Charting a Future for Sequencing RNA and Its Modifications: A New Era for Biology and Medicine (2024)

Chapter: 2 Importance and Impacts of RNA Modifications in Biology, Disease, Medicine, and Society

2

Importance and Impacts of RNA Modifications in Biology, Disease, Medicine, and Society

RNA molecules and their modifications play crucial roles in the passing of information contained in each gene to the rest of the cell, a process called gene expression. More than 170 RNA modifications have been observed in coding and noncoding RNAs in organisms from every kingdom of life (Cappannini et al., 2024). RNA modifications have broad impacts on gene expression and regulate processes that impact development, stress response, health, and disease (Roundtree et al., 2017). The addition and removal of RNA modifications is carried out by distinct proteins, in some cases with the help of guiding RNAs. Additionally, some proteins that bind RNA have an affinity for specific RNA modifications (Flamand, Tegowski, and Meyer, 2023). These RNA–protein interactions facilitate an array of activities in cells, typically by recruiting other macromolecules. This complex web of RNAs—with their modifications and the many RNA-binding and RNA-modifying proteins with which they interact—is essential for proper cellular and organismal function (Flamand, Tegowski, and Meyer, 2023; Roundtree et al., 2017; Sloan et al., 2017; Suzuki, 2021). This network is also sensitive to changes in cellular and environmental conditions.

Developing a deep understanding of these processes and the central role of RNA modifications will reveal much about basic biology. But it will also be extraordinarily useful—as it has already begun to be—in advancing human health; ameliorating disease; controlling pathogens; improving crop yields; and pushing the boundaries of synthetic biology, including nanotechnology applications. This chapter examines each of these topics, including success stories such as the N1-methylpseudouridine (N1-methyl-Ψ)–modified messenger (mRNA) vaccines against COVID-19 and the crops engineered with human RNA-modifying proteins that display enhanced yields and increased drought resistance. The chapter closes by identifying gaps in knowledge about RNA modifications and improvements needed in tools and methods to close those gaps.

WHAT ARE RNA MODIFICATIONS?

As introduced in Chapter 1, RNA modifications are chemical changes to RNA molecules that occur during or after transcription. Among the known RNA modifications, pseudouridine (Ψ), 2′-O-methylation (Nm), inosine, and N6-methyladenosine (m6A) are some of the most abundant

modifications in eukaryotic cellular RNAs (Bazak et al., 2014; Limbach and Paulines, 2017; Roundtree et al., 2017) (see Figure 1-4 in Chapter 1). RNA modifications are highly prevalent in transfer RNA (tRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) (Roundtree et al., 2017; Suzuki, 2021). Indeed, in all organisms, tRNAs are the most heavily modified RNA species in terms of number, density, and diversity; and much of what is known about RNA modifications has come from studies of tRNAs. Astoundingly, about one of every six nucleotides are modified in mammalian tRNA, and more than 50 unique modifications have been identified in eukaryotes (Cappannini et al., 2023). The modifications range from thiolations and base or sugar methylations to extensive addition of sugars, amino acids, and complex metabolic adducts. These modifications are installed by a myriad of nuclear, cytoplasmic, and mitochondrial enzymes, which can modify a single site in a single tRNA or multiple sites across several tRNA species. Complex modifications often require stepwise installation by a cascade of enzymes (e.g., wybutosine, 5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-2-thiouridine; Suzuki, 2021).

The anticodon loop is the hot spot of tRNA modification (e.g., see Figure 1-5 in Chapter 1); here, modifications facilitate translation by preventing frameshifting, expanding codon recognition, and strengthening the codon–anticodon interaction (see Figure 1-2 in Chapter 1) (Phizicky and Hopper, 2023; Smith, Giles, and Koutmou, 2024). Outside the anticodon loop, modifications influence the structure, stability, and ribosome-binding affinity of tRNA. Many modifications also affect tRNA-fragment biogenesis, which creates small RNAs that perform diverse functions in cells, and upon secretion, contribute to cell–cell communication (Muthukumar et al., 2024).

Until a decade ago, tRNA modification was thought to be stoichiometric and static. However, recent studies using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry and next-generation sequencing have shown that tRNAs are often partially modified, and the modification stoichiometry at many sites is dynamic and depends on cell type and cell state (Zhang et al., 2022). tRNA modification dynamics can be regulated through the enzymes that create the modification and their different isoforms, as well as by cellular metabolism. The latter is often the source of cofactors and substrates needed to form the modifications, such as S-adenosyl-methionine for methylation. Furthermore, in mammals, modification levels can also be altered by enzymes that remove the modifications; researchers have coined the word erasers to classify such proteins.

Implicit in the diverse and dynamic nature of modifications are their multivariate functions. The latter makes it particularly challenging to unveil their full importance, especially in terms of medical relevance. For example, if one tRNA modification affects several different pathways, or one tRNA-modifying enzyme targets multiple tRNAs, it is difficult to assign a particular disease to one function.

Clearly, the general lack of suitable technologies to study modifications precisely has made matters more difficult. Nonetheless, through the years, medical implications for RNA modifications in human health and disease have steadily become apparent. This is true in particular with tRNAs. For example, more than 100 different mitochondrial diseases have been ascribed to variants in the human mitochondrial genome (Table 2-1); it is estimated that over 50 percent of the variations occur in tRNA genes (Florentz et al., 2003). Importantly, many of those are known to affect a modified position directly, such as in variants in tRNALeu and tRNALys in human mitochondria, where it is not the variant per se but the defect in taurine modification of those tRNAs that is at the root of mitochondrial encephalomyopathies such as MELAS and MERFF1 (Suzuki et al., 2002) (see Box 1-2 in Chapter 1). To date, in addition to the aforementioned mitochondrial malfunctions, more than 50 different diseases ranging from cancers to neurological disorders have been associated with defects in tRNA modification (Jonkhout et al., 2017).

___________________

1 MELAS stands for mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes; MERFF stands for myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers.

TABLE 2-1 Human Diseases Caused by Aberrant tRNA Modifications

| Category | Disease | Gene | RNA modification | tRNA species | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial disease | MELAS | mt-tRNALeu(UUR) gene | τm5U | mt-tRNA | Suzuki, Nagao, and Suzuki, 2011a,b |

| MERRF | mt-tRNALys gene | τm5s2U | mt-tRNA | Suzuki, Nagao, and Suzuki, 2011a,b | |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and lactic acidosis | MTO1 | τm5U | mt-tRNA | Baruffini et al., 2013; Ghezzi et al., 2012 | |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and lactic acidosis and encephalopathy | GTPBP3 | τm5U | mt-tRNA | Kopajtich et al., 2014 | |

| RILF | MTU1 | τm5s2U | mt-tRNA | Wu et al., 2016; Zeharia et al., 2009 | |

| Combined mitochondrial respiratory chain complex deficiency, early-onset mitochondrial encephalomyopathy and seizures | NSUN3 | f5C | mt-tRNA | Paramasivam et al., 2020; Van Haute et al., 2016 | |

| MLASA | PUS1 | Ψ | cyto-tRNA, mt-tRNA | Mangum et al., 2016; Patton et al., 2005 | |

| Encephalopathy and myoclonic epilepsy with multiple OXPHOS deficiencies | TRIT1 | i6A | cyto-tRNA, mt-tRNA | Yarham et al., 2014 | |

| Multiple mitochondrial respiratory chain complex deficiencies | TRMT5 | m1G | cyto-tRNA, mt-tRNA | Powell et al., 2015 |

| Category | Disease | Gene | RNA modification | tRNA species | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological disorder | Familial dysautonomia | ELP1 | mcm5U and derivatives | cyto-tRNA | Anderson et al., 2001; Karlsborn et al., 2014; Yoshida et al., 2015 |

| Intellectual disability | ELP2 | mcm5U and derivatives | cyto-tRNA | Cohen et al., 2015 | |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | ELP3 | mcm5U and derivatives | cyto-tRNA | Simpson et al., 2008 | |

| Galloway–Mowat syndrome | KEOPS complex genes (OSGEP, TP53RK, TPRKB, LAGE3) | t6A | cyto-tRNA | Braun et al., 2017; Edvardson et al., 2017 | |

| Intellectual disability | TRMT1 | m2,2G | cyto-tRNA, mt-tRNA | Davarniya et al., 2015 | |

| Intellectual disability | FTSJ1 | 2′-O-methyl-ation | cyto-tRNA | Freude et al., 2004 | |

| Intellectual disability, DREAM-PL | CTU2 | mcm5s2U | cyto-tRNA | Shaheen et al., 2016 | |

| Intellectual disability, strabismus, microcephaly, growth delay | ADAT3 | I | cyto-tRNA | Alazami et al., 2013 | |

| Developmental delay, epileptic encephalopathy | DALRD3 | m3C | cyto-tRNA | Lentini et al., 2020 | |

| Diabetes, microcephaly and intellectual disability | TRMT10A | m1A, m1G | mt-tRNA | Igoillo-Esteve et al., 2013 | |

| Intellectual disability, HSD10 disease | SDR5C1 | m1A, m1G | mt-tRNA | Vilardo and Rossmanith, 2015 | |

| Severe neurodevelopmental defects | PUS3 | Ψ | cyto-tRNA, mt-tRNA | Chen and Patton, 2000; Lecointe et al., 1998; Shaheen et al., 2016 | |

| Intellectual disability, microcephaly, short stature, and aggressive behavior | PUS7 | Ψ | cyto-tRNA | de Brouwer et al., 2018 | |

| Galloway–Mowat syndrome, microcephaly | YRDC, KEOPS complex genes | t6A | cyto-tRNA | Arrondel et al., 2019; Braun et al., 2017 |

| Category | Disease | Gene | RNA modification | tRNA species | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Intellectual disability; skin, breast and colorectal cancer | NSUN2 | m5C | cyto-tRNA, mt-tRNA | Abbasi-Moheb et al., 2012 |

| Microcephaly, dwarfism, cancer | METTL1, WDR4 | m7G | cyto-tRNA | Lin et al., 2018b; Shaheen et al., 2015 | |

| Colon cancer, breast cancer | TYW2 (also known as TRMT12) | yW | cyto-tRNA | Rodriguez et al., 2007, 2012; Rosselló-Tortella et al., 2020 | |

| Bladder cancer, intellectual disability | ALKBH8 | mchm5U and derivatives | cyto-tRNA | Monies et al., 2019; Shimada et al., 2009) | |

| Breast cancer | TRMT2A | m5U | cyto-tRNA | Hicks et al., 2010 | |

| Colorectal cancer | NAT10 | ac4C | 18S rRNA, cyto-tRNA | Ito et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014 | |

| Diabetes | Type 2 diabetes | CDKAL1 | ms2t6A | cyto-tRNA | Steinthorsdottir et al., 2007; Wei et al., 2011 |

NOTE: Abbreviations for diseases and RNA modifications are defined in the Front Matter.

