Geospatial Data Governance Policies and Procedures: A Guide (2025)

Chapter: 9 Roadmaps

CHAPTER 9

Roadmaps

Geospatial data governance roadmaps provide a plan to improve organizational effectiveness and efficiency by assembling geospatial data into actionable information that is reliably delivered to improve decision making. Roadmaps outline short- or long-term tasks to be accomplished and, depending on the state of the geospatial data governance program, could be simple or more complex tasks.

This chapter will explain how to engage collaborators and collaborator ownership to help accomplish tasks on the roadmap and will discuss some of the common tasks for geospatial data governance roadmaps.

To develop roadmaps, gaining and then keeping collaborator engagement is crucial. Collaborators help drive roadmaps, are often responsible for implementing portions of them, and benefit from the completed roadmaps.

9.1 Collaborator Engagement

Developing a team of involved individuals, internal and external to an organization, builds a foundation for preparing a roadmap to achieve effective geospatial data governance. Who should be a collaborator? There will be obvious choices, but sometimes non-traditional collaborators can provide key pieces of information. Collaborators are anyone who could be using geospatial data and helping with geospatial data governance. This could be a maintenance technician whose tasks are assigned location codes for more efficiency or an executive who is asked to provide funding for new geospatial software or data. There are many other examples of collaborators, and carefully crafting a team of engaged collaborators will strengthen the geospatial data governance roadmap by representing potential user needs more thoroughly.

Once a team of collaborators has been selected, developing RACI (responsible, accountable, consulted, informed) charts will help define the roles and responsibilities of collaborators and ensure the components of developing a roadmap are completed. Making sure collaborators are fully engaged at the correct times can be accomplished by showing how executing on the roadmap produces measurable results, contributes to ROI value, and helps drive organizational performance. It is likely that only a few collaborators will dedicate sustained effort and participate in the entire project life cycle, understanding and driving forward significant elements of the roadmap. Making sure that collaborators who are participating continuously can complete and support tasks helps to sustain forward momentum as a collaborator group.

As illustrated in Table 9-1, collaborator engagement and participation involve distinct roles at the forefront for various tasks. One constant, however, is the need for active sharing and collaboration on collaborator objectives and forging a clear and mutual understanding of user needs.

Table 9-1. Sample collaborator RACI chart.

| Project Leadership | Key Collaborators | Technical Delivery | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Projects Tasks | Executive Sponsor | Project Manager | Customer Experience & Media | Business & Leasing | System & Facility Manager | Technical Manager | Senior Analyst | Analyst |

| Phase 1: Requirements Gathering | ||||||||

| Needs assessment | R | A | C | C | C | C | C | I |

| Requirements gathering | R | A | C | C | C | C | C | I |

| Risk factors | R | A | C | C | C | C | C | I |

| Phase 2: Initial Project Design | ||||||||

| Specifications | R | C | I | I | C | A | I | C |

| Wireframe design | R | C | I | I | I | A | C | C |

| Use case/user story | R | C | C | C | I | A | C | C |

| User experience testing | R | C | C | I | I | A | C | C |

| Evaluation | R | C | C | C | C | A | I | C |

| Development | R | C | I | I | C | A | I | C |

| Delivery roadmap | R | C | C | C | C | A | C | I |

| R = Responsible | A = Accountable | C = Consulted | I = Informed | |||||

9.2 Key Elements of the Roadmap

The main goal of a geospatial data governance roadmap is to go from ungoverned to more, or fully, governed geospatial data. Increasing governance occurs by involving people, adapting to requests, and then implementing policies. Additional side benefits can also be realized by the team building derived from participating in and leading geospatial data governance development initiatives.

