Guide for Truck Parking Information Management Systems (2025)

Chapter: 2 Identifying the Purpose and Need for TPIMS

CHAPTER 2

Identifying the Purpose and Need for TPIMS

This chapter’s objective is to help an agency articulate the purpose and need for implementing a TPIMS program. Developing the purpose and need is a crucial step in initiating the TPIMS program lifecycle, as it establishes the rationale for TPIMS as the preferred alternative for addressing a critical freight transportation issue. A well-defined purpose and need are required to convince management and decision-makers that TPIMS is the best option to manage available truck parking efficiently among the myriad competing interests for funding.

The following actions can be undertaken to solidify a purpose and need:

- Establish a Purpose and Need.

- Point to TPIMS Deployment Examples.

- Identify and Engage Stakeholders.

- Tailor a TPIMS Solution.

- Identify a Process for Project Delivery.

- Identify Funding Opportunities.

The subsections in the chapter describe steps that a transportation agency or other IOO could use to commence their TPIMS program activities.

Establish a Purpose and Need

One of the first steps to build an agency-specific purpose and need for TPIMS is to understand the higher-level reasons why TPIMS is an appropriate option. The problem a TPIMS will address is fairly straightforward: truck drivers do not know whether an upcoming truck parking facility will have available spaces for them, and with limited truck parking capacity in the system, it is extremely challenging to plan ahead and predict where parking will be available (Boris and Brewster 2016). This inhibits the truck driver’s ability to plan their route in an optimal manner, potentially forcing an earlier stop (and subsequently less income) or risking to either (1) find parking at the lot (the best outcome), (2) risk an HOS violation by driving to the next parking facility, or (3) park in an unauthorized location to meet the HOS requirement. When dealing with these issues on a daily basis, many surveyed truck drivers cite these challenging decisions as a source of frustration and anxiety (MAASTO 2016). In ATRI’s Top Industry Issues report, “truck parking” was the top issue for truck drivers three years in a row (American Transportation Research Institute 2023).

The $940.8 billion trucking industry is foundational to the U.S. economy, hauling 11.4 billion tons of goods, equating to 72.6 percent of all freight transported in 2023 (American Trucking Associations 2023). To accomplish this, the trucking industry relies on more than 3.5 million truck drivers and 13.8 million commercial trucks, of which 3.1 million are tractor-trailer combination vehicles.

Numerous business models exist within the trucking industry to meet the demands of consumers and businesses, and the cost of operating trucks is relatively high. Recent research conducted by the American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI) determined that the average cost per hour to operate an “18-wheeler” was $90.78 in 2022—equating to a cost of $2.25 per mile (Leslie and Murray 2023). So, any freight movement delays or inefficiencies in the transportation system become costly additions to consumer prices. An earlier research study by ATRI found that driver respondents reportedly “gave up” an average of 56 minutes of available drive time per day by parking early rather than risking not being able to find parking down the road (Boris and Brewster 2016). This unused drive time effectively reduces an individual driver’s productivity by 9,300 revenue-earning miles annually—which equates to lost wages of $6,950 annually (adjusted to 2022 dollars) per driver—reflecting annual compensation losses of up to 10 percent.

While these challenges may seem to solely impact fleets and truck drivers, when truck drivers need to risk HOS violations by driving further to find parking, the fatigue associated with longer driving times creates increased safety risks for both truck drivers and other roadway users. Likewise, when truck drivers leave mainline roadways and highways to search for unauthorized parking, this can contribute to traffic congestion, air pollution, and roadway safety issues.

Building more truck parking facilities is one way to mitigate these challenges for drivers, but—like most infrastructure projects—they are subject to economic, social, and political challenges that seldom allow a quick solution. In the absence of more truck parking capacity, improving the information on where existing truck parking is available could help manage the full utilization of existing truck parking capacity. Extensive use of roadside message signs is one tool to help inform truck drivers of potential parking sites, but the lack of real-time awareness of whether that truck parking facility has available capacity means that truck drivers remain unsure whether they should act on a future truck parking opportunity.

Transportation agencies need to determine the extent of applicability for their operating environment, whether it be a state, region, county, city, or other governmental jurisdiction. Statewide freight plans, which are updated every few years to receive federal funding, provide information on the importance of freight movement by trucks and typically identify truck parking as a challenge. Conducting a truck parking study documenting supply and demand at public and private truck parking facilities can corroborate the need for additional truck parking, the specific locations for high truck parking demand, and the need to use existing truck parking more efficiently. Stakeholder engagement conducted as part of the freight and/or truck parking plan should gather user input on the benefits and targeted locations for implementing TPIMS. When engaging with truck drivers, it is important to emphasize that implementing TPIMS is only one of the strategies for improving truck parking—truck parking capacity expansion is also a critical strategy but is not covered in this Guide.

