Impacts and Performance of State DOT Resilience Efforts (2025)

Chapter: Appendix A: Literature Review

TABLE OF CONTENTS

HISTORY OF PERFORMANCE MEASURES

Defining and Evaluating Performance Measures

Performance Measure Typologies

Classifying Performance Measures: Availability, Productivity, and Quality Measures

TRANSPORTATION PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT

Performance Based Planning and LRTPs

Performance Measures supporting Agency Objectives

Factors for Success and Lessons Learned

Monetizing Annual Risk to Highway Assets

Critical Infrastructure Sectors

Cybersecurity and Information Technology (IT)

RESILIENCE AND DOT PROJECT DEVELOPMENT LIFE CYCLE

RPMs and the Planning to Operations Continuum

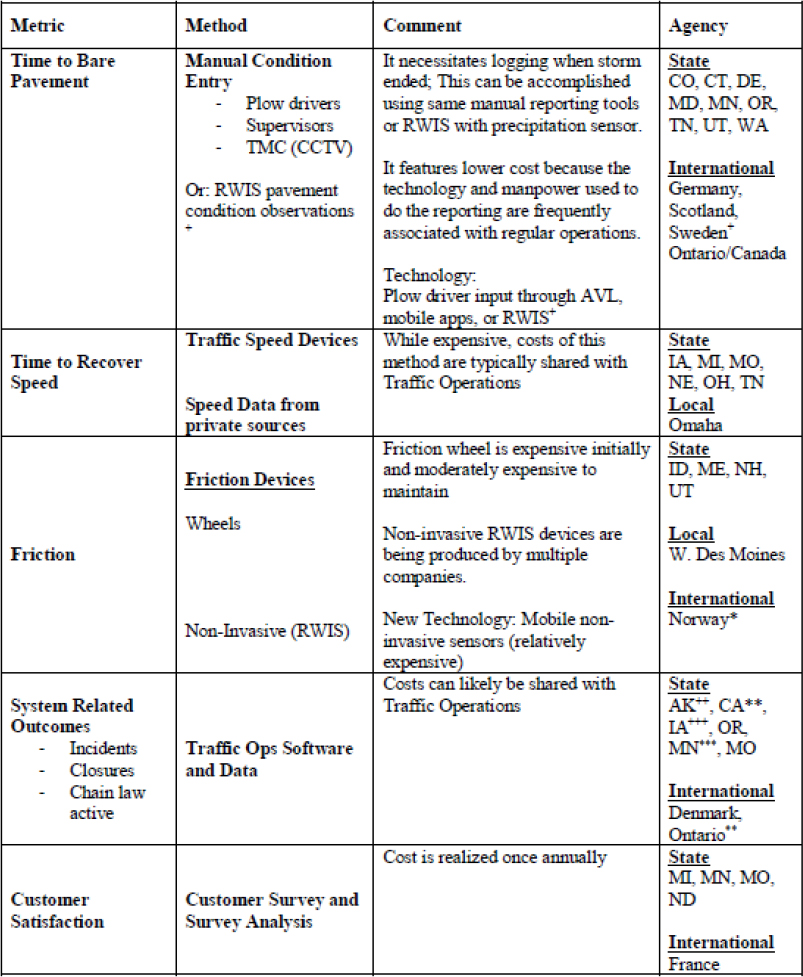

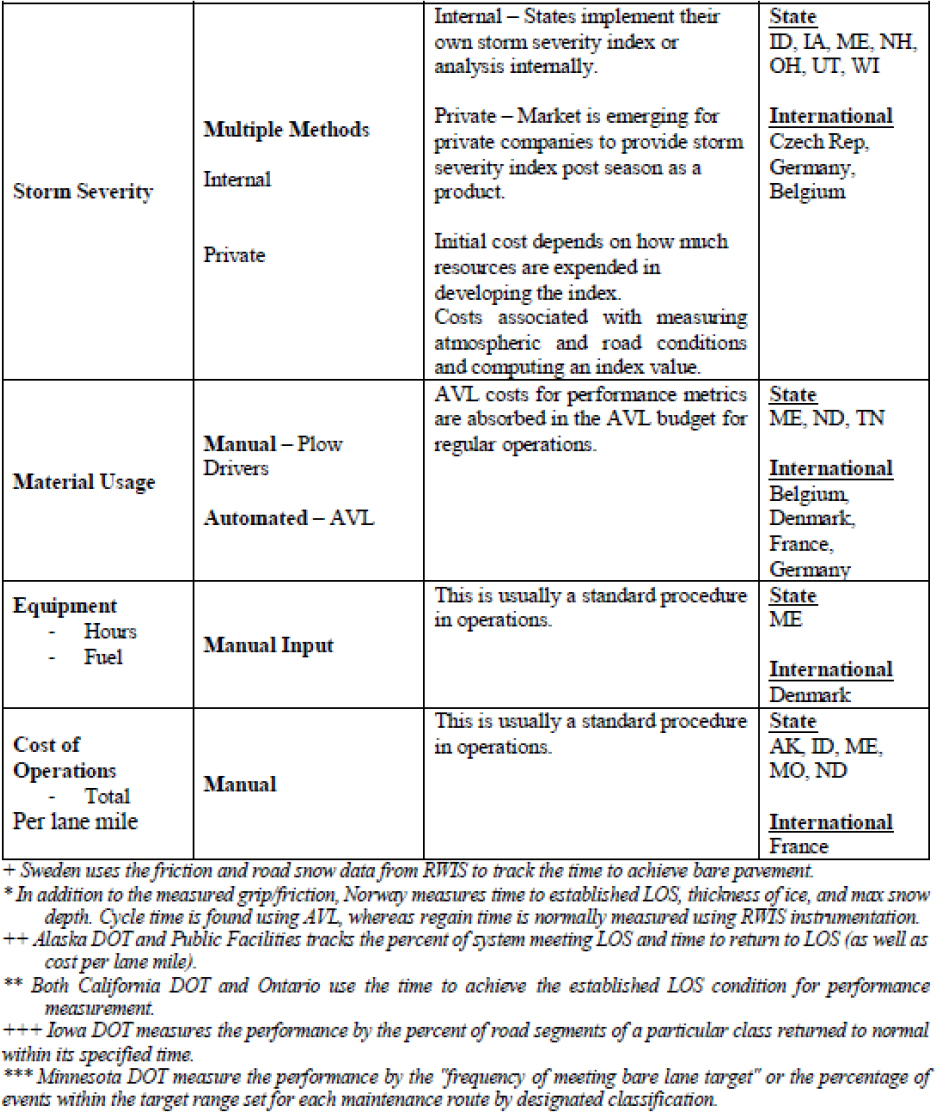

These performance metrics were collected through a series of

Use of RPMs in FEMA Continuity of Operations Plan (COOP)

INCORPORATING COMMUNITY RESILIENCE

Community Resilience in RPM Selection & Evaluation

Measuring Social & Community Resilience to Hazards & Stressors

Building a Case for Resilience Investments

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 Performance Measurement Process

Figure 2 Performance Measure Typologies Flow

Figure 3 Sustainability Performance Measure Framework

Figure 4 Critical Infrastructure Sectors

Figure 5 Utility Resilience Index (URI) Indicators

Figure 6 Assessable or Measurable Aspects of Cyber Resiliency for a System

Figure 7 Cyber Resiliency Metrics Can Repurpose Security, Risk, or Resilience Metrics

Figure 8 Proposed Infrastructure Resilience Indicators and Their Relation to Absorb and Recover

Figure 9 Infrastructure Indicators for What Will Happen During the Hazard Event

Figure 10 Infrastructure: Indicators of What Will Happen After the Hazard Event

Figure 11 Benefits of Collaboration for Performance Measures

Figure 12 Eleven Aspects of Resilience

Figure 13 Acceleration of Deterioration Rates

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Literature Review Topics and Sub-Topics

Table 2 FHWA Performance Measures

Table 5 Resiliency Metrics/Measures

Table 7 Example of Energy Resilience Metrics for Electricity Systems at the Facility/System Level

Table 8 Examples of Grid Resilience Metrics for Consequence Categories

Table 9 Examples of Resilience Metrics by Type of Resilience

Table 10 Performance Measures Examples for Asset Management

Table 12 Overview of Case Studies

Table 13 Tools to Measure Social & Community Resilience to Hazards & Stressors

Introduction

Given the impacts of short-term events and long-term stressors, including natural hazard variability, state departments of transportation (DOTs) need tools and approaches to track resilience efforts and investments and measure progress toward improving the resilience of transportation systems. To fulfill this need, the objectives of NCHRP Project 23-26, “Measuring Impacts and Performance of State DOT Resilience Efforts,” are to

- Identify or develop key resilience performance measures (RPMs) for State transportation agencies for roadway transportation systems for various classes of assets (e.g., bridges, intelligent transportation systems (ITS), pavement, culverts);

- Develop an approach that uses performance measures to assess the effectiveness of resilience strategies; and

- Develop a guide to aid state transportation agency practitioners in applying RPMs.

This report documents the results of the first task in this research effort that conducts a literature review of the state of practice related to performance management in transportation and measuring the resilience of highway assets and systems. The objective of this review is to compile and present relevant practice, performance data, research findings, and other information pertaining to the identification and performance of key RPMs for State transportation agencies for roadway transportation systems for various classes of assets.

Overview and Topics

This document will cover findings from the literature on six topics, with two to seven sub-topics each, as listed in Table 1. These topics were developed to build off of recent research into understanding, measuring, and investing in transportation system resilience. The chosen topics ensure that the project team and users of this research have a thorough and common understanding of performance measurement in the transportation field, how to define and measure different components of resilience, and how to successfully implement RPMs into agency decision making. An initial set of topics was presented to the project panel at the January 30, 2023, kickoff and the outline for the literature review was finalized following that meeting after incorporating input from the panel.

