Genesis: The Scientific Quest for Life's Origin (2005)

Chapter: 17 The Pre-RNA World

17

The Pre-RNA World

I’ve been waiting all my life for an idea like this.

Simon Nicholas Platts, 2004

What preceded the RNA World? We understand a lot about the possible earliest stages of life’s emergence—how to make the prebiotic soup with all sorts of interesting molecules and how to assemble those molecules into a variety of larger useful structures. At the other end of the story, we have a good handle on how strands of RNA might function as evolving, self-replicating systems (as we’ll see in the next chapter). But there’s that maddening gap between the primordial soup and the RNA World. Stanley Miller sums up the problem: “Identifying the first genetic material will provide the key to understanding the origin of life. RNA is an unlikely candidate.”

To be sure, there have been numerous creative attempts to close this gap. Several researchers have approached the problem by proposing simpler types of precursor genetic polymers that might have arisen before RNA. In a tour de force research program, the Swiss chemist Albert Eschenmoser explored the stabilities of more than a dozen variants of RNA with modified sugar-phosphate backbones. He systematically replaced the 5-carbon sugar ribose with various other 4-, 5- and 6-carbon sugars and discovered seven new kinds of stable nucleic-acid-like structures. Most significant was the discovery by Eschenmoser and colleagues of a nucleic acid with the 4-carbon sugar threose (the molecule was dubbed TNA). Unlike ribose, which must be synthesized through a rather cumbersome sequence of chemical steps, threose can be assembled directly from a pair of 2-carbon molecules. This difference makes TNA a much more likely molecule than RNA to arise spontaneously from the prebiotic soup.

Other scientists took a different chemical tack. In 1991, the Danish chemist Peter Nielsen and colleagues synthesized a novel genetic molecule—a “peptide nucleic acid” (PNA), which features RNA-like bases bound to a backbone of amino acid molecules. The reliance on readily available amino acids, rather than problematic sugar phosphates for the polymer backbone, appealed to many members of the origins community. The discovery of PNA also underscored the chemical richness of plausible genetic molecules.

These immensely creative efforts expand the repertoire of prebiotic possibilities. They also hold the promise of providing new kinds of synthetic genetic molecules that can interact with modern cells yet not interfere with cellular function—a potential boon to medical research. Nevertheless, no one has managed to achieve a plausible prebiotic synthesis of these alternative nucleotides, much less a viable genetic polymer. The door is wide open for new ideas.

THE PAH WORLD

***WARNING: The following section presents an intriguing hypothesis, but one that is highly speculative and as yet untested. Such novel ideas fuel origins research, though most are eventually cast aside—the victims of faulty chemical reasoning or failed experimental predictions. Whatever the outcome, this story epitomizes the exhilarating process of scientific exploration.***

In May of 2004, Simon Nicholas (“Nick”) Platts was in trouble. After almost five years of fruitless graduate work, and approaching his fortieth birthday, he was about to be deported to his native Australia with no degree and no job. [Plate 6]

Nick’s life had defied the traditional arrow-straight science career path that most of us knew: college, graduate school, postdoc, and tenure track. A gifted chemist and enthusiastic educator, he went from a master’s degree in chemistry to teaching at Melbourne Grammar School. Only at the advanced age of 35 did he resolve to return to university, get a doctorate, and do some research. Life’s chemical origin was one topic that really excited him, so he applied to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, to work with Jim Ferris.

His new RPI colleagues found Nick to be outgoing and supportive, always ready to help others with their research, and eager to teach un-

dergraduate chemistry, but progress on his thesis project suffered. After three years in Troy, he moved to Washington, D.C., and the Carnegie Institution as a NASA-sponsored predoctoral fellow, a position that would allow him to acquire his doctorate from RPI, but do the research in a new setting with fewer distractions. He had two years left to complete a thesis.

Nick was full of ideas. Early in 2003, he came to me with plans for an elegant experiment on the possible influence of Earth’s magnetic field on the origin of biological homochirality. Could I provide some lab space?

“OK, but for how long?” I asked. My lab is small and space is at a premium.

“Once it’s set up, the experiment should take only a couple of weeks,” he assured me, so I offered him the necessary space for a few months.

