Charting a Future for Sequencing RNA and Its Modifications: A New Era for Biology and Medicine (2024)

Chapter: Appendix F: Ideation Challenge Commissioned Papers

Appendix F

Ideation Challenge Commissioned Papers1

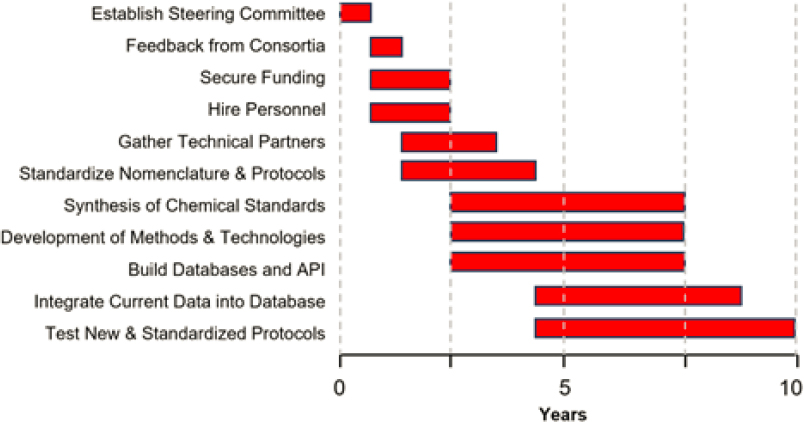

On June 12–13, 2023, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine hosted an “Ideation Challenge” event to generate innovative approaches to solve pressing challenges in epitranscriptomics. Thirty participants from the RNA biology community formed interdisciplinary teams, identified a challenge, and discussed solving these challenges through guided sessions of collaborative brainstorming, problem solving, and providing feedback between groups. Each team recorded a video explaining their concept; these are available to view on the event website.2 A two-page written description of each concept was shared with the study committee and three teams were asked to submit white papers (see below) to describe their concepts in further detail. The commissioned papers produced by the teams guided the study committee in various aspects of the report writing process.

THE IMPACT OF RNA MODIFICATIONS ON CELLULAR FUNCTION VIA ALTERATIONS TO STRUCTURE AND MACROMOLECULAR INTERACTIONS

Author List3

Ulf Andersson Vang Ørom, Aarhus University

Nikos Tapinos, Brown University

Matthew G. Blango, Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology: Hans Knöll Institute

Jennifer Strasburger, National Human Genome Research Institute

Mark Adams, The Jackson Laboratory

___________________

1 The authors are solely responsible for the content of this paper, which does not necessarily represent the views of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

2 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/06-12-2023/toward-sequencing-and-mapping-of-rna-modifications-ideation-challenge#sl-three-columns-ac57cecc-6691-4a03-8c4a-8dc03526113b.

3 All authors contributed equally to this work.

Challenge

RNA structure and RNA modifications are aspects central to RNA function. They have both been widely recognized for decades to be important for regulatory RNAs such as transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA), where the structure of RNA is relatively well characterized. When looking at messenger RNA (mRNA) and noncoding RNA, a much less complete picture emerges, where RNA structure is often neglected and the importance of RNA modifications is just starting to emerge (Assmann, Chou, and Bevilacqua, 2023; Zhang et al., 2022). Basic RNA structure is often depicted as a linear strand of nucleotides, sometimes with a hairpin to illustrate some degree of structure. A recent perspective article (Vicens and Kieft, 2022) very accurately highlighted the need for progression of the RNA community, as well as for the entire scientific community, towards appreciating the complexity of RNA tertiary structure; the three-dimensional arrangement of RNA building blocks that includes helical duplexes and triple-stranded structures; and the importance of structure for the molecular functions of RNA, including mRNA.

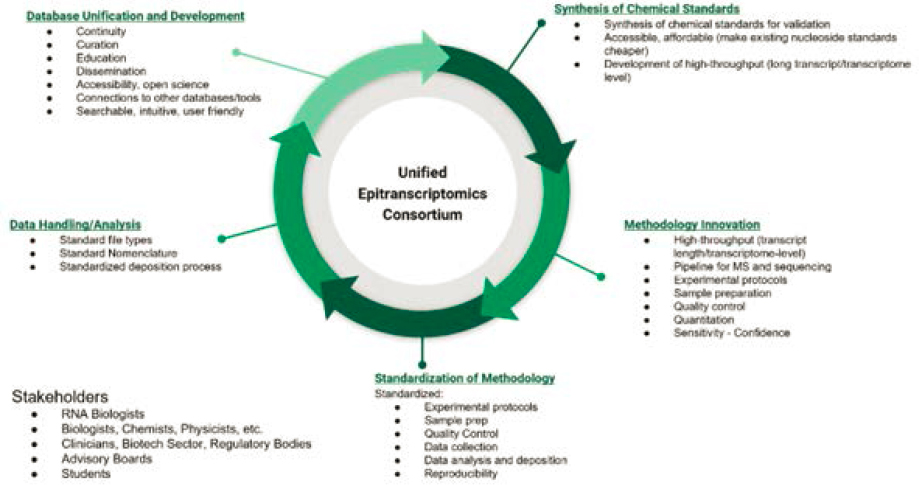

In this paper, we challenge the community to take on an ambitious effort to understand RNA structure on a transcriptome-wide level to gain new insights into the dynamics of RNA and its interaction with other macromolecules (e.g., DNA, RNA, and proteins [Figure F-1]). We emphasize the need to develop more high-throughput tools for identification of the RNA modifications currently known to occur on mRNAs in order to obtain nucleotide-precision and cell-state–dependent mapping of each modification of the transcriptome. Tools such as chemical and enzymatic conversion of specific RNA modifications and stronger direct RNA sequencing analysis pipelines are needed to meet this goal. In addition, a coordinated effort by the community to align data standards and data processing to a uniform format will be essential for driving this ambitious effort forward. RNA modifications and their impact on mRNA structure can then be assessed for their ability to mediate RNA–protein interactions (as well as interactions with RNA and DNA) with experimental and computational approaches. We encourage the community to incorporate these data into a global model that can predict RNA structure and mRNA–protein interactions and assess how these are affected by differential RNA modifications. We anticipate an “AlphaFold for RNA,” which will enlighten research into functional RNA elements, the importance of RNA modifications on basic mRNA function, and the dynamics of mRNA structure and function within the cell.

SOURCE: Created with Biorender.com.

State of the Art

The diversity of RNA modifications is demonstrated by reported functions for a diverse subset of the roughly 170 known modifications (Zhang et al., 2023), including N6-methyladenosine (m6A), N6, 2′-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am), 5-methylcytosine (m5C), 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, inosine (I), pseudouridine (Ψ), N1-methyladenosine (m1A), 2′-O-methylation (Nm), N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C), N7-methylguanosine (m7G), dihydrouridine (D), and many others (Zhang, Lu, and Li, 2022). Different chemical modifications play distinct regulatory roles. The m6A modification influences RNA stability, splicing, translation, localization, and RNA secondary structure (Barbieri and Kouzarides, 2020; Delaunay and Frye, 2019; Shi, Wei, and He, 2019; Yang et al., 2018). Other modifications such as m5C play a role in regulating stability and translation of mRNA, while m5C regulates fidelity of translation and stability of tRNA structure (Blanco et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2019; Shanmugam et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2019; Zhang, Lu, and Li, 2022). Inosine is mainly found in double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and plays a role in codon recoding, microRNA biogenesis, and alternative splicing site selection (Gerber and Keller, 1999; Seeburg and Hartner, 2003; Wulff, Sakurai, and Nishikura, 2011). Other modifications such as pseudouridine (Ψ) play a role in folding of rRNA, stabilize tRNA structure, and regulate biogenesis of small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) (Arnez and Steitz, 1994; Davis, 1995; Decatur and Fournier, 2002; Jack et al., 2011; Karijolich, Yi and Yu, 2015; Karikó et al., 2008; King et al., 2003; Liang, Liu, and Fournier, 2007; Newby and Greenbaum, 2002). Introducing Ψ into mRNA results in increased protein production and alterations in the rate of translation (Eyler et al., 2019; Karijolich and Yu, 2011; Karikó et al., 2008). m1A is critical for stabilizing the tertiary structure of tRNA, while in mRNA it affects translation (Dominissini et al., 2016; Helm et al., 1998; Li, 2017; Saikia et al., 2010; Schevitz et al.,1979; Voigts-Hoffman et al., 2007). Nm plays a critical role in protein synthesis, while internal m7G has a dual role in regulating translation efficiency and enhancing micro RNA biogenesis (Choi et al., 2018; Elliot et al., 2019; Hoernes et al., 2016, 2019; Pandolfini et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Finally, ac4C induces translation of mRNA and affects biogenesis of rRNA (Arango et al., 2018; Dominissini and Rechavi, 2018; Ito et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2020; Kumbhar, Kamble, and Sonawane, 2013).

Additional features of RNA modifications have been observed for mRNA. In addition to the presence or absence of an RNA modification, the percentage of a particular transcript that is modified plays a significant role on the functional consequences of the RNA modification. For example, a modification that leads to mRNA decay is unlikely to have a significant biological effect if it affects only a small percentage of the transcriptome. Since modifications can affect mRNA structure and/or the recruitment of RNA-binding proteins, modifications of a fraction of the transcripts at any specific site would generate two distinct mRNA species that differ in their structures and protein-binding partners. Hence, changing the stoichiometry of modifications may offer another approach to generate functional diversity of mRNA.

