Carbon Utilization Infrastructure, Markets, and Research and Development: A Final Report (2024)

Chapter: 2 Priority Opportunities for CO2- or Coal WasteDerived Products in a Net-Zero Emissions Future

2

Priority Opportunities for CO2- or Coal Waste–Derived Products in a Net-Zero Emissions Future

2.1 CARBON FLOWS IN A NET-ZERO EMISSIONS FUTURE AND PATH TO CO2-DERIVED PRODUCTS

Carbon-based materials derived from biogenic and fossil carbon currently play essential roles in our lives and the economy. Decomposition from decay or combustion of these materials leads to excess flows of CO2 into the atmosphere, resulting in accumulating concentrations of CO2, especially when the material was originally fossil derived. In a net-zero future, carbon flows will be in a global equilibrium so that CO2 no longer accumulates in the atmosphere. Reducing emissions and CO2 removal are needed to bring atmospheric CO2 concentrations to levels that support stabilizing the global climate at acceptable conditions for human life, and then maintain those lower, stable concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere. Carbon flows in the economy, and the associated CO2 emissions, will be greatly reduced by zero-carbon replacements for many products, especially fuels. However, carbon-based materials cannot be entirely eliminated because they (1) will continue to be part of natural and engineered biological and geological carbon cycles; (2) will continue to be necessary components of many products important in daily life; and (3) can be used to store carbon away from the atmosphere in durable products, or engineered and natural sequestration. CO2 utilization can play a role in creating sustainable, circular, or net-zero-emissions; carbon-based systems for our future material needs; alongside other sustainable carbon feedstocks like biomass or recycled material. This chapter focuses on the market opportunities for CO2 utilization in a net-zero future.1 This report examines what carbon-based materials will be needed in a net-zero future, possible sources of sustainable carbon feedstocks for those materials, and what role CO2 could play in supplying sustainable carbon.

Carbon-based biomass (24.6 gigatonnes [Gt]) and fossil hydrocarbons (15.1 Gt) represent nearly 40 percent of global resource flows today, with the remainder being minerals and ores (50.8 Gt, and 10.1 Gt, respectively) (de Wit et al. 2020, Figure 1). Carbon is not just an ingredient but is in fact the key element in such products as fuels, plastics, fertilizers, chemicals and chemical intermediates, and elemental carbon materials. Today, carbon-based chemical, fuel, and material products are dominantly manufactured with fossil carbon feedstocks,2 so at the end of life, their consumption, disposal, or decay adds net-positive CO2 emissions to the atmosphere. Using alternative feedstocks that enable circular carbon flows for carbon-based products is a key strategy for reducing

___________________

1 While this chapter focuses on CO2 utilization market opportunities, priority products from coal waste are also considered, especially critical minerals. The report covers coal waste utilization opportunities in detail in Chapter 9.

2 Feedstocks are material inputs to industrial processes to generate a product.

fossil carbon emissions to the atmosphere. These feedstocks must be derived from sources or materials with low or zero life cycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and integrated into industrial processes in a more sustainable way.3 Examples of carbon feedstocks with lower life cycle emissions include biomass, recycled or waste carbon products such as plastics, captured CO and CO2, biogas, and municipal solid waste.4 Another important class of materials that can use CO2 feedstocks is CO2-derived mineral carbonates incorporated into construction materials, which do not traditionally incorporate CO2, but where CO2 can be incorporated as long-duration stored carbon.5 During the transition to net-zero, an alternative to circular carbon feedstocks is the continued use of fossil feedstocks with compensatory capture and sequestration to prevent or remove an equivalent full life cycle amount of CO2 emissions from the atmosphere. This report is tasked with examining a circular carbon future, and so this possibility of linear fossil production with offsetting is noted but not explored in depth. The report is also tasked to examine coal waste utilization opportunities, which are addressed in Section 2.2.3 and Chapter 9.

This chapter describes the market opportunities for products that will use captured CO2 or coal waste as feedstocks to provide useful carbon-derived products in a net-zero future. Products fall into two classes: durable storage materials, with lifetimes greater than 100 years, and circular carbon materials, with lifetimes less than 100 years. The product lifetime distinction is important for understanding the two classes’ climate impact. Durable storage materials will act as long-term sinks for carbon and could become instrumental in achieving an overall net-zero carbon future. Circular carbon materials will enable the sustainable cycling of nonfossil carbon in both natural and human-made systems, an essential aspect of moving from an extractive model of carbon mining and waste deposition into the atmosphere to a net-zero future with substantial climate and economic benefits.

There is no consensus on the stable need for carbon-based products in a net-zero future. Product volumes depend heavily on technology potential, the pace of transition, population and economic growth, available resources (CO2, enabling, and competing), and policy choices based on priorities for decarbonization and other societal goals. Durable storage materials and circular carbon materials are distinct in their growth potential. Most durable storage materials have significant carbon utilization growth potential: they are currently not produced in large quantities (e.g., carbon fiber, nanotubes), have undeveloped yet significant potential for applications in new markets (e.g., carbon black in concrete, direct use of coal waste in construction materials), or have production method alternatives that incorporate CO2 as a new ingredient, rather than a replacement for fossil carbon (e.g., concrete, aggregates). Because of their growth potential and the future need for carbon removal in a net-zero future, durable storage materials could result in both cost-effective removal of carbon from open environments and production of revenue-generating products at scales of Gt per year.

Short-lived, circular carbon materials to replace fossil-derived fuels and chemicals have a divergent growth trajectory, with some products expected to shrink and others expected to grow. In a net-zero future, some current hydrocarbon markets are expected to largely disappear and be replaced by zero-carbon solutions, notably electric power replacing fuels for ground transportation (NASEM 2023a). For example, the daily use of gasoline fuel in the United States is about 8 million barrels (EIA 2024). Within the fuels class, the production of aviation fuels will remain a large-volume need that could be met with CO2 conversion (NASEM 2023b). Demand for other essential short-lived carbon products (e.g., chemicals and fertilizers) is expected to continue growing and can be integrated into a circular economy based on alternative carbon feedstocks, including CO2. Within the chemicals class, this report distinguishes chemical intermediates from end products to emphasize their versatile role in the chemical industry. For example, ethylene or ethanol could be used as intermediates in the production of polymer material or aviation fuel. Figure 2-1 shows one estimate of (1) the embedded carbon in fuels for energy and transport, and in materials and chemicals in 2020 and 2050, and (2) a detailed description of the carbon embedded in chemicals

___________________

3 Chapter 3 discusses life cycle assessment as applied to carbon utilization.

4 It is also conceivable that some carbon-based products could be replaced in the future with materials that use silicon or sulfur as the backbone atom, but these options will not be addressed in this report (Barroso et al. 2019; Kausar et al. 2014; Petkowski et al. 2020).

5 In this report, concrete and aggregates are considered carbon-derived materials, even though they traditionally do not use carbon as a feedstock. This helps to reduce the significant carbon burden created by life cycle emissions associated with construction materials (Park et al. 2024).

SOURCE: Kähler et al. (2023).

and derived materials globally.6,7,8 The analysis indicates that fuel demand will drop by 50 percent in the energy sector and 90 percent in the transport sector. Demand for chemicals and materials is projected to double by 2050. When focused on the subset of materials and chemicals that includes chemicals and derived materials, especially polymers, the total carbon demand was 550 Mt annually in 2020, with 88 percent of that derived from fossil material, 8 percent derived from bio-based materials, and less than 5 percent being recycled or CO2-derived (0.03 percent) (see Figure 2-1). In 2050, 25 percent of carbon demand for chemicals and derived materials is projected to be sourced from CO2. Table 2-1 describes the committee’s assessment of the priority products for a net-zero future. These include both durable storage and circular carbon materials.

The following sections describe existing markets and anticipated growth for three use cases for CO2 or coal waste feedstocks: (1) incumbent products that could be replaced by products made from new carbon sources (e.g., sustainable aviation fuels, polymers, or chemicals and intermediates); (2) products that traditionally are not made from fossil carbon (e.g., concrete, aggregates) but that could incorporate CO2 as a feedstock; and (3) products for which a current market is small but could grow substantially in a net-zero future (e.g., carbon fiber as a substitute for steel and aluminum). Specific market considerations for key product categories are analyzed in detail. Relevant factors for the market introduction of products from new carbon feedstocks are discussed, including access and availability to new feedstocks, suitable conversion technologies and infrastructure, consumer demand and acceptance, and regulatory environments. Sections on cost and financial risk are followed by a discussion of the need for techno-economic and life cycle assessments as well as analyses of the risk of unintended consequences. (Further material on these aspects is covered in Chapters 3 and 4 of this report.) The chapter then concludes with a summary of findings and recommendations.

