Carbon Utilization Infrastructure, Markets, and Research and Development: A Final Report (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

1.1 STUDY CONTEXT

To meet climate goals and limit the harmful effects of global warming, countries around the world are aiming to reach net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions across their economies by midcentury. Along this path toward net-zero emissions by 2050, the United States has set an intermediate goal of a 50–52 percent reduction in GHG emissions below 2005 levels by 2030 (DOS and EOP 2021), which aligns with the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Achieving net zero requires eliminating most emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other GHGs,1 primarily via decarbonizing electricity generation, improving energy efficiency, and electrifying end uses (e.g., vehicles, buildings, industrial processes) where possible (DOS and EOP 2021; NASEM 2021). These actions, enabled by advances in low-carbon energy technologies and electrification, will significantly reduce the use of fossil fuels and resulting CO2 emissions to the atmosphere. This report responds to a request from Congress to examine the role of carbon utilization in a net-zero emissions future.

While net GHG emissions to the atmosphere must end to achieve climate targets, carbon flows—particularly those related to embedded carbon in products—cannot be eliminated completely. As discussed in Chapter 2, global yearly materials flows are about 100 gigatonnes (Gt), including about 40 Gt of carbon-based materials, with about 15 Gt of that being fossil-derived carbon materials. Carbon-based products, including human-made chemicals, fuels, and materials, are central to global and national economies today, and many will remain important in a net-zero future. Historically, carbon-based products have been made from petroleum, natural gas, coal. The modern chemical industry was built to transform carbon-based molecules distilled from petroleum into a variety of products using inexpensive fossil fuel–derived heat. Most of these products are short-lived, and at end of life, become CO2 via combustion or decay processes. When the carbon was fossil in origin, as is true for the vast majority of fuels, chemicals, and polymers produced today, then material end of life results in fossil CO2 emissions to the atmosphere. To achieve net zero, these linear carbon flows from fossil feedstock to CO2 in the atmosphere will need to shift to circular flows such that no new carbon enters the system, and instead any carbon emitted is

___________________

1 The warming effects of CO2 and other GHGs differ depending on their atmospheric lifetime and ability to absorb energy. These effects can be quantified and compared using Global Warming Potential (GWP), a measure of how much energy 1 ton of a GHG absorbs over a given amount of time (often 100 years) compared to the energy absorbed by 1 ton of CO2 over the same amount of time (EPA 2024a).

captured and reused or stored. In a circular system, petroleum feedstocks will be largely unavailable2 owing to their contribution to GHG emissions, and instead feedstocks will include biological material, recycled wastes, and CO2. Using biological, recycled, or CO2 feedstocks enable circularity by allowing carbon wastes, such as CO2 from product degradation, to be incorporated into new products. The choice of sustainable carbon sources depends on many factors, including product composition and lifetime, feedstock cost, access to infrastructure, and regulatory and policy environment. To accommodate new feedstocks, the landscape of chemical and material products and processes is likely to change. Some carbon-based chemicals and materials will decline in use as zero-carbon alternatives become prominent (e.g., fuels replaced by electrification). Other carbon-based chemicals and materials are likely to increase in use because their relative value will increase (e.g., methanol or carbon monoxide as a more important intermediate for chemical synthesis, or carbon fibers as a replacement for higher-emitting materials in construction and manufacturing).

In addition to eliminating most sources of GHG emissions, long-term removal of CO2 from the atmosphere will likely be needed to reach safe levels of GHGs for a stable climate. This removal could occur by geologic sequestration of CO2 captured from the air or bodies of water or by incorporating captured CO2 into long-lived products, especially those deployed at large (gigatonne) scales worldwide, such as concrete and aggregates. Such long-lived products additionally could contribute to emissions reductions by displacing heavily emitting processes like those used for producing conventional building materials.

The net-zero transition will require substantial amounts of critical minerals and materials to deploy clean energy technologies at scale. For example, lithium, cobalt, nickel, and graphite are used in batteries for electric vehicles and energy storage; silicon, copper, and silver are used in conventional photovoltaics; and copper, zinc, and rare earth elements (primarily neodymium) are used in wind turbines (IEA 2022). Currently, the United States imports the majority of minerals deemed “critical” by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS): in 2022, imports comprised over 50 percent of demand for 43 critical minerals, with 12 of those being 100 percent imported (USGS 2023). Opportunities exist to extract some of these minerals from coal wastes, which could help to establish domestic supply chains while at the same time cleaning up legacy waste sites. The carbon constituents of coal waste can also be considered as a net-zero emissions feedstock for long-lived products, as explored in Chapter 9.

Expanding upon the committee’s first report (NASEM 2023, summarized in Section 1.5), this report examines in greater depth the role of CO2 utilization in a net-zero future, where CO2 flows to the atmosphere are likely to be greatly reduced, and carbon wastes including CO2 and coal waste streams will serve as feedstocks for carbon-based chemicals and materials, as well as for carbon storage in long-lived products. The report considers how chemicals and materials manufacturing could be adapted to take advantage of carbon wastes, particularly CO2 and coal wastes, using low-carbon energy, and identifies circumstances in which CO2 and coal wastes are advantaged feedstocks over biomass and other carbon wastes such as plastics. Specifically, it analyzes market opportunities, infrastructure requirements, and research, development, and demonstration (RD&D) needs for converting CO2 into useful products, providing an update to the research agenda laid out in the 2019 National Academies’ report Gaseous Carbon Waste Streams Utilization: Status and Research Needs (NASEM 2019). It also addresses the feasibility of deriving carbon materials and critical minerals from coal waste streams.

