Carbon Utilization Infrastructure, Markets, and Research and Development: A Final Report (2024)

Chapter: 9 Products from Coal Waste

9

Products from Coal Waste

This chapter discusses opportunities for the beneficial repurposing of wastes generated from the coal supply chain (i.e., coal waste). It first describes the sources, compositions, and locations of coal wastes in the United States and then outlines the potential market opportunities for carbon-based products and critical minerals and materials that could be derived from coal waste. Considerations for repurposing coal waste are examined, including separations, existing and emerging applications, and product safety.

9.1 COAL WASTE COMPOSITION

In 2022, the United States consumed 513 million short tons of coal, with 92 percent dedicated to generating electricity (EIA 2023b). Of the remainder, industrial uses predominated, notably coke production, which accounted for 3.1 percent. This contrasts with the peak coal usage in 2007, when nearly 1130 million short tons of coal were used (EIA 2023b). While coal production and use are expected to continue declining in the United States over the coming years (NASEM 2024), the significant quantities of legacy waste streams contain valuable components that could be repurposed for societal benefit.

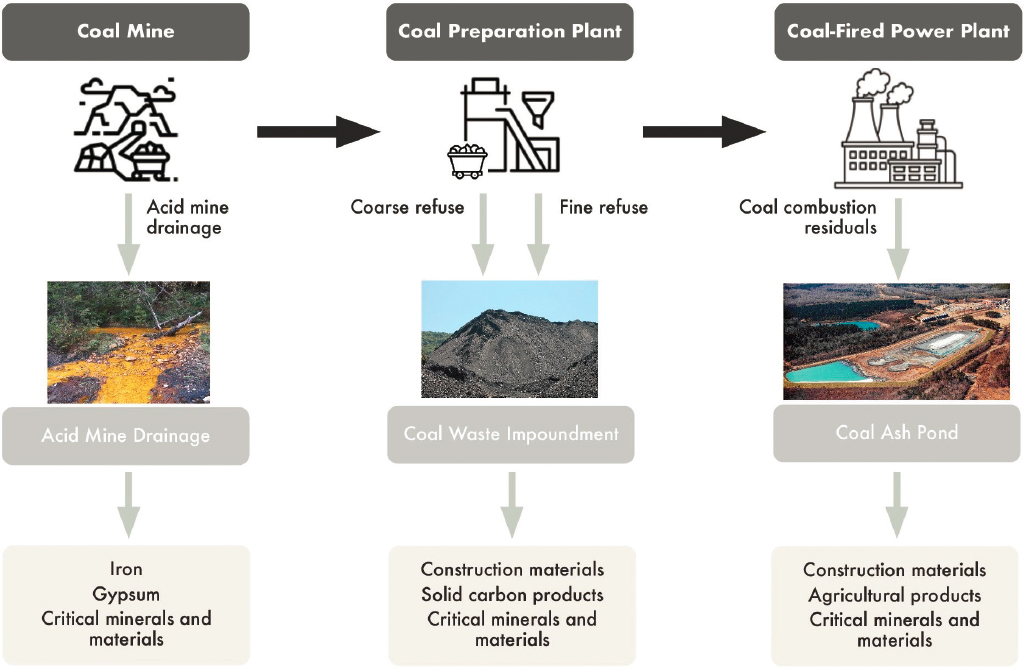

Coal waste streams considered in this chapter as potential feedstocks for carbon-based products and/or sources of critical minerals and materials include acid mine drainage (AMD), coal impoundment wastes, and coal combustion residuals (CCRs).1 As illustrated in Figure 9-1, these wastes are generated throughout the coal supply chain, from mining, to processing and preparation, to combustion at a power plant or another industrial facility. AMD is characterized by the release of acidic and metal-laden water from abandoned coal mines and is a significant environmental problem primarily associated with historical coal mining, particularly in the Appalachian region. This acidic runoff can harm aquatic ecosystems, corrode infrastructure, and contaminate drinking water sources, posing serious environmental and public health challenges. Coal impoundment waste, often referred to as coal slurry, coal refuse, or coal sludge, is a by-product generated during the processing and cleaning of coal. Impoundment waste is a mixture of water, coal fines (small particles of coal), and other substances generated during coal mining and processing activities. This waste material is typically stored in large containment structures called impoundments,

___________________

1 Mineral-dominated portions of coal beds (e.g., underclays, partings) also have been identified as potential sources of rare earth elements (Kolker et al. 2024) but are out of scope for this report.

SOURCES: Icons from the Noun Project, https://thenounproject.com. CC BY 3.0. Photos: (acid mine) Dr. Matthew Kirk, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8a/AMD_at_the_Davis_Mine.jpg, CC BY-SA 4.0; (coal waste) Jakec, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coal_waste_pile_west_of_Trevorton,_Pennsylvania_detail_5.JPG. CC BY-SA 4.0; (coal ash pond) Waterkeeper Alliance Inc., https://www.flickr.com/photos/waterkeeperalliance/13183371303/in/photostream. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

which are typically located near coal mines or coal processing facilities. Approximately 30 percent of the mined product is rejected as waste at the preparation plant (Karfakis et al. 1996), and the United States generates 70–90 million tons of impoundment waste annually (Gassenheimer and Shaynak 2023), with several billion tons stored in nearly 600 slurry impoundments across the country (Environmental Integrity Project 2019). CCRs are the byproducts generated from burning coal and its associated environmental controls primarily to produce electricity in power plants. CCRs consist of fly ash, boiler slag, and flue gas desulfurization (FGD) products and are contained in nearly 750 coal ash impoundments located across the United States (Earthjustice 2022).

9.1.1 Classification, Definitions, and Characteristics of Coal Wastes

Specific definitions and characteristics of AMD,2 impoundment waste (both coarse and fine refuse), and CCRs, including fly ash, bottom ash, boiler slag, and FGD products, are provided in Table 9-1. Each waste stream has its own unique characteristics that influence potential beneficial reuse applications.

___________________

2 Note that for this report, acid mine drainage is considered only as a potential source of critical minerals and materials.

TABLE 9-1 Coal Waste Types, Definitions, and Characteristics

| Waste Type | Definition | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Acid Mine Drainage | ||

| Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) | Acidic water with pH <6.0, discharged from mining operations and formed from the chemical reaction of surface water and subsurface water with rocks containing sulfur-bearing minerals. The sulfuric acid generated in this reaction can leach heavy metals from other rocks, yielding highly toxic wastewater.a |

|

| Impoundment Waste | ||

| Coarse Refuse | Large-particle waste product from the coal cleaning process. Typically used to construct impoundment-retaining embankments.c |

|

| Fine Refuse | Fine-grained particle waste from the coal cleaning process. Pumped via slurry and stored in impoundments. |

|

| Coal Combustion Residuals | ||

| Fly Ash | A finely ground, powdery substance primarily consisting of silica, produced through the combustion of finely pulverized coal in a boiler. Its composition may include small carbon particles, varying based on the conditions of combustion.e |

|

| Bottom Ash | A rough, sharply angled ash particle, which is too sizable to be carried into the smokestacks and thus accumulates at the base of the coal furnace.e |

|

| Waste Type | Definition | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Boiler Slag | Molten ash formed in cyclone furnaces. Forms smooth pellets flowing through slag tap at furnace bottom, glass-like appearance once cooled in water.e |

|

| Flue Gas Desulfurization (FGD) Products | A product from the process used to decrease sulfur dioxide emissions from coal-fired boilers. It can be a moist sludge made up of calcium sulfite or calcium sulfate, or a dry, powdery mix of sulfites and sulfates.e |

|

NOTES: REEs: Scandium (Sc), yttrium (Y), lanthanum (La), cerium (Ce), praseodynium (Pr), neodynium (Nd), promethium (Pm), samarium (Sm), europium (Eu), gadolinium (Gd), terbium (Tb), dysproium (Dy), holium (Ho), erbium (Er), thulium (Tm), ytterbium (Yb), lutetium (Lu). Heavy REEs: Dysprosium (Dy), terbium (Tb), erbium (Er), thulium (Tm), ytterbium (Yb), lutetium (Lu), yttrium (Y), holmium (Ho).

a EPA (2023a) and 30 CFR § 710.5.

c Luttrell and Honaker (2012).

d MSHA (2009); Rezaee and Honaker (2020).

e EPA (2023b); Luttrell and Honaker (2012).

j Ekmann (2012); Wewerka and Williams (1978).

