Potential Hydrodynamic Impacts of Offshore Wind Energy on Nantucket Shoals Regional Ecology: An Evaluation from Wind to Whales (2024)

Chapter: 4 Potential Ecological Impacts of Offshore Wind Turbines

4

Potential Ecological Impacts of Offshore Wind Turbines

STATE OF UNDERSTANDING

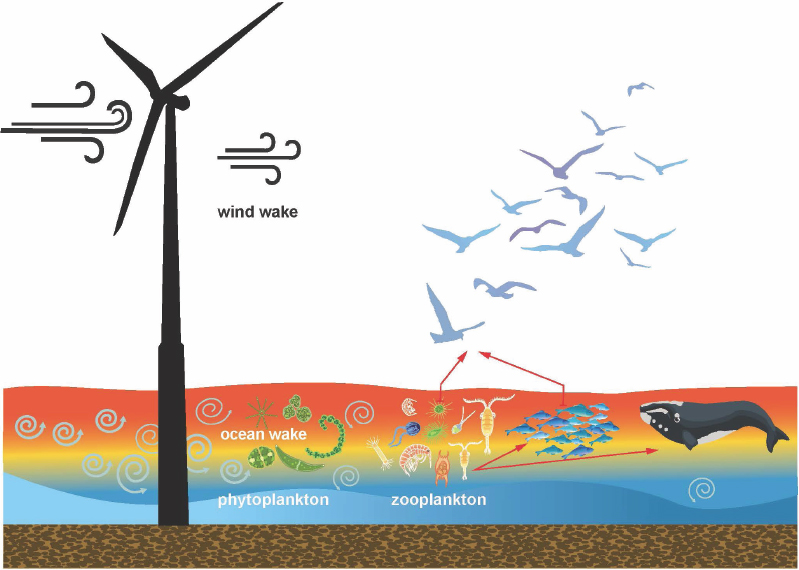

The presence of wind turbines has the potential to impact hydrodynamic processes, though the magnitude and direction of any potential impacts remain poorly understood and difficult to parameterize, as discussed in Chapter 3. If present, significant impact(s) to hydrodynamic processes may in turn impact primary production as well as upper-trophic-level consumers (Figure 4.1). In the Nantucket Shoals region, potential changes to the supply, abundance, and aggregation of zooplankton may, in turn, affect the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale, which has recently been observed foraging in this habitat. As described in Chapter 2, copepods are the primary prey of right whales, particularly Calanus finmarchicus. Although these zooplankters are capable of swimming (Hirche, 1987), they are advected and aggregated by various physical forcing mechanisms and regimes (Sorochan et al., 2021). The presence of copepod concentrations in sufficient density to allow for profitable feeding in right whales (reviewed in Ross et al., 2023, table 2) is the product of several factors, which mirror the three scales of interest for offshore wind energy development: turbine, wind farm, and regional. At the largest scale, a supply of copepods must be produced that are available in sufficient quantities to support reproduction and maintenance of right whale populations (Fortune et al., 2013), and this supply must be delivered to the region where right whales are able to find and access these prey. At the scale of the wind farms, the processes and conditions that support copepod growth, produce aggregations, and influence where copepods are found in significant concentration(s) are important. Finally, at the scale of the turbine, combinations of water mass movements, bathymetry, and submesoscale circulation patterns are important for aggregating copepods. Changes in prey availability can have important conservation implications by directly affecting right whale reproduction rates (Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2015) and/or triggering distribution shifts that reduce the efficacy of protective policies (Davies and Brillant, 2019;

Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2018). This chapter reviews what is known about the impacts of wind turbines on surrounding ecosystems and assesses what is known about how these mechanisms may affect the ecosystem of the Nantucket Shoals region, with a focus on how these influence right whales.

Ability to Accurately and Precisely Estimate Potential Effects on Ecosystems

Most relevant studies of the ecological effects of wind turbines and wind farms have been done for installations in the North Sea and are summarized in the following sections. These studies represent potential ecological effects that may occur in the Nantucket Shoals region, but the magnitude and degree of impact may differ from the North Sea, especially in terms of potential impact on zooplankton and right whales.

Turbine Scale

The turbine structure provides a hard substrate (artificial reef) that creates habitat for rapid colonization by many species (e.g., Degraer et al., 2020). The habitat gain provided by wind turbines can enhance abundances of local species, alter local biodiversity, and create new feeding areas for many species (Bergström et al., 2014). The turbine provides vertical substrates as well as a range of horizontal habitats that are defined by foundation type (Degraer et al., 2020). Species that live on and attach to the turbine structure form a new community that can affect the benthic community beneath a turbine and the local pelagic food web. Many of the species that attach to the hard surface of the turbine are suspension feeders that can represent over 95 percent of the biomass on artificial structures (Coolen et al., 2018). These suspension feeders have the potential to reduce local concentrations of phytoplankton, microzooplankton, and mesozooplankton (e.g., Degraer et al., 2020), increase the supply of pelagic food to the benthos (Slavik et al., 2019), and enrich the organic matter content of sediments around turbines (Maar et al., 2009).

