Promoting the Quality of Data on Marine Recreational Fishing (2026)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

BACKGROUND

In 2006, the National Research Council conducted a review of the survey program of the erstwhile Marine Recreational Fisheries Statistics Survey (MRFSS), which was established in 1979 and administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). That review, in part, resulted in MRFSS being replaced by a new survey in 2008,1 called the Marine Recreational Information Program (MRIP). At its core, MRIP includes two surveys of fishing effort: the Fishing Effort Survey, or FES, for shore and private boat anglers; and the For-Hire Telephone Survey, or FHS, covering charters and guides. These two surveys estimate fishing effort. An intercept survey (Access Point Angler Intercept Survey, or APAIS) estimates angler catches and discards on trips. When combined, the results of the two surveys provide an estimate of total recreational harvest. MRIP has since substantially revised the survey methods that had been used by MRFSS to address the issues identified by the 2006 National Research Council review. In particular, MRIP initiated significant efforts to develop and maintain up-to-date documentation supporting program operations, transparency, and continued evaluation of methodological improvements (National Marine Fisheries Service, 2025b).

___________________

1 https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/recreational-fishing-data/marine-recreational-information-program-milestones#:~:text=In%201976%2C%20the%20Magnuson%2DStevens,more%20timely%20recreational%20catch%20estimates

NOAA’s Office of Science and Technology established the Fisheries’ Recreational Fishing Survey and Data Standards to guide the design, improvement, and quality of the information produced by recreational fishing surveys administered or funded through MRIP.2 The standards were created to respond to Office of Management and Budget (OMB) requirements, to meet recommendations from the National Academies, and to align with the best practices of other federal statistical agencies.3 They were based on existing federal guidelines and best practices for the dissemination of statistical information, including Principles and Practices for a Federal Statistical Agency (National Academies), Standards and Guidelines for Statistical Surveys (OMB), and practices in places such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Census Bureau, the Department of Education, the Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Geological Survey, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, and the International Household Survey Network.4 The standards are categorized as below:5

- Standard 1: Survey Concepts and Justification. Outlines considerations for survey planning, including its goals and objectives, which should meet key estimates and precision requirements; legislation or executive orders that have mandated the data collection; adherence to OMB requirements; and intended users. Requires developing supporting materials to meet OMB requirements and describing the intended users.

- Standard 2: Survey Design. Requires development, review, and certification of a technical document describing the survey objectives, sampling methods and basic data collection, estimation methods, and evaluation of methods.

- Standard 3: Data Quality. Requires description of the data processing procedures to mitigate errors and the methods to compensate for item non-responses. Also requires a quality assurance plan for each phase of the survey process.

- Standard 4: Transition Planning. Outlines the development of a transition plan before the implementation of new or improved sampling or estimation designs likely to result in large deviations from historical estimates.

- Standard 5: Review Procedures. Ensures that all survey designs are subject to the certification requirements set forth in the NOAA

___________________

2 https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/recreational-fishing-data/recreational-fishing-survey-and-data-standards

3 Richard Cody, presentation to the panel on April 17, 2025.

4 Ibid.

5 The text below is a condensation. See https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/recreational-fishing-data/recreational-fishing-survey-and-data-standards for the complete standards.

- Fisheries Policy Directive 04-114. Outlines specifications for a required annual report for each survey that must be submitted at the conclusion of each survey year.

- Standard 6: Process Improvement. Requires survey sponsors to evaluate survey designs to ensure that methods address emerging needs and incorporate current best practices. The MRIP Program Management Team will evaluate recommendations to implement or further explore revisions while also identifying possible opportunities for additional research. Based on survey results, survey sponsors are to identify deficiencies requiring unanticipated design modifications that are required to be communicated to the MRIP Program Management Team.

- Standard 7: Access and Information Management. Information products must include published data to be hosted online each survey year with associated weights and statistical elements. Information products associated with data collections funded by NOAA Fisheries must meet the federal information management requirements.

