Strategies to Renew Federal Facilities (2023)

Chapter: Appendix E: The Operating Context for Federal Facility Renewal Strategies

E

The Operating Context for Federal Facility Renewal Strategies

The operating context for federal facility renewal strategies can be summarized as follows: governing statutes and regulations set policy to establish agency facility asset management systems used to generate facility renewal strategies that are communicated and managed through the agency’s real property capital plan. This appendix details this operating context and supports discussions described in Chapter 2. This appendix will

- Highlight federal facility asset management authorities that set the foundation for developing and implementing federal facility renewal strategies,

- Highlight the current national strategy for federal facility asset management systems used to develop and implement federal facility renewal strategies,

- Review the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) policies as they relate to federal facility asset management and its role in advancing federal facility renewal strategies, and

- Highlight the relationship between federal facility renewal strategies and an agency’s real property capital plan.

EXECUTION OF FEDERAL FACILITY ASSET MANAGEMENT AUTHORITIES

Facility asset management authorities are established through the following:

- U.S. Code containing all permanent statutes, including those that establish general asset management authorities (e.g., disposal), and authorities for individual agencies

- Other federal laws, such as authorization and appropriations acts, that create temporary authorities regarding federal asset management

- Executive orders

- OMB circulars

- OMB memoranda

- Code of Federal Regulations

- Federal acquisition regulations

- Federal management regulations

This list shows the variety of sources that establish federal facility asset management authorities. Many of these sources, especially the U.S. Code, are tailored to specific agencies. Furthermore, individual agencies with different missions, cultures, and histories also contribute to variety in the way federal facility asset management authorities are executed. Despite these differences, federal facility asset management authorities generally agree to achieving the following objectives:

- Deliver and manage facilities necessary to achieve agency missions;

- Manage supporting resources in an efficient and effective manner;

- Comply with federal laws, regulations, priorities, and values; and

- Use facilities to generate value for the nation and the American people.

The sources listed above do not dictate how to achieve these objectives. It is therefore left to individual federal agencies to establish supporting policies, objectives, processes, and tools to manage their facility portfolios. This infers the existence of a facility asset management system while providing no way to evaluate its effectiveness, such as comparing it to an objective standard (e.g., International Organization for Standardization [ISO] 55001).

Guiding this report’s activity are two apex sources: OMB Circular A-11, “Preparation, Submission and Execution of the Budget,” and OMB Circular A-123, “Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control.” Collectively, these circulars establish policy, requirements, expectations, and guidelines governing how agencies should develop and implement federal facility renewal strategies. Requirements governing these strategies are concentrated in four areas:

- OMB Circular A-11, Section 83 (Object Classification);

- OMB Circular A-11, Part 6 (The Federal Performance Framework for Improving Program and Service Delivery) [July 2020 version];

- OMB Circular A-11’s Supplement—Capital Programming Guide; and

- OMB Circular A-123, “Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control.”

The followings sections detail how requirements are presented in each of these areas.

OMB Circular A-11, Part 6 (The Federal Performance Framework for Improving Program and Service Delivery) [Pending Reissuance in Forthcoming Guidance]

OMB Circular A-11, Part 6, starts by stating that “federal managers have an important obligation to ensure that every dollar spent delivers results for the American people” (OMB 2022b). This source developed criteria and structure for a management system to evaluate performance in agency operations and budget execution. The basis for Part 6 is the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) of 1993 and the GPRA Modernization Act of 2010. As amended, these acts established the foundation for the Federal Performance Framework, which directly influences federal facility renewal strategy development and implementation.

This is a dynamic policy area. Notably, there have been many recent advancements to the Federal Performance Framework as follows:

- Enterprise Risk Management (2016),

- Program and Project Management (2018),

- Customer Experience (2018),

- Evaluation and Evidence-Building (2019),

- Sharing Quality Services (2019), and

- Category Management (2019).