Removal of phytoplankton biomass via filtration has the potential to alter pelagic primary production which in turn can alter the local food web and biogeochemical cycling (Slavik et al., 2019; Degraer et al., 2020). As an example, the blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) is a dominant colonizing suspension feeding species on wind turbines. In addition to affecting the pelagic food web via filtration and the benthic community via organic matter deposition, this species has the potential to modify ecosystem structure in the local vicinity of turbines via reef-building on the surrounding sediments, as has been observed around turbines in the North Sea (Lefaible et al., 2019) and Block Island (Hutchison et al., 2020a,b). Increased availability of hard substrates can facilitate the establishment of non-native species by creating new dispersal pathways that support migrations into new regions (Adams et al., 2014), thereby altering local biodiversity. For example, in the North Sea, the barnacle Balanus perforatus expanded farther north using the offshore wind farm habitat (Glasby et al., 2007; De Mesel et al., 2015). The scour protection materials around wind turbine pilings (e.g., concrete mattresses or rocks) also increase the availability of hard substrate, creating new benthic habitat. The observed ecological effects of turbine scour protection include shifts in community composition, modified biomass abundances, changes in biodiversity, and introduction of new species (Hutchison et al., 2020b; Wilson and Elliott, 2009; Ter Hofstede et al., 2022). Burkhard et al. (2011) implemented an integrated modeling framework that linked circulation, ecosystem, and food web models to assess the impacts of wind farms on trophic levels, biotic diversity, and energy transfer, with a focus on the effect of additional hard substrate provided by piles. This analysis showed small changes in total system biomass before and after wind farm construction, suggesting that the artificial reef effect from the piles would not have a significant impact on the structure and energy flow of the local ecosystem.

A review of several studies of the local ecosystem impacts of wind turbines showed that the primary effect of the additional hard substrate was to increase aggregations and locally increase abundances of pelagic and benthic species (e.g., Bergström et al., 2014).

Studies of ecosystem changes resulting from the artificial reef effect on higher trophic levels have shown changes in feeding behavior of specific fish species, aggregation behavior around wind turbines (Reubens et al., 2014), and site fidelity (Reubens et al., 2013). Sampling at sites before and after construction, operation, or presence phase of offshore wind farms (Before-After-Control-Impact design; Green, 1979) has been used to detect changes in fish species or fish groups (Methratta et al., 2020, table 2 and references). The changes detected by these observational studies include increased fish assemblages around foundations over short and long times, increased biomass of certain species (e.g., crabs, lobsters), and increased biodiversity (Methratta et al., 2020; Perry and Heyman, 2020). However, differentiating avoidance and attraction effects of offshore wind turbines on various species from seasonal and weather effects was difficult. These studies showed inconsistent or weak effects of offshore wind turbines on fish, with the implication that the disturbance from these structures is small relative to natural variability (e.g., van Hal et al., 2017; Methratta et al., 2020).

Observational assessments of the impacts of wind turbines, including wake effects, on local zooplankton assemblages, production, and aggregation are limited. A study of zooplankton in a wind farm in coastal waters off China showed no significant difference in the spatial distribution of zooplankton within and outside of the wind turbines, a change in the relative abundance of zooplankton species after wind turbine construction, increased microzooplankton abundance, and decreased macrozooplankton abundance (Wang et al., 2018). The decrease in macrozooplankton biomass was correlated with suspended sediment concentration, which may be related to turbine effects on local flow (Wang et al., 2018).

Wind Farm Scale

Simulations obtained from a coupled hydrodynamic–ecosystem model were used by Daewel et al. (2022) to project the effects of increasing offshore wind generation capacity in the North Sea on the ecosystem. Simulations showed that increasing the amount of future offshore wind farm installations relative to current capacity will alter the wind field, resulting in a shoaling of the mixed-layer depth, modifications to the vertically averaged horizontal velocities, and production of an upwelling/downwelling dipole in the wind farm region of the southern and central North Sea. Daewel et al. (2022) showed about a 10 percent increase/decrease in simulated net primary production inside the offshore wind farm region, which was attributed to modified nutrient supply from the upwelling/downwelling circulation. The increased phytoplankton biomass resulted in about a 12 percent increase in zooplankton biomass, suggesting that grazing control on the local ecosystem could be enhanced by wind farms. The increased zooplankton production could be consumed by higher trophic levels with implications for ecosystem structure (Daewel et al., 2022). Consequently, the changes in primary production at wind farm scales were considered to be potentially important for ecosystem productivity and ecosystem structure (Daewel et al., 2022). Moreover, changes in current velocities modified bottom stress, resulting in reduced resuspension of organic matter, thereby increasing local sediment carbon by 6 percent to 10 percent, potentially enriching the benthos (Daewel et al., 2022).

Slavik et al. (2019) assessed the sensitivity of pelagic primary productivity to increased abundance and distribution of M. edulis in North Sea wind farms. This analysis used a coupled circulation–ecosystem model that included an empirically based filtration model to simulate removal of phytoplankton carbon by M. edulis. Simulation scenarios assessed the effects of only epibenthic mussels versus the effects of additional epistructural M. edulis at the wind farms. The simulations showed that the increased presence of M. edulis in wind farms can reduce phytoplankton productivity by up to 8 percent but with considerable variability in the magnitude of the change over the 11 years (2003–2013) included in the simulation, with some years showing little to no change. The differences in simulated productivity may reflect natural annual variability in the patterns of phytoplankton productivity in the regions included in the simulation (Slavik et al., 2019). The presence of M. edulis also changed the magnitude and timing of delivery of organic matter to the sediment which has implications for biogeochemical cycling (Slavik et al., 2019; De Borger et al., 2021).

Regional Scale

The effects of offshore wind turbines on ecosystem structure and production at the regional scale are difficult to quantify because of the complexity of potential responses that encompass a wide range of time and space scales. Daewel et al. (2022) found changes in net primary production that extended outside of offshore wind farms, but when integrated over the regional scale of the North Sea, the positive and negative changes tended to cancel. Regional averages of net primary production for the whole North Sea and surrounding regions showed reductions of −0.5 percent, which is within natural variability. Sediment carbon showed only about a 0.2 percent increase when averaged over the North Sea, again within natural variability.