2.2 MARKET OPPORTUNITIES FOR CO2-DERIVED PRODUCTS

2.2.1 Factors That Impact Ease of Making Products from CO2

In principle, all hydrocarbon fuels and chemicals, and many other materials, including inorganic carbonates, elemental carbon materials, and plastics, can be synthesized from CO2. However, only some products and markets are likely to be attractive for investment in CO2 conversion processes, relative to other sustainable carbon feedstock alternatives. The costs of producing specific products via various CO2 utilization pathways versus competing pathways and feedstocks must be considered. Competing sustainable pathways include substituting the product with zero-carbon alternatives like electricity and hydrogen (most relevant for fuels) and manufacturing the product with other non-fossil carbon feedstocks like biomass or recycled carbon wastes. Uncertainties in future policy, market, and regulatory environments, as well as unknowns related to technological advancements, make it impossible to predict and compare future costs of producing specific products from different feedstocks. However, the physicochemical properties of CO2 and potential CO2-derived products provide some guidance on the ease of making different classes of products from CO2 versus production from either incumbent net-positive emission feedstocks, or other net-zero emission feedstocks.

___________________

6 Embedded carbon is the carbon present in the molecules or materials that constitute products. It differs from embodied carbon, which describes the life cycle carbon emissions associated with a product.

7 As defined in Kähler et al. (2023), chemicals and derived materials are organic chemicals and polymers originating from the global chemical industry, including human-made fibers and rubber. This does not include chemicals derived from the heavy oil fraction (bitumen, lubricants, and paraffin waxes), nor does it include wood, pulp and paper, or natural textiles. The total estimated global demand for carbon embedded in chemicals and derived materials is approximately 550 megatonnes (Mt) per year, and 1200 Mt per year when the additional classes of materials and chemicals are included. None of the analyses in Kähler et al. (2023) include global embedded carbon in fuel products, such as gasoline, diesel, aviation fuel, natural gas, or coal.

8 The future 2050 scenario for renewable carbon-based fuels, chemicals, and derived materials outlined in Kähler et al. (2023) assumes that demand for carbon-based fuels in the energy sector is reduced by 50 percent through use of electricity, hydrogen, and solar heating. Transportation carbon needs reduce by 90 percent due primarily to electrification and some hydrogen fuel. Demand increases by 100 percent, assuming a combined annual growth rate of 2.5 percent, for chemicals and derived materials. In this scenario, the shares of the renewable carbon sources for chemicals and derived materials are estimates based on ambitious rates of recycling (55 percent of embedded carbon), biomass limited by planting areas (20 percent), and the remainder of embedded carbon produced from CO2 utilization (25 percent).

TABLE 2-1 Committee’s Assessment of Priority Products from CO2

| Product Class | Example Priority Products | Competitors to CO2-Derived Production in a Net-Zero Future | Current Global Production and Future Demand (gigatonnes [Gt] per year, year of estimate)a | Climate Benefits (lighter blue = lower climate benefit, darker blue = higher climate benefit) |

Conversion Technology | Market Driver and Advantages of CO2 Feedstock | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durable carbon storage or circular carbon product | Amount of CO2 used (tCO2/tonne product)a | Global scale (Gt per year, estimated in 2050)a | ||||||

| Fuels | Jet fuel Marine fuel Lipids | Biomass-derived carbon fuels Electrification Hydrogen Ammonia | Jet fuel 0.305 (2020) 3.07 (2050) |

Circular | 3–6 (Jet fuel) | 3.07 (Jet fuel) | Chemical Biological |

|

| Marine fuel 0.3 (2020)b |

|

|||||||

| Inorganic Construction Materials | Concrete Aggregates | Incumbent construction materials (conventional concrete, aggregates, steel, aluminum, wood) Coal waste–derived products | Concrete 7 (2020) 32.3 (2050) |

Durable | 0.001–0.05 (Concrete) 0.087–0.44 (Aggregates) |

32.3 (Concrete) 119 (Aggregates) |

Mineralization |

|

| Aggregates 45 (2020) 119 (2050) |

||||||||

| Polymers | Polycarbonates Polyurethanes Polylactic acid Polyhydroxyalkanoate |

Biomass-derived polymers Recycling | Polycarbonates 0.0015 (2007)c 0.024 (2020) |

Circular or Durable | 0.05–0.25 (Polyurethane) |

0.06 (Polyurethane) |

Chemical Biological |

|

| Polyurethanes 0.06 (2050) |

||||||||

| Agrochemicals Including Fertilizers | Urea | Biomass-derived agrochemicals | 0.13 (2019)d 0.27 (2032)e |

Circular | 0.73f | Chemical |

|

|

| Chemicals and Chemical Intermediates | Chemical products: CO Methanol Ethylene Formic acid Bioproducts: Butanediol Succinic acid Lactic acid |

Biomass-derived chemicals Recycling | Methanol 0.110 (2022)g 0.432 (2050) |

Circular | 1.28–1.5 (Methanol) 0.49–0.96 (Formic acid) |

0.432 (Methanol) 0.25 (Ethylene)h 0.0140 (Formic acid) |

Chemical Biological |

|

| Ethylene 0.168 (2020)g 0.25 (2050)h |

||||||||

| Formic acid 0.00078 (2020) 0.0140 (2050) |

||||||||

| Elemental Carbon Materials | Carbon black Carbon fiber Carbon nanotubes Graphene | Methane-derived elemental carbon materials Biomass-derived elemental carbon materials Coal waste | Carbon black 0.014 (2020) 0.07 (2050) | Circular or Durable | 3.7–4.2 (Carbon black) |

0.07 (Carbon black) | Chemical |

|

| Food and Animal Feed | Spent microbes | Low-impact animal and plant food production | Animal feed 0.337 (2020) 1.9 (2050) |

Circular | 0.5–0.7 | 1.9 | Biological |

|

a Unless otherwise noted, data are from Sick et al. (2022b).

b From Statista Research Department (2023).

c From Neelis et al. (2007).

d From IEA (2019).

e From Chemanalyst (2023b).

f From Bazzanella and Ausfelder (2017).

g From CAETS (2023).

h From IEA (2018).

NOTE: The Climate Benefits column is color-coded, where light blue indicates low benefit, blue indicates medium benefit, and dark blue indicates high benefit.

SOURCES: Based on data from Bazzanella and Ausfelder (2017); CAETS (2023); Chemanalyst (2023b, 2023c); IEA (2019); Kähler et al. (2023); Mallapragada et al. (2023); Neelis et al. (2007); Sick et al. (2022b); Statista Research Department (2023).

TABLE 2-2 Standard Gibbs Free Energy to Convert CO2 and Water to Reduced Productsa

| Product | Reaction | ΔG0rxn (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon monoxide | CO2 (g) → CO (g) + 1/2O2 (g) | 257 |

| Formic acid | CO2 (g) + H2O (l) → HCOOH (l) + 1/2O2 (g) | 270 |

| Methanol | CO2 (g) + 2H2O (l) → CH3OH (l) + 3/2O2 (g) | 703 |

| Ethanol | 2CO2 (g) + 3H2O (l) → C2H5OH (l) + 3O2 (g) | 1326 |

| Ethylene | 2CO2 (g) + 2H2O (l) → C2H4 (g) + 3O2 (g) | 1331 |

| Ethane | 2CO2 (g) + 3H2O (l) → C2H6 (g) + 7/2O2 (g) | 1468 |

a All thermodynamic quantities are calculated as described in Nitopi et al. (2019), using data from the NIST Chemistry Webbook (Linstrom and Mallard n.d.) and Lange’s Handbook (Dean 1999).

CO2 is a highly oxidized, single-carbon, and relatively unreactive feedstock. It can be transformed into products via low energy, non-reductive pathways where the carbon remains highly oxidized, such as into inorganic and organic carbonates, polycarbonates, urea, and carboxylic acids (Martín et al. 2015). CO2 can also be converted into reduced carbon products, such as hydrocarbons and alcohols, via higher energy pathways (Shaw et al. 2024). Table 2-2 shows the energy required to form several reduced carbon products, with higher Gibbs free energy representing more thermodynamically difficult reactions (the related electrochemical reaction energetics are shown in Table 7-2) (Nitopi et al. 2019). All reactions are thermodynamically unfavorable (positive free energy) under standard conditions, which is to be expected from reductive transformations of CO2 and water to form hydrocarbons and alcohols, and the most reduced and longer carbon chain products are more challenging thermodynamically.