1.2 WHAT IS CO2 UTILIZATION, AND HOW CAN IT CONTRIBUTE TO A NET-ZERO EMISSIONS FUTURE?

This study defines CO2 utilization as the chemical transformation of CO2 into a marketable product, which could include organic carbon-based fuels, chemicals, and materials (including polymers), inorganic carbonates, or elemental carbon materials. CO2 conversion can occur via chemical, biological, or mineralization routes, with each having different requirements for energy, additional feedstocks, and infrastructure. CO2 utilization processes

___________________

2 In some limited applications, it may be technically or economically difficult to replace fossil carbon feedstocks with sustainable carbon feedstocks or to develop alternative non-carbon-based solutions in the near to medium term. As a result, during the transition, for some small-volume products, net zero may still be achieved by continued manufacture from fossil feedstocks accompanied by durable offsetting capture of CO2 and geologic sequestration, or removals of CO2 from the atmosphere. In the long term, these solutions are not viable because the production cost of oil and associated carbon costs will be prohibitively high.

NOTE: The committee defines clean hydrogen as having a GHG footprint of less than 2 kg CO2 equivalent per kg H2.

SOURCE: Icons from the Noun Project, https://thenounproject.com. CC BY 3.0.

span technology readiness levels, including a few large-scale, fully commercial activities (e.g., production of urea, salicylic acid, and organic carbonates); some pilot, demonstration, or limited-scale commercial facilities (e.g., production of methanol, carbon monoxide, and mineralized CO2 products); and much research at the laboratory scale across all production routes and product classes. Priority products for CO2 utilization are detailed in Chapter 2, and Chapters 5–8 cover RD&D needs for the various CO2 utilization routes.

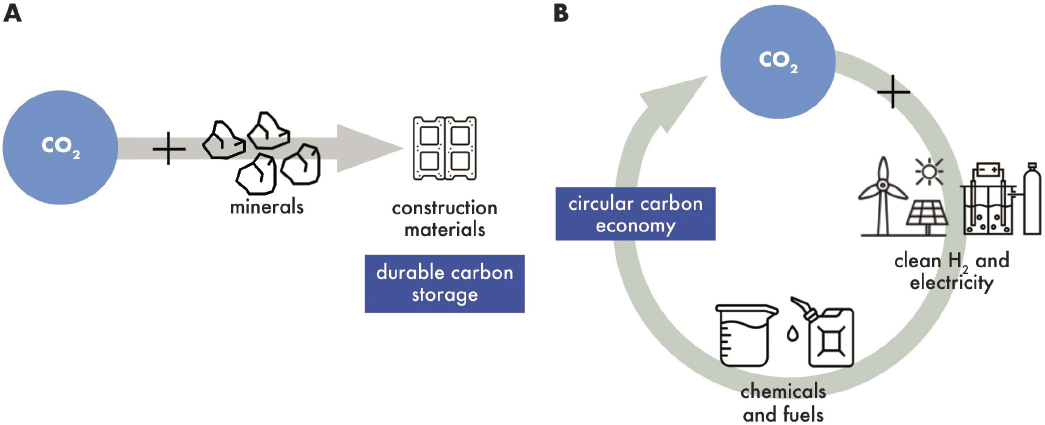

CO2 utilization has two primary roles in a net-zero future: enabling circularity of carbon flows and carbon storage (Figure 1-1). Atmospheric, aquatic, or biogenic CO2 is a feedstock for enabling a circular economy or net-zero-emissions approach to making carbon-based products,3 alongside approaches that use biomass and other waste carbon feedstocks. CO2 has several advantages and disadvantages relative to other sustainable carbon feedstocks for circularity of chemicals and materials. As a ubiquitous waste product of chemical combustion and decay, CO2 is widely available. After gas stream purification, it is a uniform, nontoxic substance that can be cleanly inserted into chemical industry processes, as compared to mixed feedstocks of biomass and recycled waste products. CO2 has lower land and, in many cases, water requirements than biomass cultivation, and it is easier to transport, although the most efficient transport is in pipelines, which can be challenging to plan and site. The primary disadvantage of CO2 is its low energy, which makes chemical transformations very energy intensive; however, this is a necessary feature of a feedstock for circular carbon fuels. CO2’s single-carbon, oxidized chemical structure requires restructuring the chemical industry around processes that use more energy and hydrogen, and can build carbon-carbon bonds. (See Section 2.2.1 on factors that impact the ease of making products from CO2.)

CO2 utilization can enable the storage of CO2-derived carbon in solid form in durable products, sequestering it from the atmosphere for climate-relevant timescales. In this role, CO2 utilization is advantageous over alternatives like land- and ocean-based carbon dioxide removal and carbon capture and storage because it creates products with market value. However, the likely scale of CO2-derived durable products is a few-gigatonnes annual global demand (Chapter 2 and NASEM 2023) compared to the projected tens of gigatonnes annual global removal required in the future (Pett-Ridge et al. 2023). Thus, geologic storage of CO2 is preferred over durable CO2-derived products for

___________________

3 Zero-carbon energy carriers such as hydrogen and electricity are preferred over carbon-based fuels where feasible, owing to the energy efficiency of electricity use in motors and hydrogen use in fuel cells over combustion of fuels, the lower land and water requirements for electricity and hydrogen relative to biomass-based systems, and the avoided conversion energy and resource requirements for formation of carbon-based products.

meeting the full needs for carbon removal. CO2 utilization is not likely to be a dominant source of carbon removal, nor of emissions mitigation for achieving net zero relative to other options for reducing emissions; however, it likely will contribute to product circularity and durable storage, where it has advantages. The extent of emissions reductions from CO2 utilization could be impacted by factors such as societal acceptance of geologic carbon storage, ability to make long-lived products, and availability of renewable energy and hydrogen resources.