“No worries!” his Aussie reply.

Nick started with a flurry of activity, marking out a good fraction of my lab bench with masking tape, cordoning off a sink that might otherwise splash onto the lab’s delicate apparatus, assembling an elaborate optical table, and filling cabinets with hardware, but his progress soon slowed. Crucial supplies were on back order, funds were needed for a special laser, other difficulties followed. More than a year later, the sequestered lab space, still piled high with equipment, was gathering dust. When pressed about his plans, Nick was vague and evasive. Many of us feared that he would be forced to leave the Geophysical Lab empty-handed at the end of June 2004. A sense of shared responsibility weighed heavily on George Cody, Marilyn Fogel, and me.

EUREKA!

Nick Platts’ life changed dramatically for the better on Tuesday, May 25, 2004. That’s when the central idea for his PAH World scenario crystallized. Max Bernstein, a colleague of Lou Allamandola at NASA Ames, had planted the seeds for the concept at an RPI seminar in November 2001. Bernstein’s talk had emphasized the occurrence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in deep space, and it got Nick thinking about PAH chemistry. A September 2003 conference in Trieste in celebration of the 50th anniversary of Stanley Miller’s breakthrough experiment in-

spired more progress. “On the return flight,” Nick remembers, “I scribbled the idea on the back of a United Airlines ticket.”

The germ of an idea gradually developed “on the mental back burner,” but May 25th was the Eureka moment. “It was 5:51 p.m.,” Nick recalls. “That’s when I did the drawings. That’s when I realized how big this was.” Contrary to popular myth, there aren’t many such moments in science.

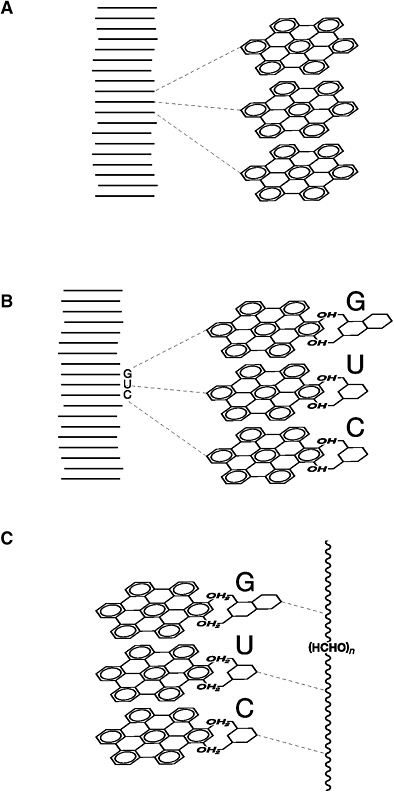

Nick’s new idea follows in the tradition of other models of pre-RNA genetic polymers, but with an original chemical twist. PAHs would have been abundant among the plethora of prebiotic molecules. (We met them back in Chapters 3 and 5 as significant components of carbonaceous meteorites and, by extension, the cosmic debris that formed our planet.) Each of these flat sturdy molecules consists of fused 6-member rings of carbon atoms with hydrogen atoms around the edge. PAHs are relatively insoluble in ocean water, but under the influence of solar ultraviolet radiation they can be chemically modified, or “functionalized”; hydrogen atoms can be stripped off, and new molecular fragments can take their place. If the PAH edges become decorated with OH, for example, then their solubility in ocean water increases significantly.

By any calculation, PAHs and their functionalized variants were a significant repository for organic carbon on the primitive Earth. I suspect that some origins chemists thought it a shame to lock up so many potentially useful carbon atoms in the relatively inert, biologically useless PAHs.

But what if PAHs played a key role in the ancient ocean? What Nick realized was that a functionalized PAH with OH around the edges is an amphiphile—a molecule that both loves and hates water, similar to Dave Deamer’s lipids (see Chapter 11). The flat surfaces of the carbon rings repel water (they’re hydrophobic), but the OH-bearing edges of the PAHs attract water (they’re hydrophilic). So what happens when lots of functionalized PAHs are placed in seawater? How might the hydrophobic parts stay away from water, while the hydrophilic parts remain in contact with the wet surroundings? The simple answer is to assemble a pile of PAHs like a stack of plates in the cupboard. The flat hydrophobic parts shield each other from water, while the edges form the water-bathed outside of the stack. The PAHs self-organize.

