Charting a Future for Sequencing RNA and Its Modifications: A New Era for Biology and Medicine (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

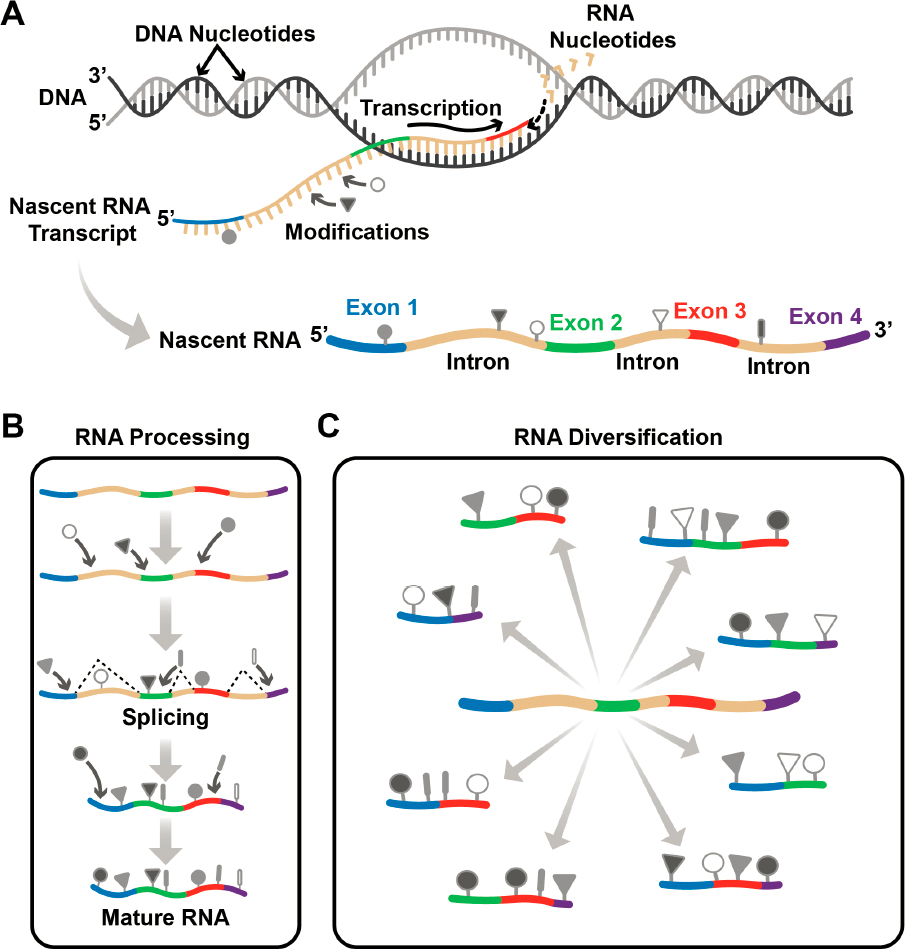

The Human Genome Project (HGP) ultimately revealed a DNA sequence of 3 billion base pairs known as the human genome,1 spurring an enormous technological advance in scientific research and the diagnosis and treatment of disease. But life does not happen with a DNA sequence alone, and the logical next step is to understand the intricacies and functionality of the molecules encoded by the human genome. The process through which information in a genome is passed to living cells to create and sustain life is fascinating and complex. It starts with the transfer of the information stored in DNA to a related molecule, called ribonucleic acid (RNA), through a process called transcription (Figure 1-1A). Transcription involves a one-to-one copying mechanism, whereby every nucleotide in the DNA sequence is transcribed to an RNA nucleotide. But the information in DNA is not enough to specify life’s complexity. In the next step, called RNA processing (Figure 1-1B), the nascent RNA transcript from a single gene2 is subject to a cut-and-paste method called splicing, whereby a single gene can give rise to hundreds, in some cases thousands, of distinct RNA molecules, or isoforms, each of which contains subsets of the original RNA sequence. Thus, genetic information is pieced together in diverse ways (Marasco and Kornblihtt, 2023; Wright, Smith, and Jiggins, 2022). Importantly, RNA molecules are also subject to numerous modifications that expand and alter its chemical structure (Figure 1-1B).

As this report details, RNA modifications play essential roles in the cell, and their dysfunction has implications in health and disease. Despite their importance, and even with a growing field of research and technology to understand RNA modifications, much remains unknown. This report provides guidelines and sets goals that will foster the technology and infrastructure needed to enable, for any cell type of any organism, the complete end-to-end sequencing of its

___________________

1 Three billion base pairs correspond to a haploid genome; current discussions note the importance of diploid information (Miga and Eichler, 2023) and a more diverse reference sequence. For example, the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium seeks to better represent the genomic landscape of diverse humans (Ballouz et al., 2019).

2 See https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Gene (accessed October 27, 2023).

epitranscriptome,3 a term defined in this report as modifications in all RNA molecules, including those in distinct RNA isoforms in a given cell type under defined conditions. The committee envisions a day when basic and clinical researchers, patients, and the interested public can access an accurate representation of any mature RNA,4 modifications included, to enable their research or understand their disease. Further, the committee hopes to see this information translated to useful medicines, materials, and biotechnologies that improve societal well-being.

Without a much deeper understanding of the role that RNA modifications play in the cell, the ability to understand the underpinnings of health and disease is severely limited. Knowing that a specific variant in a specific DNA sequence, or gene, leads to disease provides important clues as to the cause of the disease. However, in many cases, it is possible to be certain of the cause and move towards designing treatment strategies only by knowing the full array of RNA molecules transcribed from the gene.

In its essence, the goal of all biomedical science is to relieve suffering and maintain human health. An investment in epitranscriptomics can fundamentally impact the trajectory of cancer research, vaccine development, and personalized medicine. However, as this report will detail, enhanced access to knowledge about RNA modifications will also have critical impact on several areas of research beyond health and medicine.

