Effectiveness and Efficiency of Defense Environmental Cleanup Activities of the Department of Energy's Office of Environmental Management: Report 2 (2022)

Chapter: 6 Enhancing the Effectiveness and Efficiency of the Cleanup Program

6

Enhancing the Effectiveness and Efficiency of the Cleanup Program

INTRODUCTION

This chapter addresses the final element of the task statement for this study (see Box 1.1 in Chapter 1) to

Make recommendations on actions to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of DOE-EM’s [Department of Energy’s Office of Environmental Management’s] cleanup activities.

The committee provides one finding and one recommendation in this chapter to address this task element, focused on the cleanup program’s growing liabilities1 and steps that should be taken by DOE-EM and others to reduce them. The finding and recommendation are referred to as “overarching” because they address the overall conduct of the cleanup program.

FINDING AND RECOMMENDATION ON ENHANCING EFFECTIVENESS AND EFFICIENCY

OVERARCHING FINDING: DOE-EM has spent about $200 billion over the past three decades on cleanup, yet unmet cleanup liabilities have increased to over $400 billion in fiscal year (FY) 2021. At the most recent annual

___________________

1 As noted in Chapter 3, liability refers to our nation’s financial obligation to clean-up the former nuclear weapons complex to meet applicable environmental standards and regulations. The Department of Energy tracks this obligation in its annual financial reports, available at https://www.energy.gov/cfo/listings/agency-financial-reports, accessed February 24, 2022.

appropriations level (about $7.9 billion for FY2022), the cleanup mission will not be completed for another six decades. DOE-EM’s inability to extinguish cleanup liability is attributable to at least six factors: (1) technical challenges in executing the cleanup mission; (2) constraints created by the requirements and preferences of multiple federal, state, and local stakeholders, including inflexible and outdated regulatory agreements; (3) lack of clearly defined strategic goals, objectives, and outcomes for completing the overall cleanup mission and assessing progress; (4) DOE-EM’s short-term, risk-averse focus on planning and implementing cleanup tasks absent a longer-term strategic portfolio-management framework; (5) cleanup program funding uncertainties and restrictions; and (6) frequent gaps and changes in top-level DOE-EM management and changes in DOE-EM reporting relationships within DOE.

OVERARCHING RECOMMENDATION: Several actions should be taken by Congress, the Secretary of Energy, and others to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the cleanup program and reduce cleanup liabilities:

- Congress should (1) authorize clearly defined strategic goals, objectives, and outcomes for the Department of Energy’s Office of Environmental Management’s (DOE-EM’s) cleanup program, (2) authorize and require DOE-EM to implement the committee-recommended portfolio-management framework for site cleanup, (3) provide flexibility in spending levels across cleanup sites so this framework can function more effectively and efficiently, and (4) enhance accountability for performance by requiring DOE-EM to provide regular reports on progress in implementing this framework and estimating its impacts on future cleanup liabilities.

- The Secretary of Energy, working with the administration and Congress, should (1) establish more predictable multi-year funding levels for the cleanup program and (2) improve the continuity of DOE-EM leadership and DOE-EM reporting relationships within DOE.

- The Secretary of Energy, working with federal and state regulators and with the support of the administration and Congress, should review, update, and restructure site-level regulatory agreements as needed.

DOE-EM has spent almost $200 billion and more than 30 years on cleanup and related activities since it was created in 1989. It has completed cleanup2 at 92 of 107

___________________

2 Cleanup completion does not mean that all waste and contamination have been removed. Some sites will continue to require active and/or passive remediation and surveillance long after cleanup activities are completed.

sites and continues cleanup work at the remaining 15 sites.3 GAO (2019) notes that an additional 45 sites could be transferred into the cleanup program in the future.

