Geospatial Data Governance Policies and Procedures: A Guide (2025)

Chapter: 8 Data Security

CHAPTER 8

Data Security

A key objective of data governance is to provide information to people with a legitimate need to know and to restrict it from those who do not. While the solution to effective data security is largely technical, much of the challenge is defining what data needs to be secured, determining the degree and method of security, and educating collaborators on what they need to do to protect sensitive information in their care.

Data access can be divided into internal and external considerations. Internal conditions govern the access to the data servers through the internal network. External considerations include the cybersecurity rules and regulations for sharing data outside of the organization. The line between internal and external data access is often blurred by the ability to access internal networks through remote connections. To clarify the distinction, internal refers to data that is accessible to airport employees, consultants, and contractors, while external data would be defined as publicly available data. The Council for Geospatial Data Governance is responsible for designing which data is accessible to whom.

Physical data security, historically, is the safety of on-site data storage devices and a system data backup in a different location in case of a disaster. Regarding offsite and virtual data storage, “a different location” can be a cloud server in a different state. These cloud storage facilities bring a new level of security concerns because they are routinely targets for international cybercriminals intentionally searching for backdoors into servers to bring down major systems. There are additional concerns. Consider a disgruntled employee at these facilities who may have access to take down data and servers.

Cybersecurity attacks from other countries are becoming more prevalent, and U.S. airports should be prepared for this. While many airports do not want to talk about cybersecurity issues, there have been known issues and this emphasizes the importance of bolstering security practices at airports. The focus of this chapter will be on data security best practices as they relate to airports’ geospatial data.

The types of information being collected and the nexus of activity that can be gleaned from location data is reaching new heights. Events, such as security breaches, sensor readings, safety infractions, or the location of people or movable assets at a particular point in time, are increasingly tracked in today’s powerful computing platforms. The result is “big data” that must be securely governed to ensure that it is collected, processed, and disseminated in a timely manner to those who need it, and minimizing risk of data theft or corruption by unauthorized users.

The goal for data security has been well stated: “to protect information assets in alignment with privacy and confidentiality regulations, contractual agreements, and business requirements” (Henderson, Earley, and Sebastian-Coleman 2017).

Geospatial Data Identification and Classification

Geospatial data can be collected and enriched through a variety of different technologies to deliver meaningful, actionable information provided with context. Organizations need to prioritize protecting that data by implementing robust security controls. To help explain how organizations can better manage and reduce cybersecurity risks related to geospatial data, the National Institute of Standards and Technology Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF) can be a useful reference (NIST 2022). As described in the NIST CSF, the first step to protecting an organization is through the identification of assets. Thankfully, this process is no different for identifying and securing geospatial data. Once geospatial data has been identified, it must be properly classified to determine which controls are to be implemented. If specific geospatial data has been identified as sensitive security information (SSI) (TSA 2020), it is suggested that additional security controls are selected and implemented based on governance requirements. It is important to understand that SSI data may be present within spatial and non-spatial data, depending on the context.

SSI data can be included in geospatial data ranges from critical infrastructure (fuel, electrical, power needs, secured facilities) to personal identifiable data, with a host of items in between. Cybersecurity safety measures are often determined by following a criminal line of thinking—how would a criminal use or benefit from this information? Looking to examples of past weaknesses can help as well. The definition of SSI, “information that, if publicly released, would be detrimental to transportation security,” implies that attribute data which is not unique to GIS may also include SSI (TSA 2020). Examples may include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Phone numbers,

- Email addresses,

- Internet protocol (IP) addresses,

- Proprietary information,

- Social security numbers,

- Financial records,

- Organizational budget data,

- Health records,

- Student records,

- Research data, and

- Biometric data.

Although some of these examples of potential SSI geospatial data may not seem critically important, this data absolutely could be used to exploit an airport by malicious individuals, if given the opportunity. From a governance perspective, the following data governance roles would be clearly defined and established within an organization:

- Data curator—Responsible for maintaining confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data;

- Data steward—Responsible for ensuring data quality and storage; and

- Data producers—Responsible for ensuring data compliance.

Unfortunately, due to staffing constraints, establishing data governance roles is often a challenge for most organizations. Organizational IT departments often end up assuming all data governance roles in these circumstances.