THE LIFE OF AN RNA

Once an RNA has been transcribed and processed (Figure 1-1), it is called mature RNA and is fully functional. There are many different types of RNA, but three will be discussed several times in this report, because they are essential for the survival of all organisms: messenger RNA (mRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), and transfer RNA (tRNA).

mRNAs encode the information to make proteins and thus are referred to as coding RNAs. The word protein comes from the Greek word prōteîos, meaning “of utmost importance”; indeed, proteins are present in every cell of every organism, comprise 20 percent of the human body, and serve myriad functions. They act as biological catalysts, or enzymes, that allow reactions to occur on a timescale consistent with life. Additionally, proteins give cells shape and are the building blocks for many parts of the human body, including hair, nails, and muscles. They also pass signals from one part of an organism to another.

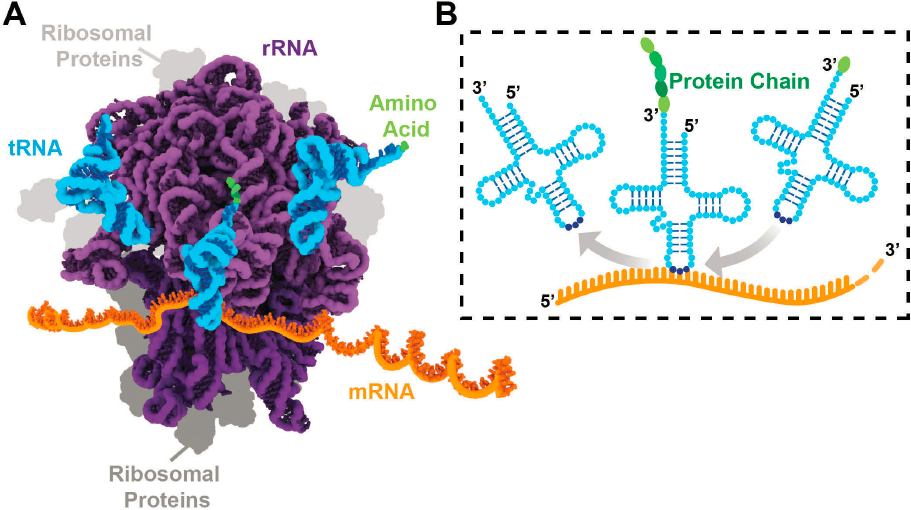

Because mRNAs encode the information necessary to make proteins, they play an incredibly important role. However, rRNA and tRNA, referred to as noncoding RNAs, are themselves essential for decoding the messages in mRNA to make a protein, a process called protein synthesis or translation. As illustrated in Figure 1-2A, rRNAs assemble with numerous proteins to create a large, macromolecular machine called the ribosome that binds to and reads mRNAs. tRNAs are

___________________

3 The term epitranscriptome refers to the chemical modifications that occur throughout all RNAs in a cell or sample of interest (the transcriptome). In many ways, this concept is analogous to the chemical modifications that comprise the epigenome, as both terms revolve around the idea of a chemical modification that acts as an additional layer on top of (epi = on/above) the nucleic acid sequence.

4 In some organisms, including humans, the length of a gene with its intronic sequences can be many times the length of the mature RNA; an example is the CNTNAP2 gene, which is more than 200 times the length of the spliced, mature messenger RNA (Hnilicová and Staněk, 2011; Scherer, 2008). While this committee’s focus is on enabling the end-to-end sequencing of all mature RNAs, it recognizes that important regulatory information can be encoded in introns or other immature RNA sequences. At this point in time, sequencing all immature transcripts from end-to-end increases the challenge exponentially. Therefore, the committee recommends that end-to-end sequencing of mature RNAs and their modifications be the initial goal. However, technologies developed to achieve this goal may also enable sequencing of some immature RNAs—for instance, those whose introns are within the size limits of long-read sequencing technologies. These technologies may then be further improved to eventually enable end-to-end sequencing of all, or a great number, of immature RNAs and their modifications.

aptly named because they facilitate the “transfer” of the information in the mRNA to the synthesis of a protein. A triplet of tRNA nucleotides base-pair with three of the letters, or nucleotides, in the mRNA (Box 1-1, Figure 1-2B); each unique triplet of letters specifies the particular protein building block, called an amino acid, brought by the tRNA to the ribosome for insertion at a particular site as the protein is being assembled.

