Charting a Future for Sequencing RNA and Its Modifications: A New Era for Biology and Medicine (2024)

Chapter: 3 Current and Emerging Tools and Technologies for Studying RNA Modifications

3

Current and Emerging Tools and Technologies for Studying RNA Modifications

To understand more fully the role of RNA and its modifications in living systems, researchers will need robust, reproducible, and accessible tools and techniques capable of identifying all RNA modifications, determining their stoichiometry, and elucidating crosstalk (i.e., dependencies) among modification sites. Ideally, this would be accomplished end to end for each RNA molecule in a sample, in a single experiment, and eventually at the single-cell level (Kadumuri and Janga, 2018). Although methods currently exist for measuring global modification levels, and other technologies are in use for sequencing RNA, including some of its modifications, multiple technical limitations and experimental challenges hamper researchers from accomplishing the grander goals listed above. Achieving these goals will require technological advances in the development of reagents, instruments, tools, and technologies for studying RNA modifications.

This chapter presents a summary of available techniques for identifying, quantifying, and sequencing RNA and its modifications, along with current computational and modeling tools used to analyze results. In addition, the chapter identifies technical limitations and challenges that researchers will have to overcome to understand fully the complex and diverse roles of RNA and its modifications in living systems. The chapter closes with some emerging opportunities to advance technologies that could offer new avenues for RNA sequencing endeavors.

CURRENT APPROACHES FOR STUDYING RNA MODIFICATIONS

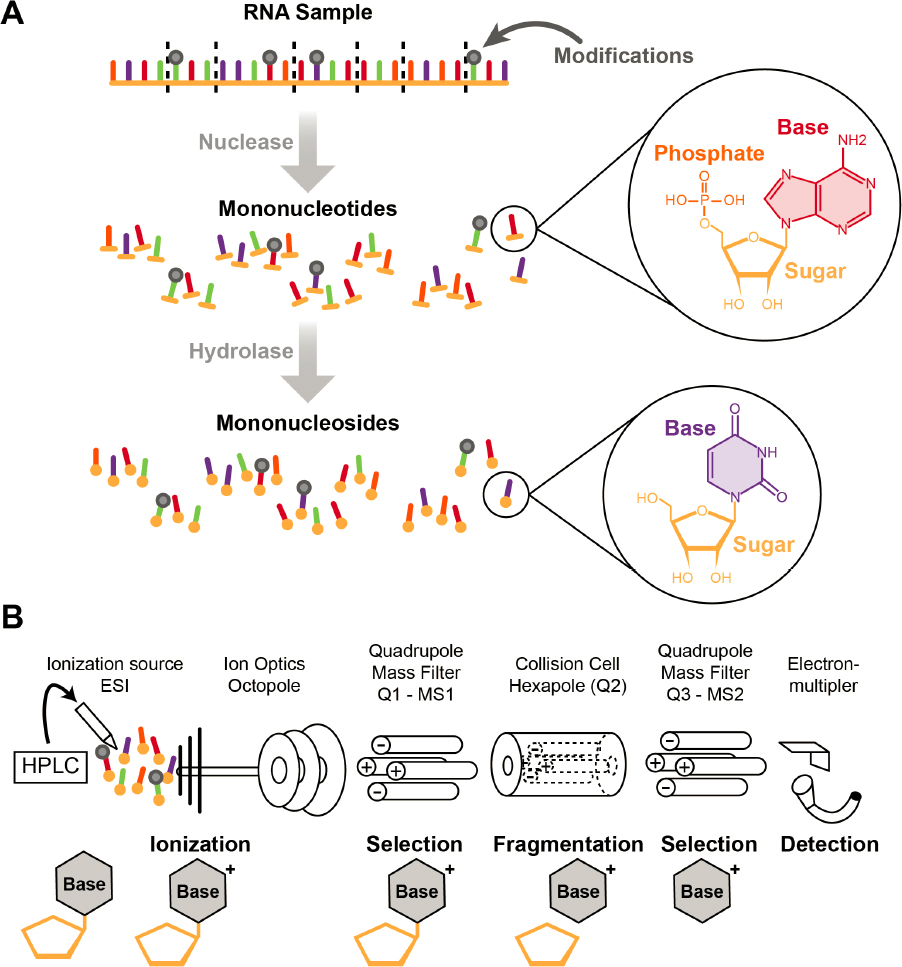

The presence of modified nucleotides in RNA has been recognized since shortly after RNA was discovered (Davis and Allen, 1957). Complete digestion of different species of RNA, such as transfer RNA (tRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), or messenger RNA (mRNA), to mononucleotides or mononucleosides, followed by thin-layer chromatography or high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), revealed the identity and levels of a variety of modifications (Kellner, Burhenne, and Helm, 2010). LC-MS/MS is now the most widely used platform for measuring global modification levels from cells and tissues from different organisms. Any

novel modification can be captured and characterized using these approaches. However, by digesting RNA to mononucleotides or mononucleosides, the sequence context of modifications is lost.

To identify the location and levels of RNA modification at precise coordinates, indirect sequencing approaches1 tailored for measuring individual modifications have been developed. Although informative, these indirect sequencing techniques suffer from several limitations. For example, only a minor portion of the more than 170 modifications are amenable to these currently available approaches (as seen in Table 3-1). Further, in most cases it is not possible to monitor multiple types of modifications in a single experiment using these indirect sequencing techniques, and thus they cannot reveal information about crosstalk between modifications. Finally, indirect sequencing approaches typically require considerable input material and are therefore difficult to adapt to single-cell analysis, which requires very high sensitivity.

As an alternative, direct sequencing2 of RNA molecules—either using mass spectrometry or dedicated methods, such as nanopore sequencing—to reveal the entire RNA sequence, including modifications, hold promise for solving these issues in the near to medium term, once problems such as sequencing length, basecalling, and precision are solved.

Global Modification Measurement

Global modification measurement refers to the process of digesting an RNA sample into its monomer components, which are then separated, analyzed, and identified. In almost all cases, the monomer components are mononucleosides (base + ribose sugar) or mononucleotides (base + ribose sugar + phosphate) (3-1A). Nucleases are most often used for digesting RNA into its monomers. For methods that implement two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography (2D-TLC), digested RNA is typically radiolabeled with phosphorous-32 to permit detection and quantification of the modified nucleotides following the separation step. Then, 2D-TLC is used to separate the different nucleotides and modified nucleotides based on the rates at which they move through the cellulose-coated milieu of the chromatography plates bathed one at a time in two solvents (Grosjean, Keith, and Droogmans, 2004). 2D-TLC reference maps have been compiled for several solvent systems, and these can be used to confirm the identity of the modified mononucleotide (Grosjean, Keith, and Droogmans, 2004; Gupta and Randerath, 1979; Kellner, Burhenne, and Helm, 2010; Stanley and Vassilenko, 1978). When the identity of a modified nucleotide is uncertain, an authentic standard is run on the chromatography plate alongside the sample. Comigration of the standard and a spot from the sample is often the determinant of a positive identification. Modification levels can be quantified based on the level of radioactivity measured upon X-ray film exposure or by phosphor imaging.

While 2D-TLC is fairly simple to implement, the use of radioactive materials is a drawback. A more significant problem is that modifications are identified through inference—that is, by comparing the final migration location on the plate of a sample spot to prior, known mononucleotide migration locations. For those reasons, 2D-TLC has been supplanted by LC-MS/MS, which has become the gold standard for the detection, characterization, and quantification of modified nucleosides (Deng et al., 2022; Heiss et al., 2021; Jora et al., 2019 ; Kellner, Burhenne, and Helm, 2010; Sarkar et al., 2021; Thüring et al., 2016).

The general approach when using LC-MS/MS involves digesting RNA into its constituent nucleosides via enzymatic hydrolysis (Figure 3-1A). As shown in Figure 3-1B, the nucleosides are next subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), which separates the molecules based on their polarity. As the separated nucleosides exit the chromatography column, they are

___________________

1 Indirect sequencing refers to methods for sequencing RNA and its modifications that require pretreatment of the RNA with enzymes or chemicals, or conversion to complementary DNA, prior to sequencing.

2 Direct sequencing refers to methods for generating information about an RNA’s sequence and modifications by direct analysis of the RNA.

NOTES: (A) The digestion of RNA into mononucleotides (which can be postlabeled for two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography) and mononucleosides. (B) Overview of LC-MS/MS for global analysis of modified nucleosides. A mixture of nucleosides (both modified and unmodified) is separated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), ionized by electrospray ionization (ESI), and then detected by mass spectrometry. Charged modified nucleosides can be selected and fragmented. Those products, typically the charged nucleobases, are then detected.

SOURCE: Yoluç, 2021. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License.

converted to gas-phase ions via electrospray ionization. These gas-phase ions are separated in a mass spectrometer based on their mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio. In tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), a particular m/z value is isolated and then dissociated (or fragmented), often via collisions with a neutral inert gas, to generate characteristic product (fragment) ions that can be used to define the molecular structure of the modified nucleoside.

Modified nucleosides are usually identified by three characteristics: the m/z value of the nucleoside, the m/z value(s) of any product ions generated during MS/MS, and the chromatographic retention time. Because nucleoside fragmentation during mass spectrometry typically results in loss of the neutral ribose sugar, the MS/MS step can be used to differentiate between methylations on the nucleobase from those at the 2'-hydroxyl position of the sugar. Moreover, because of this fragmentation behavior, neutral-loss scans can be performed across the entire HPLC elution window to look for m/z values that contain ribose and methylated ribose. These scans provide a routine approach for detecting modified nucleosides. For quantifying modified nucleosides, standard analytical methods can be used (Huang et al., 2023), although calibration curves typically require the presence of modified nucleoside standards, which, as discussed in Chapter 4, are not commercially available for all modified nucleosides.