While current RNA modification profiling methods can map the modification locations, they do not quantify the relative fraction of modified and unmodified RNA for a given transcript or phase modifications along a single RNA strand. High-throughput methods for site-specific quantification of all RNA modifications and determination of the stoichiometry of modifications will considerably advance our understanding of the functional roles of RNA modifications.

Existing Technologies—Deficiencies

Quantification of global levels of RNA modifications. Several methods for quantifying RNA modifications are already in wide use. These include dot blot assays, two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography (2D-TLC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and liquid

chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS)–based approaches, among others (Zhang, Lu, and Li, 2022). These approaches can be used to quantify the modification abundance in specific RNA species. However, they require significant amounts of RNA, which limits their utility for rare or difficult-to-acquire samples. This is especially true in the case of 2D-TLC and LC-MS, which require dedicated and expensive equipment not readily available in most laboratories around the world.

Methods for obtaining positional information of RNA modifications. Various methods have been developed for determining and quantifying the precise position of RNA modifications (Zhang, Lu, and Li, 2022).

- Primer extension. The principle of this technology is that a reverse transcriptase (RT) only reaches the 5’-end of RNA to produce a full-length complementary DNA (cDNA) if certain RNA modifications are not encountered. In the presence of modifications such as m1A, Ψ, and N1-methylguanosine, RT extension is blocked upstream of the modified site. The resulting cDNA products can then be separated by polyacrylamide gel and the terminal position of the truncated cDNA determines the position of the RNA modification. Although very sensitive, this approach has major limitations. Unfortunately, prior knowledge of the type of modification and sequence of the target RNA are required. Also, the technology can only be used for modifications that block reverse transcription and cannot be applied to “silent” modifications like m6A or m5C.

- qPCR-based approach. Semiquantitative PCR or quantitative (q)PCR–based approaches depend on the property of modified nucleotides to impede the extension of reverse transcriptase. A number of methods have been established based on these technologies to successfully detect modifications such as Nm, Ψ, N6-isopentenyladenosine, and m6A in diverse RNA species (Aschenbrenner and Marx, 2016; Castellanos-Rubio et al., 2019; Dong et al., 2012; Harcourt et al., 2013; Khalique, Mattijssen, and Maraia, 2022; Wang et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2018; Zhang, Lu, and Li, 2022). The use of qPCR approaches has been accelerated by the development of RT enzymes that facilitate modified nucleotide detection. As one example, an engineered variant of the thermostable KlenTaq DNA polymerase harbors reverse-transcription activity and can also discriminate Nm at normal concentrations of deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Aschenbrenner and Marx, 2016; Zhang, Lu, and Li, 2022). The DNA polymerases Tth and Bst also exhibit reverse transcriptase activity and can be leveraged for locus-specific detection of m6A based on their distinct extension capabilities when encountering m6A versus A residues (Castellanos-Rubio et al., 2019; Harcourt et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2016; Zhang, Lu, and Li, 2022).

- RNase H approach. In this method, RNase H cleaves RNA into two halves at the 5′ end of the nucleotide of interest (Zhang, Lu, and Li, 2022). To achieve specificity of cleavage, a 2′-O-methyl RNA–DNA chimeric oligonucleotide is annealed to RNA. Following purification of the 3′-half of the RNA, the 5′ terminus is labeled with phosphorus-32 (32P). Finally, thin-layer chromatography is used to resolve single nucleotides after complete digestion of the 32P labeled oligonucleotides. The major limitations of this method are that it requires advanced knowledge of the sequence of interest, hazardous radioactive reagents, and specialized analytical instruments and procedures.

- Electrospray Ionization-Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS) approach. In this method, endoribonucleases such as RNase A, RNase T1, and RNase U2 are used to digest RNA into 5–15 nucleotide fragments, which are then separated by HPLC into sequence ladders. ESI-MS is then applied to reconstruct the sequence and identify RNA modifications. The major limitation of this method is the cost of the ESI-MS and the specific expertise required for running this equipment. Another limitation is the requirement of large quantities of RNA, which makes this technique not suitable for rare RNA species or precious samples.

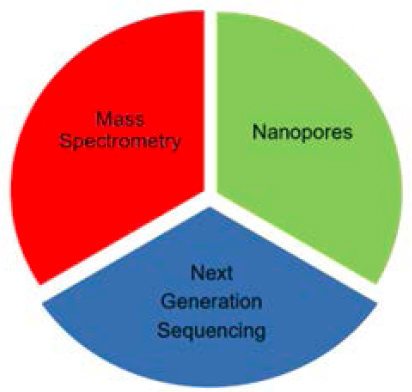

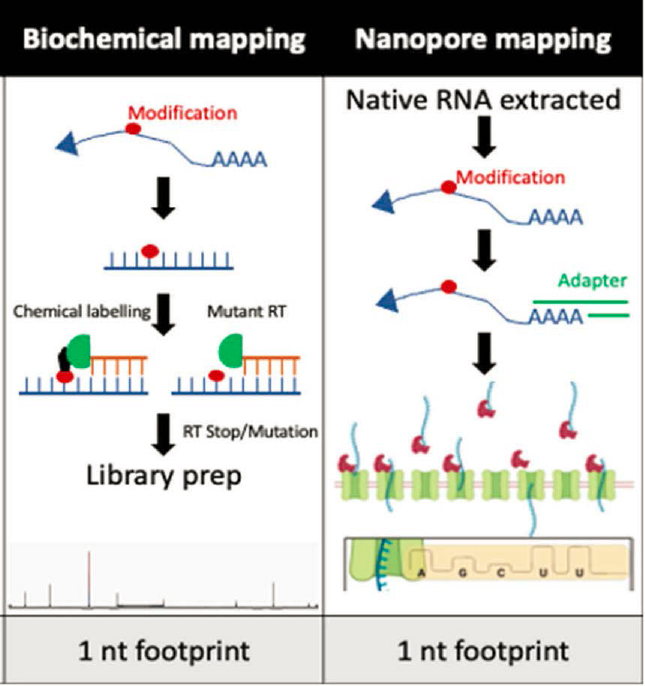

Next-generation sequencing methods. Several next-generation sequencing (NGS) methods have been developed for mapping RNA transcriptome-wide modifications. The methods can be divided into chemical-assisted sequencing technologies, antibody-based (immunoprecipitation) technologies, enzyme- or protein-assisted technologies, and direct sequencing technologies. Examples of these technologies validated by published methods are described below.

- Chemical-assisted sequencing. Multiple new methods are under development that can discriminate modified nucleotides from unmodified nucleotides (Zhang, Lu, and Li, 2022). So far, these approaches typically rely on the use of (1) biotin tags to enrich modified transcripts prior to sequencing; (2) altered features of base-pairing to induce misincorporation or truncation during the reverse-transcription reaction; or (3) chemical-induced cleavage, which is followed by specific adaptor ligation. More recently, an approach termed GLORI was developed that uses glyoxal and nitrite-mediated deamination of unmethylated adenosines and enables accurate and quantitative determination of m6A sites (Liu et al., 2023).

- Antibody-based technologies. This method uses antibodies specific for modifications such as m6A or m7G to immunoprecipitate modified RNA, followed by fractionation and NGS (Zhang, Lu, and Li, 2022).

- Enzyme- or protein-assisted sequencing. DART-seq uses the cytidine deaminase APOBEC1 fused to the m6A-binding YTH domain to deaminate nucleotides next to m6A-modified nucleotides (Meyer, 2019). This technology has also been used at single-cell resolution. The E. coli endoribonuclease MazF cleaves an unmethylated 5′-ACA-3′motif, but not the 5′-m6ACA-3′ motif, when followed by NGS. This method can map the presence of m6A at single-nucleotide resolution (MAZTER-seq and m6A-REF-seq) within a subset of m6A sites. The related evolved TadA-assisted N6-methyladenosine sequencing (eTAM-seq) approach relies on an optimized bacterial deaminase specific for unmodified A bases and was shown to enable m6A profiling, including from very limited RNA input amounts (Xiao et al., 2023).

- Direct RNA sequencing. Several approaches have been described using nanopore direct RNA sequencing technology coupled with artificial intelligence (AI)–based data analysis and modification identification (Cozzuto et al., 2023; Mulroney et al., 2023; Pratanwanich et al., 2021; Stephenson et al., 2022). Nanopore sequencing has also been used to detect pseudouridine semiquantitatively (Tavakoli et al., 2023). This analysis was facilitated by construction of hybrid synthetic RNA templates with base modifications at specific locations. An engineered nanopore structure with a reactive site was shown to be able to discriminate among 14 different nucleotide monophosphates containing known RNA modifications, showing that highly accurate detection of modified bases is feasible, although this system is not yet configured for sequencing of RNA strands (Wang et al., 2022).

The NGS approaches have expanded over the last couple of years at the bulk mRNA level. Major limitations are the absence of efficient and widely applicable methods for single-cell modification sequencing, as well as the limited expansion of NGS technology on modifications of other RNA species (e.g., rRNA, tRNA, circular RNA). Finally, the AI algorithms for nanopore technology and the resolution and noise deconvolution methods for using nanopore for modification-sequence mapping still need refinement, as they can only be applied for a few of the known modifications.

Short-Term Goals

There are important technological components that must be included in any plan for studying RNA modifications. These include additional investments in sequencing methods using a diversity

of approaches, the availability of standard materials for benchmarking, standard operating procedures, and appropriately organized repositories for data. However, additional near-term, foundational tasks must also be undertaken to progress to long-term goals. These tasks are as follows:

- Create affordable, reliable benchmarking materials that are widely available and coupled to accepted community standards for data analysis downstream.