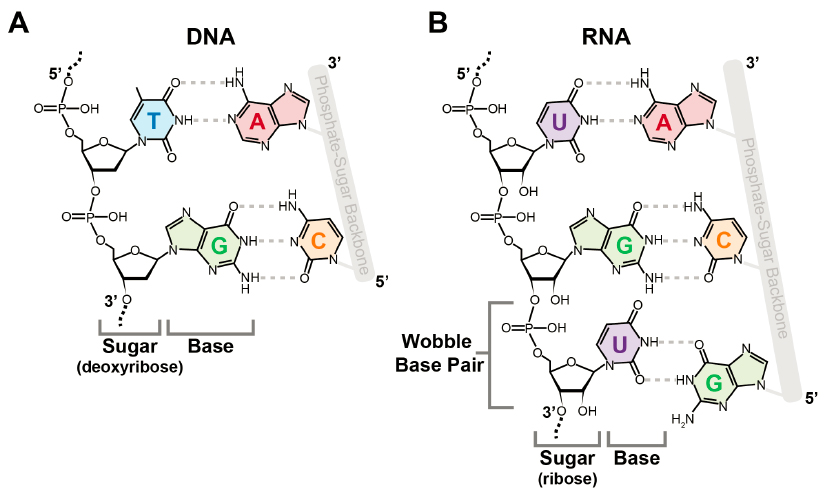

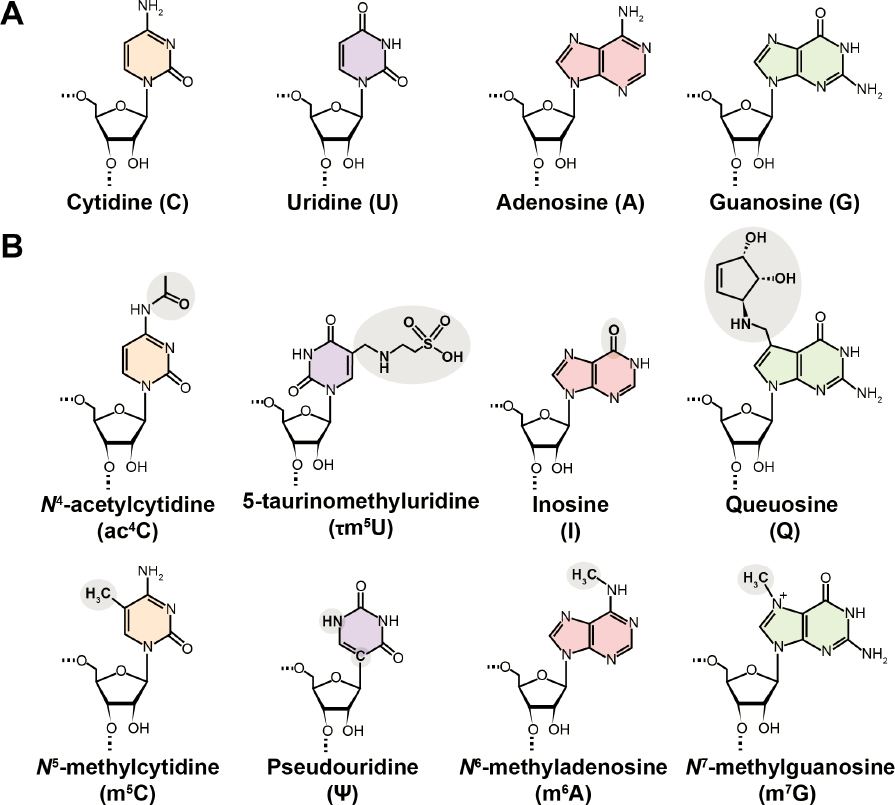

DNA and RNA are both composed of only four different nucleotides (Figures 1-3 and 1-4A), but because they can be ordered in many ways, they can store a vast amount of information. Furthermore, DNA and RNA nucleotides can be modified with distinct chemical groups that add yet another layer of information. The scale and diversity of these modifications is an order of magnitude greater for RNA. While just over 17 modified nucleotides have been identified for DNA (Zhao et al., 2020), more than 170 have been discovered for RNA, some of which are shown in Figure 1-3B. All RNAs—coding and noncoding—are decorated with chemical modifications, many of which have essential functions and several of which perform multiple functional roles in the cell. Understanding the full picture of the biological functions of RNA modifications will be impossible without a complete determination of many epitranscriptomes representing different cell types, tissues, and organisms. What is already known about RNA modifications, and their roles in basic biology, health, disease, and other important areas, is described in detail in Chapter 2.

BOX 1-1

DNA and RNA Base-Pairing

In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick reported the double-helical structure of DNA, based on the X-ray diffraction pattern acquired by Rosalind Franklin and shown to them by Maurice Wilkins and Max Perutz (NLM, n.d.). Key to their discovery was the realization that the two strands of the double helix are held together by precise pairing between the base of each nucleotide—guanine (G) with cytosine (C) and adenine (A) with thymine (T) (Watson and Crick, 1953)—fitting nicely into the rules that Erwin Chargaff had previously determined for their stoichiometry (Figure 1-3A). A similar “base-pairing” scheme exists for RNA, although RNA contains uracil (U) instead of T (Agris et al., 2018; Crick, 1966) (Figure 1-3B). Base pairs between DNA and RNA enable the information transfer during transcription.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF RNA MODIFICATIONS RESEARCH

The 1951 discovery of the first RNA modification, pseudouridine (Ψ) (Figure 1-4B), set off a flurry of excitement with some scientists declaring that the fifth nucleotide had been discovered (Cohn, 1959; Cohn and Volkin, 1951; Davis and Allen, 1957; Yu and Allen, 1959). The discovery was made by digesting total cellular RNA to its constituent building blocks, followed by separation to resolve the individual species. The coupling of separation methods to mass spectrometry in the mid-1980s substantially increased analysis throughput, paving the way for the determination of structures of more complicated RNA modifications (see, e.g., Figure 1-5). By the mid-1990s, 93 RNA modifications had been reported (Limbach, Crain, and McCloskey, 1994).

Early protocols used to separate RNAs and identify their modifications were beset by low sensitivity, which meant they would detect only the most abundant cellular RNAs: tRNA and rRNA. In addition, early methods did not provide “positional” information about where in the linear RNA sequence the modifications occurred. That began to change in the mid-1960s, when Robert Holley, who shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this work, determined the linear structure

NOTES: From 5’ to 3’: N1-methyladenosine (m1A, red), N2-methylguanosine (m2G, green), pseudouridine (Ψ, purple), queuosine (Q, green), Ψ (purple), Ψ (purple), and N5-methylcytidine (m5C, orange). The anticodon5F is QUG (green, purple, green), and each circle is outlined in dark blue. See https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Anticodon (accessed November 14, 2023).

SOURCE: Adapted from Suzuki et al., 2020. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

of a tRNA, including a subset of its modified nucleotides (Holley et al., 1965). While it represented a clear leap forward, the methodology was tedious. Rather than digesting the RNA completely into its constituents, it involved digesting it into small pieces that could provide some sequence context for the purposes of positional mapping.

One of the modifications revealed by Holley’s tRNA structure was that of inosine (Figure 1-4B), a modification that led Francis Crick to propose the wobble hypothesis (Agris et al., 2018; Crick, 1966). Since inosine can efficiently base-pair with all nucleotides (in contrast to the specific base-pairing of the canonical nucleotides shown in Box 1-1) (Martin et al., 1985), it explained how a minimal number of tRNAs could code for all of the amino acids necessary to build a protein (Crick, 1966). This provided one of the first hints that RNA modifications had biological roles.

However, whether the presence of RNA modifications indeed impacted function remained controversial for decades. Manipulations that led to the disappearance of a modification typically had negligible effect on the growth of yeast (Phillips and Kjellin-Stråby, 1967). Similarly, while function was suggested by the clustering of other modifications such as pseudouridine (Ψ) and methylated nucleotides in rRNA, their importance was questioned because of the numerous differences in Ψ content observed between bacterial and eukaryotic rRNAs (Singh and Lane, 1964). For decades, the prevailing opinion was that very few RNA modifications had important biological

functions; it was not until the mid-1990s that technological advances available to researchers allowed the detection of essential functions. It is now overwhelmingly clear that tRNA modifications are important for stabilizing its structure, as they ensure that the tRNA is charged with the correct amino acid and maintain accuracy in codon57 recognition (Figure 1-2). Modifications also fine-tune the intricate interactions that each tRNA makes with the ribosome during protein synthesis (Figure 1-2) (Suzuki, 2021).