SOURCE: Suzuki, 2021. Published and licensed by Springer Nature.

As mentioned above, it has become apparent recently that even fragments of tRNAs can have important functions in health and disease, with several descriptions highlighting their role in regulating cell function (Muthukumar et al., 2024). However, this is a relatively new field, and further research is needed to delineate what is really at play. Along the same lines, ribosomal RNAs and their modifications remain understudied (Sloan et al., 2017). Given the many connections of tRNA modifications to health and disease, it is not surprising that as the field begins to learn about modification of other cellular RNAs, additional disease connections are emerging. For example, sporadic reports of modifications connected to disease have been discovered in noncoding RNAs other than tRNAs, including the classic case of Ψ defects in telomerase RNA, a driver of dyskeratosis congenita.

Unexpectedly, recent studies have revealed diverse chemical modifications in mRNA (Boccaletto et al., 2022), and because of the excitement in this area, the remaining sections of this chapter highlight mostly mRNA modifications. The diversity of factors identified in studies of mRNA modifications has led to new nomenclature for different types of modifications. Proteins that modify RNA chemically are collectively referred to as writers, and, as mentioned, proteins that remove modifications from RNA are known as erasers. A third category of proteins, readers, includes RNA-binding proteins that recognize and bind to specific modified nucleotides (Flamand, Tegowski, and Meyer, 2023). Depending on the type of RNA and its modifications, readers can alter the structure, function, translation, or stability of a modified RNA.

While certain modifications are unique to tRNA, others are widespread. For example, RNA methylation is one of the most abundant modifications and occurs in all types of RNA across all kingdoms of life (Stojković and Fujimori, 2017). Methyl groups are typically added to the four canonical RNA bases, but they can also be added to the ribose sugars, as well as noncanonical

bases—Ψ or inosine, for example (see Figure 1-4 in Chapter 1). Research is revealing additional intersections of the enzymes and pathways used for RNA modifications. For example, the fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) is the first RNA demethylase discovered; FTO is now known to act on mRNA as well as small nuclear RNA and tRNA (Wei et al., 2018). In addition, YTHDF2 and YTHDF3, two members of the major family of cytoplasmic m6A reader proteins, can regulate methylated circular RNAs in addition to their roles in regulating m6A-modified mRNA (Chen et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2017). To account for ongoing discoveries in this regard, in subsequent sections observations are often noted to relate to RNA in general, rather than a specific type of RNA.

As emphasized by the pioneering research on tRNA, in every type of RNA where modifications have been found, they have been linked to important aspects of biology and organismal function, acting as an additional layer of gene expression control (Roundtree et al., 2017). In many cases, the technologies needed to identify and study specific modifications have been developed only recently; thus, researchers have only begun to understand the many different functional roles of RNA modifications and the consequences of their dysregulation.

RNA MODIFICATIONS IN BIOLOGY

Even with today’s incomplete knowledge, it is clear that diverse biological processes are influenced by RNA modifications (Roundtree et al., 2017; Sloan et al., 2017; Suzuki, 2021). RNA structure can be modified by, for example, altering the number of hydrogen bonds in the base pairs that form the structure (see Figure 1-3 in Chapter 1). Modifications can also shift the binding affinities of specific RNA–protein and RNA–RNA interactions. Through alteration of the properties of these macromolecular interactions, modifications can impact RNA splicing, RNA stability, and protein translation (Roundtree et al., 2017; Sloan et al. 2017; Suzuki, 2021). This section discusses the role of RNA modifications in cell biology, physiology, immunology, and microbiology.

Cell Biology and Physiology

RNA modifications have been shown to modulate chromatin accessibility, transcription, RNA splicing (see Figure 1-1B in Chapter 1), RNA stability and degradation, 3’-end processing, mRNA export, mRNA localization, and mRNA translation (Burgess and Storkebaum, 2023; Flamand, Tegowski, and Meyer, 2023; Gilbert and Nachtergaele, 2023; Wei and He, 2021). The presence of RNA modifications can affect recognition of the RNA by a reader that binds directly to the region containing the modification; modifications can also have indirect effects when binding alters the global RNA structure. The existence of erasers in addition to writers for mRNA modifications suggests that, like tRNA modifications, mRNA modifications may be regulated dynamically in response to changing cellular conditions (Flamand, Tegowski, and Meyer, 2023; Shi, Wei, and He, 2019). For example, shifts in environmental conditions, responses to cellular stress, and alterations of signaling pathways can change the profile of RNA modifications, including Nm, 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG), m6A, 5-methylcytosine (m5C), and Ψ (Galvanin et al., 2020; Hahm et al., 2022; Li et al., 2015).

Because RNA modifications can change local and global RNA structures by altering the local charge distribution and affecting the strength of noncovalent forces, modifications can influence interactions between RNAs and proteins (Roundtree et al., 2017). By altering RNA–protein interactions, RNA modifications can also affect RNA stability (its susceptibility to degradation), the amount of protein the ribosome produces, and the ability of the RNA to catalyze a reaction (Roundtree et al., 2017). For example, in mammals, five m6A binding proteins contain a specific m6A recognition element, called a YTH domain. These readers bind m6A-containing RNAs in cells (Flamand, Tegowski, and Meyer, 2023; Shi, Wei, and He, 2019).

In addition to the canonical YTH reader proteins, studies have identified other RNA-binding proteins whose affinity for RNA is impacted by the presence of m6A (Dominissini et al., 2012; Edupuganti et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2018). Thus, m6A is recognized by its own specific set of YTH reader proteins as well as RNA-binding proteins that have other RNA-binding motifs, which contributes to the wide range of effects that m6A has on cellular RNAs. Importantly, both the YTH domain-containing proteins and other m6A-associated RNA-binding proteins have been linked to human disease, further indicating the importance of understanding how m6A impacts RNA-protein interactions in cells (Yanas and Liu, 2019). An additional impact of m6A is through the so-called m6A-switch mechanism, in which the presence of m6A destabilizes RNA secondary structure. This phenomenon has been reported at thousands of sites in the transcriptome, leading to widespread effects on pre-mRNA splicing (Liu et al., 2015). m6A can also stabilize mRNA secondary structure, depending on the surrounding sequence. Along with its importance for protein recognition, secondary structure influences many biological processes, including pre-mRNA splicing (Lewis, Pan, and Kalsotra, 2017).

As epitranscriptomic research has progressed, it is increasingly clear that basic RNA regulatory pathways and RNA chemical modifications are highly interrelated. For example, the exon junction complex, which is deposited during splicing and is important for the regulation of critical RNA surveillance pathways, is also a major factor in shaping m6A methylation in cellular mRNAs (Uzonyi et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2022). RNA modifications have also been shown to act as recruiting factors for the protein production machinery (e.g., ribosomes), leading to a boost in translation of cellular mRNAs (Meyer et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). Given their impact on transcription, posttranscriptional processing, and translation, it is not surprising that RNA modifications play roles in a wide variety of physiological processes, such as circadian rhythms; stem cell proliferation and differentiation; metabolic regulation; intra- and extracellular signaling; immune regulation; and proper development of organs, tissues, and cellular networks (Gilbert and Nachtergaele, 2023; Shi et al., 2020). The function of RNA modifications in these diverse processes is often cell-type and tissue dependent; thus, understanding which RNAs are modified under certain conditions and cell types will be critical for determining how RNA modifications impact the gene expression programs that underlie complex physiological processes.

Immunology and Microbiology

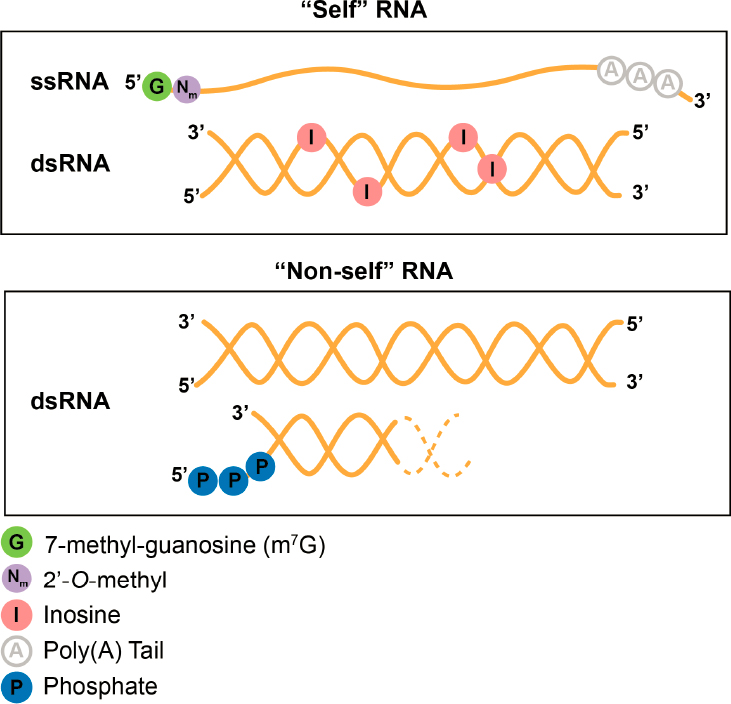

RNA modifications play important roles in innate immunity and the ability of cells to distinguish their own (“self”) RNAs from foreign (“nonself”) RNAs, such as viral or other pathogenic RNAs (Figure 2-1) (Chen and Hur, 2022). The N7-methylguanosine (m7G) cap and Nm are prevalent features at the 5’ end of cellular RNAs but are absent in many foreign RNAs (Leung and Amarasinghe, 2016). These foreign RNAs instead contain a di- or triphosphate at their 5’ end, which in mammals is recognized by innate immune receptor proteins, triggering an immune response. Importantly, m7G and 2’-O-methyl modifications found on self RNAs preclude interactions with innate immune receptor proteins, thus preventing an aberrant immune response (Garg et al., 2023; Leung and Amarasinghe, 2016).

