Potential Hydrodynamic Impacts of Offshore Wind Energy on Nantucket Shoals Regional Ecology: An Evaluation from Wind to Whales (2024)

Chapter: 3 Hydrodynamic Effects of Offshore Wind Developments

3

Hydrodynamic Effects of Offshore Wind Developments

STATE OF UNDERSTANDING

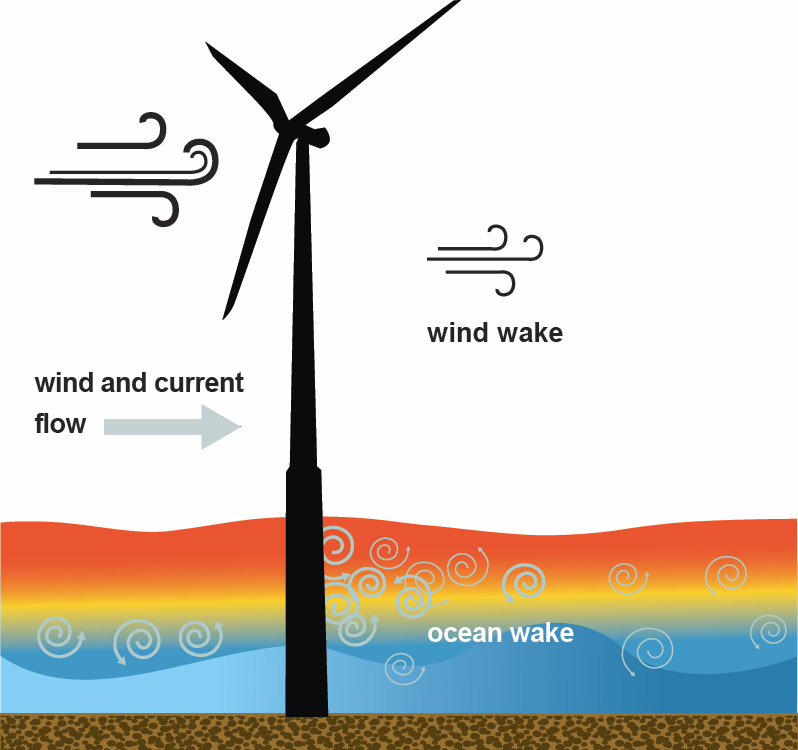

The potential effects of offshore wind turbines on the ocean can be due to the physical presence of the structures across the water column and from the effects of wind energy extraction on wind-driven ocean circulation (Figure 3.1). The impacts of offshore wind energy installations on coastal and oceanic environmental conditions and habitats have been examined in terms of the effects on bottom stress, turbulent mixing, along- and cross-shelf transport, and wind stress curl-effects of offshore wind turbines on the hydrodynamics and subsequent physical and biological systems, a substantial amount of information has been gleaned from studies done for European driven (Ekman pumping) upwelling due to vertical motion arising from Ekman divergence. Although there are still significant knowledge gaps in understanding the potential offshore wind farms. However, despite the knowledge base from European waters, there are substantial and significant differences in both the oceanography and the wind farm structures and geometries so that a simple transfer of results is not possible.

THE CASE OF THE NORTH SEA: HYDRODYNAMICS

The North Sea, a shallow (mean depth 80 m) shelf sea in northwestern Europe, accounts for more than 75 percent of offshore wind energy capacity in European waters as of 2021 (WindEurope, 2022). The London Array1, a wind farm that spans 100 km2 and became operational in 2013, sits on two natural sandbanks in depths of 25 m. This site was chosen because of its proximity to onshore electric power infrastructure and dis-

___________________

1 Details and specifications for the London Array are provided in Olabi, et al., 2023.

tance away from main shipping lanes in the area. Other wind farms, including Thanet2 and the northern half of Greater Gabbard, span 147 km2 and are at depths of 24–34 m. These turbines were built to take advantage of the fast-blowing winds over the North Sea’s surface (NASA, 2015). Geyer et al. (2015) provided a comprehensive overview of the wind power potential and variability in the North Sea based on simulated wind speed data from 1958 to 2012 and an assessment of the thermal effects on estimates

___________________

2 Details and specification for the Thanet and Greater Gabbard Arrays are provided in Higgins and Foley (2014).

of wind power potential. They found that wind energy potential was largest during the 1990s and 2000s and interannual and decadal variability is an important consideration for offshore wind energy. Therefore, the North Sea’s strong winds and shallow shelf made it an ideal location for offshore wind farm construction.

Shelf seas are dynamic environments subject to seasonal heating, atmospheric fluxes, river inputs, and open ocean exchange and are strongly influenced by tidal motion (Cazenave et al., 2016). The North Sea waters can be strongly stratified in the summer with a warm nutrient-deficient upper ocean layer overlying a cool nutrient-dense layer at depth. This steep temperature gradient inhibits the exchange of nutrients, oxygen, and phytoplankton. Mixing of these two layers occurs during certain times of the year when air temperatures drop and vertical stratification weakens, resulting in an almost homogeneously mixed water column during winter in extensive shallow regions (van Leeuwen et al., 2015). When deep, nutrient-rich water mixes with surface water, primary production increases (Gronholz et al., 2017).

The presence of offshore wind farm foundations will lead to enhanced turbulent mixing in a downstream wake. This increased mixing occurs in addition to naturally occurring turbulent mixing processes that act on stratification (Schultze et al., 2017, 2020; Christiansen et al., 2023). Seasonal stratification is known to reduce vertical fluxes, which control nutrient transport to the upper layer and increase primary production. Vanhellemont and Ruddick (2014) analyzed high-resolution imagery in the London Array and found a significant increase in suspended sediments in the wakes of individual turbine monopiles. The plumes were observed to be 30–150 m wide and extended 1 km or more downstream. The spatial extent of the plume effect produced by the turbines was extensive, highlighting the need for further research.

The effects of an offshore wind turbine array in the North Sea on waves, sound, and biogeochemistry were modeled by van der Molen et al. (2014). The effects of the turbines on biogeochemistry were modeled through a constant 10 percent reduction in wind speed within the wind farm area. However, the turbine-structure wake effects were not included in the analyses, and sensitivity studies of the parameterization used to specify changes in wind speed were not done. The simulations of biogeochemical effects showed that wind turbines can result in about an 8 percent increase in net primary production, with an associated reduction in nitrate concentrations of 6 percent and a 3 percent increase in chlorophyll concentration. This had cascading effects throughout the trophic system, including increased sinking of particulate material, resulting in an increase of 35 percent and 20 percent in phytoplankton and zooplankton and an increase in food sources for benthic suspension feeders. Overall, these simulation results suggested relatively weak environmental changes, with most of the changes occurring within the wind turbine array and smaller changes occurring several tens of kilometers outside the wind energy array.

