Charting a Future for Sequencing RNA and Its Modifications: A New Era for Biology and Medicine (2024)

Chapter: 5 Driving Innovation to Study RNA Modifications

5

Driving Innovation to Study RNA Modifications

Chapters 1 and 2 of this report provide an overview of the evolution and current state of the epitranscriptomics field and establish the need for sequencing RNA and its modifications. Those chapters consider important applications with the potential to benefit patients, advance public health, and address other important societal goals. Chapters 3 and 4 provide an overview of the foundational components required for such a sequencing effort—tools and technologies, standards, and databases—and associated gaps and challenges, as well as emerging solutions. This chapter draws on those preceding as it describes several drivers of innovation expected to propel new technology and application development and accelerate the study of RNA modifications.

The field of RNA biology needs accurate, reproducible, and universally available tools and technologies for sequencing RNA and its modifications; a vibrant space where industry and academic researchers both compete and collaborate in creating and refining those tools and technologies; an end market sufficient to attract companies and guide innovation; and substantial public and philanthropic funding to address major barriers to progress. Furthermore, innovation in tools and technologies and in the application of RNA science requires a strategy that maintains U.S. leadership while recognizing the benefits of international collaboration. It is also contingent on having a well-educated, well-trained, and diverse workforce and an informed and supportive public.

In addition, several factors could accelerate the pace of innovation, thereby quickening the development of tools and technologies for sequencing RNA and its modifications and a range of downstream applications, including more advanced RNA-based vaccines and therapeutics. As this chapter will discuss, factors for accelerating innovation include (1) specialized facilities for mapping and sequencing RNAs, (2) ready availability of necessary reagents and physical standards (building on Chapter 4), and (3) a supportive policy environment.

Finally, by nature, a large-scale initiative that is effective in driving innovation will require leadership and strategic coordination of efforts and resources across sectors and agencies. This chapter concludes by covering how initiatives of similar scale have addressed these challenges, beginning with the Human Genome Project, with the goals of identifying lessons learned, illustrating a range of options, and suggesting a path forward for epitranscriptomics.

IMPORTANT DRIVERS OF INNOVATION

Innovative Tools and Technologies for Sequencing

Expanding the Toolbox

Each of the approximately 170 known RNA modifications has a unique chemical makeup and distinct biochemical and biophysical properties (Cappannini et al., 2024). Furthermore, some modifications are added and removed from RNA depending on cellular conditions that are affected by a variety of different factors (discussed in Chapter 2). Thus, mapping multiple modifications on an RNA molecule, let alone determining an epitranscriptome, is a complex task. For this reason, nearly all studies to date have examined specific RNA modifications in isolation; thus, for the vast majority of RNAs, there are no data on whether different modifications occur on the same RNA molecule. This substantially limits the understanding of whether modifications compete or coordinate to regulate RNA fate and processing, and whether the presence of one type of modification influences the reading, writing, or erasing of other modifications. Answering such questions is critical for a complete understanding of how an epitranscriptome is regulated.

By directly sequencing single RNA molecules from end to end, researchers would gain unprecedented insights into the chemical makeup of individual RNAs and their isoforms, thereby enabling the generation of new testable hypotheses regarding the regulation, competition, and coordination of distinct RNA modifications. This, in turn, could shed light on RNA processing and function and open numerous exciting new avenues of research. Furthermore, developing affordable and user-friendly RNA sequencing technologies that can directly and accurately identify all chemical modifications on a single RNA molecule simultaneously would bolster the outcomes of epitranscriptomics research by making tools more widely accessible for use in basic and applied research and in the clinic.

Modifications are currently studied and sequenced directly and indirectly using a variety of methods (see Chapter 3), which has contributed to inconsistencies in reports of where modifications reside, their levels, and how they are regulated. The different findings have led to discrepant conclusions regarding how these modifications function. Developing new direct sequencing methods that allow for quantitative and simultaneous mapping of chemical modifications in RNAs would ideally provide a unified platform for mapping RNA modifications, improving consistency across research studies and setting the stage for translation of this knowledge into applications that benefit patients and the broader society.

Nanopore sequencing is currently the dominant direct sequencing technology used in the RNA field. Although it is very promising, the instrumentation from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) needs further development in several areas to fully realize its potential in sequencing RNA and its modifications (see Box 3-1 in Chapter 3 for technical details on the method). Specifically, it faces limitations in throughput, range of detected modifications, accuracy, and computational analysis. Some of these limitations are interrelated. For example, improvements to motor proteins and the nanopore itself can impact both accuracy and throughput. Better computational methods and a more unified framework for analyzing current data and inferring the presence of modifications are also greatly needed.

Other companies are developing alternatives to ONT nanopore sequencing for direct sequencing of RNA and its modifications. During a May 2023 information-gathering session (see Appendix C), the committee spoke with founders and employees of several start-up companies that are developing direct sequencing technologies. However, few of the companies the committee heard from have begun working with RNA. Armonica Technologies uses a nanopore platform to sequence nucleic acids, but its physical principles and detection system differ from ONT’s. The Armonica

detection system is based on measuring the vibrational frequency “fingerprint” of each nucleotide using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. This provides a direct readout of individual RNA molecules, including their modified nucleotides. Armonica is working to overcome the challenges associated with manufacturing a system that is reproducible and sensitive enough to provide high-accuracy data on any RNA molecule and its modifications. Roswell Biotechnologies has developed a nanoscale platform that incorporates a “molecular wire” into a circuit. A molecular probe, which is conjugated to the molecular wire, binds a target molecule, causing a shift in the current that is passing through the circuit. The changes in current are read by a complementary metal oxide semiconductor sensor and software converts the electrical signals into molecular information, such as a DNA sequence. A challenge for Roswell Biotechnologies in applying its method to sequencing RNA and its modifications will be choosing a probe that can “read” a target RNA and its modifications.

Establishing Competitive and Collaborative Spaces

Healthy competition and collaboration are major drivers of innovation in all fields of scientific research and development, and the committee believes that achieving direct sequencing of RNA modifications will be no different. Academic laboratories and a small number of companies have been at the forefront of developing direct sequencing strategies. One of the biggest limitations that this effort currently faces, however, is the dominance of direct RNA sequencing by a single company and technology: ONT and nanopore sequencing technology.

Expanded competition is needed to spur innovation in nanopore technology and is also critical to attract market entrants with the capacity to develop other technologies for sequencing RNA modifications. For instance, Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) offers a single-molecule, long-read sequencing method that enables end-to-end sequencing of individual RNA molecules via conversion to complementary DNA using reverse transcription (Au et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2016). Such indirect sequencing methods could potentially be coupled with biochemical approaches to enable mapping of RNA modifications. In addition, replacing DNA polymerase by reverse transcription may enable PacBio to offer direct RNA sequencing, potentially providing a viable alternative to ONT (see Chapter 3).

Mass spectrometry–based approaches for direct mapping of RNA modifications have been used successfully to identify diverse modifications in short RNAs, such as transfer RNAs (tRNAs) (Yan et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). Further development of such approaches could lead to novel methods for mapping modifications in longer RNAs as well.

