Carbon Utilization Infrastructure, Markets, and Research and Development: A Final Report (2024)

Chapter: 5 Mineralization of CO2 to Inorganic Carbonates

5

Mineralization of CO2 to Inorganic Carbonates

Mineralization of CO2 is a key approach to carbon management, both to geologically store carbon and to produce inorganic carbonate solids that can be used in various ways, including to support the defossilization of the built environment. The mineralization process converts thermodynamically stable, gaseous CO2 into an insoluble solid with similar thermodynamic stability and a lifetime on geologic timescales. In nature, mineralization occurs through the weathering of minerals and rocks containing alkaline metals such as calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg). These minerals react with moisture and CO2, dissolve, and precipitate as solid carbonates. However, this natural weathering occurs too slowly to contribute to carbon utilization solutions; timescales for natural mineralization can be hundreds or thousands of years, depending on the concentration of CO2 and rock type. Hence, research and development (R&D) have increased in recent years to produce carbon mineralization technologies that chemically and physically accelerate mineral dissolution and carbonate precipitation processes to useful rates and scales. This report’s scope includes CO2 conversion to tradable inorganic carbonate commodities that are used in applications such as building materials, pigments and fillers, and excludes in situ mineralization processes where the product is not extracted from the environment, such as enhanced rock weathering and ocean alkalinity adjustment.

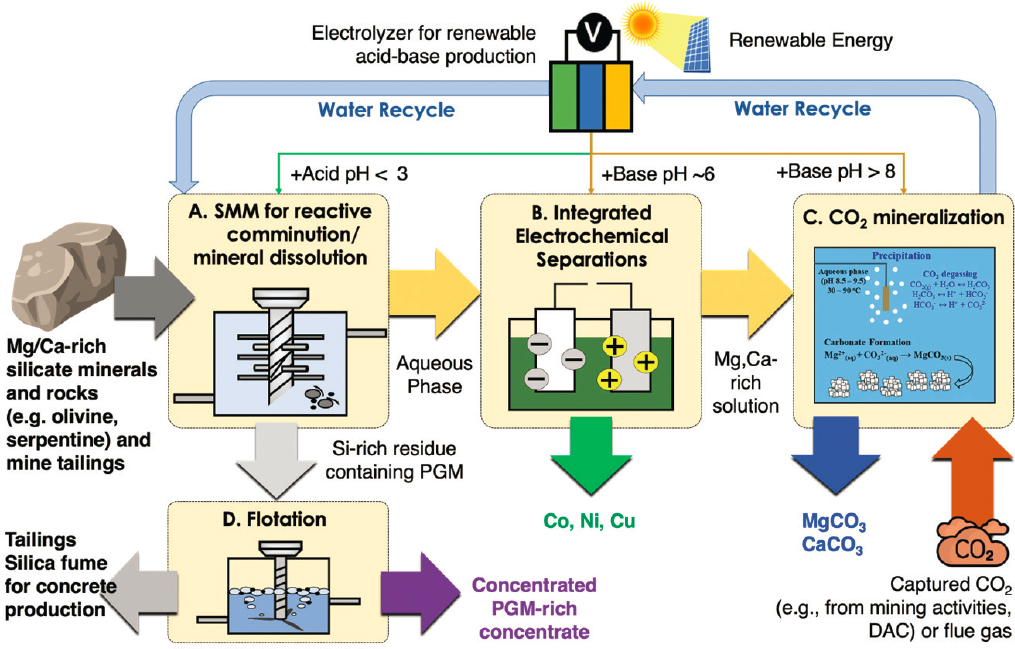

As mentioned in Chapter 2, construction materials like cement are derived from carbon-bearing minerals and rocks (e.g., limestone). In 2021, cement production emitted about 2.69 gigatonne (Gt) CO2 globally (Andrew 2023), in part from emissions from fossil fuel combustion used to heat the reaction, and in part from the CO2 released from minerals as they are transformed. An opportunity exists to significantly reduce global CO2 emissions by utilizing inorganic carbonates produced from captured CO2 in physical infrastructure to displace higher-carbon-emitting products. In recent years, new feedstocks and unconventional resources, including alkaline industrial wastes and alkaline materials derived from seawater and brine, have been identified for carbon mineralization technologies. The integration of renewable energy and carbon mineralization with mining and mineral processing (called carbon-negative mining1) also has opened up new applications and strategies for carbon management in the form of inorganic carbonates while creating additional economic benefits (e.g., recovery of energy-relevant critical minerals as by-products).

This chapter focuses on the status, challenges, and R&D needs for the mineralization of CO2 into inorganic carbonates for use in durable building materials at a scale relevant to climate change mitigation. Carbon mineralization technologies are at a more advanced stage as compared to CO2 utilization technologies discussed in other

___________________

1 Carbon-negative mining is a mining process in which CO2 emissions produced during mining as well as CO2 from other industrial emissions are stored in mined rocks (e.g., as solid carbonates) and geologic formations.

SOURCE: Icons from the Noun Project, https://thenounproject.com. CC BY 3.0.

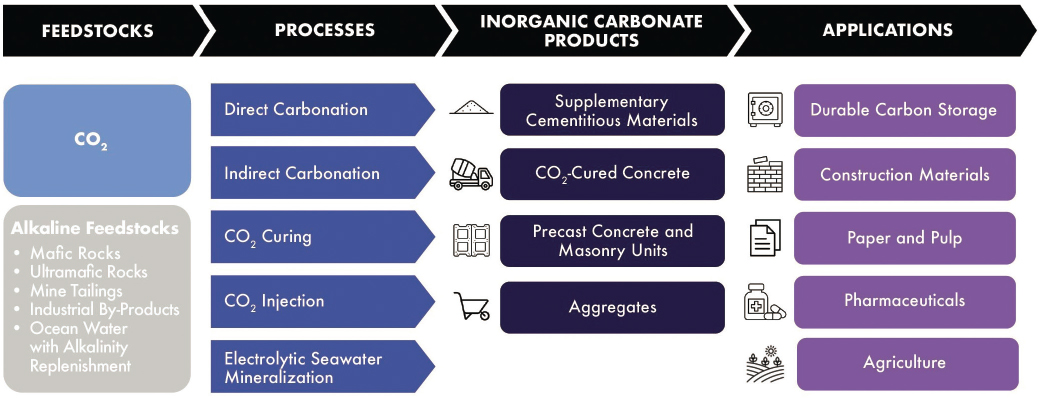

chapters, ranging from fundamental research to industrial deployment. Thus, this chapter discusses how U.S. R&D investment from both government and industrial funding sources (e.g., large corporations, start-ups, venture capital, investment funds, and banks) could accelerate critical discoveries and advance carbon mineralization technologies to make transformational impact at scale. Carbonation of fly ash and carbon-negative mining using mine tailings and alkaline industrial waste are discussed in the present chapter, while coal waste as an unconventional feedstock for carbon utilization is covered in Chapter 9. Figure 5-1 shows the major features of mineral carbon utilization, including feedstock inputs, processes, products, and applications. The remainder of the chapter describes the current status and research, development, and demonstration (RD&D) needs for processes and resulting products, noting relevant applications where appropriate.

5.1 OVERVIEW OF CO2 CONVERSION TO INORGANIC CARBONATES

5.1.1 Inorganic Carbonate Products That Can Be Derived from CO2

The current construction materials industry faces a dual challenge: increasing expectations for regulation mandating reduced carbon emissions and simultaneous rapid global demand growth for physical infrastructure. The market for concrete and construction aggregates continues to expand, while conventional construction material manufacturing processes are associated with significant environmental impacts (e.g., carbon emissions, mining-related water contamination, and air pollution). Carbonate minerals and rocks, such as limestone (CaCO3) and dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2), have been widely used in large quantities to produce cement and refractory materials, respectively (Haldar 2020). While the most common use of calcium carbonate is as a feedstock to produce construction materials, it is also used in nonconstruction applications. For example, high-purity (90–99 percent, depending on the application) calcium carbonate (CaCO3) is used as a filler in paper, paint, rubber, and plastic, among other applications (Ropp 2013; Tanaka et al. 2022).

