Carbon Utilization Infrastructure, Markets, and Research and Development: A Final Report (2024)

Chapter: 4 Policy and Regulatory Frameworks Needed for Economically Viable and Sustainable CO2 Utilization

4

Policy and Regulatory Frameworks Needed for Economically Viable and Sustainable CO2 Utilization

4.1 INTRODUCTION

Most forms of carbon dioxide (CO2) utilization will not be competitive without a price on carbon or a subsidy-based model to support a market for CO2-derived products. Recent federal subsidies signal the beginning of this growing market, but more policy is required to encourage demand for products and to support businesses entering this emerging sector. Developing goal-oriented, adaptable policy that encourages innovative technology could strengthen the impact of a carbon price. The CO2 utilization sector can become an exemplar for policy that supports a quickly changing industry. Additionally, significant opportunity exists to prioritize justice goals and drive the build-out and implementation of the CO2 utilization sector while ensuring that its outcomes are multifaceted and equitable.

This chapter addresses policy and regulatory frameworks needed to support the increased development and use of CO2-derived products, including the societal considerations that policy can incorporate into project development, siting, and selecting processes—with the assumption that there will be an implicit price on carbon for the policy recommendations made. A variety of considerations can be categorized as economic and noneconomic drivers, which can be broken down further into demand- and supply-side considerations, and sector and societal impacts, respectively (see Figure 4-1). The combined impact of the economic and noneconomic drivers can create a sector with economically viable products, a sustainable market, adaptable policy and regulations, and equitable access to sector benefits.

This chapter reviews the existing policy landscape for CO2 utilization and identifies the gaps and opportunities for policy to shape a market for CO2-derived products. It then highlights opportunities for the federal government to support business development, particularly for small businesses, to diversify the market. Next, the chapter identifies key equity and justice considerations and best practices for public discourse and community engagement to help ensure that injustices are not created or exacerbated by the emerging sector. The chapter concludes with findings and recommendations related to the policy and regulatory frameworks needed for an economically viable and sustainable CO2 utilization sector.

4.2 POLICY AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS

The committee’s first report outlined the regulation and policy that would be needed to support CO2 capture, utilization, storage, and transportation (NASEM 2023d). The committee identified key barriers and recommended solutions that policy and regulation could address, including internalizing carbon externalities (e.g., with a carbon tax) and subsidizing knowledge creation with grants for fundamental research and tax credits for pilot plants and

SOURCE: Icons from the Noun Project, https://thenounproject.com. CC BY 3.0.

demonstration units (NASEM 2023d, Finding 5.1); signaling a commitment to create a market for low-carbon technologies (NASEM 2023d, Finding 5.3); and accounting for distributional impacts of CO2 utilization projects through processes that include community engagement (NASEM 2023d, Finding 5.9 and Recommendation 5.6). The committee continues to elevate Findings 5.1, 5.3, and 5.9 and Recommendation 5.6 from its first report as critical policy considerations for the CO2 utilization sector.

This section discusses the existing policy frameworks for CO2 utilization that aim to make CO2-derived products economically viable. It reviews the economic and noneconomic drivers that exist and can be utilized as the sector builds out. It then identifies gaps in policy and makes recommendations that will support the production and ongoing market of CO2-derived products, focusing on policies that deal with both environmental externalities and economic incentives.

4.2.1 Existing Incentives for CO2 Utilization

4.2.1.1 Economic Drivers

The current cost of CO2-derived products is greater than their incumbent equivalents in all cases considered by the committee (see Chapter 2). Most of these products are identical commodities and traded on world markets. However, a key difference between CO2-derived products and their incumbent equivalents is carbon intensity (CI)—the measurement

of a product’s life cycle CO2 emissions per unit. The economic rationale for consumers becomes more complex when CO2-derived products display characteristics superior to incumbents, which provides an additional dimension of value to drive purchasing decisions beyond cost and CI (e.g., cured concrete has demonstrated enhanced structural performance compared to conventional concrete). In the absence of carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAMs)1—or other public or private policy that ascribes an economic value or promulgates a standard for CI—incentives that consider all dimensions of purchasing decisions are needed to prompt consumer demand.

Both identical substitutes and superior incumbent products are currently in the earliest stages of commercialization. Sustained demand signals and efficiency gains in production will be needed to drive down costs to approach current market prices for incumbents. To support the formation of commercial-scale markets for CO2-derived products, this section discusses two broad categories of economic drivers: demand-side tools and supply-side tools. Both need to be applied simultaneously to scale up CO2-derived products in a timely fashion and achieve meaningful market share.

4.2.1.1.1 Demand-Side Tools

Demand-side tools largely focus on CI-based thresholds for products and/or economic offsets for the purchase of CO2-derived products. The consumers targeted by demand-side tools are mostly government agencies or private sector businesses. However, individual households can benefit from tools that decrease the cost of some CO2-derived products, such as cleaning supplies.

A tool used to support demand in the private sector is procurement strategy, the purchase of upstream commodities used within a firm’s value chain based on CI. This approach has been observed in cases like “green steel,” where the European automotive industry finds it economically advantageous to pay a premium for lower-CI steel to meet customer preferences and corporate carbon climate ambitions (e.g., see Boston 2021 and Muslemani et al. 2022). However, it has not been observed for CO2-derived products, given the abatement cost associated with these products compared to other strategies to meet corporate climate commitments (Comello et al. 2023; Fan and Friedmann 2021). For example, in maritime shipping, it may be less costly to first take energy efficiency measures to reduce emissions than to consider e-methanol or other CO2-derived fuels (IRENA 2021).

Under current conditions, it is more cost-effective to pursue carbon abatement strategies other than CO2derived products to decarbonize scope emissions within a value chain, although this is industry- and brand-specific. For example, an industry standard that goes into effect in 2027 will drive demand for lower-CI aviation fuels (a scope 1 emission for the industry), especially for sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs), which can be derived from CO2 (ICAO Environment 2023). In contrast, the availability of modular concrete blocks (a scope 3 emission for the housing industry) may not increase demand in the short term if alternative emissions reduction strategies (e.g., more efficient heating and cooling, upgraded insulation, and fuel switching from natural gas to electric) remain more cost-effective (Malinowski 2023). Moreover, even in the case of low-embodied carbon structures, there are lower-cost approaches to meeting design targets than using CO2-derived products, such as material reuse (Malinowski 2023). Therefore, purchasing CO2-derived products typically is not a preferred method in the private sector, given that other strategies to abate or transfer emissions are more cost-effective.

Within the public sector, various local, state, and federal programs are creating a demand signal for CO2derived products. Across existing “green initiatives,” a few policies explicitly mention life cycle factors for product procurement (e.g., the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [EPA] Environmentally Preferable Purchasing Program [EPA 2024, n.d.(g)]; the Federal Sustainability Plan [CEQ n.d.(a)]; and Orange County, California’s Environmentally Preferable Purchasing Policy [Orange County Procurement Office 2022]). Only two federal initiatives explicitly mention CI considerations: the Federal Buy Clean Initiative—which partners with states to consolidate data sources and material standards for a more consistent market for lower-carbon materials2—and

___________________

1 CBAM is an emerging policy tool that aims to cut global and national industry emission (e.g., see EU n.d.). However, currently, CO2 utilization is not the lowest-cost approach to decarbonizing products in many cases and is therefore unlikely to be deployed as a first option for CBAM compliance.

2 Beyond existing initiatives like Buy Clean, NASEM (2023a) recommended that DOE, EPA, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology develop standardized approaches for determining the CI of industrial products, with associated labeling program for consumer awareness (Recommendation 10-6, NASEM 2023a). Additionally, EPA should establish a tradeable performance standard for domestic and imported industrial products based on declining CI benchmarks for major product families, to be determined by DOE and the Department of Commerce (Recommendation 10-9, NASEM 2023a).

the Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Utilization Procurement Grants (UPGrants) program—an economic-based incentive mechanism that provides grants to states, local governments, and public utilities to support the commercialization of technologies that reduce carbon emissions while also procuring and using commercial or industrial products derived from captured carbon emissions (NETL n.d.(b); White House 2023). The UPGrants are unique because they focus on creating a durable demand signal for CO2-derived products by lowering the relative cost of those products and offering flexibility in how grant money can be used (e.g., a contract-for-difference, auction, reverse auction, or other structure can be employed). As the UPGrants are awarded, actual costs data will be revealed and collected, which will help to inform the potential of various products derived from captured carbon emissions and shape or expand the program to induce a further demand signal.

4.2.1.1.2 Supply-Side Tools

Supply-side tools are largely focused on reducing the cost to produce CO2-derived products. The 45Q tax credit offered through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which provides $60/tonne CO2 captured and utilized, is the most well-known supply-side incentive (H.R. 5376 2022). However, the value of the 45Q tax credit for utilization is less than that for CO2 captured and permanently sequestered in geologic storage, which has a value of $85/tonne. The disparity between the two credit values is not directly ascribed to permanence of CO2 captured that would otherwise have been emitted to the atmosphere. For example, a project converting CO2 to a long-lived product would still receive a lower tax credit than a project that geologically sequesters CO2, despite the outcome of both being durable storage of CO2.