Platts predicted that, once stacked, the system would preferentially bind small flat molecules, like the DNA bases, to the PAH edges and

thus concentrate them from the surrounding prebiotic soup. These baselike molecules would attach and break free in a constant game of molecular musical chairs. Gradually, however, a selection process would take place. Because the PAHs are loosely stacked, adjacent flat PAH molecules would slide back and forth and rotate next to each other, like your hands do when you rub them together on a cold day. This mechanical action would tend to break off any edge-bound molecule that isn’t, itself, as flat as a PAH. Consequently, the small, flat, ring-shaped base molecules (the A, C, G, and U of RNA, for example) would bind preferentially around the edges of the stack. What’s more, these RNA bases are also amphiphilic, so they might have a tendency to line up more or less on top of each other, forming a kind of ministack. Remarkably, the spacing between the PAH layers (and hence the vertical separation between bases) is 0.34 billionths of a meter—exactly the same spacing as found between the bases of DNA and RNA.

The result of all this self-organization, according to Nick’s PAH World hypothesis, would be a stack of PAHs decorated along the side by an array of small flat molecules, including bases—an arrangement that looks for all the world like the information-rich genetic sequence of DNA or RNA.

Once bases are effectively stacked, Platts suspects, other small molecules would start to form a backbone linking the bases together into a true information-rich molecule, though those key chemical steps remain fuzzy. Then a change in the ocean water’s acidity, as might be experienced by moving from a deep hydrothermal environment to a more shallow zone, might allow the sequence of bases to break free as a true pre-RNA genetic molecule that could fold back on itself to match up base pairs. Eventually, complex assemblies of these polymers might act as catalysts for self-replication and growth.

Nick’s proposal lacked any experimental support. Nevertheless, the PAH World hypothesis seemed to provide a geochemically plausible, self-consistent, conceptually simple, and seamless chemical path from the dilute soup to an RNA-like genetic sequence.

SHARING

Nick Platts’ model crystallized in a flash, but was it reasonable? Did it make sense? He decided the best strategy was to bounce the idea off other people.

(A) Nick Platts’ PAH World hypothesis rests on the ability of polycyclic molecules to self-organize into stacks. (B) Once stacked, the PAHs would tend to attract small flat molecules (notably the bases of DNA and RNA) to the edges. (C) A molecular backbone forms to link the bases into a long chain. (D) The RNA-like chain of bases separates from the PAHs and folds into a molecule that carries information. (E) Complex assemblages of these chains have the potential to catalyze reactions. These drawings are adapted from Nick Platts’ unpublished manuscript.

I must have been about tenth on his list. Nick appeared at my office door on the afternoon of Thursday, May 27th. “You got a few minutes?” he asked, taking a seat. I nodded, hoping for a progress report on the stalled thesis experiments. “I’ve found something extraordinary,” he began. “I think I’ve discovered how life began.”

And so he described his hypothesis—the self-assembly of functionalized PAHs, the selection of flat molecules along the edges, the fortuitous spacing of the bases. He sat on the edge of his chair, leaning toward me and gesticulating as he spoke. Nick was clearly exhausted from almost two days without sleep; his voice took on a manic intensity. “This is a once-in-a-lifetime moment! I’ve never been part of anything this big!”

I was a bit taken aback by what sounded like a wildly speculative idea. It seemed at first like another distraction, just weeks before his scheduled doctoral defense.

“I told Dave Deamer and he loves the idea.” Nick rattled off the names of half a dozen other origin-of-life experts he’d already contacted. “No one can think of an objection.” Then, paradoxically, “We’ve got to keep this secret. Someone else will be sure to steal the idea, so don’t tell anyone.”

“Can you propose any experimental tests?” I asked him. A safe, neutral question, while I considered how else to respond.

He deflected the question. “There’s lots we can do, but we have to get this out fast. I’ve been drafting a manuscript. I’d like you to be a coauthor. Where do you think we should submit it?”

