Geospatial Data Governance Policies and Procedures: A Guide (2025)

Chapter: Appendix A: Case Studies

APPENDIX A

Case Studies

The following case studies were completed as a part of this research project:

- Asset Focus Drives Investment in Data at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport (AMS),

- Established Program Leads to Effective Practices at Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL),

- Data at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC),

- Growing GIS Group at Lexington Blue Grass Airport (LEX),

- Kansas City Aviation Department (KCAD) Data Governance Strategy at Kansas City International Airport (MCI),

- Effective Practices Have Evolved Over Time at Munich Airport (MUC),

- Standards Are in Place at North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT),

- Regulation Drives Focus on Long-Term Investment in Data Governance That Paid Off for the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT), and

- GIS Team Developed Procedures at San Francisco International Airport (SFO).

Asset Focus Drives Investment in Data at AMS

Organizational Highlights

Over 100 years old, AMS has become the third busiest airport in the world in terms of international passenger traffic. It is a complex airport with many diverse projects as well as unique and complex assets. AMS is striving to become the preferred airport for travelers, airlines, and logistics service providers in Europe and has prioritized customer satisfaction (ACI 2022). Providing information on aircraft gates and an intuitive wayfinding solution is one of the many ways AMS is working toward this goal. The airport recognizes, however, that all these measures require high-quality geospatial data.

The project team conducted an interview with Arisca Droog and Maya Tryfona, data engineers at Digital, Data, & Analytics/Team Information Management Services. There are layers to the organization, but they fall within Asset Management (which includes service managers, subject matter experts, reliability engineers, contract managers, business consultant information, and business consultant innovation). Another layer in Asset Management is Data Digital Analytics (DDA). DDA is relatively large, and includes the Geo Team, Electronic Data Management System (EDMS), Maximo Team, and Technical Information Coordinators.

Overview of Data Governance Program

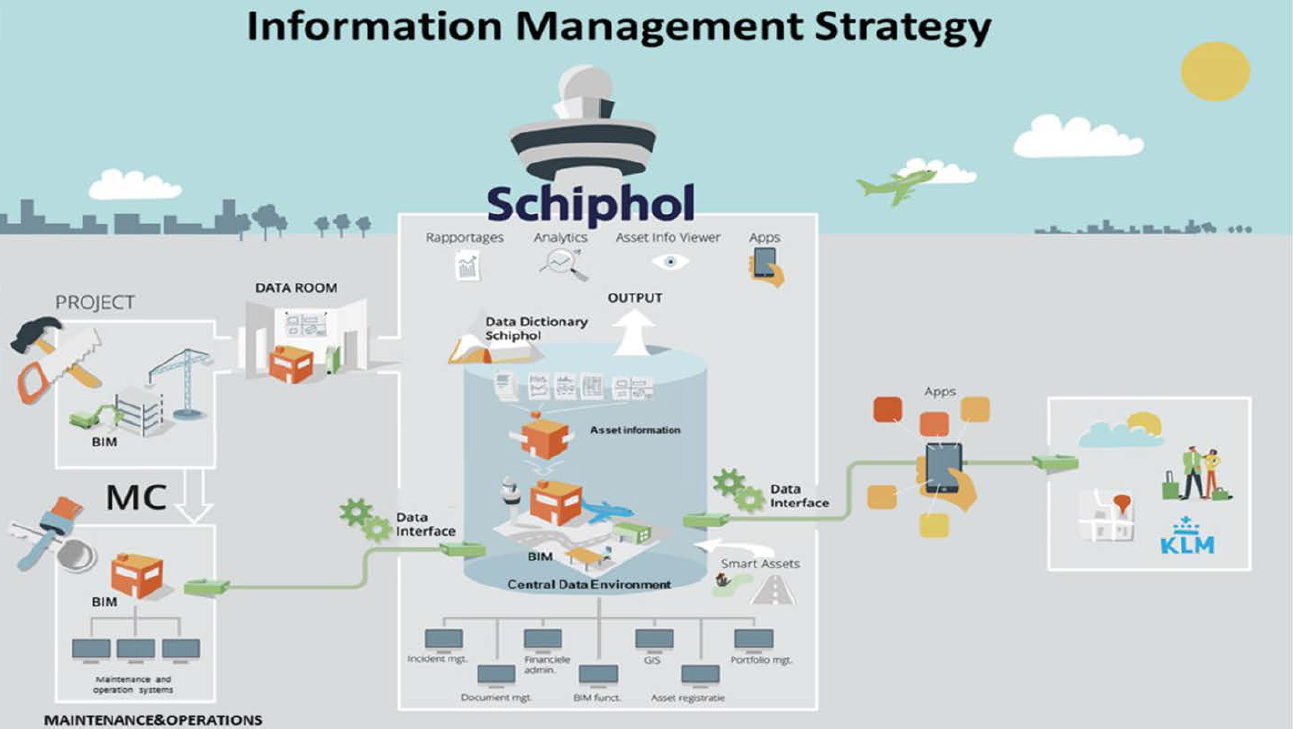

In 2017, AMS started designing a new information management strategy (Figure A-1), which became their way of working by April 2019. Droog stated, “instead of focusing on applications, we started focusing more on the objects, the assets, and the information needs and requirements

of the assets.” An information model was built to mirror the real-world configuration of the airport. This became the focus of their data-driven approach, which instilled the notion that information is an asset.

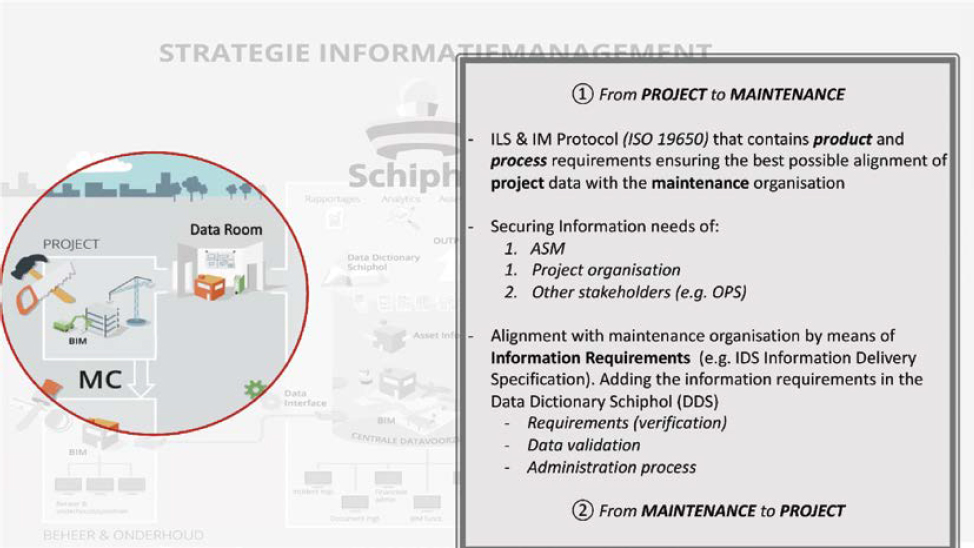

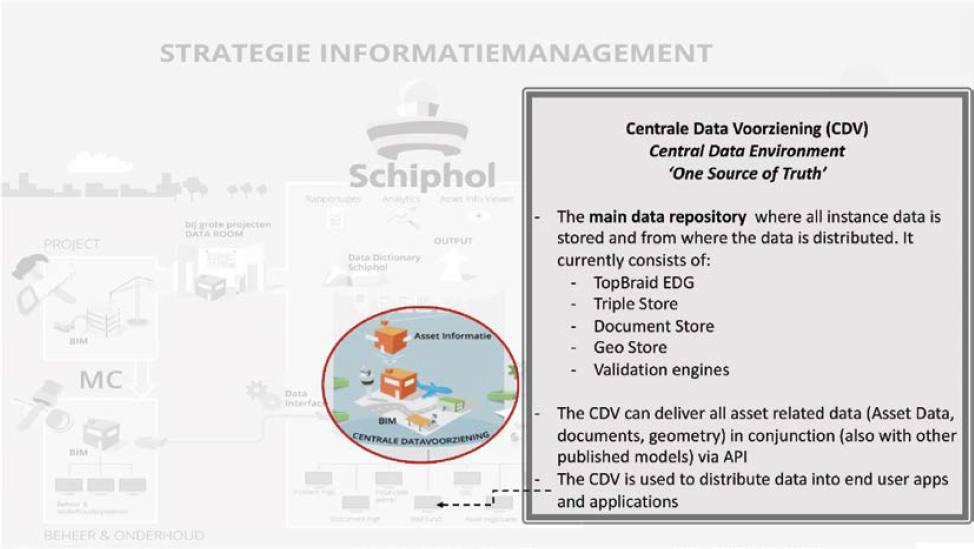

AMS’s data governance practices have evolved to focus on collecting data for maintainable assets. The goal is to get relevant data from airport design and construction projects into systems that can be used to maintain those new facilities as quickly and efficiently as possible (Figure A-2). The goal then became to reflect changes made by maintenance activities in the data to maintain the central data environment as the one source of truth (Figure A-3).

