A New Vision for Women's Health Research: Transformative Change at the National Institutes of Health (2025)

Chapter: 6 Women, Health, and Society

6

Women, Health, and Society

INTRODUCTION

The previous chapter illustrates the role that biological factors, such as chromosomes and hormones, have on women’s health. Biological sex shapes health in many ways, potentially offering vulnerability or resilience to various health conditions (NASEM, 2024a). However, women’s health is also strongly shaped by the social and structural context of their lives, including their income and wealth, education, employment, location, family structure, and larger structural and policy forces. The social factors that contribute to gendered differences in men’s and women’s lives can also interact with each other and with biological differences, confounding or exacerbating the latter. Consequently, the health differences seen between women and among women compared to men are products of social and biological factors. Moreover, other identities, including gender identity, race, ethnicity,1 and sexual orientation, shape women’s health. These biological and social and structural factors intersect and can be bidirectional.

This chapter provides a high-level overview of how structural and social determinants of health can influence women’s health, illustrating why the national research agenda needs to specifically focus research investments to

___________________

1 As discussed in Chapter 1, this report strives to be consistent in its use of the following terms to describe specific racially and ethnically minoritized populations: “American Indian or Alaska Native,” “Asian,” “Black,” “Hispanic or Latino/a/x/e,” “Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander,” and “White.” However, when describing data from cited studies, the terminology from source papers is used, introducing differences in language. This is also the case with the report’s use of LGBTQIA+ and similar variations, such as LGBT, LGBTQ, and LGBTQ+. This is especially common in this chapter.

better understand how these factors shape the health of girls and women as it seeks to develop solutions to improve their health and well-being. While the structural and social determinants cover a large range of domains, this chapter offers an overview of select examples.

STRUCTURAL AND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Healthy People 2030 organizes the social determinants of health (SDOH) into five domains: health care access and quality, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment, social and community context, and education access and quality (OASH, n.d.-a). The structural determinants of health are the

macrolevel factors, such as laws, policies, institutional practices, governance processes, and social norms that shape the distribution (or maldistribution) of the SDOH (e.g., housing, income, employment, exposure to environmental toxins, interpersonal discrimination) across and within social groups. Structural determinants of health, also referred to as the ‘determinants of the determinants of health,’ include structural racism and other structural inequities and thus influence not only population health but also health equity. (NASEM, 2023b)

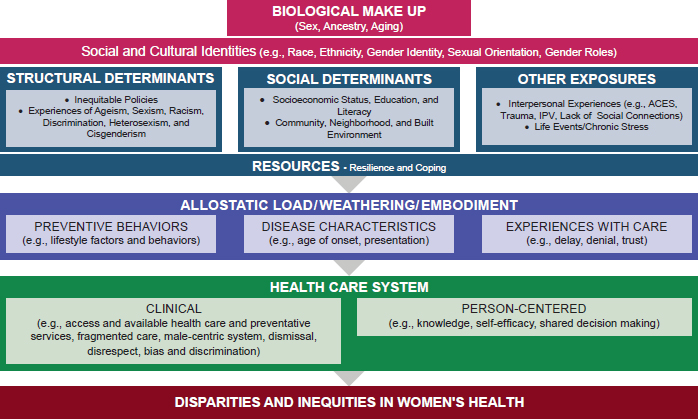

The 2024 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) report Advancing Research on Chronic Conditions in Women provides an overview as well as research gaps on the structural and SDOH as they specifically affect women, including structural sexism and health policy (NASEM, 2024a). See Figure 6-1 for a visualization from that report showing how biological, social, and structural determinants can affect women’s health. As that report highlighted, gender-related social and cultural factors can lead to diverse exposures and experiences within the framework of structural and social determinants of health. These factors, through a range of mechanisms, affect not only preventive behaviors but also the onset, characteristics, and progression of various health conditions (NASEM, 2024a). In addition, women often face unique challenges in the health care system, including differences in clinical practices and patient-centered care, which can further influence their health outcomes. For example, weathering (see Figure 6-1) refers to the cumulative negative effect of chronic stress from social and economic adversity on the physical health of marginalized groups and results in premature biological aging and increased health vulnerability. It can yield adverse health outcomes (Geronimus et al., 2006; Simons et al., 2021).

Women navigate the world in ways distinct from men, and women who are additionally marginalized because of other facets of their identity face unique and additional challenges, making health equity a crucial

SOURCE: Adapted from NASEM, 2024a.

consideration within women’s health. If equality is defined as treating all individuals in the same manner, it is important to emphasize that equity is not interchangeable. Equality assumes a level playing field for everyone without accounting for historical and current inequities. According to the World Health Organization, “equity is the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, [or] geographically” (WHO, n.d.). In other words, equity is the process, and equality is the outcome. Equity focuses on justice (NASEM, 2023b).

In many areas, women experience not only differences in health outcomes compared to men but also inequities in health and health care. Health and health care inequities are driven by structural and social determinants, meaning they are more than just “differences.” For example, the 2020 National Academies report Birth Settings in America: Outcomes, Quality, Access and Choice describes structural inequities and biases, including racism, on the systemic, institutional, and interpersonal levels that underlie SDOH for racially and ethnically minoritized women (NASEM, 2020a). Systematic oppression related to race, sexual orientation, gender identity, age, weight, ability, and more are especially harmful to women, who also experience sexism and misogyny. In addition, laws and policies are important macrolevel factors for consideration (Everett and Agénor, 2023; Jahn et al., 2023; Zubizarreta et al., 2024). These factors combined have contributed to deprioritizing and undervaluing women’s health research (WHR). The remainder of this chapter outlines how social and structural

determinants drive inequities in women’s health and WHR, including consideration and examples of how the intersectional identities of women who are racially and ethnically minoritized, disabled, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, or otherwise marginalized further shape outcomes, and illustrates why these need to be considered in the development of the nation’s research agenda on women’s health.

STRUCTURAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Discrimination

Sexism

Structural sexism is “systematic gender inequalities between men and women in power and resources, as manifest in institutions, interactions, and individuals” (Homan, 2021). It is reflected in policies and institutions, such as how many women participate in the labor force, the ratio of men’s to women’s median weekly earnings, poverty rates, and percent of state legislative seats occupied by men versus women (Homan, 2019). Researchers have begun to explore how structural and systemic forms of gender-based discrimination affect women’s health (Homan, 2019; Krieger, 2001, 2014; Philbin et al., 2024). For example, data suggest that bias against women in the workplace negatively affects women’s health and, furthermore, that women living in states with high levels of structural sexism have approximately twice as many chronic health conditions compared to women in states with lower levels (Cunningham and Wicker, 2024; Homan, 2019). The health effects are substantial—women exposed to high structural sexism appear to have a health profile about 7 years older than women in low-sexism states (Homan, 2019). Additionally, structural sexism amplifies other forms of discrimination, such as structural racism, ableism, hetero-sexism, and classism, compounding negative health effects for women with multiple marginalized identities (Homan, 2019, 2021; Perry et al., 2013). For example, Everett et al. (2022a, 2024b) have linked structural heteropatriarchy (i.e., the combined impact of structural sexism and discrimination against lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations) to increased risk of preterm birth, decreased birthweight, and maternal cardiovascular morbidities. Moreover, the effects from such discrimination accumulate over time to affect women’s health (Kelley and Gilbert, 2023).

Studies have also shown that structural sexism affects women’s access to health care. For example, researchers examined state-level sexism using state-level indicators of administrative data, such as the ratio of men-to-women earnings, employment, poverty rate, and paid family leave policy,

and their effect on access to health care. Higher state-level sexism was associated with greater barriers to accessing health care and affordability for Black and Hispanic but not White women, illustrating the effect of intersectional structural discrimination that racially and ethnically minoritized women face (Rapp et al., 2021).