Simulations of the epistructural filtration from increased abundances of M. edulis showed that potential ecosystem effects extend beyond the local wind farm to regional scales (Slavik et al., 2019). The simulations showed decreased phytoplankton carbon within 20 km of an offshore wind farm and an increase up to 50 km outside the wind farm area, changes that were attributed to M. edulis filtration. These regional effects arise from complex ecosystem interactions that control nutrient, phytoplankton, and zooplankton production. Slavik et al. (2019) conclude that the increased abundance of M. edulis associated with offshore wind farms only moderately affects ecosystem functioning via modifying net primary production but suggest that the effect on benthic structure (reef building) and as prey for higher trophic levels may be more important.

Assessing the regional-scale ecosystem effects of turbines requires observations, analyses, and models that can account for and isolate turbine-generated perturbations from those produced by regional-scale ecosystem processes, including climate change–driven alterations in those processes. The modeling studies done to date focus on identifying effects on nutrient cycling, primary production, and secondary production. Quantitative studies of the effects on regional-scale species distribution and diversity are needed, especially for higher trophic levels, to isolate species-specific effects of offshore wind farms from natural variability.

Importance of Linking Ecological and Hydrodynamic Models

Baleen whales, such as the endangered North Atlantic right whale, rely on dense aggregations of their zooplankton prey for successful foraging (Fortune et al., 2013; van der Hoop et al., 2019). To meet energetic demands, right whales typically target the lipid-rich late copepodite and adult stages of C. finmarchicus (Figure 2.4; Wishner et al., 1995; DeLorenzo Costa et al., 2006) in densities of 1,000–10,000 individuals/m3 (Baumgartner and Mate, 2003; Fortune et al., 2013). Energetic demands of lactating females are even higher, requiring them to target late-stage C. finmarchicus median densities >15,000 individuals/m3 (Gavrilchuk et al., 2021). Nutritional variability within a given copepod life stage varies with environmental parameters and may also impact right whale foraging success (DeLorenzo Costa et al., 2006; Michaud and Taggart, 2007; McKinstry et al., 2013). Right whales forage on relatively shallow (hundreds of meters or less) aggregations of C. finmarchicus and thus concentrate their feeding on the continental shelf (Baumgartner et al., 2003, 2017; Plourde et al., 2019). Hydrodynamic processes impact the production, growth, and advection of right whales’ zooplankton prey within a region, as well as the concentrating mechanisms that govern the density of zooplankton within an aggregation (Figure 4.2, reviewed in Sorochan et al., 2021).

Hydrodynamic Impacts on Zooplankton Abundance and Density

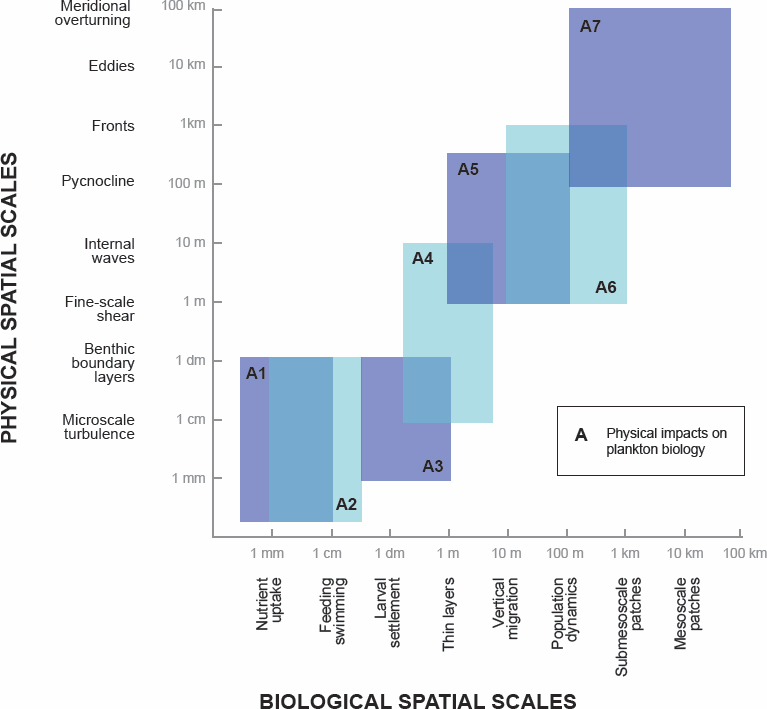

Hydrodynamics influence zooplankton at a range of spatial scales, from large-scale circulation patterns that supply or remove zooplankton to fine-scale physics that contribute to the formation of high-density patches (Prairie et al., 2012, fig. 3). The most important physical processes will depend on the time of year, location, and behavior and life history of the species in question. Although late-stage C. finmarchicus is the primary prey, right whales also feed on other Calanus stages and other zooplankton species, such as Pseudocalanus spp., Centropages spp. and barnacle larvae (Mayo and Marx, 1990; Hudak et al., 2023). These different species have varied interactions with the physical environment.