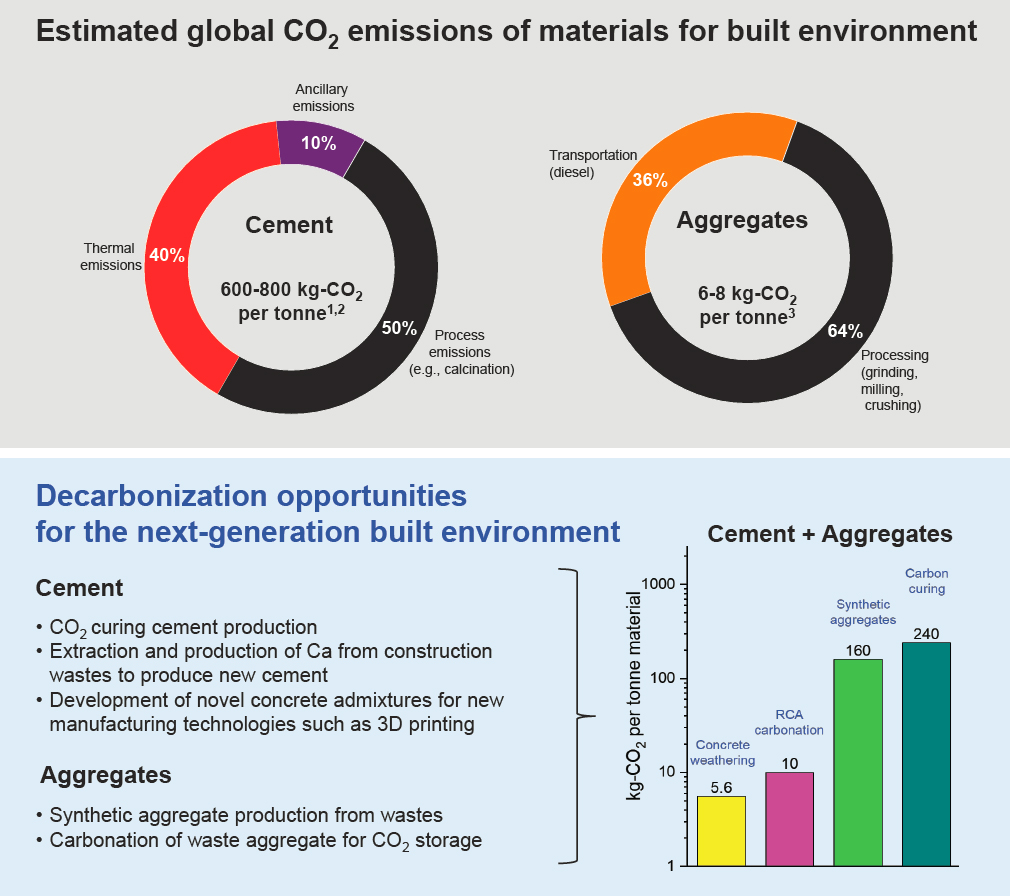

The mining, quarrying, transportation, and processing of carbonate minerals and rocks for construction materials have resulted in significant carbon emissions contributing to climate change despite serving as key processes for physical infrastructure build-out. Primary mineral construction materials include cementitious materials, concrete (a mixture of sand, cement, water, and aggregates), mortar (a mixture of cement and sand), and masonry materials (bricks). Figure 5-2 shows the estimated global CO2 emissions associated with major construction materials—cement and aggregates—currently used in the built environment. The continued use of natural carbonate minerals and rocks to create cement and concrete is not compatible with achieving net-zero emissions.

NOTE: RCA = recycled concrete aggregate.

SOURCES: Adapted from Park et al. (2024), https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2024.1388516. CC BY 4.0. Data from Gerres et al. (2021); Ho et al. (2021); Holappa (2020); IEA (2022); Lehne and Preston (2018); Mayes et al. (2018); Rosa et al. (2022); Seddik Meddah (2017); Zhang et al. (2020a).

Concrete is produced conventionally by combining Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) powder (clinker + gypsum) with water, sand, and gravel. More than 4 billion tons of cement were produced in 2021; the demand for cement continues to rise and is expected to reach 6.2 billion tons by 2050 (GCCA 2021; IEA 2022). The CO2 emitted from manufacturing cement is responsible for about 7–8 percent of global carbon emissions (Andrew 2023; IEA 2022). As shown in Figure 5-2, these emissions are primarily industrial process emissions from the chemical reaction of limestone decarbonation to produce clinker2 and from the carbon-intensive fuels required to reach the high temperatures needed in cement kilns (up to 1400°C), together accounting for 90 percent of the carbon emissions

___________________

2 Desired clinker phases are alite (Ca2SiO4, sometimes formulated as 3CaO·SiO2 [C3S in cement chemist notation]), belite (Ca2SiO4, sometimes formulated as 2CaO·SiO2 [C2S in cement chemist notation]), aluminate (Al2O3), and ferrite (Fe2O3).

from cement production (Fennell et al. 2021; Park et al. 2024). The current global production rate of aggregate is approximately 40 billion metric tons per year (Global Aggregates Information Network 2023). Producing 1 metric ton of cement and 1 metric ton of aggregate can lead to emissions of approximately 0.6–1 metric tons CO2 and 6–20 kg CO2, respectively (Czigler et al. 2020; Fennell et al. 2021; IPCC 2023; Monteiro et al. 2017). From an economic perspective, cement production accounts for the most emissions per revenue dollar at about 6.9 kg of CO2 per dollar of revenue generated (Czigler et al. 2020).

Figure 5-2 (bottom) lists innovative and transformative technological options currently being developed and employed to reduce CO2 emissions associated with cement and aggregate materials. Strategies to mitigate carbon emissions in the construction materials industry cover different domains: mining (e.g., quarrying and transportation with improved efficiencies and the use of sustainable energy); integrated process design (e.g., using renewable energy to produce cement clinkers, capturing or purifying CO2 from cement plants, CO2 curing for concrete); new and alternative materials production with lower carbon footprints (e.g., supplementary cementitious materials, admixtures); and sustainable demolition and upcycling processes (e.g., upcycling demolished materials) (Miller et al. 2021; Ostovari et al. 2021; Tiefenthaler et al. 2021).

It is not easy to reduce the amount of cement in concrete because cement is the binder required to provide the mechanical properties of concrete (e.g., compressive strength, durability). The required amount of binder varies by application (e.g., structural versus nonstructural), and standards vary by country. An alternative material that can replace cement binder in concrete is called a supplementary cementitious material (SCM). SCMs react with water (hydraulic reaction) and/or calcium hydroxide (pozzolanic reaction), enhancing material strength and durability while reducing the overall life cycle CO2 emissions of concrete. Limestone (CaCO3) is calcined to produce Ca(OH)2 leading to CO2 emissions. The use of end-of-life carbonate wastes such as CaCO3 in demolition wastes could provide a net-zero pathway to produce Ca(OH)2. If silicate minerals (e.g., wollastonite, CaSiO3) are used to produce Ca(OH)2, the net carbon intensity of the produced concrete would be lowered further. Some minerals and alkaline industrial wastes react with CO2 to form SCMs. Each U.S. state has at least one type of prescriptive specification that either requires certain proportions of traditional cement and concrete materials, limits substitution rates of SCMs and other alternative materials, or restricts which materials are acceptable for certain applications (Kelly et al. 2024). Because developers and construction firms carefully follow state and local codes, prescriptive specifications encourage traditional materials over deployment of innovative materials. Several states are pursuing performance specifications based on desired engineering performance (durability, strength, flexibility, temperature-tolerance) rather than mandating particular material mixes (e.g., ASTM International 2023a). Performance standards require significant investments in training and technical capacity at the state and local levels, where code enforcement occurs, as well as in benchmarking and performance testing equipment and protocols.

Other carbon mineralization approaches the cement industry is taking to reduce their CO2 emissions include the reincorporation of CO2 back into the concrete product, either up front during mixing and curing of concrete or via treatment of concrete demolition waste at the conclusion of its service life (Winnefeld et al. 2022). For example, concrete masonry units (CMUs)—tiles, bricks, or blocks with a mixture of powdered Ca-rich steel slag, water, and aggregate—have been produced without cement by incorporating SCMs (e.g., steel slag). These CMUs are cured in a chamber with CO2 captured from industrial sources, allowing steel slag to react with CO2 to produce CaCO3. This incorporates additional carbon into solid carbonate and reduces the energy requirement for concrete curing. The newly formed carbonates act as binders, which eliminates the need for much of the carbon-intensive cement paste. Researchers have tested the performance of products with up to 75 percent cement replacement and are pursuing blends with up to 100 percent cement replacement (George 2023; Jin et al. 2024; Nukah et al. 2023; Phuyal et al. 2023; Shah et al. 2022; Srubar et al. 2023). The current products are used in precast concrete road pavement blocks, river embankment blocks, or ceilings (Li et al. 2022a).

CMUs produced using steel slag as SCMs have been reported to have higher compressive strength than cement-based CMUs, but CMUs using steel slag SCMs can also be more brittle or porous, affecting potential applications (Newtson et al. 2022; Nguyen et al. 2020; Parron-Rubio et al. 2019; Taha et al. 2014). Some of these alternative cements have been certified as meeting ASTM C90 or C150 standards as construction materials. Their performance and quality can be maintained using a mixture of OPC and SCMs, which cuts greenhouse gas emissions in proportion to the fraction of SCM used. Other approaches to produce concrete with carbon storage include

the addition of γ-C2S (made from calcium hydroxide [Ca(OH)2] and silica) into the concrete (forming a water, cement, aggregate, γ-C2S, industrial wastes mixture). The strength and durability of the γ-C2S concrete improves upon reaction with CO2 during the curing process.

The construction materials industry is developing technologies to utilize captured CO2 for curing concrete, carbonating natural minerals or industrial wastes to produce SCMs, and to produce synthetic aggregate to store more CO2 in construction materials (e.g., fillers) (Norhasyima and Mahlia 2018). Carbon mineralization technologies are amenable to being optimized to utilize dilute concentrations of CO2, such as flue gas (~15 percent CO2), directly to form carbonate products, eliminating the need for energy-intensive CO2 capture and compression. The co-location of CO2 sources with alkaline wastes is desirable, in order to minimize transportation and cost. Using CO2 to produce synthetic aggregate could reduce mining of carbonated minerals and rocks, which naturally store CO2, and avoid greenhouse gas emissions, ecological degradation, and human health risk.