Similarly, modifications in rRNA stabilize its three-dimensional structure and thus are important for the efficiency and accuracy of translation and assembly (Polikanov et al., 2015; Sloan et al., 2017; Yelland et al., 2023). Increasingly, it is recognized that modifications are important for regulation of protein synthesis in response to metabolites and environmental stress, and that aberrant modification in many RNA species, including tRNA, is linked to disease (Suzuki, 2021) (Box 1-2). Yet even now, not all of the roles of RNA modifications in tRNA and rRNA are known.

In the early days, few studies considered RNA modifications in mRNA, simply because its low abundance made detection with early methods impossible. However, in the mid-1970s, protocols using new detection and purification technologies led to the heroic discovery of the 5’ N7-methyl-guanosine “cap,” m6A, and 2’-O-methylation (Nm) of ribose in mRNA (Desrosiers, Friderici, and Rottman, 1974; Wei, Gershowitz, and Moss, 1975). An important aspect of these studies was a purification method called sucrose density centrifugation, which reduced contamination of mRNA samples by other RNA types, such as tRNA and rRNA. Despite introduction of this purification methodology, contamination issues continue to this day to confound the identification of modified nucleosides in mRNA.

The advent of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and automated DNA sequencing techniques ushered in by the HGP were crucial to discoveries of additional RNA modifications in

BOX 1-2

tRNA Modopathies: The Importance of Modifications in Health and Disease

A number of transfer RNA (tRNA) modifications are directly or indirectly implicated in health and disease (Orellana, Siegal, and Gregory, 2022; Suzuki, 2021). Generally, either variants in genes that encode modification enzymes or sequence variants in the tRNA gene itself can lead to alterations in the type and content of tRNA modifications at both single and multiple sites, ultimately leading to cell malfunction. tRNA modification alterations now represent new pathologies collectively referred to as tRNA modopathies (Chujo and Tomizawa, 2021), whereby any alteration in the normal level of a particular modification is associated directly with a disease. For example, a variant that prevents modification of mitochondrial tRNAs with the nutrient taurine is directly linked to the onset of two rare yet devastating and incurable mitochondrial disorders: mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS), and myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers (MERRF) (Suzuki et al., 2002).

Some modifications are so widespread across tissues and organisms that their alterations can manifest in different ways depending on the physiological state of a particular cell, tissue, or organism. In such cases, modification imbalances are connected to multivariate modopathies. For example, the deficiencies in the modification queuosine have been implicated in several metabolic and neurological disorders and types of cancer (Bednářová et al., 2017; Hayes et al., 2020). Importantly, modification of tRNA with queuosine (structure shown in Figure 1-4B) depends on the availability of the micronutrient queuine, made by bacteria and obtained by humans from diet or the gut microbiome, thus directly connecting RNA modification with what humans eat (Fergus et al., 2015). These examples illustrate that modifications, or the lack thereof, at specific sites in the RNA can have significant impacts on health and disease. Learning how these modification imbalances are impacted by a cell’s environment will be necessary to directly connect diagnosis and treatment.

___________________

5 See https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Codon (accessed October 27, 2023).

the 1980s, especially those in mRNAs. A highlight was the discovery that canonical nucleotides (phosphorylated cytidine [C], uridine [U], guanosine [G], adenosine [A]; Figure 1-4A) that were not genomically encoded could be inserted, deleted, or changed from one canonical nucleotide to another. These types of modification are sometimes called RNA editing and are distinguished from the often more complicated, noncanonical modifications observed in tRNA and rRNA (Figures 1-4B and 1-5). The method of comparing a genomic DNA sequence with the DNA sequence copied from RNA using an enzyme called reverse transcriptase led to discovery of the dramatic example of uridine insertion and deletion in the mitochondria of trypanosomes (Benne et al., 1986). This method also led to the discovery of the first example of RNA editing in a nuclear-encoded RNA, the mammalian mRNA encoding apolipoprotein B (Chen et al., 1987; Powell et al., 1987), which involved the deamination of a C to a U. Around the same time, double-stranded RNA injected into Xenopus laevis embryos was found to undergo adenosine to inosine (A-to-I) modification (Bass and Weintraub, 1988), and in the early 1990s the ADAR6 enzymes responsible for this deamination were identified (Bass, 2002).

In contrast to the many years that it took to understand functions of modifications of tRNA and rRNA, the biological functions of most RNA editing events were clear at the time of their discovery. For example, mRNAs of trypanosomal mitochondria rely on RNA editing to encode functional proteins; and the C-to-U editing of the apolipoprotein B mRNA alters a glutamine codon (CAA) to a stop codon (UAA), leading to two distinct proteins with tissue-specific expression that both have important roles in lipid metabolism (Chen et al., 1987; Powell et al., 1987).

The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) protocols is the most recent leap forward and has led to the current understanding of RNA and its modifications. Coupling NGS with methodologies to enrich modified RNA sometimes enables the position of each modification within an RNA sequence to be determined. In recent years this approach has catapulted the understanding of the prevalence and functions of Ψ (Martinez et al., 2022) and m6A in mRNA (Dominissini et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2012) (Figure 1-4B). However, as described in the next section, current NGS methods provide information only for short regions of an RNA, and because of the myriad RNA isoforms that can be made from a specific DNA gene (Figure 1-1C), in most cases it is still not known what combination of modified nucleotides exists together in a single, complete RNA transcript.

The State of RNA Sequencing Technologies

Technologies for DNA sequencing took a huge leap forward with the HGP, which spurred the further advances and automation of the technology known as Sanger sequencing. With this then state-of-the-art instrumentation, sequencing of nearly all of the 3 billion base pairs of the human genome took 3–4 years at a cost of about $300 million7 (von Bubnoff, 2008). While Sanger sequencing was revolutionary at the time, the later development of NGS protocols brought speed at low cost, and today, a lab with even a modest budget can use these techniques on a routine basis at less than $1,000 per genome.