While modern mass spectrometry platforms are quite sensitive, the amount of sample required for global analysis often depends on the initial complexity of the mixture—that is, how many different RNA species are in the mixture and the abundance of each species. For pure, isolated (single) RNA species, as little as 100 ng of sample can be used; however, if previously unknown modified nucleosides are detected during the analysis, additional sample is required for complete characterization (Clark, Rubakhin, and Sweedler, 2021; Kimura, Dedon, and Waldor, 2020). For more complex mixtures of RNA, global analyses—especially for absolute quantification of modification levels—require µg levels of RNA to start and require the presence of authentic standards for external or internal calibration of the response level of the modification.

One significant problem with LC-MS/MS arises from the process of ionizing the mononucleosides. Typically, electrospray ionization is used, but the effectiveness of this method depends heavily on the polarity of the molecule. More polar molecules are more easily ionized, and less polar molecules generate reduced ion currents. Thus, some modified nucleosides can be ionized and detected readily, even when they are present in the sample at relatively low levels, simply because of their enhanced ionization efficiency. However, less polar molecules may not be detected by this approach unless they are present in significant levels. One approach to addressing this challenge is to derivatize the sample in some fashion to create a more uniform ionization efficiency for all components (Dai et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2022). Another approach is to incorporate a stable isotope, which can then be used to better define the molecular formula that matches the detected precursor and product ions during MS/MS (Cheng et al., 2021; Heiss, Reichle, and Kellner, 2017; Kellner et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2023).

The HPLC step in an LC-MS/MS analysis can also limit the detection of known modifications or discovery of new modifications. Challenges can occur when modified nucleosides co-elute, especially when a modification present at low levels elutes with or close to one of the canonical nucleosides or a high-abundance modification. In such cases, deconvoluting two co-eluting modified nucleosides can be challenging without additional experimental manipulations during the MS/MS step (Janssen et al., 2022; Jora et al., 2018). While modifying the chromatographic conditions may help to resolve the co-eluting nucleosides (Cheng et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2022; Si-Hung, Causon, and Hann, 2017), such changes can result in “new” retention times, necessitating standards for verifying the presence of a particular modification. For these reasons, several investigators have focused on characterizing modifications following separation by alternative methods (Kenderdine et al., 2020) or by developing approaches that do not rely on the chromatographic retention time for identifying the modification (Jora et al., 2022).

Despite the challenges and limitations described above, LC-MS/MS is very effective at routinely providing the complete census of modified RNA nucleosides present in any sample (Kimura, Srisuknimit, and Waldor, 2020; McCown et al., 2020). Moreover, this approach is absolutely necessary when reporting the identity of a new modification (Borek, Reichle, and Kellner, 2020; Dal Magro et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2017; Kimura, Dedon, and Waldor, 2020; Yu et al., 2019).

At the same time, several recent reports document how sample handling and preparation steps prior to global analysis by LC-MS/MS can lead to artifacts that are incorrectly reported as new modifications or can change the chemical structure of the actual modification (Cai et al., 2015; Jora et al., 2021; Kaiser et al., 2021; Matuszewski et al., 2017). These recent reports also demonstrate the need in the field to better define and standardize appropriate sample isolation, preparation, and handling methods for global analyses. Further, while several LC-MS/MS approaches have been reported, the field lacks a set of consensus criteria that must be met before confidently reporting the presence of a new modification. Without such criteria, the field risks spending time and resources following up on artifacts or other experimental errors (Kaiser et al., 2021).

Global RNA modifications measurement can be improved by developing methods that require less sample input, enable higher confidence and accuracy in identifying and quantifying modifications, and make experimental protocols accessible to contract research organizations and core labs; these objectives represent key milestones to achieving the goals of this report.

Indirect Sequencing

Currently, available technology for indirect sequencing methods uses a reverse transcriptase enzyme to transcribe RNA molecules to complementary DNA (cDNA), followed by sequencing of the cDNA. During analysis of the cDNA sequence, the template RNA base sequence (adenine [A], cytosine [C], guanine [G], uracil [U]), and sometimes, additional information about modified nucleotides, is derived. However, many RNA modifications become invisible during the preparation of cDNA, and additional steps need to be taken prior to reverse transcription to reveal the positions of the modifications. In one strategy, RNA fragments containing the modification of interest are isolated using antibodies against the modification prior to cDNA preparation (e.g., RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing, cross-linking and immunoprecipitation sequencing). In a second approach, treatment of the RNA with chemicals or enzymes specifically marks the modified bases so that they can be recognized by reverse transcription and appear as a misincorporation/mutation, deletion, or stop signature in the cDNA (Table 3-1).

The hydrolytic deamination of adenosines in RNA to inosines (A-to-I) by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA (ADAR enzymes) was the first widespread modification identified in eukaryotic mRNA (Reich and Bass, 2019). Because, like guanosine (G), inosine prefers to pair with cytidine (C), inosine can be revealed easily, without any pretreatment, by identifying A-to-G transitions following reverse transcription and sequencing of cDNA (Reich and Bass, 2019).

While it took heroic efforts to detect RNA methylation, including N6-methyladenosine (m6A), in mRNA in the 1970s (Desrosiers, Friderici, and Rottman, 1974), in-depth characterization of m6A became possible once specific m6A antibodies were developed and used for immunoprecipitation of fragmented, m6A-modified RNA followed by next-generation sequencing (NGS) of the cDNA3 (Dominissini et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2012). In vitro crosslinking of m6A-modified RNA with m6A-specific antibodies further improved the resolution, permitting precise mapping of the modification sites (Ke et al., 2015; Linder et al., 2015). This precision mapping was possible because during the reverse transcription process, crosslinking-induced mutations were detectable in sequencing

___________________

3 Next-generation sequencing, often called NGS, refers to several high-throughput methods for sequencing DNA and indirectly RNA (by conversion of RNA to cDNA) (see Chapter 1 and Figure 1-6).

as the sites where modified bases had been in the original mRNA. This antibody approach was adapted to map potential N1-methyladenosine (Dominissini et al., 2016) and N4-acetylcytidine modification sites (Arango et al., 2018); resulting data suggest that both modifications play a role in the regulation of protein synthesis (Roberts, Porman, and Johnson, 2021).

Table 3-1 summarizes a multitude of indirect sequencing methods that incorporate either antibody enrichment or chemical/enzymatic reaction of modified RNA nucleotides, or in a few cases, alternative strategies. In general, modification mapping can involve either positive readout that detects the modification as a mutation, deletion, or stop signature in the sequencing data, or negative readout that detects the unmodified base. Examples include pseudouridine (Ψ) versus 5-methylcytosine (m5C) sequencing using bisulfite treatment, in which Ψ is read out through a deletion signature, m5C is read out as C, and unmodified Cs are read out as thymine (T).

Immunoprecipitation-based methods suffer from specificity issues, most often because the antibody has some degree of cross-reactivity with related nucleosides (Garcia-Campos et al., 2019; Grozhik et al., 2019). In addition, such methods do not allow for a quantitative assessment of modification levels at the identified sites. Alternative approaches exploit differential sensitivity of modified sites to ribonucleases (RNases) (MAZTER-seq, m6A-REF-seq; see Table 3-1); however, this works only for the few cases for which such nucleases exist. Some base modifications, including Ψ (Carlile et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2014), N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) (Sas-Chen et al., 2020), m5C, and m6A (Hu et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023), can be derivatized chemically or enzymatically to increase specificity (see Table 3-1). Typically, such derivatization can then be revealed after reverse transcription and sequencing, either as sites of stalling for reverse transcriptase or as reverse transcriptase–induced cDNA sequence variants, analogous to the identification of inosines in mRNA by A-to-G transitions in RNA-sequenced datasets (Roth, Levanon, and Eisenberg, 2019).

Indirect sequencing of modified RNA transcripts has several shortcomings. NGS methods yield RNA modification information from mutation, deletion, and stop signatures in reads aligned to reference sequences. These signatures are obtained during cDNA synthesis when the reverse transcriptase enzyme reacts to modified nucleotides, sometimes in unexpected ways. While these methods can identify and even quantify specific modifications at single-base resolution in each transcript, the information obtained is at the bulk-transcript level, not at the single-molecule level; thus, tissue- or cell-specific information is lost. Since most protocols involve an immunoprecipitation or derivatization designed to reveal only one modification, current NGS protocols typically reveal only the modification of interest and do not provide information on the interplay between different RNA modifications.

Third, NGS methods generate short reads of up to 300 nucleotides, which, on average, represent less than 15 percent of a mammalian mRNA transcript (Lander et al., 2001), thus precluding the assessment of long-range coordination of modification sites. The short-read length also complicates calling of splice isoform–specific or single transcript–specific modifications (see Figure 1-6). In addition, unavoidable false-positive calls confound data interpretation for technologies requiring chemical/enzymatic treatment or the use of antibodies, particularly for low-abundance modifications (Kong, Mead, and Fang, 2023). For example, chemical labeling of Ψ by N-cyclohexyl-N′-(2-morpholinoethyl)carbodiimide metho-p-toluenesulphonate (CMC) (Carlile et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2014) results in false positives due to nonspecific labeling at sites other than Ψ (Wiener and Schwartz, 2021). While commonly used antibodies typically have hundred- to thousand-fold higher affinity for modified over nonmodified bases, there may be considerable background noise within the enormous sequence space of the transcriptome. As an example, a study using m6A antibodies and nonmethylated, in vitro–transcribed RNA found 10,000–15,000 peaks that could be misinterpreted as interaction sites (Zhang et al., 2021). These limitations of indirect sequencing methods are a strong impetus for the development of direct methods for determining epitranscriptomes.