Adenosine to inosine (A-to-I) editing of long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) sequences, which occurs naturally in the human transcriptome, enables cells to distinguish harmless, endogenous dsRNAs from viral dsRNAs (Quin et al., 2021). Long stretches of dsRNA are sensed by innate immune receptors, triggering an antiviral response (Chen and Hur, 2022; Tassinari, Cerboni, and Soriani, 2022). A-to-I editing of these dsRNAs in cellular transcripts prevents innate immune sensors from recognizing them, potentially by destabilizing the RNA duplex structure. Thus, A-to-I editing allows cells to distinguish host dsRNAs from viral dsRNAs. When A-to-I editing goes awry, endogenous, self dsRNA is perceived as viral dsRNA by cells, and type I interferons (a form of

NOTES: RNA is represented by an orange line or double helix. (Top) Modifications that are part of the 5’ cap of RNAs, such as m7G and the adjacent nucleotide containing a 2’-O-methylation are common features of endogenous single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) that are often lacking in viral RNAs and thus can be using by living cells to distinguish self from nonself RNA. Endogenous transcripts sometimes contain double-stranded (dsRNA) regions that look like viral dsRNA—but the inosine, created by the adenosine deaminase family of enzymes, keeps these self dsRNAs from triggering an aberrant immune response. (Bottom) Long dsRNA without inosines and short dsRNA with a 5’ triphosphate are made by viruses and can be recognized as foreign by innate immune receptors to trigger an immune response. Dotted lines indicate that triphosphorylated dsRNA can occur between two separate RNA strands or strands connected by a loop.

antiviral cytokines) are aberrantly expressed, resulting in severe diseases such as Aicardi–Goutières syndrome.

Some viruses have evolved mechanisms to mimic endogenous RNAs to avoid triggering a host innate immune response (Leung and Amarasinghe, 2016). For example, SARS-CoV-2 mimics both the 5’ cap structure and the 3’ polyadenylated tail found in mammalian cells (Liu et al., 2021a). SARS-CoV-2 also contains m6A modifications that are deposited by the host methyltransferase, METTL3; depletion of METTL3 reduces viral m6A and SARS-CoV-2 viral load (Li et al., 2021). Additionally, decreased viral m6A leads to increased host inflammatory gene expression and stimulation of the downstream innate immune signaling pathway. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 viral replication is influenced by METTL3, and SARS-CoV-2 infection can alter METTL3 expression

and localization (Zhang et al., 2021). Studies of other viruses have shown that viral infection can also trigger changes in the modification of host RNAs, which may impact gene expression programs in cells, thus influencing antiviral responses (McFadden and Horner, 2021). Methods that facilitate sequencing of RNA modifications will enable a better understanding of their prevalence and function in both viral and host RNAs. RNA modifications are a critical component of innate immunity and viral RNA regulation. The ability to map these diverse modifications and measure their abundance will substantially impact the development of treatments and preventive measures such as vaccines.

Antibiotics such as aminoglycosides, macrolides, and tetracyclines, which are used to fight bacterial infections, work by binding to the bacterial ribosome (Lin et al., 2018a). Binding typically inhibits the key function of the ribosome, protein synthesis, and thus prevents cell growth and division, resulting in bacterial cell death. One way that bacteria can resist effects of these antibiotics is by altering the modifications in their rRNA (Tsai et al., 2022). For example, when bacteria express a variant of the Cfr methyltransferase with increased enzyme activity, there is an increase in C-8 methylation of an adenosine in their rRNA in the large ribosomal subunit. The new methylation pattern blocks antibiotic binding to the bacterial ribosome, rendering the antibiotic ineffective (Tsai et al., 2022).

RNA MODIFICATIONS IN DISEASE

Although some RNA modifications are reversible, the degree to which the process is dynamic can be difficult to assess because of limitations in current technology, namely in the ability to measure modification stoichiometry in specific RNAs (Flamand, Tegowski, and Meyer, 2023; Murakami and Jaffrey, 2022; Roundtree et al., 2017). What is known is that the activity of proteins that add and remove RNA modifications is regulated by pathways that are influenced by both cellular and extracellular conditions. Dysregulation of these writers and erasers, and of the readers that recognize RNA modifications, is linked to a wide variety of human diseases and disorders (Delaunay, Helm, and Frye, 2023; Flamand, Tegowski, and Meyer, 2023). In addition, genetic variants that do not alter the protein coding sequence may potentially confer increased disease susceptibility by preventing modification of the encoded mRNA (Song et al., 2022). This area continues to be understudied, partly because of the lack of methods for site-specific modification detection. Finally, cellular stress and exposure to toxins have been linked to alterations in both RNA modifications and RNA-modifying proteins. This section presents some examples focusing on the linkage between disease (e.g., cancer) and dysregulation of RNA-modifying proteins, and on the role of RNA modifications following acute damage to nucleic acids in the cell or exposure to chemical toxins.

Dysregulation of Writers, Readers, and Erasers

Dysregulation of the genes encoding writers, readers, and erasers of RNA modifications has been linked to neurodevelopmental disorders, neurodegenerative disease, heart disease, cancer, and diabetes (Flamand, Tegowski, and Meyer, 2023; Stojković and Fujimori, 2017; Suzuki, 2021; Yanas and Liu, 2019), representing a significant health burden; Table 2-1 emphasizes the importance of tRNA modifications to these diseases. This section examines two categories of RNA-modifying machinery: (1) methylation writers, readers, and erasers, and (2) pseudouridine synthases. Dysregulation of these proteins has been implicated as a driver of disease (Du et al., 2019; Keszthelyi and Tory, 2023).

Methylation Machinery and Cancer

METTL3 catalyzes the addition of m6A into RNA molecules, with the help of METTL14 and additional cofactors (Flamand, Tegowski, and Meyer, 2023; Liu et al., 2014; Visvanathan et al., 2018; Zaccara, Ries, and Jaffrey, 2019). Several reader proteins have been identified that can bind specifically to m6A-modified RNAs. As previously mentioned, proteins containing a YTH domain are one example of direct m6A reader proteins. These proteins have been linked collectively to several aspects of RNA regulation, including splicing and noncoding RNA function (YTHDC1) (Chen et al., 2021; Liu, et al., 2020a; Xiao et al., 2016), translation (YTHDF1, YTHDF3) (Shi et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2015), and RNA decay (YTHDF1, 2) (Wang et al., 2014; Zaccara and Jaffrey, 2020). Other RNA-binding proteins outside the YTH domain have also been shown to preferentially bind m6A-modified RNAs; these include the IGF2BP proteins, which can enhance the translational efficiency and increase the stability of mRNAs with m6A (Huang et al., 2018). Finally, the m6A modification can be removed by FTO or ALKBH5 eraser proteins (Jia et al., 2011; Zheng et al., 2013).

Genetic variants in the methyltransferases METTL3 and METTL14 have been linked to the predisposition and progression of several tumors, including glioblastoma, acute myeloid leukemia, and cancers of liver, colon, lung, and breast tissue (Deng et al., 2018; Visvanathan et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2020). The mechanism of disease for these tumors has proven to be variable. One study found that knockdown of METTL3 enhanced glioblastoma stem cell (GSC) self-renewal and growth and promotes tumorigenesis in mice (Cui et al., 2017). Conversely, a subsequent study found that silencing METTL3 inhibited GSC growth and suppressed tumor growth in mice (Visvanathan et al., 2018). One potential explanation for this discrepancy is altered expression of reader proteins or target RNAs during differentiation of cells within the GSC pool. In the first study, increased expression of oncogenes ADAM19, EPHA3, and KLF4 correlated with tumor progression (Cui et al., 2017), while in the second study, decreased expression of SOX2 correlated with suppressed tumor growth (Visvanathan et al., 2018). Further research to delineate the dynamics of mRNA-specific m6A modifications, along with the interplay of reader proteins, has the potential to identify therapeutic targets for the treatment of glioblastoma and several other cancer types.

In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), METTL3 expression is significantly higher than in other cancer types and in primary hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, which correlates with significantly higher abundance of m6A (Weng, Huang, and Chen, 2019; Xu and Ge, 2022). Importantly, knockdown of METTL3 in AML cells blocks cell growth, promotes differentiation, and leads to apoptosis. This indicates that drugs that reduce the activity of METTL3 may be promising therapies for AML. Surprisingly, FTO, a key eraser for m6A modifications (Jia et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2014), is also overexpressed in some subtypes of AML (Li et al., 2017). Experiments testing the effect of overexpression of FTO in cell culture demonstrated increased growth, proliferation, and viability, while decreasing the global mRNA m6A levels.

There is no straightforward link between m6A abundance and AML progression or treatment, which is also true for glioblastoma. In some conditions and tumor subtypes, increased abundance of m6A may result in increased proliferation and tumorigenesis, and in others it may block cell growth and promote differentiation. While inhibitors of METTL3 or FTO may prove to be promising treatments for AML, it will be essential to identify which patients may benefit from raising m6A levels and which will benefit from lowering m6A levels. Treating some patients with METTL3 inhibitors may effectively treat their cancer, while in others it could accelerate progression and reduce survival. Ultimately, tools to better quantify m6A in tumor tissue will be essential for improving diagnosis and developing more effective treatments.