As with most nucleic acid sequencing methods, NGS methods use DNA. So, for RNA applications, again, the enzyme called reverse transcriptase must first be used to convert the RNA into DNA. Current methodology typically generates read lengths from 100 to 300 base pairs (Stark, Grzelak, and Hadfield, 2019), and increasingly sophisticated software assembles these “short reads” together and aligns predicted RNA isoforms to the genome. NGS methods have enabled substantial

___________________

6 ADAR stands for adenosine deaminase acting on RNA.

7 This figure should not be confused with the total cost of the HGP, which is estimated to be $2.7 billion over 13 years for the U.S. scientific activities that fell under the project umbrella, including associated costs but excluding costs incurred by other countries that participated in the HGP. See https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/Sequencing-Human-Genome-cost (accessed March 11, 2024).

progress toward realizing the transcriptome of many organisms, and it is common for scientists to use freely available genome browsers to visualize transcriptomes of interest.

Popular short-read sequencing protocols for RNA sequencing represent RNA isoforms that might exist. However, because it is not known which of the short reads uniquely combine with others to create a single transcript, which isoforms actually exist is often ambiguous (Wright, Smith, and Jiggins, 2022). Further, only a few RNA modifications can be detected with current NGS protocols. Figure 1-6 illustrates that, although long-read protocols reveal that a specific gene generates two isoforms with two common and two distinct exons, each with m6A modifications in different sites, current short-read RNA sequencing methods cannot distinguish this level of detail.

An exciting recent development is third-generation sequencing (TGS), which involves sequencing single RNA molecules directly from one end to the other without requiring fragmentation or PCR amplification. TGS methods can generate reads of up to 50 kilobases and seem certain to be part of the solution to sequencing the entire epitranscriptome. These methods have the potential to shed light on the predicted roles of alternative splicing in tissue- and species-specific differentiation

NOTES: (A) Gene “n” is transcribed to generate a nascent transcript, which is then spliced and modified in two different ways to form two isoforms, green and blue. (B) Since both isoforms contain the first two exons, short reads from these exons are ambiguous and cannot distinguish between the two isoforms. Reads that map across the splice junctions for these first two exons also cannot distinguish between the two isoforms. However, short reads that map to exons that are unique to either isoform are unambiguous, as are those that cross the splice junctions unique to each isoform. Long-read complementary DNA (cDNA) sequencing can unambiguously identify the two splice isoforms, but in most cases cannot provide information about RNA modifications. Direct RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) can distinguish the two splice isoforms unambiguously and can also provide this information for a small subset of known modifications.

SOURCE: Stark, Grzelak, and Hadfield, 2019. Published and licensed by Springer Nature.

and its contribution to a wide range of diseases, from cancer to autism spectrum disorders (Marasco and Kornblihtt, 2023). However, current TGS direct-sequencing methodologies have low throughput and high error rates, and they can detect only a small subset of RNA modifications.

KEY COMPONENTS OF A ROADMAP TO UNLOCK ANY EPITRANSCRIPTOME

There is now widespread acceptance that RNA modifications exist and are critical for life processes. Discovering all the modifications and their positions in various epitranscriptomes is an exciting challenge, but one that (in some respects) is far more challenging than that of the HGP. As is necessary for its role in storing the precious blueprint that enables an organism to develop and sustain life, DNA is a robust molecule, remaining largely intact even under harsh conditions, such as high temperatures or treatment with acid or base. Although RNA is stable at neutral pH, it can fragment easily under such harsh treatments. Indeed, the more fragile nature of RNA was brought to public awareness by certain COVID-19 mRNA vaccines that had to be frozen for long-term storage (Fang et al., 2022). Therefore, RNA samples intended for epitranscriptome sequencing must be handled with care. Furthermore, while the DNA genome for different individuals varies somewhat (~0.4 percent among humans),8 it is possible to generate a reference genomic sequence that accurately describes the DNA sequence in every cell of an individual. By contrast, the splicing and modification of an RNA differs substantially between every tissue and cell type so that the RNA can meet specific demands—for example, to specify muscle or skin (Figure 1-1C). Further diversity arises according to the age of an organism, its sex, and its environment, and recent studies in plants suggest epitranscriptomes can literally change with the weather (Artz et al., 2023; Gao et al., 2022; Shen et al., 2023). Thus, unlike a DNA genome, there is a myriad of epitranscriptomes to sequence, even within a single organism.

The HGP aimed to provide complete reference genomes for humans and model organisms; similarly, reference epitranscriptomes that represent specific cell types and conditions in both humans and a set of model organisms will be invaluable for future epitranscriptome studies (see Chapter 3). However, because there are many epitranscriptomes to determine, even for a single organism or individual, the committee is unanimous in the opinion that the ultimate and most impactful goal is to enable sequencing of any epitranscriptome. Thus, this report focuses on the development of technologies and associated infrastructure that basic and clinical researchers can use in pursuit of their epitranscriptome of interest. In addition, the epitranscriptome sequencing technologies can be used to determine sequences of existing and novel viral pathogens. Epitranscriptomics can also be used in the quality control of new RNA-based biotechnologies, such as mRNA vaccines and other RNA therapeutic agents, because many of these technologies require RNA modifications to ensure that they are safe and effective.

As detailed in ensuing chapters and illustrated in Figure 1-7, the committee envisions that multiple efforts in the following areas will need to occur together.

- Expanding Research Efforts: Ongoing research in the field of RNA modifications must continue and expand. Fundamental research will be critical for identifying the location of known modifications, discovering additional modifications, and uncovering the functional importance of every modification. New funding mechanisms and opportunities to convene key groups invested in this challenge, domestically and internationally, will be critical to encourage collaboration and innovation and increase interest in RNA modifications research.

___________________

8 See https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/educational-resources/fact-sheets/human-genomic-variation (accessed January 15, 2024).