Table 1. Literature Review Topics and Sub-Topics

| Topic | Subtopic |

|---|---|

| History of Performance Measures | What are performance measures? How are they evaluated? |

| How performance measures can be classified (typologies) as process, output, and outcome measures. | |

| How RPMs can be classified as availability, productivity, and quality measures. | |

| Transportation Performance Management (TPM) | Review previous efforts of TPM guidebooks, manuals, training, and methods for widespread use and successful adoption. Discuss how they define PMs and connect them to vision and goals, using examples from Long-Range Transportation Plans (LRTP). |

| What makes TPM programs successful, and what have practitioners learned from other TPM initiatives? |

| Topic | Subtopic |

|---|---|

| Measuring Resilience | This includes the definitions, calculation methods, typologies, indices, and recommendations for developing RPMs. |

| This will include a special focus on how agencies calculate monetized annual risk to highway assets. | |

| Allied sectors: water/wastewater. | |

| Allied sectors: energy. | |

| Allied sectors: cybersecurity and information technology. | |

| International Experience. | |

| Incorporate RPMs that are tied to funding and grant programs such as the Promoting Resilient Operations for Transformative, Efficient, and Cost-Saving Transportation (PROTECT) program. | |

| Resilience and DOT Project Development Life Cycle | RPMs and the Planning to operations continuum. |

| Review Transportation Asset Management Plans (TAMPs) that identify current and future extreme weather to roadway transportation assets as they face varying deterioration due to changing frequency of hazards. | |

| Incorporating Community Resilience | Incorporating community resilience into selection of RPMs and evaluation approaches for effectiveness of resilience initiatives. |

| Review of ways to measure social and community resilience to hazards and stressors. | |

| Implementation Considerations | Identify how leadership plays a role in implementing resilience and encouraging the use of RPMs. |

| Review resources that can help practitioners build support from leadership for resilience investments. |

The remainder of this document is organized into sections for each of the six topics of the literature review. Additionally, the end of each section includes a call-out box that summarizes takeaways from the literature review, identifies gaps in the state of practice, and ties the topic to the resilience transportation practice and the anticipated products of this research effort.

History of Performance Measures

Defining and Evaluating Performance Measures

Performance measures are used to monitor and report on a program or project’s progress and results, providing data and insight into the effectiveness and efficiency of the project (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2023). They are based off metrics and measures, defined below (23 CFR 490.101):

- Metric – a quantifiable indicator of performance or condition. Example: annual number of fatalities.

- Measure – An expression based on a metric that is used to establish targets and to assess progress toward achieving the established targets. Example: A five-year rolling average of number of fatalities.

Performance measurement is defined as the use of statistical evidence to determine progress toward specific defined organizational objectives (US Department of Transportation, 2020). Therefore, a performance measure is an indicator that is used to monitor and report on a program or project’s progress toward meeting established targets. The TPM Toolbox also includes definitions for these terms and others, including “baseline” and “goal” (Federal Highway Administration, 2024).

Source: Original Graphic

Performance measures are chosen to measure the goals and objectives of a project, which are determined at the outset. Goals are broad statements about the desired state of the transportation system and reflect societal concerns and aligned to the overall agency mission. Objectives are more specific and actionable statements that support the agency’s goals. This process is outlined in Figure 1 showing the subsequent steps of setting targets for the performance measures, allocating resources towards them, and then measuring and reporting the results. This is an iterative process if the project continues, where goals and objectives are then reconsidered.

Measuring performance is critical to not only determine the outcomes and effectiveness of a program, but also set benchmarks from historical data, unveil strengths and weaknesses in the program, and show areas of improvement (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2023). A common way to define and evaluate performance measures is to use the Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Time-bound (S.M.A.R.T) framework (United States Department of State, n.d.) & (University of California, 2016). This acronym stands for:

Specific: The performance measure is specific and clear about what it is assessing. It should be able to answer who or what the performance measure is assessing.

Measurable: There must be a source of information to measure to determine whether progress has been made. Data sources must be feasible to collect and can be quantitative or qualitative.

Achievable: The goal or targets for this performance measure should be attainable and motivational, not inherently discouraging.

Relevant: The measure’s focus should be aligned with the goal and objective(s) it is under.

Time-bound: Providing a time frame for the performance measure ensures there is a defined time to measure progress, and it provides a sense of urgency.

Performance Measure Typologies

Performance measures can be classified into several types, including process, output, and outcome measures (National Research Council, 2005). Process measures monitor project implementation by assessing the project’s activities and whether they are done according to a work plan or protocols (John Jay Research and Evaluation Center, n.d.). Process measures are often collected before, during, and after project

implementation (John Jay Research and Evaluation Center, n.d.). Output measures assess the end product, which is typically the number of products and services delivered during a specific period of a project (National Research Council, 2005). Outputs do not provide the results achieved or consequences of the services or products provided during a project. Instead, it provides information on what the project produced itself, or the scope or size of the project (United States Department of State, n.d.). Outcome measures assess the results of a project’s activities. These results are often the benefits sought by implementing a particular project. Part of determining outcomes is ensuring the results are due to the project, not external influences (National Research Council, 2005). Especially for large projects, outcome measures can be broken down into short, medium, and long-term outcomes. The long-term outcome, or end outcome, is the highest-level objective the project has been designed to achieve and that the program managers are willing to be held responsible (United States Department of State, n.d.). This process is graphically shown in Figure 2.

Source: Original Graphic

Classifying Performance Measures: Availability, Productivity, and Quality Measures

Performance measures can be classified into three categories: availability, productivity, and quality measures (Poulin & Kane, 2021). These categories were created in Poulin & Kane’s 2021 journal article focused on infrastructure resilience curves, where performance measures are the vertical axis of a resilience curve. Performance measures can assess system availability, system productivity, or service quality.

Availability measures quantify the capacity or aggregated functionality of a system and is typically expressed as a count with a higher number desired. An availability measure is used when interested in the infrastructure system itself, not the outcome or quality of the service provided. Examples include bridge loading capacity or number of cranes at seaport (Poulin & Kane, 2021).

Productivity measures focus on the quantity of the service provided by a system and is often expressed as a flow or rate, with higher values desired. These measures assess whether the service demand is met, as it is a function of supply, capacity, and demand. Productivity measures are most appropriate when service demand is expected to change within the scenario duration. Examples include flood volume relative to rainfall and water demand satisfied (Poulin & Kane, 2021).

Lastly, quality measures describe the character of service provided by an infrastructure system. These measures vary widely depending on what units they are expressed as since the measures are driven by the context of environment. Quality measures can provide a deeper look at performance which availability and productivity measures miss. Examples include average vehicle speed and water quality index (Poulin & Kane, 2021).

Summary: Performance measures (PMs) are critical to examining and understanding system effectiveness, importance and function, and are often dynamically created in order to align with the goals and objectives. There are various typologies of PMs which allow for researchers to evaluate process, outputs, and outcomes.

Gaps: PMs are utilized in many fields but are not interchangeable between disciplines. Their specific application must be customized to meet the goals and objectives of practitioners, policymakers, and the broader public. This has not been fully developed in the resilience space.

Relevance for Practice: Before being able to measure and evaluate resilience efforts, it is vital to define and understand the different types of performance measures including those that measure resilience. Understanding the different types of PMs will allow for better evaluation in a specific topic area.

Definition of a Transportation Resilience Performance Measure: A quantifiable indicator of service continuity that reflects one or more characteristics of transportation infrastructure’s ability to anticipate, prepare for, adapt to, withstand, respond to, and recovery rapidly from hazard impacts and other disruptions. It can be used to establish targets and assess progress toward achieving those targets.

Transportation Performance Management

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) defines TPM as a strategic approach that uses system information to make investment and policy decisions to achieve national performance goals (United States Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Adminstration, n.d.). Through this process, targets and goals are set to create a better-performing transportation system. The FWHA TPM Toolbox was created by FWHA to assist transportation agencies in implementing TPM practices through collaboration with MPO, State DOT, and transit agency members across the country. Through this process, targets and goals are set to create a better-performing transportation system. The following documents and tools were reviewed to evaluate best practices for the TPM process around the country:

- FWHA TPM Toolbox

- FWHA TPM Guidance

- NCHRP Report 708: A Guidebook for Sustainability Performance Management for Transportation Agencies

- Standing Committee on Performance Management (SCOPM) Task Force Findings on MAP-21 Performance Measure Target Setting

Strategic Direction

According to FWHA’s TPM Toolbox, the first step in the TPM process is establishing a long-term strategic direction for the agency. This means determining the goals, objectives, and performance measures.

Using frameworks such as the S.M.A.R.T can support the process of defining performance measures and serve as a tool to keep an agency’s objectives on course. Tracking of these performance measures is closely tied to the availability of data in the region. Performance measures should be measurable with the available tools/data, forecastable, clear to the public and lawmakers, and the agency should be able to influence the result (Federal Highway Administration, n.d.).

NCHRP Report 708: A Guidebook for Sustainability Performance Management for Transportation Agencies enumerates examples along with best practices involving the development of performance measures for sustainability (Zietsman et al. 2011). It outlines a six-step process for implementation:

- Step 1 – Understanding sustainability.

- Step 2 – Developing transportation sustainability goals. They recommend 11 goal areas.

- Step 3 – Developing objectives, which are specific actions to meet the goals. They categorize objectives into six possible focus areas of a transportation agency.

- Step 4 – Developing performance measures, which are based on output, outcome, or process measures.

- Step 5 – Implementing performance measures.

- Step 6 – Refining the framework and applying feedback.

