Planning for Future Electric Vehicle Growth at Airports (2024)

Chapter: 2 Advanced Topics on EV Charging

Chapter 2. Advanced Topics on EV Charging

This chapter addresses questions on advanced topics on EV charging, building on fundamental questions addressed in Chapter 1.

What are best practices for siting EV charging locations at airports?

Across the eight use cases, airports should ask the following questions when selecting a site for a charging location:37

- What is the distance to utility-owned and airport-owned electricity infrastructure?

- Will EVSE installation disrupt existing infrastructure (e.g., will trenching be needed)?

- What is the distance to networking and communication infrastructure?

- Is there adequate space for multiple types of users to access and interface with EVSE?

- Can an EVSE plug reach multiple parking spots (e.g., if a non-EV is parked in one spot, can the charger still be used)?

- Is there adequate space to maintain and repair EVSE?

- Is the location prone to flooding?

- Is there available space for installing additional EVSE in the future?

- Should the location provide preference to EV drivers (i.e., closer proximity to the terminal)?

Every location has pros and cons. To reduce the complexity of construction required to install charging stations, airports should strive to balance the questions above. For example, a potential charging location with ample space for EVSE may not be a good choice if extensive trenching would be required to provide adequate power to the site.

What are specific considerations for siting airside EVSE?

Beyond general siting information above, key considerations in the siting of airside charging stations require coordination with FAA airside safety requirements and include the following:

- Connectivity between the landing area and charging stations.

- Availability of facilities and services for operators and cargo.

- Environmental impacts.

- Airspace surface compatibility for the charger and aircraft.

- Safety Area dimensions to define aircraft parking and impacts to existing layout.

Some electric aircraft have wingspans of 50 feet or more. Setbacks and object-free areas must be checked, and aircraft will need room to park after charging. The airport should utilize existing apron space without negatively impacting apron parking. Siting chargers near a fixed based operator (FBO) or general aviation (GA) terminal can provide many of the services aircraft operators may need.

Key considerations for eGSE equipment, non-airport-owned airside vehicles, and airport fleet vehicles should include the following items for site selection.

- Ground Power Units (GPUs) near the gate or terminal and power supply at the gate (dependent on power availability and age of the terminal) for eGSE.

- Clear pathways of the Airport Movement Area.

- Fire code restrictions of proximity to the buildings.

Operators need to comply with applicable local and federal fire codes with charging infrastructure near the terminal area and tenant buildings. More information regarding codes can be found in Chapter 5.

How should facility managers select the number and type of chargers?

Decisions about the number and type of chargers at a site are driven by several factors. A summary of key considerations that contribute to charger type selection is provided in Table 4.

Table 4. Considerations for EVSE Port Selection

| Planning Factor | Consideration |

|---|---|

| How long will vehicles be parked at a charging location (dwell time)? | Longer dwell times can allow lower power charging. |

| How much funding is available for charging? | Hardware and construction costs increase with higher power charger installation. |

| What type(s) of vehicles will use the EVSE? | Low power charging is often suitable for LDVs, while MDHDs typically requires higher power charging. |

| Will revenue be collected from charger users? | Only networked chargers can accept user payment. |

| How many vehicles will each charger serve daily? | The more vehicles that will be served daily, the higher the power rating of the charger. |

| How much power needs to be delivered to the vehicle per charging session? | DCFC chargers are required for high power charging. |

| How much power is available to the charger at the project site? | High power charging may require significant infrastructure upgrades to expand available electrical capacity. |

| How much physical space is available at the project site for the EVSE, switchgear, transformer, and other infrastructure? | High power charging installations may require additional infrastructure that may reduce available parking or require site redesign. |

Approaches to charger selection will vary. Figure 21 provides an example of a simplified decision tree to inform charger selection. Note that for any charging infrastructure project, it is critical to understand the available electrical capacity at the proposed project site and to assess what electrical infrastructure upgrades may be required to support the proposed EVSE.

Figure 21. Example EVSE Decision Tree

Source: Consultant Team

Who provides EVSE?