In addition to more competition, the field would benefit from academic and industry partnerships at early stages of technology research and development. Academic–industry collaborations would be a powerful approach that could build on the strengths of each sector. Academics have extensive knowledge of the basic chemical, biological, and physiological properties of individual RNA modifications, as well as their translational potential, while industry leaders have tools and resources that enable more rapid progress than can be achieved by academic laboratories alone. Such partnerships could lead to the augmentation of existing technologies in novel ways. Several academic laboratories have made improvements to nanopore sequencing capabilities, largely by developing novel computational methods, while some have engineered nanopores with new capabilities (Wang et al., 2022). Academic labs have recently developed chemical and enzymatic methods for distinguishing chemically modified bases from unmodified bases in RNAs (Liu et al., 2023; Xiao et al., 2023). These methods combined with direct RNA sequencing could potentially circumvent the need for complex computational analysis strategies to call modified bases.

Incentivizing the development of novel direct sequencing technologies, leveraging the drivers of innovation discussed in this chapter, could expand competition and collaboration and move the

field closer to achieving its sequencing and mapping goals. Forming academic–industry partnerships would facilitate the identification of common problems and joint workflows; combining efforts would augment ways to address shared problems in technology development. The result would be much more rapid progress at early stages in technology development, while maintaining the opportunity for companies to expand on those technologies in competitive spaces.

Creating Markets

Technological innovation is driven by “pull” factors that make investment more attractive or less risky, and “push” factors, such as the availability of external grants or subsidies for research and development activities. Creation (or expansion) of markets will be an important pull factor in motivating both small and large companies to develop direct RNA sequencing technologies. Academic laboratories are a major market for these companies, so expanding research on RNA modifications and encouraging technology development in academia is likely to spur continued technology improvements in industry as well. This includes not only direct RNA sequencing methods themselves, but also synthesis of oligonucleotides and other modified reference standards and development of computational analysis tools.

A clear pathway to profit and sustainable growth is critical to justify the investment of resources and capital. Larger, established companies, which in some cases have the capital and resources to make more significant contributions to an emerging field, may require a larger economic opportunity to motivate action. Smaller companies with less capital and resources, including start-up companies, may seek out smaller, emerging, or higher-risk market opportunities in anticipation that the market will grow their company.

During a committee information-gathering session in July 2023 (see Appendix C), representatives from larger companies—such as Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bruker, Agilent, and Waters—expressed the importance of a market need in driving innovation and production of tools and technologies for RNA modifications. For example, the Thermo Fisher Scientific representative noted that their company’s move toward advancing RNA-related mass spectrometry technologies was inspired by market needs related to new mRNA vaccines and therapeutics. Many major market opportunities exist to support the development of RNA therapeutics (e.g., small interfering RNAs, guide RNAs, mRNA vaccines). The demand for RNA therapeutics has accelerated the development of tools, methods, and technologies for quality control and quality assurance. Pharmaceutical companies have partnered with developers of RNA standards and mass spectrometry instrumentation to develop references, workflows, sequencing technology, and sequence analysis tools.

While the existing market drivers around these RNA vaccines and therapeutics have resulted in tangible advances in the development of RNA modification–related technologies, they are unlikely to alone provide a sufficient trajectory for achieving the overarching goal of developing robust and accessible technology to sequence, map, and quantify all RNA modifications. Additional market drivers, as well as technology push, will be needed.

One promising emerging market opportunity is identifying drug targets related to RNA modifications. During a committee information-gathering session in May 2023 (see Appendix C), several start-up companies—including STORM Therapeutics, Gotham Therapeutics (recently acquired by 858 Therapeutics), and Accent Therapeutics—reported raising significant capital (more than $50 million each) to develop drugs that target RNA-modifying enzymes. Commercial success of this new class of drug targets has the potential to drive the development of more advanced sequencing and mapping technologies by establishing a precedent for the value of discovering new roles for RNA modification and new druggable pathways and targets. However, outside a public health emergency context, the timeline for developing and testing therapeutics can be lengthy.

Funding Technology Development Across Scales

A broad range of funding opportunities that promote technology development and breakthrough innovations will be critical for enabling sequencing of any epitranscriptome. Several federal funding sources and mechanisms have a role to play. Government funding sources such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Biological Technologies Office within the Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (including the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health [ARPA-H]), the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the Department of Energy (DOE) are major drivers of technological innovation. More funding opportunities are needed from these agencies to promote the critical, early-stage development required to eventually enable direct sequencing of RNA and all of its modifications. The optimal funding mix could include the kind of organizational approach pioneered by DARPA and now taken up by ARPA-H—the convergence of different expertise (e.g., biology, engineering, computer science) in pursuit of a specific goal under the leadership of a program manager—as well as funding mechanisms typically employed by NIH Institutes and Centers and NSF to support tool and technology development.

Such funding opportunities need to target not only academic research laboratories, but also small businesses using, for example, Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer programs.1 In addition, funding from private foundations will provide a much-needed, complementary source of support for tool and technology development. Awards that support cooperative research efforts (e.g., multiple academic laboratories, academic–industry partnerships) will provide important opportunities for accelerated research progress. Sponsored competitions may also be highly productive. For example, open competitions for the development of computational analysis methods for calling chemical modifications from direct RNA sequencing data could lead to novel machine learning training models. Sponsored competitions have been highly successful in related fields of molecular biology; one example is the Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) competition, which takes place every 2 years with the goal of innovating improved methods for protein structure prediction. The CASP competition helped lead to the development of AlphaFold, an artificial intelligence–based prediction platform that has revolutionized the way researchers study protein structure (Jumper et al., 2021).

Overall, an increase in funding opportunities from a variety of sources will be critical for supporting the research and technology development effort that is needed to overcome the current limitations that RNA modifications sequencing technologies face. Such funding is particularly critical at early stages of development; major barriers to widespread adoption of these technologies have included a lack of definitive methods for identifying signatures of individual chemical modifications, inconsistent nanopore performance, and issues related to input requirements and throughput. These technical hurdles can be overcome much more quickly with increased investment.

Maintaining Global Leadership

In addition to efforts ongoing in the United States, governments in several other countries are dedicating significant funds and resources toward researching RNA biology and developing RNA-based biotechnologies, opening opportunities for international collaboration.

A prominent example is Germany’s Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), the country’s scientific research funding body, which has earmarked 30–50 million euros toward the RNA Modification and Processing (RMaP) program (DFG, 2021, 2023). As presented to the study committee at a March 2023 National Academies workshop, Mark Helm, lead investigator for RMaP, suggested that the effort has the potential to run until 2033, assuming funding continues. This program is based on a previous effort that ran from 2015 to 2021, which looked at the chemical biology of

___________________

1 See https://www.sbir.gov/about (accessed November 6, 2023).

native nucleic acid modifications. The RMaP program leverages individual scientific expertise by providing support for individual researchers and establishes collaborations and centers where experts and instrumentation are accessible to all individuals who are funded by the program. The investment signals the importance of RNA modifications research to Germany. As Helm suggested, if the program runs until 2033, the DFG will have spent approximately 60 million euros on the effort over the course of 18 years (Helm, 2023).