A manuscript? Coauthorship? Nick had just raised the stakes. I was uncomfortable with being an author unless I could contribute something original to the paper, but I was happy to discuss publication strategy. I thought the ideal forum for a short, high-impact outline would be a 700-word “Brief Communication” in Nature or a similarly concise “Brevia” in Science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences was another option, but PNAS articles are generally longer, and Nick had no data yet with which to flesh out his hypothesis. He agreed to adopt the short Nature format, while I promised to read his paper and comment quickly.

The next day, Nick e-mailed me a 700-word draft for “Edge-derivatised and stacked polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) as essential scaffolding at the origin of life.” I could tell from the title that

the paper was going to need some work. Even so, as I read the text I warmed to the elegant theory.

The hallmark of any useful scientific hypothesis is that it makes unambiguous predictions. Nick’s hypothesis made testable predictions by the bundle. First, functionalized PAHs must self-assemble into stacks. The stacked PAHs, furthermore, must be of similar size and shape. PAH edges must attract a variety of molecules, but there must be a preferential selection for flat, baselike molecules. And the bases must also be aligned vertically. If only we could confirm at least one of these predictions.

George Cody provided the chemical evidence that made me a believer. Coal, George’s specialty, is loaded with PAHs. It turns out that there’s already an extensive scientific literature on the ability of functionalized PAHs to self-organize into stacks—a process known as discotic organization. A quarter-century of publications had already elaborated on Nick Platts’ prediction. Neither Nick nor I had ever heard the word “discotic” until Cody mentioned it, drawing on seminars he’d heard on the subject while working at Exxon. I returned to Nick’s manuscript with a red pen and renewed intensity. My principal contribution was to come up with a catchier title, “The PAH World.”

By Tuesday, June 1st, Nick had received comments from more than a dozen scientists from around the world and the draft manuscript was taking final form. He called a meeting of Carnegie coauthors—nine of us in all—at the Lab’s library. We sat around a massive mission oak table and worked through the paper one last time. Should we talk about the common mineral graphite, which also has flat carbon rings? Had we included the most appropriate references? Should we propose specific experiments? Our biggest concern was Nick’s figure, which needed to make the essentials of the model as clear as possible, and he agreed to redo it. He submitted the PAH World paper to Nature on Thursday, June 3rd, just nine days after his epiphany.

OPINIONS

Nick had no time to relax. Whether or not Nature accepted the paper, he wanted us to stake a claim. We began e-mailing the manuscript, designated “in review,” to a dozen astrobiologists and origins experts to request their comments. We focused on leading RNA World propo-

nents—Jerry Joyce, Leslie Orgel, Jack Szostak—figuring they would have the most to gain from the novel idea.

Responses came quickly and with varying degrees of enthusiasm. A few scientists who were good friends of the Lab were warmly congratulatory, but most respondents remained cautious, and almost everyone cited the need for experimental evidence. Jack Szostak responded in less than an hour with some skepticism, adding “I think it’s worth pursuing experimentally—it would certainly be cool if an effect could be demonstrated.” The next day Leslie Orgel chimed in, “An experimental demonstration of your scheme might be interesting, but I wouldn’t advise publishing without showing that it works well.”

“I thought it was interesting and certainly appealing,” echoed Jerry Joyce. “However, it would help tremendously if there were some experimental support.”

Andy Knoll joined the chorus: “For now it is fascinating speculation, but the ideas seem amenable to what you guys do best—careful experimentation.”

Evidently the editors at Nature agreed. We received the form rejection letter a week later. “Thank you for submitting your contribution, … which we are unable to consider for publication.” Boilerplate didn’t make their decision any easier to swallow. “Because of severe space constraints … we are unable to return individual explanations to authors….”

EXPERIMENTS

Experimental evidence seemed the obvious key to securing support for the PAH World hypothesis. Unfortunately, experiments take time, and that was one commodity of which Nick Platts had precious little at this stage in his graduate work.