9.1.2 Locations of Coal Wastes

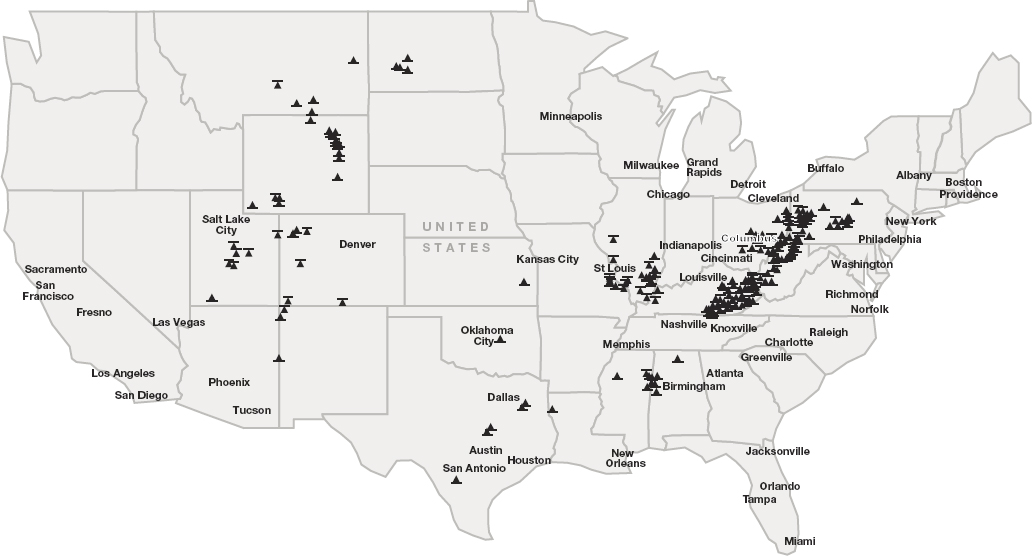

As illustrated in Figures 9-2, 9-3, and 9-4, coal wastes are located across the United States, although largely concentrated in Appalachia and the Intermountain West. Figure 9-2 shows the locations of surface and underground coal mines, thus indicating the approximate locations of impoundment wastes. Mining impoundments holding coal wastes can be categorized into three distinct states: (1) active, where they are currently in use; (2) in the process of reclamation, where restoration or rehabilitation efforts are under way; and (3) released, where erosion control, earth stabilization, topsoil replacement, and revegetation measures are complete, and the lands have been cleared from active or reclamation status. Coal wastes may also be located on abandoned mine lands. Figure 9-3 shows the locations of coal ash impoundments with color coding based on whether the ponds are regulated and/or are legacy units.3 Figure 9-4 shows locations of potential unconventional and secondary sources of critical minerals, which include coal ash ponds, coal-fired power plants, and abandoned coal mines.

___________________

3 Regulated ponds are those required by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to safely dispose of coal combustion residuals by following a set of technical and reporting criteria outlined in EPA’s 2015 rule “Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals from Electric Utilities.” Legacy units are inactive coal ash dump sites at inactive electric utilities; they are currently exempt from EPA regulation, although a proposed rule for their regulation was issued in May 2023 (Earthjustice 2023; EPA 2024b).

SOURCE: U.S. Energy Information Administration (2023b).

SOURCES: Earthjustice (2023); Basemap: (c) 2024 Google, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografia.

SOURCE: Granite et al. (2023).

9.2 MARKET OPPORTUNITIES FOR COAL WASTE–DERIVED PRODUCTS

Table 9-2 outlines existing and emerging market opportunities for all three categories of coal wastes introduced in Section 9.1. By replacing virgin materials that are extracted or harvested from the Earth, use of coal wastes can help conserve natural resources. This chapter prioritizes coal waste applications that maximize product yield and also offer improvements in properties, reductions in manufacturing costs, improvements in environmental impact, or a combination of these benefits. Additional applications such as the gasification or pyrolysis of coal waste, which could produce syngas for the manufacture of liquid fuels or chemicals, were not considered. CCRs have been used in a variety of existing market applications (ACAA n.d.). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) encourages the beneficial use of CCRs in a safe and responsible manner, as it can lead to environmental, economic, and product benefits such as reduced use of virgin resources, lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, reduced cost of CCR disposal, and improved strength and durability of materials. According to a survey conducted by the American Coal Ash Association, at least 35.2 million tons of coal ash were beneficially reused in 2021 (EPA 2024a). FGD gypsum (CaSO4) is the second most widely used coal waste, primarily in the manufacture of wall board (EPA 2014a). AMD contains rare earth elements (REEs), is a rich source of dissolved iron, and has been used to generate iron oxide for use in pigments for paints, coatings, construction materials, and inks (Riefler 2021; Riefler et al. 2023). AMD is also a potentially attractive source of critical minerals and materials (CMMs), which are crucial to U.S. energy security and reduction of GHG emissions through their use in sustainable energy technologies.

TABLE 9-2 Market Opportunities for Beneficial Coal Waste Reutilization

| Market Segment | Market Value (billion $)a | Compound Annual Growth Rate (%) | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acid Mine Drainage | |||

| Pigments (iron oxide) | 2.2b | 4.6 | Paints, cement, polymers, inks, ceramics |

| Critical minerals and materials | 325c | 8–30d | Catalysts, clean electricity, magnets, batteries, metallurgy |

| Impoundment Waste | |||

| Construction materials | 49.9e | 6.7 | Engineered composites, roofing tiles, building materials |

| Energy storage materials (graphite, graphene) | 37.9e | 14.4 | Lithium-ion battery anodes, supercapacitors |

| 3D-printing materials | 4.6e | 4.5 | Electronics, touch screens |

| Carbon fiber | 4.3e | 11.2 | Aerospace, composites, vehicles, reinforced concrete |

| Carbon foam | 0.11e | 14 | Aerospace tooling, engineered components for military applications |

| Coal Combustion Residuals | |||

| Cement | 405f | 4.3 | Buildings, roads, infrastructure |

| Concrete bricks and blocks | 370g | 6.3 | Buildings, construction, walkways |

| Asphalt | 3.8h | 5.1 | Roads, roofs |

| Drywall | 55.9i | 12.7 | Buildings |

| Critical minerals and materials | 325c | 8-30d | Catalysts, clean electricity, magnets, batteries, metallurgy |

a Total market value, not just potential market value for coal waste derived–product.

d Represents demand for lithium, nickel, cobalt, and graphite.

f Fortune Business Insights (2023a).

g Fortune Business Insights (2023b).

9.3 EXISTING MARKET APPLICATIONS AND RESEARCH, DEVELOPMENT, AND DEMONSTRATION NEEDS FOR COMMERCIAL USES OF COAL WASTES AND COAL WASTE–DERIVED MATERIALS

Existing market applications and research, development, and demonstration (RD&D) needs for commercializing coal waste utilization are presented below, including those for (1) direct solid waste utilization; (2) coal waste separations; (3) coal waste conversions to solid carbon products; and (4) CMM recovery. Figure 9-5 shows the major features of coal waste utilization to produce long-lived, solid carbon products and extract CMMs, including feedstock inputs, processes, products, and applications. Sections 9.3.3 and 9.3.4 describe these methods of coal waste utilization and the resulting products in more detail, noting relevant applications where appropriate. Safety considerations for using coal waste in commercial products also are discussed, emphasizing the necessary environmental testing, human health concerns, and product performance requirements. The Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) National Energy Technology Laboratory requires federally supported research and development (R&D) projects aiming to develop materials from coal waste to evaluate the safety and performance of these materials in accordance with their intended application (Stoffa 2023). The performance and safety of coal waste–derived products, when available, are reported in the following sections.

SOURCE: Icons from the Noun Project, https://thenounproject.com. CC BY 3.0.

9.3.1 Direct Solid Waste Utilization

This subsection provides an overview of direct reuse applications for solid coal wastes. The primary existing solid coal utilization markets include agriculture (fly ash and FGD gypsum), pavement and concrete applications, and other building product applications.

9.3.1.1 Agriculture Applications

Coal waste, in particular fly ash, has been used widely to improve soil textures in developing countries. Previous studies have shown that coal waste soil amendment could even double the crop yield in certain cases (Elseewi et al. 1980; Yunusa et al. 2012). Traditionally, it is believed that soil improvement mainly comes from the physical improvement of soil texture (Tejasvi and Kumar 2012); however, some studies have highlighted that the choices of coal waste for a particular type of soil improvement could maximize the benefits (Yunusa et al. 2012). In particular, high pH fly ash like Class C and Class can be used to modify soil acidity,4 with Class C apparently more effective owing to its high calcium oxide content (Phung et al. 1978; Yunusa et al. 2012). Besides adjusting acidity, fly ash can be used to mitigate soil salinity, and the minerals and trace elements contained in fly ash are believed to be able to enrich fertile soils (Yunusa et al. 2012). The incorporation of fly ash modified by low-temperature roasting and hydro-thermal synthesis into contaminated soils has been shown to stabilize the migration of lead and cadmium (Xu et al. 2021).

___________________

4 Fly ash classifications are based on chemical composition. Fly ash that meets the requirements of ASTM C618, which is necessary for its use in Portland cement concrete, is classified as either Class C or Class F (FHWA 2016). Class C fly ashes “are generally derived from subbituminous coals and consist primarily of calcium alumino-sulfate glass, as well as quartz, tricalcium aluminate, and free lime (CaO)” (FHWA 2017). Class F fly ashes “are typically derived from bituminous and anthracite coals and consist primarily of an alumino-silicate glass, with quartz, mullite, and magnetite also present” (FHWA 2017). A key difference between the two classes is the amount of calcium, with Class C ashes containing >20 percent CaO and Class F ashes containing <10 percent CaO.

As mentioned above, a broader agricultural application for fly ash is to ameliorate physical constraints in soils. Overall, the application of fly ash to soil improvement and agriculture depends on the type of soil and the type of fly ash. Fly ash can be used to mitigate particular types of soil property deficiencies. Fly ash does contain heavy metals (arsenic, chromium, lead, mercury, and others), and routine use in agriculture could contaminate surface and ground water and allow uptake into plants and animals (Carlson and Adriano 1991; Ishak et al. 2002; Izquierdo and Querol 2012; Kukier et al. 2003; Taylor and Schuman 1988). Previous research has shown that using FGD gypsum in agriculture can provide crops with essential nutrients and reduce the amount of phosphorus runoff into nearby water bodies. An analysis performed by EPA, the Department of Agriculture, and RTI International found that, in all scenarios evaluated, agricultural use of FGD gypsum did not lead to accumulation of inorganic constituents (e.g., arsenic, cadmium, mercury, thallium) in soil, crops, livestock, air, or groundwater at levels harmful for human or environmental health (EPA, USDA, and RTI International 2023).