Other countries, including Australia and Canada, have published reports about and/or initiated large-scale funding efforts for studying RNA biology. In July 2021, the Australian Academy of Sciences released a rapid report outlining its national priorities for RNA science and technology (Australian Academy of Science and the Australia and New Zealand RNA Production Consortium, 2021). The report notes important priorities for RNA research, including “RNA chemistry,” and goes on to recommend “a national mission for the whole RNA science and technology pipeline in Australia, driven by strategic investment and prioritization across funding schemes” (Australian Academy of Science and the Australia and New Zealand RNA Production Consortium. 2021, p. 2). Following the release of this report, the government of New South Wales initiated a funding program around RNA research, committing 119 million Australian dollars over 10 years (Office of the NSW Chief Scientist and Engineer, n.d.). Additional programs and calls for funding have emerged from the state government of Victoria in Australia (State Government of Victoria, 2023) and the Australian government’s Department of Industry, Science and Resources (Department of Industry, Science and Resources, 2021). Canada has invested 165 million Canadian dollars in a center at McGill University called DNA to RNA, described as “an inclusive Canadian approach to genomic-based RNA therapeutics” (Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat, 2023, p. 1). These efforts arose in the last 3 years, pointing to the rising importance of RNA research and technology on an international scale.

The United States currently has several calls for research proposals from federal agencies and has established RNA research centers at a number of institutions. For example, the recent program solicitation by NSF in coordination with the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), part of NSF’s program Molecular Foundations for Biotechnology, is titled “Partnerships to Transform Emerging Industries—RNA Tools/Biotechnology” and has an anticipated funding of $10 million. The program’s synopsis calls for “creative, cross-disciplinary research and technology development proposals to accelerate understanding of RNA function in complex biological systems and to harness RNA research to advance biotechnology” (NSF, 2023, para. 2). In August 2023, ARPA-H announced up to $24 million in funding for the Curing the Uncurable via RNA-Encoded Immunogene Tuning (CUREIT) project. The aim is to train the immune system to fight cancer and other diseases more effectively by developing generalizable mRNA platforms.2 Also of note, NHGRI funds two Centers for Excellence in Genomic Sciences focused on RNA modifications: the Center for Genomic Information Encoded by RNA Nucleotide Modifications, based at Weill Cornell Medicine, and the Center for Dynamic RNA Epitranscriptomes, based at the University of Chicago.3 Further, in 2019 the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) launched the Functional RNA Modifications Environment and Disease program, an initiative to investigate the impact of environmental exposures on RNA modifications.4

While a few U.S. federal agencies are providing clear leadership and investment in this space, there is currently no overarching, strategic U.S. government effort of coordinated investment in the study, sequencing, and mapping of RNA modifications. The international landscape of RNA-focused efforts thus presents direct competition, as well as opportunities, for U.S. laboratories and

___________________

2 See https://arpa-h.gov/news/first-baa/ (accessed October 29, 2023).

3 See https://www.genome.gov/Funded-Programs-Projects/Centers-of-Excellence-in-Genomic-Science/CEGS-Awards (accessed October 29, 2023).

4 See https://factor.niehs.nih.gov/2018/7/science-highlights/council (accessed November 15, 2023).

companies and highlights that continuing U.S. leadership in this space is by no means assured. And while there can be a tension between driving a field forward rapidly through the creation of global public goods (e.g., the standards and databases described earlier in this report) and maximizing national advantage, the Human Genome Project (HGP) illustrates the potential for a large-scale initiative to simultaneously advance open science and stimulate innovation and commercial ventures that yield immense benefits to the U.S. economy. The HGP and other examples of prior large-scale initiatives are discussed in more detail below (Box 5-1 and surrounding text).

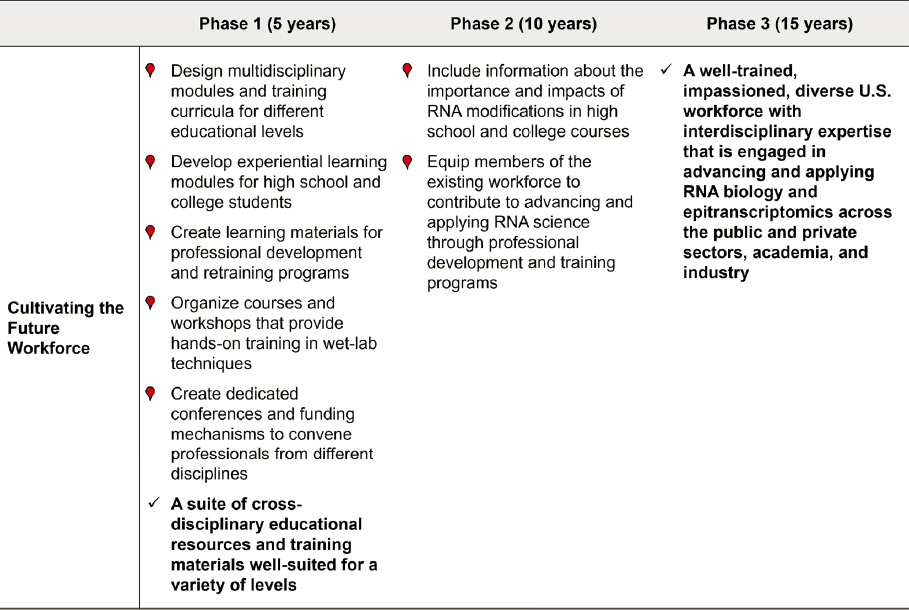

Educating and Training the Future RNA Workforce

When the HGP was merely a concept (NRC, 1988), education in molecular biology focused on DNA’s transcription to RNA that is then translated to proteins. Curiously, the emphasis in both science education and research was predominantly on DNA and proteins, while RNA was largely ignored. The three principal RNAs involved in protein synthesis were believed by many to be largely passive participants: mRNAs transmitted the genetic code for a protein, ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) were supporting actors in the ribosome, and tRNAs shuttled amino acids to the ribosome. The catalog of RNA biotypes has grown substantially in the past 35 years, as has appreciation for the importance of RNA modifications and of the regulatory and enzymatic roles that RNAs play in cells.

Clearly, the central roles of RNAs in biological processes need to be taught as core components of biology curricula. As discussed in Chapter 2, studying RNA modifications is important for understanding diverse aspects of the life sciences and the underlying mechanisms governing health and disease across organisms. As such, research on RNA and its modifications is an increasingly interdisciplinary endeavor, and training programs for the RNA modifications workforce need to reflect this.

The field is growing at a rapid pace and the workforce needs to be expanded to include individuals with diverse expertise, experience, and interests. Many skills needed by an RNA modifications workforce are broadly applicable across the life sciences (NASEM, 2016a,b). To meet the needs of this growing enterprise, the workforce can be built by both preparing new entrants through academic pathways and leveraging the current workforce through retraining and professional development programs.

During an information-gathering session in June 2023 focused on building the RNA workforce (see Appendix C), the committee heard from experts in education and workforce development, as well as undergraduate and graduate students currently studying RNA biology. Speakers highlighted how to better understand ways to excite, recruit, and retain the next generation to pursue the study of and seek careers in RNA biology. The committee also heard how to better integrate RNA biology into existing STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education to promote earlier engagement and exposure to RNA biology with the aim of promoting awareness of and interest in the topic. Students currently studying RNA biology commented that incorporating RNA biology into high school education could open students’ eyes earlier to the impact of RNA and its modifications on society.5

Incorporating RNA biology into high school education could lead to a more informed population, which will be important as mRNA vaccines and other RNA-based diagnostics and therapeutics enter clinical and public health spaces (see “Public Outreach” below). Generally, earlier engagement has been shown to improve recruitment and retention of students who have been historically underrepresented in STEM (Calabrese Barton et al., 2013; Maltese and Tai, 2010; NASEM and IOM, 2011; NSB, 2022). Increasing diversity within a workforce has been shown to promote

___________________

5 Presentation to the committee from Adedeji Aderounmu and Sahiti Somalraju, June 21, 2023. See Appendix C.

innovation when combined with a positive and inclusive work environment (Galinsky et al., 2015). Greater diversity will also have downstream impacts for ensuring the equitable use and application of innovations and technologies in research (NASEM, 2023). Evidence has also shown that women and underrepresented minorities in STEM have been drawn to careers with clear paths to societal impact (Thoman et al., 2014), which could be argued is the case for the field of RNA biology, given the significant societal impact demonstrated by the success of mRNA vaccines in combatting the COVID-19 pandemic. While the following sections focus primarily on education and career levels post high school, the committee notes that including RNA in high school education also could help expand or promote interest in the field.