Geospatial Data Security

Geospatial data, residing within and external to GIS, is extremely valuable to airports and a variety of airport collaborators. Geospatial data can contain a variety of different types of data sets, including raster, vector, and associated attributes. Additionally, metadata associated with each data set is where critical author, accuracy, precision, projection, datum, and source sensor information is documented. Without accurate and contextual geospatial data, airports would

not be able to plan, design, monitor, maintain, and operate effectively. For these reasons, airports must actively engage in protecting their geospatial data from both internal and external threats.

NSDI

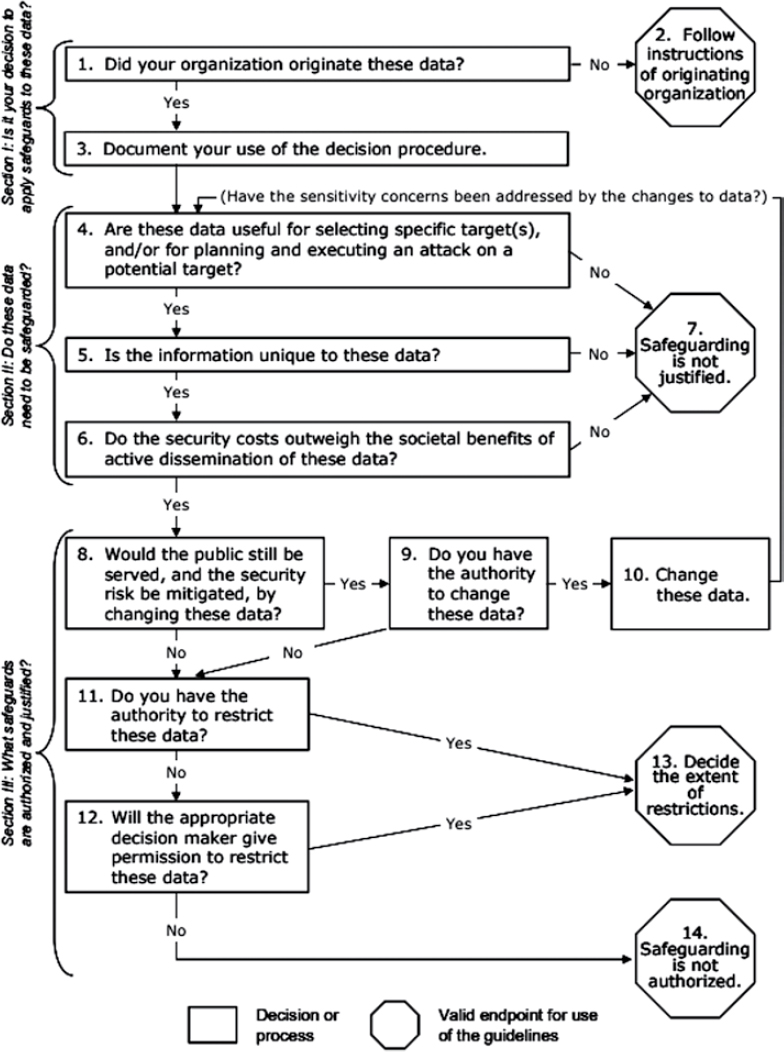

NSDI, a program overseen by the FGDC, developed a standard procedure to identify sensitive geospatial data, information, and content that pose a security risk. It also guides decisions to review sensitive information during reassessments of geospatial data safeguards and provides a method for balancing the security risks and the benefits of geospatial data distribution (NSDI 2005). As part of this guide, NSDI developed a decision tree (depicted in Figure 8-1) to evaluate data accessibility in response to security concerns. A similar process can be developed or adopted by an airport when evaluating data security.