9.3.1.2 Pavement and Concrete Applications

While both fly ash and bottom ash can be used for construction and pavement materials, other processing waste, like coal tailings, also can be mixed with rejuvenated asphalt for pavement (Mohanty et al. 2023). The American Coal Ash Association reports that more than half of the concrete produced in the United States today uses fly ash in some quantity as a substitute for traditional cement (ACAA Educational Foundation n.d.). The use of up to 40 percent fly ash in concrete can improve the durability, workability, and strength of concrete, while reducing the amount of required cement (Bentz et al. 2013; Bouaissi et al. 2020). Both fly ash and bottom ash can be mixed with limestone to partially replace cement in pavement materials while fulfilling the mechanical strength needs (Indian Roads Congress 2010). In certain cases, the coal waste mixtures can also improve the pavement temperature resistance (Cao et al. 2011). Utilizing fly ash for pavement projects could lead to the leaching of heavy metals into surface and groundwater, a factor that must be taken into account in engineering risk assessments (Kang et al. 2011; McCallister et al. 2002).

Sand is a primary component of concrete building materials, with an annual global consumption of nearly 50 billion tons, and current extraction rates exceed natural replenishment rates, creating an impending supply shortage (Advincula et al. 2023; UNEP 2022). Fine refuse could be used directly in a host of low-cost construction applications, such as a sand substitute in concrete applications or road base (Jahandari et al. 2023; Leininger et al. 1987). Studies of different types of coal wastes are needed to determine various optimal strategies to apply for pavement improvements (Mohanty et al. 2023) or other construction applications. Comprehensive analyses of both environmental impacts and the mechanical performance of coal waste enhanced pavement materials need to be carried out.

9.3.1.3 Other Building Product Applications

FGD gypsum is commonly used in building product applications, primarily wallboard and similar products. Almost half of all U.S. wall board is manufactured using FGD gypsum generated at coal-fired power plants (Gypsum Association 2024). According to an EPA study, the release of constituents of potential concern from FGD gypsum wallboard during use by the consumer is comparable to or lower than that from analogous non-CCR products (EPA 2014a).

9.3.2 Coal Waste Separations

Coal waste streams may require processing to separate and refine useful organic and inorganic materials, using either physical or chemical methods. This subsection reviews existing and emerging coal waste separation technologies.

9.3.2.1 Physical Methods

Fine refuse generated from coal preparation plants represents a primary feedstock opportunity for repurposing into carbon products or extracting CMMs. Fine refuse streams can contain upward of 60 wt% of coal in the form of ultrafine particles (<50 μm). Advances in ultrafine particle recovery from fine refuse are being developed,

and key technologies being considered include selective flocculation-flotation (Liang et al. 2019), hydrophobic flocculation flotation (Song and Trass 1997), carrier flotation (Ateşok et al. 2001), micro/nano-bubble flotation (Sobhy and Tao 2013), nanoparticle flotation (Li et al. 2019), oil agglomeration (Özer et al. 2017), and two-liquid flotation (Pires and Solari 1988).

Reducing air bubble size in the flotation process is effective in improving the recovery of fine coal particles. Nanobubbles (<1 μm) increase recovery of fine coal particles by preferable adherence to coal’s surface over inorganic slurry components (Fan et al. 2010). Nucleation of nanobubbles on the coal’s surface enhances its hydrophobicity, stability of bubble-particle aggregates, and increased aggregation of fine particles. Disadvantages of utilizing smaller bubbles for recovery include increased residence time for separation, increased energy consumption to generate micro/nanobubbles, and the need to use heat to dry the recovered product (Li 2019). The micro/nanobubble technology is being used to process coal refuse at 14 tons per hour for 20 hours per day at a plant in Pennsylvania (Gassenheimer and Shaynak 2023).

Recent development of a two-liquid flotation technology termed hydrophobic-hydrophilic separation (HHS) has shown promise. In the HHS process, a hydrocarbon liquid (e.g., pentane, heptane) rather than an air bubble is used to collect hydrophobic particles from aqueous slurry waste, as shown in Figure 9-6. Pilot-scale testing of the HHS process has demonstrated effective recovery of fine coal from a range of Appalachian fine refuse streams consisting of upward of 67.5 wt% inorganic content, resulting in ultrafine coal product streams with <1.0 wt% inorganic content and >99 percent liquid hydrocarbon recovery for reuse (Yoon et al. 2022). The first commercial-scale installation using HHS technology is in the commissioning phase at a plant in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, which can process up to 20 tons of coal per hour (Troutman 2023).

SOURCE: Yoon et al. (2022).

9.3.2.2 Chemical Methods

The majority of coal waste separation is performed using physical methods, and only a few methods for chemical separations have been described. Tailings often require dewatering to separate the solid and liquid phases, but the presence of fine clays makes traditional filtration challenging. One approach uses chemical additives to facilitate this dewatering step. Coal tailings often are composed primarily of clay minerals such as kaolinite and montmorillonite, which have negative surface charges that inhibit their settlement during physical separation methods. Various inorganic salts with cations such as Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and Al3+ neutralize these surface charges and facilitate agglomeration through centrifugation, with Al3+ having the greatest efficacy (Nguyen et al. 2021). Another approach uses oil and water phases to induce HHS in coal gasification fine slag. This method provides enrichment of carbon products compared to inorganic elements, which contain silicates and metals. (Xue et al. 2022). Nanofiltration and reverse osmosis membranes have been proposed to purify acid mine wastewater; they could potentially generate concentrated brine streams for further processing and purified water, thereby dewatering such streams (Ighalo et al. 2022; Xia et al. 2023).

9.3.3 Waste Coal Utilization

The separations described in Section 9.3.2 produce a waste coal product with low ash content, which can be converted into a variety of carbon-containing products using methods that directly or indirectly utilize waste coal. This subsection provides an overview of ongoing R&D focused on repurposing the carbon fraction (i.e., waste coal) of coal waste into solid carbon products. Because information on the use of waste coal is limited to date, several products that have been obtained from coal are discussed for illustrative purposes, as similar methods could be developed for using waste coal as the starting feedstock. Product categories include construction materials, energy storage materials, carbon fiber, carbon foam, and three-dimensional (3D) printing applications. With DOE support, technologies spanning several areas are being developed that convert coal or waste coal into value-added solid products (Stoffa 2022).

9.3.3.1 Construction Materials

The mass of construction materials used in the global built environment to date, estimated at approximately 1.1 teratonnes, is equal to living biomass on Earth (Elhacham et al. 2020). Construction material demand has been roughly doubling every 20 years over the past century and is expected to continue increasing (Elhacham et al. 2020), providing market growth opportunities for inclusion of new construction materials and feedstocks. Long-lived construction materials offer a significant beneficial utilization opportunity, as they sequester the carbon content of waste coal. Emerging research, detailed below, has been analyzing the use of coal or coal waste in construction materials, primarily as filler in engineered composites for construction applications (e.g., blocks, decking, piping). Coal has been introduced to a wide range of composite materials consisting of thermoplastic, thermoset, ceramic, and fiber-reinforced cement composites.

Coal-based bricks and blocks (CBBs), made from composites composed of coal mixed with thermoplastic resin, offer an alternative to traditional clay materials. CBB materials containing up to 70 wt% coal have been investigated, with cross-linked high-density polyethylene and polyvinyl chloride materials exceeding the 5000-psi compressive strength code requirement (Vander Wal and Heim 2023). CBBs made with thermosetting epoxies have been shown to possess compressive strengths exceeding 5,000 psi (Vander Wal and Heim 2023). The manufacture of thermoplastic and thermoset based CBBs will have very limited to no CO2 from waste coal content. Thermoplastic- and thermoset-based CBBs that utilize mined coal are currently at a bench-scale level of development. Further R&D is needed to incorporate waste coal, scale up manufacturing processes, and perform necessary building code testing. Coal-derived chars, generated via pyrolysis at 850°C, also have been studied for use in CBB applications, with materials containing 40 wt% char content possessing higher compressive strength (49.5–52.5 MPa) than conventional clay bricks (10–20 MPa). Char-based CBBs also possess lower density and water absorption (Yu et al. 2023). In addition, CBBs have been made from pyrolyzing pressed mixtures of coal

and preceramic polymer resin (PCR) at temperatures of 180°C (plastic/ceramic bricks) or 1000°C (ceramic bricks) (Sherwood 2022b). The coal-PCR bricks and blocks exhibit compressive strength (4465 and 4863 psi, respectively) and density (1.57 and 1.55 g/cm3, respectively) advantages over conventional brick and block materials (2845 and 4400 psi, respectively, and 2.3 g/cm3 [block]) (Sherwood 2022b).

Pyrolysis processing will generally retain approximately 60 wt% of coal’s carbon content when generating char (Chen et al. 2006; Seo et al. 2011), with the remaining carbon forming carbon oxides and condensable and noncondensable hydrocarbons; similar emissions are anticipated from pyrolysis processing of waste coals. Pyrolyzed coal-PCR composites also have been evaluated for façade and roofing tile applications. PC-PCR roofing tiles possess flexural strength of 3317 psi with 35 percent lower weight than clay roofing tiles and passed ASTM specifications for hail impact, water absorption, and flexural strength (Sherwood 2022a). In addition, testing of a composite material made from phenolic resin and coal char derived from pyrolyzed subbituminous coal indicates the material has significant potential for load-bearing building applications (Wang et al. 2023). Additional R&D is required to determine whether coal-char can be produced from waste coal and its performance in such applications. Carbon aggregate made via flash Joule heating (FJH) of coal-derived metallurgical coke has been tested as a replacement for sand in concrete applications. The replacement of sand with FJH-derived carbon aggregate reduced concrete density by 25 percent while increasing toughness, peak strain, and specific compressive strength by 32 percent, 33 percent, and 21 percent, respectively (Advincula et al. 2023).

