Carbon Utilization Infrastructure, Markets, and Research and Development: A Final Report (2024)

Chapter: 8 Biological CO2 Conversion to Fuels, Chemicals, and Polymers

8

Biological CO2 Conversion to Fuels, Chemicals, and Polymers

8.1 OVERVIEW OF BIOLOGICAL CONVERSION ROUTES FOR CO2 TO ORGANIC PRODUCTS

To achieve net-zero emissions, it is critical to manage carbon flows and consider both strategies for CO2 capture and long-term storage, as well as technologies to replace the emission-intensive processes characteristic of the current petrochemical industries. Biological conversion of carbon into products—either directly from CO2 or indirectly from sugar or other intermediates derived from CO is one such strategy.1 Biological processes occur under ambient conditions and thus have intrinsically lower energy intensity than conventional thermochemical processes, which require high temperatures and pressures. Biological processes are also generally more robust to contaminants and fluctuations in reactant stream quality and composition. Products commonly accessible from biological CO2 utilization via photosynthetic, nonphotosynthetic, and hybrid processes include organic chemicals, lipids, terpenoids, polymer precursors, biopolymers, and food and animal feed. Products derived from bioprocessing often have additional environmental benefits, such as being compostable or biodegradable at end of life, preventing nondegradable plastic waste pollution (Mayfield and Burkart 2023; Nduko and Taguchi 2021; Sirohi et al. 2020).

Despite its positive attributes, native biological CO2 fixation is slow and has low energy conversion efficiency, limiting growth and production rates (Liu et al. 2016). Terrestrial plant photosynthesis in general exhibits less than 1 percent conversion efficiency of light energy into chemical product energy. Algal and cyanobacterial conversion is often limited by light penetration. (Long et al. 2022; Zhu et al. 2010). In conventional biofuel production, photosynthesis converts CO2 into plant-based carbohydrate substrates (e.g., starch, sucrose, cellulose), which are later converted to ethanol and other chemicals through fermentation, with some CO2 as a by-product. Considering the low efficiency of natural photosynthesis and the carbon loss to CO2 during product formation through fermentation, bioproduction using carbohydrates has very low energy efficiency from sunlight. Consequently, substantial amounts of land would be required for bioproduction to replace emission-intensive petrochemical production (Smith et al. 2023). The Department of Energy’s 2023 Billion Ton Report outlines the potential for biomass resources in the contiguous United States to meet some of this demand, including a detailed analysis of non-CO2 routes (DOE 2024).

Direct biological conversion of CO2—the focus of this chapter—aims to combat some of the challenges of native biological fixation. Biological CO2 utilization is defined here as the use of concentrated CO2 (e.g., industrial waste gas

___________________

1 Although out of scope for this report, it is noted that recent efforts have achieved full biomass utilization through carbohydrate and lignin conversion, which represents an indirect route for CO2 utilization in which CO2 captured in plant biomass can be used for fiber, fuels, materials, and chemicals (Liu et al. 2022; Yuan et al. 2022).

SOURCE: Icons from the Noun Project, https://thenounproject.com. CC BY 3.0.

streams or direct air capture CO2) as a feedstock for biochemical production, which can be developed through autotrophic microorganisms (e.g., microalgae or cyanobacteria), acetogenic microbes, or hybrid systems (Figure 8-1). The biochemical production systems discussed in this chapter—including photosynthetic, nonphotosynthetic, and hybrid systems such as electro-bio and cell-free systems—have the potential not only to sequester CO2 but also to possibly help replace highly polluting commodity chemical products with greener alternatives (Zhang et al. 2022), assuming many of the challenges discussed in this chapter are overcome and that adequate market incentives are met. Engineered microorganisms capable of producing commodity chemicals have gained traction as viable alternatives to traditional petrochemical approaches. Expanding feedstock pools, engineering regulatory elements of metabolism, and optimizing conditions are all methods employed to increase productivity in these microbial hosts. It is also critical to explore and advance biomanufacturing technologies that utilize CO2 to produce a diverse range of value-added products.

This chapter addresses the strengths and challenges intrinsic to using CO2 as a substrate for biochemical production and provides an update on biological CO2 utilization to the 2019 National Academies’ report Gaseous Carbon Waste Streams Utilization: Status and Research Needs (NASEM 2019). First, engineering efforts using photoautotrophs such as microalgae and cyanobacteria are discussed. Second, engineering approaches with non-canonical CO2 fixing pathways such as within acetogenic bacteria are outlined. Third, the combination of bioconversion with electro-, thermo-, plasma-, and photo-catalysis is reviewed. These strategies demonstrate potentially more sustainable methods of making industrially relevant carbon-based products with the aid of engineered microorganisms capable of utilizing CO2 to support a net-zero emissions future.

8.2 PHOTOSYNTHETIC PRODUCTION OF CHEMICALS FROM CO2

8.2.1 Existing and Emerging Processes

Synthetic biology and metabolic engineering strive to establish sustainable methods for chemical production through engineered microorganisms.2 These endeavors involve leveraging photosynthetic microorganisms capable of generating valuable chemical commodities from CO2 and light. Microalgae and cyanobacteria—the two

___________________

2 Genetic engineering involves the direct manipulation of an organism’s genes using biochemical methods. Controversy surrounding this technology exists owing to possible ethical concerns related to unknown environmental impacts and long-term health effects; however, the applications discussed herein focus strictly on applications that enhance natural microbial processes, contained in reactors, and do not have any direct pathways to affect human, animal, or environmental health.

key categories of photosynthetic microorganisms under investigation for chemical production—exhibit potential for synthesizing a diverse range of useful compounds, including fuels, polymer precursors, and commodity chemicals.

Microalgae are photosynthetic microorganisms that can naturally fix CO2 10 to 50 times more efficiently than other terrestrial plants (Onyeaka et al. 2021). Their carbon-fixing ability makes microalgae a promising feedstock for biofuels, bioplastics, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and industrial chemicals (Al-Jabri et al. 2022; Cheng et al. 2022; Sirohi et al. 2021). Successful demonstrations of microalgae-based CO2 utilization include antioxidants, anticancer, and antimicrobial compounds, polymers, biocrude, biodiesel, biogas, and hydrogen (Cuellar-Bermudez et al. 2015; Rezvani et al. 2017; Sosa-Hernández et al. 2018). Nonetheless, industrial-scale commercialization of microalgae-based CO2 utilization has been limited and is at low technology readiness level (TRL) (Roh et al. 2020). The predominant challenges for industrial-scale commercialization are use of microalgal biomass, evaluation of the life cycle of microalgae technologies, and development and implementation of a supportive policy and regulatory environment (Miranda et al. 2022).

Cyanobacteria are photosynthetic microorganisms found naturally in water that can fix CO2 twice as efficiently as other plants (Hill et al. 2020). Their natural properties like high specific growth rate, abundant fatty acid and oil content, and other active metabolites make them an attractive non-food biomass source. Successful pilot demonstrations of cyanobacteria-based CO2 utilization include the production of ethanol, butanol, biodiesel, bioplastics, and hydrogen (Agarwal et al. 2022).3 However, differences in outdoor cultivation as compared to ideal indoor conditions, insufficient light or nutrients, contamination in open pond cultivation systems, and inefficiencies in the extraction, purification, and harvest stages have limited scaling from low TRL. Additional challenges include bioreactor design limitations, limits of CO2 solubility in water, and land and water availability and access (Burkart et al. 2019). Photobioreactors that leverage LED lights can potentially produce high-value products and intermediates with high efficiency, but they are limited to small scales (Porto et al. 2022). The next section discusses challenges for CO2 utilization from both types of photosynthetic microorganisms.

8.2.2 Challenges

Despite the growing interest in these photosynthetic microorganisms, challenges persist within the field. A major concern is the inefficiency of photosynthesis and CO2 fixation. Attempts to enhance the central carbon fixation enzyme, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase (RuBisCO), have faced limited success (Cummins 2021). A related challenge is that RuBisCO cannot distinguish effectively between CO2 and O2, resulting in energy-intensive photorespiration caused by the oxidative reaction of RuBisCO (Hagemann and Bauwe 2016). Additionally, at high cell densities, cell shading inhibits photosynthesis, making the design of culture systems more complicated.