While 45Q is useful in reducing the unit economics of CO2 utilization, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) offers various cost-share grants to offset the cost of plant, property, and equipment to demonstrate and/or deploy CO2 utilization technologies at scale (H.R. 3684 2021). See Table 4-1 for a list of IIJA funding for carbon management programs and projects, totaling to about $20 billion in new funding. These grants largely fall within the carbon management funding opportunities managed by DOE’s Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management (FECM), of which up to $46 million is available to develop technologies to remove, capture, and convert or store CO2 from utility and industrial sources or the atmosphere (DOE 2022a; DOE-FECM n.d.(a)).3

Outside of these CO2 utilization-specific supply-side tools, DOE’s Loan Programs Office provides access to low-cost debt, which can significantly reduce the overall unit economics of CO2-derived products (DOE-LPO n.d.). However, a project cannot receive both a grant and a loan from DOE. To prevent a “double benefit” from occurring, project development requires careful structuring and sequencing. There is no conflict in using a federal grant or a loan in combination with the 45Q tax credit (or any tax credit for that matter) to reduce the supply cost of CO2-derived products.

4.2.1.2 Noneconomic Drivers

4.2.1.2.1 Existing Workforce and Translational Skill Sets

At present, the CO2 sourced for utilization relies largely on point-source carbon capture technologies retrofitted onto existing polluting facilities such as industrial or power plants. An analysis of carbon capture retrofits found that more than 70 percent of coal plant retrofits will occur in the near term (by 2035), while about 70 percent of gas plant retrofits will occur in the long term (by 2050) (Larsen et al. 2021). Furthermore, Larsen et al. (2021) project that retrofit operations across the industrial and power sectors in the next 15 years will create up to 43,000 on- and off-site jobs, including installation, maintenance, labor, and chemical and water treatment. See Section 4.3.3 below for more about the upstream labor needs for the CO2 utilization sector. This workforce will need to be maintained and, in some cases, grown as the facilities expand their capabilities.

Aspects of the CO2 utilization value chain parallel those in the oil and gas sector, including the siting and development of facilities to capture, maintain, and prepare a resource for subsequent phases of production, transport, and transformation of the resource to a final product or end use. These similar value chain mechanisms mean

___________________

3 DOE has a living list of funding and award announcements related to the IIJA and the IRA here: https://www.energy.gov/infrastructure/clean-energy-infrastructure-program-and-funding-announcements.

TABLE 4-1 Carbon Management Investments from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

| Description | Amount |

|---|---|

| § 40302—Carbon Utilization Program | $310 million over a 5-year period |

| § 40303—Carbon Capture Technology Program | $100 million over a 5-year period |

| § 40304—CO2 Transportation Finance and Innovation Program | $2.1 billion over a 5-year period |

| § 40305—Carbon Storage Validation and Testing | $2.5 billion over a 5-year period |

| § 40308—Regional Direct Air Capture Hubs | $3.5 billion over a 5-year period |

| § 40314—Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs | $8 billion over a 5-year period |

| § 41004—Carbon Capture Large-Scale Pilot Projects | $937 million over a 4-year period |

| § 41004—Carbon Capture Demonstration Projects | $2.5 billion over a 4-year period |

| § 41005—Direct Air Capture Technologies Prize Competitions | Precommercial: $15 million for FY 2022 Commercial: $100 million for FY 2022 |

SOURCES: Adapted from Clean Air Task Force (2021) and DOE-FECM (2022).

there is high transferability across existing professional, technical, and labor sector jobs. For example, Okoroafor et al. (2022) found that a variety of “noncore” technical skill sets—for example, project management, health and safety, and business development—in the oil and gas sector are transferrable to the carbon capture and storage, hydrogen storage, and geothermal energy sectors. Additionally, skills needed to perform extraction activities such as mining, electricity generation, pipeline construction, and manufacturing are prevalent in the fossil fuel sector (Tomer et al. 2021). If coordinated with the build-out of the CO2 removal industry, the CO2 utilization sector could develop in a more streamlined and accelerated manner through a reliance on similar workforces. (See Finding 4-2.)

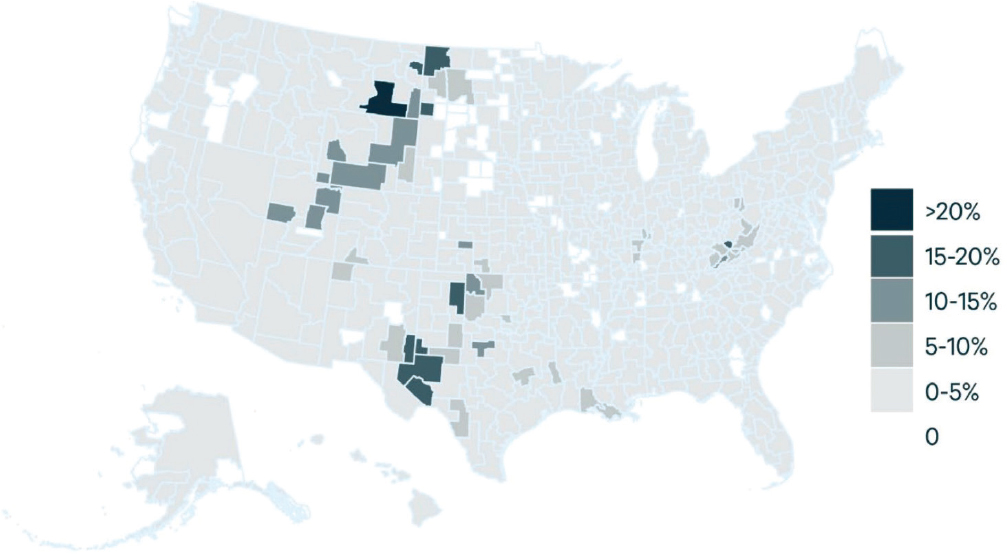

The geography-specific nature of fossil infrastructure and jobs is also an existing incentive for the budding CO2 utilization industry. Because point-source CO2 capture relies on heavy-emitting industries, most of the jobs requiring workers with transferable skills from oil and gas will likely exist in similar locations. A survey of oil and gas workers found that Texas, Louisiana, and California have the most workers and residents in the United States in addition to 131 petroleum refineries (as of January 2022) (Biven and Lindner 2023). Furthermore, in states considered for carbon management infrastructure (e.g., North Dakota, Oklahoma, Texas, West Virginia, and Wyoming), fossil-based jobs represent a significant portion of the labor force within smaller counties (30 to 50 percent of all workers are employed in the fossil fuel industry) (Tomer et al. 2021). Carbon management investments can be made in counties where transferable skills and expertise from fossil fuel jobs exist to scale up projects with the speed needed for the energy transition to net zero (Greenspon and Raimi 2022; Pett-Ridge et al. 2023; see Figure 4-2).

Workers in the oil and gas community may be eager to find work that builds on existing skill sets in locales where they have been historically successful, which could bode well for the carbon management industry, and therefore CO2 utilization. Biven and Liner (2023) found that survey respondents would transition to jobs in well plugging and abandonment (34 percent), pipeline removal (30 percent), or carbon capture and storage (CCS) (15 percent) if skills training and education were free. Increasing the workforce’s awareness of declining opportunities in oil and gas, offering more training focused on developing translational skills, and ensuring that these opportunities are accessible to all would support CO2 utilization workforce pathways. (See Finding 4-2.)

4.2.1.2.2 Environmental Justice Considerations

The federal government’s response to environmental justice (EJ) began in 1994 with the Executive Order on Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations (E.O. 12898 1994). Over the next decade, EPA (e.g., the National Environmental Policy Act [NEPA] and Considering Environmental Justice During the Development of a Regulatory Action) and the establishment of EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice advanced federal EJ considerations (CEQ 1997; EPA 2010). Simultaneously, several states established task forces, commissions, advisory boards, and state offices to address the environmental injustice experienced by minority, low-income, and Indigenous populations. The early adopters include California, Colorado,

NOTE: A commuting zone uses a hierarchical cluster analysis and U.S. Census Bureau data to reflect where people live and work, combining the nation’s counties into 658 groupings.

SOURCE: Greenspon and Raimi (2022).

Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington (National Conference of State Legislatures 2023).4 More recently, the robust response of DOE to meet the goals outlined in the Justice40 Initiative creates specific areas of interest through which action eventually can incentivize the continued development of CO2 utilization (E.O. 14008 2021; White House n.d.(b)). DOE identified eight policy priorities to guide the implementation of EJ across deployment of their programming (DOE n.d.(d)). Of those eight, the carbon management value chain and CO2 utilization infrastructure have the potential to impact and be impacted by the following:

- Decrease environmental exposure and burdens for disadvantaged communities.5 Low-income communities or communities of color are disproportionately impacted by air pollution and thus are more likely to experience adverse health effects (EPA n.d.(c)). Therefore, the potential for carbon capture equipment to directly address co-pollutants has drawn attention in the larger carbon management and EJ conversation. DOE’s Justice40-covered programs, if implemented as intended, may result in a larger build-out of carbon management infrastructure that can support CO2 utilization and decrease air pollution in affected communities (See Section 4.2.1.2.3.)

___________________

4 See NASEM (2023a, 2023e) for a discussion about current state and federal initiatives to advance the energy transition through holistic programs that seek multifaceted outcomes, including advancing EJ through risk-management planning for stormwater management (e.g., see LA SAFE 2019); applying prices to industrial pollution (e.g., see Cap-and-Invest n.d.); creating working groups to advise policy related to EJ communities (e.g., see IWG 2021 and New York State 2022); and evaluating policy impacts on disadvantaged communities (e.g., see DOE 2023).

5 Under Justice40, a “disadvantaged community” is a community that is marginalized, underserved, and overburdened by pollution (White House n.d.(b); see also Box 4-3 below).

- Increase clean energy enterprise creation and contracting in disadvantaged communities. Owing to the nature of the carbon management value chain and its economics, there are limited opportunities for smaller players, including minority-owned businesses, to partake in the build-out of this sector. The development of small minority and disadvantaged business enterprises has the potential to bring economic development to a disadvantaged community and diversify the carbon management value chain. In particular, the development of these enterprises can create diverse CO2 utilization opportunities.

- Increase clean energy jobs, job pipeline, and job training for individuals from disadvantaged communities. Both racial minorities and women are underrepresented in the U.S. clean energy sector, and racial minorities are less likely to hold executive or leadership roles (DOE-OEJ 2023; E2 et al. 2021; Lehmann et al. 2021). To support the carbon management sector, between 390,000 and 1.8 million jobs are projected to be created in raw materials, engineering and design, construction, and operation and maintenance (Suter et al. 2022). The expansion of the carbon management sector provides an opportunity to diversify the workforce with a focus on offering workforce development opportunities to underserved communities.

It has yet to be determined if Justice40 is a durable policy or if 40 percent of benefits is an achievable target for federal investment, but significant opportunity exists to prioritize these EJ goals to drive the build-out and implementation of the CO2 utilization sector, while ensuring its outcomes are multifaceted and more equitable. For example, carbon management falls largely under the climate change and clean energy topics of Justice40, but the administrative motivation to create a robust workforce and diversify supply chains also provides incentive to build up CO2 utilization opportunities in regions transitioning from oil and gas production. Policies that seek to enshrine EJ considerations into CO2 utilization investments can support the emerging sector in collecting and reporting the outcomes of investments for adaptive management (see Section 4.2.2.1) and by providing direct benefits to overburdened communities (see Section 4.4.3.3).

4.2.1.2.3 Health Co-Benefits from Carbon Management

Once emitted, greenhouse gases (GHGs) last up to thousands of years in the atmosphere and, in addition to climate change, contribute to adverse environmental effects, including air pollution, which leads to an estimated 53,200–355,000 premature deaths annually in the United States (EPA 2022; Mailloux et al. 2022; Vohra et al. 2021). Impacts of air pollution are disproportionately experienced across the nation. For example, near source pollution6 has been found to lead to higher exposures to air contaminants, negatively impacting public health in these areas (EPA n.d.(e)). Emissions mitigation approaches—including carbon capture, focus on reducing emissions, and removing GHGs from the atmosphere—are expected to benefit human and public health. (See Finding 4-3.) Furthermore, replacing processes and products that emit GHGs with low-carbon alternatives will prevent the continued release of GHGs into the atmosphere. Box 4-1 summarizes a study conducted to analyze the potential health benefits from deploying carbon capture technologies on certain facilities.

Providing quantitative data to affected communities and policy makers about how carbon capture technologies can reduce criteria air pollutant emissions, and consequently benefit human health, will further inform the dialogue that is necessary to deploy carbon management technologies (see Section 4.4.1). Furthermore, the results of future-looking reports describing expected health benefits from carbon management can support deployment of CO2 utilization technologies at the scale necessary to meet climate objectives. (See Recommendation 4-2.)

4.2.2 CO2 Utilization Policy Gaps

Climate change policies need to be stable and durable such that investments and incentives are maintained while also evolving with new information and changing conditions (NRC 2010). Policy uncertainty hinders investment and adoption of technologies and limits otherwise profitable investments (NASEM 2023d, Finding 5.3). However, because developing a net-zero or circular economy at the scale required to address climate change is a

___________________

6 Living near sources of air pollution, including major roadways, ports, rail yards, and industrial facilities.

BOX 4-1

Potential Health Benefits from Deploying Carbon Capture

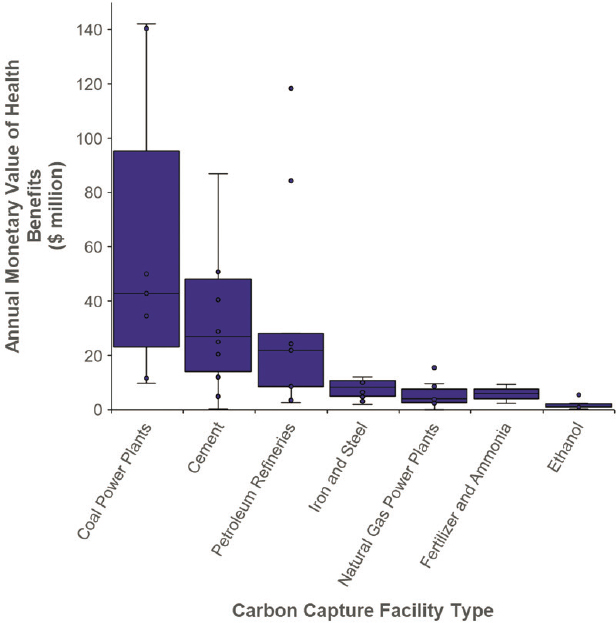

Bennett et al. (2023) reviewed 54 facilities in seven industries—cement, coal power plants, ethanol, fertilizer and ammonia, iron and steel, natural-gas power plants, and petroleum refineries—to estimate regional air quality and health benefits that would result from carbon capture deployment. The study used the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Co-Benefits Risk Assessment Health Impacts Screening and Mapping Tool (COBRA)—which predicts health outcomes on adult and infant mortality; nonfatal heart attacks; respiratory and cardiovascular-related hospital admissions; acute bronchitis; upper and lower respiratory symptoms; asthma exacerbations and emergency room visits; minor restricted activity days;a and work loss days—to identify the air quality and health benefits through the combined removal of CO2, NOx, SO2, and PM2.5 via carbon capture. Looking at different regions across the United States, carbon capture on mid-Atlantic facilities is projected to provide the highest reduction in asthma exacerbation and mortality (Bennett et al. 2023). COBRA also was used to find the economic value associated with the changes in health impacts—that is, the monetary value of health benefits from carbon capture. As shown in Figure 4-1-1, the largest monetary value of health benefits is estimated to come from deploying carbon capture on cement, coal, and petroleum refineries. This outcome can be used to inform priority carbon capture investments when the investment goal is to reduce adverse health impacts from emissions of CO2 and other pollutants. However, the study did not consider additional climate benefits from CO2 removal or additional economic benefits from installing and maintaining carbon capture technology, both of which could be additional drivers for carbon management.

NOTE: The circles represent the total average value of health benefits calculated for each of the 54 facilities studied.

SOURCE: Based on data from Bennett et al. (2023).

__________________

a Defined as days on which usual daily activities are reduced, but without falling into work absenteeism.

novel task, there is limited ability to anticipate the ways in which this process can fail, which adds difficulty to policy design (NASEM 2023c). The lack of adaptable policy serves as barrier to the adoption of carbon management infrastructure and CO2 utilization by creating roadblocks to economic development. For example, there are legislative barriers to updating the 45Q tax credit to include a variety of eligible technology pathways, development, and deployment.

As it stands, the main policy mechanisms for the CO2 utilization sector are tax credits, permitting and regulatory frameworks, and large omnibus legislation—all of which under the current system are slow moving and difficult to modify, especially when bipartisan consensus is required. (See Finding 4-4.) Adaptable policies can serve the CO2 utilization sector by matching the pace of market and infrastructure development, and the science as it evolves. Adaptive management, an iterative learning process that produces improved understanding and management over time, is critical to the development of flexible policies (NASEM 2023c). Adaptive management can help identify and avoid unintended consequences like disincentivizing certain capture and removal pathways, while also leading to broader societal acceptance. For example, as more CO2 utilization technologies and products become commercially available, there will be more data about the direct and indirect impacts experienced by the general public and communities hosting infrastructure. Analysis of these data can be used to modify CO2 utilization policy to avoid unjust consequences to communities and the environment. The following section outlines how policy for CO2-derived products can be designed and implemented to support and adapt to an emerging market and identifies potential economic and noneconomic tools to address gaps and barriers. (See Recommendation 4-3.)