- Develop easy, affordable, and accessible techniques for quantifying modifications such as m6A and the other known mRNA modifications.

- Mine microbial systems for novel enzyme potential.

- Develop libraries of enzymes for modification-specific reactions: a reverse transcriptase for each modification, endonucleases (toxin/antitoxin) to facilitate single-molecule labeling, and/or RNA-targeting CRISPR/Cas systems.

- Explore methodologies for structural assessment of modified RNAs (e.g., cross-linking and immunoprecipitation [CLIP]-seq and selective 2’-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension and variant profiling [SHAPE-MaP] approaches for modified RNAs).

Proposed methods for addressing our short-term goals:

- Quantification of global levels of RNA modifications. To address our goal of creating fast, reliable detection of RNA modifications, we need to develop easy, highly quantitative, reproducible, affordable, and expandable methods. Our proposal would be to start with methods for globally quantifying a single, abundant modification such as m6A on mRNA, and then expand to other modifications as technology and community standards mature. For an easy, quantitative, and affordable method of quantifying m6A on mRNA, we believe that efforts should focus on qPCR-based approaches (e.g., immuno-PCR), since these are easy to use, highly quantitative, require minimal starting material (so they can be used with rare or difficult to obtain samples), and can be adopted by laboratories around the world. Independent of the approach that is ultimately successful for this purpose, we will need clear and robust experimental and data standards that are agreed upon and adopted by the user community.

- Positional information and NGS approaches. To obtain the tools for specifically mapping and sequencing all RNA modifications, we propose several tasks. (1) We see large potential in mining bacterial systems and/or enzymes used by bacteria as defense mechanisms against other pathogens to identify RNA-targeting enzymes that recognize and modify (or protect) specific RNA motifs harboring individual modifications, such as those implemented in eTAM-seq. Another example comes from the bacterial (E. coli, Mycobacterium tuberculosis) toxin-antitoxin systems, which include the endoribonuclease MazF, which is capable of recognizing m6A-modified motifs on mRNA (Zhang et al., 2003, 2005; Zhu et al., 2006, 2008) and also cleaving rRNA (Schifano and Woychik, 2014; Schifano et al., 2013, 2014) and certain tRNAs (Schifano et al., 2016). Similar approaches have been used on a global RNA-seq level with techniques such as MORE-seq, which determines target sites of MazF (Schifano et al., 2024). (2) Recently, two approaches to map and quantify single-base m6A in the mammalian transcriptome have been introduced. GLORI-seq (Liu et al., 2023) and eTAM-seq (Xiao et al., 2023) use enzyme-assisted adenosine deamination to discriminate methylated from unmethylated adenosines at a single-nucleotide resolution. These techniques, although they avoid the false positive signals obtained by MazF and the limited MazF cleavage to ACA motifs, cannot discriminate between m6Am and m1A, are more expensive than traditional MeRIP-seq, and are limited to m6A. Development of similar enzyme-assisted approaches that discriminate between other modified and

- unmodified nucleotides at single-base resolution will significantly enhance our understanding of the biological importance and role of RNA modifications in mammalian systems. Finally, (3) we need to perform a systematic search for reverse transcriptases or DNA polymerases with RT activity (e.g., KlenTag and Marathon RT [de Cesaris Araujo Tavares et al., 2023]) to discover enzymes that can be engineered to detect individual RNA modifications; and (4) pursue discovery of RNA-specific CRISPR-Cas systems capable of recognizing and preferentially editing or cleaving modified versus unmodified RNA. The recent discovery of the Class VI CRISPR-Cas system effector, Cas13, shown to target RNA (Abudayyeh et al., 2020; East-Seletsky et al., 2016; Shmakov et al., 2015) makes this approach a promising option.

- Single-cell NGS for RNA modifications. We propose employing the enzyme-assisted sequencing described above (e.g., MAZTER-seq), by using newly discovered enzymes from bacterial systems to cleave single-cell RNA on certain modifications depending on the recognition specificity of the enzyme. The fragmented RNA could then be barcoded, or adaptor ligated, and sequenced at a single-cell level. Since this is still a laborious technology with a significant limitation for the number of cells that can be sequenced, we propose to develop recombinant enzymes as fusion enzymes with endoribonuclease activity and tagmentation capabilities (e.g., MazF-Tn5). These enzymes should be able to generate tagmented, modified RNA fragments that could be pooled and sequenced based on limitless combination of indexes and primers used for tagmentation, a technology reminiscent of combinatorial indexing.

Achieving these goals will require coordinated efforts from many laboratories and disciplines, using multiple complementary or orthogonal methods and approaches pursued in parallel to address the range of modifications in mRNA and their effects on structure and interactions. While we propose initial, proof-of-principle studies focused on mRNA and well-characterized modifications such as m6A, the methods we establish here should be expandable into other subsets of RNA—tRNA, rRNA, long noncoding RNA—as well as to other RNA modifications.

Long-Term Goals

The challenge of defining the impact of RNA modifications on RNA cellular function is a big task and will likely advance our understanding of RNA-modification biology in multiple directions. These will be punctuated by a series of long-term goals over the next 5–10 years:

- Develop single-cell (or low-abundance) modification sequencing to study structure at the single-cell level.

- Determine impact of RNA modifications on interactions of RNA with proteins (including readers, writers, and erasers of RNA modifications), other RNAs, and DNA sequences.

- Predict RNA structure based on modifications and sequence, including through use of molecular dynamic simulations and machine learning, and experimental approaches that probe RNA structure.

- Assess impact of structure on function.

Proposed methods for addressing long-term goals.

- Develop single-cell (or low abundance) modification sequencing to study base modifications at the single-cell level.

Existing technologies. The advent of single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) technology has brought about a lowered detection limit for rare RNA species, and facilitated new, previously unimaginable investigations. In conjunction with additional molecular techniques, scRNA-seq can now be coupled to chromatin accessibility, surface protein expression, and even spatial information (Heumos et al., 2023; Longo et al., 2021; Williams et al., 2022). Techniques such as the recently released RiboMap have even allowed translation to be monitored in a large subset of genes at spatial resolution across individual cells (Zeng et al., 2023). These applications of scRNA-seq are representative of the potential of sequencing individual RNAs in a single cell and provide encouragement for ultimately reaching the level of the single-cell or even single-molecule epitranscriptome. In fact, a recent example goes so far as to measure m6A levels in vivo, in single large cells (e.g., embryonic stem cells, zebrafish zygotes, mouse oocytes), suggesting that, in principle, our goal is not so far from reality (Li et al., 2023). The recent emergence of third-generation sequencing technologies such as Oxford Nanopore’s direct RNA sequencing is groundbreaking, but we still have room to grow. Early work has facilitated sequencing of individual RNAs, albeit with relatively high starting concentrations of RNA; has expanded our understanding of RNA processing; and has even allowed detection of some modifications, including m6A (Abebe et al., 2022; Jain et al., 2022; Stephenson et al., 2022). Unfortunately, error rates remain relatively high, secondary structure of the RNA can be a challenge, and the sensitivity is still lacking in most use cases (Leger et al., 2021; Liu, Begik, and Novoa, 2021; Liu-Wei et al., 2023; Zhang, Lu, and Li, 2022); however, the recent release of new, direct RNA-seq chemistry by Oxford Nanopore has started to address some of these issues. Bioinformatic strategies for processing scRNA-seq and direct RNA sequencing have greatly improved, but work remains to understand RNA modifications of a single molecule within a single cell (Cozzuto et al., 2020).

Specific actions. The first long-term goal we propose is to advance technology to be able to sequence modifications in individual cells and/or from low concentrations of RNA input. The added value for such an advance is obvious, as increased sensitivity of scRNA-seq will certainly increase our ability to detect RNA modifications, particularly rare or novel modifications that may only be observable in disease states. To achieve this goal, more reliable library preparation methods will likely be required, in addition to novel bioinformatic approaches to “deconvoluting” the data. We can imagine applications in conjunction with rapidly emerging AI technologies, which we suspect will greatly impact our day-to-day routines in the 5- to 10-year timespan. We also anticipate that increases in sensitivity and reliability of Oxford Nanopore direct RNA sequencing, and other platforms, will be required to reach this long-term goal. A major push in the field is already underway, but refined efforts towards defining best practices and providing benchmarking materials will be essential in providing a robust solution. For this purpose, better spike-in controls for modified RNAs will be needed to optimize approaches and more accurately identify RNA modifications in single cells and/or low-abundance samples.

Reliance on short-term goals. The improvement of scRNA-seq and direct RNA-seq to detect RNA modifications in low-abundance samples such as single cells will be built on the foundation established in our short-term goals. It will be essential to develop easy, affordable, and accessible techniques for quantifying modifications, such as m6A as a first use case. We appreciate that the solution to reliable, robust single-cell, single-molecule modification sequencing may require completely novel technology. We expect many advances in this direction to continue to come from mining of microbial systems, which have been repeatedly shown to carry vast potential. As work on understanding microbial communities continues, we expect that novel enzyme activities will be identified, for example, from nonmodel organisms, particularly the understudied fungi. The development of libraries of enzymes for modification-specific reactions will also likely facilitate new approaches, as has occurred with the examples discussed above.

- Determine impact of RNA modifications on interactions of RNA with proteins (including readers, writers, and erasers of RNA modifications), other RNAs, and DNA sequences.