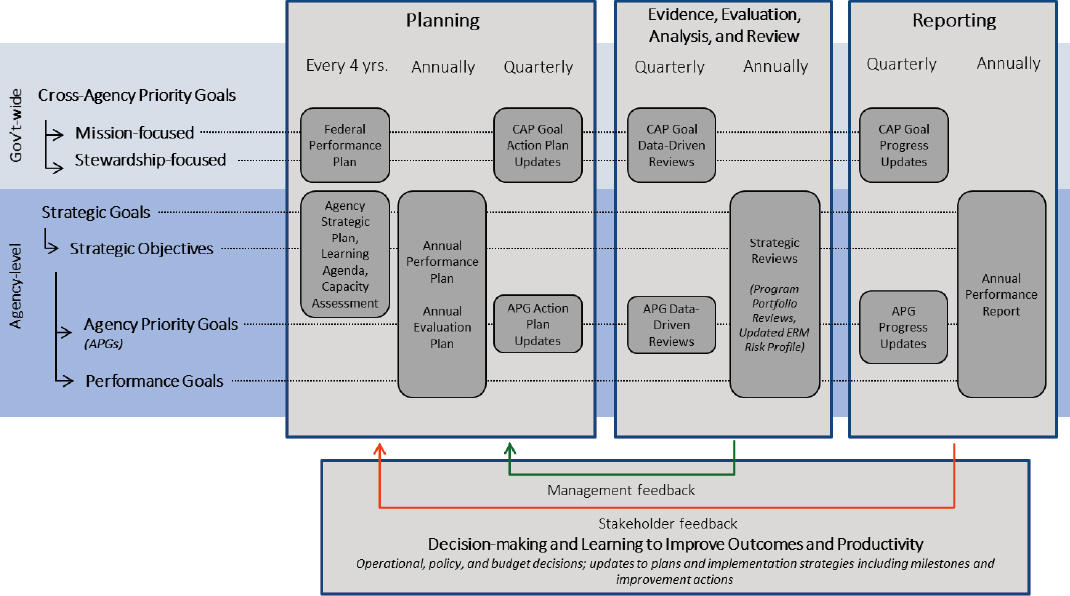

This recent activity emphasizes the Federal Performance Framework as an important, emerging management capability. These advancements began to establish asset management system requirements affecting federal facility renewal strategies. Study of this framework concluded that federal facility renewal strategies must be integral to the agency’s strategic plan and budget. To achieve this objective, agencies were guided to use the OMB Circular A-11’s Performance Management Cycle, shown in Figure E-1.

Supporting guidance did not dictate how this is to be done, but provided basic structure most agencies used, often implemented through their financial planning, programming, budgeting, and execution policies. The performance management cycle depicted how agencies could set strategic goals and objectives within a continual improvement process, an approach that is immediately

SOURCE: Office of Management and Budget, 2022, OMB Circular A-11.

applicable to federal facility renewal strategy development and implementation. Considerations for implementing this approach include the following:

- Agencies should establish policy to align their facility renewal strategies with their strategic planning, goals, priorities, and objectives;

- Consistent with OMB guidance, agencies must reconcile their federal facility renewal strategies with their budget authorities; and

- Agency strategies must serve as the basis for periodic performance analysis and reporting linked back to agency mission achievement.

This means federal facility renewal strategies cannot be merely aspirational. They must affect control over resource decision making and ensure that it links directly to agency mission objectives and priorities. Renewal strategies must therefore communicate actions responsive to requirements, dynamic changes, risk, and operating realities. In alignment with OMB Circular A-11, Part 6 requirements, agencies must create federal facility renewal strategies using objectives aligned with their strategic plans and, subsequently, periodically report performance in achieving these objectives.

OMB Circular A-11, Supplement—Capital Programming Guide

The second OMB Circular A-11 section directly influencing the development of federal facility renewal strategies is its Supplement—Capital Programming Guide. In the Guide, capital assets include land and structures that have an estimated use of more than 2 years, indicating complete agency federal facility portfolios. Facility asset costs covered under the Guide include “full life-cycle cost, including all direct and indirect costs for planning, procurement (purchase price and all other costs incurred to bring it to a form and location suitable for its intended use), operations and maintenance (including service contracts), and disposal, operations and maintenance” (OMB 2022a). The Capital Programming Guide sets its requirements as follows:

Agencies must have a disciplined capital programming process that addresses project prioritization between new assets and maintenance of existing assets, risk management and cost estimating to improve the accuracy of cost, schedule and performance provided to management, and the other difficult challenges proposed by asset management and acquisition. (OMB 2022a, p. 1)

Rather than focusing mainly on capital decisions in financial terms, the Capital Programming Guide is focused on managing capital assets and covers all resourcing decisions across facility life cycles and whole facility portfolios. Its central purpose is to maximize the return on investment generated by federal capital assets. Through this lens, the guide directs agency efforts to establish “a single, integrated capital programming process to ensure that capital assets

successfully contribute to the achievement of agency strategic goals and objectives” (OMB 2022a).