Daewel et al. (2022) used a high-resolution atmospheric model to force a coupled physical–biogeochemical model configured for the North Sea and the Baltic Sea. Their simulations provided evidence that increasing the amount of future offshore wind installations will change stratification intensity and pattern, slow circulation, systematically decrease bottom shear stress, and alter primary production. While regionwide averages

in estimated annual primary production remained almost unchanged, there were local increases and decreases to primary production of up to 10 percent. Carpenter et al. (2016) created ad hoc idealized models to estimate stratification changes given a mixing rate from offshore wind structures and the residence time of a water parcel within a wind farm. The models showed increases in ocean mixing within a wind farm. However, the analyses indicated that extensive regions of the North Sea must be covered with offshore wind turbines to produce a significant impact on stratification, and a wind farm of the required size has yet to be installed. Cazenave et al. (2016) expanded on this work by including an additional 242 offshore wind turbine monopiles and simulating the effects on seasonal stratification of the United Kingdom shelf with an emphasis on the Irish Sea. The result was increased mixing and decreased stratification. Even though these monopiles are less than 20 m in diameter, their effect was detected over areas of approximately 250 km2 (Cazenave et al., 2016).

Ocean Effects

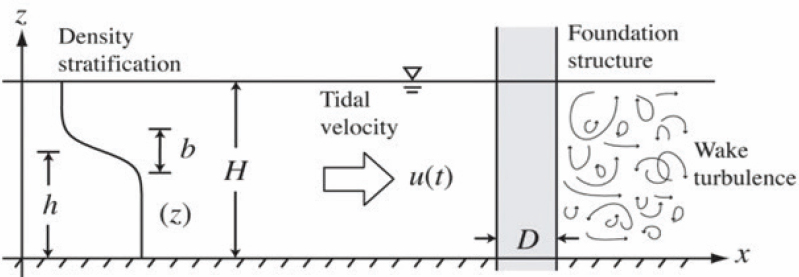

The physical presence of wind turbines acts as a barrier to hydrodynamic flow around which a baseline flow (no turbines) must pass, as well as a source of additional turbulent mixing (Figure 3.2, left panel). Miles et al. (2021) summarizes existing laboratory and modeling studies that describe the influence of turbine-induced ocean wakes on downstream hydrodynamics. Laboratory (Miles et al., 2017) and numerical modeling studies (Carpenter et al., 2016; Cazenave et al., 2016; Schultze et al., 2020) focused on monopile structures similar to the structures planned for wind farm deployment in the Nantucket Shoals region. These studies concluded that the magnitude and extent of the turbine’s impact varies depending on the magnitude of the existing ocean currents, including subtidal and tidal flows around the structure, the strength of stratification, and the turbine structure geometry and farm layout. Miles et al. (2017) showed that at the individual turbine scale, the peak turbine-induced turbulence occurs within one monopile diameter of the structure, with weaker downstream effects extending 8–10 monopile diameters. This scale of direct influence is confirmed with high-resolution numerical modeling, with modeled turbulence impacts extending up to 100 m downstream of an individual turbine (Schultze et al., 2020). As noted in the previous section on the North Sea case study, the scale of impacts on other environmental variables, such as temperature and suspended sediment, has been found to extend up to 1 km from the turbine structure (Vanhellemont and Ruddick, 2014; Schultze et al., 2020). Using an idealized one-dimensional mixing parameterization, Carpenter et al. (2016) estimated that the impact of offshore wind turbines on the duration of typical North Sea seasonal stratification was uncertain. Variations in the turbine structure geometries and layouts alone could produce a factor of 4.6 difference in the expected turbulence production. Combining this uncertainty with the different possible evolutions of the stratification under turbine-enhanced mixing produced mixing rates capable of eroding typical summer stratification in the wind farm region as rapidly as 37 days and as long as 688 days, values that are shorter and significantly longer than the typical length of seasonal stratification in this region of ~80 days. This variability in the turbulence-induced mixing is dependent on the magnitude of the water velocity moving

past the turbine, the strength of stratification and its evolution under turbine-enhanced mixing, and turbine structures and farm layouts.

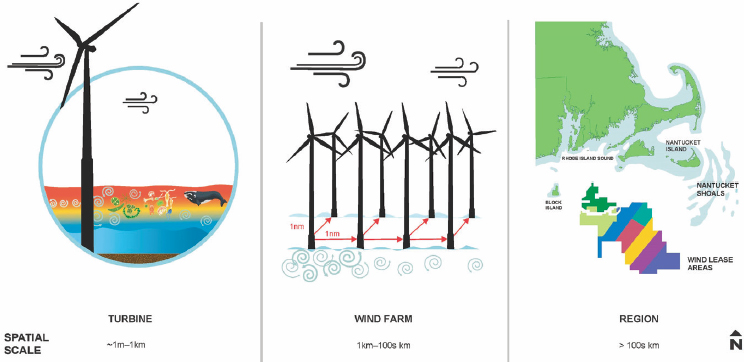

The cumulative impact of multiple turbines on hydrodynamics is dependent on the relative scales of developed and undeveloped areas (Figure 3.2, middle and right panels). Using an unstructured grid model, Cazenave et al. (2016) expanded results for an idealized single turbine to an entire farm of turbines and found a localized weakening of stratification of about 5–15 percent of simulated seasonal stratification, consistent with previous results. Carpenter et al. (2016) extended these results to a larger geographic region and included advection estimates that restore seasonal stratification in the absence of turbines. This analysis showed that physical oceanographic forces can counteract the effect of wind farm–induced mixing when wind farm area coverage is small relative to the shelf region. Application of laboratory and modeling results from the North Sea to the Nantucket Shoals region must account for differences in the timing and intensity of site-specific ocean processes. These processes include differences in currents, winds, and tides; changes in surface density; and the influence of salt intrusions related to the presence of Gulf Stream warm core rings offshore as described in Chapter 2 (Nantucket Shoals region) and earlier in Chapter 3 (North Sea). Depending on the season and location of the study, ocean conditions within the Nantucket Shoals region are likely to vary from those conditions observed and modeled in the North Sea. Additionally, the impact of turbine-induced ocean wakes on stratification must be evaluated within the context of these shelf-wide physical forces specific to the Nantucket Shoals region that affect seasonal stratification. An important additional difference between results for the North Sea and the Nantucket Shoals region is the wider spacing

of the turbine structures in the Nantucket Shoals. This is expected to result in a lower concentration of hydrodynamic impacts, other factors being equal (e.g., foundation structure geometry).

Atmospheric Effects

In addition to changes in mixing due to the physical presence of the turbine foundations (monopiles or jackets), wind-driven ocean circulation can potentially be affected via reductions in wind stress at the sea surface due to reduced wind speeds in the lee of a turbine. Since each turbine acts as a momentum sink and source of turbulence, energy extraction from the ambient wind field results in reduced wind speeds downstream of a turbine (Figure 3.1). The theoretical maximum efficiency of a turbine has been found to be ~59 percent (known as the Betz Limit; Betz, 1966), and modern offshore wind turbines extract ~50 percent of the energy from the wind that passes through the rotor area (DOE, 2015), subject to a cutoff wind speed above which wind energy extraction reaches a saturation limit. The maximum reduction in wind speeds is at hub height (in the range of 118 m to 152 m; Beiter et al., 2020), with a decay in the wind speed reductions above and below hub height. Xie and Archer (2015) modeled the horizontal and vertical structure of wind turbine wakes and found that while the largest reductions in wind speed are at hub height, the vertical extent of the region of wind speed reductions begins to extend down to the sea surface within a horizontal distance of 8 rotor diameters. Further, wind speed reductions at a height of 10 m above the sea surface become more pronounced with distance from the turbine. At the scale of an offshore wind farm, wakes have been observed over several tens of kilometers downstream of the wind farm under stable atmospheric stratification conditions (e.g., Christiansen and Hasager, 2005; Platis et al., 2018). Additionally, model studies of the atmosphere have generally reproduced (with respect to measurements) the wake effect several tens of kilometers downstream of a wind farm (Fischereit et al., 2021). The use of remote sensing techniques also offers the potential for additional validation exercises of modeled wind farm wakes (Djath and Schulz-Stellenfleth, 2019). In the North Sea, Duin (2019) examined wind stress reductions for a large offshore wind farm and reported that typical wind speeds at 10 m above the sea surface are reduced by up to 1 m/s, while other effects were observed on air temperature (increases and decreases at various locations around the wind farm), relative humidity (decreases above the wind farm), and shortwave radiation (decreases near the wind farm).

