Geospatial Data Governance Policies and Procedures: A Guide (2025)

Chapter: 2 Drivers for Data Governance

CHAPTER 2

Drivers for Data Governance

Effective data governance requires a mindset that treats data as an asset, which is just as important as a physical “sticks and bricks” asset with a life cycle. The drivers behind this change include regulation, champions, return on investment, and the desire to avoid costly mishaps. What has been seen through the research in this guide is that data does not always get the same prioritization and investment in environments where physical assets and tangible operations garner the most attention. Unfortunately, the challenges that hinder such change (e.g., silos, resistance to change, proprietary formats) are naturally engrained in most organizations and humans but can be offset once identified. To overcome these challenges, organizations must weigh the benefits and costs and then commit to the steps necessary to establish and sustain effective data governance.

Data is an asset in that it is a resource that airports own and will provide future benefit (Barone 2022), but “because data is an intangible asset that is not recognized as an asset by modern accounting standards, it is often not managed as an asset” (Collins 2019). Managing assets is an increasingly important activity among airports seeking to maintain safety, operate more efficiently, increase customer satisfaction, respond to regulatory changes, and ultimately make better investment decisions (GHD, Inc. 2012). Unfortunately, since data is often not seen as an asset, it is not governed with the same level of rigor as physical assets, and the investment made in digital data can be lost or maintained in a silo.

“To maximize the return on its data assets, all the parts of an organization need to contribute to the asset and its conversion into useful information” (Collins 2019). This requires a mindset change to treat data as an asset and manage it in a manner that provides the most future benefit. Data must be maintained to the level of quality required and be supported by users. Also, it must be maintained so that quality improves and does not diminish with time. It must be made available to those who have a legitimate need and protected from those who do not. In short, data must be governed well to provide the maximum value while minimizing risk.

2.1 Drivers

There are several drivers that can change the mindset of managers and staff, so they treat data as an asset and govern it in a manner that produces the most return. The following are the primary drivers of change that have been identified among airports and other organizations that work extensively with geospatial data.

Regulation is perhaps the most compelling driver of change because organizations do not have a choice—they must comply. To remain in compliance with regulations, airports have had to adjust their data governance practices so the data these agencies require is maintained and

submitted or reported in a specified manner. Regulations that have driven change in the airport industry include the following:

- The FAA’s updated Guidance for Airports Geographic Information Systems (AGIS) Survey Program requires airports to submit geospatial data defined as safety-critical to stay in compliance with Grant Assurance 34 and Passenger Facility Charge (PFC) Assurance 9;

- The Geospatial Data Act of 2018;

- EUROCONTROL’s aeronautical data quality (ADQ) requirements; and

- South Carolina’s Code of Laws, Title 55, Chapter 13, Section 55-13-5 requires airports to maintain geospatial data to support airport land use compatibility planning).

Champions who promote the value of data and foster organizational practices that maximize this value have also driven airports toward improved data governance. Champions are individuals who exhibit conviction, courage, clarity, and consistency (Brown 2018).

Return on investment (ROI) is a driver of many activities at airports and a responsibility that senior managers are entrusted to deliver. Having geospatial data has generally been determined to deliver a positive ROI at airports. Maintaining this data through a data governance program has also been found to justify its costs. These benefits accrue from reusing the data. Specific benefits often include improved aircraft operational safety by removing obstructions to navigable airspace or improving airfield geometry to avoid runway incursions. Other benefits include finding terminal space to lease at optimal market prices, improving the efficiency of performing airfield inspections, and addressing work order location to enable trend analysis by location.

Efficiency is the goal of data maintainers who periodically must enter numerous new records or update existing records to reflect the ever-changing configuration of assets and facilities that constitute an airport. Some data maintainers (see SFO case study in Appendix A) have established data governance standards, procedures, and policies to improve their data maintenance program efficiency. Since the result of their efforts helps achieve overall organizational objectives, their efforts are often supported by management.

Mishaps, ranging from avoidable construction utility strikes to loss of life, have impacted airports and, in some cases, could have been avoided with better data. Although unlikely and hard to predict, a single event can justify the cost of improved data governance. Far too often, such events have occurred and prompted change in hindsight that would have been better addressed with foresight.

Reliance on geospatial data is increasing at airports and increasingly available to support informed decisions. Location data is also a required input to many airport systems, in addition to data about the system elements and attribute data and metadata (i.e., data about the data). As this reliance grows, senior managers have become more aware of the importance of data and are more willing to fund data development and governance initiatives.