Beyond access to health care, studies have examined the effect of structural sexism on the use of preventive health care, cesarean-section rates, breastfeeding, and disordered eating (Balistreri, 2024; Beccia et al., 2022; Dore et al., 2024; Nagle and Samari, 2021; NASEM, 2024a). Gender discrimination is also a major source of stress that directly affects mental health. Women who report experiencing discrimination are more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety (Vigod and Rochon, 2020). Moreover, research suggests there are fewer gender differences in mental illness rates in more gender-equal societies, suggesting discrimination may play a major role in these disparities (Yu, 2018). Future research on measuring structural sexism needs to consider the longitudinal nature of its effects, as most studies are cross-sectional; capture dynamic and complex ways in which systems of oppression affect women’s health; and identify strategies to intervene (Beccia et al., 2024; Homan, 2019).

Racism, Colonialism, and Health Outcomes

A long history of colonialism and racism, reflected in policies, systems, and communities, drive U.S. health inequities (KFF, n.d.; NASEM, 2017, 2023b). The 2023 National Academies report Federal Policy to Advance Racial, Ethnic, and Tribal Health Equity details this history of racism, discrimination, and colonialism; its effect on health outcomes; and the need to address these root causes (NASEM, 2023b); to do so, research needs to account for these underlying structural causes to understand how they affect human biology and the ability to access needed services to prevent, diagnose, and treat health conditions.

Colonialism

Colonialism involves control of “people [and] the context of their lives—control of the economy through land appropriation, labor exploitation, and extraction of natural resources; control of authority through government, normative social institutions, and the military; control of gender and sexuality through oversight of the family and education; and control of subjectivity and knowledge through imposition of an epistemology and the formation of subjectivity” (IOM, 2013, p.13). The American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) population is a salient example in which colonialism affects health. To advance health for AIAN women, it is essential to

understand the history of colonialism and how it continues to reverberate through all aspects of health at systems, community, and individual levels.2

The effects of colonialism have created modern health inequities through violence, targeted eradication of AIAN people, erasure of culture, dispossession of land, removal from tribal homelands, forced urbanization, and more (Brown-Rice, 2013; Carroll et al., 2022; Moss, 2019; NASEM, 2023b). AIAN women have been threatened with forcible removal of their children and endured forced sterilization (Newland, 2022; Stern, 2020). The forcible placement of AIAN children in boarding schools and non-AIAN homes has also resulted in cultural eradication (Newland, 2022). These historical events have negatively affected AIAN women’s health, creating inequities in cancer, heart health, mental health, maternal mortality, violence, and more (American Heart Association, 2023; CDC, 2023a; KFF, 2022a; Kwon et al., 2024; Moss, 2019; NASEM, 2017, 2023b; Petrosky et al., 2021; Statista, n.d.; Urban Indian Health Institute, n.d.).

For example, the pregnancy-related death rate among AIAN women is nearly double that in White women (26.2 per 100,000 vs. 13.7) (KFF, 2022a). A review of pregnancy-related deaths among AIAN populations finds that about one in three is attributable to mental health conditions (Trost et al., 2022). Moreover, 2020 data suggest that approximately 92 percent of AIAN maternal mortality is preventable (CDC, 2024).

Like other health disparities affecting AIAN people, mental health outcomes need to be considered in the context of historical trauma resulting from colonialism. Suicide is one of the leading causes of mortality among AIAN people (Statista, n.d.). Although negative mental health outcomes are of great concern for AIAN women, the literature on AIAN mental health research is scant (Kwon et al., 2024). These health inequities exist, but it is important that solutions be framed to include community assets and viewed in terms of attaining balance among the components necessary for health and well-being in alignment with an Indigenous model of health, a concept based on the Medicine Wheel3 (Greer and Lemacks, 2024; National Library of Medicine, n.d.).

When studying SDOH, it is also important to understand the Indigenous SDOH—that is, the factors that impact the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples uniquely. Seven Directions, the first national public health institute in the United States to focus solely on health and wellness for Indigenous people, asserts “[Indigenous SDOH] could include our

___________________

2 The report Federal Policy to Advance Racial, Ethnic, and Tribal Health Equity provides a detailed history of tribal health and how it has led to significant health inequities (NASEM, 2023b).

3 “The Medicine Wheel, sometimes known as the Sacred Hoop, has been used by generations of various Native American tribes for health and healing. It embodies the Four Directions, as well as Father Sky, Mother Earth, and Spirit Tree—all of which symbolize dimensions of health and the cycles of life” (National Library of Medicine, n.d.)

connection to our traditional lands, tribal sovereignty, tribal governance, our unique tribal or urban Indian health care system, the access we have to our traditional lifeways, native languages, traditional foods, ceremonies, relationships, and many more factors. The process of mapping social determinants of health with and for AIAN communities can and should include the factors or conditions that are only found in our tribal or urban Indian settings” (Seven Directions: A Center for Indigenous Public Health, 2023). These are all essential factors to consider not only for research (e.g., including tribal consultation) but also when developing programs, policies, and laws impacting AIAN communities.

Racism

Racism is a structural system resulting from the intersection of social and institutional power and racial prejudice. Policies, practices, and attitudes within this system operate to constrain or enhance access to resources, privileges, and advantages based on race. These privileges disproportionately accrue to some groups and are withheld from others according to social constructions of race and ethnicity (NASEM, 2023b). The psychological toll of racism can directly harm physical and mental health; it increases cortisol levels and weakens the immune system (Berger and Sarnyai, 2015; Chen and Mallory, 2021). In addition, chronic stress from racism is linked to increased risk of hypertension and poorer health at earlier ages (Dolezsar et al., 2014; Geronimus et al., 2006; Hicken et al., 2014).

As discussed in Chapter 2, Black women in the United States experience significant negative health outcomes relative to White women, such as early menopause transition with more severe symptoms, higher fibroid incidence, higher rates of pregnancy-related adverse events, and higher incidence of chronic conditions, such as heart disease and diabetes (Chinn et al., 2021; Harlow et al., 2022; Howell, 2018; Katon et al., 2023). Pregnancy-related mortality is highest among Black women, at 41.4 per 100,000 compared to 13.7, 11.2, 14.1, and 26.2 for White, Hispanic, Asian and Pacific Islander, and AIAN women, respectively (KFF, 2022a). Black, AIAN, Asian, and Pacific Islander women are more likely to experience preterm births, low-birthweight babies, or births after late or no prenatal care compared to White women (KFF, 2022a). Black women are almost two times more likely to experience infertility than White women, and Black, Latina, and Asian women are less likely to receive infertility and fertility preservation treatments (Dongarwar et al., 2022; Weiss and Marsh, 2023). The continuing effects of structural racism, rooted in a history of slavery and colonialism, impede advancing the health of Black women (Bleich et al., 2024), who constantly need to negotiate their identities based on a past entrenched in oppression, which influences their social interactions, mental health, and access to opportunities (Presumey-Leblanc and Sandel, 2024).

Hispanic and Latina women are more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer at a more advanced stage, experience higher mortality rates from it, and, as breast cancer survivors, face a higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and related mortality compared to non-Hispanic White women (Gonzalo-Encabo et al., 2023; Paz and Massey, 2016). Black and Hispanic patients are significantly less likely than White patients to have minimally invasive surgery for uterine fibroids and more likely to undergo hysterectomies (Eltoukhi et al., 2014; Katon et al., 2023). These disparities reflect broader issues of racism and discrimination, which contribute to unequal access to health care and SDOH, exacerbating the health inequities faced by these communities.

Furthermore, research on structural determinants of health, including racism, is hampered by shortcomings in data collection and measurement of structural racism and other forms of discrimination (Hing et al., 2024; NASEM, 2023b). In addition, what the research enterprise considers “science” impacts the role of race and ethnicity and the types of studies conducted. For example, community-engaged research—representing a spectrum of approaches where community members and organizations and/or researchers collaborate—can be used to better identify mechanisms to prevent and address complex health issues impacted by bias, racism, and the structural and social determinants of health. These tools are underused and will be important to apply in future WHR (NASEM, 2024a; Wallerstein and Duran, 2006).