Ocean circulation processes such as upwelling or downwelling are influenced by wind stress at the sea surface when the spatial scales of wind forcing approach or exceed the internal Rossby radius of deformation (in the range of 7 km at the latitudes of Nantucket Shoals). Therefore, although the wake behind a single standalone turbine is unlikely to affect wind-driven circulation, wind stress changes from an offshore wind farm array could occur over spatial scales large enough that wind-driven ocean circulation (e.g., upwelling/downwelling) can be influenced (Figure 3.2).

Several studies have examined the effects of offshore turbines on wind-driven ocean circulation. Most of these studies have focused on the North Sea (see previous

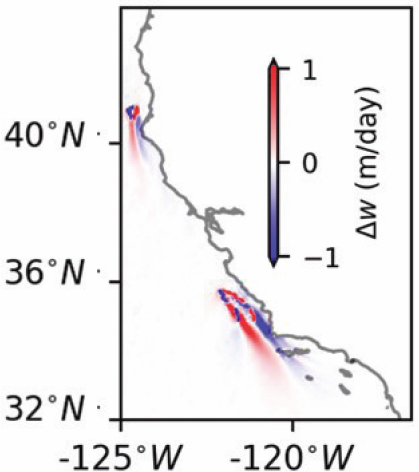

section), while studies with a reduced scope (atmospheric circulation, larval transport studies and upwelling circulation) have been executed on the U.S. East and West coasts. The effect of wind stress reductions on ocean circulation (upwelling/downwelling) were examined using an analytical framework that showed the presence of a wind stress curl-driven upwelling/downwelling dipole (Figure 3.3) in the lee of offshore turbines (Broström, 2008). The relation between coastal upwelling and wind farm size was examined by Paskyabi and Fer (2012), and Paskyabi (2015), who found that wakes increase the magnitude of pycnocline displacements, and in turn, upwelling/downwelling. A recent observational study conducted by Floeter et al. (2022) found the occasional presence of a curl-driven upwelling/downwelling dipole in the vicinity of a wind farm in the North Sea, similar to what was modeled for hypothetical wind farms in the California Current System by Raghukumar et al. (2023). A coupled physical–biological model implemented by Daewel et al. (2022) examined the effects of wind energy extraction by turbines in the southern North Sea and found changes in modeled primary production over a much larger area. While the appearance of an upwelling/downwelling dipole is justified by a clear, mechanistic understanding of the underlying physics, the appearance of changes (e.g., Daewel et al., 2022; Raghukumar et al., 2023) in other tracer fields, far from the wind farm areas requires further study, particularly from the point of view of understanding whether these changes are driven by numerical noise in instantaneous wind forcing or if there are indeed mechanistic processes that drive changes far from the wind farms.

ABILITY TO ACCURATELY AND PRECISELY ESTIMATE PERTURBATIONS CAUSED BY WIND TURBINE GENERATORS

In examining the potential hydrodynamic perturbations caused by offshore wind energy installations it is helpful to consider three natural length scales (Figure 3.2): (1) the turbine scale, which covers the near-field response of individual structures; (2) the wind farm scale, which is representative of individual farms where individual turbine-scale responses are expected to have either merged or are averaged into a scale that is comparable to the size of the farm; and (3) larger “regional” scales, which encompass the full extent of the perturbations as well as the regional-scale features of the oceanographic environment.

Turbine Scales

On the turbine scale, alterations in the hydrodynamics are produced through the generation of a turbulent wake as ocean currents flow past the turbine structure foundations (Figure 3.4). The wake is the hydrodynamic signature of the extraction of momentum by the drag force on the foundation structure, as well as the production of turbulence (i.e., turbulent kinetic energy [TKE]) through instabilities in the highly sheared viscous and turbulent boundary layers on the structures themselves. An approximate largest scale that defines the range of “turbine-scales” is on the order of 1 km, corresponding to the approximate turbine spacing in many existing farm layouts. This order of 1-km effect comes from observations of (a) sediment plumes (Vanhellemont and Ruddick, 2014; Förster, 2018), and (b) detectable alterations in stratification (Schultze et al., 2020), as well as turbulence-resolving (large eddy simulation [LES]) modeling of the stratification (Schultze et al., 2020). Defining a wake length is, however, dependent on

the hydrodynamic quantity under consideration. For example, quantities that describe the turbulence, such as the dissipation rate of TKE or the turbulent buoyancy flux, represent localized wakes around the structures (Rennau et al., 2012; Schultze et al., 2020), with the wake signatures dissipating to the levels of background conditions within a couple hundred meters, compared to the 1-km and greater scales seen in the suspended sediment wakes (Vanhellemont and Rudick, 2014) and in the temperature wakes (Schultze et al., 2020). These differences arise from the different processes governing the dissipation of the wakes, such as turbulence decay versus sediment settling.

To evaluate the ability of existing approaches to accurately and precisely estimate turbine-scale wake perturbations, two methodologies can be applied: (1) a confident baseline can be identified, and each approach validated against it; or (2) two different and independent approaches can be compared against one another. The obvious choice for a confident baseline, identified in multiple studies (e.g., Rennau et al., 2012; Carpenter et al., 2016; Jensen et al., 2018; Schultze et al., 2020; Dorrell et al., 2022), is the classic drag law of a circular cylinder in a uniform, unstratified cross flow. This empirical “law” makes predictions for the extraction of momentum and the production of TKE that can be expected by a simple monopile structure in the idealized setting of an unstratified and uniform flow. Although both conditions are generally not satisfied in the coastal ocean, this drag law nonetheless represents a useful baseline. Despite the oversimplified formulation of the drag law for coastal ocean flows, it has been found to hold also in flows with current shear, a turbulent approach flow, and stratification, with drag coefficients within the classical range of variability (Schimmels, 2007; Jensen et al., 2018; Schultze et al., 2020). Values reported for the drag coefficient, obtained through LES modeling and laboratory experiments, are in the expected range (approximately 0.3–1.2) in the study of bridge piers with 0.3–0.8 (Jensen et al., 2018), and at 0.7 for a monopile in sheared, stratified flow (Schultze et al., 2020). However, not even the high resolutions of LES can be expected to consistently capture the physics of boundary-layer separation unless special care is taken close to the structure boundary (e.g., Janssen et al., 2018). The LES approach is therefore problematic when used as a strict test of the drag law. However, particularly in the case of turbine-scale modeling, comparison with the drag law provides a rough validation check that the turbulent momentum and energy fluxes are captured correctly (Rennau et al., 2012; Janssen et al., 2018; Schultze et al., 2020); a recommended step in the validation of the turbine-scale hydrodynamics. The drag coefficient is a function of Reynolds number and surface roughness (among other variables), and values above unity can also be expected (Carpenter et al., 2016), leading to a large range of variability.

