Geospatial Data Governance Policies and Procedures: A Guide (2025)

Chapter: 6 Procedures

CHAPTER 6

Procedures

This chapter describes typical airport geospatial data maintenance procedures. Such procedures are a critical part of geospatial data governance. These procedures have been generalized, as the role of data maintainer will vary from airport to airport. They are meant to provide a framework that can be modified based on the organizational structure of each airport.

Airports have many business needs for spatial data that range in complexity based on the data’s physical extent, number of features, update frequency and cycle, and number of intended users. Each of these business needs or GIS use cases requires specific geospatial data governance procedures that rely on the coordinated efforts of multiple collaborators within an airport organization. Data quality suffers when collaborators who contribute data for dissemination to their organization do not understand what is expected of them or do not appreciate the value of the data to the overall organization.

The challenge of identifying and organizing the methods and means to recognize and track project-related data changes occurs early in the planning and design process. Large and small projects involve maintaining, upgrading, or adding infrastructure assets daily. Determining the location, extent, and degree of infrastructure granularity that an organization wants to track should be the primary objective. It is essential for an organization to understand that these projects rely on existing geospatial data for planning and, when completed, will impact geospatial data maintenance and distribution. Developing data standards and holding contractors accountable for the delivery of data in compliance with these standards is an organizational culture shift from the norm.

The following are common geospatial data maintenance workflows that document high-level procedures to maintain data required by multiple or highly ranked airport business needs. Although the examples may not be all inclusive of data that an airport maintains, these processes and workflows can be used to support data needs to address topics such as security breaches, environmental and noise concerns, parking data, and many other use cases identified by an airport.

The design of these workflow illustrations assumes that data standards have been developed and enforced with the end result being the migration of project data into a geodatabase (GDB). If the airport has not yet implemented GIS, the process would end where the data is used to update a main CAD file series (i.e., airfield record drawings, CAD lease exhibits, etc.).