To address these challenges of selectivity and low activity, recent studies have explored strategies such as reviving ancestral forms of RuBisCO and drawing inspiration from natural adaptations like the carboxysome, a bacterial microcompartment concentrating RuBisCO with high CO2 concentrations (Kerfeld and Melnicki 2016; Shih et al. 2016). Another approach to enhance chemical production capacity involves supplementing CO2 with carbohydrates as an auxiliary carbon source, enabling photomixotrophy that utilizes carbohydrates in addition to CO2. CO2 fixation efficiency can be improved by redirecting carbohydrate breakdown to the RuBisCO precusor in the Calvin-Benson cycle, promoting faster growth and increased production of target compounds (Kanno et al. 2017). This strategy allows for 24-hour production periods, even in darkness, by fixing CO2 through photomixotrophy. Although many different types of sugars are amenable to this process, xylose—a prevalent sugar in corn stover lysate—has shown promise in enhancing photomixotrophic production of various compounds (Gonzales et al. 2023; Yao et al. 2022). Additionally, cell growth is enhanced by incorporating the nonoxidative glycolysis pathway and deleting genes that elevate the intracellular concentration of acetyl-CoA (Song et al. 2021).

Large-scale culture systems for photosynthetic chemical production are still under development. Various studies are under way to establish a system that enables efficient CO2 fixation and chemical production and is economically viable. They are discussed in detail in other reports (Sun et al. 2020).

___________________

3 These applications are also possible using eukaryotic microalgae (Daneshvar et al. 2022).

8.2.3 Research and Development Opportunities

8.2.3.1 Exploration of Fast-Growing Cyanobacteria

The conventional focus of cyanobacterial chemical production has been on model species such as Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, but efforts to discover faster-growing strains amenable to genetic manipulation are gaining traction. Cyanobacteria like Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 2973, S. elongatus PCC 11801, and S. elongatus PCC 11802 exhibit faster growth and efficient chemical production under specific conditions (Sengupta et al. 2020a, 2020b; Yu et al. 2015). These discoveries not only offer potential improvements for model organisms but also shed light on differences between new and traditional strains.

8.2.3.2 Advances in Genome and Metabolic Engineering Tools

Great progress has been made in photosynthetic chemical production from CO2, but new genetic engineering strategies are needed to enhance the efficiency of CO2 fixation and enable the establishment of economical and scalable production systems. To improve microbial CO2 fixation, it is essential to continue to refine the tools of genetic engineering and to increase understanding of the design principles of photosynthetic metabolism.

Traditional genome modification in cyanobacteria faces limitations owing to polyploidy and antibiotic resistance markers (Griese et al. 2011). The advent of CRISPR gene editing has revolutionized cyanobacterial genome engineering, allowing markerless editing for increased efficiency (Behler et al. 2018). The CRISPR enzyme, Cas9, is toxic in some cyanobacterial species, so alternative enzymes with lower toxicity, such as Cas12a, are being investigated (Ungerer et al. 2018). CRISPR inhibition (CRISPRi) has also been established to knock down the expression of target genes in cyanobacteria (Qi et al. 2013). The Cas9 mutant without the endonuclease activity (dCas9) used in CRISPRi is functional in cyanobacteria, although Cas9 is toxic (Santos et al. 2021). These advances open new possibilities for innovative genome engineering strategies to enhance CO2 fixation and chemical production from CO2.

Photosynthetic carbon metabolism is an intricate process that has undergone evolutionary optimization for cell growth in natural conditions. Utilizing systems biology, including proteomics and metabolomics, is crucial for characterizing photosynthetic carbon metabolism and identifying targets to improve CO2 fixation and product formation. Computational techniques can enable integration of complementary datasets obtained from systems biology and identify higher-level features such as regulation and network characteristics. Owing to the complex and highly interconnected nature of carbon metabolism, understanding the effects of modifications on downstream metabolism or determining necessary genetic modifications for a desired effect is often not a trivial process. Therefore, applying mathematical models becomes essential to describe, understand, and predict system behavior. Through the application of such models, one gains the ability to generate a set of testable hypotheses for system behavior. Machine learning can facilitate the training of mathematical models for better prediction.

Among many additional opportunities in photobiological research and development (R&D), some notable ideas include: light absorption for downstream metabolism (Blankenship and Chen 2013); exploiting waste dissipation processes from excess absorbed light (Niyogi and Truong 2013); and the use of smaller portions of the electromagnetic spectrum (for example, only blue or red light) to drive photosynthesis (Blankenship et al. 2011; Chen et al 2010).

8.2.3.3 Establishment of Large-Scale Cultivation

New cultivation strategies aimed at increasing productivity and CO2 fixation efficiency need to be developed, while simultaneously minimizing the land footprint required for effective CO2 conversion. From low-cost harvesting methods to innovative culture media formulations and robust crop protection measures, advances in cultivation technology are being made (Pittman et al. 2011). Integrating these established technologies with the latest strains that exhibit high CO2 fixation rates and productivity is crucial to optimize overall efficiency. This integrated approach not only ensures a more sustainable and resource-efficient cultivation process, but also meets the broader goals of environmental stewardship and carbon footprint reduction. These synergistic advances in the areas of large-scale cultivation systems need to be explored and implemented, in addition to the more general effects that gas flow management and reactor pressurization may have on productivity.

8.3 NONPHOTOSYNTHETIC PRODUCTION OF CHEMICALS FROM CO2

8.3.1 Existing and Emerging Processes

Chemolithotrophs obtain ATP by oxidizing inorganic compounds instead of relying on solar energy (Kelly 1981). These microorganisms produce NAD(P)H by reversing the electron transport chain, accepting electrons from high redox potential donors. This ability allows them to circumvent challenges such as photorespiration and cell shading faced by photosynthetic organisms.

One class of chemolithotrophs, acetogens, has attracted commercial interest owing to their unique carbon fixation strategy known as the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway (WLP) (Ragsdale 2008). Under anaerobic conditions, the WLP converts H2, CO2, and/or CO into acetyl-CoA, an acyl carrier, generating ATP and acetate for further carbon anabolism (Pavan et al. 2022; Ragsdale 2008; Schiel-Bengelsdorf and Dürre 2012). The WLP comprises two branches: the methyl branch, which reduces CO2 to formate, and the carbonyl branch, driven by the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase (CODH/ACS) enzyme complex, reduces CO2 to CO and catalyzes the condensation of CO to C2 chemicals. Although the natural WLP is not efficient, optimal enzymes for the WLP have been identified through a combination of genome mining, enzymatic characterization, omics approaches, and kinetic modeling (Liew et al. 2022). The engineered WLP can fix CO2 and synthesize various chemicals from CO2. The primary product of the WLP, acetate, is not a particularly desirable product; however, stoichiometric modeling suggests that the WLP is highly efficient in carbon fixation owing to its effective use of reducing power to generate ATP and the low energy cost of producing acetyl-CoA (Fast and Papoutsakis 2012). Acetogens can recapture CO2 generated during glycolysis, establishing a closed loop.

To address the need for greater reducing power, mixotrophic fermentation that uses other substrates in addition to CO2 emerges as a potential solution. Research efforts have targeted systems that can provide the increased reducing power and CO2 reassimilation without carbon catabolite repression (CCR) (Fast et al. 2015; Jones et al. 2016). For example, a mixotrophic fermentation strategy combining syngas and fructose in Clostridium ljungdahlii that aimed to enhance acetone production (Jones et al. 2016; Otten et al. 2022) demonstrated promising results, indicating that CCR was not occurring. Another two-stage lipid biosynthesis process, involving syngas-to-acetate production in Moorella acetecia followed by lipid synthesis in Yarrowia lipolytica, showcased the potential of a gas-to-lipids production scheme (Hu et al. 2013; Ruth and Stephanopoulos 2023). Additionally, a study on co-culturing Clostridium ljungdahlii and Clostridium kluyveri demonstrated efficient synthesis of long-chain alcohols from syngas (Diender et al. 2021; Richter et al. 2016).

Despite inherent limitations and challenges in these approaches (see Section 8.3.2), acetogenic fermentation remains an attractive platform for biological CO2 utilization owing to the efficiency of the WLP and the diverse range of products achievable through co-culturing and genetic modification of the host. The ability to operate at ambient temperatures and pressures further simplifies and makes the scale-up process more cost, environmental, and energy efficient Systems based on algae production only require sunlight for the initial conversion of CO2, whereas hybrid systems require electricity for this same conversion step (for which the availability of renewable electrons is critical). While both types of processes require additional energy for processing and separations, the energy requirements for purely biological systems are generally considered to be lower than chemical or hybrid systems.