Complications in applying the drag law directly to turbine-structure momentum and TKE sinks and sources do arise additionally from unknowns in the hydraulic response of the flow stratification (Dorrell et al., 2022; particularly when internal wave speeds are close to the speed of flow past the structure) as well as any possible biofouling on the structures themselves. The biofouling will likely play a similar role as an increased surface roughness, which has been found to increase drag coefficients on circular cylinders to the saturated high Reynolds number value of approximately unity. However, this correspondence of biofouling to surface roughness is not exact and almost certainly

depends on the type of growth on the structures. Biofouling therefore contributes to the uncertainty in determining the drag coefficient. Additionally, some turbine structures have complex geometries that make application of the drag law problematic (e.g., Carpenter et al., 2016), and there are expected to be differences between monopile foundations and other foundation types in momentum extraction and turbulence production. These effects will enter through the changed frontal area of the structure (an input parameter to the drag law) and drag coefficient. To properly account for these effects, specifically designed experiments or simulations must be performed (e.g., Jensen et al., 2018, in the case of bridge piers).

In addition to the use of LES modeling of the turbine-scale hydrodynamics, Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) modeling of the wake has been performed (Schimmels, 2007; Rennau et al., 2012). This technique has the advantage of faster computation, allowing for a larger exploration of parameter space; however, larger inaccuracies can be expected due to the greater reliance on parameterizations of the structure-induced turbulence, with a potentially large difference in results (Schimmels, 2007). The highly localized scales of the turbine-scale wakes require careful attention to ensure a validated representation in regional-scale models.

When no established baseline, such as a drag law, is available, confidence in the accuracy of existing approaches can be estimated by a comparison of two independent methods. This was the approach taken by Schultze et al. (2020) in comparing the density structure of a single monopile wake both from observations of a towed chain of conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) sensors and from LES modeling of the wake stratification. The comparison seemed to show qualitative agreement in the dependence of the wake on background stratification, and in the geometry of the wake; however, the comparison was limited by the difficulty in separating the observations of the wake from the natural background variability as well as the low confidence that necessarily accompanies a single observation of a turbulent flow. In conditions of stronger stratification, no wake could be identified from the observations (Schultze et al., 2020).

Significant uncertainties are associated with estimations of the hydrodynamic responses of the ocean wakes at the turbine scale. Process-based studies that are designed with narrowing of these uncertainties as an explicit objective are needed to accurately and precisely estimate hydrodynamic effects of turbines. There are also very few observational studies for “ground truthing” that can be used to verify turbine-scale wake behavior. Such observations will have to overcome the challenge of separating the turbine-structure effects from those of natural variability.

Wind Farm Scale

The wind farm scale represents the turbine arrays that are often constructed with a relatively tight (compared to the distance between adjacent arrays) spacing of turbine structures, and usually with identical foundation structure types (e.g., monopile) and geometries (e.g., hub heights). These areas can vary widely, but generally have length scales on the order of 10–100 km. Impacts of the turbine structures over the wind farm scale can arise through integrated local (turbine-scale) effects from the individual

turbine structures arising from both the atmosphere and ocean wakes. Over this scale, the turbine wakes will possibly have merged with the background conditions to have created a coherent perturbation that may, or may not, be identifiable from the natural background environment. Such wind farm–scale effects identified in the literature include:

- A reduction in ocean current speeds resulting from the increased frictional drag within the wind farm area (Christiansen et al., 2022).

- A reduction in the stratification in a region roughly consistent with the wind farm area (Carpenter et al., 2016; Floeter et al., 2017; Christiansen et al., 2023).

- A “doming” of the pycnocline within the wind farm area, bringing it closer to the ocean surface (Floeter et al., 2017).

- Ocean surface wind speed reductions focused closely within the wind farm (Golbazi et al., 2022).

Some of these effects may interact with one another. For example, it is important to be able to predict the advective transport of stratification by mean currents, and the possible alterations by ocean wake effects through reduced current speeds, in order to accurately predict impacts to the stratification. However, the evidence found for each of these effects is discussed independently below.

Current speed reductions, as well as altered current directions, represent one possible effect arising from the increased frictional drag forces within the wind farms. Christiansen et al. (2023) conducted a regional modeling study of such effects in the southern North Sea and found small changes in residual mean current speeds (i.e., after averaging out the dominant tidal currents) of approximately 2 mm/s, a speed that represents roughly 10 percent of natural mean currents in this area. This modeling study parameterized the additional friction through the drag law. An alternative approach that aimed at resolving the turbine-scale ocean wakes through a locally enhanced grid around the structures was found to be problematic and inaccurate. The wind farms were simply represented as uniform patches of increased friction and turbulence in accordance with the drag law formulation. Such estimates of alterations in mean residual (i.e., over longer timescales as tidal flows) currents due to ocean wake effects are fairly well supported and suffer uncertainty only in the uncertainty of the application of the drag law, as discussed for turbines in the previous section. Note, though, that there could be significant effects from altered wind speeds on the ocean currents that were not accounted for in the Christiansen et al. (2023) study. Another aspect of the dynamics that could play a role in the ability to estimate perturbations to currents is in the uncertain mixing of the stratification on the wind farm scale, which can lead to current changes through baroclinicity.

Using wind farm–scale observations obtained from a profiler towed through two different wind farms in the southern North Sea, Floeter et al. (2017) found the likely presence of stratification changes within the wind farm areas. A comparison to the predictions of the idealized ad hoc modeling of Carpenter et al. (2016) showed reasonable agreement but, because of uncertainties in the drag coefficient, have a range that

differs by a factor of three (Floeter et al., 2017). However, separating the wind farm processes from the natural variability of the background environment was difficult, and a fortuitous transect through one of the same wind farms examined in the Floeter et al. (2017) study before the presence of turbine structures also showed a drop in stratification, albeit smaller than the drops after turbine installation. Christiansen et al. (2023) then used the Floeter et al. (2017) and Carpenter et al. (2016) studies as a benchmark for the regional modeling of stratification changes. Such a benchmark should not be considered a validation because of the large range of uncertainties as well as extremely limited coverage of the required relevant parameter space. The essential quantity required by the Christiansen et al. (2023) regional model is some measure of the bulk mixing efficiency, which expresses the amount of mixing (i.e., changes in the buoyancy field) for a given input of energy (called “production”) to the turbulence of the wakes. The turbulence production is relatively well known through the drag law (with the complications discussed above), but the mixing efficiency is not. This crucial unknown mixing efficiency must come from turbine-scale, turbulence-resolving studies such as LES (Janssen et al., 2018; Schultze et al., 2020) or RANS (Schimmels, 2007; Rennau et al., 2012) simulations, or laboratory experiments (Janssen et al., 2018), or from field observation (likely together with one of the above types of studies, e.g., Schultze et al., 2020). Although the studies by Janssen et al. (2018) and Schultze et al. (2020) report similar values of the bulk mixing efficiency (ranging from 0.05–0.24 and 0.09–0.14, respectively), they cover a limited parameter range and an idealized uniform-approach flow. Much more work using more realistic coastal flows is needed to improve confidence in these estimates.