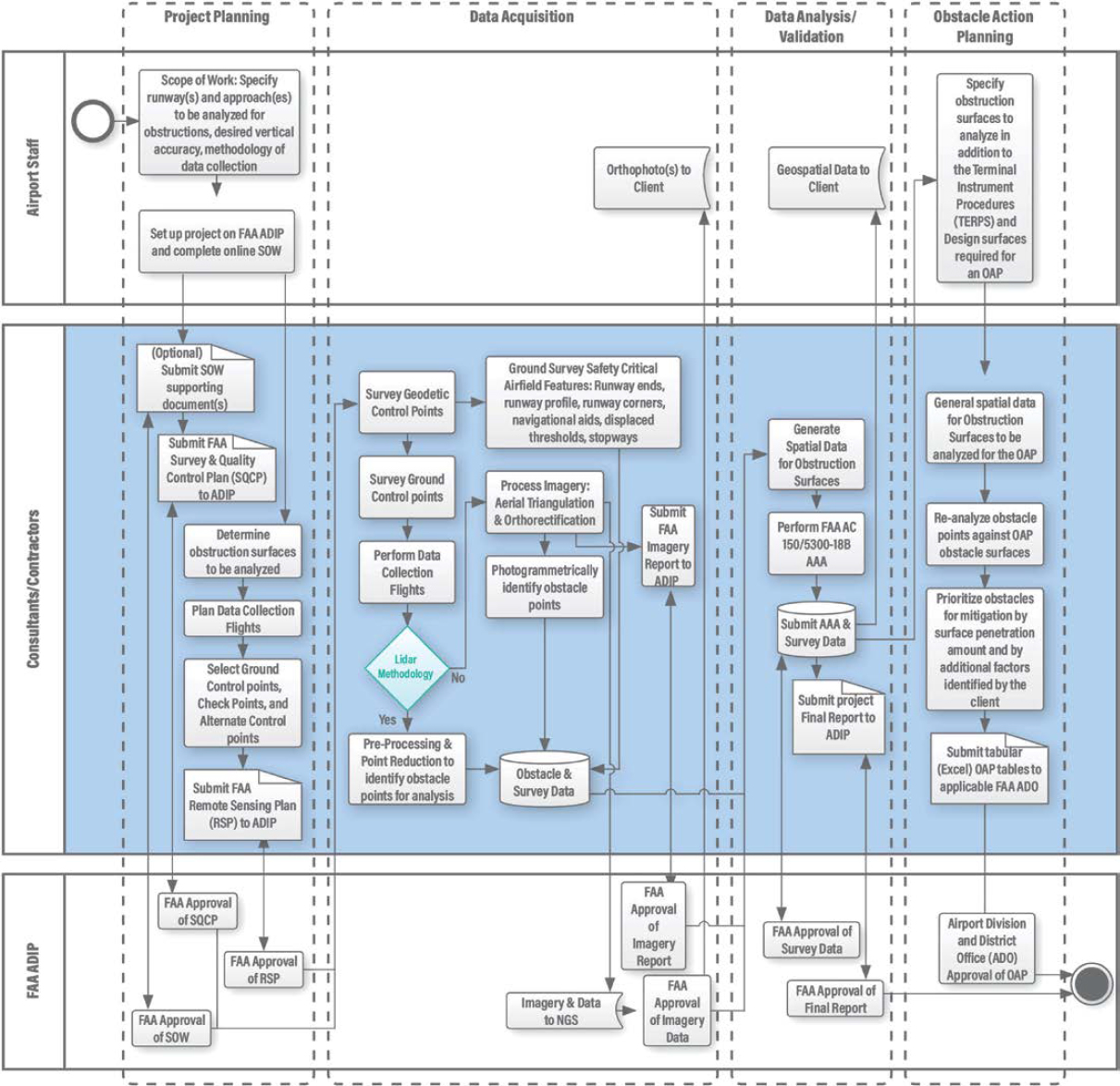

These workflow diagrams have been developed using BPMN, which illustrates workflows in a chronological manner from left to right. Rows indicate organizational roles that are responsible for conducting the processes they contain. A legend of BPMN symbols is provided in Figure 6-1. Each of the following sections ends with a corresponding BPMN.