Step 1 is particularly relevant to the initial stages of TPM because it enlists agencies to understand the breadth of the topic at hand, which can mature into a clear understanding of what needs to be accomplished. Best practices mention starting with a big-picture perspective, such as by defining a sustainable society and working from there to see how a transportation system fits in (Zietsman et al. 2011). Once the direction is set, then staff can begin to develop goals. Sustainability figures into several parts of a transportation pipeline, such as:

- Long-range planning: where expectations for sustainability performance can be discussed and goals can be established that drive investment patterns.

- Short-range programming: Where broad expectations and goals about sustainability are translated into explicit targets associated with implementation of specific projects.

- Project level – performance measures used to inform project-level planning decisions.

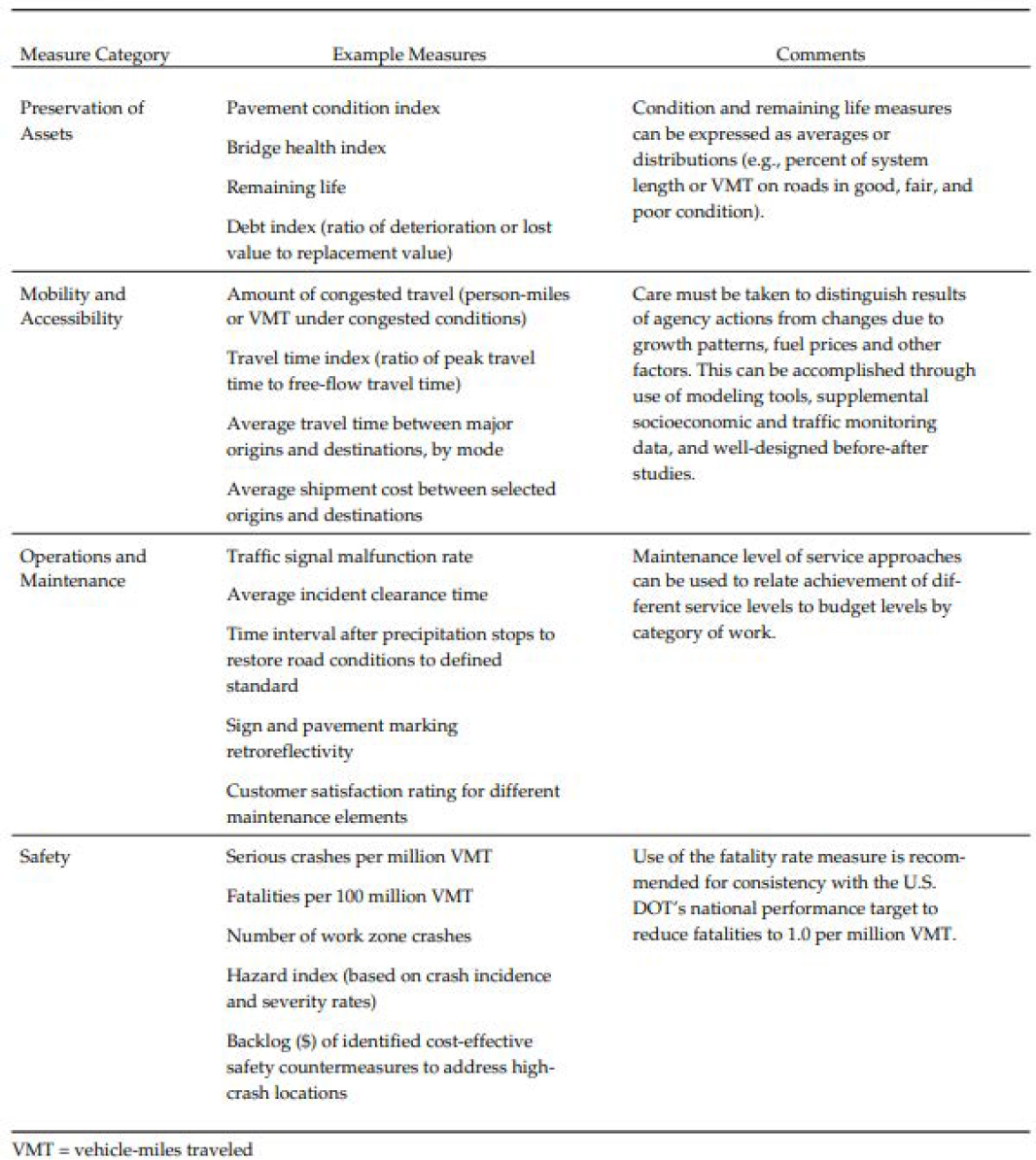

Figure 3 is an example framework for transportation agencies to conceptualize performance measures related to sustainability.

Source: (Zietsman et al. 2011).

To implement performance measures, the Guidebook recommends developing a description of the measures and associated actions and trend; introducing an evaluation to judge performance; identifying who is responsible and accountable; incorporating the performance measure into decision-support; and communicating about the performance measure to internal external stakeholders. They recommend the following steps for successful implementation, which are further elaborated within the following sections:

- Determine the appropriate scale of the performance measure.

- Determine appropriate application for each measure, goal, or focus area (target setting).

- Establish a reporting system and schedule with roles and responsibilities (tracking and reporting).

- Set benchmarks that are tracked to the factors that influence a performance measure.

Target Setting

The next step of the TPM Toolbox process is target setting. This step utilizes the previously decided goals, objectives, and performance measures to determine what specific quantifiable outcomes the agency wants to achieve. When target setting there are two subcomponents to consider, technical modeling and the business process (Federal Highway Administration, n.d.). The technical modeling component considers the historical, current, and project performance data to observe a baseline and evaluate performance trends in the data to establish the target. In the business process, agencies establish a collaborative process for internal

coordination to determine and change the performance targets over time (Federal Highway Administration, n.d.).

For federal long-range planning purposes, targets are established by the federal-aid highway funding recipients (MPOs or state DOTS) based on the regional data available for the measures in order to document future performance expectations. Targets should be logical, focused on data analysis and projections of future efforts (United States Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Adminstration, n.d.). These targets should be considered interim conditions that lead toward longer-term performance expectations. United States DOT still provides oversight of target setting and coordination even though it is the duty of the MPOs and state DOTs to set the targets.

Different states and municipalities will have different target values due to differences in funding levels, population growth, environmental conditions, and specific priorities (AASHTO, 2013). The AASHTO SCOPM Task Force on Performance Measure Development created a document to assist state DOTS and MPOs in setting targets related to the national performance measures. This document sets forth some recommendations for state DOTS and MPOs to choose their target values (AASHTO, 2013):

- Provide flexibility between different regions;

- Focus on long-term goals and better decision making based on customer and stakeholder requirements instead of a single target value;

- Align the target measures with system ownership and funding levels;

- Base target setting on longer-term trend data;

- Target setting should be attainable given the level of investment, DOTs and MPOs should only be accountable for what they manage and control;

- Analysis and reporting on the targets should be both qualitative and quantitative;

- Avoid unachievable targets with funding constraints factored into the process;

- Allow for appropriate timelines for target achievement, targets can be reevaluated and adjusted to reflect priority changes or new funding changes;

- Guard against unintended consequences such as neglecting long-term system needs;

- Provide a rationale for selecting specific target values, if the goals are not met, describe what has been done to improve performance; and

- Allow flexibility for DOTs and MPOs to use a risk-based target-setting approach.

Performance-Based Planning and LRTPs

After goals, objectives, performance measures, and specific targets are determined, the process of performance-based planning occurs to develop strategies and priorities in long-range transportation planning and other processes. Using the specific target determination for the chosen performance measures, strategy identification can occur to achieve desired outcomes through data trends, forecasting tools, economic analysis tools, and management systems (United States Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Adminstration, n.d.). Investment prioritization is then completed by evaluating tradeoffs across investment scenarios. These decisions should be grounded in performance data, strategic goals, and risk assessment (United States Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Adminstration, n.d.).

Using the strategies and priorities determined in the performance-based planning stage, performance-based programming guides the allocation of resources to achieve the agency’s goals, objectives, and performance measures (United States Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Adminstration,

n.d.). This process results in Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) documents and a State Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) to identify projects that will get funding, sources of the funding, and the time frame for implementation. Project selection criteria based on the performance measures can be utilized to screen projects. When programming projects across performance areas it is helpful to consider project scoring, prioritizing projects based on the value of the project per dollar spent, optimizing based on budget constraints, and conducting a trade-off analysis between investment scenarios to determine the impacts on all performance areas (United States Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Adminstration, n.d.).

Tracking and Reporting

An essential part of a TPM process is tracking and evaluating the actions taken and the outcomes that have been achieved from the TPM process. This allows officials to refine or modify the previously determined planning, programming, and target-setting determination. At the system level of monitoring and adjustment, resource allocation decisions are compared to the achievement of the agency’s goals and objectives. At the program/project level, specific programs and projects are assessed. Once the monitoring framework has been established, agencies can regularly assess the results and adjust. This creates a feedback loop for targets, measures, goals, and future programming decisions (United States Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Adminstration, n.d.)

In the federal long-range transportation process, states and MPOs must develop reports that document progress toward target achievement, including the effectiveness of federal-aid highway investments. All states must submit reports on progress toward target achievement for each performance measure (United States Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Adminstration, n.d.)