Regulations, Core Mission Objectives, and Policies

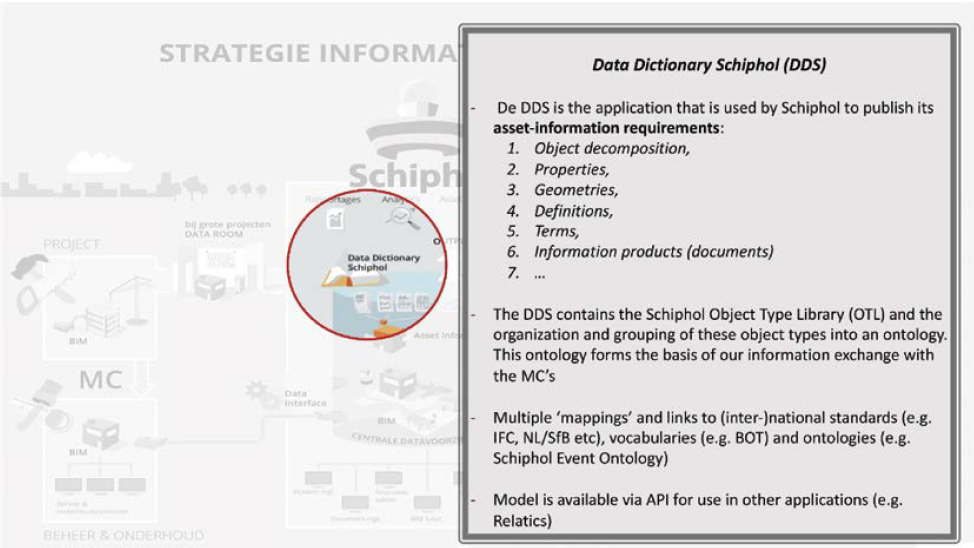

With a robust data dictionary, referred to as the Data Dictionary of Schiphol (DDS), data is validated before being stored in the central data environment (Figure A-4). The DDS is rigorously maintained and flexible to accommodate new assets. Alignment with national and international open standards helps AMS ensure that their data is as effective as it can be and future-proofed against requirements and technology changes. AMS does not force one software environment on contractors, rather they request that data is in the open international standard Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) while also receiving the original data. This ensures that contractors using different software platforms are not redrawing data, and the data is flexible and interchangeable, not subject to one vendor’s format.

Standards

The following primary standards have shaped AMS’s information management strategy:

- ISO 19650—Organization and Digitization of Information About Buildings and Civil Engineering Works, Including BIM, Information Management Using Building Information Modelling (ISO 2018);

- The building topology ontology (BOT), which describes the primary elements of a building and Resource Description Framework (RDF) for structuring metadata or information about

- the data itself, the RDF schema for describing links between related data elements, and the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative terminology (DCTERMS);

- National standards, such as NL-SfB, which is a standard for classifying elements, materials, and detailing in construction used in the Netherlands; and

- International standards, such as IFC.

Procedures

Contractors drive a lot of the data development, which makes things somewhat complex because there are main projects, maintenance, and larger projects (such as adding a terminal).

Balancing this is a challenge. When a request for change (RFC) is received, members of the data team evaluate the request and will set up a meeting with all collaborators involved (e.g., subject matter experts, contractors, designers). When the request is approved, it will then be modeled in the DDS, which will eventually lead to a new version that is made available to all parties involved.

Effective Practices

Some of the benefits and effective practices AMS realized as a part of their data governance program include the following:

- The shift of AMS’s focus on the assets instead of the systems, has improved data quality.

- There is a stark contrast from how all the different systems functioned previously—information was scattered, nothing was aligned, and there were duplicated efforts. Now, they are seeing data quality continue to improve.

- By following the RFC to new assets in the data dictionary and allowing data to be incorporated, specific errors from unique systems that are updated differently are eliminated.

Resources

With the world moving toward data-driven work, AMS started to fill the gap between projects and maintenance by requesting that collaborators think about the previous and next phase of a project. Everyone’s goal was to have complete, semantically rich data.

Conclusions

The following conclusions can be drawn from how AMS manages their geospatial data:

- A few key individuals recognized the value of data and proactively led what has effectively become a data governance program.

- A focus on assets and the data relevant to those assets has broken down organizational silos and led to the development of a centralized data resource that serves as the “single truth” for asset information.

- The availability of geospatial information has enabled solutions such as an augmented reality wayfinding application for passengers (Görtz and Smolders 2016).

- While not quite ready to call their system a digital twin, AMS is working toward this by maintaining a rigorous data dictionary.

Established Program Leads to Effective Practices at ATL

Organizational Highlights

At 4,700 acres with five runways, ATL boasts that it is the busiest airport in the world. Data governance at the airport has always been a need, but until recently, it has lacked a dedicated focus by the organization.

Overview of Data Governance Program

Historically, there has never been a formal organizational level data governance committee or responsible business unit at ATL. However, senior management is creating a new business unit in FY 2024 called Enterprise Information Management (EIM). This will establish an enterprise information integration and management group with the specific goal of integrating siloed and dispersed airport infrastructure and operational and business data across the organization into a managed and actionable resource tool.

The GIS Team, along with many other ATL business units, currently performs internal data governance practices; however, these practices are not documented nor coordinated outside the GIS business unit. Document Control is not responsible for data governance; they merely receive and archive documents and make them available through various online tools. The primary focus of Planning and Development (P&D) is on infrastructure and capital program execution. P&D is mostly concerned with project scope, budget, and schedule but lacks dedicated staff to enforce data standards upon delivery. Historically, data governance has not been viewed as a key component of any business unit or part of an individual staff’s job responsibilities.

In FY 2023, P&D created and began staffing an Asset Management Division, which will take on the role of facility and infrastructure data delivery and total cost of ownership of airport assets. This new business unit will greatly help with ATL’s overall need of data governance. The City of Atlanta Information Systems Department is also concerned with improving data governance from an IT perspective and has formed a data governance committee within its operations at the airport.

Regulations, Core Mission Objectives, and Policies

None provided.

Standards

P&D has CAD standards modeled after NCS; however, there is no enforcement of these standards at the project manager level. There is no contracting language to enforce true as-built data delivery.

ATL does not have any BIM data standards. Efforts to develop a BIM are currently underway and being led by the Asset Management Division. ATL does have a GIS schema for which many features are modeled after the FAA’s schema within AC 150/5300-18B (AAS-100 2014).

Procedures

One staff member in the P&D Engineering Division maintains CAD files with utility data. This data is shared with the GIS team. The Engineering Division maintains CAD representation, and the GIS Team maintains the GIS representation of this data.

Other than the GIS enterprise geodatabase, there is no central repository of authoritative data at ATL. As a result, project planning begins with data discovery from various sources, starting with the last airport staff member and the project manager, or the Document Control, Engineering, and GIS Teams.

As-builts of recently constructed data do not always get delivered with all relevant information. The GIS Team adds additional information such as source, relative quality, and accuracy of data to the data set it maintains. Data schema for utilities has fields where the GIS Team puts the source, relative quality, and accuracy of data, as well as the ASCE quality of data.

Data Security Policies and Countermeasures

The City of Atlanta’s Information Systems Department has specific security policies that are enforced from a technological perspective across ATL.

The City of Atlanta and P&D have standard SSI and propriety data contractual language with all RFP-awarded contracts. The GIS Team has a Spatial Data Agreement policy and procedure for geospatial data sharing outside the ATL organization.

Effective Practices

As stated, standard document control, information technology, and geospatial data agreements are in place, but more practices are needed as a formal data governance at an organizational level.

Resources

The airport lacks resources for as-built accuracy verification and enforcement, and no staff member or business unit is currently assigned to this task.

Conclusions

The following conclusions can be drawn from how ATL manages geospatial data:

- An important part of prioritizing data governance for airport sponsors could be accomplished by including compliance in a grant’s requirements.

- ATL needs a data governance champion at the highest levels of management for data governance to take root and become part of the organization’s culture.

- The past cannot be changed, but going forward, ATL can start small and expand their data governance program.

- To facilitate a mindset shift toward data governance, it is recommended that engineering, architectural, and construction management programs at colleges and universities incorporate data governance as a core part of the curriculum to train the future generation of professionals to develop an understanding of the importance of data governance.

Data at CCHMC

Organizational Highlights

CCHMC is one of the premier children’s hospitals in the world. The vision of CCHMC is to be the leader in improving child health. Established in 1883, CCHMC is now a full-service, nonprofit pediatric academic medical center that includes the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine’s Department of Pediatrics.

CCHMC has 16,000 employees and is comprised of 622 total registered beds, including 110 registered inpatient psychiatric beds and 30 residential psychiatric beds. Between 2020 and 2021, the hospital experienced 1.5 million patient encounters and 48,000 surgical hours.

The hospital was ranked fourth in the nation among all honor-roll hospitals in the U.S. News and World Report 2021–2022 Best Children’s Hospitals. Forbes Magazine named CCHMC among America’s Best Employers for Diversity, ranked the hospital second among employers in Ohio, and ranked CCHMC ninth, nationally, on the list of best employers for women. CCHMC also has received the Healthcare Equity Leader Award from the Human Rights Campaign for exceptional LGBTQ+ healthcare (Cincinnati Children’s 2024).