Data-driven decision making is another approach for determining the impact of a given program. Establishing key performance indicators (KPIs) can help guide business decision-making and enhance activity metric reporting with a locational component managed and integrated with geospatial data.

Organizational goals, such as improving customer experiences at the airport or improving airport safety and security, are also effective drivers for data governance. For example, data governance can support the airport’s occupational safety program by tracking accidents by work location type (e.g., field, building, office) and identifying automobile accident hot-spot locations. Data governance could potentially help diagnose the issues in these and other instances and provide better and alternative solutions.

Each of these drivers have led airports and other types of organizations toward improved data governance. Once managers and staff at airports begin treating data as an asset that must be maintained, the quality of the airport’s geospatial data can improve. This data reliability has caused more people to rely on well-governed geospatial data for more purposes. These successes then lead to support for improved data governance, and the positive cycle continues.

2.2 Challenges to Data Governance

There are several challenges that constrain the effectiveness of the drivers described in the previous section. The following are the primary challenges airports have faced when establishing effective data governance and some methods that have been proven effective in overcoming them.

Silos are figurative barriers that confine data to departments, software, or individuals. They prevent the sharing and interoperability that yield the most benefits. Silos emerge and become engrained in organizations for many reasons, including the following:

- Departments within airports have specific objectives that, by definition, are different than those of other departments. Achieving those objectives requires departments to collect the resources they need, including data, but not necessarily to share it with others. The specifications one department requires may not be exactly what another requires, and then efforts to align them become a distraction. Funding tends to flow down from senior management to individual departments, so there are few financial incentives for departments to help each other. To overcome this, senior management can establish policy and incentives to promote data sharing across the organization.

- Work activities such as projects, project phases, tasks, and maintenance work orders are how most tangible assets get built or are changed within an airport environment. Typically, these activities have specific start and end dates and a finite budget. Data is an important input to and output of these activities. As with departments, however, there are few financial incentives to adjust data specifications or share data beyond that work activity. The result is that available input data often needs to be recollected, or at least reformatted, and outputs often do not conform to specifications or standards beyond those required for the work activity itself to be successful. Data standards and software that promote data interoperability to serve multiple work activities help ensure that data can be used for multiple purposes beyond the one work activity that produced it.

- Proprietary data formats are designed by vendors so that data works effectively within the software they sell. It is the value they provide to their customers, and they incur a real cost to create this value. It is natural that they would want to ensure that their customers and not their competitors have access to these formats. This tendency constrains data to that software (and its users), which then hinders sharing with others. Open data formats, such as the National Institute of Building Sciences BIM Council (formerly buildingSMART alliance) industry foundation classes (IFC), and ETL software that can translate between many formats help break down this barrier.

- Sensitive data, or data that could be used to cause harm, should be restricted to those who have a legitimate need for it. Unfortunately, the sensitivity of data and policies designed to limit its use are often used as excuses not to share data with those who may have a legitimate need for it. Refusal to share, improperly applied regulation, arduous training, excessive credentials, or simply lack of open communication about such data result in multiple barriers to data sharing, all under the guise of data security. These barriers can be so insurmountable that individuals will often bypass them to get data to those they feel have a legitimate need to know. The result not only undermines effective data security but also the collaboration of a data governance program. Identifying sensitive data and establishing procedures for sharing it that are backed

- by policy is essential in efficiently providing data to those who need it and preventing access to those who do not.

The pursuit of perfect data is futile, especially in the highly dynamic airport environment; however, it is a goal that should be pursued. Individuals who create and maintain data take pride in their work and may not want to share data they view as incomplete for fear of criticism. An organization can overcome this inclination toward closely held data by rewarding data sharing over data quality. This is not to say that data maintainers should not strive to improve the quality of the data they maintain, but they should share it, along with metadata that describes the quality of data at that time, where and when required. Early collaboration can further the pursuit of perfect data, as certain aspects of the data may be demonstrably more important to a third-party viewer than to the original data creator. A mesh of imperfect roadway data may illustrate the context of the other structures that surround a proposed development, thereby adding value to decision making—even if the data is less accurate than desired.