In spite of this progress, cleanup liabilities continue to grow faster than they are being extinguished:

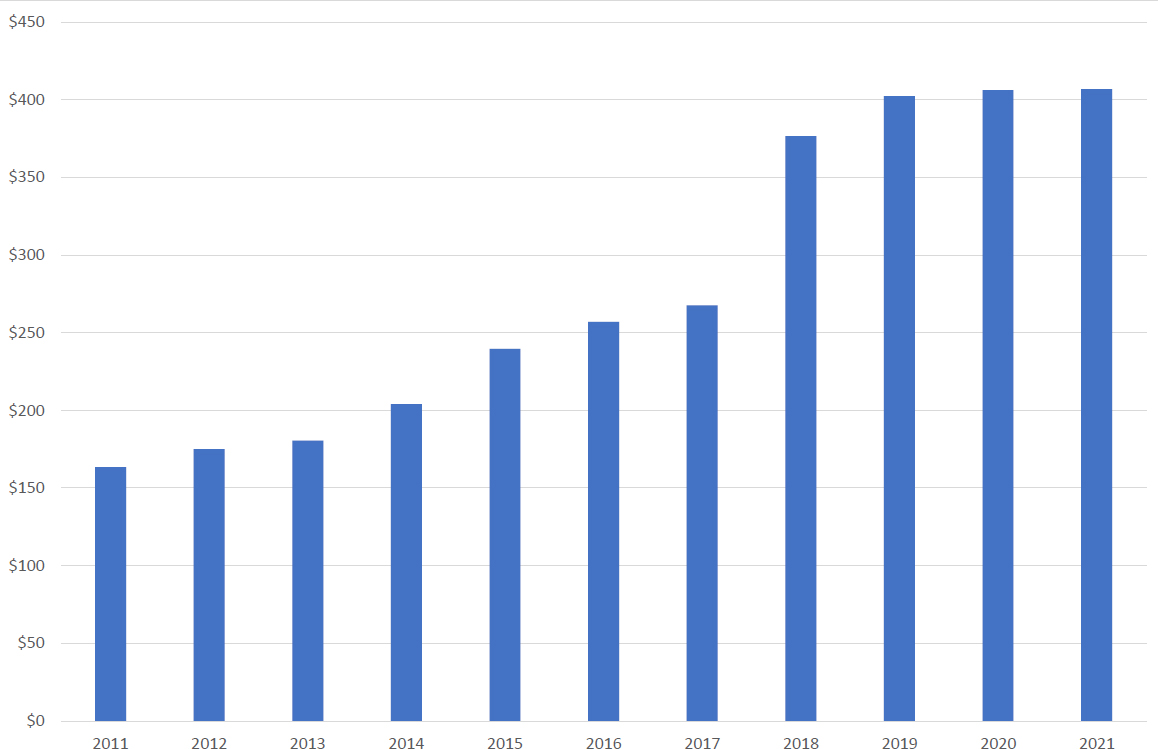

- Congress appropriated about $181 billion to DOE-EM cleanup from FY2000 through FY2021. Despite this substantial commitment of funding, estimated cleanup liabilities increased from about $164 billion in FY2011 to $407 billion in FY2021 (see Figure 6.1), an increase of about 148 percent.