The use of CO2 as a feedstock does not inherently reduce emissions relative to the use of fossil carbon feedstocks. To determine net-zero or net-negative product status, all emissions from the full product life cycle need to be considered, including upstream and downstream emissions associated with process, feedstock origin, energy use, product fate, co-product fate, and associated waste (see Chapter 3). For CO2 utilization, it is particularly important to consider and match CO2 source feedstocks and product sinks that can provide net-zero or net-negative emissions pathways. Specifically, long-lived products (lifetime >100 years4), such as concrete and aggregates, durably store carbon and can be produced sustainably with fossil or nonfossil CO2. On the other hand, short-lived products (lifetime < 100 years), such as fuels, chemicals, and many plastics, store CO2 from the atmosphere only temporarily and must be produced using atmospheric, aquatic, or biogenic sources of CO2 to participate in a circular carbon economy.

Transitioning from today’s heavily fossil fuel–dependent economy to a future economy with sustainable carbon feedstocks and net-zero or net-negative GHG emissions requires careful consideration of policies and technologies that promote emissions mitigation while ensuring that other societal needs and objectives are met. Current uses of fossil feedstocks do not include an internalized cost for the waste GHG products they emit, and as such, materials produced from fossil feedstocks are less expensive than they would be if their eventual fossil emissions to the atmosphere were priced. A future net-zero economy will require a new policy landscape to encourage net-zero or net-negative emissions technologies, and limit net-positive emissions technologies. Constraints on the use of fossil carbon will be stringent and may include preventing or pricing the incorporation of fossil-derived CO2 into products that reemit CO2 on a short timeframe (e.g., chemicals or fuels). These policies will also include economy-wide caps on emissions of fossil CO2 and/or other GHGs or a price on carbon that is sufficiently high to greatly reduce fossil emissions. Emissions constraints would build on policies already being implemented to support technology development for a net-zero transition, such as tax credits for renewable energy production and sequestration or utilization of CO2. While such forward-looking analysis is valuable to define and plan for an end goal, it overlooks complexities that will arise during the transition period as society decreases fossil fuel use. For example, in the near term when fossil emissions are being wound down, cost-effective emissions reductions may be achieved using fossil CO2 as a feedstock for chemicals and fuels, even though this approach will not provide the net-zero emissions required in the long term. Collaborative transition planning by governments and the private sector will be needed to optimize investments and minimize stranded assets. This planning is particularly relevant for CO2 utilization, where siting decisions have to consider fundamental shifts in product needs as well as matching CO2 source with product lifetime. CO2 utilization infrastructure planning is discussed further in Chapter 10, and more detail on policy options for CO2 utilization can be found in Chapter 4.

1.3 WHAT IS COAL WASTE UTILIZATION AND HOW CAN IT CONTRIBUTE TO NATIONAL NEEDS?

In addition to CO2 utilization, this report examines the feasibility of and opportunities for utilizing coal waste streams to produce carbon-based products and extract critical minerals and materials. Various waste streams arise from mining, processing, and using coal, including coal combustion residuals (fly ash, bottom ash, boiler slag, and flue gas desulfurization products), impoundment waste (coarse and fine refuse), and acid mine drainage. Coal combustion residuals are already used today as filler and raw materials in concrete, wallboard, asphalt, and other structural applications, as well as for soil modification (ACAA 2023; EPA 2023). Given the abundance, low cost, and high carbon density of coal waste streams, research efforts are targeting additional potential utilization opportunities in a wide spectrum of carbon-based products, from high-volume building materials and polymers to high-value graphite and carbon fiber (Stoffa 2023). Fly ash, wastes from coal mining and processing, and acid

___________________

4 This committee’s first report (NASEM 2023) chose a product lifetime of 100 years, in line with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, to differentiate between short- and long-lived products.

mine drainage are also potential sources of critical minerals and rare earth elements, and pilot-scale efforts are under way to develop separation and extraction processes (Kolker 2023). Using coal waste streams could enable environmental remediation, expand domestic supply chains for critical minerals and materials, and produce carbon-based products with improved performance and/or economics (Stoffa 2023). However, because these wastes contain nearly every element in the periodic table, separations can be challenging and pose safety and toxicity concerns (Kolker 2023; Stoffa 2023). Chapter 9 addresses opportunities and challenges with utilizing coal wastes.