Resistance to change is a human trait that unfortunately hinders the shift toward treating data as an asset and, ultimately, in implementing an effective data governance program. “As creatures of habit, we often have difficulty incorporating new changes into our routines, no matter how beneficial they are for us” (Ryback 2017). Having committed champions and encouraging senior management to support a data sharing culture can help erode this resistance to change. Once a data sharing culture is established, it will become the new norm, fueling further data governance improvements.

Unfortunately, these challenges occur naturally in most organizations and humans. Conscious and committed efforts to overcome them, such as policy (Chapter 4), standards (Chapter 5), and procedures (Chapter 6), should be established and sustained as part of an effective data governance program.

2.3 Return on Investment

Airport senior management must invest the airport’s limited financial resources in a way that optimizes safety, operational efficiency, customer satisfaction, revenue, and other high-level objectives. Assessing the benefits that each investment choice—including data governance—will provide versus the costs that will be incurred is essential. Often, the challenge of such an assessment is that the costs are clear, but the benefits are not. This is not because of a lack of ample benefits, but rather the benefits may be largely intangible, meaning that they are difficult to quantify but fundamentally offer value that can be measured in some way. For example, it may take a surveyor 24 hours of time at a rate of $125 per hour, or $3,000, to identify obstacles to navigable airspace. However, it is difficult to quantify the benefit that the survey provides to air safety in terms of dollars. Without such an estimate, senior managers cannot make comparisons between the investment opportunities they must choose based on a financial benefit.

Their decision to invest in geospatial data governance is, therefore, often driven by regulatory mandates, passionate pleas by individual champions, or the desire to avoid the tangible costs made evident by past mistakes. Unfortunately, regulations that require data governance at airports have been limited, vague, and poorly enforced. The result has been a lack of geospatial data governance at airports, as shown in industry surveys and the research results documented in this report.

The Economics of Data Governance

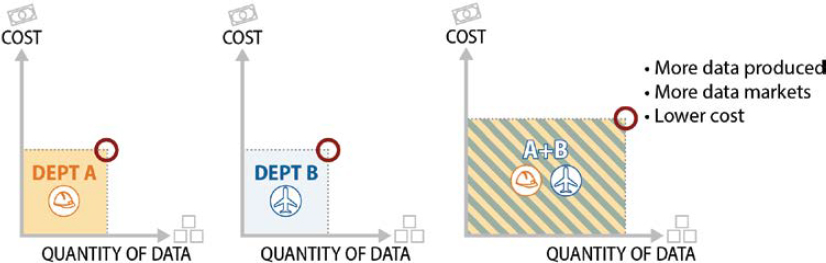

Figure 2-1 provides an example of the benefits of data sharing. Departments A and B on the left side of the graphic silo their GIS data. Each department only creates and maintains what the

department needs, and there is limited interaction between these departments. The right side of the graphic shows what would happen if Departments A and B coordinated their efforts and shared their data. By coordinating geospatial data needs and efforts, and sharing the data, more data can be produced at a lower associated cost.

Why is this? In Figure 2-2, Departments A and B have started negotiating with each other. As they continue these negotiations, a geospatial data curator is brought in to discuss the needs of these departments as well as other departments. Knowing the needs of both departments prevents the collection of separate siloed data. It also ensures the accuracy standards of all departments were met, and any of the metadata or attribution that was collected is done in a single mobilization versus separate mobilizations. By effectively utilizing the geospatial data governance program, in this instance, the organization reaches its optimal level of success.

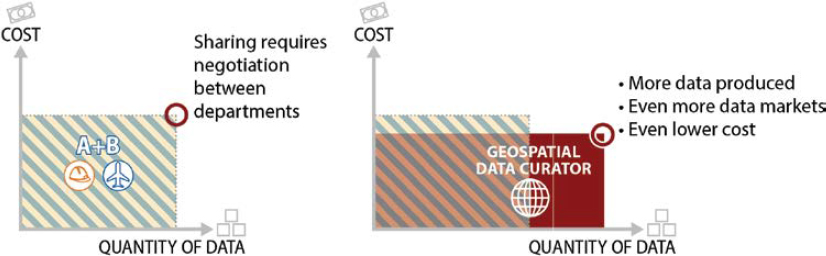

Cost-Benefit Estimates

The following section applies the principles illustrated in the previous section to estimate the costs and benefits of data governance. This will help make an achievable ROI more apparent to senior managers who can authorize the necessary funds. To do this, the costs and benefits must be quantified.