5.1.2 Conversion Routes

Carbon mineralization (also known as mineral carbonation or CO2 mineralization) is a chemical phenomenon in which divalent alkaline metal ions such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ react with CO2 to produce solid carbonates. In nature, minerals containing Mg, Ca, or iron (Fe) such as serpentine (Mg3Si2O5(OH)4), olivine (Mg2SiO4), and wollastonite (CaSiO3), can react with CO2 in the air to form a stable and inert carbonate rock, a process called weathering (Blondes et al. 2019; Gadikota et al. 2014; Kashim et al. 2020; Park and Fan 2004). While these minerals contain varied concentrations of Fe and other mineral phases, here the chemical formulas are written only using Mg and Ca for simplicity. There are three key reaction steps in natural or engineered carbon mineralization, illustrated in the following reactions: (1) CO2 hydration (Reactions 5.1–5.3); (2) mineral dissolution (Reactions 5.4–5.6); and (3) formation of solid inorganic carbonates (Reactions 5.7–5.8). While there are numerous fundamental studies of the kinetics of CO2 hydration, mineral dissolution, and formation of carbonates, the coupled effects of pH, temperature, and partial pressure of CO2 on coupled mineral dissolution and carbonation behavior can vary widely depending on the complexity of the starting minerals, rocks, or industrial waste. The carbon mineralization reactions for three major Mg- and Ca-bearing silicate minerals are as follows:

| CO2 hydration: | CO2(g) → CO2(aq) | (R5.1) |

| CO2(aq) + H2O → H2CO3(aq) ↔ + | (R5.2) | |

| → | (R5.3) | |

| Forsterite dissolution: | Mg2SiO4(s) + → + SiO2(s) + 2H2O | (R5.4) |

| Wollastonite dissolution: | CaSiO3(s) + → + SiO2(s) + H2O | (R5.5) |

| Serpentine dissolution: | Mg3Si2O5(OH)4(s) + → + 2SiO2(s) + 5H2O | (R5.6) |

| Carbonate formation: | → MgCO3(s) | (R5.7) |

| CaCO3(s) | (R5.8) |

Carbon mineralization can occur via utilization or non-utilization modes, as illustrated in Figure 5-3. Panel 4 of Figure 5-3 shows in situ carbon mineralization, which occurs when CO2 is injected into reactive geologic formations with high Ca and Mg content. Panel 3 shows enhanced rock weathering, where alkaline feedstock is spread in the environment to react with CO2 and be stored in dispersed, solid carbonates in the environment. While both in situ carbon mineralization and enhanced rock weathering could increase the CO2 sequestration potential of the carbon storage reservoir or natural environments, respectively, they would not result in inorganic carbonate commercial products, and so are out of scope of this report. The focus of this chapter is the direct and indirect utilization approaches to carbon mineralization shown in panels 1 and 2 of Figure 5-3, which could produce high-value products like concrete, aggregates, fillers, and pigments, as discussed in Section 5.1.1.

NOTES: Panels 1 and 2 of the figure show direct and indirect approaches, respectively, that create mineral carbon products and are explored further in this report. Panels 3 and 4 show surficial enhanced rock weathering and in situ geologic mineralization, which do not create products and are out of scope of this report. Alkaline feedstock = alkaline mine tailings, some industrial by-products and certain types of mined rock (e.g., silicate minerals such as serpentine, olivine and wollastonite).

SOURCES: Adapted from Riedl et al. (2023). Icons from the Noun Project, https://thenounproject.com. CC BY 3.0.

Carbon mineralization technologies generally fall into two operating modes: direct and indirect carbonation. Direct carbonation involves a single-step reaction of CO2 and materials (e.g., minerals, rocks, alkaline industrial wastes), whereas the indirect process comprises multistep reactions and separations (i.e., inorganic solid dissolution at lower pH [<4] facilitated by leaching agents such as acids and chelating agents targeting Ca and Mg, followed by carbonation at higher pH [>8]). Various factors can impact mineralization and subsequently influence the properties of produced construction materials. For example, indirect carbonation allows reaction and separation steps to be optimized individually, therefore enabling production of higher purity products and making it easier to produce inorganic carbonates and by-products (e.g., high surface area SiO2 that can replace silica fume) with tailored chemical and physical properties. However, the energy (e.g., heat and electricity) and chemical (e.g., acids and ligands) inputs required for the overall indirect carbonation (and attendant, potentially hazardous, liquid waste disposal) would be greater compared to direct carbonation where CO2 is the main input. The net carbon benefits and environmental impacts for each technology need to be carefully evaluated via life cycle assessment (LCA).

Direct carbonation is a process in which CO2 is introduced into solid materials or aqueous slurry/solutions rich in Ca/Mg to form solid carbonates (Gadikota et al. 2015). It is simple and capable of handling materials in a single process to generate metal carbonates (Swanson et al. 2014). Many of the current commercialized construction materials emissions mitigation technologies in the construction materials industry react alkaline industrial

wastes with CO2 to form Ca or Mg carbonates via direct carbonation. These multiphase reactions typically involve gas-solid and gas-liquid-solid processes, similar to natural weathering reactions, but with faster rates than those of natural processes (Campbell et al. 2022; Pan et al. 2018). The interaction between the minerals and CO2 still involves a sequence of processes, including hydration, dissolution, and carbonation, but within a single reactor. In addition to reaction temperature, the hydration level (or water amount) can influence significantly the direct carbonation rates and polymorphs of carbonate products (e.g., nesquehonite [MgCO3·3H2O], hydromagnesite [(MgCO3)4·Mg(OH)2·4H2O] and magnesite [MgCO3]) (Fricker et al. 2013, 2014). Generally, natural silicate minerals—including serpentine—cannot be converted to carbonate minerals via gas-solid reactions owing to their very slow reaction kinetics without water. However, more reactive materials such as fly ash and cement kiln dust can be directly converted to carbonate products via gas-solid reactions. Most direct carbonation processes employ a slurry reactor that operates at high temperature (up to 185°C) and CO2 pressure (up to 150 atm) to achieve significant carbonation within a few hours.

Indirect carbonation refers to the multistep process of leaching out active metals from minerals (i.e., Ca and Mg) using solvents containing acids (weak acids or CO2 bubbling can be used as a sustainable acid) and chelating agents targeting Ca and Mg (e.g., citrate, acetate, and oxalate) (Gadikota et al. 2014). The pH of the Ca- and Mg-rich solution then is increased to a pH >9 to promote the formation of solid carbonates while injecting/bubbling CO2 into the reactor. The dissolution and carbonation processes can be controlled and optimized by varying pH and temperature. The carbonate products obtained from indirect carbonation are high purity (>99 percent if the solid residue from the mineral dissolution reactor is removed before the carbonation step), and their polymorphs can be tailored for different applications in various industries, such as construction, paper, and rubber (Zhang and Moment 2023; Zhao et al. 2023a, 2023b). For example, the polymorphs of CaCO3 include vaterite, aragonite and calcite, and recent studies have demonstrated different reactivities of these polymorphs in cement pastes (Zhang and Moment 2023; Zhao et al. 2023a, 2023b). Furthermore, the use of different ligands during a multistep carbon mineralization process also allows for the selective extraction of other valuable metals, including rare earth elements (REEs), Ni, Co, and Cu (Hong et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2021; Sim et al. 2022). The extraction and recovery of these critical metals provide additional economic benefits for carbon mineralization technologies.

Carbon mineralization also can be used to durably store CO2 within the carbonates in SCMs, recycled aggregates, or CO2-cured concrete (Supriya et al. 2023; Zajac et al. 2022). As described above, SCMs can reduce significantly the life cycle CO2 emissions of construction materials, and the feedstock can be natural minerals (Mg/Ca silicates) or industrial wastes (e.g., fly ash, steel slags, mine tailings, brines, red mud), which are emerging as promising alternative resources owing to their widespread availability (see Chapter 9 for more on the use of fly ash as a coal waste stream). In some cases, these alternative feedstocks not only can lower environmental impact but also can improve the performance of concrete products. Recent techno-economic assessment (TEA) has revealed that using SCMs produced via carbon mineralization reaction can be profitable, with approximately $35 more revenue per metric ton of cement produced and with CO2 emission reductions of 8–33 percent compared to conventional cement (Strunge et al. 2022). The economic value results from the higher quality of produced SCMs and the value of the carbon storage associated with carbonates incorporated into cement.

This chapter describes a number of innovative pathways to produce sustainable construction materials via carbon mineralization. Current bottlenecks for viable mineral carbonation processes on an industrial scale include large energy requirements for mining and mineral processing, and the need to further accelerate both mineral dissolution and carbonation rates. Additionally, new formulations of materials, such as concrete derived from carbon mineralization, will require testing and property validation before being accepted by users and construction materials market regulators. Existing and emerging carbon mineralization technologies and their specific challenges and opportunities are discussed in the next section.

5.2 EXISTING AND EMERGING PRODUCTS, PROCESSES, CHALLENGES, AND RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES

The current status of carbon mineralization technologies spans across technology readiness levels (TRLs) from fundamental research to commercialization. The carbonation of alkaline industrial wastes, such as fly ash and iron and steel slag, has been deployed at an industrial scale, in part because of beneficial economic and regulatory

incentives. This technology not only can capture and store CO2 in carbonate products but also helps manage solid waste. Innovative technologies based on carbon mineralization also are emerging that produce new products and provide CO2 utilization options. Sections 5.2.1–5.2.6 discuss these existing and emerging carbon mineralization approaches—carbonation of natural minerals and rocks, alkaline industrial wastes and demolition wastes, enhanced carbon uptake by construction materials, electrolytic seawater mineralization, alternative cementitious materials with increased CO2 utilization potential, and integrated carbon mineralization technologies—providing analysis of their challenges and R&D opportunities.

5.2.1 Carbonation of Natural Minerals and Rocks

As discussed in Section 5.1.2, a wide range of earth-abundant Mg- and Ca-rich natural silicate minerals are available for carbon mineralization. These silicate minerals and rocks are not as reactive as alkaline industrial wastes (e.g., fly ash, iron and steel slags, and cement kiln dust), which are generally amorphous with high surface area that increases reactivity. An exception is asbestos, which does have high surface area. Thus, carbon mineralization processes for natural rocks need to be engineered to accelerate the rate of mineral dissolution, which is often rate-limiting. This section describes pathways for carbon mineralization using natural minerals and rocks.