TABLE 3-1 Summary of Indirect Sequencing Techniques Applied to Specific RNA Modifications

| Modification | Method | Ab-based | Chemical Modification | Computational Readout | Quantitation of Modification Levels | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m6A | m6A-seq | yes | no | Sequence enrichment | no | Dominissini et al., 2012 |

| m6A-seq2 | yes | no | Sequence enrichment | no | Dierks et al., 2021 | |

| m6A-LAICseq | yes | no | Sequence enrichment | yes | Molinie et al., 2016 | |

| GLORI | no | yes | RT–induced variant at nonmethylated A | yes | Liu et al., 2023 | |

| m6A-SAC-seq | no | yes | RT-induced random variant at m6A | yes | Hu et al., 2022 | |

| DART-seq | no | no | C-to-U variants close to m6A sites induced by expression of YTH-APOBEC1 fusion | no | Meyer, 2019 | |

| MAZTER-seq | no | no | Inference of m6A levels from cleavage activity of a m6A sensitive RNase | yes co | Garcia-Campos et al., 2019 ntinued | |

| m6A-REF-seq | no | no | Inference of m6A levels from cleavage activity of a m6A sensitive RNase | yes | Zhang et al., 2019 | |

| scDART-seq | no | no | C-to-U variants close to m6A sites induced by expression of YTH-APOBEC1 fusion | no | Tegowski, Flamand, and Meyer, 2022 | |

| miCLIP | yes | no | Crosslinkinginduced RT-stall | no | Linder et al., 2015 | |

| meCLIP | yes | no | Crosslinkinginduced RT-stall | no | Roberts, Porman, and Johnson, 2021 | |

| m6A-CLIP | yes | no | Sequence enrichment | no | Ke et al., 2015 | |

| m6A-SEAL-seq | no | yes | Sequence enrichment | no | Wang et al., 2020 | |

| eTAM-seq | no | yes | Enzymatic A-to-I variants at nonmethylated A | yes | Xiao et al., 2023 |

| Modification | Method | Ab-based | Chemical Modification | Computational Readout | Quantitation of Modification Levels | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m1A | m1A-seq | yes | no | Sequence enrichment | no | Dominissini et al., 2016) |

| ac4C | acRIP-seq | yes | no | Sequence enrichment | no | Arango et al., 2018 |

| ac4C-seq | no | yes | RT-induced random variant at chemically modified ac4C | yes | Sas-Chen et al., 2020 | |

| m3C | HAC-seq | no | yes | Mapping of C insensitive to hydrazine/aniline cleavage | yes | Cui et al., 2021 |

| m7G | MeRIP-seq | yes | no | Sequence enrichment | Lin et al., 2018 | |

| TRAC-seq | yes | yes | Insensitivity of m7G to NaBH4 reduction is exploited | Lin et al., 2018 | ||

| BoRed-seq | no | yes | Insensitivity of m7G to NaBH4 reduction is exploited | Pandolfini et al., 2019 | ||

| Ψ | CeU-seq | no | yes | Biotin is conjugated to N3-CMC-Ψ through click chemistry | Li et al., 2015 | |

| PRAISE | no | yes | Bisulfite-induced deletion signature during reverse transcription | Zhang et al., 2023 | ||

| Pseudo-seq | no | yes | Crosslinkinginduced RT-stall at CMC-modified sites | no | Carlile et al., 2014 | |

| Pseudo-seq | no | yes | Crosslinkinginduced RT-stall at CMC-modified sites | no | Schwartz et al., 2014) | |

| HydraPsiSeq | no | yes | Mapping of uridines insensitive to hydrazine/aniline mediated cleavage | yes | Marchand et al., 2020 | |

| BID-seq | no | yes | Chemical-induced RT skipping at Ψ sites read as deletion | yes | Dai et al., 2023) |

| Modification | Method | Ab-based | Chemical Modification | Computational Readout | Quantitation of Modification Levels | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inosine | AEI | no | no | A-to-G variants in RNA-seq | yes | Roth, Levanon, and Eisenberg, 2019 |

| ICE-seq | no | yes | A-to-G variants in RNA-seq | yes | Okada et al., 2019 | |

| m5C | BS-seq | no | yes | Specific variant in bisulfite-treated RNA | yes | Schaefer et al., 2009 |

| m5C-RIP-seq | yes | no | Sequence enrichment | no | Xue, Zhao, and Li, 2020 | |

| Nm | RibOxi-Seq | no | yes | Mapping of periodateinsensitive RNA 3’ends after random fragmentation | no | Zhu, Pirnie, and Carmichael, 2017 |

| RiboMethSeq | no | no | Mapping of 3’ ends protected from hydrolysis by Nm | yes | Marchand et al., 2016 | |

| Nm-mut-seq | no | no | cDNA synthesis using an evolved RT generates variants at Nm | yes | Chen et al., 2023 | |

| Abasic sites | APE1 RIP | yes | no | Sequence enrichment | no | Liu et al., 2020 |

| s4U | TUC-seq | no | yes | T-to-C conversion induced by OsO4 | yes | Riml et al., 2017 |

| SLAM-seq | no | yes | Alkylation of s4U, resulting in T-to-C variants in cDNA | yes | Herzog et al., 2017 | |

| TimeLapse-seq | no | yes | Converts s4U into C | yes | Schofield et al., 2018 | |

| m5C, Ψ, m1A | RBS-seq | no | yes | Bisulfite converts C-to-T, Ψ to deletion, m1A by mutation signature | Khoddami et al., 2019 | |

| m1A, m1I, m1G, m3C, m22G, m3U | DM-tRNA-seq | no | no | Mutation signature validated by demethylase reversal | Clark et al., 2016 |

NOTE: CMC = N-cyclohexyl-N′-(2-morpholinoethyl)carbodiimide metho-p-toluenesulphonate. Other abbreviations are defined in the Front Matter.

Single-Molecule and Direct Sequencing Technologies

Third-Generation Sequencing

Unlike NGS methods, which require DNA amplification and have short-read lengths, third-generation sequencing (TGS) methods can sequence single molecules at read lengths that allow sequencing of very long DNA molecules, or a complete RNA molecule, even for very long mRNAs. In theory, some TGS methods have the potential to produce unique signatures for each RNA modification, although the technology for this has not yet been developed. Therefore, TGS offers the potential for simultaneous identification of all modification sites and types in a single RNA molecule of any length, from end to end. Currently, two TGS methods are widely available commercially: Oxford Nanopore Technologies4 (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences24F5 (PacBio).

PacBio uses zero-mode waveguide wells that allow imaging of nucleic acid synthesis processes—a “sequencing-by-synthesis” method. When used for DNA sequencing, each well contains an immobilized DNA polymerase enzyme that binds a single-primer template DNA molecule. The nucleotides that are added for synthesis are each labeled with a different fluorophore. Sequencing is accomplished by capturing and recording the residual time of fluorescent substrates used for synthesis, which is characteristic for each nucleotide. In its current form, this method is indirect for RNA sequencing, as it requires prior conversion to cDNA by reverse transcription. Nevertheless, by substituting the immobilized DNA polymerase with a suitable reverse transcriptase, the PacBio method could, in principle, be used for single-molecule direct RNA sequencing. Although a PacBio method for RNA sequencing without cDNA conversion has yet to be applied commercially (possibly because of the difficulty of engineering highly processive reverse transcriptases suitable for the PacBio platform), the principle of applicability was published in 2013 to study m6A in mRNA (Vilfan et al., 2013). In this study m6A in mRNA was identified by a much longer dwell time between its cDNA synthesis and adjacent residues. The same principle was used for PacBio sequencing of N6-methyldeoxyadenosine in genomic DNA.

Nanopore sequencing represents a direct RNA sequencing method, meaning the RNA and their modifications are measured directly, rather than in a cDNA made from the RNA (as in NGS methods or in the PacBio method). ONT uses an array of protein pores embedded in a synthetic membrane barrier, across which a current is applied. Protein helicase capture of DNA or RNA molecules attached to specific adaptors allows for single-stranded nucleic acid molecules to move through the pore end to end, producing a current signature (called squiggles) that optimally enables bases, including modified bases, to be read (Stoddart, et al., 2010a,b). ONT suffered early on from high error rates, but thanks to advances in nanopore chemistry and basecalling algorithms, the error rates for nanopore RNA sequencing have been reduced significantly, to less than 5 percent (Wang et al., 2021). A substantial portion of the remaining errors were due to modifications to native sequences of DNA and RNA (Wick et al., 2019). See Box 3-1 for additional technical details of nanopore sequencing.