Composite decking materials developed from high-density polyethylene with coal and waste coal have reached an advanced stage (technology readiness level [TRL] 8). These coal-based decking boards meet ASTM specifications and with projected pricing equivalent or lower than typical wood-plastic composites when manufactured at scale (Al-Majali et al. 2023b). Coal plastic composites (CPCs) also potentially offer greater resistance to oxidation (typically associated with product service life) than commercial wood-plastic composites without antioxidant additives owing to the primary and secondary antioxidant components of coal (Al-Majali et al. 2022). A recent analysis, using finite element analysis modeling with material properties for CPCs made with bituminous waste coal recovered from an active impoundment, suggested that decking boards made with CPC should meet building code requirements (Al-Majali et al. 2023a). Commercially manufactured CPC product has been demonstrated to meet ASTM D7032 specifications for composite decking, including passing respirable dust (NIOSH 600), leaching (EPA 1311), and fire rating (ASTM E84, Class B) tests (Al-Majali et al. 2023b). Preliminary life cycle assessments (LCAs) indicate that coal-based composite decking has less embodied energy and emissions than its wood-plastic counterparts (Al-Majali et al. 2019). CPC materials also offer opportunities to incorporate significant recycled plastic content, similar to currently offered commercial composite building products (AZEK 2024; MoistureShield, Inc. 2022; Trex 2024). Furthermore, thermoplastic composites made from polyvinyl chloride and waste coal have been evaluated for drainage and vent pipe applications. These composites were shown to meet ASTM D1784 specifications for piping compounds, and 2-inch schedule 40 pipe has been successfully manufactured (Trembly et al. 2023a).

9.3.3.2 Energy Storage Materials

Carbon materials for energy storage applications are categorized into two main categories, graphitizable soft carbons and nongraphitizable hard carbons. Two primary soft carbon materials being targeted from waste coal are graphite and graphene, with graphite further categorized as flake or amorphous. Flake graphite is primarily used in batteries, foundries, refractory materials, and lubricants. Amorphous graphite is used in foundries, refractories, recarburization processes, and lubricants. The United States does not produce natural graphite, relying on imports from China (33 percent), Mexico (18 percent), Canada (17 percent), Madagascar (10 percent), and others (22 percent) (percentages for 2018–2021; USGS 2023), which creates an energy security risk for the U.S. electric vehicle market—the primary factor increasing graphite demand. Production of lithium-ion battery (LIB)-grade graphite is an attractive option for waste coal. Spherical graphite is the preferred shape for many commercial battery applications because spherical particles pack well, leading to high tap density, which can increase the overall energy density of the battery, and because the spherical shape has a shorter diffusion path for lithium ions, which can enhance charging/discharging rates.

Traditionally, synthetic graphite is manufactured by treating a carbon precursor at high temperature (up to 3000°C) over a long time. A portion of the synthetic graphite supply chain is manufactured from mesophase pitch, a collection of aromatic hydrocarbons that exhibit optical anisotropy. While the majority of mesophase pitch is derived from petroleum processing, the carbonaceous precursor also can be synthesized from coal tar pitch, a by-product of coke production. Mesophase pitch with a significant amount of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and polynuclear aromatic structural units has the potential to be used as a precursor for producing soft carbon material with a high degree of graphitization (Zhang et al. 2022a). Recent research has demonstrated the synthesis of mesocarbon microbeads at 2350°C from coal-derived mesophase pitch, with good performance in LIB coin cells (Prakash et al. 2022). Another study showed that a low-temperature solvothermal preparation method can produce carbonaceous mesophase materials at 230°C with promising electrochemical properties, offering a less energy-intensive preparation method (Wu et al. 2023).

Direct preparation of graphite via thermal treatment of highly volatile bituminous and anthracite coals from 2000–2800°C has been reported, but LIB performance data to assess commercial viability is limited (Han et al. 2021; Shi et al. 2021; Xing et al. 2018). Similar preparation methods could be applied to waste coal. To assess maximum performance potential, waste coal-derived graphite intended for LIB applications would have to undergo spheroidization and amorphous carbon coating before testing. Processes that use high temperature to synthesize graphite or related carbon materials, in particular, will require LCA to analyze process GHG emissions. (See Chapter 3 for more detail on LCA.) Another method involving the thermal treatment of lignite up to 3000°C after mineral acid treatment has been explored; subsequent LIB tests suggest the resulting soft graphitizable carbon is not suitable for electric vehicle applications (Azenkeng 2022). A bituminous coal graphitized at 2850°C was compared to synthetic commercial graphite possessing a higher d-spacing5 (3.396±0.001 Å versus 3.389±0.006 Å), lower ID:IG66 ratio (0.78 versus 0.97), lower degree of graphitization (51±1 percent versus 60±7 percent), and higher surface area (7.34±0.29 m2/g versus 1.35±0.06 m2/g) (Paul et al. 2023, 2024). The bituminous coal graphite and commercial graphite were evaluated in LIB half-cells demonstrating capacities of 270±4 mAh·g−1 for coal graphite (theoretical capacity is 372 mAh·g–1) and 329±7 mAh·g–1 for commercial material and coulombic efficiencies of 99.19±0.24 percent for coal graphite and 99.51±1.49 percent for commercial material (Paul et al. 2024). The bituminous coal graphite was not spheroidized or coated with amorphous carbon, typical battery-grade graphite processing techniques. Novel synthetic graphite preparation methods from coal and waste coal include laser irradiation and molten salt synthesis. Graphite derived from lignite through laser irradiation has been studied (Banek et al. 2018), but the material did not attain the performance metrics of commercial graphite (Wagner 2022). Highly crystalline nano-graphite has been synthesized via molten calcium/magnesium chloride-assisted electrocatalytic graphitization of coal chars (Thapaliya et al. 2021). Related work on beneficial reuse of coal for LIBs evaluates the use of silicon oxycarbide (SiOC) polymer-derived ceramic with 25 wt% bituminous coal as an anode material and reports a specific capacity of about 700 mAh/g in coin half cells (Marcus 2022).

In addition to energy storage, graphite has many additional industrial applications that are possible opportunities for waste coal reutilization. Graphite electrodes are used in the production of steel, aluminum, and silicon (Jäger and Frohs 2021). Other applications include high-temperature refractories, lubricants, conductivity additives, gaskets, fire extinguishing agents, and lubrication of industrial manufacturing and machining processes (Al-Samarai et al. 2020; Chung 1987; Jäger and Frohs 2021).

Recent studies have reported the use of ab initio molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate the formation of amorphous graphite and carbon nanotubes from carbonaceous material such as waste coal (Thapa et al. 2022; Ugwumadu et al. 2023). Atomic-scale modeling via—for example, molecular dynamics or kinetic Monte Carlo simulations are useful tools for fundamental research, offering the potential to enhance understanding of complex carbon chemistry involved in transforming waste coal structures into useful carbon products.

Graphene is a soft carbon nanomaterial that can be manufactured from waste coal. Applications of graphene are extensive and include energy storage, ultraconductors, composites, separations, biomedical, and electronics. Various direct and indirect methods for producing graphene from coal have been investigated, such as exfoliation (Leandro et al. 2021; Yan et al. 2020), chemical vapor deposition (Vijapur et al. 2017), electric arc (plasma)

___________________

5 D-spacing is a measure of the distance between parallel planes of atoms in a crystal structure.

6 ID:IG is the ratio of the intensity of D to G peaks in Raman spectroscopy.

(Awasthi et al. 2015), and flash Joule heating (Du et al. 2023; Tour 2022). Carbon quantum dots have also been prepared from coal and coal-derived materials using electrochemical exfoliation (He et al. 2018), chemical oxidation (Ye et al. 2015), plasma arc discharge (Xu et al. 2004), hydrothermal (Fei et al. 2014), and laser ablation (Kumar Thiyagarajan et al. 2016) synthesis methods. Carbon nanotubes also can be synthesized from coal or waste coal utilizing arc plasma jet (Tian et al. 2004), arc discharge (Awasthi et al. 2015), laser ablation (Kumar Thiyagarajan et al. 2016), chemical vapor deposition (Tian et al. 2004), or chemical pyrolysis (Moothi et al. 2015) methods. Most methods for producing graphene from waste coal are energy-intensive (thermal, plasma, arc discharge, and laser ablation) or require energy processing agents with high embodied energy (exfoliation). Electrochemical methods operating at near ambient temperature are attractive if supplied by renewable energy. Research that focuses on reducing the energy intensity of graphene synthesis from waste coal is needed and will require LCA to analyze process GHG emissions.

Hard carbon, which can be produced from both mined and waste coal, serves various applications such as sodium-ion batteries, potassium-ion batteries, catalyst supports (Lu et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020a; Xiao et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2011), and adsorption media. Manufacture of soft carbons requires a precursor with a high aromatic content (i.e., coal tar pitch; Alvira et al. 2022) and processing temperature (2200°C–3000°C; Marsh and Rodríguez-Reinoso 2006), making nonfusing coal or waste coals better suited precursors for hard carbon manufacturing at lower temperatures (1000°C–1800°C; Marsh 1989). Sodium-ion batteries are an attractive alternative to LIB technology, owing to sodium’s greater abundance and lower cost (Abraham 2020). Studies have shown that hard carbon derived from pyrolyzed samples of anthracite, subbituminous, and bituminous coal possess energy storage capacities of 252 (Wang et al. 2020b), 291 (Lu et al. 2019), and 270 (Kong et al. 2022) mAh·g–1, respectively. These values are within the range of 250 to 350 mAh·g–1 reported in literature for hard carbons from various sources (Kong et al. 2022; Liu et al. 2022; Lu et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020b). Additionally, activated carbons made from all types of coal are commercially produced and used in the purification of water, air, chemicals, and food, among other applications (Carbon Activated Corporation 2024). Hard carbon applications are an attractive option for waste coal utilization owing to less stringent aromatic content requirements.