Geospatial Data Security Best Practices

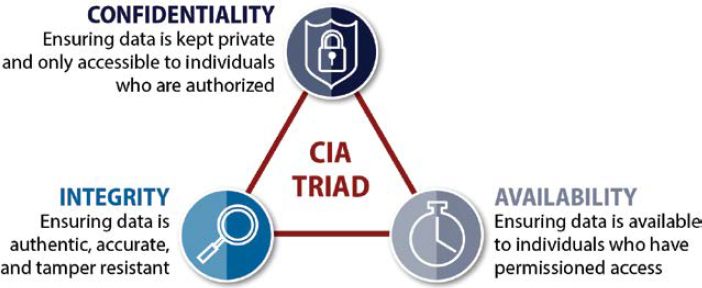

From a cybersecurity perspective, geospatial data security can be achieved by maintaining data confidentiality, preserving data integrity, and ensuring data availability as shown in the Central Intelligence Agency triad, Figure 8-2.

The controls for each element of the CIA triad are as follows:

- Data confidentiality controls

- Encryption at rest, transit, and process;

- Authentication and authorization access controls;

- Multifactor authentication (MFA); and

- Privileged account management (PAM)/privilege identity management (PIM).

- Data integrity controls

- Integrity monitoring (operating system, directory, application, file, geodatabase, hypervisor, etc.);

- Security logging/auditing; and

- Consensus and storage immutability (blockchain, directed acyclic graphs, etc.).

- Data availability controls

- Redundancy (Internet service provider, network, storage, power);

- High availability (application, database);

- Backups (full, incremental, snapshots, offline configurations, distributed storage);

- Data loss prevention (server, endpoint, perimeter); and

- Distributed denial of service (DDoS) protection.

Additional Geospatial Data Security Suggestions

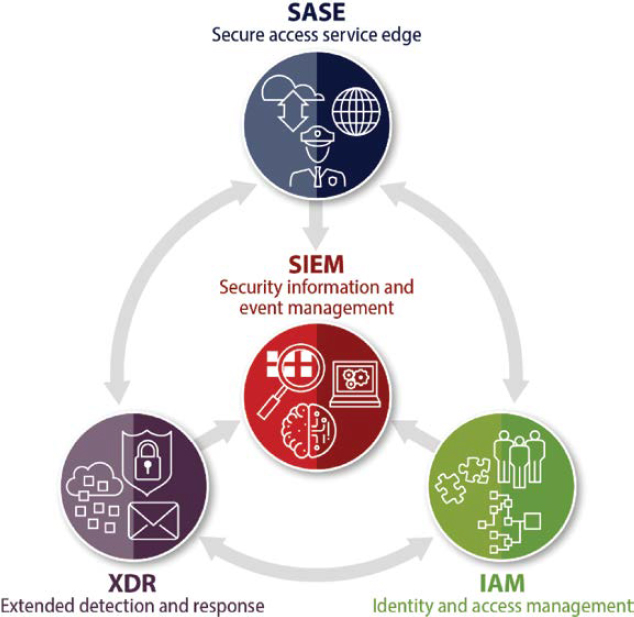

In addition to the variety of data-specific controls highlighted, it is also important to have a secure enterprise solution architecture. A secure enterprise solution architecture will not only further protect geospatial data, but also improve detection, response, and remediation capabilities. As previously mentioned, comprehensive cybersecurity encompasses numerous domains. With this extensive scope in mind, modern cybersecurity controls should include user, device, workload, cloud, and network protection. The interrelationship between these controls is depicted in Figure 8-3.

Evolving and Emerging Technology Considerations

The current aviation industry has several technologies being planned or implemented that support airport operations, planning, and maintenance—all rely heavily on geospatial data. This reliance often elevates the associated availability and integrity requirements to ensure connective

services maintain continuity of operations obligations (e.g., service level agreements) in a secure manner. Examples of these technologies include the following:

- Situational awareness (SA) platforms

- Physical security information management (PSIM) systems

- Video surveillance systems (VSS)

- Physical access control system (PACS)

- Perimeter intrusion detection systems (PIDS)

- Properties, tenant, and concessions planning

- Digital twin

- Building management and automation

- FAA regulatory compliance tools

- TSA regulatory compliance tools

- Passenger flow analytics systems

- Asset tracking systems

- Autonomous vehicles

The expanding operational use-cases and associated reliance on geospatial data make it necessary to consider the recent threat landscape, including current tactics like ransomware attacks. Outside of implementing the previously mentioned modern technology controls, system design, maintenance, and monitoring can be conducted using best practices and reduce surface area of incidents as much as possible through geospatial data service isolation, system federation, and GDB segregation.