A New Vision for Women's Health Research: Transformative Change at the National Institutes of Health (2025)

Chapter: 9 Road Map to Prioritizing Women's Health Research

9

Road Map to Prioritizing Women’s Health Research

The vitality of women’s health research (WHR) requires continuing efforts to build the cadre of talented WHR investigators, consistent investments in WHR to establish a strong scientific foundation, and effective oversight to ensure that research priorities are implemented and met. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) asked the committee to provide recommendations to improve NIH structure, systems, and review processes to optimize WHR; training and education efforts to build, support, and maintain a robust WHR workforce (i.e., those who undertake such research, not only women researchers); and the appropriate level of funding to address WHR gaps at NIH. The committee reviewed why WHR is needed (Chapter 2); the structure, policies, and programs related to women’s health at NIH (Chapter 3); the level and distribution of funding for WHR at NIH (Chapter 4); biological (Chapter 5) and social (Chapter 6) factors that contribute to women’s health in the United States; research gaps among diseases and conditions that are female specific, are more common among women, or affect women differently (Chapter 7); and NIH WHR workforce programs and support (Chapter 8). Based on its review, the committee concluded the approach at NIH is not meeting the scientific workforce’s and, ultimately, the public’s need for WHR.

Conclusion 1: A comprehensive approach is needed to develop a robust women’s health research (WHR) agenda and establish a supportive infrastructure at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Augmented funding for WHR, while crucial, needs to be complemented by enhanced accountability, rigorous oversight, prioritization, and seamless

integration of women’s health research across NIH Institutes, Centers, and Offices. This multifaceted approach is essential to fully capitalize on both existing and future funding and resources.

Conclusion 2: Overall, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is underspending on research to support women’s health, leading to significant scientific and clinical spending gaps on female-specific conditions and women’s health conditions that do not fall within the primary expertise of existing NIH Institutes and Centers. The past 10 years’ funding on women’s health research have been flat and decreased as a share of overall NIH funding.

RECOMMENDATIONS OVERVIEW

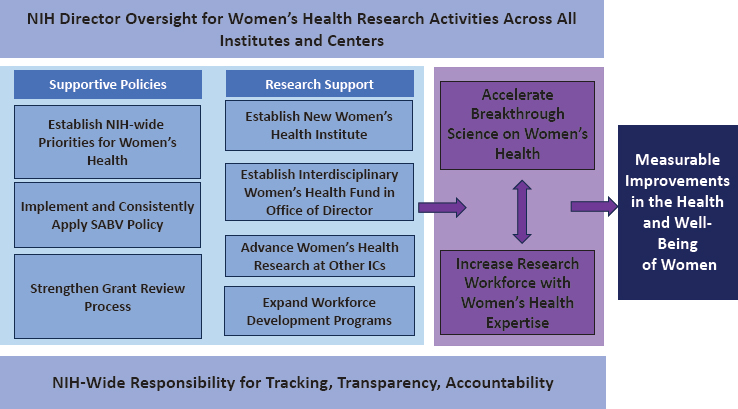

In response to the sponsor’s request to identify improvements to NIH structure, policies, and programs to advance WHR, the committee conducted a thorough and deliberate review of the investments and NIH structure to support WHR and recommends an integrated organizational approach to address the persistent gaps (see Recommendations 1–8). Figure 9-1 provides a high-level overview of key elements of the committee’s recommendations.

The committee recommends that NIH build on and strengthen institution-wide policies that support advances in WHR. Accountability, priority setting, and oversight of women’s health starts at the top of NIH with the Office of the Director (OD) but also sits squarely on the Institutes and

NOTE: ICs = Institutes and Centers; SABV = sex as a biological variable.

Centers (ICs). Without their engagement and commitment, progress will continue to lag. Needed crosscutting supportive policies include a data-driven and stakeholder-informed NIH-wide priority setting process that starts with the OD but also engages all ICs and Offices (ICOs), building on and expanding policies that support producing high-quality, impactful WHR, such as consistently implementing an enhanced sex as a biological variable (SABV) policy, and a more robust and informed grant review process that intentionally includes women’s health expertise.

Creating a new WHR Institute is needed to support and build the body of research on female-specific conditions, as is creating a new interdisciplinary WHR fund, continued and increased contributions by the existing ICs, and a significant expansion in WHR training programs to support the workforce to build on the knowledge base. An infusion of new funds to conduct this research and train the workforce needs to accompany these changes, ultimately leading to major breakthroughs that would improve the health and well-being of U.S. women.

The committee identified five steps Congress and NIH should take to advance WHR:

- Create pathways to facilitate and support innovative and transformative research for women’s health;

- Strengthen oversight, prioritization, and coordination for women’s health research across NIH;

- Expand, train, support, and retain the women’s health research workforce;

- Optimize NIH programs and policies to support women’s health research; and

- Increase NIH investment in women’s health research.

The committee notes the tension between the support needed to build women’s health and common needs for other areas of study. However, WHR represents an acute problem that requires immediate attention to address a long-standing gap and make needed breakthroughs. In addition, several of the committee’s recommendations could be expanded to strengthen other areas of study (e.g., recommendations on tracking NIH investments, priority setting, and retention of the workforce).

CREATE PATHWAYS TO FACILITATE AND SUPPORT INNOVATIVE AND TRANSFORMATIVE WHR

NIH Organizational Structure

NIH’s structure results from “a set of complex evolving social and political negotiations among a variety of constituencies, including Congress,

the administration, the scientific community, the health advocacy community, and others interested in research, research training, and public policy related to health” (IOM and NRC, 2003, p.26). The evolution of NIH to the institution it is today is not the result of an intentional approach but rather an organic process responding to developments in knowledge, national health needs, and advocacy. NIH’s structure does not adequately integrate or support women’s health researchers or WHR and greatly limits its ability to ensure women’s health is comprehensively addressed.

There is a lack of accountability within NIH to address women’s health, and major constraints on the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) hinder its ability to incentivize and persuade ICs to fund more priority women’s health and sex differences research. In addition, many women’s health conditions and women-specific life stages, such as gynecological issues other than cancer related and menopause, do not align with the priorities of the ICs. In its analysis, the committee found that WHR only accounted for 8.8 percent of NIH research spending from 2013 to 2023. This low rate of proportionate funding has decreased over time, with 9.7 percent of total NIH funding granted in fiscal year (FY) 2013 and 7.9 percent in FY 2023 (see Figure 4-2 in Chapter 4). Funding for several conditions, such as diabetes, pregnancy-related conditions, and perimenopause and menopause, appeared to derive from multiple IC sources. This indicates that these areas of research have not been consistently identified within the purview of any single IC. The relatively scant funding for most conditions relevant to women’s health suggests these areas of research have also lacked a consistent IC source of funding or, sometimes, any IC funding at all (see Chapter 4).

An analysis of the challenges to supporting high-quality and innovative WHR needs to consider the broader structural and social barriers of gender bias and sexism within the United States—these biased systems informed NIH’s founding and initial guiding frameworks focused primarily on cisgender men and their health (see Chapters 2 and 3 for examples of male-centered research as a foundation to NIH). Over the past several decades, NIH has launched major efforts to address these concerns, and despite progress, persistent gaps remain (see Chapter 8). To overcome the barriers described in this report, oversight for WHR is needed at NIH by an entity that can oversee strategic planning and implementation of processes and policies to expand WHR funding and ensure accountability (see Chapter 3 for an overview of the NIH structure and its limitations for WHR).