9.3.3.3 Carbon Fiber

Carbon fiber is a high-strength, lightweight material composed of polycrystalline carbon atoms largely aligned parallel to the long axis of the fiber, which results in a corrosion-resistant high tensile strength material. Carbon fiber is used in advanced materials as a reinforcing material in composite structures, including carbon fiber reinforced polymers and carbon-carbon composites. Current applications of carbon fiber reinforced polymers span many sectors, including aviation (they make up 80 percent by volume of the Boeing 787; Giurgiutiu 2022), automotive, energy, infrastructure, marine, and electronics (Belarbi et al. 2016).

More than 95 percent of carbon fiber is prepared from polyacrylonitrile (Grand View Research 2022), but carbon fiber also can be manufactured using mesophase pitch derived from petroleum or coal resources. Automotive industry recommendations for carbon fiber for car frames are that the tensile strength, elongation ratio, and Young’s modulus be at least 1.7 GPa, 1.5 percent, and 170 GPa, respectively, at a cost of less than $11 per kg (Yang et al. 2014). Although polyacrylonitrile-based carbon fibers exceed the mechanical performance requirements, their cost (>$20/kg) inhibits their adoption, so alternative carbon fiber preparation methods are needed. Das and Nagapurkar (2021) conducted LCA and technoeconomic assessment (TEA) to compare carbon fiber production from polyacrylonitrile with that from coal pitch derived from mined coal. The embodied energy for coal pitch carbon fiber manufacturing was estimated to be 2.4–2.5 times lower than that for polyacrylonitrile carbon fiber manufacturing, estimated at 1188 MJ/kg. The LCA considered nine environmental impact categories, indicating that coal pitch fiber manufacturing would result in lower emissions across all categories owing to higher manufacturing yield, generally producing less than 50 percent of the emissions of the conventional polyacrylonitrile carbon fiber process. TEA estimates for a 3750 tonne/year carbon fiber manufacturing facility indicated costs of $10.29/kg for coal pitch sourcing, compared to $18/kg to $22/kg for polyacrylonitrile sourcing.

Owing to the low costs of coal and waste coal, and the higher conversion yield associated with coal pitch carbon fiber manufacturing, their use as feedstocks for carbon fiber production could provide value to this market if mechanical performance requirements can be achieved. Carbon fiber manufacturing and performance are highly

susceptible to impurities in coal pitch, such as quinoline insolubles and ash, which create stress points and lead to breakage (Banerjee et al. 2021a; Cao et al. 2012). It is essential to understand the impurities introduced during coal pitch manufacturing when using reclaimed coal as feedstock. Recent research has shown that carbon fiber made from mesophase pitch derived from coal fractionation product possesses tensile strength of 1.8 and 3.0 GPa, elongation of 1.4 percent and 0.7 percent, and Young’s moduli of 140 and 450 GPa, after carbonization at 1000°C for 30 minutes and graphitization at 2800°C for 10 minutes, respectively (Shimanoe et al. 2020). Another study reported a tensile strength of 3.86 GPa, elongation of 0.62 percent, and Young’s modulus of 620 GPa (Guo et al. 2020). These results indicate that the elongation ratio of coal mesophase pitch carbon fiber needs to be improved to meet industry standards, but the standards for tensile strength and Young’s moduli have been achieved. Encouragingly, isotropic pitch-based carbon fibers derived from waste coal have been shown recently to possess mechanical properties similar to those of general-purpose carbon fibers (Craddock et al. 2024).

9.3.3.4 Carbon Foam

Carbon foam is a low-density, porous material made predominantly of carbon. It has unique tunable properties including strength and conductivity (both electrical and thermal), with high temperature resistance and chemical inertness. Although commercially manufactured, carbon foam is still an emerging material owing to its cost. Applications for carbon foam include tooling to produce carbon fiber composites, thermal insulation, fireproofing, aerospace, heat sinks and exchangers, electrodes, electromagnetic interference shielding, acoustic insulation, energy absorption, and contaminant adsorption.

Carbon foam currently is made from three primary sources: phenolic resin, petroleum-derived pitch or coal-derived pitch, and caking coals. The foaming process involves controlled heating of the precursors (pitch or coal) (up to 500°C) under pressure (up to 3.5 MPa) in an inert atmosphere to form an amorphous carbon (Chen et al. 2006). Further thermal treatment of the amorphous product is completed to control product properties, up to graphitization. During heating, the evolving volatiles from the decomposing light fractions serve as bubble agents to create a foam cell in the highly viscous precursor material. Further heating results in solidification of the precursor, which fixes the foam matrix (Calvo et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2006). Waste coal can serve as a direct or indirect precursor for carbon foam synthesis. Carbon foam products directly synthesized from coal with varying density (20–30 lb/ft3) are commercially available (CFOAM LLC n.d.(a)). Cost is the primary hindrance to adoption of carbon foam for use in commodity applications such as construction and building products, which is associated with the high-pressure batch nature of current commercial manufacturing methods.7 Unique market opportunities that warrant carbon foam’s price premium include tooling and defense applications owing to its unique thermal and physical properties, such as high thermal stability, resistance to melting, and low coefficient of thermal expansion (CFOAM LLC n.d.(b)). As volumes increase in more successful applications, opportunities will arise for cost reductions through automation and process improvements. Recent research has focused on developing methods to synthesize carbon foam continuously, to perform the foaming step at atmospheric pressure, or both. Carbon foams made from strongly caking coals in a batch-wise process at atmospheric pressure possess compressive strengths of 2.7–18.1 MPa (Yang et al. 2022), compared to 6.0–16.0 MPa for commercially available carbon foams (CFOAM LLC n.d.(c)). Continuous production of carbon foam panels using a continuous atmospheric belt kiln has recently been demonstrated, with products possessing densities of 25–32 lb/ft3 and compressive strength of 9.6 to 16.5 MPa (Olson 2022).

Façades made from waste-coal-derived carbon foam and carbon-foam-enhanced fiber-reinforced cement composites also have been demonstrated. Carbon foam materials with a density of 35 lb/ft3 were shown to meet ASTM C1186 Grade I specifications, while carbon foam (27 lb/ft3) with backing material exceeded ASTM C1186 Grade II specifications (Trembly et al. 2023b). Fiber-reinforced cement composites made by replacing sand filler with carbon foam particulate demonstrated equivalent strength as a conventionally prepared fiber-reinforced cement composite control, with up to 30 percent lower density (Trembly et al. 2023b).

___________________

7 Dr. Rudolph Olson, personal communication with the committee.

9.3.3.5 3D Printing

Additive manufacturing, or 3D printing, is an emerging technique with industrial applications already developed. Fused deposition modeling (FDM) and fused granulate fabrication are the most widely used 3D printing techniques, involving the extrusion of a thermoplastic filament or pellet to deposit material layer by layer. Commercial FDM applications include prototyping, tooling and jigs, furniture, automotive components, parts (e.g., gears, bumpers, valves, covers), and architecture.

Anthracite and lignite have been incorporated in polyamide-12 (PA 12) resin to form a composite and printed using the FDM procedure. The addition of lignite improved Young’s modulus and thermal conductivity compared to unmodified PA 12 (Veley et al. 2023a, 2023b). The incorporation of bituminous coal into polylactic acid, polyethylene terephthalate glycol, high-density polyethylene, and PA 12 resulted in FDM filaments with similar glass and melt transition temperatures, lower heat capacity and thermal conductivity, and, notably, a reduced thermal expansion coefficient for high-density polyethylene (Veley et al. 2023a). PA 12 filaments made with waste coal demonstrated greater maximum tensile and flexural strengths than unfilled plastic, likely owing to beneficial hydrogen bonding between the waste coal filler and the matrix (Veley et al. 2023b). DOE has active projects investigating the use of waste coal in 3D printing applications (DOE-FECM 2021). The addition of fly ash to cement-based 3D printing formulations improved flowability (Yu et al. 2021). Coal waste, produced from both mining and combustion processes, holds potential for use in 3D printing applications. Further research is essential to assess the performance and safety of additive manufacturing materials developed using coal waste.

9.3.4 Critical Minerals and Materials Recovery

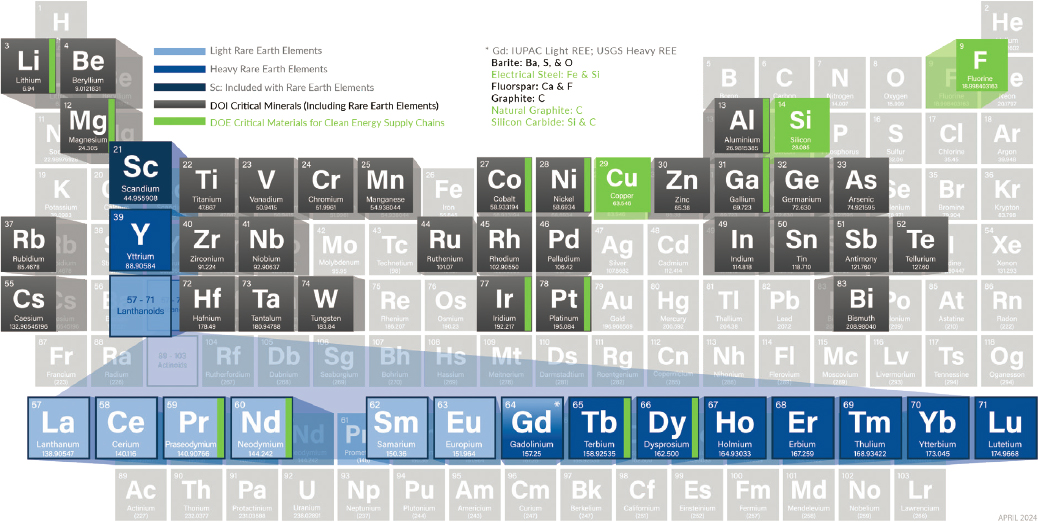

Currently, the United States imports most minerals deemed “critical” by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS; see Figure 9-7), which can lead to supply chain vulnerabilities. In 2022, imports comprised over 50 percent of the demand for 43 critical minerals, with 12 of those being 100 percent imported (USGS 2023). Coal has diverse and

SOURCE: NETL (n.d.).