The Capital Programming Guide allows agencies flexibility in applying the guidance. However, it clarifies that the approach used must include “a long-range planning and a disciplined, integrated budget process as the basis for managing a portfolio of capital assets to achieve performance goals with the lowest lifecycle costs and least risk” (OMB 2022b). To achieve these ends, the Capital Programming Guide recognizes three management phases, each covering specific supporting elements.

- Planning and budget phase

- — Strategic and program performance linkage

- — Enterprise architecture and integrated project teams

- — Functional requirements

- — Alternatives in capital asset analysis

- — Choosing the best capital asset

- — Developing the agency capital plan

- — Submitting the agency capital plan

- Acquisition phase

- — Validate planning decisions

- — Manage acquisition risks

- — Manage acquisition activities

- — Analyze acquisition activities

- — Acquisition acceptance

- Management in-use phase

- — Objectives during management in-use

- — Management in-use operational analysis

- — Management in-use process and outcome analysis

- — Asset disposition

Throughout, the Capital Programming Guide’s purpose is to advance robust capital programming and management of all capital assets. This comes to a climax through guidance directing the development and implementation of agency capital plans. Given the focus of this study on federal facility renewal, agency capital plans, as defined in the Capital Programing Guide, are called real property capital plans in this report. Putting this into context, it is the agency’s facility asset management system that guides development of the agency’s facility renewal strategy that is implemented through the agency’s real property capital plan.

This makes the Capital Programing Guide the central policy guiding development and implementation of federal facility renewal strategies. This point is so important the committee believes if this report is to improve federal facility asset management, and hence the development and implementation of federal facility

renewal strategies, it will have to result in advancements to capital programming capabilities and guidance contained in the Capital Programming Guide and the agency policies implementing it. Simply put, the only way to systematically improve development and implementation of federal facility renewal strategies is by making improvements to the Capital Programming Guide.

OMB Circular A-123, “Management’s Responsibly for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control”

The last major source recognized in this report as having significant influence over the development and implementation of federal facility renewal strategies is OMB Circular A-123. This circular establishes requirements for managing risk using effective internal controls. These controls pertain to “all agency management, beyond the traditional ownership of OMB Circular No. A-123 by the chief financial officer community” (OMB 2016). What this means is that OMB Circular A-123 applies directly to the application of Capital Programing Guide requirements supporting the development and implementation of federal facility renewal strategies.

OMB Circular A-123 establishes risk management practices and internal controls for evaluating, operating, assessing, deficiency correcting, and reporting government performance. It refers to GAO’s Green Book (Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government [GAO-14-704G]), the GPRA Modernization Act (2010), the Federal Property Management Reform Act (2016), and ISO (e.g., ISO 31000, “Risk Management and ISO Management System Standards”) as authoritative sources promoting the integration of internal controls as part of a systematic risk management process. This relates to the development and use of federal facility renewal strategies as follows:

- Use enterprise risk management to ensure mission achievement and

- Use internal controls to ensure that objectives, stakeholder needs, and priorities are achieved.

OMB Circular A-123 establishes enterprise risk management and internal control requirements that agencies must apply through their facility asset management systems to develop and implement federal facility renewal strategies.

NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR THE EFFICIENT USE OF REAL PROPERTY

The preceding discussion on authorities invites the question, What is the national strategy for federal facility asset management? This question sheds light on the reason behind the authorities and policies just detailed. It also invites the question, Should there be a national strategy for federal facility renewal

strategies? The first question will be answered in this appendix and the second question will be answer in the form of a report recommendation. Background and the answer to the first question follows.

On March 25, 2015, OMB released the Management Procedures Memorandum 2015-01,” known as the “Reduce the Footprint” policy. This strategy expanded on successes generated by OMB Memorandum M-12-12, “Promoting Efficient Spending to Support Agency Operations,” known as the “Freeze the Footprint” policy. OMB recognized the Reduce the Footprint policy as being the first of its kind, establishing “government-wide policy to use [real] property as efficiently as possible and to reduce agency portfolios through annual reduction targets” (Executive Office of the President 2015). This strategy was followed by the release of the “National Strategy for the Efficient Use of Real Property” (National Strategy) (Executive Office of the President 2015) and was updated on March 6, 2020, through the promulgation of OMB Memorandum M-20-10, “Issuance of an Addendum to the National Strategy for the Efficient Use of Real Property.”