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Intersex, and Asexual (LGBTQIA+) Discrimination

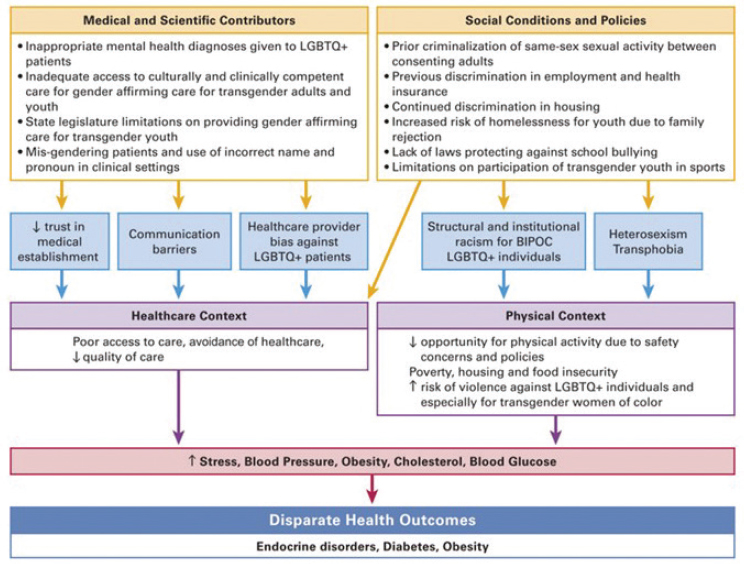

Sexual and gender minorities (SGM), including lesbian, bisexual, Two-Spirit, queer, and transgender and nonbinary (TNB) individuals, also experience unique challenges and barriers to health and health care compared to heterosexual cisgender women and men. While the term “TNB” is used throughout this chapter, the focus is on the ways social and structural determinants of health affect transgender women as well as transgender men and nonbinary individuals assigned female sex at birth. SGM are subject to marginalization and stigma that can have a number of downstream effects, such as poorer economic outcomes and increased vulnerability to interpersonal violence (Badgett et al., 2019; Coston, 2023; Flores et al., 2021; Movement Advancement Project and Center for American Progress, 2024; National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, 2018; Peitzmeier et al., 2020). On medical and biological dimensions, for example, when seeking gender-affirming care, TNB individuals sometimes need to navigate discrimination from health care providers and barriers to such care. Figure 6-2 shows a framework for multilevel social and structural determinants of health outcomes in SGM populations (Diaz-Thomas et al., 2023). The later sections

NOTES: LGBTQ+ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual. Although not defined in the figure source, the acronym BIPOC can be used to refer to individuals who are Black, Indigenous, and people of color.

SOURCE: Diaz-Thomas et al., 2023. © Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Endocrine Society. All rights reserved.

of this chapter elaborate on several of these challenges and how they can affect health and well-being.

LGBT youth and young adults experience increased stress, labeled “minority stress,” particularly during the pubertal transition (Mason et al., 2023). The minority stress model was introduced by Dr. Virginia R. Brooks (later known as Winn Kelly Brooks) in her 1981 book Minority Stress and Lesbian Women (Brooks, 1981). It proposes that members of minoritized communities experience specific and additional stressors compared to the everyday stress majority populations experience over the life-span (Meyer, 2003). Over time, this can lead to activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, one of the body’s stress response systems, affecting physical and mental health (Diaz-Thomas et al., 2023; Hatzenbuehler and McLaughlin, 2014).

Although limited and underfunded, research points to unique sexual and reproductive health barriers among sexual minority women (SMW).

For example, compared to heterosexual women, SMW, including lesbian and bisexual women, may be more likely to experience pregnancy loss, stillbirth, low birthweight, and preterm birth (Charlton et al., 2020) and be at higher risk of developing cervical cancer (American Cancer Society, 2024). Data from Everett et al. suggest that these outcomes may be attenuated by policies that confer protections for SMW (Everett and Agénor, 2023; Everett et al., 2022b, 2024a). Contraceptive access is another area of concern; unintended pregnancy is higher among SMW compared to their heterosexual peers. Research on sexual and reproductive health inequities among racially and ethnically minoritized SMW remains especially limited (Agénor et al., 2021; Higgins et al., 2019).

For AIAN populations, gender is not a dichotomy of male or female. Precolonialism views on gender varied by tribe, with traditional languages including more than two genders. One modern term that applies only to Indigenous people is “Two-Spirit” (NASEM, 2020b; RRC Polytech, 2024). Two-Spirit people often face discrimination and marginalization from multiple directions. For example, they may experience racism and exclusion from non-Native LGBTQ communities, and within Native communities, they may encounter homophobia, transphobia, and rejection of their Two-Spirit identity (Tribal Information Exchange, n.d.). In broader society, Two-Spirit people face intersecting discrimination based on their racial, ethnic, gender, and sexual identities. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) funds little research on health outcomes for this population, with only three current NIH-funded studies with “Two-Spirit” in the title, abstract, or keywords based on a keyword search of RePORTER in October 2024 (NIH, n.d.). However, the limited evidence shows the discrimination Two-Spirit people face may contribute to health disparities, such as high rates of physical and sexual assault victimization, increased risk of mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety, greater likelihood of substance abuse, and elevated suicide risk (Robinson, 2022; Tribal Information Exchange, n.d.).

Weight Bias

Weight bias, also known as weight stigma, “refers to the negative attitudes, beliefs, stereotypes and discriminatory behaviors directed toward individuals based on their body weight or size” (Edwards-Gayfield, n.d.). This can manifest in various forms, including social exclusion and unfair treatment in both personal and professional settings. In health care, weight bias may lead to patients with higher weights receiving inadequate care, being blamed for their health conditions, or facing barriers to accessing necessary services. Weight bias often results in people seeking care later, avoiding it altogether, or receiving suboptimal treatment, which can exacerbate existing health issues and further marginalize this population (Lawrence et al., 2021). Furthermore,

the lack of investment in developing medical technology and resources to care for people along the weight spectrum, such as too few magnetic resonance imaging devices sized for large bodies, creates problems with care and likely affects overall health (Brydon, 2022; Kukielka, 2020; Ordway, 2023).

Some research indicates that weight bias is more prominent for women than men, and women report more internalization of it than men, meaning they are more likely to have self-disparaging thoughts and feelings because of their weight (Sattler et al., 2018). Women, particularly those with higher weights, often face greater societal pressure regarding body image and are more likely to experience weight-related stigma in various aspects of life, including health care (Puhl and Heuer, 2010; Voges et al., 2022). Furthermore, Black and Hispanic women are, on average, heavier than White women, indicating a likely intersectional component to the experience of racialized weight stigma in society and health care (OMH, 2024a, 2024b; Strings, 2019).

Despite growing awareness of weight bias and its impact, a significant gap remains in research on how it mediates and moderates adverse health outcomes, particularly for individuals with higher weights. This gap is particularly critical given that weight bias can exacerbate disparities in health care access and treatment, compounding the challenges faced by those with higher weights and potentially leading to worse health outcomes. Addressing this gap is essential to comprehensively understanding and mitigating the effects of weight bias on overall health.

Disability

Disability4 is an important consideration when undertaking research on women’s health—across all ages, women have slightly higher rates of disability compared to men, and this gap widens with age (Office of Disability Employment Policy, 2021). Women with disabilities experience significant employment barriers compared to both nondisabled women and men with disabilities. Their employment rate (20.5 percent in 2023) is lower than both disabled men (24.8 percent) and nondisabled women (60.3 percent). Women with disabilities also earn less than men with disabilities (Ives-Rublee and Neal, 2024). This economic disparity leads to limited access to the positive SDOH (Friedman, 2024).

