Community Voices and Scientific Insight Build a More Resilient Cedar Key

Program News

By Maeghan Klinker

Last update November 3, 2025

A Community on the Front Lines of Change

Located on the western coast of Florida below the panhandle, Cedar Key is a low-lying barrier island with a population of approximately 800 full-time residents. That number has been dwindling as the area experiences increasing flooding as rising seas, strong storm surge, and recent hurricanes have caused extensive damage to shorelines and the community.

The reality of living with hurricanes is painted starkly across the town. Storefronts bear spraypainted boards marking the businesses they once housed or pointing would-be patrons to new locations. Signage on the main street marks the historic highwater lines for storms that have hit the island. The highest of these was Hurricane Helene in 2024 with a maximum storm surge of eight to twelve feet, high enough to inundate most of the island. Media reports indicate that about 25 percent of the homes in Cedar Key were destroyed during Helene, along with numerous businesses. While the scars of recent hurricanes remain visible, Cedar Key residents are working toward a more resilient future.

Designing Nature-Based Solutions

Dr. Savanna Barry and her team at the University of Florida are partnering with the Cedar Key community to design nature-based solutions to address flooding risks and mitigate climate-related hazards through a project funded by the Gulf Research Program (GRP). Nature-based solutions use and restore natural and modified ecosystems to help communities manage flooding and other hazards, benefiting both people and nature.

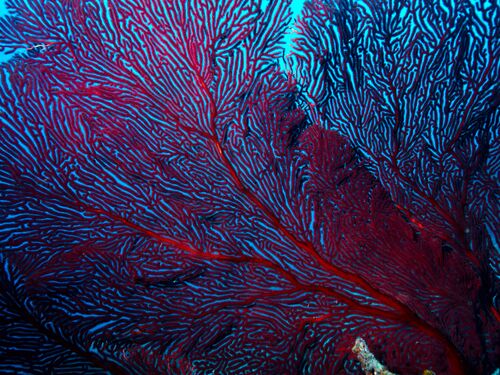

For coastal communities, that often looks like living shorelines. Instead of building concrete seawalls, living shorelines use natural materials—such as plants, rocks, and oyster shells—to stabilize the coast. These natural materials provide additional environmental benefits such as creating habitat for fish and wildlife, filtering runoff, reducing erosion, and storing carbon.

Community Collaboration in Action

Previous collaborations between the community and the University of Florida focused on living shorelines and sparked the city’s interest in further applications of nature-based solutions to protect vulnerable public infrastructure threatened by sea level rise, frequent storms, and chronic erosion.

Dr. Barry’s project focused on an area that encompasses critical routes for emergency services, a popular shore fishing spot, a public school, private homes, local businesses, and failing stormwater infrastructure. For former mayor Sue Colson, the project represents a tangible way to protect her community. “The first time I got value out of this project was from the very first workshop,” said Sue Colson, who stepped down as mayor of Cedar Key in April 2025. “For me, it’s all about implementation.”

From the start, the project aimed to create designs tailored to Cedar Key, shaped by input from its residents. In the initial phase of the project, Barry and her team held a series of stakeholder-driven workshops and surveys, conducted site visits to inform design possibilities, and integrated technical expertise with local preferences, infrastructure needs, and equity considerations.

After six months of iteration and incorporating community feedback, the planning phase resulted in community-vetted conceptual designs for a hybrid living shoreline – a design that combines natural features like oyster reefs with engineered elements such as rain gardens, sea groins, and permeable pavements.

At each step of the project, community input influenced aspects of the designs, such as placement, type, and aesthetic of different nature-based solutions. For example, Barry noted, community input guided species choice for native plantings, resulted in incorporating recreational access to a sea groin including the number and type of paths, and redirecting the shoreline design away from a version that included living breakwaters and pivoting to create template designs as resources to support private property owners manage flooding in the wake of Hurricanes Idalia and Helene.

Community feedback also provided valuable insight into questions and challenges that would need to be addressed to ensure the project’s long-term success, such as accounting for parking availability, maintenance, and costs. These discussions ensured the designs reflected how residents actually use and value their waterfront.

“Even though community co-design of nature-based solutions might take more time, it nearly always results in a better final product that has a better chance of being built and cared for by the community,” said Barry.

The Future of Cedar Key

The project is already producing benefits for Cedar Key. Based on discussions during the projects very first workshop, city staff investigated the option of installing check valves, an approach for regulating the in-flow and out-flow of water, for their most vulnerable stormwater outfalls. When a significant precipitation event occurred just one month later, causing flash flooding in several areas around Cedar Key and inland Levy County, the two sites with new valves drained the water away. Additionally, street areas that used to flood with saltwater at very high tides have not been inundated by saltwater since the installation despite several high-tide events. For the city of Cedar Key, this early success demonstrated the value of working with the University of Florida team to implement science-backed solutions.

Looking ahead, nature-based solutions can ease the impacts of climate hazards but rising seas and the increasing frequency and severity of storms will continue to affect life in Cedar Key.

“The reality for Cedar Key and many other small coastal communities is that they will need to adapt many things to be able to live with the effects of climate change,” said Barry. “I see nature-based solutions as part of the solution among broader efforts that City leadership are undertaking, including raising homes and roads and relocating critical infrastructure to higher ground. Nature-based solutions cannot save Cedar Key alone, but they can go a long way to prolonging access to some of the City's most loved rituals, like sunsets at G Street.”

As Cedar Key works to implement solutions that can preserve their community in the face of climate change, Barry and her team hope that their project can serve as a case study for other researchers to co-design solutions with communities. While the designs coming out of the project have met with support from the community, Cedar Key still requires funding to make those designs a reality and Sue Colson isn’t the only one thinking about implementation.

“The design phase of the ShOREs project is coming to a successful end,” Barry noted, “but the true measure of success will be the actions that come next.”

More like this

Discover

Events

Right Now & Next Up

Stay in the loop with can’t-miss sessions, live events, and activities happening over the next two days.

NAS Building Guided Tours Available!

Participate in a one-hour guided tour of the historic National Academy of Sciences building, highlighting its distinctive architecture, renowned artwork, and the intersection of art, science, and culture.