Pseudouridine Synthases

The pseudouridine synthases (PUSs) are writers that isomerize uridine to pseudouridine in tRNA, rRNA, small nuclear RNA, mRNA, and other classes of RNA. A majority of these pseudouridine writers have been associated with a wide range of human diseases (Keszthelyi and Tory, 2023). Loss of function variants, truncations, or disruption of the catalytic domain of PUS3 and PUS7 cause inherited neurodevelopmental disorders that present with intellectual disabilities, microcephaly, short stature, and aggressive behavior (Darvish et al., 2019; de Brouwer et al., 2018; Han et al., 2022; Keszthelyi and Tory, 2023; Naseer et al., 2020; Shaheen et al., 2019). The shared neurodevelopmental phenotypes associated with variants in these and other tRNA-modifying enzymes suggest that defective pseudouridylation of tRNAs could contribute to the disease etiology.

Variants in PUS1 are responsible for a mitochondrial encephalopathy called MLASA (mitochondrial myopathy, lactic acidosis, sideroblastic anemia; Table 2-1) (Cao et al., 2016; Fernandez-Vizarra et al., 2007; Kasapkara et al., 2017; Oncul et al., 2021; Tesarova et al., 2019). An isoform of PUS1 localizes to mitochondria where PUS1 modifies mitochondrially encoded tRNAs and mRNAs (Dai et al., 2023; Suzuki et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2023). Cells from MLASA patients display global mitochondrial translation defects consistent with the mitochondrial myopathy phenotypes (Fernandez-Vizarra et al., 2007).

Dyskeratosis congenita, an X-linked disorder, is caused by variants in the small nucleolar RNA–guided pseudouridine synthase DKC1, which installs pseudouridines in rRNAs and small nuclear RNAs (AlSabbagh, 2020). Defective rRNA pseudouridylation is observed in samples from dyskeratosis congenita patients harboring variants in DKC1, suggesting that differences in pseudouridine levels could contribute to the diverse clinical presentation (Bellodi et al., 2013; Schwartz et al., 2014).

Beyond rare genetic disorders, high levels of pseudouridine synthase expression are observed in various cancers and are associated with worse outcomes (Cerneckis et al., 2022; Keszthelyi and Tory, 2023). Increased expression of PUS7 in glioblastoma cells leads to an increase in pseudouridylation of several tRNAs and mRNAs and impacts the translation of cancer regulators (Cui et al., 2021). PUS7 depletion inhibited glioblastoma tumorgenesis in mice; this was rescued by reintroducing wildtype PUS7, but not by a mutant lacking catalytic activity. These results suggest that pseudouridylation of RNA targeted by PUS7 is required for tumorigenesis (Cui et al., 2021). Tools for better interrogating and quantifying pseudouridine could help uncover new therapeutic targets.

Chemical and Abiotic Factors That Alter RNA Modifications

As with protein phosphorylation and DNA methylation, RNA modifications are responsive to changes in cellular and extracellular conditions. These alterations in RNA modification profiles in response to changes in the milieu add an additional, and often dynamic, layer of gene expression regulation. For instance, inducing cellular stress through heat shock, hypoxia, or nutrient deprivation has been shown to alter tRNA modifications (e.g., m5C) or mRNA modifications (e.g., m6A, Ψ), in turn leading to dynamic changes in gene expression (Dedon and Begley, 2014; Galvanin et al., 2020; Hahm et al., 2022; Huber et al., 2019; Meyer, 2019; Roundtree et al., 2017). Exposure to commonly used chemicals such as bisphenol A (BPA), pesticides such as atrazine and diazinon, metals, and carcinogens such as benzo(a)pyrene and dioxin have been associated with altered modification of cellular RNAs or changes in expression levels of writer, reader, and eraser proteins (Cayir, Byun, and Barrow, 2020).

There is also growing evidence that RNA modifications can influence the cellular response to environmental agents that initiate DNA damage. For instance, the m6A modification is rapidly induced in RNAs near sites of DNA damage after UV exposure. The increase in m6A helps recruit

proteins involved in DNA repair (Xiang et al., 2017). RNA–DNA hybrid molecules (R-loops) that form near sites of DNA damage have also been shown to acquire modifications, including m6A, m5C, and abasic sites, which can be important for maintaining genomic stability (Jimeno, Balestra, and Huertas, 2021; Liu et al., 2020b). Other modifications, including N1-methyladenosine, 7-methylguanosine (m7G), 5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-uridine, and A-to-I editing, have also been implicated in DNA repair in response to a variety of DNA-damaging agents (Jimeno, Balestra, and Huertas, 2021). For example, the induction of oxidative stress in cells, with its concomitant excess of reactive oxygen species, oxidizes guanine to 8-oxoG. This can lead to inappropriate 8-oxoG base-pairing with adenine, resulting in changes in RNA structure. When this occurs in mRNA or rRNA, protein translation is perturbed (Hahm et al., 2022).

RNA MODIFICATIONS FOR PREVENTING AND TREATING DISEASE

The recent success of modified RNAs in treating human diseases heralds the advent of RNA as an effective therapeutic agent. RNAs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are being used to prevent COVID-19 and treat diseases affecting infants, children, and elderly patients; diseases of the eyes, liver, muscles, and spinal cord; and rare diseases for which there had been no prior treatment (Table 2-2) (Winkle et al., 2021).

This section looks at several ways that modified RNAs are being used, tested, and targeted for treating and preventing human diseases. Fundamental research on RNA modifications is being translated into the clinic in lifesaving ways: mRNA vaccines protect against infectious diseases and tumors; small molecules regulate RNA-modifying proteins; and in situ methods repair defective mRNAs to restore proper protein synthesis. Modifications have been found to improve efficacy of antisense oligonucleotides; small interfering RNAs are being used to treat rare genetic diseases and metabolic disorders (Table 2-2); and RNA aptamers are being designed as sensors for potential use in clinical and forensic labs and to monitor environmental conditions. As discussed in Chapter 3, modifications of the guide RNAs used in the powerful gene-editing technique CRISPR9F2 also show promise (Rozners, 2022).

mRNA Vaccines for the Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19 and Cancer

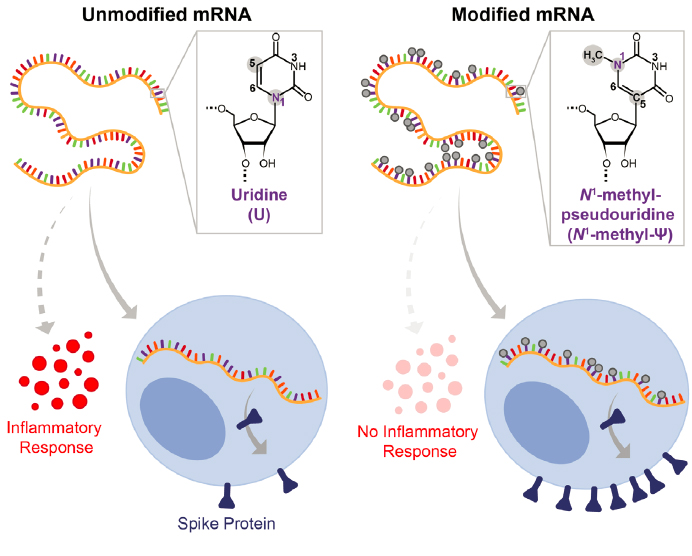

Research on RNA modifications has had a profound effect on the field of immunology; most notable is the development of mRNA vaccines to combat COVID-19 (Nobel Prize, 2023) (Box 2-1). Studies first published in 2005 showed that the naturally occurring mRNA modification pseudouridine (Ψ) can protect against foreign RNAs triggering an immune response in host cells (Karikó et al., 2005); later work showed that Ψ can also boost protein production from mRNA (Karikó et al., 2008). Nearly two decades later and amid the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers built on these core discoveries and developed mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 in which the mRNA is modified with N1-methyl-Ψ, enabling the mRNA to evade innate immune sensors and produce sufficient protein to stimulate an immune response and antibody production against the virus (Morais, Adachi, and Yu, 2021).

mRNA vaccines are being developed and tested for specific cancer antigens in melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, prostate cancer, acute myeloid leukemia, non–small cell lung cancer, glioblastoma, and colorectal cancer (Elkhalifa et al., 2022). The objective of these anticancer vaccines is to train the immune system to see and target novel cancer antigens or growth-associated factors that are expressed by malignant cells (Mei and Wang, 2023). Dozens of mRNA anticancer vaccines are

___________________

2 CRISPR stands for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. See https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/CRISPR (accessed January 29, 2024).