The cost of making products depends both on the fundamental thermodynamics of conversion processes as well as reaction kinetics, and a variety of technology- and market-specific technical and economic factors. Kinetically, formation of single-carbon products is easier than multi-carbon products, which require challenging multi-step transformations. Improved catalysis, reaction design, and systems design can improve reaction kinetics (selectivity, rate, and yield). Sections 2.2.2 and 2.2.3 further describe the demand-side and supply-side market considerations for CO2 utilization, and section 2.2.4 describes market considerations by product class. Chapter 7 examines the technology readiness (Figure 7-3) and compares scaling factors (Section 7.2.2.2) for processes to convert CO2 to certain priority chemical intermediates and final products, providing an example of technical and economic factors to consider when selecting a conversion pathway for a particular product.

2.2.2 Demand for Products Derived from CO2

The carbon-based product system will need to transform to one that can be net-zero-emitting while continuing to provide the remaining product services to the economy without relying on fossil carbon feedstocks. Future markets for short-lived, circular carbon products derived from CO2 will be dependent on the demand for fuels, chemicals and chemical intermediates, and other such products; by the potential to supply such products from different sustainable feedstocks and will reflect restructuring of chemical markets based on competition with zero-carbon substitutes. Many of today’s carbon-containing products, including most fuels, chemicals, and plastics, are derived from fossil carbon (petroleum, natural gas, and coal). Short-lived products emit their fossil carbon into the atmosphere during use or after disposal. In the future, a major class of these carbon-containing materials, hydrocarbon fuels for land- and sea-based transport, heating, and electricity generation, will largely disappear owing to improved zero-carbon options, and the limits placed on emissions that are likely to be required to achieve net-zero. Although projections for the rates of reduction in fossil fuel use vary, an example scenario is shown in Figure 2-2. The International Energy Agency’s (IEA’s) Net-Zero-Emissions Scenario projects a decline of fossil-carbon-derived fuels to 20 percent of all energy supply in 2050 (IEA 2021), from 80 percent in 2020.

The transition away from fossil fuels will follow different timelines in the developed world and developing regions where the demand for basic materials, electricity, and water, as well as the lack of infrastructure for net-zero options, might require the use of fossil carbon feedstocks to a larger extent and for longer times.

NOTE: EJ = exajoules.

SOURCE: IEA, 2021, Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, Paris: IEA, https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/deebef5d-0c34-4539-9d0c-10b13d840027/NetZeroby2050-ARoadmapfortheGlobalEnergySector_CORR.pdf. CC BY 4.0.

In contrast to falling fuel demand, demand for the many nonfuel, carbon-based products is expected to grow, tracking with expected global economic development. For example, the IEA projected that demand for petrochemicals would represent nearly a third of demand growth for oil in 2030 and about half in 2050 (IEA 2018). To better understand the current chemical industry, Appendix I, Table I-1 describes the major fossil-derived chemical products, excluding fuels, by global volume in 2007, and their production methods. Although the data are from 2007, it describes a baseline of fossil chemical production, which in the future will need to evolve into an industry producing a related but not identical suite of products, with sustainable carbon feedstocks, and likely at larger volume overall, with projected increases in demand for chemicals production. The key question becomes how to source the required carbon to manufacture these products. In principle, all hydrocarbon fuels and chemicals can be synthesized from CO2 and hydrogen. However, only some products and markets are likely to be attractive for investment in CO2 conversion processes, relative to other sustainable carbon feedstock alternatives. The costs of producing specific products via various CO2 utilization pathways versus competing pathways and feedstocks must be considered. Competing sustainable pathways include substituting the product with zero-carbon alternatives (most relevant for fuels), manufacturing the product with other nonfossil carbon feedstocks like biomass or recycled carbon wastes, or offsetting fossil carbon emissions from the product life cycle using negative emission technologies, such as capturing and geologically storing an equivalent amount of CO2.

Preparing for the transition to non-fossil-sourced chemicals production needs to factor in the risks to growth in product demand, as it will play a crucial role in research investments, and planning and deploying new supply chains and infrastructure to provide raw material streams. The total addressable market estimates the demand for carbon-based products that could be satisfied by production from sustainable carbon feedstocks, including CO2. Figure 2-3 illustrates examples of growth projections of the total addressable market for key product categories for which CO2 utilization could be considered (Sick 2022b), based on a market analysis of historical published growth rates and industry leader expectations. Based on that, product-specific and constant compound annual growth rates were assumed to project the market demand.

Market penetration during the transition to net zero will depend critically on the cost of the new products compared to the incumbents, especially fossil-derived products. All hydrocarbon products derived from CO2 require

SOURCE: Adapted from Sick (2022b), https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/5825. CC BY 4.0.

the input of energy and hydrogen, either in molecular form or as water or another hydrogen donor. Most products also require the formation of carbon-carbon (C-C) bonds, which may need additional, capital-intensive reaction and separation steps. Fossil feedstocks already contain carbon in chemically reduced form (“hydrocarbons”) and often also contain the desired C-C bonds. Given the large amounts of energy required and the capital intensity of the conversion processes, synthetic hydrocarbon products are therefore more expensive than those derived from petroleum or natural gas at their current prices. Any “green premium” can be an insurmountable barrier to (broad) market introduction. Procurement incentives, “buyers’ clubs” such as the First Movers Coalition, and direct subsidies via tax rebates and other policy means will be important to kickstart the emerging industry. For CO2 utilization to play a role in a future net-zero economy, the levelized cost of managing CO2 via conversion to products compared to sequestration will have to be reduced, and the true (societal) cost of using fossil carbon needs to be incorporated into the economy as well (Black et al. 2023). Chapter 4 discusses policy needs for CO2 utilization in greater depth.

2.2.3 Supply-Side Considerations for CO2-Derived Products

Using CO2 as a major feedstock for carbon-based products requires building up an entirely new industry, albeit one that can integrate substantial elements of current industries—for example, the construction material and chemical industries. The translation from invention to market-ready product gets increasingly expensive the closer the technology is to market introduction. Table 2-3 defines the technology readiness level (TRL) scale that describes the progress of a technology from research through development, and demonstration to operation. For technologies that achieve full commercial operation, times to market readiness usually are on the order of a decade, and any acceleration requires additional funding. The urgency to address climate change and secure access to sustainable carbon makes the long time-to-market a significant challenge.

TABLE 2-3 Definitions of Technology Readiness Levels

| Level of Technology Development | Technology Readiness Level | TRL Definition | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Operations | 9 | Actual system operated over the full range of expected conditions | The technology is in its final form and operated under the full range of operating conditions. |

| System Commissioning | 8 | Actual system completed and qualified through test and demonstration | The technology has been proven to work in its final form and under expected conditions. |

| 7 | Full-scale, similar (prototypical) system demonstrated in relevant environment | Demonstration is shown of an actual system prototype in a relevant environment. | |

| Technology Demonstration | 6 | Engineering/pilot-scale, similar (prototypical) system validation in relevant environment | Engineering-scale models or prototypes are tested in a relevant environment. This represents a major step up in a technology’s demonstrated readiness. |

| Technology Development | 5 | Laboratory scale, similar system validation in relevant environment | The basic technological components are integrated so that the system configuration is similar to (matches) the final application in almost all respects. |

| 4 | Component and/or system validation in laboratory environment | The basic technological components are integrated to establish that the pieces will work together. This is relatively “low fidelity” compared with the eventual system. | |

| Research to Prove Feasibility | 3 | Analytical and experimental critical function and/or characteristic proof of concept | Active research and development (R&D) is initiated. This includes analytical studies and laboratory-scale studies to physically validate the analytical predictions of separate elements of the technology. |

| 2 | Technology concept and/or application formulated | Practical applications can be invented. Applications are speculative, and there may be no proof or detailed analysis to support the assumptions. | |

| Basic Technology Research | 1 | Basic principles observed and reported | Scientific research begins to be translated into applied R&D. |

SOURCE: Adapted from DOE (2011).

CO2 utilization could be implemented in several industries to manufacture products for a variety of applications. Table 2-4 collects the assessment of priority products from CO2 utilization as examined in various studies, and their various applications in the economy. Some themes in priority products identified across studies include oxygenated chemicals like alcohols, aldehydes, and organic acids; chemical industry intermediates like CO, ethylene, and ethanol; chemicals with fuel applications like jet fuel, methanol, and gasoline; chemicals with organic carbonate groups, such as cyclic carbonates and polycarbonates and inorganic carbonates; and elemental carbon materials like carbon black and graphene. Most of these priority products follow the physicochemical trends identified in Section 2.2.1 that make them advantageous to synthesize from CO2. Most have industry-facing applications like chemical intermediates and manufacturing inputs, while some have consumer-facing applications like fuels. Manufacturers of chemicals, fuels, polymers, and inorganic carbonates will find opportunities for CO2 utilization.