Since 2018, ONT-based sequencing has been widely applied to the study of mRNA modifications, primarily looking for the most abundant mammalian mRNA modifications: m6A, Ψ, and inosine. For example, one study used ONT’s technology to sequence a transcriptome of human polyadenylated mRNA from a cultured cell line, identified numerous isoforms, and compared a specific mRNA in vitro transcript and its cellular counterpart to show differences in the current between modified and unmodified sites, including m6A and A-to-I modifications (Workman et al., 2019). In another study, ONT analysis found that m6A modifications can appear as errors in nanopore sequencing. The researchers used a difference in the percent error of specific bases to

___________________

4 See https://nanoporetech.com/ (accessed October 27, 2023).

5 See https://www.pacb.com/ (accessed October 27, 2023).

BOX 3-1

Nanopore Sequencing

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) has developed real-time sequencing devices capable of producing 50–250 gigabases of DNA and RNA sequencing data. Their instruments, ranging from benchtop to pocket size, are capable of direct RNA sequencing (i.e., do not require polymerase chain reaction [PCR] amplification and complementary DNA [cDNA] prep), although the types of modifications they can detect are currently limited. For example, the MinION is a compact and inexpensive sequencing instrument that has been used for target-specific sequencing of the influenza A viral genome and human DNA (Gilpatrick et al., 2020; Keller et al., 2018). When sequencing polyadenine (polyA) messenger RNA (mRNA), an oligo-deoxythymine (dT) bead step is included to enrich for the polyA mRNA, which is followed by cDNA strand synthesis using an oligo-dT primer (Figure 3-2A). The RNA–DNA molecule created during cDNA synthesis prevents RNA secondary structures from forming and protects the RNA from degradation by most ribonucleases, leading to increased throughput. Nucleic acids are prepped for nanopore sequencing by ligating an RNA-sequencing adapter to the 3’ end of the cDNA–RNA hybrid molecule. A “motor protein” is attached to the adapter’s 3’ end and a “tether” protein is bound to its 5’ end. Once the complex makes contact with a nanopore, the tether protein prevents the cDNA from passing through the pore, ensuring it is not sequenced. The motor protein, meanwhile, drives the other nucleic acid strand through the nanopore at a rate of approximately 450 bases per second for DNA and approximately 70 bases per second for RNA.

An active area of research is the development of new (synthetic) nanopores and the reengineering of existing ones to increase the lifetime of the nanopores to facilitate improvements in the sequencing throughput while maintaining the accuracy of the detected bases. A number of naturally occurring pores are in use, such as the MspA pore from Mycobacterium smegmatis and the alpha hemolysin pore from Staphylococcus aureus (MacKenzie and Argyropoulos, 2023). ONT utilizes an engineered protein derived from the Escherichia coli CsgG pore, which it embeds in an electrically resistant membrane made from a synthetic polymer (Figure 3-2B) (Ayub and Bayley, 2016; Goyal et al., 2014; Henley, Carson, and Wanunu, 2016; Ip et al., 2015).

The MinION flow cell membrane contains 2,048 individually addressable pores, grouped in 512 channels. MinKNOW™, the first edition of the software provided by ONT for the MinION device, handles various core tasks, including run-parameter assignment, data acquisition, and feedback on the experiment’s progress. MinKNOW assigns four pores per channel, allowing 512 molecules to be sequenced simultaneously (Ip et al., 2015). During sequencing, a sensor measures the current fluctuations, generated by nanopores immersed in an ionic solution, several thousand times per second (Deamer, Akeson, and Branton, 2016; Jain et al., 2016).

Application of a voltage causes an ionic current to pass through the nanopore. As the nucleic acid strand moves through the nanopore from one chamber to the other, the current changes in a characteristic way that allows identification of the nucleic acid sequence. Unlike Sanger sequencing, which recognizes individual nucleotides, nanopore sequencing considers the five or six nucleotides present in the pore to produce a raw signal. These raw signals, represented as “squiggle” plots (Figure 3-4C), provide information about the changes in current from all possible K-mers (six for DNA and five for RNA) occupying the sensor pore at a given time point. For unmodified RNA, this results in 1,024 (45) different signal configurations (Bayley, 2015; Simpson et al., 2017; Wick, Judd, and Holt, 2019; Zorkot, Golestanian, and Bonthuis, 2016). Notably, the signal obtained for a specific sequence may vary between different runs, necessitating the use of signal means from several runs to accurately identify the sequence of a nucleic acid (Figure 3-2D).

NOTES: (A) PolyA+ messenger RNA (mRNA) is first enriched using oligo-dT primers and then ligated to sequencing adapters, which are bound to motor and tether proteins. (B) An array of sequencing nanopores is shown. When the nucleic acid–protein complex contacts a pore, the motor protein helps the RNA molecule pass through the nanopore in a 3’–5’ direction. Bases passing through the nanopore cause a characteristic disruption in the current, which is stored as the raw signal. The inset on the right shows a squiggle plot of the raw signal. (C) The raw signal is converted into bases using a basecalling algorithm. The plot separates normal and modified signals for a GCAGG oligonucleotide (multiple signal traces are shown, with the average highlighted in color). The left panel represents signal traces for an unmodified oligonucleotide context, while the right panel represents signals originating from the corresponding GC(m6A)GG oligonucleotide regions in the transcriptome. Data shown are idealized representative traces; real data often contain significant degrees of noise.

SOURCE: Anreiter et al., 2021, with permission from Elsevier.

detect modification sites based on data from synthetic modified RNA (Jenjaroenpun et al., 2020; Pratanwanich et al., 2021).

A few studies recently developed characteristic basecalling error signatures in the nanopore data for Ψ, which can be used to estimate per-site modification stoichiometry and to detect multiple Ψ sites at single-molecule resolution (Begik et al., 2021; Hassan et al., 2022; Tavakoli et al., 2023). It has been applied to mRNAs and rRNAs in yeast, and following oxidative, cold, and heat stress (see nanoRMS in Table 3-3) (Begik et al., 2021) and on human transcriptomes (Hassan et al., 2022; Tavakoli et al., 2023). Burrows and colleagues (Fleming et al., 2021) used 16S and 23S rRNA strands from Escherichia coli and corresponding synthetic controls in a series of studies in multiple-ribosomal RNA sequence contexts to identify differences in basecalling, ionic current, and dwell time for more than 16 different RNA modification types. They determined that the passage of Ψ through a helicase brake sensor resulted in a pause of the RNA molecule, producing a long-range dwell time, which was used to analyze SARS-CoV-2 nanopore sequencing data. Results supported the presence of five conserved Ψ sites in the viral RNA genome and rejected other sites previously reported (Fleming et al., 2021).

Given the abundance of m6A and Ψ in mRNA, multiple researchers have developed computational tools for model training, modification detection, and quantitation of m6A (Fleming et al., 2021; Gao et al., 2021; Hendra et al., 2022; Leger et al., 2021; Liu, et al., 2019a, 2022; Lorenz et al., 2020) and Ψ (Gao et al., 2021; Hendra et al., 2022; Leger et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2019a, 2022; Lorenz et al., 2020) in mRNA and other RNA types (Hassan et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Ramasamy et al., 2022). Note, however, that a systematic comparison of currently available computational tools used to decode RNA modifications from native RNA sequences found that the tools varied in sensitivity, precision, and bias (Zhong et al., 2023). Thus, while exciting developments have been made, significant improvement and progress are needed in methods such as ONT nanopore sequencing, in order for the goals this report envisions to be achieved.

Mass Spectrometry-based Methods

In addition to global analysis of modified nucleosides, LC-MS/MS has been used for direct sequencing and modification mapping of RNAs, typically more abundant RNAs (e.g., tRNAs, rRNAs). The only effective approach for mass spectrometry is to start with RNAs in which the canonical sequence (A, C, G, U) is known, which is then analyzed strictly using mass spectrometry to place modifications at specific sequence locations. Two general approaches have been developed that take advantage of the unique capabilities of mass spectrometry to directly identify the presence and location of modifications: bottom-up and top-down mapping.

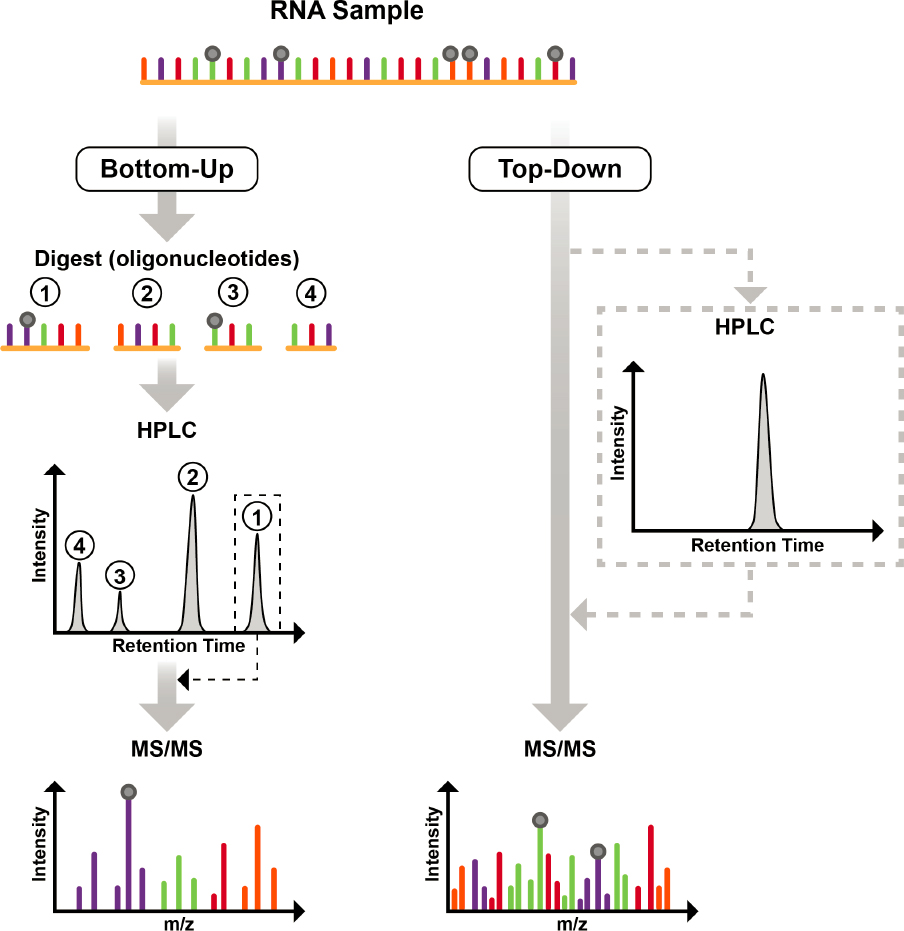

Bottom-up modification mapping. The more common approach is so-called bottom-up modification mapping. As with proteomics (Shuken, 2023), this approach involves digesting intact RNA into smaller oligomers that can be separated by HPLC and sequenced in the gas phase by MS/MS. The RNA is digested by specific nucleases or other chemical treatments (Jora et al., 2019) (Figure 3-3). For example, ribonuclease T1 cleaves RNA on the 3’-side of G residues, leading to digestion products that contain only a single G at the 3’-terminus (Table 3-2). This generates a mixture of oligoribonucleotides that are usually of a length compatible with standard LC-MS/MS instrumentation and its capabilities to perform collision-induced dissociation, referred to by some as collisionally activated dissociation (Figure 3-4).