4.2.2.1 Economic Tools

As discussed above, the current policy portfolio incentivizes CO2 capture and production of CO2-derived products through tax credits such as 45Q and 45V that lower the cost of supply.7 However, it lacks demand incentives for CO2-derived product uses or markets, especially relative to other carbon abatement approaches. The lack of a sufficient cost benefit for use of CO2-derived products prevents uptake. For example, under current policies and prices, the use of SAF from captured CO2 is more expensive than continuing to use aviation fuel derived directly from fossil sources (Bose 2023). Without financial justification or specific policies incentivizing the use of CO2-derived products, there will be no economic rationale to drive market adoption. (See Finding 4-1 and Recommendation 4-1.)

Policy needs to create the conditions to both lower the costs and market frictions to produce CO2-derived products and decrease barriers to demand, at least initially so that a minimal industry can be established. The latter has an analogy in the rise in demand for carbon-free electricity, driven by state-level policies to achieve increasingly less carbon-intensive generation. The rise in demand is accelerated by increasing electrification of economic sectors, like transportation through incentives for and adoption of electric vehicles. The direct policy target for clean grids coupled with increased demand for electricity is creating an enormous demand for the build-out of generation sources like solar and wind energy (e.g., see Motyka et al. n.d. and Wilson and Zimmerman 2023). Economic tools for the consumption of products include policies that support cost parity for consumers between CO2-derived products and their carbon-intensive alternatives. This section outlines how economic tools can support CO2 utilization development, including tools that encourage product uptake.

4.2.2.1.1 Energy Mix Uncertainties

There is still significant need and opportunity to grow the zero-carbon electricity share; in 2023, 60 percent of electricity generated by utility-scale facilities in the United States was from fossil fuels (e.g., coal, natural gas, petroleum), while 21 percent was from renewable energy, and 17 percent was from nuclear energy (EIA n.d.). Without first decarbonizing the energy system, an emerging CO2 utilization sector using CO2 sourced from carbon capture or removal strategies could be reliant on fossil energy, preventing the desired impact on the nation’s climate goals from a life cycle assessment (LCA) perspective. The U.S. grid must continue to diversify while research and

___________________

7 The 45V tax credit for clean hydrogen production has a base rate of $0.60/kg of qualified clean hydrogen produced (H.R. 5376 Sec. 13204).

development (R&D) on low-carbon technologies seeks ways to reduce energy requirements. Both diversification of the U.S. energy portfolio and R&D will support a CO2 utilization sector that does not rely on fossil fuel combustion.

Recent U.S. legislative vehicles (e.g., the IIJA and the IRA) contain opportunities that encourage the build-out of renewable energy, including investment and production tax credits for installing solar and wind technologies, geothermal, tidal, and hydroelectric energy, and technology agnostic tax credits for clean energy production and investment (EPA n.d.(f)). Global projections show that renewable energy is becoming cost-competitive with fossil fuels, with around 187 gigawatts of all newly commissioned renewable capacity in 2022 having lower costs than fossil fuel–fired electricity (IRENA 2023). Nonetheless, a continual push to decarbonize the electricity mix is needed to develop an ethical and climate-impactful CO2 utilization market that is less reliant on fossil energy production, providing opportunities for lower-CI pathways.

Regardless of how the carbon capture, removal, and utilization value chain acquires energy and whether the energy is low-carbon, the cost of electricity may be high if facilities do not have access to a wholesale utility-regulated market. The committee’s first report discussed how uncertainty around the cost of electricity will influence CO2 utilization market growth by directly impacting the potential to develop a CO2 value chain (NASEM 2023d). It also identified that clustering energy supplies (i.e., hubs) could be more cost-effective for carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) processes and less likely to negatively impact other resources (NASEM 2023b).

4.2.2.1.2 Product Certification Processes and Reporting

Catalyzing CO2 utilization markets via federal procurement necessitates clear standards and regulation of use for these products. The programs and policies encouraging procurement of CO2-derived products do not yet have the transparency needed to advance procurement, including the creation of pilot programs or standardization guidelines. EPA has taken steps toward transparency with the Reducing Embodied Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Construction Materials and Products grant program, which helps businesses develop and verify Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs),8 and create user-friendly standardized labels for products (GSA n.d.(b)). Grants are awarded to projects that fall under five categories, including projects that develop robust, standardized product category standards and projects that support EPD reporting, availability, and verification; standardization of EPD systems; and EPD integration into construction design and procurement systems (GSA n.d.(b)). Grant awardees can help standardize the CO2-derived product industry by providing transparency on standardized data collection and analysis processes and developing tools and resources for EPD disclosures. However, further policy to support widespread adoption and standardization of CO2-derived products is necessary.

4.2.2.2 Noneconomic Tools

This section outlines the noneconomic policy tools that can support CO2 utilization development—namely, common carrier status, clarity regarding LCA standards, building materials standards, and workforce development.

4.2.2.2.1 Absence of Common Carrier Status Rules for CO2 Transportation

Robust siting frameworks will be needed as demand for CO2 transport infrastructure increases to support the sector. Historical trends for natural gas and electricity have shown that increased demand led to the development of regulatory frameworks for approving and evaluating infrastructure projects (Brown et al. 2023). State and federal agencies have been granted clear jurisdiction over siting gas pipelines and electricity transmission and have developed processes that are well defined, but not always streamlined. However, CO2 pipelines may pose greater permitting challenges than gas pipelines or electricity transmission (Brown et al. 2023). For CO2 midstream, there is uncertainty regarding common carrier rules and status9 for interstate transportation because common carrier

___________________

8 An EPD is an environmental report that provides that quantified environmental data using predetermined parameters and environmental information is consistent with ISO 14025:2006 (EPA n.d.(d)).

9 Common carrier status means that conveyance of CO2 for a fee is made open to the public by the operator, as opposed to private operation, where only specific actors may access such infrastructure.

status varies by state. It is unclear whether the entire pipeline is required to act as a common carrier when it passes through a state with common carrier requirement and a state without the requirement.

The lack of clear rules surrounding pipeline transportation of CO2 may not be an immediate constraint on market growth, but it will limit the unit economics and ongoing market maturity if not resolved as soon as possible. A significant challenge associated with common carrier status is that pipeline owners have concerns about the chemical composition and potential reactivity of what others may inject for transport in their infrastructure—especially given the many potential sources of CO2. Chemical impurities can lead to mechanical and metallurgical failures, which would be the responsibility of the pipeline owner. There is a space here for some type of policy or regulatory mechanism to certify CO2 streams in a common carrier system. However, currently no agreed-upon approach exists to common carrier status that allows certification to happen, and more intentional work is needed to address this.

4.2.2.2.2 Clarity Regarding Assessment Standards

Owing to the myriad pathways CO2 utilization can take, there is an ongoing discussion around monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) and how to standardize “best” practices. Because these practices could change with the development of new techniques and technologies, creating adaptable MRV frameworks is increasingly important.

As key aspects of MRV, LCAs for CO2 utilization processes need to be better defined and standardized. LCA requirements often lack widespread adoption or clarification outside of these frameworks for federal tax credits or funding opportunities. For example, after an open comment period, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS 2021) determined that an LCA of GHGs—consistent with ISO 14044:2006—has to be submitted in writing and “either performed or verified by a professionally-licensed independent third party,” along with the third party’s documented qualifications for 45Q tax credit applicants.10 Ultimately, the LCA needs to quantify the metric tonnes of qualified carbon oxide captured and permanently isolated from the atmosphere or displaced from being emitted into the atmosphere through use of eligible processes. Another example is DOE’s Carbon Utilization Program, which requires eligible entities to show significant reductions in life cycle GHG emissions for CO2-derived products compared to incumbent products using the National Energy Technology Laboratory’s (NETL’s) LCA Guidance Toolkit as a baseline (DOE n.d.(b); NETL n.d.(a); Skone et al. 2022). Creating standardized processes around LCA requirements and expectations is difficult, and nearly impossible if the purpose is not for a federal credit or funding opportunity.

There are also gaps in the use of social life cycle assessments (s-LCAs), which consider social impacts from a more quantitative perspective, as a part of federal frameworks or other standardized processes.11 s-LCAs, along with other ways to integrate equity and justice concerns, are not comprehensive or a replacement for community engagement. However, the results of the assessment may enable clear communication of social benefits or the pathway’s role in climate mitigation strategies in a way that a more traditional LCA may not. Therefore, these frameworks could play a role in addressing public acceptance issues while integrating social considerations into the traditionally high-level quantitative MRV discussion. Clarity around these systems and consistent regulatory and permitting processes will allow for more transparency among research entities, industry, government, and the public, while creating easier pathways for integrating CO2 utilization processes and products in our economic system. See Chapter 3 for more information about LCAs and s-LCAs.

