Geospatial Data Governance Policies and Procedures: A Guide (2025)

Chapter: 10 Data Maintenance Plan

CHAPTER 10

Data Maintenance Plan

10.1 Data Life Cycle and Development

Geospatial data is not static but represents dynamic assets to be maintained, just like the physical assets they represent. From creation to depreciation, proper care must be taken to ensure data is usable and the value the data provides positively offsets the cost to initially collect and maintain it. The overview of a life cycle is creation, maintenance, and depreciation. An emphasis is put on data development because the deliberate conceptualization of data has the potential to increase the duration of the data’s usefulness and ease the other parts of the process.

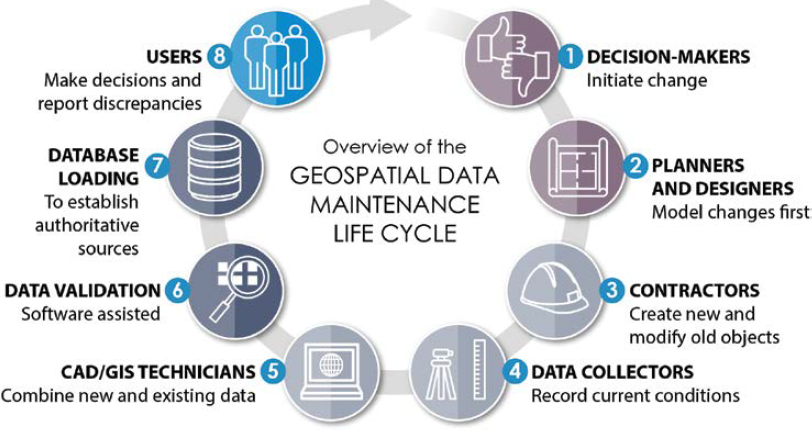

Data also can be created in specific environments (often referred to as development, testing, staging, and production) to ensure that data is perfected before entering a final production data set. Stages before the final production environment keep the final data set clean and free from extraneous data while also allowing for quality checks. The stage of the data becomes a part of the life cycle. Figure 10-1 shows an ideal geospatial data maintenance life cycle execution, pieces of which will be discussed in detail in this chapter.

Communication with the Executive Team

Communicating data needs to decision makers is a constant struggle confronting many organizations. The fast paced, ever-changing environment at an airport forces the executive team to balance budgets while reviewing and assessing priorities. Data maintenance needs should be presented to decision makers in a clear, concise, and compelling manner. The following are some of the considerations to factor in when presenting the data maintenance needs to the executive team:

- Understand your audience—Understanding the background and priorities of executive decision makers can allow tailoring of the message to their level of technical knowledge, which can sometimes be limited. Emphasize the aspects that are most relevant to their decision-making process.

- Define the objectives—Identify the problems that can be addressed by performing a data analysis. Can this data improve resource allocation, customer targeting, address safety, or security concerns?

- ROI—Executive-level decision makers want to make smart and informed decisions. By providing the list of benefits an airport will achieve in maintaining the data—and perhaps more so by showing the potential risks maintaining the data may mitigate—can help executive team members assess how truly beneficial this data is.

- Use visuals—Create visually appealing and easy-to-understand visuals that support key messages.

- Tie to organizational goals—Associate the need for the data back to organizational or strategic goals.

- Address potential concerns—Anticipate what concerns executive decision makers may have and address these proactively. For example, the cost of the data maintenance may be a concern but showcasing any mitigation strategies to reduce costs and potentially showing stories from other airports could provide benefit.

- Keep it concise—This can be a challenge as executives are often busy and have limited time for such a presentation. Create the information and present the key insights and actionable recommendations without getting “over their heads” in technical details.

Data Creation

Data should be created with intention. Before the first vertex is digitized, consider asking, “what will this data do for the organization?” Analyzing why the data will be created will help answer the rest of the life cycle questions, such as how the data will be maintained, how long it will be relevant, or who is the data champion or owner. While there may be ancillary information that is collected to create final data sets, being purposeful with which data sets (features and attribution) are maintained is critical to not overwhelming the organization’s limited resources and data needs. Collaborators should work together to decipher exactly what final data products the organization will commit to developing and maintaining. This will also help make the choice of which intermediary processed, but not truly final, data is also maintained in the geospatial data repository. The final data products will have undergone a small level of scrutiny for compliance with regulations before being incorporated into a geospatial system. They also might be created based on other data sets already in the spatial data repository and are therefore more likely to comply with many of the schema requirements. Some data is created from mapping features based on real-world features, while other data is created based on features already created from real-world objects. Having features created from other data is beneficial because established workflows may allow this newly created data to be entered directly into the staging or production geospatial system, omitting some of the earlier data stages such as development and testing.