There are numerous charging providers operating in the United States that provide various combinations of hardware, network subscriptions, installation, and maintenance. Each company’s business model depends on the requirements of the specific site host. For example, the most prevalent non-Tesla EVSP is ChargePoint which primarily provides charging equipment and networking services, while individual site hosts are responsible for installation and maintenance. Other EVSPs, such as Electrify America, provide a turnkey solution to site hosts, whereby the hosts can fully operate and

maintain the charging infrastructure and set retail electricity prices. Table 5 presents a summary of the 10 largest EVSPs operating in the United States, all of which serve passenger vehicles.

Table 5. Summary of Largest Electric Vehicle Service Providers

| EVSP | Level 2 EVSE Ports | DCFC EVSE Ports | Total EVSE Ports | Provides Hardware | Installs and Maintains Hardware | Sets Station User Fee | Provides Cloud Network |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChargePoint | 62,669 | 2,450 | 65,119 | ✓ | - | - | ✓ |

| Tesla | 15,019 | 24,517 | 39,536 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Blink Charging | 16,535 | 151 | 16,686 | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ |

| FLO | 6,886 | 576 | 7,462 | ✓ | - | - | ✓ |

| Electric Circuit | 4,070 | 874 | 4,944 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Electrify America | 220 | 3,835 | 4,055 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| EV Connect | 2,862 | 768 | 3,630 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Voltaa | 3,029 | 115 | 3,144 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Shell Recharge | 2,455 | 620 | 3,075 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| EVgo Network | 341 | 2,713 | 3,054 | ✓ | - | - | ✓ |

a Volta is now part of Shell Recharge.

Source: DOE AFDC and Consultant Team, Accessed November 14, 2023

How can airports “futureproof” charging infrastructure?

Futureproofing means building charging infrastructure to accommodate future changes in charging demand or technology. Effective futureproofing reduces costs and saves time. For example, futureproofing includes placing extra conduit and larger conductors to limit the need for trenching if the installed capacity needs to expand or coordinating TTM infrastructure with the local utility to oversize transformers and switch gear. “EV-ready” is synonymous with futureproofing. Specific requirements for EV-ready infrastructure vary by jurisdiction but typically include a combination of increased panel capacity, installation of electrical stub-outs (Figure 22), additional conduit and conductors, and pouring extra concrete pads.

Figure 22. Examples of EVSE Stub-Outs

Source: Consultant Team

Who owns and operates charging infrastructure?

There are several potential ownership models for charging infrastructure:

- Site Host Owner-Operator. In this model, the owner of the property providing the charging infrastructure (such as the airport) owns, maintains, and sets user fees at the charging stations. This model provides the site host control of infrastructure and allows hosts to keep all revenue generated from fees for the electricity sold. This model also increases risk for the site host, who is responsible for ongoing maintenance, technology upgrades, and potential financial losses due to low charger utilization or lack of charge management (see: What are demand charges and why are they important?).

- Utility Owner-Operator. A site host may choose to partner with the local electric utility for the design, construction, and operation of charging infrastructure. The utility may lease the chargers to the site host or may develop its own sites and charging network. By partnering with the utility, a site host may mitigate the risks associated with maintenance and operation and may also reduce design and permitting delays because of close coordination with utilities. However, the revenue generation potential for the site host is lower than with other models.

- Third-Party Owner-Operator. A site host may contract with a third party, such as an EVSP, to handle some or all EVSE ownership, operation, maintenance, and billing responsibilities for the charging stations. An example of this model is the Electrify America charging plaza at the Sacramento International Airport.38 In this model, the EVSP provides a turnkey solution, and the airport provides the land. There is flexibility in this approach as the two parties are free to negotiate a mutually agreeable set of terms, roles, and responsibilities. With this approach the site host and third-party vendor may enter into a revenue sharing agreement, whereby the host collects a portion of the revenue generated from electricity sales.

- Charging-as-a-Service (CaaS). With this business model, a third party provides all capital associated with developing the charging infrastructure. The third party owns the equipment and effectively leases it to a site host under a service agreement, which may also include operations and maintenance. This approach can be beneficial for entities that wish to reduce the upfront capital cost of developing the charging infrastructure by converting this cost to an operating cost that is typically charged as a monthly fee along with additional service charges by the vendor. This arrangement may increase the long-term costs for site hosts because larger fees are spread out over the lifetime of the operating agreement; it may also result in higher fees for charging fleet vehicles that the site host may operate.