Performing a Maturity Assessment

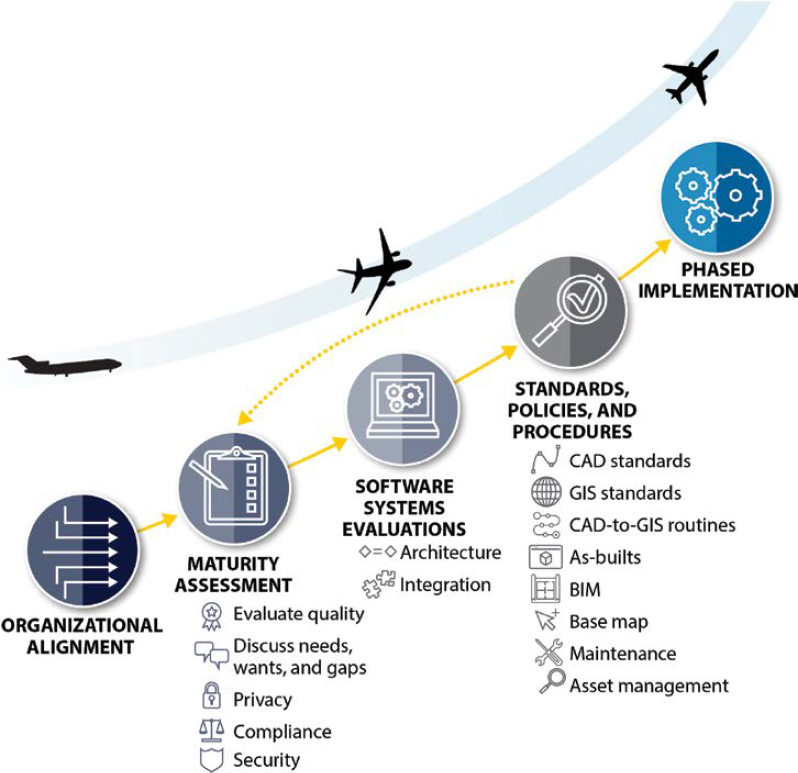

A primary step in building a roadmap is an assessment of the current state of the data and cultural backing for an effort of this type. Where is the organization within a maturity curve? Are there any mature geospatial data solutions in use in any departments, or is this all new to the organization? A maturity assessment verifies current geospatial data holdings and identifies data ownership support for key data groups. Start by looking to collaborators for what geospatial data they may already curate. Prepare to review all data files (CAD, Keyhole Markup Language Zipped [KMZ], PDF, GDB) but accept only the highest quality files into the geospatial data repository. Once data is collected, grade the quality of the data to see what could be improved upon and if any key features or attributes are missing. Assess the data to rank it by source, quality, and completeness of the data and present it to the collaborators. A secondary topic with collaborators would be their geospatial data wants and needs. These can be determined by performing a gap analysis on requested needs that are not currently being met. A basic roadmap illustration is shown in Figure 9-1. One important element to include is a feedback channel prior to implementation to ensure any lessons learned by adopting standards or from prior deployments are

applied to future deployments. Continuously improving the roadmap will help keep collaborators engaged as they see geospatial data governance contributing to the organizational effectiveness and efficiency over time.

Selecting Software

Secondary to assessing existing geospatial data and geospatial needs, evaluating software packages will be an important next step in the roadmap development. Software evaluation is secondary because knowing what functions are needed should drive the software evaluation, instead of allowing the potential software capabilities with the newest and most attractive bells and whistles to distract from the primary purpose of the software—delivering efficient solutions to address the defined needs. Attractive system features (bells and whistles) can be identified for potential later deployment to keep the focus on high-quality data maintenance processes and effective workflow processes while still fostering innovation.

Because software is at the core of the geospatial data governance program, the standards and procedures that govern the programs, hardware, and methodologies of a particular system must work together to deliver actionable information. The type of geospatial software selected to maintain data and disseminate information will influence the development of standards and procedures. There are typical commonalities to many airport geospatial governance programs, such as using CAD, GIS, BIM, and database software. However, each system is unique and is developed to address specific needs identified by the organization. The software and tools selected to

serve an airport’s unique needs and situation are often based on their organizational history, past software choices, and future objectives for geospatial data management.

Drafting Standards and Procedures

Detailed information about standards can be found in Chapter 5 of this guide. Starting from a blank slate when developing a geospatial data governance standard is harder than adapting an existing standard to suit the needs of the airport. Building steps into the roadmap to evaluate a standard for fit of use is crucial. Some standards may be more rigorous than needed and can be pared down to fit the needs of the collaborators.

There are few geospatial standards that are enforced in all aspects at airports. However, there are several historic standards that have influenced the approach for managing CAD and GIS data, and others are continuing to be developed, including BIM and indoor data. The key is consistent enforcement of standards or “loose affiliation” with standards compliance. Both approaches can occur within the same organization depending on whether rigorous standards enforcement would result in low ROI, there is a lack of data ownership, and/or data collaborators are making it difficult to achieve 100% standards compliance.

Procedures are more variable and individualized than standards in the sense that they are often step-by-step guides to help do repetitive tasks in a unique environment. Several common procedures at an airport have been identified with a workflow within Chapter 6 of this guide. Developing procedures will help standardize operating procedures in geospatial data governance to obtain the desired level of standard compliance. It may be helpful to start on procedures early in the roadmap and establish milestones to update them as the roadmap matures and more is learned about geospatial data governance.

Establishing and Enforcing Policy

Geospatial data governance policies were not found at airports at the time of publication, but including policies in a roadmap could help further geospatial data governance. Things to consider for a policies roadmap would be to set specific dates for establishing the policies, followed with a set timeline for feedback on the policies. Then, once all collaborators have reviewed the policies to ensure they are realistic, developing mechanisms for enforcement would be the next step on the roadmap. Policies have been covered in more detail in Chapter 4 of this guide.