6.1 Base Maps

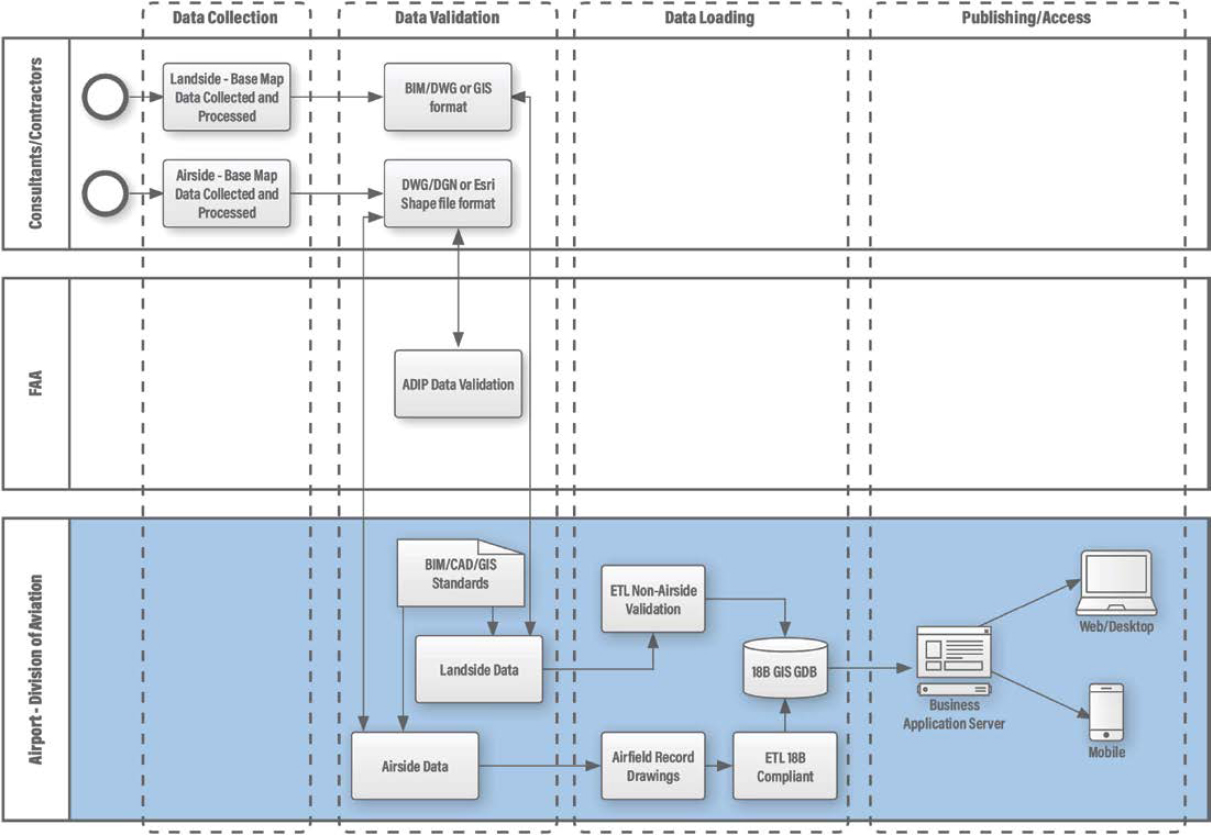

Base map data depicting airside and landside conditions exterior to facilities is developed to support many airports’ business processes such as an airport layout plan (ALP) and regulatory requirements such as the FAA’s AGIS and ADIP. It is not uncommon for an airport to have multiple data sets: one airside-focused, which goes on to the FAA and one that is more airport-centric and may contain details on utilities, landside data such as roadways, and even environmental or noise information.

The following base map data maintenance workflow, as depicted in Figure 6-2, is initiated by the airport developing a request for proposal (RFP) or request for qualifications (RFQ) that includes contract language requiring that project deliverables be provided in compliance with airport-defined data standards (i.e., BIM, CAD, or GIS). Digital data deliverables can be provided in different formats ranging from BIM, Autocad DWG (CAD files consisting of 2D and 3D vector drawings), Bentley DGN (CAD viewer), or GIS format. Airside deliverables in the form of completed survey projects would be required to meet FAA data submission and review procedures defined as part of ADIP.

Prior to loading data into either airfield record drawings or a GDB, the data is required to pass an ETL validation step in alignment with established BIM, CAD, and GIS standards. If the input data fails the validation process, a report is generated and submitted identifying the errors required for resolution prior to resubmission. Upon approval, data is then processed using a separate ETL procedure to migrate the original source data into an 18B GIS GDB. Data can then be assembled into a user-defined application within a business application server and distributed to defined users via desktop, web, or mobile device.