Data Collection

Collection and creation are similar. The distinction is that creation contains more complete control over the data process than collection, and collection could be completed by a third party or created by a device that then requires post-processing. Data creation is done thoughtfully,

and seamlessly flows into a system whereas data collection requires a more thorough check for compliance with regulations (standards and policies) of the organization before being accepted and, more importantly, before being incorporated into the primary geospatial system. In data collection, anomalies will need to be worked out whereas in data creation, anomalies are spotted earlier or avoided altogether because it was worked on in one or more staging environments before being loaded into the live production environment.

When analyzing the data collection process for data created from a device, some important concepts to consider would be what collected information is exposed through processing in the final data. For example, an orthoimage could be created from drone imagery. To accept the orthoimage into the geospatial data warehouse, the data should be checked to ensure it is in the correct projection and its accuracy and resolution are as expected. Another example would be data collected from monitoring inspections (such as for pavement). The projection and accuracy of the collected data continues to be important to verify, but it is likely that resolution is not a factor because this would be vector-based data. Resolution checks are omitted and, instead, attribution and schema validations are applicable in this case. In both cases, it is highly likely that data will be created from the collected data. For example, building features could be created by digitizing planimetric features in stereo vision from the orthoimage, and patch features for pavement repair could be created from the pavement inspection data using CAD or GIS software.

Data Processing

Manipulating the created and collected data to fit the data needs even better is an ever-changing process. Arguably, up to the point right after data is retired, it is still being processed. It can be updated with newly collected data, or attributes can be changed to better suit uses and even augmented due to new information. Some processing functions might be more suited to occur in the creation or collection stage while other processing may be part of maintenance. One of the key parts of making data processing an element of geospatial data governance is ensuring that data processing routines are well documented for repeatability, and if an error is introduced, it can be reversed.

Conversion of Existing Data

The state of geospatial data at an airport can be vast. Not all existing data may add value. For example, the data owner may no longer find value in that data, data may have gone unmaintained and is out of date, or the program the data supports may have declined in importance. If no value is added, the data can be archived for historical reference. If value is added by converting data, a careful review should be conducted to ensure that the data fits into the schema. Building high-level workflows for data conversion will help ensure compatibility. Conversion processes such as georeferencing and developing crosswalk tables between platforms such as CAD to GIS will aid the transformation of data into the new system. ETL tools might be of assistance depending on the state of the data. Careful consideration should be taken to ensure attributes and spatial data accuracy meet the user needs and requirements of the new system before being finalized into a production environment.

Quality Assurance and Quality Control (QA/QC)

Testing for compliance with standards and policies is one of the most important operations to be performed on data to optimize the geospatial system. Quality Assurance and Quality Control (QA/QC) prevents “garbage in, garbage out” (GIGO), helps ensure analysis performed on the data produces reliable results, and users can depend on the GIS data to fit into their processes without breaking a workflow. Tests can be simple—making sure files open, confirming the

geometry type (point, line, polygon) is correct, double checking the projection is as expected—or complex, such as performing multiple accuracy tests on both feature geometry and attribute values. Measures of quality are fail-safes to make sure all the data collection, creation, and processing holds expected value. When considering the barrage of tests that data could be subjected to, data managers walk the fine line of being too accepting of incomplete or inaccurate data and overtesting to expose any potential flaws in the data.

Metadata

While often avoided, the main goal of metadata is to ensure data is documented to help users understand what the data is or is not and assist with future use. The key is not to overcomplicate metadata even though there are very rigorous standards (such as ISO 19115 and FGDC CSDGM) that assist in authoring and standardizing metadata.

A simple way to start is to write the easiest parts first (title, data fields that are automatically populated if using a third-party application) and save the more difficult narratives (abstract, description, detailed processing steps) for later. Ultimately, starting with a blank page is the hardest part because there are many potential pieces of information that can become overwhelming for the novice. For that reason, some minimal metadata (in compliance with CSDGM and ISO 19115) has been provided as separate electronic files further detailed at the end of this chapter.

Data Delivery

Data delivery often implies that data is going to an external source, but data delivery can mean data sharing between departments or data provided from an external source. Both are important to geospatial data governance. It is vital to ensure that data exchanged between departments is in a form of delivery that can be consumed by both the originating department and the destination department. Likewise, when data is coming into the geospatial system, its ability to be consumed into the existing interface should be checked. Even trusted contributors, internal and external to an airport, should undergo delivery checks to ensure the data is acceptable in its current form for comingling with other geospatial data. Simple reviews should suffice depending on the complexity of the system to which the data is being imported. Some more complex systems may require a staging area to ensure new data does not crash critical infrastructure due to issues with the feature geometry itself, its projection, units, or missing or improper attribute values.