Floeter et al. (2017) also observed a “doming” of the pycnocline position within some of the wind farm observational transects, wherein the pycnocline stratification was drawn closer to the ocean surface. Although similar effects could be seen in the Christiansen et al. (2023) study, they were not consistently present. The doming effect remains to be explained and quantified, and it is unclear if it is a robust feature of the wind farm–scale hydrodynamic response.

Wind speed deficits have been found at hub height within wind farms through modeling and observational studies (Platis et al., 2018; Golbazi et al., 2022; Raghukumar et al., 2022). There has been considerable research on atmospheric wakes (e.g., the review by Stevens and Meneveau, 2017); however, the focus of this research has been on understanding flow features at the hub height. Extrapolating the atmospheric-wake flows to the ocean surface remains an uncertain exercise. Observations in the North Sea have shown that the atmospheric wakes can extend to the sea surface and be felt many tens of kilometers to the lee of the wind farms (Hasager et al., 2015; Platis et al., 2018). The horizontal extent of the wake at the sea surface was found to depend strongly on the atmospheric stability (Platis et al., 2018). Golbazi et al. (2022) considered larger hub heights (>100 m) and turbine rotor diameters (>170 m) and found that the wind speed deficit at the sea surface is at most 10 percent of the freestream value. This agrees with the parameterization used by Christiansen et al. (2022) for the lower-hub-height turbines in the North Sea (<100 m) with a maximum wind speed reduction of 8 percent.

Regional Scale

Perturbations to mesoscale circulation due to the presence of wind turbines (such as through changes to upwelling/downwelling and an increase/decrease in eddy kinetic energy within the wind farm areas) can potentially propagate to a regional scale through mechanisms that lead to offshore propagation of mesoscale eddies (Strub and James, 2000). The propagation of eddy variability is influenced by the mean background flow, shape of bottom topography, or energetic features such as coastal jets (Fu, 2009), all of which are prevalent in the Nantucket Shoals region. Most regional-scale models have the ability to propagate mesoscale and submesoscale eddy variability (e.g., Capet et al., 2008), once these are modeled within a smaller region. However, although it is theoretically conceivable that changes to ocean circulation within a wind farm region can potentially propagate out to regional scales, the difficulty arises in being able to quantitatively assess this regional-scale perturbation.

Perturbations due to turbines at the regional scale are more difficult to quantify because the processes responsible for significant environmental variability encompass short timescales of hours, days, and weeks to longer scales of seasons, years, and decades. These regional-scale processes, discussed in Chapter 2 and relevant to the Nantucket Shoals region, include

- Tidal currents that spatially vary and can drive spatially dependent mixing that leads to horizontal fronts.

- Seasonal changes in stratification that vary in timing and strength across the region.

- Interactions with highly variable offshore Gulf Stream warm core rings that can shift the location of the shelf-break front and frequency and extent of mid-water salinity intrusions.

- Oceanic events that range in scale from the response of coastal and tropical storms to season-long oceanic heat waves.

- Decadal-scale trends in ocean warming, surface ocean freshening, and changes in ocean circulation.

Assessing offshore wind turbines’ effects at a regional scale requires observations and analyses that can account for and isolate turbine-generated perturbations from those produced by regional-scale processes. Similarly, modeling studies with and without turbines must assess perturbations relative to the other sources of variability represented in the model. The ability of a particular analysis to properly quantify a regional-scale, turbine-induced perturbation requires an experimental design that properly accounts for the significant contribution of natural variability from event to multidecadal scales.

Finally, given the relatively small scale of perturbations relative to the background mean circulation, the effects of numerical noise in both oceanic and atmospheric circulation models must be considered and mitigation steps taken to ensure that there is no misinterpretation of results. One example of numerical noise has been documented in the atmospheric model, Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF; Ancell et al.,

2018) with perturbation experiments that resulted in rapid propagation of errors into the model domain. When used in the absence and presence of wind farms to force an ocean circulation model, these small changes can potentially introduce spurious circulation effects that must be accounted for and mitigated against. Mitigation of numerical noise can be accomplished by averaging across long-time-duration simulations and by using sensitivity studies to determine adequate time durations over which to conduct model simulations.

APPLICABILITY OF HYDRODYNAMIC MODELS TO THE NANTUCKET SHOALS REGION

As detailed in Chapter 2, ocean circulation in the Nantucket Shoals region consists of complex processes that cascade from climatic forcing leading to a mesoscale/submesoscale response which in turn results in an ecosystem response. Mesoscale and submesoscale shelf-break processes in this region range from the presence of offshore warm core rings, wind-driven coastal jets, detachment and subsequent upwelling of the bottom boundary layer, subsurface intrusions, and the presence of a seasonal pycnocline, all of which are accompanied by mixing and nutrient exchange. Reliable predictions about any potential changes to hydrodynamic circulation from the presence of offshore wind farms requires that the range of shelf-break processes that drive nutrient delivery and exchange to the Nantucket Shoals region be accurately represented.

The differences obtained for the effects of turbines on hydrodynamics in the modeling studies by Chen et al. (2016, 2021a) and Johnson et al. (2021) arise from differences in spatial scales, temporal resolutions, and wind farm build-out scenarios considered by each model. These differing results underscore the need for a baseline model (no turbines) that is capable of accurately representing and simulating

- The regime shift in shelf-break circulation starting in 2010 that coincides with right whale presence in the Nantucket Shoals region,

- Seasonal and interannual variation of stratification on the shelf, and

- Warm core ring water masses and the shelf-break front that lead to nutrient fluxes from offshore waters to the shelf.

All of these play an important role in driving nutrient fluxes and prey aggregations that can lead to right whale presence in the region.

Modeling of the regime shift in the shelf-break circulation is within the realm of commonly used regional-scale eddy-resolving models such as Danish Hydraulic Institute water modeling and simluation software (DHI-MIKE), 3 Flexible Mesh (FM), Delft3D FM, Finite-Volume Community Ocean Model (FVCOM), and the Regional Ocean Modeling System (ROMS), described in more detail below. However, the representation of spatiotemporal variability in stratification requires inclusion of processes such as surface heating and cooling and flows along complex bathymetries that operate on multiple scales that have implications for subsurface nutrient exchange across the shelf break. The representation of mid-water slope water intrusions in any model needs careful consideration during

model validation, particularly since the accuracy of this representation is sensitive to mixing parameterizations that can mix out the signal of the plume.

The choice of models is governed by the processes and scales that are of specific interest. The accurate representation of fine-scale, stratification-related processes is typically more suited to models that do not make the hydrostatic assumption, particularly when resolving hydrodynamic features in which the vertical momentum is of the same order as the horizontal momentum. Examples of these processes include convectively unstable buoyant overturns (e.g., cooling of surface waters), short internal gravity waves, or eddies arising from shear instabilities. These processes affect the numerical results only when the model horizontal grid resolution is very small, that is, on the order of meters. The advantage of a nonhydrostatic model for simulating the fine-scale vertical structure is that it can potentially demonstrate the impacts of turbines on seasonal stratification. A disadvantage is that the accurate reproduction of the vertical structure of the flow requires extensive work to calibrate the vertical turbulence closure scheme as well as high computational cost.