An option the committee considered is to maintain the NIH structure that designates ORWH as the main responsible entity. However, the committee concluded that the status quo has proven insufficient to address the research gaps and fulfill the NIH goal of fostering “fundamental creative discoveries, innovative research strategies, and their applications as a basis for ultimately protecting and improving health” for the nation (NIH, 2017).

As Chapter 3 described, ORWH is the hub for WHR at NIH. Despite many successes, it is a small, inadequately funded Office without the authority to require ICs to conduct WHR or oversee compliance with the NIH SABV policy. This has left a considerable gap in the attention to and investment in WHR across NIH. Without the ability to hold ICs accountable or power that comes with a large budget to support grants, the structure leaves WHR underfunded and understudied. ORWH lacks the needed authority, visibility, funding, and infrastructure to advance WHR.

Conclusion 3: The current organizational structure of the National Institutes of Health limits its ability to address gaps in women’s health research. There is inadequate oversight to ensure that women’s health is studied comprehensively. There is limited ability for the Office of Research on Women’s Health to incentivize Institutes and Centers (ICs) to prioritize research on women’s health and sex differences. Furthermore, many women’s health conditions and women-specific life stages do not easily align within the purview of the 27 existing ICs despite the millions of women who experience the burdens of these conditions.

The committee considered several structural solutions to improve WHR at NIH. It assessed these solutions for their potential to facilitate the study of female-specific conditions not prioritized by or under the purview of an NIH IC and to advance sex differences research; coordinate and implement NIH-wide strategic planning for WHR across the life-span; oversee strategic development of the WHR workforce; increase funding for WHR; and provide oversight and accountability for policies related to women’s health and identified WHR priorities.

Potential Structural Changes at NIH to Ensure a Robust WHR Agenda

Keep the current organization but significantly increase funding for ORWH

One weakness of ORWH is its limited budget, which is too small to provide grants independently, forcing it to rely on partnering with other ICOs that might be interested in funding a topic that it identifies as a priority. For perspective, the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders is one of the smaller ICs. It supports studies on hearing, taste, smell, and some communication problems. While these are important problems, its budget was $534 million in 2023—7 times that of ORWH 2023 budget ($76 million), which represents almost 51 percent of the U.S. population (Census Bureau, n.d.; Sekar, 2024).

Providing ORWH with significantly more funding would make it easier for it to invest in WHR priorities that the ICs are not fulfilling. However, without a major infusion of funds, it could not build the needed

infrastructure—including staff and physical workspaces—to provide grants without partnering with another IC. It also would not have an intramural research program. The committee recognized that with sufficient funds, ORWH capacity could expand, enabling it to provide additional funds to the ICs for WHR, similar to the model the Office of AIDS Research uses, and increasing the chances that it could work with ICs to fill WHR gaps. However, the ICs will still need to prioritize WHR within their domains, and no mechanism would yet exist by which ORWH could incentivize other ICs and hold them accountable for investing in WHR. With a large funding increase, it could also undertake more strategic planning for workforce development and have more funds to offer ICs to participate in those programs.

A fund for WHR

Another solution the committee considered was to create a central fund for WHR in the OD to support interdisciplinary women’s health and sex differences research with a focus on innovation and accelerating biomedical discoveries. This idea builds on NIH funds and initiatives with similar goals on different topics, such as the Common Fund, Cancer Moonshot, and Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative, discussed later.

The 2006 NIH Reform Act1 created a “common fund,” a funding entity within NIH that supports biomedical and behavioral research programs that the Division of Program Coordination, Planning, and Strategic Initiatives would administer. One of the Common Fund’s criteria for funding is collaboration between multiple ICOs (NIH, 2024a). When the fund was first announced in FY 2004, each IC contributed 1 percent of its budget to it. That first year, the fund’s budget totaled $132 million, or 0.5 percent of NIH’s $27.9 billion budget (Erickson, 2014). With the 2006 NIH Reform Act, the Common Fund was authorized as a line item in the NIH budget, and in FY 2007, $483 million was appropriated, accounting for 1.7 percent of the NIH budget. The act stipulated that the fund could not drop to a lower percentage and anticipated a rise to 5 percent (Collins et al., 2014). This stable funding source allows NIH to develop unique programs that traditional funding mechanisms cannot support.

The Common Fund’s budget has grown steadily since its inception. The FY 2025 budget request is $722.4 million, and it has ranged from $544 million in FY 2010 to its peak of $735 million in FY 2023 (NIH, 2010, 2024b). The fund supports research ranging from basic science to clinical applications, along with the development of new scientific methods and tools. In FY 2023, it reported funding of 23 scientific programs, 544 principal investigators (PIs), including 188 high-risk, high-reward PIs, 102

___________________

1 Public Law 109–482 (January 15, 2007).

of them early-career PIs.2 It had 142 competing research project grants and 23 ICOs coleading programs (NIH, 2024b).

A central fund for WHR could be modeled after the Common Fund. The ICs would compete for funds, presenting novel areas of WHR. If similarly administered at the level of the NIH director, it would have a template, making it easier to implement. It could be staffed by experts in women’s health, thereby growing NIH’s internal expertise. It would encourage coordination and interdisciplinary approaches because it would prioritize applications submitted by ICs working together. Centrally situated, the fund would enable exploring a wide range of WHR topics.

Another example is the Cancer Moonshot, a comprehensive initiative the government launched in 2016 to accelerate progress in cancer research and improve prevention, detection, treatment, and care. The 21st Century Cures Act3 authorized $1.8 billion to it from 2017 to 2023 (NCI, n.d.). The initiative represents a significant national effort to transform cancer research and care, beyond the substantial investment that NIH was already making. The research it generated has improved the understanding of cancer biology and risk factors, contributed to developing new diagnostics and treatments, and enhanced collaboration across the cancer research community (NCI, 2023).

The BRAIN Initiative, a comprehensive research effort aimed at revolutionizing understanding of the human brain, launched in 2013 and invested $680 million in FY 2023 (BRAIN Initiative, 2024a,b; White House, n.d.). Congress funds it from two streams: line items in the budgets of 10 ICs provide a base allocation and funding authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act serves as a supplement (BRAIN Initiative, 2024b). The BRAIN Initiative is a partnership between federal and nonfederal collaborators and has contributed to innovative tools and technologies and new methods for monitoring and manipulating neural activity (BRAIN Initiative, 2023, n.d.). This could also be a model for collaboration with industry to prioritize women’s health and address additional gaps in the field (e.g., joint funding of projects or specific application calls for products specific to women or studies on sex differences in adverse events from medications).

A WHR fund in the OD would also help continue breaking down the research silos that inhibit WHR, incentivizing ICs to prioritize WHR and collaborate to identify the most innovative and pressing needs in a multidisciplinary manner. However, it alone would not address the need for coordination, accountability, oversight, and workforce development identified by the committee or result in a home for female-specific conditions outside

___________________

2 Yearly averages for FY 2019–FY 2023.

3 Public Law 114–255 (December 13, 2016).

the purview of existing ICs. Although some of these mechanisms could be built into fund administration, such as some aspects of coordination, the administering Office would not have the capacity to ensure a robust research agenda for female-specific conditions or oversee the work of ICs.

Create a new WHR institute

One proposed solution the committee considered is to create an institute that focuses on women’s health. This would highlight the prominence of women’s health at NIH, but it is a complicated solution. As discussed in previous chapters, aspects of women’s health are and should be integrated into existing ICs, capitalizing on the expertise of the ICs’ staff and extramural research community. However, the ICs do not comprehensively cover all pressing diseases and conditions that affect women, leaving significant research gaps.