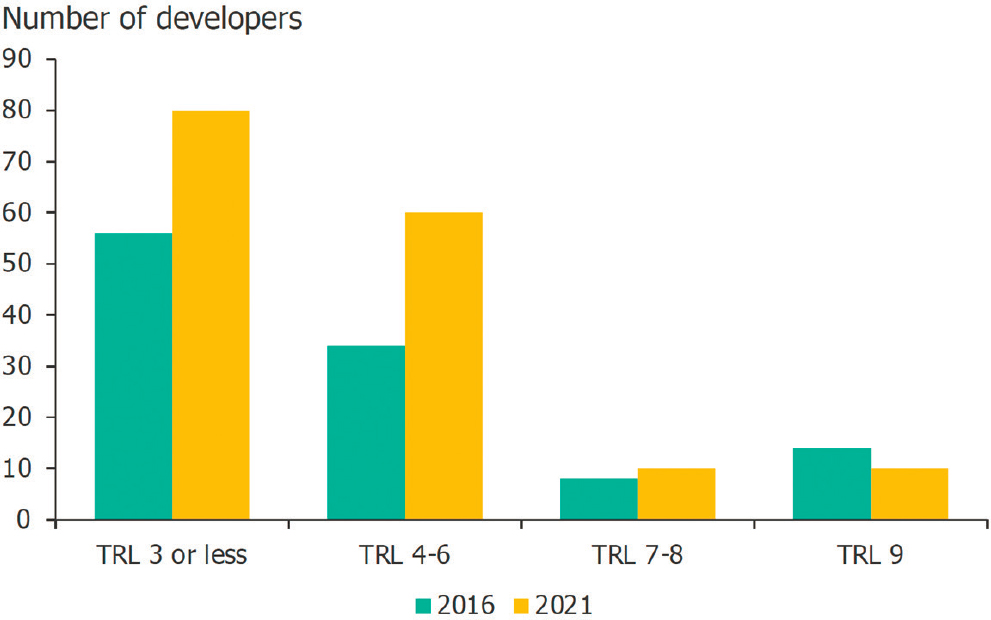

The nascent CO2 conversion industry is seeing increasing development, in response to expected demand for CO2-derived products, existing market opportunities, and incentives. As shown in Figure 2-4, based on data from a global industry and literature survey, the number of developers working on technologies for CO2 conversion to products has increased from 2016 to 2021, especially at lower TRL. Market-ready production capabilities were still very low. Another survey and analysis of self-reported data of developers in 2022 shows nearly a third of them operating at TRL 8 and 9 (Circular Carbon Network 2022).

Although the current petrochemical industry could be re-created with CO2 as a feedstock, net-zero emissions requirements will entail shifts in supply and demand factors likely to result in a different composition of the chemical industry (IEA 2020). For supply-side factors, today’s portfolio of chemicals in production and use

TABLE 2-4 Product Targets from CO2 Utilization as Described in Selected Studies of Technical Potential

| Chemicals and Materials | Product Application | Citations That Reference Priority Products |

|---|---|---|

| Acetic acid | Chemical intermediate Solvent |

Huang et al. 2021 |

| Alcohols | Solvent Detergent Fuel |

Bazzanella and Ausfelder 2017 |

| Aldehydes | Polymer Solvent Dye Cosmetics |

Bazzanella and Ausfelder 2017 |

| Carbon black | Filler for tires Pigment |

Sick et al. 2022b |

| Carbon fiber | Replacements for steel and aluminum | Biniek et al. 2020 |

| Carbon monoxide | Chemical intermediate |

Grim et al. 2023 Sick et al. 2022b Huang et al. 2021 Biniek et al. 2020 |

| Carbon nanotubes | Strengthener for concrete Optoelectronics Catalysis |

Sick et al. 2022b |

| Cyclic carbonates | Solvent Battery electrolyte Intermediate for polymer synthesis |

Bazzanella and Ausfelder 2017 |

| Diesel/jet fuel/hydrocarbon fuels | Fuel |

Sick et al. 2022b Huang et al. 2021 Biniek et al. 2020 IEA 2019 |

| Dimethyl ether | Fuel additive LPG substitute |

Huang et al. 2021 Bazzanella and Ausfelder 2017 |

| Ethanol | Chemical intermediate Fuels |

Grim et al. 2023 Huang et al. 2021 Biniek et al. 2020 IEA 2019 |

| Ethylene | Chemical intermediate |

Grim et al. 2023 Huang et al. 2021 Biniek et al. 2020 |

| Formic acid | Preservative Adhesive Precursor Fuel cell substrate |

Sick et al. 2022b Huang et al. 2021 Biniek et al. 2020 Bazzanella and Ausfelder 2017 |

| Gasoline | Fuel | IEA 2019 |

| Graphene | Electronics Batteries |

Sick et al. 2022b |

| Inorganic carbonates | Cement Aggregate Concrete Soil stabilization Mineral filler |

Sick et al. 2022b Biniek et al. 2020 IEA 2019 Bazzanella and Ausfelder 2017 |

| Methane | Fuel |

Sick et al. 2022b Huang et al. 2021 Biniek et al. 2020 IEA 2019 |

| Chemicals and Materials | Product Application | Citations That Reference Priority Products |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol | Acetic acid Ethylene, propylene Dimethyl ether Fuel Polymer precursor |

Grim et al. 2023 Sick et al. 2022b Huang et al. 2021 Biniek et al. 2020 IEA 2019 Bazzanella and Ausfelder 2017 |

| Organic acids | Surfactants Food industry Pharmaceutical industry |

Bazzanella and Ausfelder 2017 |

| Organic carbamates | Pesticide Polymer precursor Isocyanate precursor Agrochemicals Cosmetics Preservative |

Bazzanella and Ausfelder 2017 |

| Oxalic acid | Cleaning | Huang et al. 2021 |

| Polycarbonate etherols | Polyurethane foams | Bazzanella and Ausfelder 2017 |

| Polycarbonates | Polymer |

Sick et al. 2022b Biniek et al. 2020 IEA 2019 |

| Polyhydroxyalkanoate | Polymer |

Sick et al. 2022b Biniek et al. 2020 |

| Polyhydroxybutyrate | Polymer | Huang et al. 2021 |

| Polypropylene carbonate | Packing foils/sheets | Bazzanella and Ausfelder 2017 |

| Polyurethane | Polymer |

Sick et al. 2022b Biniek et al. 2020 IEA 2019 |

| Protein for animals | Animal feed |

Sick et al. 2022b OECD-FAO Agriculture 2021 |

| Protein for humans | Food | Sick et al. 2022b |

| Salicylic acid | Pharmaceuticals Cosmetics | Bazzanella and Ausfelder 2017 |

| Urea | Fertilizer Resin | Bazzanella and Ausfelder 2017 |

NOTES: Bazzanella and Ausfelder (2017) evaluated the technologies, pathways, and abatement opportunities and challenges for the European chemical industry to be carbon neutral by 2050, including economic constraints, investments, and research and innovation requirements. Sick et al. (2022b) evaluated the utilization amount and market size for building materials, carbon additives, polymers, chemicals, food, and fuels between 2022 and 2050 in the context of the total addressable market for respective products. Additionally, they examined these products’ development stages and developers in the market. Biniek et al. (2020) assessed current technologies and reviewed current developments for technology adoption and the economics of a range of use and storage scenarios. Grim et al. (2023) examined CO2 conversion via low-temperature electrolysis and reported products that could most impact global emission levels, especially those that could serve as intermediate feedstock inputs to known, commercialized upgrading pathways for producing high-volume chemicals. Huang et al. (2021) examined direct (low- and high-temperature electrolysis, microbial electrosynthesis) and indirect (biological conversion, thermochemical conversion) pathways for production of 11 chemicals from CO2, H2, and electrical energy. The priority chemicals were identified by their near-term technical viability. IEA (2019) considered the near-term market potential for five categories of CO2-derived services and products, including fuels, chemicals, building materials from minerals, building materials from waste, and CO2 use to enhance the yields of biological processes, to scale them up to a market size of at least 10 MtCO2/yr. OECD-FAO (2021) provided an assessment of the economic and social prospects and trends through 2030 for national, regional, and global agricultural commodity and fish markets with inputs from member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and commodity organizations, assuming no major changes in weather conditions or policies. The assessment highlighted that the implementation of climate smart production processes can mitigate the emissions impact of agriculture, especially in the livestock sector, discussed the prices, production, consumption and trade developments for biofuels, and the policies, regulations, and mandates for low-carbon agricultural practices, applications, and products in the member countries.