8.3.2 Challenges

Although they can avoid challenges faced by photosynthetic organisms, chemolithotrophs have inherent limitations, including the need for multiple substrates, complex physiochemical cellular environments, and electron donors.4 As noted above, acetogens are commercially intriguing owing to their unique carbon fixation strategy employing the WLP. However, carbon conversion yields vary, and a strict dependence on anaerobic conditions is required, restricting the range of products that can be synthesized (Bertsch and Muller 2015; Fast et al. 2015; Kopke and Simpson 2020; Molitor et al. 2016). Photomixotrophic production would alleviate these challenges but

___________________

4 However, the ability of chemolithotrophs to be feedstock-agnostic presents a potential opportunity in geographic flexibility.

poses other limitations like CCR and the need to optimize for multiple substrates. Co-culturing studies showcase the potential of multiorganism production strategies, but also highlight challenges with optimizing conditions for both microorganisms, maintaining co-culture health, and competition for substrates. Regardless of the cultivation strategy, the overall carbon emission impacts have to be considered. For example, acetogens use H2 or CO as electron donors. If these electron donors are generated from natural gas, the platform will be a derivative of petrochemical platform with net-positive carbon emissions. Section 8.4 discusses the alternative option of hybrid systems, where renewable electricity can be used to generate hydrogen and CO to drive acetogen conversion.

8.3.3 R&D Opportunities

R&D opportunities in chemolithotrophic CO2 utilization include optimizing mixotrophic fermentation to address challenges like CCR, exploring synergistic gas-to-liquids production schemes such as those involving various gas-organic substrate combinations, improvements in genetic modification tools, and further developing efficient co-culturing strategies for synthesizing diverse products. Enhancing acetogenic fermentation presents opportunities to overcome inherent limitations and challenges, improve carbon conversion yields, and broaden the range of producible compounds. Additionally, research should focus on scaling up processes and exploring new gas-to-lipids production schemes for lipid-based products. The WLP has the potential to diversify products, and research into new applications of the WLP for synthesizing a wider range of chemicals than just acetate shows further potential in this field. These initiatives collectively aim to advance the efficiency, versatility, and commercial viability of the processes under consideration. Coupling the WLP with further biological conversions that utilize acetate (or other platform chemical product) to achieve higher value-added products is a worthwhile focus for R&D. Today, the most common platform chemical for biological conversion is sugar, which can also be made via biological processes.

8.4 HYBRID BIOLOGICAL SYSTEMS

8.4.1 Existing and Emerging Processes

Recent advances have suggested multiple viable paths to convert CO2 into valuable and emissions-neutral products by combining catalytic processes (e.g., electrocatalysis, thermocatalysis, photocatalysis, or plasmacatalysis) with bioconversion (Gassler et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2016). A variety of catalysis-bio hybrid platforms have been developed, all of which require electron donors, which can be delivered as gas (e.g., hydrogen, CO), electric current, or electron- and energy-carrying soluble molecules (e.g., formate, methanol, acetate, ethanol) (Zhang et al. 2022). Hydrogen and CO are gas intermediates often used to drive acetogen conversion in gas fermentation, as described in Section 8.3. Energy-carrying soluble molecules are further categorized as C1 intermediates (e.g., formate and methanol) and C2 intermediates (e.g., acetate and ethanol). The C2 intermediates are compatible with a broader range of microorganisms than the C1 intermediates (Zhang et al. 2022). With these intermediates, several platforms have been developed by integrating electrocatalysis or thermocatalysis with cell-based or cell-free bioconversion systems. Some of these platforms have demonstrated superior energy conversion efficiency than the natural photosynthesis (Natelson et al. 2018; Ullah et al. 2023).

8.4.1.1 Electro-Bio Hybrid Systems

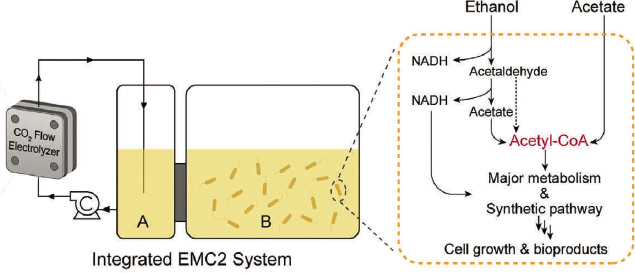

The integration of electrocatalysis with bioconversion for CO2 utilization recently has emerged as a particularly attractive pathway owing to its ambient reaction conditions, potential to achieve higher efficiency and reaction rates, and ability to manufacture diverse products that could replace emission-intensive production of fuels, chemicals, and polymers (see Figures 8-1, 8-2, and 8-3). Because both electrocatalysis and bioconversion can operate at ambient temperature, electro-bio hybrid platforms have lower energy- and carbon-intensity than some other CO2 conversion methods. The use of CO2 as a substrate theoretically enables a higher carbon and energy efficiency compared to sugar-based bioproduction if the system is properly designed to leverage the high efficiency of catalysis (Tan and Nielsen 2022). Additionally, the kinetics or reaction rate also can be more favorable than in natural

NOTES: The pathways in general have three classes. The first class leverages hydrogen and electrons to drive the CO2 reduction and fixation by certain acetogens and chemolithotrophs. The second class first converts CO2 into C1 intermediates like CO, formate, and methanol, and then converts these intermediates to other products. The second class often leverages the unique pathways of acetogens and methylotrophs. The third class utilizes the more biocompatible C2 intermediates like acetate and ethanol, which can be amenable to a much broader groups of microorganisms. Hydrogen and CO are gas intermediates. The assimilation pathways, net reducing equivalents, net ATP generation per carbon, steps to central metabolite acetyl-CoA (as molecular building block), numbers of electrons carried, reaction enthalpy, mass transfer capacity, and biocompatibility are compared.

SOURCE: Modified from Zhang et al. (2022), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chempr.2022.09.005. CC BY 4.0.

photosynthetic processes, considering that the rapid catalytic processes bypass the slow carbon concentrating and RuBisCO carbon fixation steps (Zhang et al. 2022). Furthermore, an electro-bio platform can potentially leverage a wide array of diverse biological pathways to produce a wide range of chemicals, polymer precursors, and fuels, including longer carbon chain molecules that are more difficult or energy-intensive to access by conventional thermochemical, electrochemical, or photochemical conversion routes (Zhang et al. 2022).

Electro-bio hybrid systems have been developed using C1 intermediates, gas intermediates, and C2+ (i.e., biocompatible) intermediates (Figure 8-2). These various platforms for integrating catalysis and bioconversion have their advantages and drawbacks, as discussed in the following sections.

8.4.1.1.1 Electro-Bio Hybrid Systems with C1 Intermediates

In 2012, Li et al. first demonstrated the concept of an electro-bio conversion system, in which an electrocatalytic CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) was coupled with bioconversion using Ralstonia eutropha H16 to produce isobutanol (Li et al. 2012). This study showed that electrocatalytically derived formate was consumed by the microorganism and observed that hydrogen generated from electrocatalysis also might have helped to drive the CO2 fixation and conversion in R. eutropha. The integration of electrocatalytic conversion of CO2 into methanol and subsequent bioconversion also has been proposed (Guo et al. 2023). For both formate and methanol, substantial

metabolic engineering has been carried out to enable the conversion of these C1 intermediates into various bioproducts (Chen et al. 2020). Despite the progress, recent work also indicates that it is very challenging to achieve high titer with the C1 soluble intermediates owing to the incompatibility with most of the industrial strains and the limited pathway kinetics for bioproducts generation (Figure 8-2). Even though gas fermentation with acetogens has been scaled up, most of the commercially relevant strains like E. coli, P. putida, and S. cerevisiae are not amenable to convert C1 intermediates into bioproducts at appreciable rate, efficiency, and titer. Natural methylotrophs and formatotrophs have been explored for more than half a century, yet large-scale production using these organisms remains challenging owing to a limited genetic toolbox and low fermentation titers. To overcome these challenges, recent work has focused on engineering platform industrial microorganisms into methylotrophs to achieve bioconversion (Reiter 2024). In fact, recent work has engineered E. coli to carry out methylotroph-type of conversion, yet the product titer remains low (Chen et al. 2020; Kim, 2020). Various pathways including a reductive glycine pathway and ribulose monophosphate (RuMP) cycle have been engineered or evolved in E. coli. Despite this progress, the inherent pathways for assimilation and conversion also pose challenges for C1 intermediate utilization considering the multiple steps needed to convert to central metabolic building blocks like acetyl-CoA (Figure 8-2), which limits the kinetics and rate of conversion. All these will translate into economic and scalability challenges of the platforms. Recent work has shown that it is possible to engineer and evolve E. coli to convert methanol into polyhydroxybutyrate (Reiter 2024), yet the titer and rate need to be further improved in future work. In order to utilize C1 intermediates more efficiently in electro-bio conversion, it is critical to study further how to engineer balanced and efficient conversion routes from these intermediates to a diverse range of products. Another option would be to leverage electrocatalysis, engineering electrocatalytic systems to produce more biocompatible and higher carbon products such as acetate, propionic acid, butyric acid, or even pyruvate, allowing the use of platform industrial microorganisms for bioconversion in proceeding steps.