1.4 CURRENT POLICY ENVIRONMENT FOR CO2 UTILIZATION

Most uses of CO2 within the scope of this study currently rely on subsidies or other incentives to be competitive with incumbent products, owing to various transient and persistent factors, including the unpriced costs of fossil hydrocarbon pollution from incumbent products, the small production scale of most CO2 utilization products, the still-developing CO2 utilization technologies, and the fundamental challenges of CO2 conversion into organic products. A primary policy driver in the United States is the 45Q tax credit (IRA § 13104), which provides up to $60/tCO2 for utilization (or up to $130/tCO2 if paired with direct air capture [DAC]) (IRA 2022). The 45V tax credit for clean hydrogen production (IRA § 13204) could also benefit CO2 utilization projects that require hydrogen as a feedstock, although the same facility cannot claim both the 45Q and 45V credits (IRA 2022). Additionally, the Carbon Dioxide Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation (CIFIA) program, administered through the Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Loan Programs Office with $2.1 billion in appropriations between 2022 and 2026, finances common carrier transportation infrastructure to move CO2 from the point of capture to the point of use or storage (DOE-LPO n.d.). The Utilization Procurement Grants (UPGrants) program, run by DOE’s Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management and the National Energy Technology Laboratory, will facilitate procurement and use of CO2-derived products by state and local governments and public utilities (NETL n.d.). Beyond government-funded initiatives, the voluntary carbon market and willingness of companies to pay a “green premium” for more sustainable products also support current CO2 utilization efforts.

This study focuses on needs for a net-zero future, in which there will be significant constraints on the emission of fossil-derived CO2 to the atmosphere, such as an explicit price on CO2 or a limit on emissions. The committee considers opportunities and enabling environments for CO2 utilization within this context, where there will be increased incentives for producing short-lived products in a circular carbon system, as well as for long-duration carbon storage, including in products (see Chapter 4). Applying constraints on CO2 emissions to CO2 utilization products or processes will require accounting for life cycle emissions of a CO2 utilization process and the resulting product for compliance purposes. Products originally derived from a fossil feedstock could have end-of-life emissions associated with their use or degradation, and these emissions will need to be considered and managed. Emissions associated with enabling inputs such as electricity and hydrogen, transportation of CO2 and CO2-derived products, and any upstream or downstream processing may also impact the feasibility of certain CO2 utilization pathways when total system emissions are constrained. Chapter 3 discusses life cycle assessment considerations for CO2 utilization.

1.5 BRIEF REVIEW OF FIRST REPORT’S CONCLUSIONS

The committee’s first report (NASEM 2023) examined the state of CO2 capture, utilization, transportation, and storage infrastructure and analyzed opportunities for investment in CO2 utilization infrastructure to serve a net-zero future. It found that most of the existing infrastructure, which was developed for enhanced oil recovery, does not align with opportunities for sustainable (i.e., net-zero) CO2 utilization. Thus, to evaluate future infrastructure opportunities, the committee first considered factors that would influence the extent of CO2 utilization in a net-zero economy. It found that the volume of CO2 utilized will be driven by the market value of carbon-based products and competitiveness of CO2 as a feedstock, as well as demand for services provided by carbon-based products; their relative cost compared to fossil-based products and other alternatives; availability of required inputs like clean hydrogen and clean electricity; and policy incentives and regulatory frameworks (Finding 3.10, NASEM 2023). As discussed above, another important consideration is the potential climate impact of the CO2-derived product based on the CO2 source, product lifetime, and any emissions associated with production, transportation, and use.

Considering these factors, the committee identified two priority near-term opportunities for CO2 utilization infrastructure investment: (1) combining high-purity, low-cost CO2 off-gas from bioethanol plants with clean hydrogen to make sustainable chemicals or fuels for heavy-duty transportation (e.g., shipping and aviation) and (2) mineralization using fossil or nonfossil CO2 sources to generate mineral carbonates for construction materials, including concrete (Finding 6.1, NASEM 2023). It recommended strategies for infrastructure planning, such as co-locating CO2 utilization with clean electricity, clean hydrogen, and other carbon management infrastructure; building in flexibility to connect CO2 transport infrastructure to future utilization opportunities; and developing industrial clusters to manage large volumes of CO2 without extensive pipeline networks and maintain jobs in regions with a large industrial presence (Recommendations 4.5, 6.2, 6.3, and 6.4, NASEM 2023). The committee also emphasized the importance of community engagement and equitable infrastructure development, recommending that regulatory agencies account for distributional impacts of CO2 utilization projects, engage impacted communities early and throughout the project, and allow for alterations to project design and implementation (Recommendation 5.6, NASEM 2023). This report expands upon the findings and recommendations from the first report.

1.6 REPORT TASKING, SCOPE, AND KEY CONCEPTS

A congressional mandate in the Energy Act of 2020 required DOE to enter into an agreement with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to perform a study “to assess any barriers and opportunities relating to commercializing carbon, coal-derived carbon, and carbon dioxide in the United States” (U.S. Congress 2020, § 969A). DOE commissioned that this study be undertaken in two parts. In a first report, the committee would describe the current state of infrastructure for CO2 transportation, use, and storage in the United States and identify priority opportunities for developing infrastructure to enable future CO2 utilization processes and markets in a safe, cost-effective, and environmentally benign manner. The committee released this first report in December 2022 (NASEM 2023). A second, more comprehensive report (the present report) would provide additional detail on potential markets for products derived from CO2; the economic, environmental, and climate impacts of CO2 utilization infrastructure; RD&D needs to enable commercialization of CO2 utilization technologies and processes; and opportunities for and feasibility of coal waste–derived carbon products and critical minerals. The full statement of task for the study is provided in the next section, followed by a description of the study scope and definitions of relevant concepts used in the report (Box 1-1).

1.6.1 Statement of Task

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will convene an ad hoc committee to assess infrastructure and research and development needs for carbon utilization, focused on a future where carbon wastes are fundamental participants in a circular carbon economy. In particular, the study will focus on regional and national market opportunities, infrastructure needs, and the research and development needs for technologies that can transform carbon dioxide and coal waste streams into products that will contribute to a future with zero net carbon emissions to the atmosphere. The committee will analyze challenges in expanding infrastructure, mitigating environmental impacts, accessing capital, overcoming technical hurdles, and addressing geographic, community, and equity issues for carbon utilization.

