Rapid Expert Consultation on Archival Data Storage Technologies for the Intelligence Community (2024)

Chapter: Current Data Storage Technologies

Current Data Storage Technologies

Archival data storage technologies likely to be available in the fiscal year (FY) 2026–2030 timeframe are dominated by current commercial solutions. These include magnetic storage, such as hard disks and magnetic tape; NAND-based flash SSDs; MRAM; and optical storage. Each is discussed in turn.

MAGNETIC STORAGE: HARD DISK DRIVES

HDDs and magnetic tape systems are based on magnetic media. These are well-proven, robust technologies that have been in use for several decades. Data are encoded as magnetic patterns on the magnetic media, and the information is read back by sensing the magnetic field arising from the magnetic pattern. For an HDD, the magnetic media is on the surface of a rigid disk.

The HDD industry has consolidated with three main suppliers: Seagate, Western Digital, and Toshiba. The industry has the capability to ship millions of units per year amounting to multiple exabytes of data. The HDD industry is robust, well supported, and multi-sourced and should continue to support exabyte demand into the foreseeable future.

Technological Advances in Hard Disk Drives

The HDD industry has seen many technological transitions during its existence and is currently on the cusp of yet another major transition.

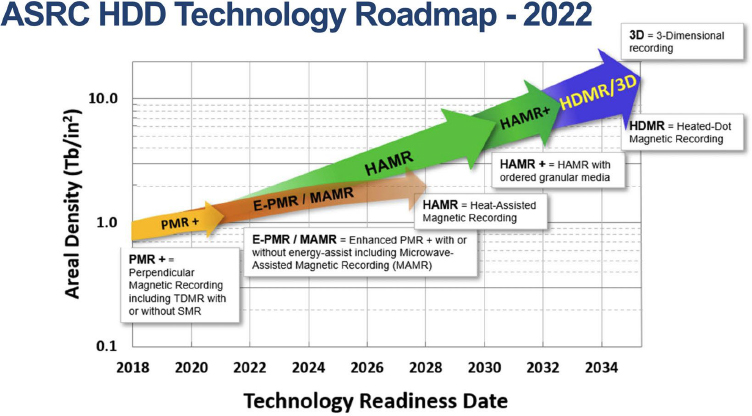

Figure 1 shows the 2022 HDD Technology Roadmap, which is produced by the Advanced Storage Research Consortium, a consortium focused on future technology advancements. This technology roadmap should not be interpreted as a product roadmap; typically, the transition of technologies to actual products can take anywhere from 5–10 years. For example, current HDD products being shipped in the industry are supported by PMR+ (perpendicular magnetic recording drives with extended capacities) technologies that are represented in Figure 1.

Heat-assisted magnetic recording (HAMR) is the latest technological change expected in the industry, and its transition to commercially available products is expected to begin in calendar year 2024 and take place over the next 5 years. HAMR has the potential to produce hundreds of terabytes (TB) of HDD capacity per unit. For comparison, current HDD products are in the range of mid-20 TB per unit. HAMR has its own unique engineering challenges to overcome, which are being worked on by industry. Overall, there is industry consensus that HAMR technology will succeed and enable a new generation of HDDs that can scale toward 100 TB of capacity per unit.

SOURCE: Advanced Storage Research Consortium, 2022, “ASRC HDD Technology Roadmap—2022,” https://asrc.idema.org/documents-roadmap.

Security

HDDs have served industry, government, and academic stakeholders for decades and have implemented all standard security features in the drive, ranging from standard encryption all the way to federal information processing standard (FIPS)-certified HDDs.8 These security features ensure that data are encrypted at rest, rendering the information inaccessible to an adversary if the media are lost, stolen, or disposed of. HDDs also have a secure erasure feature for secure disposal of HDDs upon end of life. In addition, the drives can be degaussed, shredded, and/or recycled if needed.

The supply chain for HDDs is well diversified, and the HDD industry has made efforts to avoid single points of failure in the supply chain. HDDs have robust reliability metrics and support a mean time between failures of 2.5 million hours with a 5-year warranty period with recommended workload utilization of 550 TB/year mixed read/writes. New technologies like HAMR are targeted to meet and/or beat these reliability metrics.