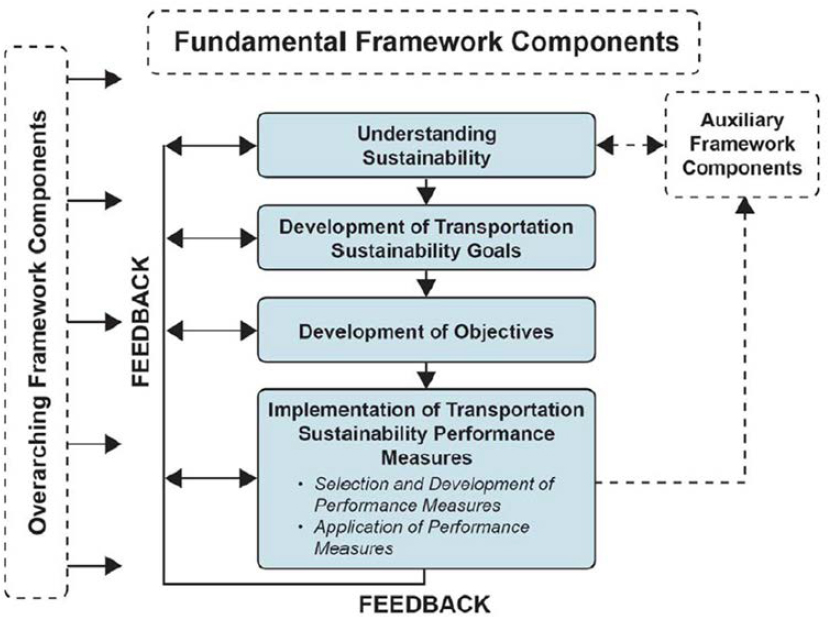

Performance Measures Supporting Agency Objectives

FHWA has established measures to assess performance/condition in carrying out performance-based federal-aid highway programs. There are three different performance measure categories: Safety (PM 1), Pavement and Bridge Condition Measures (PM 2), and Performance of National Highway System, Freight, and CMAQ Measures (PM 3). For each category, specific performance measures have been established that agencies must include in their TPM process, shown in Table 2.

Table 2 FHWA Performance Measures

| Category | Performance Measures |

|---|---|

| Safety | Number of fatalities |

| Rate of fatalities | |

| Number of serious injuries | |

| Rate of serious injuries | |

| Number of non-motorized fatalities and non-motorized serious injuries | |

| Infrastructure | Percentage of pavements of the Interstate system in good condition |

| Percentage of pavements of the Interstate system in Poor condition | |

| Percentage of pavements of the non-Interstate National Highway System | |

| (NHS) in good condition |

| Category | Performance Measures |

|---|---|

| Percentage of pavements of the non-Interstate NHS in Poor condition | |

| Percentage of NHS bridges classified as in Good condition | |

| Percentage of NHS bridges classified as in Poor condition | |

| Performance of NHS, Freight, and CMAQ Measures | Percent of the person-miles traveled on the Interstate that are reliable |

| Percent of the person-miles traveled on the non-Interstate NHS that are reliable | |

| Truck Travel Time Reliability Index | |

| Annual Hours of Peak Hour Excessive Delay Per Capita | |

| Percent of Non-SOV travel | |

| Total Emissions Reduction |

Source: (United States Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Administration, n.d.)

Factors for Success and Lessons Learned

Building on years of TPM, the FHWA TPM Toolbox offers practitioners best practices on how to implement and self-assess transportation performance management. TPM provides critical information to support decision making across systems and improves communication between decision makers, stakeholders, and system users, while guaranteeing targets and measures are co-created with partners and based on quality data and information (United States Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Adminstration, n.d.). The TPM Toolbox outlines examples of performance measures FHWA uses (Table 2) for various areas of system management, which can inform practitioners on how to integrate resilience outcomes and objectives into an assessable metric that better informs investments and success.

From the outset of the TPM process established by USDOT rulemakings consistent with the provisions of MAP-21 and the FAST Act, state DOTs, MPOs, and transit providers first had to establish new governance frameworks establishing roles and responsibilities for different subdivisions of their agency. In some cases, agencies created new organization structures to facilitate the TPM process and established new agency policy and guidance to help institutionalize implementation. This helped the organization to implement a new process and establish accountability for meeting schedule milestones and requirements.

Based on the past decade of TPM implementation, there are several factors that help make programs successful, including a clear data governance plan and buy-in from agency leadership. To meet the TPM requirements, development of a governance plan is essential to success, particularly in agencies where multiple agency divisions or offices will be involved. These governance plans typically enumerate who has ownership of the data, who is responsible for the analysis, who/what processes makes recommendations and adopt targets, and how findings are integrated into parallel agency planning and programming efforts. As discussed later in this document in the Implementation section, governance plans identify someone within an organization (a leader or someone with influence and authority) to oversee the TPM process across business lines and divisions. As described later, this is often where the TPM process faces implementation challenges. TPM requires a commitment to rigorous data collection, analysis, and presentation, which if it occurs in isolation from other agency activities, limits its ability to provide meaningful value into decision making.

Agencies are also elevating performance management within agency mission statements, strategic plans, and long-range plans by describing exactly where they connect to planning and programming processes. In some cases, these connections are practical and required, such as through the inclusion of a System Performance Report as part of a state LRTP or MPO metropolitan transportation plan, and references to

performance trends and targets within STIPs and MPO TIPs. In other cases, agencies are identifying performance management as part of an overall transportation management cycle of planning, programming, and performance management, as depicted in recent statewide long-range plans and associated performance management efforts.

It can be a challenge to link performance management to planning and programming because of the need to address the gap between data-supported decisions and data-driven decisions. Specific performance measures may be difficult to track and show progress against because a baseline cannot be developed using existing data. In these cases, data centralization and management alongside organizational culture/leadership to drive progress are challenges to establishing successful performance measures and targets. One way of combatting this is by creating iterative processes that can be flexible based off availability and development of data, staff, and agency priorities.

NCHRP Report 666: Target-Setting Methods and Data Management to Support Performance-Based Resource Allocation by Transportation Agencies, Volume I: Research Report, and Volume II: Guide for Target Setting and Data Management discusses the several success factors needed for effective data management and execution of planning efforts (Cambridge Systematics Inc. et al. 2010). The key factors vary, but all center on establishing a need and demonstrating a return on investment to the organization to gain buy-in from decision makers. Thus, a linkage between data and goals and targets needs to be formalized via a business plan or a system that connects an agency’s mission with staff effort. This function of “making the case” is accomplished through processes such as an existing conditions assessment of data systems, including data availability and needs.

Investing in staff trainings and leveraging access to other planning offices (regional or district) and technical resources available to the agency can also lead to successful TPM programs. Additionally, placing performance measures in a hierarchical order allows an agency to translate strategic goals/objectives into operational goals/objectives for each department. The US DOT models this approach among its different administrations (e.g., FHWA and FTA), providing a performance budget that can be related to actual and planned accomplishments for each department. This same setup would apply to a State DOT with multiple divisions, districts, or independent offices. The performance in each area becomes an indicator for resource allocation and budgeting. Finally, rewarding divisions which meet targets and goals incentivize and motivate staff. These all strongly enhance a performance-based management process.

Summary: Federal resources such as the TPM Toolbox offer guidance for state and local practitioners to understand best practices and offers a deep dive into their historical development and agency outcomes. TPM begins with establishing a long-term strategic direction, re-examining targets and goals, and building a performance-based planning frameworks to better inform strategies in LRTPs and develop more rigorous investment prioritization schemes.

Gaps: In absence of strong governance and leadership, TPM can be difficult to successfully implement given the variety of data owners, decision makers, and stakeholders that need to be involved. Additionally, the TPMs related to safety, infrastructure and Performance of National Highway System, Freight, and CMAQ Measures do not include incorporating risk from probable events into the forecasting of these measures. For example, travel time reliability is at risk on the I-70 corridor in Colorado due to weeks long closures from rockfall/rockslide events outside of Glenwood Canyon. This underlying risk to system resilience and travel time reliability is not accounted for in performance measures.

Relevance for Practice: Agencies may not be fully accounting for the underlying risks to their ability to meet their established performance measures – meaning they are not accounting for the probability of extreme weather events to impede their ability to reach their performance goals.

Measuring Resilience

Resilience in the transportation system of the United States is essential to recover from natural disasters and adverse events (Special Report 340, 2021). An important step in implementing resilience into transportation planning is measuring the resilience of the transportation system to track progress and evaluate appropriate transportation investments. The report Disaster Resilience: A National Imperative (National Research Council 2012) outlines several important aspects of an effective resilience measurement system:

- Indicators of the ability of critical infrastructure to recover rapidly from impacts;

- Social factors that enhance or limit a community’s ability to recover, including social capital, language, health, and socioeconomic status;

- Indicators of the ability of buildings and other structures to withstand natural disasters; and

- Factors that capture the special needs of individuals and groups, related to minority status, mobility, or health status.