Existing technologies. RNA modifications have been studied for decades to great success. Unfortunately, we still have an insufficient understanding of the role of RNA modifications in the interactions between modified RNA and other macromolecules. Certainly, examples exist, but the tools to understand these interactions on a large scale remain relatively absent. For example, we know that editing by proteins like adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR) can result in inosine-containing RNAs with altered innate immune activities (Liao et al., 2011; Sarvestani et al., 2014). Modified tRNAs were shown to fit more snuggly into the ribosome, suggesting alterations to interactions between the modified tRNA and ribosomal proteins/RNA (Dannfald, Favory, and Deragon, 2021; Hoffer et al., 2020; Yasukawa et al., 2001), and even mRNA methylation marks influence binding of downstream factors, including m6A core machinery and additional peripheral factors (Lewis, Pan, and Kolsotra, 2017; Shi, Wei, and He, 2019). These examples hint at regulation of biological function, but we also know that RNA modifications can influence RNA structure. Again, the best examples likely come from studing tRNA modifications, where installed modifications have been shown on numerous occasions to stabilize tRNA tertiary structure (Biedenbänder et al., 2022). RNA modifications are also thought to influence RNA:DNA hybrids after damage and during R-loop formation, hinting that a systemic description of the rules of interaction of the epitranscriptome with all cellular macromolecules holds vast potential in advancing our molecular understanding of the influence of RNA modifications on cellular interactions and function (Abakir et al., 2020).

Specific actions. To systematically define the influence of RNA modifications on intermolecular interactions, the field will need to strive for several key advances. First, a robust set of biochemical assays must be established and thoroughly tested to facilitate measurement of interactions between individual modified RNAs and other macromolecules. These initial biochemical assays should be extended to broad-scale analysis, likely requiring efforts to improve large-scale synthesis of modified RNAs for massively parallel reporter assays. Additional efforts in high-throughput synthesis of modifications at many sites simultaneously followed by structure elucidation will also be essential. It will be important to develop targeted RNA editing platforms that can be tunable to further introduce marks and determine structures.

Reliance on short-term goals. To succeed with the second long-term goal, we will need to develop easy, affordable, and accessible techniques for quantifying modifications as described above. The short-term goals described are necessary advances to characterize robustly the importance of modifications in intermolecular interactions. Again, as above, we see potential in mining microbial systems for novel enzyme potential, and we suspect that additional novel solutions will be found within the vast microbial pangenome. Many other tasks must also be completed, but we see value in developing tools that will further facilitate this long-term goal—for example, by developing libraries of enzymes for modification-specific reactions, endonucleases to facilitate single-molecule labeling, and RNA-targeting CRISPR/Cas systems that could be used for reading out modified RNAs or even intermolecular interactions.

- Predict RNA structure based on modifications and sequence, including through use of molecular dynamic simulations and machine learning.

Existing technologies. In recent years, cryo-electron microscopy technology and structural probing methods have greatly improved our understanding of tertiary interactions in RNA structure (Theil, Flamm, and Hofacker, 2017), yet in many cases RNA prediction remains the logical first step in understanding potential function. As such, a wide array of RNA prediction tools have been

developed to address this particular challenge (Mfold, ViennaFold/RNAfold, and many others) (Piechotta et al., 2022; Tsybulskyi, Semenchenko, and Meyer, 2023). These tools tend to rely on thermodynamic models, such as Turner’s nearest-neighbor model to predict secondary structures by focusing on nearest-neighbor loops (Sato, Akiyama, and Sakakibara, 2021). These can then be combined to find the minimum-free energy structure using the Zuker algorithm (Zuker, 1989). As we continue to obtain more experimentally validated structures, these predictions are more frequently based on reference molecules, which has improved prediction (Do, Woods, and Batzoglou, 2006; Zakov et al., 2011). The inclusion of advanced computational approaches is also pushing our prediction capabilities forward, for example by leveraging deep learning and neural networks (Booy, Ilin, and Orponen, 2022; Chen and Chan, 2023; Sato, Akiyama, and Sakakibara, 2021; Singh et al., 2019; Townshend et al., 2021). For the most part, the role of modifications in influencing tertiary, or even secondary, structure, has been difficult to incorporate into these predictions, but some efforts have been made (reviewed in Tanzer, Hofacker, and Lorenz, 2019), including prediction of structures with well-characterized modifications like m6A (Kierzek et al., 2022).

Specific actions. To successfully predict RNA tertiary structure for RNAs containing modifications, a much larger reference set of experimentally validated RNA structures is needed. As with AlphaFold for proteins, the use of AI can allow for valid, informative predictions with enough input, but our current cohort of RNA structures remains far too limited to saturate the complexity of RNA structures, especially RNA molecules containing modified nucleotides. In achieving this goal, we will continue to need organized, curated databases of high-quality structures to efficiently integrate large amounts of data into better learning predictions. In fact, some amazing examples of RNA structure and dynamics have already been predicted (Yu et al., 2021), but these computationally heavy predictions already push our computing power to the limit, suggesting additional advances are necessary. With recent successes in quantum computing, we expect that this technology, or even another currently unappreciated approach, will lead to sufficient resources for better predictions in the future. Although beyond the scope of this paper, performing such energy intensive computational activities should be developed with climate neutral strategies in mind.

Reliance on short-term goals. The recent progress in approaches like CLIP-seq (Hafner et al., 2021) and SHAPE-MaP (Bohn et al., 2023; Smola and Weeks, 2018) have facilitated a more rapid assessment of RNA structure in the laboratory, but additional approaches to more rapidly assess these structures in conjunction with RNA modifications are certainly needed. Our short-term goal in exploring additional methodologies for structural assessment of modified RNAs will be essential to improving predictions. Clearly, a better toolbox of benchmarking materials will also facilitate the structural determination of modified RNAs, allowing for the field to move closer to a state where an AlphaFold-like solution will be able to robustly, rapidly predict all RNA molecules.

- Assess impact of structure on function (as controlled by modifications).

Existing technologies. The fourth long-term goal strives to provide a resolution for the overall goal of understanding the functional consequences of RNA editing on RNA function, particularly during disease. RNA modifications are already known to control normal cellular homeostatic processes (Frye et al., 2018), contribute to regulation or dysregulation of cellular processes as during cancers (Haruehanroengra et al., 2020), and even influence the outcome of infection, both by regulating host immune processes and pathogen virulence (Cui et al., 2022). Modifications of tRNAs control translational fidelity (Agris et al., 2017), editing marks installed by ADAR and APOBEC3 proteins control autoimmunity and antiviral activity (Liu et al., 2018; Quin et al., 2021), and ribosomal RNAs are severely dysfunctional in the absence of modifications resulting in devastating human diseases (reviewed in Sharma and Entian, 2022). If we consider the m6A RNA modification as one example, we already a substantial amount (Sendinc and Shi, 2023). This prolific mark has

clear roles in the function of mRNAs as well as noncoding RNAs, but also contributes to regulation of housekeeping RNAs like rRNA. These functions collectively contribute to regulation of chromatin architecture, transcriptional regulation, and genome stability (Boulias and Greer, 2023). In fact, m6A methylation can also directly influence protein binding, for example by preventing binding of proteins to particular sites. A clear example of this regulation comes from C. elegans, where environmental growth conditions trigger the METT-10 writer to modify the 3’ splice site of S-adenosylmethionine synthetase to prevent binding of the essential splicing factor U2AF35 and splicing (Mendel et al., 2021). Many other examples show similar regulation of RNA modifications across biology, yet despite this clear importance, in most situations, RNA editing is barely considered in regulation.

Specific actions. Should our dream come to fruition, we expect to have the tools to produce a detailed description of RNA modifications on a single molecule of RNA in a single cell, which would facilitate the elucidation of cellular consequences of such modifications. Clearly a tall order, smaller steps again must be taken to reach this comprehensive understanding. We believe that striving to define a single, simple system more fully (e.g., a cell type selected from Encode Tier 1) will ultimately facilitate our larger goals. By perturbing such a system (e.g., with nutrient deprivation, genetic manipulation, temperature change, infection), we expect to understand the dynamics of modifications and the cellular consequences of RNA modifications. We expect that advances along the way will push analyses like these in many directions, beyond single-cell types to tissues or even whole organisms. By establishing workflows and techniques for a complete description the impact of RNA modifications on structure to control function in one cell type, we expect to facilitate easier investigations more broadly.

Reliance on short-term goals. Clearly the final long-term goal will rely on input from many of the other pieces of our approach. The success of the short-term goals, especially the creation of easy, affordable, and accessible techniques for quantifying modifications such as N6-methyladenosine (m6A) will be critical in reaching a fully described cellular example of RNA modification impact on function. At the moment, it is not clear how to achieve such a goal, but we expect that advancements in enzymatic studies, including novel activities mined from microbes, will facilitate our success.