In general, women with disabilities have difficulty affording health care, medications, and other health-related needs (CDC, 2023b); those who face poverty, unemployment, and unmet health care needs because of financial

___________________

4 Disability can be defined differently across the relevant literature, with some relying on individuals with disabilities to self-report and others relying on questions about diagnosed conditions or functional capacity.

constraints are also more likely to suffer from heightened mental distress (Cree et al., 2020). Women with physical, intellectual, or sensory disabilities face a wide range of sociocultural and structural factors that negatively affect their access to health care services, including reproductive health services, such as sexual education, contraceptive care, and pregnancy-related care, but this research is limited (Biggs et al., 2023; CDC, 2023b; Matin et al., 2021; Ransohoff et al., 2022).

Laws and Policies

Laws and policies are critical structural determinants of women’s health. The following discussion provides a few examples focused on reproductive rights and rights for SGM.

Reproductive Rights and Justice

Reproductive justice, which encompasses the right to access reproductive health care and the socioeconomic and racial factors that influence health outcomes, is an important example for understanding the effect of structural determinants on women’s health (SisterSong, n.d.). Addressing reproductive rights and health through this lens provides a comprehensive approach to improving women’s overall health and well-being.

Regarding laws and policies, reproductive health and rights frameworks tend to focus on rights to abortion and contraception access. For example, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization,5 which struck down decisions guaranteeing abortion care access at the federal level, has resulted in abortion bans and early gestational restrictions with direct effects on those seeking abortion care in nearly half the country (KFF, 2024; NASEM, 2023b). This case is a defining moment regarding women’s health and rights to bodily autonomy, and research has already identified numerous negative effects on women’s health care access and health outcomes (Ahmed et al., 2023; Thornburg et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2024; Zhu et al., 2024). These laws also interact with broader structural determinants to shape women’s and girls’ sexual and reproductive health outcomes. For example, restrictive abortion laws are linked to higher levels of preterm birth and low birthweight among Black people compared to non-Black people (Redd et al., 2021).

However, a reproductive justice framework extends the work of reproductive rights and health by identifying and addressing a set of gendered, racialized, and economically determined structural determinants of health. The term “reproductive justice” was coined in the 1990s as a Black feminist

___________________

5 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, No. 19–1392, 597 U.S. 215 (2022).

response to White feminist movement approaches to reproductive health and rights (SisterSong, n.d.). It was intentionally intersectional, meaning that the goal was to include the myriad ways Black, Latina, AIAN, and other racially and ethnically minoritized women, as well low-income White women, in particular experienced threats to bodily autonomy and reproductive dignity, something largely excluded from early feminist movements that centered on middle class and wealthy White women. Reproductive justice as a movement and conceptual framework made more explicit that true reproductive freedom had to include rights to have a child under the condition of one’s choosing (SisterSong, n.d.). This was responsive to injustices faced by Black, Latina, AIAN, and other racially and ethnically minoritized women, as well as women in poverty, including forced sterilization and medical experimentation with the first birth control pill on Puerto Rican women (Larson, 2021; NASEM, 2023b; Novak et al., 2018; Pendergrass and Raji, 2017; Stern, 2020; Washington, 2006). It is important to consider the evolution of NIH within this broader context and the effect this may have had on WHR.

Reproductive justice also includes as a central tenet that parents have a right to raise and care for their children in safe and healthy environments (SisterSong, n.d.). This final component focused on safe and healthy birthing and parental rights and has helped expand what it meant to advocate for reproductive justice and not just simply rights to reproductive control (Daniel, 2021). In this way, reproductive justice as a framework indicates that laws and policies that have allowed for forced sterilization of racially and ethnically minoritized women, unethical experimentation with the birth control pill on women, and other policies, such as the Indian Adoption Project, that have taken away parenting rights, fall under the rubric of gendered policies affecting women’s health (Adoption History Project, n.d.; Larson, 2021; Lawrence, 2000; Lopez, 2008; Pendergrass and Raji, 2017; Price and Darity, 2010; Stern, 2005).

The reproductive justice framework can be further expanded to a queer-inclusive lens. It is crucial to acknowledge that many of the issues Black feminists identified in the early 1990s are still prominent in the lives of many cis queer women, trans men, and nonbinary individuals assigned female at birth. An expanded framework is needed to address rights to access alternative insemination, reproductive technologies, gender-affirming care, and rights related to sexual behavior and orientation. Some reproductive justice advocates and scholars assert a fourth tenet—the human right to disassociate sex from reproduction and that healthy sexuality and pleasure are essential to whole and full human life (NASEM, 2021c; Virginia Sexual and Domestic Violence Action Alliance, n.d.; Well Project, 2024; Welleck and Yeung, n.d.).

As a facilitator of health, Medicaid expansion is associated with lower rates of maternal mortality, especially among Black people (Eliason, 2020).

Sexually transmitted infection diagnoses among adolescent SMW are significantly lower in states with lower structural stigma (compared to states with higher structural stigma), and sexual orientation antidiscrimination laws have been linked to lower maternal hypertension among Black and White lesbian and bisexual women (Charlton et al., 2019; Everett and Agénor, 2023). In addition, Earned Income Tax Credit laws are associated with decreased low birthweight, especially among Black people (Komro et al., 2019). These findings underscore how targeted policy interventions can address sexual and reproductive health inequities and the need to research how policy impacts health outcomes.

Rights for SGM

Over the past decade, U.S. legislative and judiciary bodies have set policies that have both affirmed and denied the rights of SGM populations. These legal shifts, and the cultural shifts they represent, are relevant structures that produce needs for health care and manage the contexts in which it is sought. Laws and policies related to gender-affirming care and sexuality rights are the contexts in which women’s health must be navigated. In addition, Supreme Court decisions, such as Obergefell v. Hodges,6 resulting in the federal right to same-sex marriage, and Bostock v. Clayton County,7 affirming that prohibiting sex discrimination in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 19648 protects employees against discrimination based on sexual orientation or transgender status, can affect women’s health by reducing stigma and discrimination and increasing access to insurance and economic stability through spouses and employers (National Constitution Center, n.d.; U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, n.d.). Similarly, the Affordable Care Act Section 1557 names sexual orientation and gender identity as protected in public health insurance coverage (HHS, 2024).

Numerous laws and policies at the federal and state level affect TNB individuals’ health, well-being, and health care quality and access. These include laws and policies that impede or protect TNB people’s ability to participate in sports, use restrooms, update identification documents in accordance with their gender identity, access health care, particularly gender-affirming care, or maintain protection from discrimination in housing or other domains (Hohne, 2023; Movement Advancement Project, n.d.-a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h). Recent years have seen an increase in proposed state legislation aimed at limiting their rights, with over 560 such bills under consideration in 2023 (Hohne, 2023). Numerous bills have banned gender-affirming care for transgender

___________________

6 Obergefell v. Hodges, No. 14–556, 576 U.S. (2015).

7 Bostock v. Clayton County, No. 17–1618, 590 U.S. (2020).

8 Public Law 88-352, 78 Stat. 241 (July 2, 1964).

youth, including banning medication and/or surgical care and sometimes making it a crime for clinicians to provide these (Movement Advancement Project, n.d.-a). Although these legislative efforts primarily restrict care for TNB youth, some state bills are restricting or attempting to restrict gender-affirming care for adults as well (Goldman, 2024). In 10 states, Medicaid policy explicitly excludes coverage of gender-affirming care for individuals of all ages (Movement Advancement Project, n.d.-g).

Conversely, some state laws protect access to health care for TNB people; 14 states and the District of Columbia (DC) have “shield” laws that aim to protect transgender individuals, their families, and medical providers traveling from a state where gender-affirming care is banned to provide or receive it (Movement Advancement Project, n.d.-h). Laws in 24 states and DC prohibit insurers from refusing to cover such care (Movement Advancement Project, n.d.-c). Other protective policies include the prohibition of health insurance discrimination based on gender identity and Medicaid policies that explicitly cover gender-affirming care (Movement Advancement Project, n.d.-c,g).