5.2.1.1 Current Technology

A common approach to accelerate the carbonation of natural silicate minerals and rocks is feedstock activation, which is achieved through thermal pretreatment (thermal activation) or mechanical pretreatment (mechanical activation) (Rim et al. 2020a, 2021). Thermal activation is an effective strategy to enhance the reactivity of minerals for dissolution, but it also consumes significant energy, reducing the net CO2 utilization potential (Rim et al. 2020b, 2021). Recently, researchers have started to use renewable energy to thermally treat minerals (e.g., the calcination of solid carbonates using solar thermal energy [Kelemen et al. 2020]); those technologies may be able to lower the carbon intensity of mineral activation.

Recent studies have shown that the reactivity of silicate minerals can be predicted based on their structures. SiO4 tetrahedra are the building blocks of most silicate minerals, and their connectivity or lack thereof (Figure 5-4) determines the overall structure of minerals (Ashbrook and Dawson 2016). The degree of polymerization of SiO4 provides a simple metric of connectivity and is denoted by the symbol Qn (n = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4), where n is the number of shared oxygens that “bridge” silicon in other SiO4 tetrahedra (Rim et al. 2020b). Natural hydrous magnesium silicate mineral (serpentine) consists of predominantly Q3. When it is heated beyond 600°C, new silicate structures (Q0, Q1, Q2, Q4, and altered Q3) are formed as the chemically bonded hydroxyl group (OH) is released from the mineral (Balucan and Dlugogorski 2013; Balucan et al. 2011; Chizmeshya et al. 2006; Dlugogorski and Balucan 2014; Liu and Gadikota 2018; McKelvy et al. 2004; Rim et al. 2020b). The newly formed Q structures impact the dissolution behavior of silicate minerals. Q structures can be examined using solid-state 29Si magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) techniques, as shown in Figure 5-4.

NMR (as illustrated in Figure 5-4) and XPS techniques can be employed to examine the chemical shifts within silicate structures in both unreacted and reacted minerals and rocks, facilitating the investigation of dissolution mechanisms. Rim et al. (2020b) showed that heat-treated serpentine is a mixture of amorphous phases of Q1 (dehydroxylate I), Q2 (enstatite), and Q4 (silica), as well as crystalline phases of Q0 (forsterite) and Q3 (dehydroxylate II and serpentine). The dissolution of amorphous silicate structures is significantly easier than those in crystalline phases (Rim et al. 2020b). Thus, heat activation of silicate minerals can promote the formation of Q1 (dehydroxylate I) and Q2 (enstatite) structures while minimizing Q3 (serpentine) structures to accelerate mineral dissolution for carbon mineralization.

Mineral dissolution is hindered also by mass transfer limitations caused by the formation of an Si-rich passivation layer on the surface of mineral particles (Rim et al. 2021). The Si-rich passivation layer can be removed or reduced by in situ grinding, where grinding medium is added to the slurry reactor to refresh the surface of mineral particles during their dissolution. The in situ grinding requires extra energy input. Rim et al. (2020a) found that the grinding media stress intensity, which can be used to estimate the energy requirement, needs to be optimized for the target extent of mineral dissolution enhancement (Rim et al. 2020a). Two mechanisms of physical grinding activation exist: fragmentation (which requires more energy but creates a large reactive surface area)

SOURCE: Reprinted from G. Rim, A.K. Marchese, P. Stallworth, S.G. Greenbaum, and A.-H.A. Park. 2020b, “29Si Solid State MAS NMR Study on Leaching Behaviors and Chemical Stability of Different Mg-silicate Structures for CO2 Sequestration,” Chemical Engineering Journal 396:125204. Copyright (2020), with permission from Elsevier.

and abrasion (which requires less energy but only refreshes the existing mineral surface). The in situ grinding in fragmentation mode is more effective in improving the Mg leaching rate from serpentine compared to abrasion mode (Rim et al. 2020a). The operational mode of in situ grinding should be determined based on the mineral dissolution rate (which varies for different minerals and rocks) and the energy requirement per mole of Mg or Ca extracted from the minerals.

The dissolution of minerals also can be accelerated by using Mg- and Ca-targeting chelating agents, although strong metal-ligand bonds might prevent subsequent carbonation (Gadikota et al. 2014; Park and Fan 2004). Thus, ligands with moderate binding energy (e.g., acetate, citrate, oxalate) are used to accelerate the dissolution of silicate minerals for carbon mineralization. All these methods (e.g., heat treatment, in situ grinding, Mg- and Ca-targeting ligands) can be used together to enhance mineral dissolution.

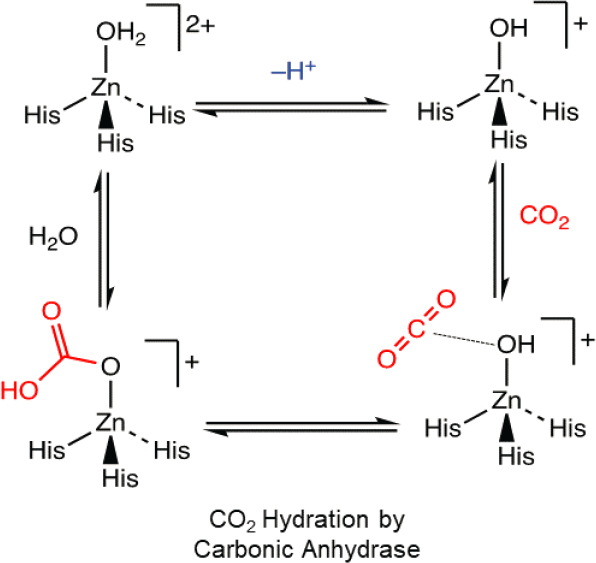

Once Mg and Ca are leached out into the solution phase, one increases the pH of the solution a pH >9 and introduces CO2 to form solid carbonates. Although mineral dissolution generally is considered to be the rate-limiting step in carbon mineralization, the hydration of CO2 (Reactions 5.1–5.3 in Section 5.1.2) may need to be accelerated as well. One strategy utilizes an enzymatic catalyst, carbonic anhydrase, which increases the rate of CO2 hydration by improving proton transfer between H2O and CO2 at a zinc ion (Zn2+) active site (Patel et al. 2013, 2014a, 2014b).

A relatively high metal cation extraction efficiency for Mg2+ and Ca2+ (>60 percent) can be achieved in 30 minutes, when the abovementioned chemical and physical enhancement strategies are used on ground mineral and rock feedstocks for mineral dissolution. The final products from the carbonation of natural silicate minerals and rocks include solid inorganic carbonates (e.g., MgCO3 and CaCO3), silica by-product, and unreacted mineral/rock residues. These materials can be used as cement replacement and clinker substitutions as discussed in Section 5.1. Besides carbonates, the solid residues after leaching can be utilized as SCMs to decrease life cycle CO2 emissions further (Hargis et al. 2021). This reactive CaCO3 is in the vaterite phase, and it achieves high compressive strength after a polymorphic transformation to stable aragonite (Hargis et al. 2021). Different polymorphs of calcium carbonates (vaterite, aragonite, and calcite) can be produced by tuning the reaction temperature and time as well as by introducing seed material to promote rapid formation of metastable carbonate phases (Zhang and Moment 2023; Zhao et al. 2023a, 2023b). The use of carbonates and by-products from

the carbonation of natural silicate minerals and rocks as construction materials can significantly reduce the life cycle CO2 emissions associated with the built environment.

5.2.1.2 Challenges

Carbon mineralization of Mg- and Ca-bearing silicate minerals has been studied and developed over the past three decades as an important carbon storage method with long-term stability because it produces chemically stable inorganic carbonates. The challenge has been the slow reaction kinetics associated with mineral dissolution and carbonation. While various methods (e.g., heat treatment, physical activation via in situ grinding, and the use of Ca- and Mg-targeting ligands) have been well studied and developed, additional challenges remain. Heat treatment and in situ grinding increase the overall energy requirement, and the use of ligands and acids adds significant costs and life cycle impacts associated with those chemicals. Because most of the carbon mineralization technologies involve slurry reactions, the water requirement for mineral dissolution and carbonation reactions is also a substantial challenge when these technologies are deployed at industrial scale.

If freshly mined silicate minerals are used for carbon mineralization, the mining, quarrying, processing, and transport costs also would be very high (Mazzotti 2005). Furthermore, the environmental impacts associated with large-scale mining and transportation of feedstocks and products would need to be addressed. Thus, it will be important to work with the mining industry to determine any potential impacts before carbon mineralization technologies can be deployed at scale.

5.2.1.3 R&D Opportunities

Mg- and Ca-bearing silicate minerals are earth-abundant and thus offer tremendous potential to help mitigate climate change by converting them to inorganic carbonates and thus durably storing carbon via carbonation. Because these processes for natural minerals and rocks will start from mining (carbonation of mine tailings is discussed in Section 5.2.2), R&D is needed to develop efficient mining processes and technologies. The use of renewable energy in mining processes also will improve the net CO2 benefit of carbon mineralization.

Mineral dissolution and carbonate formation reactions typically require acid and base, as well as chemical additives such as ligands. Thus, to the extent a particular process makes use of them, the sustainable production of these chemicals also will play a key role in the process’s CO2 utilization potential. A number of technologies are being developed to produce “renewable” acids and bases. For example, an electrochemical bipolar membrane system can produce acids and bases (e.g., HCl and NaOH) via salt splitting using renewable electricity (Talabi et al. 2017). These “renewable” acids and bases could play an important role in decarbonizing the mining industry, but significant R&D is required before these electrochemical processes can be scaled up economically. The fermentation of biogenic wastes can also produce organic acids including acetic acid and citric acid. The effect of these acids on the mineral dissolution is relevant to properly evaluate the net CO2 utilization potential of such processes.