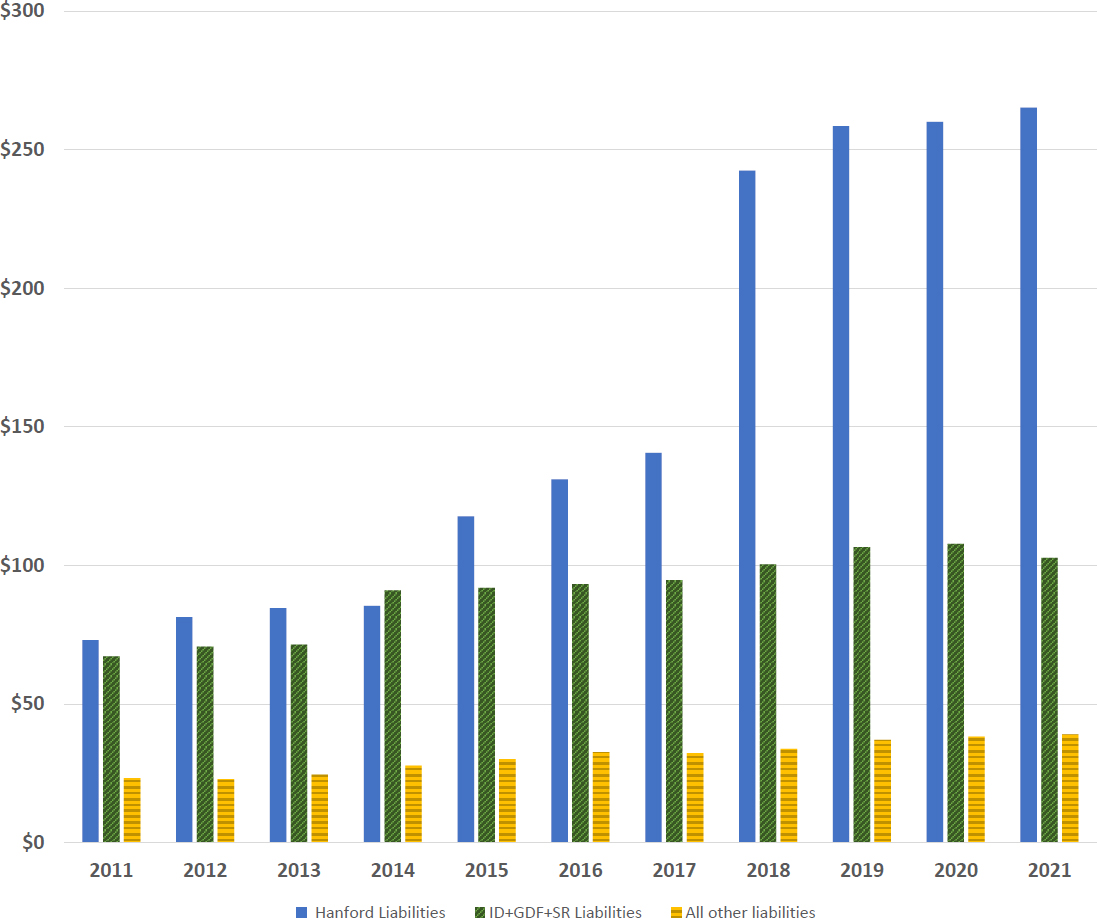

- Most of this change is attributable to liability growth for Hanford site cleanup (see Figure 6.2), which increased from about $73 billion in FY2011 to almost $265 billion in FY2021, an increase of more than 250 percent. Liabilities increased by about $100 billion from FY2017 to FY2018 alone. The latest (FY2022) liability estimate for Hanford ranges from about $293 billion to $634 billion4 (DOE, 2022a).

- Excluding Hanford, the estimated aggregate liability for all other sites increased from about $90 billion in FY2011 to $142 billion in FY2021, an increase of almost 60 percent (see Figure 6.2).

The total cost of the DOE-EM cleanup program (past expenditures plus future liabilities) will likely exceed $600 billion, even without any future liability growth or future inflation, exacerbated by extended schedules.

Liability growth can be attributed to the six factors shown in the overarching finding:

- Technical challenges in executing the cleanup mission.

- Constraints created by the requirements and preferences of multiple federal, state, and local stakeholders, including inflexible and outdated regulatory agreements.

- Lack of clearly defined strategic goals, objectives, and outcomes for completing the overall cleanup mission and assessing progress.

- DOE-EM’s short-term, risk-averse focus on planning and implementing cleanup tasks absent a longer-term strategic portfolio-management framework.

- Cleanup program funding uncertainties and restrictions.

- Frequent gaps and changes in top-level DOE-EM management and changes in DOE-EM reporting relationships within DOE.

___________________

3 See DOE Office of Environmental Management, “Completed Cleanup Sites,” https://www.energy.gov/em/completed-cleanup-sites and “Cleanup Sites,” https://www.energy.gov/em/cleanup-sites, accessed March 15, 2022.

4 These estimates are in real 2021 dollars. The lower estimate is the “baseline case” reflecting a theoretically achievable technical approach; the higher estimate accounts for various risks and uncertainties, particularly for completing tank waste cleanup (DOE, 2022a).