SOURCE: Sick et al. (2022b), https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/5825. CC BY 4.0.

stems from petroleum feedstock for carbon and focuses on oxidative conversions. Switching to carbon oxides as feedstock changes chemical pathways to reductive conversions, which changes the conversion processes and the intermediates and by-products involved. When using CO2 as a feedstock, more chemicals likely will be produced via CO or alcohols, for example, versus when starting with hydrocarbons, where ethylene or aromatics are more common precursors. Such restructuring can have a significant impact on research and development (R&D) needs, as discussed in Chapters 5–8. Attention needs to be paid to which chemicals are likely to transition first, which might no longer be needed, and for which alternative carbon sources or noncarbon alternatives might be an option. The same will be true for inorganic carbonates (aggregates), concrete, and elemental carbon products. Decision criteria will include the cost of production compared to incumbents, specific demand-pull, and supply-push, especially via policy instruments. Estimates for those criteria, regional variations, and demand projections are inherently uncertain. As such, it is not surprising to find variations between studies that evaluate priority products for CO2 utilization, as summarized in Table 2-4.

2.2.4 Markets for Materials from Coal Waste

Chapter 9 provides a deeper discussion of market opportunities for products made from coal waste, which offer the additional benefits of environmental and land remediation. Single- to double-digit growth rates of billion-dollar markets are projected for products from coal waste, including critical minerals and metals, pigments, direct use in construction materials, and coal waste–derived carbon materials (Fortune Business Insights 2023a, 2023b; Grand View Research 2022; SkyQuest Technology 2024; Stoffa 2023; Straits Research 2022).

Leveraging coal waste presents distinct challenges, primarily related to its fossil origin and the resulting potential for net-positive emissions, regional availability, and eventual diminishing supply. Any coal-derived product needs to be durable to avoid the introduction of new, fossil carbon into the atmosphere. The largest market

value for durable products for beneficial coal waste reutilization include construction materials, energy storage materials/electronics, cement, and concrete (see Table 9-2). Coal ash is already a common additive in many concrete products. Globally, 70 to 90 million tons of coal impoundment waste are generated annually (Gassenheimer and Shaynak 2023), and several billion tons are stored in nearly 600 slurry impoundments across the United States (Environmental Integrity Project 2019). Although coal waste is localized and volume limited, existing transportation infrastructure for coal could be repurposed and leveraged to mitigate logistical hurdles. The value-added potential of coal waste utilization extends beyond carbon conversion or critical minerals extraction and encompasses environmental cleanup efforts, and local job creation or preservation in coal communities. Incentives driven by the growing demand for critical minerals could catalyze efforts to repurpose coal and simultaneously address local pollution concerns associated with coal waste piles, including fly ash cleanup (Granite et al. 2023).

2.2.5 Product-Specific Market Considerations

As outlined in Table 2-1, this section explores some of the main product classes targeted for CO2 utilization (inorganic construction materials, fuels, polymers, chemicals and chemical intermediates, elemental carbon, and food and animal feed) and the specific market considerations for the future viability of each product class. Each section describes the incumbent production and use of the product class, why a transition in production is needed for a net-zero future, the implications of different sustainable carbon feedstocks, and the key market considerations for the product class.

2.2.5.1 Inorganic Carbonate Construction Materials

The inorganic carbonate construction materials product class includes cement, concrete, and aggregates used for constructing buildings and infrastructure—for example, roads, water systems, and so on. These materials are produced at a large scale and with low profit margins from raw materials such as ores, rocks, and wastes by mining, crushing, grinding, processing, and/or heating at high temperatures. Incumbent manufacturing processes do not employ CO2 as a feedstock in concrete production and, in fact, emit large quantities of CO2 through energy use and process emissions associated with the chemical transformations of the materials for cement production. Production and use of construction materials are distributed geographically, with limited long-distance transportation owing to their weight and volume. A net-zero future could result in reduced CO2 emissions, consumption of waste materials including CO2, and improved material properties (such as improved compressive strength).

Net-zero compatible alternatives to the production of inorganic construction materials include recycled materials, biogenic materials, and technologies that bypass the process-related CO2 emissions inherent to cement production from carbonate minerals. Recycling is common in the construction industry, particularly in road infrastructure. Recycled materials can include inorganic materials, recycled plastic, and other wastes as fillers or formed into construction components. Biogenic materials include timber, laminated beams, and particle boards used in structural or other roles in buildings. Recycled or biogenic construction materials as replacements for inorganic building materials could have the advantages of reducing waste streams and resource depletion. However, based on competing needs in other parts of the economy and suitability for structural applications, the use of biogenic materials may be limited. Lower-emissions technologies are in development to produce cement and concrete. These novel approaches bypass the process-related emissions from the conversion of carbonate rocks to reactive calcium clinker, instead converting noncarbonate minerals to reactive calcium species. These technologies also often have reduced need for high-temperature reaction conditions, and thus can be electrified, providing further opportunities to reduce CO2 emissions on a life cycle basis.

CO2 utilization to produce inorganic construction materials includes direct reaction of dissolved CO2 with minerals to form aggregates or powders; carbonation of alkaline industrial and demolition wastes to form components of concrete; exposing construction materials to CO2 to enhance carbonation, including to cure concrete; and formation of alternative cementitious materials. (R&D status and needs for CO2 utilization to produce inorganic carbonates are detailed in Chapter 5.) These processes are relatively well developed compared to other CO2 utilization processes, could be rapidly deployed, and in some cases, result in cost advantages (Carey 2018;

SOURCE: Based on figures and material from Sick et al. (2022b), https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/5825. CC BY 4.0.

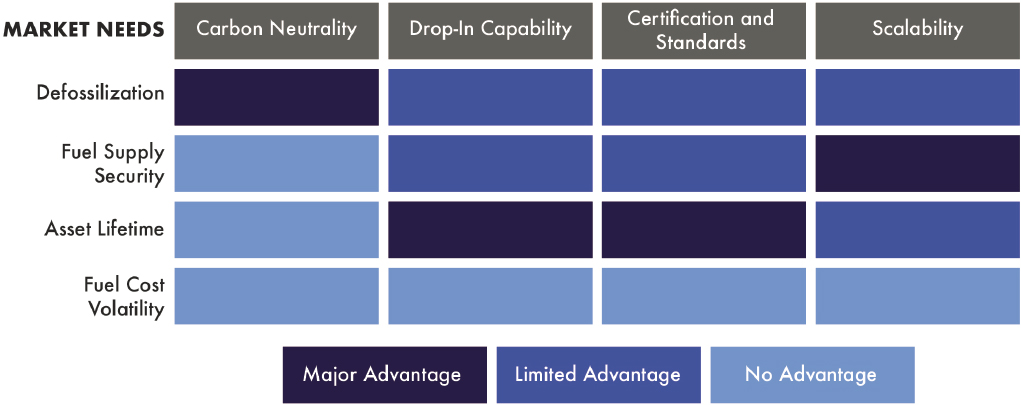

NASEM 2019; St. John 2024). The transformation produces solid carbonates, a stable, solid form of carbon that provides durable storage. Figure 2-5 maps the product-market fit via key market needs for the introduction of these new aggregates (listed as row headers: defossilization, residual material use, mechanical performance, and low cost), as well as features of CO2-derived aggregates that may meet those market needs (listed as column headers: long-term CO2 storage, drop-in capability, feedstock flexibility, and scalability), producing a heat map of areas with high potential for market pull. The market introduction of CO2-based aggregates will be advantageous if the capabilities can successfully address the needs. As illustrated in the figure, CO2-derived aggregates are advantaged in long-term CO2 storage capability and feedstock flexibility to meet the market needs of defossilization and use of residual materials from construction and other industry sectors—for example, steel and coal wastes. Ensuring the required mechanical stability of new types of aggregate materials is a given expectation, and improved performance does not appear to create a market advantage. Equally, in a low-margin commodity market, low cost is expected.

Advantages of CO2 utilization over incumbent concrete materials include improved properties, reduced material use, flexible feedstocks, reduced environmental impacts for a circular economy, and lower costs. For example, in precast concrete production, CO2 curing accelerates the curing process, increases strength, reduces material needs, and can be cost-efficient. Also, technologies that mineralize CO2 to limestone powders or carbonate fly ash can support novel three-dimensional (3D) concrete printing, which has the potential to provide environmental benefits, including less concrete waste and lower water use, faster construction, and lower costs (Yu et al. 2021; Zhu et al. 2021). The product–market fit for CO2-cured concrete is summarized in Figure 2-6, showing a heat map of areas of high potential for market pull. Market inhibitors, such as local building codes and the cost and time required for testing and documentation can limit or prohibit the use of new materials, especially for small-scale producers, but are not fundamental inhibitors based on technical performance.

Key market questions for future viability of CO2-derived inorganic carbonate building materials: Can new production technologies and reprocessing of waste materials overcome market inhibitors such as low profit margins, limited long-distance transportation of heavy, low-value commodities, and regulatory hurdles such as composition-based building codes? How can CO2 availability accommodate the distributed nature of the construction industry?