Once a baseline hydrodynamic model has been calibrated, validated, and shown to reproduce key features associated with local and regional circulation (such as those listed above), turbines can be introduced into the simulation to study the effects of mixing around the turbine and from reduced wind stresses in the lee of the wind farm area. Modeling wind stress reductions can be achieved using various models with varying complexity and accuracy. Typically, wind stress reductions (i.e., the wind wake) are modeled using either a parameterized engineering model (e.g., PyWake; Pedersen et al., 2023), more complex atmospheric circulation models (e.g., WRF with wind farm parameterizations [Fitch et al. 2012; Volker et al., 2015]) or LESs (e.g., Simulator for Wind Farm Applications [SOWFA; Churchfield et al., 2012]). Modeled wind fields at 10-m height above the sea surface then provide surface-forcing fields for ocean circulation models. Each of the above models has its relative advantages and disadvantages, and their use depends on the specific processes and scales of interest. For example, PyWake is a computationally efficient method to obtain wake structures that has several wake models as options, including the ability to provide custom wake models, but lacks the ability to explicitly model wake interaction, as might occur in a wind farm. On the other hand, an LES might provide very-high-resolution wake structure (on the order of a meter or less) but can be computationally prohibitive to model wake structures on the scales of 100 km for input to a regional ocean circulation model. To date, the WRF model appears to be the most widely used (e.g., Daewal et al., 2022; Raghukumar et al., 2023) to provide surface forcing fields for ocean circulation models because of their ability to model wake structures (including wake interactions) at the mesoscale and has been validated performance against measurements (Fischereit et al., 2021). Atmospheric forcing fields for an ocean model can be provided as a one-way forcing field (i.e., the effect of varying ocean surface roughness on the lower atmospheric boundary layer is not explicitly modeled) or via a two-way fully coupled model (e.g., Alves et al., 2018). However, at this time, the need for two-way coupling for wind farm applications has not been specifically demonstrated.

HYDRODYNAMIC MODELS FOR SHELF AND COASTAL OCEANOGRAPHY

Most of the existing three-dimensional (3D) hydrodynamic models implemented to simulate large-scale oceanographic processes in coastal and shelf regions are based on the same governing equations, the RANS equations for an incompressible flow under the assumptions of hydrostatic pressure and Boussinesq approximation. Vertical acceleration due to the fluid motion is thus neglected in the vertical momentum equation. Turbulence closure schemes are required to determine the eddy viscosity for the Reynolds stresses in the RANS equations. Turbulence-induced vertical mixing of horizontal momentum, mass, and heat is modeled by vertical eddy viscosity and eddy diffusivity coefficients. Assumptions are made to relate the magnitude of the coefficients to the scales of velocity and mixing length as determined by various turbulence closure schemes. Although nonhydrostatic ocean models have been developed (e.g., Fringer et al., 2006; Kanarska et al., 2007; Lai et al., 2010), typical applications are limited to surface waves and internal waves or rapid-varying flows with large hydrodynamic or bathymetric gradients.

Examples of RANS models include DHI-MIKE 3 FM, Delft3D FM, FVCOM, and ROMS (Table 3.1). The first three models have been used in BOEM-funded environmental impact statement (EIS) analyses or studies in conjunction with U.S. Atlantic WEAs that include the Nantucket Shoals region; ROMS has been used in a variety of

TABLE 3.1 Characteristics of RANS Models Compared to Characteristics of the Regional Ocean Modeling System

| Physical Process | FVCOM | DHI-MIKE | Delft3D FM | ROMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turbine scale: turbine foundation-induced ocean wake | Subregion model resolving each turbine foundation (Chen et al., 2016; Cazenave et al., 2016) | Parameterized as a drag force (Johnson et al., 2021) | Parameterized as a drag force | Parameterized as a drag force |

| Horizontal mixing | Smagorinsky formulation of 2D subgrid scale | Smagorinsky formulation of 2D subgrid scale | 2D subgrid scale and 3D turbulence computed by a closure scheme | Horizontal Laplacian and biharmonic viscosity and diffusion |

| Vertical mixing | General Ocean Turbulence Model (GOTM) with a k/ε formulation from Umlauf and Burchard (2005) | Eddy viscosity determined from the k/ε turbulence scheme | Eddy viscosity determined from a 3D turbulence closure scheme | Vertical harmonic viscosity and diffusion computed by turbulence closure schemes |

| Physical Process | FVCOM | DHI-MIKE | Delft3D FM | ROMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom friction | Drag coefficient determined by spatially varying bottom roughness length in a logarithmic bottom layer | Drag coefficient determined by a Nikurades equivalent roughness length of 0.001 m (Johnson et al., 2021) | Drag coefficient determined by the law of the wall | Drag coefficient determined by the law of the wall |

| Strong stratification | Using a hybrid vertical coordinate derived from a generalized terrain-following coordinate and data assimilation (Li et al., 2015) | Applying a background vertical eddy viscosity; using the k/ε turbulence scheme; using Z-grid | ||

| Regional scale | Tide-, wind-, wave-, and density-driven flows; transport of conservative variables | Tide-, wind-, wave-, and density-driven flows; transport of conservative variables | Tide-, wind-, wave-, and density-driven flows; transport of conservative variables | Tide-, wind-, wave-, and density-driven flows; transport of conservative variables |

| Coupling of physical and ecological processes | Coupled with the FVCOM Generalized Ecosystem Module, which divides lower trophic food web processes into seven state variable groups, and the FVCOM Water Quality Module based on the EPA Water Quality Analysis Simulation Program | Coupled with MIKE ECO Lab for complex ecosystems and MIKE ABM Lab for agent-based modeling of coral spawn, eelgrass succession, or other species migration patterns | Coupled with the D-Water Quality module, including chemical composition of a water system and biological components up to the level of primary producers and some secondary producers | Coupled with the North Pacific Ecosystem Model for Understanding Regional Oceanography (Kishi et al., 2007), including 11 state variables (Zang et al. 2020). |

NOTES: The first three models, FVCOM, DHI-MIKE and Delft3D FM, have been used in BOEM-funded environmental impact studies to assess the effects of offshore wind energy installations in U.S. East Coast continental shelf waters. The Regional Ocean Modeling System (ROMS) characteristics are provided for comparison.

research and operational regional-scale model implementations on the U.S. Northeast North Atlantic Continental Shelf (He and Wilkin, 2006; Wilkin, 2006; Chen and He, 2010) and elsewhere. Nonhydrostatic versions of FVCOM, DHI-MIKE, Delft3D, and ROMS are available, although none have been used in BOEM-funded EIS studies for WEAs. The key relevant hydrodynamic processes simulated or parameterized by these RANS regional ocean models are listed in Table 3.1. The characteristics of ROMS are provided as a comparison.