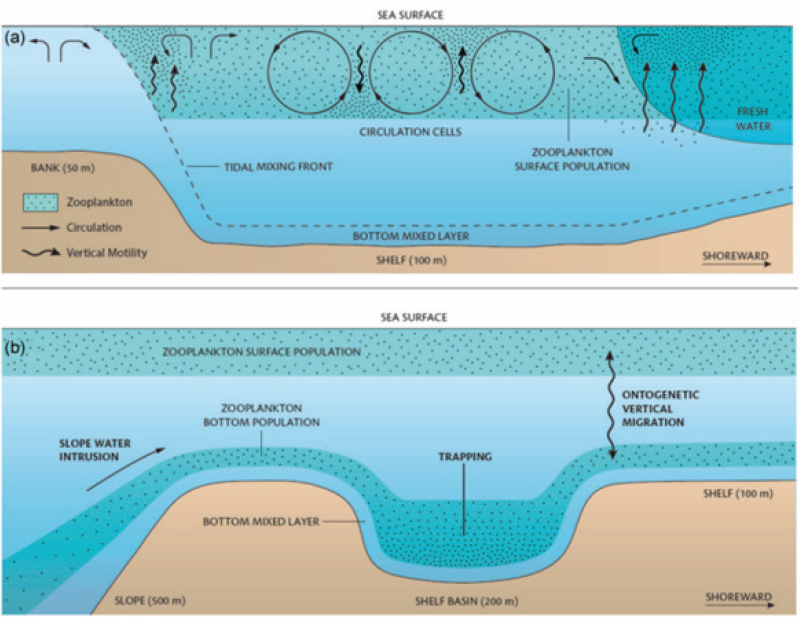

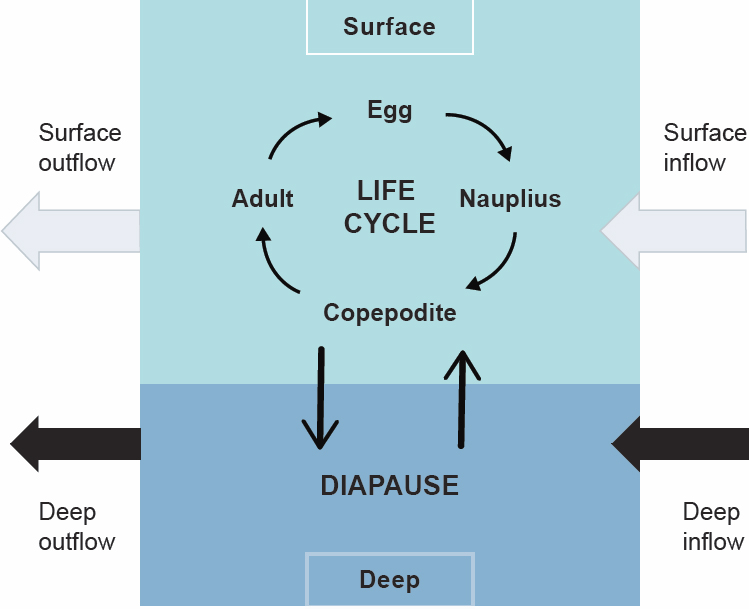

Climate-driven changes to ocean temperatures and circulation have significant potential to reduce the spatial extent and density of C. finmarchicus, a critical species in the Northwest Atlantic food web (Reygondeau and Beaugrand, 2011; Grieve et al., 2017; Chust et al., 2014). Abundance of C. finmarchicus is highly sensitive to oceanographic and ecological conditions, due to trophic and demographic impacts at the local scale (Frank et al., 2005; Ji et al., 2022; Wiebe et al., 2022), fluctuations in temperature and salinity driven by shifting water masses (MERCINA Working Group, 2012; Davies et al., 2014; Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2021), and changes in advective patterns that impact C. finmarchicus downstream supply (Ji et al., 2017; Greene and Pershing, 2000; MERCINA Working Group, 2004; Ji et al., 2022). For example, in the coastal amplification of supply and transport (CAST) hypothesis, biologically productive coastal waters support the rapid reproduction and growth of C. finmarchicus individuals that may then be advected to boost the population in the Wilkinson Basin, just upstream of the Nantucket Shoals (Figure 2.2; Ji et al., 2017). However, modeling of advective transport is complex because it operates differently depending on the life stage of the individual copepod; naupliar life stages and reproductive adults are affected by surface currents, and diapausing copepodites in ocean basins are affected by deeper currents and bathymetry (Figures 4.3 and 4.4; Ji et al., 2022).

Local factors also contribute to the production, growth, advection, and aggregation of C. finmarchicus, and thus contribute to the suitability of a habitat for right whale foraging. Oceanographic processes that increase local stratification, including freshwater transport from the Arctic Ocean and incursions of warm Gulf Stream water have been linked to declines in C. finmarchicus (MERCINA Working Group, 2012; Greene et al., 2013; Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2021), and this may be caused by an ecological shift to smaller zooplankton taxa during highly stratified, summer-like, water column conditions (Pershing and Kemberling, 2023). As an income breeder, C. finmarchicus production is strongly associated with seasonal variability in the phytoplankton and microzooplankton available for adult females to consume (Durbin et al., 2003; Runge et al., 2006). For effective foraging, right whales target high-density patches of prey (3,000–15,000 copepods/m3; Wishner et al., 1988; Baumgartner and Mate, 2003) that have been aggregated by copepod behavior and/or local physical concentrating processes. Aggregation density of late-stage C. finmarchicus is spatially and temporally heterogeneous but is difficult to capture in models (Ross et al., 2023). The processes

that lead to zooplankton patch formation vary across the different foraging habitats and depend on circulation features, bathymetry, and water mass structure (reviewed in Sorochan et al., 2021). In areas with complex bathymetry, tidal currents can interact with steep bathymetric gradients to form dense patches of diapausing C. finmarchicus (Davies et al., 2013), and these patches have been associated with fine-scale water mass features within a single basin (Davies et al., 2014).