Summary of Structural Determinants of Health

Structures such as sexism, racism, colonialism, discrimination against SGM individuals, and laws and policies related to reproductive justice and SGM rights have important implications for women’s health. Although many of these themes have traditionally been outside the scope of NIH’s work, NIH is increasingly emphasizing the importance of this knowledge, particularly by creating the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. To advance health for all women, it is critical to understand how outcomes are affected by sex and gender and the range of additional identities and larger structural and policy contexts that shape women’s experiences.

SDOH

Health Care Quality and Access

In Chapter 1, the committee introduced Heise and colleagues’ (2019) framework on the gender system and health (see Figure 1-3), which reflects considerations that guided the committee. It also illustrates how health inequities and outcomes result from gendered pathways to health, including gendered impacts on care access and gender-biased health systems and health research, institutions, and data collection. Access to and use of the health care system, including insurance coverage and ability to pay, is gendered (Bertakis et al., 2000; KFF, 2023b; Lopes et al., 2024). Reports of negative experiences during health care encounters and with clinicians also

vary by gender (Long et al., 2023). The knowledge with which clinicians and researchers operate to promote health and prevent and treat disease for women is also affected by the gendered health system (Mirin, 2021). Chapter 2 also discusses intersecting barriers to health care with differential effects on women.

Because of the lack of research on women’s health and female physiology commensurate with that of men, it is not possible for clinicians to provide evidence-based care for women to the same degree. This problem exists across many diseases for which diagnoses and treatments have been fitted to the presentation and disease course in men, ranging from autism to many aspects of CVD, including aortic stenosis (D’Mello et al., 2022; Merone et al., 2022; Tribouilloy et al., 2021; Wenger et al., 2022). The deficit is more stark in diseases and conditions specific to women, which continue to receive comparatively little funding (Mirin, 2021) (see Chapter 4). Thus, the evidence base for diagnosis in women is limited at best. Similarly, more studies are needed on physical health disparities, chronic conditions, and access to preventive care for TNB people to ensure clinicians have the evidence for effective treatment and intervention. Failure to invest in women’s health and sex differences research results in constrained choices for both women and clinicians, suboptimal care, and increased disease burden. Furthermore, studies indicate that the gaps in the knowledge base create an opportunity for high-impact science through funding of research on women’s health (Baird et al., 2021a,b,c, 2022).

Despite the more limited evidence base for women’s health care, women are more likely to use health care services than men and also play a central role in navigating health care services for themselves and their families (Bertakis et al., 2000; KFF, 2022b). This role of family caregiving and increased connectedness with the health care system may be an important facilitating factor for better health outcomes. While women are less likely to lack insurance coverage than men, they are more likely to have Medicaid (KFF, 2023b). Health insurance coverage is not the only indicator of health care access or quality of care. Access is also shaped by availability of care, timely appointments, geographic accessibility, affordable transportation, and health literacy to understand and carry out treatment plans (AHRQ, 2021; Cyr et al., 2019; Levy and Janke, 2016; NASEM, 2023b). The burden of health care costs is disproportionately felt by women, who spend over 18 percent more per year in out-of-pocket medical expenses than men, excluding pregnancy-related care, and more frequently delay medical care because of cost considerations (Deloitte, n.d.; Saad, 2023). Women are also more likely than men to report cost-related barriers to care, trouble paying deductibles, and medical debt (Lopes et al., 2024).

A higher share of women than men report negative experiences with a health care provider, at 38 and 32 percent, respectively (Long et al., 2023).

Among reports from women ages 18–64 who had seen a provider within the past 2 years, 29 percent had their concerns dismissed, 15 percent had a provider not believe them, and 13 percent had their doctor blame them for a health problem. Reports of negative experiences were higher among women who were low income, living with a disability or chronic condition, Black or Hispanic, and covered by Medicaid or uninsured (Long et al., 2023). Mistreatment during childbirth is common, particularly for racially and ethnically minoritized individuals, and may include loss of autonomy and being shouted at, ignored, or refused care (Vedam et al., 2019). Data illustrate significant racial inequities in maternal outcomes, often rooted in discrimination and clinician bias (Fernandez et al., 2024; Gunja et al., 2024; Tucker et al., 2007). For example, research shows that Black birthing people receive worse-quality care than White birthing people, including in measures of care process, outcomes, and perceptions (Gunja et al., 2024). In a 2023 study, 20 percent of those surveyed reported experiences of mistreatment during maternity care, with 30 percent of Black, 29 percent of Hispanic, and 27 percent of multiracial birthing people reporting mistreatment (Mohamoud et al., 2023). The most common types were receiving no response to requests for help, being shouted at or scolded, not having their physical privacy protected, being threatened with withholding treatment, and being made to accept unwanted treatment (Mohamoud et al., 2023).

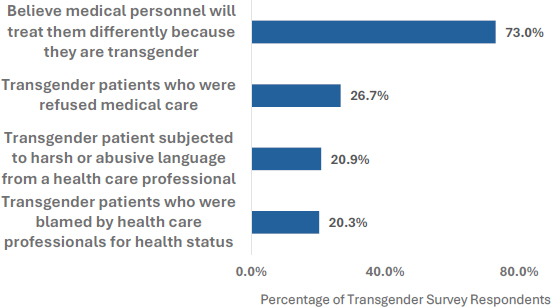

How sexual orientation and gender identity affect access to care is also a critical consideration. For example, transgender people and cisgender bisexual women are almost twice as likely to report an unmet need for mental health care compared to cisgender heterosexual women (Steele et al., 2017). In addition, as discussed, laws and policies governing health care access for transgender individuals vary across the country, leaving them particularly vulnerable to lack of access to care and inequitable care. Discrimination is also a factor. Based on survey data from Lambda Legal (2010), about 70 percent of transgender and gender-nonconforming people report that they experienced one or more types of discriminatory acts in the health care setting: 26.7 percent were refused care, 20.9 percent were subjected to harsh or abusive language, and 20.3 percent were blamed for their health status (Figure 6-3). In addition, 73.0 percent reported that they believe medical personnel will treat them differently because they are transgender. These realities drive transgender people to delay or avoid care. Citing health care discrimination, more than 25 percent reported delaying or avoiding care when sick or injured, and 33 percent reported delaying preventive care. This can result in poorer health outcomes and increase the possibility of especially serious health consequences, such as late-stage cancer diagnoses, and complications of chronic conditions, such as heart disease and diabetes (Movement Advancement Project and Center for American Progress, 2024).

SOURCE: Data from Lambda Legal, 2010. Adapted from Movement Advancement Project and Center for American Progress, 2024.

Data Gaps

While there are many data gaps related to social determinants for women’s health in the health care realm, data gaps in pregnancy-related spheres are one striking example. A lack of robust measurements that help investigators tie community and structural drivers to pregnancy outcomes stymies advancement in understanding the upstream forces responsible for health outcomes inequities. For example, data and measures to capture domains of structural racism remain in their infancy (Headen et al., 2022). Novel approaches that combine qualitative or narrative data, geographic information systems technologies, machine learning, and social “big data” could help to fill data gaps surrounding environmental exposures, neighborhood conditions, and political and social capital that impact pregnancy and abortion outcomes. Understanding upstream social and community factors and their relationship to biological, genetic, and epigenetic processes can provide leverage points for intervention and policy change that could close gaps in pregnancy outcomes by race, ethnicity, income, or geography.

Economic Stability and Employment

Income and Poverty

Women in the United States experience persistent economic inequities that are further exacerbated among racially and ethnically minorized and SGM women (Badgett et al., 2019; Kochhar, 2023; Walker et al., 2021). Sex and gender bias result in systemic differences that leave women overrepresented in certain occupations compared to men, such as caregiving

and low-paid administrative positions (Frank et al., 2023). Poverty is more prevalent among women compared to men across all age groups (Shrider et al., 2023). Despite an overall trend toward narrowing the gender pay gap, White women still earn 83 percent of what their male counterparts do, while Asian, Black, and Hispanic women earn 93, 70, and 65 percent, respectively, of what White men do (Kochhar, 2023). Mothers and parents experience economic disparities most acutely, and 26.8 percent of female head-of-household families live in poverty (Creamer and Mohanty, 2019). Nationally, in 2021, working mothers of children under 18 earned 61.7 cents for every dollar made by working fathers (Institute for Women’s Policy Research, 2023).