The ability of RANS models to simulate the multiscale hydrodynamic processes of offshore wind farms depends on a number of factors that include (1) proper parameterizations of the drag force resulting from the ocean wake induced by turbine foundations at the turbine scale, (2) correct representation of the atmospheric wake caused by wind turbine effects on the wind stress that is applied at the ocean surface, and (3) adequate spatial and temporal resolution of the regional-scale model with appropriate open boundary conditions and atmospheric forcing.

The typical horizontal resolution used in implementations of RANS regional ocean models varies from 10 m to 10 km (e.g., Chen et al., 2016), which does not allow for resolving the turbine-scale ocean wakes that occur at meter to submeter scales and require nonhydrostatic pressure dynamics and LES of unresolved subgrid turbulence (Table 3.2). Thus, parameterizations of the turbine ocean wake effects as a momentum sink term in the horizontal momentum equations in the form of a drag and inertial force acting on the fluid by the turbine foundation have been implemented into these RANS models (Johnson et al., 2021). The turbulence closure schemes have also been

TABLE 3.2 Hierarchy of Scales Resolved by Various Models

| Scale of Effects | Resolution | Idealized | LES | Non-hydrostatic Models | RANS Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turbine O(1)m – O(1)km |

Millimeters to meters | ||||

| WEA O(1) km – O(10-100)km |

Meters to 10s of meters | ||||

| Region >O(100)km |

10s-1000s of meters |

![]() Only assess key processes at these scales

Only assess key processes at these scales

![]() Support predictions at specified resolution

Support predictions at specified resolution

![]() Some versions can support an unstructured grid

Some versions can support an unstructured grid

![]() Full range of process at these scales is constrained by computational capacity

Full range of process at these scales is constrained by computational capacity

![]() Can assess specific processes at these scales and requires parameterization

Can assess specific processes at these scales and requires parameterization

![]() Only assess key processes at these scales

Only assess key processes at these scales

![]() Support predictions at specified resolution

Support predictions at specified resolution

![]() Some versions can support an unstructured grid

Some versions can support an unstructured grid

![]() Full range of process at these scales is constrained by computational capacity

Full range of process at these scales is constrained by computational capacity

![]() Can assess specific processes at these scales and requires parameterization

Can assess specific processes at these scales and requires parameterization

modified to account for the drag force, and the skill of such parameterizations depends on the choice of the drag coefficient. Studies have shown that the drag coefficient is a function of the Reynolds number, varying over a large range. Although the relationship of the drag coefficient and Reynolds number for an unstratified flow around a vertical cylinder in the water column is well understood, uncertainties exist in complex stratified ocean circulation in the shelf and coastal regions. It is crucial to calibrate and validate the RANS models with appropriate drag coefficient values.

The flexibility provided by unstructured meshes, such as used in FVCOM, supports implementation of subregion models that cover the wind farm scale and explicitly resolve individual turbine foundations with a spatial resolution of 1.3 m (or 2.5 m) along the circumference (15.7 m) of a monopole (Cazenave et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2016). Compared with the drag-force parameterization approach, these subregion models, in theory, include the blockage effects of turbine foundations on the continuity or mass conservation of the flow, as well as the form drag due to flow separation around a turbine foundation (Chen et al., 2016), and thereby are intended to eliminate the need for an empirical drag coefficient. However, there are potential drawbacks to this approach. First, the turbulence parameterization must be carefully chosen to be capable of representing rapidly varying separated bluff-body turbulent flows that are naturally nonhydrostatic (Schimmels, 2007). Second, this approach results in a significant increase in computational cost, especially as the number of turbines increases (Cazenave et al., 2016) and does not resolve the effects of nonhydrostatic pressure and the boundary layer at each turbine foundation. The pros and cons of turbine-resolved and turbine-parameterized RANS models for complex ocean circulation are not well understood. It is recommended that a comparative study of the two approaches be carried out using a validated LES model as a reference (e.g., Schultze et al., 2020) as a part of intermodel comparisons.

There is robust literature on modeling the hydrodynamic impact of wetland vegetation on flows and surface waves in coastal areas. Vegetation stems were treated as cylinders of small diameter and parameterized as a drag force in the momentum equations in RANS and nonhydrostatic flow models (Morison et al., 1950; Ma et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2018). RANS models with such parameterizations were successfully used to simulate the hydrodynamics in wetlands (in analogy to the warm farm scale) under extreme weather conditions (Hu et al., 2015) and normal tidal conditions (Ge et al., 2021). Wind surface stress reduction due to the presence of vegetation was also considered in the wind forcing of coastal storms for RANS-type models. It can be concluded that RANS models incorporating proper parameterizations of vegetation-induced drag on the flow and wind stress reduction due to the increase in surface roughness are capable of modeling the cumulative impact of wetland vegetation on coastal hydrodynamics. This lends some confidence in the ability of commonly used RANS models to simulate the cumulative impact of turbines on the hydrodynamics at the scale of a wind farm if the turbine-scale ocean wakes and atmospheric wakes are properly parameterized in the models. It is recommended, however, that care be taken to determine the suitable drag coefficient through comparison with measurements and/or results from high-fidelity LES modeling (e.g., Chakrabarti et al., 2016; Jensen et al., 2018; Schultze et al., 2020).

Effects of offshore wind turbines on wind waves at a regional scale have been studied using spectral wave models based on the wave action balance equation (Chen et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2021). Model results show potential reduction of wave energy at the wind farm scale and beyond due to the modeled reduction of wind forcing in the atmospheric wake of turbines. Interaction of wind waves with turbines can contribute to ocean wake but it is mainly limited to the upper water column or near the free surface (Chakrabarti et al., 2016). LES and nonhydrostatic models are suitable for quantifying the effects of wave-induced turbulence around a turbine foundation. Wind wave effects have yet to be parameterized and implemented into RANS models to simulate the potential impact on ocean mixing at the wind farm and regional scales.

The regional-scale oceanographic processes in the Nantucket Shoals area are complex, as discussed in Chapter 2. The RANS models listed in Table 3.1 were designed to simulate tide-, wind-, wave-, and density-driven flows, and the transport of conservative variables (heat, salt, etc.). The model skill, however, depends on various factors, including (1) the open boundary conditions of a regional model domain, (2) the accuracy of the bathymetry and geometry of coastlines, (3) the momentum fluxes applied on the seabed and the ocean surface, (4) the parameterizations of turbulent mixing or the accuracy of the turbulence closure schemes, and (5) the temporal and spatial resolution of a model (e.g., Tian and Chen, 2006; Chen et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2016). For example, comparing the model results from the Northeast Coastal Ocean Forecast System, which is based on FVCOM, with the CODAR-derived surface currents in Block Island Sound over 8 years showed that tidal currents were overestimated because of inaccuracies in local bathymetry and bottom roughness (Sun et al., 2016). Modeled tidal elevations are sensitive to tidal forcing specified at the open boundary of the computational domain. Stratification has limited impact on tidal elevation, but it can significantly affect the tidal-current profile in the water column and can interact with the steep bottom topography, resulting in energetic internal waves (Chen et al., 2011). With sufficient spatiotemporal resolution as well as realistic open boundary and atmospheric forcing, RANS models such as ROMS are capable of simulating the interaction of Gulf Stream warm core rings and shelf-break circulation (e.g., Chen and He, 2010; Chen et al., 2014).