One of the major concerns with creating a women’s health institute is the potential to isolate WHR. However, creating a women’s health institute does not imply that the other ICs are only about men’s health, and it would not need to be chartered with the goal of addressing all of women’s health at NIH. For example, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) would still need to address women’s cancers, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute would still address cardiovascular disease in women, including how the condition and its treatments affect women differently. Therefore, the committee considered a new institute with a narrow mission—with the primary responsibility to lead, conduct, and support research on female physiology and chromosomal differences, reproductive milestones across the life course, and female-specific conditions that do not fall under the purview of other ICs. The institute would support clinical and public health research relevant to women and girls and also harness the relevant expertise of the other ICs, as is now done between existing ICs.

An Institute is subjected to a higher level of oversight, as Congress assesses the work of the ICs, increasing accountability. However, since other ICs would still study women’s health, a high level of coordination would still be required to sustain cross-IC collaboration on WHR if a new institute were created. Thus, this solution alone would not address all the shortcomings in the organizational structure.

A women’s health institute could oversee peer review for studies on women’s health and establish study sections that represent the expertise needed to address women’s health and sex differences research, which other ICs could also use. It would house deep expertise in such research in its staff, something ORWH cannot do because it is a small Office, such that it would be a resource to all of NIH. It would also provide a “home” and grants for conditions specific to women that are not prioritized by other ICs, such as endometriosis, fibroids, pelvic floor disorders, polycystic ovary

syndrome, and vulvodynia, while also developing and funding the next generation of researchers. As Chapter 8 discussed, growing WHR requires a robust workforce, and WHR might appeal more to early-career investigators if they know a stable institute exists where they can apply for grants, another positive aspect of creating the institute.

ICs that oversee research receive more funding than NIH Offices because they are expected to fund intramural and extramural research to fulfill their mission. However, they have a range of funding levels, with NCI receiving $7.3 billion in FY 2023 and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine receiving $170 million (NIH, 2023a,b). Congress would need to fund an institute on WHR at a level commensurate with its task—that is, conducting and funding research and serving as a reservoir of experts on WHR, a resource for peer review, and a collaborator with other ICs.

One important barrier to creating a new institute is that NIH authorizing legislation, the NIH Reform Act states:4 “In the National Institutes of Health, the number of national research institutes and national centers may not exceed a total of 27, including any such Institutes or Centers established under authority of paragraph (2) or under authority of this title as in effect on the day before the date of the act enactment of the National Institutes of Health Reform Act of 2006.” The secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) would need to eliminate one IC or merge one with another, or congressional action would be needed to expand the number of ICs allowable.5

The committee considered the consequences of restraining biomedical science to a prespecified organizational structure. Medical and surgical subspecialties continue to evolve as clinical practice changes based on new evidence. Modern approaches to managing most chronic illnesses involve collaborations that were uncommon just a few decades ago. As Chapter 3 discussed, NIH has made changes as research has advanced and new health priorities have evolved. For example, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) was first an Office and then a Center before becoming an Institute (NIMHD, 2024a). It is worth asking how often highly competitive, forward-looking organizations are locked into a permanently fixed organizational structure. Even within NIH, ICOs regularly evaluate their internal structure in relation to evolving strategic objectives. Typically, appointing a new IC director triggers a new strategic plan that often involves internal reorganization.

Since the last NIH reorganization in 2006, there have been remarkable advances in genetics, cell biology, computer science, artificial intelligence, social epidemiology, and health care delivery. Individual research

___________________

4 Public Law 109–482, 120 Stat. 3676 (January 15, 2007).

5 Public Law 109–482 (January 15, 2007).

investigation has given way to large interdisciplinary collaborative efforts and team science. As a result, it may be appropriate to reexamine the organization of the world’s most influential biomedical research enterprise.

Recently, members of Congress have shown interest in changing the structure of NIH. In 2024, Senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA), ranking member of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, released a white paper with recommendations to modernize NIH, including that it increase its focus on maintaining a balanced portfolio so all stages of medical research and other public health priorities are funded adequately (Cassidy, 2024). In June of 2024, Representative Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA-05), chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, released a proposal to overhaul NIH that calls for combining ICs to reduce the number from 27 to 15, concluding that the uncoordinated growth at NIH has led to research gaps and duplication of effort, stating these and other shortcomings have affected its ability to respond appropriately to new scientific and public health challenges (Rodgers, 2024) (see Chapter 1 for more information). While the idea of creating a new WHR institute seems on its face contradictory to the conclusion that uncoordinated growth is a problem at NIH, if this is implemented with appropriate oversight and accountability, such issues could be avoided while also providing the support needed for WHR. It was outside the purview of the committee to assess the pros and cons of either proposal, but it attests to the need for NIH to change as new needs surface. The committee notes, however, that neither proposal mentions women’s health or sex differences research. Such proposals are unlikely to be considered by the current Congress but could form the basis for future discussion. Any such reorganization requires careful consideration by Congress on how to integrate WHR to best meet the current and evolving needs of women.

Oversight for WHR activities by the NIH director

Establishing a new institute and research fund would provide avenues for increased funding for innovative science across ICs and research on female-specific conditions that do not fall under the priorities or purview of the 27 ICs. However, these actions do not provide a mechanism of accountability for prioritizing WHR across NIH. A new institute on women’s health would not have authority over other ICs; this duty could be given to the NIH director, the only person with direct authority over the ICs, who could set annual benchmarks with the ICs for WHR and provide an annual report to Congress on progress. This oversight is essential for the success of WHR at NIH.

A Path Forward

Based on its review, the committee concluded that the NIH structure for WHR is insufficient to catapult it forward to address the urgent need

and persistent gaps. Rather, progress will continue to be slow and stagnant for many conditions. Given the complexity of women’s health, the committee concluded that no single solution could address the support needed to develop a robust WHR enterprise. A constellation of changes is required. For example, providing ORWH with significantly more funding to partner with ICs would still leave the problems of independent administration of grants in high-need areas, coordination, authority, clout, and accountability unaddressed. Creating an institute on women’s health with a broad scope and purview would duplicate the expertise in other ICs that study health conditions that impact women more or differently than men, though currently research on women is not prioritized. Creating an institute with a narrower scope would be an effective strategy but still leave women’s health conditions that fall in the purview of other ICs underfunded. Each strategy alone would not ensure women’s health is integrated and prioritized, and each involves tradeoffs. Therefore, the committee recommends

Recommendation 1: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should form a new Institute to address the gaps in women’s health research (WHR) and create a new interdisciplinary research fund. Furthermore, NIH leadership should expand its oversight and support for WHR across the Institutes and Centers (ICs). Congress should appropriate additional funding to adequately support these new efforts. Specifically,

1a. Congress should elevate the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) to an Institute with primary responsibility to lead, conduct, and support research on female physiology and chromosomal differences, reproductive milestones across the life course, and female-specific conditions that do not fall under the purview of other ICs.

- Certain programs currently housed in ORWH, such as women’s health workforce development programs, and their corresponding budget will be part of the new WHR Institute.

- The new WHR Institute should have a dedicated independent budget comparable to that of other NIH Institutes with similar scope, amounting to at least $4 billion over the first 5 years.

1b. Congress should establish a new fund for WHR in the Office of the Director to support interdisciplinary women’s health and sex differences research with a focus on innovation and accelerating biomedical discoveries. The fund should have a dedicated independent budget comparable to that of other major NIH initiatives, such as the Common Fund, Cancer Moonshot, and BRAIN Initiative. The fund will ramp up over the first 2 years, achieving full funding of $3 billion in Year 3, with a total investment of $11.4 billion over the initial 5 years.