4.2.2.2.3 Flexible Policy for CO2-Derived Building Materials

Strong demand signals exist to produce CO2-derived building materials—concrete, carbon black additives, and drywall—owing to incentives and requirements for low-embodied carbon in new buildings. These new materials

___________________

10 For these requirements, the IRS defined life cycle GHG emissions using the cradle-to-grave boundary, considering the entire product life cycle from raw material extraction until end of life (IRS 2021).

11 See Ashley et al. (2022) for a proposed equity assessment framework that provides sufficient quantitative information about the effects of federal legislation to inform federal processes.

seek to reduce carbon emissions and minimize adverse environmental impacts from the construction industry. The increasing number of patent applications for CO2 utilization technologies (a roughly 60 percent increase internationally between 2007 and 2017) reflects the interest from researchers and industries, with investment facilitating technologies to be developed at scale (Norhasyima and Mahlia 2018).12 The committee’s first report identified that CO2-derived construction materials would motivate the “testing and validation of the new materials, creation of new environmental product declarations, and adaptation of building codes and standards” to support the consumption of these products (NASEM 2023d, p. 64).

Innovative solutions are emerging to address these challenges from different perspectives, such as using renewable energy to produce clinkers for cement, applying alternative materials with lower carbon footprint, capturing CO2 produced from cement plants, and upcycling construction and demolition materials. (See Box 4-4 below for information about concerns expressed by construction professionals about CO2-derived materials.) In addition to supporting R&D for construction materials, future policy could incentivize the development of building codes and regulations that are flexible and adaptable as new CO2- and coal waste–derived materials are validated for use in buildings. For example, Bowles et at. (2022) provides sample language for building codes that could decrease the carbon impacts from the construction industry and support low-CI business models.

4.2.2.2.4 Workforce Development Considerations for Policy

As discussed above, there is an abundant workforce opportunity for carbon management infrastructure as the sector builds out and new prospects for career pathways develop. CO2 policy design could incorporate the following workforce development considerations:

- Facilitate localized development of workforce opportunities. Jobs are frequently cited as an economic benefit to bring communities on board with new projects and investment, position the United States as a leader in manufacturing, and reduce GHG emissions (e.g., see Larsen et al. 2021 and White House 2021). Developing workforce standards and requirements can create measurable benchmarks that can be strategized around. Furthermore, a dedicated commitment at a larger level of workforce development needs to occur simultaneously with a skill building framework implemented through local actors (i.e., providing classes and certifications, and facilitating job placements through a national public university, community college, or trade school) (Coleman 2023).

- Balance training the new workforce with upgrading the existing workforce. Skills development is integral to bringing new laborers into the workforce and supporting incumbent workers through the transition. Strategies that will reach both groups of workers include targeted outreach for occupation types and cross-industry partnerships and apprenticeships (Zabin 2020). Opportunities to grow the sector include targeting young people interested in the green economy, which can benefit youth in underserved communities to provide them with a variety of career trajectories. For example, future iterations of the American Climate Corps could include opportunities around carbon management (White House n.d.(a)). Reaching both groups of workers will take intentional and effective outreach to meet the specific needs of the present and future workforce.

4.3 MECHANISMS FOR BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT

Discovering, developing, and commercializing CO2 utilization processes and products are necessary as the nation transitions to a net-zero economy. This section highlights various considerations for business development, including market fit and access, available federal resources and programs, and potential workforce uncertainties.

___________________

12 See Chapter 2 for more about the market for cement and construction aggregates, Chapter 5 for more about CO2-derived building materials and the environmental impact of the processes to produce them, and Chapter 9 for more about coal waste–derived building materials.

4.3.1 Market Fit and Access for CO2-Derived Products

CO2-derived products have to be considered on a continuum with respect to market fit—the alignment between the specifications of the CO2-derived product and the needs and preferences of the purchasing consumers and market access—the ability of a product to enter and operate in a particular market successfully (i.e., in an economically sustainable manner) (Aaker and Moorman 2017). This section considers elements of market fit and access, including upstream and downstream partners and commodity gatekeepers.

4.3.1.1 Market Fit

Market fit in the context of CO2-derived products largely relies on the ability of products to satisfy the claims that they have lower CI than otherwise functionally identical products. For example, SAFs will not be chemically identical to current jet fuels but will have the same functionality and lower CI. Market fit becomes more complex in situations where product performance beyond CI is altered (e.g., concrete blocks that have been cured with CO2 and thus exhibit greater load-bearing characteristics). Such cases create a new submarket in which customers appropriately pay for functional performance that is greater—or less—than the baseline.

In strict replacement cases, the market fit of CO2-derived products mostly has been established already by the incumbent. Projections for the evolution of existing markets have to be considered to determine the long-term viability of the CO2-derived product. In cases where new products cannot be strictly considered replacements, product–market fit analysis has to be continually conducted to determine if—and at what point in time—a sufficiently sized demand signal will emerge to support the economic case of a CO2-derived product. It may take time for a unique and durable demand signal for new products to appear, as prospective customers need to accumulate knowledge and experience the product. For example, for CO2-cured concrete blocks, customers must determine if the price premium justifies a one-for-one replacement with existing markets; if new applications can be found that push out incumbent solutions; and if new products perform in the field as expected given standards tests. These considerations require time and experience on the parts of both customers and producers to make informed judgments about the product.

Co-piloting and partnerships are crucial for products to move up the adoption-readiness level ladder. Key upstream partners for CO2-derived product development include CO2 supply, specialized capital equipment providers, and specific co-input providers (e.g., providers of emissions-free electricity and clean hydrogen). While production volumes are currently small and uncertain for most CO2-derived products, key downstream partners are the direct customers that will help prove the commercialization and business case of the company producing the CO2-derived product. Such agreements are especially beneficial for commodity products where consistent, intentional effort will be required to make the CO2-derived product relatively cost-competitive with the incumbent that has decades of accumulated knowledge, resources, and market access (DOE n.d.(a)). At-volume, predictable demand over a long timeframe supported by a creditworthy off-taker creates the conditions for cost reductions and market adoption of CO2-derived products (e.g., see Saiyid 2023).

For the CO2 utilization company, a partnership agreement provides predictable demand over a long period, which could substantially support capital and operational planning, and a meaningful production/volume target that through accumulated learning effects, know-how, and value-engineering could reduce unit costs. In a sense, a downstream buyer’s contract could pave the way for cost reductions in a product, not only for the company with the contract but also for other customers. This, in turn, could create greater demand for products like SAFs (bolstered in part by the International Civil Aviation Organization’s emission targets), leading to wider market adoption. Continued engagement between upstream and downstream partners will support both the supply and demand for CO2-derived products, thus setting the foundation for a CO2 utilization market.

4.3.1.2 Market Access

Market access relates more to external factors and conditions beyond demand for product features, such as regulatory, legal, competitive, and economic factors that affect product entry into a market. Depending on the product and sector, businesses introducing CO2-derived materials will need to identify and address the relevant gatekeepers to different commodity markets to gain commercial traction (Ahn 2019). For example, adherence to

management requirements such as international quality management standards (e.g., see ASTM International n.d. and ISO 2015) and national chemical purity grading (e.g., see P.L. No. 94-469 1976 and Schieving 2018) assure customers of product reliability. Other gatekeepers for all CO2-derived products include:

- Price: In the absence of sufficient demand driven by incentives or strategic differentiation strategies, price will be the most salient factor affecting market access. Included in this is the concept of margin (price minus cost), which must be sufficient to keep suppliers economically motivated and allow for reinvestment in product improvements. CO2-derived products will need to have competitive prices, while maintaining adequate margins, to access commodity markets, which are differentiated (e.g., the price of fuels in California versus Texas may create an opportunity for CO2-derived fuels in the former).

- Volume: In commodity markets, volume and production volume certainty are other gating factors to market access. Downstream users of commodities generally optimize their processes around a guaranteed supply through multiple vendors to increase cost efficiency and capacity utilization. Producers of CO2-derived products will either need the ability to supply sufficient volumes at the onset of entering a market to satisfy procurement needs of customers or have a clear pathway to achieving such through a partnership with an offtaker.

- Quality: For a commodity product to be considered marketable, certain standards have to be achieved—typically, a combination of presence or absence criteria and/or tolerance bands with which the product has to comply. For example, the ASTM has several standards specifying, testing, and assessing the physical, mechanical, and chemical properties of plastics that CO2-derived products would be required to meet.

- Distribution channels: Depending on the product, distribution channels can take the form of commodity exchanges, wholesalers and distributors, brokers and agents, or government agencies. Each type is comprised of multiple actors with their own requirements for production volumes, price, insurance, hedging mechanisms, and quality audits. The factors affecting market access for new products are more complex, given the likely need for new submarket formation.