SOURCE: Based on figures and material from Sick et al. (2022b), https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/5825. CC BY 4.0.

2.2.5.2 Fuels

The global economy relies heavily on fossil fuels, with more than 80 percent of total energy from coal, oil, and natural gas (IEA 2019). Their combustion releases CO2 and uses the energy in the fuel for electricity generation, vehicle propulsion, heating of buildings and industrial processes, and other energy needs. Fossil fuel production and combustion pollute the local and global environment, are harmful to human health, and are a major cause of climate change.

To eliminate the harms from fossil fuel production and use, most uses of fossil fuels must be replaced by zero-carbon alternatives in a net-zero future. Potential zero-carbon replacements for fossil fuel–powered systems include electric power generated from zero-carbon energy sources, hydrogen-powered systems including fuel cells, and energy efficiency measures to reduce the need for heat and power. Transitioning to zero-carbon electric power is more efficient than combustion, is less polluting, and leverages the existing power grid infrastructure. Drawbacks to electric power—for example, poor energy density and long recharging times for batteries—may make electricity unsuitable for some fuel substitution applications, especially in long-haul air and ocean transportation. Hydrogen fuel cell power is less efficient than using electric power directly, although it can have higher energy density. A major obstacle to hydrogen power is the requirement of new vehicle propulsion systems and hydrogen production, storage, and delivery infrastructure. For shipping, sustainably produced ammonia is being explored as an alternative zero-carbon fuel. However, the major concerns are safety, health issues, and the risk of highly elevated NOx emissions from ammonia combustion (Bertagni et al. 2023).

Carbon-based alternatives to fossil fuel incumbents include biofuels such as ethanol, biodiesel, and jet fuel derived from bio-based sources. Bioethanol is already a major part of the transportation fuel system and can often be used in existing combustion, storage, and delivery systems with relatively minor modifications. Biofuels require significant land and water for crop production and result in pollution impacts from industrial agriculture, groundwater depletion, and fuel combustion. More details on the national prospects for the use of biomass resources can be found in the recently released DOE 2023 Billion-Ton Report (DOE-BETO 2023).

Synthetic CO2-derived liquid fuels can be produced by chemical and biological CO2 utilization. (R&D status and needs for chemical and biological CO2 utilization to fuels are detailed in Chapters 7 and 8, respectively.)

CO2-derived fuels have similar advantages to biofuels, being energy-dense and in many cases, usable in the existing fuel combustion, storage, and delivery systems. CO2-derived liquid fuel targets include methanol, ethanol, and jet fuel. They also have similar drawbacks to biofuels, including being less efficient and more expensive to produce than electricity or hydrogen, and leading to air pollution when combusted, although they are likely to have fewer land-use impacts than biofuels (Gabrielli et al. 2023). Synthetic aviation fuel will likely be the primary target for liquid fuel use, because of a lack of feasible technological alternatives, a greater need for energy density, the ability to absorb higher prices, and less concern about proximity to air pollution from combustion, with marine fuel (methanol) as an additional potentially important market. Aviation fuel may command a greater premium than marine fuel, depending on consumer willingness to pay (World Economic Forum 2023). The product–market fit for CO2-derived fuels is summarized in Figure 2-7, showing a heat map of areas of high potential for market pull. A key advantage of synthetic aviation fuel is that it can be produced to meet the properties of current fossil-based fuels and used as a direct drop-in replacement, preserving all assets in the value chain, including aircraft. Distributed, co-located CO2 capture and conversion plants could support scaling and increase supply stability, including for military needs (DoD 2023; U.S. Naval Research Laboratory 2012). Another competitor is offsetting fossil fuel combustion emissions with negative emissions technologies, which may have lower costs than replacing fossil fuel with bio-derived or synthetic CO2-derived aviation fuel. However, CO2-derived synthetic fuels offer more direct climate benefits than the purchase of negative emissions offsets and may be favored by future markets or regulatory structures.

Key market questions for future viability of CO2-derived fuels: Where and when can synthetic fuels compete with direct electrification and other alternative fuels? How will utilization for short-lived products compete with sequestration for CO2 sources? How will rereleased CO2 be accounted for in market and regulatory monitoring, reporting, and verification schemes? What is the capacity to provide synthetic fuels in the context of competing demands for zero-carbon electricity and hydrogen?

SOURCE: Based on figures and material from Sick et al. (2022b), https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/5825. CC BY 4.0.

2.2.5.3 Polymers

Polymers are currently predominantly synthesized from chemical intermediates derived from fossil carbon, with a smaller but significant market share derived from biomaterials or recycled polymer materials. Current methods of production and use result in CO2 emissions, significant solid-waste streams, and local pollution.

Currently, the most important alternatives to fossil-derived polymers are biopolymers and polymers derived from recycled materials. In 2019, the polymer and plastics industry caused 3.4 percent of the global carbon emissions (OECD 2022). Furthermore, petrochemical plastics are notoriously recalcitrant to environmental degradation, causing substantial environmental hazards, including microplastics that impact human and wildlife health. Bioplastics, which encompass polymers made from biomass and polymers that biodegrade, represent a significant opportunity to reduce carbon emissions and other environmental hazards. Biopolymers like polyhydroxyalkanoate and polylactic acid provide local environmental benefits, as they are biodegradable or compostable and avoid lingering microplastics. Bio-based polymers produced from starch or sucrose derived from feedstocks like corn and sugarcane may confer an advantage over petrochemical plastics in reducing carbon emissions, although cultivation of corn and sugarcane comes with direct and indirect land use implications. Composting or recycling, described below, requires a value chain that includes infrastructure for separating and appropriate time and conditions for degradation.

Some polymers can be recycled either by mechanical or chemical recycling. Pure mechanical recycling via grinding or melting plastic products down to their base polymer requires high-quality, contaminant-free feedstock with uniform molecular composition. Mechanical recycling produces polymers with the same composition as its feedstock (Maureen 2023). Chemical or molecular recycling utilizes additional chemical inputs (solvents, enzymes) to break down recyclate into its constituent components (monomers, oligomers) to produce the same or different polymers (Luu 2023). Although often used synonymously with molecular recycling, chemical recycling sometimes refers to waste-to-energy processes, in which case CO2 emissions are not minimized (Bell 2021). The viability of chemical or molecular recycling is limited by the complexity of plastic recyclate. Common additives like plasticizers and colors complicate the chemical recycling process owing to uncertainty or complexity of composition overwhelming existing molecular separation methods. Existing mechanical and chemical recycling methods can be energy-, water-, and land-intensive (Uekert et al. 2023). CO2 emissions benefits of recycled versus virgin plastic manufacturing are circumstantial based on the composition, complexity, and quality of available feedstock.

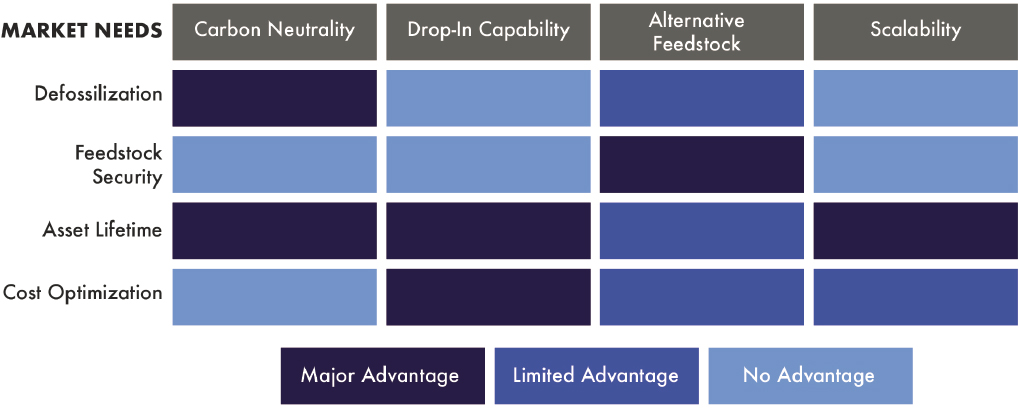

CO2 utilization to form polymers can proceed via the same intermediates as fossil fuel–derived polymers, but using CO2-derived feedstocks, or via novel processes to incorporate CO2 as a feedstock directly or via different intermediates. (R&D status and needs for chemical and biological CO2 utilization to polymers are described in detail in Chapters 7 and 8, respectively.) Chemical intermediates such as ethylene, propylene, and aromatics used in current polymer production, to polyethylene, or polypropylene or polystyrene, can be generated from CO2 via synthesis gas (Gao et al. 2017, 2020; Saeidi et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2019). Direct utilization of CO2 offers routes to other classes of polymers, such as polyurethanes made from CO2-based polyols, polycarbonates, and polyhydroxyalkanoates (Afreen et al. 2021). These types of polymers or their building blocks could become key entry points for CO2 use, with polyols already containing 20–40 percent CO2 by weight. Limitations in thermal stability and mechanical properties of polycarbonates, polyols, and polyhydroxyalkanoates have restricted their widespread use (Ali et al. 2018; Capêto et al. 2024; Grignard et al. 2019; Styring et al. 2014). On the other hand, progress is being made to improve properties—for example, new synthesis methods have demonstrated polymers built from CO2 that have flame-retardant properties (Ma et al. 2016). The product–market fit for CO2-derived polymers is summarized in Figure 2-8, showing a heat map of areas of high potential for market pull. The market introduction of polymers made with CO2 is facilitated not only by helping to defossilize the polymer industry but in particular by offering continued use of production facilities, improved recyclability, and the opportunity to provide entirely new performance characteristics.