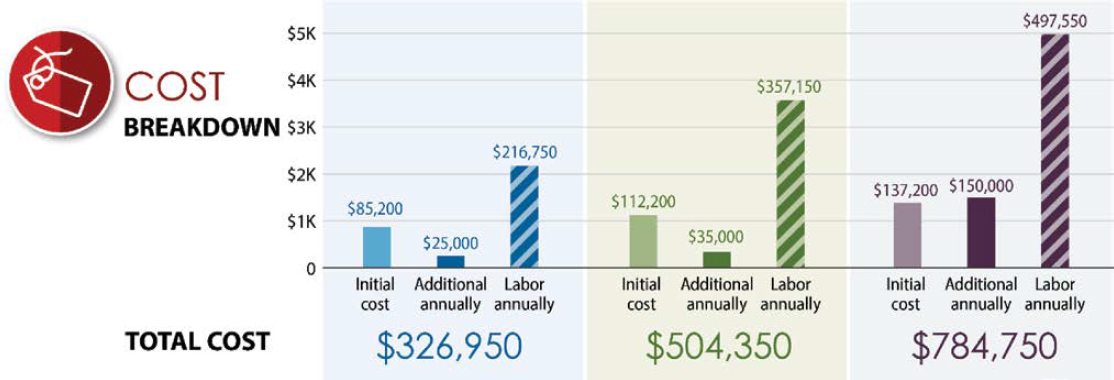

Because labor makes up the greatest expenditure, overall costs are relatively easy to quantify. Essential labor costs include two basic functions: data coordination and data analysis. Data coordination tracks those projects that require existing geospatial data for initial plans. The primary goal of data coordination is to ensure that updated deliverables are incorporated into the authoritative sources and distributed for use across the enterprise. Data analysis removes outdated records and seamlessly joins new and existing data, implements data changes, and conducts quality control on the result. Consultant fees for data collection and standards development are also easily estimated based on past projects and bids received.

Benefits are more difficult to quantify since many are intangible—such as improved safety or customer satisfaction. Benefits tend to accrue from efficiency and the provision of new capabilities. Efficiency gained by achieving objectives with fewer resources tends to fall into the following categories:

- Reduction of labor required to perform a task with the improved data that results from data governance,

- Avoided costs (non-labor) that would have been spent without the improved data, and

- Increased revenue that can be earned by increasing earning capacity of available facilities and assets.

New capabilities that the improved data provides were not possible before the data governance program was put into place. This can be thought of as improved effectiveness. In general, airports tend to have the same activities they have had for decades, so the opportunities to complete new tasks are relatively infrequent. An example is processing fees for Transportation Network Company pick-ups and drop-offs on airport property using geofences to trigger billing tracking and staging queue management, a relatively recent activity for airports.

Looking for these types of benefits among the most popular applications of geospatial data and technologies at airports helps to identify and quantify benefits that geospatial data governance can offer. Figure 2-3 shows the results of a survey on the types of geospatial data and technologies used at airports, which was conducted by TRB’s Aviation Geographic Information Systems and Data Joint Subcommittee of the Standing Committee on Aircraft/Airport

Compatibility (AV070) and the Standing Committee on Geographic Information Science and Applications (ABJ60).