SOURCE: Data from 2000-2021 DOE Annual Financial Reports.

NOTE: GDF = Gaseous Diffusion Facilities at Portsmouth and Paducah; ID = Idaho Site; SR = Savannah River Site.

SOURCES: Data from 2000-2021 DOE Annual Financial Reports. “EM Liability Data for NAS 2011-2021_tank waste breakout.xls” provided in October 2021 by DOE-EM.

These factors are described in more detail in the following paragraphs.

TECHNICAL CHALLENGES IN EXECUTING THE CLEANUP MISSION

No other environmental cleanup program in the world comes close to matching the DOE-EM program in terms of size, complexity, and technical challenges.5 The complexity and challenges were not well understood during the early years of the cleanup program when initial liability estimates were made and regulatory agreements that set cleanup milestones and schedules were established with federal and state regulators. DOE-EM greatly underestimated the time and cost of cleanup.

CONSTRAINTS CREATED BY THE REQUIREMENTS AND PREFERENCES OF MULTIPLE FEDERAL, STATE, AND LOCAL STAKEHOLDERS, INCLUDING INFLEXIBLE AND OUTDATED REGULATORY AGREEMENTS

The cleanup program answers to many stakeholders—federal, state, tribal, and local governments as well as community interest groups—having different and sometimes conflicting preferences and requirements for how cleanup operations should be conducted and what their outcomes should be. Many of these stakeholder requirements and preferences are sensible in isolation—for example, regulatory requirements that focus on safety and environmental protection and preferences for job creation and community economic development—but none are focused on reducing liabilities for the overall cleanup program. In aggregate, they can drive the cleanup program in directions that increase liabilities.

The long-standing consent agreements between DOE, the Environmental Protection Agency, and states that host DOE-EM cleanup sites also contribute to liability growth. Many of the requirements in these agreements are outcomes-based6 rather than performance-based,7 which can drive DOE-EM toward costly and inefficient cleanup actions with no risk reduction benefit. These agreements require frequent amendments to keep pace with the changing understanding of

___________________

5 Technical challenges include the retrieval and immobilization of tens of millions of gallons of mixed (radioactive and hazardous) tank wastes and closure of hundreds of underground tanks, some of which are leaking; retrieval of radioactively contaminated buried wastes and remediation of radioactively contaminated soils and groundwater; and dismantlement and disposal of hundreds of highly contaminated facilities.

6 Outcomes-based requirements specify cleanup goals in terms of specific cleanup actions. For example, Milestone M-45-00 in the Hanford Federal Facility Agreement and Consent Order (Tri-Party, 2022, p. D-1) specifies “retrieval of as much waste [from single shell tanks] as technically possible, with tank residues not to exceed 360 cubic feet (cu. ft.) in each of the 100-series tanks, 30 cu. ft. in each of the 200-series tanks, or the limit of waste retrieval technology capability, whichever is less.”

7 Performance-based requirements specify cleanup goals in terms of allowable risks without regard to particular cleanup approaches or technologies.

the cleanup risks and technical capabilities, adding additional costs and time to cleanup. The 33-year-old Hanford Tri-Party Agreement (Tri-Party, 2022), for example, has undergone nearly 800 modifications, an average of almost 25 modifications per year.

The federal stakeholder most concerned about the cleanup program’s growing liabilities is Congress, particularly the House and Senate committees responsible for authorizing and appropriating funds for cleanup.8 There appears to be good alignment between Congress and DOE-EM on the annual scope of cleanup work to be funded through the appropriations process. However, the committee sees no alignment on how DOE-EM can reduce growing cleanup liabilities and successfully complete the cleanup mission.