6.2 Floor Plans

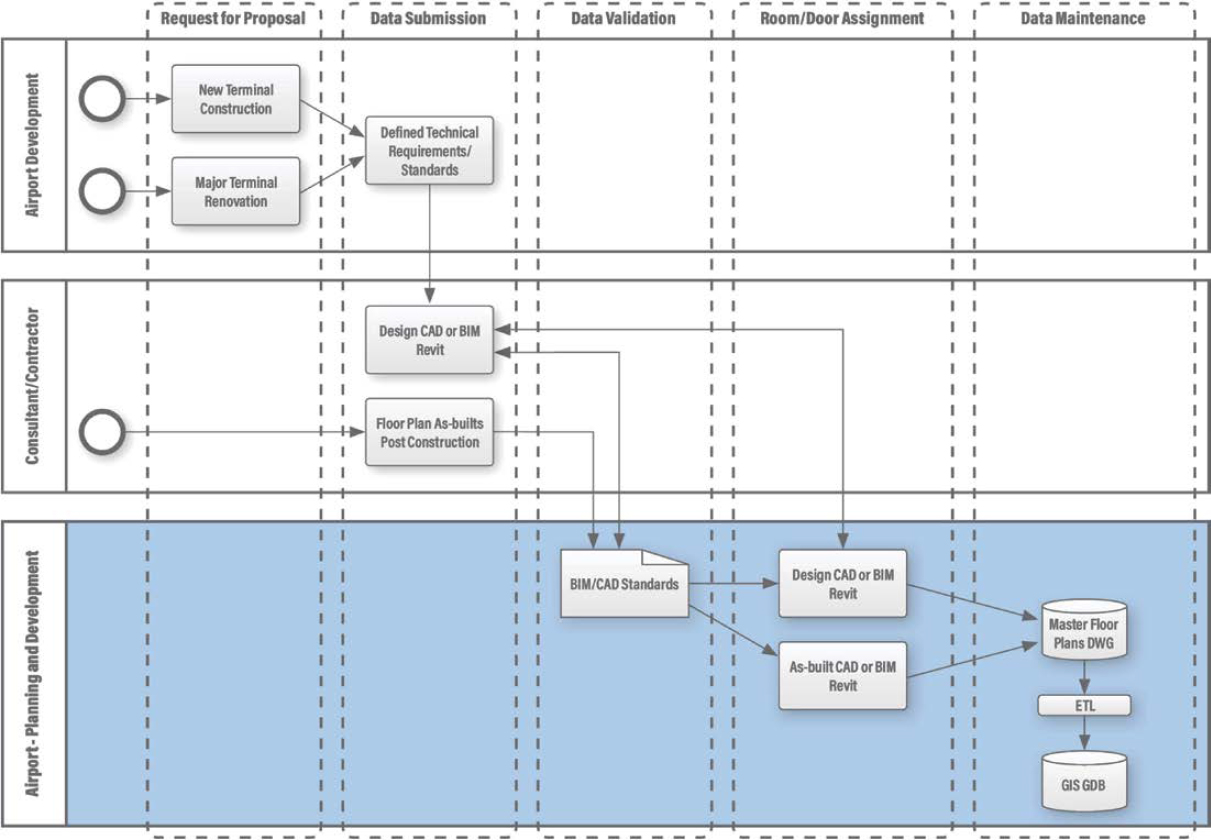

Floor plan data depicts walls, doors, windows, stairs, elevators, escalators, moving sidewalks, and other features that define interior space. The following workflow diagram is focused on the data maintenance update process of floor plan features associated with a new or major terminal renovation project. Whether in GIS, CAD, or BIM format, floor plans provide the basis for interior renovations, asset management, and wayfinding in large facilities and are essential for security and life-safety response.

In today’s environment of constant structural change, including constructing new airport terminals or rehabilitating existing terminals, it is extremely difficult to keep terminal floor plans up to date. A geospatial data governance best practice to support this data maintenance workflow is for the airport owner to first develop and include technical requirements and a data standard submission policy in the RFP or RFQ and subsequent contract documentation.

This policy would require the delivery of both design data (i.e., 30/60/90/Final stages of delivery) and post-construction as-built files in a standardized format. Data is then validated against the defined standard. If the input data fails the validation process, a report is generated identifying the errors required for resolution prior to resubmission. Upon acceptance, the engineering or another responsible data maintaining department would identify and provide both room and door number codes. This information would then be provided back to any collaborator to use during the construction phase.

The preliminary design data can be loaded into an authoritative floor plan series of digital maps that can be used for emergency management and other project tracking activities. Upon completion of the project, post-construction, as-built files would replace the preliminary design geometry and attribution. Data received would be processed using an ETL procedure to load the floor plan details into a GIS GDB to facilitate data distribution and use. This process is depicted in Figure 6-3.

6.3 Interior Space

Interior space data depicts how interior and exterior space is designated and used. The following workflow diagram is focused on minor tenant or division of airport (DOA) space updates that could range from a renovation of a concession space for a tenant to reconfiguration of DOA office spaces. Aside from the architecture structure changes, much of this is through lease and license agreements that generate a significant portion of most commercial airport revenue. Space data also identifies the destinations needed for most wayfinding applications. For these reasons, the governance of lease-based interior and exterior space data is particularly important at airports. Unfortunately, the dynamic nature of airports and the number of collaborators involved can make this data particularly challenging to maintain.

In a similar fashion to the terminal floor plan data maintenance workflow, changes to the interior structure of rooms and lease areas are frequent and, in many cases, details are not well communicated to the data maintainers. Changes to interior spaces can be initiated by a tenant or an airport business unit. Most airports have some type of tenant modification application process that requires the lessee to formally request and submit plans for approval, which provides a governance mechanism to track changes to lease spaces. Lease spaces can include concessions, airlines, and other businesses that are leasing hangers to support their services.

