Charting a Future for Sequencing RNA and Its Modifications: A New Era for Biology and Medicine (2024)

Chapter: 4 Standards and Databases for RNA Modifications

4

Standards and Databases for RNA Modifications

Standards and databases are foundational to ensuring that shared expectations for components, processes, products, and data are met (see Box 4-1). Currently, efforts to sequence RNA and its modifications lack many of the standards and database management principles that are key to long-term success. To meet the goals of this report, significant gaps need to be addressed in physical, data, and database standards, as well as standards for the management of data resources.

Research on RNA and its modifications will benefit greatly from a broader collection of modified nucleosides and oligonucleotides of known sequence and modification status. Such physical standards are necessary as experimental controls, for calibrating and improving the performance of commonly used instruments, and for developing new sequencing technologies.

To simplify data sharing and access, there is a need for clear, consistent, and widely used data standards around modified RNA nomenclature and representation of modified RNA datasets. Clear guidance is needed on data quality that can enhance scientific reproducibility and is appropriate for deposition (including an agreed-upon repository), along with enforcement of such guidance that is consistent with open science principles in the United States and internationally (Nelson, 2022; UNESCO, 2023).

Additionally, while there are many databases that store information on modified RNAs, these are managed largely by individual or small groups of research laboratories, and they may have a narrow focus on a particular modification or curate information based only on RNA type. It is likely that progress in creating data standards will also spur more widely accessible and informative databases once such information can be more easily shared among database platforms.

This chapter examines the current state of physical, data, and database standards used by researchers for studying RNA modifications. It also surveys currently available RNA databases that catalog RNA modifications. The chapter closes by identifying future needs in the realms of standards and databases that will accelerate and support research in RNA and its modifications.

BOX 4-1

Types of Standards and Their Uses

Standards define goals and metrics for technology developers and others. Their use for calibration allows measurements made in independent laboratories to be compared and facilitates data aggregation and reuse to allow collective-science approaches to uncovering new biological knowledge. Broadly, standards needed for RNA modification and sequence analysis can be categorized as physical, data, and database standards. There are also standards that could be applied to biochemical methods and biological reagents.

Physical standards refer to specifications and the accompanying physical materials that reflect those specifications, which together encode the “ground truth” that any technology should uncover when applied to the physical standard. Physical standards are independent of mapping technologies and thus serve as a benchmark for technology developers to meet; they allow the community to evaluate new technological developments and interpret with confidence data obtained on biological samples. Physical standards can also be used in practice as calibration standards, where their regular use would allow different instruments to be tuned to meet the standard specifications. For example, an oligonucleotide standard with known modifications could be used as a standard to validate new approaches, or as a spike-in calibration standard in experiments to measure modification abundance. Additionally, such standards can be used for internal calibration to help control day-to-day variation in instrument operation and to facilitate data sharing among different labs. Depending on the specification, physical standards could entail biological materials that have been synthetically derived or manufactured from biological materials. Physical standards may also coincide with standard operating procedures and protocols for their use.

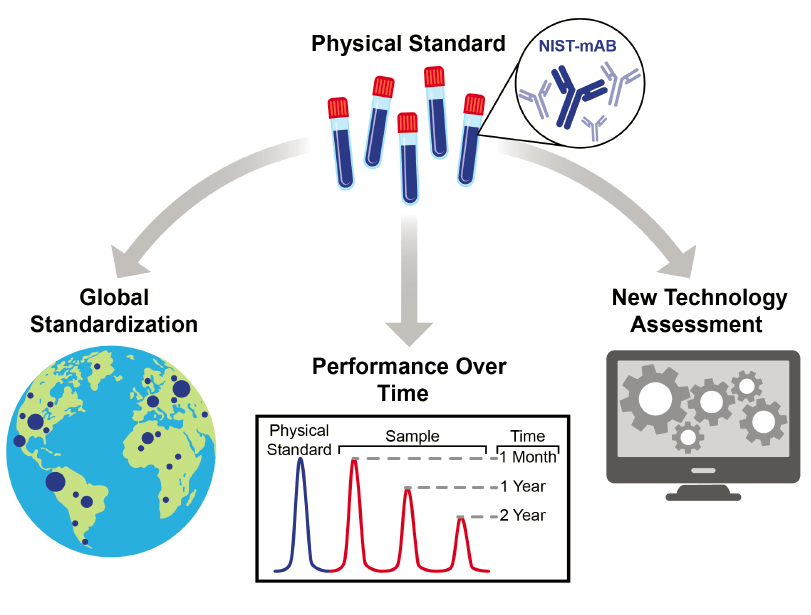

An example of the generation and curation of a physical standard is the NIST-mAB program (NIST, 2016) (Figure 4-1). NIST-mAB is a monoclonal antibody manufactured, characterized, curated, and distributed by the National Institute for Standards and Technologies (NIST) to aid in protein characterization and analytical development. This protein is fully representative of therapeutic proteins produced from Chinese hamster ovary tissue culture cells, but it lacks a therapeutic effect. NIST-mAB was manufactured by methods representative of current commercial processing, then characterized, released, and dispensed for distribution. The NIST-mAB standard has been used for glycoform, sequence, and structural analyses using routine analytics and then comparing the results in either open technical forums or in an anonymized fashion curated by NIST. Such standards are also useful for comparing innovative technologies with established ones, exploring issues of material stability or materials compatibility, comparing analyses performed in different laboratories, assessing contributions of measurement uncertainty to process control, and investigating unexpected results or systems failures. Using a single, shared standard such as NIST-mAB enables studies that might not be undertaken otherwise, such as those that require rare or valuable samples or commercial biotherapeutics managed within production quality management systems and subject to oversight by regulatory agencies. An analogous program for RNA might envision physical standards of a defined messenger RNA (mRNA) or a panel of oligonucleotides that could be shared across investigational labs, technologies, and applications.

Data standards are “technical specifications that describe how data should be stored or exchanged for the consistent collection and interoperability of the data across different systems, sources, and users” (FEDR, para. 2). Data standards, such as a universal nomenclature that describes data elements, interoperable raw data formats, and common ontologies, help facilitate data sharing and reuse by the broader scientific community.

In the technology development phase, it is important to develop standards for the raw data generated by instruments to help researchers work collectively on solving the challenges of extracting signals from complex data. Data standards are also critical when projects are in data collection phases to enable researchers to collect data generated from disparate contexts and conditions, allowing more holistic perspectives to uncover new biology of RNA modifications. Furthermore, generating experimentally determined modifications data at a remarkable efficiency and volume as envisioned here will also provide training data for accurate artificial intelligence and machine learning predictive models. For example, AlphaFold2 was trained on data from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) consisting of more than 100,000 experimental protein structures to generate more than 214 million predicted protein structures, as of 2024 (Jumper et al., 2021; Varadi et al., 2023). Additionally, the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB) PDB a has now integrated more than 1 million predicted structures alongside the experimentally determined structures. Within the goals of this program, a clear nomenclature for RNA modifications will accelerate the sharing and dissemination of key biological information. Moreover, such data provide the basis for ongoing and future work to create tools for predicting modifications with high confidence.

Database standards are guidelines, rules, and conventions that define how databases are designed, implemented, and managed. These standards ensure data consistency, interoperability, and reliability in an increasingly complex and data-driven world. They are developed and maintained by various groups, organizations, and consortia to create a common framework for database management. The primary goals of database standards are maintaining data accuracy, facilitating seamless communication between systems, ensuring data integrity, enhancing security, optimizing performance, and supporting data portability. Database standards need to build upon data standards to enable end users to access information in a format and presentation that can be shared and utilized readily without specialized expertise or training. Within the RNA field, ensuring that existing and future databases follow these conventions will enable the broadest possible applications of this knowledge for solving critical challenges.

__________________

a See https://www.rcsb.org (accessed January 31, 2024).