8.4.1.1.2 Electro-Bio Hybrid Systems with Gas Intermediates

Hydrogen and CO have been used as the electron donors and intermediates in electro-bio hybrid systems for CO2 conversion. In 2016, Liu et al. developed a system where electrocatalytically generated hydrogen drove the R. eutropha conversion of CO2 into polyhydroxybutyrate (Liu et al. 2016). Electrocatalytic hydrogen-driven CO2 conversion can achieve very high energy efficiency, but challenges with gas-to-liquid transfer may limit large-scale production. Other systems have been established for electro-bioconversion using CO and other intermediates (e.g., see Tan and Nielsen 2022). The CO-based platform is essentially the same as the nonphotosynthetic microorganisms discussed in Section 8.3. The CO can be derived from anaerobic digestion or CO2 electroreduction. Overall, the proposed platforms can use CO, hydrogen, and CO2 as substrates in various combinations with certain microorganisms, which opens various opportunities for CO2 conversion to diverse molecules (Tan and Nielsen 2022).

8.4.1.1.3 Electro-Bio Hybrid Systems with Biocompatible Intermediates

The electro-bio platform relies heavily on the effective integration of electrocatalysis and fermentation. Recent advancements have demonstrated that two- and three-carbon (C2+) intermediates derived from a CO2RR have much better compatibility with biological systems than gas or C1 intermediates, as more microbes, in particular, the industrial microorganisms like Psuedomonas putida can be used (see, e.g., Hann et al. 2022 and Figure 8-2). For example, Zhang et al. (2022) designed an integrated electro-bio conversion system, where a membrane electrode and phosphate buffer electrolyte enabled a CO2RR to produce C2+ intermediates in a biocompatible environment. The synergistic design of catalysts, electrode, electrolyte, electro-bioconversion reactor, and microbial strains have enabled rapid microbial conversion of ethanol, acetate, and other intermediates from electrocatalytic CO2RR into bioplastics in an integrated system (Figure 8-3).5 This work and a recent study of a related photo-electro-bio inte-

___________________

5 Bioplastics are a type of plastic derived from renewable biomass sources. Examples of bioplastics include polylactic acid (PLA), which is derived from corn starch or sugarcane, and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), produced by bacteria through fermentation of sugar or plant oils. Another example is polyethylene derived from sugarcane ethanol, known as bio-based polyethylene. These bioplastics offer more sustainable alternatives to conventional plastics made from nonrenewable resources.

NOTES: The figure provides a general overview of an integrated electro-bioconversion system, where the electrocatalytic CO2RR is carried out in the CO2 flow electrolyzer, and the produced C2 intermediates are fed into a bioreactor with two chambers (A and B). In this particular design, Chamber A contains the acetate, ethanol, and other CO2RR products, but no bacteria. The membrane between Chambers A and B allows the CO2RR-produced intermediates to transport freely to Chamber B, but does not allow the transport of bacteria from Chamber B to Chamber A. The microbial fermentation thus only happens in Chamber B and does not interfere with the electrocatalysis. The microbial engineering will convert ethanol and acetate to acetyl-CoA in few steps, which will then be converted to broad products. The same principle of this design can be broadly applied with different configurations, using different bacteria, intermediates, storage, and integration strategies for CO2RR intermediates feeding into bioreactor.

SOURCE: Modified from Zhang et al. (2022), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chempr.2022.09.005. CC BY 4.0.

gration achieved solar energy conversion efficiency to biomass of 4–4.5 percent, which is better than the terrestrial plant photosynthesis rate (Hann et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2022). The relatively high energy conversion efficiency suggests the potential for these platforms to use low-cost renewable electrons to drive the conversion of CO2 into various valuable products with limited land use.

8.4.1.2 Other Catalysis-Bioconversion Hybrid Systems

Beyond electro-bio conversion, thermocatalysis, plasmacatalysis, and photocatalysis all could be integrated with bioconversion. For example, Cai et al. (2021) demonstrated a route to convert CO2 to starch by combining thermocatalytic CO2 conversion to methanol with subsequent methanol conversion to starch through cell-free enzymatic systems. Semiconductor nanoparticles have been used to harvest sunlight to drive the bacteria Moorella thermoacetica to convert CO2 to acetate (Sakimoto et al. 2016). Even though the titer and efficiency are still far from being commercially relevant, the study thus opens new avenues on how photocatalysis can be integrated with bioconversion to achieve CO2 conversion to broad chemical products and polymer products (Hann et al. 2022). In principle, plasmacatalytic CO2RR products can be converted into chemicals and polymers by bioconversion, too.

8.4.1.3 Cell-Free Hybrid Systems

A cell-free system is characterized by a lack of any cell walls or membranes or native DNA, potentially conferring benefits for product monitoring and purification. Cell-free systems integrate multiple enzyme steps in vitro to carry out a cascade of reactions for converting intermediates into different products. Cell-free systems also have the potential to remove competing pathways, resulting in higher efficiency (Yang et al. 2023). For the bioconversion component of a hybrid system, cell-free systems can be used in place of cell-based bioconversion, such as the abovementioned example of CO2-to-starch conversion developed by Cai et al. (2021). Another example utilizes a cell-free system to convert electrocatalytic CO2RR-derived ethanol to a chemical as a pharmaceutical precursor, although the yield is rather low (Jack et al. 2022). Cell-free systems can integrate with both photocatalysis and

electrocatalysis, yet the photocatalytic integration mainly has yielded shorter carbon chain products. Regardless the route of integration, electron donors need to be available for CO2RR, and these electron donors can be electrons or CO2-derived energy dense intermediates like ethanol or CO (Jack et al. 2022).

8.4.2 Challenges

Despite the progress of hybrid CO2 conversion systems, significant scalability, economic, and technical challenges remain in advancing them. For example, building scalable integrated reaction systems when combining bioconversion with thermo-, plasma-, and photo-catalytic processes is very challenging. In the thermocatalytic-bio hybrid system developed by Cai et al. (2021), separate reactors and steps were required for the thermocatalysis and bioconversion, and the cell-free enzyme reactions involved four different steps, without system integration. Integrated reactor and process design will be difficult for thermocatalytic and plasmachemical processes owing to the temperature constraints and incompatible reaction phases (e.g., gas/solid phase for thermochemical or plasmachemical catalysis versus liquid phase for bioconversion). To integrate photocatalysis with bioconversion, a remaining challenges is the availability of biocompatible intermediates, as photocatalytic CO2RR generally yields C1 intermediates. Substantial R&D needs to be carried out to address these challenges in order to achieve system integration and improve the economics and scalability of hybrid conversion of CO2.

For cell-free hybrid systems, the design of redox-balanced pathways to convert CO2RR intermediates into targeted end products remains difficult. In particular, the reductant generated from the conversion of energy-dense intermediates like ethanol has to be sufficient to drive the downstream reactions to produce end products. Besides the reductant balance, most of the biological synthesis pathways require ATP. In biological systems, ATP is usually generated through a proton gradient across the membrane. Recent breakthroughs in membrane-free ATP generation could empower the design of a broader range of cell-free ATP generation from electricity (Luo et al. 2023). Enzyme stability and production costs also currently prevent cell-free systems from being utilized together with catalytic processes to achieve commercial relevance. Additionally, challenges related to scale up of cell-free systems include resource depletion or over-saturation, as well as system poisoning owing to accumulation of harmful by-products (Batista et al. 2021). For example, the CO2-to-starch system developed by Cai et al. (2021) achieved bioconversion through four separate steps, each with a group of enzymes lasting only for four hours. Substantial research is needed to advance cell-free systems for the integration with catalytic processes. Computational methods and machine learning could be helpful in identifying metabolic bottlenecks (Batista et al. 2021).