4.3.2 Resources for Emerging CO2 Utilization Businesses

4.3.2.1 Opportunities Through Federal Funding and Programs

CO2 utilization may use only a fraction of the total capturable CO2 otherwise destined for geologic sequestration, as discussed elsewhere in this report. Several funding opportunity announcements (FOAs) support carbon management interfacing with CO2 utilization, including those for the Regional Direct Air Capture Hubs (DOE-FECM n.d.(b)) and Carbon Capture Demonstration Projects Program (DOE-OCED n.d.). Despite being large in sum, these FOAs may not be the best source of funding for commercializing CO2 utilization because of focus and time lag to produce usable CO2. For example, the FOA for Carbon Management is positioned to help demonstrate conversion technologies, but the funding is more similar to R&D than commercial demonstration because it is spread across numerous pathways (DOE-FECM n.d.(c)). Moreover, this funding is unlikely to be sufficient for CO2 purchase for demonstration purposes.

The need for a demonstration project to claim the available tax credits incentivizes the development of CO2 utilization demonstration partners. The IIJA contains many funding opportunities to support the build-out of CO2 utilization infrastructure and R&D on CO2-derived products (see Table 4-1). For funding to be appropriately used, businesses will need to know the application and reporting criteria to secure funding. Additionally, to take advantage of multiple funding opportunities at once, multiple businesses develop partnerships and site facilities within the same region (i.e., hub design infrastructure). For example, program funding can be used to set up demonstration hubs centered close to ethanol production facilities, which would allow CO2 utilization to be demonstrated using carbon capture technology that is already commercially proven and available. The CO2 captured at these hubs would be eligible for the $60/tonne (or $130/tonne CO2 captured using direct air capture [DAC] technologies) tax credit through 45Q, and there is no requirement to geologically sequester. Given that the cost of CO2 capture from an ethanol facility is $0–$55/tonne (Bennett et al. 2023; GAO 2022; Hughes et al. 2022; Moniz et al. 2023;

National Petroleum Council 2019),13 a CO2 utilization demonstration hub centered close to ethanol production could offer the CO2 needed at zero cost. Developing demonstration partners and using hub designs when possible can stretch grant funds by eliminating operational costs from CO2 utilization unit economics. See Chapter 10 for more on CCUS infrastructure development opportunities.

4.3.2.2 Federal Programs for Building Knowledge About and Skills for CO2 Utilization

Federal agencies provide business leaders and stakeholders the opportunity to answer questions about proposed programs through various mechanisms like Requests for Information (RFIs) in order to alert the agency to gaps and opportunities in the sector. Frequently, RFIs are used to identify typically underrepresented stakeholders for collaboration, with the purpose of requesting feedback from a variety of stakeholders “all while considering environmental justice, energy transition, tribal, and other impacted communities” (DOE-FECM 2021, p. 3). Responses from small and disadvantaged CO2 utilization businesses, declaring the need for attention and collaboration, would likely result in additional opportunities in future funding processes.

Similarly, if businesses diversify their collaborations or aim to meet commitments, they improve their odds of success in the CO2 utilization market. Initiatives such as these create opportunities for businesses to access broader knowledge, perspectives, and skill sets, which can lead to further collaborative possibilities. (See Finding 4-5.) For example, the submission of Promoting Inclusive and Equitable Research Plans, which outline diversification tools such as engagement and collaboration with underserved populations, organizations, and institutions, and provision of professional and learning opportunities for underrepresented populations, such as Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) professionals with science and engineering expertise, are now required for some DOE FOAs (DOE n.d.(e)). These plans seek to advance the federal Small Business Innovation Research/Small Business Technology Transfer (SBIR/STTR) program goal to foster and encourage participation by socially or economically disadvantaged groups in innovation and entrepreneurship.

4.3.2.3 DOE Resources for Small Business Partners

In 2021, Sick et al. (2022) estimated that, of 160 developers active in CO2 capture and utilization, 39 were new start-ups that had emerged since 2016. Small businesses and start-ups can enter and thrive in the nascent field of CO2 utilization, and their participation is critical to the development and diversification of CO2-derived product markets. For example, within the design of hubs, small businesses would have to build their own niche based on what is needed in the system, which provides both a challenge and an opportunity. By securing a specialized role in a hub, small businesses can expect to develop an expanded role as the sector grows and more capacity is required.

The federal government has initiatives that target small businesses and encourage opportunities that will grow the CO2 utilization sector. For example, through cross-agency coordination, the General Services Administration (GSA) administers awards on behalf of clients in participating agencies and provides information on its website about how to undergo certification processes (GSA n.d.(a), n.d.(c)). The SBIR and STTR programs are another opportunity, and can help small businesses or start-ups initiate relationships with DOE. Projects are awarded in three distinct phases: Phases I and II provide R&D funding, and Phase III—during which federal agencies may award follow-on grants or contracts for products or processes that meet the mission needs of those agencies, or for further R&D—provides nonfederal capital to pursue commercial applications of that earlier R&D (SBIR n.d.). Small businesses experience various challenges to accessing these opportunities or being successful in this nascent sector, including limited awareness of relevant funding calls; limited ability to access facilities that could help their business development and/or result in meaningful partnerships to close gaps in their processes; and barriers in navigating available federal funding and required reporting. More support is needed for small businesses to overcome issues with accessing a broader market in addition to federal funding and resources.

DOE national laboratories provide a unique entry point for business leaders to engage with federal initiatives and programs while developing their business to better meet the needs of the sector. For example, Argonne National Laboratory’s Small Business Program provides business owners with technical assistance related to procurement and

___________________

13 Range includes first-of-a-kind and nth-of-a-kind facilities.

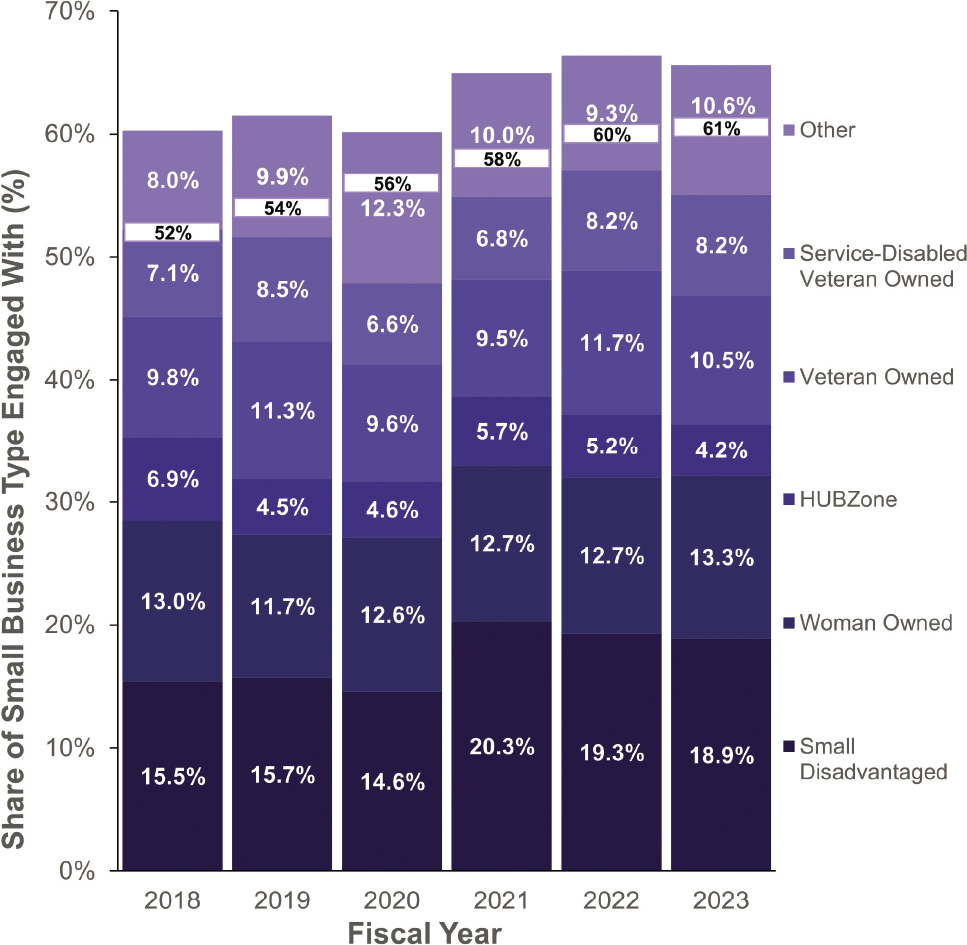

SOURCE: Based on data from SNL (n.d.).

development, and access to a streamlined registration and certification system (ANL n.d.). While no overarching organization provides cross-laboratory information for businesses, most national laboratories provide internal programming with collaboration opportunities. Sandia National Laboratories (SNL), for example, consistently exceeds its small business collaboration goals, reporting $1.1 billion in subcontracts to small and diverse businesses in FY 22, including small disadvantaged, woman-owned, veteran-owned, and service-disabled-veteran-owned businesses and businesses located in Historically Underutilized Business Zones (HUBZones)14 (Peery 2023; see Figure 4-3). These data are particularly encouraging representations of the opportunity that currently exists, and the potential trajectory for collaboration between national laboratories and small businesses, indicating that the Sandia model could perhaps be mapped successfully to other national laboratories across the country.