1c. The NIH director and IC directors should prioritize WHR. The NIH director should assume oversight and responsibility for the WHR portfolio across NIH with respect to funding allocations and implementation of priorities, such as sex as a biological variable, and policies relevant to women’s health. IC directors should increase support for WHR that falls under their purview.

- The NIH director, in collaboration with IC directors, should set annual benchmarks in the year-to-year proportion of extramural and intramural funding to be granted for WHR, following a comprehensive analysis of research needs (see Recommendation 3).

- The NIH director should evaluate progress on addressing WHR gaps and associated funding levels across NIH and should submit an annual report to Congress and to the public on the year-to-year trends by IC. The Office of the Director should receive additional funds to support NIH-wide programmatic evaluation and increased administrative responsibilities.

- The Director of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) should expand the Institute’s role to include women, girls, and females among the populations that experience disparities. Congress should increase NIMHD’s budget to adequately support including women’s health disparities research into its portfolio and coordinate this research with other ICs.

Guidance for Creating the New WHR Institute

Implementing Recommendation 1a—creating a new WHR Institute—would require a statutory change by Congress or a reorganization of ICs, since the NIH Reform Act6 limits ICs to 27. The new WHR Institute would work closely with other ICs. This includes, for example, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, which would continue its focus on human reproduction and the study of pregnancy as it relates to fetal and child outcomes. Other ICs would cofund grants or cosponsor program announcements on WHR with the new Institute. Table 9-1 lists the roles and responsibilities of the new WHR Institute proposed by the committee.

The new WHR Institute should have a dedicated independent budget comparable to that of other ICs with similar scope: $4 billion over the first 5 years followed by a reassessment at 5 years to determine if the subsequent annual budget—recommended at $800 million—is sufficient to meet the need. This is commensurate with the budgets of midsize Institutes

___________________

6 Public Law 109–482 (January 15, 2007).

TABLE 9-1 Roles and Responsibilities for Women’s Health Research at NIH: Committee Recommendations

| Existing ICs |

|

| New Women’s Health Research Institute |

|

| New Women’s Health Research Fund |

|

| ORWH |

|

| Director of NIH |

|

NOTE: BRAIN = Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies; IC = Institutes and Centers; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NIMHD = National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; OD = Office of the Director; ORWH = Office of Research on Women’s Health; WHR = women’s health research.

with a similar scope, such as the National Eye Institute, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIH, 2023a).

As the recommendation notes, the new WHR Institute would be responsible for many programs ORWH oversees, including WHR workforce programs. Increased funding for workforce programs (see Recommendation 5) and the infrastructure afforded by an Institute will allow for strategic development of the women’s health workforce. Responsibilities that require oversight to ensure accountability, such as the SABV and clinical trial inclusion policies and prioritization setting, should move to the NIH director. The new WHR Institute could not oversee policies other ICs implement, since one IC cannot oversee others. As part of its work, the WHR Institute should undertake communication and dissemination responsibility for new WHR findings and discoveries. This includes translating scientific evidence

into practice for the public, researchers, relevant medical associations and other organizations, policymakers, and industry.

One might ask, why not have an institute on men’s health? As discussed throughout this report, the majority of research focused on men’s health as the default. Diagnostic and treatment criteria based on one sex for non-sex-specific diseases has typically been based on men, leading to persistent misunderstanding and underdiagnosis of the disease in women (see Chapter 5 for examples). While NIH has made important strides toward balancing representation by sex in research, more needs to be done, including ensuring that researchers conduct sex differences analyses. Perhaps once WHR has benefited from the same dedication and resulting innovation for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment as research that has mainly focused on men, some efforts recommended for women’s health will no longer be needed, and rigorous research that benefits men and women will be the norm across ICs. Unfortunately, that is not the current state.

Guidance for the New Women’s Health Fund

The WHR Fund (Recommendation 1b) would operate much like the NIH Common Fund, supporting interdisciplinary women’s health and sex differences research with a focus on innovation and accelerating biomedical discoveries. It would also serve as a mechanism through which the NIH director can ensure all ICs have an opportunity to contribute to WHR in collaborative and innovative ways in line with their missions. The goal of the fund is to continue supporting scientific initiatives that fall under individual ICs and provide a mechanism for collaboration with the new WHR Institute.

The fund would be used primarily to support research involving collaboration between at least two ICs to encourage interdisciplinary research and submission of grant proposals in novel areas of WHR. The ICs initiating the idea would oversee successful applications. Special emphasis panels would evaluate competing grants, unless a relevant study section has at least one WHR expert.

The new fund should have a dedicated, independent budget of $3 billion per year with an initial ramp-up of $900 million in Year 1 and $1.5 billion in Year 2. The committee estimated that rapid progress requires a 10 percent increase in funding. NIH provides approximately 60,000 grants per year (Lauer, 2023), so 10 percent amounts to 6,000 grants. Using a conservative estimate of $500,000 per grant (Lauer, 2023), a $3 billion annual investment is needed. While this amount is larger than previous initiatives, such as the Cancer Moonshot and the BRAIN Initiative, it is necessary based on the committee’s assessment. This is critical given that the low rate of proportionate funding for women’s health has decreased

over the past decade, with 9.7 percent of total NIH funding in FY 2013 and 7.9 percent in FY 2023 (based on the committee’s analysis, see Chapter 4), with an average 8.8 percent investment in FY 2013–FY 2023. Overcoming the tremendous gaps in knowledge of women’s health, from understanding basic female physiology to successful prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, requires a significant investment to urgently address these gaps and offset delayed progress on improving the health of over half the U.S. population (Census Bureau, n.d.).

Role of NIMHD

NIH should increase its support of science focused specifically on health disparities among women and girls and coordinate this research with other ICs. Health disparities research furthers identification of the epidemiology and mechanisms of social and structural factors affecting disparate outcomes among women and among subgroups of women across various health conditions.

NIMHD has been a leader in increasing the scientific community’s focus on nonbiological factors, such as socioeconomics, politics, discrimination, culture, and environment in relation to health disparities. As Chapter 3 discussed, it initially focused solely on racial and ethnic disparities in health but has added several other domains. Though women and girls are not a minority group in the United States, they experience well-documented discrimination, bias, and subjugation that are root causes of health disparities (see Chapter 6). NIMHD is well suited to support research and training specifically on disparities experienced as a function of the treatment of sex, gender, and the status of women, both specifically and intersection-ally. To do so adequately, NIMHD would need significantly more funding to expand its portfolios under its Division of Clinical and Health Services Research7 and Community Health and Population Science.8 The committee was unable to develop an estimate for the increased amount, as it requires a deeper understanding of the NIMHD portfolio to do so. The committee is not proposing any new authoritative or organizational structures, but program officers with expertise in gender- and sex-related health disparities

___________________

7 “Under this research interest area, NIMHD supports a comprehensive range of clinical research and health services research to generate new knowledge to improve health/clinical outcomes and quality of health care for populations that experience health and health care disparities” (NIMHD, 2024c).

8 “The Division of Community Health and Population Science supports research on interpersonal, family, neighborhood, community and societal-level mechanisms and pathways that influence disease risk, resilience, morbidity, and mortality in populations experiencing health disparities” (NIMHD, 2024b).

would be needed if they are not already present. As the committee recommends for other ICs, this work would be coordinated by the NIH director.