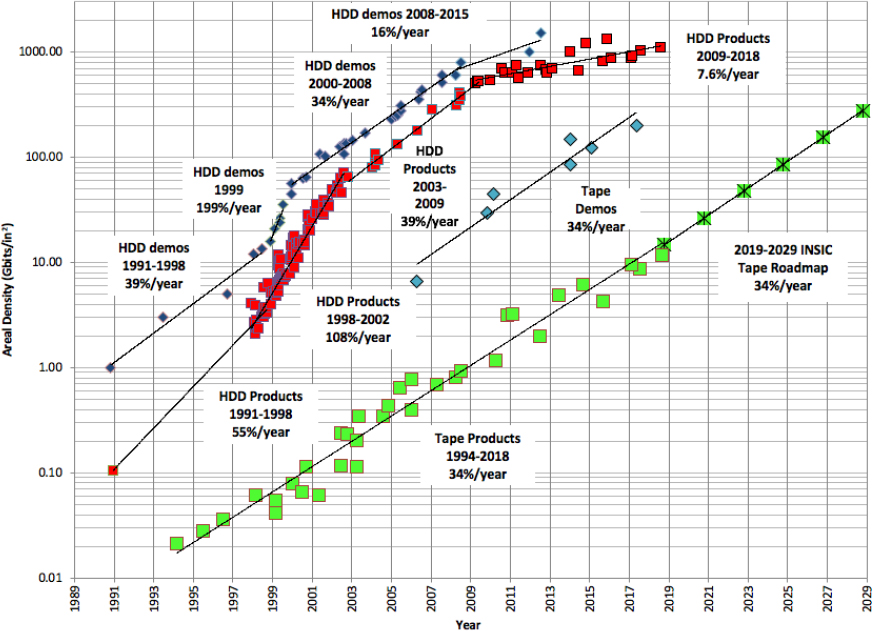

Cost

The cost of HDDs has seen a continual decline. This cost decline has been enabled by the growth in areal density, as shown in Figure 2. Figure 3 shows this decline in cost per gigabyte (GB) for HDD storage. As shown in Figure 2, in the 2000s, the areal density growth for HDDs was about 39 percent per year. Figure 2 also shows a decrease in the 2009 to 2018 timeframe, with a rate of about 7.6 percent per year. A slowdown like this can be partially mitigated by increasing the number of heads and platters in an HDD, but the current growth rate remains more sluggish than historical rates.

__________________

8 See, for example, Archon Secure, “Securing Sensitive Government Data: Understanding FIPS Certification and Compliance,” https://www.archonsecure.com/blog/fips-compliant-fips-certified-fips-validated, accessed November 22, 2023.

NOTE: HDD, hard disk drive.

SOURCE: Information Storage Industry Consortium (INSIC), 2019, 2019 INSIC Technology Roadmap, July, https://www.insic.org/wpcontent/uploads/2019/07/INSIC-Applications-and-Systems-Roadmap.pdf.

SOURCE: Courtesy of Backblaze, Inc., https://www.backblaze.com/blog/hard-drive-cost-per-gigabyte.

On average, decline in cost has varied depending on technological transitions. For example, in the 1990s the cost decline was on average around 20 percent year over year, whereas in the 2000s it was around 30 percent year over year. In recent years, this was reduced to an average of 10 percent year over year. These cost declines are a function of technological transitions, industry consolidation, changing market dynamics, and product choices. The current HDD price on average is expected to be around $0.015/GB. With technological advancements like HAMR, cost decline is expected to continue. The expectation for HAMR is between 15–25 percent compound annual growth rate. That said, the super-paramagnetic effect, a physical limit on the amount of data that can be stored on a hard disk, poses long-term challenges to the future scaling rates of HDDs. It is also unclear when or if the introduction of new technologies to continue HDD scaling will be successful.

In addition, HDD costs scale with supply and demand. The last few quarters of 2023 have seen softer demand for HDDs,9 which has resulted in revenue reductions for each of the HDD suppliers. Because manufacturing HDDs is a capital-intensive process, lower demand leads to underutilization of factory footprints, and those fixed costs need to be accounted for in the product cost. Regardless of the new technologies introduced, it may not be prudent to count on continuing decreases in price by the orders of magnitude seen historically. Cost reductions of a factor of 2–4 times over the next decade are more reasonable and consistent with projected roadmaps.

__________________

9 Storage Newsletter, 2023, “WW HDD Shipments in 2CQ23 Down 6.8% Q/Q,” August 16, https://www.storagenewsletter.com/2023/08/16/ww-hdd-shipments-in-2cq23-down-6-8-q-q.

Durability

Durability is defined as the probability that a data object will be intact and available for access after 1 year.10 For example, 99.999 percent probability, or five “nines” of durability, means that for an archive of 10,000 objects, one might lose 1 object every 10 years or so. Figure 4 shows the durability estimation for current HDD and tape-based products of various sizes and future roadmap operating points. Figure 4 shows the estimated number of files lost, normalized to a data set size of 1 petabyte (PB), which includes measures of the annual failure rate and bit error rate. Overall, HDDs have a specified life range between 5–10 years, driven in large part by industry’s push to maximize the areal density of the stored data while minimizing cost. For longer-term storage comparable to magnetic tape (see “Magnetic Storage: Magnetic Tape” section below), it is certainly possible to lower the areal density of HDDs below the current state of the art in order to gain a significant increase in data durability. This is not currently being done due to the lack of a market for long-term HDD storage, but the possibility exists (with little change to the HDD design) if there is sufficient demand. Longer-term storage may also involve shutting down the drive motor for a time. The IC may want to consider requesting that HDD manufacturers produce specially designed HDDs with extended lifespans.

NOTE: AFR, annual failure rate; BER, bit error rate; LTO, linear tape open; M, million; MB, megabyte; PB, petabyte; TB, terabyte.

SOURCE: Information Storage Industry Consortium (INSIC), 2019, 2019 INSIC Technology Roadmap, July, https://www.insic.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/INSIC-Applications-and-Systems-Roadmap.pdf.

Sanitization

Magnetic storage technologies such as HDDs and magnetic tapes typically undergo media sanitization at the end of the product life cycle to ensure that all sensitive information stored on the magnetic recording medium cannot be accessed by some specified level of retrieval effort. Depending on the confidentiality level of the data stored in the magnetic storage device and the risk tolerances an organization deems acceptable, there exists an array of different sanitization

__________________

10 Information Storage Industry Consortium, 2019, “Tape Roadmap INSIC Report, 2019,” Monroe, VA.

procedures and techniques an organization can utilize to render accessing the original stored information infeasible, even when using state-of-the-art laboratory techniques.