This National Strategy, when first released in 2015, initiated a 5-year effort designed to be an impetus to transform federal facility management generating value to the taxpayer. This National Strategy employed a three-step policy framework:

- “First, freeze growth in the real property portfolio,

- Second, measure the costs and utilization of individual real property assets to support their more efficient use, and

- Third, identify opportunities to reduce the size of the portfolio through asset disposal.” (Executive Office of the President 2015)

It further established requirements that made federal agencies responsible “for fully implementing government-wide policy and instituting a planning process to identify, budget for, and implement efficiency opportunities” (Executive Office of the President 2015). OMB updated this strategy in OMB M-20-10. In this memorandum, OMB; “recognizes that further work is needed to develop a comprehensive and final Strategy document” (OMB 2020a). The purpose of this addendum is three-fold:

- “Extend the duration of the existing Strategy and to . . . more closely align it to the PMA [President’s Management Agenda],

- Outline specific actions that can be implemented under the direction of the Federal Real Property Council (FRPC) to improve real property management and governance in the short term, and

- Outline the scope and content for a future publication of a more comprehensive national strategy for federal real property that not only takes into account the objectives outlined in this Addendum, but considers leading

- real property management practices from the private sector, state and local governments, and other national governments.” (OMB 2020a)

This addendum was released just before the earlier National Strategy was about to lapse, and it recognized limitations in that document, including that it focused solely on reducing office and warehouse space and thus “did not address optimizing the Federal portfolio as a whole, across and within agencies, for mission effectiveness and cost efficiency” (OMB 2020a). OMB views this addendum only “as an interim step toward the issuance of a comprehensive real property National Strategy” (OMB 2020a).

The stated goal in OMB M-20-10 is to “optimize the federal real property portfolio to support agency mission needs, demonstrate stewardship of taxpayer resources, manage costs through implementation of robust capital and strategic planning, develop and use detailed budget and expenditure data, and prompt legislative reform” (OMB 2020a).

OMB M-20-10 further listed four high-level challenges to optimizing the federal government’s real property:

- The first challenge is the significant constraints on available capital;

- Insufficient operating capital directly contributes to the second high-level challenge, management of the government’s legacy portfolio;

- The third major challenge is management fragmentation of the real property portfolio into isolated, agency-based communities of practice; and

- The fourth challenge is lack of integration among real property budget formulation, execution, and accounting for costs and performance within agencies. (OMB 2020a)

It lists five historic issues that hinder the federal government from making significant progress toward an optimized facility portfolio, summarized as follows:

- Issue 1: Leadership Engagement: Sufficient leadership attention has not been provided to manage real property as a strategic asset because real property is often not appreciated as an important component of mission success.

- Issue 2: Multiyear Capital Planning: The Capital Programming Guide in OMB Circular A-11 requires that agencies “must have a disciplined capital planning process that addresses project prioritization between new assets and maintenance of existing assets,” yet many agencies have either not implemented a rigorous multiyear capital planning process to allocate funding between the two, or they have not implemented capital planning at all.

- Issue 3: Business Process and Data Standards and Shared IT Solutions: The government’s capability to manage its real property portfolio suffers from a lack of standard business processes, data standards, and shared IT solutions.

- Issue 4: Alignment of Agency Internal Annual Budget Processes: In many cases, the agencies’ annual budget formulation process focuses on the cost of acquisition without adequate consideration given to out-year costs to operate, maintain, repair, and dispose the property.

- Issue 5: Federal Disposal Process: The current process under Title 40 of the U.S. Code for disposing of unneeded federal real property is burdensome and it does not provide incentives for federal managers to dispose of property or to maximize the disposal value to taxpayers. (OMB 2022a).

OMB M-20-10 then establishes the “Interim National Strategy Framework” for real property. This framework enables federal government managers to:

- Perform a comprehensive assessment of current and future mission capability gaps in the portfolio and the capital required to eliminate them;

- Establish a common, government-wide business environment where agencies adopt common business processes and standards and share IT and other tools and capabilities across government to promote better management practices and eliminate redundancy, and prevent needless expenditure of resources; and

- Identify legislative reforms that provide agency leadership with the authority needed to prioritize mission support and cost efficiency (OMB 2020a).

The Interim National Strategy then goes on to assign the Federal Real Property Council (FRPC), codified through the Federal Property Reform Act of 2016, the responsibility of leading efforts to advance framework objectives. This work is organized across three overarching strategy areas: capital planning, lifecycle execution, and root-cause analysis. The committee recognizes this evolving national strategy as the natural focal point for providing guidance supporting the development, implementation, and coordination of federal facility renewal strategies across all federal agencies.