Separation of the oligonucleotides prior to mass spectrometry analysis was improved dramatically in 1997 with the introduction of an ion-pair reversed-phase chromatography solvent system (Apffel et al., 1997). This system uses two components: an alkylamine effective at enhancing interactions of the oligonucleotide with the HPLC stationary phase and hexafluoroisopropanol that leads to enhanced ionization during electrospray ionization. To date, this general solvent system

NOTES: In the bottom-up approach (left-hand side), an RNA sample is digested into smaller pieces, oligonucleotides, which are then separated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and analyzed online by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) to yield information about sequence and modification location and abundance. In the top-down approach (right-hand side), a pure RNA sample is analyzed by MS/MS to yield information about sequence and modification location and abundance. To generate pure RNAs, mixtures can be separated by offline HPLC, and the RNA of interest can be collected as it elutes from the HPLC at a specific retention time.

TABLE 3-2 Specificity and Limitations of Enzymes Used for RNA and Oligonucleotide Digestion

| Enzyme | Cleavage Specificity | Limitation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNase T1 | 3' terminus of unmodified guanosine and the modified nucleoside N2methyl guanosine | RNase T1 does not generate high sequence coverage, especially when G-rich sequence redundancies are available | Greiner-Stöffele, Foerster, and Hahn, 2000 |

| RNase A | 3' terminus of all canonical pyrimidines and pseudouridine | RNase A generates shorter degradation products that are not useful for modification placement | Prats-Ejarque et al., 2019 |

| RNase U2 | 3' terminus of canonical purines with a slight selectivity towards adenosine | RNase U2 does not increase the sequence coverage of mapped modifications | Houser et al., 2015 |

| MC1 | 5' terminus of pseudouridine and unmodified uridines | Commercially unavailable | Addepalli, Lesner, and Limbach, 2015 |

| Cusativin | 3' terminus of unmodified cytidine and the modified nucleoside 5-methylcytidine (m5C) | Commercially unavailable | Addepalli et al., 2017 |

| Human RNase 4 | 3' terminus of uridine residues prior to purines (slight preference for U-A relative to U-G) | Generally insensitive to modified uridines | Wolf et al., 2022 |

NOTE: Abbreviations are defined in the Front Matter.

remains the best for separating oligonucleotides up to 50-mers with high chromatographic resolution (Donegan, Nguyen, and Gilar, 2022). However, because the solvent system is highly corrosive, it requires dedicated hardware, generates carryover effects when switching mass spectrometry instrumentation from negative to positive polarity, and is a health hazard to users. For those reasons, there is ongoing work on alternative solvent systems and stationary phases that can separate complex mixtures of oligonucleotides without the downsides of the current ion-pair solvent system (Demelenne et al., 2020; Hagelskamp et al., 2020).

Because mass spectrometry measures an intrinsic property of any compound (i.e., the molecular weight), regardless of the type of mass spectrometry instrument used, the molecular weight will not vary. Moreover, the more precisely (and accurately) one can measure molecular weight (or the m/z value), the easier it is to define the chemical composition of the molecule. In the early 1990s, it was shown that the number of A, G, C, and U (i.e., the base composition) in an oligonucleotide could be determined simply by using mass spectrometry to measure the molecular weight of the oligonucleotide. This would work if (a) the m/z of the oligonucleotide could be measured with high levels of precision and (b) a constraint was placed on one of the canonicals within the base composition (Pomerantz, Kowalak, and McCloskey, 1993). This key factor is one reason that digestion of RNAs via RNase T1 is preferred—because this nuclease cleaves at all unmodified G residues, any digestion product would contain a single G (assuming no modified Gs are unrecognized by the nuclease). Thus, digesting RNAs with RNase T1 generates a pool of oligonucleotides that all have a known base composition, which simplifies determining the oligonucleotide sequence and modification placement. More importantly, because the measured molecular weight of an RNase T1 digestion product must agree to a known base composition, the presence of modifications in that measured digestion product is immediately discernible because of the mass difference between the measured value and the closest base composition of lower molecular weight. These key insights allowed the expansion of direct sequence placement of modifications onto tRNAs and rRNAs and

even provided a route for using direct sequencing to identity constituent tRNAs within an unseparated mixture (Felden et al., 1998; Guymon et al., 2006; Hossain and Limbach, 2007; Kowalak et al., 1993; Wagner et al., 2004).

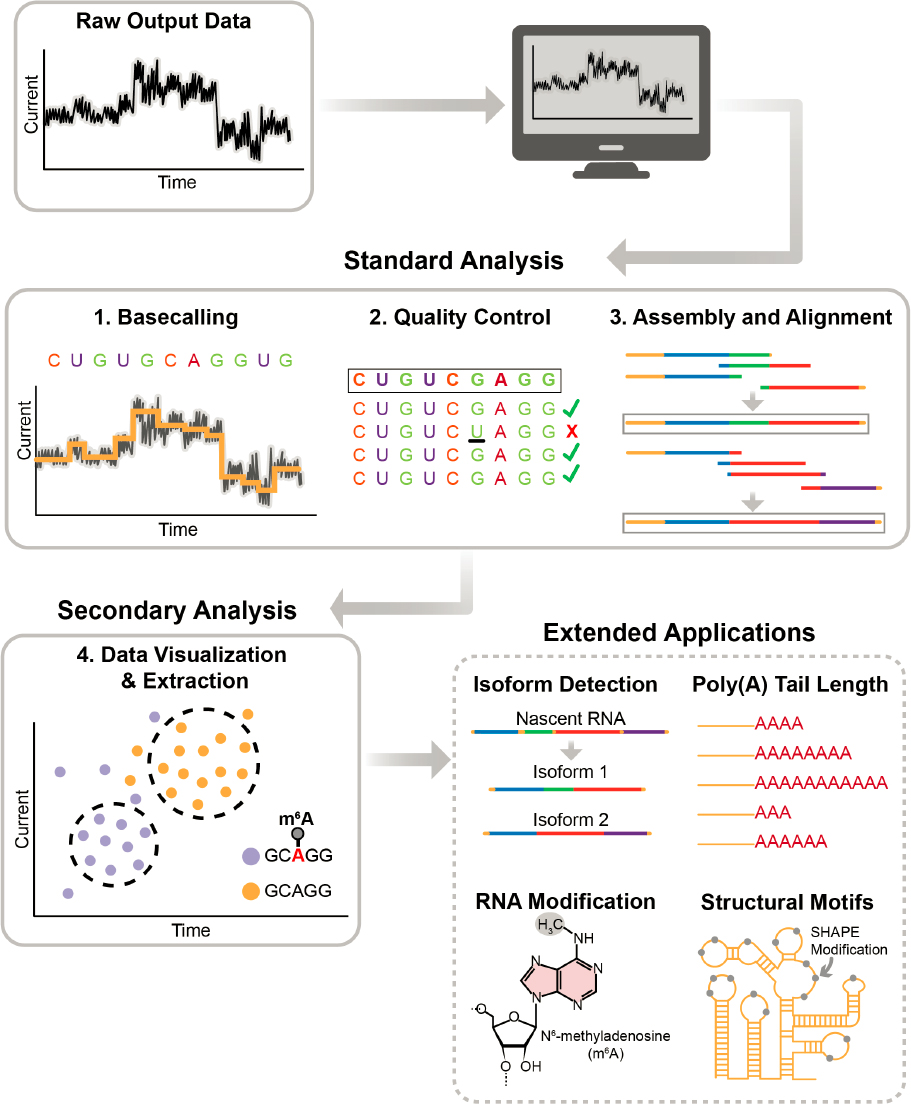

The MS/MS step is key in a bottom-up method. Because oligonucleotides have a very robust and reproducible fragmentation pattern along the phosphodiester backbone during collision-induced dissociation, a mass ladder is created whereby the identity and sequence of each nucleotide residue can, in principle, be determined based on the difference in mass between each of the 5'- and 3'-dissociation products of the same type (Figure 3-4) (McLuckey, Van Berkel, and Glish, 1992). For example, the mass difference between the dn and dn+1 fragment ions can be used to define the identity of the nucleotide (Figure 3-4). Moreover, because one only needs to measure the difference in two m/z values to define the identity of the nucleotide, the mass accuracy and resolution requirements during MS/MS can be less restrictive than those during the first stage of mass analysis.

One powerful feature of mass spectrometry–based modification mapping is that all known posttranscriptional modifications, except Ψ (an isomer of U), result in an increase to the mass of the canonical nucleotide. Because mass spectrometry specifically detects m/z values of ions, any posttranscriptional modifications are readily denoted by the unique m/z difference in the mass ladders created during MS/MS. For example, a single methylation to a canonical nucleotide results in a +14-dalton (Da) mass increase, thiolation (the replacement of an oxygen atom with a sulfur atom) results in a +16-Da mass increase, and so on. Thus, using mass spectrometry and MS/MS data,

SOURCE: D’Ascenzo, 2022. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

the sequence can be reconstructed, and the locations of modified nucleosides can be identified by evaluating the mass differences in the various mass ladders generated during analysis.