Poverty rates also vary by sexual orientation and gender identity. Rates are higher among cisgender bisexual women and transgender individuals, at 29.4 percent each, than cisgender straight or lesbian women, at 17.8 and 17.9 percent, respectively (Badgett et al., 2019). As discussed, Bostock v. Clayton County affirmed that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects transgender people from employment discrimination (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, n.d.). However, it only applies to employers with 15 or more employees. Laws in just 24 states, three territories, and DC provide additional protections, leaving transgender people especially at risk of being unfairly denied employment or forced out of jobs by harassment, mistreatment, or discrimination (Movement Advancement Project, n.d.-b; Movement Advancement Project and Center for American Progress, 2024).

A clear association exists between the effect of poverty on health arising from lack of insurance or access to care. However, poverty also affects physical and mental health through other mechanisms. For example, it can reduce access to other conditions that enable good health, including safe neighborhoods and housing and healthy food (OASH, n.d.-c). These gendered pathways link socioeconomic status and health across the life course, including for conditions such as chronic pain, depression, and cardiometabolic diseases (NASEM, 2024a).

Individuals’ experiences with the criminal-legal system can also affect their economic standing. For example, incarceration is associated with a 52 percent reduction in annual earnings and with employment in low-paying jobs, which affects earnings growth for life (Craigie et al., 2020; NASEM, 2023b). Women face distinct economic challenges during and after incarceration, including specific financial issues that affect their success during reentry; for example, low and stagnant wages are a major financial barrier (Callahan et al., 2016). These data have particularly important implications for transgender individuals, who are overrepresented among incarcerated individuals because of vulnerabilities, such as family rejection and homelessness, unfair school disciplinary policies, and employment and

housing discrimination, and laws and policies such as the criminalization of sex work, drug laws, police profiling, and inaccurate/misgendering identity documents (Center for American Progress, 2016b).

Employment and the Workplace

Workplace factors, such as employer benefits and sex and age discrimination, also affect health (Goodman et al., 2021; Rochon et al., 2021). Age discrimination in the workplace is more prominent for women and can have negative consequences, including on recruitment, access to career opportunities, and pensions. Across the life course, inequity in opportunity and policies such as loss of pension contributions during maternity leave have resulted in women receiving 27 percent fewer annual pension payments than men in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries (Rochon et al., 2021).

Access to workforce support and protection, such as paid sick leave, health insurance, other benefits, and minimum wage and overtime laws, is an important consideration for women’s health. Women are more likely than men to stay home to care for sick children and hold part-time jobs, which are less likely to offer paid sick leave (KFF, 2021). According to the Department of Labor, mothers provide an average of $295,000 of unpaid care for children and adults throughout their lifetime, based on the 2021 U.S. dollar value (DOL, 2023). Paid parental leave offers several economic and health benefits, including reducing the risk of poverty, especially among single mothers with lower income and education (Goodman et al., 2021). In addition, a recent analysis of state-level paid sick leave policies in three states found that it reduced the days that women experienced poor physical and mental health (Slopen, 2023).

There are also racial and ethnic inequities in employment benefits and protections, with non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women receiving fewer weeks of paid family leave on average and less access to it through both their employers and government programs in comparison to non-Hispanic White and Asian women (Goodman et al., 2021). Racially and ethnically minoritized women are also overrepresented in some low-wage occupations that lack benefits. For example, they make up approximately two-thirds of home health workers (Yearby, 2022). Historically, laws both segregated these women, especially Black women, into these occupations and excluded them from efforts to improve worker conditions (e.g., the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 [FLSA]9 and the Social Security Act of 193510). Although FLSA and the Social Security Act were amended to include domestic workers

___________________

9 29 U.S.C. §201 et seq.

10 42 U.S.C. §301 et seq.

in 1974 and 1950, respectively, policies allowing home health workers to be labeled as independent contractors excludes many from FLSA protections (Kijakazi et al., 2019; Yearby, 2022).

Scholars and advocates of law reform and policies to improve economic well-being and justice for women have focused on policies such as wage equity, paid family leave, childcare, and social safety net programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and the Earned Income Tax Credit (NASEM, 2019a,b, 2024d). Despite progress, significant financial insecurity remains for many women and families with young children, including lack of support for those who stay home to care for children and a lack of affordable childcare and early childhood education options. In addition, the control of paid family, medical, and sick leave policies at the state and local rather than federal level introduces inequities (Goodman et al., 2021; KFF, 2021; Slopen, 2023). Consideration of factors such as poverty and the workplace in WHR, and how these policies might be improved and expanded, is needed to support the health of working women and their families.

Caregiving

While many workplace family leave policies have improved support for childcare (e.g., childbearing, childrearing), support for informal caregiving and eldercare has lagged. Because many leave policies are structured to require time to be taken consecutively, they do not account for the often acute and unanticipated needs of informal caregiving and eldercare, resulting in lost wages. Informal caregivers provide uncompensated care to ill or disabled family members and friends (Rennels et al., 2024). Women are disproportionately represented, accounting for two of every three caregivers (Sosa and Mangurian, 2023). Based on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, one in four women are caregivers compared to one in five men. The data also illustrate the physical and emotional toll of caregiving, with 14.5 and 17.6 percent of caregivers reported experiencing 14 or more mentally or physically unhealthy days in the past 30 days, respectively. In addition, 36.7 percent of caregivers reported getting insufficient sleep, defined as fewer than 7 hours in a 24-hour period (CDC, n.d.-c).

Caregiving also has unique effects on racially and ethnically minoritized women. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that one-third of AIAN adults are caregivers, and 60 percent of them are women (CDC, n.d.-b). Data from the American Association of Retired Persons shows that non-White caregivers (both men and women) provide more hours of care each week than White caregivers and experience a higher

burden of high-intensity care (AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020). For example, Black and Hispanic cancer caregivers (both men and women) spend more time, take on more tasks, and face greater financial burdens compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts. However, they report similar or lower levels of social, emotional, and health-related burdens. Differences in social support and caregiving preparedness between racial groups partially account for the inequities in burden. To address these inequities, research and policy need to focus on alleviating the financial strain experienced by Black and Hispanic caregivers and on the lack of support services (Fenton et al., 2022).

Nurses and other health care providers often take on unpaid caregiving for family members, resulting in negative health consequences, such as shorter sleep duration and poorer sleep quality (DePasquale et al., 2019). Women working in nursing homes also experience higher perceived stress, poorer psychological well-being, and more family–work conflict than those without additional unpaid caregiving responsibilities, whether for children or elders (DePasquale et al., 2016). For conditions with a high caregiving burden, such as dementia, women reduce their work hours or tend to leave the workforce altogether because of the time required, reducing the gross domestic product (Kubendran et al., 2016). Lack of policies to support informal caregiving and eldercare also negatively affects the physician workforce caring for and conducting research on women’s health (see Chapter 8).

Social and Community Context

The social and community context influences women’s health in a number of ways. For example, strong social networks provide emotional support and practical help, such as childcare or transportation, which can alleviate stress and improve health outcomes. Women with robust social ties often experience better mental health and can better manage chronic conditions (NASEM, 2024a).

Safe neighborhoods with supportive community structures contribute to overall well-being. Civic engagement and active participation in community activities and organizations can enhance a sense of belonging and social support, leading to better mental health and overall well-being (NASEM, 2023a,b; Rippel Foundation, n.d.). Social norms and expectations regarding gender roles can affect women’s health by influencing access to health care, autonomy, and opportunities for education and employment. Conversely, norms that restrict women’s choices or access to resources can contribute to poorer health outcomes. Another crucial aspect of the social and community context is violence, which profoundly affects women’s health and is explored next.

Violence Against Women

Violence against women is common worldwide, with over 35 percent of women reporting experiences of domestic violence, abuse, and intimate and non-intimate partner sexual violence. Women experiencing violence are three-, four-, and seven-fold more likely to suffer from depression, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder, respectively (Oram et al., 2017).