The errors in simulated temperature and salinity obtained from RANS models (Table 3.1) can be reduced through assimilation of data that include, but are not limited to, satellite sea surface height (SSH), sea surface temperature (SST), and other remotely sensed oceanographic data (Medina-Lopez et al., 2021), in-situ temperature, and salinity profiles measured by different methods, such as expendable bathythermograph, Argo floats, shipboard CTD casts, and glider transects (Chen et al., 2014b). With multidecadal, high-resolution, data-assimilated simulations, RANS models such as FVCOM can capture the significant seasonal and interannual variability of stratification in the Northeast Atlantic Continental Shelf (Li et al., 2015).

In addition to tide- and wind-driven circulation on the continental shelf, the hydrodynamic models implemented for the Nantucket Shoals region must include seasonal progression of stratification and capability to simulate interannual variability scenarios as well as the effects of long-term surface densification, onshore advection of warm core rings, and onshore migration of shelf-break front. Accurate representation of

these complex oceanographic processes is difficult and made even more so because of inevitable errors in the open boundary and atmospheric forcing, as well as the imperfect parameterizations of turbulent mixing and turbine-induced oceanic and atmospheric wakes. It is recommended that adequate model calibration and validation against field observations and intermodel comparison of key processes be implemented to evaluate model skill in predicting key metrics such as seasonal variability of stratification and atmospheric wake effects. A related recommendation is to identify key metrics that can be used to evaluate skill of individual models and across models.

Model calibration, verification, and validation should take a hierarchical modeling approach, starting with idealized simulations that address key physical processes at scales ranging from individual turbine, wind farm area with planned or built offshore wind farms, and regional area encompassing the wind farms (Table 3.2). The idealized simulations are particularly useful for the turbine-scale processes because much fewer turbine-scale observations are available compared to those at the regional scale. In the absence of field measurements near a turbine, high-fidelity models, such as LES models (e.g., Schultze et al., 2020), should be employed to produce reference results for idealized simulations to calibrate and verify the parameterizations of oceanic and atmospheric wake effects in regional RANS models. It is also highly desirable to develop reference results using high-fidelity models at the wind farm scale for idealized simulations. In addition to comparison with LES model results, idealized simulations at hierarchical scales should test the sensitivity of RANS model results to the spatiotemporal resolution. Such convergence tests should consider the realistic bathymetric and open boundary conditions, albeit simplified, to capture the key oceanographic processes. Moreover, it is necessary to consider the need for fine spatial resolution in zooplankton modeling when designing the computational mesh for hydrodynamic modeling. Studies have shown that spatial resolution of hydrodynamic models for coastal and shelf circulation can significantly influence the modeled transport and dispersal patterns of marine organisms in their early-life stages (Ward et al., 2023).

To capture the natural variability of oceanographic processes, multiyear simulations with long-term scalability should be conducted as opposed to considering only extreme weather events (Chen et al., 2016) or a single year (Johnson et al., 2021). The regional model domain needs to be large enough to include relevant open boundary fluxes from the Gulf Stream and the upstream region (Chen et al., 2014; Tian et al., 2014) because the interaction of the warm core rings and shelf-break circulation is one of the key physical processes in the Nantucket Shoals region. For model calibration and validation, observations from satellites, shore-based remote sensing platforms, in situ sensors, and airborne and shipborne sensing must be synthesized and utilized (Medina-Lopez et al., 2021). It is important to include model uncertainty estimates as part of the validation processes. The conclusion of a hydrodynamic modeling study on the environmental impact of offshore wind farms should be drawn in the context of model uncertainties, natural variability, and marine ecology.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Conclusion: Knowledge of the effects of offshore wind turbine structures on hydrodynamics is limited and primarily based on modeling studies. At the turbine scale, there are few observations that can be used to verify turbine-scale wake behavior, and coverage of parameter space is limited in modeling studies. At the wind farm scale, the potential impacts include reduction in ocean current speeds, reduction in the stratification, reduction in ocean surface wind speed, and deflection of the pycnocline. At the regional scale, perturbations due to turbines are difficult to quantify because of the natural processes that drive significant environmental variability across the region.

Understanding Hydrodynamic Effects

Conclusion: There are significant uncertainties in the hydrodynamic response of the wind and ocean wakes and of hydrodynamic effects of turbines.

Conclusion: Impacts of offshore wind development in the Nantucket Shoals region on the regional hydrodynamics are uncertain and will be difficult to isolate from the much larger magnitude of variability introduced by natural and anthropogenic sources (including climate change) in this dynamic and evolving oceanographic system.

Conclusion: More hydrodynamic observations are available at the regional scale than at the wind farm and turbine scales. Existing oceanographic monitoring programs historically have, and should continue to provide, important baseline data at the regional scale; new smaller-scale observational studies are encouraged and are a priority.

Recommendation: The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, and others should promote, and where possible, require observational studies within wind farms during all phases of wind energy development—surveying, construction, operation, and decommissioning—that target processes at the relevant turbine to wind farm scales to isolate, quantify, and characterize the hydrodynamic effects. Studies at Block Island, Dominion, Vineyard Wind I, and South Fork should be considered as case study sites given their varying numbers of turbines, types of foundation, and sizes of spacing of turbines.

Modeling Capability and Validation

Conclusion: The hydrodynamics of the Nantucket Shoals region are driven by complex interactions among shelf-break processes, seasonal stratification, annual variability, bottom friction, tides, and flows over complex bathymetry. In addition to these processes, models should also represent the variability associated with region-specific processes such as long-term surface densification, onshore advection of warm core rings, onshore displacement of shelf-break front, and interdecadal variability in circulation.

Conclusion: The structure and magnitude of the wind wakes from offshore wind turbines at the sea surface are poorly understood since most measurement and modeling efforts have focused on wind speed reductions at hub height. Further, the effect of the lower boundary layer (ocean surface roughness) and atmospheric stability on wind stress reductions at the sea surface is also poorly understood.

Conclusion: There is a hierarchy of important modeling approaches that assess hydrodynamic impacts, from small-scale idealized simulations and LES that resolve individual turbines to larger-scale, fully dynamic models at the regional scale.

Conclusion: Hydrodynamic modeling studies funded by BOEM (MIKE/DHI, FVCOM, Delft3D) differ in their parameterization and/or representation of turbines and wind farm areas, which likely have contributed to differences in simulated hydrodynamic wind and ocean wake impacts.

Conclusion: Model errors and uncertainty propagate through to the predictions and introduce associated uncertainty in assessing hydrodynamic and ecological impacts.

Recommendation: The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, and others should require model validation studies to determine the capability and appropriateness of a particular model to simulate key baseline hydrodynamic processes relevant at turbine, wind farm, and/or regional scales. These studies should

- Evaluate the ability of the model to represent the physical complexity of the processes specific to the questions asked (from small-scale idealized and large eddy simulation models to fully dynamic models at the regional scale).

- Evaluate the model sensitivity to selection of model configuration, parameterization, and/or turbine representation.

- Quantify the uncertainty in the simulated output and implications for interpretation of results.

- Evaluate model performance through intercomparisons with other models and, once available, data from observational studies at the turbine and wind farm scales.

- Make parameterizations, model configurations, and solutions publicly available to encourage engagement by the broader community to assess model predictions of offshore wind turbine impacts.

This page intentionally left blank.