Future Technologies

Several technologies already exist that can be leveraged for the success of this project. These include nuclear magnetic resonance, cryo-electron microscopy, X-Ray Crystallography, multiple sequencing strategies (including mass spectrometry, nanopore sequencing, and affinity capture methods), and a variety of bioinformatics approaches (e.g., machine learning) as described above. In order to realize these goals, a strategy must be established to incorporate existing technologies more robustly, support collaborations, promote the scientific exchange of ideas and foster development of new technologies. It is clear that the technology does not exist to fully address our stated challenge, but we can at least partially envision the advances required to reach these goals. We will certainly need alternative enzyme activities, which we can envisage being revealed through exploration of the microbial world or synthetic efforts to evolve or design new functionalities in existing enzymatic scaffolds. Among these activities, we anticipate the need for enzymes capable of barcoding modified RNA. Many laboratories and companies are already exploring this space, and we are cautiously optimistic that we are on the cusp of a revolution in RNA enzymology. Although we expect new functionalities and entirely new solutions, we do expect advances to continue from current workhorses, particularly with the rapid advancement in technologies surrounding the use of CRISPR-Cas-like approaches to specifically add/remove modifications. Synthetic biology tools and programmable RNA editing technologies may help establish or generate standardized reagents (reviewed in Booth et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2022).

We believe that the strategic, specific, and reliable installation of RNA modifications on synthetic RNA molecules is an advancing technology, but it still needs additional effort to realize a robust method to create useful standards for the types of experiments we are proposing. Synthesis of long RNAs with multiple modifications introduced at specified positions at proper stoichiometry would be a big advantage but remains nearly impossible. There are some promising leads in this direction, for example with techniques relying on enzymatic splint ligation (Gramper et al., 2022). With all these gains in the wet lab, we will also need to keep pace with our computational infrastructure.

If Moore’s law continues to hold true, we expect to see advances in computing power, as well as cleverly designed databases to support sharing of information on RNA modifications, structures, and interactions with appropriate metadata. Many discussions are currently underway, but key among them will be resources to maintain databases over long stretches of time, especially as computational techniques and supercomputing capabilities increase the amount of data collected from each experiment. Finally, we expect that optimization of experimental designs may also result in improvements in data output. As just one example, new approaches are constantly being explored to increase depth of coverage, as sequencing the same sample more deeply does not always reveal new information (e.g., modification sites or unique RNA molecules). We therefore expect that additional approaches will be developed to extract information from the datasets we have in hand, as well as to improve collection in new experiments.

Societal Relevance

Stakeholders

Depending upon where any biomedical research falls on the spectrum of basic to clinical, stakeholders in a research endeavor can include collaborators, peer reviewers, research institutions, funding agencies, clinicians and professional associations, patients, and policy makers (Concannon et al., 2019; Cottrell et al., 2014; Garrison et al., 2021). Collaborators can be actively engaged in a research endeavor, provide an important resource, or act in an advisory capacity. Peer reviewers, whether their purview is study protocols, manuscripts, or applications for funding, are engaged as stakeholders in upholding research rigor and ethical conduct. Research institutions, whether for-profit or not-for-profit entities, are a fundamental driver of research innovation and development. These institutions are often early incubators of patentable technologies developed from research. Research institutions, particularly those with graduate programs and professional schools, invest heavily in equipment, facilities, and personnel in support of the research activities of their faculty (Rosowsky, 2022). Biomedical and clinical research, especially those studies involving clinical trials, can be expensive. Much of this research is funded by federal agencies such as the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Energy, and Department of Defense, but organizations such as foundations and philanthropies support smaller research studies, too. Patients are increasingly seen as stakeholders in research involving their illnesses and medical care. Patient input provides important information for the development of essential aspects of a clinical study such as a study’s design and outcome measures. The importance of patient stakeholder engagement has been recognized and is oftentimes mandated or strongly endorsed by research funders and journals (Harrison et al., 2019). Policy makers include government agencies at the federal, state, and local levels as well as other funders of research. Policies based upon the interpretation of outcomes of major research endeavors can have a significant impact on public health (for example, vaccine development for COVID-19). Policy makers also determine research priorities and funding levels.

Ultimately, the more heavily invested—intellectually or financially—a collaborator, an institution, a funder, etc. is in a research project, the greater the stake that individual or group may feel they have in the success of that project.

Beneficiaries

In terms of potential economic impact, the beneficiaries of biomedical research would be widely ranging, from basic researchers, to patients, to local and national governments. In the short term, other basic researchers would benefit the most quickly from improved technologies in RNA structure prediction, molecular interaction detection, and direct RNA sequencing. For other groups pursuing clinical applications, the benefit will come in the long term after requisite steps, such as developing strategies to promote or block RNA modification-directed processes, clinical trials, and new drug development. In all cases, near-term and long-term benefit is dependent on the dissemination and adoption of any novel, cutting-edge technologies that are developed (Dearing and Cox, 2018).

Workforce, Educational, and Societal Considerations

There is disagreement within the scientific community on the “benefit” of research and development. Some express strong views that progress in science and technology, when enabled by regressive science policy practices, may make life harder for people, especially those already marginalized by class, gender, race, occupation, and location. One example is that scientific innovation, such as new therapeutics, mainly benefits those that can afford it (Bozeman, 2020). Others argue that public investment in science translates to public use of science, which is seen as a “benefit.” One such study analyzed the scientific literature and identified positive correlations between funding in a research area and scientific use. This extended to public use as well (Yin, 2022). At minimum, stronger public engagement in research planning and in the discussion of research outcomes may increase public perception of the importance and positive impact of RNA research on human health and medicine.

Workforce development, interdisciplinary training, and diversity and inclusion are certainly areas of critical need discussed at multiple, recent scientific venues, including a May 2022 workshop organized by the NIH, NHGRI, and NIEHS, entitled “Capturing RNA Sequence and Transcript Diversity, From Technology Innovation to Clinical Application” (NIEHS, 2022). The following were among several relevant points captured in the executive summary and report for the workshop.

- Support of both undergraduate and graduate-level training, especially at minority-serving institutions, could help improve diversity within the biomedical research community.

- Training in both “wet-lab” experimental methods and “dry-lab” computational biology and bioinformatics is critical for the advancement and widespread adoption of RNA technologies.

- Easily accessible, quality, low (or no)-cost, online training resources on technology use and data analysis could be a considerable driver in technology adoption.

- Enhancing career pathways for all groups, including those underrepresented in biomedical research, is important. Considerations include identifying current successful career enhancement approaches that could be scaled up, and determining resources and strategies needed to address ongoing barriers to advancement.

Anticipated Outcome

The end goal of the project is to understand how RNA modifications affect RNA function, including processing and interactions with other macromolecules on a transcriptome-wide scale. We can measure how completely we have addressed this challenge by assessing the RNA community’s ability to establish standards and common analysis pipelines to allow for a high degree of collaboration. This can also be supported by the level of usage of public data and sharing of data between groups. To accomplish this goal, we need an even higher degree of open data policies and data sharing between laboratories working in all aspects of the biology of RNA modifications.

We can assess the progress of single-cell technologies directly and in parallel with the depth and accuracy available for mapping and quantification of the various RNA modifications. A more challenging aspect to assess is the prediction of RNA structure and the influence of RNA modifications on structure and interactions with macromolecules. While the field is expected to continuously progress, when can we really claim that we have reached our goal? Certainly, we will have come a long way when tertiary structure can be predicted from primary sequence and the impact of a subset of the predominant mRNA modifications are faithfully incorporated in predictions (which are subsequently experimentally validated). Adding the ability to predict dynamic interactions with proteins accurately and reliably on a large scale, especially proteins involved in RNA processing, will bring us across the finish line.

The four long-term goals proposed will have tremendous impact on the RNA community, if accomplished, and they will provide unprecedented insight into the dynamics of RNA function and biological importance of RNA modifications. The development of single-cell knowledge of RNA modification identity and stoichiometry will reveal novel regulatory functions for subsets of RNA transcripts previously thought to be identical based on sequence information. With additional RNA modification information, we are likely to appreciate new flexible and dynamic conformations in these RNAs, in part mediated by differential RNA modification, which can mediate a multitude of previously unappreciated functions.

The ability to predict tertiary structure of RNA based on sequence and modification pattern will be a break-through for RNA research and will help establish RNA as an attractive molecule for several other disciplines to study. The ability to faithfully predict dynamic and context-dependent protein interactions will reveal new details of molecular biology with interest for RNA biologists, biochemists, protein researchers, and cell biologists, whereas an approach to predict RNA interaction with small molecules on a high level would revolutionize the potential of RNA medicine and provide new candidate targets for a plethora of diseases.

Conclusion

The Human Genome Project revealed the blueprint for building a human; however, the DNA sequence is just the beginning. We now must strive to understand the role of RNA in this construction process and fully elucidate the function of RNA in the cell, in all its modalities. The modifications introduced during RNA metabolism are considered by many to be a whole new level of gene expression regulation. By deciphering the regulatory code of RNA modifications, we will more completely understand the full potential of this macromolecule, unlock new functionalities for RNA, and likely provide novel therapeutic ingress points to the tremendous benefit of humanity. It is an undertaking worthy of continued research effort and investment.

REFERENCES

Abakir, A., T. C. Giles, A. Cristini, , J. M. Foster, N. Dai, M. Starczak, A. Rubio-Roldan, M. Li, M. Eleftheriou, J. Crutchley, L. Flatt, L. Young, D. J. Gaffney, C. Denning, B. Dalhus, R. D. Emes, D. Gackowski, I. R. Corrêa, J. L. Garcia-Perez Jr., A. Klungland, N. Gromak, and A. Ruzov. 2020. “N6-methyladenosine regulates the stability of RNA:DNA hybrids in human cells.” Nature Genetics 52(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0549-x.

Abebe, J. S., A. M. Price, K.E. Hayer, I. Mohr, M.D. Weitzman, A. C. Wilson, and D. P. Depledge. 2022. “DRUMMER-rapid detection of RNA modifications through comparative nanopore sequencing.” Bioinformatics 38(11), 3113–3115. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btac274.