Educating and Training the Incoming Workforce

Technical Education and Training

As the field grows, the need for technicians in both academia and industry will likely increase, and developing technical education and training programs will be important (Lewis, 2023). These programs could be made available through community colleges, universities, and colleges. Training can also be offered in the form of apprenticeships, other hands-on learning approaches, and industry–community college training alliances.

Undergraduate Education and Training

In undergraduate education, the chemistry (e.g., structure and properties) of RNA modifications and the biology (e.g., regulation and function) of modified RNAs are topics that need to be integrated into general molecular biology and biochemistry courses. Advanced courses in RNA biology could also be developed and made available to stimulate a more specialized focus. Computational competence has become an essential skill for today’s STEM workforce, given the need to analyze ever-increasing amounts of high-throughput data. Therefore, biology courses also need to provide training in computational biology and bioinformatics. Such mechanisms as NIH T32 training grants6; NSF Research Experiences for Undergraduates7; and the Pathways to Success Program, a partnership between the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute8 that focus on undergraduate education could provide paid or for-credit research experiences so that students have opportunities to identify as scientists and experience, firsthand, the impact they might have through RNA-related research. Generally in STEM, opportunities for undergraduates to be paid for research have important benefits, including opening research as a possibility to students who are economically disadvantaged (NASEM, 2017). In the classroom and the laboratory, highlighting the importance and impacts of RNA biology in addressing societal issues such as epidemics, food security, and climate change and identifying the many technological and biological gaps in knowledge could draw more students to the field.

Graduate and Postgraduate Education and Training

Much of the research on RNA modifications is carried out in academic laboratories by graduate students and postdoctoral fellows. The study of RNA modifications requires knowledge from many disciplines, including chemistry and molecular biology—the former to understand the chemical

___________________

6 See https://researchtraining.nih.gov/programs/training-grants/T32-a (accessed October 27, 2023).

7 See https://new.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/research-experiences-undergraduates-reu (accessed October 27, 2023).

8 See https://www.hhmipathways.ucla.edu/ (accessed October 27, 2023).

differences between modified nucleosides in RNA molecules and the latter to carry out the biochemical and enzymatic protocol steps for detecting and quantifying modifications. Training topics need to include a variety of nucleic acid sequencing techniques (next- and third-generation sequencing); mass spectrometric and -omics approaches; computation and bioinformatics, including artificial intelligence and data science methodology; and biostatistics. Understanding in these areas is critical for analyzing the large datasets generated from mapping RNA modifications and sequencing modified RNA transcripts. A major part of studying RNA modifications depends on bioinformatic analysis pipelines to process high-throughput sequencing data and derive conclusions from these data. Funding mechanisms such as NIH T32 training grants (e.g., training programs for Genetics, Chemistry-Biology Interface, Biotechnology9), individual predoctoral (F30/F31) and postdoctoral (F32) fellowships offered by NIH,10 and NSF’s Research Traineeship program11 could facilitate creating curricula for specialized training in RNA modifications at the pre- and postdoctoral levels.

Finding Success in Recruiting and Retaining Students

To recruit and retain students, it is important to ensure that they gain both an awareness of RNA biology as an important and exciting field and knowledge of technologies that are emerging from the field. These objectives include integrating content on the diversity of RNA biotypes and modifications, the utility of RNA as a research tool, diseases caused by disruption of processes involving RNA, and its use in vaccines and therapeutics (e.g., COVID-19 vaccine, cancer immunotherapy).

In higher education programs, students need to develop interdisciplinary skills for competency in fields related to RNA and its modifications. These skills include computing, machine learning, artificial intelligence, big data collection and analysis, biostatistics, and critical thinking. Educational programs that are already being implemented successfully can serve as models for training. In addition, online educational options can be developed to scale up these educational programs to meet future workforce needs and to create more equitable access to training.

It is important to think about how to balance the need to provide training for traditional industry with the desire to equip students with more diverse and open-ended skill sets. One approach is for academic institutions and industries to collaborate on transitional training programs in the RNA field, such as internships and apprenticeships. Excitement about RNA science will likely not be generated by simply training students to do mechanical tasks and operations; internships and apprenticeships often include hands-on experiences that may promote engagement.

Preparing the Existing Workforce

Developing a workforce for an emerging scientific field such as RNA biology and epitranscriptomics requires training both new and existing workers. Workforce development in emerging technical areas typically focuses on STEM students and recent graduates, though, and mid- and senior-level career professionals in relevant areas of research and business are often overlooked. Professional development and retraining needs for established professionals are distinct from those of people just entering the field because established professionals may learn in different ways, have different motivations and greater levels of experience, and be in different places in their lives than students and early-career professionals.

Managers and company executives can support and expand the expertise of their workers in fields related to RNA biology by staying current on the latest technology, fruitful emerging

___________________

9 See https://www.nigms.nih.gov/training/instpredoc/Pages/PredocDesc-Contacts.aspx (accessed October 27, 2023).

10 See https://www.nichd.nih.gov/grants-contracts/training-careers/extramural/individual (accessed October 27, 2023).

11 See https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2021/nsf21536/nsf21536.htm (accessed November 6, 2023).

technologies, and research developments; supporting team science; cultivating the strengths of both specialists and generalists; and providing opportunities for workers to learn new skills and workflows.

Community-based organizations that provide midcareer workforce development, such as community colleges and workforce training centers, need to be made aware of the career opportunities in emerging biotechnologies, such as occupations in companies focused on applications of RNA science. Human resource personnel and corporate management in biomanufacturing need to recruit from community colleges and workforce training centers if they are not already doing so. Hiring personnel also need to revise how they evaluate applicants coming from nonuniversity programs. People from these pools may have experience but lack the credentials typically expected (e.g., Ph.D. in a related area, history of cGMP12 operations support).

For companies, staying technically current and repositioning an existing workforce takes time and talent that may be at odds with a company’s strategic business plans. Although the marketplace may not always support companies in allocating time and resources to reposition mid- and late-career professionals, failing to garner resources and not allowing time for retraining and redeployment of existing staff is a missed opportunity.

One way to encourage these changes within companies would be to develop a framework or guidelines that companies could use to draw on a more diverse workforce and successfully expand the skills of their employees. Such guidelines could be developed by groups representing commercial manufacturing (e.g., Manufacturing USA, International Society of Pharmaceutical Engineering, Parenteral Drug Association). It would also be helpful for these groups to devise an associated communication plan targeting talent management programs and hiring managers. The development of these guidelines and communication plan and their dissemination could be funded through the Department of Commerce (DOC).