Data Maintenance

Upkeep on finalized data is important to make sure the data continues to be relevant. Maintenance needs depend on the data set. Stable data sets will not need much maintenance. For example, orthophotography would only need maintenance if a new datum was needed or if the imagery was to be moved into a historical data set when new imagery is acquired. Building footprints are slightly more likely to be updated more frequently with new construction. The highest maintenance data sets are those that have new data added to them almost daily. Care should be taken with those data sets so that the attributes are updated correctly, and the geometries are changed as needed. Care should also be taken when updating features so that a static feature ID attribute value, which may track the maintenance history through an asset management platform, is not lost as data is updated.

One of the biggest challenges seen through the research at airports is data maintenance. Often, airports lack the staff to properly quality control the data and ensure the data is compliant with standards prior to acceptance. Even once the data is properly quality controlled and approved,

a large effort is needed to tie this data back into its previous authoritative data set, which can be overwhelming for small organizations or those with limited staff resources and training.

Maintenance is not only about adding features or updating attributes but also about making sure the data meets minimum standards and will not degrade the state of the existing data. Keeping good metadata assists in data maintenance because metadata can describe the business processes served by the data and the data QA/QC checks required for data acceptance.

Backup

Integral to the data life cycles (development, testing, staging, and production), backup could occur along any of those steps. A best practice would be to make a backup before major processing steps are taken or, at a minimum, when the data is finalized but not put into production. A backup creates a static data set that preserves the data before something happens. In other words, a backup can provide a worst-case-scenario fallback data set if a process damages the data or if a production environment is compromised. It can also provide a basis to compare changes made to the data to analyze the issues.

Archives

As historical backups, archives take backups to the next level and are a place to store depreciated data sets. They also store data sets that have been replaced with newer data collects or no longer serve a purpose in the geospatial system. For example, an outdated elevation data set could be kept in the archives for reference, but it would not be kept in the production-ready state in the working environment. It may be accessed rarely, and computing-intensive processes would likely not be performed on it. Another example might be obstacle analysis data that has been dealt with or has been removed. In this case, the obstacles could be moved into archives so they could be referenced in the future if needed.

Data does not belong in an archive until it is depreciated. But moving data from active storage to inactive storage for historical purposes helps minimize system storage and maximize system speed. Reviewing how often a data set is accessed will inform decisions about which data should stay available in an active environment and which may be best to move to offline storage.

10.2 Data Management Plan Elements in Relation to Airports

Although data management plans are scalable based on how many data layers an airport maintains within their geospatial system, data management is just as important if an airport has one or one thousand data layers. The processes, while greater in quantity and frequency, are still the same. It should be noted that an increased number of geospatial data sets is not necessarily synonymous with a larger airport. A small airport could have made decisions that led to maintaining more layers whereas a large airport might have opted for fewer layers. Data can be structured in different ways and may be considered less relevant than at another airport, all which impact decisions relating to intentional data creation and devising manageable data maintenance processes and schedules.

Keeping it simple may be key to balancing the value derived from having well-maintained data with the complexity needed to support such a program. Although adopting the newest technology for system functionality and data archiving may be tempting, the establishment and validation of a maintainable, low-effort workflow may reveal that the next geospatial system upgrade

can be deferred until truly needed. Furthermore, an organization’s successful administration of a basic framework can demonstrate a readiness to manage a more complex system.

One of the most important pieces throughout the data management life cycle is developing a data maintenance plan that allows for adjustments in the process and not only works but is sustainable over time. Developing a data management plan that requires numerous employees when there are limited employees available is unsustainable. Thinking through each part of the data maintenance life cycle and what is a sustainable activity is important. It is also important to commit to doing the initial data creation and collection work up front and carrying the effort through processing and quality checks. Being realistic about geospatial data’s life expectancy and depreciating historic data sets also will help develop a sustainable data maintenance plan. Finally, building data QC checks into the workflow is important for maintaining spatial accuracy and attributes consistent with adopted standards and policies.

10.3 Samples

The following samples are provided:

- Data management procedures and standards (Appendix C) and

- Metadata.

Reviewing a similar data set is advisable compared to starting with a blank slate when writing metadata. Although aviation-specific examples might not be readily available, the National States Geographic Information Council (NSGIC) provides a list of states’ geospatial clearinghouse and geographic information officer (GIO) or a geospatial contact. Each state’s geospatial data is graded, and this aids in searches for similar data sets (NSGIC 2023).