Outputs from those planning activities help refine the purpose and need statements that are unique to a given agency. Given that a TPIMS only provides information on available truck parking for existing capacity, a key limitation of TPIMS is when an agency’s supply of truck parking is near or at capacity. The true strength of a TPIMS is that it reduces the inefficiencies in truck parking that occur due to the lack of knowledge of specifically where and when parking is available. TPIMS helps to ensure that available capacity does not go unused, thereby allowing drivers to find authorized parking in a timely manner. A TPIMS that routinely reports during peak periods that all available capacity is being used—due to its operating in an overcapacity environment—does not achieve these benefits as there is no ability for drivers to find authorized parking where none is available. Even in a near-capacity or capacity-constrained environment, the efficiencies a TPIMS can achieve are limited as there exist spatial mismatches between available parking and drivers in need of rest. The availability of small numbers of truck

parking spaces far from a driver or along a corridor not on a driver’s planned route are less viable options for that driver may still be unable to find authorized parking in a timely manner.

These examples demonstrate why a TPIMS cannot solve an insufficient capacity problem. If almost all truck parking is used during peak demand periods, it is important that strong consideration be given to implementing a TPIMS in conjunction with truck parking capacity expansion. The implementation of a TPIMS with capacity expansion could help with the efficient utilization of the newly added truck parking, maximizing the return on investment by the agency.

Despite these limitations, a TPIMS deployment could still provide benefits to truck drivers even when truck parking is very limited during times of peak demand. The real-time or near real-time information on how quickly truck parking is filling will help truck drivers make a more informed decision on whether to stop before their HOS are reached. However, in a situation where the transportation agency is only monitoring truck parking availability for public truck parking areas, the truck driver would still lack information on availability at private truck stops.

Examples of TPIMS Deployments

There are multiple TPIMS-related research efforts and TPIMS deployments across the United States. Table 1 lists TPIMS deployments in the United States. A more detailed summary of these initiatives is included in NCHRP Web-Only Document 415: Developing a Guide for Truck Parking Information Management Systems. Note that some agencies use the term truck parking availability system (TPAS), which, for purposes of this Guide, is interchangeable with TPIMS.

Table 1. TPIMS deployments in the United States.

| Project | Agencies | Year(s) Operational |

|---|---|---|

| Not in Operation | ||

| Minnesota TPIMS Pilot | Minnesota DOT | 2012–2014 |

| Maryland Pilot Program | Maryland State Highway Administration (MDSHA) | 2013 |

| California Smart Truck Parking Implementation | California DOT | 2009–2011 |

| Tennessee and Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) Pilot | Tennessee DOT and FMCSA | 2015–2016 |

| I-95 Corridor Coalition TPIMS | Eastern Transportation Coalition; Virginia and Maryland DOTs | 2009–2011 |

| In Operation | ||

| Michigan I-94 TPIMS | Michigan DOT | 2014–Present |

| Mid America Association of State Transportation Officials (MAASTO) Regional TPIMS | MAASTO | 2019–Present |

| I-10 TPAS Project | Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California DOTs | 2024–Present |

| Florida TPAS Deployment | Florida DOT | 2017–Present |

| Indiana Toll Road Concession Company (ITRCC) TPAS | ITRCC | 2021–Present |

| Kansas Turnpike Authority (KTA) TPIMS | KTA | 2020–Present |

The following provides an overview of the TPIMS deployments highlighted in Table 1:

- Minnesota Initial TPIMS Deployment. Minnesota was the first state in the country to deploy a TPIMS pilot. Minnesota implemented a pilot study where video cameras with stereoscopic video analytics tools were used to assess parking utilization and availability in real time (National Coalition on Truck Parking 2018). The information about parking utilization was then conveyed to truck drivers via roadside message signs and other communication tools.

- Maryland Pilot Program. The Maryland State Highway Administration (MDSHA), with support from the University of Maryland at College Park, developed and tested an automated low-cost and real-time truck parking information system (National Coalition on Truck Parking 2018). The parking detection system was piloted at MDSHA’s truck parking facility on northbound I-95 at the North Welcome Center from January 2013 to May 2013. The research team used in-ground sensors to detect vehicles parked at the test site and found that its method for vehicle detection had an average overall detection error rate of 3.75 percent.