While acids and bases are consumed during carbon mineralization, ligands may be recycled. Thus, developing efficient methods to recycle ligands and other chemical additives throughout the carbon mineralization processes will be important. Because carbon mineralization technologies consist of multiple reaction and separation steps, systems integration research to optimize the process is also of interest. A summary of RD&D needs for carbon mineralization is compiled in Section 5.3 and integrated with the RD&D needs for other carbon utilization pathways in Chapter 11.

5.2.2 Carbonation of Alkaline Industrial Wastes and Demolition Wastes

As discussed above, there is strong industrial interest in developing carbon mineralization technologies for alkaline industrial wastes such as fly ash and slag from iron and steel owing to multifaceted environmental and economic benefits, including solid waste management and decarbonization. Because these industries (e.g., power plants and chemical, cement, iron, and steel manufacturing plants) are also large CO2 emitters, carbon mineralization processes can benefit from the co-location of CO2 and alkaline industrial wastes, minimizing CO2 compression and transportation costs. While alkaline industrial wastes are often more reactive than the natural Ca- and Mg-rich silicate minerals discussed in Section 5.2.1, they can be challenged by impurities in waste streams. Thus, different

chemistries and reactor/separation systems are being developed for specific alkaline wastes. One of the emerging feedstocks for carbon mineralization is demolition wastes, which will start to play a more important role as aging infrastructure is replaced, while aiming to create a materials circularity in the built environment.

5.2.2.1 Current Technology

In addition to natural minerals, alkaline industrial by-products and wastes—including slags, fly ash, mine tailings, recycled aggregates, and reactive demolition wastes—have the capacity to form CaCO3 and MgCO3 when exposed to CO2 (Hanifa et al. 2023; Supriya et al. 2023; Zajac et al. 2022). A significant amount of CO2 (on the order of Gt per year) can be removed by combining it with alkaline industrial wastes (Pan et al. 2020; Rim et al. 2021). Moreover, this process is economically favored by converting two waste streams (i.e., CO2 from point sources and alkaline industrial waste) to generate value-added products. Therefore, a number of start-ups and corporations are actively developing technologies using this approach, aiming to produce low-carbon construction materials and foster a circular economy.

5.2.2.1.1 Slags

Slags (e.g., steel, blast furnace, and basic oxygen furnace [BOF] slags) are by-products from steelmaking industries and are rich in alkaline metal oxides (CaO, Al2O3, SiO2, MgO, Fe2O3), which can react with CO2 to produce SCMs (Juenger et al. 2019; Pan et al. 2017). The reactivity of ironmaking and steelmaking slags (as well as ashes from combustion/incineration processes) permits a wide range of possible process routes and applications, including the generation of higher-value products and greater uptake of CO2 as a carbon sink.

Ironmaking slags have been explored for their potential use in the construction industry. These tailings typically contain fine granulometry, high silica content, iron oxides, alumina, and other minerals, which make them suitable for various construction applications. Bodor et al. (2016) investigated the use of carbonated ironmaking slag (specifically BOF slag) as a partial replacement of natural aggregate in cement mortars, with key objectives to (1) stabilize free lime (CaO) in the slag, which causes detrimental swelling of the construction material; and (2) limit the mobility of heavy metals contained in the slag. To ensure the suitability of its intended use, BOF slag was crushed to suitable particle size (<0.5 mm), carbonated as a slurry in an aqueous solution of carbonic acid (to 10–16 wt% CO2 uptake), and utilized to replace 50 percent of natural sand aggregate in cement mortars. The results showed satisfactory performance for all considered aspects (paste consistency, soundness, compressive strength, and leaching tendency) of the mortar sample containing 37.5 wt% carbonated BOF slag of <0.5 mm particle size (Bodor et al. 2016).

Salman et al. (2014) produced construction materials using exclusively steelmaking slag (specifically argon oxygen decarburization slag), which was carbonated after being mixed with water only. CO2 uptake reached 4–8 wt% depending on the carbonation conditions and the compressive strength of the produced concrete containing slag surpassed 30 MPa. Leaching of heavy metals was within prescribed limits but the study highlighted the risk of metalloid leaching, as these elements are not captured by carbonate phases and rely on physical entrapment or another form of chemical sequestration to limit mobility (Salman et al. 2014).

5.2.2.1.2 Fly Ash

Coal fly ash is a by-product derived from coal-fired power plants and is the most common SCM used to react with CO2. (See Chapter 9 for a discussion of fly ash availability and its direct use in pavement and concrete applications.) It contains CaO and SiO2, which react with CO2 to form CaCO3 and silicate. Its fine particle size and high surface area result in superior reactivity compared to other untreated industrial wastes. The ultra-small particles of fly ash expedite carbonation, making them an efficient SCM. According to ASTM C618 standards, coal fly ash can be classified as two types based on its chemical and physical properties (particularly Ca content): Type C (>10 percent Ca) and Type F (<10 percent Ca) (ASTM International 2023b).

Replacing a portion of the OPC in concrete with fly ash reduces the life cycle CO2 emissions of that concrete by sequestering the reacted CO2 as carbonate, and the pozzolanic properties of fly ash enhance the concrete’s strength and durability. Pozzolanic materials are siliceous, or siliceous and aluminous, materials that are not cementitious inherently, but fine particulates of pozzolans in water react with Ca(OH)2 at ambient temperatures

to form cementitious materials. More cementitious compounds form in concrete made using fly ash cement than OPC, ultimately making it harder and more durable (Nayak et al. 2022). Concrete and mortars incorporating fly ash exhibit comparable compressive strength to conventional composites after carbonation (Bui Viet et al. 2020). The replacement proportion of SCMs has to be controlled carefully to maintain strength because too much calcium-silicate-hydrate (C-S-H) can form with extraneous addition of SCMs, leading to a deleterious porous structure in the cement (Wu and Ye 2017). Other ashes (e.g., waste-to-energy plant ashes) also can be used for carbon mineralization technologies. Furthermore, air pollution control residues (e.g., the solid reaction products and residues from the SOx scrubbers at power plants, which often contain unreacted Ca(OH)2) can be carbonated with CO2 to produce recycled aggregates; this technology has been commercialized (GEA n.d.; Hills et al. 2020).

5.2.2.1.3 Mine Tailings

Mine tailing waste continues to grow around the world, causing significant environmental impacts including water contamination. Thus, a technology that can utilize mine tailings would address multiple environmental problems. Araujo et al. (2022) view the production of construction materials as one of the main applications for recycling mine waste and a significant area of R&D in the field of mine waste management. Construction materials derived from mine waste offer several advantages, such as reducing the demand for natural resources by utilizing mine wastes generated for other industrial uses (e.g., metal recovery), minimizing environmental impacts, and providing a sustainable solution for waste utilization. In the construction industry, mine waste materials are utilized as additives in cement for manufacturing various products. One common application is the incorporation of mine waste, such as copper mine tailings, into concrete block manufacturing. The use of copper mine tailings in road- and highway-pavement concrete and brick production also has been explored. Most mine tailings can be used as filler materials for nonstructural concrete, an application for which their reactivity or Ca and Mg content is not critical. However, for SCM production, selecting mine tailings that contain significant amounts of Ca or Mg (>10 percent) is important. The processes of Ca and Mg extraction and carbonate formation would be similar to those developed for natural silicate minerals (discussed in Section 5.2.1).

Chakravarthy et al. (2020) explored the potential use of carbonated kimberlite3 tailings, a waste product from diamond mining, as a partial substitute for cement in the production of concrete bricks. The utilized kimberlite was sourced from the De Beers Gahcho Kué mine in the Northwest Territories, Canada. The carbonated kimberlite tailings were produced through a thin-film carbonation process and then were used to cast bricks. The study investigated different carbonation conditions, including varying levels of CO2 concentration, moisture content, and temperature. The results showed that carbonated kimberlite can be used as a partial replacement for cement in concrete bricks, with improvements in compressive strength observed. The study highlights the potential of utilizing mine tailings to sequester CO2 and produce sustainable building materials with lower life cycle CO2 emissions but recommends further research to optimize the carbonation process and to investigate the long-term durability of the carbonated kimberlite bricks.

The production of construction materials from mine waste offers a sustainable and resource-efficient approach to waste management in the mining industry. However, the adoption of these materials still faces challenges, such as transportation costs, considering that many mine tailings are stored or generated in remote locations. Additionally, the environmental and health implications of using mine waste in construction materials must be assessed to ensure that the materials meet regulatory standards for safety and performance.

5.2.2.1.4 Recycled Aggregates

The substitution of unconventional or recycled aggregates improves sustainability through CO2 curing, achieving compressive strengths comparable to those attained through conventional curing methods (Yi et al. 2020). Aggregates are granular materials that are mixed with cement, water, and often other additives to produce concrete, providing strength and durability. They account for 60 percent to 80 percent of the volume and 70 percent to

___________________

3 Kimberlites are high-pressure igneous rocks with a complex mixture of minerals, low in silica and high in magnesium. They are derived from the Earth’s upper mantle, in which, under the right conditions, carbon may occur as diamond, a high-pressure form. Not all kimberlites are diamond-bearing.

85 percent of the weight of concrete. Typically, aggregates are made of sand, gravel, or crushed stones, mixing fine and coarse aggregates in different proportions.

Aggregates from demolished materials can be recycled to produce fresh materials. However, recycled aggregates have a more porous structure than fresh aggregates, which results in lower compressive strength (Tam et al. 2020). Carbonation reactions offer a solution for this weakness by generating CaCO3 to fill these pores, achieved through either carbonating the recycled aggregates prior to concrete production or employing CO2 curing during the concrete-making process (Tam et al. 2020). As discussed in Section 5.1.2, there are also technologies to produce recycled aggregates via carbon mineralization, reducing the quantity of mined aggregates needed for concrete and utilizing waste CO2 from industrial processes.