| Therapeutic (Brand name) | Type | Modification and delivery | Route of administration | Target organ | Disease | Target gene and pathway | FDA and/or EMA approval year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fomivirsen (Vitravene) | 21-mer ASO | 1st gen; PT | Intravitreal | Eye | Cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis in immunocompromised patients | CMV IE-2 mRNA | 1998 (FDA), 1999 (EMA)a |

| Mipomersen (Kynamro) | 20-mer ASO | 2nd gen; 2′-MOE gapmer | Subcutaneous | Liver | Homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia | Apolipoprotein B mRNA | 2012 (EMA), 2013 (FDA) |

| Nusinersen (Spinraza, ASO-10-27) | 18-mer ASO | 2nd gen; 2′-MOE | Intrathecal | Central nervous system | Spinal muscular atrophy | Survival of motor neuron 2 (SMN2) pre-mRNA splicing (exon 7 inclusion) | 2017 (EMA), 2016 (FDA) |

| Eteplirsen (Exondys 51) | 30-mer ASO | 3rd gen; 2′-MOE PMO | Intravenous | Muscle | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Dystrophin (DMD) pre-mRNA splicing (exon 51 skipping) | 2016 (FDA) |

| Inotersen (Tegsedi, AKCEA-TTR-LRx) | 20-mer ASO | 2nd gen; 2′-MOE; GalNAc-conjugated | Subcutaneous | Liver | Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis | Transthyretin (TTR) mRNA | 2018 (EMA), 2018 (FDA) |

| Patisiran (Onpattro) | 21-nucleotide (nt) ds-siRNA | 2nd gen; 2′-F/2′-O-Me; liposomal | Intravenous | Liver | Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis | Transthyretin (TTR) mRNA | 2018 (EMA), 2019 (FDA) |

| Golodirsen (Vyondys 53, SRP-4053) | 25-mer ASO | 3rd gen; 2′-MOE PMO | Intravenous | Muscle | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | DMD pre-mRNA splicing (exon 53 skipping) | 2019 (FDA) |

| Givosiran (Givlaari) | 21-nt ds-siRNA | 2nd gen; 2′-F/2′-O-Me; GalNAc-conjugated | Subcutaneous | Liver | Acute hepatic porphyria | Delta aminolevulinic acid synthase 1 (ALAS1) mRNA | 2020 (EMA), 2019 (FDA) |

| Therapeutic (Brand name) | Type | Modification and delivery | Route of administration | Target organ | Disease | Target gene and pathway | FDA and/or EMA approval year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viltolarsen (Viltepso, NS-065, NCNP-01) | 21-mer ASO | 3rd gen; 2′-MOE PMO | Intravenous | Muscle | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | DMD pre-mRNA splicing (exon 53 skipping) | 2020 (FDA) |

| Volanesorsen (Waylivra) | 20-mer ASO | 2nd gen; 2′-MOE gapmer | Subcutaneous | Liver | Familial chylomicronaemia syndrome | Apolipoprotein CIII (APOC3) mRNA | 2019 (EMA) |

| Inclisiran (Leqvio, ALN-PCSsc) | 22-nt ds-siRNA | 2nd gen; 2′-F/2′-O-Me; GalNAc-conjugated | Subcutaneous | Liver | Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, elevated cholesterol, homozygous/heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) mRNA | 2020 (EMA) |

| Lumasiran (Oxlumo, ALN-GO1) | 21-nt ds-siRNA | 2nd gen; 2′-F/2′-O-Me; GalNAc-conjugated | Subcutaneous | Liver | Primary hyperoxaluria type 1 | Hydroxyacid oxidase 1 (HAO1) mRNA | 2020 (EMA), 2020 (FDA) |

NOTE: Abbreviations are defined in the Front Matter.

a Marketing was stopped in 2002 after development of potent antiretroviral therapeutics.

SOURCE: Winkle et al., 2021. Published and licensed by Springer Nature.

currently in clinical trials. For example, in melanoma, an aggressive tumor that originates in melanocytes, several types of tumor antigens are presented by major histocompatibility complex class I proteins on the surface of melanoma cells (Davis, Shalin, and Tackett, 2019). A vaccine candidate, melanoma FixVac (BioNTech), which utilizes uridine-modified mRNAs encoding four melanoma tumor-associated antigens, is in Phase II trials (Sahin et al., 2020).

Therapies for Treatment of Diseases

Modification of Antisense RNA Oligonucleotides: Treatment for Rare genetic Diseases

Another recent therapeutic breakthrough is the use of short pieces of modified single-stranded RNA to treat rare but devastating genetic diseases for which no treatments have previously been available. These treatments use RNAs that are complementary to their mRNA targets and thus bind to the mRNA molecules. These so-called antisense RNA oligonucleotides (ASOs) interfere with gene expression, either during pre-mRNA splicing or by reducing mRNA levels (Crooke et al., 2018). The ASOs bear a diverse set of RNA modifications (Table 2-2), largely to maintain their stability.

Spinal muscular atrophy is a genetic disease of a recessive variant in the SMN1 gene, which usually presents in newborns, resulting in motor neuron loss and progressive muscle wasting. Untreated, it is the most common genetic cause of infant death (Tisdale and Pellizzoni, 2015). Variants in the SMN1 gene lead to decreased production of survival motor neuron (SMN) protein, which is critical for the health of motor neurons. A pioneering ASO, nusinersen (brand name Spinraza), works by modulating pre-mRNA splicing of the SMN2 mRNA, a close paralog of SMN1, so that expression of the SMN protein is restored (Figure 2-3) (Finkel et al., 2017; Hill and Meisler, 2021; Mercuri et al., 2018; Pechmann et al., 2023). Nusinersen consists of a uniformly modified 2’-O-(2-methoxyethyl) phosphorothioate antisense RNA oligonucleotide, 18 nucleotides in length. Both the sulfur-substituted phosphate backbone and the methoxyethyl modifications stabilize the ASO following injection into spinal fluid. The success of this novel RNA-based therapy has been so great that children with spinal muscular atrophy are now largely meeting their developmental milestones. ASOs are in development to treat several additional otherwise-untreatable genetic diseases, such as Batten’s disease (Kim et al., 2019), Dravet syndrome, and Scn8a encephalopathy (Hill and Meisler, 2021).

Modification of Small Interfering RNAs: Treatment for Rare Metabolic Diseases

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are small double-stranded RNA molecules with a sequence complementarity to target RNAs. When one of the siRNA strands binds to a target mRNA, the mRNA is degraded via the RNA-induced silencing complex pathway, thereby reducing protein levels caused by targeted mRNA depletion (Fire et al., 1998; Iwakawa and Tomari, 2022). Therapeutic siRNAs can be chemically modified to improve their stability and targeting efficacy. The first siRNA-based therapy, patisiran, was approved by FDA in 2018 for clinical use against hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (Adams et al., 2018; Hoy, 2018). Transthyretin amyloidosis results from autosomal dominant variants in the gene TTR that cause it to aggregate in multiple organ systems. Since the aggregates are deposited in the heart and nervous system, patients present with polyneuropathy and cardiomyopathy; survival times are, at most, 15 years (Urits et al., 2020). Patisiran is concentrated in the liver, where transthyretin is made and causes degradation of TTR (Urits et al., 2020). The siRNA is modified with eleven 2′-methoxy-modified sugar residues and four 2′-deoxythymidine residues to improve its stability and to avoid off-target effects (Bajan and Hutvagner, 2020).

BOX 2-1

The Critical Role of RNA Modifications in Vaccines Against COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic that came to the United States in March 2020 caused grave illness that resulted in excess mortality.a COVID-19 is caused by a coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, that uses RNA for its genome and is transmitted through airborne particles or in droplets. In 2022, COVID-19 had a high case–fatality ratio of 1–2 percentb (Iyanda et al., 2022), 10 times higher than that of influenza. It led to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation for widespread social and physical distancing as an attempt to keep contagion down. Until a vaccine became available, all aspects of life, from education and employment to everyday errands, were affected. Once they became widely available, vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 made it possible for many people to return to aspects of normal life. The most frequently used vaccines, produced in 2020, were based on decades of researchc and tested in the novel context of the COVID-19 vaccine with unprecedented rapidity by two companies, Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech (Jain et al., 2021). Timely development was made possible by Operation Warp Speed, a public–private partnership initiated by the U.S. government in response to the COVID-19 pandemic to enable development of diagnostics, therapies, and vaccines at an increased rate by funding a substantial number and variety of vaccine development efforts simultaneously.d Both Moderna’s and Pfizer-BioNTech’s vaccines used an mRNA that coded for the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Critically, in both vaccines the nucleotide uridine was modified to N1-methyl-pseudouridine (Ψ) (Figure 2-2) (Morais, Adachi, and Yu, 2021).

The N1-methyl-Ψ modification was critical to the vaccines’ success (Mei and Wang, 2023; Morais, Adachi, and Yu, 2021; Nance and Meier, 2021; Pardi et al., 2017). This modification permitted the mRNA to evade innate immune sensors, such as the toll-like receptor system, enabling the mRNA in the vaccine to be translated into spike protein and stimulate an immune response (Figure 2-2). The importance of the RNA modification in the vaccine is supported by a comparison of the clinical trials of mRNA spike protein vaccines with and without modified uridines (Morais, Adachi, and Yu, 2021). The vaccine without N1-methyl-Ψ (CureVac) had only 48 percent efficacy at blocking COVID-19 symptoms, while the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines had efficacies over 90 percent (Morais, Adachi, and Yu, 2021). Building on the findings of fundamental research on mRNA modifications that long predates the pandemic (Karikó et al., 2005; Pardi et al., 2017), the modified uridines introduced into the mRNA have proven to be critical for the vaccines’ success in protecting against SARS-CoV-2 infection and serious disease.

The United States has embraced these new vaccine technologies to protect against SARS-CoV-2 infection. As of May 2023, 81.4 percent (270,227,181) of the people of the United States had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Ninety-seven percent of the administered vaccines were mRNA vaccines with modified nucleotides from Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech.e Several studies have analyzed the health and economic impact of the vaccines. For example, a study by the National Bureau of Economic Research estimated the economic value of excess mortality reductions in the first 8 months of vaccination rollout in the United States to be $3.09 trillion (Agrawal, Sood, and Whaley, 2023). Similarly, another study found that the United States saved an estimated $10.6 billion in averted outpatient costs and about $80 billion in cost savings through avoidance of productivity loss (Yang et al., 2023).

__________________

SOURCE: Adapted from Nobel Prize, 2023. Copyright The Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine. Illustrator: Mattias Karlén.

a Because testing was limited at the beginning of the pandemic, actual counts likely do not reflect actual mortality. See https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2022/07/12/excess-mortality-during-the-pandemic-the-role-of-health-insurance/.

b To see the change in the case fatality ratio over time and by country, see https://ourworldindata.org/mortality-risk-covid (accessed October 27, 2023).

c See https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2021/the-long-history-of-mrna-vaccines (accessed January 4, 2023).

d See https://web.archive.org/web/20201216233803/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/05/15/trump-administration-announces-framework-and-leadership-for-operation-warp-speed.html (accessed January 5, 2024).

e Data as of May 10, 2023, 6 AM ET. See https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations_vacc-people-booster-percent-pop5 (accessed October 27, 2023).