Cross-Cutting Educational and Training Opportunities and Materials

Beyond formal training in the major areas outlined above, the committee encourages the creation of workshops and courses, such as those offered by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories and Jackson Laboratories, that provide hands-on training in wet-lab techniques and data analysis for comparable fields (e.g., epigenetics). Workshops are one way to introduce graduate students, postdocs, and faculty to the state-of-the-art science happening in the field of RNA modifications and sequencing. It would be valuable to introduce trainees and members of the existing workforce to current opportunities within this field via forums, panels, technical courses, and workshops held at RNA and biochemistry conferences. This would have the additional benefits of giving the field greater exposure and helping to stimulate broad interest.

Access to a standardized database of RNA modification sequencing data would facilitate sharing of existing datasets. In turn, educational initiatives that train students and members of the existing workforce using available sequencing data would allow them to contribute intellectually through practice in data analysis and computational workflows that are required for mapping and quantifying RNA modification data, and in some cases contribute to the development of new computation analysis pipelines and generation of new insights. Since sequencing technologies, mapping software, and computational pipelines are rapidly evolving and can become obsolete and replaced by more accurate and precise approaches, it will be important to keep access to these resources up to date. One way to achieve that is to form a consortium that would facilitate and maintain a unified, standardized, and up-to-date ensemble of databases and associated educational resources that

___________________

12 cGMP stands for current Good Manufacturing Practices. See https://www.fda.gov/drugs/pharmaceutical-quality-resources/current-good-manufacturing-practice-cgmp-regulations (accessed March 12, 2024).

are made available to a wide variety of educators and practitioners, such as high school teachers, college and university professors, and industry group leaders.

Facilitating Cross-Disciplinary Engagement

To go beyond current technology, the RNA workforce will need expertise from and training in numerous disciplines including RNA biology, molecular biology, biochemistry, chemistry, engineering, physics, and computer science. Disciplines outside of the basic life sciences can make seminal contributions if ample opportunities are created for engagement across disciplines. For example, engineers developed protein nanopores that are the basis of nanopore sequencing of DNA and RNA, as discussed in Chapter 3 of this report. Engineering innovations could be key drivers in the development of new technologies for direct sequencing of full-length RNAs with all of their modifications. Both physical and data ground truth standards will be required for benchmarking existing and new approaches, and for ensuring reproducibility in the study of RNA modifications. Chemists could advance the synthesis of novel phosphoramidites used in making standards for RNA modifications. Computer and data scientists are needed to develop algorithms and machine learning models to infer modification sites from RNA sequencing data. Funding mechanisms, incentives, and convening activities such as conferences that bring together experts from different fields could have a significant impact on solving the technological challenges associated with sequencing all RNAs with their full collection of modifications.

Public Outreach

Most people are now aware of the term mRNA because it is a component of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. This is a good starting point for expanding the public’s awareness and knowledge of what RNA is and what RNA can be used for in medicine, agriculture, and manufacturing. As noted above, an understanding of the vital roles that RNA and its modifications play in health and disease, and how this understanding can be harnessed to mitigate societal challenges, will help to recruit people into the workforce in the field of RNA science. Including information about RNA and its modifications in educational curricula is important, but there is also a need for scientific communication and engagement through public lectures, discussions, and written media that explain the importance of current research and how it could impact human and planetary health. Public engagement and interest will help drive the field forward and open the door for both public and private investment. In addition to engaging the general public, comprehensive communication and outreach strategies directed at scientists, engineers, technologists, medical professionals, and executives in relevant industries would be very impactful. Therefore, finding effective ways to bring this information to a larger audience is critical.

Including the importance of RNA modifications in programs, lecture series, and conferences geared toward experts in different fields of study would help to catalyze collaboration and interest in the field. Additionally, games may help reach and engage multiple audiences. For example, the online game Eterna engages the public in RNA science (Lee et al., 2014) by crowdsourcing new ways to fold RNA molecules. Scientists then test these ideas in the laboratory, potentially leading to the development of new medicines. Eterna players, a group that includes students and members of the general public, contribute to advancing the field as they solve puzzles by designing a pattern of bases to meet certain design requirements or target RNA shapes.13 In addition, as another engagement tool, RNA modification datasets shared for educational and training purposes could

___________________

13 See https://eternagame.org/about (accessed January 18, 2024).

be made accessible to citizen scientists,14 allowing them to analyze and contribute to the development of new computation analysis pipelines and extract new insights. These approaches could be implemented broadly, reaching institutions that lack advanced instrumentation and providing early exposures to key skill sets in big data analysis that are highly needed in the workforce.

ACCELERATORS OF INNOVATION

Public awareness of RNA grew enormously during the COVID-19 pandemic, given that two of the vaccines were mRNA based. As this report has highlighted (and as the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine validated), the success of mRNA vaccines was due to years of basic research on RNA modifications (see Box 2-1 in Chapter 2). The translation of this basic research into a product that, without exaggeration, has been transformational, underscores how significant RNA science is today.

RNA science will continue to move forward if all the drivers of innovation are put into play. However, without changes that foster innovation and risk-taking in the development of direct sequencing technologies, the pace and robustness of innovation are in question, and the United States risks falling behind other countries that are making significant investments in RNA-related research and development. In addition to objectives already discussed—direct investment by the public and private sectors in the development of tools and technologies; support for the creation of data standards and data infrastructure; and the formation of educational, training, and outreach infrastructures—the committee concluded that attention to three key areas would powerfully accelerate needed innovation: core instrumentation facilities, reagents and physical standards (building on Chapter 4), and leveraging supportive policies. Progress in these areas will speed the sequencing and mapping of RNA modifications at scale and catalyze the translation of new knowledge into innovative RNA-based products.

Core Instrumentation Facilities

Many of the current technologies available for mapping and sequencing RNA modifications rely on expensive and complex technologies and specialized knowledge to operate the instruments. It is impractical for every research institution and private company to acquire the instrumentation and personnel with the skills and expertise needed to operate such technologies. In other highly specialized fields, institutions build centralized research facilities that operate with staff and instruments available for accomplishing research tasks for the laboratories of a particular institution or surrounding institutions. These facilities come in many different forms, including government-funded national labs, such as those run by DOE, and core facilities at universities. The various types of core facilities and their utilities in the life sciences are discussed elsewhere (see, e.g., Farber and Weiss, 2011).

This section will briefly discuss the current state of core facilities in two key areas conducive to advancing RNA modifications research: DNA-sequencing facilities and mass spectrometry facilities. Other centralized facilities and services that would be beneficial to the RNA modifications community include computational and database needs, which are described in detail in Chapters 3 and 4. Additionally, the committee acknowledges that the types of facilities needed today might not be the same as what will be needed in 10 years, as the field continually evolves and expands. As discussed in Chapter 3, the field will benefit from core RNA sequencing facilities that offer expertise, techniques, and methods that span the different sequencing approaches (e.g., global modification

___________________

14 See https://www.citizenscience.gov (accessed October 27, 2023).

mapping, direct and indirect sequencing), as well as the computational and bioinformatics expertise needed to analyze and interpret the data.

DNA Sequencing Core Facilities

For many years, companies have offered DNA sequencing services using a fee-for-service model and, typically, stringent sample requirements. These services offer many laboratories the opportunity to sequence DNA samples quickly and cheaply.

However, high-throughput DNA sequencing instruments are increasingly housed onsite at universities and companies, typically in a core facility. These facilities include highly trained staff skilled in operating different types of next-generation sequencing instruments and in data management and computational analysis of sequencing output. A major advantage of onsite sequencing facilities is that they allow researchers and developers to consult and collaborate directly with facility staff to address challenges, an arrangement that is not necessarily possible when working with fee-for-service companies. In that sense, facility staff also serve as internal experts who can help troubleshoot and solve problems related to experimentation.