So, in answer to the first question (What is the national strategy for federal facility asset management?), the national strategy should evolve from the Interim National Strategy commissioned by OMB M-20-10 and guided by the FRPC. The committee’s only point of concern with this approach is to recognize and correct for the bias contained in current policies, as detailed in the next section, and align efforts behind a facility asset management perspective before trying to clarify and improve current policy guidance. This issue is covered in detail in Chapter 3, which contrasts the idea of managing assets and with that of asset management.

In addition, although this guidance is missing in OMB M-20-10, the committee assumes that the FRPC will also address what role real property capital plans, introduced in OMB M-20-03, will have in the national strategy. Now finally, the answer to the second question (Should there be a national strategy for federal facility renewal strategies?): The committee has answered this question in the form of Recommendation 3 (see Chapter 7), on updating the National Strategy for the Efficient Use of Real Property based on asset management system thinking.

REVIEW OF OMB POLICY SUPPORTIVE OF FEDERAL FACILITY RENEWAL STRATEGIES

This next section reviews OMB policies outlined earlier and identifies opportunities to improve federal facility renewal strategy implementation.

OMB Circular A-11, Part 6 (The Federal Performance Framework for Improving Program and Service Delivery)

OMB A-11, Part 6, highlights the importance of performance data in supporting decision making. Specifically, it is to ensure the achievement of agency mission objectives starting with cross-agency priority goals and strategic goals. The observed problem with OMB policy in this area is that it fails to make clear how this structure directly links to budget development and how other defined plans in OMB Circular A-11 (e.g., the agency capital plan detailed in the Capital Programming Guide) are to be integrated into the performance framework.

This criticism is based on the logic that agency capital plans (called “real property capital plans” in this report) are the product of the agency’s facility renewal strategy. For instance, does OMB view agency capital plan development and management as being explicitly covered under Federal Performance Framework and OMB Circular A-123 requirements? If so, to what extent are or should agency capital plans be addressed through requirements contained in OMB Circular A-136, “Financial Reporting Requirements”? These are complex issues, but given that facilities represent the second or third largest cost center in most federal agency budgets, the emphasis on effective policy is merited. OMB policy should establish clear requirements for robust facility asset management systems used to generate federal facility renewal strategies communicated through real property capital plans.

OMB Circular A-11, Supplement—Capital Programming Guide

The Capital Programming Guide (the Guide) is developed to:

Help establish a capital programming process within each component and across the organization. Effective capital programming uses long range planning and

a disciplined, integrated budget process as the basis for managing a portfolio of capital assets to achieve performance goals with the lowest life-cycle costs and least risk. (OMB 2022a, p. 1)

The introduction to the Guide continues by stating:

Agencies have flexibility in how they implement the key principles and concepts of the Guide. They are expected to comply with existing statutes and guidance (cited in the text where appropriate) for planning and funding new assets; achieving cost, schedule, and performance goals; and managing the operation of assets to achieve the asset’s performance and life-cycle cost goals. However, the key principles and importance of thorough planning, risk management, full funding, portfolio analysis, performance-based acquisition management, accountability for achieving the established goals, and cost-effective lifecycle management will not change. In general, OMB will only consider recommending for funding in the President’s Budget priority capital asset investments that comply with good capital programming principles. This Guide does not discuss the entire strategic planning process, only that portion that pertains to the contribution of capital assets. (OMB 2022a, p. 1)

The first quote is a helpful synopsis of the Guide, and overall, the Guide is excellent policy, except in the area of supporting implementation of federal facility renewal strategies, for three reasons: (1) guidance is biased toward major system and information technology (IT) acquisition, (2) the Guide does not adequately address facility portfolio management needs, and (3) the Guide does not provide a basis to evaluate facility asset management system capabilities needed to implement federal facility renewal strategies.

To frame the first criticism, the Guide provides specific guidance generalized across three types of capital assets: major systems, IT, and real property. Furthermore, the Guide emphasizes that its purpose is on programming, despite commenting that it covers the life cycle of these assets viewed from a portfolio perspective. The immediate problem with this is that programming related to major systems and IT assets focuses on acquisition decision making governed by federal acquisition regulations (FARs), Part 34—Major System Acquisition and Part 39—Acquisition of Information Technology. Requirements contained in these regulations are measurably different from how real property is acquired and managed. Real property is acquired through construction, purchase, or leases governed by FAR Part 36—Construction and Architect-Engineer Contracts and per U.S. Code Title 40—Public Buildings, Property, and Works. In the context established in the Guide, much of the generalized programming guidance does not apply to real property, which complicates its application and relevance to federal facility renewal strategy implementation.

