were associated with increasing total body fat, total body fat mass, and subcutaneous adipose tissue (Mattick et al., 2022). Developing central obesity after menopause is of particular concern, as it confers a higher risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, independent of body mass index (Sun et al., 2019).

Lipid profiles also change in peri- and postmenopause, and this may include increases in low-density lipoprotein, total cholesterol, apolipoproteins, and triglycerides and a decrease in the protection from high-density lipoprotein (Holven and Roeters van Lennep, 2023; Torosyan et al., 2022). Vascular aging and changes in endovascular function in peri- and postmenopause further contribute to changes in risk of CVD (Moreau and Hildreth, 2014), and data suggest sex-specific associations between endogenous sex hormones and measures of arterial stiffness, a key contributor to hypertension (Subramanya et al., 2018). Finally, though increasing blood pressure is known to occur with chronological age, data suggest an additional contribution from reproductive aging and changes in hormones occurring during the perimenopause transition (Samargandy et al., 2022).

Endogenous Hormones and Risk of Cardiometabolic Disease

Directly related to changes in cardiometabolic profiles during peri- and postmenopause, overall, data indicate key associations between endogenous sex hormones levels and cardiovascular endpoints and risk factors among postmenopausal women. Estrogen-level changes measured in postmenopausal women, however, do not seem to fully explain the increasing risk of CVD (Hu et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2018). Despite some conflicting data on the association between endogenous estrogen and cardiovascular endpoints (Hu et al., 2020), data on sex hormone–binding globulin, a sex steroid transporter that helps to regulate circulating testosterone and estrogen and can act independently of sex steroids, is inversely associated with clinical diabetes, coronary heart disease, and stroke with some evidence for causality (Ding et al., 2006, 2009; Kalyani et al., 2009; Li et al., 2023; Madsen et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2024). Furthermore, despite data indicating a role for androgens in the etiology of CVD in men (Zhang et al., 2022), an adequate understanding of that role and the change in androgen-to-estrogen ratio in the cardiovascular health of older women is lacking (Rexrode et al., 2003), which is an area where research is needed (Sohrabji et al., 2019).

Osteoporosis

Menarche is associated with increased circulating levels of estrogen, and this results in a rapid gain in bone mass from ages 12 to 20, with women achieving their peak bone mass by approximately age 20 (Clarke and Khosla, 2010). Bone remains strong through the childbearing years as a result of the steady levels of estrogen and progestins through normal menstrual cycles (Clarke and Khosla, 2010; Seifert-Klauss and

Prior, 2010). Women maintain most of their bone mass until they enter perimenopause, when the sustained reduction in estrogen levels results in uncoupled bone remodeling, yielding increased resorption relative to formation (Clarke and Khosla, 2010). There is a rapid turnover of bone and a rapid loss of trabecular, or spongy, bone which is the porous component of bone that is highly enriched in the spine and, along with the cortical shell, gives bone its strength (Ott, 2018; Walker and Shane, 2023). Studies of women’s bone mass through their life course found rapid bone loss within 10 years of the menopause transition, especially estrogen-sensitive trabecular bone in the lumbar spine, pelvis, and hips (Finkelstein et al., 2008; Nilas and Christiansen, 1988). This is followed by slow, steady loss that disproportionately affects trabecular/spongy bone (Finkelstein et al., 2008; Ji and Yu, 2015; Seeman, 2013; Walker and Shane, 2023). Over time, this bone loss leads to low bone mass and strength, culminating in osteoporosis, frailty, and increased risk of fractures, especially in the vertebra (Clarke and Khosla, 2010). However, women do generate estrogen from fat stores, which can slow some of the bone loss (Frisch et al., 1980; Gimble et al., 1996; Hetemäki et al., 2021). The natural onset of menopause is not the only condition that triggers significant bone loss. For example, millions of female breast cancer survivors use anti-estrogen therapies (aromatase inhibitors) for up to 10 years (Diana et al., 2021; Pineda-Moncusí et al., 2020; Shapiro, 2020). While these can reduce the risk of breast cancer reoccurrence, they can have a significant toll on bone quality and ultimately lead to unhealthy aging. Another group experiencing premature bone loss are those who undergo surgery to remove the ovaries, and while they are often prescribed hormone replacement therapy, it does not fully counteract that bone loss (Hibler et al., 2016). The risk of osteoporosis is higher in White and Asian compared to Black women, but the role of estrogens in this is not well understood (Office of the Surgeon General, 2004).

Despite medications that have been approved and are effective in preventing fractures of the lumbar spine and hip in elderly women and men, the best way to prevent osteoporosis is to achieve a high peak bone mass (IOF, n.d.; Rosen, 2000). No approved pharmacological treatments augment peak bone mass, which is affected by a combination of genetics, dietary choices that affect the intake of calcium and vitamin D, physical activity, and regular menstrual cycles (Rosen, 2000; Zumwalt and Dowling, 2014). Estrogen, however, remains a major prevention therapy for osteoporosis, and the timing and duration of use relative to the menopause transition to maximize bone and joint health is an area of continued investigation (Adler et al., 2016; Grigoryan and Clines, 2024; Rosen, 2000; Silverwood et al., 2015).

Hormonal Considerations Across the Life Course for Transgender Individuals

Transgender individuals (XY women/girls and XX men/boys) have unique hormonal considerations across the life course, as outlined in the 2023 Endocrine Society Scientific Statement on Endocrine Health and Healthcare Disparities in Pediatric and Sexual and Gender Minority Populations (see Box 5-3) (Diaz-Thomas et al., 2023). Gender-affirming hormone therapy in transgender youth includes sex hormones and pubertal suppression with GnRH agonists. The long-term effect of these interventions on statural growth, CVD risk, bone mineral density, and reproductive health in both transgender women and men need further study. Tall stature in transgender girls may contribute to psychological distress, which may require rapid escalation of estrogen to facilitate closure of the epiphyses (Shumer and Araya, 2019). Similarly, for transgender boys, escalating testosterone therapy more slowly can provide a longer period of statural growth and greater height attainment to address short stature (Shumer and Araya, 2019). The effect of GnRH agonist therapy on final adult height and further manipulation of growth with additional therapies, such as aromatase inhibitors and growth hormone, require further investigation in transgender girls and boys (Diaz-Thomas et al., 2023; Roberts and Carswell, 2021).