TABLE 9-3 Advantages and Disadvantages of REE Extraction from Different Coal Wastes

| Coal Waste Type | REE Recovery | |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| Acid mine drainage | REEs that exist as precipitates are near 300 ppm concentration (DOE interest level). | REEs that exist in solution are at much lower concentration than those in coal-related solids; geographically limited to areas with past mining. |

| Impoundment waste | Relative enrichment in REEs and lithophile elements (e.g., Li, Al, Ti, Sc, Rb, Y, Zr, Cs, Ba) compared to raw coal. | Enriched in harmful chalcophile elements (e.g., Hg, As, Sb, Pb). |

| Fly ash | Highest REE enrichment of coal sources because REEs strongly retained in smaller mass. | Difficult to extract the significant fraction of REEs contained in aluminosilicate glasses. |

SOURCE: Based on data from Kolker (2023).

complex chemistry, containing all the elements existing in nature, and coal wastes contain vast amounts of critical minerals (CMs), including REEs (Kolker 2023; Kolker et al. 2024; McNulty et al. 2022). Thus, increasing attention is being paid to the development of potential methods for recovering CMs, including REEs from coal wastes. Table 9-2 above provides market information on critical materials from coal wastes. This section reviews R&D on extraction of REEs, typically in the form of rare earth oxides (REOs), from coal wastes and discusses research on the extraction of two other CMs, lithium and nickel. The chapter does not discuss the subsequent separation of individual REEs from REOs, which is a distinct separations issue not affected considerably by the characteristics of coal wastes.

REEs can be found in solid and liquid coal wastes. Solid coal wastes containing REEs include impoundment refuse and CCRs. Recovery of REEs from solid coal wastes requires dissolving REOs via a leaching process into an extractable aqueous phase. AMD, a liquid coal waste stream, offers potentially direct extraction opportunities when containing a sufficient REE concentration. REEs in coal wastes can be recovered by combining physical beneficiation and subsequent hydrometallurgical processes. Table 9-3 presents advantages and disadvantages of different coal waste types with respect to REE extraction. Physical beneficiation methods, including gravity, magnetic, and flotation separations, are used to enrich the concentrations of REEs in solid coal wastes to obtain REE-preconcentrated solid coal wastes as a feedstock for the next process—hydrometallurgical treatment (see, e.g., Eterigho-Ikelegbe et al. 2021; Fu et al. 2022; Mwewa et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2020a). Physical beneficiation reduces the amount of unburned carbon (that would consume chemicals used during hydrometallurgical treatment), magnetic materials that typically contain fewer REEs than nonmagnetic fractions, and large-size particles that lower the leaching efficiency in hydrometallurgical processing.

Hydrometallurgical processes are used to obtain high-purity CM mixtures from REE-enriched solid coal wastes or preconcentrates (see, e.g., Dodbiba and Fujita 2023; Eterigho-Ikelegbe et al. 2021; Fu et al. 2022; Mwewa et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2020a). Typically, leaching is the first step in hydrometallurgical processes, followed by various extraction and precipitation steps. To increase leaching efficiency, a pretreatment of roasting preconcentrates obtained with chemicals, such as Na2CO3, is first completed. Alternatively, mixing with sodium hydroxide (NaOH) or other strong alkalis decomposes the glassy aluminum-silicate matrix to form soluble species—for example, H2Si2O62− and Al(OH)4−, thereby liberating the REEs captured in the glassy matrix. REOs or rare earth hydroxides (RE(OH)3), are subsequently generated via precipitation.

Membrane-based separation processes are also proposed for recovery of critical metals, including nanofiltration, reverse osmosis, and electrically driven separation processes such as electrodialysis, bipolar electrodialysis, and selective bipolar electrodialysis (Chen et al. 2022; Elbashier et al. 2021; Huang and Xu 2006; Sarker et al. 2022; Zhou et al. 2018). Such membranes were originally designed to remove relatively low concentrations of ions from aqueous solutions, and much of the current research is aimed at understanding required modifications to membrane design to improve their utility in these new applications.

With an eye toward securing U.S. supplies of REEs, DOE’s Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management and National Energy Technology Laboratory assessed the feasibilities of extracting REEs from coal ore and coal combustion by-products at a request from Congress in 2014 and submitted the findings of the assessments to Congress in January 2017 (DOE 2017b). Subsequently, DOE began funding many RD&D projects to demonstrate

NOTE: The 2024 data include publications through March.

the feasibility of producing REEs from coals and coal wastes. The committee performed a literature review of publications on this topic since 2015, following the initial request from Congress for a feasibility assessment. The literature review, which can be found in Appendix L, analyzed the extraction method and leaching agent employed in each publication, as well as the resultant leaching efficiencies of REEs, lithium, and nickel. Since 2015, 211 journal articles, book chapters, conference materials, theses/dissertations, and DOE project reports have been published globally in the areas of REE, and/or lithium, and/or nickel extractions from coal wastes. Figure 9-8 shows the number of publications covering REE, lithium, and nickel by year, illustrating that most of the work has been performed on REE extractions. Table 9-4 shows the total number of publications by element/element group, by type of publications (for REE extraction), and by feedstock source (for research articles about REE extraction).

9.3.4.1 Current Technologies for Recovering Rare Earth Elements from Coal Wastes

Light rare earth elements (LREEs) are found in bastnaesite [(La,Ce,Y)CO3F], monazite [(Ce,La,Th)PO4], allanite [(Ce,Ca,Y,La)2(Al,Fe+3)3(SiO4)3(OH)], ancylite [Sr(Ce,La)(CO3)2(OH)·H2O], cerite [(Ce,La,Ca)9(Mg,Fe3+) (SiO4)6(SiO3OH)(OH)3], cerianite [(Ce,Th)O2], fluocerite [(Ce,La)F3], lanthanite [(REY)2(CO3)3·8(H2O)], loparite [(Ce,Na,Ca)(Ti,Nb)O3], parisite [Ca(Ce,La)2(CO3)3F2], and stillwellite [(Ce,La,Ca)BSiO5]. Bastnaesite is the primary source for praseodymium and neodymium (Omodara et al. 2019). The majority of heavy rare earth elements (HREEs) are found in xenotime (YPO4), yttrotungstite [YW2O6(OH)3], samarskite [(YFe3+Fe2+U,Th,Ca)2(Nb,Ta) 2O8], euxenite [(Y,Ca,Ce,U,Th)(Nb,Ta,Ti)2O6], gadolinite [(Ce,La,Nd,Y)2FeBe2Si2O10], yttrotantalite [(Y,U,Fe2+) (Ta,Nb)O4], yttrialite [(Y,Th)2Si2O7], and fergusonite (REY,NbO4). Ion adsorption clays are the dominant sources for dysprosium (Zapp et al. 2018) and holmium (Sanz et al. 2022) Monazite and bastnaesite are the major sources for erbium (RSC 2024). Terbium can be found in monazite, bastnaesite, and xenotime, as well as ion adsorption clays, which are its richest marketable sources (Sinha et al. 2023).

In solid coal wastes, REEs primarily exist in monazite (containing light rare earth elements) and xenotime (containing an HREE) in addition to organic matter/clays. The REE-containing minerals are exceedingly fine-grained with particle sizes ranging from less than 1 μm to 5 μm (Hedin et al. 2020; Li and Zhang 2022). In addition, some common REE-bearing minerals in coals do not contain REE structural constituents. These include zircon (ZrSiO4), REE-bearing phosphates such as apatite (Ca5(PO4)3(OH,F,Cl)) and crandallite (CaAl3(PO3.5(OH)0.5)2 (OH)6), and rhabdophane (REEPO4·H2O) (Dai et al. 2016; Finkelman et al. 2019; Kolker et al. 2024; Ward 2016).

TABLE 9-4 Number of Publications on REE, Li, and Ni Extraction from Coal Waste Since 2015 by Target Element, Publication Type, and Feedstock Source

| Category | Publications, 2015–2024a |

|---|---|

| Target Element(s) | |

| REEs | 210 |

| Lithium | 33 |

| Nickel | 11 |

| REE Extraction by Publication Type | |

| Research Article | 128 |

| Review Article | 21 |

| Book | 12 |

| Conference Paper | 12 |

| Project Report | 18 |

| Thesis/Dissertation | 9 |

| Patent | 8 |

| Source of REE in Research Articles | |

| Coal | 18 |

| Impoundment Waste | 20 |

| Coal Fly Ash | 66 |

| Coal Bottom Ash | 2 |

| Mixture of Coal Ash | 12 |

| Acid Mine Drainage | 10 |

a 2024 data include publications through March.

Although solid coal wastes from mining and combustion contain much lower concentrations of REEs than REE ores, they represent a significant potential resource for REE production, given the large volumes of these wastes (Das et al. 2018; DOE 2022; Huang et al. 2020; Jha et al. 2016; Opare et al. 2021; Peiravi et al. 2021; Wu et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2020a). DOE’s “interest level” for extracting REEs from coal waste is 300 ppm, based on demonstration of technical feasibility for obtaining high-purity REE from coal wastes at these concentrations (DOE 2017a, 2022). REE-bearing coal refuse contains REE concentrations as high as 300 ppm (Zhang and Honaker 2020a), and coal slags and ashes typically have higher concentrations of REEs than coal refuses (in some cases more than 1500 ppm; Scott and Kolker 2019). Total REE concentrations in AMD solids, on the other hand, can be as high as 2000 ppm (Hedin et al. 2024).