NOTES: Expanding research; advancing experimental and computational tools and technology; developing references and standards of various types; establishing stable, integrated, and centralized data resources; and cultivating innovation across several dimensions, including workforce development, are necessary to fully reveal any epitranscriptome.

- Advancing Tools and Technologies: Next-generation and third-generation sequencing tools can sequence RNA and identify a small subset of the more than 170 RNA modifications, but each method suffers from some limitations. There is a strong need in the field to improve the sensitivity, specificity, and throughput of technologies that currently exist, and to explore new and emerging instrumentation and methodologies to enhance the capabilities for sequencing RNA modifications and determining their abundance and stoichiometry. In addition, mass spectrometry methods, which are valuable for both global modification measurements and direct sequencing of short RNAs, also suffer from methodological challenges, such as sample requirements, sequencing length, and cost of use. Enhancing computational capabilities will play a central role in advancing this effort and therefore need to be considered at every stage. New algorithms for basecalling; bioinformatic platforms; and, potentially, predictive methods that employ machine learning and artificial intelligence could come into play.

- Developing Standards: There is a pressing need for standards in order for the field to progress. These include physical standards, such as naturally occurring modified nucleotides or RNA molecules containing the modifications in different sequence contexts; data standards that include quality control and universal nomenclature; and database standards that adhere to FAIR (findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability) principles.

- Centralizing Data Resources: Understanding what research and information already exist in the field of RNA modifications can be the basis for building a centralized knowledge base. Part of this effort is understanding what databases are needed for researchers and other practitioners who will be using RNA modification information. A centrally administered database (or ensemble of databases) will also serve as the repository for future discoveries about RNA modifications, including their locations within RNAs, effects on structure, macromolecular interactions, and roles in health and disease.

- Cultivating Innovation: While the components listed above will help drive innovation, other factors are essential for transforming the field of RNA modifications. These other drivers include a well-trained, informed, and diverse workforce; centralized facilities suited to specialized tasks; readily available high-quality reagents and research materials; organization and coordination at the national and international levels; and a supportive policy environment.

STUDY SCOPE AND APPROACH

The central purpose of this report is to develop a roadmap to guide the development of tools, technologies, and infrastructure that are needed to realize the capability of sequencing any RNA, including all of its modifications, in a robust and accessible way. To develop this roadmap, the committee was guided by a statement of task (Box 1-3) that specified areas of focus, including scientific, technical, computational, policy, infrastructure, and workforce needs. The committee carefully considered each component of the statement of task and designed a series of information-gathering activities to collect a diverse set of perspectives related to each topic area.

The committee began its information-gathering process by reviewing previous workshops and literature related to the field of RNA modifications, including a recording and report from an NIH

BOX 1-3

Statement of Task

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will convene an ad hoc committee to conduct a study on direct sequencing of modifications of RNA (referred to as epitranscriptome) from humans and model organisms. As part of this study, the committee will develop a roadmap for achieving direct sequencing of modifications of RNA. The National Academies’ committee will examine:

- Scientific needs for sequencing of modifications of RNA.

- Current RNA sequencing methodologies and technologies and their limitations, documenting which RNA bases and modifications are sequenced and whether the RNA is sequenced directly or indirectly.

- Current RNA and RNomea databases, including the types of RNA included, the organisms from which the RNA sequences were obtained, and limitations of the databases.

- Challenges in scientific, clinical, and public health analyses associated with current RNA sequencing methodologies and technologies.

- Scientific and technological hurdles including computational and analytic technologies that need to be overcome to achieve direct sequencing of RNA modifications.

- Computational and analytic technologies needed to analyze modified RNA.

- Data ecosystem needs for supporting sequencing and analysis of RNA modifications.

- Policy, workforce, and infrastructure needs to support sequencing and analysis of RNA modifications.

- Potential for existing and new technologies to discover previously unrecognized RNA modifications.

The National Academies will produce a consensus study report that focuses on defining the science and technology roadmap and actionable recommendations toward achievement of direct sequencing of RNA modifications. During the study, the committee will hold a series of coordinated activities (e.g., workshops, meeting of experts, ideation challenges) to provide platforms for creative collaboration among experts from multiple scientific disciplines and organizations. Individual products summarizing key outcomes from these activities may be produced as interim products of the consensus study.

__________________

a The RNome refers to all of the RNA species in a cell at a given time (Arora and Kaul, 2018).

workshop that was held in May 2022: Capturing RNA Sequence and Transcript Diversity—From Technology Innovation to Clinical Application (NIEHS, 2022). After reviewing this material, the committee designed and held a 1.5-day workshop in March 2023 that covered topics such as the current state of RNA modifications technologies, the state of RNA modification standards, the application of RNA modifications to health and medicine, and societal implications of RNA modifications research (Appendix B). In addition to this workshop, the committee held several other information-gathering sessions and meetings with experts. Over the course of the study, the committee heard from approximately 50 different speakers, panelists, and discussants (Appendixes B and C).

The committee also held an Ideation Challenge in June 2023 to encourage collaboration and spur innovation around addressing major challenges in the field of RNA modifications. As described in Appendix B, the committee brought together a group of 38 researchers to identify major challenges and work through activities to elicit solutions for addressing those challenges and technical hurdles. Three of the seven working groups were asked to expand on their ideas and write commissioned papers that would assist the committee in writing the final report (Appendix F).

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report is organized into four topic areas, covered in Chapters 2 through 5, and a final chapter dedicated to providing an overview of major conclusions, recommendations, and timelines. Chapter 2 discusses the nature of RNA modifications and summarizes what is currently known about the role of RNA modifications in basic life sciences research, as well as the various ways that knowledge has been applied to maintain health, treat disease, and provide solutions for other sectors, such as food and agriculture. Chapter 3 examines the current state of tools and technologies that exist for identifying, quantifying, and sequencing RNA modifications, including approaches for global modification measurement, indirect sequencing, direct sequencing, and associated computational tools. The chapter goes into further depth by laying out the key gaps and challenges that are not addressed by the currently available technologies and explores future areas of technology development that would impact the RNA modifications field. Chapter 4 takes an in-depth look at the current state of RNA modifications standards and databases, which will be key in supporting and advancing research and technology development efforts. The chapter discusses the types of standards and attributes of data resources that would be ideal for the future and the steps needed to accomplish goals related to future standards and databases. Chapter 5 explores the possibilities for driving innovation in the field of RNA modifications, beginning with a discussion of unmet needs for future innovation and then describing specific accelerators that will benefit the RNA modifications field. The final chapter of the report synthesizes the information from the previous chapters into a set of key conclusions and recommendations for driving the field forward. It also provides a set of interim deliverables and timelines, specifying when different goals ought to be accomplished. The whole report, taken together, provides evidence, conclusions, and recommendations for enabling the sequencing of full-length RNA molecules and their modifications to transform the field of epitranscriptomics and provide needed solutions for health, medicine, and beyond.