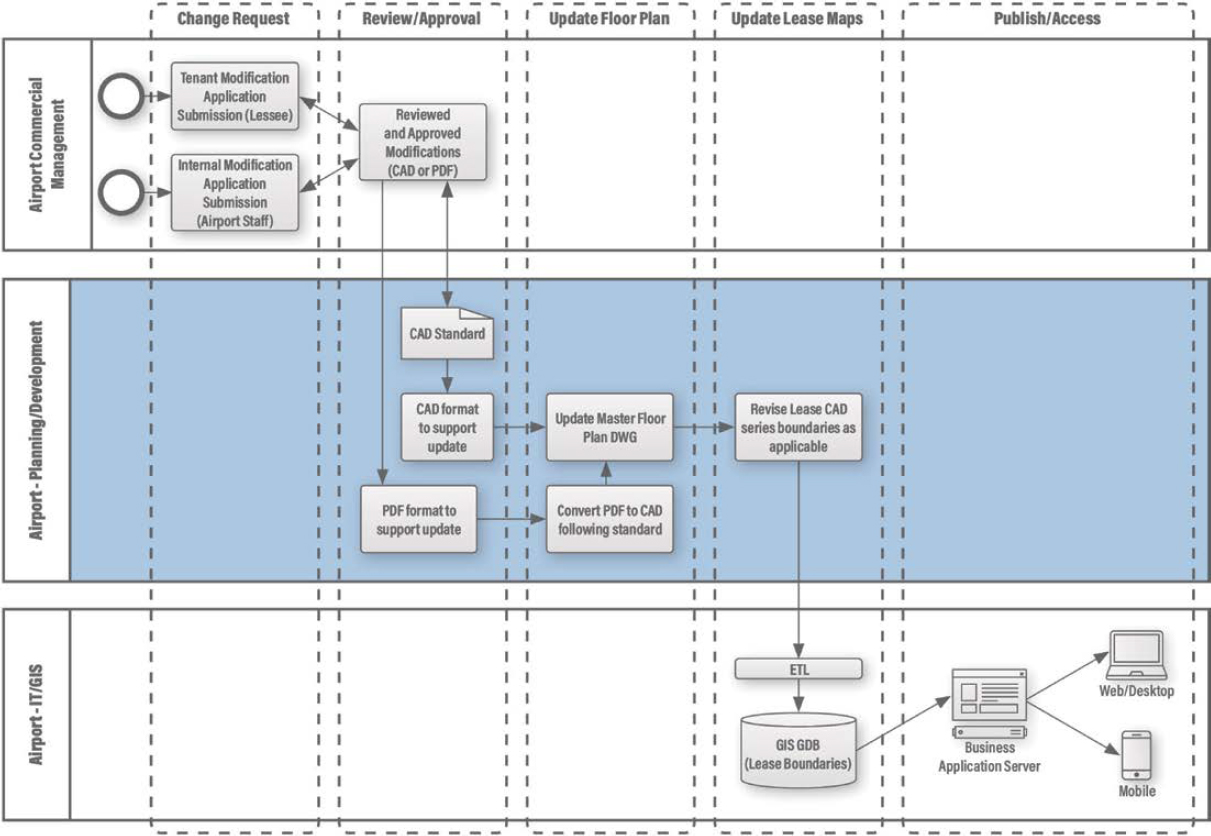

Tenant changes include both structural and business changes and can simply be a lease transfer to a new business, which requires space-attribute updates. In the case of airport business unit requests, these have been found to be less formal and much more difficult to track than tenant changes. Figure 6-4 begins with the formal establishment of change requests for both tenant and airport business unit space modification application submission.

Applications are administered through a review and revision procedure until an approval is received. Data submitted is typically provided in CAD or Portable Document Format (PDF) format. In many cases, the staff of the planning and development business unit is responsible for maintaining both the floor plan and lease map, which serve different purposes and are therefore separate digital map products.

CAD data is validated against the CAD standard, and PDF files are converted to CAD format following the standard. If the input data fails the validation process, a report is generated identifying the errors required for resolution prior to resubmission. Upon completion, structural geometry changes are loaded into the main floor plan file to reflect the changes in walls, doors, windows, and other related features. The update procedure mimics that described in the previous floor plan workflow, which is documented here for minor lease-based updates. Additional CAD layers that include lease boundaries and lessee attribute details are then loaded into a lease map series, which includes polygon geometry for lease spaces and other non-lease spaces throughout the airport. The lease map data is then loaded into a GDB using an ETL procedure. Lease area

features are then assembled into business function applications and distributed to defined users via desktop, web, or mobile device.

6.4 Utilities

Land and facility-based utility assets and infrastructure have been historically difficult to map and manage. Land or ground-based utility infrastructure is often buried, and records which are generally dated, are often not updated when infrastructure has been abandoned or removed. The accurate location information of buried utility infrastructure is essential in the planning and design process to help eliminate accidents, schedule delays, and cost overruns caused by mishaps—such as line outages—due to excavation activities. It is important that these assets be mapped to be managed properly. The need is pervasive across many industries, which is what has prompted the creation of the subsurface utility engineering (SUE) profession. The challenge for airports is that collecting data about existing buried utilities is complex, often requires assimilating data from multiple sources and agencies, and still may require field investigations to obtain an accurate utility atlas.