___________________

14 HUBZone businesses are part of the U.S. Small Business Administration’s program for small companies that operate and employ those in “Historically Under-Utilized Business Zones” (SBA n.d.).

DOE also works with third-party organizations to support the accelerated deployment of technologies. For example, ENERGYWERX, DOE’s first intermediary partner, works to increase joint activities between the agency and small business, higher-education institutions, and nontraditional partners to expand the deployment of clean energy solutions (DOE-OTT n.d.(b)). In growing the carbon management and CO2 utilization sectors, DOE can capitalize on the important role of national laboratories and third-party organizations in developing and commercializing new technologies and MRV methods. Box 4-2 highlights existing opportunities for small businesses to partner with national laboratories and third-party organizations for technology development and deployment support: the Gateway for Accelerated Innovation in Nuclear (GAIN) program and the Voucher Program. The best practices, beneficial components, and lessons learned from both of these programs can be applied to a program developed to aid businesses entering the CO2 utilization sector. (See Recommendation 4-4.)

BOX 4-2

Existing Opportunities for Commercialization Partnerships Through the Department of Energy

GAIN Program

The GAIN program, administered and led by Idaho National Laboratory in collaboration with Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Argonne National Laboratory, is a public–private partnership framework dedicated to rapid and cost-effective development of innovative nuclear energy technologies and market readiness. Its mission is to provide the nuclear energy industry with access to the technical, regulatory, and financial support needed to commercialize innovative nuclear energy technologies at an accelerated and cost-effective pace (GAIN n.d.(b)). Aside from communication and education programming, GAIN offers a host of valuable resources, including (1) physical access to unique experimental and testing capabilities housed within the national laboratory system; (2) computational and simulation tools; (3) data, information, and sample materials from previous research at national laboratories to inform future experiments; (4) use and site information for demonstration facilities; and (5) experts in nuclear science, engineering, materials science, licensing, and financing (DOE-NE n.d.). Access to these resources generally comes through the GAIN Nuclear Energy Voucher Program, which are not grants, but rather competitively awarded tokens that send funds directly to the national laboratory partner for laboratory time, materials, and equipment for the awardee. Since 2016, the GAIN program has awarded $34.2 million in vouchers to 57 different companies (GAIN n.d.(a)). While there are no size restrictions on applicant companies, special consideration is given to small companies.

DOE’s Voucher Program for Energy Technology Innovation

The DOE Voucher Program, overseen by the Office of Technology Transitions (OTT), Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED), FECM, and Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE), is funded by IIJA’s Technology Commercialization Fund (DOE-OTT 2023). The program will provide more than $32 million in commercialization support to businesses, including small businesses (DOE-OTT n.d.(a)). The support offered by the program includes (1) manufacturing or supply chain assessments, community benefits assessments, and other technoeconomic analyses; (2) third-party evaluation of technology performance under operating conditions that are certification-relevant; (3) considerations for technology benefits and challenges and siting and permitting best practices, and the development of streamlined processes for permitting and community engagement; (4) business plan, market research, and other commercialization strategy assistance; and (5) independent MRV practices and performance validation support (DOE-OTT 2023, n.d.(a)).

As part of the Voucher Program, businesses work directly with ENERGYWERX to connect with relevant third-party organizations, subject matter experts, and testing facilities. Lessons learned from this initial round of vouchers can guide future iterations of the programs and serve as a model for other commercialization programs.

SOURCES: Based on data from Jones et al. (2023) and O’Rear et al. (2023).

For emerging CO2 utilization businesses, especially small ones, the available DOE resources and funding need to be appropriately communicated so that diverse types of businesses can access them. Additionally, using programs for other energy-related technologies, like the GAIN and Voucher programs, as a model for CO2 utilization programs can support the entrance of small businesses into this space by connecting them with market and technology experts.

4.3.3 Workforce Uncertainties for CO2 Utilization Businesses

CCUS at scale has been estimated to support 177,000 to 295,000 jobs, while, for comparison, 3.1 million clean energy jobs are aligned with DOE’s net-zero definition15 (DOE-OEJ 2023; MacNair and Callihan 2019). However, regardless of the industry, there are not enough employees in the upstream labor force to support the infrastructure build-out that investors seek to fund. This is not owing to a lack of available jobs. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported an average of 438,000 open construction jobs per month for November 2023 through January 2024 (BLS 2024). Despite the high number of job openings, contractors have reported difficulty finding willing and skilled workers in recent years (NASEM 2023g). For example, the Associated General Contractors of America and Autodesk Cloud Construction (2023) workforce survey found that 68 percent of firms surveyed had trouble filling openings because candidates lacked the skills to work in the industry. This employment trend will persist even without a transition to cleaner energy and products.

Figure 4-4 compares the upstream labor needs predicted for the DAC and SAF workforces. The Rhodium Group estimates that once a facility is built, DAC facilities will need 340 ongoing jobs, and SAF facilities will need 1440 ongoing jobs to support operations (Jones et al. 2023; O’Rear et al. 2023). Beyond the ongoing jobs related to maintenance, executive and business operations will comprise 11 percent of the ongoing employment for DAC facilities, and agricultural workers and managers will comprise 25 percent of the ongoing employment for SAF production (Jones et al. 2023; O’Rear et al. 2023). Small businesses aiming to participate in either field will need to match the skilled labor required to maintain facilities if they hope to compete with larger, more developed businesses.

___________________

15 DOE defines clean energy jobs aligned with a net-zero future as relating to “renewable energy; grid technologies and storage; traditional electricity transmission and distribution for electricity; nuclear energy; a subset of energy efficiency that does not involve fossil fuel burning equipment; biofuels; and plug-in hybrid, battery electric, and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles and components” (DOE-OEJ 2023, p. viii).

Very little research has been done to predict the workforce needs for CO2 utilization-specific businesses. However, the skill sets required for CO2 utilization projects are expected to translate from existing processes and skill sets for fossil fuel refining and chemical industries, as discussed in Section 4.2.1.2.1. Specialized training—which may be required for R&D-related workforces—will play a key role in workforce development for the growing sector, especially depending on its accessibility or lack thereof. Individuals with specialized skills tend to make more money while being a lower percentage of a sector’s workforce. For example, in oil and gas extraction in 2022, 1700 geoscientists (a specialized occupation in the field) were employed with an average annual salary of $145,660, compared to the 9340 wellhead pumpers employed with an average annual salary of $69,770 (BLS n.d.). This presents a challenge for small businesses because they likely will have to hire highly skilled employees at a high cost. Incentives are needed to encourage the development of a sustainable labor force for CO2 utilization that additionally support the access of small businesses to these skill sets. Special attention will need to be paid at federal and state levels to address the challenges and barriers and allow for the diversification of the CO2 utilization sector as it builds out.

4.4 SOCIETAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR THE EMERGING CO2 UTILIZATION SECTOR

Societal dimensions need to be considered and appropriately addressed in CO2 utilization policy, project design, and workforce development as the sector continues to build out. These considerations include the meaningful engagement of publics and communities, intentional focus on remediating and avoiding environmental harms, and equitable access to economic and workforce benefits of the emerging sector. Without these societal considerations, the CO2 utilization sector runs the risk of perpetuating past and current environmental and social injustices. This section defines relevant equity and justice terms, summarizes best practices for public and community engagement, elevates select principles of EJ, and identifies key economic considerations. Box 4-3, modified from the first report’s Box 5-1, includes definitions of key concepts of justice and equity discussed throughout this section.

BOX 4-3

Concepts of Justice and Equity

- Justice—Social arrangements that permit all (adult) members of society to interact with one another as peers (Nancy Fraser, quoted in Cochran and Denholm 2021). The principles of justice discussed in this section are: recognitional justice—understanding the historical and present bias regarding societal inequalities, especially about the treatment of communities (Cochran and Denholm 2021); procedural justice—the ability of people to be involved in fair decision-making processes (Cochran and Denholm 2021; Kosar and Suarez 2021); restorative justice—the act of repairing the impact of past injustices to restore communities and the environment to their original position (Hazrati and Heffron 2021); and distributive justice—equitable allocation of resources, risks, impacts, and benefits and burdens across society (Cochran and Denholm 2021; Kosar and Suarez 2021).