- California Smart Truck Parking Implementation. The Smart Truck Parking project was a collaborative implementation and research effort among the FHWA, California DOT, the University of California at Berkeley, and other partners (National Coalition on Truck Parking 2018). The project tested video detection and in-ground sensors at truck parking facilities in the cities of Sacramento and Stockton. Information collected from these areas was broadcast on dynamic message signs (DMS) and on americantruckparking.com, where information is updated every five minutes.

- Tennessee DOT and Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) Efforts. The Tennessee DOT and FMCSA SmartPark program was one of the first TPIMS deployments and aimed to reduce illegal and dangerous parking practices along I-75 in eastern Tennessee (Perry et al. 2015). Among other accomplishments, the SmartPark program demonstrated (1) how two truck parking areas could be linked, such that trucks could be diverted from a full area to one with availability; (2) how a truck parking reservation system could work; and (3) how truck parking availability information could be disseminated.

- I-95 Corridor Coalition. The I-95 Corridor Coalition (now named the Eastern Transportation Coalition) piloted a truck parking system called Truck ‘N Park (National Coalition on Truck Parking 2018). This system uses space-by-space availability monitoring through in-ground sensors. The Truck ‘N Park system includes five public rest areas in Virginia, three located on I-95 Northbound and two located on I-66. In March 2018, the I-95 Corridor Coalition transitioned operation and maintenance of the Truck ‘N Park system to the Virginia DOT.

- Michigan and Initial TPIMS Deployment. Michigan installed TPIMS on I-94 as part of the FHWA’s Truck Parking Facilities program (National Coalition on Truck Parking 2018). The TPIMS used wireless magnetometers for entry/exit count detection at public rest areas and per-space detection using video cameras at private facilities. Roadside DMS, smartphone apps, in-cab displays, and multiple websites published the real-time information for drivers.

- Mid America Association of State Transportation Officials (MAASTO) Regional TPIMS. The MAASTO Regional TPIMS includes a participating block of midwestern states comprising Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin (MAASTO 2016). Figure 3 shows a map of the existing and planned development of TPIMS corridors in the MAASTO region. A notable characteristic of the MAASTO Regional TPIMS is that while the means of detection and notification were uniquely defined within each state, the information collected from each state was standardized via JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) web service feeds and shared through a common application program interface (API) via DMS, traveler information websites, and a smartphone app. One key development in this project was the Regional TPIMS Data Exchange Specification Document, which standardized the data feed containing JSON scripting language that all third-party application developers would need to display TPIMS data on their platforms (MAASTO 2018). This data exchange specification is one potential tool that could help lead to national interoperability across TPIMS programs.

Figure 3. MAASTO region showing TPIMS corridors.

- I-10 TPAS Project. The I-10 Corridor Coalition, consisting of DOTs from Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas (National Coalition on Truck Parking 2018) was formed to enhance safe and efficient travel along this vital trade corridor. Coalition members developed a memorandum of understanding and conducted workshops to improve freight movement, with a focus on truck parking information systems. In 2018, Texas DOT, on behalf of the four states of the I-10 Corridor Coalition, applied for $6.8 million from the U.S. DOT Advanced Transportation and Congestion Management Technologies Deployment (ATCMTD) Program, as well as an equal amount of state matching funds (Texas DOT 2020). The project, initiated in late 2019, aims to implement TPIMS at 37 public truck parking locations along the I-10 Corridor (see Figure 4 for a map of the planned I-10 parking locations).