THE CURRENT STATE OF STANDARDS

The field of RNA modification mapping and analysis has a dearth of standards. Protocols for sample preparation, sequencing, mapping, and biochemical analysis vary among laboratories. Relatively few modified ribonucleoside standards and RNA sequences have known, quantified, site-specific modifications available for researchers. What is available is housed predominantly in individual academic labs that typically cannot produce them in amounts suitable for wide distribution.

There are no universal guidelines for submission of raw sequencing and mapping data generated from direct RNA-sequencing technologies to journals and repositories, and the nomenclature for RNA modifications is not yet uniform. As a result, storage methods for RNA sequences and their modification information are not streamlined. Additionally, not all databases that catalog RNA modifications use FAIR principles.1

As research on RNA modifications grows and the volume of data swells, the field will need to improve all categories of standards to ensure high-quality, reproducible results; equitable access to data; and the ability to translate basic research findings into improvements in health care, manufacturing, and agriculture.

Standard Procedures

Establishing standardized procedures and best practices for working with RNA and its modifications is a means of ensuring consistency in the scientific process. Ideally, these protocols will clarify for the research community reasonable expectations for sample purity, yield, and integrity. It may be unrealistic, however, to expect a universal protocol for the approaches discussed in this report, as different sample sources, RNA types, and technologies may require protocols tailored to their end goals. Nonetheless, making such individualized protocols more uniform would enable cross-validation of results across sequencing platforms and technologies.

While several protocols exist for RNA purification (Kanwal and Lu, 2019; Mullegama et al., 2019; Nilsen, 2013; Walker and Lorsch, 2013; Wang, Hayatsu, and Fujii, 2012), they often do not consider the presence and potential lability and reactivity of modified nucleosides. For example, while there are several often-cited protocols for isolating and digesting RNA to study its modified nucleosides (Crain, 1990; Thüring et al., 2016), recent reports have shown that global analysis of RNA modifications by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) can be prone to artifacts or other identification errors (Cai et al., 2015; Jora et al., 2021; Kaiser et al., 2021; Matuszewski et al., 2017).

Among the existing approaches for mapping RNA modifications using either next-generation sequencing (NGS) or third-generation sequencing (TGS), there is far-ranging variability in sample preparation and handling, data analysis, and data interpretation (Motorin and Marchand, 2021), as detailed in Chapter 3. In particular, a number of recent reviews and commentaries have discussed the disagreements among published results, especially regarding modifications other than N6-methyladenosine (m6A) that have been identified in human messenger RNAs (mRNAs) (Kong, Mead, and Fang, 2023; Wiener and Schwartz, 2021). As the field has grown, so has understanding of the strengths and limitations of various NGS and TGS methods for sequencing modified RNAs.

Many different protocols are in use, which can make it challenging to compare results from different laboratories (Koonchanok et al., 2023; Lemsara, Dieterich, and Naarmann-de Vries, 2023; Ueda, Dasgupta, and Yu, 2023; Wongsurawat, Jenjaroenpun, and Nookaew, 2022). Imperfections that arise with any new technology or method result in uncertainties in the data. Therefore, a rigorous approach to experimentation and analysis is imperative to avoid misinterpreting data collected

___________________

1 FAIR refers to findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (Wilkinson et al., 2016). See https://www.go-fair.org/fair-principles/ (accessed November 8, 2023).

using these novel technologies. Use of appropriate standards both to benchmark methods and to develop orthogonal methods for validating RNA modification mapping will also be important.

Therefore, a clear need exists to evaluate many of the sequencing and modification mapping approaches and protocols, with the goal of establishing a set of best practices. Even more, standardization is needed to enhance data rigor and reproducibility while simplifying the process for those newly entering the field.

One approach is for several laboratories with expertise in the handling and analysis of RNA to coordinate methods of sample preparation and downstream techniques, and to measure reproducibility among labs. This can serve to create reliable standardized protocols and procedures that other labs can adopt. Once established, these approaches can then be disseminated and serve as benchmarks for interlab tests, such as those conducted by the Association of Biomolecular Resource Facilities Research Groups.2

Physical Standards

Two categories of physical standards are necessary when characterizing RNA modifications: (1) standards for modified nucleosides and (2) standards for RNA sequences with known, quantified, site-specific modifications.

Standards for modified nucleosides will be a set of pure, well-characterized modified nucleosides and nucleotides, which are needed to verify the identity and quantity of a modification present within an RNA and can be used to evaluate the physical and chemical stability of the modification. In practice, these are used to establish the replicability of methods used for the global analysis of RNA modifications (Thüring et al., 2016). An example of such a standard is the commercially available Nucleosides Test Mix from Sigma-Aldrich.3 This mixture of nucleosides comes with a certificate of origin and analysis that confirms the identity and quantity of each component in the mixture.

One challenge in the field is the limited availability of chemically well-defined ribonucleosides and modified nucleobases to represent those that are naturally occurring; currently, these cannot be readily obtained to be used as standards. Although many modified nucleosides were synthesized in academic research laboratories as standards to verify the structure and function of previously unknown modifications (Cantara et al., 2011; Limbach, Crain, and McCloskey, 1994), the time, effort, and expense required to recreate these modified nucleosides means that they are typically not available for use upon request. In addition, the chemical synthesis protocols are too often not detailed in the literature but instead remain within the confines of individual academic labs. Moreover, the current academic research and publication incentive structure does not recognize or reward labs that have the capabilities to create these standards—even at scale—unless there is some novel function (e.g., alters binding to a regulatory protein) known to be associated with the modification. Furthermore, the synthesis of some modified nucleosides may be difficult to scale up, which makes the resource investment impractical. For commercial vendors, unless a significant market exists for specific modified nucleosides, there is no economic impetus to synthesize and sell the molecules.

The second category of physical standards desired for defining all the RNA modifications and their sequence context is a single RNA sequence or collection of RNA sequences with modifications present at known locations and in measured stoichiometries. Moreover, such standards enable instruments to define the analytical performance of current and future technologies, such as basecalling accuracy, reproducibility, and signal-to-noise requirements for optimal performance.

___________________

2 See https://www.abrf.org/about-research-groups (accessed January 19, 2024).

3 See https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/US/en/product/supelco/47310u (accessed November 13, 2023).

Before developing this type of physical standard, several important questions need to be considered: RNA modifications are diverse, and they can occur in a complex range of different RNA sequence and structure contexts. Furthermore, some biological RNAs contain a diversity of modifications, which may be densely represented across the RNA sequence, while other RNAs have both low density and low diversity of modifications (see Chapter 3). Should such standards be a collection of molecules with exactly one different modification in each? Should they be a collection of molecules with modifications in all sequence or structural contexts? How many different modifications should be included within the RNA sequence? While answers to these questions depend on the analysis goals, another important consideration is whether the ideal modified RNA sequence standard can be chemically synthesized; a process that often requires new method development—again, an expensive enterprise.

Some modifications can be synthesized enzymatically. This requires recombinant enzymes in sufficient amounts and of sufficient robustness to generate modified RNAs in bulk. Unfortunately, the specificity of many enzymes hinders the generation of proper standards on a desired RNA. For example, while a transfer RNA (tRNA)–specific enzyme may be capable of adding only a certain modification to a specific position in a single type of tRNA, in many cases, the particular modification reaction has not yet been reconstituted in vitro (Machnicka et al., 2014). Moreover, even for reconstituted systems, ensuring stoichiometric modification at a particular site using this approach is also challenging.