What maintenance do charging stations require?

Responsibility for the maintenance of charging stations at airports varies depending on the ownership structure of charging equipment and the specific relationship between an airport, the relevant EVSE installer, and any third-party organizations involved in ownership and operation of EVSE. It is important for airports to establish who is responsible for the operations and maintenance (O&M) of their charging stations and to include details in maintenance contracts regarding response time, repair time, and overall uptime requirements.39 The U.S. DOE Alternative Fuels Data Center recommends that station

owners estimate an average maintenance cost of $400 annually, per charger, and that most charging networks offer maintenance plans for an additional fee.

There are several preventative maintenance measures for EV charging stations: 40

- Install raised concrete pads to limit equipment exposure.

- Place screens away from direct sunlight and use protectors to prevent damage and overheating.

- Install collision protection and signage to prevent and limit damage from accidents.

- Use short cords or cord controls to protect charging cords from people and vehicles.

- Store cords on EVSE dispensers or use cord retractors to increase safety and prevent damage when charging equipment is not in use.

There are also several best practices for the regular maintenance of EV charging stations:

- Shut off power to equipment before conducting maintenance.

- Clean connectors and pins with light detergent and non-abrasive cloth.

- Inspect power to EV charging equipment before conducting maintenance.

- Conduct routine inspections of cord and cord storage devices for wear.

- Clean air conditioning or cooling filters.

- Inspect the mounting area of EVSE for potential compromises like cracks and flooding.

- Review data reports for errors or signs of error in the cloud communication system.

- Compare EVSE data with utility bills to confirm that equipment is functioning properly.

There is no existing standard practice for regular maintenance of EV charging stations. Software, data, and communications systems should be monitored daily to ensure functionality. Inspection of hardware can occur on a weekly or monthly basis.

How are charging fees set?

When the EVSE owner is a different entity than the EVSE user, the owner must determine if and how to assess a fee for usage. There are three general categories for how an EVSE owner sets user fees:

- Loss Leader (no fee or small fee). Charging is offered as an amenity for free or for a small fee. At airports, free charging is most often associated with non-networked Level 1 or Level 2 chargers. Typically, this method is used when the EVSE owner wants to increase customer, employee, or tenant satisfaction.

- Cost Recovery (nominal fee). The charging fee is set high enough for the owner to recoup installation and operational costs but not to create new revenue. Fees are typically set on a per kWh basis to achieve a lifetime, net present value of zero.

- Profit Center. The charging fee is designed to turn a profit from the sale of electricity. Due to demand charges set by electric utilities, it is very difficult for any DCFC charging station to generate enough revenue to cover investment costs on its own without high utilization. Fees are typically set as a price per kWh, per unit of time, or per charging session.

Common pricing structures include charging fees by kWh, by session, by length of time, or through a subscription. In public charging locations, EVSPs offer different pricing models, including member versus

non-member fees, user-specific pricing (specific to certain vehicle owners), site host–specific pricing, and pricing based on rate of charge.41 In a standard pay-as-you-go model, drivers pay a set price per minute or per kWh that depends on the level of charging or the amount of energy consumed in a specific charging session. Often EVSPs will collect a nominal fee to initiate a charging session. Most EVSPs offer a membership model, which provides a reduced cost per kWh or per minute for charging and replace session fees with a flat monthly fee. Some EVSPs will also add a fee for leaving a car parked after a charging session has been completed to discourage vehicle idling at charging stations.

Session- and time-based structures are common in states where non-utilities are prohibited from reselling electricity. Over 30 states and Washington DC42 currently allow per kW sales of electricity for public charging. In some markets, such as California, consumers can take advantage of time-of-use pricing, with which the retail cost of electricity sold is lower during off-peak hours, (e.g., overnight). In states where session- and time-based structures are required, if a charger is dispensing electricity at a slower rate than expected because of faulty equipment, weather, or grid constraints, the actual cost per kWh may be higher.

The cost for charging a vehicle varies for the different charging types. For example, a non-member driver using an Electrify America DCFC station in Texas will pay $0.19 per minute for peak charging speeds of up to 90 kW but will pay $0.37 per minute for a charging speed of up to 350 kW.43 This pricing reflects demand charges levied by the utility and the increased infrastructure and technology costs for high power chargers.