Commonly, sanitization processes or actions are classified in terms of their level of invasiveness and whether the magnetic storage product can be reused:

- Clear actions utilize noninvasive logical techniques that overwrite the original user data in user-accessible storage locations;

- Purge actions utilize logical and/or physical invasive techniques to permanently erase information from the user-accessible and nonassessable locations via overwrite, block erase, and cryptographic erase techniques; and

- Destroy actions permanently disintegrate the magnetic storage device into nonfunctional parts via physical destruction methods.

Because the magnetic storage industry continuously modifies its magnetic storage products to increase performance, storage capacity, and reliability, it is important that organizations routinely review and update their sanitization practices.

Technology Readiness Level

After decades of use in a variety of applications, HDD technology has a TRL of 9. However, establishing whole “farms” of storage units to store ever-larger amounts of data inevitably creates some system-level challenges. Building massive storage facilities containing HDD media is not an off-the-shelf endeavor and will require expertise in the design and implementation of large-scale storage systems to ensure that the HDD technologies are meeting the IC’s needs.

MAGNETIC STORAGE: MAGNETIC TAPE

Like HDDs, magnetic tape systems are based on magnetic media. Unlike HDDs, the magnetic media is written onto the surface of a flexible tape that is stored in spools on removable cartridges. While the magnetic tape sector is relatively small, demand for data storage technologies is driving steady investment and ongoing maturation of tape storage media.

In general, magnetic tape has less areal storage capacity than HDDs. State-of-the-art tape drives utilize areal densities that are about two orders of magnitude less dense than the latest HDDs. This lower areal density is driven by business considerations and magnetic tape R&D investment levels. Tape gets its capacity advantage over HDDs by having a much larger recording surface in a cartridge, with about 1,000 times the area of a 3.5-inch disk platter. Consequently, magnetic tape does not need as high a recorded areal density to achieve its cost per gigabyte advantage.11

Technological Advances in Magnetic Tape

Over the past two decades, the industry has made steady advances in magnetic tape capacity and capability. The magnetic linear tape open (LTO) open-format standard has been in development since the late 1990s. An LTO Consortium comprising Hewlitt-Packard, IBM, and Quantum has led development of successive generations of LTO standards. LTO releases have historically occurred on a roughly 3–4-year cadence. Each LTO generation has expanded both native and compressed magnetic tape storage capacity, while integrating features such as partitioning, encryption, and write-once, read-many (WORM) capabilities into tape media.

__________________

11 Storage Newsletter, 2016, “Storage Outlook – Fred Moore, Founder of Horison Information Strategies,” press release, September 27, https://www.storagenewsletter.com/2016/09/27/storage-outlook-fred-moore-founder-of-horison-information-strategies.

Generally speaking, LTO storage capacities have doubled with each LTO generation. However, the rate of increase has slowed more recently, with a 50 percent increase in capacity between LTO-8 (2017) and LTO-9 (2020). LTO-10 is the format’s next generation and expected to become available in late 2023 to early 2024.12

Figure 2 shows areal density (number of bits per unit area of the media, in this case measured in Gbit/in2) of HDDs (both products and demonstration), tape products, and laboratory demonstrations, as well as estimates of the rate of improvement (slope) over various timeframes for each type of storage.

According to these consortium estimates, it should be possible to continue scaling tape technology at historical rates for at least the next decade before tape begins to face challenges related to the same super-paramagnetic effect limiting HDDs.13 Indeed, as Figure 2 indicates, the 2019 Information Storage Industry Consortium roadmap assumed continuation of the historical 34 percent growth rate for the tape areal density, corresponding to a 40 percent annual increase in media capacity and a concomitant decrease in cost.

Security

Like its HDD cousin, magnetic tape supports on-the-fly encryption and storage of encrypted data and enables application of FIPS-level security (designed to protect from unauthorized viewing at rest or in transit) to magnetic tapes. Additionally, tape cartridges can easily be physically removed for storage, providing an extra air-gapped layer of protection.

Indeed, one of the major selling points for magnetic tape media is their inherent physical security: they can be put into inactive storage for long periods of time, away from read/write access points, providing significant insurance against malicious attacks (e.g., ransomware).

On the other hand, managing data stored on magnetic tape can be a laborious process. That is because magnetic tapes are a serial media that can only be written to or read from a magnetic tape drive. Because the process is linear, writing and reading data can be slow, particularly because magnetic tapes do not afford easy skipping to a desired location.

Magnetic erasure of data written to tape can be challenging, as various methods have been developed to recover data from tiny residual magnetic signals. To ensure the irretrievability of sensitive data, tape can also be degaussed, shredded, or recycled at end of life. Additionally, magnetic tape can be burned, while HDDs cannot.

Supply-chain problems have been an issue for magnetic tape. This is a relatively small sector, particularly in contrast to the hard disk storage industry. Several large corporations, including IBM, Sony, Quantum, Hewlett-Packard, Fujifilm, and Western Digital, dominate the magnetic tape sector. The limited number of players supports coordinated development of technology standards (LTO being a good example of this) but can lead to supply disruptions. For example, the availability of LTO tape media was painfully constrained by a long-running Sony-Fujifilm patent dispute over LTO-8 that was only resolved in 2019.14 In addition, Western Digital is the sole tape head supplier for the entire industry. This represents a potential single point of failure in the magnetic tape supply chain, particularly because tape head manufacturing represents a small fraction of Western Digital’s overall revenue. Establishing a new tape head manufacturing capability would improve the sector’s

__________________

12 Ultrium LTO, “Roadmap,” https://www.lto.org/roadmap, accessed December 12, 2023.

13 Information Storage Industry Consortium, 2019, “2019 INSIC Technology Roadmap,” Monroe, VA.

14 C. Mellor, 2019, “LTO-8 Tape Media Patent Lawsuit Cripples Supply as Sony and Fujifilm Face Off in Court,” The Register, May 31, https://www.theregister.com/2019/05/31/lto_patent_case_hits_lto8_supply.

resilience, but even with unlimited financial resources, standing up a new tape head supplier could take as long as 3–5 years due to the limited number of engineers with relevant experience and expertise.