Facility-based utility infrastructure such as mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) may have valves, major HVAC equipment, and electrical panel locations noted on hardcopy maps, but, in general, digital representation is nonexistent, especially for small and medium airports. As large numbers of airports across the country continue to grow—requiring major terminal renovations, or the construction of brand-new terminals—the need to capture, process, and manage this utility infrastructure is increasingly important to initiate a complete life cycle management system.

As noted, existing underground utility assets and infrastructure are difficult to map and require subsurface mapping techniques that can include ground penetrating radar (GPR), electromagnetic location (EML), and potholing (excavation to reveal the utility location), which remains a common method of geolocating underground structures. As projects related to maintenance, replacement, or new installation of underground utility infrastructure are initiated, it is in the best interest of the airport to verify or capture the location and depth of utility assets and infrastructure to increase the quality of existing utility mapping.

This data can be collected with Global Positioning System (GPS) technology, closed-circuit television (CCTV) camera, robotics, or post-construction as-builts. Above-ground and facility-based utility infrastructure can be acquired with GPS, aerial photogrammetric methods, Indoor Positioning System (IPS), or post-construction as-builts. As-builts can be provided in many forms, with CAD and, recently, BIM being a common deliverable. Contract documents should define the required deliverable format, whereas PDF files would be an undesirable format to support data maintenance, as additional data translation is required. Additionally, the FAA’s utility schema is limited to very generic attribution fields for the use cases of what an airport needs. The airport should consider additional attribute fields that may be needed for utilities and if it is necessary to have networked utilities that can show what valve may turn off service to what lines.