What is dwell time?

Dwell time refers to the length of time a vehicle is parked at a location. Dwell time is a critical component of the EVSE selection process; the slower the charging speed, the longer the required dwell time. Dwell times can range from minutes to hours to days depending on the charging use case. For use cases such as long-term passenger parking where vehicles may be left for multiple days, L1 charging is suitable and provides a low-cost solution. Conversely, installing L2 chargers in long-term parking areas may decrease revenue for the airport, as vehicles will have long dwell times, which will prevent other drivers from using a charger. In general, public chargers should have the highest utilization possible to increase revenue generation, while private chargers can be operated to match the duty cycle of the vehicle(s) they serve. As highlighted in Chapter 2, it is expected that many use cases of EV charging at airports will have short dwell times (i.e., under one hour), and therefore will require DCFC charging.

What is load shape and why does it matter?

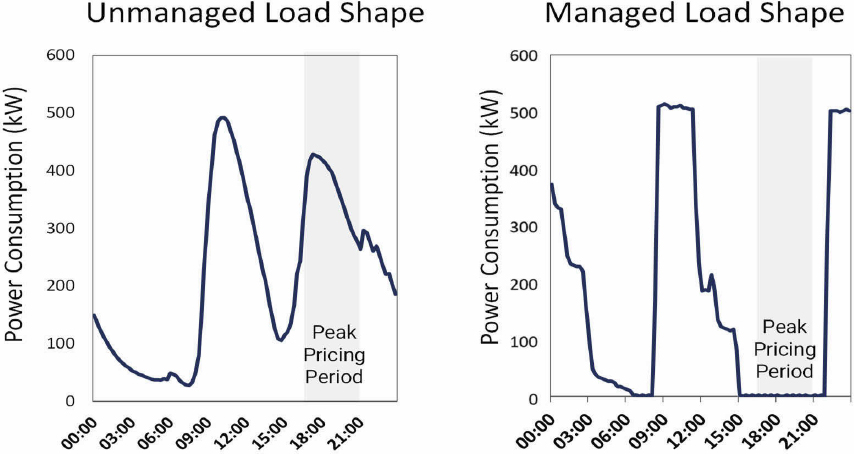

Load shape refers to the profile of electricity consumption resulting from vehicle charging over a specific period, often measured in days, months, or years. Load shape is an important metric for airports and utilities to use to understand demand, forecast the need for infrastructure upgrades, and determine how to implement demand management strategies to smooth electricity consumption and reduce peak load. Concurrent vehicle charging, particularly for DCFC EVSE, can cause large demand spikes, affecting grid stability and increasing electricity costs; these effects can be avoided through charge management.

Charge management, or smart charging, refers to strategies that can control and optimize the load shape from vehicle charging to minimize grid impacts and reduce costs. Most networked chargers can be programmed to charge at different times of the day or can respond to pricing signals to take advantage of off-peak rates or participate in demand response programs. Many electric utilities offer time-of-use (TOU) rates for EV charging, which incentivizes EV owners to charge vehicles during off-peak periods, such as overnight, which can significantly reduce costs associated with charging.

Figure 23 (left) presents an unmanaged daily load shape of a fleet of vehicles, characterized by peaks in the morning and the end of the workday. Figure 23 (right) shows the same load shape when the fleet manages their charging around the peak pricing period of 4 p.m. to 9 p.m.

Figure 23. Load Shape of Vehicle with (Left) and without (Right) Managed Charging

Source: Consultant Team

Charge management is not applicable to use cases that have no ability to change when or where they plug in and charge (e.g., emergency response vehicles). While charge management can be employed to reduce costs, it does not prevent the charger from being operated outside of selected time windows. Users can override this programming to charge an EV when needed.

What are demand charges and why are they important?

Demand charges are fees that electric utilities impose based on the peak electricity consumption of a customer over a specific period in a billing cycle. While standard electricity rates and charges are based upon the number of kWh consumed (i.e., $.17/kWh), demand charges are based upon the highest (peak) demand for a given period, measured in kW as shown in Figure 24. Because demand charges are based on peak use within a specific window of time rather than on total energy consumption, the demand surcharge is applied across the billing period. Peak demand may only occur infrequently for a given customer, but the utility must maintain the capacity to meet that demand during any period.