The committee will provide a first report that:

- assesses the state of infrastructure for carbon dioxide transportation, use, and storage as of the date of the study, including pipelines, freight transportation, electric transmission, and commercial manufacturing facilities.

- identifies priority opportunities for development, improvement, and expansion of infrastructure to enable future carbon utilization opportunities and market penetration. Such priority opportunities will consider how needs for carbon utilization infrastructure will interact with and capitalize on infrastructure developed for carbon capture and sequestration.

The committee will develop a second report that will evaluate the following:

- Markets

- Identify potential markets, industries, or sectors that may benefit from greater access to commercial carbon dioxide to develop products that may contribute to a net-zero carbon future; identify the markets that are addressable with existing utilization technology and that still require research, development and demonstration;

- Determine the feasibility of, and opportunities for, the commercialization of coal waste–derived carbon products in commercial, industrial, defense, and agricultural settings; for medical, construction and energy applications; and for the production of critical minerals;

- Identify appropriate federal agencies with capabilities to support small business entities; and determine what assistance those federal agencies could provide to small business entities to further the development and commercial deployment of carbon dioxide–based products;

- Infrastructure

- Building off the study’s first report, assess infrastructure updates needed to enable safe and reliable carbon dioxide transportation, use, and storage for carbon utilization purposes. Assessment of infrastructure will consider how carbon utilization fits into larger carbon capture and sequestration infrastructure needs and opportunities;

- Describe the economic, climate, and environmental impacts of any well-integrated national carbon dioxide pipeline system as applied for carbon utilization purposes, including suggestions for policies that could: (i) improve the economic impact of the system; and (ii) mitigate climate and environmental impacts of the system;

- Research, Development, and Demonstration

- Identify and assess the progress of emerging technologies and approaches for carbon utilization that may play an important role in a circular carbon economy, as relevant to markets determined in section 1a;

- Assess research efforts under way to address barriers to commercialization of carbon utilization technology, including basic, applied, engineering, and computational research efforts; and identify gaps in the research efforts;

- Update the 2019 National Academies’ comprehensive research agenda on needs and opportunities for carbon utilization technology RD&D, focusing on needs and opportunities important to commercializing products that may contribute to a net-zero carbon future.

The first and second reports will provide guidance to infrastructure funders, planners, and developers and to research sponsors, as well as research communities in academia and industry, regarding key challenges needed to advance the infrastructure, market, science, and engineering required to enable carbon utilization relevant for a circular carbon economy.

1.6.2 Scope of Report

The committee determined the limits of its scope based on the congressional mandate for the study and the study’s statement of task. The committee’s definitions of relevant concepts and explanation of the study scope are outlined below.

-

How is carbon utilization defined for the purposes of this report? What classes of carbon utilization are not in scope?

- Carbon utilization is defined for the purposes of this report as the chemical transformation of concentrated CO2 collected from the atmosphere, a body of water, or a waste gas stream into a carbon-containing product with market value.

-

- In scope:

- Chemical, microbial, and mineralization transformations of CO2.

- Out of scope:

- Processes like enhanced oil recovery, fire suppression, and beverage carbonation that leave CO2 untransformed.

- CO2 transformed into products via the growth of terrestrial plants and crops.

- In scope:

-

What sources of carbon dioxide are considered in this report?

- CO2 captured and concentrated from the atmosphere through direct air capture.

- CO2 captured from point sources before emission to the atmosphere, such as from power plants or industrial facilities.

- CO2 dissolved from the atmosphere in natural or other bodies of water, where the dissolved CO2 in those waters is used as feedstock for carbon utilization processes.

-

What pathways to activate carbon dioxide are discussed in this report?

- Chemical pathways to inorganic (mineral) products

- Chemical pathways to organic products

- Thermochemical

- Electrochemical

- Photochemical

- Plasmachemical

- Hybrid pathways

- Biological pathways to organic products

- Photosynthetic

- Algae

- Cyanobacteria

- Nonphotosynthetic

- Chemolithotrophs

- Bio-electrochemical processes

- Photosynthetic

-

To what extent is coal waste discussed in this report?

- Utilization of coal waste streams, which was not discussed in the study’s first report, is discussed herein.

- Coal waste includes coal combustion residuals (fly ash, bottom ash, boiler slag, and flue gas desulfurization products) and impoundment waste (coarse and fine refuse). Acid mine drainage also is considered as a potential source of critical minerals.

- Utilization of raw coal to produce mineral- or carbon-based products and selective mining of rare earth element-enriched portions of coal beds are out of scope for the study.

-

What product classes are discussed in this report?

- Inorganic carbonates

- Elemental carbon materials

- Fuels and commodity chemicals

- Polymer precursors and polymers

- Critical minerals and rare earth elements (only from coal waste)

-

What assessments of carbon utilization products and processes does this report examine?

- Life cycle assessments

- Techno-economic assessments

- Societal/equity assessments

-

What CO2 utilization infrastructure is considered in this report?

- CO2 utilization infrastructure systems, including capture, purification, transportation, utilization, and geologic storage.

- A U.S. regional- or national-scale pipeline system for carbon management, as applied to utilization.

- Enabling infrastructure for CO2 utilization, including for

- Hydrogen

- Electricity

- Water

- Energy storage

- Land use

- Product transportation

BOX 1-1

Key Terms and Concepts for CO2 Utilization

The following list provides definitions of key terms and concepts for CO2 utilization that are used throughout this report.