The second criticism is related to the Guide not having a portfolio perspective supportive of the way real property is managed. The Guide emphasizes

acquisitions as one investment decision at a time, typically defined in terms of a project or a program, and highlights the importance of portfolio management, but only from the perspective of diversification akin to financial asset management and the need to maximize return to the taxpayer. This view of portfolio management focuses attention on prioritizing one asset acquisition alternative over another, as is common in major systems and IT acquisitions.

Agencies perform this type of analysis of alternatives when making major facility capital funding decisions. However, this perspective does not reflect how agencies manage facility portfolios. Specifically, agencies measure benefits derived from investments in individual facility assets across decades as part of a large, interdependent, and often geographically distributed asset portfolio. In facility asset management terms, agencies do not only evaluate the value proposition of one asset at a time, but also the contribution of each asset to the value generated by the facility portfolio in perpetuity. The Guide does not address this issue, and by its omission, makes developing federal facility renewal strategies difficult for agencies.

The last criticism is in part related to the second quote from the Guide’s introduction provided above. Simply, the Guide provides a large volume of guidance that generally does not pertain to facility management, yet is considered clear and encompassing. As detailed in this report, implementation of federal facility renewal strategies is predicated on agencies having a fully functioning facility asset management system. The combination of these two points means agencies are not well guided on how to implement facility asset management systems needed to generate federal facility renewal strategies. The Guide should do this but does not. This point is underscored by GAO-19-57 stating that federal agencies do not have the knowledge needed to implement effective facility asset management systems. The committee believes that this issue can be remedied through implementation of the facility asset management system maturity principle introduced in Chapter 3 and further developed in Appendix F.

OMB Circular A-123, “Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control”

OMB Circular A-123 is an excellent source of guidance related to enterprise risk management and internal controls. Although the Capital Programming Guide does not thoroughly integrate this complex subject, such as through citation and application of OMB Circular A-123 references, Circulars A-11 and A-123 both make statements delegating responsibilities to agencies to establish policies, strategies, and processes for implementing suitable enterprise risk management and internal controls. These two circulars also frequently refer to management systems in terms of enterprise risk management systems, financial management systems, performance management systems, earned value management systems, acquisition management systems, and information management systems. They do not call out at any point the need for an asset management system.

As a result, the guidance on management system thinking is scattered, lacks clear organizing principles, and lacks important asset management system criteria needed to develop federal facility renewal strategies. As a result of this scattered management system thinking, implementation of A-123 guidance with implementation of A-11 requirements is not clear or helpful to developing federal facility renewal strategies. The committee believes that the best place to address this issue is within OMB Circular A-123. This could be remedied by improving OMB’s use of management system structures and standards, such as those established by the ISO, including the ISO 55000 standards series. A similar observation is made in GAO-19-57, Federal Real Property Asset Management, Agencies Could Benefit from Additional Information on Leading Practices (GAO 2018f), as highlighted earlier and detailed in Chapter 2.

Rather than focusing on the many effective, well-working OMB policy elements, this review of OMB policies highlights gaps the committee recognized that are limiting implementation of federal facility renewal strategies. In practice, both must be understood to successfully generate federal facility renewal strategies. As observed by the committee, and as called out in OMB M-20-10, some agencies have done this well and others have not. The committee’s belief is that all federal agencies would benefit from better OMB guidance, particularly related to the areas enumerated above.

REAL PROPERTY CAPITAL PLANS

The last area to highlight defining the operating context for federal facility renewal strategies is real property capital plans. This is the last topic covered because it is also the newest policy contribution related to implementation of federal facility renewal strategies released by OMB. The Capital Programming Guide “encourages” the use of an agency capital plan (i.e., an agency’s real property capital plan). As detailed earlier, this plan is to cover management of the agency’s facility portfolio. Furthermore, the use of the operative word encourages, when combined with detailed expectations in OMB Circular A-11, only implies the existence of real property capital plans.

Interestingly, it was not until OMB promulgated Memorandum M-20-03 on November 6, 2019, that agencies were required to submit a capital plan for real property. This memorandum requires that agencies compile and submit specific content to the FRPC annually to demonstrate their use of a robust capital planning process and evidence of a real property capital plan. OMB M-20-03 states that real property strategies should be a recognizable element in agency strategic plans, and these strategies should be reviewed annually as required by the Program Management Improvement Accountability Act. While the committee recognizes the promulgation of this memo as a large, positive advancement in developing real property capital plans, it believes that more needs to be done in this area, as detailed in Recommendation 2 (see Chapter 7).