8.4.3 R&D Opportunities

Hybrid systems that integrate bioconversion with various catalytic strategies have substantial potential to overcome limitations in the efficiency of natural systems. Nevertheless, substantial scientific and technology development are needed to improve efficiency, enhance scalability, decrease cost, and reduce life cycle carbon emissions. For hybrid systems using C1 intermediates, research on metabolic engineering and synthetic biology can help to improve conversion efficiency, kinetics, and titer. For gas fermentation, the systems are limited by microorganism selection—many conventional industrial strains along with their engineered functional modules cannot be used. Genetic engineering tools and pathways for gas-fermenting bacteria will need to be developed. Gas fermentation also has to overcome the fundamental limits of gas-to-liquid mass transfer, which can be accomplished by higher pressures, although this introduces new safety considerations in reactor design and higher energy costs. Pilot projects will be important to evaluate whether the current platforms can be commercially viable.6 The technical barriers to improved economic and life cycle outcomes will have to be understood and overcome.

Among different systems, electro-bioconversion systems with biocompatible C2+ intermediates have substantial potential owing to their high efficiency, biocompatibility with the industrial strains, and improved system integration (see Figure 8-2). The C2 intermediates from electrocatalytic CO2RR can improve electron, mass, and

___________________

6 Lanzatech produces ethanol at commercial scale using syngas (see Kopke and Simpson 2020; Pavan et al. 2022).

energy transfer, shorten the steps to acetyl-CoA, and thus have the potential to improve the efficiency, titer, productivity, and ultimately economics and scalability of the electro-bio hybrid systems (see Figure 8-2 and Zhang et al. 2022). While recent progress has paved the way for efficient electron-to-molecule conversion, research needs to be carried out to improve performance, evaluate efficiency, and achieve commercial deployment. First, better fundamental understanding of electrocatalyst structure–function relationships is needed to improve Faradaic efficiency, product yield, and catalyst stability; reduce costs; and generate longer-carbon-chain products, particularly in biocompatible electrolytes. Current state-of-the-art systems can achieve 50–70 percent yield of acetate from CO2, which is counted by calculating the number of carbon atoms in the acetate end products divided by the number of carbon atoms from CO2 feeding into the system. In particularFor example, CO2 electrolysis to CO has been demonstrated in a high-temperature solid oxide electrolysis system with nearly 100 percent yield (Hauch et al. 2020). For the CO electrolysis to acetate, multiple groups have reported a faradaic efficiency up to 80 percent. A recent report of a tandem reactor shows a CO-to-acetate faradaic efficiency of 50 percent with ethylene as the only side product of CO at about 30 percent. This selectivity can be maintained at a relatively high conversion (50–70 percent) (Overa et al. 2022). The recent one-step CO2-to-C2 intermediate reactor can achieve over 25 percent Faradaic efficiency and high catalyst stability for CO2 conversion to soluble C2 molecules without requiring rare earth metal catalysts in phosphate buffers (Zhang et al. 2022), yet the yield for C2+ intermediates needs to be further improved as compared to the tandem reactors.

Recent advances have shown that membrane electrodes and reactors together with bio-compatible electrolytes could achieve an integrated electro-bio system for the conversion of CO2 to value- added chemicals, albeit at lower Faradaic efficiency than other state-of-the-art technologies in the field (Chen et al. 2020). Future catalyst design to convert CO2 to C2 and longer carbon chain molecules instead of C1 molecules will enable better integration with bioconversion and improved efficiency, yield, stability, and scalability.

Additionally, the bioenergetic, biochemical, and metabolic limits for microbial conversion of CO2RR products need to be better understood. For years, microbial engineering focused on carbohydrate substrates, which later expanded to industrially relevant compounds like lignin and glycerol (Lin et al. 2016). Substantial investment, particularly from the Department of Energy, recently expanded the understanding of formate and methanol metabolism, empowering the engineering of new conversion pathways and capacity in industrially relevant microbial strains like E. coli (Chen et al. 2020). Substantial work has been carried out to engineer methanol and formate conversion, yet the conversion efficiency and rate remain low (Chen et al. 2020). Recent research has focused on the bioconversion of electrocatalytic CO2RR-derived C2 and C3 intermediates like acetate, ethanol, and propionic acids. These compounds need fewer steps to central metabolism and carry more energy and electrons, so the study of their use as bioconversion feedstocks for longer carbon chain products can help to advance strategies to improve conversion efficiency.

Last, bioconversion reactor design, system integration, and evaluation are needed if these systems are to reach commercial scale. It is important to build a reactor interface in which electrocatalytically derived methanol, formate, acetate, ethanol, and other products can be efficiently converted to diverse longer carbon chain products. Such integration is not trivial. For example, acetate and formate often form as salts during electrocatalysis, which could inhibit any concomitant microbial conversion. Among different possible intermediates, gas fermentation with CO has achieved commercialization. The integration of electrocatalysis-derived CO and hydrogen with anaerobic fermentation at scale also needs to be evaluated to understand the economic and life cycle impacts.

8.5 PRODUCTS ACCESSIBLE FROM BIOLOGICAL CO2 UTILIZATION

8.5.1 Commodity Chemicals, Fuels, Food, and Pharmaceuticals

Photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic organisms have been engineered to produce a wide range of fuels, commodity chemicals, food chemicals, and pharmaceutical chemicals. Fuels and chemicals are compelling circular economy targets, as sustainable routes to producing these valuable products will be required in a net-zero future. Most of the target products of biological systems are not durable in nature. CO2 also can be used to produce animal

TABLE 8-1 Example Compounds Produced in Engineered Photosynthetic Organisms

feed and food ingredients through bioconversion; however, larger scale opportunities rely mostly on microbial fermentation, algae cultivation, and nutrient recovery from waste streams (see Chapter 2).

The availability of a general platform for producing chemicals in photosynthetic organisms lags far behind that in heterotrophic model organisms such as yeast and E. coli. Both photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic organisms utilize a similar core framework for essential metabolic processes, yet vast differences in substrate utilization and growth capacity exist between these microorganisms. The elucidation of factors and behaviors unique to photoautotrophic organisms would be useful in biochemical production. Table 8-1 provides a list of chemicals that have been produced in engineered photosynthetic organisms, expanded from the list in NASEM (2019). Nonphotosynthetic and hybrid systems can produce these same classes of chemicals yet can achieve a much broader product portfolio owing to extensive metabolic engineering efforts. These other products include many platform chemicals and polymer precursors, such as succinic acid and ethyl glycol (Chen et al. 2016; Gao et al. 2016).

However, scale up of many bioconversion processes remains a challenge—many of these products are produced in very small quantities at laboratory scale only. Furthermore, many of the chemicals are available at low cost from other routes, so any future processes must provide products at competitive prices.

Besides chemicals and polymers, CO2 conversion to food and feed can be another route to reduce carbon emissions. For photosynthetic systems, some cyanobacteria and algal species have long been considered as protein sources for human consumption (e.g., Spirulina) and animal feed. Furthermore, recent advances have highlighted that hybrid systems can be used to produce food at a much higher efficiency than photosynthesis (Hann et al. 2022).

8.5.2 Polymer Precursors and Polymers

The plastics industry accounts for 4.5 percent of global carbon emissions (Cabernard 2022). Replacing emission-intensive processes and products will be critical to reduce the emissions associated with plastics manufacturing. Traditional bioplastics include products like polyhydroxyalkanoates, polyhydroxybutyrates, and polylactic acids, which are produced from biological sources and can be biodegradable or biocompostable (provided the waste infrastructure allows for the right degradation conditions, and in the case of compostables, a separate collection mechanism from recyclable plastics). These materials could replace emission-intensive plastics while also addressing daunting environmental challenges like accumulation of nondegradable waste and microplastics.

Photosynthetic, nonphotosynthetic, and hybrid microbial systems have been explored for biopolymer or polymer precursor production using CO2 as the feedstock. Microbial conversion has been used widely for the production of polymer precursors such as 1,4-butanediol, 2,3-butanediol, succinic acid, isoprene, and others (Lee et al. 2011). Butanediol and succinic acid are precursors to polybutylene succinate. Microorganisms also have been engineered to produce polymer precursors like 2,3-butanediol (Kanno et al. 2017; Oliver et al. 2013) and succinic acid (Lan and Wei 2016; Treece et al. 2023). Considering their metabolic diversity, all three systems could be used to produce the precursors for a wide range of polymers.

