Carbon Utilization Infrastructure, Markets, and Research and Development: A Final Report (2024)

Chapter: 7 Chemical CO2 Conversion to Fuels, Chemicals, and Polymers

7

Chemical CO2 Conversion to Fuels, Chemicals, and Polymers

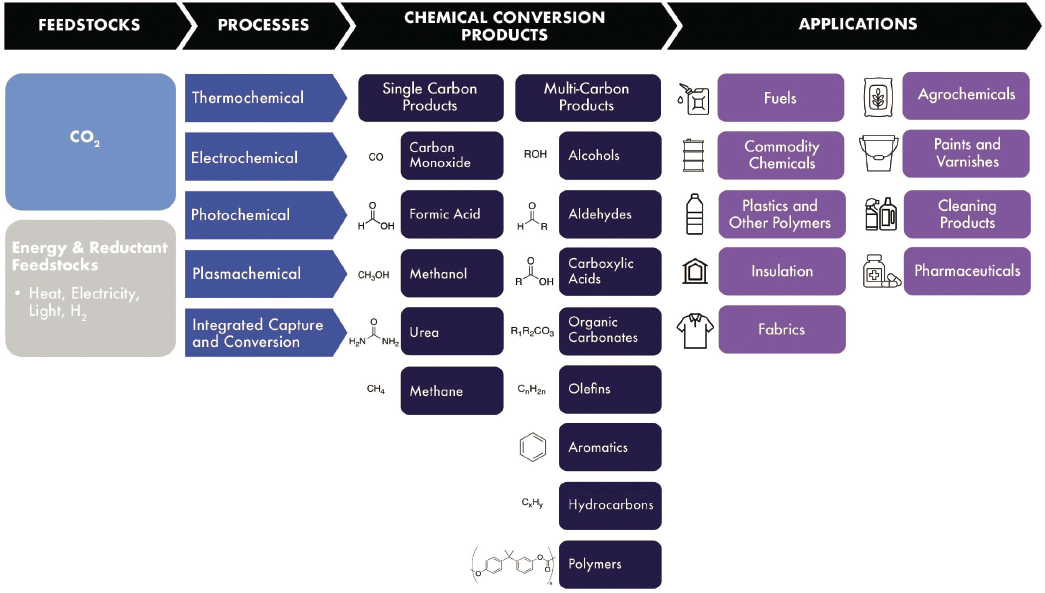

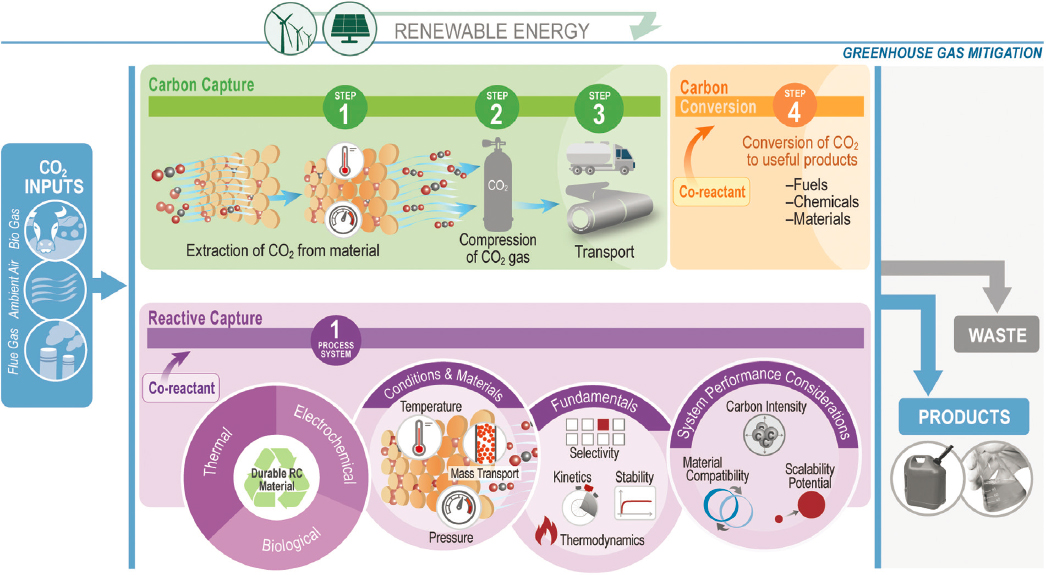

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a potential feedstock for sustainable synthesis of carbon-based materials in a net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions future. As noted in previous chapters, most of the carbon in products that are manufactured and used today is derived from fossil feedstocks like natural gas and petroleum. Chapter 2 described markets for future products and intermediates derived from CO2, as well as the competitive alternatives of electrification and clean hydrogen to replace carbon-based fuels for energy and energy storage, biomass and recycled plastic or material waste as feedstocks for carbon-based products, and extensive cradle-to-grave carbon capture and storage with continued fossil production of chemical and material products. This chapter focuses on chemical transformations of CO2 into organic products where CO2 utilization has some competitive advantages in a net-zero future, at a scale and impact that warrants national U.S. research and development (R&D) investment (see Sections 2.2.5.2, 2.2.5.3, and 2.2.5.4). As shown in Figure 7-1, these products include fuels, chemical intermediates, commodity chemicals, and polymers and their precursors, and they can be produced by a variety of chemical processes. The remainder of the chapter describes the current status and R&D needs for chemical CO2 conversion processes and the resulting products, noting relevant applications where appropriate.

7.1 OVERVIEW OF CHEMICAL CONVERSION ROUTES FROM CO2 TO ORGANIC PRODUCTS

7.1.1 Organic Chemical Products That Can Be Derived from CO2

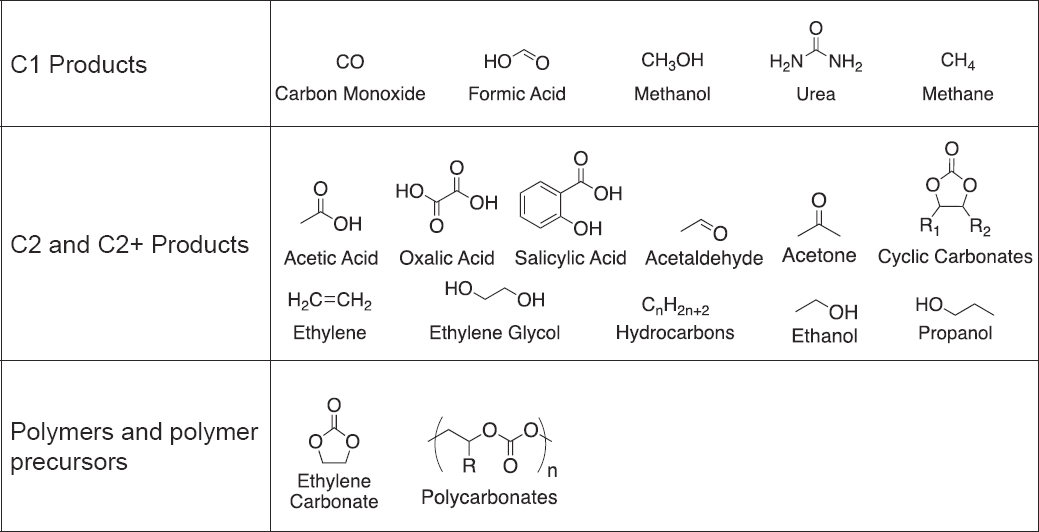

In principle, any carbon-based product can be formed chemically from CO2. This report focuses on conversion of CO2 to priority products in a net-zero future, including single carbon (C1) products, such as carbon monoxide, methanol, formic acid, urea, and methane, and multicarbon products, such as polycarbon oxygenates (alcohols, aldehydes, carboxylic acids, organic carbonates), olefins, aromatics, and hydrocarbons, including fuels (Figure 7-2). (See Chapter 2 for a detailed discussion of potential future market needs.) This chapter builds on Chapter 4 of the 2019 National Academies’ report Gaseous Carbon Waste Streams Utilization: Status and Research Needs (NASEM 2019).

Carbon-based organic chemicals include compounds of carbon and hydrogen, with or without additional elements such as oxygen and nitrogen. The modern chemical industry developed to use petroleum as a source of both carbon and energy that is inexpensive, easy to ship, and contains advantageous carbon-carbon bonds. Large-volume

SOURCE: Icons from the Noun Project, https://thenounproject.com. CC BY 3.0.

chemical intermediates such as methanol, ethylene, propylene, benzene, toluene, and xylenes (Ellis et al. 2023) underlie the production of most other final products and so are particularly important parts of the chemical market. Manufactured organic chemical products pervade modern life. Their applications include fuels; plastics and other polymers for pipes, insulation, and fabrics; agrochemicals including fertilizers; paints and varnishes; cleaning products; pharmaceuticals; and more. As the global economy transitions to one with net-zero emissions, the need for these products will remain, but they will have to be produced from a non-fossil-carbon feedstock.

Alternatives to chemical production from petroleum have been explored and developed when access to petroleum was constrained (such as during wars or trade embargoes), when other resources were abundant and inexpensive relative to petroleum, or when there was an interest to diversify potential carbon sources away from only petroleum, such as domestic biofuel (EPA 2018; Lamprecht 2007; NRC 2006). Technologies and processes to use alternative carbon feedstocks of coal, natural gas, and biomass and its derivatives were developed, including the production of hydrocarbon chemicals and fuels via “syngas” (carbon monoxide and hydrogen). In a net-zero future, petroleum use as a chemical feedstock likely will be highly constrained owing to costs or limits on the resulting CO2 emissions from the product life cycle. In this scenario, CO2 is one option of sustainable carbon feedstock to replace petroleum. In addition to a change in feedstocks for chemicals production, the routes to produce chemicals could proceed via different priority intermediates than those currently used in the chemical industry, owing to the different properties of CO2 as a feedstock as compared to petroleum. This chapter describes routes to potential future priority intermediates as well as final products.

Although not discussed in detail in this chapter, simply using CO2 as a feedstock does not eliminate net GHG emissions from the life cycle of organic chemical production. CO2 and other GHG emissions associated with the production of CO2 and other feedstocks, transformation of the feedstocks into the product, delivery of the product to the user, use of the product, and its eventual disposal or recycling also have to be eliminated. See Chapter 3 for more discussion of life cycle assessments for CO2 utilization.