The supply, transport, and aggregation of late-stage C. finmarchicus also responds to oceanographic processes across a range of temporal scales. Natural and anthropogenic climate processes have been linked to reductions in C. finmarchicus supply to right whale

foraging habitats on decadal scales, with reductions in prey availability demonstrated in the 1990s (Greene et al. 2013; Meyer-Gutbrod and Greene, 2014) and 2010s (Record et al., 2019; Sorochan et al., 2019; Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2021, 2022). Interannual variability in abundance can depend on the direction and strength of winds and coastal currents and their contribution to particle retention (Jiang et al., 2007). Individual copepod lipid content also varies annually, perhaps due to fluctuations in temperature or phytoplankton abundance (Sorochan et al., 2019; McKinstry et al., 2013). There is strong seasonal variability in the relative proportion of adult-stage C. finmarchicus (Meise and O’Reilly, 1996; Ji et al., 2022) and their individual lipid content (Michaud and Taggart, 2007; DeLorenzo Costa et al., 2006). Patch formation and persistence is highly ephemeral and can vary at the scale of hours (Baumgartner et al., 2003).

For smaller copepod species that may contribute to right whale diets in southern New England, life history and behavior can interact with physics to determine the spatiotemporal abundance patterns. For example, for genera such as Pseudocalanus and Centropages, vertical migration, cannibalism, and spawning strategies interact with circulation patterns to shape distributions in and around the Gulf of Maine (Ji et al., 2009; Stegert et al., 2011).

Effects of Zooplankton on Right Whale Distribution and Demography

Oceanographic processes governing the North Atlantic over the past 40 years explain considerable variation in late-stage C. finmarchicus abundance in the Gulf of Maine region (Greene et al., 2013) and have been shown to directly affect right whale demography and distribution (Pendleton et al., 2009; Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2021, 2022). For example, in spring 1992, right whales were not seen in their typical foraging area in the Great South Channel, likely corresponding to a shift in the zooplankton community which occurred in conjunction with unusually low salinity (Kenney et al., 2001). From 1993 to 1997, Roseway Basin on the western Scotian Shelf was abandoned by the right whales, again in response to low prey densities (Patrician and Kenney, 2010; Davies et al., 2015). Because of the high energy demand of reproduction (Fortune et al., 2013), these periods of low prey availability decreased calving rates and thus directly affected population growth (Greene and Pershing, 2004; Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2015).

During a later decade (2010–2019), the Gulf of Maine/western Scotian Shelf region warmed more rapidly than most of the global ocean (Pershing et al., 2015). Associated reductions in late-stage C. finmarchicus in these regions again led to poor foraging conditions and declines in right whale calving rates (Record et al., 2019; Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2021). Right whale use of the Gulf of Maine, Bay of Fundy, and Scotian Shelf regions also declined substantially during this period while a large portion of the population began to utilize the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence during spring, summer, and autumn (Davis et al., 2017; Davies et al., 2019; Record et al., 2019; Simard et al., 2019; Crowe et al., 2021; Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2021, 2022). Concurrently, right whale abundance increased, and timing of habitat use shifted almost 3 weeks over 21 years in Cape Cod Bay (Ganley et al., 2019; Pendleton et al., 2022), while right whales repatriated historic whaling grounds south of Cape Cod (O’Brien et al., 2022).

Increased use of Cape Cod Bay and southern New England may be driven by spatiotemporal inconsistencies in the patterns of C. finmarchicus abundance in the previous decade. Although late-stage C. finmarchicus declined in the central and eastern portions of the Gulf of Maine, primarily in the late summer and fall, abundance increased in the southeastern portion of the Gulf, paralleling spring increases in Cape Cod Bay and Wilkinson Basin (Ji et al., 2017; Record et al., 2019; Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2022). This regional increase in zooplankton could supply the downstream Nantucket Shoals region, potentially explaining the recent increase in right whale foraging in this area (Quintana-Rizzo et al., 2021; O’Brien et al., 2022). Prior to the shift, Pendleton et al. (2012) predicted favorable foraging habitats in this region at this time of year based on copepod abundance patterns. In the Cape Cod Bay region, and thus in the downstream Nantucket Shoals region, smaller zooplankton species such as earlier stages of C. finmarchicus, the Pseudocalanus complex, Centropages spp. and barnacle larvae may also be important to right whale diets (Pendleton et al., 2009; O’Brien et al., 2022; Hudak et al., 2023). However, the nutritional value of these smaller zooplankton prey is significantly less than late-stage C. finmarchicus due to smaller individual body mass and reduced lipid stores (Table 4.1; DeLorenzo Costa et al., 2006), thus most research on right whale prey dynamics is focused on late-stage C. finmarchicus. Although research

TABLE 4.1 Variability in the nutritional value of the major copepod species in Cape Cod Bay (Massachusetts, USA)

| Species | Stage | Number of Samples | mg-C Individual−1 | C/N Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular Stations | Whale Stations | % C | ||||

| Centropages | female | 64 | 6 | 39.5 | 14.2 ± 1.5 | 3.7 ± 0.07 |

| male | 63 | 6 | 40 | 12.1 ± 1.4 | 3.7 ± 0.09 | |

| V | 64 | 3 | 39.7 | 6.4 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 0.11 | |

| all | 191 | 15 | 39.7 | 11.0 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.01 | |

| Pseudocalanus | female | 83 | 4 | 45.7 | 20.6 ± 3.7 | 4.4 ± 0.39 |

| V | 76 | 3 | 49.6 | 15.6 ± 3.3 | 5.5 ± 0.55 | |

| all | 159 | 7 | 47.6 | 18.2 ± 0.3 | 5.0 ± 0.06 | |

| Calanus | female | 52 | 19 | 48.3 | 148.6 ± 35.7 | 5.0 ± 0.87 |

| male | 5 | 5 | 57.5 | 190.7 ± 21.3 | 7.6 ± 0.66 | |

| V | 116 | 28 | 58.1 | 169.3 ± 43.0 | 8.2 ± 0.86 | |

| IV | 87 | 16 | 52.1 | 54.6 ± 17.0 | 6.3 ± 1.03 | |

| III | 50 | 10 | 43.9 | 13.6 ± 5.0 | 4.4 ± 0.72 | |

| II | 14 | 0 | 36.4 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.05 | |

| all | 324 | 78 | 52.4 | 109.9 ± 3.6 | 6.5 ± 0.09 | |

SOURCE: DeLorenzo Costa et al., 2006.

on these smaller taxa is limited, recent fluctuations in their abundance and aggregation may be a driving factor in right whale foraging in this region.