For hybrid systems, an even more diverse range of microorganisms can be exploited to produce diverse polymers and polymer precursors from CO2. R&D support could empower various hybrid platforms to be used broadly for producing polymer precursors from CO2. Future research is needed on both fundamental and applied aspects of these systems. From a fundamental perspective, understanding the carbon flux control and bioenergetics of polymer precursor production will be helpful in identifying new pathways, improving productivity, conversion efficiency, and titer. From the applied side, advancement of new reactor designs and processes, and integration of carbon capture technologies will deliver integrated modules that directly convert CO2 to industrially relevant precursors or polymers. The commercial deployment of these modules could have substantial impact on carbon emissions reductions, considering that they may replace current emissions intensive processes.

8.6 CONCLUSIONS

Many carbon-based products today are produced from bioconversion processes via an agriculture–fermentation route; however, terrestrial plants have limitations in CO2 conversion owing to the low efficiency of photosynthesis and challenges with subsequent conversions to value-added chemicals. This chapter has presented processes for direct biological conversion of CO2, whereby autotrophic microorganisms, acetogenic microbes, or hybrid systems use concentrated CO2 sources as a feedstock for chemical production. These processes can combat some of the challenges associated with native biological fixation, but additional R&D is required to improve their performance and enable commercial-scale chemical production.

For photosynthetic systems, significant progress has been made in chemical production from CO2. However, new engineering strategies are needed to enhance the efficiency of CO2 fixation, enabling the more economical and scalable production systems. CO2 fixation can be improved with continued refinement of genetic engineering tools and increased understanding of the design principles of photosynthetic metabolism. The intricate and inter-

connected nature of carbon metabolism makes predicting the effects of modifications challenging. Using mathematical models becomes crucial to describe and understand system behavior, aiding in the generation of testable hypotheses. Machine learning can enhance the training of these models for improved predictions. Furthermore, new cultivation strategies need to be developed to substantially improve productivity and thus reduce the land required for CO2 conversion—for example, light-emitting diode (LED) technologies for reactor design (Porto et al. 2022). Other cultivation technologies, including low-cost harvest, media, and crop protection, have been developed but need to be integrated with the new strains with high CO2 fixation rate. As in other systems, it is critical to carry out techno-economic assessments (TEAs) and life cycle assessments (LCAs) to evaluate the commercial potential and environmental impacts of photosynthetic CO2 conversion platforms. This need is underscored by the many commercial challenges of systems biology-based efforts to produce commodity chemicals (Blois 2024).

Chemolithotrophs obtain ATP by oxidizing inorganic compounds and reversing the electron transport chain, offering an alternative energy source to photosynthetic organisms. The WLP in acetogens converts H2, CO2, and/or CO into acetyl-CoA, demonstrating efficiency in carbon fixation. Despite the limitations discussed above, acetogenic fermentation remains attractive for CO2 utilization, with potential applications like mixotrophic fermentation and co-culturing strategies. Challenges include substrate dependency and competition. Research opportunities include optimizing mixotrophic fermentation, exploring gas-to-liquids production, and scaling up processes for broader product synthesis. Alternative options like hybrid systems using renewable electricity for electron donor generation are also possible, emphasizing the ongoing efforts to enhance efficiency, versatility, and commercial viability in chemolithotrophic CO2 utilization.

Substantial R&D needs to be carried out to build efficient, economic, and scalable hybrid systems. For gaseous intermediates, demonstrating integration with catalytic processes at scale will be the priority. For C1 intermediates, continued microbial engineering research could lead to improvements in productivity and titer of integrated hybrid systems. For C2+ biocompatible intermediates, electro-bio hybrid systems have potential to achieve commercial and scalable production owing to their compatibility with many industrially relevant microorganisms, as well as improved electron, energy, and mass transfer, and fewer steps to acetyl-CoA. However, substantial research is still required in four primary areas: (1) development of efficient, selective, high-yield, cost-effective, and stable electrocatalysts for C2+ intermediates; (2) substantial advances in the fundamental understanding of metabolic and biochemical limits for C2+ intermediate conversion; (3) development of scalable reactor designs for system integration; and (4) development of highly efficient alternative bioconversion systems, including cell-free systems.

For all three routes (photosynthetic, nonphotosynthetic, and hybrid), TEAs and LCAs will be needed. Much work has been done on these assessments for algae biofuels, yet limited research has been carried out for hybrid and nonphotosynthetic systems (Handler et al. 2016; Liew et al. 2022). TEA and LCA carried out at the bench scale may identify the drivers and barriers for improving the system efficiency and economics. These assessments become even more important for pilot projects to determine commercial and environmental viability. For gas fermentation and photosynthetic systems, pilot and demonstration research and the relevant TEAs and LCAs are important to evaluate if these technologies could achieve commercialization and have a real impact on reducing carbon emissions.

8.6.1 Findings and Recommendations

Based on the above research needs, the committee makes the following findings and recommendations:

Finding 8-1: Opportunities to produce diverse products—Biological and hybrid systems have enormous opportunities to convert CO2 to a variety of products for a circular carbon economy and carbon storage. However, key challenges exist, including low photosynthetic efficiency, low overall energy and carbon efficiency, and system integration and bioreactor design optimization. Both biological and hybrid systems merit further exploration because of their potential to perform selective conversions of CO2 to a wide variety of products under mild conditions.

Recommendation 8-1: Coordination of fundamental and applied research is needed—Substantial fundamental and applied research needs to be conducted in order to understand and overcome biochemical, bioenergetic, and metabolic limits to higher reaction rates, conversion efficiency, and product titers. Various Department of Energy offices, including the Office of Science, Bioenergy Technologies Office, and Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, as well as the Department of Defense, should coordinate fundamental and applied research to accelerate the advancement of efficient and implementable biochemical systems for carbon conversion.

Finding 8-2: Low productivities and titers are a barrier to commercialization—Most biochemical conversion of CO2 work is still at an early stage, focused primarily on process optimization and not commercial products. The productivities and titers (mostly on the order of 1 mg/liter) for chemicals produced by these systems are too low to make commercialization of this technology appealing. Further improvements are needed to gain a sophisticated understanding of carbon metabolism and develop more efficient genetic manipulation tools (e.g., systems modeling with machine learning and cultivation optimization).

Recommendation 8-2: Support for advances in genetic engineering, systems modeling, and fundamental research is critical—New genetic engineering strategies must be developed to enhance the efficiency of CO2 fixation, enabling the establishment of economical and scalable production systems. Continued refinement of genetic engineering tools and better understanding of the design principles of carbon metabolism are needed to improve CO2 fixation. Additionally, systems modeling and machine learning can be exploited to optimize nutrient input, CO2 delivery, light penetration, and other conditions to achieve higher productivities. Last, fundamental research to improve enzyme stability and the scalability of redox balanced systems is needed to make hybrid systems commercially viable and scalable. The Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Office of Science and the National Science Foundation should continue to support fundamental research on these topics, and DOE’s Bioenergy Technologies Office, Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, and Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy should support the related applied research.

Finding 8-3: Electro-bio hybrid systems require improvements in process engineering and techno-economic and life cycle assessments—Electro-bio hybrid systems for converting CO2 to valuable chemicals have shown promise, especially to biocompatible intermediates like ethanol and acetate, but are still in their infancy. Achieving economically viable electro-bio conversion will require development of advanced technologies in catalyst design, microbial engineering, and process and reactor engineering. Besides improvements in process engineering, techno-economic and life cycle assessments are needed to evaluate the technical feasibility, commercial viability, and environmental impact of biochemical processes as compared to alternatives, such as chemical processes.

Recommendation 8-3: Explore electrocatalysts that operate under biologically amenable conditions with high activity, selectivity, and stability—The National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, Bioenergy Technologies Office, Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, and Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy should support fundamental and applied research on the development of electrocatalysts that operate under biologically amenable conditions with high activity, selectivity, and stability. Systems that produce and utilize biocompatible (i.e., nontoxic, multicarbon) intermediates should be prioritized.

Recommendation 8-4: Develop microorganisms and cell-free systems that can efficiently produce target chemicals via intermediates derived from electrocatalysis—The National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, Bioenergy Technologies Office, Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, and Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy should support fundamental

and applied research on the development of microorganisms and cell-free systems that can efficiently produce target chemicals from catalysis-derived intermediates under conditions amenable to electrocatalysis. These efforts should include systems biology understanding of the limitations for the conversion of various electrocatalysis-derived intermediates, in particular, biocompatible intermediates, as well as the synthetic biology engineering of microorganisms and cell-free systems for efficient conversion of these intermediates to chemicals, materials, and fuels.