The following tables (Table 3, 4, 5, and 6) summarizes the index, models, metrics, and tools that have been used around the United States to measure/evaluate resiliency. Though these resources have advanced the transportation field’s ability to measure resilience, none are a panacea that are seen as a consensus approach in the field. Many of these resources lack a robust approach to incorporating future event projections or providing specific impacts that hazards have on transportation assets and systems.

| Model Name | Brief Summary |

|---|---|

| San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR) Model | This model was developed for measuring resilience concerning earthquakes. It looks at predicted recovery time frames based on the current status of the asset compared to the desired target state of recovery. A comprehensive table is created rather than a single metric. |

| Norris et al. (2008) community resilience model | This model of community resilience looks at the economic and social capacities of communities utilizing publicly assessable population indicators. |

| RAMCAP model | This model quantitatively assesses infrastructure risks by requiring a “threat scenario” to be developed for the model to analyze. The model evaluates risk based on the “worst reasonable consequence” resulting from damage to the transportation infrastructure and is calculated by multiplying threat probability, vulnerability, and consequences. The threat probability is if the asset will be affected by the scenario, the vulnerability is the probability the asset will be damaged or destroyed, and the consequences are the cost to the community from the scenario. |

| Resilience and Disaster Recovery Metamodel | This model allows agencies to compare the costs of different hazard scenarios to the costs of potential hazard mitigation. This model uses hazard probabilities, the vulnerability of infrastructure assets, and the consequences of damages to infrastructure. This resiliency model can be used with travel demand models. |

Sources: (National Research Council, 2012), Special Report 340, 2021)

| Index Name | Brief Summary |

|---|---|

| Coastal Resilience Index |

This metric combines the following:

|

| Argonne National Laboratory Resilience Index | The metric is determined for critical infrastructure facilities and is created from interviews at critical infrastructure facilities that cover around 1,500 variables. This data is then combined into a single resilience index for each of the critical infrastructure assets. This metric was created as part of a national program. |

| Social Vulnerability Index (SoVI) | This metric is statistically driven, utilizes census data, and helps to illustrate the capacity for preparedness, response, and recovery in different communities. |

| Resilience Capacity Index (RCI) | This metric provides a single regional statistic that combines 12 economic, socio-demographic, and community connectivity indicators that influence the ability of a region to come back from a hazard event. |

| Community Disaster Resilience Index (CDRI) | This metric is determined using the four phases of disaster management (preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation) and combines them with community capital assets (social, economic, physical, human, and natural capital). Scores were then averaged for each of the capital assets to compute the CDRI. |

| Center for Risk and Economic Analysis of Terrorism Events Economic Resilience Index (CREATE-ERI) | The goal of this index is to evaluate the risks, costs, and consequences of terrorism and to guide investments. This metric is evaluated by the avoided losses divided by maximum potential losses in terms of direct and indirect business interruption losses. |

| Index Name | Brief Summary |

|---|---|

| Vulnerability Index | Used to express the susceptibility of the critical components of a transportation network and commonly represents the operational performance of the network. |

| Accessibility Index | This metric helps to determine the relative importance of highway links after a disaster event. |

Sources: (Ahmed & Dey, 2020), (National Research Council, 2012)

Table 5 Resiliency Metrics/Measures

| Metrics/Measures | Brief Summary |

|---|---|

| Baseline Resilience Indicator for Communities | This metric is calculated by the arithmetic mean of five sub-indexes related to social, economic, institutional, infrastructural, and community resilience. |

| Vulnerability/Sensitivity | The likelihood of damage or disruption to an asset due to a hazard event. The vulnerability of an asset can be reduced by increasing the robustness of the asset or by relocating it. |

| Consequences | Measures of the direct and indirect impacts of the damage or disruption to the transportation system. This metric could measure the cost to repair the asset or the death or injury of travelers on the transportation asset. |

| Risk | This metric often considers the likelihood of a hazardous event, the vulnerability of the asset, and the social and economic consequences of the damage. |

| Criticality | This metric measures the importance of the transportation asset and often involves community input as it measures a broader economic and social impact than consequences do. This metric is often used with vulnerability to assess and prioritize resilience investments. |

| Availability | The measure indicates the capacity or functionality of a transportation system. An example of a measure of availability would be transportation system capacity. |

| Productivity | This metric is the quantity of service provided by the system. Productivity is often measured with regard to rate or flow and is typically a function of supply, capacity, and demand. |

| Quality | The quality of a system is the character or service provided by the system. Examples of the quality of a transportation system would be the average vehicle speed or the transportation travel time. |

| Travel Time | The time spent traveling from trip origin to destination. This time may fluctuate due to features of the transportation system and meteorological conditions during a disaster scenario. |

| Reliability |

The probability of the asset being functional/operational post-disaster. Reliability related to the transportation system can be split into three different groups (Ahmed, 2020):

|

| Restoration Time | Amount of time to restore the transportation system post-disaster. The goal of many agencies is to restore the system in order to operate relief distribution and post-disaster evacuation. Models have been created to optimize the restoration process. |

| Travel Demand | This metric looks at the travel demand before the disaster and after the disaster. |

| Cost or Budget | The cost is related to the system disruption due to the disaster. These costs could include travel time cost, fuel cost, and restoration costs. |

| Capacity | This metric is determined by how long a system can survive on its own after the occurrence of any disruptive event. |

| Shortest Path | This metric determines the most efficient route. This can be used to quantify the alternative routes in case of post-disaster routing. |

| Resilience Triangle | This metric is a combination of three different parameters to measure resilience. The parameters are the performance loss of the system, time to reach the lowest level of performance, and recovery time. |

| Absorptive Capacity | The ability of the transportation system to absorb shocks and stresses and maintain normal functioning. Some example inputs are the mileage of new facilities in flood zones and the number of highway lanes and centerline miles within a 100-year floodplain. |

| Restorative Capacity | The ability of the system to recover quickly after a shock or stress to normal functioning. Example input metrics are counts of construction equipment or workers in the region or the budget for snow removal, fire suppression, cyber system protection, or other hazards. |

| Equitable Access | The ability of the system to provide the opportunity for access across the entire community during a shock or stress and when the system is undisrupted. Sample input metrics for determining the adaptive capacity of a transportation system include the distance to alternative routes or the number of reliable routes. |

| Adaptive Capacity | The ability of the system to change in response to shocks and stresses to maintain normal functioning. Sample input metrics for determining the adaptive capacity of a transportation system include the distance to alternative routes or the number of reliable routes. |

Sources: (Ahmed & Dey, 2020), (Special Report 340, 2021), (National Research Council, 2012), (Poulin & Kane, 2021) and (Weilant, S., Strong, A., & Miller, B. M., 2019)

| Tool Name | Brief Summary |

|---|---|

| FWHA’s Vulnerability Assessment Scoring Tool (VAST) | This tool helps determine the likely physical damage or disruption is an infrastructure asset from an event. This tool has indicators for exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity (or redundancy). |

| Hazus-MH | A tool created by the Federal Emergency Management Agency that estimates the impacts of natural hazards. The tool produces quantitative estimates of the impacts of hazard events. The tool is able to analyze the cost-effectiveness of common mitigation strategies but has limitations when it comes to smaller mitigation actions. |

| Community Assessment of Resilience Tool (CART) | This tool is a community intervention that includes a survey, a focus group script, and a process for assessing and building community resilience to disasters. The results help to develop a profile for the community to measure and enhance community resilience. |

| Community Resilience System (CRS) |

The goal of this system is to achieve more resilient communities. This system has six steps (National Research Council 2012):

|

| Toolkit for Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments (T*H*R*I*V*E) | This resource provides communities with a means to improve health outcomes and reduce disparities experienced by racial and ethnic minorities. |

Sources: (Special Report 340, 2021) and (National Research Council, 2012)

In addition to the metrics, indices, and models, design guides can help make resilience part of the planning process for transportation agencies. These guides may reduce the need to conduct resilience analysis on a project-by-project basis. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, and New York City have design guides that look at hazard probability, asset useful life, and criticality of a transportation system (Special Report 340, 2021).

Examples of RPMs

RPMs are performance measures used to measure the resilience of a system. In the context of this project, that means the ability of the highway system to anticipate, prepare for, and adapt to changing conditions and withstand, respond to, and recover rapidly from disruptions. In Integrating Resilience into the Transportation Planning Process: White Paper on Literature Review Findings (2018), a literature review was completed on planning documents from 52 DOTs and 101 MPOs to evaluate the current state of the practice for integrating resilience into the planning process. Out of the reviewed DOTs and MPOs, five DOTs and 19 MPOs had performance measures, targets, or evaluation criteria (Dix, B., Zgoda, B., Vargo, A., Heitsch, S., & Gestwick, T., 2018). The resiliency performance measures from the state and MPO plans are listed below, split into six different categories.

Flood Related

- Mileage of new facilities in flood zones

- Protect low-lying major roads from storm surge and flooding

- Development in high flood risk areas: Employment and housing in Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) 100-Year floodplains

- Number of highway lane and centerline miles within the 100-year floodplain

Forest Fire Related

- Development in forest fire risk areas: Employment and housing in wildland-urban intermix areas

Sea Level Rise/Natural Hazard Variability Related

- Number of projects that raise the roadway grade or increase resilience against natural hazard variability or natural disasters through other means (tracked annually)

- Increase the percentage of facilities that accommodate two feet sea level rise; the performance target is 90% for the strategic intermodal system network in 2025

- Evaluate potential impacts of sea level rise for all TIP projects during the 25% design review and adjustments to projects are made as warranted

- Number of coastal communities with adaptation plans

Stormwater Related

- Maintain stormwater drainage programs

- Number of stormwater improvement projects implemented by local communities and MassDOT

- Provide improved stormwater management and treatment to 50% of TIP projects outside of sensitive areas and 100% of TIP projects within sensitive areas

Infrastructure Related

- Reduce the percentage of roadways in “poor” or “fair” condition

- Reduce the percentage of roadways in “critical backlog”

- Annual percentage of routine culvert inspections completed on time

Other

- Percent of compliance on erosion and sediment control ratings

- Acres of wetlands or wildlife habitat created, restored, or improved since 2000

- Ensure 95% of all roadways have a volume-capacity ratio less than one by 2020

- Reduce commute times by 2.5% by 2025

In A Guidebook for Sustainability Performance Measurement for Transportation Agencies (2011), one of the main goals outlined was security – ensuring that the transportation system is secure from, ready for, and resilient to threats from all hazards (Zietsman et al. 2011). Some of the performance measures outlined for this security goal can be translated into measuring resilience, outlined below:

- Level or redundancy for critical passenger and freight infrastructure

- The capacity of parallel/redundant routes across all modes and major freight corridors

- The number/value of projects as part of a program to protect transportation users, agency personnel, and critical infrastructure

- The number/value of projects designed to improve the capacity of the transportation system to recover swiftly from incidents

- The number/value of projects as part of a program designed to enhance the security of freight transportation assets

- Relative change in capital funding allocated to disaster/incident response and management

- Incident clearance time for selected incidents

Monetizing Annual Risk to Highway Assets

In a special report from the Transportation Research Board, Investing in Transportation Resilience: A Framework for Informed Choices (2021), two examples from DOTs were presented to summarize how the RAMCAP model was used to determine risks and the resulting cost to transportation assets from natural disasters.