The total concentration of critical REEs (neodymium, europium, terbium, dysprosium, yttrium, and erbium)8 in coal ashes is a key factor that determines their potential economic values. Globally, the average fraction of critical REEs in coal ashes is 36 percent (Hower et al. In press), which is higher than some conventional REE ores (Fu et al. 2022). Thus, coal ashes could be important resources for providing critical REEs.

REEs can be extracted directly from sedimentary rocks including coal refuse or overburden (a carbonaceous rock with less organic matter than coal). Figure 9-9 shows a conventional process for extracting REEs from solid coal wastes, which includes both physical and chemical treatments. The first few operation steps are physical processes, and the remaining steps are chemical processes. Physical separation methods include air classification (Shapiro and Galperin 2005), gravity separation, magnetic separation, and flotation. Chemical methods include

___________________

8 Critical REEs are those for which supply (production) is projected to be less than demand (industrial consumption) (Seredin 2010; Seredin and Dai 2012). They are a subset of the critical minerals defined by the USGS.

NOTES: DEHPA = di-(2-ethyl hexyl) phosphoric acid; Na2SO4 = sodium sulfate; NaOH = sodium hydroxide; NH4OH = ammonium hydroxide; TBP = tributyl phosphate; TEHDGA = N,N,N’,N’ tetra (2-ethylhexyl) diglycolamide. Processes are discussed in the text. Feedstock indicated in purple text, intermediates in pink text, and product in blue text.

roasting with additives, leaching with chemicals (e.g., acids, ionic liquids, deep eutectic solvents), extraction, and precipitation. The physical treatment steps are similar for all types of solid coal wastes, although the order and operation conditions may differ slightly depending on the physical properties of the solid wastes. In contrast, the materials used in each chemical treatment step can differ significantly depending on the chemical structure and elemental compositions of the treated solid coal wastes.

Understanding the original structure and composition of REE-containing compounds in coal and their changes during coal combustion is important to the choices of physical and chemical treatment methods in Figure 9-9. Good progress has been made in this area. For example, a collaborative survey by the USGS, University of Kentucky Center for Applied Energy Research, and a utility company in Indiana on the ashes of Wyodak-Anderson (WY) coal indicated that the REEs mainly exist as inorganic phosphates (monazite) with trace silicates and carbonates (Brownfield et al. 2005). More recently, Fu et al. reviewed the content and occurrence mode of REEs in coal ashes from a variety of different countries, including the United States, finding that the average total REE concentration in the 257 tested U.S. samples from coal-fired power plants is 459.6 μg·g–1 or ppm, which is higher than the average value of samples from six European countries (Spain, England, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, and Finland; 278.7 μg·g–1) and four other countries (South Africa, India, South Korea, Indonesia; 298 μg·g–1) (Fu et al. 2022). The average concentrations of light (lanthanum to samarium, without the presences of scandium and promethium in this study); middle (europium to dysprosium, and yttrium); and heavy (holmium to lutetium) REEs in the U.S. samples are 340.8 μg·g–1, 100.5 μg·g–1, 18.3 μg·g–1, respectively (Fu et al. 2022). The average fraction of critical REEs in U.S. coal ashes was found to be 37 percent, slightly higher than the average fraction of critical REEs in the 581 tested coal ash samples from around the world (36 percent) (Fu et al. 2022). Fu et al. (2022) also found that REE-bearing phases in coal can undergo complex chemical transformation during coal combustion, as shown in Table 9-5. However, more studies are needed to characterize coal wastes to facilitate selection of appropriate chemicals for leaching REEs—for example, the choice of inorganic or organic acids.

An important chemical treatment step in the overall procedure of REE extraction from solid coal wastes is to leach REEs from the solid materials that contain many compounds, including a number of non-REE cations. Among the cations in the solid materials are Na+, Mg2+, Ca2+, Fe3+, Al3+, and Si4+, of which all except Si4+ can be

TABLE 9-5 Overview of Reported Thermal Decomposition and Transformation of Common REE Phases During Coal Combustion

| REE Speciation in Coal | Reference Compound | Phase Transformation During Thermal Conversion | Change in Oxidation State |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic associations | REE-lignin | REE-lignin → REE-oxides | Ce(III) → Ce(IV) |

| Carbonates | Y2(CO3)3 Ce2(CO3)3 (Ce,La)CO3(F,OH) REE-doped calcite |

Y2(CO3)3 → Y2O3 Ce2(CO3)3 → CeO2 (Ce,La)CO3(F,OH) → (Ce,La)O2 CaCO3 → CaO |

No change Ce(III) → Ce(IV) Ce(III) → Ce(IV) No change |

| Phosphates | Hydrated YPO4 Hydrated CePO4 Monazite Xenotime Calcium Apatite |

YPO4·2H2O → YPO4 CePO4·2H2O → CePO4 Size reduction via fragmentation (>1400°C) No Change |

No change No change |

| Fluorapatite melts at 1644°C; Chlorapatite structure change begins 200°C, with melting at 1530°C; Hydroxy apatite dehydroxylates at 900°C and decomposes above 1200°C |

No change Partial oxidation |

||

| Silicates | Zircon | No change below 1000°C Melting above 1000°C ZrSiO4 → ZrO2-t + SiO2 (>1285°C) |

No change |

SOURCES: Based on data from Fu et al. (2022); Hood et al. (2017); Liu et al. (2020); and Tõnsuaadu et al. (2012).

easily leached from the source material. The concentrations of each of these cations can be more than 1000 times higher than the total concentration of REEs in solid coal wastes. Therefore, the choice of solvent to maximally leach REE cations and minimally leach non-REE cations is important for cost and efficiency. In general, organic acids are better than mineral acids for selectively leaching REEs from solid coal wastes (Banerjee et al. 2021b). The use of organic acids to leach REEs also maximally maintains the chemical structure of coal fly ash, which is important to its major applications in cement or brick industries.

In recent years, new leaching approaches have been developed to overcome safety and environmental issues resulting from strong chemicals—for example, corrosion, toxicity, and explosion, by using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents for solvent extraction (Alguacil and Robla 2023; Danso et al. 2021; Karan et al. 2022). Owing to their very low vapor pressure and intrinsic electric conductivity, ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents could replace the organic phase in liquid-liquid extraction processes, resulting in safer operation systems. Stoy et al. (2021) achieved 83 percent and >90 percent leaching efficiencies with a fly ash without and with pretreatments, respectively, when using an ionic liquid [Hbet][Tf2N] (Nockemann et al. 2006, 2008), to separate REEs from a coal fly ash sample. Karan et al. (2022) used a choline-chloride-based deep eutectic solvent system for REE extraction from a coal fly ash sample and achieved 85–95 percent leachability. Despite their potential benefits, ionic liquids tend to be significantly more costly than conventional solvents. Most ongoing research on ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents is still at bench scale, and their feasibility at larger scales continues to be evaluated.

Supercritical fluids, including supercritical CO2, have been explored for leaching REEs from coal by-products. Supercritical-fluid-based REE extraction technology is promising owing to the high diffusivities and low viscosities of supercritical fluids and ease of scale up. High extraction efficiencies, especially for HREEs, can be achieved with supercritical fluids, particularly supercritical CO2. REE extraction with supercritical CO2 is environmentally friendly and has been demonstrated to concentrate REEs at 312 ppm in fly ash to 99.4 percent in the final product in form of REOs, with the five critically important HREEs (dysprosium, europium, neodymium, terbium, and yttrium) accounting for up to ~63 percent of the total weight of the final REO product (Fan and Huang 2023; Huang et al. 2018).

Another approach to REE separation and recovery from coal by-products uses molecular recognition technology, which has the capability to perform selective separations at various stages in metal life cycles (Bentzen et al. 2013; Gielen and Lyons 2022; Oberhaus 2023). High REE selectivity, both as a group or as individual elements, can be obtained using a predesigned ligand bonded chemically by a tether to a silica gel solid support. Separations are

performed in column mode using feed solutions containing the target REE in a matrix of acid and/or other metals. The target REE is selectively separated by the silica gel–bound ligand, leaving other solution components to go to the raffinate, where individual components can be further recovered. The high selectivity means metal impurities do not have to be removed downstream, which simplifies the process. It has been claimed that a molecular recognition technology plant will offer lower capital and operating costs, as well as a lower physical and environmental footprint, than an equivalent conventional solvent extraction plant (Ucore 2022). The process could be superior to alternatives in capital and operating costs and with potential environmental benefits.

Different REE extraction methods have their advantages and disadvantages from different perspectives. Many factors, including the type of coal waste, REE extraction method, and conditions (e.g., type of leaching agent, leaching temperature, and leaching time) affect the overall REE recovery efficiency. Furthermore, the form and content of REEs differs between coal ashes from the western and eastern United States. The majority of REEs in low-rank western coals are complexed with organic compounds rather than inorganic materials, and thus are more readily extractable than higher-rank eastern coals, despite having a lower overall REE content.

As mentioned earlier, the committee performed a literature review of REE extractions from coal waste streams to examine the state of the field and understand some of these factors impacting recovery efficiency. The full literature review is presented in Appendix L, while results of the committee’s subsequent analysis are depicted in Figures 9-10, 9-11, and 9-12. Based on data reported from 2019 to 2023, the average REE recovery efficiency obtained with AMD is higher than those achieved with other coal waste types (Figure 9-10). Figure 9-11 indicates that chemical leaching is, on average, more efficient than bioleaching when coal waste pretreatment is used to enhance REE leaching with chemicals. Much longer leaching times are needed for bioleaching processes.