Key market questions for future viability of CO2-derived polymers: Can production costs be reduced, such as by co-location with CO2 emitters? Can suitable CO2-based polymers be made with favorable performance/cost balances? What is the competition for CO2-derived versus bio-derived polymers and can biomass sourcing meet biopolymer demand? Can new, reductive synthesis methods that start with CO2 be strategically used to design polymers with unique new purposes—for example, purpose-designed lifetimes?

SOURCE: Based on figures and material from Sick et al. (2022b), https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/5825. CC BY 4.0.

2.2.5.4 Chemicals and Chemical Intermediates

Current production of chemicals and chemical intermediates is almost entirely from fossil feedstocks of oil and gas and represents a small portion of fossil hydrocarbon use. The demand for chemical products is growing faster than the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) and fuel demand. In a net-zero future, when fuel demand is likely to decrease dramatically, chemical demand will become a much more significant player in carbon-based product needs.

Alternatives to chemicals and intermediate production are primarily biobased materials. The efficiency and competitiveness of CO2-derived chemicals compared to biomass-derived ones depend on factors like feedstock cost, energy requirements, and land/water use. Biomass is often more competitive for products requiring carbon-carbon bonds, which are often already present in bio-derived carbon feedstocks. Both CO2- and biomass-derived materials are better suited to making oxygenated compounds, relative to fossil fuels. Biomass is used more easily for reduced compounds as compared to CO2. Bio-derived compounds face higher water and land use implications than CO2-derived materials (Gabrielli et al. 2023).

Carbon utilization is attractive for commodity chemical production to leverage existing infrastructure. Repurposing established facilities and processes offers a potentially cost-effective means to convert CO2 to valuable products while simultaneously reducing GHG emissions. Chemical product targets include carbon monoxide, alcohols, light olefins, and carboxylic acids, both as final products and intermediates. The production of sustainable aviation fuels from CO2 will result in many by-products that can enter the supply and production chains for chemicals in the same way that many chemicals we use today are by-products from reforming petroleum into gasoline, diesel, and kerosene fuels. Therefore, we may see some currently used chemicals and chemical intermediates disappear from markets while others enter.

Opportunities for broader market introduction will be higher the more downstream applications a product will have. This makes the drop-in replacement of entry-level chemicals and intermediates for a wider range of final products attractive. A key example is methanol, with high market needs as a base chemical and a potential new marine fuel. The product–market fit for CO2-derived methanol is summarized in Figure 2-9, showing a heat map of areas of high potential for market pull. CO2-derived methanol is a cost-effective drop-in replacement for its

SOURCE: Based on figures and material from Sick et al. (2022b), https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/5825. CC BY 4.0.

chemically identical incumbent. The preservation of existing infrastructure in the chemical industry will be a key factor for adoption as geographically flexible feedstock availability and supply stability are increased.

Key market questions for future viability of CO2-derived chemicals and chemical intermediates: Can CO2-derived chemicals overcome the efficiency and competitiveness challenges presented by biomass-derived chemicals? Will future markets demand a price premium for a more sustainable product? Which opportunities exist for new products not yet available in this class? Will a new and different by-product stream from synthetic fuel production alter the chemical industry’s well-established and global integrated supply chains and product mix?

2.2.5.5 Elemental Carbon Materials

Elemental carbon materials offer opportunities for long-term carbon storage, can potentially replace products made via high-carbon-emitting processes like steel production in some applications, and be used in high-value applications like electronics. Today, elemental carbon materials are primarily produced through combustion or pyrolysis of organic compounds (fossil sources) and synthesis through chemical vapor deposition techniques. Starting with biomass as a carbon source followed by subsequent combustion or pyrolysis could provide more sustainable pathways to elemental carbon products. These processes yield a range of materials, such as carbon black, graphite, graphene, and other carbon nanostructures, each with different properties and applications. Additionally, some of these materials can be produced through processes like electrochemical reduction or catalytic conversion, making them feasible CO2 utilization targets. Particularly, graphene has many potential applications in energy, electronics, construction, and health care owing to its flexibility, lightness, and attractive mechanical and electronic properties.

Some elemental carbon products are likely to be used at lower volume, but in high-value applications, like electronics. Others could be deployed in very high-volume applications, with lower value, such as in construction materials. Small-volume, high-value markets may enable CO2 utilization if buyers put a premium on CO2-derived materials. Larger-volume, lower-value applications in the building industry present a significant market for material amendment or replacement. However, substituting carbon fibers and composites for steel and aluminum requires a significant industry shift and is more expensive, particularly for concrete. The product–market fit for elemental

SOURCE: Based on figures and material from Sick et al. (2022b), https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/5825. CC BY 4.0.

carbon materials is summarized in Figure 2-10, showing a heat map of areas of high potential for market pull. Key needs to address for successful market introduction are defossilization of target industries and providing suitable products to replace incumbents that suffer from a high carbon footprint—for example, aluminum and steel. While the production of carbon fibers, nanotubes, and graphene from CO2 is still in its early stages, their value and potential to replace carbon-emission-intensive metals can lead to substantial growth. Conversion of CO2 to carbon black could be pursued as a drop-in substitute for current production, but competition with incumbent producers will likely delay market penetration.

Key market questions for the future viability of CO2-derived elemental carbon: Can new products overcome cost barriers and industry conservatism to replace carbon-emission-intensive metals like steel and aluminum in large-volume applications, particularly in the construction and automotive industry? What incentives may be needed? Can elemental carbon materials be recycled at the end of their use phase, which might be less than 100 years?

2.2.5.6 Food and Animal Feed

Current food and animal feed production is of biological origin, using plants and animals, and has sustainability challenges. While it is estimated that about 30 percent of produced food is wasted (NASEM 2023a), many lack access to enough food. The rising impacts of climate change also pose substantial risks to the food system through desertification and reduced land availability. Overfishing contributes to the loss of biodiversity and food resources from the oceans. Agricultural runoff pollutes waters and soils, leading to further ecosystem degradation. Animal agriculture (particularly the production of red meat) is especially resource-intensive and requires sustainability solutions in light of the growing global demand for animal protein. Alternatives need to be considered to ensure adequate nutrition for the world’s human population and reduce the environmental burdens of food production.

The main alternatives to carbon dioxide utilization for food and animal feed are climate-smart agricultural methods. In addition to emissions reduction, these methods enhance agricultural resilience to climate-related risks, increase agricultural productivity, and improve financial returns for farmers (Kazimierczuk et al. 2023). Regenerative, digital, and controlled environment agriculture methods are among the most promising alternatives (Kazimierczuk et al. 2023). Regenerative methods focus on carbon sequestration through improved soil health

and fertility, increasing water retention and percolation, reducing runoff, and strengthening system biodiversity and resilience (Elevitch et al. 2018). Digital methods integrate real-time or near-real-time feedback between sensors and equipment to make automated adjustments for emissions reduction and yield optimization. Controlled environment methods use indoor farming configurations like vertical farms, greenhouses, container farms, and integrated aquaponic systems to closely regulate the agricultural environment and reduce land and water usage (Goodman and Minner 2019).

CO2 utilization can be leveraged in two ways in food production. First, increasing microbe-based production of drugs, food supplements, fuels, and chemicals leaves spent microbes as a waste material, which have high protein content and could be used directly as animal feed (LanzaTech 2023). This is analogous to other energy systems that use spent material as animal feed, such as ethanol production’s coproduct of dry distillers grains, producing 38 million metric tons of feed for agricultural animals annually in 2018/19 (Olson and Capehart 2019). Department of Energy (DOE)-supported efforts on the algae-based conversion of CO2 were recently summarized at the 2023 DOE’s Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management/National Energy Technology Laboratory Carbon Management Research Project Review Meeting (NETL 2023).