Overall, these standards support MRIP’s commitment to data quality, consistency, and transparency by providing a single set of guidelines for recreational fisheries data collection and estimation, though potential improvements are discussed in Chapter 3. MRIP’s different survey programs currently aim to meet the standards using documentation-based models to confirm the standards are met. There is some flexibility in this matter. For example, the Fishing Effort Survey meets all the standards using three documents: (a) a comprehensive survey design document; (b) if applicable, a transition plan; and (c) an annual report that covers all the other standards requirements. This approach is deemed appropriate if a single entity is responsible for administering the survey.

The APAIS is a contrasting example, as NOAA Fisheries is the lead survey administrator (designs the survey, selects the sample, and produces estimates), but regional partners coordinate all aspects of data collection and are responsible for data processing (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2022). In such settings, a collaborative effort between the lead survey administrator and its partners is needed. The lead survey administrator develops (a) a survey plan; (b) a comprehensive survey design document; and (c) if applicable, a transition plan. Each partner entity develops an annual report that meets all the other documentation requirements.6 All standards documentation is uploaded into the NOAA Fisheries Research

___________________

6 The Marine Fisheries Commissions submit reports that cover activities by states participating in the conduct of the NOAA-administered APAIS/FHS. States are responsible for submitting reports for their state surveys (usually through the commissions also).

Publication Tracking System. Once it is submitted, MRIP staff review the documents to verify that they meet the standards. Once verified, all documentation is made publicly available in MRIP Reports Database.

Given that states and regional organizations often have specific needs that differ from those of the federal survey system, creating a common set of minimum standards helps to promote consistency, comparability, and additivity across the various surveys. The standards thus directly apply to those surveys administered by MRIP and are also a basis for certifying state and regional surveys. Being certified helps state and regional surveys qualify to receive federal funding and to have their data admitted to MRIP, so state and regional agencies have an incentive to achieve certification. The standards facilitate the shared use of statistics produced by these programs by promoting data quality, consistency, and comparability between data collection programs.

The overarching goal of these standards is to further ensure the scientific integrity of data collection efforts, the quality of recreational fisheries statistics, and the strength of science-based management decisions.7 These standards also reflect current best practices at the National Center for Health Statistics, the U.S. Census Bureau, and other federal agencies, as well as statistical survey standards and guidelines published by OMB.

OVERVIEW OF MARINE FISHERIES MANAGEMENT

Management of the nation’s marine fisheries is conducted under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (as amended, hereafter the Magnuson-Stevens Act, or MSA). This act seeks to prevent overfishing, rebuild overfished stocks, ensure conservation, and realize the full potential of the nation’s fishery resources (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 1977). The responsibility for complying with the MSA is assigned by the MSA to NMFS within NOAA. Although the MSA strictly is charged with regulating fisheries in federal waters (from 3 to 200 miles offshore), its goals and approaches have heavily influenced fisheries management by coastal states. Indeed, many species of fish and shellfish occupy both state and federal waters, thereby requiring coordinated action by state and federal regulators. This is implicitly recognized through the composition of the eight Regional Fishery Management Councils established by the act and by the three Interstate Fishery Commissions. The eight councils manage federal waters, with the federal government providing the legal framework and the applicable states in each region

___________________

7 https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/recreational-fishing-data/recreational-fishing-survey-and-data-standards

having seats on the councils, while the three commissions coordinate fishery management in state waters.8

The MSA established national standards for fishery conservation and management. In particular, National Standard 19 establishes a quantitative framework for defining overfishing limits and acceptable biological catches and for plans for rebuilding overfished stocks of fish as required under the act. Under National Standard 2,10 the information that is required to define these management reference points must be the best scientific information available and must “ensure the highest level of integrity, and strengthen public confidence in the quality, validity and reliability of the scientific information[…]” (National Standard 2) in reaching management decisions.