SOURCE: Hill and Meisler, 2021. Copyright © 2021 Karger Publishers, Basel, Switzerland.

Since FDA approval of patisiran, three other siRNA-based therapies have been approved for the treatment of rare metabolic diseases. Givosiran is designed to treat acute hepatic porphyria (Majeed et al., 2022); lumasiran treats primary hyperoxaluria type I (Garrelfs et al., 2021); and inclisiran for heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or severe atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease via targeting of the LDL-C protein (Kim and Choi, 2022). The therapeutic mechanism in each case is to decrease levels of the problem protein. Numerous siRNA-based therapies are in development for other metabolic and nonmetabolic diseases, such as hemophilia A and B, glaucoma, and dry eye disease. Considering the protocols that have been successful so far, it seems very likely that these siRNAs will contain RNA modifications (Padda, Mahtani, and Parmar, 2023).

Modified RNA Aptamers as Therapeutics and Biosensors

RNA aptamers are short RNAs; researchers screen for them in the laboratory to select those that bind to a specific target with high affinity (Nimjee et al., 2017). They are often modified for increased stability at the 2’ hydroxyl of the ribose and for colorimetric or fluorometric detection. So far, only two aptamers are FDA approved (both for eye disease), but many other modified RNA aptamers are currently in preclinical development or in clinical trials for cardiovascular disease, inflammation, and cancer (Liu et al., 2021b; Ni et al., 2021).

Wet macular degeneration is a vascular disease of the eye that leads to blindness in millions of people worldwide. Its disease pathogenesis can be traced to increased production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), resulting in proliferation of blood vessels in the retina (Vinores, 2006). In 2004, a pegylated fluorine-substituted single-stranded 2-nucleotide RNA aptamer (pegaptanib, brand name Macugen) that inhibits VEGF became the first FDA-approved aptamer drug (Vinores, 2006). It was widely used for the treatment of wet macular degeneration until monoclonal antibodies against VEGF became the preferred therapeutic (Kovach et al., 2012). Another heavily modified RNA aptamer, avacincaptad pegol (Izervay), was approved by FDA in 2023 to treat the geographic atrophy sequela of wet macular degeneration (Verdin, 2023). Its mechanism of action is to inhibit the C5 protein in the complement pathway (Jaffe et al., 2021).

Aptamers are also being developed as biosensors that can detect toxic chemicals (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine) in human urine and serum, food allergens, and contaminants (e.g., aflatoxins) (Kadam and Hong, 2022), and microorganisms and heavy metals in soil and water samples (McConnell, Nguyen, and Li, 2020). Additionally, aptamers are being developed into sensors that can help determine air quality (McConnell, Nguyen, and Li, 2020). Natural aptamers, such as riboswitches, have also been used to measure fluoride to determine water quality (Thavarajah et al., 2020).

Targeting an RNA-Modifying Enzyme: Novel Anticancer Therapy

As previously discussed, METTL3, the primary m6A methyltransferase protein in mammals, is upregulated in many cancers, where it can act as an oncogene to drive cancer progression (Zheng et al., 2021). Because of this, METTL3 has emerged as a promising candidate target for new anticancer therapies. Depletion of METTL3 in mice with acute myeloid leukemia increased survival and delayed leukemic progression (Barbieri et al., 2017; Vu et al., 2017). STM2457, a small-molecule inhibitor of METTL3, has been shown to successfully treat acute myeloid leukemia in mice with limited toxicity in hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells at the antileukemic dose (Yankova et al., 2021). In 2022, STORM Therapeutics began a Phase I trial of an orally administered small molecule, STC-15, that inhibits METTL3 activity.3 This is the first instance of an anticancer drug designed to inhibit an RNA methylation enzyme.

RNA MODIFICATIONS BEYOND HUMAN HEALTH

As this chapter has described, basic research on RNA modifications is proving translatable into lifesaving applications in medicine; notably the COVID-19 vaccines and cancer immunotherapy (Barbieri and Kouzarides, 2020; Delaunay, Helm, and Frye, 2023; Mei and Wang, 2023). But applications of RNA modifications research in other sectors of society also has great potential for improving lives. This section discusses the use of controlled RNA modification profiles in plants to improve crops, which has the potential to strengthen global food security and enhancing plant resilience. This section also introduces the roles that RNA modifications can play in synthetic biology, a field of research with enormous potential in drug design and delivery, immunotherapy, and nanotechnology.

Global Food Security

The National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), a branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, has declared that global food security is a critical issue, stating that every nation should

___________________

3 See https://www.stormtherapeutics.com/media/news/storm-therapeutics-doses-first-patient-with-oral-mettl3-targeting-drug-candidate-in-a-solid-tumor-phase-1-study/ (accessed September 19, 2023).

be able to feed its people adequate calories of nutritious food.4 NIFA argues that food security reduces poverty and leads to improved health, trade, stability, and increased economic growth. NIFA’s efforts toward enhancing food security worldwide include developing ways to increase production and yield.5 One approach has been to alter the RNA modifications profile in agricultural crops (Yu et al., 2021).

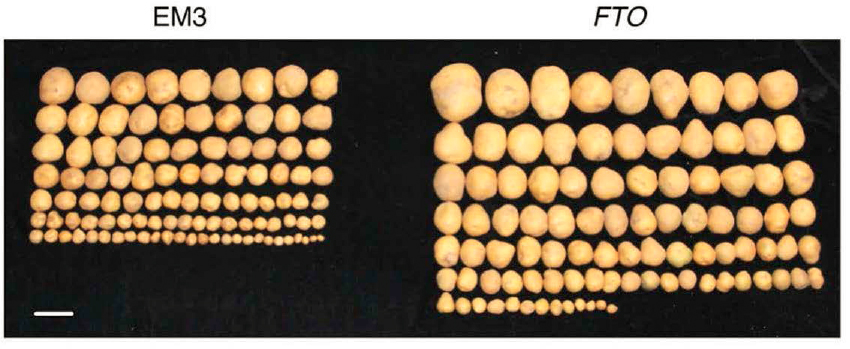

Like other complex organisms, plant crops such as rice and potato have m6A-modified nucleotides in their RNA. In humans, the demethylase FTO removes the methyl group from m6A. Although plants lack an FTO homolog, in one study, human FTO expressed as a transgene in rice and potato plants resulted in a 50 percent increase in the yield and biomass of both crops (Yu et al., 2021) (Figure 2-4). FTO transgene expression also stimulated root growth in both crops and tiller bud formation in rice, improved photosynthetic efficiency, and enhanced drought resistance. Experiments have shown that FTO acts in these plants by demethylating m6A in both mRNA and repeat RNA, leading to increased activation of overall transcription, thereby driving growth (Lowe, 2021;Yu et al., 2021). Exciting prospects include the transgenic expression of human FTO in other crops, such as wheat, soybeans, and cassava, to increase food security worldwide.

Plants possess readers, writers, and erasers that can be distinct from those in vertebrates (Yu, Sharma, and Gregory, 2021). Results so far show that m6A and m5C modifications are necessary for plant growth and development (David et al., 2017; Parker et al., 2020; Yu, Sharma, and Gregory, 2021). For example, disruption of writers and erasers of m6A in Arabidopsis shows that temporal and spatial signals for proper plant development require dynamic control of m6A (Reichel, Köster, and Staiger, 2019). RNA modifications in fungal plant pathogens, such as the rice blast fungus, Magnaportae oryzae, may be targets for agrochemicals. It has been shown deleting the m6A writer in M. oryzae decreases its virulence (Shi, Wei, and He, 2019). Defining and manipulating RNA modifications in plants in the future will likely be a critical step toward increased global food security.

NOTE: Photos of potato tubers (left) compared with human FTO transgenic potatoes (right).

SOURCE: Yu et al., 2021. Published and licensed by Springer Nature.

___________________

4 See the NIFA homepage, https://www.nifa.usda.gov/ (accessed September 19, 2023).

5 See NIFA’s page on Global Food Security, https://www.nifa.usda.gov/topics/global-food-security (accessed September 19, 2023).

Synthetic Biology

RNA modifications may also play a role in the blossoming field of synthetic biology, which involves “redesigning organisms so that they produce a substance, such as a medicine or fuel, or gain a new ability, such as sensing something in the environment” (NHGRI, n.d., para. 1). Among the promises of synthetic biology is the generation of proteins/enzymes that contain nonnatural amino acids, which may impart new functionalities (de la Torre and Chin, 2021).

Despite much progress, improving the efficiency and robustness of redesigned organisms is plagued with significant barriers in the production of a desired enzyme or protein with unusual properties. An incomplete understanding of how RNA modifications help or hinder the incorporation of nonnatural amino acid into designer enzymes and proteins may lead in part to poor yields (McFeely et al., 2022). Thus, integrating knowledge of modifications in such systems may lead to scaled-up production of novel proteins. Indeed, it has been reported that changes to enzymes that modify tRNAs posttranscriptionally affect tRNA abundance and thereby likely affect the translation of heterologous proteins (Baldridge et al., 2018). Another barrier is the limited understanding of how to program RNA modifications at specific sites and specific times; this additional control point could tune gene expression and even enable genetic networks that would impact almost all synthetic biology applications. Synthetic biology applications that utilize precise control of RNA modifications are likely to impact basic and translational advances in sectors such as energy, industrial and environmental biotechnology, food and agriculture, and medicine.6 Likewise, knowledge of modifications may help advance the new field of RNA nanotechnology, where RNA is used as the scaffold to build new nanostructures for use in RNA vaccine and drug delivery, in immunotherapy as immune system stimulants, in computing, and in materials synthesis applications (Parsons et al., 2023; Poppleton et al., 2023).