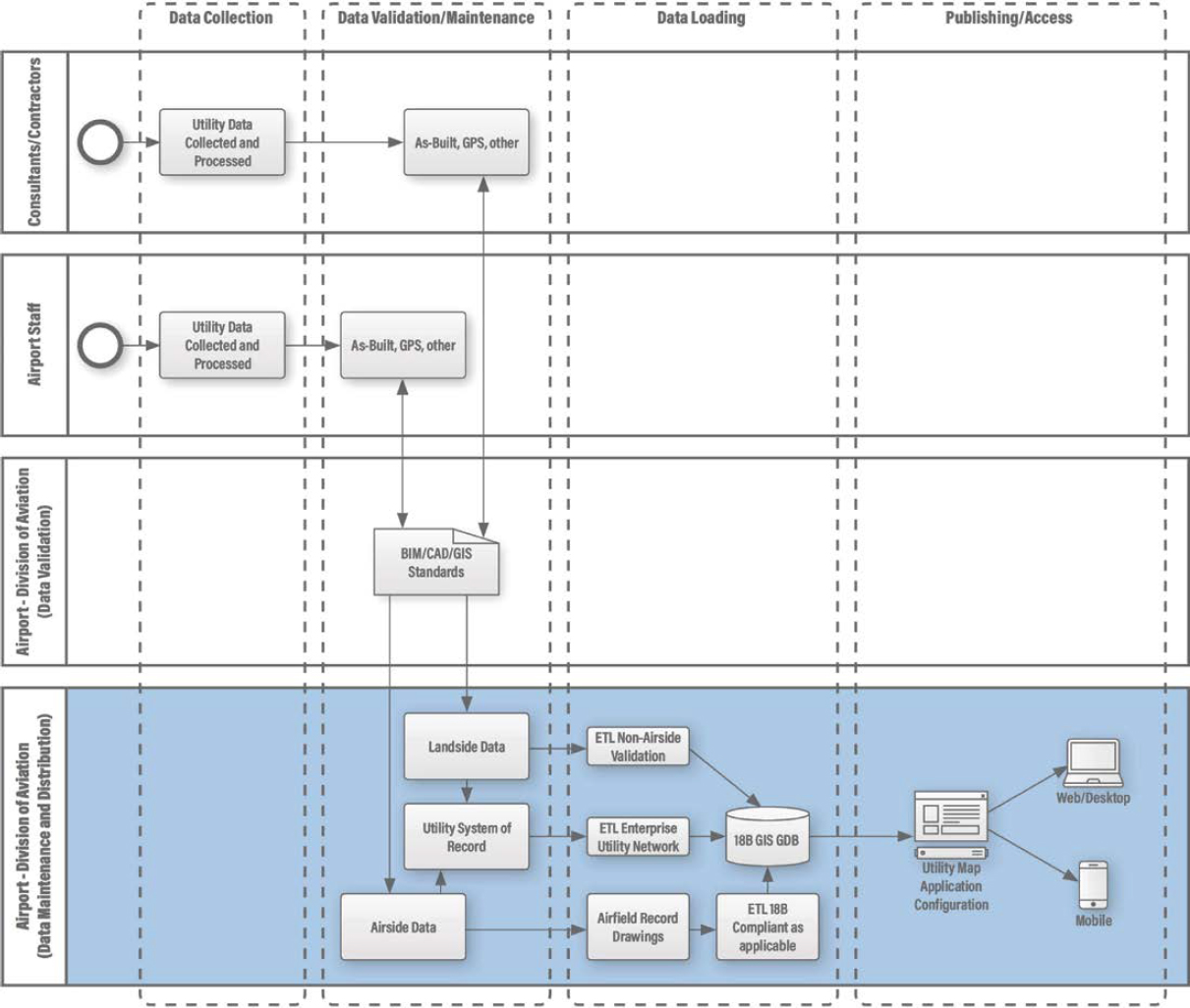

As illustrated in Figure 6-5, utility data that is collected and submitted by either a consultant, contractor, or airport staff member is first validated against the applicable data standard (i.e., GIS, CAD, BIM). If the input data fails the validation process, a report is generated identifying the errors required for resolution prior to resubmission. Data is then migrated into a corresponding landside or airside data repository that could be a series of record drawings or an enterprise utility network system of record data set. This is then processed using ETL procedures and loaded into an 18B GIS GDB that includes the 18B schema, as applicable. Like lease maps, these utility features would then be configured into business function applications and distributed to defined users via desktop, web, or mobile device.

6.5 Assets

Asset data not only indicates where assets can be found within the complex environment of an airport, but in most cases, it helps define the asset and its interrelationship with other assets that come together to form systems. Geospatial data is therefore critical to the success of asset management systems at airports.

An asset can come in many forms, including utility system components that have been previously described (i.e., manholes, inlets, hydrants, culverts, pipes, etc.). This section is focused on the collection and maintenance of single point-assets, including, but not limited to, signage, artwork, fire extinguishers, automated external defibrillators (AED), CCTV cameras, etc. Depending on the location of these assets, data collection can be performed using GPS for external objects, or an IPS for assets contained within building structures.

Data collection can be performed by a consultant or contractor via RFP, RFQ, or other procurement methods, or airport staff members using a variety of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) hardware and software. Data validation, loading, and publishing occur in a similar fashion to the utility workflow described previously. These types of asset features are structurally mounted and, in many cases, publicly visible, but characteristics of the asset can change due to damage, relocation, replacement, or in some cases, theft. For example, a CCTV camera will likely have the proper location and orientation within a camera system network but may need to be upgraded. If this is the case, the physical location would remain the same, but the attributes of the camera would change, such as installation date and manufacturer, fixed or rotating field of view, and the need for a rotation angle data field to accurately represent a fixed or variable field of view.