Abudayyeh, O. O., J. S. Gootenberg, S. Konermann, J. Joung, I. M. Slaymaker, D. B. Cox, S. Shmakov, K. S. Makarova, E. Semenova, L. Minakhin, K. Severinov, A. Regev, E. S. Lander, E. V. Koonin, and F. Zeng. 2016. “C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector.” Science 353(6299):AAF5573. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf5573.

Agris, P. F., A. Narendran, K. Sarachan, V. Y. P. Väre, and E. Eruysal. 2017. “The importance of being modified: The role of RNA modifications in translational fidelity.” The Enzymes 41:1–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.enz.2017.03.005.

Arango, D., D. Sturgill, N. Alhusaini, A. A. Dillman, T. J. Sweet, G. Hanson, M. Hosogane, W. R. Sinclair, K. K. Nanan, M. D. Mandler, S. D. Fox, T. T. Zengeya, T. Andresson, J. L. Meier, J. Coller, and S. Oberdoerffer. 2018. “Acetylation of Cytidine in mRNA promotes translation efficiency.” Cell 175(7):1872–1886.E24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.030.

Arnez, J. G., and T. A. Steitz. 1994. “Crystal structure of unmodified tRNA(Gln) complexed with glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase and ATP suggests a possible role for pseudo-uridines in stabilization of RNA structure.” Biochemistry 33(24):7560–7567. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00190a008.

Aschenbrenner, J., and A. Marx. 2016. “Direct and site-specific quantification of RNA 2’-O-methylation by PCR with an engineered DNA polymerase.” Nucleic Acids Research 44(8):3495–3502. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw200.

Assmann, S. M., H-L. Chou, and P. C. Bevilacqua. 2023. “Rock, scissors, paper: How RNA structure informs function.” The Plant Cell 35(6):1671–1707. https://doi.org/10.1093/plcell/koad026.

Barbieri, I., and T. Kouzarides. 2020. “Role of RNA modifications in cancer.” Nature Reviews Cancer 20(6):303–322. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-020-0253-2.

Biedenbänder, T., V. de Jesus, M. Schmidt-Dengler, M. Helm, B. Corzilius, and B. Fürtig. 2022. “RNA modifications stabilize the tertiary structure of tRNAfMet by locally increasing conformational dynamics.” Nucleic Acids Research 50(4): 2334–2349. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac040.

Blanco, S., S. Dietmann, J. V. Flores, S. Hussain, C. Kutter, P. Humphreys, M. Lukk, P. Lombard, L. Treps, M. Popis, S. Kellner, S. M. Hölter, L. Garrett, W. Wurst, L. Becker, T. Klopstock, H. Fuchs, V. Gailus-Durner, M. Hrabĕ de Angelis, R. T. Káradóttir, M. Helm, J. Ule, J. G. Gleeson, D. T. Odom, and M. Frye. 2014. “Aberrant methylation of tRNAs links cellular stress to neurodevelopmental disorders.” EMBO Journal 33(18):2020–2039. https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.201489282

Bohn, P., A. S. Gribling-Burrer, U. B. Ambi, and R. P. Smyth. 2023. “Nano-DMS-MaP allows isoform-specific RNA structure determination.” Nature Methods 20(6):849–859. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-023-01862-7.

Booth, B. J., S. Nourreddine, D. Katrekar, Y. Savva, D. Bose, T. J. Long, D. J. Huss, and P. Mali. 2023. “RNA editing: Expanding the potential of RNA therapeutics.” Molecular Therapy 31(6): 1533–1549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.01.005.

Booy, M. S., A. Ilin, and P. Orponen. 2022. “RNA secondary structure prediction with convolutional neural networks.” BMC Bioinformatics 23(1):58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-021-04540-7.

Boulias, K., and E. L. Greer. 2023. “Biological roles of adenine methylation in RNA.” Nature Reviews Genetics 24(3):143–160. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-022-00534-0.

Bozeman, B. 2020. “Public Value Science.” Issues in Science and Technology 36(4) https://issues.org/public-value-science-innovation-equity-bozeman/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Castellanos-Rubio, A., I. Santin, A. Olazagoitia-Garmendia, I. Romero-Garmendia, A. Jauregi-Miguel, M. Legarda, and J. R. Bilbao. 2019. “A novel RT-QPCR-based assay for the relative quantification of residue specific m6A RNA methylation.” Scientific Reports 9(1):4220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40018-6.

Chen, C-C., and Y-M. Chan. 2023. “REDfold: Accurate RNA secondary structure prediction using residual encoder-decoder network.” BMC Bioinformatics 24(1):122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-023-05238-8.

Chen, X., A. Li, B-F. Sun, Y. Y. Yang, Y-N. Han, X. Yuan, R-X. Chen, W-S. Wei, Y. Liu, C-C. Gao, Y-S. Chen, M. Zhang, X-D. Ma, Z-W. Liu, J-H. Luo, C. Lyu, H-L. Wang, J. Ma, Y-L. Zhao, F-J. Zhou, Y. Huang, D. Xie, and Y-G. Yang. 2019. “5-methylcytosine promotes pathogenesis of bladder cancer through stabilizing mRNAs.” Nature Cell Biology 21(8):978–990. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-019-0361-y.

Choi, J., G. Indrisiunaite, H. DeMirci, K-W. Ieong, J. Wang, A. Petrov, A. Prabhakar, G. Rechavi, D. Dominissini, C. He, M. Ehrenberg, and J. D. Puglisi. 2018. “2′-O-methylation in mRNA disrupts tRNA decoding during translation elongation.” Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 25(3):208–216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-018-0030-z.

Concannon, T. W., S. Grant, V. Welch, J. Petkovic, J. Selby, S. Crowe, A. Synnot, R. Greer-Smith, E. Mayo-Wilson, E. Tambor, P. Tugwell, and Multi Stakeholder Engagement (MuSE) Consortium. 2019. “Practical guidance for involving stakeholders in health research.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 34(3):458–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4738-6.

Cottrell, E., E. Whitlock, E. Kato, S. Uhl, S. Belinson, C. Chang, T. Hoomans, D. Meltzer, H. Noorani, K. Robinson, K. Schoelles, M. Motu’apuaka, J. Anderson, R. Paynter, and J-M. Guise. 2014. Defining the benefits of stakeholder engagement in systematic reviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK196180/.

Cozzuto, L., A. Delgado-Tejedor, T. Hermoso Pulido, E. M. Novoa, and J. Ponomarenko. 2023. “Nanopore direct RNA sequencing data processing and analysis using MasterOfPores.” Methods in Molecular Biology 2624:185–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2962-8_13.

Cozzuto, L., H. Liu, L. P. Pryszcz, T. H. Pulido, A. Delgado-Tejedor, J. Ponomarenko, and E. M. Novoa. 2020. “MasterOfPores: A workflow for the analysis of Oxford Nanopore direct RNA sequencing datasets.” Frontiers in Genetics 11:211. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.00211.

Cui, L., R. Ma, J. Cai, C. Guo, Z. Chen, L. Yao, Y. Wang, R. Fan, X. Wang, and Y. Shi. 2022. “RNA modifications: Importance in immune cell biology and related diseases.” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 7(1):334. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01175-9.

Dannfald, A., J-J. Favory, and J-M. Deragon. 2021. “Variations in transfer and ribosomal RNA epitranscriptomic status can adapt eukaryote translation to changing physiological and environmental conditions.” RNA Biology 18(Suppl 1):4–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476286.2021.1931756.

Davis, D.R. 1995. “Stabilization of RNA stacking by pseudouridine.” Nucleic Acids Research 23(24):5020–5026. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/23.24.5020.

de Cesaris Araujo Tavares, R., G. Mahadeshwar, H. Wan, and A. M. Pyle. 2023. “MRT-ModSeq– Rapid detection of RNA modifications with MarathonRT.” Journal of Molecular Biology https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.25.542276 (accessed July 31, 2023).

Dearing, J. W., and J. G. Cox. 2018. “Diffusion of innovations theory, principles, and practice.” Health Affairs 37(2):183–190. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1104.

Decatur, W. A., and M. J. Fournier. 2002. “rRNA modifications and ribosome function.” Trends in Biochemical Sciences 27(7):344–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02109-6.

Delaunay, S., and M. Frye. 2019. “RNA modifications regulating cell fate in cancer.” Nature Cell Biology 21(5):552–559. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-019-0319-0.

Do, C. B., D. A. Woods, and S. Batzoglou. 2006. “CONTRAfold: RNA secondary structure prediction without physics-based models.” Bioinformatics 22(14):E90-98. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btl246.

Dominissini, D., S. Nachtergaele, S. Moshitch-Moshkovitz, E. Peer, N. Kol, M. S. Ben-Haim, Q. Dai, A. Di Segni, M. Salmon-Divon, W. C. Clark, G. Zheng, T. Pan, O. Solomon, E. Eyal, V. Hershkovitz, D. Han, L. C. Doré, N. Amariglio, G. Rechavi, and C. He. 2016. “The dynamic N(1)-methyladenosine methylome in eukaryotic messenger RNA.” Nature 530(7591):441–446. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16998.

Dominissini, D., and G. Rechavi. 2018. “N4-acetylation of cytidine in mRNA by NAT10 regulates stability and translation.” Cell 175(7):1725–1727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.037.