The Colorado DOT utilizes the RAMCAP model to identify the monetary risk for rockfalls, floods, and debris flows after a fire. In order to calculate the threat probability, they use historical data to determine the estimated frequency and magnitude of the hazard events. In determining vulnerability, the Colorado DOT used the physical characteristics of the asset and research, data, and expert advice to determine the probability of the “worse reasonable case” occurring (Special Report 340, 2021). The consequences to the owners of the asset were the costs of transportation asset replacement and cleanup after the event while the consequences for the users were related to how many closure days. The cost per mile and hour was then calculated using a traffic model to determine the detours drivers need to take. In order to measure resilience, the annual calculated risk is then compared against the criticality scores using a matrix. The Colorado DOT measures criticality by combining six different variables: average annual daily traffic, functional classification, system redundancy, freight value, tourism dollars, and the SoVI. All of these metrics are ranked from one to five and summed with equal weighting (Special Report 340, 2021).

The Utah DOT also uses the RAMCAP model but follows a separate process from Colorado DOT. Utah uses the probability of a hazard great enough to cause total failure of the asset, so “vulnerability” is not included to calculate the risk (Special Report 340, 2021). They utilize the change in sensitivity, which they define as “a measure of how much damage will occur” to determine the benefits of investments (Special

Report 340, 2021). Utah uses highway-related factors like redundancy, average annual daily traffic, and truck traffic to evaluate criticality. The measure of resilience is determined by one divided by the product of risk and criticality. To evaluate the consequences, the Utah DOT uses owner costs (like repair costs) and user costs (Special Report 340, 2021).

Developing RPMs

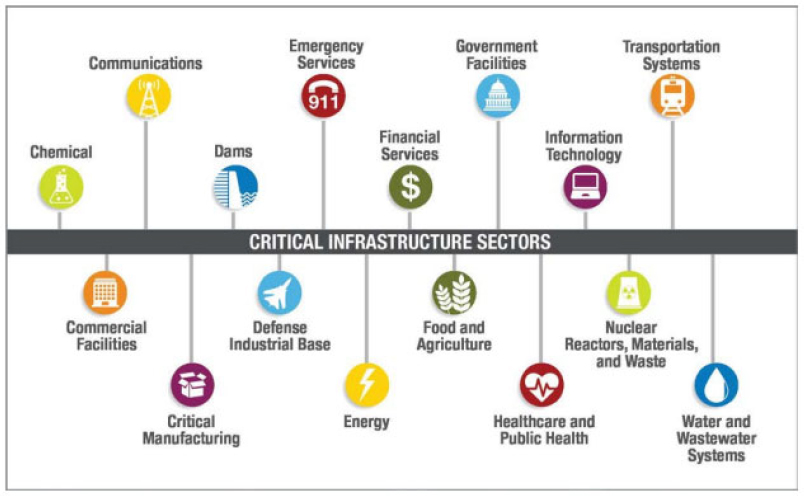

Critical infrastructure can be defined as sectors “whose assets, systems, and networks, whether physical or virtual, are considered so vital to the United States that their incapacitation or destruction would have a debilitating effect on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination thereof” (Cybersecurity & Insfrastructure Security Agency (CISA), 2023). Presidential Policy Directive 21 (PPD-21) identifies 16 critical infrastructure sectors as presented in Figure 4 (Department of Homeland Security (DHS), 2016). Resilience has been a consideration factor at various levels of critical infrastructure sectors, and to protect the future of transportation assets, it is key to identify lessons learned from the work done in other critical infrastructure sectors. The approaches vary in maturity by sector, from the early stages of identifying factors considered as resilience in some sectors, to the development and establishment of risk and resilience standards by the water/wastewater sector. Resilience metrics are essential to support the decision-making process.

Critical Infrastructure Sectors

Water/Wastewater

The water/wastewater industry has developed risk and resilience methodologies that have been widely adopted and applied in their industry. The American Water Works Association (AWWA) developed its Risk and Resilience Management of Water and Wastewater System Standard (ANSI/AWWA J100-21) (American Water Works Association (AWWA), 2021) based on the Risk Analysis and Management for Critical Asset Protection (RAMCAP Plus) framework (American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) Innovative Technology Institute, LLC, 2010). As part of the J100 standard, the water sector measures risk as a monetary value based on the probability of the hazard/threat event, the vulnerability of the asset and the potential consequences to experience negative impacts. The annual monetary risk to an asset from a threat/hazard is calculated using the equation below:

Risk ($) = Threat/hazards probability (%) x Vulnerability (%) x Consequences ($)

In addition, J-100 also provides a process to estimate the resilience of utilities based on the Utility Resilience Index (URI). The URI is a relative measure that represents the ability of the water/wastewater utility and the community it serves to absorb and recover from the impact of a natural disaster. The URI is based on a score between 0 to 100% and is based on a series of operational and financial indicators as shown in Figure 5 below. The operational indicators reflect the utility’s tactical capacity to react quickly and/or cope with various incidents that have the potential to disrupt service, while the financial indicators reflect the utility’s fiscal capacity to react quickly and/or cope with various incidents that have the potential to disrupt revenue and costs. The sub-indicators have different weights with corresponding scores that are added up to generate the final URI for the utility. This format allows for the quick identification of enhancements to the system’s resilience by determining the next level of operational and financial resilience achievable based on the sub-indicators.

Energy

In 2015, RAND Corporation conducted a literature review to identify the different approaches to measure resilience of energy distribution systems (Willis & Loa, 2015). The report divided the metrics in five different categories: inputs, capacities, capabilities, performance, and outcomes. Table 7 presents an example of the resilience metrics used in the energy sector.

Table 7 Example of Energy Resilience Metrics for Electricity Systems at the Facility/System Level

Source: (Willis & Loa, 2015)

The report resulted in three recommendations to improve the development and collection of resilience metrics to support energy policy, which include:

- Improve Collection and Management of Data on Inputs and Capacities at the Facility and System Levels;

- Develop Better Measures of Capabilities at the System and Regional Levels; and

- Improve Understanding of How Capabilities and Performance Translate to Outcomes at the Regional and National Levels.

Similarly, the Department of Energy (DOE) highlights that resilience can be quantified through temporally explicit performance-based indicators (e.g., comparing baseline and investment scenarios). Table 8 presents some examples from the DOE of resilience metrics used in the energy sector based on the expected direct and indirect consequences from losing service (Sandia National Laboratories, 2017).

Table 8 Examples of Grid Resilience Metrics for Consequence Categories

Source: (Sandia National Laboratories, 2017)

In addition to the metrics presented above, other metrics have been used in the energy sector including engineering-designed, operational, and community resilience metrics as presented in Table 9 (Shandiz, Foliente, Rismanchi, Wachtel, & Jeffers, 2020).

Table 9 Examples of Resilience Metrics by Type of Resilience

| Resilience Type | Metrics |

|---|---|

| Engineering-designed | The rate of disturbance (number of lines tripped per hour and number of lines tripped) The duration of the performance disruption (hours) The rate of system recovery (number of lines restored) |

| Operational | The rate of disturbance (kW power loss per hour and power capacity loss) The duration of the performance disruption (hours) The rate of system recovery (kW power restored) |

| Community | Amount of time-critical community functions (e.g. energy services) were adequately provided to people, divided by total amount of disruption time |

Source: (Shandiz, Foliente, Rismanchi, Wachtel, & Jeffers, 2020)

Cybersecurity and Information Technology (IT)

Risks that impact the cybersecurity and IT sectors continue to grow. Many companies are investing in new technology and procedures to reduce risk and improve the resilience of their systems. In the IT sector, resilience targets are typically measured by two metrics: Recovery Time Objective (RTO), “the time it takes to recover from a failure”, and Recovery Point Objective (RPO), “the maximum window of time in which data might be lost after an incident” (Amazon Web Services (AWS), 2021).

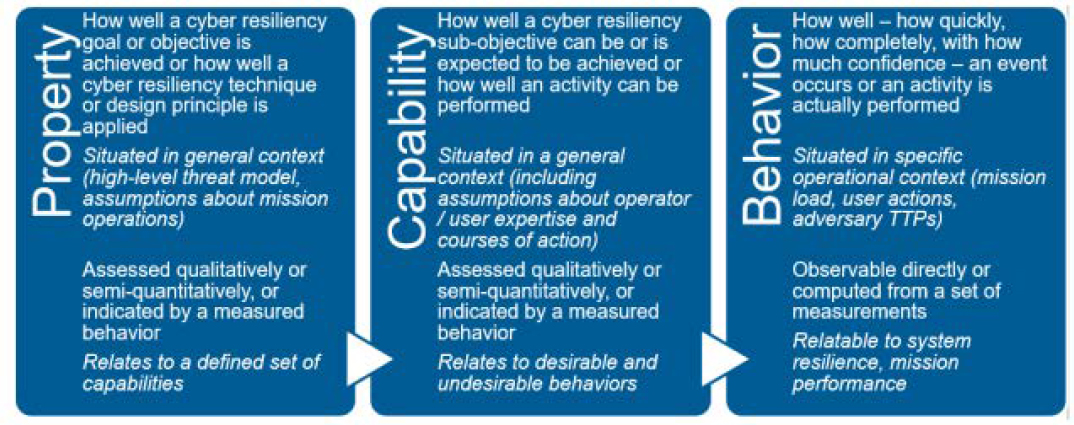

Cyber resilience is an area that has gained heightened attention due to the increase of events experienced in recent years. A report published in 2018 by MITRE (Bodeau, Graubart, McQuaid, & Woodill, 2018), presents an overview of cyber resilience metrics, measures of effectiveness and associated scoring. The report describes the three aspects of resilience to be assessed, including property, capability and behavior as presented in Figure 6.