5.2.2.1.5 Reactive Demolition Wastes

Demolished materials include reactive feedstocks that can capture and sequester CO2 to produce fresh concrete (Li et al. 2022a, 2022b; Zajac et al. 2021). A process is required to separate the aggregates (inert portion) and cement to use these materials efficiently (Li et al. 2022a, 2022b). The current recycling practice of using demolished concrete typically is limited to recovering the steel rebar and coarse aggregates. However, the hydrated paste phase (cement part of the demolition waste) contains desirable chemical components for fillers and SCMs (i.e., Ca, Si, Al) and is the most expensive and carbon-intensive portion of concrete. The reactive demolition waste is currently an untapped alkaline waste source but can be upcycled via emerging CO2 mineralization schemes such as direct and indirect wet carbonation. Direct carbonation would be more straightforward, but the final product is a mixture of carbonate and alumina-silica gel (Zajac et al. 2020a, 2020b), limiting its purity.

On the other hand, in indirect carbonation, where leaching and carbonation occur in two steps via a pH swing, pure products can be formed—CaCO3 (to serve as filler) and silica-rich residue (to serve as an SCM) (Rim et al. 2021). In a study that applied a two-step leaching and carbonation method to hydrated cement paste (to simulate waste concrete), the derived carbonates demonstrated comparable performance to conventional limestone filler in terms of hydration kinetics and compressive strength development (Rim et al. 2021). Furthermore, this leaching and carbonation process allows for the formation of different CaCO3 polymorphs in high purity—calcite, aragonite, and vaterite (Zhang and Moment 2023).

Owing to its needle-like morphology, aragonite was found to be an effective rheological modifier, specifically in enhancing the structural build-up behavior of cement pastes, which points to potential applications in 3D concrete printing (Zhao et al. 2023a, 2023b). The metastable polymorphs (i.e., aragonite and vaterite) stabilize in the cement-based system, thereby showing promise as functional fillers that may have benefits for other key concrete properties such as shrinkage and durability. Additionally, many of these derived carbonates likely would fall under the category of “limestone filler” and thereby adhere to current code, potentially accelerating the deployment of such carbonates. In addition to the carbonates, a silica-rich residue remains after the Ca is leached out, which can perform comparably to silica fume, a high-value SCM.

5.2.2.2 Challenges

Although the carbon mineralization potential of alkaline industrial wastes and demolition wastes is significant, the composition of these wastes is not consistent over the time, location, or processes in which they are collected. It is very difficult to develop carbon mineralization technology that can dynamically adjust processing based on the composition of incoming waste feedstock. Chemical additives (e.g., acids and ligands) need to be changed, or their concentration and type adjusted, depending on the compositions and mineralogy of waste incoming to the carbon mineralization process. For example, the presence of Fe in wastes can significantly reduce the purity of inorganic carbonate products that impact brightness, and thus, an additional separation step is needed prior to the carbonation reactor to produce highly pure CaCO3 or MgCO3 for paper filler applications.

5.2.2.3 R&D Opportunities

Of the CO2 reincorporation approaches mentioned above, the one with the largest potential to reduce CO2 emissions associated with the cement industry is the carbonation of concrete demolition waste. If waste building

materials can be used directly to produce new construction materials onsite, its circular economy could be achieved without transporting large amounts of heavy materials. While there is great potential to significantly improve the overall sustainability of the construction industry via CO2 utilization, there exists a wide range of R&D needs to develop new materials to replace carbon-intensive construction materials.

Carbonated industrial wastes can be used for clinker substitution, which involves replacing OPC clinker in concrete with SCMs. One of the most promising combinations of SCMs currently available on a global scale is calcined kaolin clay and ground limestone, where clinker substitution levels of 50 to 60 percent are being pursued (Scrivener et al. 2018). The main advantage of the clinker substitution approach is the avoidance of CO2 emissions in the first place owing to the reduced amount of OPC clinker being used. The production of ground limestone and calcined clay has associated CO2 emissions, but much reduced compared with OPC powder. As such, on a binder basis (OPC powder + water + SCMs), the limestone calcined clay cement has approximately 40 percent lower CO2 emissions compared with neat OPC binder when using 60 percent clinker substitution. With these substitution levels, the amount of CaO available for reaction with injected/incorporated CO2 will be minimal. Thus, the carbonated alkaline industrial wastes discussed in the present section should be investigated as a new class of SCMs and the overall process should be developed while maximizing net carbon storage and minimizing waste generation and mining of fresh mineral and rocks.

The ability of a material to react with CO2 and form stable carbonates depends on the amount of alkaline earths (CaO and MgO) available for formation of CaCO3 and MgCO3-type phases. As such, in addition to carbonate cement based on carbonation of pseudo-wollastonite/rankinite, an emerging R&D area is the formation of carbonates from highly alkaline industrial by-products such as steel slags (Beerling et al. 2020) (rich in nonhydraulic calcium silicate phases) and underutilized coal ashes. The availability of such industrial by-products tends to be (1) already fully utilized in concrete production as SCMs, as is the case of blast furnace slag and good quality coal fly ashes (Habert et al. 2020), or (2) somewhat limited in availability, as is the case of steel slags (190 to 280 Mt/yr globally4 [Tuck 2022]) and coal ashes in the future as the amount of legacy coal ashes decreases. However, the economic growth of different countries, particularly developing countries, and the replacement of aging infrastructures in the United States could significantly increase the production of iron and steel and lead to a continuous supply of alkaline industrial wastes. One area that requires more research for some of these industrial by-products (e.g., steel slag) is understanding the effects of carbonation on the leachability of trace elements, including heavy metals from these materials to ensure the safety of the produced construction materials.

As discussed above, one of the largest challenges of waste carbon mineralization is feedstock variability and complexity. Thus, a technology that can rapidly identify compositions and mineralogy of the feedstock would be extremely valuable. With the rapid advancement in artificial intelligence and machine learning, as well as in-line (e.g., infrared) sensor systems, waste sorting and characterization techniques can be developed and integrated into the carbon mineralization process to provide operational stability at scale.

Carbon-intensive construction materials will have to be increasingly manufactured, used, and upcycled via a circular carbon economy to minimize the use of natural resources. As illustrated in Figure 5-5, CO2 can be reincorporated back into construction material at the end of its service life and the overall process can be electrified using renewable energy (e.g., a sustainable electrodialysis strategy to create renewable acids and bases). In concrete demolition waste, reactive CaO is available in the form of C-S-H gel and portlandite (Ca(OH)2) and can react readily with dissolved CO2 in the pore solution5 to form CaCO3. The opportunity for this pathway is significant, as 7 billion metric tons of concrete demolition waste are produced each year (Krausmann et al. 2017), with the majority being directly disposed of with minimal uptake of CO2. The challenge of this upcycling process includes crushing and grinding the demolition wastes to expose the available CaO. Thus, research is needed to develop integrated physical and chemical separation technologies to minimize the energy requirements for carbon mineralization and waste upcycling. Focusing on low-energy separation pathways, such as membranes, would reduce the life cycle CO2 emissions of such processes. Design of bipolar membranes for electrodialysis that are

___________________

4 As a point of comparison, worldwide production of cement in 2022 was 3.7 billion metric tons, with 96 million metric tons produced in the United States alone.

5 Pore solution refers to the alkaline solution present in the pores of hardened concrete. The composition of the pore solution changes over the course of the concrete’s useful life and plays an important role in concrete durability. Pore solution composition influences the potential for steel corrosion, concrete spalling, and other degradations of reinforced concrete products (Diamond 2007).

NOTES: AEM = anion exchange membrane; BPM = bipolar membrane; CEM = cation exchange membrane; M = Ca or Mg. All take place in an aqueous phase between 30 and 90°C.

SOURCE: Icons from the Noun Project, https://thenounproject.com. CC BY 3.0.

stable under a wide variety of operating conditions and have high conductivity, fast water dissociation kinetics, low ion crossover, and long lifetime should be a priority.

Furthermore, to use produced carbonates and other solid products as construction materials for a wide range of applications including structural concrete, they have to be carefully tested and certified to ensure their performance. Also, new syntheses and formulation methods have to be developed for different concrete manufacturing processes (e.g., CO2 curing, three-dimensional [3D] printing). These new processes may provide applications for waste streams that previously did not have a use case; for example, work on 3D printable concrete materials has

found that the fine, powdery condition of mineralized wastes is advantageous, in contrast to traditional concrete production requiring large aggregates.

Last, a better database (based on industrial data) for accurate LCA of produced carbonate products and their different uses would be beneficial. The definition of permanence of CO2 storage in buildings and infrastructure is still being debated, so further discussions are needed to estimate the carbon storage potential of carbonates used in infrastructure to provide appropriate carbon credits. A summary of RD&D needs for carbon mineralization is compiled in Section 5.3 and integrated with the RD&D needs for other carbon utilization pathways in Chapter 11.

5.2.3 Enhanced Carbon Uptake by Construction Materials

The previous two sections (5.2.1 and 5.2.2) described how different feedstocks (natural minerals, alkaline industrial wastes, and demolition wastes) can be converted to solid carbonates and by-products via carbon mineralization and how they can be used as value-added products. This section describes other technologies that can directly enhance carbon uptake by construction materials—CO2 injection and CO2 curing. It discusses how these processes work and the fate of injected CO2.