Cost

Total cost of ownership (TCO) estimates are difficult to include without knowing the desired workloads, but as an example, a 2018 study15 compared the TCO and energy consumption of tape storage compared to an HDD-based and cloud-based storage system. The comparison suggests that tape has a significant cost advantage. However, as will be discussed later, tape is often used as part of a tiered storage architecture inside a cold storage solution, with other technologies like SSD and HDD used for hot data requirements and for data ingestion.

Durability

For archival applications, tape is 50 times more durable than disk systems when properly maintained in its recommended storage and operating conditions. Furthermore, tape can be expected to last at least 30 years, if stored in approved archival environmental conditions. Magnetic tape requires specific temperature and humidity controls, potentially increasing the complexity of the storage system and energy costs.

Technology Readiness Level

Magnetic tape is widely deployed across a variety of applications, and as such has a TRL of 9.

NAND-BASED FLASH MEMORY SOLID-STATE DRIVES

Flash memory was invented in the 1980s, approximately three decades after HDDs and tape data storage was introduced. There are two major types of flash memory, NOR flash and NAND flash.16 NOR flash was invented in 1984 and is typically used for code storage, because it is fast enough for a processor to directly execute software or firmware code. NAND flash was introduced in 1987 and is typically used for data storage, typically in conjunction with a flash memory controller or processor in an SSD. The controller, or processor, provides physical to logical data mapping, media management, and error correction functions. NAND flash scaling was achieved through lithography scaling, multi-bit-per-cell technology, and multi-layer, or three-dimensional (3D) technology, leading to increasing complexities for flash-based SSD controllers to achieve scaling density while increasing performance and decreasing cost.

The evolution of flash-based SSDs occurred in three major technology phases. Initially, SSD implementations emulated HDDs, as that was the easiest way to introduce SSDs into the ecosystem in the same form factor and with the same physical and logical interface as an HDD. Subsequently, new SSD form factors and connectors were created to take advantage of SSD compactness and speed, while leveraging pre-existing layers of the software stack for the logical or protocol connectivity. Finally, in the third phase, SSD-optimized protocols such as NVM Express (NVMe)17 were developed to allow the system and software stack to identify and utilize the benefits that SSDs have to offer within a system architecture.

The first commercial flash-based SSD was shipped in 1991. It had a capacity of 20 megabytes (MB) and sold for a price of around $1,000, or $50,000 per terabyte. Given the robust and rugged nature of SSDs, its initial deployments were in military and industrial systems. As cost scaling progressed, the high-performance of SSDs, which offered superior input/output operations per second per dollar, enabled its use in transaction-heavy enterprise applications. Further cost advancements made the

__________________

use of SSDs in entry-level PC applications attractive, where smaller footprint operating systems were used, and adequate capacities were available at an affordable cost point. With further cost-scaling advancements, SSDs found their way into mainstream battery-powered consumer compute applications such as notebooks and laptops. This occurred because SSDs can deliver adequate storage capacity with longer battery life and better system responsiveness than HDDs. Ultimately, SSDs displaced HDDs in enterprise servers as well as most desktop computers as the price points enabled a superior value proposition of capacity, performance, and power consumption. Today, SSDs service most compute storage applications and are projected to ultimately capture all primary storage. However, SSDs are still multiple times more expensive in their acquisition cost compared to HDDs, and thus high-capacity storage use cases continue to favor HDDs, and they represent more than 80 percent of all bits stored in data centers today.18

The flash-based SSD market in 2023 is projected to be approximately $21.8 billion in revenue with 423,000 units shipped, with an average capacity of 855 GB and an average selling price of $60/TB.19 Mainstream PC SSDs represent the largest revenue segment, followed by enterprise server SSDs, enterprise storage SSDs, and industrial SSDs. While today the average mainstream SSD capacities are smaller than HDD capacities, the highest-density SSD in a standard form factor is 100 TB with data center storage SSD of 256 TB available. Read and write speeds of SSDs are in the multi-gigabyte per second (GB/s) range with some exceeding 10 GB/s, compared with HDD speeds of 100–200 MB/s. SSD power consumption has a wide range, depending on interface as well as the number of active NAND. The power consumption ranges from 5–20 watts (W) active, with a typical HDD using 5–10 W active. The power consumption of an SSD is highly dependent on the use case, however, and may be lower or higher than an HDD.

Security

Several flash-based SSDs offer full-disk encryption (FDE) to protect sensitive data storage on the SSD. FDE can be implemented via device or host-side encryption depending on customer preferences and the reason encryption is needed. This is typically paired with crypto-erase functionality that leverages the deletion of the key to effectively make the data on the encrypted drive inaccessible. The most stringent erasure requirements typically prescribe a procedure of multiple complete overwrite passes to ensure that the data are not simply rendered inaccessible but are completely deleted.