An alternative to chemically or enzymatically synthesized standards is purifying modified RNAs of known sequence and modification content from natural sources, which is most easily done from organisms that are easily grown in culture and for which the RNA modification set is mostly known, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Escherichia coli (Svetlov and Artsimovitch, 2015; Tardu et al., 2019). But even for these two model organisms current purification methods are neither very efficient nor standardized for generating large quantities of a particular RNA, and the modification stoichiometry may vary depending on culturing and purification conditions. In addition, these protocols require large culture volumes, such that even sample processing becomes a daunting task. At times, investigators have resorted to overexpression of a particular RNA species in cells, but this can lead to RNAs that are not fully modified by the cell, which hampers the prospect of producing sufficient native RNA standards for downstream applications.

The physical standards described thus far are used primarily for verifying sample purification methods and technical approaches, serving as sources of truth for identification, and other qualitative purposes. Another important need in the field is physical standards that can be used for quantitative purposes—such as measuring sample recovery, yield, loss, and integrity throughout the entire isolation, purification, and analysis pipeline. For example, isotopically labeled reagents that are added in a fixed amount early in the pipeline and can be measured independently, along with the analyte of interest, to obtain highly precise and accurate quantitative measurements are often desired for quantification by mass spectrometry. Thus, to ensure consistency, advancements in the field will require physical standards in the form of nucleosides and oligonucleotides that are available in a variety of isotopic forms.

Once physical standards are being produced for a range of RNA modifications, it is imperative that the standards be readily available to researchers. This will require establishing commercial logistics involving manufacturing, storing, and distributing a standard so that researchers can afford and readily obtain the desired physical standards and trust that the standards are of a quality that suits their research purposes. (This is of course an area in which many chemical manufacturing companies excel.) Only then would these standards be of use as, for example, calibration standards in day-to-day experiments.

Biological and Biochemical Standards

Biological materials in the form of antibodies and engineered enzymes have been widely used to map RNA modifications. Standard practices for validating these materials need to be established, in order to ensure that biological reagents have the specificity and sensitivity to report accurate results on the position and/or abundance of an RNA modification of interest. Such practices may include loss of signal in RNA obtained from cells subjected to modification enzyme inhibition, depletion, or knockout. In cases in which such samples are not available, standards for validation using biochemical competition assays (e.g., using synthetic RNA oligonucleotides with chemically similar modifications to the one in question) need to be established to ensure that there is no cross-reactivity or nonspecific detection. Oligonucleotide spike-in experiments can also be useful as standard practices for measuring modification abundance. Similar approaches can be taken to validate the specificity and sensitivity of methods for detecting RNA modifications that involve measuring modification-specific responses to chemical treatments (e.g., sodium bisulfite treatment to detect 5-methylcytosine, glyoxal and nitrite treatment to detect m6A [Liu et al., 2023; Xue, Zhao, and Li, 2020]).

Standards for Raw Data, Nomenclature, and Common Ontologies

Multiple considerations come into play when reviewing the state of data standards in the RNA modification field. The nomenclature for denoting RNA modifications is imprecise, and in an age when the expectation is that any individual from anywhere on the globe should be able to access biological information (such as the complete characterization of RNA transcripts with modifications) without a proprietary interface, it will be key to ensure that the “alphabet” of RNA modifications is both universal and accepted. Modomics has compiled nomenclature and codes that can be used to represent specific RNA modifications within larger sequence files (Boccaletto et al., 2022). However, this representation system requires translating single character codes into the full identity of the modified nucleoside. What is more, these codes have not been accepted universally by other databases that focus on a small subset of modifications or on a specific type or class of RNAs, nor do they allow for encoding any quantitative information about modification stoichiometry. Until both the method and coding for representing modified RNA sequences are agreed upon—considering their pivotal role in storage, transmission, and representation in bioinformatics databases—it will be challenging for end users to access and manipulate sequence-based data, as are now readily available for unmodified DNA or RNA sequences.

A second consideration is that data standards are required for the raw data generated by any instrument during the analysis of a sample. Unsurprisingly, commercial vendors of such instruments typically use a proprietary data standards package for decoding and analysis. While third-party solutions may exist for converting proprietary data formats into a more generic and accessible format, it will be necessary to create standards for format and location when storing these raw data. For example, models exist in mass spectrometry–based areas, such as proteomics (Springer Nature, n.d.), that could form the basis for a collective understanding of any mass spectrometry–based RNA sequencing or modification mapping data. Similar data standards are needed for indirect and direct sequencing and mapping methods that do not utilize mass spectrometry.

A third consideration arises around data standards as applied to the quality and accuracy of the base- or modification calling of data analysis software packages. As noted in Chapter 3, several different scoring algorithms and approaches have been proposed in mass spectrometry–based analyses (D’Ascenzo et al., 2022; Sample et al., 2015; Wein et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2017), with no clear consensus on what criteria should be used when reporting out a modification within a sequence. Establishing a reference MS/MS dataset, such as those of the National Institute of Standards and

Technology (NIST), may be required to evaluate both existing and new software tools. This reference dataset could establish minimal criteria for modification calling—for example, at least 80 percent of the expected product ions (fragment ions) from a given oligonucleotide (e.g., RNase T1 digestion product) must be detected at a mass accuracy of 1 part per million or less with no false positives.

For other direct sequencing methods, it would be valuable to develop datasets for benchmarking and training new basecalling algorithms. An existing reference dataset that could be used as a model is the Modified NIST (MNIST) handwritten digits dataset, which is used for benchmarking image recognition algorithms (LeCun et al., 1998).

Database Standards

Database standards facilitate seamless data integration, data analytics, and cloud adoption by providing a consistent foundation for users to work from. These standards support a variety of data streams from emerging and novel technologies in genomics, and they play a crucial role in global collaborations and data governance strategies. Database standards encompass the following aspects of database management:

- Data modeling: Database standards offer guidelines for creating data models that accurately represent biology of RNA processing pathways as they occur in living systems and their relationships with other biological pathways. This ensures a structured approach to designing databases that can evolve as needs change.

- Query languages: Standards for query languages, such as SQL, provide a consistent way to interact with databases. This uniformity simplifies database development and management across different platforms.

- Normalization: Database standards define normalization rules that minimize data redundancy and anomalies, ensuring data integrity and quality.

- Indexing and optimization: Standards guide the creation and maintenance of indexes, enhancing query performance and database efficiency.

- Security, privacy, and compliance: Database standards encompass security measures, including access control, authentication, and encryption, to safeguard sensitive data from unauthorized access and breaches. Such considerations will be crucial for storing and sharing clinically relevant RNA modification data and for integration with patient registries.

- Data exchange formats: Common data exchange formats, such as XML and JSON, are standardized to enable interoperability among diverse RNA database systems, since they can significantly increase accessibility when mirroring public resources across laboratories and countries.

- Backup and recovery: Database standards include protocols for regular data backup and effective recovery procedures.

- Replication and synchronization: Guidelines for data replication and synchronization ensure redundancy and disaster recovery readiness.

It will be vital to establish standards for each of these components of database management as new RNA modification repositories come on line. It is also essential that existing databases meet similar standards.

THE CURRENT STATE OF DATABASES

RNA modification databases are critical resources that provide valuable information on the chemical structure of modified RNAs, the location of modifications within RNA molecules, and the enzymes responsible for catalyzing the modification-related reactions. Some databases also include information on the functional implications of the modification, such as its effect on RNA stability, translation efficiency, or protein binding.

One of the most widely used RNA modification databases is Modomics, which is maintained by the International Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology in Poland (Boccaletto et al., 2022; Cappannini et al., 2024). Modomics provides information on more than 170 types of RNA modifications, including common modifications such as methylation, pseudouridylation, and adenosine-to-inosine editing, as well as rare modifications such as thiolation and wybutosine formation (Cappannini et al., 2024). The Modomics database includes detailed information on the enzymes responsible for catalyzing each modification, as well as the RNA sequences and structures that are prone to modification.