In addition to the assessable or measurable aspects of cyber resilience, the report highlights the way security metrics, resilience metrics, and risk metrics can be repurposed into cyber resiliency metrics as shown below in Figure 7.

International Experience

Internationally, there has been significant work done in the area of resilience, transportation, and performance measurement. This section reviews several examples, including global initiatives from the United Nations, two European Union projects, an example from Norway, and a performance measurement approach from the United Kingdom.

The United Nations, to track global development on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), has developed trackers to measure progress on 232 unique indicators (Roser & Mispy, 2018) to be achieved by the year 2030. The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe has developed a framework for measuring and monitoring progress towards SDGs, which documents the challenges in coordination and collaboration for data collection, dissemination and communication of status of progress and development of standard data exchange formats.

The Inter-American Development Bank led the development of a resilience metrics framework for the multilateral development banks (MDBs) and members of the International Development Finance Club to align financing flows with the resilience goals of the Paris Agreement (Inter-American Development Bank, 2019). The framework discusses the use of various types of metrics by the MDBs and financial institutions – including input, output, outcome, and hybrid metrics at the project/asset and system levels. One example transportation project-level outcome metric used by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD)“estimated 2.3 days per year of avoided weather-related disruption to the relevant section of the road network and increased road lifespan of 5 years compared to the pre-project baseline” expressed as a physical outcome, which can also be monetized/valorized savings (€1.7 million annually).

The FORESEE project, of the European Union, sought to develop, demonstrate, and verify a set of dependable and implementable tools to provide immediate and long-term resilience measures against extreme weather events. To do that, the report examined the integration of concepts of resilience and level of service in infrastructure governance. This report concluded that resilience and service level should be included in governance throughout the lifecycle of an asset, bolstering the current framework in which public infrastructure is governed. Resilience is not seen as a single outcome or a post-disaster recovery measure, but rather as a dynamic process that uses a risk and lifecycle-based method for addressing the vulnerabilities of critical infrastructure systems, making systems better able to adapt to unexpected challenges (Adey, Martani, & Kielhauser, 2019). Likewise, the FORESEE project provided guidelines on measuring levels of service and resilience infrastructure and setting target levels. These were developed into the CEN publication CWA 17819:2021: “Guidelines for the assessment of resilience of transport infrastructure to potentially disruptive events,” which forms the initial foundation for a European Standard on resilience assessment for transport infrastructure (de Jonge, van Marle, Connolly, de Paor, & Bles, 2022).

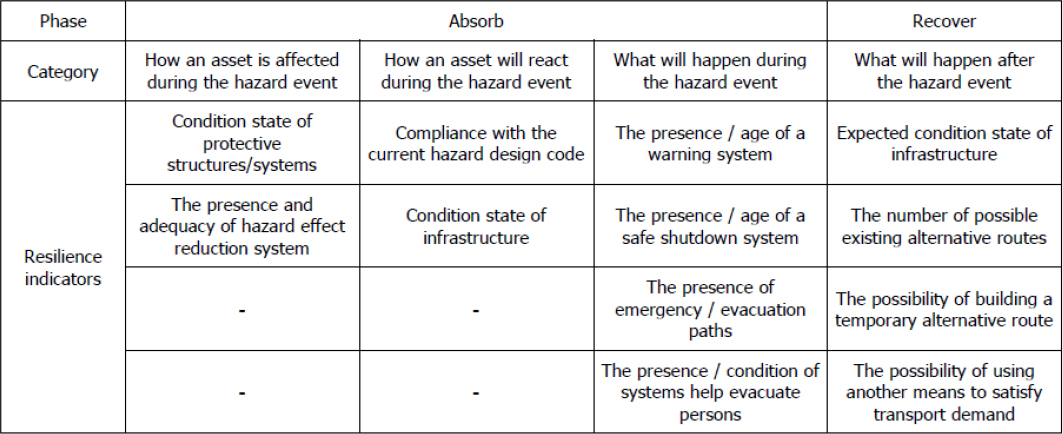

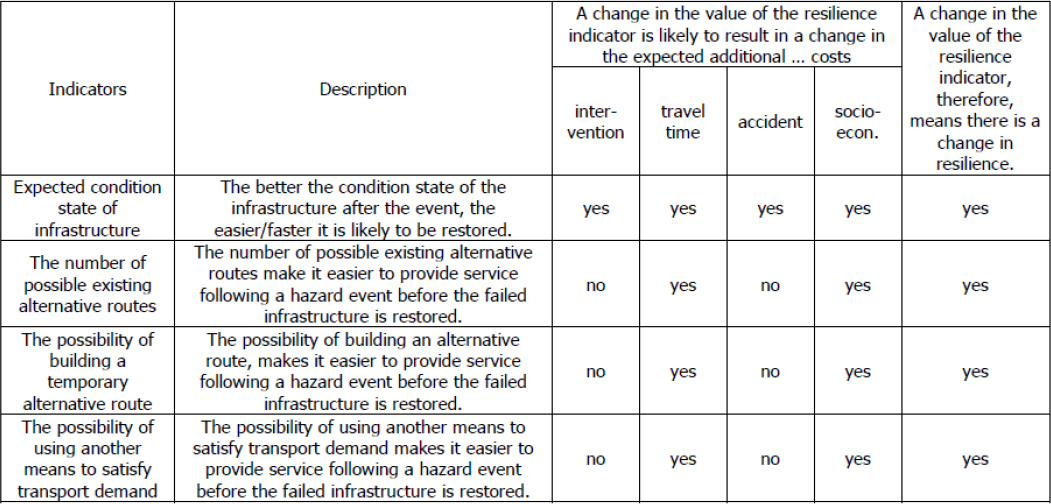

Measuring resilience requires measuring the difference between the service over time, when no events occur compared to when a hazard event occurs. It is more difficult than measuring service because it requires an estimation of what will happen between those two events. This depends on factors like preparedness, reactions, and responsiveness. Due to this obscurity, FORESEE believes it is more valuable to use resilience indictors, i.e. indicators of how service will be impacted, in order to capture performance. Measuring resilience often requires the proper selection of relevant indicators and the development of categories of indicators at successive levels (modeling the phases of the resilience curve). Figure 8 provides snapshots of generic resilience indicators related to infrastructure (Adey, Martani, & Kielhauser, 2019). Figure 9 and Figure 10 show generic indicators of what will happen during and after a hazard event.

Source: (Adey, Martani, & Kielhauser, 2019).

The ICARUS project, another European Union initiative, sets out to improve the uptake of resilience adaptation in roadway decision making. ICARUS examines service level metrics versus resilience indicators. Service level metrics are understood as availability, environmental effects, political impacts, and design criteria. On an asset level, service level metrics are documented and implemented through design, however, the connection to natural hazard variability is lacking. Much of current resilience adaptation considers the application of minimum service levels. This is seen through the application of cost-benefit analysis, response curves etc. for the setting of service level metrics. These are often delineated as resilience metrics. CEN CWA 17819 is a notable example of applying service levels to resilience adaptation, which may be the industry standard in the coming years. (de Jonge, van Marle, Connolly, de Paor, & Bles, 2022).

Despite service level targets being uncertain, Transport Infrastructure Ireland annually reports a summary of key performance indicators (PINs) of the national road network in Ireland in their “National Roads Network Indicators” reports. Metrics used to determine service include traffic flow rates and level of service, AADT, journey time reliability, and incident data including duration and average response time. Metrics on pavement condition, bridge condition, and safety data, including numbers of fatalities and injuries, are all recorded. In the Netherlands, there is a service level agreement that includes PINs. PINs are expressed at the network level in terms of availability of the road and safety for the road user. Performance of the road network is monitored per region and summarized for the network. Through avenues like criticality assessments, the Dutch categorize the road network into four categories (A-D) based on traffic intensity, redundancy and economic significance, to allow for tailored measures based on need (de Jonge, van Marle, Connolly, de Paor, & Bles, 2022).

Overall, ICARUS concluded that while service level metrics exist, they are utilized more for examining the past or present performance of infrastructure and are not used to evaluate and project the resilience of infrastructure against future climatic disruption. Due to ease in data acquisition, wider knowledge or awareness of service levels at the asset level was seen. However, there needs to be a deeper understanding

of how existing indicators can be used to address natural hazard variability (de Jonge, van Marle, Connolly, de Paor, & Bles, 2022).

Another international example is the Norwegian Public Roads Administration (NPRA), the public construction authority responsible for the planning, construction and management of highways and county roads. The main challenges for the Norwegian road network come from the expected increase in precipitation and subsequent consequences. There are four important pillars of all aspects of the NPRA’s work, including the National Transport Plan (NTP), the Norwegian Road Database (NRDB), the NPRA’s own design and practice manuals, and networks of information sharing among national and international peers. Based off decades of work, the group has developed a ‘framework’ for adaptation (Petkovic, G., Kristensen, L., Dolva, B, 2019).

The Norwegian framework guides road authorities through the process of increasing the of their networks and assets through four stages:

- Identifying scope, variables, risks and data (Stage 1);

- Assessing and prioritizing risks (Stage 2);

- Developing and selecting adaptation responses and strategies (Stage 3);

- Integrating findings into decision-making processes (Stage 4).