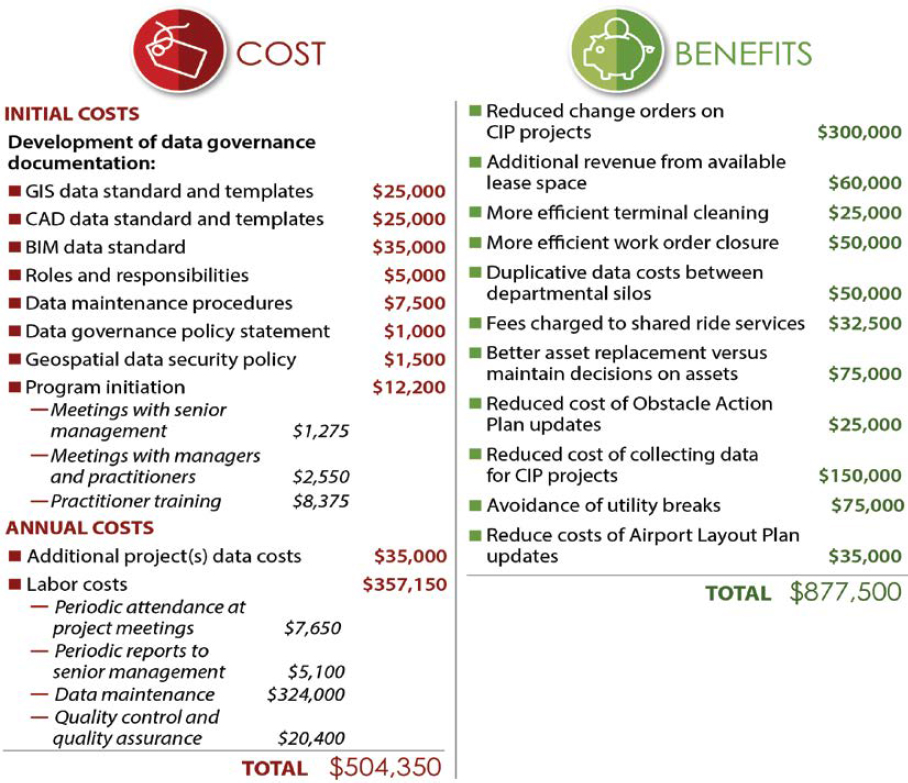

The result of this review is the following benefits shown in Figure 2-4, which can be quantified using reasonable assumptions regarding the level of these activities at a given airport size and complexity. These levels of activities can be adjusted based on the number of annual enplanements, square footage of interior space, CIP budget, age of airport infrastructure, management of multiple airports, and other drivers. The FAA uses several airport categories to communicate an airport’s size. For the purposes of this ROI, these categories are placed into a small, medium, or large airport classification as follows:

- Small—general aviation airports (national, regional, local, basic, and unclassified);

- Medium—reliever, non-hub primary, and small-hub primary airports; and

- Large—medium and large hub primary airports.

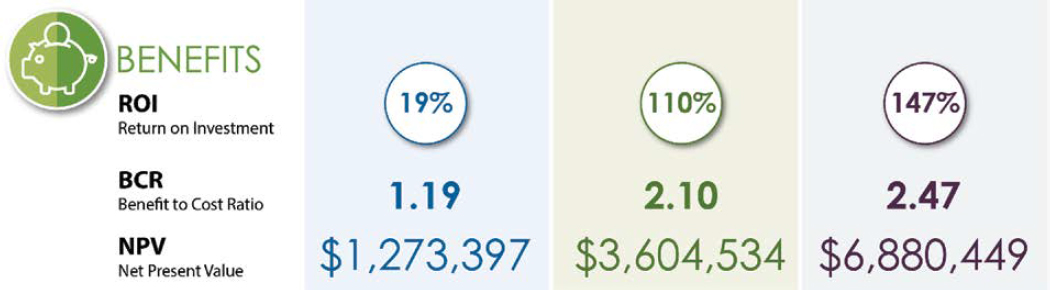

Taking the benefits and costs as estimated in Figure 2-4 into account over a 5-year planning horizon at a medium-size airport, results in a positive ROI of 110% or, alternatively, a benefit-to-cost ratio of 2.10 to 1. This assumes only half the benefit in year one due to program startup and a 3% annual escalation in benefit year over year. The costs included the initial costs in year one, plus half the annual costs in year one due to program startup and a 3% annual escalation in cost year over year. A 5%-time value of money was used in the net present value calculation. The analysis, illustrated in Figures 2-5 through 2-7, indicates that a positive ROI can be earned by investing in geospatial data governance and, therefore, is a good objective for airports to pursue.

Although the benefit-to-cost ratio of data governance programs may not be as significant as other geospatial data collections, the maintenance of data from those collections will ultimately fail without a proper data governance program.

The sources for the graphics have been provided as online spreadsheets that can be used to estimate geospatial data governance benefits and costs for any airport. In the spreadsheet, adjusting the numbers in blue to the particulars of a specific airport will adjust the numbers in black that are based on formulas. These formulas and the lists of costs and benefits can be adjusted as needed to more accurately reflect the specifics of a given airport. It should be noted, however, that although these estimates are an attempt to quantify benefits and costs for the sake of making investment decisions, they are based on assumptions and estimates, albeit ones based on research and experience, that are highly subjective. The goal should not be to determine a precise calculation of program benefits and costs; rather, the objective should be a sound basis for more informed decisions on the ROI of a geospatial data governance program.