The NAND supply chain has gone through a consolidation process that drives supplier concentration, given the tremendous capital intensity, competitiveness, and cyclicality of the NAND flash market. In 2022, the top four suppliers (Samsung; Kioxia and Western Digital; SK Hynix and Solidigm; and Micron) accounted for approximately 95 percent of revenue.20 NAND profitability is currently at perilously low levels and will require a period of recovery to enable a healthy growth path for the overall market going forward.

Reliability

Common wisdom has it that flash-based SSDs like to be “written hot and stored cold.” The relative higher temperature heals the storage mechanism during a write operation but would degrade retention time while data are stored. Enterprise SSDs typically have a 3-month power-off retention time, while client SSDs typically have a 1-year power-off retention time, per Joint Electron Device Engineering Council standard specifications. In addition to a limited number of write cycles, NAND also has a limited number of read cycles because it may cause a read disturb error that could result in

__________________

18 Horizon Technology, 2023, “HDD Remains Dominant Storage Technology,” July 12, https://horizontechnology.com/news/hdd-remains-dominant-storage-technology-1219.

19 Gartner Research, 2023, “3Q23 NAND & SSD: Historic Crash Followed by Inevitable Recovery,” Stamford, CT.

20 Ibid.

a bit flip.21 Additionally, NAND flash is also prone to some lossiness (aka “bit rot”) because the data are stored using electrons on a floating gate or via charge trap. The SSD controller must mitigate the failure mechanisms through media life management and data movement as well as powerful error correction that typically deploys advanced low-density parity-check error correction. The limited number of read and write cycles impacts the expected lifespan of an SSD, with a typical SSD lifespan of around 10 years.

Military customers were among the early adopters of SSDs due to their wide operating temperature range as well as shock and vibration tolerance. The fact that SSDs have no moving parts and store data via electric charge helps to protect against several threat scenarios, although radiation and electromagnetic pulses are areas of potential vulnerability. The most sophisticated SSD controller technology, with appropriate error correction as well as redundancy, can help maximize the reliability of SSDs using the most advanced NAND flash technology.

Limitations

More than three decades of NAND flash scaling has caused a significant reduction in key specifications to achieve desired cost reductions. For example, write-cycle endurance rating scaled from approximately 100,000 cycles for single-level cell NAND flash, to 10,000 cycles in multi-level cell NAND flash, to 1,000 cycles in triple-level cell NAND flash, to 100 cycles in quad-level cell NAND flash with read disturb specs experiencing reductions, with bit scaling as well. While 3D NAND brought further cost-scaling benefits through multi-layer technology, the limits are visible on the horizon. Thus, the use of wafer-to-wafer bonding is the next lever to increase density. SSD controller, or processor, development is becoming increasingly complex, given the ever-increasing levels of sophistication required to ensure that data are stored and correctly, and reliably, retrieved.

Ease of Use

SSDs are generally very easy to use, as they can connect via industry standard interface technology in the various applications. SSDs are typically block-storage devices that can easily mount into a computer system or be integrated into a storage subsystem. SSDs should not be exposed to extreme high temperatures because they may degrade the fidelity of the data stored on them. It is important to power up an SSD from time to time to ensure that the media controller can perform any required housekeeping to preserve the longevity of the data and their safe retrieval in the future.

Practical Viability

SSD technology is the workhorse for primary storage today and broadly available from several suppliers for various use cases and applications. It is to be expected that NAND flash will scale to thousands of layers and through packaging innovations as well as multi wafer-to-wafer bond structures. For example, Samsung has discussed the possibility of the capacity of a single SSD increasing to 1 PB, with pricing to advance to below $20/TB by the end of this decade.

Costs

The average price for an SSD in 2023 is approximately $60/TB. The cost has recently fallen due to current market demand and supply, but SSD pricing is forecast to rebound to $85/TB by the middle of the decade, before continuing to decline to levels as low as sub-$20/TB in the most aggressive scaling scenarios by the end of the decade.22

__________________

21 See, for example, Y. Cai, Y. Luo, S. Ghose, E.F. Haratsch, K. Mai, and O. Mutlu, 2015, “Read Disturb Errors in MLC NAND Flash Memory: Characterization, Mitigation, and Recovery,” paper presented at the 2015 45th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7266871.

22 Tom’s Hardware, 2023, “Samsung Talks 1 Petabyte SSDs: Thousands of Layers, Packaging Innovations,” March 30, https://www.tomshardware.com/news/samsung-talks-1pb-ssds.

SSDs do not require any particular maintenance but typically have a 3–5-year product life that typically is measured by terabytes-written, analogous to a tire tread wear measure in miles driven. SSD energy consumption typically ranges from 0.05–0.5 W for idle, 2–8 W for ready, and 30 W for writing, depending on interface and the number of active NAND die. Cooling energy depends on SSD workloads, but SSDs are typically always active in a data center, and cooling cost can be as much as the cost for the SSD energy consumption.

Scale-out costs for SSDs are heavily dominated by the cost of the SSD. Typically, the acquisition cost for SSDs based on dollars per terabyte is a key measure for cost effectiveness across scaling scenarios. Data center storage rack capacities of several 10 PBs can be achieved with current high-capacity SSDs. Rack capacities of more than 50 PB (using individual 100 TB+ SSDs) and 100 PB+ (using individual 200 TB+ SSDs) seem possible within this decade.