7.1.2 Conversion Routes

There are several approaches to chemical conversion of CO2 to organic products, all of which are geared toward overcoming the main challenges of using CO2 as a chemical feedstock: its stability/nonreactivity, lack of carbon-carbon bonds, and presence as a dilute gas under ambient conditions. The ability of CO2 to serve as a sustainable carbon feedstock is tied to these properties, as it is the primary waste product of combustion and other organic-molecule decomposition processes. Formation of most organic products from CO2 requires energy input to overcome reaction barriers, some portion of which becomes energy stored in the product. Catalysts are often required to facilitate faster, more selective reactions. Thermochemical, electrochemical, photochemical, and plasmachemical reactions, as well as integrated CO2 capture and conversion, can incorporate both energy input and catalysis into CO2 conversion processes. Comparisons of “practical” energy requirements for different conversion pathways is challenging, as researchers often report different metrics for efficiency. Calculating the free energy of CO2 conversion to a given product is possible, but unproductive, as the actual amount of energy required will exceed the theoretical limit and vary by process. The committee’s first report quantified energy requirements for various carbon capture and hydrogen production processes, as well as the stoichiometric hydrogen requirements for several carbon-based products (see Figures 3-6, 3-7, and 3-8 in NASEM 2023). The following sections highlight status, challenges, and R&D opportunities for chemical CO2 conversion processes in a net-zero future.

7.2 EXISTING AND EMERGING PROCESSES, CHALLENGES, AND R&D OPPORTUNITIES

Chemical conversions of CO2 into organic chemicals span across technology readiness levels (TRLs). Figure 7-3 illustrates different pathways—thermochemical, electrochemical, photochemical, and plasmachemical—to produce organic chemicals from CO2 and describes the technical maturity of the most advanced design of each process type. The following sections discuss current technologies, challenges, and R&D opportunities for each of these conversion pathways, as well as for integrated capture and conversion and the production of polymers from CO2.

![Schematic of CO2 utilization processes to produce priority chemicals, fuels, and intermediates in a net-zero future, including maturity (approximate technology readiness level [TRL]) of the most advanced design of each process type: thermochemical, electrochemical, photochemical, or plasmachemical](https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/27732/assets/images/img-250.jpg)

NOTES: All paths begin with CO2 capture (point source capture or direct air capture), then conversion of the CO2 (blue) into intermediates of CO (pink) or methanol (green), or directly to products (black bold). Conversion of CO or methanol to products, or to olefin intermediates (yellow) is also shown, along with olefin conversion to plastics.

7.2.1 Thermochemical Conversion Pathways

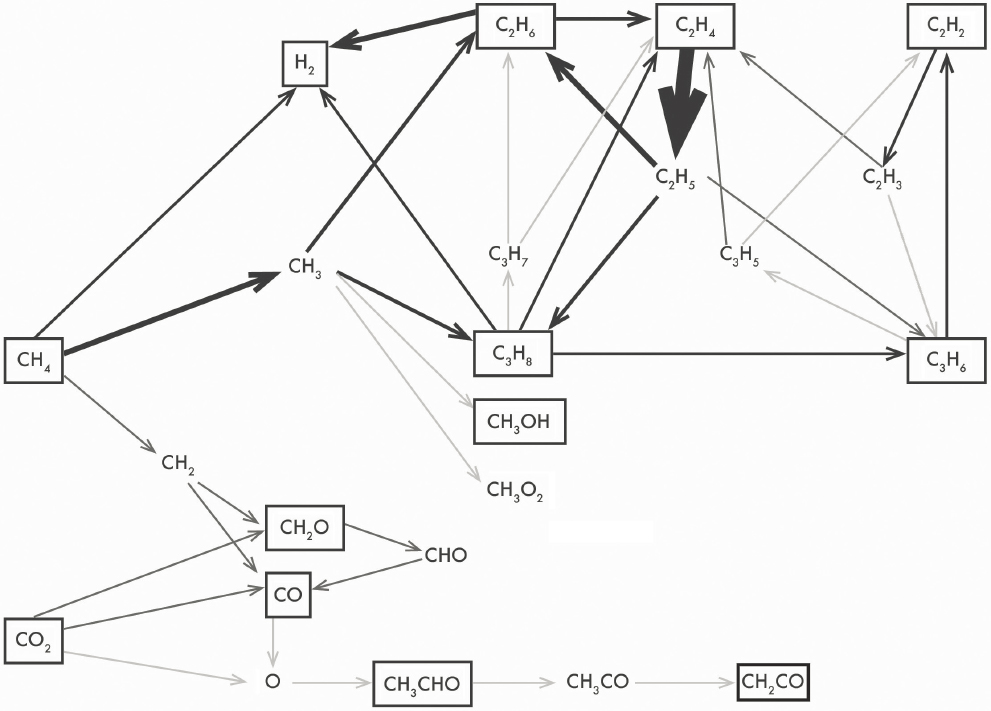

This section describes pathways for thermochemical conversion of CO2 into the following products: carbon monoxide (CO) and synthesis gas (“syngas”: a mixture of CO and H2); methanol and its derivatives; formate/formic acid; C2+ hydrocarbons, oxygenates, and intermediates; C2 and C2+ carboxylic acids; fuels from Fischer-Tropsch synthesis using CO produced from CO2; and polymer precursors. It begins by describing current technologies and processes for these conversions, followed by discussions of the challenges with and R&D opportunities for thermochemical CO2 conversion. More emphasis is placed on the importance of CO2-derived intermediates than final products, as the steps to produce final products are well known once key intermediates are produced. Thermochemical conversion pathways and associated products are shown in Figure 7-4 and Table 7-1.

NOTE: CO2 source in gray, processes in purple, products in pink.

7.2.1.1 Current Technology

Carbon Monoxide and Syngas

CO2 conversion to CO is a key initial reaction for thermocatalytic pathways to hydrocarbon products. Processes for converting CO and its mixture with H2 (syngas) into various hydrocarbons have been subject to ongoing research for continuous improvement for more than a century. Once syngas is formed, a full set of proven commercial pathways are known for comprehensive chemical synthesis across all molecules comprising the current hydrocarbon chemicals economy (Cho et al. 2017; Xie and Olsbye 2023).

TABLE 7-1 Key Products from Thermochemical CO2 Conversion and Processes for Their Formation

| Product | Processes for Formation from CO2 |

|---|---|

| Carbon monoxide and syngas |

|

| Methanol and derivatives |

|

| Formate and formic acid |

|

| C2+ hydrocarbons, oxygenates, intermediates |

|

| Polymer precursors |

|

CO forms readily by hydrogenating CO2 in the reverse water-gas shift (RWGS) reaction (Reaction 7.1).1 Albeit typically in the presence of a catalyst. The RWGS (and forward water-gas shift [WGS]) reaction is equilibrium constrained, with conversion affected by temperature, which impacts the equilibrium and kinetics, and to a moderate degree by pressure (influencing reaction rates); RWGS reaction kinetics are well documented (Bustamante et al. 2004; Chen et al. 2020).

| RWGS reaction: CO2 + H2 ⇌ CO + H2O | (R7.1) |

The RWGS reaction typically uses copper or platinum, palladium, or rhodium catalysts supported on redox catalysts or supports such as ceria (CeO2) (Ye et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2017), rather than the alumina-supported catalysts used for the forward WGS reaction, to avoid acidity that can lead to coking at the higher temperatures used for RWGS. While well-known catalysts for the forward reaction can also perform the reverse reaction, new formulations could offer improved performance at the temperatures and pressures required and with impurities present. For example, platinum-doped cerium oxide catalysts offer higher RWGS reaction rates and yields, at the expense of requiring a noble metal (Ampelli et al. 2015). For syngas production via RWGS to be economically viable, improvements in CO yield, CO productivity, and catalyst durability are also needed. As of yet, the RWGS reaction has not been fully developed because there has been no economic incentive to do so in the absence of a price on fossil carbon. However, several studies have examined potential catalysts for the reaction: Dimitriou et al. (2015) review the approach for liquid fuels production; Chen et al. (2020) describe formulation of metal versus metal-oxide catalyst to improve tolerance to poisons; Zhang et al. (2022a) present a molybdenum phosphide–based catalyst to avoid use of noble metals; and Daza and Kuhn (2016) review catalyst options for producing liquid fuels by CO2 hydrogenation. See Section 7.2.1.3 for more on catalyst development opportunities.

Another pathway for generating syngas is high-temperature solar thermochemical splitting of CO2 and water (Al-Shankiti et al. 2017; Pullar et al. 2019; Wenzel et al. 2016). Use of solar thermochemical technologies for hydrogen generation2 has lagged photovoltaic (PV)-electrolysis as a promising pathway for renewable hydrogen production, given the lower costs of PV electricity generation. However, solar thermochemical technologies for CO2 splitting may be cost-effective for hydrocarbon product synthesis because of the ability to integrate with energy/heat storage and recuperation to enable 24/7 industrial operations. Thermal cycling of the working redox materials and differential thermal expansion are issues for system design and durability.

Syngas also can be produced by catalytic dry reforming of methane, which uses CO2 as a soft oxidant and additional source of carbon: CO2 + CH4 ⇌ 2CO + 2H2, where half of the carbon and all of the oxygen come from CO2, and half of the carbon and all of the hydrogen come from methane (see, e.g., Shi et al. 2013). Dry reforming produces a syngas composition with CO/H2 ratio of 1, which is too rich in CO for methanol or other chemical synthesis, other than addition to olefins or epoxides via hydroformylation, which has limited market size and hence limited ability to uptake CO2 into products. Water-gas shift to remove some of the CO yields more H2 but results in additional CO2 formation, which via the subsequent reaction network of C1 chemistry (including the large endothermic heat of reaction for CO2 conversion) results in a net increase rather than consumption of CO2 (Sandoval-Diaz et al. 2022). CO separation via chemical looping or carbon rejection via solid nanofibers, or injection of additional clean H2 is needed to render dry reforming a viable pathway for chemical production (Challiwala et al. 2021), except for limited market volume products (e.g., dimethyl ether) where a 1:1 syngas ratio is directly consumed. Some process flue gas compositions also may benefit from a 1:1 syngas composition for some retrofit applications. Dry reforming can be used in conjunction with renewable methane3 to expand sequestration of carbon into products and synergistically produce solid carbon (see, e.g., Azara et al. 2019 and Chapter 6 of this report). However, the high temperatures required for CO2 conversion

___________________

1 RWGS is a stoichiometric reaction that converts CO2 into CO by consumption of H2. Typically, one adds an excess of H2 so that once a given amount of CO2 is “shifted” to CO, one has the desired ratio of H2/CO for subsequent reactions. Alternatively, one can add excess H2 after the RWGS reaction to obtain a desired ratio.