Marine fisheries consist of three sectors: commercial, recreational, and subsistence. The commercial sector comprises a relatively small number of permit holders that land fishery products in a relatively small number of ports. Commercial permit holders are required to report to NMFS their catches, which can be compared to the records of buyers in each port to audit the reliability of catch records. In contrast, recreational fisheries comprise a substantial number of anglers, who access resources from diverse locations that include public and private access points. Recreational catches do not enter the market, so there is no audit trail. Moreover, the prevalence of both recreational fishing and catch-and-release practices is increasing (Ihde et al., 2011). Both aspects of marine recreational fishing make estimating recreational catches complex.

MRIP conducts a complete set of surveys designed to estimate annual recreational catches of managed species in U.S. marine waters (all coastal and oceanic waters under U.S. jurisdiction; NASEM, 2021a). It is conducted cooperatively by federal, state, and other partners. A considerable amount of work goes into this under a single framework that allocates sampling effort across a broad swath of the U.S. coastline. Some states have developed their own stand-alone surveys of recreational catch and effort, such as the LA Creel survey in Louisiana and the California Recreational Fisheries Survey. These partner organizations can become certified by MRIP through a process to ensure that they meet its standards for survey design, sampling effort, and data integrity.

___________________

8 The eight councils are the New England Fishery Management Council, Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council, South Atlantic Fishery Management Council, Caribbean Fishery Management Council, Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council, Pacific Fishery Management Council, North Pacific Fishery Management Council, and Western Pacific Fishery Management Council. The three commissions are the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission, and Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission (PSMFC). Only Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission has regulatory authority.

9 NS1, 50 CFR Part 600, Federal Register 81:201.

10 NS2, 50 CFR Part 600, Federal Register 78:139.

Although there are differences among the component surveys comprising the complete MRIP national data collection effort, surveys generally involve three components. First, at the federal level, the APAIS interviews anglers returning from fishing trips at public access points, with state officials seeing and measuring the catch. This is done to estimate the number, sizes, and species of fish caught as well as those that were released during the trip (catch per trip) by mode (e.g., along the shoreline, on a private or charter boat). Second, the FES, currently conducted through U.S. mail delivery, estimates the number of trips an angler has made in the preceding period. In simple terms, the product of the APAIS and the FES summed over each of the reporting periods in a year provides an estimate of the recreational catch by individual anglers (NASEM, 2021a). Similar to the FES, NOAA also measures fishing effort through the FHS, conducted by states along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts and coordinated by their respective marine fisheries commissions. Third, completing the picture are a number of supplemental surveys that estimate the catch from permitted party/charter boats, which are required to report the species and number of fish caught on each trip as a term of their permit.

MRIP has been independently reviewed by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine previously (NASEM, 2021a). These reviews focused on the appropriateness of the statistical design and analysis of surveys, efforts to account for known sources of uncertainty, including out-of-frame angler-trips, survey coverage and non-response, and recall biases. Both reviews were generally positive but made specific recommendations for NMFS’ consideration, many of which have been adopted.

NATIONAL GUIDELINES FOR SETTING DATA STANDARDS

The collection of information used by the federal government to make decisions is governed by the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018 (Evidence Act). OMB, a unit of the Executive Office of the President, has published the final rule on Fundamental Responsibilities of Recognized Statistical Agencies and Units. Although NMFS is not a Recognized Statistical Agency [or] Unit, the OMB final rule provides a useful framework from which the panel evaluates MRIP data standard.

The aforementioned final rule identifies four fundamental responsibilities that should underpin all federal data used to support government decisions and regulations. All Recognized Statistical Agencies and Units and other federal bodies should

(1) produce and disseminate relevant and timely statistical information, (2) conduct credible and accurate statistical activities, (3) conduct objective statistical activities, and (4) protect the trust of information providers by ensuring confidentiality and exclusive statistical use of their responses (OMB, 2014, 2024).

The Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology (FCSM) is an interagency technical advisory group committed to ensuring the provision of high-quality data across federal agencies. Based on a review by the Committee on National Statistics (NASEM, 2017a,b), FCSM developed recommendations to enhance the quality of data used in federal decision making. In its Framework for Data Quality (FCSM, 2020), the committee identifies three domains of data quality: utility, objectivity, and integrity. Each domain has a number of associated dimensions that comprise a more quantitative foundation for each domain (FCSM, 2020). Several of the dimensions identified by FCSM are useful for evaluating the data standards for MRIP proposed by NMFS. For example, several of the data standards for MRIP proposed by NMFS relate directly to the integrity domain and its associated dimension of scientific integrity, credibility, and confidentiality. Additionally, the FCSM dimension of data accessibility as a measure of data quality has implications MRIP’s Standard 7.

MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY

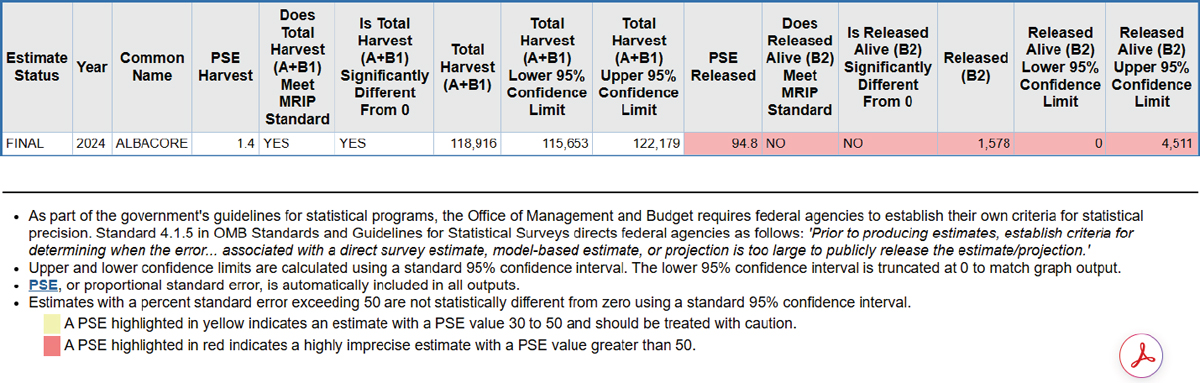

NOAA’s Office of Science and Technology has consistently sought external reviews of its surveys of recreational fisheries (NASEM, 2017c, 2021a; National Research Council, 2006), but it was led to seek this National Academies review by one particular aspect of the data standards. Following OMB instructions to establish standards defining when errors are too large for data to be publicly released, and using U.S. Census Bureau standards as a model, MRIP initially set 50 percent as the maximum percent standard error (PSE) beyond which estimates would not be reported. However, this element of the data quality standards was never fully implemented because of complaints from end users. Data users expressed a need for data, even data with large PSEs, to manage species. There was also public concern over a perceived lack of transparency, with some data users having access to microdata producing estimates with high PSEs while the public at large could not readily access those data. Consequently, MRIP revised its standard, publishing the data and including a color-coded flag to show when the PSE was high. As an example, the count for the total national harvest of albacore in 2024 met MRIP standards, but the count for the total released alive did not meet the standards; color coding was used to indicate the lack of precision in the latter total (Figure 1-1).

SOURCE: NOAA Fisheries. Recreation Fisheries Statistics Queries. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/data-tools/recreational-fisheries-statistics-queries

An additional motivation for reviewing the data standards is the increased implementation of state-sponsored surveys to estimate effort and catch. Some of these surveys (e.g., Alabama’s Snapper Check, Mississippi’s Tails & Scales) have been conducted in parallel with MRIP surveys, while others (e.g., Louisiana’s LA Creel) have been designed to be used in place of MRIP’s long-term surveys. State interest in finer spatial and temporal resolution as well as active quota monitoring for recreational fisheries have driven these programs. As more states adopt such surveys, their compatibility with MRIP’s long-term data as well as reconciliation between different catch estimates derived by different surveys become greater priorities. Agreement on basic standards is a necessary first step to accomplishing such goals. MRIP uses certification, inclusion in the MRIP data program, and concomitant financial support as tools for encouraging the use of uniform and high-quality standards.