For NPRA, Stage 1 includes vulnerability analysis on a general level and on the road network level. This happens annually via vulnerability mapping using the VegRos method for risk assessment, a methodology used for the regular and obligatory risk assessment that is performed annually on all national roads. Stage 2 involves scoring elements of risk and prioritizing measures, also via the VegRos methodology. Stage 3 entails amendments to design guidelines and vulnerability mapping in planning and operation contracts. Notably, NPRA decided that resilience should be included in the NTP and not solely in a dedicated adaptation strategy. On the asset/road level, improvements are necessary to include economic analyses in decisions concerning the choice of adaptation measures. The final, Stage 4, formalizes the assessments by making a business case for adaptation (Petkovic, G., Kristensen, L., Dolva, B, 2019).

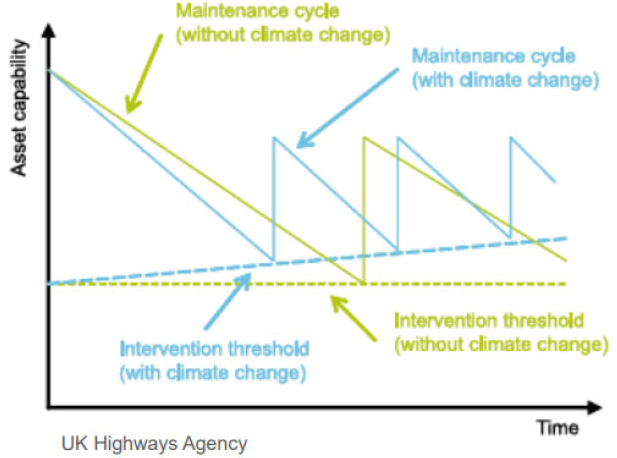

Finally, in the United Kingdom, Roads: An industry guide to enhancing resilience discusses how the Department of Transport’s metrics or performance measures can create strategic goals, instill accountability, and incentivize action (Reeves, Winter, Leal, & Hewitt, 2019). Two examples include:

- The percentage of motorway incidents cleared within one hour (the target is 85% between 06:00 and 22:00).

- Average delay per vehicle and number of flooding hotspots and priority culverts mitigated (priority culverts are those that are undersized).

The performance measurements were developed through a collaborative exercise involving specialists in different areas. The Department of Transport reviews Highways England’s performance annually. The results of the assessment are published, so in addition to the pressure exerted by government for not meeting performance targets, it also influences organizational reputation (Reeves, Winter, Leal, & Hewitt, 2019). Rapid recovery of routine events such as noninjury traffic accidents may be spurred by target times for clearance. Reputation and the impact on delay metrics also encourage improvements to speed recovery.

The report also provides examples of preparedness strategies such as establishing pre-determined diversion routes for the strategic road network (which are agreed upon with the local authorities that own the diversion routes); setting up mutually beneficial agreements like sharing salt supplies with other road

authorities; and preparing Disruption Risk Management Plans for various hazards or asset types. Within planning, establishing policies and targets are an essential step in laying the foundation for developing expectations of resilience, which in turn supports performance management. Transport Scotland stated that “by 2050, there will be less or no more disruption on the transport networks caused by flooding compared to 2010” (Reeves, Winter, Leal, & Hewitt, 2019). Goals like Transport Scotland’s help embed resilience at a high level and demonstrate the importance of resiliency across an agency.

Funding & Grants Programs

With the passage of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law in November 2021, resilience became a more prominent component of funding and grant programs. However, no major grant program defines performance measures related to measuring progress toward resilience goals. For instance, the National Infrastructure Investments program (now called BUILD) Grant Program; formerly called RAISE and TIGER) includes a national policy requirement related to critical infrastructure security and resilience (U.S. Department of Transportation, 2023). Under this guidance, projects are also evaluated as to whether they will improve the resilience of at-risk infrastructure to withstand extreme weather events. However, as yet, the RAISE program’s performance measure guidance does not yet include any suggested or example performance measures related to resilience (U.S. Department of Transportation, 2022).

Additionally, the FHWA has recently issued guidance on the PROTECT formula program (Federal Highway Administration, 2022). Under this guidance, the optional Resilience Improvement Plans prepared by state DOTS or MPOs may include performance measures that inform investment decisions. This may prove a resource in the future for tracking how DOTs are measuring resilience. However, the FHWA has not yet suggested performance measures related to resilience though more information is expected sometime this year as part of the PROTECT discretionary grant program guidance. Additionally, as part of its FY 2022-2026 strategic plan, the FHWA set an objective to promote planning practices for infrastructure resilience and enhance data collection and analysis for the risks to infrastructure posed by extreme weather (Federal Highway Administration, 2023).

Benefit-cost analysis (BCA) is an element of grant funding that provides a fruitful source of potential metrics to consider when thinking of RPMs. Since BCA is required to be completed from many grant programs, there are more robust methodologies available from which to draw, including recent work on incorporating costs and benefits of adaptation measures related to preparing for extreme weather events (Dewberry Engineers Inc. et al. 2020). This includes methodologies to quantify how investments may measure damage reduction and avoided transportation service losses, environmental benefits from reduced emissions and improved air quality, and social benefits. For measuring resilience, BCAs can draw on data collected as part of state and local hazard mitigation plans, FEMA BCA guidance, data from academic sources, and other commonly used sources such as Flood Insurance Rate Maps.

Summary: Given the intersectional nature of transportation, and its recognition as critical infrastructure, this section exhibits a summary of numerous resilience tools, metrics, models and indices used globally. Specifically, it presents examples and lessons learned from the energy, water/wastewater, and IT/cybersecurity sectors that support the continued development and evolution of RPMs within the transportation sector. Energy resilience research recommends improving collection and management of data at various levels; develop measures at system and regional levels; and improve understanding of how performance translates to outcomes at macro levels. resilience and service level should be included in governance throughout the lifecycle of an asset, bolstering the current framework in which public infrastructure is governed. This section also examines State DOT use cases and the monetization of risk.

Gaps: Many efforts have been made by different sectors to develop RPMs; however, the transportation sector is still in need of identifying and implementing more adequate and standardized RPMs to help agencies track their resilience efforts and goal achievements toward resilience. In particular, there is a lack of performance measurement guidance related to funding and grant programs. While certain metrics exist, they tend to be used for examining the past or present performance of infrastructure and are not used to evaluate and project the resilience of infrastructure against future climatic disruption.

Relevance for Practice: Resilience is not seen as a single outcome or a post-disaster recovery measure, but rather as a dynamic process that uses a risk and lifecycle-based method for addressing the vulnerabilities of critical infrastructure systems, making systems better able to adapt to unexpected challenges. The development and implementation of RPMs will help transportation agencies to measure how effective their resilience initiatives and efforts are with respect of their goals, enabling agencies to make data-driven decisions, monitor and improve their system resilience and performance.

Resilience and DOT Project Development Life Cycle

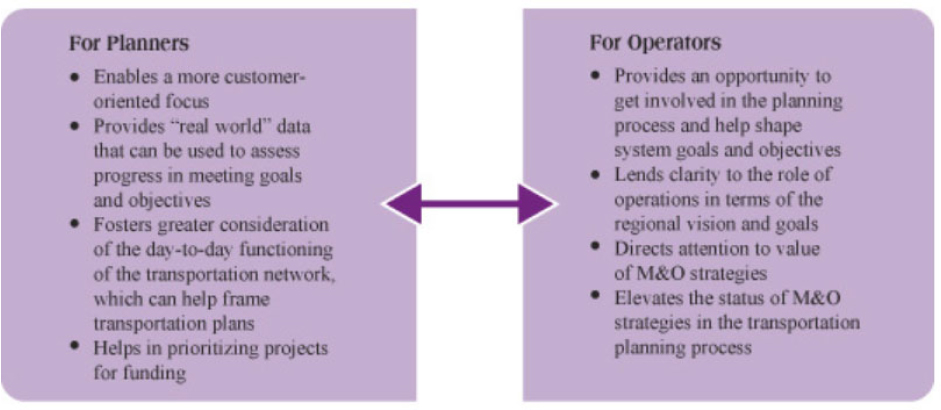

RPMs and the Planning to Operations Continuum

As defined by FHWA, resilience is “the ability to anticipate, prepare for, and adapt to changing conditions and withstand, respond to, and recover rapidly from disruptions” (Federal Highway Administration, 2014). This definition provides the basis to ensure operations continuum during and after a disruptive event.

Many studies have associated resilience with four attributes or properties: robustness, redundancy, resourcefulness, and rapidity (the four Rs) as defined below (Tierney & Bruneau, 2007):

- “Robustness—the ability of systems, system elements, and other units of analysis to withstand disaster forces without significant degradation or loss of performance;

- Redundancy—the extent to which systems, system elements, or other units are substitutable, that is, capable of satisfying functional requirements, if significant degradation or loss of functionality occurs;

- Resourcefulness—the ability to diagnose and prioritize problems and to initiate solutions by identifying and mobilizing material, monetary, informational, technological, and human resources;

- Rapidity—the capacity to restore functionality in a timely way, containing losses and avoiding disruptions.”

In addition to the attributes mentioned above, it has been identified that resilience has four domains or dimensions: technical, organizational, social, and economic as presented below (Tierney & Bruneau, 2007):

- “The technical domain refers primarily to the physical properties of systems, including the ability to resist damage and loss of function and to fail gracefully and includes the physical components that add redundancy.

- Organizational resilience relates to the organizations and institutions that manage the physical components of the systems. This domain encompasses measures of organizational capacity, planning, training, leadership, experience, and information management that improve disaster-related organizational performance and problem solving.

- The social dimension encompasses population and community characteristics that render social groups either more vulnerable or more adaptable to hazards and disasters. Social vulnerability indicators include poverty, low levels of education, linguistic isolation, and a lack of access to resources for protective action, such as evacuation.