Figure 24. Example of Peak Demand for Month of March 2022

Source: Consultant Team

Demand charges reflect the need for electricity utilities to build out grid infrastructure and supply electricity to meet peak energy demand, which requires significant additional investment. They help to ensure that costs are distributed to those customers who more significantly impact growth in peak demand across the system. The higher the peak load, the more costly it is for the utility to provide electricity to its customers. Demand charges are also used to encourage customers to shift consumption to periods of lower overall demand, which makes it much easier (and less costly) for grid operators to manage consistent load across time periods and avoid major demand spikes.

Calculating Demand Charges

The basic formula for calculating demand charges is:

Demand Charge = Peak Demand (kW) × Demand Rate ($/kW)

where:

Peak Demand (kW): The highest recorded energy demand during the specified period

Demand Rate ($/kW): A rate the utility sets that is specific to each customer or customer category, that can vary widely based on the utility’s pricing structure, and that may also have time-of-day and seasonal variations.

Electric utilities use different approaches to calculate demand charges, but in general these fees are applied as incremental costs for increased demand. They may be applied per kW ($/kW), by blocks of kW (e.g., $ per additional 10 kW), or using a tiered system (e.g., one rate when demand is 0-1000 kW, another rate when demand is 1,000-5,000 kW, etc.).

Demand charges are particularly relevant for DCFC charging. Unlike L1 and L2 charging, which may have minimal impact on peak demand, DCFC charging requires short periods of high electricity consumption.

Demand charges can account for 50% or more of total DCFC EVSE operating costs.44 Managing the use of DCFC EVSE can have major impacts, as concurrent charging of multiple vehicles can significantly impact peak demand.

Example of Demand Charge Calculation

The following is an example of how demand charges might be applied in two scenarios with eight networked 150 kW DCFC EVSE ports installed at an airport ConRAC to charge the fleet:

- Scenario 1: EVSE is available to concurrently charge eight vehicles, which occurs approximately three times per month. The peak demand is 150 kW x 8 = 1,200 kW

- Scenario 2: Using managed charging, EVSE is programmed to limit concurrent charging to only two EVSE at a time. The peak demand would be 150 kW x 2 = 300 kW.

If the utility demand charge is $10/kW, this would mean that this EVSE site would cost $9,000 more per month to operate in the first scenario than in the second.

What is demand response for EV charging?

Demand response refers to changes in electricity consumption by customers in response to price or reliability signals distributed by the utility. The goal of demand response programs is to decrease grid stress during periods of peak demand and minimize electricity costs for ratepayers. Demand response programs include:

- Price-based programs: Changing electricity prices based on real-time supply and demand conditions. Consumers are encouraged to shift demand from high-price low-price periods.

- Incentive-based programs: Consumers receive financial incentives for reducing their electricity usage during peak times. These incentives include bill credits, cash payments, or discounts.

- Time-of-use (TOU) programs: Electricity rates vary depending on the time of day. Consumers pay more during peak hours and less during off-peak hours, encouraging them to use electricity when it is cheaper (see What is load shape and why does it matter?)

Demand response programs are often used to reduce costs associated with EV charging; however, these programs are not available in every state, and they vary by electric utility. In the future, EVs will likely be able to participate in Automated Demand Response (ADR) using the open charge point protocol (OCPP), whereby EVSE can be programmed to respond to real-time pricing signals by minimizing consumption during periods of peak electricity demand or increasing charging when the supply of renewable energy on the grid is high without the need for human intervention.

What is bidirectional charging?

Bidirectional charging refers to the ability of an EV battery to both receive and send electricity back onto the grid or to other devices. The most common term associated with bidirectional charging is vehicle-to-grid (V2G), but also includes vehicle-to-building (V2B), vehicle-to-load (V2L), vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and vehicle-to-home (V2H); inclusively referred to as vehicle-to-everything (V2X).