Implementation Challenges

SSDs are ideal for compute storage or primary storage but are not optimized or suitable for long-term storage. Specific operating conditions with only a few write cycles may yield a longer retention, but that would be achieved at a relatively higher price. Thus, SSDs would not be a preferred means to store data for the timescales required by the IC.

One of the critical challenges is the fact that the read/write electronics and the media are inseparable and thus are not ideal for long-term archiving use cases, as typically the read/write electronics are not designed to work for decades but rather for years.

Technology Readiness Level

NAND-based flash SSDs are widely deployed across a variety of applications, and as such have a TRL of 9.

MAGNETORESISTIVE RANDOM ACCESS MEMORY

MRAM is a type of non-volatile memory technology that combines the best features of traditional random-access memory (RAM) and flash memory, while providing a solution for code and data storage. MRAM uses magnetic storage elements to store data, making it fast, durable, and energy efficient. MRAM could be an ideal long-term storage solution for smaller amounts of data that need to be safely stored and quickly available when needed, but it is not a candidate at this time for enterprise-scale archival storage.

MRAM is typically made up of memory cells, each consisting of a magnetic tunnel junction (MTJ) for storing 1 bit and a semiconductor transistor for selection/addressing purposes. The areal density of MRAM is limited by the footprint of the addressing transistors as well as how dense the MTJ elements can be fabricated. Novel semiconductor selector technologies, combined with innovation on MTJ switching techniques and semiconductor chip design approaches beyond two dimensions, hold promise to scale MRAM to 16 gigabit (Gbit) and beyond.

Early MRAM technology was developed by IBM in the late 1980s. MRAM shares core fundamental technology and sensors with HDDs and magnetic tape. As a result, there are many potential synergies in fundamental R&D work, as well as magnetic nanofabrication semiconductor fabricators across these four product lines. The first 4 megabit MRAM was shipped in 2006. As of 2019, the highest-density monolithic MRAM available is 1 Gb spin transfer-torque-MRAM.

Initial MRAM products focused on radiation-hard characteristics have use in military, aerospace, and transport applications. In addition to industrial automation and medical applications, as well as

network and infrastructure markets, MRAM is also serving as journal memory in redundant array of inexpensive disks (RAID23) storage applications in enterprise storage systems.

MRAM is positioned in both random access and code non-volatile memory domains. Its key characteristics include its persistence, ability to maintain memory content without requiring power, and RAM-like performance with low latency. Other characteristics include its endurance, superior durability and high-reliability, making it best-in-class for robust memory storage under extreme conditions.

MRAM integrates well with logic and is typically manufactured in a front end-of-the-line standard complementary metal-oxide semiconductor workflow combined with a back end-of-the-line magnetics workflow in 8” and 12” lines using down to 28 nm lithography for discrete, and down to 16 nm lithography for embedded, MRAM implementations. While MRAM initially made inroads as discrete chips, it has made its way into the mainstream through integration with all major foundries as an embedded offering integrated with logic chips. The focus is on using MRAM as an enhanced replacement for NOR flash with superior characteristics, including scalability to smaller lithography nodes.

In addition to replacing embedded NOR flash, MRAM also has the potential to displace embedded static random-access memory (SRAM), especially for in-memory compute applications. If MRAM can replace SRAM, computers can be instant-on, and the currently required booting process during power-on for computers can be eliminated.

While the embedded MRAM market is difficult to quantify due to the integration with logic on the same chips, the largest discrete MRAM supplier providing the vast majority of MRAM products being shipped is Everspin Technologies, Inc., which reported revenues of $60 million for 2022.24 MRAM is being deployed in mission-critical applications from data centers, industry, the Internet of Things, industrial, automotive, and radiation h-hardened applications.

Security

MRAM is an ideal solution for one-time programmable fuse options and security subsystems and, due to being tamper-proof, is also deployed in gaming applications, such as casino gaming. With its fast-write capability, MRAM enables fast and secure software updates—for example, it performs over-the-air deployments in automotive implementations.

The MRAM supply chain is still evolving, with embedded MRAM offerings at foundries pertaining to node availability as well as functionality. Discrete MRAM is available from one domestic provider as well as a few foreign suppliers.

Reliability

Discrete MRAM has very high reliability and endurance as well as retention and radiation hardness over a broad temperature range. Therefore, it has been used in U.S. missile defense systems, space missions such as the NASA Mars 2020 Perseverance rover, and NASA’s Lucy mission to Jupiter. It is also used in other mission-critical applications such as railway train brakes and automotive applications such as engine controls and electric vehicle power trains.

Limitations

MRAM scaling to smaller lithography nodes (single-digit nanometer and smaller), higher densities (4

__________________

23 RAID also refers to redundant array of independent disks.

24 Everspin Technologies, 2023, “Everspin Reports Unaudited Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2022 Financial Results,” March 1, https://investor.everspin.com/news-releases/news-release-details/everspin-reports-unaudited-fourth-quarter-and-full-year-2022.

GB and higher) and beyond 2D (2.5D and 3D) requires significant investments into 300 mm magnetics nanofabrication semiconductor R&D and high-volume manufacturing fabricators.

Ease of Use

MRAM is very easy to use because it is typically implemented behind a legacy interface that provides non-volatile SRAM or dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) functionality. This leads to relatively low effort design-in requirements.

Practical Viability

MRAM will continue a growth path toward 12 nm lithography nodes. That will provide NOR and SRAM replacement options that are especially sought after in automotive, space, and edge computing applications.