Overview of Data Governance Program

CCHMC puts high emphasis on data stewardship to oversee and govern data to ensure its quality and fitness for the enterprise’s data assets. Data and analytics are important facets of CCHMC’s mission to improve child health and provide fundamental support and information to the strategic plan. CCHMC’s data governance vision is to ensure healthy and trusted data that the organization can rely upon to improve patient outcomes, predict business performance, and provide insights across the enterprise.

The data governance operating model consists of data owners, data stewards, and program stewards. Data stewards are tasked with strategic oversight. Data stewards are charged with tactical execution and stewardship. Program stewards oversee tactical planning and program initiatives. Data and program stewards meet weekly to share updates on data elements and definitions. This group continues to grow as data governance expands to new areas of the hospital. Data owners meet monthly to review updates, provide guidance, and ensure alignment.

As part of data governance, enterprise data strategy goals were established to

- Eliminate data silos,

- Establish a clear source of truth, and

- Deploy data governance across the institution.

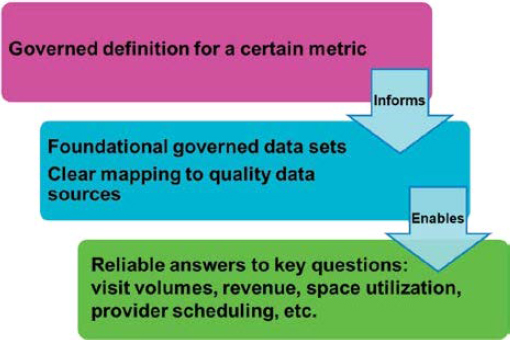

Through these goals, CCHMC increases the quality, trust, and reusability of the data to reduce redundant data sources, processes, cost, and data breach risk. Figure A-5 illustrates the data governance process outputs.

Regulations, Core Mission Objectives, and Policies

CCHMC produces an abundance of information about patients and their care. This data production is governed by strict regulations and standards such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). HIPAA is a federal law enacted in 1996 that required the creation of national standards to protect sensitive patient health information from being disclosed without a patient’s consent or knowledge.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) initiated five rules to enforce HIPAA:

- Privacy rule,

- Transactions and code sets rule,

- Security rule,

- Unique identifiers rule, and

- Enforcement rule.

CCHMC has many policies to safeguard patient data, including guidance on confidential information and limited data sets and deidentification of personal health information (PHI).

Standards

CCHMC’s Integrity and Compliance Program Manual details standards, policies, and procedures. The hospital has Information Services and Patient Privacy Compliance Programs to

oversee activities related to the privacy and security of confidential information, including protected health information housed in electronic systems. The programs’ activities are informed by applicable regulations and standards, which include but are not limited to HIPAA and the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) privacy and security rules, payment card industry data security standards (PCI DSS), the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA) and NIST standards, applicable hospital accreditation standards, applicable state laws and regulations, and CCHMC policies, manuals, and plans.

Procedures

The primary sources for data development and creation are a patient’s health records and hospital operational data. Another source is research data for medical devices.

Transparency is important in the data governance at CCHMC. Knowing about additional data sources and governed terms allows for more robust and consistent analytics while reducing rework. The operational data may include

- Regulatory compliance,

- Supply chain,

- Human resources,

- Billing data, and

- Contract negotiations data.

Data Security Policies and Countermeasures

CCHMC deals with highly sensitive data and follows HIPAA compliance. Therefore, data security is the top priority. Employees at CCHMC must be certified in a collaborative institutional training initiative (CITI) program. They are trained to properly deal with the data, for example, by knowing the difference between clinical and research data. There are policies in place to protect the confidentiality of clinical information. Staff cannot access this data unless it is related to a project that has been assigned to them.

Effective Practices

CCHMC has established best-in-class practices for data governance. However, like any organization, CCHMC confronts habits that do not support data governance. These include data silos or individuals creating their own definitions and interpretations, which causes problems and extra work to consolidate and validate. Another habit is trying to develop new processes, which leads to risk of exposure.

One thing that helped CCHMC in breaking data silos and explaining the metadata is developing look-up tables for data attribution. For example, by keeping track of material and stock in the supply room, staff members can make sure that there are supplies available for the patient within the closest stockroom when that patient moves rooms.

Resources

For data governance, the resources dealing with data and the analytics started small. There were pockets of knowledge across the organization that were heavily dependent on the background, experience, and recollections of individual staff members. As people retired, this knowledge was lost. Once the system started to be formalized and well structured, the processes and procedures took over and became institutionalized. This reduced the number of repetitive questions and

redundancy. Additionally, designated subject matter experts were identified to help in data consultation, such as safety data, financial, human resources, etc.

Conclusions

Data governance at CCHMC has been a multiyear journey to promote a cross-functional, organization-driven approach to data assets and their use. Policies and procedures continue to be developed for information ownership, data management, access rights, self-service, data quality, metadata management, authoritative data management, and enterprise-level business and operational definitions. As the program matures, CCHMC has moved from having to ask additional areas of the hospital to join the program to areas requesting to be included to benefit from having their data systems and process included in data governance.

Growing GIS Group at LEX

Organizational Highlights

In Lexington, Kentucky, LEX’s one-person GIS operation has recently started to expand to two people. While it is considered a medium-sized airport, they still think of themselves as small. They are structured into operations, engineering, maintenance, and support (IT and human resources).

Through communicating with similar airports, LEX stated, “we found out what not to do.” Their careful research, along with testing of software (AeroSimple for a 3-year contract), is proving to be worthwhile. Ultimately, GIS has been useful enough to the airport that they are adding a second GIS resource to the team.

Overview of Data Governance Program

GIS has made an impact at the airport. Although it may seem easy to regulate with only one person, that ease is soon to change when a second person joins the team, and the sources of data are plentiful. One of the keys to success has been the solid relationships built between airport staff members and contractors. The importance of good spatial data is recognized throughout the organization by prioritizing that all changes are incorporated (additional buildings, relocated fences, additional fire hydrants) before construction is complete. There even is a process of using design data and implementing as-built data into the LEX authoritative geodatabase.

Regulations, Core Mission Objectives, and Policies

There are few explicit policies, but the workflow established for utilities is strong. As-builts are required, and payment is withheld until final record drawings have been received and approved by the airport.

Standards

The Blue Grass Airport has authored a Project Record Drawings and GIS Deliverable Checklist that contains the following items:

- A general description of the checklist,

- Coordinate system and datum requirements,

- Development,

- FAA AGIS upload,

- Final Deliverables, and

- A thorough, itemized list of items requiring accuracy, photos, and sketches.

Procedures

LEX’s lone GIS staff member does a tremendous amount of fieldwork. He has developed a great relationship with contractors who understand the importance of redlining an as-built correctly. He also spends time in the field to ensure the drawings are correct. Preparation for field work includes having the drawings in hand and possibly overlaid on orthoimagery.

Data Security Policies and Countermeasures

Data is secured internally with the support of IT. While some data is in the cloud, it is also stored on premises as well.

Effective Practices

Maintaining solid relationships with teams working at the airport (contractors and internal staff) has been key to success. Knowing how to prepare good redlines while working in the field is an important skill in developing useful as-builts. Part of that has been due to the availability of viewers. LEX has a utility viewer and an Exhibit A Property Map Viewer to pull up parcels and review deeds. Recently, the operations staff started using AeroSimple. They are working on building GIS into AeroSimple and, surprisingly, the staff has used it more than initially expected.

Resources

To grow further, a second GIS team member is being added, which will mean the addition of a second ArcGIS license as well. IT is within more of a support group, and GIS is in Engineering, but GIS and Asset Management are being supported within the airport.

Conclusions

Communication between neighboring airports helps facilitate growth. LEX learned asset management through do-and-don’t advice from the neighboring Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport (CVG). In turn, CVG is learning utility data structures and processes from LEX.

KCAD Data Governance Strategy at MCI

Organizational Highlights

With a mission to provide outstanding airport services in a safe and cost-effective manner for the benefit of citizens, visitors, airlines, and customers, KCAD owns and operates MCI and Charles B. Wheeler Downtown Airport (MKC). KCAD is an enterprise fund department of the City of Kansas City, Missouri, and is supported by airport user charges. No general tax fund revenues are used for the administration, promotion, operation, or maintenance of the airports in the system.

Dedicated by Charles Lindbergh in 1927, MKC is the city’s first airport. Originally home to commercial aviation, the airport now attracts corporate, charter, and recreational aviation. In the shadows of the downtown skyline, up to 700 aircraft per day—everything from single-engine

propeller craft to sleek corporate jets—take off or land at the airport. The facility and its control tower are open 24 hours a day and consistently rank highly among private and corporate pilots for their full range of service to general aviation. Fixed-base operators service nearly 300 based aircraft, as well as itinerant and charter aircraft, offering fuel, full maintenance, aircraft rentals, sales, and flight training.

In 1972, MCI was built by the city and opened. The MCI complex spans more than 10,000 acres, and its three runways can accommodate up to 139 aircraft operations per hour. Three runways, two of them parallel with 6,575 feet of separation, Category III instrument landing system, and other features help keep operations smooth in even the worst of weather. In 2019, MCI served more than 11 million passengers.