These issues illustrate the value of conducting a review of the standards to ensure that they align with the best practices of other federal statistical agencies, which had been a goal of MRIP in the standards’ initial development. To conduct such a review, NOAA asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to convene an expert panel to review the standards, providing the charge shown in Box 1-1.

In this report, the panel separates the issue of data standards from concerns over whether MRIP is capable, as designed, of providing data on

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

At the request of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries’ Marine Recreational Information Program (MRIP), the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will establish an ad hoc committee to review and evaluate the MRIP survey and data standards (MRIP Standards). This committee is assigned the following tasks:

- Evaluate the effectiveness and applicability of MRIP standards for key data uses, considering a few exemplar domains and sectors.

- Identify the alignment of MRIP standards with best practices in federal agencies and the survey profession, in general.

- Assess the adequacy of the MRIP standards for meeting the the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Standards and Guidelines for Statistical Surveys.

The committee will produce a brief, targeted final report focused on its assessment of the standards, including conclusions and recommendations for improvements to the standards.

recreational catch at time and spatial scales of increasing interest to managers. The panel consciously separated these two issues, focusing on its charge to review data standards for MRIP. The panel views the question of whether MRIP is capable of providing information at short temporal scales (within season) and small spatial scales (individual states and basins) as important but outside its Statement of Task. Earlier reviews by National Academies panels examined the content and methodology for MRIP surveys (NASEM, 2017c, 2021a,b; National Research Council, 2006). Nevertheless, we do provide some discussion of techniques that might help to improve data quality. The panel notes that MRIP data are a primary data source for many involved in fisheries research and management, and some questions of interest to economists and ecologists may not be fully supported by the survey data (e.g., see Abbott, 2015; Abbott et al., 2018, 2022; Arlinghaus et al., 2019; Fujiwara et al., 2018; Homans & Wilen, 1997; NASEM, 2021b). The determination of what content should be collected and distributed by MRIP is beyond the scope of this panel, but we encourage MRIP to seek a broad range of input on how the surveys might be improved.

MRIP indicated that its interest in meeting OMB standards was focused on the decision it had made about handling estimates with high standard errors; as discussed earlier, MRIP initially asked for the suppression of estimates with PSEs greater than 50 but later moderated its position to say that it will publish, but not support the use of, statistics with PSEs greater than 50. The panel therefore focused particularly on that issue. More generally, MRIP standards require compliance with OMB standards (see Standard 1), so implicitly the two sets of standards are consistent. Much of what MRIP standards do is to create more specificity about particular aspects of the OMB standards, such as guidance on when standard errors are too high and what data should be collected on MRIP-related surveys. Other aspects of OMB standards, such as the importance of pretests, are not explicitly mentioned in MRIP standards but are implicitly incorporated through the requirement to comply with OMB standards.

MRIP also expressed interest in how newer developments, such as statistical model building, might be relevant. This was noted by Richard Cody, director of the Fisheries Statistics Division within NOAA, in his presentation to the panel. Such developments have the potential to expand statistical monitoring beyond the use of survey research, which is the focus of MRIP data quality standards, to the use of other types of data. This interest in newer developments widened the panel’s approach somewhat, taking it beyond MRIP standards in the current statistical environment to a broader conception of statistical data collection and monitoring as it might be

applied in the future. Potential benefits are not just for the federal surveys, but also for meeting states’ diverse needs, such as timeliness and precision.