Recommendation 8-5: Evaluate reactor design and system integration for hybrid systems—The Department of Energy’s Bioenergy Technologies Office, Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy, and Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management should support research to investigate system integration and scale up of catalysis and bioconversion. The reactor and process design need to be optimized to the specific intermediates and desired products, and techno-economic and life cycle assessments need to be carried out to evaluate the economic, environmental, and emissions impacts of hybrid systems.

Finding 8-4: Integration of thermocatalytic and photocatalytic CO2 conversion with bioconversion—Only limited laboratory/research-scale examples have been reported of hybrid processes for CO2 utilization that couple thermo- or photocatalytic CO2 reduction with bioconversion. More research is needed to explore such systems—in particular, to improve and evaluate their efficiency, economics, and scalability.

Recommendation 8-6: Advance prototype hybrid systems to integrate thermocatalytic or photocatalytic CO2 conversion with bioconversion—The Department of Energy’s Bioenergy Technologies Office, Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy, and Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management should support research to investigate the concept of integrating thermocatalytic or photocatalytic conversion of CO2 into intermediates, and subsequently convert the intermediates via bioconversion to diverse chemical and polymer products. The evaluation of system efficiency and economics will help to assess whether such integrated systems are feasible.

8.6.2 Research Agenda for Biological CO2 Conversion to Organic Products

Table 8-2 presents the committee’s research agenda for biological CO2 conversion to organic products, including research needs (numbered by chapter), and related research agenda recommendations (a subset of research-related recommendations from the chapter). The table includes the relevant funding agencies or other actors; whether the need is for basic research, applied research, technology demonstration, or enabling technologies and processes for CO2 utilization; the research theme(s) that the research need falls into; the relevant research area and product class covered by the research need; whether the relevant product(s) are long- or short-lived; and the source of the research need (chapter section, finding, or recommendation). The committee’s full research agenda can be found in Chapter 11.

TABLE 8-2 Research Agenda for Biological CO2 Conversion to Organic Products

| Research, Development, and Demonstration Need | Funding Agencies or Other Actors | Basic, Applied, Demonstration, or Enabling | Research Area | Product Class | Long- or Short-Lived | Research Themes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-A. Pathway modeling and metabolic engineering of microorganisms to overcome biochemical, bioenergetic and metabolic limits to enhance the efficiency, titer, and productivity of photosynthetic, nonphotosynthetic, and hybrid systems. | DOE-BES DOE-BER DOE-BETO DOE-FECM |

Basic Applied |

Biological | Chemicals Polymers |

Short-lived | Metabolic understanding and engineering | Fin. 8-1 Rec. 8-1 |

| Reactor design and reaction engineering | |||||||

| Recommendation 8-1: Coordination of fundamental and applied research is needed—Substantial fundamental and applied research needs to be conducted in order to understand and overcome biochemical, bioenergetic, and metabolic limits to higher reaction rates, conversion efficiency, and product titers. Various Department of Energy offices, including the Office of Science, Bioenergy Technologies Office, and Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, as well as the Department of Defense, should coordinate fundamental and applied research to accelerate the advancement of efficient and implementable biochemical systems for carbon conversion. | |||||||

| 8-B. New, more efficient genetic manipulation tools must be developed to enhance the efficiency of CO2 fixation and improve the understanding of carbon metabolism. Computational modeling and machine learning can also be exploited to this end. | DOE-BES DOE-BER NSF |

Basic | Biological | Chemicals | Short-lived | Metabolic understanding and engineering | Fin. 8-2 Rec. 8-2 |

| Genetic manipulation | |||||||

| Computational modeling and machine learning | |||||||

| 8-C. Improved enzyme efficiency, selectivity, and stability, along with multienzyme metabolon design to overcome biochemical limits for photosynthetic, nonphotosynthetic, and hybrid systems. | DOE-BES DOE-BER NSF DOE-BETO DOE-FECM DOE-ARPA-E |

Basic Applied |

Biological | Chemicals Polymers |

Short-lived | Fundamental knowledge | Fin. 8-1 Fin. 8-2 Rec. 8-1 Rec. 8-2 |

| Computational modeling and machine learning | |||||||

| Metabolic understanding and engineering | |||||||

| 8-D. Improved enzyme stability and scalability of redox-balanced systems to facilitate demonstration and scale up of cell-free and hybrid systems. | DOE-BES DOE-BER NSF DOE-BETO DOE-FECM DOE-ARPA-E |

Basic Applied |

Biological | Chemicals Polymers |

Short-lived | Fundamental knowledge | Rec. 8-2 |

| Reactor design and reaction engineering | |||||||

| Integrated systems | |||||||

| Recommendation 8-2: Support for advances in genetic engineering, systems modeling, and fundamental research is critical—New genetic engineering strategies must be developed to enhance the efficiency of CO2 fixation, enabling the establishment of economical and scalable production systems. Continued refinement of genetic engineering tools and better understanding of the design principles of carbon metabolism are needed to improve CO2 fixation. Additionally, systems modeling and machine learning can be exploited to optimize nutrient input, CO2 delivery, light penetration, and other conditions to achieve higher productivities. Last, fundamental research to improve enzyme stability and the scalability of redox balanced systems is needed to make hybrid systems commercially viable and scalable. The Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Office of Science and the National Science Foundation should continue to support fundamental research on these topics, and DOE’s Bioenergy Technologies Office, Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, and Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy should support the related applied research. | |||||||

| Research, Development, and Demonstration Need | Funding Agencies or Other Actors | Basic, Applied, Demonstration, or Enabling | Research Area | Product Class | Long- or Short-Lived | Research Themes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-E. Improve fundamental understanding of electrocatalyst design to increase efficiency, selectivity, and product profile control under biocompatible conditions. | DOE-BES DOE-BER NSF DOE-BETO DOE-FECM DOE-ARPA-E |

Basic Applied |

Biological—Hybrid Electro-bio | Chemicals Polymers |

Short-lived | Fundamental Knowledge Catalyst innovation and optimization |

Fin. 8-3 Rec. 8-3 |

| Recommendation 8-3: Explore electrocatalysts that operate under biologically amenable conditions with high activity, selectivity, and stability—The National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, Bioenergy Technologies Office, Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, and Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy should support fundamental and applied research on the development of electrocatalysts that operate under biologically amenable conditions with high efficiency, selectivity, and stability. Systems that produce and utilize bio-compatible (i.e., nontoxic, multicarbon) intermediates should be prioritized. | |||||||

| 8-F. Develop microorganisms and cell-free systems compatible with intermediates derived from electrocatalysis. | DOE-BES DOE-BER NSF DOE-BETO DOE-FECM DOE-ARPA-E |

Basic Applied |

Biological—Hybrid Electro-bio | Chemicals Polymers |

Short-lived | Microbial engineering | Rec. 8-4 |

| Recommendation 8-4: Develop microorganisms and cell-free systems that can efficiently produce target chemicals via intermediates derived from electrocatalysis—The National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, Bioenergy Technologies Office, Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, and Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy should support fundamental and applied research on the development of microorganisms and cell-free systems that can efficiently produce target chemicals from catalysis-derived intermediates under conditions amenable to electrocatalysis. These efforts should include systems biology understanding of the limitations for the conversion of various electrocatalysis-derived intermediates, in particular, biocompatible intermediates, as well as the synthetic biology engineering of microorganisms and cell-free systems for efficient conversion of these intermediates to chemicals, materials, and fuels. | |||||||

| 8-G. Optimization of hybrid systems via evaluation of reactor design. | DOE-BETO DOE-ARPA-E DOE-FECM |

Applied Demonstration |

Biological—Hybrid | Chemicals Polymers |

Short-lived | Integrated Systems | Rec. 8-5 |

| Reactor design and reaction engineering | |||||||

| Recommendation 8-5: Evaluate reactor design and system integration for hybrid systems—The Department of Energy’s Bioenergy Technologies Office, Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy, and Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management should support research to investigate system integration and scale up of catalysis and bioconversion. The reactor and process design need to be optimized to the specific intermediates and desired products, and techno-economic and life cycle assessments need to be carried out to evaluate the economic, environmental, and emissions impacts of hybrid systems. | |||||||

| 8-H. Feasibility study for integrating thermocatalytic or photocatalytic CO2 conversion with bioconversion to evaluate the efficiency, economics, and scalability. | DOE-ARPA-E DOE-FECM DOE-BETO |

Applied | Biological—Hybrid | Chemicals Polymers |

Short-lived | Reactor design and reaction engineering | Rec. 8-6 |

| Integrated Systems | |||||||

| Recommendation 8-6: Advance prototype hybrid systems that integrate thermocatalytic or photocatalytic CO2 conversion with bioconversion—The Department of Energy’s Bioenergy Technologies Office, Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy, and Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management should support research to investigate the concept of integrating thermocatalytic or photocatalytic conversion of CO2 into intermediates, and subsequently convert the intermediates via bioconversion to diverse chemical and polymer products. The evaluation of system efficiency and economics will help to assess whether such integrated systems are feasible. | |||||||

NOTE: ARPA-E = Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy; BER = Biological and Environmental Research; BES = Basic Energy Sciences; BETO = Bioenergy Technologies Office; DOE = Department of Energy; FECM = Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management; NSF = National Science Foundation.