Construction is currently underway on a new single terminal with 39 gates on the site of the former Terminal A. This project, which will fulfill a longstanding goal to consolidate the terminals into one, was completed in 2023. The terminal project is unique in that it includes requirements for digital BIM data deliverables, optimized for facilities management (FM) and COBie, to provide asset data that can be integrated easily into KCAD’s existing enterprise systems. The following divisions comprise KCAD: Accounting/Central Stores, Administration, Aircraft Rescue and Fire Fighting, Airport Police, Commercial Development, Downtown Airport, Environmental, Engineering, Facilities Maintenance, Custodial, Structural, Field Maintenance, Fleet Maintenance, Human Resources, IT, Marketing, Operations, and Parking.

Overview of Data Governance Program

The Asset-Related Data Governance Program at KCAD, while still relatively early in its evolution, has an ambitious, forward-thinking vision. Prior to the construction of the Maintenance Shop and Salt Storage Project in 2018, enterprise-level data governance was almost non-existent. Each of the key facilities-related departments (Engineering, FM, and Operations) had their own information systems with their own methods for managing asset data. Handoffs of information between departments was manual and occurred on an as-needed basis. However, as construction began on the Maintenance Shop and initial planning discussions for a new terminal project were underway, the leadership at KCAD recognized that this was a critical point for establishing better data governance. An overwhelming majority of the physical infrastructure owned by the organization was about to change and it was imperative that KCAD had a plan for ensuring that the necessary asset-related data was captured, utilized, and could be maintained in an effective manner.

The evolution of the first set of KCAD Data Standards, drafted and accepted during the Maintenance Shop and Salt Storage Project, was a turning point for KCAD in terms of data governance. First, as part of this project, KCAD established BIM as the enterprise standard for capital project design and construction. Specifically, the organization decided to adopt Autodesk Revit and related products as their standard virtual design and construction (VDC) authoring tools and make their file formats a required deliverable for all contractors. As a part of this project, KCAD also implemented and adopted Maximo as their enterprise asset management (EAM) system. These decisions allowed KCAD to move forward, knowing they were using industry-accepted, best-of-breed solutions for these critical business functions. They also provided a framework for creating complete and consistent data and deliverable standards. These requirements were meant to govern the creation, delivery, integration, and use of all digital asset data originating from capital projects.

KCAD has not made any organizational changes in relation to the new paradigm around asset data governance yet, save for the creation of positions related to in-house BIM oversight and management. However, the creation and adoption of these standards has resulted in a much more open, proactive, and robust relationship among Engineering, FM, Operations, and IT.

While data sharing and communication among these groups were done on an as-needed basis in the past, they now meet regularly to execute the steps of the adopted standards or discuss topics related to asset data governance that they know have impacts beyond their individual departments. One particularly interesting and noteworthy aspect of this observation is in IT’s role as a facilitator. The IT department has served as a catalyst for bringing the other groups together to discuss common goals, challenges, and solutions. The evolution of this role has a lot to do with IT’s visibility in the daily operations of each group, as well as the responsibility to manage the information infrastructure that supports each group.

In the coming years, with a set of data governance standards now in place, KCAD can expect to see a rapid evolution of their data governance program that leverages advancements in technology and the recently improved departmental relationships. Adoption of the standards provides a controlled and consistent process that can be measured to drive future improvement.

Regulations, Core Mission Objectives, and Policies

With the KCAD mission being tied to the provision of safe and cost-effective airport services, facilities themselves are one of the primary elements of public safety, and operating and maintaining physical facilities are one of the greatest costs. Optimization of the data, systems and processes related to the facility are key to KCAD’s ability to achieve its mission. Specifically, the data governance standards put in place look to support this mission by enabling the following capabilities:

- Single source of truth and general communication/collaboration,

- Virtual visualization of the facility,

- Coordination and scheduling of physical work,

- Operational and reliability analysis,

- Infrastructure coordination/clash detection,

- Job estimating (capital improvements and repairs),

- QA,

- Asset lifecycle management, and

- Safety (hazard mitigation and incident response).

Motivated by the progress of the new terminal project, the organization adopted a new way of managing the physical infrastructure by utilizing the latest technologies and emerging best practices. Now, discussions related to addressing the challenges the airport faces start with a dialog on the availability of automated and/or information-driven solutions instead of manual processes.

Another theme that influences the Data Governance Program is a need to reduce the reliance and risk of valuable information that is held only in one department or by one individual. As happened to many organizations, KCAD was not immune to the financial and human resource challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. With financial pressures on the city, many employees accepted buyouts resulting in the acceleration of the loss of experienced workers, which was already on an upward trend. KCAD needed to start establishing systems and processes that allowed for the turnover of staff without the loss of critical operational knowledge.

Standards

KCAD has mandated that all capital projects are required to follow their BIM Project Delivery Standard. This standard is made up of 12 individual standards or standard operating procedures (SOPs) that dictate how digital asset data will be created, reviewed, delivered, and integrated.

The following standards drive both the processes for digital asset data delivery and the relevant asset data standards:

- Project Roles and Responsibilities

- This document establishes the required roles (both internal and external) for all capital projects, specifically in relation to VDC coordination and digital asset data deliverables.

- The roles defined in this standard are referenced in all the following standards and SOPs.

- Project Execution Plan (PxP) Template

- Primary processes: project collaboration/communication, design submittals/reviews, spatial coordination, pre-submittal data management, BIM best practices

- Data standards: standard software/technical infrastructure, file naming, model content, model scope, asset parameters, level of development (LOD)

- Operations and Maintenance Document Management

- Primary processes: pre-submittal original equipment manufacturer (OEM) data management

- Data standards: Required OEM Documents, OEM Document Formats

- BIM Model Checker Requirements

- Primary processes: model and data QA/QC

- Data standards: Visual Checks (e.g., levels, coordinate systems, zones, etc.), Automated Checks (e.g., family naming, duplicate parameters, etc.)

- COBie Data Plan

- Primary processes: asset data capture

- Data standards: Asset Parameters by Project Phase

- Navisworks File Requirements

- Primary processes: geometry publishing

- Data standards: Model Content and Structure (Geometry)

- Import of COBie to Maximo

- Primary processes: asset data loading to EAM

- Data standards: COBie to Maximo Parameter Mapping

- Import of Navisworks to Maximo

- Primary processes: model geometry integration to EAM

- Data standards: Navisworks to Maximo Content Mapping

- BIM Commissioning

- Primary processes: field asset data collection and verification

- Data standards: N/A (utilizes BIM PxP and COBie Plan Standards)

- BIM for FM Model

- Primary processes: creation of FM-optimized BIM model

- Data standards: Model Content and Structure

- EAM Asset Lifecycle

- Primary processes: maintenance needs assessments (MNA), vendor contract procurement, preventive maintenance (PM) plan creation, asset spares management, maintenance planning and scheduling, commissioning, decommissioning, recommissioning, disposal

- Data standards: MNA Format, Vendor Contract Structures, PM Data, Asset Spares Data

- EAM Asset Structure

- Data Standards: Asset Data Structure, Systems Data Structure

It should be noted that these standards utilize or reference industry-wide standards as part of their definition. Specifically, Omniclass is utilized to classify facilities and organization roles and Uniformat 2010 is used as a base classification of systems and assets. KCAD has also adopted leading asset and system data structure and associated classifications for locations, systems, and assets.

Procedures

Digital Asset Data Delivery Process

Two views of the digital asset data delivery process are presented in this section. The first is a representation of the high-level execution plan of KCAD capital projects, as dictated by the Project Delivery Standard. It is meant to demonstrate how data governance activities align with standard capital project phases. The second is the actual flow of data through the systems utilized across the various phases of the capital project. Both are presented at a very high level, but they do provide the opportunity to identify the most glaring strengths and weakness of the processes.

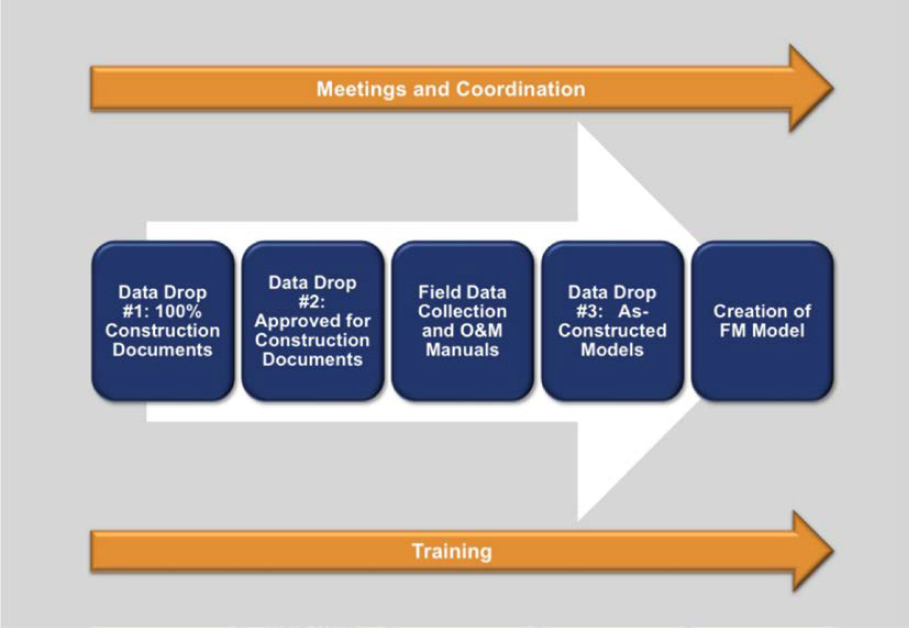

Digital Asset Data Deliverables—High-Level Execution Plan

Definitions of items depicted in Figure A-6 are as follows:

- Data drop—Submission by author to owner (reviewer) of phase-relevant digital asset data.