As right whale distributions change, policies to effectively mitigate anthropogenic impacts have become more challenging. The rapid shift in distribution and phenology in the 2010s has likely contributed to the species’ unusual mortality event as they became more vulnerable to ship strikes and entanglements in unprotected waters. With reduced reproduction and elevated mortality rates, the right whale population began to decline around 2015 for the first time since post-whaling demographic data became available during the early 1980s (Pettis et al., 2021; Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2021). During this past decade, total population size has declined an estimated 26 percent, with the U.S. Endangered Species Act classifying the species as endangered and the International Union for Conservation of Nature reclassifying the species’ status from endangered to critically endangered.

EFFECTS OF HYDRODYNAMIC PERTURBATIONS ON ECOSYSTEM DYNAMICS IN THE NANTUCKET SHOALS REGION

As detailed in Chapter 2, the Nantucket Shoals region is characterized by dynamic ocean processes supporting a complex marine ecosystem. Its dominant hydrodynamic features include significant southwestward currents and strong seasonal stratification of the water column from June through September with waters well mixed the remainder of the year. This stratification is influenced by significant tidal mixing around the actual Nantucket Shoals and south of Martha’s Vineyard with tidal effects declining to the

west. Advection is driven by the westward coastal currents along the shelf with transport from both the Gulf of Maine through the Great South Channel and over Nantucket Shoals, and over the mid shelf by transport from Georges Bank.

This historical character of the Nantucket Shoals region is now influenced by major changes that have occurred in its oceanography since 2000. A change point occurred in 2010–2011 when both surface and bottom temperatures began to dramatically increase (Friedland et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021b). This was followed by distinct ocean heat waves in 2012 and 2017 that have been attributed to atmospheric forcing and Gulf Stream warm core rings (Chen et al., 2014; Gawarkiewicz et al., 2019). Gulf Stream meanders have moved progressively northward and westward (Saba et al., 2016; Seidov et al., 2021) with increasing frequency of the intrusion of warm core rings onto the shelf. These intrusions have moved farther inshore into the tidal mixed area (Gawarkiewicz et al., 2022). Multiple intrusions are apparent in some summer depth profiles, which could produce multiple layers of zooplankton. Up to 50 percent of the profiles now show intrusions in summer, and 70 percent of the intrusions occurred in proximity to warm core rings (Silver et al., 2023). As a result, the shelf-break front is moving farther inshore. Seasonal stratification is thus changing and extending further into the fall. Effects on the spring are unclear.

This flux in the physical oceanography of the Nantucket Shoals region affects the Nantucket Shoals marine ecosystem at all levels and could account for its current characterization as a major foraging area for the right whales during winter–spring. The shift of right whales’ residency into the area appears to have occurred after the 2010–2011 change point in the Nantucket Shoals region (Quintana-Rizzo et. al., 2021). However, recent increases in use of the Nantucket Shoals region by right whales may also be driven by declines in prey availability elsewhere. Thus, the distribution patterns of right whales cannot be predicted exclusively with local or regional ecosystem dynamics (e.g., Meyer-Gutbrod et al., 2022).

Hydrodynamic perturbations resulting from individual turbines, wind farm projects, and regional-scale concentration of projects will be overlaid on the Nantucket Shoals Regional oceanography, which is already a highly dynamic and changing marine system. The major hydrodynamic impact of this activity could be on stratification and advection (i.e., drift). However, the scale of the hydrodynamic impacts of these activities are likely to be small compared to the ongoing climate-induced changes that are occurring in the Nantucket Shoals region (see Chapter 3). The ability to disentangle hydrodynamic impacts of wind development on the local ecosystem from large-scale climate dynamics will require the continuation of long-term ecological monitoring programs, the execution of fine-scale observational efforts to support ecological process studies, and the development of robust coupled hydrological–ecological models.

POTENTIAL IMPACTS TO THE PREY FIELD OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC RIGHT WHALE

Given the state of understanding of the effects of hydrodynamics on zooplankton supply, abundance, and aggregation, as well as uncertainties regarding how turbines will

affect the hydrodynamics of the Nantucket Shoals region, it is unclear how wind development will affect right whale prey availability in this region. There are mechanisms that could support an increase, a decrease, or no measurable change in right whale prey availability. Future research supporting observational studies and model development are needed to support accurate predictions.

Some studies show mechanisms that could cause turbines to increase zooplankton productivity and/or aggregate zooplankton into high-density patches to support right whale foraging. Reductions in wind stress at the air–sea interface caused by extraction of wind-driven kinetic energy at the turbine can cause an upwelling/downwelling dipole downstream of turbines that may change local primary productivity (Broström, 2008; Floeter et al., 2022; Raghukumar et al., 2023). Increases in turbulent mixing caused by currents flowing around individual monopiles may break down stratification and boost primary productivity (Carpenter et al., 2016; Cazenave et al., 2016). Reduced stratification may be associated with a community shift that is less favorable for smaller zooplankton taxa and more favorable for late-stage C. finmarchicus (Pershing and Kemberling, 2023). Because C. finmarchicus is an income breeder, increased concentrations of phytoplankton and microzooplankton may contribute to higher rates of egg production (Durbin et al., 2003; Runge et al., 2006). However, this potential mechanism is complex to connect to right whale foraging success in the area because right whales rely on adult stages of C. finmarchicus, and in the weeks required for C. finmarchicus to mature to adult stages (Marshall and Orr, 1972), the juvenile stages may be advected to a different region, boosting downstream abundances of right whale prey. High primary productivity may also contribute to feeding success of individual C. finmarchicus and increases in the lipid stores of individual zooplankton will increase the overall nutritional value of the right whale foraging area (McKinstry et al., 2013).