Another important RNA modification database is RMBase, which is maintained by Sun Yat-sen University in China (Qu Lab, n.d.; Xuan et al., 2024). RMBase includes information on 73 RNA modifications and provides tools for predicting the likelihood of modification at specific sites within RNA molecules. In addition, RMBase includes information on the functional implications of each modification, such as its effect on RNA structure or protein binding to other partners.

Other RNA modification databases include RNAmod, which is maintained by the University of Bern in Switzerland, and MODOMICS-EXPERT, which focuses on RNA modifications that have been implicated in human disease. These databases, along with many others, are critical resources for researchers working in the field of RNA biology, providing a repository of information on the various chemical modifications that occur on RNA molecules.

One of the key challenges in the field of RNA modifications is identifying and characterizing new modifications. Many RNA modifications are poorly understood, and new modifications are still being discovered. As a result, RNA modification databases need to be updated regularly and revised as new information becomes available, which can be laborious for those curating the databases.

In addition to serving as repositories of information on RNA modifications, these databases can be used to explore the functional implications of modifications. For example, researchers can use these databases to identify RNA modifications that are associated with specific diseases or physiological processes and to investigate the role of these modifications in regulating gene expression or other cellular processes.

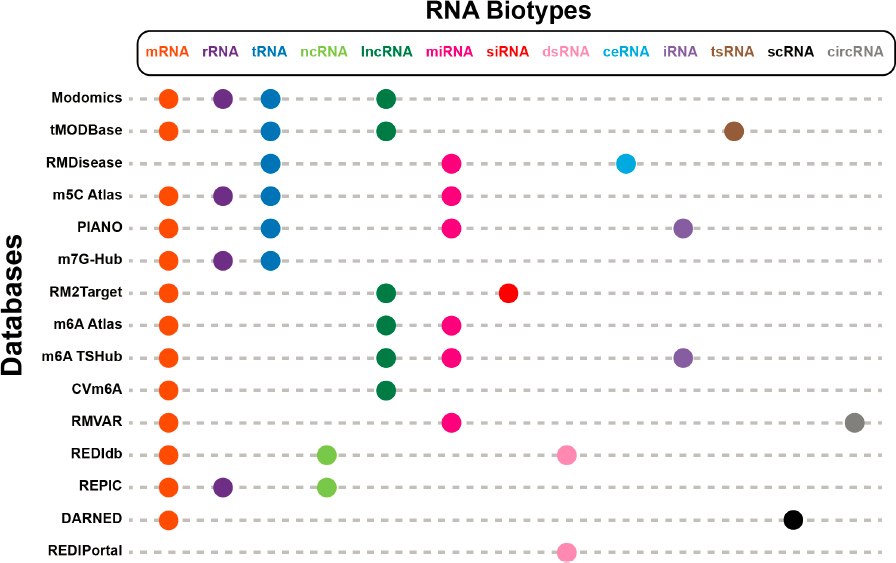

Numerous databases focus on specific modifications, predominantly m6A, ribose methylation, 5-methylcytosine, N1-methyladenosine, inosine, and pseudouridine. Table 4-1 lists several popular databases, including ones that cover RNA modifications broadly and those that focus on a single type of RNA modification. Table 4-1 describes the kind of data they contain, how many biological species are the sources of the RNA modifications, whether the data were experimentally determined or computationally derived, and the last known updated year.

The remainder of this section uses the databases in Table 4-1 to evaluate the organization and accessibility of information in RNA modification databases. Databases can be organized in a multitude of ways. Here, organization by species and RNA biotype is discussed. In addition, there is a discussion about how accessible the database information is for users. Such classifications are important because they facilitate the understanding of characteristics present within modified RNA nucleosides and enhance the use of databases.

TABLE 4-1 Databases for RNA Modifications

| Database | RNA Modification Data | Year of Last Update | Species Within the Database | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modomics | Contains data on modified ribonucleosides, their location within RNA, the biosynthetic pathways, and the RNA-modifying enzymes. Catalog of RNA modifications associated with human diseases. Contains 170 modifications. | 2024 | 50 species | computation, experiments |

| tMODBase | Collects modifications from transfer RNA (tRNA) exclusively. Gives visual data of the tRNA sequencing that identified the modifications. Contains 37 modifications. | 2023 | 11 species | computation |

| RM2Target | Hosts target associations for 63 writers, erasers, and readers. Shows these targets by binding, validation, and perturbation. Contains 9 modifications. | 2023 | human, mouse | experiments |

| RMDisease v2.0 | Includes RNA modification–associated variants, specifically those connected with disease. Integrates human genetic variants and experimentally modified sites to identify and label the associated modifications. Contains 16 types of modifications. | 2023 | 20 species | computation |

| RMVar | Annotates, visualizes, and explores N6-methyladenosine (m6A) and its modification sites. Includes known links between disease-related and m6A variants. | 2021 | human, mouse | computation, experiments |

| m6A Atlas v2.0 | Includes conservation of m6A sites, epitranscriptomes of virus species, and biological functions of m6A. Created to hold and organize m6A sites. | 2023 | 42 species | experiments |

| m6A-TSHub | Focuses on specific m6A methylation and genetic variants that could potentially regulate m6A epigenetic marks. Includes four major components: collections of m6A sites from human tissues and tumors, and separate components for prediction and assessment. | 2022 | human | experiments |

| REPIC | Focuses on the functional implications of modifications in the epitranscriptome. Collects data for studying posttranscriptional modifications and their impact on gene expression and cellular processes. | 2020 | 11 species | computation |

| CVm6A | Organizes and identifies the sites and peaks of m6A’s multitude of functions. Collects cell lines and maps all m6A peaks using gene annotation. Includes the peak region, strand, gene region and type, and enrichment score. | 2019 | human, mouse | computation |

| m5C-Atlas | Collects reliable sites for 5-methylcytosine, a well-known covalent modification, from single-base technologies using methylation sites from a variety of species. | 2022 | 13 species | computation, experiments |

| PIANO | A web server that identifies the site and function of pseudouridine modifications, the most abundant RNA modification of uridine. | 2020 | human | computation |

| Database | RNA Modification Data | Year of Last Update | Species Within the Database | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m7GHub V2.0 | Focuses on N7-methylguanosine (m7G) sites and how chemical modifications may affect the cell as a whole. Created to reveal the conservation, regulation, and translational control of m7G RNA modifications on various types of RNA. | 2023 | 23 species | experiments |

| REDIdb 3.0 | Created to explore RNA modifications in plant organelles. Aims to uncover the RNA editing changes within plant genomes. | 2018 | 281 species of plants | computation |

| REDIportal V2.0 | Created to explore the links between adenosine-to-inosine editing and human disorders, specializing in 55 body sites. Nonhuman collection began in 2021. | 2021 | human, mouse | computation |

| DARNED | A centralized resource for RNA editing events. Uses Wikipedia to facilitate curation efforts because of its convenience and popularity. | 2013 | human, mouse, fly | computation |

NOTES: Database details captured in November 2023.

SOURCES: Modomics (Cappannini et al., 2024); tMODBase (Lei et al., 2023); RM2Target (Bao et al., 2023); RMDisease v2.0 (Song et al., 2023); RMVar (Luo et al., 2021); m6A Atlas v2.0 (Tang et al., 2021); m6A-TSHub (Song et al., 2022); REPIC (Liu et al., 2020); CVm6A (Han et al., 2019); m5C-Atlas (Ma et al., 2022); PIANO (Song et al., 2020b); m7GHub V2.0 (Song et al., 2020a); REDIdb 3.0 (Lo Giudice, Pesole, and Picardi, 2018); REDIportal V2.0 (Mansi et al., 2021); DARNED (Kiran et al., 2013).