Challenges for extraction of REEs from coal wastes are significant, which could be a major reason why no considerable increase in average leaching efficiency has been observed in recent years, as indicated in Figure 9-12. One challenge is the use of strong mineral acids in leaching processes, which can lead to serious environmental pollution. Thus, R&D opportunities for extraction of REEs from coal waste center around developing improved physical and chemical separations processes. As noted above, a better understanding of the structure or morphology of REEs in coal by-products would facilitate the choice of physical beneficiation and operation steps. Integrating different physical separation methods could improve the efficiency of physical separation processes, with a goal of rejecting the CM-containing fractions and preconcentrating the CMs. The low concentration of REEs in coal wastes and coal combustion by-products (typically <100 μg g–1 for an individual element) makes leaching processes expensive. Development of more selective solvents could yield cost reductions.

NOTES: See Table L-1 in Appendix L for underlying data. Bar height indicates average recovery efficiency value.

NOTES: See Table L-1 in Appendix L for underlying data. Bar height indicates average recovery efficiency value.

9.3.4.2 Current Technologies for Recovering Energy-Relevant Critical Minerals from Coal Wastes

Deploying clean energy technologies at scale will require substantial amounts of CMMs, and supply chain risks or bottlenecks in obtaining these minerals and materials could inhibit the net-zero transition (DOE 2023). Table 9-6 lists the clean energy technology applications of 12 elements and materials of particular interest: neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, graphite, iridium, platinum, gallium, and germanium. Coal waste streams represent one potential domestic source of these energy-relevant minerals and materials, with estimates of tens to thousands of years of supply for certain elements at current rates of consumption (see Table 9-6). Methods to obtain graphite from coal wastes were discussed in Section 9.3.3.2 above. In the following sections, extraction of lithium and nickel are described as case examples because most literature on CM recovery from coal wastes (mainly) focuses on these elements, and the estimated masses of lithium and nickel

NOTES: See Table L-1 in Appendix L for underlying data. Bar height indicates average recovery efficiency value.

TABLE 9-6 Key Elements and Materials for Clean Energy Technologies and Estimated Domestic Supply from Coal Waste Streams

| Metal/Material | Technology Application | Estimated Mass (tons) | Estimated Supply (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neodymium Praseodymium Dysprosium | Magnets for wind energy generators, electric and fuel cell vehicle motors, and industrial motors | 172,000 Not reported 62,000 |

40 Not reported 14 |

| Lithium Cobalt Nickel Manganese Graphite |

Batteries for electric vehicles and electricity storage | 288,000 110,000 252,000 Not reported Not reported |

130 15 1.1 Not reported Not reported |

| Iridium Platinum |

Electrolyzers for hydrogen production; fuel cells for transportation, stationary energy storage | 40 600 |

15 15 |

| Gallium | Wide bandgap power electronics for connecting high voltage power generation to the grid | 20,000 | 1100 |

| Germanium | Semiconductors; fiber and infrared optics for sensors, data, and control | 30,000 | 3900 |

SOURCE: Adapted from Wilcox (2023).

in coal wastes are higher than those of other elements (Table 9-6). Both lithium and nickel exist in coal (Zhang et al. 2020b), AMD (DOE 2022; Fritz et al. 2021; Hedin et al. 2020; Li and Zhang 2022; Stuckman 2022), and coal ash (Gupta et al. 2023; Hamidi et al. 2023) at varying concentrations, depending on the structure and chemical composition of the coal, including sulfur content and metal concentration. A final section briefly describes processes to extract other CMMs relevant to energy supply chains from coal wastes.

9.3.4.2.1 Characteristics of Lithium in Coal Wastes and Separation of Lithium from Coal Wastes

Lithium is a widely used critical mineral that has been playing an increasingly important role in rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles and various electronic devices, in addition to its use in the production of pharmaceuticals, ceramics, glass, metallurgy, and polymers. Between 2010 and 2022, the world’s production of lithium, in the form of lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide, nearly quadrupled (Energy Institute 2023). Lithium markets are anticipated to increase by 13 times by 2040 in a base case scenario and could grow by 40 times by 2040 in a sustainable development scenario (IEA 2022). The well-known lithium deposits are peralkaline and peraluminous pegmatite deposits and their associated metasomatic rocks, lithium-rich hectorite clays derived from volcanic deposits, and Salar evaporites and geothermal deposits (Bowell et al. 2020). Lithium-rich rocks include spodumene (6–9 wt% Li2O), petalite (3.0–4.73 wt% Li2O), lepidolite (3.0–4.19 wt% Li2O), zinnwaldite (2–5 wt% Li2O), amblygonite (7.4–9.5 wt% Li2O), montebrasite (7.4 wt% Li2O), eucryptite (4.5–9.7 wt% Li2O), triphylite (9.47 wt% Li2O), jadarite (7.3 wt% Li2O), and hectorite (<1–3 wt% Li2O) (de los Hoyos 2022; Evans 2014; Garrett 2004; London 2008). However, these mining resources of lithium are being exploited steadily and quickly depleted. Thus, other lithium-containing resources, such as brines, seawater, and waters from oilfields, geothermal fields, and mining of coal and other ores, need to be developed.

Coal contains lithium at global average concentrations of about 12 ppm (Ketris and Yudovich 2009), while the average concentration of lithium in U.S. coals is 16 ppm (Orem and Finkelman 2003). Coal fly ash contains a global average concentration of 66 ppm lithium (Ketris and Yudovich 2009). More than 90 percent of the lithium in U.S. coals is in clays and micas, and the remaining amount is associated with either organics or tosudite [Na0.5(Li,Al,Mg)6((Si,Al)8O18)(OH)12·5H2O] and cookeite [LiAl4(AlSi3O10)(OH)8] (Finkelman et al. 2018; Seredin et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2020b). The concentrations of lithium in high-rank coals are significantly higher than those in low-rank coals owing to the association of lithium with detrital silicates in the former (Dai et al. 2021). Accordingly, the concentrations of lithium in AMD, solid coal wastes, and coal combustion wastes vary significantly with the types and locations of coals.

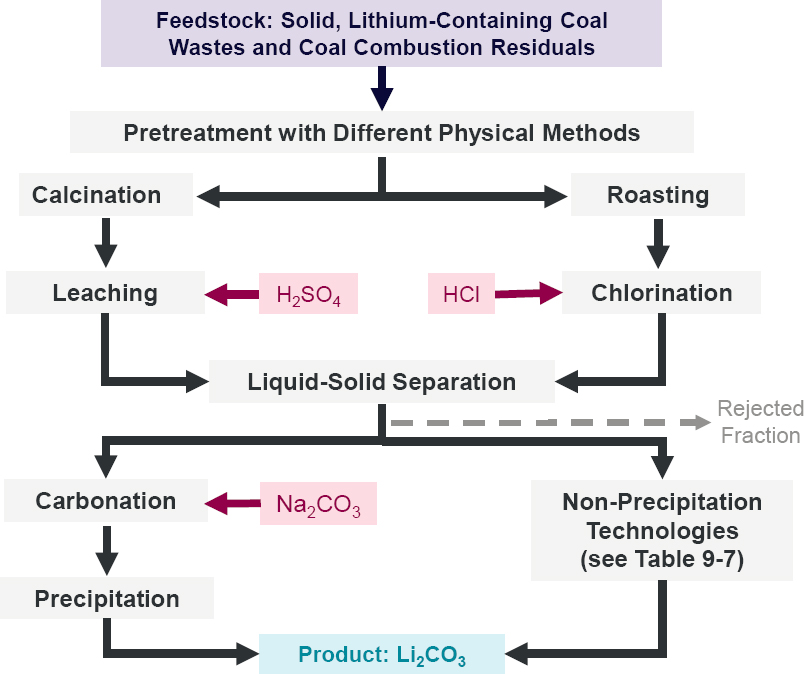

AMD contains lithium that can dissolve in water at low pH (Griswold 2022; Kolker et al. 2024). Thus, lithium can be separated from AMD using reported methods for recovering lithium from water (Baudino et al. 2022), including evaporation, precipitation, lithium-ion sieves (e.g., aluminum hydroxide ion sieves, lithium manganese oxide ion sieves, and lithium titanium oxide ion sieves), membranes, supramolecular chemistry, ionic liquids, and electrochemistry. The principles, advantages, and disadvantages of different methods are shown in Table 9-7. Different factors affect the technological performance, economic feasibility, and carbon and overall environmental footprint of various lithium extraction technologies. Some approaches contain multiple operation steps, with different factors affecting these same metrics for each step. For example, the conventional precipitation approach, shown in Figure 9-13, involves six steps. The operational performance of Steps 1, 3, and 6 is controlled by the quantities of the added chemicals (i.e., CaO/Ca(OH)2, Na2C2O4, Na2CO3) and the pH values of the liquids, while the operational performance of Steps 2 and 4 is determined by temperature and characteristics of the filters, as well as filtration operation conditions. Multiple technologies can be integrated to achieve high lithium recovery efficiency and product purity.

TABLE 9-7 Technologies for Separating Lithium from Acid Mine Drainage and Other Lithium-Containing Aqueous Solutions

| Technology | Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | Vaporization Based on concentrating Li+ in solution via the loss of H2O, realized by using solar energy (i.e., solar-heated evaporation) |

|

|

|

Precipitation Based on the formation of insoluble or low solubility lithium salts

|

|

|

|

|

Ion exchange Based on sorption and desorption

|

|

|

|

| Solvent extraction Based on (1) the difference of Li+ solubilities in aqueous solution and organic solvents (e.g., tributyl phosphate [TBP]) and (2) the formation of Li+-containing complex structures dissolvable in organic materials, and stripping Li+ out of the organic phase with acids (e.g., HCl) |

|

|

|