- Environmental justice—The just treatment and meaningful involvement of all people—regardless of income, race, color, national origin, Tribal affiliation, or disability—in decision-making activities related to climate change, the cumulative impacts of environmental and other burdens, and the legacy of racism or other structural or systemic barriers that disproportionately and adversely affect human health and the environment (EPA n.d.(b)).

- Social justice—A situation in which (1) benefits and burdens in society are dispersed with the allocation of a set of principles; (2) procedures and rules that govern decision making preserve the basic rights and entitlements of individuals and groups; and (3) individuals are treated with dignity and respect by authorities and other individuals (Jost and Kay 2010).

- Equity—Achieved results where advantage and disadvantage are not distributed based on social identities (Initiative for Energy Justice 2019). In this section, emphasis is placed on equitable access to a healthy, sustainable, and resilient environment in which to live, play, work, learn, grow, worship, and engage in cultural and subsistence practices.

- Disadvantaged community—A community that is marginalized by underinvestment and suffers the most from a combination of health, economic, and environmental burdens, including high unemployment, air and water pollution, and poverty (Kosar and Suarez 2021; White House n.d.(b)). Relatedly, marginalized/underrepresented communities are groups that experience societal barriers such as social, political, or economic exclusion or discrimination (Machado et al. 2021; Nakintu 2021). In this section, these terms are used interchangeably.

4.4.1 Public and Community Engagement Considerations

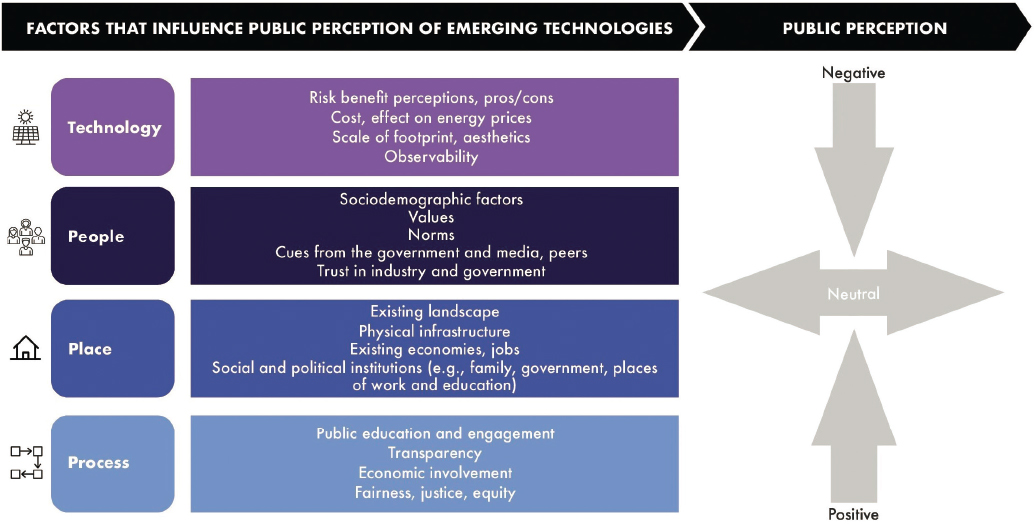

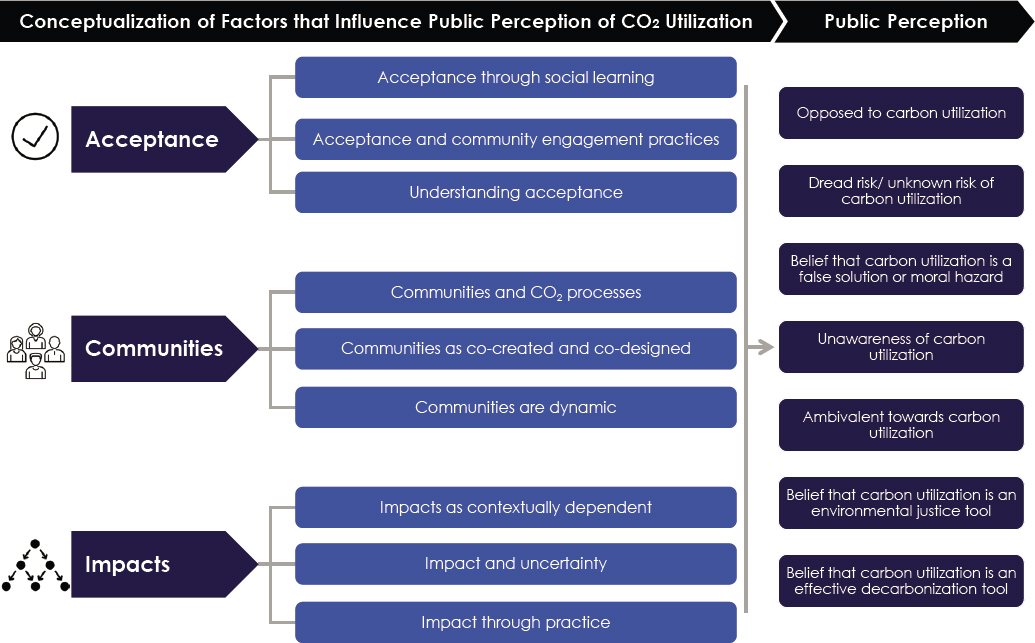

CO2 utilization is part of a suite of carbon management practices that are being designed to support the nation’s net-zero goals. In general, decarbonization pathways face a spectrum of responses from the public—from acceptance to opposition—which is common for emerging technologies (Boudet 2019; NASEM 2023f). Opposition to technologies can be broken into two dimensions: (1) concerns inherent to a technology (e.g., how will a project impact everyday life?); and (2) concerns related to the institutions that govern the technology (e.g., are the regulatory systems effective and competent and is a community being meaningfully consulted in deployment?) (NASEM 2023f, Table 8-1). Figure 4-5 illustrates the factors that affect public perceptions of and related responses

SOURCES: Modified from H.S. Boudet, 2019, “Public Perceptions of and Responses to New Energy Technologies,” Nature Energy 4:446–455, Springer Nature. Icons from the Noun Project, https://thenounproject.com. CC BY 3.0.

to new technologies.16 Studies show that providing the public with more information can lead to a shift in public support of new technologies (Stedman et al. 2016; Stoutenborough and Vedlitz 2016). However, the views of the media, peers, and trusted messengers (i.e., academics or social movement activists) also shape public responses to energy technologies (Boudet 2019).

Carbon management technologies and processes as a whole have been described as “false solutions”17 by EJ advocates (e.g., see Chemnick 2023a; Earthjustice and Clean Energy Program 2023; Just Transition Alliance 2020; New Energy Economy n.d.). Additionally, there is a public perception that investment in carbon management is outsized compared to the limited contribution that such technologies are expected to make to climate change mitigation (Jones et al. 2017). Skepticism that investment in CO2 utilization and its value chain is disproportionately large relative to its climate mitigation potential motivates negative public discourse. However, Seltzer (2021) found that 80 percent of the U.S. public either does not know of CCUS technology or cannot definitively recognize it. Transparency about how products are made, how widely used CO2-derived products are, and how R&D investments compare to the products’ GHG impacts can support the public’s understanding of CO2 utilization in relation to carbon management efforts. This section examines opportunities to use public and community engagement to (1) expand public understanding of CO2 utilization; (2) confront justice and equity questions that shape perceptions of the sector; and (3) communicate CO2-derived product pathways that align with public and community needs. (See Finding 4-7.)

4.4.1.1 Current Public Discourse Around Utilization

Most societal acceptance research about carbon management uses CCS to gauge an individual’s understanding before following up with questions on CO2 utilization, either because carbon capture is a source for CO2derived products or because CCS is more widely discussed. For example, Offermann-van Heek et al. (2018) used semistandardized interviews to identify the most important factors concerning trust and acceptance of CO2 utilization. The results of the qualitative study were incorporated in a quantitative online survey of 127 participants, which found that a lack of knowledge or awareness of CCS was owing to misconceptions, misleading information, or pseudo-opinions. When questions focused on CO2 utilization, Offermann-van Heek et al. (2018) found individual differences in preferences for end products (e.g., long-lasting cement versus fuels), skepticism about whether investment in CCS and CO2 utilization is worthwhile (e.g., preventing actual societal change, maintaining business as usual), and the acceptable amount of risk for health, sustainability, product quality, and the environment.

Offermann-van Heek et al. (2018) also found that customers have concerns about manufacturing considerations (e.g., the sustainability of production) and company considerations (e.g., company environmental management) for CO2-derived products. These concerns align with public considerations for conventional products, suggesting that customers do not view CO2-derived products differently. However, there are some challenges within the construction industry for using CO2-derived building materials (see Box 4-4).18 The concerns of both consumers and the construction industry can be addressed through low-stress testing projects, such as sidewalks and driveways (Derouin 2023). The transparency of testing products in public spaces can also support public communication of results.