MAJOR CHALLENGES AND SCIENTIFIC GAPS

Despite increased recognition of the importance of RNA modifications for cellular function and human health, numerous gaps remain in the understanding of the regulation and function of these modifications.

One major challenge has been the lack of universal methods and standard practices for sequencing and quantifying various modifications (discussed in Chapters 3 and 4). This has led to inconsistencies across datasets and discrepancies among conclusions reported in published studies. The epitranscriptomics research community has identified the need for unified methods and standard practices for RNA modification sequencing and quantification as a major hurdle that needs to be overcome (NASEM, 2023; NIEHS, 2022).

Several other critical gaps in knowledge can be addressed once improved technologies for studying RNA modifications are readily available. For example, a key unanswered question is whether multiple RNA modifications exist on the same RNA molecule and whether they compete or coordinate (e.g., crosstalk). Although it is fundamental to understanding the composition and function of RNA, very few studies have addressed this topic (Fleming et al., 2023). To answer this question, researchers need methods for sequencing individual RNA molecules from end to end while simultaneously providing information on the presence of distinct modifications.

Another major challenge for the field has been to elucidate which RNA modifications are functionally important across different cell types or in distinct cellular contexts. Developing more accurate and sensitive methods for sequencing modifications and functionally annotating modified versus unmodified RNAs will provide a better understanding of how and when distinct modifications are regulated dynamically, as well as how the presence of modifications might influence RNA

___________________

6 See https://roadmap.ebrc.org/2019-roadmap/ (accessed October 27, 2023).

structure and RNA–protein interactions. Being able to reliably sequence modifications and measure their abundance would also be valuable for functional studies of epitranscriptomic regulatory proteins (e.g., writers, readers, and erasers) and for assessing the consequences of regulatory protein depletion on modification abundance and distribution.

Additional and improved tools are also needed to more thoroughly investigate how modifications impact human health and disease. Most likely, the earliest progress will be made in modifications for which substantial knowledge and detection methods already exist. Although mouse and cellular models have been instrumental in understanding how RNA modifications impact physiology and pathogenic states, most modifications remain challenging to study in human tissues because of the lack of sensitive, consistent methods for their detection. Thus, improved methods for detecting diverse modifications in humans will be critical to understand how distinct modifications are altered in both healthy and disease states. In addition, improved RNA modification detection methods would facilitate the development of molecular tools for adding or removing specific modifications to transcripts of interest in cells. Given the myriad links between modifications and human disease, improved research tools have great potential to accelerate the discovery and development of novel therapeutics based on RNA modifications. Similarly, these tools will also enhance the ability to select for and engineer crops and other plants to enhance global food security and improve the resiliency of plants to changes in climate.

CONCLUSIONS

Conclusion 2–1: Defining any epitranscriptome by fully delineating the type and extent of all RNA modifications, and in which RNAs they occur, is critical for increasing the understanding of cell growth, division, and differentiation; organismal development and maturation; defense against infection; and the pathogenesis of human disease.

Conclusion 2–2: Since chemical modifications are a fundamental feature of RNA, defining and characterizing these modifications will impact multiple areas of research. This includes not only studies of the processing and function of cellular RNAs, but also investigations of the proteome and general mechanisms of gene expression control and cellular function.

Conclusion 2–3: Each new advance in the technology for determining an epitranscriptome will likely lead to a more complete picture of epitranscriptomes for different organisms, tissues, cell types, and conditions. Each technological advance will provide new knowledge that can be applied toward advancing the understanding and treatment of human diseases such as cancer, diabetes, metabolic disorders, and heart disease.

Conclusion 2–4: The use of RNA-based technologies for treating human diseases is in its infancy. The discovery of new RNA modifications that confer increased stability or immune tolerance and a better understanding of how RNA modifications influence RNA–protein interactions will be essential for the development of new RNA-based drugs.

Conclusion 2–5: Manipulation of RNA modifications in food crops holds great promise for increasing global food security and strengthening the ability of plants to adapt to a rapidly changing climate.

REFERENCES

Abbasi-Moheb, L., S. Mertel, M. Gonsior, L. Nouri-Vahid, K. Kahrizi, S. Cirak, D. Wieczorek, M. M. Motazacker, S. Esmaeeli-Nieh, K. Cremer, R. Weißmann, A. Tzschach, M. Garshasbi, S. S. Abedini, H. Najmabadi, H. H. Ropers, S. J. Sigrist, and A. W. Kuss. 2012. “Mutations in NSUN2 cause autosomal-recessive intellectual disability.” American Journal of Human Genetics 90 (5): 847–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.021.

Adams, D., A. Gonzalez-Duarte, W. D. O’Riordan, C. C. Yang, M. Ueda, A. V. Kristen, I. Tournev, H. H. Schmidt, T. Coelho, J. L. Berk, K. P. Lin, G. Vita, S. Attarian, V. Planté-Bordeneuve, M. M. Mezei, J. M. Campistol, J. Buades, T. H. Brannagan, 3rd, B. J. Kim, J. Oh, Y. Parman, Y. Sekijima, P. N. Hawkins, S. D. Solomon, M. Polydefkis, P. J. Dyck, P. J. Gandhi, S. Goyal, J. Chen, A. L. Strahs, S. V. Nochur, M. T. Sweetser, P. P. Garg, A. K. Vaishnaw, J. A. Gollob, and O. B. Suhr. 2018. “Patisiran, an RNAi therapeutic, for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis.” New England Journal of Medicine 379 (1): 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1716153.

Agrawal, V., N. Sood, and C. M. Whaley. 2023. “The impact of the global COVID-19 vaccination campaign on all-cause mortality.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series: 31812. http://www.nber.org/papers/w31812.

Alazami, A. M., H. Hijazi, M. S. Al-Dosari, R. Shaheen, A. Hashem, M. A. Aldahmesh, J. Y. Mohamed, A. Kentab, M. A. Salih, A. Awaji, T. A. Masoodi, and F. S. Alkuraya. 2013. “Mutation in ADAT3, encoding adenosine deaminase acting on transfer RNA, causes intellectual disability and strabismus.” Journal of Medical Genetics 50 (7): 425–430. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101378.

AlSabbagh, M. M. 2020. “Dyskeratosis congenita: a literature review.” Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft 18 (9): 943–967. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.14268.

Anderson, S. L., R. Coli, I. W. Daly, E. A. Kichula, M. J. Rork, S. A. Volpi, J. Ekstein, and B. Y. Rubin. 2001. “Familial dysautonomia is caused by mutations of the IKAP gene.” The American Journal of Human Genetics 68 (3): 753–758. https://doi.org/10.1086/318808.

Arrondel, C., S. Missoury, R. Snoek, J. Patat, G. Menara, B. Collinet, D. Liger, D. Durand, O. Gribouval, O. Boyer, L. Buscara, G. Martin, E. Machuca, F. Nevo, E. Lescop, D. A. Braun, A.-C. Boschat, S. Sanquer, I. C. Guerrera, P. Revy, M. Parisot, C. Masson, N. Boddaert, M. Charbit, S. Decramer, R. Novo, M.-A. Macher, B. Ranchin, J. Bacchetta, A. Laurent, S. Collardeau-Frachon, A. M. van Eerde, F. Hildebrandt, D. Magen, C. Antignac, H. van Tilbeurgh, and G. Mollet. 2019. “Defects in t6A tRNA modification due to GON7 and YRDC mutations lead to Galloway-Mowat syndrome.” Nature Communications 10 (1): 3967. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11951-x.

Bajan, S., and G. Hutvagner. 2020. “RNA-based therapeutics: From antisense oligonucleotides to miRNAs.” Cells 9 (1). https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9010137.

Baldridge, K. C., M. Jora, A. C. Maranhao, M. M. Quick, B. Addepalli, J. S. Brodbelt, A. D. Ellington, P. A. Limbach, and L. M. Contreras. 2018. “Directed evolution of heterologous tRNAs leads to reduced dependence on post-transcriptional modifications.” ACS Synthetic Biology 7 (5): 1315–1327. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.7b00421.

Barbieri, I., and T. Kouzarides. 2020. “Role of RNA modifications in cancer.” Nature Reviews Cancer 20 (6): 303–322. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-020-0253-2.

Barbieri, I., K. Tzelepis, L. Pandolfini, J. Shi, G. Millán-Zambrano, S. C. Robson, D. Aspris, V. Migliori, A. J. Bannister, N. Han, E. De Braekeleer, H. Ponstingl, A. Hendrick, C. R. Vakoc, G. S. Vassiliou, and T. Kouzarides. 2017. “Promoter-bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia by m6A-dependent translation control.” Nature 552 (7683): 126–131. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24678.

Baruffini, E., C. Dallabona, F. Invernizzi, J. W. Yarham, L. Melchionda, E. L. Blakely, E. Lamantea, C. Donnini, S. Santra, S. Vijayaraghavan, H. P. Roper, A. Burlina, R. Kopajtich, A. Walther, T. M. Strom, T. B. Haack, H. Prokisch, R. W. Taylor, I. Ferrero, M. Zeviani, and D. Ghezzi. 2013. “MTO1 mutations are associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy andlactic acidosis and cause respiratory chain deficiency in humans and yeast.” Human Mutation 34 (11): 1501–1509. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.22393.

Bazak, L., A. Haviv, M. Barak, J. Jacob-Hirsch, P. Deng, R. Zhang, F. J. Isaacs, G. Rechavi, J. B. Li, E. Eisenberg, and E. Y. Levanon. 2014. “A-to-I RNA editing occurs at over a hundred million genomic sites, located in a majority of human genes.” Genome Research 24 (3): 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.164749.113.

Bellodi, C., M. McMahon, A. Contreras, D. Juliano, N. Kopmar, T. Nakamura, D. Maltby, A. Burlingame, Sharon A. Savage, A. Shimamura, and D. Ruggero. 2013. “H/ACA small RNA dysfunctions in disease reveal key roles for noncoding RNA modifications in hematopoietic stem cell differentiation.” Cell Reports 3 (5): 1493–1502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.030.