Cost

The upfront price for MRAM is an order of magnitude higher than DRAM but remains competitive for nonvolatile DRAM use cases. Compared to NOR flash, MRAM pricing is a few times higher for high density. Given that NOR flash is hitting scaling limits, MRAM increasingly becomes attractive as higher densities are required for an application.

MRAM allows systems to almost instantly turn off and on and is highly reliable, so the ongoing cost for power is minimal.

In a direct comparison of commodity cost price points, MRAM today is not competitive. However, the TCO in particular implementations has been shown to be superior to other options, especially when all of the characteristics of MRAM are being utilized in a particular application.

Embedded MRAM is increasingly available at large scale through foundries, but discrete MRAM is currently a niche market (measured by revenue) compared to the commodity DRAM, NOR, or NAND markets. However, given the scaling limitations of NOR flash, it is foreseeable that MRAM is well positioned to displace NOR at some point in time as densities increase.

Implementation Challenges

MRAM is easy to implement, but evaluation of a given use case needs to determine whether the overall TCO to use MRAM is attractive versus other possible implementation choices.

MRAM is typically used in embedded logic chips, discrete compute, and embedded compute systems. There are no cloud offerings based on MRAM available today. However, artificial intelligence accelerators could be deployed in cloud data centers using an in-memory compute architecture that leverage MRAM, especially for edge data center infrastructures.

Similar to SSDs, MRAM has ideal use cases but is not optimized or suitable for long-term storage. However, MRAM may have a role to play as part of a larger storage system that requires extremely quick data recall.

Technology Readiness Level

With working systems fully deployed and operational, MRAM has a TRL of 9.

CURRENT OPTICAL STORAGE

Optical data storage uses a physical medium—usually a rotating disc—on which data are recorded by etching patterns that can be read back using a low-power laser. Optical data storage was first developed by IBM in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but various early forms of optical storage were never widely adopted. In 1985, the introduction of the CD-ROM started widespread use of optical storage in consumer-facing products. Subsequent improvements in optical disc technology—the

introduction of rewritable CDs (CD-RW), digital video discs (DVDs), and Blu-ray—have transitioned to primarily consumer use. The dominant use case of optical storage was music and video, but the industry transition to streaming services has led to a decline in the use of optical storage media.

Because optical data storage media are written and read with lasers, they suffer from areal density limitations set by the diffraction limit of the laser light used. Current optical data storage media have significantly lower areal densities than HDDs—for example, Blu-Ray discs have an areal density of 12.5 Gbit/in2.

Currently, the size of the global optical storage market is approximately $2.5 billion,25 although that figure is projected to decline. That figure includes video, CDs, and professional video production.

Optical data storage can store data for a long time—for example, Sony claims that its recent Generation 3 Optical Disc library can store data for 100 years.26 However, at large scales, current optical storage is not competitive with other storage options such as magnetic tape. In 2014, Facebook (now Meta) began using Blu-ray discs for cold storage,27 creating a system of more than 10,000 Blu-ray discs and a robotic “picker” to locate specific discs as needed. Subsequently, this effort seems to have been quietly abandoned, and Facebook introduced Bryce Canyon in 2017, an HDD-based cold storage solution.28 In 2022, Meta’s technical sourcing manager noted that the company operates a large tape archive storage team29; given his recent departure, it seems Meta may have returned to using HDD for cold storage.

Technology Readiness Level

Current optical storage technologies like optical drives, CD, DVD, and Blu-Ray have TRLs of 9.

STORAGE SYSTEM CONSIDERATIONS

Archival storage systems depend on many technologies in addition to the essential processes for writing and reading data. Some of these supporting technologies co-evolve with read/write technologies, such as disk arm positioners, read/write electronics, tape drive motors that start and stop rapidly, cassettes for storing tapes, robotic cassette handlers, and many more. Interfaces between computers and storage devices improve data transfer rates, error checking, reliability, and ability to scale.

To build a storage system, hundreds or thousands of storage components may be connected together. A complete archival storage system might very well include multiple storage technologies in a tiered architecture. For example, as discussed above, magnetic tape might be used as a cold storage solution, where NAND-based flash or disk is used as a buffer for data ingestion, and flash, disk, or MRAM is used for the overall solutions’ hot data requirements.

The capacity, scaling, and speed of the system will depend on the properties of the interfaces of the components and of the connections to them. The useful lifetime of the storage component, which is

__________________

25 Storage Newsletter, 2023, “Recordable Optical Disc Market Decreasing Next Years at 3% CAGR,” updated November 1, https://www.storagenewsletter.com/2023/11/01/recordable-optical-disc-market-decreasing-next-years-at-3-cagr.

26 SONY, 2020, “Sony Launches Generation 3 PetaSite Optical Disc Archive Library with 66 Percent Greater Capacity and 50 Percent Improvement in Archive Performance Versus Previous Generation,” June 3, https://www.sony.com/content/sony/en/en_us/SCA/company-news/press-releases/sony-electronics/2020/sony-launches-generation-3-petasite-optical-disc-archive-library-with-66-percent-greater-capacity-and-50-percent-improvement-in-archive-performance-versus-previous-generation.html.

27 ArsTechnica, 2014, “Why Facebook Thinks Blu-Ray Discs Are Perfect for the Data Center,” January 31, https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2014/01/why-facebook-thinks-blu-ray-discs-are-perfect-for-the-data-center.