In such circumstances, it’s best to think boldly. Nick envisioned a single sequence of experiments that might validate every facet of his theory. His plan: First obtain a sample of a modest-sized PAH, one with a dozen or so interlocking rings. He settled on the elegant, symmetrical hexabenzocoronene (HBC), with its starlike pattern of 13 rings. Put the HBC into a flask with some water, functionalize the molecules by irradiation with an ultraviolet lamp, then measure the system for discotic organization. That much we were pretty confident would work, based on a survey of the discotics literature. Then add base mol-

ecules, such as adenine and guanine (the A and G of the RNA alphabet to the system and see if the PAHs bond to them. Finally—and we all knew that this would be a long shot—add a molecule that might serve as a backbone, such as formaldehyde, and see if the bases would link together into a long sequence reminiscent of a genetic polymer.

The experimental protocols looked good on paper, but there were problems from the start. Pure PAHs (as opposed to random sooty mixtures) turn out to be almost impossible to find commercially, and when you do, they’re impossibly expensive. Nick located one European supplier who would sell us tiny amounts of HBC for a thousand dollars—the equivalent of more than a million dollars for ten grams! That clearly wasn’t going to work.

Nick contacted other labs in Europe and Japan, hoping for a complimentary supply, but tracking one down might take weeks or months. Meanwhile, he manufactured some PAHs of his own by burning acetylene in air and catching the sooty residues in one of my more expensive glass beakers. Gradually, the soot, which is a mixture of hundreds of different PAHs ranging in size from a few rings to hundreds, piled up.

I offered to try another angle: purifying PAHs from soot by TLC—the thin-layer chromatography technique I had learned in Dave Deamer’s lab (see Chapter 11). Nick agreed, and we ordered a supply of trichlorobenzene, one of the solvents of choice when working with PAHs.

Nick had other concerns besides experiments. He was still determined to publish his idea, so he prepared a new version of the short paper and submitted it to Science on Thursday, July 15th.

Lots of people at Carnegie had been aware of the PAH World buzz and wanted to hear from Nick first hand. He presented an informal talk to the Carnegie campus on Friday afternoon July 2nd and again for a NASA Astrobiology Institute video seminar on Monday, July 12th. Each talk provided an opportunity to hone his arguments and to field a new round of questions and comments from origins experts across the spectrum.

His thesis defense also loomed large. Scrambling to write up an expanded description of his hypothesis and assemble whatever support he could from the published literature, Nick cobbled together a doctoral dissertation and headed back up to Troy for a July 20th defense. We all wondered whether he could pull it off. As it turned out,

his thesis committee, chaired by chemistry professor Gerry Korenowski, was more than a little impressed by Nick’s elegant vision. In five years of graduate work he had demonstrated his depth of chemical understanding and intuition. The PAH World hypothesis established beyond doubt that he had earned the right to be called “Doctor Platts.” They granted Nick an extra week to polish up his prose, and on July 27th he successfully defended what has to be one of the most unusual chemistry theses in RPI’s history.

MOVING ON

Having his doctorate in hand was a tremendous relief, but Nick’s problems weren’t over. His visa was about to run out unless he could find a science job in the United States. Could I help?

Nick’s inspiration centered on the behavior of self-organizing amphiphilic molecules. The logical person to call was Dave Deamer, who received some support from our NASA Astrobiology Institute grant to study molecular self-organization. Dave had also published some intriguing speculations about the energetic role of functionalized PAHs, which might have gathered light to power a sort of primitive photosynthesis. I sent Dave a long e-mail describing Nick’s unusual circumstances and his special gifts. Dave, always kind and gracious, responded almost immediately. Yes, he thought he would have a research slot opening up in the fall. When could Nick start?

![]()

Nick is in Santa Cruz now, attempting the experiments that may support or refute his ingenious model. It’s too soon to tell if the PAH World hypothesis will pan out, but whatever the outcome of Nick Platts’ work, we’ll know more than we did before. PAHs, or PNA, or some other information-rich, self-replicating genetic system must have emerged on the path to the RNA World. That first genetic molecule must have been much more resilient than RNA, though it was undoubtedly significantly less efficient as a replicator. At some point, as self-replicating genetic molecules became more competitive, RNA took over. The era of Darwinian evolution had begun.