Oversight of WHR by the NIH Director

Oversight and accountability within NIH, and by key external stakeholders, is essential for progress on WHR. Recommendation 1c includes routine evaluation and oversight of activities across all NIH ICs regarding funding allocations and implementation of priorities and policies relevant to women’s health. The OD will require additional funds to operationalize its WHR evaluation and oversight role, but the committee did not have the needed NIH budget information to estimate the amount. Some ORWH funds might be available, but the portion of the ORWH budget supporting existing programs, such as Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) and Specialized Centers of Research Excellence (SCORE) on Sex Differences, should be included in the budget of the new WHR Institute.

The Office of Autoimmune Disease Research (OADR) sits in ORWH and was created in the 2022 in response to a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) report, Enhancing NIH Research on Autoimmune Disease (NASEM, 2022a; OADR, n.d.). Although the Office currently sits in ORWH, it should not be moved to the new WHR Institute. Many autoimmune diseases disproportionately affect women but also affect men. The 2022 report found that “autoimmune diseases are complex and share commonalities that would benefit from a coordinated, multidisciplinary research approach to better understand basic mechanisms, etiology and risk factors, and to support the development of interventions to mitigate the impact of autoimmune diseases and associated co-morbidities and complications across the lifespan” (p. 417) and that the best option for addressing these challenges and opportunities would be creating an Office of Autoimmune Disease in the OD. Therefore, this is one possible option.

Summary of Recommendation 1

Recommendation 1 is fundamental to advancing WHR at NIH. If the same structure remains, progress on WHR will continue to be slow, incremental, sporadic, and insufficiently responsive to women’s urgent health needs. While the infrastructure for the new WHR Institute and Fund is being developed, ORWH should continue its role. Should a new WHR Institute not be created, the next best solution would be for ORWH to have a significant and meaningful infusion of funding, as with money comes influence, and that would allow it to partner with more ICs on identified priorities for WHR and workforce development across NIH. However,

oversight is needed at a high enough level to ensure priorities are met, which would still be lacking.

STRENGTHEN OVERSIGHT, PRIORITIZATION, AND COORDINATION FOR WHR ACROSS NIH

Tracking NIH Investments in WHR

As discussed in Chapter 4, the NIH Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization (RCDC) system is unable to accurately report the proportion of the NIH budget devoted to WHR overall or for specific conditions within women’s health. The committee suggests alternative accounting systems and methods to improve accuracy. Due to multiplicative counting of grants in RCDC categories, misclassifications, and other factors, the system is inadequately designed to guide budget allocations and inform Congress and the public on how much is spent in distinct research areas.

Conclusion 4: The Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization (RCDC) system—the system designed to sort National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded projects into scientific categories for reporting to the public by conditions, diseases, and research area—does not provide accurate estimates of NIH spending on women’s health research. The RCDC system, in its current form, is inadequate for guiding budget allocations; for informing Congress and the public on how much is spent in any distinct research area, by condition or disease, or by Institute or Center; or for reliably tracking changes in funding over time.

Recommendation 2: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should reform its process for tracking and analyzing its investments in research funding to improve accuracy for reporting to Congress and the public on expenditures on women’s health research (WHR).

2a. The new process should improve accuracy of grants coded as Women’s Health and eliminate duplicate or multiplicative counting of grants across Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization (RCDC) categories. This may be achieved by applying proportionate accounting of grants to generate more accurate estimates for categories related to WHR.

2b. NIH should update its process for reviewing, revising, and adding new RCDC categories that pertain to WHR.

2c. NIH should make transparent and accessible the process and data used for portfolio analysis so researchers, analysts, and the public can examine and replicate NIH investments into research for women’s health.

Recommendation 2, and retrospective funding analyses, should be facilitated by expanding the use of modern data analysis methods, such as large language models (LLMs; see Chapter 4 and Appendix A) that can efficiently identify and categorize content of a grant with equal or superior accuracy and reliability compared to historical systems. The committee’s funding analysis could serve as a model for NIH to refine and test. The committee used LLMs because of their ability, as very large deep learning models, to process human language and derive predictions on vast amounts of similar data based on pretraining. A successful LLM algorithm can accurately identify and categorize a grant as related to women’s health based on all available relevant information, just as a human should be able to confidently perform the same task after learning from experience and training what kind of title, abstract, or narrative is characteristic of such a grant. NIH is already using LLMs for some aspects of its portfolio analysis (NASEM, 2024b); further development and expansion of these approaches to more efficiently and effectively assess spending on WHR are needed. Because state-of-the-art LLMs can be especially helpful for identifying and categorizing investments in biomedical areas that are crosscutting, including WHR, newer LLM methods can also be used to accurately analyze the allocation of funding for many other research areas supported by NIH. Furthermore, updated methods may allow NIH to track a more extensive set of diseases and conditions, given their ability to quickly assess funding-related data.

Priority Setting for WHR

The significant gaps in WHR at NIH are the result of the substantial historical underrepresentation, lack of accountability, inadequate funding, and dearth of comprehensive research that have long characterized this field. Decades of insufficient focus have resulted in critical knowledge deficits and disparities in health outcomes for women. Investments in WHR need to be allocated in a targeted way to ensure it bridges these research gaps. The prioritization process is failing to establish or implement cohesive and cross-agency priorities for WHR, resulting in a lack of responsiveness to critical research gaps and perpetuating knowledge gaps (see Chapter 3). To address these issues, a comprehensive, NIH-wide prioritization process is needed.

Conclusion 5: Most National Institutes of Health (NIH) Institutes and Centers (ICs) have a strategic plan to inform their research priorities, but these plans rarely mention women’s health. In addition, the strategic plans of the ICs do not include elements of the NIH-Wide Strategic Plan for Research on the Health of Women, which outlines important

strategic priorities. The timing of the IC plans varies significantly, with some at the beginning, middle, or end of their respective timelines when the agency-wide plan is released. This complicates NIH’s ability to set, implement, and oversee cohesive and cross-agency priorities for women’s health research that are responsive to critical research gaps. Furthermore, the data and input used to inform these plans are not always clear. To address these issues, a comprehensive prioritization process is needed—one that fully uses available data and community input.

Recommendation 3: The Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) should develop and implement a transparent, biennial process to set priorities for women’s health research (WHR). The process should be data driven and include input from the scientific and practitioner communities and the public. Priorities of the director and the Institutes and Centers (ICs) should respond to the gaps in the evidence base and evolving women’s health needs. To inform research priorities for women’s health, NIH should

3a. Employ data-driven methods, such as epidemiologic studies and disability or quality-adjusted life years, to assess the public health effect of conditions that are female specific, disproportionately affect women, or affect women differently. NIH should report this assessment publicly and use it, in combination with other analyses as needed (e.g., of expected return on investment), to identify research priorities and direct funding for WHR.

3b. To ensure priorities for WHR are implemented, ICs should issue Requests for Applications, Notices of Special Interest, Program Announcements, and similar mechanisms, in addition to current funding activities.

This process would allow IC directors to still have discretion to enact their strategic priorities and address emerging issues (such as during the COVID pandemic), while also being held accountable to ensure that women’s health and sex differences research is prioritized.

EXPAND, TRAIN, SUPPORT, AND RETAIN THE WHR WORKFORCE

To address WHR, it is essential to have a robust and productive NIH intramural and extramural research workforce with broad expertise in biomedical research, clinical trials, and implementation science. The committee found that NIH support of the WHR workforce falls short of what is needed to address the unmet needs of women’s health (see Chapter 8). Investment is needed to develop the next generation of researchers. IC

program staff also need expertise in women’s health for effective prioritization and coordination. Inadequate funding of WHR has led to an insufficient number of investigators and even fewer with interest and expertise in women’s health at the intersection of other important social identities, including race and disability.