8.7 REFERENCES

Agarwal, P., R. Soni, P. Kaur, A. Madan, R. Mishra, J. Pandey, S. Singh, and G. Singh. 2022. “Cyanobacteria as a Promising Alternative for Sustainable Environment: Synthesis of Biofuel and Biodegradable Plastics.” Frontiers in Microbiology 13:939347.

Aikawa, S., A. Nishida, S.-H. Ho, J.-S. Chang, T. Hasunuma, and A. Kondo. 2014. “Glycogen Production for Biofuels by the Euryhaline Cyanobacteria Synechococcus sp. Strain PCC 7002 from an Oceanic Environment.” Biotechnology for Biofuels 7(1):88. https://doi.org/10.1186/1754-6834-7-88.

Al-Jabri, H., P. Das, S. Khan, M. AbdulQuadir, M.I. Thaher, K. Hoekman, and A.H. Hawari. 2022. “A Comparison of Bio-Crude Oil Production from Five Marine Microalgae—Using Life Cycle Analysis.” Energy 251:123954.

Amendola, S., J.S. Kneip, F. Meyer, F. Perozeni, S. Cazzaniga, K.J. Lauersen, M. Ballottari, and T. Baier. 2023. “Metabolic Engineering for Efficient Ketocarotenoid Accumulation in the Green Microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii.” ACS Synthetic Biology 12(3):820–831. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.2c00616.

Amer, M., E.Z. Wojcik, C. Sun, R. Hoeven, J.M.X. Hughes, M. Faulkner, I.S. Yunus, et al. 2020. “Low Carbon Strategies for Sustainable Bio-Alkane Gas Production and Renewable Energy.” Energy and Environmental Science 13(6):1818–1831. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0EE00095G.

Atsumi, S., W. Higashide, and J.C. Liao. 2009. “Direct Photosynthetic Recycling of Carbon Dioxide to Isobutyraldehyde.” Nature Biotechnology 27(12):1177–1180. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1586.

Batista, A., P. Soudier, and M. Kushwaha, J.-L. 2021. “Optimizing Protein Synthesis in Cell-Free Systems, A Review.” Engineering Biology 5(1):10–19. https://doi.org/10.1049/enb2.12004.

Behler, J., D. Vijay, W.R. Hess, and M.K. Akhtar. 2018. “CRISPR-Based Technologies for Metabolic Engineering in Cyanobacteria.” Trends in Biotechnology 36(10):996–1010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.05.011.

Bertsch, J., and V. Müller. 2015. “Bioenergetic Constraints for Conversion of Syngas to Biofuels in Acetogenic Bacteria.” Biotechnology for Biofuels 8(1):210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-015-0393-x.

Blankenship R.E., and M. Chen. 2013. “Spectral Expansion and Antenna Reduction Can Enhance Photosynthesis for Energy Production.” Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 17(3):457–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.03.031.

Blankenship, R.E., D.M. Tiede, J. Barber, G.W. Brudvig, G. Fleming, M. Ghrardi and W. Zinth. 2011. “Comparing Photosynthetic and Photovoltaic Efficiencies and Recognizing the Potential for Improvement.” Science 332(6031):805–809. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1200165.

Blois, M. 2024. “Biomanufacturing Isn’t Cleaning Up Chemicals: Synthetic Biology Firms Promised a Low-Carbon Industry, But So Far They Haven’t Delivered.” Chemical and Engineering News 102(12). https://cen.acs.org/business/biobased-chemicals/Biomanufacturing-isnt-cleaning-chemicals/102/i12.

Brey, L.F., A.J. Włodarczyk, J.F. Bang Thøfner, M. Burow, C. Crocoll, I. Nielsen, A.J. Zygadlo Nielsen, and P.E. Jensen. 2020. “Metabolic Engineering of Synechococcus sp. PCC 6803 for the Production of Aromatic Amino Acids and Derived Phenylpropanoids.” Metabolic Engineering 57(January):129–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymben.2019.11.002.

Burkart, M.D., N. Hazari, C.L. Tway, and E.L. Zeitler. 2019. “Opportunities and Challenges for Catalysis in Carbon Dioxide Utilization.” ACS Catalysis 9(9):7937–7956.

Cabernard, L., S. Pfister, C. Oberschelp, and S. Hellweg. 2022. “Growing Environmental Footprint of Plastics Driven by Coal Combustion.” Nature Sustainability 5:139–148. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00807-2.

Cai, T., H. Sun, J. Qiao, L. Zhu, F. Zhang, J. Zhang, Z. Tang, et al. 2021. “Cell-Free Chemoenzymatic Starch Synthesis from Carbon Dioxide.” Science 373(6562):1523–1527. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abh4049.

Cazzaniga, S., F. Perozeni, T. Baier, and M. Ballottari. 2022. “Engineering Astaxanthin Accumulation Reduces Photoinhibition and Increases Biomass Productivity Under High Light in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii.” Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts 15(1):77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-022-02173-3.

Chauhan, A.S., A.K. Patel, C.-W. Chen, J.-S. Chang, P. Michaud, C.-D. Dong, and R.R. Singhania. 2023. “Enhanced Production of High-Value Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs) from Potential Thraustochytrid Aurantiochytrium sp.” Bioresource Technology 370(February):128536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2022.128536.

Chen, F.Y.-H., H.-W. Jung, C.-Y. Tsuei, and J.C. Liao. 2020. “Converting Escherichia Coli to a Synthetic Methylotroph Growing Solely on Methanol.” Cell 182(4):933–946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.010.

Chen, M., M. Schliep, R.D. Willows, Z.-L. Cai, B.A. Neilan and H. Scheer. 2010. “A Red-Shifted Chlorophyll.” Science 329(5997):1318–1319. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1191127.

Chen, Z., J. Haung, Y. Wu, and D. Liu. 2016 “Metabolic Engineering of Corynebacterium Glutamicum for the de Novo Production of Ethylene Glycol from Glucose.” Metabolic Engineering 33:12–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymben.2015.10.013.

Cheng, P., Y. Li, C. Wang, J. Guo, C. Zhou, R. Zhang, Y. Ma, et al. 2022. “Integrated Marine Microalgae Biorefineries for Improved Bioactive Compounds: A Review.” Science of the Total Environment 817:152895.

Chisti, Y. 2007. “Biodiesel from Microalgae.” Biotechnology Advances 25(3):294–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.02.001.

Choi, S.Y., J.-Y. Wang, H.S. Kwak, S.-M. Lee, Y. Um, Y. Kim, S.J. Sim, J. Choi, and H.M. Woo. 2017. “Improvement of Squalene Production from CO2 in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 by Metabolic Engineering and Scalable Production in a Photobioreactor.” ACS Synthetic Biology 6(7):1289–1295. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.7b00083.

Cuellar-Bermudez, S.P., J.S. Garcia-Perez, B.E. Rittmann, and R. Parra-Saldivar. 2015. “Photosynthetic Bioenergy Utilizing CO2: An Approach on Flue Gases Utilization for Third Generation Biofuels.” Journal of Cleaner Production 98:53–65.

Cui, Y., S.R. Thomas-Hall, E.T. Chua, and P.M. Schenk. 2021a. “Development of High-Level Omega-3 Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA) Production from Phaeodactylum tricornutum.” Journal of Phycology 57(1):258–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.13082.

Cui, Y., S.R. Thomas-Hall, E.T. Chua, and P.M. Schenk. 2021b. “Development of a Phaeodactylum tricornutum Biorefinery to Sustainably Produce Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Protein.” Journal of Cleaner Production 300:126839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126839.

Cummins, P.L. 2021. “The Coevolution of RuBisCO, Photorespiration, and Carbon Concentrating Mechanisms in Higher Plants.” Frontiers in Plant Science 12:662425. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.662425.