Wind turbines also have the potential to decrease zooplankton productivity and/or reduce the potential for high-density aggregations, thus potentially reducing foraging opportunities for right whales in the region. Sediment plumes caused by bottom disturbance at the turbine site may increase water turbidity, thus decreasing rates of primary productivity in the area (Vanhellemont and Ruddick, 2014). With less food available for C. finmarchicus, survival and reproduction may decline (Durbin et al., 2003; Runge et al., 2006). Increases in fish and invertebrate abundances and diversity have been detected around turbines, due to either attraction or production (e.g., Methratta et al., 2020; Perry and Heyman, 2020), which could expose late-stage C. finmarchicus to higher levels of predation. Reductions in current speeds at the scale of the wind farm (e.g., Christiansen et al., 2023) could potentially modify local zooplankton supply. Local increases in turbulent mixing resulting from drag forces downstream of the monopile (e.g., Rennau et al., 2012; Schultze et al., 2020) could disrupt zooplankton aggregations or induce avoidance behavior, thus reducing high-density patches of right whale prey (Incze et al., 2001; Visser et al. 2001). However, it is unknown whether any of these potential mechanisms for decreasing zooplankton abundance and aggregation could occur at a scale that affects right whale foraging efficacy.

A third possibility is that wind farm development will have no appreciable impact on right whale foraging dynamics. This may occur because the potential mechanisms

to increase and decrease zooplankton abundance and aggregation are mild and do not significantly alter prey availability, or these mechanisms may cancel each other out or be insignificant compared to ongoing climate-induced changes in the ecosystem. Coupled physical–biological processes, unrelated to wind energy development, may reduce or increase the abundance and density of right whale prey in the region.

Right whale use of this region as a foraging area is heterogeneous on seasonal, annual, and decadal scales, and although right whales have been foraging in the Nantucket Shoals region over the past decade, it is difficult to predict their future use of this area. Oceanographic and ecological processes may change the supply of zooplankton to the area, especially C. finmarchicus which is primarily advected into the region. Because right whales forage over a vast geographic area, their use of any particular region may be partially driven by conditions in distant regions, such as alternative foraging habitats. It is plausible that zooplankton abundances in historical high-use foraging areas such as the Bay of Fundy and Roseway Basin will rebound, or right whales will increase occupancy in a different region (as recently done in the Gulf of St. Lawrence); thus, right whales may shift away from the Nantucket Shoals region to forage in these more northern areas. Alternatively, declines in prey availability in remote foraging areas could cause right whales to increase their use of the Nantucket Shoals region. Climate change is responsible for shifting baselines in zooplankton abundance and right whale habitat use; thus, it will be difficult to disentangle the impacts of wind energy development from other anthropogenic and natural factors that affect right whale prey.

Given the uncertainty in the impacts of turbines on right whale prey availability, and thus right whale behavior, distribution, and demography, an important starting point is robust monitoring in order to understand the sign of potential impacts on this critically endangered marine mammal and to mitigate negative impacts. In addition to monitoring, modeling programs that couple the fine-scale physics with copepod biology and behavior are needed to better understand the processes of prey patch formation. Modeling will be challenging, because the processes necessary for patch formation span a wide range of scales, from supply (hundreds of kilometers) to fine-scale physics and behavior (1 cm to 10 m). There have been modeling studies that couple some of these processes at a variety scales (e.g., Pershing et al., 2009; Record et al., 2010; Ji et al. 2012; Bandara at al., 2018; Ross et al., 2023), as well as cross-scale observational studies of zooplankton patches (Robinson et al., 2021). Assembling the various modeling and monitoring components to address patch formation and dynamics around turbines will be challenging but should be feasible. These threats can be mitigated with a robust set of conservation measures designed to support National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) existing network of visual and real-time acoustic monitoring for right whale presence in the region year-round. These observations support NOAA’s existing dynamic management policy framework to slow vessel speeds and potentially re-route vessel traffic when right whales are in the region. Continued and robust monitoring of right whales’ presence and behavior, using multiple sampling modes and implemented across broad spatial scales, will be critical for regularly assessing these mitigation efforts (BOEM

and NOAA, 2022; Silber et al., 2023). This is especially important as right whale use of the Nantucket Shoals region evolves due to oceanographic changes and/or the activities and conditions relevant to wind farms.

Individual wind farm projects are also responsible for limited monitoring of the project’s impacts on right whales. For example, the Record of Decision and the Construction and Operations Plans for Vineyard Wind and South Fork Wind include a series of conservation measures related to potential interactions between right whales and wind farm activities. This provides for at least 3 years of deployment during and after construction of passive acoustic monitoring devices to monitor for the presence of right whales, stationing trained protected species observers on industry vessels, restricting vessel speeds to 10 kts (5 m/s) during times when right whales may be present in the wind farm areas, scheduling construction activities to occur only in summer and outside of the times when right whales are normally present in the wind farm areas, and scheduling regular inspections and cleanup around turbines to prevent the accumulation of lines and other debris around monopiles. Recent studies suggest that right whale distributions continue to evolve in this region (Quintana-Rizzo et al., 2021), which has implications for mitigating risk during construction and operation.