The bottom-up method was first demonstrated in 1993 (Kowalak et al., 1993). Initial applications using only LC-MS were focused on rRNA, which could be isolated as a homogeneous sample in relatively large amounts (Kowalak, Bruenger, and McCloskey, 1995; Kowalak et al., 1993). The introduction of MS/MS and additional purification strategies enabled modification mapping of other types of RNAs, often tRNAs with their many modifications (Crain et al., 2002; Suzuki and Suzuki, 2014). While these tRNA samples were purified to be homogeneous prior to mapping, more recently, bottom-up modification mapping has been applied to mixtures of tRNAs (Puri et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2019).

Several factors limit the widespread use of mass spectrometry for direct sequencing and modification mapping of RNA.

First, the bottom-up method generates some RNA digestion products that are uninformative because of sequence redundancies. For example, digestion with RNase T1 can generate monomers (single Gp’s), dimers, trimers (e.g., AUGp, AAGp), and so on that appear at multiple sites within the overall RNA sequence. Should one of these digestion products be modified—for example [m6A] UGp—the approach cannot differentiate which GAUG within the RNA contains the modification. One strategy for resolving such ambiguities is to perform multiple digestions, each using a different nuclease (see Table 3-2) to generate sufficient overlap to verify a specific modification site (Thakur et al., 2020).

Second, conventional MS/MS approaches used to generate mass ladders are less reliable for oligomers that are greater than 40 nucleotides long (Hannauer et al., 2023). Because conventional MS/MS approaches deposit a fixed overall amount of energy into the oligomer, longer oligomers have less energy per internucleotide linkage, which can reduce fragmentation (sequencing read lengths), leading to greater uncertainty about the overall sequence and where modifications are located. This is a significant obstacle when conducting de novo sequencing of modified RNAs to discover sites of modification. Thus, the ability to generate longer reads along with higher-quality sequence data from those reads would be a major advance for this method.

Third, mass spectrometry requires microgram or greater amounts of sample (Kimura, Dedon, and Waldor, 2020). Ample digestion, purification for mass spectrometry compatibility, and on-line chromatographic separation are all necessary prior to the sample reaching the mass spectrometer, and each step can lead to sample loss. New and much more sensitive workflows and instrumentation advances are necessary to reduce sampling requirements.

Fourth, very few commercial software packages, either standalone or included with an LC-MS platform, are dedicated to the high-throughput analysis of LC-MS/MS data for mapping modifications onto RNA transcript sequences. Initial programs have been open source (D’Ascenzo et al., 2022; Sample et al., 2015; Wein et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2017), but mass spectrometry vendors are beginning to provide platform-specific software packages tailored for analyzing LC-MS/MS data for the presence of modifications. These packages, however, are designed primarily for analyzing synthetic oligonucleotides, which may have few or no modifications (e.g., small interfering RNAs, guide RNAs). In addition, these programs are geared towards confirming sequencing data against a known (e.g., synthetic) sequence and do not permit one to search the LC-MS/MS data against a large number of potential sequences, such as all possible RNA transcripts present in a cell (Jiang et al., 2019). The development of software tailored specifically for mapping modifications identified in LC-MS/MS data against genomic and transcript data from any organism is a critical need for bottom-up modification mapping to become widely used.

Fifth, LC-MS platforms, especially those with performance characteristics required for the accurate identification of modifications within larger RNA sequences, are expensive, require trained operators, and are best suited for a dedicated facility. The development of benchtop systems with

the capabilities and functionalities to meet the needs of RNA modification mapping would broaden the availability and equitability of those who could take advantage of this technology. Furthermore, the current LC-MS approaches tend to be quite low throughput. A single LC-MS analysis, including column (re-)equilibration time, takes at least 60 minutes and often far longer (Bommisetti and Bandarian, 2022; Hagelskamp and Kellner, 2021; Jones et al., 2023). Therefore, identifying ways to generate MS/MS data more rapidly, combined with advances in data processing, will be vital for this field.

Top-down modification mapping. A less common but potentially powerful mass spectrometry method for RNA modification mapping is the so-called top-down approach. Unlike the bottom-up approach, top-down approaches use specialized mass spectrometry instrumentation to collect MS/MS data from large oligonucleotides or intact RNAs; enzymatic or chemical digestion is not required. Because the top-down approach preserves the complete sequence information, it significantly enhances the accuracy of mapping modifications (Taucher and Breuker, 2010, 2012).

The top-down approach uses a variety of gas-phase dissociation methods to generate sequence information from the sample. For example, collision-induced dissociation can provide nearly full-sequence coverage, but it requires a low precursor ion charge state, which decreases instrument performance, specifically its sensitivity and mass resolving power (Glasner et al., 2017; Taucher and Breuker, 2010).

Alternative-ion dissociation methods have been developed, many of which could enable more sensitive mapping of RNA modifications. Examples include radical transfer dissociation, activated-ion negative electron transfer dissociation, ultraviolet photodissociation and activated-electron photo-detachment dissociation (Calderisi, Glasner, and Breuker, 2020; Peters-Clarke et al., 2020; Santos et al., 2022). Each of these dissociation methods has their strengths and drawbacks, but exploration into these alternatives has demonstrated that enhanced sequence coverage during a top-down analysis is feasible.

Another advantage of top-down analyses is that they are directly compatible with native mass spectrometry, whereby both sequence and structural information can be obtained about the RNA of interest. An inherent limitation of top-down methods is that they are most effective when working with single RNA species. Their advantages may be better realized when seeking confirmation of expected modified RNAs versus discovery of unknown modifications from mixtures of RNAs.

Computational and Modeling Methods for Sequencing Technologies

As discussed in the previous section, computational methods for LC-MS/MS sequencing and modification mapping are lagging. The computational methods used for indirect sequencing are better developed than those for direct sequencing approaches. The tools available for indirect sequencing depend on quality control, alignment, and peak calling steps to localize modifications. Several of these steps have been researched extensively, with multiple tools developed for each of these steps that are shown to perform well. This section focuses on the current computational tools that are used when sequencing RNA and mapping its modifications with nanopore sequencing.

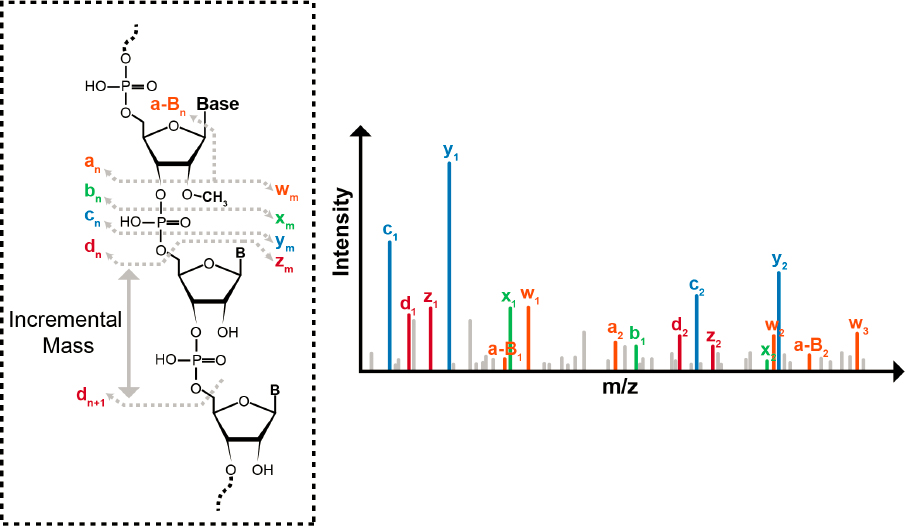

Data analysis is an integral component of the nanopore sequencing and mapping process, because the raw output is a set of changes in electrical current rather than a sequence of specific and modified bases. The major steps involved in analyzing data generated from nanopore direct RNA sequencing can be divided into basecalling, quality control, assembly and alignment, and signal data extraction (Figure 3-5).

SOURCE: Secondary Analysis (bottom left) adapted from Koonchanok et al., 2021. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Basecalling

Basecalling is the process of translating raw electrical signals into accurate nucleic acid base sequences. Nanopore sequencing uses a sequencing-by-translocation approach, in which the sequencer detects changes in electrical signals as different bases pass through the nanopore. Basecalling is a critical step in nanopore sequencing because noisy data from single molecules lead to high error rates (Wick, Judd, and Holt, 2019). The use of neural network–based basecallers, such as Guppy,6 Albacore,7 and Scrappie,8 has improved accuracy compared with earlier hidden Markov model approaches (Box 3-2) (Wick, Judd, and Holt, 2019). Despite continued improvements in basecalling algorithms, nanopore sequencing continues to have higher error rates than indirect sequencing techniques such as Illumina sequencing (Napieralski and Nowak, 2022; Zhang et al., 2020). Several basecalling tools have been developed, which are described in Appendix A, Table A-1.

BOX 3-2

Bioinformatics of Nanopore Sequencing

To obtain the sequence of input molecules in nanopore-based sequencers from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), an electrical signal must be translated into individual bases through a process called basecalling. MinKNOW, the software used for sequencing, offers an built-in basecaller for real-time basecalling during the sequencing run. Users can choose to turn off this function and perform basecalling on the raw files using an alternative basecaller at a later time. ONT currently offers multiple versions of the basecalling software, including Doradoa and Bonito,b which can process both DNA and RNA sequencing datasets.