REFERENCES

Agris, P. F., E. R. Eruysal, A. Narendran, V. Y. P. Väre, S. Vangaveti, and S. V. Ranganathan. 2018. “Celebrating wobble decoding: Half a century and still much is new.” RNA Biology 15 (4–5): 537–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476286.2017.1356562.

Arora, M., and D. Kaul. 2018. “RNome: Evolution and nature.” In Cancer RNome: Nature & evolution, 1–78. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

Artz, O., A. Ackermann, L. Taylor, P. K. Koo, and U. V. Pedmale. 2023. “Light and temperature regulate m6A-RNA modification to regulate growth in plants.” bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.17.524395.

Ballouz, S., A. Dobin, and J. A. Gillis. 2019. “Is it time to change the reference genome?” Genome Biology 20 (1): 159. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1774-4.

Bass, B. L. 2002. “RNA editing by adenosine eeaminases that act on RNA.” Annual Review of Biochemistry 71 (1): 817–846. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135501.

Bass, B. L., and H. Weintraub. 1988. “An unwinding activity that covalently modifies its double-stranded RNA substrate.” Cell 55 (6): 1089–1098. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(88)90253-X.

Bednářová, A., M. Hanna, I. Durham, T. VanCleave, A. England, A. Chaudhuri, and N. Krishnan. 2017. “Lost in translation: Defects in transfer RNA modifications and neurological disorders.” Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2017.00135.

Benne, R., J. Van Den Burg, J. P. J. Brakenhoff, P. Sloof, J. H. Van Boom, and M. C. Tromp. 1986. “Major transcript of the frameshifted coxll gene from trypanosome mitochondria contains four nucleotides that are not encoded in the DNA.” Cell 46 (6): 819–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(86)90063-2.

Chen, S.-H., G. Habib, C.-Y. Yang, Z.-W. Gu, B. R. Lee, S.-A. Weng, S. R. Silberman, S.-J. Cai, J. P. Deslypere, M. Rosseneu, A. M. Gotto, W.-H. Li, and L. Chan. 1987. “Apolipoprotein B-48 is the product of a messenger RNA with an organ-specific in-frame stop codon.” Science 238 (4825): 363–366. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3659919.

Chujo, T., and K. Tomizawa. 2021. “Human transfer RNA modopathies: Diseases caused by aberrations in transfer RNA modifications.” The Febs Journal 288 (24): 7096–7122. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.15736.

Cohn, W. E. 1959. “5-Ribosyl uracil, a carbon-carbon ribofuranosyl nucleoside in ribonucleic acids.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 32: 569-571. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3002(59)90644-4.

Cohn, W. E., and E. Volkin. 1951. “Nucleoside-5′-phosphates from ribonucleic acid.” Nature 167 (4247): 483–484. https://doi.org/10.1038/167483a0.

Crick, F. H. C. 1966. “Codon—anticodon pairing: The wobble hypothesis.” Journal of Molecular Biology 19 (2): 548–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(66)80022-0.

Davis, F. F., and F. W. Allen. 1957. “Ribonucleic acids from yeast which contain a fifth nucleotide.” Journal of Biological Chemistry 227 (2): 907–915.

Desrosiers, R., K. Friderici, and F. Rottman. 1974. “Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 71 (10): 3971–3975. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971.

Dominissini, D., S. Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S. Schwartz, M. Salmon-Divon, L. Ungar, S. Osenberg, K. Cesarkas, J. Jacob-Hirsch, N. Amariglio, M. Kupiec, R. Sorek, and G. Rechavi. 2012. “Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq.” Nature 485 (7397): 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11112.

Fang, E., X. Liu, M. Li, Z. Zhang, L. Song, B. Zhu, X. Wu, J. Liu, D. Zhao, and Y. Li. 2022. “Advances in COVID-19 mRNA vaccine development.” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 7 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-00950-y.

Fergus, C., D. Barnes, M. A. Alqasem, and V. P. Kelly. 2015. “The queuine micronutrient: Charting a course from microbe to man.” Nutrients 7 (4): 2897–2929. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7042897.

Gao, Y., X. Liu, Y. Jin, J. Wu, S. Li, Y. Li, B. Chen, Y. Zhang, L. Wei, W. Li, R. Li, C. Lin, A. S. N. Reddy, P. Jaiswal, and L. Gu. 2022. “Drought induces epitranscriptome and proteome changes in stem-differentiating xylem of Populus trichocarpa.” Plant Physiology 190 (1): 459–479. https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiac272.

Hayes, P., C. Fergus, M. Ghanim, C. Cirzi, L. Burtnyak, C. J. McGrenaghan, F. Tuorto, D. P. Nolan, and V. P. Kelly. 2020. “Queuine micronutrient deficiency promotes warburg metabolism and reversal of the mitochondrial ATP synthase in hela cells.” Nutrients 12 (3). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030871.

Hnilicová, J., and D. Staněk. 2011. “Where splicing joins chromatin.” Nucleus 2 (3): 182–188. https://doi.org/10.4161/nucl.2.3.15876.

Holley, R.W., Everett, G. A., Madison, J.T., and Zamir, A. 1965. “Nucleotide sequences in the yeast alanine transfer ribonucleic acid.” Journal of Biological Chemistry 240: 2122–2128. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9258(18)97435-1.

Limbach, P. A., P. F. Crain, and J. A. McCloskey. 1994. “Summary: The modified nucleosides of RNA.” Nucleic Acids Research 22 (12): 2183–2196. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/22.12.2183.