- Adoption readiness levels (ARLs)—A framework complementary to technology readiness levels (see below) that assesses the readiness of a technology for commercialization and market uptake by evaluating risks related to value proposition, resource maturity, and license to operate. The ARL scale ranges from 1 to 9, with 1–3 classified as low readiness, 4–6 as medium readiness, and 7–9 as high readiness (Tian et al. 2023).

-

Carbon capture—The process of separating and concentrating CO2 from industrial or waste gas streams, ambient air, or bodies of water.

- Direct air capture (DAC)—A technological process by which CO2 is separated and concentrated from ambient air. DAC removes CO2 from the atmosphere.

- Direct ocean capture (DOC) or capture from bodies of water—A technological process by which CO2 is separated and concentrated from the ocean or other bodies of water. DOC or capture from bodies of water indirectly results in CO2 removal from the atmosphere.

- Point source capture—A technological process by which CO2 is separated and concentrated from waste gas streams at electric power plants, industrial facilities, and other sources of combustion or process emissions. Point source capture prevents CO2 from being emitted to the atmosphere.

- Carbon dioxide removal—Technologies and processes that remove CO2 from the atmosphere and bodies of water via durable storage in products or geological, terrestrial, or ocean reservoirs. The term is used to describe both engineered technologies, such as DAC, and enhancement of natural processes, such as soil carbon storage and enhanced weathering. It does not cover natural uptake of CO2 without human intervention (Wilcox et al. 2021).

- Carbon dioxide utilization (or conversion)—The chemical or biological transformation of concentrated CO2 collected from the atmosphere, a body of water, or an industrial or waste gas stream into a carbon-containing product with market value.

-

Circular carbon economy—A system in which carbon, energy, and material flows are reduced, removed, recycled, and reused to achieve net-zero emissions (Williams et al. 2020).

- Carbon flow—The movement of carbon in various forms among land, air, water, plants, living creatures, material products, and waste.

- Community engagement—A planned process through which members of a community—either based in a geographic location or formed around people of similar interest—work collaboratively with decision makers to address issues affecting their well-being. “It involves sharing information, building relationships and partnerships, and involving stakeholders in planning and making decisions with the goal of improving the outcomes of policies and programs” (CCI 2018).

- Critical material—“Any non-fuel mineral, element, substance, or material that the Secretary of Energy determines: (i) has a high risk of supply chain disruption; and (ii) serves an essential function in one or more energy technologies, including technologies that produce, transmit, store, and conserve energy”; or a critical mineral, as defined by the Secretary of the Interior (Energy Act of 2020, § 7002).

- Decarbonization—Reducing or removing emissions of CO2 and other GHGs throughout the economy, often by transitioning to zero-carbon processes. Some processes, such as the production of sustainable aviation fuels, are often referred to as decarbonization despite not removing carbon flows; a more appropriate term is “defossilization” (see below).

- Defossilization—Reducing or eliminating the use of fossil carbon throughout the economy, such that carbon-based products are made only from nonfossil feedstocks, and flows of carbon dioxide to and from the atmosphere do not include new fossil carbon.

- Environmental justice—The just treatment and meaningful involvement of all people—regardless of income, race, color, national origin, Tribal affiliation, or disability—in agency decision making and other federal activities related to climate change, the cumulative impacts of environmental and other burdens, and the legacy of racism or other structural or systemic barriers that disproportionately and adversely affect human health and the environment (EPA 2024b).

-

Feedstocks—Material inputs to industrial processes to generate a product.

- Carbon waste streams—Carbon-based gases or materials destined for disposal, either as emissions to the atmosphere or in a landfill, which could instead be reused in products in support of a circular carbon economy. Examples in scope for this report are CO2 waste streams and coal-derived carbon wastes. Examples out of scope for this report include methane and biogas waste streams, plastic or other carbon-based product wastes, and bio-based wastes such as municipal, sanitary, and agricultural wastes.

- Fossil carbon—The carbon in crude oil, coal, and natural gas; a nonrenewable source of carbon that formed from dead plant and animal matter under high temperature and pressure over millions of years (Renewable Carbon Initiative n.d.). Fossil carbon also includes any CO2 or other waste carbon resulting from the use or decay of fossil-derived products, as well as CO2 currently present in underground reservoirs. It is unclear how mineral carbonates, such as those that are decomposed to make cement, should be classified between fossil and nonfossil carbon.

- Nonfossil carbon—Carbon derived from biogenic, atmospheric, or aquatic sources. It is unclear how mineral carbonates, such as those that are decomposed to make cement, should be classified between fossil and nonfossil carbon.

- Coal wastes—Carbon and noncarbon waste streams that are generated throughout the coal supply chain, including acid mine drainage, coal impoundment wastes, and coal combustion residuals.

- Sustainable carbon feedstock—A feedstock derived from nonfossil carbon that can support production of chemicals and materials in a net-zero-carbon economy without emissions from product degradation and decay.

- Geologic carbon sequestration—“The process of storing carbon dioxide in underground geologic formations. The CO2 is usually pressurized until it becomes a liquid, and then it is injected into porous rock formations in geologic basins” (USGS n.d.).

-

Integrated system—A system combining two or more CO2 capture and/or utilization routes to produce any of the product classes within the scope of this report (inorganic carbonates, elemental carbon materials, chemicals, fuels, polymers). CO2 conversion approaches could include mineralization, thermochemical, electrochemical, photo(electro)chemical, plasmachemical, or biological routes.