Bidirectional charging, or two-way flow of electricity, is a potential benefit for EV operation in the future, particularly for large fleets. Using the proposed ISO 18118 V2G communications protocol, vehicle batteries could be used to send electricity back onto the grid during demand response events (times when signals are sent to customers to reduce load). EV batteries could be charged when electricity prices are low, and that energy could be sold back to the grid when prices are high. If implemented across a large fleet, bidirectional charging could provide a significant resource to shift load and enhance grid stability or could be used to store excess renewable generation in EV batteries and distribute electricity back onto the grid during periods of higher demand. EV batteries could also be used to enhance resiliency by serving as a source of backup power during grid failures or emergency events.

Bidirectional charging and V2G technologies are in the early stages of deployment, and only a small number of EVs have bidirectional charging capabilities, such as the Ford Lightning and the Nissan Leaf. Most EVSE does not have V2G capability today, but this capability is expected to increase in the future.

What is interoperability for EVSE?

Interoperability refers to the ability for EVs and EVSE from different manufacturers and network providers to operate compatibly. This includes the compatibility of hardware, such as EVSE connectors and payment systems, and of communications systems to integrate multiple EVSE types into a central management system (CMS) to monitor and control EVSE. As EV and EV charging technologies continue to evolve, there is a significant push to develop charging standards that can be adopted nationally.

Hardware interoperability for EVSE charging hardware is focused on the customer interface. This includes the common EVSE connectors—J1772, CCS, and NACS. It also includes customer accessibility, ensuring that public EV chargers do not require membership for use or include multiple payment options. Hardware interoperability aims to make EV charging a convenient, consistent process for users regardless of the make and model of vehicle and across EVSE of all types. Interoperability also increases market competition and reduces infrastructure costs by building a unified charging network.

Software interoperability is focused on communications systems. The OCPP is a standard communication protocol used for EV charging. OCPP is a scalable, open-source, vendor-neutral protocol that governs how EVSE communicates with central network servers and is critical to controlling both charging and processing of payments. OCPP enables interoperability between various EV charging stations and CMS to ensure that EVSE manufacturers and charging network operators can create compatible systems that work together. OCPP has not yet been adopted as a national standard, and many EV charging networks currently operate on proprietary protocols, leading to interoperability issues.

Case Study: San Diego International Airport (SAN)

SAN is a single-runway commercial service airport serving roughly 15 to 25 million passengers per year. In recent years, the airport has moved quickly to advance climate goals, establishing new initiatives like the Good Traveler carbon offset program and achieving Level 4+ Transition in the Airport Carbon Accreditation program—making SAN one of only three North American airports to reach this level. In 2019 and 2020 SAN completed a Strategic Energy Plan and a Clean Transportation Plan to understand energy consumption and facilitate the transition to vehicle electrification.

The airport began installing charging systems in the 1980s, focusing initially on charging for eGSE. Since then, the airport authority has continued installing eGSE charging at Terminals 1 and 2 (Figure 25). In 2022, SAN installed its latest eGSE using a combination of funding from a Federal Aviation Administration Voluntary Airport Low Emissions (VALE) grant, which covered the purchase of 39 EVSE ports, and incentives from the SDG&E’s Power Your Drive for Fleets program, which covered 100% of TTM infrastructure upgrades and up to 80% of behind-the-meter infrastructure upgrades. The airport owns and operates the charging stations on behalf of tenants and wraps utility bills into tenant lease payments using sub-meters. As a general rule, the airport attempts to maintain a ratio of between four and five eGSE EVSE ports per gate.

Airport Tip: Plan charging infrastructure for future demand rather than current needs. Futureproofing, or oversizing charging infrastructure such as transformers and wiring to accommodate additional charging stations, can reduce the cost and labor for future installations when more EVs will be deployed. SAN is working to have 10% to 20% of all parking be EV-capable to accommodate additional EVs over the coming decade.

Figure 25. eGSE Charging Equipment at SAN

Source: Consultant Team

Planning for landside charging stations at SAN depends on the use case. As with the eGSE chargers, the San Diego County Regional Airport Authority owns, operates, and maintains all landside charging. For passenger EVs parked in passenger lots, the airport aims to make 10% of all parking spaces EV ready, meaning the space is fully wired and ready for a Level 2 charging install. The airport staff plans to observe EV adoption over time and install chargers to slightly outpace demand, up to the 10% limit. Charging for transportation network companies and taxis is not available at the airport due to a lack of distribution capacity for high-powered chargers.