Boccaletto, P., F. Stefaniak, A. Ray, A. Cappannini, S. Mukherjee, E. Purta, M. Kurkowska, N. Shirvanizadeh, E. Destefanis, P. Groza, G. Avşar, A. Romitelli, P. Pir, E. Dassi, S. G. Conticello, F. Aguilo, and J. M. Bujnicki. 2022. “MODOMICS: A database of RNA modification pathways. 2021 update.” Nucleic Acids Research 50 (D1): D231-D235. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab1083.

Braun, D. A., J. Rao, G. Mollet, D. Schapiro, M.-C. Daugeron, W. Tan, O. Gribouval, O. Boyer, P. Revy, T. Jobst-Schwan, J. M. Schmidt, J. A. Lawson, D. Schanze, S. Ashraf, J. F. P. Ullmann, C. A. Hoogstraten, N. Boddaert, B. Collinet, G. Martin, D. Liger, S. Lovric, M. Furlano, I. C. Guerrera, O. Sanchez-Ferras, J. F. Hu, A.-C. Boschat, S. Sanquer, B. Menten, S. Vergult, N. De Rocker, M. Airik, T. Hermle, S. Shril, E. Widmeier, H. Y. Gee, W.-I. Choi, C. E. Sadowski, W. L. Pabst, J. K. Warejko, A. Daga, T. Basta, V. Matejas, K. Scharmann, S. D. Kienast, B. Behnam, B. Beeson, A. Begtrup, M. Bruce, G.-S. Ch’ng, S.-P. Lin, J.-H. Chang, C.-H. Chen, M. T. Cho, P. M. Gaffney, P. E. Gipson, C.-H. Hsu, J. A. Kari, Y.-Y. Ke, C. Kiraly-Borri, W.-m. Lai, E. Lemyre, R. O. Littlejohn, A. Masri, M. Moghtaderi, K. Nakamura, F. Ozaltin, M. Praet, C. Prasad, A. Prytula, E. R. Roeder, P. Rump, R. E. Schnur, T. Shiihara, M. D. Sinha, N. A. Soliman, K. Soulami, D. A. Sweetser, W.-H. Tsai, J.-D. Tsai, R. Topaloglu, U. Vester, D. H. Viskochil, N. Vatanavicharn, J. L. Waxler, K. J. Wierenga, M. T. F. Wolf, S.-N. Wong, S. A. Leidel, G. Truglio, P. C. Dedon, A. Poduri, S. Mane, R. P. Lifton, M. Bouchard, P. Kannu, D. Chitayat, D. Magen, B. Callewaert, H. van Tilbeurgh, M. Zenker, C. Antignac, and F. Hildebrandt. 2017. “Mutations in KEOPS-complex genes cause nephrotic syndrome with primary microcephaly.” Nature Genetics 49 (10): 1529–1538. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3933.

Burgess, R. W., and E. Storkebaum. 2023. “tRNA dysregulation in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases.” Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 39: 223-252. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cellbio-021623-124009.

Cao, M., M. Donà, L. Valentino, C. Semplicini, A. Maresca, M. Cassina, A. Torraco, E. Galletta, V. Manfioli, G. Sorarù, V. Carelli, R. Stramare, E. Bertini, R. Carozzo, L. Salviati, and E. Pegoraro. 2016. “Clinical and molecular study in a long-surviving patient with MLASA syndrome due to novel PUS1 mutations.” neurogenetics 17 (1): 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10048-015-0465-x.

Cappannini, A., A. Ray, E. Purta, S. Mukherjee, P. Boccaletto, S. N. Moafinejad, A. Lechner, C. Barchet, Bruno P. Klaholz, F. Stefaniak, and J. M. Bujnicki. 2024. “MODOMICS: A database of RNA modifications and related information. 2023 update.” Nucleic Acids Research 52 (D1): D239-D244. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad1083.

Cayir, A., H.-M. Byun, and T. M. Barrow. 2020. “Environmental epitranscriptomics.” Environmental Research 189: 109885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.109885.

Cerneckis, J., Q. Cui, C. He, C. Yi, and Y. Shi. 2022. “Decoding pseudouridine: An emerging target for therapeutic development.” Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 43 (6): 522–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2022.03.008.

Chen, C., W. Liu, J. Guo, Y. Liu, X. Liu, J. Liu, X. Dou, R. Le, Y. Huang, C. Li, L. Yang, X. Kou, Y. Zhao, Y. Wu, J. Chen, H. Wang, B. Shen, Y. Gao, and S. Gao. 2021. “Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates the scaffold function of LINE1 RNA in mouse ESCs and early embryos.” Protein & Cell 12 (6): 455–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13238-021-00837-8.

Chen, J., and J. R. Patton. 2000. “Pseudouridine synthase 3 from mouse modifies the anticodon loop of tRNA.” Biochemistry 39 (41): 12723–12730. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi001109m.

Chen, Y. G., R. Chen, S. Ahmad, R. Verma, S. P. Kasturi, L. Amaya, J. P. Broughton, J. Kim, C. Cadena, B. Pulendran, S. Hur, and H. Y. Chang. 2019. “N6-methyladenosine modification controls circular RNA immunity.” Molecular Cell 76 (1): 96–109.E9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.016.

Chen, Y. G., and S. Hur. 2022. “Cellular origins of dsRNA, their recognition and consequences.” Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 23 (4): 286–301. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-021-00430-1.

Cohen, J. S., S. Srivastava, K. D. Farwell, H. M. Lu, W. Zeng, H. Lu, E. C. Chao, and A. Fatemi. 2015. “ELP2 is a novel gene implicated in neurodevelopmental disabilities.” American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 167 (6): 1391–1395. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.36935.

Crooke, S. T., J. L. Witztum, C. F. Bennett, and B. F. Baker. 2018. “RNA-targeted therapeutics.” Cell Metabolism 27 (4): 714–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.004.

Cui, Q., H. Shi, P. Ye, L. Li, Q. Qu, G. Sun, G. Sun, Z. Lu, Y. Huang, C. G. Yang, A. D. Riggs, C. He, and Y. Shi. 2017. “m6A RNA methylation regulates the self-renewal and tumorigenesis of glioblastoma stem cells.” Cell Reports 18 (11): 2622–2634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.059.

Cui, Q., K. Yin, X. Zhang, P. Ye, X. Chen, J. Chao, H. Meng, J. Wei, D. Roeth, L. Li, Y. Qin, G. Sun, M. Zhang, J. Klein, M. Huynhle, C. Wang, L. Zhang, B. Badie, M. Kalkum, C. He, C. Yi, and Y. Shi. 2021. “Targeting PUS7 suppresses tRNA pseudouridylation and glioblastoma tumorigenesis.” Nature Cancer 2 (9): 932–949. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-021-00238-0.

Dai, Q., L.-S. Zhang, H.-L. Sun, K. Pajdzik, L. Yang, C. Ye, C.-W. Ju, S. Liu, Y. Wang, Z. Zheng, L. Zhang, B. T. Harada, X. Dou, I. Irkliyenko, X. Feng, W. Zhang, T. Pan, and C. He. 2023. “Quantitative sequencing using BID-seq uncovers abundant pseudouridines in mammalian mRNA at base resolution.” Nature Biotechnology 41 (3): 344–354. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01505-w.

Darvish, H., L. J. Azcona, E. Alehabib, F. Jamali, A. Tafakhori, S. Ranji-Burachaloo, J. C. Jen, and C. Paisán-Ruiz. 2019. “A novel PUS7 mutation causes intellectual disability with autistic and aggressive behaviors.” Neurology Genetics 5 (5): E356. https://doi.org/10.1212/nxg.0000000000000356.

Davarniya, B., H. Hu, K. Kahrizi, L. Musante, Z. Fattahi, M. Hosseini, F. Maqsoud, R. Farajollahi, T. F. Wienker, H. H. Ropers, and H. Najmabadi. 2015. “The role of a novel TRMT1 gene mutation and rare GRM1 gene defect in intellectual disability in two Azeri families.” PLOS ONE 10 (8): E0129631. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129631.

David, R., A. Burgess, B. Parker, J. Li, K. Pulsford, T. Sibbritt, T. Preiss, and I. R. Searle. 2017. “Transcriptome-wide mapping of RNA 5-methylcytosine in arabidopsis mRNAs and noncoding RNAs.” The Plant Cell 29 (3): 445–460. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.16.00751.

Davis, L. E., S. C. Shalin, and A. J. Tackett. 2019. “Current state of melanoma diagnosis and treatment.” Cancer Biology & Therapy 20 (11): 1366–1379. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384047.2019.1640032.

de Brouwer, A. P. M., R. Abou Jamra, N. Körtel, C. Soyris, D. L. Polla, M. Safra, A. Zisso, C. A. Powell, P. Rebelo-Guiomar, N. Dinges, V. Morin, M. Stock, M. Hussain, M. Shahzad, S. Riazuddin, Z. M. Ahmed, R. Pfundt, F. Schwarz, L. de Boer, A. Reis, D. Grozeva, F. L. Raymond, S. Riazuddin, D. A. Koolen, M. Minczuk, J.-Y. Roignant, H. van Bokhoven, and S. Schwartz. 2018. “Variants in PUS7 cause intellectual disability with speech delay, microcephaly, short stature, and aggressive behavior.” The American Journal of Human Genetics 103 (6): 1045–1052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.10.026.

de la Torre, D., and J. W. Chin. 2021. “Reprogramming the genetic code.” Nature Reviews Genetics 22 (3): 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-020-00307-7.

Dedon, P. C., and T. J. Begley. 2014. “A system of RNA modifications and biased codon use controls cellular stress response at the level of translation.” Chemical Research Toxicology 27 (3): 330–337. https://doi.org/10.1021/tx400438d.