2 For more information on solar thermochemical technologies for hydrogen production, see Wexler et al. (2023).

3 Renewable methane is methane sourced from nonfossil feedstocks, like biomass, municipal solid waste, and other waste carbon-containing materials, like plastics.

by thermochemical dry reforming leads to substantial catalyst coking which, together with the need for carbon rejection to address the problem of incorrect (low) syngas ratio for most large-scale products, has limited commercial applications (Sandoval-Diaz et al. 2022).

Methanol and Derivatives

Pathways to convert CO2 to methanol include direct hydrogenation and a two-step process of RWGS followed by methanol production from syngas (Elsernagawy et al. 2020). The status of commercial pathways for methanol production from syngas has been reviewed by the National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL n.d.(a)). In general, conversions and yields for direct CO2 hydrogenation to methanol are lower than for the two-step process via syngas under standard conditions owing to poorer activity and formation of additional water as a coproduct.

Research efforts have targeted improvements in yield and selectivity of direct CO2 conversion to methanol (Jiang et al. 2020; Ye et al. 2019). For example, increasing H2/CO2 ratios to 10 and operating at higher pressure (35 MPa) allows direct conversion to methanol above 95 percent yield with 98 percent selectivity for a conventional copper/zinc oxide/alumina (Cu/ZnO/Al2O3) catalyst (Bansode and Urakawa 2014). Use of dispersed copper nanoparticles encapsulated in metal organic frameworks via strong support interactions shows enhanced activity, near 100 percent selectivity to methanol, and reduced catalyst sintering while preventing agglomeration of the copper nanoparticles (Rungtaweevoranit et al. 2016). Zirconium dioxide acts as a promoter and support in copper-based catalysts for CO2 conversion to methanol (Lam et al. 2018). Catalysts incorporating indium (III) oxide on nickel or nickel-indium-aluminum/silica (Ni-In-Al/SiO2) enhance rates for low-pressure methanol synthesis (Richard and Fan 2017). Bifunctional catalysts are being developed that couple CO2 hydrogenation to methanol via copper, indium, or zinc-based catalysts with methanol dehydration or coupling using zeolites (Ye et al. 2019).

The CAMERE process provided an early pilot of two-step methanol production via RWGS and methanol synthesis (Joo et al. 1999). Samimi et al. (2018) examined addition of an in situ membrane for water removal during methanol synthesis using the CAMERE process, which showed improvements in methanol yields, as removal of water is expected to improve catalyst life. Subsequent analysis identified membrane options for enhancing RWGS in packed-bed membrane reactors (Dzuryk and Rezaei 2022).

From methanol, the subsequent steps to produce gasoline or olefins are fully developed and have initial commercial units in China (Gogate 2019). Methanol-to-olefins results in a ratio of C2=/C3= product from 0.7 to 1.1, whereas current technology from ethane (cracking) or propane (dehydrogenation) can give better than 90 percent yields of a specific olefin (Tian et al. 2015). Selective conversion of methanol to light olefins (ethylene, propylene) is essential for providing key intermediates for the chemical economy and can be achieved via catalyst and reactor optimization (Jiao et al. 2016; Tian et al. 2015). A process for converting methanol to gasoline has been demonstrated, and commercial operations are planned (NETL n.d.(b)). Methanol conversion to aromatics is also known and would allow coverage of a full spectrum of CO2 to polymer and chemical intermediates (Sibi et al. 2022). Methanol carbonylation is fully commercial at industrial scale. However, use of earth abundant metals in place of rhodium and iridium and avoidance of corrosive halogen promoters remain goals for practice of more sustainable, green chemistry (Kalck et al. 2020).

Formate and Formic Acid

Thermocatalytic routes to synthesize formate or formic acid from CO2 have been reported using molecular (homogeneous) catalysts, which also have relevance for direct methanol synthesis from CO2 (Wang et al. 2015a). Behr and Nowakowski (2014) reviewed both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts as well as attempts to develop commercial systems. Homogeneous catalysts based on ligand-modified platinum group metals are active for formate/formic acid production, with ruthenium, rhodium, and iridium showing highest activity, but are challenged by performance, cost, and low element abundance at commercial scale, which impedes industrial consideration. Significant activity is only achieved in the presence of base to produce formate salts instead of formic acid, which drives the endergonic reaction but inhibits product separation and adds cost. A wide variety of mono- or bidentate phosphine or amine ligands impart changes in steric effects and electron density that modify activity and selectivity, giving rise to a rich domain for experimentation. Recent developments include improved rates for

iron- or cobalt-based homogeneous catalysts promoted with phosphine ligands, but these systems again require expensive promoters for activity, either a base as in the precious metals catalysts, or a Lewis acid (Bernskoetter and Hazari 2017; Filonenko et al. 2018). Heterogeneous catalysts were known as early as 1932 (Raney nickel; Covert and Adkins 1932) but give poorer yields. Overall, direct thermocatalytic CO2 hydrogenation to formic acid or formate has progressed significantly because extensive exploration began in the 1970s, but the relatively low turnover frequencies, difficult separations, and expensive components have limited commercial deployment. Electrochemical approaches could be highly competitive in this space (see Section 7.2.2). Currently, formic acid is made on a 0.8 kiloton per annum global scale via thermocatalytic carbonylation of methanol to methyl formate, followed by base-catalyzed hydrolysis to formic acid and methanol (Hietala et al. 2016); it can potentially be made for small-scale markets via bioprocessing. The use of formic acid or formate at a larger scale—for instance, as a transport medium for syngas—would require process technology optimization and scale up, if this were found to be a competitive pathway versus methanol production.

One-Step C2+ Hydrocarbons, Oxygenates, and Intermediates

C-C bond coupling to form C2+ hydrocarbons and oxygenates is a challenge for thermochemical CO2 activation, although it is an area of active research (Fors and Malapit 2023; Pescarmona 2021; Zhang and Hou 2013). Coupling with epoxides is one means of activating CO2 (Kothandaraman and Heldebrant 2020).4 Multistep pathways to C2+ products via syngas formation followed by Fischer-Tropsch are described below, and multistep pathways to C2+ products via syngas formation followed by methanol synthesis and subsequent reactions to olefins or gasoline were described above.

“One-pot” synthesis of C−C bonded products can be attempted via either the methanol or Fischer-Tropsch synthesis routes, to save capital expenditure and simplify the number of process steps (Ye et al. 2019). The initial reaction of CO2 with H2 (RWGS) must overcome the high reaction activation energy of CO2 and equilibrium, and hence requires high temperature (950°C). To attempt a one-pot synthesis to yield methanol as an intermediate for coupling to olefins or dimethyl ether, the subsequent reaction(s) also must be able to take place selectively at high temperature. While multistep pathways from CO2 to methanol and derivatives or to Fischer-Tropsch products can exhibit high conversion at C−C yields of 80 percent or better, one-pot synthesis yields are restricted to 50 percent or lower because the subsequent conversion steps have to be conducted at the same high temperature as the RWGS reaction (Ye et al. 2019). Nonetheless, considerable research efforts continue for one-pot synthesis routes, given their potential lower costs.

C2 and C2+ Carboxylic Acids

CO2 has been widely explored as a carboxylation agent in the production of C2 and C2+ carboxylic acids, enabling more sustainable syntheses compared to current industrial methods, although catalytic approaches remain largely at the basic research stage (Cauwenbergh et al. 2022; Davies et al. 2021; Tortajada et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2024). Unlike other CO2 conversions discussed in this chapter, these carboxylation reactions do not use CO2 as the source of all carbon atoms in the target compound, but rather as the source of a carboxyl group. Both heterogeneous (Zhang et al. 2024) and homogeneous (Cauwenbergh et al. 2022; Tortajada et al. 2018) catalytic systems have been studied, with palladium, rhodium, nickel, copper, and cobalt being among the most common metals for catalysis. A wide range of products are accessible through the various catalytic reaction pathways for carboxylation with CO2, which include nucleophilic addition of organometallic reagents, reductive coupling with organic (pseudo)halides, reaction with unsaturated hydrocarbons, and functionalization of sp, sp2, and sp3 hybridized C−H bonds (Davies et al. 2021; Tortajada et al. 2018). Synthesis of acrylic acid from CO2 and ethylene is of particular industrial interest given the widespread applications of these compounds in manufacturing and consumer products (Davies et al. 2021; Tortajada et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2017).

___________________

4 Epoxides are unstable molecules that require high energy for synthesis. For sustainable processing, the C2 epoxide co-reactant would have to be made from CO2 as well, via formation of syngas, synthetic methanol-to-olefins, and epoxidation of ethylene, for example. The other feedstocks and energy inputs for CO2-to-epoxide conversion would also need to have net-zero emissions on a life cycle basis.

Hydrocarbons from Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis

Fischer-Tropsch synthesis is a surface chain-growth polymerization reaction (Anderson-Schulz-Flory distribution) that converts syngas into a range of hydrocarbon products. Conversion of syngas to diesel and chemical products (waxes and lubricants) is fully commercial at the industrial refinery scale (see NETL n.d.(c)). Thus, generation of syngas from CO2, as described above, can enable production of fuels and commodity chemicals using already existing commercial methods, although this is not currently viable at scale (see Section 7.2.1.2).

The synthesis reactions between CO and H2 can be written as (Martín and Grossman 2011):

| nCO + (n+m/2)H2 → CnHm + nH2O, | (R7.2) |

which occurs by a chain growth mechanism to add –CH2– units:

| CO + 2H2 → –CH2– + H2O | ΔHr = −165 kJ/mol | (R7.3) |

Preferred industrial catalysts are cobalt and iron operating at temperatures between 200 and 350°C and pressures from 10–40 bar (Martín and Grossman 2011). Iron has higher WGS activity, leading to higher consumption of CO and of the produced water, which increases the H2/CO ratio, decreasing the probability for chain growth but reducing catalyst deactivation caused by water (Bukur et al. 2016). Iron catalysts also exhibit greater selectivity to unsaturated olefins because of additional surface intermediates formed. Product distributions can be modeled via a probability for chain growth, which depends on total pressure, H2:CO ratio (typically 1:1 to 2:1), the extent of WGS activity along the reactor, temperature, catalyst design, and pore structure of the support (Bukur et al. 2016).