Species Information in a Database

The 15 databases in Table 4-1 contain information about RNA modification studies performed in a wide range of species, including Homo sapiens (human), Mus musculus (mouse), Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly), Caenorhabditis elegans (roundworm), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast), Escherichia coli (bacterium), Arabidopsis thaliana (mustard family plant), and many more. By cataloging and documenting the presence, location, and characteristics of RNA modifications across species, researchers gain insights into the modifications’ functional roles, evolution, and potential implications for cellular processes. Comparative analyses using the information in RNA modification databases help identify conserved modifications across species and can lead to the discovery of species-specific modifications, aiding the understanding of the intricate regulatory mechanisms involving RNA modifications.

RNA Biotypes in a Database

Biotype classification is a scheme for cataloging types of RNA, such as mRNA, microRNA, and long noncoding RNA. The databases in Table 4-1 encompass 13 biotypes (Figure 4-2), and 13 of the databases currently include modification data for mRNAs. Although these databases are prevalently used to research mRNA modifications and their functions, research on mRNA modifications is more recent than the study of modifications in tRNA and ribosomal RNA (rRNA). But the success of the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine has thrust mRNA and mRNA modifications research into the spotlight (Fang et al., 2022). Quite a few RNA biotypes are not studied as widely as are mRNA, tRNA, and rRNA. Prioritizing specific biotypes and modifications is an important consideration for the future; however, biotypes such as mRNA, tRNA, and long noncoding RNA have

such a wide range of functions in a cell that research into them is substantially more prevalent than other types of RNA (e.g., tRNA-derived small RNA, small interfering RNA, informational RNA, competing endogenous RNA).

Accessibility of Database Information

The databases listed in Table 4-1 are publicly accessible. Each plays a role in advancing research in RNA modifications by providing information about various RNA biotypes, modifications, functions, and links to diseases. Researchers and students can use these public resources to explore the field of RNA modifications and to gain a better understanding of the impact of RNA on cellular processes and health.

Publicly available databases play a pivotal role in promoting open access to knowledge and fostering collaboration. By making information freely available, they provide a platform for sharing research findings, data, and methodologies. While publicly available databases offer significant benefits, they do have downsides. Public or philanthropic funding is required to keep the database updated with the latest research results and practical user tools. When databases are not kept current, researchers may inadvertently use outdated information, wasting precious resources and time on experiments and analyses based on flawed premises.

MAJOR CHALLENGES AND SCIENTIFIC GAPS

Physical Standards

Modified Nucleosides and Nucleotides

As discussed previously in this chapter, developing new technologies for sequencing RNA and its modifications will depend heavily on the availability of physical standards. Given the paucity of commercially available modified RNA nucleosides and the fact that most are not available in a form compatible with existing solid-phase synthesis schemes, there is a need to prioritize making physical standards for RNA modifications available, ensuring that all interested parties have access through a commercial or nonprofit resource. Furthermore, efforts to create appropriate phosphoramidites or nucleotide triphosphate versions of these standards would accelerate their incorporation into oligonucleotides or RNA sequences generated via chemical synthesis or enzymatic synthesis, respectively.

Modified Oligonucleotides

The field will benefit from a collection of oligonucleotide standards of varying length and composition for use as reference materials when evaluating existing technologies and newly developed methods. These standards would incorporate common RNA modifications into sequence contexts for developing new RNA sequencing technologies, serve as appropriate scientific controls for validating existing approaches, enable measurement of the effectiveness of RNA isolation and purification protocols, and potentially enable absolute quantification of site-specific RNA modifications. Standards need to cover a range of site-specific modification stoichiometry (from fully unmodified to fully modified) to ensure their utility in both qualitative and quantitative applications.

By making such a set of modified RNA reference materials available, independent and even blind testing can be performed to ensure that any RNA sequencing technology focused on identifying and quantifying modified nucleotides meets its final claims. These reference materials could also serve as instrument calibration standards or suitable references for new assay development. These standards could also be used to improve and identify best practices in data analysis pipelines. Although the functional contexts for many modifications are yet to be discovered, technology developments can occur in parallel with advances in understanding of the biological significance of these modifications.

Biological and Biochemical Standards

Antibodies that recognize specific RNA modifications have been instrumental tools for transcriptome-wide mapping studies. However, in some cases these antibodies have been shown to cross-react with multiple modifications, resulting in discrepancies in the literature and inconsistencies across studies regarding the location of RNA modifications of interest. Although multiple sources of antibody production have helped to drive healthy competition among companies, antibodies must be properly validated to ensure that they are indeed specific to the indicated modification. By establishing gold standard practices for antibody validation and universally recognized best practices, antibody-based tools will be improved and inaccurate dataset generation can be reduced. Such standard practices may include biochemical validation assays (such as competitor assays using synthetic modified oligonucleotides), as well as confirmation of loss of antibody signal using RNA isolated from cells or other biological systems in which modification-specific writer enzymes have been depleted or enzymatically inhibited.

Data Standards

Defining the data quality that provides solid evidence for the presence of RNA modifications remains a significant challenge. Ensuring that the raw data generated by any RNA sequencing technology is available to other interested parties via acceptable portals would improve experimental rigor and reproducibility and enable new technology developments, such as improved basecalling or modification mapping algorithms, to be applied to previously published datasets. The field would benefit if publishers required the deposition of raw data in nonproprietary formats and via hosting platforms that are freely accessible. With both existing and anticipated technologies for sequencing RNA and its modifications, there is a major need to ensure consistent naming of modifications and sequence annotation so that reported data can be verified readily between different technologies. Learning from other fields (e.g., the flow cytometry standard [*.fcs] format) could inform approaches to creating consistent nomenclature and data reporting conventions. Ideally, whether it is done through a U.S. or international consortium model or via an appropriate scientific organization, the conventions for naming modifications, formatting modified nucleosides in data elements, and defining specific sequence locations and the relative stoichiometry of modifications needs to be established, and established in a manner that enables the information to be ported easily into existing and new databases while also being available to any interested party via commercial or noncommercial sites.

RNA Databases and Infrastructure

Several existing databases curate results from experimental and computational studies on RNA modifications (Table 4-1). However, the epitranscriptomics field currently lacks a one-stop data resource (or ensemble of databases) that is sustainably funded and sufficiently staffed to ensure that repositories are up to date with both RNA modifications data and the latest versions of user tools. Such a resource needs to be publicly accessible, and ideally, centrally administered by a public or nonprofit entity.

Before such a resource is established, existing databases need financial and technical support. For example, Modomics remains one of the best and most widely cited databases of modified nucleosides, but this resource is outside of the United States and is driven by the passion of its creators. It would be valuable to establish mirror server sites in the United States to ensure the long-term survivability and sustainability of this database. Another model resource for RNA biology is RNA Central,4 which curates information on noncoding RNAs from multiple databases, although it does not focus on RNA modifications. It is currently supported technically by the European Molecular Biology Laboratory’s European Bioinformatics Institute with funding from the Wellcome Trust. It would be valuable for a U.S. entity, such as the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI),5 to join in supporting, sustaining, and growing the capabilities of this or similar resources that can stand as a one-stop portal for RNA biology. The epitranscriptomics field would benefit from access to a centralized resource that captures information about RNA modifications, their locations on individual RNA isoforms, and associated biological pathways, as well as user tools.

Beyond ensuring the long-term sustainability of databases housing information on RNA and its modifications, gaps need to be addressed where databases do not yet align with FAIR principles. Data integrity challenges can be addressed via standardization of protocols and adherence to physical, biological, and data standards. A challenge will be ensuring the data format and database

___________________

4 See https://rnacentral.org (accessed November 14, 2023).

5 NCBI is a division within the National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health. NCBI is “a national resource for molecular biology information”; its mission is to “to develop new information technologies to aid in the understanding of fundamental molecular and genetic processes that control health and disease” (NCBI, n.d., para. 3).

standards described above are being followed to enable data portability among various databases and to enhance the communication of data for the end user. Ideally these databases would integrate information related to RNA sequence, modification site(s), stoichiometry, and genome/DNA linkage (where appropriate) so that the end user has direct access to this key information in an easy-to-use and shareable format.