WHR Career Pathways

Chapter 8 underscores the need for NIH and other stakeholders to comprehensively prepare a broad-based effort to train a robust research workforce that meets the needs for WHR. Achieving this goal requires a multifaceted, coordinated approach, including substantial support for training and retaining both laboratory-based researchers and physician-scientists specializing in women’s health. Addressing workforce issues throughout the research career continuum—from high school through midcareer—is crucial. This includes enhancing educational opportunities for scientists at various stages, such as clinical and doctoral training programs. Recommendations 4 and 5 highlight opportunities to build and support the WHR workforce across the entire spectrum of career development.

Conclusion 6: Establishing a robust infrastructure for intra- and extramural research in women’s health and sex differences at the National Institutes of Health is critical to success. The Institute and Center program staff need a high level of expertise in women’s health for effective prioritization and coordination. This infrastructure is needed to cultivate a vibrant women’s health workforce, provide essential support for grantees and early-career researchers through funding and mentoring, and instill confidence in stable funding, thereby attracting researchers to women’s health research topics.

Conclusion 7: Inadequate funding of women’s health research (WHR) has led to an insufficient number of WHR investigators and even fewer with interest and expertise in studying women’s health at the intersection of other important social identities, such as race and disability. A coordinated approach to attracting and supporting researchers across their careers to make meaningful discoveries in women’s health is needed. The current grant mechanisms are inadequate to support career trajectories in WHR. Increased funding allocation and expanded numbers of career support grants for early-career investigators in WHR are needed from mentorship to conception of ideas for grant proposals, including sponsorship, mentorship, and protected time through training grants.

Conclusion 8: Mentorship and career development are vital to the development of the extramural women’s health research (WHR) workforce and for maximizing research dollars spent. Many institutions do not have the needed funding to support early-career clinician-scientists, particularly in surgical subspecialties, including obstetrics and gynecology. National Institutes of Health research funding does not provide funding for mentors in many WHR training grants, which is critical for progress.

Conclusion 9: Gender-based bias and sexism persist in the United States, including in its health and research systems. For the National Institutes of Health (NIH), these biases affect the grant review and award-making processes, from the initial application and review stages to funding allocation and the accumulation of multiple grants. NIH has acknowledged these issues and has implemented initiatives to address them. However, the research suggests that significant disparities remain, and further structural changes may be necessary to achieve equity in the grant-making process.

Conclusion 10: In addition to sexism, bias related to race and ethnicity has been identified as an independent and intersectional contributor to gaps in health research generally and women’s health research specifically.

Recommendation 4: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should augment existing and develop new programs to attract researchers and support career pathways for scientists through all stages of the careers of women’s health researchers.

4a. NIH should create a new subcategory within the Loan Repayment Program (LRP) for investigators conducting research in women’s health or sex differences. K awardees who study women’s health or sex differences should be automatically considered for an LRP grant. For every year in the program, awardees should receive loan repayment assistance up to $50,000 for up to 5 years, allowing up to $250,000 in loan repayments.

4b. NIH should create new and expand existing early-career grant mechanisms (K, T, and F grants) that specifically support growing and developing the women’s health research workforce. Appropriate models for new mechanisms are the Stephen I. Katz and Grants for Early Medical/Surgical Specialists’ Transition to Aging Research awards. These grants should prioritize early-career investigators with innovative approaches focused on women’s health.

4c. NIH should create new and expand existing midcareer investigator awards to support and promote the midcareer women’s health

research workforce (e.g., K24, R35, U, P, and administrative supplement grants).

4d. NIH should allow financial support of up to 10 percent, as a line-item component, for mentors (primary or designee mentor) on all mentored grants, such as F31, K01, K99, and T32 grants, that support careers of early and midcareer investigators in women’s health and sex differences research.

4e. All early-career mentored institutional K-awards should be supported up to 5 years to increase the likelihood of retaining a workforce to study women’s health.

The LRP is critically important to address the lifelong bias that disadvantages women economically and could ensure appropriate diversity within the workforce (see Chapter 8 for more information).

Creating new early-career mechanisms for WHR (Recommendation 4b) can be modeled on existing mechanisms. For example, the Stephen I. Katz award is an R01 research project grant for early-stage investigators’ innovative projects that are a change in the research focus and have no preliminary data; it is intended to encourage innovation and new approaches by supporting new disciplines, techniques, targets, or methodologies (NIH, 2023c,d, 2024e). The award is open to research relevant to participating ICs’ missions. Another example is the Grants for Early Medical/Surgical Specialists’ Transition to Aging Research (GEMSSTAR) program from the National Institute on Aging aimed at early-career dentist- and physician-scientists starting a career in aging research in their clinical specialty area (NIA, 2024). To help meet the health care needs of the aging U.S. population with complex medical issues, the program is open to scientists with medical, surgical, or dental training in any specialty whose aging-related research will improve care and treatment options for older patients. Special emphasis panels with appropriate expertise review grant applications (Eldadah, 2021). This approach could be augmented for WHR. Though not a career development award, it uses the research grant (R03) mechanism to support the research project but also requires a professional development plan supported by non-R03 funding sources that includes activities concurrent with the R03 award that provide training and mentorship in aging science (NIA, 2024). GEMSSTAR awards can be a solid basis for competitive K applications (Eldadah, 2021). The new grants should target researchers interested in changing their field of study to involve a new or a more deliberate focus on women’s health, including those from fields other than medicine, such as engineering, looking to use their skills to support WHR. It is also essential to ensure opportunities for midcareer investigators to further refine their skills and allow them to support early-career investigators (see Recommendation 4e). For example,

the K24, R35, U, P, administrative supplement,9 and similar grant mechanisms could be expanded (not all ICs offer these) and/or new mechanisms developed.

Another important consideration for the WHR workforce is the impact of caregiving on an individual’s ability to fully participate in the NIH community, whether that be applying for grants or participating on NIH study sections or meetings. The 2024 National Academies report Supporting Family Caregivers in STEMM: A Call to Action has actionable recommendations to shift structural and policy solutions to increase women’s and other primary caregivers’ ability to participate in science (see Chapter 8 for more on this topic and the 2024 report [NASEM, 2024c]).

Expand WHR Workforce Development Programs

Several WHR workforce development programs the committee reviewed have been effective at launching and supporting researchers’ careers. Increased funding and expansion of successful programs—BIRCWH, SCORE, Women’s Reproductive Health Research (WRHR) Career Development Program, and Research Scientist Development Program (RSDP)—are vital to support and sustain these efforts. By addressing these critical issues and leveraging proven programs, NIH can help build a robust research workforce capable of addressing the complex needs of women’s health (see Chapter 8).

Recommendation 5: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should augment existing and develop new grant programs specifically designed to promote interdisciplinary science and career development in areas related to women’s health. NIH should prioritize and promote participation of women and investigators from underrepresented communities.

5a. NIH should double the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) program to achieve a total of 40 centers, with 6 new centers awarded in the next fiscal year and 5 centers each of the following 3 fiscal years. NIH should augment funding for each center to $1.5 million annually, amounting to a total of $60 million per year for the enhanced BIRCWH program.

5b. NIH should expand the Specialized Centers of Research Excellence (SCORE) on Sex Differences program by engaging Institutes and

___________________

9 See, for example: Notice of Special Interest (NOSI) NOT-OD-24-001: Administrative Supplements to Recognize Excellence in Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA) Mentorship (https://diversity.nih.gov/act/DEIA-mentorship-supplements; accessed September 30, 2024).