Polymer Precursors

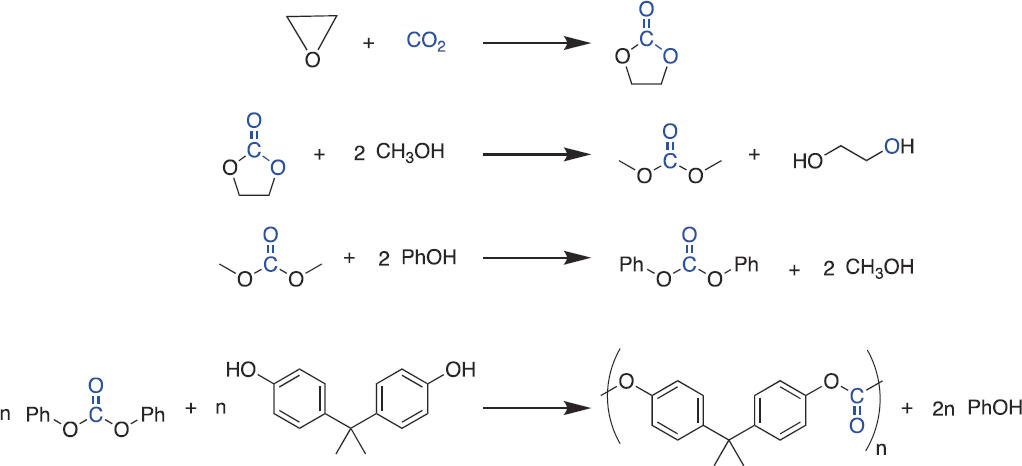

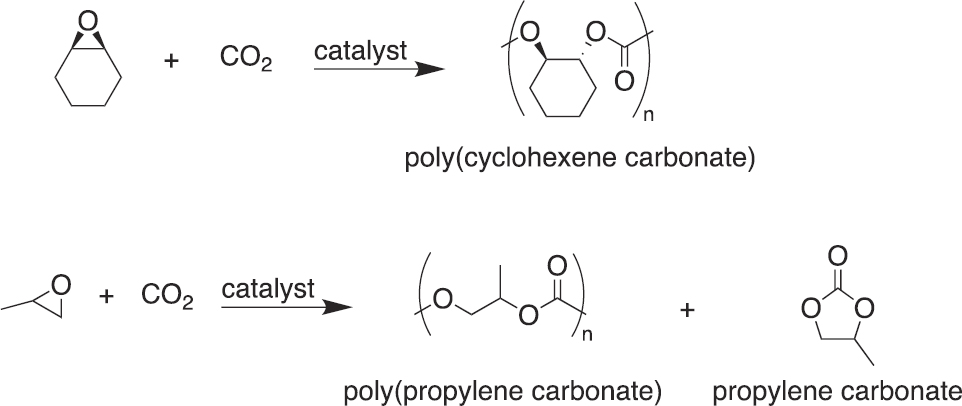

CO2 is used in the production of some monomers for polymerization reactions (Grignard et al. 2019). (Section 7.2.6 discusses direct polymerization of CO2.) For example, in 2012, Asahi Kasei Corporation industrialized a process to make bisphenol-A polycarbonate (BisA-PC) starting from ethylene oxide and CO2 (see Figure 7-5; Asahi Kasei n.d.;

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from S. Fukuoka, I. Fukawa, T. Adachi, H. Fujita, N. Sugiyama, and T. Sawa, 2019, “Industrialization and Expansion of Green Sustainable Chemical Process: A Review of Non-Phosgene Polycarbonate from CO2,” Organic Process Research & Development 23(2):145–169, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.oprd.8b00391. Copyright (2019). American Chemical Society.

Fukuoka et al. 2019). The process first reacts ethylene oxide and CO2 to make ethylene carbonate, which then reacts with methanol to produce dimethyl carbonate. Dimethyl carbonate is converted to diphenyl carbonate via reactive distillation, and last, diphenyl carbonate and bisphenol-A are reacted to produce BisA-PC. In addition to being an opportunity for CO2 utilization, the route to BisA-PC via CO2 and ethylene oxide avoids the use of phosgene and the associated safety concerns of the traditional synthesis route.

7.2.1.2 Challenges

Thermochemical CO2 conversions, like all large-scale industrial catalytic processes, are subject to continuous improvement in product yield, catalyst durability, and reactor performance (conversion per unit mass of catalyst). The near-term industry focus for thermochemical CO2 conversion is improving the RWGS reaction because all subsequent process routes utilizing syngas are proven at scale, albeit not with sustainable energy inputs and circularity constraints. The RWGS reaction is thermodynamically favorable at high temperature, but under these conditions, catalyst deactivation owing to sintering, coke formation, reduction of active species, and/or CO poisoning can be a challenge (Chen et al. 2020; Goguet et al. 2004; Tang et al. 2021; Zhou et al. 2023). Industry is exploring the noncatalytic RWGS reaction as a potentially more cost-effective option, but this approach requires higher temperature, pressure, and metallurgy for high per-pass yields to minimize the need for CO2 recycling.

The difficulty of activating CO2 makes catalyst development for RWGS—and, indeed, for all thermochemical conversions of CO2—particularly challenging. Typical copper-based RWGS catalysts are not stable at the high temperatures required for reaction, and it is difficult to achieve high CO selectivity because of undesired methanation (Chen et al. 2017). Perovskite oxides can act as oxygen donor-acceptors to minimize methanation side reactions (Chen et al. 2020). Strong metal-support interactions, structure sensitivity to dispersed metal particle size, introduction of a second metal or metal oxide, and alkali promoters all provide opportunities for commercial improvement. Supported noble metals (e.g., platinum, rhodium, palladium, gold) and first-row transition metals (e.g., copper, iron) have been examined as catalysts, but the high cost for noble metals renders them impractical. For carboxylation reactions, challenges with catalyst (and catalytic system) development include poor stereo-, regio-, and enantio-selectivity; limited mechanistic understanding; and the requirement for stoichiometric reductant, alkylation agent, strong base, and/or toxic solvent (Cauwenbergh et al. 2022; Davies et al. 2021; Tortajada et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2024).

Further catalyst development has to consider availability and sustainability of the elements chosen; thus iridium -and ruthenium-based catalysts are industrially or economically challenged. Future metal catalyst functionality from abundant materials is a goal, including use of transition-metal carbides. To this end, the use of transition-metal catalysts supported on metal oxides shows promise for RWGS, provided methane formation can be suppressed via techniques such as metal-support interactions for structure-sensitive hydrogen activation and CO2 hydrogenation reactions (Chen et al. 2020). An additional challenge will be developing catalysts that can tolerate specific CO2 feed stream compositions, including impurities. See Tables 4.3 and 4.4 in the committee’s first report (NASEM 2023) for an overview of impurities in CO2 streams from different sources (reproduced in Appendix H as Tables H-1 and H-2).

Other challenges involve reactor design and scaling of processes. The RWGS reaction exhibits a relatively low heat of reaction, and reactor design and scale up do not present significant challenges using fixed beds of catalysts with interstage cooling (Saw and Nandong 2016). Design of new gas-solid catalytic reactors with low volumetric heat transfer rates can be done from design principles without requiring demonstration. Producing fuels and other chemicals by coupling the RWGS reaction with Fischer-Tropsch or methanol synthesis requires that the high-temperature RWGS reactor outlet is cooled before sending the syngas to a Fischer-Tropsch or methanol synthesis reactor because catalysts for those reactions are not selective at high temperature. Because CO2 is difficult to activate, per pass conversions at the lower temperatures where “CO2 hydrogenation” (i.e., the forward direction of RWGS) can be coupled with Fischer-Tropsch or methanol synthesis are low, currently less than about 30 percent (Dang et al. 2019; Saeidi et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021). In such cases when CO2 conversion is below 95 percent, it has to be separated, recycled, and reheated, which reduces energy efficiency. Nonetheless, deployment to date is limited not by technology scale up, but by the lack of economic competitiveness of products derived from CO

via RWGS. Demonstrations have produced small amounts of product as a showcase (e.g., Dineen 2023). RWGS also can be performed at higher temperature via a noncatalytic thermal conversion reactor, where temperature is used to compensate for lack of catalyst. In this case, heat transfer can require larger-scale demonstration for reliable scale up. Overall heat transfer rates are not large, however, so this would be an optimization exercise and not a showstopper for industry.

Owing to the efficiency of large-scale chemical synthesis, the CO2-to-products industry of the future likely will entail large-scale plants in locations favorable to their deployment, and liquid or solid products will be shipped to market. Facilities that convert CO2 to CO and CO to products likely would need to be co-located, as it is impractical to build pipelines or other commercial transportation of CO, a toxic and reactive gas, beyond short commercial-unit trunklines. Where conditions do not favor large plants owing to water restrictions or land use or other limitations for CO2 capture and renewable power generation, distributed modular plants for integrated conversion of CO2 to CO and subsequent CO to liquid or solid products can be considered. The challenge for distributed modular processing, in competition with global mega-scale plants with low-cost shipping of products, is that capital costs and process scale do not increase at the same rate. Termed the “0.6 power rule,” capital costs for thermochemical reactions conducted in bulk equipment typically increase only at the 0.6 to 0.7 power of process scale, reflecting the fact that essential tasks for engineering design and fabrication must be performed regardless of scale, such that costs per unit of production decrease as production rates or annual capacities are increased (Timmerhaus and Peters 1991). Mini- and micro-channel reactors with improved heat transfer and membrane reactors are rare but scale closer to 1.0 power (i.e., capital costs increase proportionally to production volume), such that scale up requires “numbering up” smaller units rather than increasing the scale of a given process unit. To remain favorable despite their smaller production scale, distributed production plants have to be highly integrated, volumetrically efficient, and employ low capital expenditure approaches. Small-scale, stranded natural gas conversion facilities face similar constraints, and have generally chosen physical transport of the stranded gas as liquefied natural gas rather than reactive conversion to products on a distributed basis. Related considerations for CO2 transport versus small-scale conversion may come to the same conclusion.