- Hybrid process—A type of integrated system, typically used in the context of biological CO2 utilization, involving the coupling of electro-, thermo-, photo-, or plasma-chemical conversion with bioconversion.

- Tandem process—A type of integrated system where two or more CO2 conversion routes are combined to occur in sequence. Tandem processes can occur on varying scales—for example, different conversions in separate coupled reactors, different conversions in the same reactor, or different conversions occurring at multiple sites on a single material.

-

Life cycle assessment—An analysis of the environmental impacts, including but not limited to CO2 flows, of a product, process, or system throughout its entire life cycle, from raw material extraction (cradle) to end of life (grave).

- Upstream emissions—“Indirect emissions related to a reporting company’s suppliers, from the purchased materials that flow into the company to the products and services the company utilizes” (Persefoni 2023).

- Downstream emissions—“The emissions related to customers, from selling goods and services to their distribution, use, and end-of-life stages” (Persefoni 2023).

- Linear carbon economy—A system in which carbon, in the form of fossil fuels, is extracted and converted to valuable products and energy, which upon use or degradation emit CO2 to the atmosphere without being reutilized (Williams et al. 2020).

-

Net-negative emissions—The condition in which flows of CO2 equivalents to the atmosphere are less than those removed from the atmosphere by technological or natural processes.

- Negative emissions—A technology results in negative emissions if it removes physical emissions from the atmosphere, if the removed gases are stored out of the atmosphere in a manner intended to be permanent, if upstream and downstream GHG emissions associated with the removal and storage process, such as biomass origin, energy use, gas fate, and co-product fate, are comprehensively estimated and included in the emission balance, and if the total quantity of atmospheric GHGs removed and permanently stored is greater than the total quantity of GHGs emitted to the atmosphere. To fully understand climate impacts, evaluations of negative emissions technologies also need to estimate biogeophysical and potential nonlinear effects on Earth systems (Zickfeld et al. 2023).

- Net-negative emissions compatible—A process that has the potential to result in net-negative emissions to the atmosphere over the course of its life cycle.

- Net-positive emissions—The condition in which flows of CO2 equivalents to the atmosphere are greater than those removed from the atmosphere by technological or natural processes.

-

Net-zero carbon or net-zero GHG emissions—The condition in which flows of CO2 equivalents to and from the atmosphere are equal—that is, emissions of CO2 and other GHGs are offset by removal of an equivalent amount through technological or natural processes.

- Net-zero emissions compatible—A process that has the potential to result in net-zero emissions to the atmosphere over the course of its life cycle.

-

Product lifetime—The amount of time between production and end of use or degradation of a product.

- Long-lived product or durable storage product (Track 1)—In the current report, a product with a lifetime of more than 100 years, which stores CO2 long enough to have a climate-relevant storage impact.

- Short-lived product or circular carbon product (Track 2)—In the current report, a product with a lifetime of less than 100 years, which decomposes back to CO2 in a short timespan, and which requires participation in a circular carbon economy for sustainability.

- Public engagement—The multifaceted ways in which people are involved in decisions about policies, programs, and services that impact issues of common importance and seek to solve shared problems.

- Techno-economic assessment—An integrated assessment of technical performance and economic feasibility that combines process modeling and engineering design with an economic evaluation to assess the (future) viability of a process, system configuration, or product.

- Technology readiness level (TRL)—“A type of measurement system used to assess the maturity level of a particular technology” (Manning 2023). This report uses the Department of Energy (DOE) TRL scale definitions, which range from TRL 1 “basic principles observed and reported” to TRL 9 “actual system operated over the full range of expected conditions.” (see Table 1 of DOE 2015). Validation of components in the laboratory occurs at TRL 4, engineering or pilot-scale demonstration at TRL 6, and full-scale system demonstration at TRL 7.

- Zero-carbon—A product, technology, or process that does not require carbon flows for its operation, does not lead to emission of CO2 to the atmosphere, and may not require any carbon-based materials at all. Often used to refer to products, technologies, or processes that can replace carbon-based products in a decarbonized economy, such as solar electricity generation replacing fossil fuel electricity generation.

1.7 OVERVIEW OF REPORT CHAPTERS AND CONTENT

This introductory chapter provides context and motivation for the study, describes the connection between this report and the committee’s first report, and explains the study tasking and scope. Chapter 2 identifies market opportunities and requirements for carbon utilization in a net-zero future, considering the projected demand for carbon-based products and cases where CO2 or coal waste is an advantageous feedstock. This is followed in Chapter 3 by a discussion of life cycle, techno-economic, and societal/equity assessments of CO2 utilization processes, technologies, and systems. Chapter 4 assesses policy and regulatory frameworks needed to support sustainable CO2 utilization; opportunities for small businesses to compete for CO2 as a commodity; and environmental justice considerations when selecting, siting, and developing CO2 utilization projects. Together, Chapters 2–4 lay the groundwork for understanding how and where CO2 utilization could contribute to a net-zero future.

The next four chapters focus on RD&D needs for CO2 utilization technologies and processes to generate inorganic carbonates (Chapter 5); elemental carbon materials (Chapter 6); and chemicals, fuels, and polymers via chemical routes (Chapter 7) or biological routes (Chapter 8). Chapter 9 examines the feasibility of and opportunities for deriving carbon-based materials and critical minerals from coal wastes. Chapter 10 discusses infrastructure needed to support CO2 utilization, building on the first report’s analysis with more detail on integrated infrastructure planning and the economic, environmental, health and safety, and environmental justice impacts of CO2 utilization infrastructure development. Chapter 11 discusses the crosscutting research needs of CO2 capture and purification and presents a research agenda for CO2 and coal waste utilization, based on the committee’s analyses in Chapters 5–9.