Dong, Z-W., P. Shao, L-T. Diao, H. Zhou, C-H. Yu, and L-H. Qu. 2012. “RTL-P: A sensitive approach for detecting sites of 2’-O-methylation in RNA molecules.” Nucleic Acids Research 40(20):E157.

East-Seletsky, A., M. R. O’Connell, S. C. Knight, D. Burstein, J. H. Cate, R. Tjian, and J. A. Doudna. 2016. “Two distinct RNase activities of CRISPR-C2c2 enable guide-RNA processing and RNA detection.” Nature 538(7624):270–273. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature19802.

Elliott, B. A., H-T. Ho, S. V. Ranganathan, S. Vangaveti, O. Ilkayeva, H. Abou Assi, A. K. Choi, P. F. Agris, and C. L. Holley. 2019. “Modification of messenger RNA by 2′-O-methylation regulates gene expression in vivo.” Nature Communications 10(1):3401. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11375-7.

Eyler, D. E., M. K. Franco, Z. Batool, M. Z. Wu, M. L. Dubuke, M. Dobosz-Bartoszek, J. D. Jones, Y. S. Polikanov, B. Roy, and K. S. Koutmou. 2019. “Pseudouridinylation of mRNA coding sequences alters translation.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116(46):23068–23074. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821754116.

Frye, M., B. T. Harada, M. Behm, and C. He. 2018. “RNA modifications modulate gene expression during development.” Science 361(6409):1346–1349. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau1646.

Gamper, H., C. McCormick, S. Tavakoli, M. Wanunu, S. H. Rouhanifard, and Y-M. Hou. 2022. “Synthesis of long RNA with a site-specific modification by enzymatic splint ligation.” https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.17.508400.

Garrison, H., M. Agostinho, L. Alvarez, S. Bekaert, L. Bengtsson, E. Broglio, D. Couso, R. Araújo Gomes, Z. Ingram, E. Martinez, A. Lúcia Mena, D. Nickel, M. Norman, I. Pinherio, M. Solís-Mateos, and M. G. Bertero. 2021. “Involving society in science: Reflections on meaningful and impactful stakeholder engagement in fundamental research.” EMBO Reports 22(11):E54000. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202154000.

Gerber, A.P., and W. Keller. 1999. “An adenosine deaminase that generates inosine at the wobble position of tRNAs.” Science 286(5442):1146–1149. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.286.5442.1146.

Hafner, M., M. Katsantoni, T. Köster, J. Marks, J. Mukherjee, D. Staiger, J. Ule, and M. Zavolan. 2021. “CLIP and complementary methods.” Nature Reviews Methods Primers 1(1):1–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-021-00018-1.

Harcourt, E. M., T. Ehrenschwender, P J. Batista, H. Y. Chang, and E. T. Kool. 2013. “Identification of a selective polymerase enables detection of N(6)-methyladenosine in RNA.” Journal of the American Chemical Society 135(51):19079–19082. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja4105792.

Harrison, J. D., A. D. Auerbach, W. Anderson, M. Fagan, M. Carnie, C. Hanson, J. Banta, G. Symczak, E. Robinson, J. Schnipper, C. Wong, and R. Weiss. 2019. “Patient stakeholder engagement in research: A narrative review to describe foundational principles and best practice activities.” Health Expectations 22(3):307–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12873.

Haruehanroengra, P., Y. Y. Zheng, Y. Zhou, Y. Huang, and J. Sheng. 2020. “RNA modifications and cancer.” RNA Biology 17(11):1560–1575. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476286.2020.1722449.

Helm, M., H. Brulé, F. Degoul, C. Cepanec, J. P. Leroux, R. Giegé, and C. Florentz. 1998. “The presence of modified nucleotides is required for cloverleaf folding of a human mitochondrial tRNA.” Nucleic Acids Research 26(7):1636–1643. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/26.7.1636.

Heumos, L., A. C. Schaar, C. Lance, A. Litinetskaya, F. Drost, L. Zappia, M. D. Lücken, D. C. Strobl, J. Henao, F. Curion, Single-cell Best Practices Consortium, H. B. Schiller, and F. J. Theis. 2023. “Best practices for single-cell analysis across modalities.” Nature Reviews Genetics 24(8):550–572. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-023-00586-w.

Hoernes, T. P., N. Clementi, K. Faserl, H. Glasner, K. Breuker, H. Lindner, A. Hüttenhofer, and M. D. Erlacher. 2016. “Nucleotide modifications within bacterial messenger RNAs regulate their translation and are able to rewire the genetic code.” Nucleic Acids Research 44(2):852–862. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1182.

Hoernes, T. P., D. Heimdörfer, D. Köstner, K. Faserl, F. Nußbaumer, R. Plangger, C. Kreutz, H. Lindner, and M. D. Erlacher. 2019. “Eukaryotic translation elongation is modulated by single natural nucleotide derivatives in the coding sequences of mRNAs.” Genes 10(2):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10020084.

Hoffer, E. D., S. Hong, S. Sunita, T. Maehigashi, R. L. Gonzalez, P. C. Whitford, and C. M. Dunham. 2020. “Structural insights into mRNA reading frame regulation by tRNA modification and slippery codon-anticodon pairing.” eLife 9:E51898. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.51898.

Ito, S., Y. Akamatsu, A. Noma, S. Kimura, K. Miyauchi, Y. Ikeuchi, T. Suzuki, and T. Suzuki. 2014. “A single acetylation of 18 S rRNA is essential for biogenesis of the small ribosomal subunit in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.” Journal of Biological Chemistry 289(38):26201–26212. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.593996.

Jack, K., C. Bellodi, D. M. Landry, R. O. Niederer, A. Meskauskas, S. Musalgaonkar, N. Kopmar, O. Krasnykh, A. M Dean, S. R. Thompson, D. Ruggero, and J. D. Dinman. 2011. “rRNA pseudouridylation defects affect ribosomal ligand binding and translational fidelity from yeast to human cells.” Molecular Cell 44(4):660–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2011.09.017.

Jain, M., R. Abu-Shumays, H. E. Olsen, and M. Akeson. 2022. “Advances in nanopore direct RNA sequencing.” Nature Methods 19(10):1160–1164. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-022-01633-w.

Jin, G., M. Xu, M. Zou, and S. Duan. 2020. “The processing, gene regulation, biological functions, and clinical relevance of N4-acetylcytidine on RNA: A systematic review.” Molecular Therapy- Nucleic Acids 20:13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2020.01.037.

Karijolich, J., C. Yi, and Y-T. Yu. 2015. “Transcriptome-wide dynamics of RNA pseudouridylation.” Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 16(10):581–585. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm4040.

Karijolich, J., and Y-T. Yu. 2011. “Converting nonsense codons into sense codons by targeted pseudouridylation.” Nature 474(7351):395–398. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10165.

Karikó, K., H. Muramatsu, F. A. Welsh, J. Ludwig, H. Kato, S. Akira, and D. Weissman. 2008. “Incorporation of Pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability.” Molecular Therapy 16(11):1833–1840. https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2008.200.

Khalique, A., S. Mattijssen, and R. J. Maraia. 2022. “A versatile tRNA modification-sensitive northern blot method with enhanced performance.” RNA 28(3):418–432. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.078929.121.

Kierzek, E., X. Zhang, R. M. Watson, S. D. Kennedy, M. Szabat, R. Kierzek, and D. H. Mathews. 2022. “Secondary structure prediction for RNA sequences including N6-methyladenosine.” Nature Communications 13(1): 1271. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28817-4.

King, T. H., B. Liu, R. R. McCully, and M. J. Fournier. 2003. “Ribosome structure and activity are altered in cells lacking snoRNPs that form pseudouridines in the peptidyl transferase center.” Molecular Cell 11(2):425–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00040-6.

Kumbhar, B. V., A. D. Kamble, and K. D. Sonawane. 2013. “Conformational preferences of modified nucleoside N(4)acetylcytidine, ac4C occur at ‘wobble’ 34th position in the anticodon loop of tRNA.” Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics 66(3):797–816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-013-9525-8.

Leger, A., P. P. Amaral, L. Pandolfini, C. Capitanchik C, F. Capraro, V. Miano, V. Migliori, P. Toolan-Kerr, T. Sideri, A. J. Enright, K. Tzelepis, F. J. van Werven, N. M. Luscombe, I. Barbieri, J. Ule, T. Fitzgerald, E. Birney, T. Leonardi, and T. Kouzarides. 2021. “RNA modifications detection by comparative Nanopore direct RNA sequencing.” Nature Communications 12(1):7198. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27393-3.

Lewis, C.J., T. Pan, and A. Kalsotra. 2017. “RNA modifications and structures cooperate to guide RNA-protein interactions.” Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 18(3):202–210. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm.2016.163.

Li, X., X. Xiong, M. Zhang, K. Wang, Y. Chen, J. Zhou, Y. Mao, J. Lv, D. Yi, X-W. Chen, C. Wang, S-B. Qian, and C. Yi. 2017. “Base-resolution mapping reveals distinct m1A methylome in nuclear- and mitochondrial-encoded transcripts.” Molecular Cell 68(5):993-1005.E9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.019.

Li, Y., Y. Wang, M. Vera-Rodriguez, L. C. Lindeman, L. E. Skuggen, E. M. K. Rasmussen, I. Jermstad, S. Khan, M. Fosslie, T. Skuland, M. Indahl, S. Khodeer, E. K. Klemsdal, K-X. Jin, K. T. Dalen, P. Fedorcsak, G. D. Greggains, M. Lerdrup, A. Klugland, K. F. Au, and J. A. Dahl. 2023. “Single-cell m6A mapping in vivo using picoMeRIP-seq.” Nature Biotechnology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-023-01831-7.