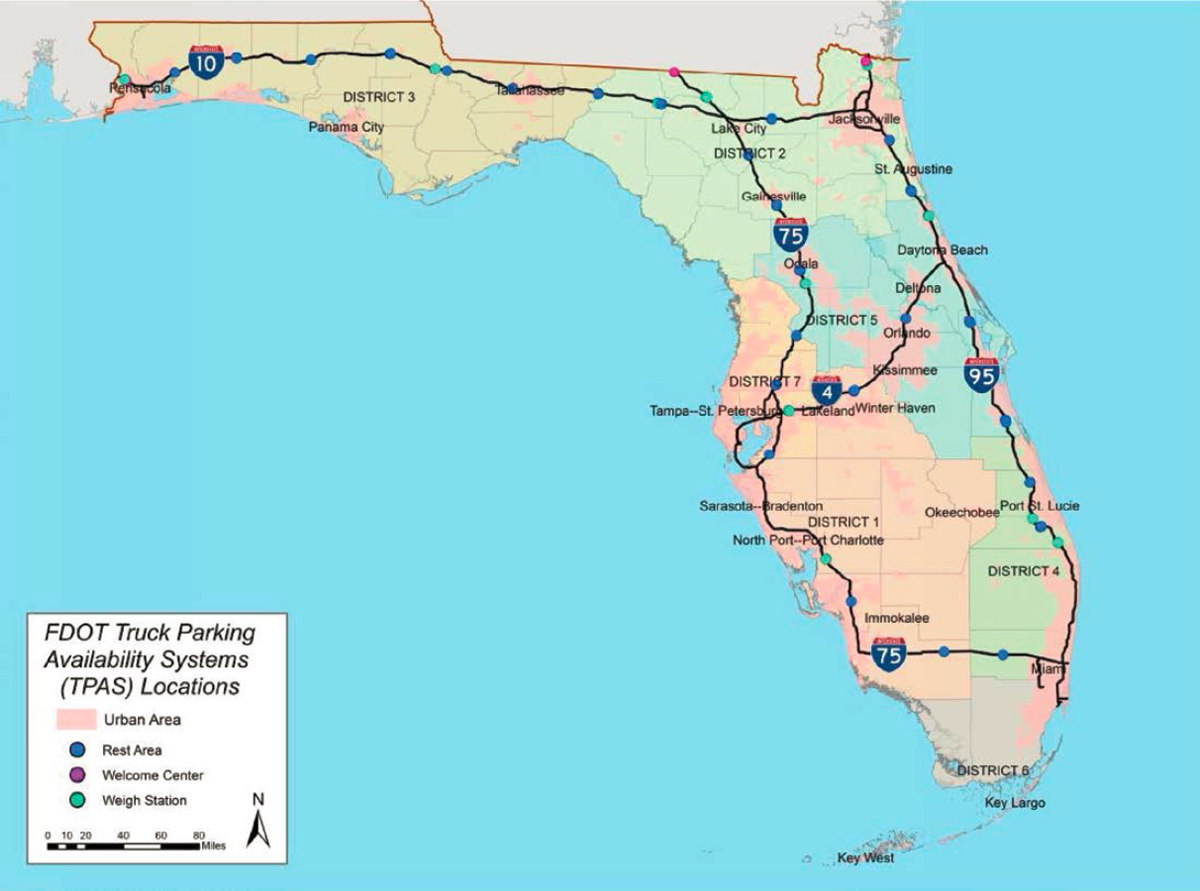

- Florida TPAS Deployment. The Florida DOT invested in an extensive deployment of TPIMS (they use the phrase TPAS instead of TPIMS), depicted in the map shown in Figure 5, which included 45 rest areas, 20 weigh stations, and three welcome centers where trucks frequently park (National Coalition on Truck Parking 2018). This deployment spanned across all Florida DOT districts and utilized multiple vendors. Data collection used either in-ground sensors or mounted sensors to monitor ingress/egress. Furthermore, TPIMS devices were integrated into the existing ITS communications network.

- Indiana Toll Road Concession Company (ITRCC) TPAS. ITRCC is a private concessionaire that operates a 157-mile segment of I-90 (and portions of I-80) through northern Indiana (ITRCC n.d.). ITRCC added TPIMS coverage to 12 sites (travel plazas and dedicated truck parking lots) along its network. The system uses a mix of cameras and sensors to track the number of available parking spaces and then distributes that data across the system using

Figure 4. I-10 truck parking corridor map.

- roadside signs and other dissemination tools. ITRCC began a demonstration period in 2021, evaluated the system to determine its efficacy, and continues to operate all 12 sites and signs.