In a scenario where turbines increase the abundance and/or aggregation of right whale prey, increased right whale foraging in the Nantucket Shoals region may subject animals to increased risk of exposure to vessel strikes, entanglement in regional fishing gear, including gear that may aggregate around the base of the monopile, and anthropogenic noise. Alternatively, in a scenario where right whale use of the Nantucket Shoals region declines in response to turbine construction and operation, understanding of shifts in right whale foraging behaviors is essential for guiding future wind farm construction in other areas and predicting right whale use of alternative foraging grounds. In either scenario, visual monitoring and passive acoustic monitoring will be critical for characterizing the changes in habitat use and understanding the drivers of right whale decision making to search for and occupy foraging refugia. Although changes to the prey field are not likely to be significant enough to drive annual reductions in foraging success that decrease calving rates, understanding of foraging dynamics in this first large-scale wind energy site will provide critical information for planning future wind energy development to avoid population-level impacts.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Conclusion: The paucity of observations and uncertainty of the modeled hydrodynamic effects of wind energy development at the turbine, wind farm, and regional scales make potential ecological impacts of turbines difficult to predict and/or detect.

Conclusion: The hydrodynamic impacts from offshore wind development in the Nantucket Shoals region on zooplankton will be difficult to isolate from the much larger magnitude of variability introduced by natural and other anthropogenic sources (including climate change) in this dynamic and evolving oceanographic and ecological system.

Observations

Conclusion: Long-term zooplankton and whale monitoring programs have provided valuable information about right whale ecology and distribution.

Conclusion: The mechanisms that supply, transport, and aggregate right whale prey such as C. finmarchicus into suitable foraging habitat vary at temporal scales that range from hours to decades and spatial scales that range from the millimeter-scale size of the copepod to the size of an ocean basin.

Conclusion: There is a gap in understanding of foraging by North Atlantic right whales in the Nantucket Shoals region. This includes the very basic question of which zooplankton taxa right whales are feeding on in the region, and how this changes seasonally. Surveys of zooplankton associated with foraging right whales as well as simultaneous collection of ecosystem-level information about foraging whales would improve this understanding.

Conclusion: The spatiotemporal coverage of studies concentrated at wind farm areas does not adequately capture broad-scale right whale use of the Nantucket Shoals region and potential impacts from offshore wind turbines.

Recommendation: The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, and others should support, and where possible require, the collection of oceanographic and ecological observations through robust integrated monitoring programs within the Nantucket Shoals region and in the region surrounding wind energy areas before and during all phases of wind energy development: surveying, construction, operation, and decommissioning. This is especially important as right whale use of the Nantucket Shoals region continues to evolve due to oceanographic changes and/or the activities and conditions relevant to offshore wind turbines. Observations should

- Include concurrent measures of relevant physical processes and ecological effects through upper trophic levels at the turbine, wind farm, and regional scales.

- Be expanded to identify the links and relevant processes between zooplankton supply, abundance, and aggregation and right whale habitat use in the Nantucket Shoals region.

- Use combined observational and modeling studies to isolate potential effects of wind farms from those resulting from natural and/or other anthropogenic drivers, recognizing that this will take dedicated long-term studies.

- Sample zooplankton at the appropriate spatiotemporal scales necessary to characterize right whale prey availability, including zooplankton life history and behavior.

- Monitor right whale habitat use within and outside of wind energy areas.

- Maintain existing long-term monitoring programs to provide insight on regional and ocean-basin scale changes to right whales and their prey.

Modeling

Conclusion: Right whale distribution and demography has been shown to depend on the distribution and density of late-stage C. finmarchicus, both through prey-dependent reproduction rates as well as increases in the rates of anthropogenic-related mortality that occur with rapid prey-driven distribution shifts.

Conclusion: Right whale spatial distribution and demography are directly related to the distribution and density of their zooplankton prey including late-stage C. finmarchicus. However, studies focusing on the links between right whale habitat use and zooplankton in the Nantucket Shoals region are limited.

Conclusion: The supply of zooplankton to Nantucket Shoals is dependent on regional circulation, but aggregation is presumably dependent on local physical processes and zooplankton behavior.

Conclusion: There is currently a lack of robust (coupled physical–biological) models that can effectively incorporate the supply of zooplankton, their behavior, and the physical oceanographic processes that aggregate the zooplankton in the Nantucket Shoals region in sufficient densities for right whale foraging. Given this lack of models, it will be difficult to predict whether wind farm projects will have an impact on right whales.

Recommendation: The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, and others should support, and where possible require, oceanographic and ecological modeling of the Nantucket Shoals region before and during all phases of wind energy development: surveying, construction, operation, and decommissioning. This critical information will help guide regional policies that protect right whales and improve predictions of ecological impacts from wind development at other lease sites. This modeling should

- Include zooplankton life history and behavior modeled at appropriate scales.

- Identify and model the mechanisms that drive supply, abundance, and aggregation of zooplankton.

- Utilize improved hydrodynamic models that represent the mechanisms that drive regional transport, supply, and local aggregation processes.

- Be expanded to identify and incorporate the link between zooplankton supply, abundance, and aggregation and right whale habitat use in the Nantucket Shoals region.

- Be conducted at the appropriate spatiotemporal scales necessary to isolate effects driven by wind turbines from those resulting from natural and/or other anthropogenic drivers.

- Incorporate physical and ecological information pertinent to right whale foraging outside of the Nantucket Shoals Region, because right whale foraging in this region may depend on the availability of alternative foraging areas.

This page intentionally left blank.