Second, compounds derived from CO2 conversion can be directly used for protein production via tissue engineering (e.g., cultivated meat or animal muscle cell cultures grown in reactors). Several such targeted commercialization activities are under way (Corbyn 2021; Mishra et al. 2020; Pander et al. 2020; Sillman et al. 2019). While market-ready production scales and acceptance are not expected until 2050 and beyond, consumer attitudes have been identified as a key issue in the market success of food replacements, especially alternative proteins (Van Loo et al. 2020). Competition for carbon-free electricity and hydrogen from other parts of the economy will be challenging for an emerging food production industry and is a key barrier for the industry. Additionally, regulatory barriers could challenge market entry.9 The product–market fit for food and feeds is summarized in Figure 2-11, showing a heat map of areas of high potential for market pull.

Key market questions for the future viability of CO2-derived food and animal feed: How can new products achieve Food and Drug Administration approval for human consumption? Will customers adopt “synthetic food”? What incentives may be needed? What are the techno-economic assessment (TEA) and life cycle assessment (LCA) considerations for cultivated protein products?

2.3 INFLUENCES ON CO2 UTILIZATION MARKET DEVELOPMENTS

Potential revenue streams for CO2-based products are trillions of dollars per year (Mason et al. 2023; NASEM 2023b), which could be an attractive driver to build up production capacity, depending on the unit economics per market. However, the successful market introduction of products made from new carbon feedstocks depends on a variety of factors, including feedstock availability and access, suitable conversion technologies and infrastructure, industrial participants in the value chain, consumer demand and acceptance, and regulatory environments. Furthermore, commercial success will depend on cost, cost-reduction strategies, financial risk management, and the ability to consistently meet demand, especially in commodity markets. TEA and LCA, including societal aspects, will be essential to understand environmental and equity risks and opportunities, and avoid unintended consequences. (See Chapter 3 for further details on LCA and TEA.)

Several studies project sizable opportunities for both climate benefits and economic potential for CO2 as a carbon feedstock, especially conversion to long-lived products. Projections show that this could be possible at several Gt/year within decades (Biniek et al. 2020; Hepburn et al. 2019; IEA 2019; Jacobson and Lucas 2018; Sick 2018; Sick et al. 2022b).

Product adoption depends strongly on how fast market penetration proceeds, with timelines that stretch over decades. Figure 2-12 projects time needed to reach 10 percent market penetration and the time required to achieve a CO2 utilization rate of 0.1 Gt per year for selected products. Given the urgent need to replace fossil carbon with

___________________

9 As an example of regulatory inconsistency, the commercial sale of single-cell grown chicken meat for human consumption was recently allowed by regulators in the United States (Toeniskoetter 2022). In contrast, around the same time, the Italian government imposed a €60,000 fine for producing, selling, or importing laboratory-grown meats (Kirby 2023).

SOURCE: Based on figures and material from Sick et al. (2022b), https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/5825. CC BY 4.0.

sustainable alternatives and produce durable stores of carbon, these low market uptake rates point to the need for rapid action to accelerate deployment. Comprehensive planning and evaluation are needed to ensure environmental benefits while also including economic and societal considerations (Newman et al. 2023).

Sections 2.3.1–2.3.8 detail important determinants of CO2 market developments—namely cost, availability and access to feedstocks, technology and infrastructure, supply chains, consumer demand and acceptance, the regulatory environment, financial risks, and environmental and equity impacts. Establishing a CO2 utilization industry would

SOURCE: Adapted from Sick et al. (2022b), https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/5825. CC BY 4.0.

benefit from a publicly available tracker that shows activity and progress with deployments, and the amounts of CO2-based products that enter markets. This will also support tracking how much CO2-based products contribute to reducing the carbon emissions burden.

2.3.1 Cost Factors for CO2 Utilization Markets

The future use of CO2 will be influenced by several cost factors that will determine the feasibility and scalability of carbon capture, utilization, and storage. One prevalent challenge is that, in many cases, the cost of producing CO2-derived products exceeds that of incumbent alternatives. This cost disparity is driven by several factors, including the high upfront capital cost of CO2 capture and transport, the energy expenditures required for possible purification and conversion processes, and the need to optimize and improve those processes (GAO 2022).

CO2 utilization will be a highly capital-intensive endeavor to build the necessary production facilities or to retrofit some existing factories. The global cumulative investment in production facilities will be substantial for raw materials, labor, and construction (Sick et al. 2022a). CO2 conversion facilities to form chemicals and fuels are especially capital-intensive, whereas facilities to produce aggregates and precast concrete, while more numerous, are less expensive to build to scale (Figure 2-13). For example, by 2050, meeting global aviation fuel demand with CO2 utilization is estimated to require about 21,000 production facilities with annual capacities of 100 million liters of jet fuel each and estimated to cost $4.8 trillion (Sick et al. 2022b). Furthermore, for many CO2-derived products, the dominant factor remains the cost of energy, typically electricity, which underscores the importance of energy efficiency and inexpensive, clean power generation in shaping the future of CO2 utilization (Huang et al. 2021).

Capital and operating costs associated with CO2 capture and transport are also important, especially as the industry evolves. The development of high-volume demand and compliance markets for some products will influence the trajectory of CO2 capture costs for the market as a whole. For example, the aviation industry’s quest for reduced carbon-intensity fuels could be a significant driver for increased capture volumes. Early opportunities for CO2 capture may arise from existing processes like ethanol production, which have high-purity, proven technology,

SOURCE: Based on data from Sick et al. (2022b), https://dx.doi.org/10.7302/5825. CC BY 4.0.

scale, and relatively low costs. The pace of capture process optimization, however, can become a critical cost driver. Local availability of sufficient sources of CO2 at competitive cost will increase competitiveness of technologies by avoiding the need for expensive and potentially controversial transportation infrastructure.

2.3.2 CO2 Supply Chains

The market for incumbent uses of CO2 in the food and beverage industry and as a process gas globally reached approximately 236 million tonnes in 2022 and is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 6.5 percent until 2035 to reach approximately 520 million tonnes (Chemanalyst 2023a). The addition of and shift toward CO2 conversion to products could increase this market to Gt/year (IEA 2020; Sick et al. 2022b). Current CO2 sources include ethanol, ammonia, and natural gas processing facilities, and future sources may include other industrial point sources and facilities drawing from ambient sources such as direct air capture (DAC) and direct ocean capture (DOC). The existing supply chain for the CO2 industry lays a foundation for future CO2 utilization-to-products in a net-zero market but needs to evolve to meet the challenges of tackling climate change. The CO2 supply chain involves numerous aspects and actors, including carbon capture and separation from point or ambient sources, followed by purification, processing, and transportation to downstream applications and markets (DOE-EERE 2022). The success of CO2 utilization-to-products depends on identifying best practices from existing supply chains and optimizing them to create long-term sustainability benefits.

Reliable availability and price stability of a feedstock are essential to build up downstream uptake. If competing demands for a feedstock exist, they may jeopardize companies, especially during the early scale-up phase when their needs are not at final capacity and when they are not yet established as a stable customer. The majority of CO2 supply chains today have been developed for industrial applications that involve direct use of CO2 without chemical conversion. This includes the food and beverage industry, which had the largest revenue share of the merchant CO2 market in 2022, and enhanced oil recovery for depleted oil reserves. New applications for direct use of CO2 are gaining prominence, such as the use of CO2 in the medical sector as an inhalation gas in various surgeries (Grand View Research 2023) and CO2-assisted enhanced metals recovery from spent lithium-ion batteries (Bertuol et al. 2016).

Chemical and biological conversions of CO2 are not as prevalent in industry today, except in the manufacturing of urea for the fertilizer industry. However, as discussed throughout this chapter and projected in several market studies (Grand View Research 2023; Sick 2020), CO2 as a carbon feedstock for products will quickly grow in relevance, albeit at different rates across the industry landscape. For a comprehensive view of these products, refer to Table 2-1. Incumbent direct-use applications of CO2 will compete with emerging products for supply.

The industrial gas and the oil and gas industries historically have led investments in CO2 supply chain development for merchant and enhanced oil recovery applications, respectively. The Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, representing 12 of the world’s largest energy companies, is developing projects in regional, interconnected carbon capture, utilization, and storage supply chains at scale for industrial decarbonization (Oil and Gas Climate Initiative 2023). Alongside established companies, start-up companies will play a significant role in the carbon capture and utilization value chain, especially as new business models develop around “partial-chain” or specific components of supply (IEA 2023). In 2016, fewer than 200 entities were active in CO2 utilization (Sick 2018). By 2022, that number increased to 274 (Circular Carbon Network 2022), indicating some growth but still at the very bottom of a typical S-curve for economic development.