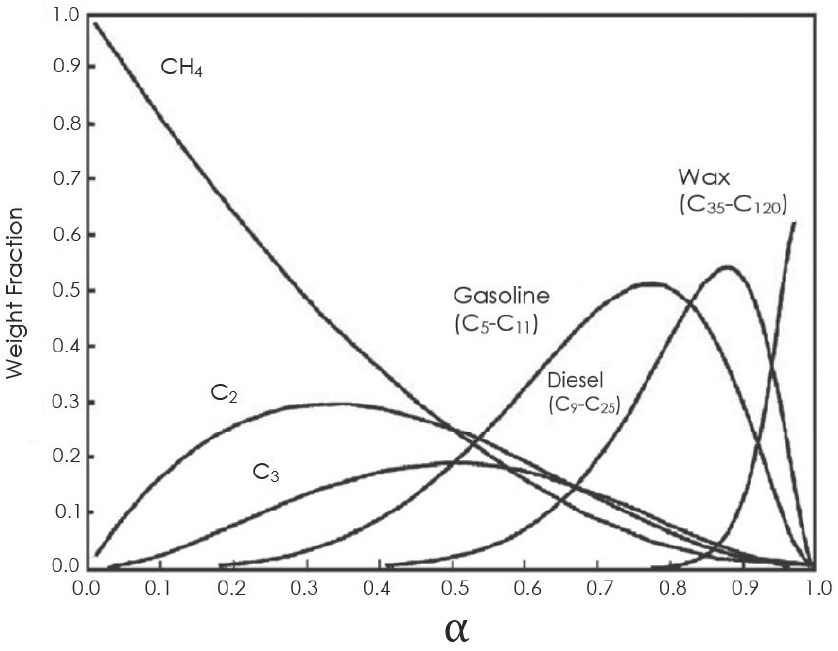

Fischer-Tropsch synthesis, the demonstrated pathway for creating a chemical economy from CO, has never been economically competitive at small or intermediate scales despite numerous showcase demonstration projects (De Klerk 2014; Dieterich et al. 2020). Fischer-Tropsch is a C1 oligomerization process, which produces an Anderson-Schulz-Flory statistical distribution of hydrocarbons with a broad range of carbon numbers, including diesel through aviation (C9+) to heavy waxes for lubricants (C35+, which can also be cracked back to smaller molecular weight), as depicted in Figure 7-6. The multiple processing steps required result in high capital expenditure and poor ability to scale down. Catalytic studies seek to reduce or eliminate the heavy end wax (lubricants) formation but also to avoid using commercially nonviable metals such as ruthenium. Additionally, olefin yields for the Fischer-Tropsch pathway have been limited to around 50 percent, compared to around 80 percent for the methanol-pathway alternative (Ye et al. 2019)—that is, CO2 hydrogenation to methanol and subsequent conversion to olefins (He et al. 2019).

Thermochemical conversion of CO2 to chemicals and fuels has higher costs than current production from fossil hydrocarbons, even for the CO2 utilization processes that are well known. Under future conditions for sustainable synthesis of circular carbon chemicals and fuels, the large amount of capital and high energy required to capture CO2 from air and upgrade it from a thermodynamically degraded state into synthetic hydrocarbons will present significant hurdles for CO2 utilization. Production of sufficient clean hydrogen to meet demand for CO2 utilization and other applications could be particularly challenging, warranting additional R&D to facilitate scale up (NPC 2024). Delivery of the low-carbon-intensity, high-temperature process heat needed for thermochemical CO2 conversion could occur via electrification (see Section 7.2.1.3 for more on electrified reactors), redesign of furnaces to support use of clean hydrogen as a fuel, or implementation of carbon capture on existing fossil fuel furnaces (see Section 10.3.2.1 for more on these retrofitting options). Decisions about the optimal approach will require consideration of trade-offs in carbon intensity and reaction efficiency. Additionally, CO2 conversion pathways, such as RWGS, that require additional heat at high temperatures in the presence of hydrogen can present challenges in reactor design and metallurgy. Given high capital intensity of capture and conversion facilities, energy storage may be required for 24/7 access to renewable H2 for conversion of CO2. Two examinations of techno-economic

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from M. Martín and I.E. Grossmann, 2011, “Process Optimization of FT-Diesel Production from Lignocellulosic Switchgrass,” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 50(23):13485–13499, https://doi.org/10.1021/ie201261t. Copyright (2011) American Chemical Society.

potential for manufacture of CO2-derived aviation fuels found prices were about 2–7 times higher than current fuels, and there was little expectation that technology innovation could overcome that barrier, so strong policy support would be needed (Freire Ordóñez et al. 2022; Soler et al. 2022). Chapter 4 discusses policy options to support CO2 utilization in a net-zero emissions future.

7.2.1.3 R&D Opportunities

R&D opportunities for thermochemical CO2 conversion include integrated catalyst development and multiscale reactor optimization, process and systems integration, use of advanced characterization and discovery techniques, and development of electrified reactors. A related R&D opportunity, integrated capture and conversion (i.e., reactive capture), is discussed in Section 7.2.5. General descriptions of each R&D area are outlined below, as many are shared across conversion pathways and product targets. Examples are provided for conversion to specific products where relevant.

Integrated Catalyst Development and Multiscale Reactor Optimization

Catalyst discovery and development for RWGS is an active topic of research for CO2 utilization, given the bifunctional nature of RWGS catalysts (metal/metal oxide), observed structure sensitivity, and relevance of surface or lattice oxygen storage in controlling the reaction pathways. For CO2 hydrogenation reactions involving zeolite catalysts, synthesis of zeolites with desired structures is a key research area for integrated bifunctional catalyst

performance, including impacts of acidity, silicon/aluminum ratio, and pore structure. Furthermore, catalysts or catalytic systems should tolerate specific CO2 feed stream compositions, including impurities. These properties also affect the subsequent conversion of methanol to gasoline or dimethyl ether (with HZSM-5 zeolite) or olefins (with SAPO molecular sieves) (Ye et al. 2019). Computational design, including use of quantum mechanical simulations (e.g., density functional theory), can identify desired structures and compositions, but multiscale modeling to consider integrated reaction and transport properties is key for defining reactor-scale performance (Ye et al. 2019). Research on Fischer-Tropsch synthesis to enhance yields of lower molecular weight olefin products has long examined iron-based catalysts (Storch et al. 1961) with promotion by potassium, manganese, or copper as dopants (Dorner et al. 2010).

The switch from traditional Fischer-Tropsch synthesis with syngas as feed to “CO2 Hydrogenation” with CO2 and H2 as feed favors iron rather than cobalt-based catalysts owing to the former’s higher WGS potential (and hence RWGS potential). Olefin yields can be increased up to four-fold with reduced methane by-product (Saeidi et al. 2021). Lin et al. (2022) describe strategies for controlling Fischer-Tropsch product selectivity, including metal particle size, strong metal-support interactions, use of alkali and other cationic promoters, use of bifunctional catalysis to couple conventional carbon chain growth via cobalt or iron metal catalysts with carbide (Co2C or Fe2C) catalysts that enable nondissociated CO insertion for higher alcohol synthesis. Dual functional cobalt-manganese (Co-Mn), iron-manganese (Fe-Mn), and zinc/chromium-oxide (Zn/Cr-oxide) catalysts can achieve olefin selectivity greater than 40 percent, although CO2 and methane formation are problematic. Two key challenges to address are (1) developing a dual functional catalyst having comparable rates for CO formation from CO2 and subsequent hydrogenation of the CO-derived intermediate and (2) mechanistic understanding of possible formate or ketene intermediate species and their impact on observed product distributions that exceed limitations of the Anderson-Schulz-Flory mechanism.

As noted above, one challenge for thermochemical CO2 activation is C−C coupling to form C2+ products. The development of tandem catalysts and better understanding of C−C coupling mechanisms could improve selectivity for CO2 conversions to long-chain hydrocarbons (Gao et al. 2020). Tandem catalysis has been demonstrated for integrated ethylene, propylene, and aromatics production from CO2 (Gao et al. 2017, 2020; Saeidi et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2019a). For example, Zhang et al. (2019a) prepared a zinc oxide/zirconium oxide (ZnO/ZrO2)-ZSM-5 tandem catalyst, with CO2 hydrogenation provided by ZnO/ZrO2 and C−C bond coupling and aromatization by H-ZSM-5. This system showed aromatic selectivity of 70 percent at 9 percent CO2 conversion and 613 K (340°C), indicating opportunities for further improvement. Detailed mechanistic modeling and catalyst characterization also can help catalyst development for production of C2+ chemicals. For example, Gao et al. (2017) developed a bifunctional In2O3/HZSM-5 catalyst with 4 nm pores that yielded 78.6 percent of C5+ liquid gasoline product from CO2 hydrogenation using a single integrated reactor, under conditions where Anderson-Schulz-Flory distribution would have limited C5+ production to less than 48 percent. More research efforts are needed to optimize catalyst compositions for tandem reactions in a single reactor and to improve reactor design for tandem processes involving multiple reactors.

Process and Systems Integration

The use of separate reaction steps—RWGS to form syngas, and then subsequent reactions of syngas to generate desired products—allows independent control of reaction conditions and catalyst formulation to achieve high yields for each step. Process intensification or integration of steps via coupling of endothermic and exothermic reactions could decrease capital costs, improve heat integration, and reduce energy use. System integration for CO formation will also be important, as CO is a stranded gas and further conversion is essential for rendering a commercial intermediate or product (González-Castaño et al. 2021). This integration will require new optimization of syngas catalysts for subsequent conversion steps, unlocking yet another era of interest in syngas catalyst optimization. For example, the endothermic RWGS reaction could be combined with exothermic methanol synthesis and further heat integrated into a methanol-to-product step (e.g., methanol to olefins). Traditional copper-zinc oxide (Cu-ZnO) catalysts for methanol synthesis from syngas are also active in WGS and hence could be considered for integrated CO2 hydrogenation to methanol (Ampelli et al. 2015). Use of small pore zeolites as supports allows a third-step integration of methanol to olefins (e.g., ethylene, propylene), although intermediate

dehydration can be a process challenge. Additional catalyst development and optimization are needed to improve kinetics and selectivity starting from CO2 rather than CO. Research is also needed on integrating catalyst design into the reaction and process system for optimization, as illustrated by González-Castaño et al. (2021) in their examination of the characteristics of copper-, cobalt-, iron-, and platinum-based catalysts for the RWGS reaction, including the impact of poisons.