- 100% construction documents—The completed initial set of construction BIM models created from the design phase models.

- Approved for construction documents—The completed set of the owner-reviewed and approved construction BIM models prior to commencement of physical construction.

- As-constructed models—The completed set of construction submittals updated to reflect as-built conditions.

- FM model—A BIM model that has been optimized for Facilities Management, primarily by removing content that is not needed for operational purposes post-construction (e.g., markups, modeling elements/annotations, etc.).

At each data drop, the activities shown in Figure A-7 are performed as dictated by the Project Delivery Standard.

Data Security Policies and Countermeasures

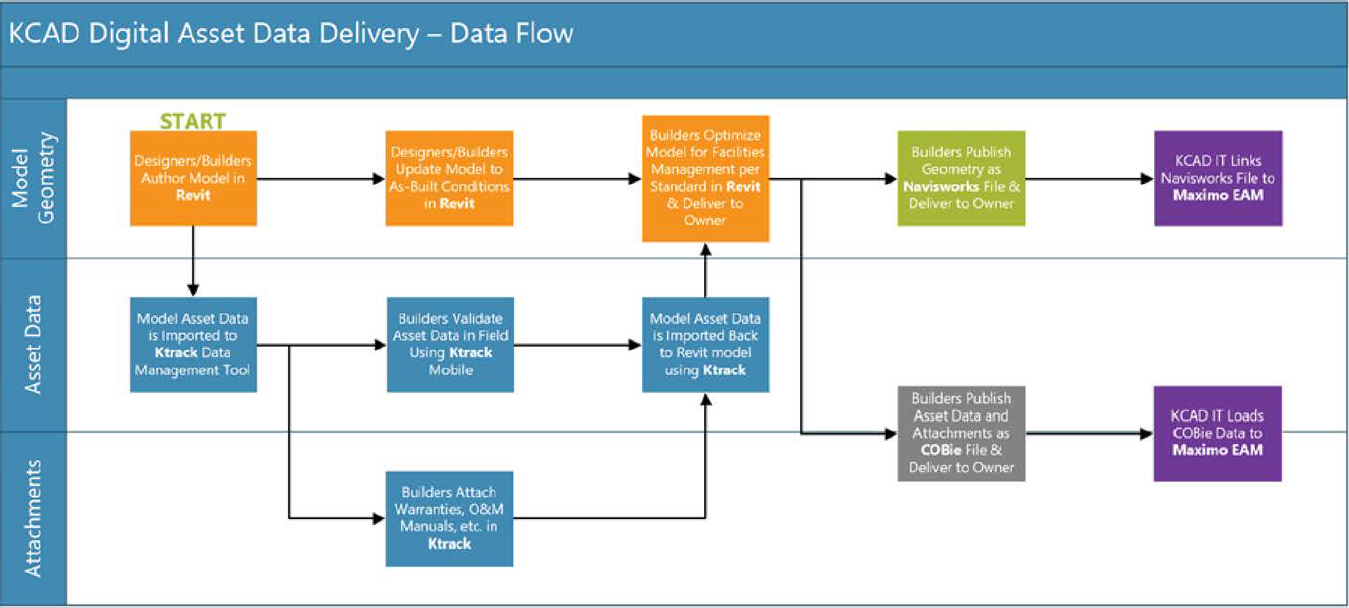

KCAD’s current IT security policies in place address system access, network firewalls, and traditional system security checks. These policies also include the data workflows that are dictated per their standard (Figure A-8). In KCAD’s current deliverable structure, data resides in Revit files (stored on network), KTrack (cloud), COBie files (stored on network), Forge (Autodesk cloud), and Maximo (Projetech cloud).

Effective Practices

Since the inception of the KCAD Data Governance Program, as marked by the initial adoption of the BIM Project Delivery Standards, the following practices have been found to be particularly effective:

- Establishment of main asset list—Among the most fundamental issues that continually comes up in the execution of the Project Delivery Standard is determining whether a particular element or component of the project should be considered an “asset.” To minimize these issues and address them as quickly as possible, KCAD established a main asset list that defined all the potential types of systems and assets that could exist in the facility that KCAD would consider an asset and, therefore, require adherence to the standards. In addition to making scoping decisions easier, developing a main asset list has forced users to evaluate the definition

- of an asset and conclusively define why they care about a particular type of asset. This has provided the context for defining what information is cared about in relation to that asset. It also is a great tool for connecting a Facilities and Asset Management Plan to capital project Digital Asset Deliverable Standards.

- Standardization of asset identification/naming—In addition to defining what are considered assets, KCAD learned that standardizing how assets are identified and named saves extensive time in downstream activities. Every hand-off across project phases, including the most critical hand-off from the contractor to the owner and integration with the owner’s existing systems, required the ability to quickly identify like or similar things. The ability to do this is dependent on consistent identification and naming standards, at least at the highest level.

- Adoption of software for in-project asset data management—The original plan for managing asset data and attached documents in the KCAD Project Delivery Standard was to use schedules inside of Revit and external Excel spreadsheets. It became noticeably clear, particularly for large projects like a new terminal, that the data entry capabilities of Revit would not effectively scale to handle all the required asset data collection. Also, managing external spreadsheets presented extensive linking and version control issues. In particular, the management of attachments (warranties, product data, O&M manuals, etc.) appeared to be an almost impossible administrative task. KCAD’s primary contractor on the new terminal project made the decision to use a software called “KTrack,” which easily synchronizes with Revit BIM models, to manage the asset data entry and review, including the management of attachments. KTrack and similar software packages are optimized for this purpose and provide a much more efficient and manageable means of working with these data sets and keeping them synchronized with model elements.

- Enablement of mobile technologies for field data verification—Among the most critical pieces of the asset data collection is the proper unique identification of an asset in the field and confirmation that the data contained within the model for the asset is accurate. Labeling of equipment, capturing of the unique ID, and verifying asset data (e.g., manufacturer, model, etc.) can only effectively take place in the field. As such, having the ability to access the model and its associate asset lists and data on a mobile device in the field significantly increases the efficiency of this activity and improves data quality. KCAD adopted a practice where they could easily identify and isolate an asset in the software while in the field. Field crews physically attach a label to the asset, and then use a quick response (QR) scanner to link the asset’s ID in the database while also viewing, confirming, or updating critical asset parameter values.

- Adoption of COBie Standard for asset data loading—One of the primary objectives of KCAD’s BIM Project Delivery Standard was to implement an automated way to import asset data from the contractor-provided as-built BIM models. Automating this process required the ability to define a consistent input so the process steps produced a consistent output. Adoption of the COBie standard provided this consistent input to develop and implement a data load process that could automatically consume the data from a BIM model. This created consistent asset and location data in the Maximo EAM System. With the COBie standard in place, KCAD can rest assured that as long as a contractor provides asset data using this standard, they will be able to upload that data to their Maximo System with a single click.

- Integration of Maximo with Navisworks—While the primary scope of KCAD’s BIM Project Delivery Standard was to ensure efficient, consistent, and complete asset data capture, a particularly valuable additional benefit is that they integrated the published Navisworks file (the 3D geometry) with their Maximo EAM System. Now, maintenance planners, craft supervisors, and maintenance technicians can navigate the 3D model of the facility directly in the Maximo EAM System and use it as a basis for identifying assets for work orders, providing markup snapshots for job tasks, and much more. KCAD has only just begun to tap into the value of having the geospatial context of the assets in the facility at their fingertips.

Areas for Improvement

Start data reviews and standards enforcement earlier in project—The current KCAD process places the first set of data standards audits at the 100% construction documents gate. By this point, the entire design model has been completed and reviewed and converted into construction models. At this point, families and types have already been used in the model that may or may not adhere to KCAD naming and ID standards. This means that in every case, there is a significant amount of work requested to update the data coming from the design model to conform. This issue can be avoided by making the design team adhere to the standards from the very start of the project and adding a data drop review within the design phase.

More robust common data environment for asset data management—While using a software package for “in-project” asset data management was listed as an effective practice, there is significant opportunity for even more improvement in this area of the process. The process is currently still dependent on the synchronizations of the KTrack database with iterative versions of the building models. Significant changes from version to version of the model can produce synchronization issues and challenges. If the data management software could be more tightly integrated (closer to real time) with the building models vs. periodically synched, many of these issues could be avoided or more easily managed.