Centers (ICs) to add 5 additional centers to achieve a total of 17 centers over the next 3 to 5 fiscal years. At least three of these centers should reside in the new Women’s Health Research Institute (see Recommendation 1). The NIH director should provide incentives for other ICs to participate in this program, which could include the provision of matching funds from the Office of the Director. NIH should augment funding for each SCORE to $2.5 million annually, amounting to a total of $42.5 million annually for the enhanced SCORE program, with long-term commitment of funds to renew SCORE programs that meet their goals.

5c. NIH should fund additional multi-project program grants, with or without built-in training components, that focus on women’s health research (e.g., P and U grants) to both expand research on these topics and to support researchers studying women’s health across the career spectrum.

5d. NIH should expand the Women’s Reproductive Health Research (WRHR) program to include 5 additional centers to achieve a total of 20 centers over the next 2 fiscal years. Existing centers that have demonstrated successful metrics should receive funding to host additional scholars. The funding for each center should be augmented to $500,000 annually, amounting to a total of $10 million annually for the enhanced WRHR program.

5e. NIH should expand the Research Scientist Development Program (RSDP) to support 10 scholars with full support, including salary, supplies, and travel, for a total of 5 years, amounting to $1.25 million annually for the enhanced RSDP program.

Any expansion should include additional funding to ensure that existing research budgets are not reduced. These programs should be distributed across the country, and grantee institutions should collaborate with other disciplines within their organization to offer mentees a comprehensive and multidisciplinary research experience. The expansion of these programs should be coupled with NIH IC programmatic staff support.

Regarding 5b, SCORE operates differently than the other workforce programs in that funding depends on an IC’s interest in and capacity for it.10 The structure constrains the number of possible topics, since SCORE relies on IC participation. To incentivize participation, NIH could change the structure of SCORE grants such that there is cost-sharing with substantial or matching funds from the OD or from the new WHR Fund (see Recommendation 1). Ideally, each IC would support at least one SCORE to

___________________

10 For example, the 2024 SCORE Request for Applications (RFA) only included eight Institutes (NIH, 2022).

expand the impact of the program, as it builds both the evidence base for WHR and careers across the spectrum of career development. Implementation of Recommendation 5c would also support researchers who focus on women’s health across the career spectrum. As the WHR workforce grows, implementing Recommendations 4c and 5c will become increasingly important to assure resources are available to support midcareer and senior faculty and ensure a solid career trajectory in WHR. These recommendations will also increase opportunities to fund innovative WHR, which could be funded in part by the WHR Fund.

Metrics to track success of these programs for workforce development include if those participating receive additional NIH funding, including R01 or equivalent grants, stay in academia, or participate as reviewers in special emphasis panels or study sections. See later in this chapter for a discussion on metrics.

The augmented funding for each program allows for different needs, including a line item to cover mentor time, funding to cover travel and supplies, and additional protected time for grantees to engage in clinical research. For example, funding for BIRCWH has been sparse. For example, the 2024 RFA set a maximum of $840,000 per year per center in direct costs (NIH, 2024d). This typically does not allow for support for mentors. Thus, the increase will almost the double funding per center and double the number of centers to broaden geographic diversity and expand overall impact.

Funding for SCORE has been lean, at a maximum of $1.5 million per year per center in total costs, with up to about $1 million in direct costs per year in the most recent RFA. This typically does not allow for full potential program development or any support for mentors contributing to the career enhancement core. The recommendation is to substantially increase funding per center and the total number of centers to broaden geographic diversity and expand overall impact. Similarly, adding five centers to the WRHR program will expand its reach, and increasing funding from approximately $315 to $500 million in direct costs per center will allow for more mentorship and protected time for research (NIH, 2024c). The RSDP program suffered cuts in recent years and can only partially cover its scholars using NIH funds (see Chapter 8 for more details on how RSDP is structured) (Schust, 2024). Increasing funding for each scholar from about $110,000 to $125,000 per year will allow for covering travel and supply costs. Adding three additional scholars will help grow the workforce of obstetricians and gynecologists who are most likely to address female-specific diseases, such as gynecologic cancers, fibroids, endometriosis, vulvodynia, and obstetric-related conditions.

OPTIMIZE NIH PROGRAMS AND POLICIES TO SUPPORT WHR

Peer Review

The peer review process is complex, with the Center for Scientific Review (CSR) overseeing tens of thousands of grants each year through a rigorous and thorough process on varied topics and areas (CSR, 2024). While progress has been made in many aspects of the peer review process, and concerted efforts by CSR continue, efforts to increase expertise on women’s health in the process will continue to be essential moving forward. (See Chapter 3 for a discussion of a variety of proposals from academia and others to improve the peer review process and actions already underway by CSR).

Conclusion 11: Representation of women’s health expertise is essential during the National Institutes of Health (NIH) peer review process—including expertise of staff in the Center for Scientific Review, Institute and Center program officers and council members, and peer reviewers. Despite NIH efforts to expand the cadre of reviewers with women’s health research (WHR) expertise, a large proportion of WHR–related grants are evaluated by special emphasis panels, not standing study sections, indicating that standing study sections do not yet have the required expertise to review WHR grants.

Recommendation 6: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should continue and strengthen its efforts to ensure balanced representation and appropriate expertise when evaluating grant proposals pertaining to women’s health and sex differences research in the peer review process.

6a. NIH should sustain and broaden its efforts to systematically employ data science methods to identify experts, use professional networks, and recruit recently funded investigators.

6b. The NIH Center for Scientific Review (CSR) should expand the Early-Career Reviewer program to enroll qualified individuals from underrepresented areas of expertise in women’s health and include women’s health, sex differences, and sex as a biological variable training for participants.

6c. CSR should work with NIH-funded institutions to identify qualified individuals with expertise in women’s health. Institutions would provide rosters of trained reviewers to CSR to enrich the pool of reviewers.

6d. In the immediate term, special emphasis panels should be used more often to ensure that applications for women’s health and sex differences research receive expert and appropriate reviews.

SABV Policy

The NIH SABV policy, implemented in 2016, is designed to recognize the importance of sex in research and address the persistent exclusion or underrepresentation of females in preclinical and clinical research (Arnegard et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2017; ORWH, 2023) (see Chapter 3). Despite efforts by NIH to implement SABV policies across investigator-initiated scientific projects, uptake and application in practice has been suboptimal (Arnegard et al., 2020; White et al., 2021), hindering the potential generation of knowledge that could help to address sex disparities and improve women’s health. ORWH has developed resources and training materials on the SABV policy and on sex and gender research for the research community, but the training has room for improvement—particularly in tailoring education for scientists conducting research in certain fields and using certain methodologies wherein SABV considerations may not be intuitive (see Chapter 3 for more information). There are opportunities to improve implementation of the SABV policy in NIH-funded research in part by incentivizing or requiring researchers to be accountable for proposing and conducting sex-specific analyses.

Conclusion 12: Addressing the persistent and extensive gaps in knowledge about how conditions disproportionately affect, present in, and progress differently in women requires that sex as a biological variable be meaningfully factored into research designs, analyses, and reporting in vertebrate animal and human studies.

Conclusion 13: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) sex as a biological variable (SABV) policy was an important advancement, and the number of grants addressing SABV has increased since the policy was implemented. However, overall uptake and application of SABV in practice has not been optimal. This is in part due to a lack of practical, field-specific SABV knowledge and experience among investigators as well as limited NIH oversight and assurance of implementation.