Marasco, L. E., and A. R. Kornblihtt. 2023. “The physiology of alternative splicing.” Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 24 (4): 242-254. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-022-00545-z.

Martin, F. H., M. M. Castro, F. Aboul-ela, and I. Tinoco, Jr. 1985. “Base pairing involving deoxyinosine: Implications for probe design.” Nucleic Acids Research 13 (24): 8927-8938. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/13.24.8927.

Martinez, N. M., A. Su, M. C. Burns, J. K. Nussbacher, C. Schaening, S. Sathe, G. W. Yeo, and W. V. Gilbert. 2022. “Pseudouridine synthases modify human pre-mRNA co-transcriptionally and affect pre-mRNA processing.” Molecular Cell 82 (3): 645-659.E9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2021.12.023.

Meyer, K. D., Y. Saletore, P. Zumbo, O. Elemento, Christopher E. Mason, and Samie R. Jaffrey. 2012. “Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3' UTRs and near stop codons.” Cell 149 (7): 1635–1646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003.

Miga, K. H., and E. E. Eichler. 2023. “Envisioning a new era: Complete genetic information from routine, telomereto-telomere genomes.” The American Journal of Human Genetics 110 (11): 1832–1840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.09.011.

National Library of Medicine. n.d. “The discovery of the double helix, 1951–1953.” The Francis Crick Papers. https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/sc/feature/doublehelix (Accessed September 26, 2023).

NIEHS (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences). 2022. Capturing RNA sequence and transcript diversity—From technology innovation to clinical application. Report on virtual event, May 24–26, 2022. Developed by the Avanti Corporation for the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/sites/default/files/news/events/pastmtg/2022/rnaworkshop2022/workshop_report_508.pdf (accessed March 11, 2024).

Orellana, E. A., E. Siegal, and R. I. Gregory. 2022. “tRNA dysregulation and disease.” Nature Reviews Genetics 23 (11): 651-664. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-022-00501-9.

Phillips, J. H., and K. Kjellin-Stråby. 1967. “Studies on microbial ribonucleic acid: IV. Two mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae lacking N2-dimethylguanine in soluble ribonucleic acid.” Journal of Molecular Biology 26 (3): 509–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2836(67)90318-X.

Polikanov, Y. S., S. V. Melnikov, D. Söll, and T. A. Steitz. 2015. “Structural insights into the role of rRNA modifications in protein synthesis and ribosome assembly.” Natural Structure & Molecular Biology 22 (4): 342-344. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2992.

Powell, L. M., S. C. Wallis, R. J. Pease, Y. H. Edwards, T. J. Knott, and J. Scott. 1987. “A novel form of tissue-specific RNA processing produces apolipoprotein-B48 in intestine.” Cell 50 (6): 831-840. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(87)90510-1.

Scherer, S. 2008. A short guide to the human genome. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

Shen, L., J. Ma, P. Li, Y. Wu, and H. Yu. 2023. “Recent advances in the plant epitranscriptome.” Genome Biology 24 (1): 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-023-02872-6.

Singh, H., and B. G. Lane. 1964. “The alkali-stable dinucleotide sequences in 18 S + 28 S ribonucleates from wheat germ.” Canadian Journal of Biochemistry 42 (7): 1011-1021. https://doi.org/10.1139/o64-112.

Sloan, K. E., A. S. Warda, S. Sharma, K. D. Entian, D. L. J. Lafontaine, and M. T. Bohnsack. 2017. “Tuning the ribosome: The influence of rRNA modification on eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis and function.” RNA Biology 14 (9): 1138-1152. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476286.2016.1259781.

Stark, R., M. Grzelak, and J. Hadfield. 2019. “RNA sequencing: The teenage years.” Nature Reviews Genetics 20 (11): 631–656. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-019-0150-2.

Suzuki, T. 2021. “The expanding world of tRNA modifications and their disease relevance.” Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 22 (6): 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-021-00342-0.

Suzuki, T., T. Suzuki, T. Wada, K. Saigo, and K. Watanabe. 2002. “Taurine as a constituent of mitochondrial tRNAs: New insights into the functions of taurine and human mitochondrial diseases.” The Embo Journal 21 (23): 6581–6589. https://doi.org/10.1093/emboj/cdf656.

Suzuki, T., Y. Yashiro, I. Kikuchi, Y. Ishigami, H. Saito, I. Matsuzawa, S. Okada, M. Mito, S. Iwasaki, D. Ma, X. Zhao, K. Asano, H. Lin, Y. Kirino, Y. Sakaguchi, and T. Suzuki. 2020. “Complete chemical structures of human mitochondrial tRNAs.” Nature Communications 11 (1): 4269. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18068-6.

von Bubnoff, A. 2008. “Next-generation sequencing: The race is on.” Cell 132 (5): 721–723. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.028.

Watson, J. D., and F. H. Crick. 1953. “Molecular structure of nucleic acids: A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid.” Nature 171 (4356): 737–738. https://doi.org/10.1038/171737a0.

Wei, C.-M., A. Gershowitz, and B. Moss. 1975. “Methylated nucleotides block 5′ terminus of HeLa cell messenger RNA.” Cell 4 (4): 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(75)90158-0.

Wright, C. J., C. W. J. Smith, and C. D. Jiggins. 2022. “Alternative splicing as a source of phenotypic diversity.” Nature Reviews Genetics 23 (11): 697–710. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-022-00514-4.

Yelland, J. N., J. P. K. Bravo, J. J. Black, D. W. Taylor, and A. W. Johnson. 2023. “A single 2'-O-methylation of ribosomal RNA gates assembly of a functional ribosome.” Natural Structure & Molecular Biology 30 (1): 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-022-00891-8.

Yu, C.-T., and F. W. Allen. 1959. “Studies of an isomer of uridine isolated from ribonucleic acids.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 32: 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3002(59)90612-2.

Zhao, L. Y., J. Song, Y. Liu, C. X. Song, and C. Yi. 2020. “Mapping the epigenetic modifications of DNA and RNA.” Protein & Cell 11 (11): 792–808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13238-020-00733-7