APPROACH OF THE PANEL

The panel’s first step was to examine the statement of task to determine what information would be needed. The panel first met with NOAA leaders and statisticians to discuss its view of the task statement. Based upon these discussions, the panel determined that it should work through each standard individually, but that there could also be larger considerations that were applicable across multiple standards or perhaps reflected needs not mentioned in the standards.

The panel members next examined what information it needed to complete the statement of task. Collectively, the panel members brought expertise in statistics, ocean and fisheries sciences, and survey research. The panel reviewed essential MRIP documentation to understand current data standards and the technical details of sampling designs and estimation methods. This documentation included, but was not limited to, the MRIP Data User Handbook (National Marine Fisheries Service, 2025a) and the publication, MRIP Survey Design and Statistical Methods for Estimation of Recreational Fisheries Catch and Effort (National Marine Fisheries Service, 2025b). Information on statistical details and current guidance for using MRIP data products was extracted from these documents and supplemented with data from MRIP’s websites. This comprehensive review informed the selection of specific data standard topics for this report. These sources were used to provide background for the review of MRIP standards; the panel did not attempt to review how these documents themselves might be improved. However, a review of the documents might be one tool for facilitating communications with the states.

In addition to the sources above, ChatGPT was used to help identify some of the key differences across surveys and appropriate references. All material generated by an artificial intelligence platform used in this document was fact-checked to ensure accuracy of the presented information.

The panel determined its greatest needs were to hear from those involved in collecting, processing, and using data on recreational fishing and from those involved in setting and applying statistical standards in other federal agencies. Given that responsibilities for recreational fishing are shared among multiple levels of government (federal, state, and regional), the panel scheduled presentations from MRIP staff, selected members of regional organizations and interstate commissions, state programs, and independent organizations. With regard to statistical standards, the panel heard from FCSM and from a consultant who has worked closely with

federal agencies on statistical standards and written about federal and international standards.

The panel inquired as to which surveys would provide the best examples for its review. Richard Cody, division director of NOAA’s Fisheries Statistics, provided the panel with a list of certified survey designs currently in use. The panel also asked NOAA what were its primary interests and sought guidance from NOAA on its expectations with regard to how the panel evaluates the adequacy of MRIP standards for meeting OMB standards. Cody responded to the latter query by affirming that while the OMB directive was a driver for the development of MRIP standards, it was not the sole factor. More specifically, he stated that although the precision standard was important, MRIP’s interests extend beyond variance thresholds. MRIP, he explained, is broadly interested in how its survey and data standards align with federal and industry best practices and in what measures are deemed appropriate for MRIP to achieve reliable, realistic, and clear performance standards and guidance for data use, particularly in the application of standards and guidance to the design and implementation of regional fisheries surveys.

Table 1-1 provides a list of all of the briefings provided to the panel by experts.11 Recognizing that approaches to measuring recreational fishing vary across geographic regions and states, the panel heard from 10 different organizations involved with collecting and monitoring statistics on recreational fishing; collectively, they represented the Atlantic coast, the Gulf states, the Northwest, the Southeast, and the Pacific coast. There was particular focus on the Gulf coast, given that these states replaced their participation in MRIP surveys with state surveys to develop coordinated but individualized surveys to meet their own needs. The panel was informed about several technical issues, ranging from sampling design, estimation methods, and the additivity of the estimates from various surveys, to approaches being taken to use app-based self reporting of catches, rates, lengths, and releases.12

In addition to hearing presentations from experts, the panel reviewed key documents available at MRIP’s website,13 methodological reports issued by selected agencies involved in collecting data on recreational fishing, and literature on relevant aspects of research methodology, particularly as it applies to fishing. The panel also used these presentations and subsequent

___________________

11 Slides from the presentations are available by going to the project webpage (https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/peer-review-of-the-marine-recreational-information-program-data-standards) and choosing specific meeting dates.

12 For important considerations relating to electronic reporting methods, see Marine Fisheries Advisory Committee (MFAC) Recreational Electronic Reporting Task Force (2022).