Conclusion 14: Although guidance and trainings on the National Institutes of Health sex as a biological variable (SABV) policy outline distinctions between sex and gender and indicate in some ways that studies of gender satisfy adherence to the policy, the current policy’s language and implementation is not clearly geared toward studies of gender, gender identity, and intersex status. Explicit guidance on addressing intersex status and conditions and gender identity across its continuum within the SABV policy is needed.

Conclusion 15: There remains no cross-agency mechanism at the National Institutes of Health for assessing how sex as a biological variable (SABV) in grants is evaluated or for tracking appropriateness and completeness of SABV implementation in the conduct of research. Furthermore, there are no consequences for grantees if they do not implement the plans for SABV included in their grant proposals, and there are no incentives to do so.

Recommendation 7: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should revise how it supports and implements its sex as a biological variable (SABV) policy to ensure it fulfills the intended goals. For its intramural and extramural review processes, where applicable:

7a. NIH should expand education and training resources for investigators on how to implement SABV, with separate programs that are more effectively tailored for scientists in distinct fields (e.g., basic, preclinical, clinical, translational, and population research).

7b. NIH should ensure that SABV is consistently and systematically reviewed. Reviewers should be required to undergo training to enable them to assess SABV in proposals and grant applications.

7c. The NIH Center for Scientific Review should, as part of the competitive renewal applications process, include an evaluation of grantee efforts and publications relating to previously proposed studies of SABV as it applies to the project funded in the last cycle, as well as that proposed in the current renewal application.

7d. To strengthen and foster research designed to rigorously examine sex, gender, or gender identity differences aimed at providing new insights into women’s health, that research should

- Be protected from across-the-board budget cuts to protect the sample sizes and analyses needed to study sex differences.

- Have access to administrative supplements to ensure sex, gender, and gender identity differences can be studied rigorously and with adequate sample size.

- Have priority for funding when such projects fall in the discretionary range of the payline.

- Undergo a streamlined process for requesting higher budgets than those allowed by the program announcement or request for proposal.

7e. NIH should expand the SABV policy in human studies to explicitly factor the effect of biological sex, gender, and gender identity in research designs, analyses, and reporting to promote research on sex and gender diversity, including intersex status, gender

expression, and nonbinary-identified populations. This expansion may involve adapting the policy language.11

Although Recommendation 7d would afford a status to grants that focus on SABV that is not available to all grants, the committee believes these actions are needed to incentivize and support investigators intending to address SABV meaningfully and support them in doing so. Research on sex differences benefits the entire population because, when sex is completely accounted for in study designs and analyses, the resulting discoveries have importance and impact for both sexes. After the study of sex differences becomes more consistently incorporated into NIH-funded research, these protections can be revisited. In addition, women-only cohorts should not be at a disadvantage based on the SABV requirement, given the lack of research on female-specific conditions.

INCREASE NIH INVESTMENT IN WHR

The committee was asked to “determine the appropriate level of funding that is needed to address gaps in women’s health research at NIH” and recommend “the allocation of funding needed to address gaps in women’s health research at NIH.”

Defining the appropriate amount of funding is an ambiguous task, with many ways to conceptualize it. However, the committee interpreted this as a request to identify the level of funding necessary to catapult new efforts and bolster existing investments in NIH-supported WHR over the next 5 years and into the future.

Researchers are only beginning to understand the complexities of sex differences in health. Research on many female-specific conditions as well as research on the impact of gender and society on women’s health has been neglected. To close this knowledge gap—compared to conditions that have benefited from extensive scientific understanding in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment—significant funding is essential. Even with adequate support, it will take decades to address these issues. Additionally, as research needs and gaps evolve, NIH needs to commit to sustaining efforts for WHR.

For example, a 2023 analysis found that $2.7 billion was spent globally on breast cancer research from 2016 to 2020, which was 11.2 percent of the total $24.5 billion invested in cancer research (McIntosh et al., 2023). NCI estimates show it spent approximately $2.7 billion during that time period (NCI, 2024). Of course, NIH research on breast cancer

___________________

11 Recommendation 7 was changed after release of the report to clarify that it applies to both extramural and intramural research.

started much earlier—Congress appropriated $25 million for it in 1991 in the Army’s Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation Program, laying the groundwork for decades of successful research (IOM, 1997). Other organizations have funded breast cancer research as well, synergistically building the knowledge base, but this has taken decades of investment, and effective grassroots advocacy made breast cancer a national research priority (Osuch et al., 2012). But, as Chapter 7 noted, despite significant progress, important research gaps still remain for breast cancer. Considering the nascent state of research on numerous female-specific conditions, along with the gaps in understanding differences in health effects between sexes, the substantial investment dedicated solely to breast cancer for early detection and effective treatment underscores the vast resources that would be required to achieve comparable advancements across all women’s health conditions.

If making progress on WHR is a priority for NIH, the committee concluded that more than an increase in funding is needed. Augmented funding needs to be supported by enhanced accountability, rigorous oversight, prioritization, and seamless, sustained integration of women’s health across all NIH structures and processes. The committee notes in its recommendations and surrounding text where increased funding will be needed to advance WHR and increase the workforce and expertise in women’s health.

Table 9-2 summarizes where funds are needed based on the committee’s recommendations to address research gaps. Sometimes, the information to estimate the amount to implement a recommendation was not available. NIH will need to assess those instances, as it requires more detailed knowledge of operational costs and capacity than is publicly available.

The committee recommends $15.71 billion in new funding be appropriated to invest in women’s health and sex differences research and workforce development over the next 5 years. This includes an initial ramp-up of the new women’s health fund—$900 million in Year 1 and $1.5 billion in Year 2—and therefore an estimated annualized investment of approximately $3.87 billion in new funding in Years 4–5 to implement the recommended actions by the committee. Over the 5-year period, this would approximately double the average NIH yearly investment in WHR (which was $3.41 billion on average over the past 5 years based on the committee funding analysis). However, as noted, additional funds will be needed to cover operational costs, increased oversight by the NIH director, and increased funding for NIMHD. The level of funding recommended by the committee aligns with recommendations by other groups or organizations in recent years. For example, the White House called for a $12 billion investment in new funding for WHR at NIH, and Women’s Health Access Matters called for doubling the WHR budget based on 2021 analyses (Baird et al., 2021; White House, 2024) (see Chapter 1 for more information).

TABLE 9-2 New Funding Needed to Accelerate Progress to Fill the Women’s Health Research Knowledge Gap

| New Funding (in Millions of Dollars) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Action | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | Total 5-Year Funding (New) | Total 5-Year Funding (New and Existing) |

| New Institute | $800.000 | $800.000 | $800.000 | $800.000 | $800.000 | $4,000.000 | $4,000.000 |

| New Fund | $900.000 | $1,500.000 | $3,000.000 | $3,000.000 | $3,000.000 | $11,400.000 | $11,400.000 |

| Expanded Workforce Programs* | $42.770 | $56.795 | $66.795 | $74.295 | $74.295 | $314.950 | $314.950 |

| Total New Funding | $1,742.770 | $2,356.795 | $3,866.795 | $3,874.295 | $3,874.295 | - | $15,714.950 |

| Existing Research Funding for WHR^ | $3,405.000 | $3,405.000 | $3,405.000 | $3,405.000 | $3,405.000 | - | $17,025.000 |

| Total Funding | $5,147.770 | $5,761.795 | $7,271.795 | $7,279.295 | $7,279.295 | $15,714.950 | $32,739.950 |