Overall, the most pressing challenges are staying current with rapid technological advancements, balancing standardized practices with vendor-specific features from various instruments, and addressing the complexity of implementation. To meet these challenges, database standards need to adapt to emerging and future trends in biomedicine, artificial intelligence, and machine learning, in order to shape the future of data management for storing, distributing, and visualizing RNA modification datasets.

CONCLUSIONS

Conclusion 4–1: Although synthetic or biological routes exist for generating several modified nucleoside and RNA standards, few commercial or nonprofit sources of these physical standards are available to researchers. The current lack of market forces supporting the creation of such standards at scale reinforces the need for federal involvement and leadership.

Conclusion 4–2: Data standards suffer from a lack of coherent or systematic nomenclature for representing a modified nucleoside within an overall RNA sequence. Clear guidance and standardization of RNA nomenclature would accelerate open access and sharing of information about RNA and its modifications.

Conclusion 4–3: The prevalence of “home-grown” small-group-supported RNA databases has been vital to advancing the field of RNA biology. Nonetheless, a major concern is the loss of resources (e.g., funding, staff) leading to a lack of maintenance of these lab-housed databases. Abandonment of carefully curated databases may limit scientific growth and understanding, and incur huge wastes of time, effort, and resources.

ROADMAP FOR DEVELOPING STANDARDS AND DATABASES

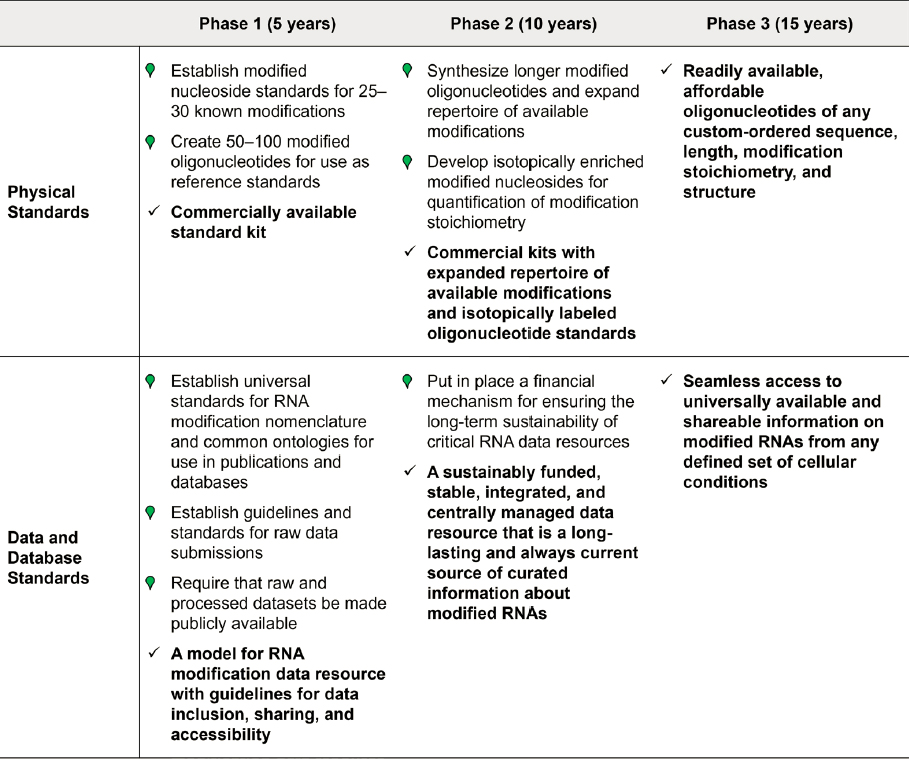

Within 5 years:

-

Physical standards:

- Establish modified nucleoside standards for 25–30 known modifications of biological significance and ensure that these are available to be used at scale.

- Create a suite of 50–100 modified oligonucleotides of known sequence and known modification stoichiometry for use as standards for evaluating the technical accuracy and reproducibility of instrumentation.

- Develop a commercially available standard kit that includes a suite of modified reference standards for nucleosides and oligonucleotides.

-

Data standards:

- Establish universal standards for RNA modification nomenclature and common ontologies for use in publications and databases.

- Establish standards and guidelines for submission of raw data to journals.

- Require that raw signal data and processed datasets be made publicly available through centrally managed databases.

-

Database standards:

- Collaborate with key public, private, and international groups to define standards necessary for developing and managing RNA modification databases and resources.

- Establish an agreed-upon model for RNA modification data resources with guidelines for data inclusion, sharing, and accessibility.

Within 10 years:

-

Physical standards:

- Partner with companies to synthesize longer modified oligonucleotides and expand repertoire of available modifications.

- Develop isotopically enriched versions of modified nucleosides for enhanced quantification of modification stoichiometry.

- Develop commercial kits with an expanded repertoire of available modifications and isotopically labeled oligonucleotide standards.

-

Database standards:

- Put in place a financial mechanism for ensuring the long-term sustainability of critical RNA databases.

- Promote a sustainably funded, stable, integrated, and centrally managed data resource that is a long-lasting and always-current source of curated information about modified RNAs.

Within 15 years:

- Readily available and affordable oligonucleotides of any custom-ordered sequence, length, modification stoichiometry, and structure.

- Seamless access to universally available and shareable information on all RNAs from any defined set of cellular conditions, their modification status, and their appropriate biological, medical, or other functional aspects. Ensure that repositories of this information are financially viable.

REFERENCES

Bao, X., Y. Zhang, H. Li, Y. Teng, L. Ma, Z. Chen, X. Luo, J. Zheng, A. Zhao, J. Ren, and Z. Zuo. 2023. “RM2Target: A comprehensive database for targets of writers, erasers and readers of RNA modifications.” Nucleic Acids Research 51 (D1): D269–D279. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac945.

Boccaletto, P., F. Stefaniak, A. Ray, A. Cappannini, S. Mukherjee, E. Purta, M. Kurkowska, N. Shirvanizadeh, E. Destefanis, P. Groza, G. Avşar, A. Romitelli, P. Pir, E. Dassi, S. G. Conticello, F. Aguilo, and J. M. Bujnicki. 2022. “MODOMICS: A database of RNA modification pathways. 2021 update.” Nucleic Acids Research 50 (D1): D231–D235. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab1083.

Cai, W. M., Y. H. Chionh, F. Hia, C. Gu, S. Kellner, M. E. McBee, C. S. Ng, Y. L. Pang, E. G. Prestwich, K. S. Lim, I. R. Babu, T. J. Begley, and P. C. Dedon. 2015. “A platform for discovery and quantification of modified ribonucleosides in RNA: Application to stress-induced reprogramming of tRNA modifications.” Methods in Enzymology 560: 29–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.mie.2015.03.004.

Cantara, W. A., P. F. Crain, J. Rozenski, J. A. McCloskey, K. A. Harris, X. Zhang, F. A. Vendeix, D. Fabris, and P. F. Agris. 2011. “The RNA Modification Database, RNAMDB: 2011 update.” Nucleic Acids Research 39 (suppl_1): D195–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq1028.

Cappannini, A., A. Ray, E. Purta, S. Mukherjee, P. Boccaletto, S. N. Moafinejad, A. Lechner, C. Barchet, Bruno P. Klaholz, F. Stefaniak, and J. M. Bujnicki. 2024. “MODOMICS: a database of RNA modifications and related information. 2023 update.” Nucleic Acids Research 52 (D1): D239–D244. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad1083.

Crain, P. F. 1990. “Preparation and enzymatic hydrolysis of DNA and RNA for mass spectrometry.” Methods in Enzymology 193: 782–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/0076-6879(90)93450-y.