1.8 REFERENCES

ACAA (American Coal Ash Association). 2023. “About Coal Ash: What Are Coal Combustion Products?” ACAA. https://acaa-usa.org/about-coal-ash/what-are-ccps.

CCI (California Climate Investments). 2018. “Best Practices for Community Engagement and Building Successful Projects.” https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/auction-proceeds/cci-community-leadership-bestpractices.pdf.

DOE (Department of Energy). 2015. “Technology Readiness Assessment Guide.” DOE G 413.3-4A. Washington, DC: Department of Energy.

DOE-LPO (Loan Programs Office). n.d. “Carbon Dioxide Transportation Infrastructure.” https://www.energy.gov/lpo/carbon-dioxide-transportation-infrastructure.

DOS and EOP (Department of State and Executive Office of the President). 2021. “The Long-Term Strategy of the United States: Pathways to Net-Zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 2050.” Washington, DC: Department of State and Executive Office of the President. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/US-Long-Term-Strategy.pdf.

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 2023. “Frequent Questions about the Beneficial Use of Coal Ash.” https://www.epa.gov/coalash/frequent-questions-about-beneficial-use-coal-ash.

EPA. 2024a. “Learn About Environmental Justice.” February 6. https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/learn-aboutenvironmental-justice.

EPA. 2024b. “Understanding Global Warming Potentials.” March 27. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/understanding-globalwarming-potentials.

IEA (International Energy Agency). 2022. “The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions.” World Energy Outlook Special Report. Paris, France: International Energy Agency. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/ffd2a83b-8c30-4e9d980a-52b6d9a86fdc/TheRoleofCriticalMineralsinCleanEnergyTransitions.pdf.

IRA (Inflation Reduction Act). 2022. H.R. 5376—Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. Public Law 117-169. 117th Congress (2021–2022). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376.

Kolker, A. 2023. “Rare Earth Elements and Critical Minerals in Coal and Coal Byproducts.” Presented at the Carbon Utilization Infrastructure, Markets, Research and Development Meeting #4. Virtually. June 28, 2023. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/40093_06-2023_carbon-utilization-infrastructure-markets-research-and-development-meeting-4.

Manning, C.G. 2023. “Technology Readiness Levels.” NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/somd/space-communications-navigation-program/technology-readiness-levels.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2019. Gaseous Carbon Waste Streams Utilization: Status and Research Needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25232.

NASEM. 2021. Accelerating Decarbonization of the U.S. Energy System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25932.

NASEM. 2023. Carbon Dioxide Utilization Markets and Infrastructure: Status and Opportunities: A First Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26703.

NETL (National Energy Technology Laboratory). n.d. “Utilization Procurement Grants (UPGrants).” https://www.netl.doe.gov/upgrants.

Persefoni. 2023. “Upstream vs Downstream: Breaking Down Scope 3.” Persefoni, July 7. https://www.persefoni.com/learn/upstream-vs-downstream.

Pett-Ridge, J., H.Z. Ammad, A. Aui, M. Ashton, S.E. Baker, B. Basso, M. Bradford, et al. 2023. “Roads to Removal: Options for Carbon Dioxide Removal in the United States.” LLNL-TR-852901. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. https://roads2removal.org.

Renewable Carbon Initiative. n.d. “Glossary.” Renewable Carbon Initiative. https://renewable-carbon-initiative.com/renewable-carbon/glossary.

Stoffa, J. 2023. “Carbon Ore Processing Program.” Presented at the Carbon Utilization Infrastructure, Markets, Research and Development Meeting #4. Virtually. June 28. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/40093_06-2023_carbon-utilization-infrastructure-markets-research-and-development-meeting-4.

Tian, L., J. Mees, V. Chan, and W. Dean. 2023. “Commercial Adoption Readiness Assessment Tool (CARAT).” Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2023-03/Commercial%20Adoption%20Readiness%20Assessment%20Tool%20%28CARAT%29_030323.pdf.

U.S. Congress. 2020. “Division Z—Energy Act of 2020.” H.R.133—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021. Public Law 116-260. 116th Congress (2019–2020). https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ260/PLAW-116publ260.pdf.

USGS (U.S. Geological Survey). 2023. “Mineral Commodity Summaries 2023.” Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey. https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2023/mcs2023.pdf.

USGS. n.d. “What’s the Difference Between Geologic and Biologic Carbon Sequestration?” https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/whats-difference-between-geologic-and-biologic-carbon-sequestration.

Wilcox, J., B. Kolosz, and J. Freeman. 2021. “Carbon Dioxide Removal Primer.” https://cdrprimer.org.

Williams, E., A. Sieminski, and A. al Tuwaijri. 2020. “CCE Guide Overview.” Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center. https://www.cceguide.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/00-CCE-Guide-Overview.pdf.

Zickfeld, K., A.J. MacIsaac, J.G. Canadell, S. Fuss, R.B. Jackson, C.D. Jones, A. Lohila, et al. 2023. “Net-Zero Approaches Must Consider Earth System Impacts to Achieve Climate Goals.” Nature Climate Change 13(12):1298–1305. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01862-7.