Earlier versions of basecallers required that the raw current signal measurements, represented by the “squiggle” plot, be segmented into events. Each event’s duration, mean, and variance formed the input for the basecalling algorithm (Garalde et al., 2018). In the quest to develop more accurate algorithms, ONT and other research groups have been exploring machine learning–based approaches.

The initial generation of nanopore basecallers relied on hidden Markov models (HMM) to predict DNA sequences (Eddy, 2004). HMMs are probabilistic models that predict unobserved events based on the information about the previous events. However, basecallers using recurrent neural networks (RNNs) (Boža, Brejová, and Vinař, 2017) have replaced HMM-based approaches. RNNs utilize a longer range of information, and bidirectional RNN models consider bases both before and after a nucleotide of interest, leading to increased accuracy (Rang, Kloosterman, and de Ridder, 2018).

With the release of Guppy (Wick et al., 2019) and subsequent versions, which share basecalling features with previous versions of the basecallers but run on a graphics processing unit (GPU) instead of a central processing unit (CPU), basecalling speed increased more than tenfold (~1,500,000 base pairs/second versus ~120,000 base pairs/second). Guppy (V3.4.5) also reduced the basecalling error rate to between 4 and 6 percent for DNA and 7 and 12 percent for RNA (Wick et al., 2019). The latest version of the Guppy basecalling framework (as of the writing of this report) is trained to call the modified bases in DNA, 5mC and 6mA (N6-methyldeoxyadenosine), from the raw signal data.

Both HMM and RNN models rely on training signals, and basecaller performance depends on the quality of the training dataset. The significant advantage of nanopore direct RNA sequencing is the ability to access single-molecule sequencing of mRNA transcripts and investigate RNA alterations. As basecalling algorithms improve and error rates decrease, it becomes possible to revisit older raw datasets for sequencing and analyze them again using newer and more accurate algorithms.

__________________

a See https://github.com/nanoporetech/dorado (accessed November 12, 2023).

b See https://github.com/nanoporetech/bonito (accessed November 12, 2023).

___________________

6 See https://timkahlke.github.io/LongRead_tutorials/BS_G.html (accessed November 12, 2023).

7 See https://nanoporetech.com/about-us/news/new-basecaller-now-performs-raw-basecalling-improved-sequencing-accuracy (accessed November 12, 2023).

8 See https://github.com/nanoporetech/scrappie (accessed November 12, 2023).

Quality Control

Quality control analysis of ONT sequencing data is critical to offset the error-prone basecalling that ONT instruments generate, which if left unfixed will affect downstream analysis. Some popular quality control tools for ONT long-read data include Poretools, poRe, NanoOK, ToulligQC, and PyPore. Each offers unique features and functionalities. For example, Poretools and poRe provide yield plots, histograms, and various summary statistics of MinION output (Loman and Quinlan, 2014; Watson et al., 2014). NanoOK focuses on alignment-based quality control and error profile analysis (Leggett et al., 2015). ToulligQC supports barcoding samples and produces various graphical representations for data exploration9 and PyPore improves existing tools for fast, accurate quality control (Semeraro and Magi, 2019). For a more extensive list of quality control tools, see Appendix A, Table A-2.

Sequence Assembly and Alignment

Sequencing assemblers designed for analyzing long-read sequencing data from direct sequencing platforms are crucial tools for building the end-to-end sequence of an RNA molecule from the basecalled data. A few assemblers are provided briefly as examples, while an extended list of assemblers is in Appendix A, Table A-3.

MaSuRCA is a long-read assembler that generates an error-free “super read” by joining multiple reads from the reference genome (Zimin et al., 2013). Canu is an assembler designed for noisy long-read sequences that uses a hierarchical assembly pipeline to produce accurate assemblies (Koren et al., 2017). Unicycler is a hybrid assembler that combines Illumina and ONT data for bacterial genomes (Wick et al., 2017). HINGE addresses the challenges of graph assembly with longer reads, automating the process and reducing problems with fragmented and unresolvable repeats (Kamath et al., 2017).

Alignment tools work together with assemblers to identify the correct location in the genome of a particular fragment of sequenced RNA. Appendix A, Table A-4 summarizes alignment tools used in long-read sequencing analysis, particularly those used with ONT-generated reads. Among the options are Minimap2, which is used to align long nucleotide sequences and performs well with sequences of 100 or more base pairs. GraphMap2 is a splice-aware RNA sequencing algorithm that maps long-read data to reduce repetitive alignments.10 mapAlign is a software package that includes algorithms for mapping and local alignments of long reads against a reference genome (Yang and Wang, 2021).

While long-read sequencing has advanced since direct sequencing was first introduced, raw data accessibility remains a significant challenge. Selecting the right assembler and aligner depends on the specific needs of the researcher, lab resources, and dataset characteristics. For example, Shasta is a fast assembler of nanopore reads, but it requires large computer memory (Marx, 2021; Shafin et al., 2020).

Signal Data Extraction

The raw electrical signals that are the output from a nanopore sequencer contain embedded data corresponding to the sequenced nucleotides. Thus, careful extraction and analysis of the data are essential for revealing the biological information hidden in these signals (Figure 3-5). Some of the biological information that can be gleaned is the detection of RNA isoforms, estimation of poly(A) tail length, detection of RNA modifications, and prediction of RNA secondary structures depending

___________________

9 See https://github.com/GenomicParisCentre/toulligQC (accessed November 14, 2023).

10 See https://github.com/lbcb-sci/graphmap2 (accessed November 14, 2023).

on the specific variant of direct RNA sequencing protocol employed. Some tools used for extraction and analysis of raw signal data are Nanopolish, Racon, Tombo, SquiggleKit, and Sequoia.

Nanopolish improves the consensus accuracy of an assembly of nanopore sequencing reads. It can detect methylation, single nucleotide variants, and insertions and deletions; align signal-level events; and estimate polyadenylated tail lengths (Loman, Quick, and Simpson, 2015). Racon is used to correct raw contigs generated by rapid-assembly methods (Vaser et al., 2017). Tombo enables the investigation, detection, and visualization of modified DNA and RNA nucleotides using statistical tests to compare signal differences (Stoiber et al., 2017). SquiggleKit can extract, process, and plot raw nanopore signal data (Ferguson and Smith, 2019). Sequoia is a visual analytics tool that allows interactive exploration of nanopore sequences, including clustering sequences based on electrical current similarities, drilling down into signals to recognize properties of interest and comparing signal features from RNA modifications (Koonchanok et al., 2021, 2023).

Computational Tools for Mapping RNA Modifications

While direct RNA sequencing offers great promise for identifying RNA modifications at single-base resolution, interpreting raw signals corresponding to modified and unmodified base-sequence contexts is challenging. Currently, more than 170 RNA modifications have been reported in the literature (Kadumuri and Janga, 2018), and generating unbiased training models encompassing these diverse modifications would imply an increase in the RNA alphabet to 174 from the mere 4 regular nucleotides currently studied. For instance, developing algorithms that can simultaneously infer four regular nucleotides and give RNA modification types from ONT data may require at least 95 possible pentamer signals to construct reference oligonucleotide signatures. (Note that ONT’s tools “see” a pentameric stretch of nucleotides in a pore.) Thus, two challenges arise: (1) capturing all of the pentamer nucleotide configurations that contain the four canonical nucleotides and the modified nucleotides observed across all of the transcriptomes of interest; and (2) generating synthetic signals corresponding to those configurations. Surmounting these two challenges will likely drive development of the next generation of nanopore RNA-modification-aware basecallers for ONT data. Table 3-3 shows a list of algorithms and software tools currently available for mapping RNA modifications using ONT-generated datasets.

Four approaches are used to predict the modifications:

- Employing basecalling errors at the modification site as a surrogate to mapping the modified nucleotides onto transcripts.

- Using RNA modification loci reported from antibody-based methods to develop modification-specific basecallers for direct RNA-sequencing data.

- Making a direct comparison of signals from wild-type and knockout cells at bonafide modification locations reported in the literature to develop machine learning models. This approach assumes that modifications are lost in cell lines when known modification writers are knocked out.

- Employing synthetically designed RNAs containing modified nucleotides to generate nanopore signals and using the resulting data for developing machine learning models that can distinguish a particular modification from its unmodified counterpart.

Most of the platforms that predict and localize modifications use machine learning models. These models depend on high-quality training datasets to perform effectively. For example, Nanocompore was developed to study RNA modifications from direct RNA sequencing data. It runs an automated pipeline for data preprocessing, including basecalling; alignment using Minimap2; and quality control using Nanopolish. Nanocompore uses an unmodified control sample to detect

TABLE 3-3 Overview of Various Tools for Identifying RNA Modifications in Direct RNA Sequencing Data

NOTE: Abbreviations are defined in the Front Matter.

transcriptome-wide m6A modification events. The developers have suggested that this framework could be used for detecting any type of RNA modification event (Leger et al., 2021).

MAJOR CHALLENGES AND SCIENTIFIC GAPS

A complete understanding of all RNA modifications—that is, where they map on each RNA molecule and their roles in living systems—will require significant technological advancement. Despite the progress that has come from adapting existing DNA and protein sequencing and analysis methods to sequence RNA and its modifications, tools and methods specific to RNA lag behind those for DNA and proteins significantly. This is, in part, because of challenges related to the intrinsic nature of RNA molecules. First, RNA molecules are relatively unstable and prone to

degradation, so they are difficult to isolate, preserve, and analyze. Second, RNA modifications are transient, and their numbers and types are specific to the microenvironment of a particular molecule, cell, or tissue, making it difficult to isolate enough copies for analysis. Third, the central dogma of molecular biology had, for a time, established RNA as a simple carrier of information from DNA (the source code) to proteins (the product). This paradigm overlooked the extraordinary complexities and functions of RNAs and their modifications, leading to the relative dearth of RNA-specific tool developments. While much has been discovered about the myriad roles of RNA and RNA modifications, this emerging field would benefit from tools and technologies dedicated to addressing the specific challenges that come with sequencing RNA and identifying, mapping, and quantifying RNA modifications.