More robust data standard for data integration (vs. COBie)—While utilizing a data standard for data coming out of the BIM model was critical for automating the load process to the EAM System, the COBie Standard is not particularly robust. One of the most critical weaknesses of the standard is its tie to a rigid hierarchical structure for facilities, floors, rooms, and assets while not having the ability to represent functional or systemic hierarchical relationships. The latter is often the basis for the structure of location/system records in EAM systems to provide functional context of the asset, not just location. A more robust data interchange standard should and could be developed by the owners, since they can define what source and destination systems will be utilized on their projects.

Investment in internal capabilities/roles related to BIM and EAM—KCAD had a noticeably clear motivation for establishing data governance standards on incoming capital projects. They were facing a project that was the build of an entirely new airport. However, shortly after the opening of the new terminal, their attention will need to turn to operation and maintenance of not only the facility, but the digital asset data that represents the facility. The data governance standards will continue to maintain accurate and complete data, but there will certainly be projects big enough to impact the digital asset data, but not big enough to completely contract. This means that KCAD will need in-house BIM, GIS, and EAM expertise and will have to continue to invest in this expertise.

Resources

The introduction of any type of organizational standard or program requires investing resources (both financial and human) to plan and implement. Instituting the BIM Project Delivery Standard and beginning an asset data governance program at KCAD is certainly no exception. However, KCAD identified opportunities on already funded projects to establish standards and processes that would provide immediate value to the efficient execution and benefits from those projects. For example, instead of developing the project delivery standard documents as a standalone, internal effort, KCAD included its drafting as a deliverable from their contractors on the Maintenance Shop and Salt Storage Project. While this was an additional incremental expense to the capital project, there were significant efficiencies gained from funding and executing it in this manner, such as providing immediate feedback related to its value.

Even with this method of implementation, internal resources needed to dedicate some time to spend in discovery workshops with the contractors as well as reviewing and providing feedback

on the submitted deliverables. Representatives from Engineering, FM, Operations, and IT all participated in these tasks as required. KCAD found that tasking contractors with the bulk of the work, with timely input and feedback from internal collaborators was the most efficient way to get the program off the ground. Ultimately, the standards, templates, and software created and implemented during the Maintenance Shop and Salt Storage Project became a fundamental component in the RFP and procurement process on the new terminal project.

KCAD realized early on that the upfront investment in developing and implementing standards avoid larger and longer expense when asset data is not captured and handed over as part of the initial project, regardless of cost to implement such standards. Organizations often spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to physically walk down, format, and load asset data into their various enterprise systems. Furthermore, if accurate asset data has not been collected and stored in a useful manner, technicians lose time hunting for this information any time they need to operate or work on an asset. This expense can compound itself repeatedly for the life of the asset.

It is suggested that any organization looking to implement similar standards plan to slightly increase the cost for capital projects and invest a small additional amount of time on their part. However, organizations can expect to more than make up for that expense in cost savings by having to avoiding future asset data walkdowns and lost productivity in operations and maintenance.

Existing Internal Roles with Increased Responsibility

Through KCAD’s review of staffing, the facilities manager, information technology manager, and operations manager roles are positions that already exist in most organizations but should expect an increased amount of involvement on capital projects with a geospatial data governance program in place. This increased involvement includes participation in planning meetings to define/refine applicable standards for specific projects and perform or oversee data reviews during the project’s “data drops.” These roles certainly can choose to delegate these responsibilities to a member of their team but should not abdicate their team’s key role in the process.

New Roles to Consider (if Not Already Existing)

BIM manager, GIS manager, and asset data manager are suggested for the following reasons:

- BIM manager—As BIM is likely to become the predominant means for bringing asset data into the organization, it is imperative that airports have an individual with enough knowledge and experience to manage and oversee the creation and update of BIM models throughout the life cycle of the facility, including operation.

- GIS manager—Airports encompass a significant amount of non-building-based assets, most notably, the airfield and related systems. Similar to BIM, GIS will become a technology that is increasingly relied upon to support operations and maintenance. It is critical that airports have an individual with enough knowledge and experience to manage and oversee the creation and update GIS data and services.

- Asset data manager—With an ever-increasing reliance on data to support the integration of data sources like BIM, GIS, and EAM, airports that have a role dedicated to the strategic planning and management of asset-related data will find that they can get much more value out of emerging technologies like the Internet of Things (IoT), augmented and virtual reality (AR/VR), artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and digital twins.

Conclusions

The following conclusions can be drawn from how KCAD manages their geospatial data:

Effective Practices Have Evolved Over Time at MUC

Organizational Highlights

The Data Management and GIS Team at MUC includes 34 people and consists of three teams: CAD (building side), GIS (surveying side), and systems development and archive.

Overview of Data Governance Program

Data silos are a known issue with different departments using different tools and data in the GIS environment. MUC wants to form a governance group with 10 to 15 collaborators; however, this has not yet come to fruition. The GIS team is the driver for data governance and is pushing upper management to make data governance a priority.

Regulations, Core Mission Objectives, and Policies

None provided.

Standards

At MUC, CAD standards are in place that include CAD layer list, list of assets, and AutoCAD blocks. The standards focus on as-built and asset data.

The GIS team has set up BIM standards and an information delivery manual; however, these standards have not been included in the contract language until now.

Procedures

CAD (Building Side): All floor plan data is maintained in AutoCAD. Room information is also stored in the Oracle database. Emphasis is placed on facility management data and asset data. Typically, an asset is stored as a block stored in an AutoCAD drawing. It contains a unique ID that acts as a connection to all attributes (serial number, date installed, manufacturer, etc.) and is stored in the Oracle database.

GIS (Surveying Side): Data outside the buildings (topography and underground utilities) is collected by surveying. The data is also stored in the Oracle database.

MUC created a system called VISMAN (Visualization Management) that makes it very easy for users to extract and maintain data in AutoCAD and Oracle. A web-based version is used by more than 1,000 users.

Other departments that work with GIS systems maintain their data in their systems. Utility data is maintained regularly by the surveying team using as-built information and field surveys.

MUC has a mobile lidar scanner that is being used to scan a new terminal building for cross referencing with BIM data and clash detection.

Airlines and other tenants are contractually obligated to provide data regarding any changes they make to leased space to MUC.

The GIS Team maintains data in their own data schema in Oracle and uses FME workbenches for data translation and extraction to provide airport data quality data to requestors.

Data Security Policies and Countermeasures

It is MUC’s aim that as many people use GIS for their daily work as possible. Part of the GIS data can be accessed by any user who has an account at the airport. Data that is relevant for security or contains confidential information is controlled, and access is provided on a need-only basis. Certain data is only made available to certain departments.

Effective Practices

Data owners maintain their own data. For example, base data like topography, utilities, and floor plans are maintained by the Facility Management group. Other data (like heating and ventilation, electrical, plumbing, environmental, etc.) are maintained by individual departments. Facilities Management has provided a platform, VISMAN, to help departments maintain their data. VISMAN is a web-based system that allows users to change both geometry and attribute data. Most of the data maintained in VISMAN is point objects. Most of the data is stored in MUC’s Oracle database, and individual departments determine what data is uploaded to this database. To maintain the accuracy of utility data, MUC surveys all utilities being installed at the airport.

Resources

The geospatial team consists of 34 staff members.

Conclusions

The following conclusions can be drawn from how MUC manages their geospatial data:

- Incorporating standards into contract language is extremely important for contractor compliance and ensuring data quality.

- Metadata should be included as part of data standards.

- Upper management support and buy-in is extremely important for the success of data governance.

- Eliminating silos and consolidating data into an authoritative centralized repository removes data duplication and errors.

- Data owners need to be the people who know the data best, not the GIS group.

Standards Are in Place at NCDOT

Organizational Highlights

NCDOT works with North Carolina Geographic Information Coordinating Council, a part of the North Carolina Department of Information Technology (NCDIT) for their data standards.

NCDOT has 25 of the 329 data sets in NC OneMap. To give an idea of the impact of aviation in the state, there are 72 airports in North Carolina, and 10 of them are commercial services. Each airport is managed individually.

The interview was with members of the NCDIT-Transportation GIS Unit, and the interviewed parties were Eric Wilson, GIS Unit Manager for NCDOT; Jun Wu, Application Services Group; Sarah B. Wray, Spatial Data Manager of the GIS Unit; and Erin A. Lesh, Spatial Data Operations Group (Highway Focus).

Overview of Data Governance Program

The GIS Unit maintains spatial data standards and provides guidance on data content standards, metadata writing, and recommendations for content standardization. The GIS Unit does not have any authority to hold anyone to these standards and spends a significant amount of time on data translation and integration work due to a lack of data standards compliance. There is an aviation roadmap RFP that is pending due to budgetary issues.

Regulations, Core Mission Objectives, and Policies

NCDOT does not currently have a data governance officer or a data governance committee. There are varying levels of interest at different levels within the agency; however, it is not a priority at this time. There has been a push from NCDIT–Transportation for data governance on the business side, but these efforts have not yielded results to date.

Standards

NCDOT Division of Highways maintains detailed CAD standards; however, it is not certain if the Division of Aviation maintains independent CAD standards. Each airport is managed independently and has their own consultants who perform CAD work on the airport’s behalf. Deliverables are maintained at each airport and managed by the consultants. The exact airport to central reporting methods and structure within the Division of Aviation is unknown to the GIS Unit currently.