Carrying Out Data Maintenance

Data maintenance can be an afterthought if not included in the roadmap planning effort. Planning for routine data maintenance in the roadmap will help ensure airports are able to properly maintain their data. Refer to Chapter 10 for more details on data maintenance procedures. To ensure common geospatial data maintenance activities are included in the governance roadmap, annual data maintenance needs can be projected by estimating the effort needed for annual maintenance and ongoing data updates, based on assumed update frequency for commonly used data layers. An estimate for a small airport’s annual airside, landside, and facilities GIS data update effort is provided in Table 9-2.

Good planning also includes estimating deprecation dates for replacing geospatial data that will become outdated over time. An example could be a plan to update elevation contours in an area that was modified by construction. The preconstruction contour data becomes out of date once the construction project begins. For effective geospatial data governance, airports should plan on developing new elevation contours within a given construction area or develop all new

Table 9-2. Small airport annual estimated GIS maintenance effort.

| Data Group | Data Layers in Each Group | GIS Layer Count | Annual Edit Hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| Airfield | Airport Operations Area (AOA), Non-Movement Area, Airfield Light, Airfield Sign, Apron, Blast Pad, Displaced Threshold, Helipad, Marking Line, Marking Area, Centerline, Runway End, Shoulder, Taxiway Segment | 15 | 400 |

| Airspace | Obstacle, Obstruction Area, Obstruction ID Surface, Tower (Freestanding Towers, Not FAA Air Traffic Control Tower [ATCT]) | 4 | 20 |

| Cadastral | Land Use, Property Boundary, City Limit, Flood Zone, Lease Area | 5 | 120 |

| Environmental | Contamination Area, Hazmat Storage Area, Sample Collection Point, Vegetation Area, Noise Contour | 5 | 26 |

| Geodetic | Cost Center Boundary, Elevation Contour, Spot Elevation, Control Point, Image Area | 5 | 52 |

| Manmade Structures | Building, Construction Area, Fence, Gate, Boarding Bridge, Tunnel, Landside Sign | 7 | 84 |

| NAVAIDs | NAVAID Critical Area, NAVAID Equipment | 2 | 8 |

| Security | Restricted Access Boundary, Security Identification Display Area (SIDA) Boundary, Sterile Area | 3 | 48 |

| Surface Transportation | Parking Lot, Road Centerline, Sidewalk | 3 | 32 |

| Utilities | Electric, Water, Stormwater, Sanitary Sewer, Gas, Fuel, Plumbing | 60 | 608 |

| TOTAL | 109 | 1398 |

contours for a much larger area if one seamless elevation contour data set is needed. While maintaining some historical data is nice for reference, being sure the base layers (imagery, light detection and ranging [lidar], and planimetric data sets) are kept up to date is important to be responsive to potential data requests. These base layers may be appropriate to plan for scheduled reoccurring data harvests or updates. The schedule for updating data would be dependent on the frequency of change at the airport. Most of the base data sets are expensive to collect and maintain, so putting them on the roadmap will ensure they are budgeted, and an update schedule is realistic and achievable.

9.3 Publication and Dissemination

Sharing the roadmap within the organization will help keep everyone well-coordinated and accountable for the next steps. It is also important to periodically revise the roadmap to show progress and adjust for roadblocks to progress. Devising a plan for publication and dissemination of the roadmap to collaborators is an advisable part of the roadmap itself. Incorporating a feedback cycle helps implementation while also keeping collaborators involved.

9.4 Change Control

Roadmaps, like geospatial data governance, are malleable. Having a plan to update and revise the roadmap is important, as a successful roadmap accomplishes the tasks and then moves onto the next stage of the roadmap. Some tasks might need to be pushed back while others are pulled forward due to unforeseen circumstances. Scheduling review sessions and documenting changes that occur during those review sessions will help track not only variations but progress. There are a few ways to change the roadmap as the deviations are noted or changed at certain points (such as once a month or after key collaborator meetings). Since change is a natural part of roadmap upkeep, accountability could be built into the team driving the roadmap objectives to achieve milestones through monthly calls, accountability tools, and reports to airport executives and other collaborators. With any of these methods, or even a combination, it is important to note the changes and reasons for the change to help better calibrate future roadmap planning adjustments. A simple change log with the date, the item changed, and possibly a reason for the change, will allow collaborators to easily identify changes between versions of the roadmap.

9.5 Version Management

The first version of a roadmap is not likely to be the same as the final roadmap. Roadmaps are meant to be dynamic, not static. Revisiting them annually, or more frequently, is good practice to ensure the roadmap is current and helps drive future progress. Documenting the version of the roadmap will track the history of changes. The obvious example would follow typical software versioning with 1.0 or 1.1.5 for smaller version changes. Another example might be documenting roadmap changes by stating years and months before a version number. The second change in May 2022 could be 2022.05.02. The version number should at least be in the file name and put on the roadmap if printed posters are made as well.