Violence and abuse that starts in childhood can have lifelong, negative effects on a woman’s health. Advancing Research on Chronic Conditions in Women describes how early experiences of trauma, also called adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) or early life adversity and which encompass verbal, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, lead to physiological changes that affect the development of chronic conditions in women (NASEM, 2024a). Research has described associations between such traumatic experiences and seemingly disparate conditions such as endometriosis, vulvodynia, and fibroids, which are female specific, and depression, chronic pain, heart disease, stroke, and autoimmune disease, which occur predominantly or differently in women (Felitti et al., 1998; NASEM, 2024a). Research has identified sex and gender differences in the frequency and type of trauma experienced, with women experiencing more ACEs than men (Haahr-Pedersen et al., 2020). Other studies have reported higher prevalence of ACEs in women compared to men (Haahr-Pedersen et al., 2020; Hurley et al., 2022). Further research is needed to understand precisely how trauma alters women’s mental and physical health across the life course, how gender-related social factors make women vulnerable to trauma, and how to mitigate trauma risks and the later detrimental health consequences in women (NASEM, 2024c).

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is the leading cause of injury among women and is associated with physical injuries (NASEM, 2024b). Furthermore, IPV is associated with adverse outcomes in sexual and reproductive health (including gynecologic infections, HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections, and unintended pregnancies) and mental health (such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, substance misuse, suicidality, and eating disorders). Essential health care services for IPV can include universal screening paired with education, enduring safety planning centered on women’s needs, and referrals to care and support services (NASEM, 2024b).

Violence against women and Two-Spirit individuals is of large concern among AIAN people. Homicide is the seventh leading cause of death among AIAN females aged 1–54 (Petrosky et al., 2021). Native women are also 2.5 times more likely to be raped than non-Native women (Urban Indian Health Institute, n.d.). A 2011 study by the National Gay & Lesbian Task Force found that 45 percent of Two-Spirit people reported

family violence, 55 percent were harassed by shelter staff while at a shelter, and 22 percent were sexually assaulted by shelter residents or staff (Tribal Information Exchange, n.d.). Moreover, violence against AIAN women and Two-Spirit individuals is often underreported, given the lack of trust in law enforcement and jurisdictional complexities. The interplay between tribal, federal, and state jurisdictions can complicate legal responses and justice.

Transgender individuals also face high rates of violence victimization, including IPV and bias-motivated murder and violence, which has important implications for their health and well-being (Coston, 2023). Data from the 2017 and 2018 National Crime Victimization Survey demonstrate that transgender people experience nearly four times more violence than cisgender people at 86.2 victimizations per 1,000 persons compared to 21.7, and households with a transgender person have higher rates of property victimization than cisgender households at 214.1 per 1,000 households versus 108 (Flores et al., 2021). Of reported hate violence in 2017, 17 percent involved anti-transgender bias. Of 52 reports of hate violence homicides in 2017, 52 percent were against transgender or gender-nonconforming people (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, 2018). Furthermore, a 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis found that transgender individuals were 2.2 and 2.5 times more likely to experience physical and sexual IPV, respectively (Peitzmeier et al., 2020). Factors such as social isolation and economic vulnerability can leave them dependent on abusive partners. The National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs found that 33 percent of violence reported as IPV, rather than as bias motivated, involved anti-transgender bias (Coston, 2023; National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, 2018). It is also common for transgender individuals to experience discrimination when seeking assistance from domestic violence shelters, police, or health care providers (Center for American Progress, 2016a; Peitzmeier et al., 2020).

Women with a disability are more likely to experience IPV, including sexual and physical violence, stalking, psychological aggression, and control of reproductive or sexual health, compared to women without a disability (CDC, 2023b). Disabilities can lead to social isolation, limiting women’s access to supportive networks or resources. This isolation can make it harder for them to seek help or escape abusive situations (Anyango et al., 2023).

Violence against women profoundly affects their health outcomes, leading to both immediate and long-term consequences. The resulting physical injuries and psychological trauma contribute to a range of health issues, including chronic pain, mental health disorders, and increased susceptibility to other illnesses (Uvelli et al., 2023; Wuest et al., 2009, 2010). Systemic barriers, such as limited access to health care, stigma, and discrimination, exacerbate the effects. Addressing these challenges requires a comprehensive

approach that includes improving access to support services, enhancing legal protections, and addressing the broader SDOH that contribute to the vulnerability of affected individuals (Arcaya et al., 2024; Gehris et al., 2023; Robinette et al., 2021).

Neighborhood and Built Environment

The neighborhood and built environment significantly affect women’s health outcomes through a variety of mechanisms, encompassing both physical and social aspects (OASH, n.d.-d). For example, neighborhoods with closer proximity to health care services have improved access to preventive care, screenings, and treatment and more specialized services, such as maternal care, mental health support, or reproductive health services, and this can greatly affect women’s health (OASH, n.d.-b). In general, people in unsafe neighborhoods may experience higher levels of anxiety and stress, and the perception of safety may affect women’s willingness to engage in physical activity, seek health care, or use community resources (Gehris et al., 2023; Robinette et al., 2021). Environmental exposures and geography are additional factors with critical impacts on women’s health and will be further explored in the following sections.

Geography

Geographic location can have critical impacts on women’s health. For example, as discussed, laws and policies that affect TNB people’s health, such as those that impede or protect their ability to participate in sports, use restrooms, update identification documents in accordance with their gender identity, access health care, particularly gender-affirming care, or maintain protection from discrimination in housing or other domains, vary by state (Hohne, 2023; Movement Advancement Project, n.d.-a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h). Other examples include the effects of state-level structural sexism and variability in the expansion of Medicaid and access to abortion services on women’s health (Homan, 2019; KFF, 2023a; Margerison et al., 2020) (see Chapter 7 for more information).

In considering the impact of geography on women’s health, rurality in particular is an important factor. For rural residents, high poverty and lack of opportunity can create challenges to staying healthy, causing difficulty accessing housing, education, jobs, health care, transportation, and healthy food. Low physician density and the small scale, limited staff, and limited resources of health systems pose challenges to the management of chronic conditions, access to timely care, and access to subspecialists. Furthermore, transportation challenges can create difficulties accessing even this limited available health care (NASEM, 2017, 2021b). Data suggest that fewer rural

residents participate in clinical trials than urban residents, and they travel further to do so (Bharucha et al., 2021).

Rural women experience significant inequities compared to urban women, including higher rates of fair or poor self-reported health, unintentional injury and motor vehicle–related deaths, cerebrovascular disease deaths, suicide, cigarette smoking, obesity, difficulty with basic actions or limitation of complex activities, and incidence of cervical cancer. Additionally, fewer rural women receive recommended preventive screenings for breast and cervical cancer (ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, 2014). In addressing gaps in women’s health, it is critical to consider these and other ways they are affected by place.

Environmental Factors and Women’s Health

Women may be at increased risk for some diseases associated with environmental exposures because of biological or behavioral differences. Health conditions such as endometriosis and uterine fibroids, reproductive health outcomes, female-specific cancers, and autoimmune diseases all have links to environmental causes (Corbett et al., 2022; Giudice, 2021; Haggerty et al., 2021; Hassan et al., 2024; Katz et al., 2016; Mallozzi et al., 2017; McCue and DeNicola, 2019; Rickard et al., 2022; Rudel et al., 2014; Stiel et al., 2016; Vallée et al., 2024; Van Loveren et al., 2001; Zlatnik, 2016).

Physiological differences between women and men significantly affect exposure, uptake, metabolism, and retention of toxic chemicals. Women’s higher body fat content facilitates the accumulation of lipophilic chemicals, which can be released during weight fluctuations or lactation. Gender-specific metabolic pathways and enzyme activity differences can result in varying internal doses and toxic chemical responses (Silbergeld and Flaws, 2002). In addition, hormonal variations influence metabolic pathways and bone physiology, altering chemical processing and storage. For example, women’s reproductive stages affect enzyme activity and bone mineral metabolism, influencing the body’s interaction with toxic substances, such as lead and mercury. These factors underscore the crucial importance of gender-specific considerations in toxicology research and risk assessment, a complexity that is often overlooked (Silbergeld and Flaws, 2002).