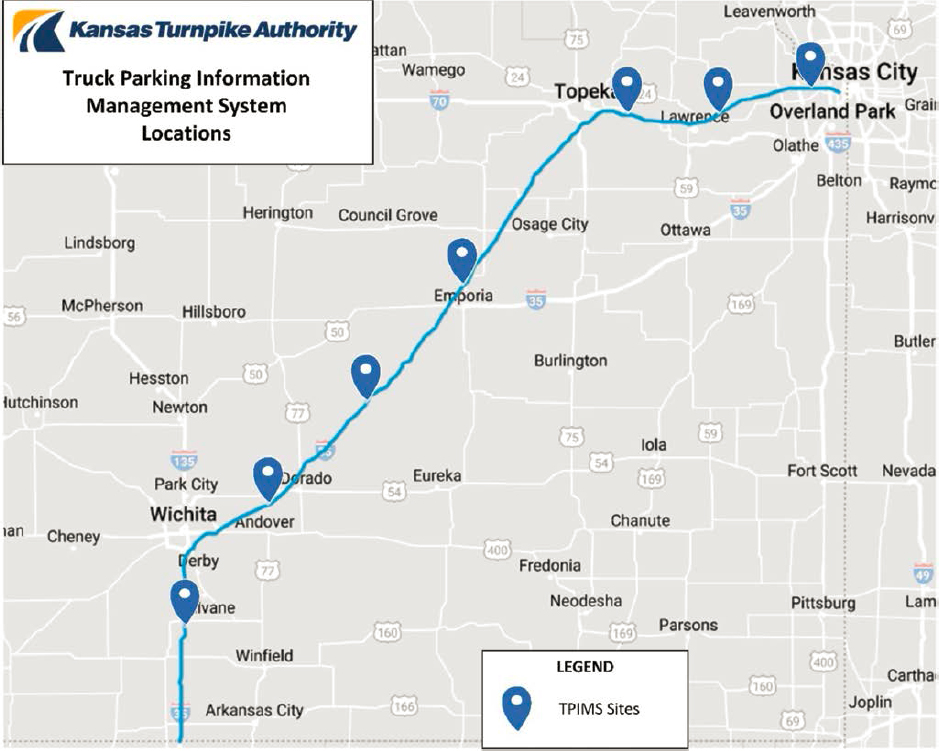

- Kansas Turnpike Authority (KTA) TPIMS. KTA developed a TPIMS, depicted in the map shown in Figure 6, that informs truck drivers of available spaces (KTA 2019). There is limited published research data about the design details or evaluation outcomes of this system. KTA’s traveler information site currently provides information on commercial parking stalls that are available along its facilities.

Identify and Engage Stakeholders

Stakeholder engagement is critical during the development of initial program objectives and approaches, as well as to support future activities. Identifying and establishing a base of engaged stakeholders will help subsequent planning and design processes to ensure that the deployed system provides the service that the community finds valuable. There are several stakeholder group types that are important targets for outreach:

- Representatives of the trucking industry and truck drivers. State and national trucking associations, truck driver and owner-operator associations, state freight advisory committees, and shipper groups.

- Truck stops. Private truck stop owners and truck stop operator associations.

- Transportation agencies. Freight, ITS, transportation systems management and operations (TSMO), facilities, maintenance, and information technology (IT) personnel.

- Enforcement agencies. State patrols, motor vehicle enforcement, and state commercial vehicle agencies.

Figure 5. Florida TPAS map.

Recognize Public- and Private-Sector TPIMS Roles and Motivations

There are important differences and similarities between public-sector and private-sector organizations as they relate to truck parking, each with different needs and perspectives. For example, private-sector truck parking—which represents the large majority of eligible truck parking spaces in the United States—is often perceived by public-sector planners as benefiting greatly from a TPIMS deployment, but in reality, private-sector truck parking groups operate with different business models and may be disinclined to participate in public-private collaborations. These parking groups may be reluctant to ever broadcast that their facilities may be at or over capacity. Truck stop operators generally view truck parking as a financial liability as it does not directly generate revenue (outside of limited reservation systems); selling goods and services (fuel, food, showers, etc.) is their primary revenue source. Public-sector infrastructure owners, most commonly transportation agencies, have parking facilities with direct access from interstates and roadways, but federal rules prohibit them from garnering commercial revenue from their facilities.

Figure 6. KTA TPIMS locations.

Understanding these differences can help a prospective public-sector agency to properly engage with these groups and “sell” the concept in a manner that aligns more with private-sector business motivations.

Tailor a TPIMS Solution

From the outside, a TPIMS may seem to be a straightforward solution that an agency can institute or replicate with minimal effort. In reality, a generic approach does not work for each agency’s unique circumstances. The following realities convey the basis for somewhat customized approaches:

- Different parking lot attributes and designs. Some transportation agencies have design standards that separate truck parking from general passenger vehicle traffic, while others allow mixed-use parking. Some agencies require marked parking stalls, whereas others may be unmarked and have greater flexibility on where parking occurs. Because of this, it is important for agencies looking to implement TPIMS to consider parking lot designs based on their specific needs as opposed to replicating what was done elsewhere.