Although specific methodologies related to RNA modifications are lacking in some core facilities, third-generation sequencing technologies, such as those of Oxford Nanopore Technologies, are available. As methodologies for sequencing RNA modifications become available, core facilities that house the necessary instruments and staff expertise will become increasingly valuable.

Centralized Research Facilities for Global Analysis and Modification Mapping by Mass Spectrometry

While this report has noted the value and utility of mass spectrometry–based approaches for the sequencing of modified RNAs, this instrumental platform can be costly to obtain and maintain and typically requires skilled operators. These factors can lead to inequities as academic researchers at smaller colleges or universities lack on-campus access to such instrumentation. Similarly, the cost and technical requirements can be a barrier for start-ups and other small companies that wish to move into this area.

Currently, centralized facilities and resources that serve a broader constituency are available, which could serve as a model for future facilities for RNA modification sequencing. For example, NIH-funded centers that have a significant or sole focus on mass spectrometry–based analyses include Biomedical Mass Spectrometry at Washington University in St. Louis,15 the Proteomics Center for the MoTrPAC at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (operated by Battelle),16 and the Metabolomics and Clinical Assay Center at the University of North Carolina.17 One particularly relevant example of a successful center in this mode is the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center at the University of Georgia, which has provided mass spectrometry resources and services for glycomics and glycobiology for nearly 40 years (CCRC, n.d.). Establishing one or more such facilities would significantly improve access to modern mass spectrometry for RNA, catalyze the establishment of unified protocols for the global analysis of RNA modifications, and spur future technological developments. Such facilities could be jointly supported by industry partners, enabling precompetitive technology developments that benefit all who have an interest in the characterization of modified RNAs (biological or therapeutic).

___________________

15 See https://www.mtac.wustl.edu/ (accessed October 27, 2023).

16 MoTrPAC stands for the Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity Consortium; see https://www.emsl.pnnl.gov/project/50105 (accessed October 27, 2023).

17 See https://uncnri.org/2022/01/27/north-carolina-research-campus-team-receives-major-nih-award-for-precision-nutrition-research/ (accessed October 27, 2023).

To illustrate how such an RNA-centric resource could be organized and managed, Mark Helm, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, shared in a presentation to the committee (see Appendix C) that the RMaP program has a dedicated research core that provides services, resources, and unified protocols for RNA modification discoveries to benefit the research community. Additionally, dedicated financial support for this centralized facility enables training of students and postdoctoral researchers in relevant methods and technologies.

Beyond the need for centralized U.S.-based resources in this area, more academic- and industry-based mass spectrometry facilities that offer capabilities for conducting global analysis of RNA modifications would provide several opportunities. For example, RNA-centric facilities may be the natural vehicle to provide training, workshops, and short courses and to create training tools and reference sample sets for RNA sequencing and modifications.

Readily Available High-Quality Reagents and Research Standards

Coordinating and aligning collaborative but decentralized research programs requires, among other things, the development of standard materials and practices (see Chapter 4). Access to common, fit-for-purpose physical materials and reagents, as well as analytical technology and supporting protocols, would help facilitate this process. Standardized kits and platform components have proven to be very helpful in related endeavors and likely would be with the procedures needed for RNA modification analysis. Therefore, vendors and suppliers of reagents and other materials with a robust and reliable supply chain are essential to address the growing needs of the field. Gaps in this area are not due to technical constraints but exist in large part because of perceived lack of market opportunity.

Advancing this enterprise depends upon a robust, resilient, fit-for-purpose supply of materials. For example, commercially available purification tools and kits specifically for end-to-end sequencing and modification mapping of RNAs, including at the single-cell or single-molecule levels, need to be developed. RNA isolation and purification kits that are available for more generalized applications may result in experimental artifacts. As noted in Chapter 4, modifications on human mRNAs reported in publications often are derived from samples that are contaminated with other RNAs or RNA degradation products. Purification kits that enable isolation of RNAs based on type or size, that are easy to use, compatible with indirect or direct sequencing approaches, and enable high-sensitivity analyses without sample degradation or loss would accelerate work in this field. For example, direct sequencing via mass spectrometry typically requires far more RNA than is actually consumed or analyzed by the instrument itself. Of note here, whether used in global analysis of modified nucleosides or used in RNA modification mapping by the bottom-up technique (see Chapter 3), the initial RNA sample must be digested and then separated, often chromatographically.

Supportive Policy Environment

Policies can play an important role in accelerating innovation. The committee considered recent federal legislation and related policies that support investment in the bioeconomy18 as a national interest. The development of innovative tools and technologies to support sequencing and mapping of epitranscriptomes holds promise for downstream applications of this knowledge in improving human health and advancing the bioeconomy across its other sectors.

___________________

18 The bioeconomy is “the economic activity derived from biotechnology and biomanufacturing” (White House, 2022, para. 3).

The most salient legislation is the CHIPs and Science Act, signed into law on August 9, 2022.19 Title IV, “Bioeconomy Research and Development,” called on the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to implement a National Engineering Biology Research and Development Initiative, with the overarching goal of advancing “societal well-being, national security, sustainability, and economic productivity and competitiveness . . . through funding areas of research at the intersection of the biological, physical, chemical, data, and computational and information sciences and engineering” (U.S. Congress, 2022, sec. 10402). Notably, the act mentioned “sustained support for databases and related tools, including curated genomics, epigenomics, and other relevant omics databases,” including plants, animals, and microbes, and related standards and workforce development. A separate section of the act focused on broadening participation in science. Because epitranscriptomics crosses several disciplines listed in the legislation and will require sustained support of data resources, this policy aligns with the goals of this report.

On September 12, 2022, the White House issued Executive Order 14081, “Advancing Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing Innovation for a Sustainable, Safe, and Secure American Bioeconomy” (White House, 2022). The order tasked a range of federal agencies—including NSF, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)—to submit reports identifying high-priority basic research and technology development needs and opportunities for public–private collaboration. The order directed the preparation of a separate report on workforce.

Agency priorities have since been published in a single document, Bold Goals for U.S. Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing, released in March 2023 (White House, 2023a). A summary of selected priorities and goals of three agencies, NSF, HHS, and USDA, applicable in supporting investments and prioritizing development of technology and infrastructure for sequencing of epitranscriptomes as part of the bioeconomy follow.

NSF set a goal to expand capabilities to build and measure the performance and quality of biological systems, including “to enable the construction and measurement of any single cell within 30 days” through the capability to read and write any genome, epigenome, transcriptome, and expressed proteome (White House, 2023a, p. 51). Related research and development needs to achieve the goal include advanced technologies for characterizing and manipulating biological systems and biomolecules. NSF also addressed the need for public engagement and educational and training pathways to broaden participation and ensure that diverse perspectives are included in research and development to support the bioeconomy. The separate workforce report, Building the Bioworkforce of the Future, released in June 2023, presented steps that can be taken to diversify and expand the STEM-proficient workforce (White House, 2023b). These steps align with the findings of the committee laid out in this chapter.

Similarly, HHS stated priorities that include establishing a pipeline for precision multi-omic medicine and biomanufacturing of cell-based therapies. A related goal is the ability, in 20 years, to generate a multi-ome for $1,000. Related research and development needs include “driving down costs through targeted investment in novel high-throughput technologies … with emphasis on enabling multi-omics characterization with spatial resolution throughout tissues” (White House, 2023a, p. 42).