5.2.3.1 Current Technology

5.2.3.1.1 CO2 Injection

Injection of a small amount of CO2 as gas or solid during mixing of OPC concrete has been shown to increase short- and long-term strength (Cannon et al. 2021). This is thought to be owing to the immediate formation of CaCO3 (amorphous or nanocrystalline) that then provides additional nucleation sites to accelerate precipitation of the main strength-giving phase in OPC concrete, C-S-H gel (Monkman et al. 2018). However, there is an upper limit to the amount of CO2 that can be added during mixing, beyond which added CO2 is found to be reduce compressive strength (Monkman and McDonald 2017; Ravikumar et al. 2021; Shaqraa 2024).

5.2.3.1.2 CO2 Curing

CO2 curing refers to the process used in the production of concrete and cementitious materials to accelerate the process of hardening materials in the presence of gaseous CO2. The conventional curing process uses water to hydrate and solidify the materials. During the CO2 curing process, a carbonation reaction occurs between Ca(OH)2 or calcium silicates and CO2, forming CaCO3 in the concrete matrix as shown in Reactions 5.9, 5.10, and 5.11.

| Ca(OH)2 + CO2 → CaCO3 + H2O | (R5.9) |

| 3CaO·SiO2 + 3CO2 + yH2O → SiO2·yH2O + 3CaCO3 | (R5.10) |

| 2CaO·SiO2 + 2CO2 + yH2O → SiO2·yH2O + 2CaCO3 | (R5.11) |

This process can reduce water consumption significantly in concrete production and sequester CO2 within the concrete (Monkman and MacDonald 2017; Ravikumar et al. 2021). It also increases the compressive strength of concrete owing to an optimal microstructure formation (Wang et al. 2022a).

The reaction mechanisms of CO2 curing include diffusion-controlled reactions between the hydrated reactants (e.g., hydrated Ca(OH)2 and CO2 not in slurry or solution form) in capillary channels, and a wet route involving CO2 dissolution in the aqueous phase (Wang et al. 2022b; Yi et al. 2020). CO2 curing is influenced by multiple factors, such as CO2 concentration, relative humidity, temperature, and intrinsic composition of materials (von Greve-Dierfeld et al. 2020). For example, the concentration of CO2 can affect the carbonation rates and polymorph of produced CaCO3 (e.g., calcite, aragonite, and vaterite), which may be different from natural limestone (von Greve-Dierfeld et al. 2020). Elevated CO2 partial pressure can accelerate the hardening process and lead to enhanced mechanical properties of concrete cured within a given time (Yi et al. 2020; Zhan et al. 2016).

Carbonation curing is another avenue being pursued by the cement industry as a means of reducing CO2 emissions. Carbonation curing involves exposure of OPC concrete to a CO2-rich environment shortly after it

has been poured for a duration of a couple of hours to a few days (Ravikumar et al. 2021). A number of factors influence the amount of CO2 that can be incorporated in concrete using this approach, primarily its porosity, permeability, and degree of water saturation (Winnefeld et al. 2022). The uptake of CO2 is associated with available CaO, which in general is attributed to the calcium originating from OPC powder and thus the decomposition of limestone (CaCO3). For OPC concrete reinforced with steel, there will be concerns regarding the impact of CO2 curing in reducing the internal pore solution alkalinity in the vicinity of the embedded steel. The pore solution pH of OPC concrete is found to be between approximately 13 and 14, which protects the steel and prevents its corrosion. However, CO2 acidifies this pore solution, and steel will begin to corrode below a pH of ~11.

5.2.3.2 Challenges

Unlike the carbon mineralization processes described in Sections 5.2.1 and 5.2.2, CO2 injection and curing technologies require a relatively high concentration of CO2 (e.g., >90 percent) to achieve a sufficient carbonation rate. Because CO2 is introduced to already prepared and mixed construction materials, including cement and SCMs, it has to be free of impurities like SO2 and NOx. The reliance on a stable, high-purity CO2 supplier might interrupt manufacturing if CO2 availability is insufficient. Although CO2 injection and curing technologies are relatively easy to implement because they do not require complex systems to scale up, the total amount of CO2 utilized in concrete is less than that of other carbon mineralization processes (e.g., the incorporation of solid carbonates as fillers or aggregates). Thus, technologies to further increase CO2 uptake by these ready-mix construction materials need to be developed. Also, the pH profile created by the even mixture of carbonates and unreacted cement and SCMs in concrete may lead to faster corrosion of steel inside concrete.

5.2.3.3 R&D Opportunities

With an easier scale-up process, CO2 injection and curing technologies have already been demonstrated and commercialized for a few conventional concrete industries. Because pure CO2 (i.e., dry ice or gaseous CO2) is used for these technologies, systems integration and process intensification with carbon capture processes from various sources are desired. It has been reported that CO2 curing shortens the time required to harden concrete and significantly reduces the overall energy requirement. Further development of these processes should be carried out via pilot-scale demonstrations under a wide range of reaction conditions (e.g., temperature, CO2 concentration and pressure, curing time, and concrete mix compositions) to determine the optimized process parameters and to confirm that the performance of produced concrete meets code.

As discussed earlier, the pH near steel bars inside the concrete needs to remain high to prevent their corrosion. There are concerns about depassivation of steel rebar in reinforced concrete owing to natural carbonation, where atmospheric CO2 reacts with cement hydration products (Ca(OH)2 and C-S-H) and reduces the overall pH during its service life (Stefanoni et al. 2018). Although CO2 curing is different from weathering carbonation, as it occurs at very early ages and within a short amount of time, durability concerns still remain for reinforced concrete produced via CO2 injection and curing. Studies on this aspect are few (Zhang and Shao 2016), as CO2 curing is still mostly limited to nonstructural, unreinforced elements, so more fundamental studies and pilot-scale demonstrations are needed to fill this knowledge gap regarding durability.

Fast diffusion of CO2 into the bulk concrete material is needed to maximize CO2 intake and solid carbonate formation. However, the depth of carbonation can be limited under accelerated CO2 curing conditions, where progressive carbonation from the exposed surface will lead to a denser microstructure and decrease subsequent CO2 transport into the concrete. Curing methods and conditions, as well as mix design, can impact CO2 diffusion behavior (Zhang et al. 2017), and thus, more systematic investigations are needed to scale up this technology.

While the altered pH profile within cured concrete may pose a problem with steel corrosion, this problem may be addressed by replacing steel with alternative reinforcement materials (e.g., glass fiber reinforced plastic rebar, engineered bamboo, and plastic fiber). Recently, carbon fiber and carbon nanotubes are also being tested as alternative reinforcement materials. Because these solid carbon materials can be produced via CO2 conversions described in Chapter 6, their incorporation into the construction materials could further increase the CO2 utilization and storage potential of the built environment.

R&D for new manufacturing technologies, including 3D printing that does not employ steel reinforcement, needs to be conducted for producing new construction materials via CO2 injection and curing methods. Emerging 3D printing technologies for cement-based materials eliminate the need for formwork, which can reduce labor and improve construction efficiency (Paul et al. 2018). However, to overcome the absence of formwork, the material must exhibit precise flow and solidification behavior so that it can flow during pumping and deposition but rapidly gain structure immediately after deposition to achieve shape stability (Marchon et al. 2018). Furthermore, the printed material must continue to harden rapidly to support subsequent layers and avoid collective buckling of the assembled system, as there is not formwork to protect the materials during early curing. Because concrete mixes for 3D printing have higher proportions of cement than traditional poured concrete and CMUs, products can be vulnerable to evaporation and subsequent shrinkage-induced cracking (Moelich et al. 2022). All of these challenges must be addressed to develop 3D printing of cement-based systems. A summary of RD&D needs for carbon mineralization is compiled in Section 5.3 and integrated with the RD&D needs for other carbon utilization pathways in Chapter 11.

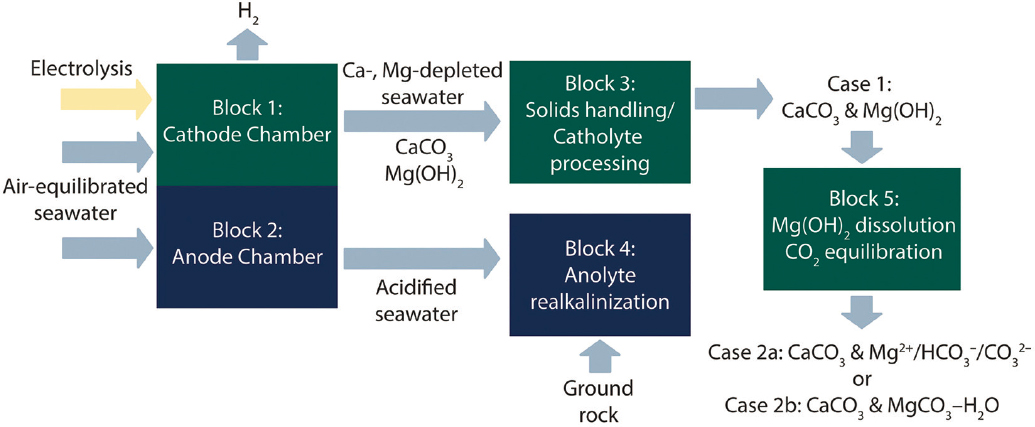

5.2.4 Electrolytic Brine and Seawater Mineralization and Biological Enhancement

As discussed above, natural minerals, rocks, and wastes derived from those mineral resources are good sources of Ca and Mg. Other unconventional resources also have been considered for carbon mineralization, one of which is an ocean-based approach. As shown in Figure 5-6, the ocean is one of the largest sinks for CO2, as it contains

NOTE: BIM = an estimated imbalance between the estimated emissions and the estimated changes in the atmosphere, land, and ocean; EFOS = emissions from fossil fuel combustion and oxidation from all energy and industrial processes, including cement production and carbonation; ELUC = emissions resulting from deliberate human activities on land, including those leading to land-use change; GATM = growth rate of atmospheric CO2 concentration; GtC = gigatonnes of carbon; SLAND and SOCEAN = the uptake of CO2 on land and by the ocean, respectively.