There are no BIM standards, but the NCDOT Division of Highways and NCDIT–Transportation are looking at a digital submission process. There is no discussion regarding digital twins currently.

NCDOT Division of Highways utilizes contracting language to ensure adherence to design standards. Any firm working on NCDOT Division of Highways projects receives an NCDOT CAD workspace that is standardized, and this standardization helps keep new data compliant with the approved standards.

True as-builts are required for NCDOT Division of Highways projects, but most consultants and contractors do not provide them. There is no contractual incentive for them to do so, and there is no means to enforce this part of the contract language when it is included. If as-builts are provided, they are provided as marked-up drawings or scanned PDFs.

Data quality across NCDOT varies significantly from business line to business line as well as data set to data set. Data maintained by NCDIT-Transportation on behalf of NCDOT is accurate to the data’s stated purpose as much as possible. Through cursory observation by the GIS Unit, consumers of NCDOT GIS data do not prioritize their focus on data quality while consuming data and tend to assume the data is suited to a particular use case based upon subject matter alone. Not verifying the specific data is suitable for a specific purpose presents a significant risk

when making decisions based upon unverified data. GIS data is not held to surveying standards. It is planning level information based on orthophotos, engineering plans, or other sources.

Procedures

New GIS centerline data is added to the repository maintained by the GIS Unit when the roadway is open to traffic. This includes new features and updates to existing features. Any as-builts that support updates are not validated by field survey.

NCDIT–Transportation has tried to define certain standards and continues to encourage data modifications with the aim of standardization across business lines. Currently, there is no comprehensive repository of data that addresses the needs of all business lines. Attribute naming nomenclature is well defined for asset inventory data maintained within the Agile Assets product but not for most of the other assets. This lack of standardization has resulted in NCDIT–Transportation engaging each business line or industry partners directly to ensure that mapping of assets is performed in alignment with expectations and industry standards.

Metadata is manually validated. A new agreement between the GIS Unit and NCDOT is now in place regarding publication standards. If someone is going to use an ArcGIS Online license, they must also publish metadata associated with their data for agency visualization. However, there is no NCDOT policy to enforce the agreement and/or the results of auditing data completeness. NCDOT does have a GIS trainer on staff, but at this time, metadata training is not being actively pursued by NCDOT business units.

Data Security Policies and Countermeasures

There is no NCDOT agency-wide defined policy on what GIS data can and cannot be shared. Sharing is managed at the NCDOT business unit level. For example, NCDOT does not share financial, archaeologic, or threatened/endangered species data, but almost all other data is publicly available.

Effective Practices

While implementation is still in progress, NCDOT’s metadata procedures are progressive. Also, their work toward educating users on the capabilities of the GIS Unit will further the progress of both programs.

Resources

Although the GIS Unit responds to map and data requests, most data requests are already available via existing published services. Therefore, some requests become educational for the requestor as to which published asset data best fits their needs. Business units are actively being trained to enable units to produce their own products and services when resources are available, but the GIS Unit works with business units if the resources are not available.

Conclusions

The following conclusions can be drawn from how NCDOT manages their geospatial data:

- There is a lot of data duplication within the agency (outside of data managed by NCDIT–Transportation). Each division can collect its own data for the same asset without data governance oversight.

- There is a lot of value in standardization; however, since different divisions (roadways, airports, etc.) have different funding sources, it has been difficult to get the divisions to standardize data.

- For data governance to be successful, it needs an executive-level champion. Issues like those discussed here need executive-level decisions and mandates.

Regulation Drives Focus on Long-Term Investment in Data Governance That Paid Off for the ODOT

Organizational Highlights

ODOT is responsible for 176 public-use aviation facilities, eight commercial airports, two public-use seaplane landing areas, and 633 private airports and heliports in addition to more than 43,000 miles of highway. ODOT divides the state into 12 districts that work in conjunction with Central Office divisions. Assistant directors head the divisions that are then subdivided into offices.

Overview of Data Governance Program

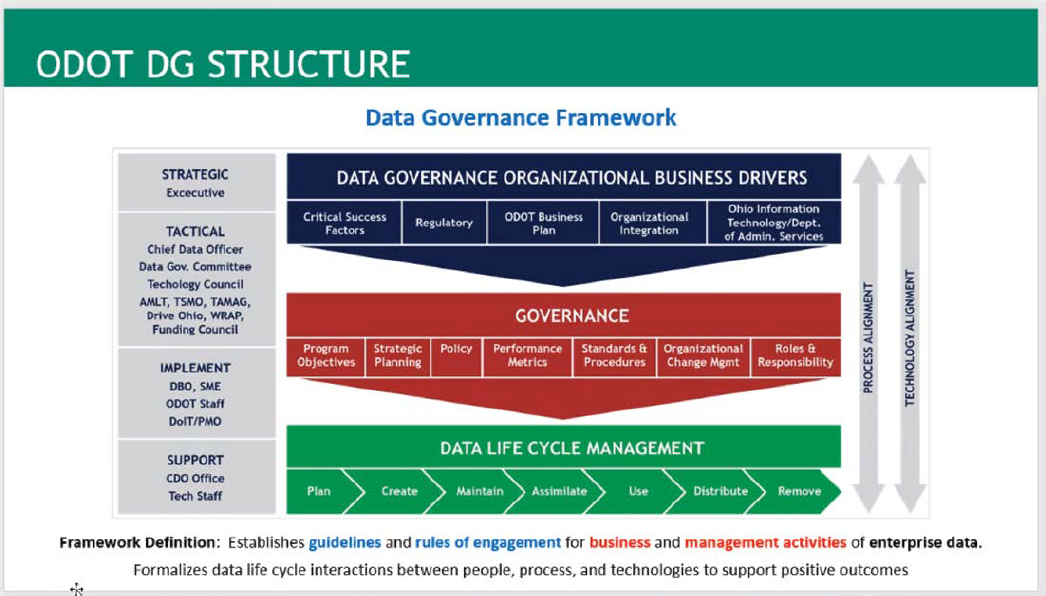

The Data Governance Office is in the Division of Planning and reports to the assistant director of transportation policy/chief engineer. Asset and data owners are known as “data business owners.” Data is not maintained within the Data Governance Office, but rather solutions are created, and processes are identified for the data business owners.

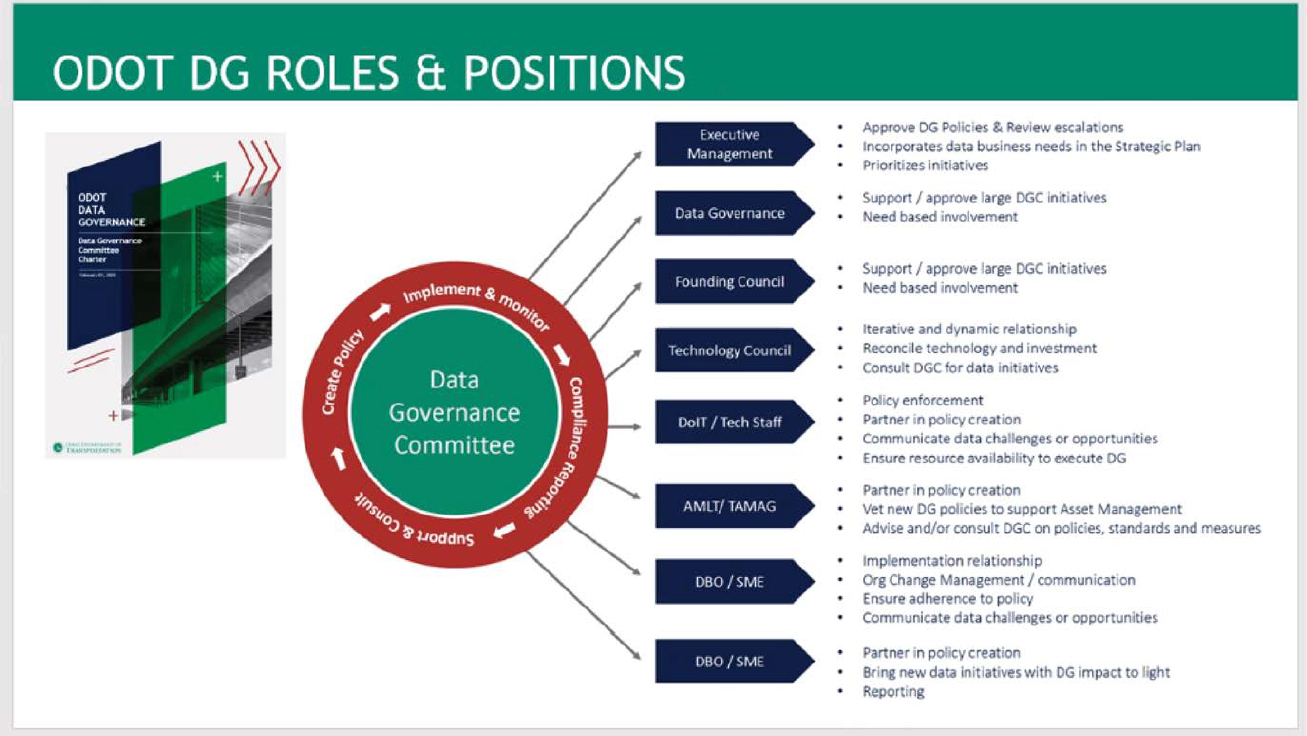

The office has executive management that provides the authority for the Data Governance Office to act. A steering committee, which contains people from different sections of the agency, exists but has not met recently due to a lack of practical things to discuss currently. There is also a technology council whose mission is to try to reduce duplicative technology within the ODOT technology footprint. Then, there are the technology staff and subject matter experts (SMEs).