The USDA goals include increasing agricultural productivity by 28 percent in 10 years. Related research and development needs include research on improving resistance to pests and pathogens and protecting plants and animals against other environmental stressors, and more broadly supporting “plant and animal breeding infrastructure to identify beneficial genes, pathways, and regulatory controls that perform in varying production environments” (White House, 2023a, p. 22). As

___________________

19 CHIPS and Science Act, Pub. L. 117-167 (August 9, 2022). CHIPS stands for Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors.

described in Chapter 2, RNA modifications in plants and animals have important implications in health and disease.

In addition, the Bold Goals report discussed several existing public–private partnerships that can either be expanded or serve as models for new efforts. Manufacturing USA, previously known as the National Network for Manufacturing Innovation, is a network of research institutes that encourages innovation in technologies addressing current and emerging manufacturing needs, facilitates deployment of these technologies in domestic manufacturing, and supports development of workforces. These manufacturing innovation institutes (MIIs) are organized as public–private partnerships in specific technical areas and provide a preexisting construct for anticipating, accelerating, and enabling these emerging technologies prospectively. The National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Biopharmaceuticals (NIIMBL) is one important example of an MII. Manufacturing USA is operated by the interagency Advanced Manufacturing National Program Office, headquartered at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in DOC.

Other existing public–private partnerships include NSF’s Industry-University Cooperative Research Centers program,20 which focuses on precompetitive research and development. The Accelerating Medicines Partnership® program involves NIH, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, and multiple public and private organizations, including biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies. Private-sector partners play a role in governance and in stimulating private investment. Another example, postdating the Bold Goals report, is a significant ($82 million) award from FDA to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for a 3-year research program to develop a fully integrated, continuous mRNA manufacturing platform. MIT’s collaborators are The Pennsylvania State University, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and ReciBioPharm, the biologics division of a large contract and development manufacturing organization.21

Executive Order 14081 also directed attention to regulatory barriers to innovation and called for steps to address them. The President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) (2022) considered this set of concerns in a subsequent report on biomanufacturing for the bioeconomy, in which it identified three key gaps or challenges facing the United States: “insufficient manufacturing capacity, regulatory uncertainty, and an outdated national strategy” (p. 2). PCAST recommended that the heads of the agencies establish a standing rapid-response team to evaluate new, cross-cutting projects and provide recommended regulatory routes, develop streamlined and model pathways for various types of novel bioproducts, and establish a training and information network that places regulatory scientists with centers, such as those created through NIIMBL.

The information gathered by the committee through a public workshop, consultation with a range of vested parties, and commissioned papers confirmed the experience of committee members: regulatory policy is not significantly impacting the conduct of basic research on RNA modifications at present. At the same time, the sequencing and mapping of epitranscriptomes will require a mobilization of resources. It is important to recognize the alignment between the science and technology that is the focus of this report and the goals described above, and it will be essential to leverage opportunities presented by the current policy environment.

A LARGE-SCALE RESEARCH INITIATIVE

In considering possible approaches to organizing and managing projects related to sequencing of RNA and its modifications, the committee sought to understand and learn from past large-scale

___________________

20 See https://iucrc.nsf.gov/ (accessed October 4, 2023).

21 See https://news.mit.edu/2023/mit-researchers-lead-new-center-mrna-manufacturing-0713 (accessed November 6, 2023).

efforts in the life sciences. The Human Genome Project (HGP) was a first-of-its-kind, international-scale science project devoted to the field of biology (NRC, 1988). The goal of sequencing and mapping epitranscriptomes shares some parallels with the history of the HGP (Box 5-1). For example, at the time of its conception, technologies for high-throughput DNA sequencing were in early stages of development, the scientific community was actively debating the scope of the questions, and there was no clear path to organizing or funding such a large-scale endeavor. Appreciating the history of the development of the HGP and its eventual impacts on science and society reveals some of the similar potential that exists with mapping and sequencing RNA modifications.

Inspired by the success of the HGP, the United States has led several other large-scale efforts in the life sciences. While each large-scale scientific initiative is in some respects sui generis, there are common elements regarding decisions about organization and management of a large-scale bioscience project, including federal interagency and international coordination, progression of tool and technology development vis-à-vis other goals, and the relationship between the public and private sectors.

Federal Interagency and International Coordination

All large-scale projects require authorized oversight bodies to facilitate coordination and integration of efforts. For example, the NIH-funded Glycoscience Program included a glycoscience-focused interagency steering committee with representation from NIH, FDA, NIST, NSF, and DOE, as described to the committee during an open session with Pamela Marino (Marino, 2023). That program was built upon a preexisting consortium, the Consortium for Functional Glycomics, funded by NIH. Similarly, the U.S. Human Microbiome Project established a Trans-NIH Microbiome Working Group to coordinate extramural research activities related to the human microbiome (NIH, 2012).

The HGP was a joint effort involving international collaborations and formal coordination (Birney, 2021; NHGRI, n.d.). It illustrated the potential for U.S. leadership and willingness to invest resources to catalyze productive international partnerships, as well as the power of building on preexisting relationships within the research community. Some recent large-scale initiatives in the life sciences that have been launched with support from the U.S. federal government have not formally and comprehensively integrated international partners from conception. Rather, they have included consortia open to any enterprise or researcher with shared goals and commitments wherever located, encompassed international collaboration in specific areas of common interest, and/or evolved to include more formal international cooperation over time. For example, multiple countries have launched independent initiatives focused on neuroscience: the U.S. Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative, the European Union Human Brain Project, and similar initiatives funded by Australia, Canada, China, Israel, Japan, and Korea (IBI, 2018; IBT, 2019; Yuste, 2017). Various mechanisms have been created to support cross-fertilization, such as the International Brain Initiative guided by leaders of the national initiatives, and the International Neuroinformatics Coordinating Facility for the development and adoption of shared data standards (Abrams et al., 2022; IBI, 2020; The Lancet Neurology, 2021). The evolution of Glygen, an integral component of the Glycoscience Program, offers another example. Glygen is a part of the international GlySpace Alliance, which is focused on ensuring data integrity, increasing accessibility, and integrating and harmonizing global glycoscience data into a single resource (Lisacek et al., 2023).

BOX 5-1

Comparing the Human Genome Project with Possible Efforts Related to RNA Modifications

Long before the launch of the Human Genome Project (HGP) in 1990, the concept of a gene as an inheritable molecular unit giving rise to phenotypic traits was a known concept of genetics. In addition, there was an understanding that genes are encoded in the DNA genomes of organisms, transcribed into messenger RNA, and then translated into proteins (Brenner, Jacob, and Meselson, 1961; Gros et al., 1961; Jacob and Monod, 1961). The development of the field of molecular biology, devoted to understanding these processes and the structure and mechanisms of the molecular machines that implement them, led to the sequencing of several genes, establishing a link between DNA sequence and the function of proteins in living systems. This gave rise to two key questions in biology: where are all the genes in a genome, and what are their sequences?

Addressing these questions, especially pertaining to the human genome, would require an enormous undertaking on a scale not previously seen in the biological sciences. The idea of a centralized top-down effort to carry out a large-scale project was new to the field of biology. It was inspired by the large, concerted efforts that astronomers and physicists had successfully orchestrated to build such resources as observatories and particle accelerators (Cook-Deegan, 1996). However, there was lack of consensus about the merits of a top-down approach in biology. The path to a coordinated, structured, and funded HGP was complex, taking many years to reach scientific consensus on defining the problem, community consensus on how to carry out the effort, and political consensus as to how to fund such a large undertaking and who should be in charge.