SOURCE: Friedlingstein et al. (2022), https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-4811-2022. CC BY 4.0.

SOURCE: Vibbert and Park (2022), https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2022.999307. CC BY 4.0.

enormous amounts of alkaline metals (concentrations of International Association for the Physical Sciences of the Oceans standard seawater: 1300 ppm Mg and 400 ppm Ca). As CO2 is dissolved into seawater, it is stored mostly in the form of bicarbonate (HCO3−) and carbonate (CO32−), the speciation of which is a strong function of pH (Figure 5-7). In recent years, researchers have started to engineer ocean chemistry to capture CO2 (direct ocean capture [DOC]) or even produce inorganic carbonates as products. In this section, electrolytic seawater mineralization is discussed as a new route to form products via carbon mineralization. A 2022 National Academies’ study, A Research Strategy for Ocean-Based Carbon Dioxide Removal and Sequestration (NASEM 2022), explores a broad range of potential ocean-based carbon dioxide removal strategies, including and beyond those described here.

5.2.4.1 Current Technology

5.2.4.1.1 Direct Ocean Capture Mineralization

Electrolysis of seawater can produce locally high concentrations of NaOH, along with H2 and Cl2 (the latter is produced preferentially instead of oxygen at most anodes). The locally high concentration of electrolytically produced hydroxide shifts the bicarbonate-carbonate equilibrium near the cathode to favor carbonate as in Figure 5-8, thereby enabling CaCO3 to form; MgCO3 is kinetically hindered from forming and requires further processing (La Plante et al. 2021, 2023). An alkaline mineral hydroxide (e.g., Mg(OH)2) formed in the process can further equilibrate with CO2 to form additional carbonates. This “continuous electrolytic pH pump” can precipitate CaCO3, Mg(OH)2, and hydrated magnesium (bi)carbonates depending on the pH conditions (La Plante et al. 2023). An electrolytic flow reactor and integrated rotary drum filter process was developed (La Plante et al. 2021).

The process is an example of integrated carbon capture and conversion, as the process uses DOC and does not require separation or purification of CO2 prior to forming the final product. A large deployment of the electrochemical DOC would require the use of the by-products (e.g., H2 and Cl2/HCl) in order to maximize the energy and atomic efficiencies of renewable energy utilization. The production of large amounts of multiple products allows the development of novel technologies, for example, the co-production of H2, O2, NaOH, and HCl from brine via electrolysis. There is a large market for green H2 and H2 can also be used along with captured CO2 to produce hydrogenated products. NaOH and HCl can be used for pH swing carbon mineralization technologies to co-recover energy-relevant critical metals, silica, and calcium and magnesium hydroxide from alkaline residues to react with CO2 to produce the respective carbonates. Advances in electrochemical processes including direct electrolysis of brine with or without the use of bipolar membranes (Kumar et al. 2019; Tian et al. 2022) are needed

SOURCE: La Plante et al. (2023), https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestengg.3c00004. CC BY 4.0.

to enable scalable deployment of renewable acid and base technologies. The produced acid can also be used to dissolve silicate minerals, neutralizing the acid and producing metal ions (e.g., Ca2+ and Mg2+) that can be returned to the ocean to replace those used in the mineralization process. In most cases, DOC mineralization processes could be applied to either CO2 utilization or CDR, the former if produced solids are collected for use as aggregates or other products, and the latter if they are returned to the ocean or spread on land.

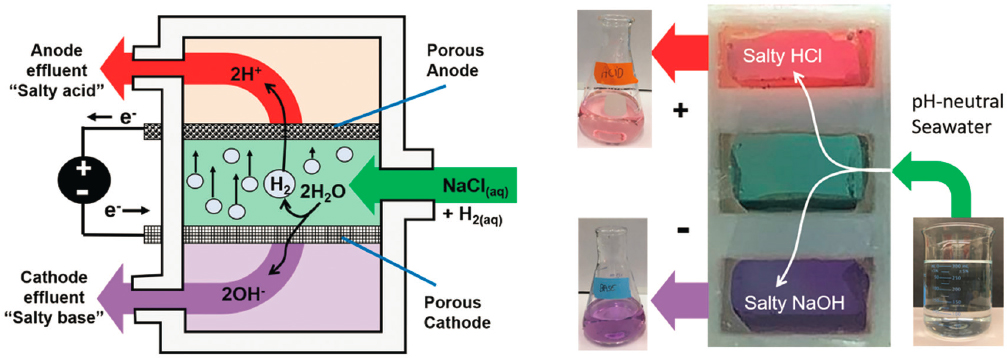

Glasser et al. (2016) showed that lightweight nequehonite-based (MgCO3·3H2O) cement can be produced with brines containing 30 wt% CO2. Mg(OH)2 generated from Mg2+ in seawater with membraneless electrolyzers can be used as a precursor in Mg-based cement, with a comparable compressive strength (i.e., 20 MPa) for a 2-day CO2 curing (Badjatya et al. 2022). Figure 5-9 shows how a membraneless electrolyzer works to split seawater into acidic and alkaline streams, or renewable acids and bases. The desalinated brines (concentrated saltwater rich in

SOURCE: Badjatya et al. (2022), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2114680119. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Mg/Ca) also have the potential to be used for metal carbonate production through aqueous mineralization (Glasser et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2019, 2020b). The use of a membraneless process to produce acid and base from brines using angled mesh flow-through electrodes (Talabi et al. 2017) may reduce the precipitation of undesired solid phases (e.g., Mg(OH)2) on the electrode surface.

5.2.4.1.2 Biologically Inspired Technologies Using Carbonic Anhydrase

Carbonic anhydrases are a metalloenzyme family found in all mammals, plants, algae, fungi, and bacteria, that catalyzes CO2 hydration and dehydration (Elleuche and Poggeler 2009). Carbonic anhydrases play a key role in the ocean’s carbon balance by accelerating rate-limiting steps of CO2 uptake by the ocean. They also are involved in CO2 homeostasis, biosynthetic reactions, lipogenesis, ureagenesis, and calcification, among other processes relevant to life in the ocean (Supuran 2016). Carbonic anhydrases are thought to mediate the hydration of CO2 through the mechanism proposed in Figure 5-10, shown with a Zn2+ metal center. By adding carbonic anhydrase into a carbonation reactor, the formation rate of solid carbonates can be accelerated (Patel et al. 2014a, 2014b). The use of pure enzymatic catalyst would be not economical owing to its costly purification steps, and thus, whole cell biocatalyst (e.g., surface display of small peptides on E-coli) has been developed to deploy carbonic anhydrase for carbon mineralization (Patel et al. 2014a, 2014b). This technology has been demonstrated at laboratory scale (Fu et al. 2018). There are few start-ups and industrial demonstrations that utilize carbonic anhydrase for carbon capture processes. Similar technologies can be used to accelerate carbon mineralization processes by improving CO2 hydration rates.

5.2.4.2 Challenges

Because ocean-based carbon mineralization technologies would intake seawater and discharge seawater after the carbonation reaction, it is critical to investigate its potential environmental and ecological impacts. Seawater

NOTE: His = histidine.

SOURCE: Modified from Vibbert and Park (2022), https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2022.999307. CC BY 4.0.

contains a wide range of ionic species, and they may precipitate out via undesired side reactions and foul the membrane and reactor systems. Monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) will play a crucial role in ocean-based carbon capture and conversion, because the amount of CO2 utilized and durably stored is more difficult to measure and monitor. MRV provides a transparent and accurate assessment of the amount of carbon being captured and stored; ensures that the technology meets the requirements of international climate agreements; and contributes to the R&D of more effective technologies (Ho et al. 2023). MRV requirements may increase the cost of ocean-based carbon mineralization technologies and their product costs.

Another challenge with ocean-based carbon capture and conversion is the local depletion of alkalinity in the ocean. This effect could impact the local ecosystem, and further, would impact the ocean’s ability to store CO2 unless alkalinity is replenished. This ocean-based technology can be integrated with the dissolution of natural silicate minerals or alkaline industrial wastes to continue the supply of alkalinity into the ocean while producing solid carbonate products.

Further improvements are needed to electrolytically supplied, local alkalinity driven metal carbonate formation—for example, by incorporating not only biocatalysts such as illustrated in Figure 5-10 but other cocatalysts that can overcome the kinetic inhibition to MgCO3 formation. Improved rates of MgCO3 formation could make better use of the more abundant alkaline earth cation (Mg) in the ocean, and simplify the DOC process by removing additional processing units dedicated to Mg (e.g., block 5 in Figure 5-8). Computational modeling has provided numerous insights into carbon dioxide mineralization, largely based on classical simulations (see recent reviews by Sun et al. 2023 and Abdolhosseini Qomi et al. 2022). Recently, high-level quantum-based dynamics simulations investigating carbon dioxide dissolution and reaction (Martirez and Carter 2023), as well as fundamental differences in free energetics and pH dependencies for Ca and Mg dehydration and carbonate formation (Boyn and Carter 2023a, 2023b), have begun to appear. Such modeling that reveals mechanisms and key influences on reactions, along with machine learning approaches to get to longer timescales and length scales, could help improve processes and catalyst design.

The availability of affordable renewable energy is also a critical requirement for electrolytic brine and seawater mineralization processes. Offshore wind energy could be a great option to integrate and other renewable energy systems (e.g., wave energy) should be considered, depending on the scale and deployment schemes of the developed ocean-based carbon mineralization processes. Offshore applications would require significant automation to minimize the maintenance issues, and the intermittency of renewable energy should be addressed during the process design and optimization.

5.2.4.3 R&D Opportunities