LACK OF CLEARLY DEFINED STRATEGIC GOALS, OBJECTIVES, AND OUTCOMES FOR COMPLETING THE OVERALL CLEANUP MISSION AND ASSESSING PROGRESS

DOE-EM recently initiated a 10-year cleanup program planning effort (DOE, 2022b) and has developed conceptual schema for prioritizing cleanup on a site-by-site basis (DOE, 2020). To the committee’s knowledge, neither DOE nor Congress has established strategic goals, objectives, and outcomes to guide and track progress in completing the overall cleanup mission. The scope of cleanup activities are driven by incremental milestones set in environmental regulatory compliance agreements often established many years (or decades) ago.

Strategic “outcomes” describe the benefits that Congress and the administration want to achieve in undertaking the DOE-EM cleanup program. That program could have several such outcomes, for example,

- Minimizing the life-cycle cost of the cleanup program;

- Minimizing the duration of the cleanup program;

- Minimizing life-cycle risks to workers and/or the general public;

- Reducing the number of remaining cleanup sites as quickly as possible; and/or

- Minimizing annual expenditures on the cleanup program while meeting minimum safety and regulatory requirements.

The goals and objectives represent the strategies and actions for achieving the strategic outcomes.

Establishing strategic outcomes, goals, and objectives would likely require authorization from Congress and consultation with stakeholders. Alignment of the cleanup program with outcomes, goals, and objectives that have been clearly defined, agreed to, and continuously communicated within DOE-EM and with

___________________

8 The present study was mandated by Congress because of these concerns.

stakeholders is essential for reducing liabilities and completing the cleanup mission.

DOE-EM’S SHORT-TERM, RISK-AVERSE FOCUS ON PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTING CLEANUP TASKS ABSENT A LONGER-TERM STRATEGIC PORTFOLIO-MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK

The cleanup program is focused on achieving near-term milestones and does not aggressively pursue innovation beyond that needed to address specific problems with current cleanup projects and activities. In fact, the program is averse to innovation if it creates risks for achieving near-term milestones.9 DOE-EM lacks the completion mindset and urgency to finish the cleanup mission and instead defaults to the practice of frequent re-baselining of cleanup schedules and costs and renegotiation of regulatory agreements.

CLEANUP PROGRAM FUNDING UNCERTAINTIES AND RESTRICTIONS

Uncertainties in the annual appropriations cycle and restrictions on reprogramming of appropriated funds make it difficult for DOE-EM to plan and execute the cleanup mission on a multi-year basis. It also prevents DOE-EM from taking advantage of opportunities to accelerate cleanup by reprogramming funds among sites. This is a problem for all federal programs but a particular problem for complex, multi-site, and multi-decade programs such as the cleanup program.

FREQUENT GAPS AND CHANGES IN TOP-LEVEL DOE-EM MANAGEMENT AND CHANGES IN DOE-EM REPORTING RELATIONSHIPS WITHIN DOE

DOE-EM has had 18 leadership changes since 1989, or about one change every 1.8 years (see Table 6.1). Senate-confirmed DOE-EM assistant secretaries have led the cleanup program only about 60 percent of the time. The DOE-EM reporting line has changed five times since 2000 (see Table 6.2). These changes, as well as frequent internal DOE-EM reorganizations, severely disrupt operational continuity and negatively impact staff effectiveness and accountability.

___________________

9 DOE-EM and its contractors have demonstrated that they can innovate when needed but do not include innovation as an integral part of the cleanup strategy. Previous National Academies’ reports have described some of these innovations, for example, passive subsurface redox barriers for in-situ groundwater treatment and capillary-evapotranspiration surface barriers for capping waste sites (NRC, 2001); caustic-side solvent extraction for treating tank wastes (NRC, 2000); and new waste forms for immobilization of tank wastes (NASEM, 2011).

TABLE 6.1 Leadership of the Department of Energy’s Office of Environmental Management

SOURCES: Department of Energy (DOE), 2019, “Past Assistant Secretaries for Environmental Management,” December 12, https://www.energy.gov/em/past-assistant-secretaries-environmental-management; DOE, “William “Ike” White,” https://www.energy.gov/em/person/william-ike-white, accessed March 31, 2022.

TABLE 6.2 The Department of Energy’s Office of Environmental Management (DOE-EM) Reporting Relationships Within DOE

SOURCE: DOE organization charts.