The ultimate technological goal is to develop robust, reproducible, and accessible tools and methods for identifying all RNA modifications from one end of a single RNA molecule to the other, at a sensitivity that allows interrogation of a single cell, as well as tools and methods for determining modification stoichiometry and crosstalk between multiple modifications within a single RNA. Several limitations in the currently available technologies for global modification measurement, indirect sequencing, direct sequencing, computational tools, and databases prevent accomplishing this ultimate goal. As discussed in the preceding sections, limitations for each of the available technologies for interrogating RNA modifications include the following:

- The use of LC-MS/MS for the global characterization and quantification of modified nucleosides (or nucleotides) remains ripe for improvement. For one, the approach cannot yet quantify all modifications in complex mixtures with both high accuracy and high precision. Beyond those described earlier in this chapter, new, mass spectrometry–friendly ways to process RNA samples with minimal sample handling would reduce sample loss or degradation, and in turn, would reduce the amount of RNA needed for the analysis. Unique derivatization reagents applicable to all modified nucleosides that take advantage of mass spectrometry ionization and detection methods could enhance sensitivity, which would also reduce initial sample requirements.

- Next-generation indirect sequencing generates a large volume of data at low cost but cannot yet do so at the single-molecule or single-cell level. It also does not allow simultaneous interrogation of modifications. Third-generation indirect sequencing is amenable to single-molecule and single-cell DNA sequencing, but applications for RNA have been explored only cursorily.

- Direct sequencing holds the most promise for RNA, but the options are still in early developmental stages and are therefore expensive, require substantial amounts of starting material, and are prone to error.

Addressing gaps in measurement technologies would have maximal impact if accompanied by addressing gaps in the associated computational tools that allow analysis, interpretation, and use of the data generated. Computational methods for improving the basecallers used by many direct sequencing methods are critical for improving the ability of these sequencers to detect modified RNA nucleotides accurately. Current basecallers can recognize the signals generated by only a handful of the ~170 RNA modifications. Furthermore, it can be difficult or impossible to distinguish between some modifications, such as N1-methyladenosine (m1A) and m6A, in certain contexts.

To date, progress has been very limited in developing algorithms that can detect simultaneously the co-occurrence, interaction, and functional consequences of one or more RNA modifications at single-molecule resolution. The ability to detect or infer 10–15 different modifications on a single RNA molecule simultaneously would be a significant step forward. Using artificial intelligence and machine learning methods to develop and train an ensemble basecaller could help in achieving this

advance (see Emerging Computational Tools). In addition, the capability to synthesize long RNA oligonucleotides with these modifications in a variety of combinations and sequence contexts (see Chapter 4) will be needed for training these methods.

Tools that can visualize or simulate the impact of RNA modifications on the two- and three-dimensional structure of RNA molecules will move the field closer to understanding the functional role of every modified RNA isoform. Determining the impact of RNA modifications on the higher-order structure of an RNA molecule could be aided by better tools for RNA structure visualization. Embedding such tools in genome and RNA-specific browsers would enable researchers to look at RNA molecules as they may occur in the cell, rather than as a linear array of ribonucleotides. These tools could also make it possible to view or simulate structures with and without modifications present, thus giving complementary insights into the relationship between specific modifications and RNA structure; current tools, designed mostly in the style of linear DNA representations, are unlikely to provide these insights.

Currently, when interrogating an RNA sequence, most reference data are derived from genomes (i.e., DNA-based reference data). It will be important to develop RNA-based reference data to better enable researchers to query databases about RNA structure–function relationships, while sharing a common coordinate system with the DNA-based reference data for convenient cross-referencing.

EMERGING TOOLS AND TECHNOLOGIES

One of the major lessons learned from other large-scale biotechnological efforts, most notably the Human Genome Project, is that focused and concerted organization and funding directed toward a common goal accelerates technological innovation. While it is difficult to predict the emergence and trajectory of breakthrough technologies, this section explores some intriguing concepts that are shaping the future of research and development in the field of RNA modifications.

To achieve the ultimate technological goal of identifying all RNA modifications in an RNA molecule and determining their stoichiometry and crosstalk, major advancements are needed in several general categories.

First, the technologies must be sensitive enough to analyze a single molecule and specific enough to deduce the sequence and composition of each ribonucleotide within that sequence. Achieving high sensitivity and high specificity will likely come from improved sensors, signal processing, and analysis tools, as well as advancements in RNA sample preparation methodologies, including purification/concentration methods and possibly RNA amplification methods that preserve modification information. For instance, RNA-dependent RNA polymerases—which have the ability to catalyze the synthesis of an RNA strand complementary to a given RNA template and are found across a range of organisms, including viral and plant genomes—could contribute to improved methods for amplifying RNA (Dalmay et al., 2000; Gerlach et al., 2015; Shu and Gong, 2016; Wu and Gong, 2018; Yin et al., 2020). Hence, RNA amplification methods, especially those that can preserve the modifications or modification-related information, could significantly circumvent the challenges associated with the need for large input material in direct RNA-sequencing protocols.

Second, the technologies must have the flexibility to sequence the diversity of RNA inputs, including short and long RNA sequences; mitigate the effects of secondary and tertiary structures; and accept sample inputs from a variety of biological sources.

Third, the technologies must be robust and widely accessible. Current workflows are cumbersome and require highly skilled users or teams to perform them. Future innovations must offer turn-key solutions to empower a broader research community to work with RNA.

Fourth, there is a need for advancements in computational tools and databases that are specific for the study of RNA and its modifications.

And lastly, as discussed in the next chapter, these technologies must be complemented with advancements in the preparation, stability, and accessibility of a wide range of RNA references and standards that represent the diversity of RNA modifications and that satisfy the needs of RNA sequencing technologies.

While there is some possibility that these goals will be achieved by a singular sequencing technology, it seems likely, particularly in the short term, that a combination of complementary, crosscutting, and hybrid approaches will be required. The following sections highlight some promising emerging technologies that (1) capitalize on existing DNA and protein sequencing technologies, (2) adapt existing structural biology technologies, and (3) leverage technologies that are not traditionally associated with biological analysis.

Emerging Indirect Sequencing Technologies

The development of reagents and procedures that derivatize RNA in a modification-specific manner will enable indirect sequencing methods to be used for end-to-end detection and sequencing of modified RNAs. For example, several microbial enzymes have been found to alter modified nucleotides in ways that mark these nucleotides during the reverse transcription process that precedes sequencing. Escherichia coli AlkB demethylase and its engineered derivatives can remove methylations that interfere with reverse transcription from tRNA and mRNA molecules prior to sequencing library construction (DM-tRNA-seq, ARM-seq) (Cozen et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2015). E. coli endoribonuclease MazF can cleave an unmethylated 5′-ACA-3′motif, but not the 5′-m6ACA-3′motif, which when followed by NGS enables those m6A nucleotides to be identified (MAZTER-seq [Garcia-Campos et al., 2019], m6A-REF-seq [Zhang et al., 2019]). The rRNA modification enzyme Mjdm1 can selectively label m6A-modified nucleotides in the transcriptome (m6A-SAC-seq) (Hu et al., 2022). The evolved enzyme TadA can convert unmodified A into inosine, which is read as G during sequencing, while m6A nucleotides read as A when sequenced (eTAM-seq) (Xiao et al., 2023).

Another source of protein reagents useful for RNA modification sequences is RNA-binding protein domains, which recognize specific modifications, such as the human YTH domain used in the DART-seq (deamination adjacent to RNA medication targets) method of m6A sequencing (Meyer, 2019). Additionally, engineered antibodies that recognize specific modifications have been a useful tool for modification mapping; examples include antibodies against m6A, N1-methyladenosine (m1A), and N7-methylguanosine (m7G) (Table 3-1) (Helm and Motorin, 2017; Zhang, Lu, and Li, 2022). These examples demonstrate the utility of protein agents for RNA modification sequencing and highlight the need for continued efforts to identify new and novel enzymes and modification readers from microbial and eukaryotic sources.

CRISPR-based systems have also been used to target specific RNAs by expressing RNA-specific guide RNAs together with RNA-binding Cas proteins. For instance, fusing catalytically inactive Cas13 (dCas13) with human ADAR2 has been used to direct A-to-I editing in RNAs of interest (Cox et al., 2017). This strategy enables selective alteration of protein composition and has potential utility as a therapeutic agent for correcting disease-causing variants. Similarly, tethering dCas13 to the METTL3/METTL4 methyltransferase complex proteins can be used to achieve site-specific m6A modification of target RNAs (Wilson et al., 2020). Targeted m6A removal has also been demonstrated by fusing catalytically dead Cas proteins to RNA demethylase enzymes (Li et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2019b). These examples highlight the utility of CRISPR-based approaches for enabling selective chemical manipulation of RNAs of interest. Such systems have tremendous potential to be used both as basic biochemical research tools and as novel therapeutics, but require that proper controls be developed to evaluate them and their limitations before they can be used for therapeutic benefit. Therefore, continued engineering of improved CRISPR systems that have

enhanced specificity and sensitivity for different types of modifications will be critical for expanding the capabilities of these systems.