In terms of science, an important distinction was made between mapping—or locating where the genes are within a genome—and sequencing—putting the genes in physical order and eventually determining the DNA nucleotide sequences that define the gene. Prior to the 1980s, the concept of finding restriction fragment length polymorphism markers in a genome was an emerging technique to map genes onto sections of a genome (Botstein et al., 1980). The advent of DNA cloning created the possibility of establishing collections of clones of these sections to make mapping a high-throughput endeavor. The creation of genome fragment clones also created the possibility of using these materials to sequence the DNA within these fragments. However, in the 1980s high-throughput DNA sequencing technologies had only been conceptualized, with many technical developments still required before they were ready to be applied to something at the scale of the human genome. As a result, there were two main camps of scientists: one favoring devoting resources to large-scale and higher-resolution mapping efforts and the other advocating for sequencing the 3 billion base pairs of the human genome.

While the scientific debate was ongoing, there were also discussions and debate as to who would lead and fund such a project. While early plans explored using philanthropy to create private genome centers (IOM, 1991), plans also emerged organically within the Department of Energy (DOE), whose interest aligned with the concept of the HGP because of its connection to radiation biology and its need for the large-scale scientific infrastructure for which DOE is known. Similarly, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) developed its own internal interest in pursuing human genome research.

In 1987, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) commissioned a consensus study titled Mapping and Sequencing the Human Genome, with a committee that included many leading scientists who had developed the various concepts of the HGP (NRC, 1988). By design, the members of the committee consisted of experts with diverse perspectives for balance and included both skeptics and proponents of “Big Biology” as they called it (Cook-Deegan, 2023). The report laid out the goals and recommendations for a large-scale national effort, led by an unspecified federal agency that would work closely with a scientific advisory board (NRC, 1988). In 1990 Congress appropriated the funds to support the project, which was to be led by NIH and DOE.

In addition to recommending a framework for implementing a large-scale research effort, the NAS consensus report provided a roadmap for implementation. The report favored an initial focus on large-scale and higher-resolution mapping efforts, with sequencing the 3 billion base pairs of the human genome as the ultimate goal and with the technologies to do so. It also recommended a focus on technology development by both expanding on nascent sequencing technologies, developing the necessary molecular biology techniques, and creating databases and the supporting computational infrastructure to house all the generated data. The report also highlighted the value of using genome structure to determine gene function, and mapping and sequencing the genomes of model organisms. The report estimated that the HGP would cost $200 million per year for 15 years, a $3 billion budget that turned out to be remarkably accurate (NRC, 1988). a

Sequencing for the public HGP effort was carried out by the coordinated action of distributed genome centers, including the DOE Joint Genome Institute, Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Washington University School of Medicine Genome Sequencing

Center, and Whitehead Institute/Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Genome Research. Many other genome sequencing centers internationally made critical contributions to the effort, including facilities in Australia, People’s Republic of China, United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Japan. While the technologies for automated DNA sequencing continued to improve, there were challenges with their efficient deployment and coordination of operation and information exchange. At the same time, a large-scale commercial effort to sequence the human genome, led by Craig Venter and Celera Genomics, emerged to compete with the public project (DOE, n.d.). The private and public effort culminated in a brokered tie by President Bill Clinton in 2000 with simultaneous publication of the first draft human genome sequences in Science (Venter et al., 2001) and Nature (Lander et al., 2001), respectively.

The HGP established a framework for the scientific, administrative, political, and funding infrastructure to carry out national- and international-scale biological projects. Beyond that, it created a reference sequence of the human genome, which has been used to increase understanding of the molecular basis of disease and facilitated developing treatments. The HGP also revealed additional complexity to human biology, raising more questions than it answered about how the DNA genome encodes the instructions of life. This motivated follow-on, national-scale biology projects, such as the creation of the ENCODE (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) Consortium, which aimed to uncover additional layers of instructions within the DNA genome and how epigenetic modifications alter the information content of the genome. b

The completion of the first human genome sequences also drove a new quest for personalized medicine, where the goal posts shifted to innovating sequencing technology at a scale where everyone’s genome could be sequenced quickly and at a relatively low cost (Check Hayden, 2014; National Research Council, 2011). This gave rise to new companies, such as 23andMe, that collect individuals’ genomic information and provide services such as family-lineage tracing and disease prognostication. The popularity of these direct-to-consumer services served as additional drivers to improve the technology and scale it for widespread use. This commodification of sequencing extended the use of genome sequencing tools to other types of biological measurements, including the development of RNA sequencing, which allows scientists to catalog all of the different RNA forms in cells and tissues, adding to an understanding of how DNA genome information manifests in cellular function.

These DNA sequencing improvements ultimately gave rise to DNA synthesis technologies that together are driving new approaches to engineering biological systems to solve global challenges, to create a whole new sustainable bioeconomy. The general economic return on U.S. government investment in research and development is estimated to be in the range of $2.50–3.00 for every public dollar spent. In another study, estimates for the economic return for the HGP, which had a transformative impact across a number of sectors, are as high as $178 for every public dollar spent (Wadman, 2013). In 2011, a report estimated that between 1988 and 2010, the HGP had an economic impact of almost $800 billion (Tripp and Grueber, 2011). A more recent study focusing on human genetics and genomics research reported that in 2019 alone, the economic impact totaled $265 billion and generated over $5 billion in federal tax revenue (Tripp and Grueber, 2021).

The HGP provides many lessons for developing and implementing a project to map and sequence any epitranscriptome, including requiring a large-scale, coordinated scientific effort; necessitating similar technological, administrative, and funding infrastructure; and demanding similar political and public support. A large-scale epitranscriptome mapping and sequencing project may also be expected to have similar impacts to the HGP’s, by driving the development of new and innovative technologies that can be adapted to broad applications. Scientifically understanding the structural complexities of epitranscriptomes will lead to a new understanding of basic biology and disease, which will in turn lead to new biotechnologies that treat diseases.

However, the differences between sequencing the human genome and sequencing epitranscriptomes need to be considered from a technical viewpoint. Unlike the DNA genome, which is largely fixed within an individual, outside of the mutation and repair processes that occur over a lifetime, RNA modifications are much more dynamic (see Chapter 1). RNAs themselves are transient cellular species, synthesized in response to developmental and environmental cues that can then act to regulate their own synthesis and processing.

Modifications alter the structure and function of RNAs in dynamic ways and are highly context dependent. Therefore, any epitranscriptome would represent only one snapshot in time and vary for different cell types and conditions. Of course, while the sequencing of select epitranscriptomes under defined conditions can drive technology development and innovation, the ultimate task is to foster the technology to enable sequencing of any epitranscriptome for any organism or cell type, under defined conditions. The scientific community has agency to decide when and where to apply these new technologies to address important scientific questions. It will then take massive coordination and data-sharing efforts to learn from these data collectively.

__________________

a Actual U.S. costs for the HGP are estimated at $2.7 billion over ~13 years, and include the wide range of scientific activities that fell under the project umbrella. See https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/Sequencing-Human-Genome-cost.

b See https://www.encodeproject.org/ (accessed October 12, 2023).

Tool and Technology Development