Syngas generation from CO2 via RWGS could be integrated with the Fischer-Tropsch reaction pathways to provide an integrated route from CO2 to olefins or other C−C bonded products. One can use a coupled reaction sequence where the final reaction is not equilibrium constrained (e.g., methanol to olefins or fuels), to pull the reaction equilibrium constraint of RWGS and methanol synthesis to get a single reactor system that may operate at a lower temperature and obtain high conversion to fuels in a single pot. Such process intensification and integration would require integrated catalyst performance, as one cannot independently control reaction parameters for each elementary reaction step. Nonetheless, given the highly competitive nature of commercial industrial chemicals, this opportunity is driving innovative research in catalyst design and architecture for multifunctional syntheses, as well as reactor design and potential integrated separations. Research efforts are devoted to finding catalysts that improve the “CO2 hydrogenation” step and can be integrated with Fischer-Tropsch synthesis, methanol synthesis, and derivative conversion reactions to olefins or fuels so that the overall reactor can operate inexpensively at lower temperature and pressure, yet still give high per-pass yields (Gao et al. 2017; Saeidi et al. 2021). Research in catalyst and reactor design for the methanol-to-olefins process that targets incumbent distributions of olefin products would allow direct integration with existing petrochemical facilities and downstream processes, avoiding the need for extensive changes in equipment and operations.

Additional synergistic opportunities include integration of exothermic syngas reactions with high-temperature solid-oxide electrolyzer cells (SOECs) for hydrogen generation from water splitting, where thermal energy integration can improve electrical energy efficiency to near 100 percent (Hauch et al. 2020). A second synergy occurs with high-temperature solar thermochemical processes to split both CO2 and H2O to make syngas, integrated with thermal energy storage to allow 24/7 operation. More R&D is needed on thermal cycling of the working redox materials and differential thermal expansion to improve system design and durability. Given that production of net-zero fuels and chemicals requires use of atmospheric or biogenic (and not fossil point source) CO2, integrated capture and conversion of CO2 represents an essential opportunity to increase adsorption strength for low-concentration (420 ppm) atmospheric CO2, with synergistic use of chemical reactions to regenerate via conversion to preferred chemical products (see Section 7.2.5 for more detail).

Advanced Characterization and Discovery

Characterization techniques such as atomic force microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, and X-ray absorption spectroscopy provide in-depth analysis of supported nanoparticles. In addition, temporal analysis of reactors with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis to obtain reaction rate data can complement the more established in situ Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy approaches. Enhanced data acquisition combined with artificial intelligence/machine learning can provide important guidance for catalyst discovery.

Electrified Reactors

Given that low-cost, zero-emissions electricity can be produced directly from wind, solar, and other power sources (Lazard 2024), direct electrical heating of chemical reactors potentially can provide zero-carbon energy (heat) to drive the chemical conversions required for CO2 utilization. Chemicals and petroleum refining are responsible for approximately 50 percent of U.S. manufacturing CO2 emissions (EIA 2023), and the Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) industrial decarbonization roadmap highlights electrification (using zero-carbon electricity) as a key opportunity for decarbonizing these subsectors (DOE 2022). Simply replacing fossil-based electricity with clean electricity for currently electrified processes in the chemical industry could reduce the sector’s emissions by 35 percent, and further reductions are possible if additional processes (e.g., CO2 conversion) are electrified (Eryazici et al. 2021). Life cycle and techno-economic assessments of electrified reactors for syngas generation from CO2 will be critical for verifying GHG emissions reductions relative to conventional methods (Cao et al. 2022).

Catalyst options for electrically heated reactors have been investigated (Centi and Perathoner 2023). For example, Zheng et al. (2023) showed the efficacy of porous silicon carbide foams for Joule heating of RWGS catalysts at 650°C–700°C. Thor Wismann et al. (2022) examined electrically heated RWGS for methanol synthesis over a nickel-based catalyst, finding that routing the synthesis via methane formation reduced carbon deposition (coking). Dong et al. (2022) demonstrated that periodic pulsed heating can enhance selectivity to C2 hydrocarbons for methane reductive coupling, relative to steady-state operation. The “co-benefits” provided by the ability to rapidly pulse heat relative to conventional approaches with respect to concentration forcing are over and above the simpler replacement of fuel heat with low-carbon electrical energy to drive endothermic reactions. Similarly, microwave heating of catalyst particles, as demonstrated for methane conversion, may provide enhanced selectivity for endothermic CO2 reactions (i.e., RWGS) and reduce energy losses relative to bulk heating (Hunt et al. 2013). However, as opposed to direct heating via electric energy, microwave heating will suffer energy losses from conversion of electrical energy to electromagnetic radiation.

These examples show the potential for the emerging field of “electrified thermochemical” reactors (as opposed to the traditional “electrochemical” reactors) to provide new performance breakthroughs, especially for endothermic reactions such as CO2 reduction. The ability to rapidly change and control temporal and spatial heating to selectively heat catalyst surfaces versus bulk fluids, manipulate time constants for multistep reactions to improve selectivity, and reduce catalyst poisoning by operation under rapidly varying dynamic heating conditions (unlike traditional “concentration forcing” conditions), or use microwaves for selective catalyst heating provide new handles for catalyst and reaction control that are yielding promising results.

Solar thermochemical hydrogen production and solar thermochemical CO2 conversion can be readily integrated with thermal energy storage and improve the economic viability of high capital intensity processes (e.g., methanol and Fischer-Tropsch syntheses) that require 24/7 operation. R&D is needed to examine this synergy and consider its relative cost versus using solar photovoltaic energy plus battery storage to maintain 24/7 operability of Fischer-Tropsch or methanol synthesis.

7.2.2 Electrochemical Conversion Pathways

7.2.2.1 Current Technology

Significant progress has been made in developing electrocatalysts and electrochemical devices for the CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) to produce value-added chemicals, including C1 (carbon monoxide, methane, methanol, formic acid), C2 (ethylene, ethanol, acetic acid), and some C2+ (acetone, propanol, etc.) products. Low-temperature electrochemical conversion of CO2 to C1 products is occurring at the pilot scale (Grim et al. 2023; Masel et al. 2021; Xia et al. 2022), and high-temperature conversion of CO2 to CO is nearing commercialization (Hauch et al. 2020; Küngas 2020). Many studies have identified CO2RR electrocatalysts that are selective toward specific products. For example, noble metals such as silver and palladium are efficient in producing CO. First-row transition metals such as cobalt and nickel produce both CO and CH4. Main group metals such as tin, indium, and bismuth, as well as their oxides, are selective for formic acid production. A proton exchange membrane system using a lead/lead sulfate cathode was recently reported to produce formic acid with high selectivity and durability (Fang et al. 2024). At present, copper is the primary element identified that can catalyze CO2RR to C2 and C2+ products (Nitopi et al. 2019; Yan et al. 2023). Some studies have explored the possibility of enhancing the activity of copper using copper-based bimetallic alloys (Lee et al. 2018), and some have reported the production of long-chain hydrocarbons using non-copper-based catalysts (Zhou et al. 2022).

The status of theoretical simulations of electrochemical CO2RR was summarized by Xu and Carter (2019a). Modeling efforts are mostly based on density functional theory, which has difficulties describing key intermediates (CO) and electron-transfer reactions owing to errors in its electron exchange-correlation functionals. Recent work has shown that such errors can be corrected by including accurate wavefunction descriptions of exchange-correlation via embedding methods (e.g., Zhao et al. 2021). Multiscale modeling of bipolar membranes for electrochemical systems provides insights into structure–property–performance relationships that can help inform the design of CO2 electrolyzers (Bui et al. 2024).

TABLE 7-2 Electrochemical CO2RR Products with Equilibrium Potentials

| Reaction | E0 [V versus RHE] | Products |

|---|---|---|

| CO2 + 2H+ + 2e− → HCOOH(aq) | −0.12 | Formic acid |

| CO2 + 2H+ + 2e− → CO(g) + H2O | −0.10 | Carbon monoxide |

| CO2 + 6H+ + 6e− → CH3OH(aq) + H2O | 0.03 | Methanol |

| CO2 + 8H+ + 8e− → CH4(g) + 2H2O | 0.17 | Methane |

| CO2 + 4H+ + 4e− → C(s) + 2H2O | 0.21 | Graphite |

| 2CO2 + 2H+ + 2e− → (COOH)2(s) | −0.47 | Oxalic acid |

| 2CO2 + 8H+ + 8e− → CH3COOH(aq) + 2H2O | 0.11 | Acetic acid |

| 2CO2 + 10H+ + 10e− → CH3CHO(aq) + 3H2O | 0.06 | Acetaldehyde |

| 2CO2 + 12H+ + 12e− → C2H5OH(aq) + 3H2O | 0.09 | Ethanol |

| 2CO2 + 12H+ + 12e− → C2H4(g) + 4H2O | 0.08 | Ethylene |

| 2CO2 + 14H+ + 14e− → C2H6(g) + 4H2O | 0.14 | Ethane |

| 3CO2 + 16H+ + 16e− → C2H5CHO(aq) + 5H2O | 0.09 | Propionaldehyde |

| 3CO2 + 18H+ + 18e− → C3H7OH(aq) + 5H2O | 0.10 | Propanol |

NOTE: RHE = reversible hydrogen electrode.

SOURCE: Adapted from Nitopi et al. (2019).

Molecular electrocatalysts have also been studied extensively for CO2RR, with more than 100 different catalysts identified. Catalysts have been reported with 13 different transition metals, and a few examples exist of non-metal-containing catalysts (Francke et al. 2018). Although these catalysts operate under a wide variety of conditions, including organic and aqueous solvents, only a few different products have been reported. Under protic conditions, CO is the most common product, followed by formate or formic acid. Under nonprotic conditions, typical products are oxalate, CO, and carbonate (CO32−). A handful of systems have been reported that catalyze the six-electron reduction to methanol or the eight-electron reduction to methane, although some of these are not strictly homogeneous, but instead molecular catalysts immobilized onto electrode surfaces (Boutin and Robert 2021).