The overarching recommendation provides a list of actions needed by Congress, the Secretary of Energy, and others to arrest liability growth and set the cleanup program on a path for future success:

Congress should:

- Authorize and require DOE-EM to implement the committee recommended portfolio-management framework for site cleanup. This framework is explained in detail in Chapter 5 of this report.

- Provide flexibility in spending levels across cleanup sites so this framework can function more effectively and efficiently. Effective portfolio management requires alignment of resources with cleanup goals, objectives, and outcomes rather than with individual sites.

- Require DOE-EM to provide regular reports on progress in implementing this framework and estimating its impacts on future cleanup liabilities. The committee judges that DOE-EM is unlikely to implement the recommended portfolio-management framework unless Congress directs it to. This judgment is based on DOE-EM’s failure to implement almost two decades of recommendations from external reviewers to improve project management practices. (See Appendix C in the Phase 1 report [NASEM, 2021] for a discussion of notable external reviews.) DOE-EM’s continuing failure to improve project management practices is a root cause of cleanup liability growth over the past decade.

The Secretary of Energy, working with the administration and Congress, should:

- Establish more predictable multi-year funding levels for the cleanup program. This includes action by DOE and the administration to develop and submit to Congress feasible multi-year budget projections consistent with

- portfolio, program and project plans, and action by Congress to enact multi-year authorization bills. Predictable funding will help reduce delays in achieving cleanup goals and objectives and extinguishing cleanup liabilities.

- Improve the continuity of DOE-EM leadership and DOE-EM reporting relationships within DOE. A good first step to implement this recommendation would be for the Secretary of Energy and the White House to nominate a qualified candidate for assistant secretary as soon as possible and request Congress to act on it promptly.

The Secretary of Energy, working with federal and state regulators and with the support of the administration and Congress, should review, update, and restructure outdated site-level regulatory agreements. Incorporating performance-based requirements into these agreements that are focused on achieving specified levels of risk reduction could benefit all parties by accelerating the pace of the cleanup program and reducing cleanup liabilities.

Implementing these recommendations, particularly for greater funding flexibility/predictability and regulatory reform, could disrupt well-established relationships for some within DOE-EM, the contractor community, the regulator community, and local stakeholders. Nevertheless, absent such changes, the nation’s cleanup liabilities will continue to grow, DOE-EM will continue to miss important cleanup milestones, and the communities and tribal nations located near DOE-EM sites will continue to bear the risks from further delays in site restoration.

REFERENCES

DOE (Department of Energy). 2020. “Environmental Management Program Management Protocol.” Washington, DC: Office of Environmental Management. https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2021/02/f82/EM_Program_Management_Protocol_11-06-2020.pdf.

DOE. 2022a. Hanford Scope, Schedule and Cost Report. Richland, WA. https://www.hanford.gov/files.cfm/2022_LCR_DOE-RL-2021-47_12-27.pdf.

DOE. 2022b. EM Strategic Vision: 2022-2032. Washington, DC: Office of Environmental Management. https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2022-03/DOE-EM-Strategic-Vision-2022Final-3-8-22.pdf.

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2019. Nuclear Waste Cleanup: DOE Could Improve Program and Project Management by Better Classifying Work and Following Leading Practices. GAO 19-223. Washington, DC. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-223.pdf.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2021. Effectiveness and Efficiency of Defense Environmental Cleanup Activities of DOE’s Office of Environmental Management: Report 1. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26000.

NRC (National Research Council). 2000. Alternatives for High-Level Waste Salt Processing at the Savannah River Site. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9959.

NRC. 2001. Science and Technology for Environmental Cleanup at Hanford. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10220.

Tri-Party. 2022. Hanford Federal Facility Agreement and Consent Order. As Amended Through June 13, 2022. 89-10 REV. 8. Washington State Department of Ecology, Environmental Protection Agency, and Department of Energy. https://www.hanford.gov/files.cfm/HFFACO.pdf.

This page intentionally left blank.