Regulations, Core Mission Objectives, and Policies

The data governance program at ODOT is largely prompted due to the recognition of data being a valuable asset for helping ODOT deliver a more efficient asset management program. ODOT has taken a step further to establish data governance as a core value for internal purposes as well.

Because the Data Governance Office is not solely producing data, they have taken a holistic approach and evaluate the life cycle of the data by creating dashboards to track the progress of inventory, inspection, and collection. This dashboard provides an alternative to iPad collector applications (commonly called apps) that can make things easier to manipulate and easier for mid-level managers to track progress.

Standards

A data dictionary was developed by ODOT for its geospatial data that includes information related to the function the asset serves, data needed to support linear referencing, and metadata. KPIs have been established for data related to critical assets (e.g., a KPI target is to ensure 95% of all district assets have critical data in the database). Once a data cataloging tool is fully implemented, similar KPIs will be implemented for as many asset types as possible.

Procedures

Time was taken to define what exactly data governance was within ODOT because even among Data Governance Office team members, there were misconceptions. The definition they

settled on is that data governance “establishes guidelines and rules of engagement for business and management activities of enterprise data. Formalizes data life cycle interactions between people, process, and technologies to support positive outcomes.”

Data governance procedures are actively being developed.

Data Security Policies and Countermeasures

Although only briefly discussed, privacy, retention, and security are addressed in the data life cycle management phase of the Data Governance Framework (Figure A-9 and Figure A-10). Ian Kinder is the data privacy officer for the agency and applies the Ohio Revised Code across more than just assets and geospatial data. He addresses human resources, financial systems, and process audits for confidential personal information. They are also in the process of developing a policy for data privacy.

Effective Practices

ODOT is focused on assets and the data required to operate and maintain those assets. Assets have been divided into two tiers: those that are critical to transportation and those that are not. This helps prioritize resources, determine when solutions are developed, and resolve any conflicting priorities. This prioritization needs to remain flexible, however, to adjust to needs as they arise.

There is a form that users and business owners can use to submit requests for changes to the structure of their asset-related data. The requests go through several stages of review and prioritization based on level of effort and the type of change. Changes are currently done annually, but a process to tackle easier requests is being discussed because only three to four major enhancements are done per year.

Although not every data business plan is reviewed each year, a risk-based cycle is in place to evaluate the asset’s need for review. Questions about how dynamic or sensitive the information is help rank the asset’s priority, and therefore, any proposed data changes.

Business requirements detail everything from the type of service (app, web app, or dashboard) to the fields, schemas, domains, and even how the data is accessed in different sections of ODOT. These user manuals are critical to data quality and ensuring consistency along with easier training.

Resources

Resources were not specifically discussed.

Conclusions

The following conclusions can be drawn from how ODOT manages their geospatial data:

GIS Team Developed Procedures at SFO

Organizational Highlights

SFO’s GIS Team currently consists of three people and is responsible for maintaining all GIS data compiled from various sources. The GIS group falls within a larger Infrastructure Information Management Team that provides geospatial and asset management support to the airport at large.

Overview of Data Governance Program

There is no formal organizational-level data governance committee or a geospatial data governance committee at SFO. There is an informal team of three individuals that constitutes the GIS group, which has defined data governance–related standards and processes to help keep track of the growing amounts of data they maintain for various departments. To help track source data that is received, along with requests for data from internal and external collaborators, they have created a web-based ticketing system. Tickets are divided into two categories: GIS Data Requests and GIS Data System. All incoming requests are logged, issued a ticket number, assigned a service-level time, periodized, and tagged for future fetch-and-search operations. Reports generated from the ticketing system are used for apprising submitters of the submittal status with estimated times of arrival (ETAs) for setting service-level expectations.

Currently, SFO has a grassroots-oriented approach to geospatial data governance that is designed to support the business users’ needs for geospatial data. In the future, they would like to establish a geospatial data working group. Led by the GIS Team, the group would include SMEs from Operations, Maintenance, Leasing, Marketing, and Police and Fire. SFO intends to start the SFO Academy on GIS, which would train airport staff on GIS applications and uses of GIS.

Regulations, Core Mission Objectives, and Policies

A key goal of the airport is to maintain a high level of passenger satisfaction, as well as to support airline, cargo, and other tenants’ needs. This has resulted in a desire to keep data sets depicting terminal spaces, signage, and wayfinding data up to date. The GIS group has worked closely with colleagues in the commercial and facilities departments to support their need for geospatial data in terminal and parking areas that serve passengers.

Standards

SFO has CAD, GIS, and BIM standards in place. These data standards were developed in close coordination with one another and with all the various collaborators involved in creating, maintaining, or using geospatial data. The management within design and construction also prioritizes collaborator engagement in the development of standards, procedures, and policies. This objective has ultimately led to increased compliance with the standards. The result is higher quality data and improved data interoperability between various phases of the facility life cycle, from planning and design through construction, to operations and maintenance.

The data maintained by the GIS Team is not purported as design level, architectural grade, or survey grade by the team. It is promoted as reference-grade data. Data is divided into four data quality types named Tiers 1–4 as follows:

- Tier 1: Data is manufactured and maintained by the GIS Team.

- Tier 2: Data is maintained with assistance from SMEs and/or collaborators.

- Tier 3: Data is created and maintained exclusively by the collaborator(s).

- Tier 4: Data includes AC 150/5300-18B data and planning-level data from ALPs. Archives hold construction-level data. This data is never modified or altered from its original format.

FME is being used heavily for automated checks on data, such as QA/QC data (geometric check with attributes tying into CAD and BIM standards), topology check, and 32-character UniqueID for every feature in the database (i.e., GeospatialID).

Procedures

SFO currently does not use a database document management system, and data is stored in a corresponding file structure on the network drive. Data is channeled into three domains: exterior data, including airfield data and AC 150/5300-18B data; interior data, and underground utilities data, each overseen by one expert. Not all data is added to these data models. As with any large organization, the GIS Team has a close working relationship with some departments, but other departments are not as involved.

Data Security Policies and Countermeasures

All data is behind a virtual private network (VPN) because some data may be considered as SSI. Some users need triple authentication to access data. In the future, SFO may explore tokenization services and capitalize on how the data is being used and with whom it is being shared. SFO requires authentication and completion of a digital data release agreement and nondisclosure agreement (NDA) prior to release of data to any external parties. These agreements are issued and tracked through the GAT (GIS Agreement Tracker).

Effective Practices

Over the past 2 years, the GIS Team has managed to get valuable feedback from collaborators. The more information a collaborator provides, the more they can see gaps in their data in relation

to other systems. This prompts them to fill those gaps and improve their data quality. Engaging departments on a regular basis (by participating in monthly meetings with collaborators) has proven extremely useful in understanding upcoming needs, as well as understanding the bigger picture of what is going on at the airport.

The GIS Team has built relationships with departments, and they work on a focus of small wins like map production or simple GIS applications to get the word out about GIS. The more people see it, use it, the more they know and value it and develop an interest in improving data quality to suit their own needs.

Integrating software that airport staff in different departments use into GIS is very important. It is also imperative to get GIS requirements incorporated into RFP/RFQ stages for all projects.

Determine what models you need. At SFO, topology, domains, table schema are all housed in the three data models: an exterior data model (EDM), interior data model (IDM), and utility data model (UDM).

Resources

It is very hard to quantify ROI. For example, GIS data maintenance cost on a maintenance contract can be quantified. To do this, track staff hours needed to find data without GIS and convert that to ROI dollars.

Conclusions

The following conclusions can be drawn from how SFO manages their geospatial data:

- It is important to have GIS champions (spend time here but don’t try to convert everybody).

- Have relationship development with departmental collaborators.

- Focus on small wins to highlight the importance of GIS. Small wins can often turn into big wins.

- Start small and scale up.

- Focus on integrating with systems that are vital to the daily operations of the airport (e.g., NextGen 911 emergency response, security monitoring, facilities, maintenance, Part 139 inspection and reporting, billing, and space planning systems).

- Incorporate GIS requirements in the RFP/RFQ for each project, contractually obligating consultants/contractors to provide data and adhere to standards.

- It is important to include SMEs from various disciplines/departments into the Geospatial Working Group.

- Produce good data and make it easily available to individuals and easy to integrate with information systems that need it. Most new systems that airports are purchasing come with a map or geospatial component of some type, it should be mandatory. These systems integrate with GIS and the geospatial data it contains. New systems should not be recreating geospatial data that already exists in the GIS, it is not cost-effective and may not pass audit.