Among all the potential products from CO2RR, as shown in Table 7-2, CO and formic acid (HCOOH) are generally considered to be the most commercially viable molecules based on a recent review (Nitopi et al. 2019) and techno-economic assessment (Aresta et al. 2014). Conversions of CO2 to CO or HCOOH require only two electrons and are kinetically more facile than the multiple-electron and multiple bond formation-scission processes for products containing two or more carbons. Equally important, CO and HCOOH can be produced using catalysts that do not contain copper, therefore allowing the utilization and optimization of a wide range of electrocatalysts. HCOOH is a bulk chemical that can be used as a feedstock for the chemical industry and for energy storage (Aresta et al. 2014). One advantage of converting CO2 to CO is the higher efficiency of converting CO to value-added products, either through electrochemical (Jouny et al. 2019) or thermochemical (see Section 7.2.1) upgrading reactions. Converting CO2 to CO is also advantageous in terms of carbon utilization efficiency. The alkaline environment required to achieve high reaction rates for CO2RR results in large amounts of (bi)carbonate production, which has limited CO2RR selectivity for multiple carbon products (Nitopi et al. 2019). In contrast, CO2RR to CO can be carried out in a nonalkaline environment with high CO selectivity without producing (bi)carbonates. Furthermore, because CO is a gas, it is easier to separate from the electrolyte than liquid products (i.e., liquid-liquid separations are not required). The production of several C2 molecules, including ethylene (C2H4), ethanol (C2H5OH), and acetic acid (CH3COOH), has also been investigated extensively. It is widely accepted that these reactions proceed via the formation of a *CO-containing surface intermediate followed by its dimerization and subsequent reduction to form C2 products (Nitopi et al. 2019).

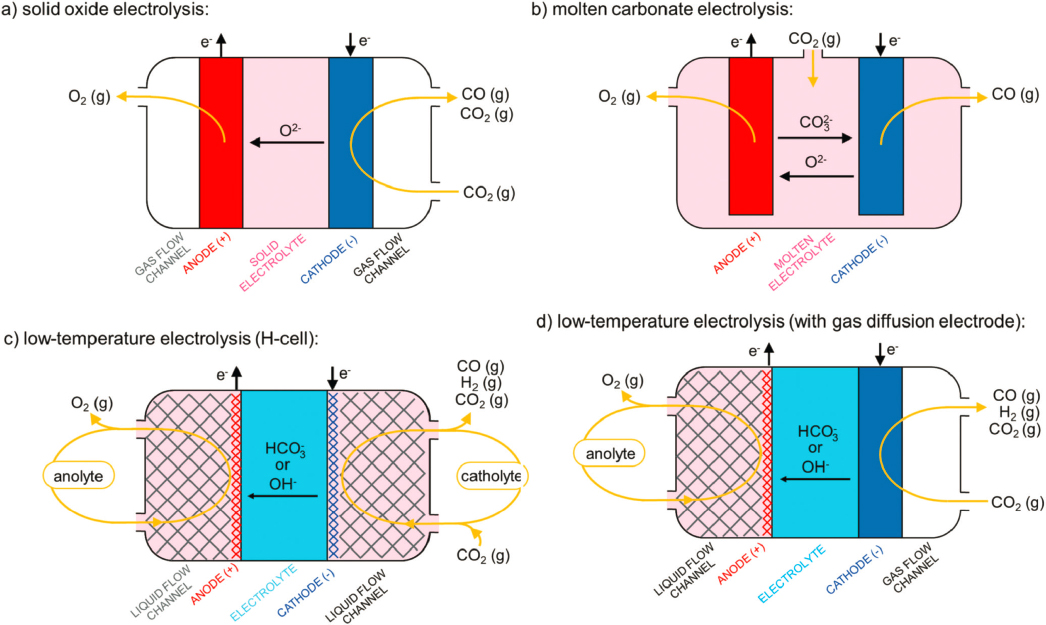

Although most current research on CO2RR focuses on low-temperature electrochemical devices, there are efforts in using intermediate-temperature (molten carbonate electrolysis) and high-temperature (solid oxide electrolysis) devices (Küngas 2020). For example, Figure 7-7 compares different electrochemical devices for CO2

SOURCE: Küngas (2020), https://doi.org/10.1149/1945-7111/ab7099. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

reduction to CO. Based on an analysis by Hauch et al. (2020) high-temperature solid oxide electrolysis of CO2 to CO is considered to be approaching commercialization with promising catalytic rates and long-term durability (Hauch et al. 2020; Küngas 2020).

Electrochemical carboxylation reactions using CO2 are also of interest as a more environmentally friendly method of producing industrially relevant carboxylic acids (Ton et al. 2024; Vanhoof et al. 2024). These reactions can involve a variety of co-substrates, including alkenes, alkynes, benzyl, aryl, and alkyl halides, and aryl aldehydes and ketones, and thus are able to form a diverse range of products. The systems often require a sacrificial anode (commonly magnesium or zinc) to provide stabilizing metal ions for the radical anion species formed during electroreduction of substrate or CO2, but there are efforts to develop sacrificial-anode-free systems through electrolyte, substrate, and cell design to reduce cost and improve sustainability.

7.2.2.2 Challenges

Although electrocatalytic CO2RR can produce several C1 products (CO, HCOOH, methanol, and methane), one critical challenge is the selective production of >2e− reduced products, and C2+ products in particular, in high yield. The energy efficiency is further complicated by the competing hydrogen evolution reaction. As noted above, at present copper is the primary element identified that can catalyze CO2RR to C2+ products with appreciable Faradaic efficiency.5

___________________

5 Faradaic efficiency is a measure of selectivity of an electrochemical reaction, calculated as a ratio of the amount of product formed over the theoretical maximum amount based on the charge passed (Kempler and Nielander 2023).

As with heterogeneous systems, homogeneous CO2RR is also challenged by product selectivity for a single carbon-based product and the competing hydrogen evolution reaction, although there are examples of catalysts with high selectivity for CO and formate (Francke et al. 2018). However, few examples exist of homogeneous electrocatalysts that reduce CO2 beyond two electrons, and none that demonstrate C-C bond coupling to form C2+ products except for oxalate (Francke et al. 2018).

Most low-temperature CO2RR studies are at an early stage of development, primarily owing to issues with long-term stability and product selectivity (Grim et al. 2023; Küngas 2020). While some progress has been made in improving these metrics, in particular through developments in gas diffusion electrodes, challenges remain in reducing overpotential and improving stability at high current densities, as well as decreasing energy losses from carbonate formation (Wakerley et al. 2022). Although high-temperature CO2RR is considered to be at higher TRL, its feasibility only has been demonstrated for CO2 conversion to CO.

Electrochemical reactors exhibit a unit scaling factor (with capacity) of near 1.0, such that one must “number up” to achieve a large scale of production. This inability to reduce costs at increasing scale has been an issue for achieving cost-effective production of H2 via water electrolysis, and likely would be for CO2 electrolysis as well. Another consideration when scaling up electrochemical CO2 conversion systems is the energy requirement compared to that of alternative tandem electrocatalysis-thermocatalysis routes, as clean electricity availability may be limited by supply chain constraints. Where electrical efficiency for direct CO2 conversion is poor (i.e., high overpotential), it may be more efficient to generate clean H2 via water electrolysis and use that H2 to form syngas, which can then be converted thermochemically to fuels and chemicals using existing technologies, as described in Section 7.2.1.1 (Eryazici et al. 2021).

7.2.2.3 R&D Opportunities

A key R&D opportunity for electrochemical CO2 conversion is to expand the number of catalysts that can generate C2+ products with relatively high yields. One approach to enhance C2+ product generation is to modify copper with an element that is efficient for CO2 to CO conversion. The resulting bimetallic electrocatalysts could effectively convert CO2 to CO, which subsequently could be converted to C2+ products by copper. The CO-rich reaction environment also should inhibit the competing hydrogen evolution reaction that would otherwise reduce the selectivity for C2+ products on pure copper. Silver and gold are attractive options because of their high CO2RR selectivity to CO and their immiscibility with copper, which prevents changes in electrocatalytic properties owing to formation of bimetallic alloys. Utilization of multiple catalysts consisting of copper and a CO-producing electrocatalyst, in the form of either physical mixtures or segmented catalyst beds, has been demonstrated for CO2 conversion to multicarbon products (Yin et al. 2022). One common practice uses one metal as a catalytically active and conductive substrate onto which the second metal is deposited. Segmented electrodes also have been studied recently to control the separation between distinct catalysts. For example, two catalysts can be deposited adjacent to each other to produce a high concentration of CO that then flows over a C2-producing catalyst (Zhang et al. 2022b). As another approach, recent efforts have explored the utilization of electrocatalytic-thermocatalytic tandem processes to produce C2+ oxygenates and hydrocarbons (Biswas et al. 2022b; Lee et al. 2023), although more studies are needed to determine whether such tandem processes can be economically competitive. Computational modeling, specifically advanced quantum mechanics methods that go beyond density functional theory (see, e.g., Martirez et al. 2021) when needed for simulating electron-transfer reactions, combined with ab-initio molecular dynamics for solvent configurational sampling (see, e.g., Martirez and Carter 2023), along with machine-learned force-field molecular dynamics (Poltavsky and Tkatchenko 2021; Unke et al. 2021; Wu et al. 2023) to sample longer time and larger sample sizes, will be the methods of choice in the future. Additional research on multiscale modeling of mass transport effects is needed to improve understanding and optimization of electrochemical device design (Stephens et al. 2022).

In molecular systems, continued work on mechanisms, modifying the electronic properties of active sites, and understanding and modifying secondary coordination sphere interactions have provided some insight into inhibiting competitive hydrogen evolution and/or steering product selectivity (Barlow and Yang 2019). Trade-offs (e.g., scaling relationships) between activity and overpotential have been identified (see, e.g., Bernatis et al. 1994; Nie and McCrory 2022). However, these scaling relations can be broken with appropriate secondary sphere effects such as

proton-relays/hydrogen-bonding interactions (Costentin et al. 2012), charge (Azcarate et al. 2016; Margarit et al. 2020), or simultaneous changes in multiple reaction parameters (Klug et al. 2018; Martin et al. 2020). Redox-active ligands also have been used to delocalize charge to access catalytic intermediates at milder potentials (Queyriaux 2021). Some of these strategies are bio-inspired by mimicking either the electronic structure or local environment of enzymes that catalyze these reactions efficiently (Shafaat and Yang 2021). Immobilizing molecular catalysts onto certain types of electrodes also appears to result in different selectivity (Boutin et al. 2019). Ligand modifications can be applied to study local environmental effects that tune selectivity or inhibit hydrogen evolution. These strategies may be translatable to heterogeneous systems (Banerjee et al. 2019).