- Different ITS standards. Each transportation agency has its own ITS standards that are based on their specific maintenance, operational, and environmental needs. The equipment and method used to detect, process, communicate, and disseminate electronic information varies. As a result, those standards may not fit the unique needs of another agency in their deployment of TPIMS.

- Different policies as well as procurement models. Transportation agencies may be required to adhere to certain state laws and regulations that are specific to their state. As a result, certain procurement models or data-sharing agreements that worked for one agency in another state may not be feasible elsewhere.

- Lack of first-hand parking operations and design experience. State transportation agencies may build truck parking lots using design standards, but historically, they have not been in the business of monitoring real-time parking utilization. As a result, transportation agencies may not have the in-house staff resources for building a TPIMS. In this case, they would need to develop those resources before attempting to implement a system used in another state.

- Different states, regions, and/or corridors have unique freight lanes and activities. Elements of a TPIMS deployed in another state may be unique to its multimodal freight network (e.g., urban versus rural activities, staging near port or major freight intermodal facilities, seasonal surges in truck activity associated with agricultural activities). These types of truck operations nuances could change the TPIMS approach from agency to agency.

These various challenges can all be resolved with careful planning and design. Understanding and leveraging these unique differences enables thorough project development as opposed to rapid procurement of an “off-the-shelf” system.

Identify a Process for Project Delivery

Identifying high-level processes for delivering TPIMS prior to commencing project planning is an essential action for solidifying a purpose and need for TPIMS and showing how it may be achieved. TPIMS, being a system of multiple subsystems, closely follows the development practices associated with ITS project implementation. FHWA recommends designing and deploying such systems using the systems engineering approach that was introduced in Chapter 1 (FHWA 2007).

As discussed in Chapter 1, the systems engineering approach is a structured process for defining the problem, identifying needs and requirements, and ultimately implementing a system that meets user needs. This approach must be followed when using federal funds for ITS project development, such as the deployment of a TPIMS (23 CFR §940). The V-diagram, shown in Figure 1 and commonly used in the ITS community as a systems engineering approach, outlines considerations that must be considered throughout the lifecycle of TPIMS.

However, it is important to note that the processes outlined in the V-diagram closely follow the traditional public-sector model for ITS project delivery. In reality, TPIMS is both a public-sector and private-sector venture. Private-sector deployment groups may have different motivations for TPIMS and follow different processes for project development.

Identify Funding Opportunities

While funding is often dealt with in planning phases, funding opportunities can be identified in advance. This subsection provides insights—gained through research on TPIMS deployments in the United States—on what funding programs were used by other agencies that implemented TPIMS programs. Depending on the funding resources available, this could provide an opportunity to tailor the purpose and need statement to increase the eligibility of a TPIMS program for certain types of funding.

Table 2. TPIMS deployments and funding sources.

| Project | Agencies | Grant Funding Source |

|---|---|---|

| Minnesota TPIMS Pilot | Minnesota DOT | FHWA Truck Parking grant program |

| Michigan I-94 TPIMS | Michigan DOT | FHWA Truck Parking grant program |

| California Smart Truck Parking Implementation | California DOT | FHWA Truck Parking grant program |

| Tennessee and FMCSA Pilot | FMCSA Innovative Technology Deployment (ITD) grant program | |

| I-95 Corridor Coalition TPIMS | Virginia DOT and MDSHA | Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) grant program |

| MASSTO TPIMS | Kansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky DOTs | TIGER grant program |

| I-10 TPAS Project | Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California DOTs | ATCMTD grant program |

| Florida TPAS Deployment | Florida | Accelerated Innovation Deployment (AID) grant and Fostering Advancements in Shipping and Transportation for The Long-Term Achievement of National Efficiencies (FASTLANE) grant program |

| Colorado TPIMS | Colorado | FASTLANE grant program |

Source: National Coalition on Truck Parking 2018

Many TPIMS programs were funded through freight-related federal programs, while others were funded as part of technology grant programs and safety research. Table 2 lists several TPIMS deployments and their funding resources.

Federal grant programs often require some percentage of non-Federal funding match, e.g., from states or others. The required efforts to document benefits will also vary depending on the specific grant purpose and requirements. For example, TIGER grant funding was focused on economic development (FHWA 2016), while ATCMTD grants are focused on mobility and safety benefits along with lessons learned (FHWA 2016).