28 Engineering at Meta, 2017, “Introducing Bryce Canyon: Our Next-Generation Storage Platform,” March 8, https://engineering.fb.com/2017/03/08/data-center-engineering/introducing-bryce-canyon-our-next-generation-storage-platform.

29 CIOInsight, 2022, “What Do Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, and IBM Have in Common? Tape Storage,” updated February 15, https://www.cioinsight.com/news-trends/tape-storage-amazon-microsoft-meta-ibm.

the smallest replaceable element, will depend not only on properties of its storage medium but on the lifetime and reliability of the associated parts (electronics, motors, power supplies, connectors, etc.).

In a large system, components may fail or exceed their service lives at any time. It may not be possible to replace a failed component due to physical access or because components with compatible properties (interface, capacity, speed, power consumption) are no longer available. The overall storage system must be engineered with such events in mind, for a period of, say, 50 years. This is a significant systems engineering task.

A large archival storage system is managed by a computer and associated software. Although very large storage systems have been custom-built, they are not engineered or operated on for 50-year storage timescales. There are many interlocking functions in a storage system, such as

- Surviving power failures and failure of any single element.

- Duplicating and/or encoding data for redundancy (e.g., RAID).

- Copying data to new or replacement media. Storage components with large capacities may have limited input/output bandwidth and significant failure rates (when thousands of components are considered), and copying can take a while, so most archival storage systems will be constantly copying.

- Adequate redundancy must be established long before the end of life of a storage medium is reached.

- If older data is accessed less frequently than more recent data, migrating old data to storage components with greater capacity but perhaps slower access. Different levels of a storage hierarchy may need to be migrated to new storage technologies over time.

- Assuring security of stored data and controlling and auditing access.

- Allocating data to multiple hardware/software systems so that diversity is a partial defense against external or internal cyberattack.

- Operating several storage systems in collaboration, to provide geographic redundancy, to provide federated access by multiple clients, etc.

- Migrating some or all of the archive to new media or a new system, without suspending storage service.

- Optimizing performance based on measurements of the use of the storage system.

- Optimization may call for replication or migration of some data, for replacement of certain storage devices, etc.

These functions are each subject to algorithms and practices that are improved or customized over time. The current state of some of these functions may not meet the requirements of the intelligence community, for example, security and physical diversity.

Coupled with archiving data is preserving application software that can operate on the data. A commercial relational database will store its data in a proprietary form; saving the data will be useless without the associated software. Of course, the archive could be designed to save only data in “externalized” formats that have accompanying standard public definitions, but there will still be a software migration challenge as standards are retired or replaced.

Although an archival storage system that meets IC needs may not be commercially available today, a custom system could be engineered using today’s technologies. Research programs of vendors and

academics are actively improving the technologies, but a 50-year archive horizon does not get much attention. Institutional stability and procedures for operating and maintaining such an archive will be critically important and are not easy targets for research and experimentation. Because the IC presently operates many large storage systems, its staff is reasonably familiar with the current offerings and technologies available for implementing storage systems and can use their knowledge to select research and investments in new system technologies to meet their needs for a 50-year archive.

The challenges of operating a storage solution evolve with the technologies used. For example, HAMR-based HDDs and 5-bit-per-cell NAND-based flash may require different reliability assumptions than traditional media, and emerging technologies like DNA data storage and silica data storage will require different environmental conditions for optimal long-term storage than tape or HDDs. For these newer technologies, discussed later in this REC, the IC may also find that optimal solutions for writing, storing, and reading data use different architectures and physical infrastructure.

Cost

The TCO of a storage rack in a data center includes the upfront acquisition cost of the storage medium, enclosures, and racks, plus the maintenance and energy cost to operate the rack over its life, and the labor cost and maintenance for continuous data migration once the end of life of a storage medium is reached. Maintenance costs also include running fixity checks and error correction. For some applications, cloud storage may be purchased from a commercial cloud storage provider. For other applications, a public cloud storage provider could provide a private cloud storage solution. For other applications, it may be preferrable for an organization to build its own data centers, which includes hiring and maintaining a data center operations team. The scale of the data storage footprint required, as well as ingress and egress and physical control and security considerations, are major factors in the decision process to determine which solution best addresses need.

Even when building a data center from scratch, an organization must consider whether to purchase just the storage media, or to purchase storage devices, or a whole data rack. For example, some large companies (such as Apple) build SSDs themselves. This requires sufficient scale as well as a highly skilled and experienced workforce. Unless there is significant scale or there are specific physical control or security requirements, it is likely economically advantageous to source storage devices or rack solutions. While commercial cloud providers may not be the solution to some—or most—IC applications, the IC should look to build on best practices developed by these companies whenever feasible.

Storage system–level considerations may also add significant energy and environmental costs, depending on the recall-time requirements and storage media. In a traditional data center, operation of the servers and storage solution may represent only one-quarter of the center’s energy use, with cooling (by far the single largest component), networking hardware, power conversion, and lighting accounting for significant energy use.30

IC member agencies may also find a 2020 National Academies report31 on life-cycle decisions for biomedical data useful. While this report focused on smaller scales than may be relevant for IC use cases, it developed useful workbooks and tools for estimating the costs of data storage.

__________________

30 M. Dayarathna, W. Yonggang, and F. Rui, 2016, “Data Center Energy Consumption Modeling: A Survey,” IEEE Communications Surveys and Tutorials 18(1):732–794.

31 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2020, Life-Cycle Decisions for Biomedical Data: The Challenge of Forecasting Costs, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.