As a result of socioeconomic factors and traditional gender roles, women experience environmental health risks disproportionately and uniquely (Moss, 2002). For example, exposure to air pollution increases the risk of adverse outcomes in pregnancy, such as preterm birth, low birthweight, and stillbirth. Moreover, data illustrate that racially and ethnically minoritized individuals are exposed to disproportionately high levels of air pollution, including Hispanic, African American, and Asian/Pacific Islander mothers, with more adverse pregnancy outcomes related to such

exposure among Black and Hispanic people than Non-Hispanic White people (Dzekem et al., 2024). Additionally, while Black people are overall 40 percent more likely to have asthma than White people, Black women are 84 percent more likely to have asthma than Black men (NHLBI, 2023).

Additionally, spending more time at home can increase women’s exposure to contaminants in drinking water (Silbergeld and Flaws, 2002). Despite evolving gender roles, women are still more likely to be primary caregivers and homemakers, placing them at risk of exposure to indoor pollutants from various sources, including household products, building materials, and outdoor air infiltration (Folletti et al., 2017; Rousseau et al., 2022). Cooking can increase exposure to particulate matter and gases (Kashtan et al., 2024). Hobbies such as arts and crafts can also increase women’s exposure to metals in paints or jewelry-making materials (Silbergeld and Flaws, 2002).

Beauty and personal care products are known sources of potential exposure to toxic chemicals, and understanding the exposure pathway and disease risks requires further elucidation. For example, a study found toxic chemicals, such as lead and arsenic, in tampons, though some researchers have stated that these cannot leach out during use (Shearston et al., 2024). Phthalates and talc in vaginal douches and other feminine care products are associated with gynecological cancers (Zota and Shamasunder, 2017). Others have also documented the potentially carcinogenic effects of cosmetics, highlighting the need for additional research, particularly per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in cosmetics (Balwierz et al., 2023; FDA, n.d.).

Products marketed to women for beauty, feminine hygiene, or other aspects of personal care may also contribute to racial and ethnic health disparities. Colorism, hair texture preferences, and odor discrimination can increase toxicant exposure (Zota and Shamasunder, 2017). For example, mercury in skin-lightening creams is associated with poisoning, neurotoxicity, and kidney damage. Parabens, a common ingredient in hair relaxers, are associated with precocious puberty and fibroids. Chemicals in hair relaxers marketed to Black women appear to be associated with both harmful exposures and disease risks (Zota and Shamasunder, 2017). One study that measured chemicals in hair products marketed to Black women found that root stimulators, hair lotions, and relaxers frequently contained nonylphenols and parabens, which were not always listed on the product label (Helm et al., 2018). Studies have shown a correlation between frequent and long-term use of these products and an increased risk of uterine cancer, an increased risk of breast cancer with lye-based relaxers, and increased risk of earlier menarche (Chang et al., 2022; Coogan et al., 2021; James-Todd et al., 2011; Wise et al., 2023).

Occupational hazards experienced by women include repetitive stress, exposure to violence, and exposure to solvents used in cleaning and

sterilization. Women may be at increased risk for workplace-related musculoskeletal disorders such as sprains, strains, carpal tunnel syndrome, and tendonitis (CDC, n.d.-e). In addition, in 2020, 73 percent of victims who experienced trauma from nonfatal workplace violence were women (CDC, n.d.-a). Some occupational exposures linked to jobs with a higher percentage of women are also associated with cancers that are female specific or more common in women. For example, hospital workers who sterilize medical equipment may be exposed to ethylene oxide, which is associated with breast cancer. Perchloroethylene, the main solvent in dry cleaning, may increase cervical cancer risk (CDC, n.d.-e). Women may also be less protected when they participate in traditionally male-dominated fields because of ill-fitting personal protective equipment and can face additional stressors, such as sexual harassment (CDC, n.d.-e).

Despite growing evidence linking environmental exposures to women’s health issues, significant gaps remain in understanding these complex relationships. While epidemiological studies suggest associations between environmental exposures and various health conditions in women, more research is needed to establish causal links. Multiple factors are associated with most outcomes, and the timing of the exposure, intensity, and duration also contribute. A deeper understanding of how environmental exposures at different life stages (prenatal, puberty, pregnancy, menopause transition) affect women’s health across the life-span is needed. This includes investigating potential long-term consequences of exposures during critical developmental windows. Research also needs to explore how interactions between chemicals and pollutants influence women’s health outcomes; NIH could fund this type of research.

Gaps also exist concerning the specific vulnerabilities faced by racially and ethnically minoritized, low-income, and immigrant women. These groups may experience heightened risks arising from factors such as residential segregation near pollution sources, limited access to health care, and cultural practices that increase exposure (NASEM, 2023b).

Developing and promoting safer alternatives to potentially harmful chemicals in consumer products, building materials, and personal care items is crucial to reduce women’s exposure risks. Although many are marketed as safer or greening cleaning products, few studies have confirmed that they effectively reduce exposure to toxic chemicals (Sieck et al., 2024).

Education Access and Quality

Education, as an SDOH, has an effect on health in a number of ways, including improving health literacy, access to health care, economic stability, and health behaviors. Education can drive opportunity and reproduce inequality (Zajacova and Lawrence, 2018). For example, individuals with

higher education levels generally have greater health literacy, leading to a better understanding of health information and more informed medical choices (Coughlin et al., 2020; NASEM, 2021a). Higher levels of education often correlate with increased use of preventive health services, such as screenings and vaccinations, which can lead to earlier detection and better management of conditions, better employment opportunities, and access to health insurance, improving overall health outcomes (NASEM, 2017). Conversely, poor health not only results from lower educational attainment but also can cause educational setbacks and diminished success because of recurrent absences and difficulty concentrating in class.

Associations between education and health and survival are well documented, but whether their strength depends on gender is not, with few studies on U.S. populations (Montez and Cheng, 2022; NASEM, 2017, 2019b; Raghupathi and Raghupathi, 2020). A study found that effects of education on perceived health and survival vary by gender but in contrasting ways: it significantly improves women’s self-rated health more than men’s, yet it has a greater effect on reducing men’s mortality rates (Ross et al., 2012). Some studies have pointed to important health outcomes correlated with education for women. Globally, women with higher levels of education are more likely to have better mental and physical health, including lower rates of anxiety and depression (Kondirolli and Sunder, 2022). Studies have found that enhancing women’s education leads to a decrease in their short- and long-term likelihood of psychological, physical, and sexual violence. It also reduced their chances of encountering any form of IPV and multiple forms of victimization (Villardón-Gallego et al., 2023; Weitzman, 2018).

In the United States, women are more likely than men to hold a bachelor’s degree or higher. In 2022, 39 percent of women aged 25 and older had a bachelor’s degree, compared to 36.2 percent of men in the same age group. Women also have a higher graduation rate from 4-year institutions, with 66.4 percent graduating within 4–6 years between 2015 and 2021, compared to 60.4 percent of men (WIA Report, 2022). Nevertheless, men continue to have an edge in certain professional fields, such as law, medicine, and dentistry (Nguyen Le et al., 2017). In 2022, men earned 1,869,000 professional degrees, while women earned 1,584,000 (Census Bureau, 2023). In addition, women with bachelor’s degrees in social science or business earn over $1 million less than their male counterparts over their lifetimes. This gap widens to $1.6 million for business majors with graduate degrees and exceeds $1 million for women in law and public policy with advanced degrees (Carnevale et al., 2018).

Research is required to elucidate the specific pathways and mechanisms through which education influences women’s health outcomes, including how it interacts with other SDOH and demographic factors, such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geography.

Health Behaviors and SDOH