D’Ascenzo, L., A. M. Popova, S. Abernathy, K. Sheng, P. A. Limbach, and J. R. Williamson. 2022. “Pytheas: A software package for the automated analysis of RNA sequences and modifications via tandem mass spectrometry.” Nature Communications 13 (1): 2424. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30057-5.

Fang, E., X. Liu, M. Li, Z. Zhang, L. Song, B. Zhu, X. Wu, J. Liu, D. Zhao, and Y. Li. 2022. “Advances in COVID-19 mRNA vaccine development.” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 7 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-00950-y.

FEDR (Federal Enterprise Data Resources). “Data standards: Concepts & definitions.” Developed by the Office of Management and Budget, Office of Government Information Services of the National Archives, and General Services Administration. https://resources.data.gov/standards/concepts/ (accessed October 12, 2023).

Han, Y., J. Feng, L. Xia, X. Dong, X. Zhang, S. Zhang, Y. Miao, Q. Xu, S. Xiao, Z. Zuo, L. Xia, and C. He. 2019. “CVm6A: A visualization and exploration database for m6As in cell lines.” Cells 8 (2): 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8020168.

Jora, M., K. Borland, S. Abernathy, R. Zhao, M. Kelley, S. Kellner, B. Addepalli, and P. A. Limbach. 2021. “Chemical amination/imination of carbonothiolated nucleosides during RNA hydrolysis.” Angewandte Chemie International Edition 60 (8): 3961–3966. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202010793.

Jumper, J., R. Evans, A. Pritzel, T. Green, M. Figurnov, O. Ronneberger, K. Tunyasuvunakool, R. Bates, A. Žídek, A. Potapenko, A. Bridgland, C. Meyer, S. A. A. Kohl, A. J. Ballard, A. Cowie, B. Romera-Paredes, S. Nikolov, R. Jain, J. Adler, T. Back, S. Petersen, D. Reiman, E. Clancy, M. Zielinski, M. Steinegger, M. Pacholska, T. Berghammer, S. Bodenstein, D. Silver, O. Vinyals, A. W. Senior, K. Kavukcuoglu, P. Kohli, and D. Hassabis. 2021. “Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold.” Nature 596 (7873): 583–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2.

Kaiser, S., S. R. Byrne, G. Ammann, P. Asadi Atoi, K. Borland, R. Brecheisen, M. S. DeMott, T. Gehrke, F. Hagelskamp, M. Heiss, Y. Yoluç, L. Liu, Q. Zhang, P. C. Dedon, B. Cao, and S. Kellner. 2021. “Strategies to avoid artifacts in mass spectrometry-based epitranscriptome analyses.” Angewandte Chemie International Edition 60 (44): 23885–23893. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202106215.

Kanwal, F., and C. Lu. 2019. “A review on native and denaturing purification methods for non-coding RNA (ncRNA).” Journal of Chromatography B 1120: 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2019.04.034.

Kiran, A. M., J. J. O’Mahony, K. Sanjeev, and P. V. Baranov. 2013. “Darned in 2013: Inclusion of model organisms and linking with Wikipedia.” Nucleic Acids Research 41 (D1): D258–D261. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks961.

Kong, Y., E. A. Mead, and G. Fang. 2023. “Navigating the pitfalls of mapping DNA and RNA modifications.” Nature Reviews Genetics 24 (6): 363–381. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-022-00559-5.

Koonchanok, R., S. V. Daulatabad, K. Reda, and S. C. Janga. 2023. “Sequoia: A framework for visual analysis of RNA modifications from direct RNA sequencing data.” Methods in Molecular Biology 2624: 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2962-8_9.

Lecun, Y., L. Bottou, Y. Bengio, and P. Haffner. 1998. “Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition.” Proceedings of the IEEE 86 (11): 2278–2324. https://doi.org/10.1109/5.726791.

Lei, H. T., Z. H. Wang, B. Li, Y. Sun, S. Q. Mei, J. H. Yang, L. H. Qu, and L. L. Zheng. 2023. “tModBase: Deciphering the landscape of tRNA modifications and their dynamic changes from epitranscriptome data.” Nucleic Acids Research 51 (D1): D315–D327. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1087.

Lemsara, A., C. Dieterich, and I. S. Naarmann-de Vries. 2023. “Mapping of RNA modifications by direct nanopore sequencing and JACUSA2.” Methods in Molecular Biology 2624: 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2962-8_16.

Limbach, P. A., P. F. Crain, and J. A. McCloskey. 1994. “Summary: The modified nucleosides of RNA.” Nucleic Acids Research 22 (12): 2183–2196. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/22.12.2183.

Liu, C., H. Sun, Y. Yi, W. Shen, K. Li, Y. Xiao, F. Li, Y. Li, Y. Hou, B. Lu, W. Liu, H. Meng, J. Peng, C. Yi, and J. Wang. 2023. “Absolute quantification of single-base m6A methylation in the mammalian transcriptome using GLORI.” Nature Biotechnology 41 (3): 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01487-9.

Liu, S., A. Zhu, C. He, and M. Chen. 2020. “REPIC: A database for exploring the N6-methyladenosine methylome.” Genome Biology 21 (1): 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02012-4.

Lo Giudice, C., G. Pesole, and E. Picardi. 2018. “REDIdb 3.0: A comprehensive collection of RNA editing events in plant organellar genomes.” Frontiers in Plant Science 9: 482. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00482.

Luo, X., H. Li, J. Liang, Q. Zhao, Y. Xie, J. Ren, and Z. Zuo. 2021. “RMVar: An updated database of functional variants involved in RNA modifications.” Nucleic Acids Research 49 (D1): D1405–D1412. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa811.

Ma, J., B. Song, Z. Wei, D. Huang, Y. Zhang, J. Su, J. P. de Magalhães, D. J. Rigden, J. Meng, and K. Chen. 2022. “m5C-Atlas: A comprehensive database for decoding and annotating the 5-methylcytosine (m5C) epitranscriptome.” Nucleic Acids Research 50 (D1): D196–D203. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab1075.

Machnicka, M. A., A. Olchowik, H. Grosjean, and J. M. Bujnicki. 2014. “Distribution and frequencies of post-transcriptional modifications in tRNAs.” RNA Biology 11 (12): 1619–1629. https://doi.org/10.4161/15476286.2014.992273.

Mansi, L., M. A. Tangaro, C. Lo Giudice, T. Flati, E. Kopel, A. A. Schaffer, T. Castrignanò, G. Chillemi, G. Pesole, and E. Picardi. 2021. “REDIportal: Millions of novel A-to-I RNA editing events from thousands of RNAseq experiments.” Nucleic Acids Research 49 (D1): D1012–D1019. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa916.

Matuszewski, M., J. Wojciechowski, K. Miyauchi, Z. Gdaniec, W. M. Wolf, T. Suzuki, and E. Sochacka. 2017. “A hydantoin isoform of cyclic N6–threonylcarbamoyladenosine (ct6A) is present in tRNAs.” Nucleic Acids Research 45 (4): 2137–2149. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw1189.

Motorin, Y., and V. Marchand. 2021. “Analysis of RNA modifications by second- and third-generation deep sequencing: 2020 update.” Genes 12 (2): 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12020278.

Mullegama, S. V., M. O. Alberti, C. Au, Y. Li, T. Toy, V. Tomasian, and R. R. Xian. 2019. “Nucleic acid extraction from human biological samples.” Methods in Molecular Biology 1897. In Biobanking, edited by Yong, W. New York: Humana Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-8935-5_30.

NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information). n.d. “Our mission.” National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/home/about/mission (accessed November 14, 2023).

Nelson, A. 2022. Memorandum for the heads of executive departments and agencies. Developed by the Office of Science and Technology Policy. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/08-2022-OSTP-Public-access-Memo.pdf (accessed March 11, 2024).