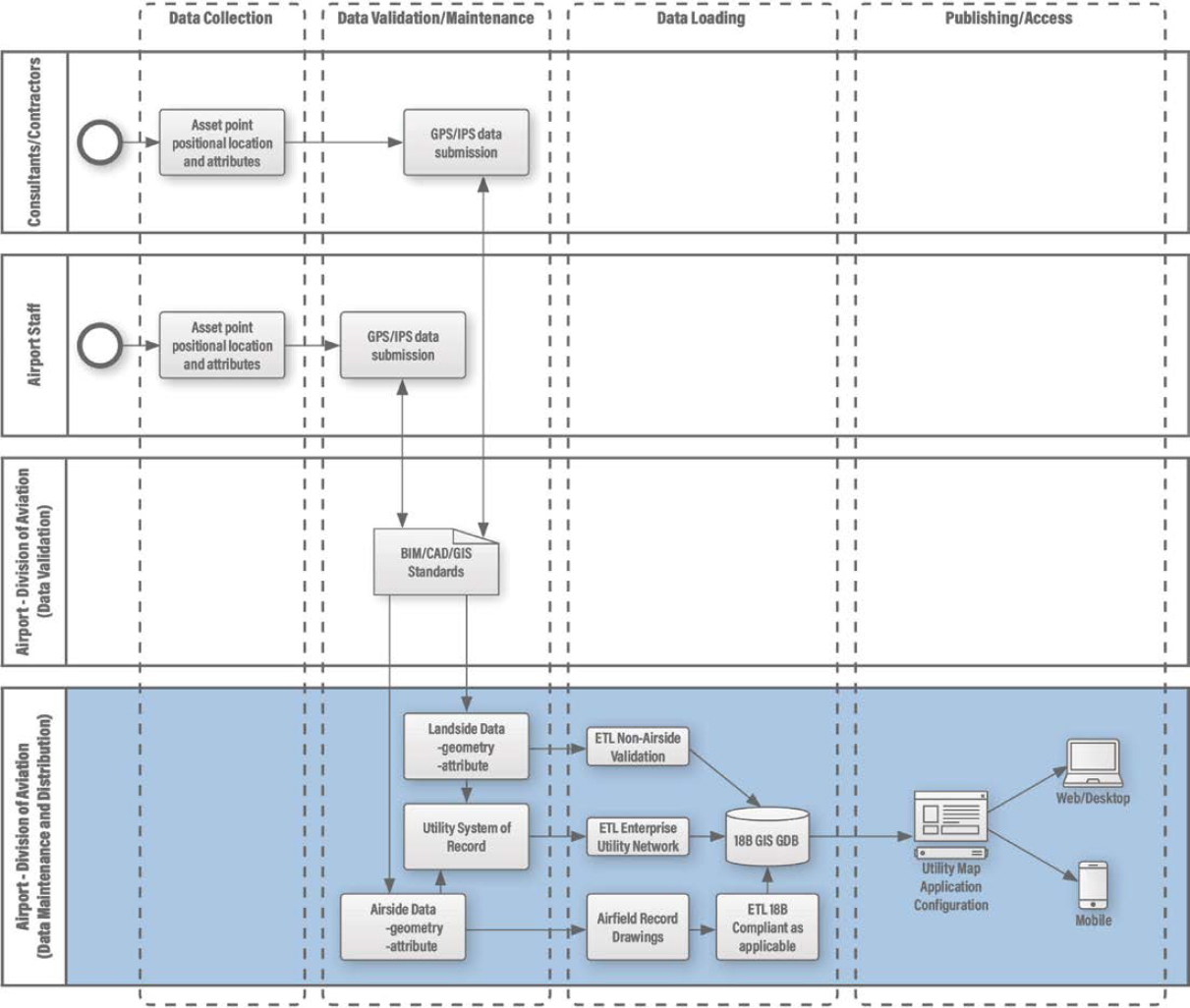

Figure 6-6 provides a high-level overview of these procedures. The following example workflow assumes that the collected asset features, whether through a formal procurement process

or inventoried by DOA staff, will not require 18B compliance (i.e., AED, artwork, signage, etc.). Point-based asset data collected via GPS or IPS will be processed through an ETL workbench to confirm alignment with the applicable GIS or CAD standard. If the input data fails the validation process, a report is generated and submitted to the consultant, contractor, or DOA staff identifying the errors required for resolution prior to resubmission. Once approved, this data is then run through an ETL to load the records into the 18B GIS GDB. Asset data can then be assembled into a user-defined application within a business application server and distributed to defined users via desktop, web, or mobile device.

6.6 Airspace

Any object that significantly protrudes vertically into the air may be an obstruction to flying aircraft. Through AC 150/5300-18B, the FAA has established a required methodology, Airport Airspace Analysis (AAA), to identify such obstructions to navigable airspace. AAA measures vertical objects against 3D, imaginary obstruction identification surfaces (OIS) to determine their level of vertical penetration of those surfaces. Penetrating objects may be considered actual obstacles.

The agency also developed ADIP, which is a web portal for project tracking and data submission for FAA-funded airport projects as one function. AC 150/5300-18B specifies an extensive set of airport-related data to be collected and submitted to ADIP, including a statement of work (SOW) and obstruction-related airspace data. Airspace data includes runway configuration, aircraft and approach types, and available navigational aids, which are integral to the definition of OIS. This data is considered safety-critical by the FAA, which necessitates that it be maintained and submitted to the FAA. The FAA is increasingly relying on airports to be vigilant about obstruction mitigation and requires airports to develop an Obstacle Action Plan (OAP) for mitigating identified obstructions. The process for conducting an AAA and preparing an OAP is described in Figure 6-7.

6.7 Summary

Although not all airports will carry out procedures identically, it was found that many of the procedures listed in this chapter are similarly executed at most airports. By illustrating a best-of-breed approach, but understanding that variations can be applied, procedural flowcharts will be one of the most immediately applicable results of this study.