13 https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/recreational-fishing-data/about-marine-recreational-information-program

TABLE 1-1 List of Briefings Provided to the Panel

| Date | Type of Organization and Topic | Presenter(s) |

|---|---|---|

| NOAA / NMFS / MRIP | ||

| 4/17/25 | NOAA fisheries MRIP survey and data standards | Richard Cody, NOAA Office of Science and Technology |

| Interstate Fishery Commissions | ||

| 5/22/25 | Recreational data in stock assessments | Katie Drew, Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission |

| 5/22/25 | Review of MRIP data standards: GulfFIN Program feedback | Gregg Gray, Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission |

| 6/26/25 | Pacific Coast Recreational Fisheries Information Network (RecFIN) | Lorna Wargo, Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife; Gway Rogers-Kirchner, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife; Ryan Denton, California Department of Fish and Wildlife; Nancy Leonard, Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission |

| NOAA Cooperative Regional Fishery Programs | ||

| 4/17/25 | National Academies review: MRIP recreational fisheries survey and data standards | Geoff White, Atlantic Coastal Cooperative Statistics Program |

| 5/22/25 | Stock assessment and uncertainty | Jason Cope, Northwest Fisheries Science Center |

| 5/23/25 | National Academies peer review of MRIP’s survey and data standards | John Walter, Southeast Fisheries Science Center |

| State Agencies | ||

| 6/26/25 | National Academies peer review of MRIP’s survey and data standards | Thomas K. Frazer, University of South Florida College of Marine Science |

| 6/26/25 | National Academies MRIP data standards review | Harry Blanchet, Louisiana Department of Wildlife & Fisheries |

| 6/27/25 | National Academy of Sciences meeting | Trevor Moncrief, Mississippi Department of Marine Resources |

| Independent Organizations | ||

| 5/22/25 | Peer review of the MRIP’s recreational data collection standards | Catherine Bruger and Michael Drexler, Ocean Conservancy |

| Statistical Standards | ||

| 6/27/25 | Evaluating fitness for purpose | Robert Sivinski, Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology |

| 6/27/25 | Statistical publication rules | David Marker, Marker Consulting, LLC |

NOTE: MRIP = Marine Recreational Information Program; NMFS = National Marine Fisheries Service; NOAA = National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

discussions to secure clarifications and technical details including, but not limited to, issues pertaining to sampling frame and designs currently being implemented in MRIP surveys; estimation methods; the impact of attributes such as fishing effort and how discards and refusals are handled; the additivity and assimilation of estimators from different surveys; and approaches to incorporate data from app-based self reporting of catches, rates, lengths, and releases.

In its first three meetings, the panel combined open sessions, in which it held discussions with invited experts, and closed sessions, in which it discussed continuing data collection needs and made plans for and discussed the final report, with a particular focus on drafting and finalizing the conclusions and recommendations. Starting after the first meeting, in which a preliminary outline was created, the panel began work on preparing the report.

The panel viewed its charge to be specifically commenting on and discussing the data standards. Previous National Academies consensus reports (NASEM, 2017c, 2021a,b; National Research Council, 2006) have addressed broader questions of data use and limitation, transparency, and improvements in the design of MRIP data collection and presentation. MRIP has implemented or is in the process of implementing many of those study panels’ recommendations. This panel leaves to others any judgment on the effectiveness of MRIP’s response to those previous recommendations, apart from recommendations relevant to data standards.

OUTLINE OF THE REPORT

This report is organized as follows. This chapter (Chapter 1) provides the background for the study, noting the reasons for the study and the goals of the panel. Chapter 2 provides an overview of the panel’s perspective on the standards collectively and on a key feature (accommodating differences across states) that applies to multiple standards. Chapter 3 walks through each of the seven data quality standards, reviewing them individually. Chapter 4 discusses overall issues or larger considerations that apply to the data standards as a whole, or that reflect issues not discussed in the standards. Chapter 5 sums up this study’s key results.