Liang, X-H., Q. Liu, and M. J. Fournier. 2007. “rRNA modifications in an intersubunit bridge of the ribosome strongly affect both ribosome biogenesis and activity.” Molecular Cell 28(6):965–977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.012

Liao, J-Y., S. A. Thakur, Z. B. Zalinger, K. E. Gerrish, and F. Imani. 2011. “Inosine-containing RNA is a novel innate immune recognition element and reduces RSV infection.” PLoS ONE 6(10):E26463. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0026463

Liu, C., H. Sun, Y. Yi, W. Shen, K. Li, Y. Xiao, F. Li, Y. Li, Y. Hou, B. Lu, W. Liu, H. Meng, J. Peng, C. Yi, and J. Wang. 2023. “Absolute quantification of single-base m6A methylation in the mammalian transcriptome using GLORI.” Nature Biotechnology 41(3):355–366. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01487-9

Liu, H., O. Begik, and E. M. Novoa. 2021. “EpiNano: Detection of m6A RNA modifications using Oxford Nanopore direct RNA sequencing.” Methods in Molecular Biology 2298:31–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-1374-0_3.

Liu, M-C., W-Y. Liao, K. M. Buckley, S. Y. Yang, J. P. Rast, and S. D. Fugmann. 2018. “AID/APOBEC-like cytidine deaminases are ancient innate immune mediators in invertebrates.” Nature Communications 9(1):1948. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04273-x

Liu-Wei, W., W. van der Toorn, P. Bohn, M. Hölzer, R. Smyth, and M. von Kleist. 2023. Sequencing accuracy and systematic errors of nanopore direct RNA sequencing. ttps://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.29.534691.

Longo, S. K., M. G. Guo, A. L. Ji, and P. A. Khavari. 2021. “Integrating single-cell and spatial transcriptomics to elucidate intercellular tissue dynamics.” Nature Reviews Genetics 22(10):627–644. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-021-00370-8

Mendel, M., K. Delaney, R. R. Pandey, K-M. Chen, J. M. Wenda, C. B. Vågbø, F. A. Steiner, D. Homolka, and R. S. Pillai. 2021. “Splice site m6A methylation prevents binding of U2AF35 to inhibit RNA splicing.” Cell 184(12):3125-3142. E25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.062.

Meyer, K. D. 2019. “DART-seq: An antibody-free method for global m6A detection.” Nature Methods 16(12):1275–1280. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-019-0570-0.

Mulroney, L., E. Birney, T. Leonardi, and F. Nicassio. 2023. “Using Nanocompore to identify RNA modifications from direct RNA Nanopore sequencing data.” Current Protocols 3(2):E683. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpz1.683.

Newby, M.I., and N. L. Greenbaum. 2002. “Investigation of Overhauser effects between pseudouridine and water protons in RNA helices.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99(20):12697–12702. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.202477199.

NIEHS (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences). 2022. Capturing RNA Sequence and Transcript Diversity, From Technology Innovation to Clinical Application. Virtual event occurring May 24–26, 2022. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/news/events/pastmtg/2022/rnaworkshop2022/index.cfm (accessed July 24, 2023).

Pandolfini, L., I. Barbieri, A. J. Bannister, A. Hendrick, B. Andrews, N. Webster, P. Murat, P. Mach, R. Brandi, S. C. Robson, V. Migliori, A. Alendar, M. d’Onofrio, S. Balasubramanian, and T. Kouzarides. 2019. “METTL1 promotes let-7 MicroRNA processing via m7G methylation.” Molecular Cell 74(6):1278–1290.E9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2019.03.040.

Piechotta, M., I. S. Naarmann-de Vries, Q. Wang, J. Altmüller, and C. Dieterich. 2022. “RNA modification mapping with JACUSA2.” Genome Biology 23(1):115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-022-02676-0.

Pratanwanich, P. N., F. Yao, Y. Chen, C. W. Q. Koh, Y. K. Wan, C. Hendra, P. Poon, Y. T. Goh, P. M. L. Yap, J. Y. Chooi, W. J. Chng, S. B. Ng, A. Thiery, W. S. S. Goh, and J. Göke. 2021. “Identification of differential RNA modifications from nanopore direct RNA sequencing with xPore.” Nature Biotechnology 39(11):1394–1402. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-021-00949-w.

Quin, J., J. Sedmík, D. Vukić, A. Khan, L. P. Keegan, and M. A. O’Connell. 2021. “ADAR RNA modifications, the epitranscriptome and innate immunity.” Trends in Biochemical Sciences 46(9):758–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2021.02.002.

Rosowsky, D. 2022. “The role of research at universities: Why it matters.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidro-sowsky/2022/03/02/the-role-of-research-at-universities-why-it-matters/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Saikia, M., Y. Fu, M. Pavon-Eternod, C. He, and T. Pan. 2010. “Genome-wide analysis of N1-methyl-adenosine modification in human tRNAs.” RNA 16(7):1317–1327. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.2057810.

Sarvestani, S. T., M. D. Tate, J. M. Moffat, A. M. Jacobi, M. A. Behlke, A. R. Miller, S. A. Beckham, C. E. McCoy, W. Chen, J. D. Mintern, M. O’Keeffe, M. John, B. R. G. Williams, and M. P. Gantier. 2014. “Inosine-mediated modulation of RNA sensing by Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) and TLR8.” Journal of Virology 88(2):799–810.

Sato, K., M. Akiyama, and Y. Sakakibara. 2021. “RNA secondary structure prediction using deep learning with thermodynamic integration.” Nature Communications 12(1):941. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21194-4.

Schevitz, R. W., A. D. Podjarny, N. Krishnamachari, J. J. Hughes, P. B. Sigler, and J. L. Sussman. 1979. “Crystal structure of a eukaryotic initiator tRNA.” Nature 278(5700):188–190. https://doi.org/10.1038/278188a0.

Schifano, J. M., J. W. Cruz, I. O. Vvedenskaya, R. Edifor, M. Ouyang, R. N. Husson. 2016. “tRNA is a new target for cleavage by a MazF toxin.” Nucleic Acids Research 44(3):1256–1270. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1370.

Schifano, J. M., R. Edifor, J. D. Sharp, M. Ouyang, A. Konkimalla, R. N. Husson, and N. A. Woychik. 2013. “Mycobacterial toxin MazF-mt6 inhibits translation through cleavage of 23S rRNA at the ribosomal A site.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110(21):8501–8506. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1222031110.

Schifano, J. M., I. O. Vvedenskaya, J. G. Knoblauch, M. Ouyang, B. E. Nickels, and N. A. Woychik. 2014. “An RNA-seq method for defining endoribonuclease cleavage specificity identifies dual rRNA substrates for toxin MazF-mt3.” Nature Communications 5:3538. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4538.

Schifano, J. M., and N. A. Woychik. 2014. “23S rRNA as an a-Maz-ing new bacterial toxin target.” RNA Biology 11(2):101–105. https://doi.org/10.4161/rna.27949.

Seeburg, P. H., and J. Hartner. 2003. “Regulation of ion channel/neurotransmitter receptor function by RNA editing.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 13(3):279–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00062-x

Sendinc, E., and Y. Shi. 2023. “RNA m6A methylation across the transcriptome.” Molecular Cell 83(3):428–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2023.01.006.

Shanmugam, R., J. Fierer, S. Kaiser, M. Helm, T. P. Jurkowski, and A. Jeltsch. 2015. “Cytosine methylation of tRNA-Asp by DNMT2 has a role in translation of proteins containing poly-Asp sequences.” Cell Discovery 1(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/celldisc.2015.10.

Sharma, S., and K-D. Entian. 2022. “Chemical modifications of ribosomal RNA.” Methods in Molecular Biology 2533:149–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2501-9_9.

Shen, H., R. J. Ontiveros, M. C. Owens, M. Y. Liu, U. Ghanty, R. M. Kohli, and K. F. Liu. 2021. “TET-mediated 5-methylcy-tosine oxidation in tRNA promotes translation.” Journal of Biological Chemistry 296:100087. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.ra120.014226.

Shi, H., J. Wei, and C. He. 2019. “Where, when and how: Context-dependent functions of RNA methylation writers, readers, and erasers.” Molecular Cell 74(4):640–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2019.04.025.

Shmakov, S., O. O. Abudayyeh, K. S. Makarova, Y. I. Wolf, J. S. Gootenberg, E. Semenova, L. Minakhin, J. Joung, S. Konermann, K. Severinov, F. Zhang, and E. V. Koonin. 2015. “Discovery and functional characterization of diverse Class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems.” Molecular Cell 60(3):385–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.008.

Singh, J., J. Hanson, K. Paliwal, and Y. Zhou. 2019. “RNA secondary structure prediction using an ensemble of two-dimensional deep neural networks and transfer learning.” Nature Communications 10(1):5407. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13395-9.

Smola, M. J., and K. M. Weeks. 2018. “In-cell RNA structure probing with SHAPE-MaP.” Nature Protocols 13(6):1181–1195. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2018.010.

Stephenson, W., R. Razaghi, S. Busan, K. M. Weeks, W. Timp, and P. Smibert. 2022. “Direct detection of RNA modifications and structure using single-molecule nanopore sequencing.” Cell Genomics 2(2):100097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xgen.2022.100097.