In addition to optimizing catalysts that are selective, stable, and scalable for CO2RR, it is important to develop scalable electrochemical devices. For example, stable and cost-effective anode catalysts, which are required to complete electrochemical systems for CO2RR, need to be identified. In particular, if the oxygen evolution reaction is used as the anodic reaction under acidic conditions, the costs of the iridium oxide (IrO2) catalysts need to be considered as a potential barrier for large-scale CO2RR. Use of inexpensive, alkaline-electrolyte-based anodes for the oxygen evolution reaction, enabled by dipolar membranes, may overcome this cost barrier, but high overpotential might still be a limiting issue (Nitopi et al. 2019). Pairing CO2RR with a different anodic reaction, which may produce a more valuable product than oxygen, could also be explored (Francke et al. 2018; van den Bosch et al. 2022). The reactor components (electrodes, catalysts, supports, membrane, electrolyte) and reaction conditions (pH values of electrolytes, flow rate, temperature, pressure) also need to be optimized (Sarswat et al. 2022; Stephens et al. 2022; Wakerley et al. 2022). Continued development of semi-empirical CO2 electrolyzers models could help inform scale up beyond lab- and pilot-scale systems (Edwards et al. 2023). Furthermore, because many CO2 sources contain various potential contaminants, it is also important to evaluate the tolerance of CO2RR electrocatalysts and membranes (Nitopi et al. 2019).

For electrocarboxylation reactions, primary R&D opportunities include further development of sacrificial-anode-free systems, experimental and theoretical studies to improve mechanistic understanding and facilitate catalyst design, and improvements to enantioselectivity (Ton et al. 2024; Vanhoof et al. 2024). Focusing research efforts on the most common industrial chemicals, developing flow systems, and designing more robust electrocatalysts could facilitate eventual scale up.

7.2.3 Photochemical/Photoelectrochemical Conversion Pathways

7.2.3.1 Current Technology

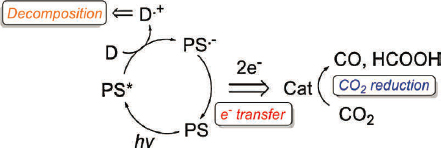

The use of light to directly drive CO2 reduction to fuels or other chemicals has been pursued via several different motifs. These include homogeneous systems that use molecular photosensitizers to absorb light (Figure 7-8) and systems that use a heterogeneous light absorber to generate the voltage required for CO2 reduction (Figure 7-9). In the latter, catalysis can occur directly at the semiconductor interface, with a heterogeneous or molecular catalyst appended to the semiconductor interface, or with molecular catalysts in solution (Kumar et al. 2012). These systems can be completely photo-driven, where no external voltage or energy source is needed, or photo-assisted, where light energy is used to provide a portion of the energy and reduce the applied voltage required to complete the chemical process.

SOURCE: Reprinted from Y. Yamazaki, H. Takeda, and O. Ishitani, 2015, “Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 Using Metal Complexes,” Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology C: Photochemistry Reviews 25:109, Copyright (2015), with permission from Elsevier.

SOURCE: Used with permission of the Royal Society of Chemistry from X. Chang, T. Wang, and J. Gong, 2016, “CO2 Photo-Reduction: Insights into CO2 Activation and Reaction on Surfaces of Photocatalysts,” Energy & Environmental Science 9(7):2177–2196, https://doi.org/10.1039/C6EE00383D; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

In addition to the metrics of Faradaic efficiency (product selectivity) and energetic efficiency (overpotential) used to evaluate electrochemical CO2 conversion, photochemical systems are also described by their photochemical quantum yield (Φ) that evaluates the efficiency in which absorbed photons generate product (Reaction 7.4; Kumar et al. 2012), where

| Φ = (moles product/absorbed photons) × (electrons needed for conversion) | (R7.4) |

Homogeneous photocatalytic systems typically have a photosensitizer, electron donor, and catalyst (Dalle et al. 2019). The photosensitizer absorbs light to generate the electron donor, which reduces the catalyst to initiate CO2 reduction. Most catalysts with activity toward electrochemical reduction (dark electrocatalysis) also have activity toward photocatalysis with an appropriate photosensitizer and donor. In some cases, the catalyst itself can serve as the photosensitizer (Das et al. 2022; Hawecker et al. 1986). The most common electron donors are aliphatic amines, NAD(P)H model compounds, ascorbate, and imidazole compounds. The choice of electron donor impacts the overall efficiency and stability of photocatalytic systems and can be involved in other reactivity (Sampaio et al. 2020). While the use of these sacrificial electron donors is common, they do not represent a sustainable method for photochemical reduction. Ideally, the electron donor would be water, but water is typically an insufficient reductant to drive CO2 reduction.

A number of strategies have been applied to improve the performance of heterogeneous photocatalytic (PC) systems for CO2 reduction. The semiconductor materials must have a suitable band gap (neither too large nor too small) to enable efficient visible light absorption while also being large enough to drive the reaction. The potential of the conductive and valence bands must be sufficient for CO2 reduction and water oxidation (Kalamaras et al. 2018; Liao and Carter 2013; Mayer 2023). Theoretical approaches to simulating (photo) electrochemical CO2RR and water splitting at the atomic scale with quantum mechanics modeling have helped elucidate the roles of the structure and composition of the electrochemical interface, absolute band edge positions relative to the redox potentials, charge carrier transport, and proton, electron, and hydride transfers (Govind Rajan et al. 2020; Liao and Carter 2013; Xu and Carter 2019b). Advancements have been made by focusing on materials architecture, which includes quantum dots, nanotubes and nanorods, two-dimensional materials, and more advanced nanostructures (Gui et al. 2021). Additionally, various dopants, sensitizers, and co-catalysts have been introduced to achieve the desired light-absorbing and catalytic properties. To prevent oxidation of the product by photogenerated holes on the photoabsorber, hole scavengers such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), sodium sulfite (Na2SO3), and alcohols are sometimes used (Chang et al. 2016). Several different photoreactors,

both batch and continuous types, also have been engineered to improve overall solar-to-product efficiencies. These reactor types are broadly categorized as slurry, fixed bed, and membrane (Khan and Tahir 2019). Key considerations include using geometry to maximize light absorption; using materials (photoabsorber/catalyst, reactor), heat exchange, mixing, and flow characteristics to maintain high contact between the reactants and catalyst; and product separation.

The most common configuration of photoelectrochemical (PEC) cells is composed of a semi-conductor photoelectrode and a counter electrode (White et al. 2015). Compared to PC systems, PEC systems may achieve higher efficiency, because electron-hole recombination is slowed by the external potential. Additionally, a greater variety of materials and configurations can be used. In most cases, CO2 reduction is accelerated using co-catalysts (Gui et al. 2021), which are often nanoparticles of metals or oxides. Molecular catalysts have also been attached onto surfaces to accelerate CO2 reduction (White et al. 2015). Other systems use solution-based co-catalysts to promote catalysis. P-type gallium phosphide (GaP) semiconductors have shown the direct photoelectrochemical reduction of CO2 to methanol with pyridinium additives (Barton Cole et al. 2010; Cohen et al. 2022; Sears and Morrison 1985; Xu and Carter 2019b; Xu et al. 2018). However, different optimal conditions, products, and yields have been reported (Costentin et al. 2018). Nanostructured electrodes have been used to enhance photocatalytic activity by engineering the band structure, increasing the surface area for catalysis, enhancing light absorption, and minimizing electron-hole recombination. Optimization of adsorbed cocatalysts may also help with selectivity and activity (Xu and Carter 2019a).

More recently, researchers have been exploring the use of localized surface plasmon resonance for light-driven CO2 reduction (Figure 7-10). This phenomenon is a result of the resonant photon-induced collective oscillation of valence electrons and is most commonly observed on nanostructured gold, silver, copper, and aluminum surfaces of nanoparticles (Robatjazi et al. 2021). Plasmonic photocatalysis can contribute to CO2 reduction by reducing the substrate (or catalyst if used) and providing local thermal heating (Verma et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2023a; Zhang

SOURCE: Hu et al. (2023), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-35860-2. CC BY 4.0.

et al. 2023). A few promising examples of plasmonic photocatalysis have been reported so far. For example, gold nanoparticles have been used to generate C1 and C2+ products from CO2 in water (Hu et al. 2023) and an ionic liquid solution (Yu and Jain 2019). Plasmonic photocatalytic systems have also been shown to accelerate the dry reforming of methane (CH4 + CO2) into syngas, although the formation of coke limits the lifetime of these catalytic systems (Cai and Hu 2019; Chen et al. 2019; Dieterich et al. 2020; Han et al. 2016; Jang et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2020).

7.2.3.2 Challenges

The direct use of light to drive CO2 reduction in photochemical processes is at a basic research stage. Integration of photochemical processes has the potential to reduce the balance of systems costs but comes with other obstacles to be competitive with a photovoltaic and electrolyzer configuration (PV-EC), which already has demonstrated a solar-to-chemical-to-energy conversion efficiency of 21.3 percent for CO production (Liu et al. 2023). Several studies have described the benefits and drawbacks of these two configurations for hydrogen production, and many details from these analyses are also applicable for CO2 reduction (Ardo et al. 2018; Grimm et al. 2020; Rothschild and Dotan 2017; Shaner et al. 2016). In these analyses, PEC devices need significant improvements to both efficiency and stability. Additional advances in device architectures and operation schemes, such as the power management and light management scheme, are also critical to improve the competitiveness of using PEC versus PV-EC systems. Like electrochemical CO2 reduction, photochemical CO2 reduction also contends with product selectivity, particularly with respect to H2 co-generation and slow kinetics for CO2 reduction.

In homogeneous systems, most photosensitizers are composed of precious metals, although recent work has focused on the use of abundant components (Ho et al. 2023; Wang et al. 2023b; Xie et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2019b). While turnover numbers are now reported in the tens of thousands (Dalle et al. 2019), systems with greater long-term stability are needed. Additionally, practical systems will need to demonstrate a catalytic cycle that does not require the use of sacrificial electron donors but instead uses water as the reductant.

Photochemical conversions traditionally have been limited by proximity and surface area contact requirements for photochemical energy. Reactors that combine high surface areas and/or deep penetration zone can overcome these limitations, as can use of high efficiency light-emitting diode arrays (essentially a new form of electrified reactor). These systems likely will have a scaling factor close to 1.0, thus requiring smaller units and numbering up to achieve large-scale production. Such designs tend to favor a modular approach that may make distributed production attractive, but which could limit the overall operating scale.