Nilsen, T. W. 2013. “The fundamentals of RNA purification.” Cold Spring Harbor Protocols 2013. Adapted from RNA: A laboratory manual, by D. C. Rio, M. Ares Jr, G. J. Hannon, and T. W. Nilsen. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: CSHL Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.top075838.

NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). 2016. “NIST monoclonal antibody reference material 8671.” Last modified September 15, 2023. https://www.nist.gov/programs-projects/nist-monoclonal-antibody-reference-material-8671 (accessed October 4, 2023.).

Qu Lab. n.d. “RMBase v3.0.” School of Life Science, Sun Yat-sen University, China. https://rna.sysu.edu.cn/rmbase3/ (accessed January 31, 2024).

Sample, P. J., K. W. Gaston, J. D. Alfonzo, and P. A. Limbach. 2015. “RoboOligo: Software for mass spectrometry data to support manual and de novo sequencing of post-transcriptionally modified ribonucleic acids.” Nucleic Acids Research 43 (10): E64. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv145.

Song, B., D. Huang, Y. Zhang, Z. Wei, J. Su, J. Pedro de Magalhães, D. J. Rigden, J. Meng, and K. Chen. 2022. “m6ATSHub: Unveiling the context-specific m6A methylation and m6A-affecting mutations in 23 human tissues.” Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 21 (4): 678–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2022.09.001.

Song, B., Y. Tang, K. Chen, Z. Wei, R. Rong, Z. Lu, J. Su, J. P. de Magalhães, D. J. Rigden, and J. Meng. 2020a. “m7GHub: Deciphering the location, regulation and pathogenesis of internal mRNA N7-methylguanosine (m7G) sites in human.” Bioinformatics 36 (11): 3528–3536. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa178.

Song, B., Y. Tang, Z. Wei, G. Liu, J. Su, J. Meng, and K. Chen. 2020b. “PIANO: A web server for pseudouridine-site (Ψ) identification and functional annotation.” Frontiers in Genetics 11: 88. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.00088.

Song, B., X. Wang, Z. Liang, J. Ma, D. Huang, Y. Wang, J. P. de Magalhães, D. J. Rigden, J. Meng, G. Liu, K. Chen, and Z. Wei. 2023. “RMDisease V2.0: An updated database of genetic variants that affect RNA modifications with disease and trait implication.” Nucleic Acids Research 51 (D1): D1388–D1396. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac750.

Springer Nature. n.d. “Data repository guidance.” Scientific data. https://www.nature.com/sdata/policies/repositories#omics (accessed October 12, 2023).

Svetlov, V., and I. Artsimovitch. 2015. “Purification of bacterial RNA polymerase: Tools and protocols.” In Bacterial Transcriptional Control: Methods and Protocols, edited by I. Artsimovitch and T. J. Santangelo, 13–29. New York: Springer New York.

Tang, Y., K. Chen, B. Song, J. Ma, X. Wu, Q. Xu, Z. Wei, J. Su, G. Liu, R. Rong, Z. Lu, João P. de Magalhães, D. J. Rigden, and J. Meng. 2021. “m6A-Atlas: A comprehensive knowledgebase for unraveling the N6-methyladenosine (m6A) epitranscriptome.” Nucleic Acids Research 49 (D1): D134–D143. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa692.

Tardu, M., J. D. Jones, R. T. Kennedy, Q. Lin, and K. S. Koutmou. 2019. “Identification and quantification of modified nucleosides in saccharomyces cerevisiae mRNAs.” ACS Chemical Biology 14 (7): 1403–1409. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschembio.9b00369.

Thüring, K., K. Schmid, P. Keller, and M. Helm. 2016. “Analysis of RNA modifications by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.” Methods 107: 48-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.03.019.

Ueda, H., B. Dasgupta, and B. Y. Yu. 2023. “RNA modification detection using nanopore direct RNA sequencing and nanoDoc2.” Methods in Molecular Biology 2632: 299–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2996-3_21.

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). “Recommendation on open science.” 2023. Last modified September 21st, 2023. https://www.unesco.org/en/open-science/about (accessed October 4, 2023).

Varadi, M., D. Bertoni, P. Magana, U. Paramval, I. Pidruchna, M. Radhakrishnan, M. Tsenkov, S. Nair, M. Mirdita, J. Yeo, O. Kovalevskiy, K. Tunyasuvunakool, A. Laydon, A. Žídek, H. Tomlinson, D. Hariharan, J. Abrahamson, T. Green, J. Jumper, E. Birney, M. Steinegger, D. Hassabis, and S. Velankar. 2023. “AlphaFold Protein Structure Database in 2024: Providing structure coverage for over 214 million protein sequences.” Nucleic Acids Research 52 (D1): D368-D375. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad1011.

Walker, S. E., and J. Lorsch. 2013. “Chapter nineteen - RNA purification–precipitation methods.” Methods in Enzymology 530: 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-420037-1.00019-1

Wang, Y., M.–Hayatsu, and T. Fujii. 2012. “Extraction of bacterial RNA from soil: Challenges and solutions.” Microbes and Environments 27 (2): 111–1121. https://doi.org/10.1264/jsme2.me11304.

Wein, S., B. Andrews, T. Sachsenberg, H. Santos-Rosa, O. Kohlbacher, T. Kouzarides, B. A. Garcia, and H. Weisser. 2020. “A computational platform for high-throughput analysis of RNA sequences and modifications by mass spectrometry.” Nature Communications 11 (1): 926. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14665-7.

Wiener, D., and S. Schwartz. 2021. “The epitranscriptome beyond m6A.” Nature Reviews Genetics 22 (2): 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-020-00295-8.

Wilkinson, M. D., M. Dumontier, I. J. Aalbersberg, G. Appleton, M. Axton, A. Baak, N. Blomberg, J.-W. Boiten, L. B. da Silva Santos, P. E. Bourne, J. Bouwman, A. J. Brookes, T. Clark, M. Crosas, I. Dillo, O. Dumon, S. Edmunds, C. T. Evelo, R. Finkers, A. Gonzalez-Beltran, A. J. G. Gray, P. Groth, C. Goble, J. S. Grethe, J. Heringa, P. A. C. ‘t Hoen, R. Hooft, T. Kuhn, R. Kok, J. Kok, S. J. Lusher, M. E. Martone, A. Mons, A. L. Packer, B. Persson, P. Rocca-Serra, M. Roos, R. van Schaik, S.-A. Sansone, E. Schultes, T. Sengstag, T. Slater, G. Strawn, M. A. Swertz, M. Thompson, J. van der Lei, E. van Mulligen, J. Velterop, A. Waagmeester, P. Wittenburg, K. Wolstencroft, J. Zhao, and B. Mons. 2016. “The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship.” Scientific Data 3 (1): 160018. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18.

Wongsurawat, T., P. Jenjaroenpun, and I. Nookaew. 2022. “Direct sequencing of RNA and RNA modification identification using nanopore.” Methods in Molecular Biology 2477: 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2257-5_5.

Xuan, J., L. Chen, Z. Chen, J. Pang, J. Huang, J. Lin, L. Zheng, B. Li, L. Qu, and J. Yang. 2023. “RMBase v3.0: Decode the landscape, mechanisms and functions of RNA modifications.” Nucleic Acids Research 52 (D1): D273–D284. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad1070.

Xue, C., Y. Zhao, and L. Li. 2020. “Advances in RNA cytosine-5 methylation: Detection, regulatory mechanisms, biological functions and links to cancer.” Biomarker Research 8 (1): 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-020-00225-0.

Yu, N., P. A. Lobue, X. Cao, and P. A. Limbach. 2017. “RNAModMapper: RNA modification mapping software for analysis of liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry data.” Analytical Chemistry 89 (20): 10744–10752. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01780.